1. Introduction

With the fast development of industries, the increasing organic pollutants bring great harm to animals, plants and human society in recent years. The ZnO nanoparticles have attracted much attention in the photodegradation of organic pollutants due to their excellent photovoltaic properties, good thermal stability and low cost, etc[

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. However, the photocatalytic activity of ZnO is limited due to the easy complexation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs and the narrow spectral absorption range[

6]. Therefore, inhibition of photogenerated electron-hole pair complexation and enhancement of visible light utilisation are the main ways to improve the photocatalytic performance[

7].

Two-dimensional carbon nanomaterials such as graphene oxide (GO) or reduced graphene oxide (rGO) exhibits excellent electrical conductivity, the large surface area, strong light absorption and efficient electron transfer capabilities, which has been draw a dedicated following in the photocatalysis field[

8,

9]. Significantly, the GO surface contains enriched with a variety of oxygen-containing functional groups, which is conducive to the transfer of electron-holes[

10,

11]. For example, Liu et al. constructed r-GO/TP-COF heterostructure photocatalyst to improve the photocatalytic properties[

12]. Therefore, GO can be employed as a charge movement accelerator to additionally raise photocatalytic properties. To date, ZnO/r-GO heterostructure photocatalyst can be constructed by the following three types: (1)the reduction of graphene on the basis of the ZnO structure[

13], (2) the preparation of ZnO on r-GO[

14], and (3) the preparation of ZnO along with graphene reduction [

15]. The previous two types require optimisation of the ZnO or GO. Therefore, the preparation of ZnO along with graphene reduction is considered as an effective way to fabricate ZnO/r-GO nanocomposites[

16,

17,

18]. However, the agglomeration of ZnO on the r-GO limit the electron mobility of the catalyst during photocatalysis[

19]. Therefore, how to evenly distribute ZnO nanoparticles on GO has become the focus of current research[

20,

21].

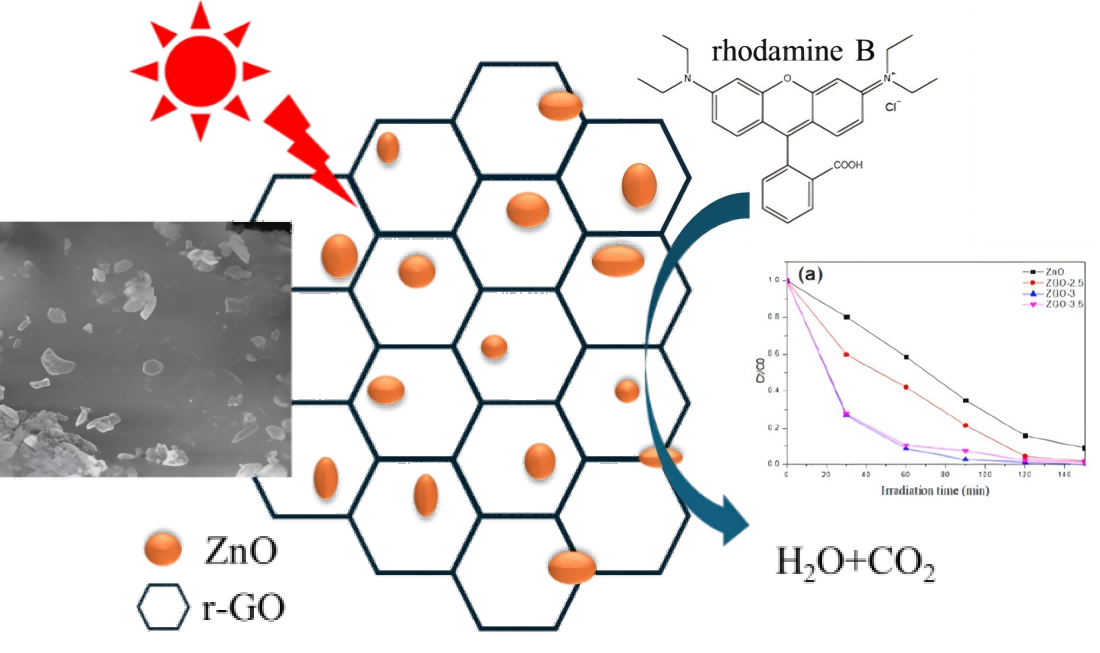

Herein, in this work, different ratios of ZnO nanoparticles were homogeneously dispersed on the surface of r-GO by hydrothermally to design the ZnO/rGO heterostructure. The reasons for the improved photocatalytic performance of ZnO were investigated by ultraviolet-visible diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-vis), the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller(BET), photocurrent and so on. The ZnO/rGO photocatalyst displays a remarkable raised RhB degradation rate compared to the pure ZnO nanoparticles, and possess good stability in repeated catalytic experiments.

2. Experimental

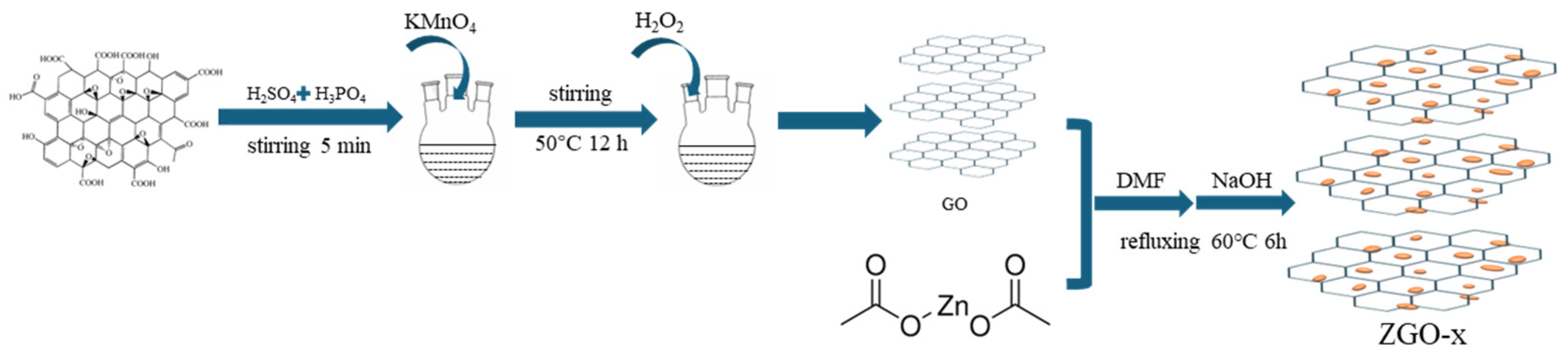

2.1. Synthesis of r-GO

The r-GO was prepared by the redox method. 1.5 g of graphite powder is mixed with 180 ml of concentrated sulfuric acid and 20 ml of concentrated phosphoric acid and stirred for 5 minutes. Subsequently, 9 g of potassium permanganate was slowly added, and the water bath was heated up to 35°C with continued stirring for 60 min. The mixed solution was then heated to 50°C and stirred for 12 hours. After the solution was cooled to room temperature, A certain amount of H2O2 was added until the colour of the mixture changes from purple-black to brown-yellow. Finally, the brownish-yellow solution was filtered, washed, and dried.

2.2. Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles/r-GO

62.5 ml of 0.02 mol/L zinc acetate/methanol solution was mixed with r-GO, subsequently, 1 ml of N,N dimethylamide (DMF) was added and condensed under reflux at 60℃. The reaction was carried out for 6 hours with the addition of 25 ml of 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution dropwise. The resulting samples were collected by centrifugation and subsequently washed three times using water and ethanol each. The resulted final catalysts with increasing the Zn content were labeled as ZGO-x (x=2.5, 3 and 3.5), and their theoretical mass ratio of Zn/r-Go is 2.5:1、3:1、3.5:1(

Figure 1).

2.3. Catalyst Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on a Rigaku SmartLab 9kW diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation (λ=0.15418nm) in the 10-85°range. N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms was performed on a micromeritics ASAP-2460 instrument in static mode and all samples were degassed at 350 °C for 3 h. The specific surface area was calculated by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) equation, and the pore volume and average pore diameter were calculated based on the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed on Thermo Fisher Scientific EscaLab 250Xi instrument. The peak positions were corrected by using the containment carbon (C 1s peak=284.8 eV).

2.4. Catalytic Activity Measurement

25 mg of ZGO-x catalyst was added to 50 mL of aqueous MO solution and adsorbed for 30 min at room temperature, and then exposed to xenon lamp at a light intensity of approximately 413 mW/cm2. 3 ml of supernatant was removed at regular intervals, filtered through a 0.45 mm Millipore filter and analysed by UV-vis spectrophotometer. The working electrode was prepared by dispersing 10 mg of the ZGO-x in CH3CH2OH and ultrasounding for 10 min. The slurry was subsequently impregnated onto the surface of a 1 cm×3 cm fluorotin oxide (FTO) glass substrate, which was allowed to dry overnight at room temperature. The separation efficiency of photogenerated electron-hole pairs was recorded on the CHI660D electrochemical workstation by using a standard three-electrode system. The saturated sodium sulfate solution was used as electrolyte, graphite and Ag/AgCl electrodes were used as the counter and reference electrodes, and the sample-derived electrode was used as the working electrode. A 300 W Xe lamp (PLS-SXE300, Perfectlight Corporation) with 100 mW/cm2 UV-Vis intensity was used as the light source.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Structure and Physical Properties

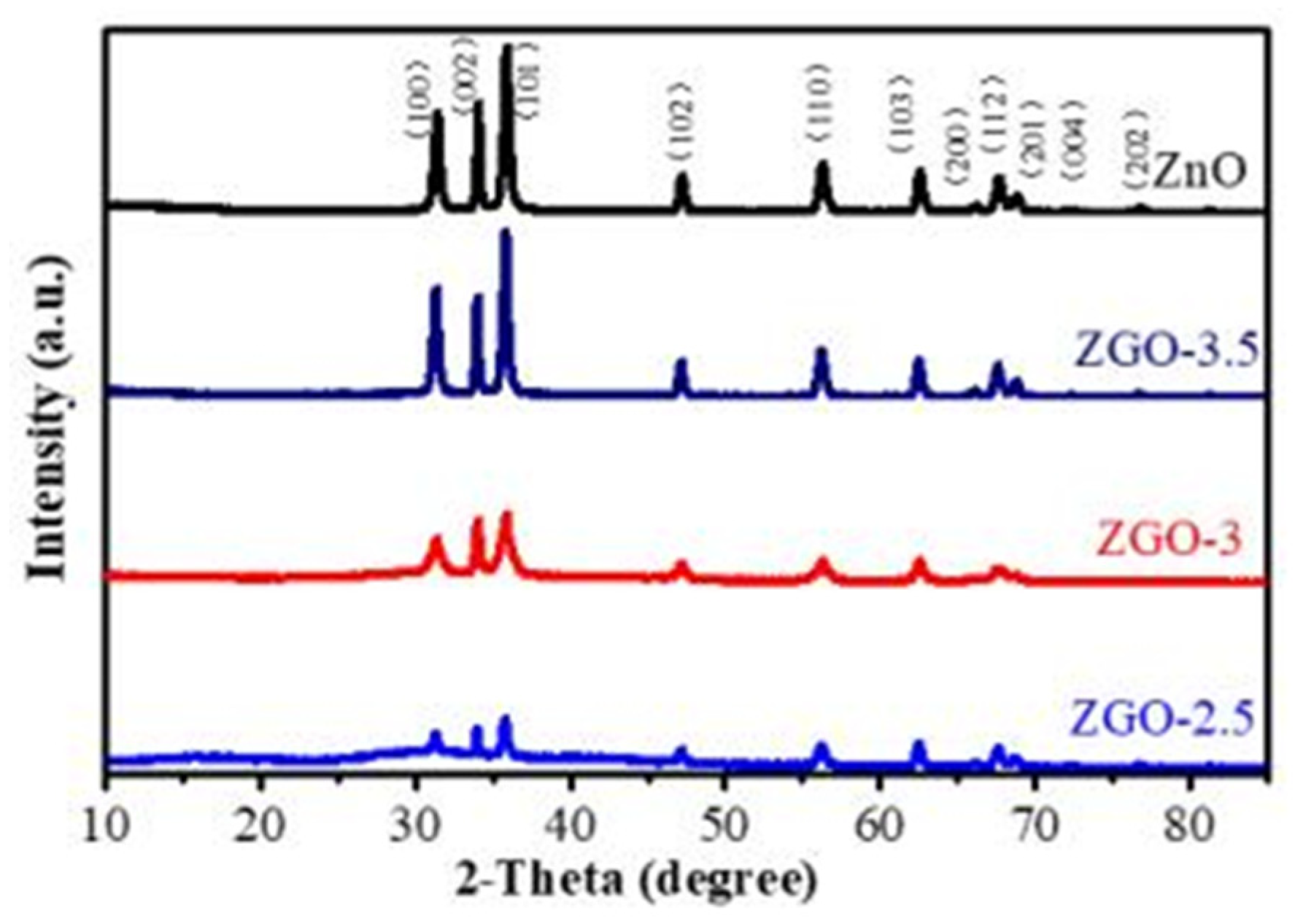

Figure 2 shows the XRD spectra of ZnO, ZGO-2.5, ZGO-3 and ZGO-3.5 to determine the crystalline state of the Zn species in the materials. All the diffraction peaks match the standard data for the fibrillated zincite structure of ZnO (JPCDS 36-1451), which suggests that the presence of r-GO does not lead to the emergence of a new crystalline form of ZnO[

22]. Moreover, the typical diffraction peaks of r-GO at 26°(002) and 44.5°(100) were not observed in ZGO-x series catalysts, which may be due to the low content of r-GO[

23]. In addition, it was noticed that the intensity of the ZnO peaks increased with increasing ZnO content, but the positions of the diffraction peaks were not shifted and no other characteristic diffraction peaks appeared, indicating that the ZGO-x series catalysts could be successfully prepared by this method.

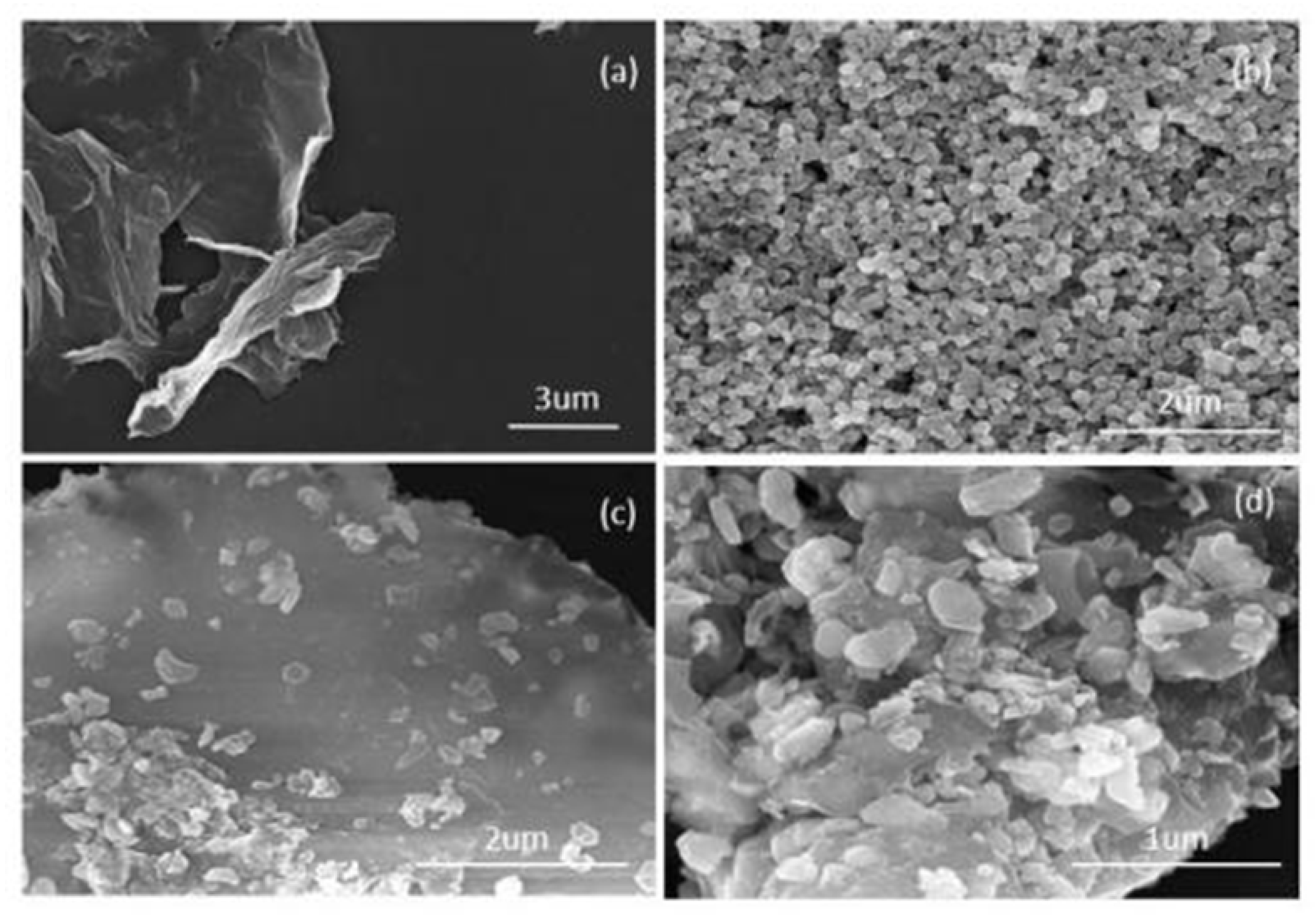

SEM was employed to ascertain the microscopic morphology and the variation pattern of ZGO-x series samples, which are presented in

Figure 3. The results shows that r-GO is a two-dimensional nanosheet structure with slightly wrinkled at the end, which can be judged as a relatively thin sheet structure[

24].

Figure 3b shows the SEM of ZnO, which displays that the prepared ZnO nanoparticles are relatively regular and homogeneous. Firstly, the nanoparticle structure of ZnO and the two-dimensional ultrathin nanosheet structure of r-GO can be clearly observed from the SEM images, and the respective morphologies are kept relatively intact, indicating that the ZnO and GO are not destroyed. Secondly, as the Zn content increases, the ZnO particles formed on the surface of r-GO become larger(

Figure 3c-d). However, agglomeration phenomenon is formed when excessive ZnO are attached onto r-GO[

25]. This phenomenon will lead to a reduction in the light-exposed area of the catalyst, which is unfavourable to the generation of photogenerated electrons, and more importantly, it will affect the photocatalytic performance of the catalyst.

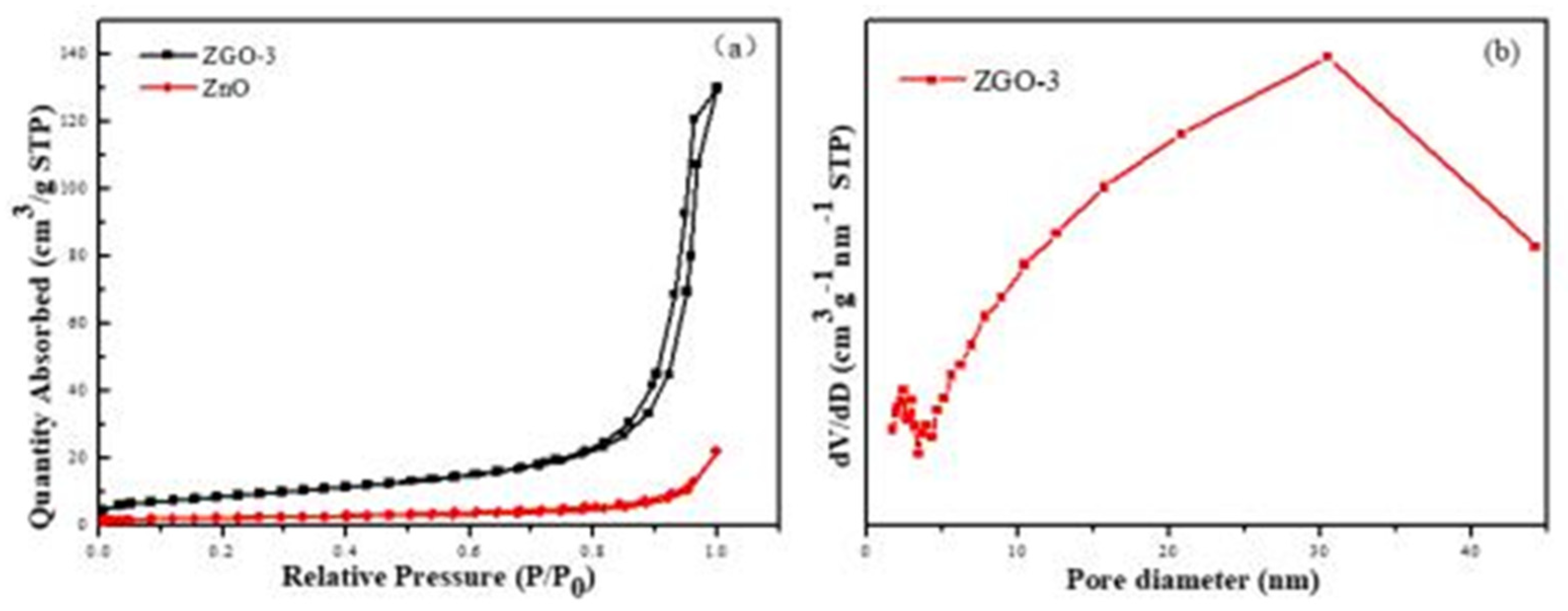

Another main factor influencing the photocatalytic performance of photocatalyst is the specific surface area and pore size distribution of the catalyst[

26]. The results of the adsorption-desorption isothermal curves and porous distributions of ZnO and ZGO-3 are shown in

Figure 4. All samples are type IV curve, which are in accurate accordance with the results of mesoporous materials. It is also found that the positions of the H3-type rings are at the higher relative pressure (0.8-1.0), indicating the existence of large pores in the materials. It also indicates that the pores in the materials are mainly formed by flakes or particles, which coincides with the r-GO flake structure. The specific surface areas and pore volumes of ZnO and ZGO-3 are presented in

Table 1. The specific surface area of ZGO-3 is 31.5425 m

2/g, which is more than that of ZnO (8.1486 m

2/g), resulting in the adsorption capacity of ZGO-3 being stronger than that of ZnO and GO. Therefore, ZGO-3 possesses more reactive sites on its surface in the catalytic reaction[

27]. Meanwhile, the pore diameter of ZGO-3 is mainly distributed at about 33 nm (

Figure 4b).

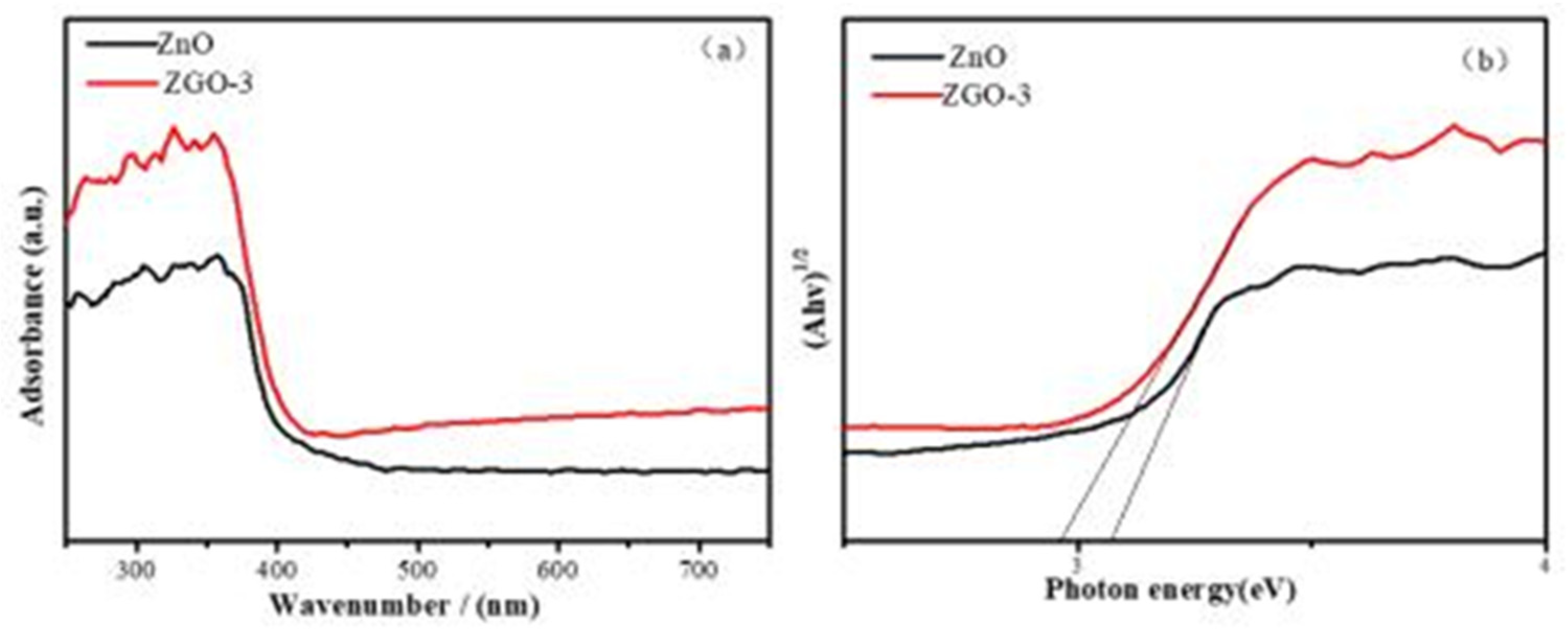

Ensuingly, to further determine the magnitude of the band gap energy and the light absorption performance of the prepared materials, DRUV-vis spectra (

Figure 5) were utilized to check ZnO and ZGO-3 samples at the ultraviolet band. The figure shows that the absorption edges of ZnO and ZGO-3 are 412.32 nm and 428.52 nm, respectively, and the band gap values of ZnO and ZGO-3 are calculated to be 3.172 eV and 2.953 eV by the Kubelka-Munk equation, respectively[

28]. The results show that the loading of ZnO on r-GO leads to a significant red-shift phenomenon of the catalyst. This is due to the fact that the loading of ZnO onto the r-GO surface increases the specific surface area of the ZGO-3, leading to the creation of more effective absorption sites on the surface. Taken together, this evidence can support the improved photocatalytic performance[

29].

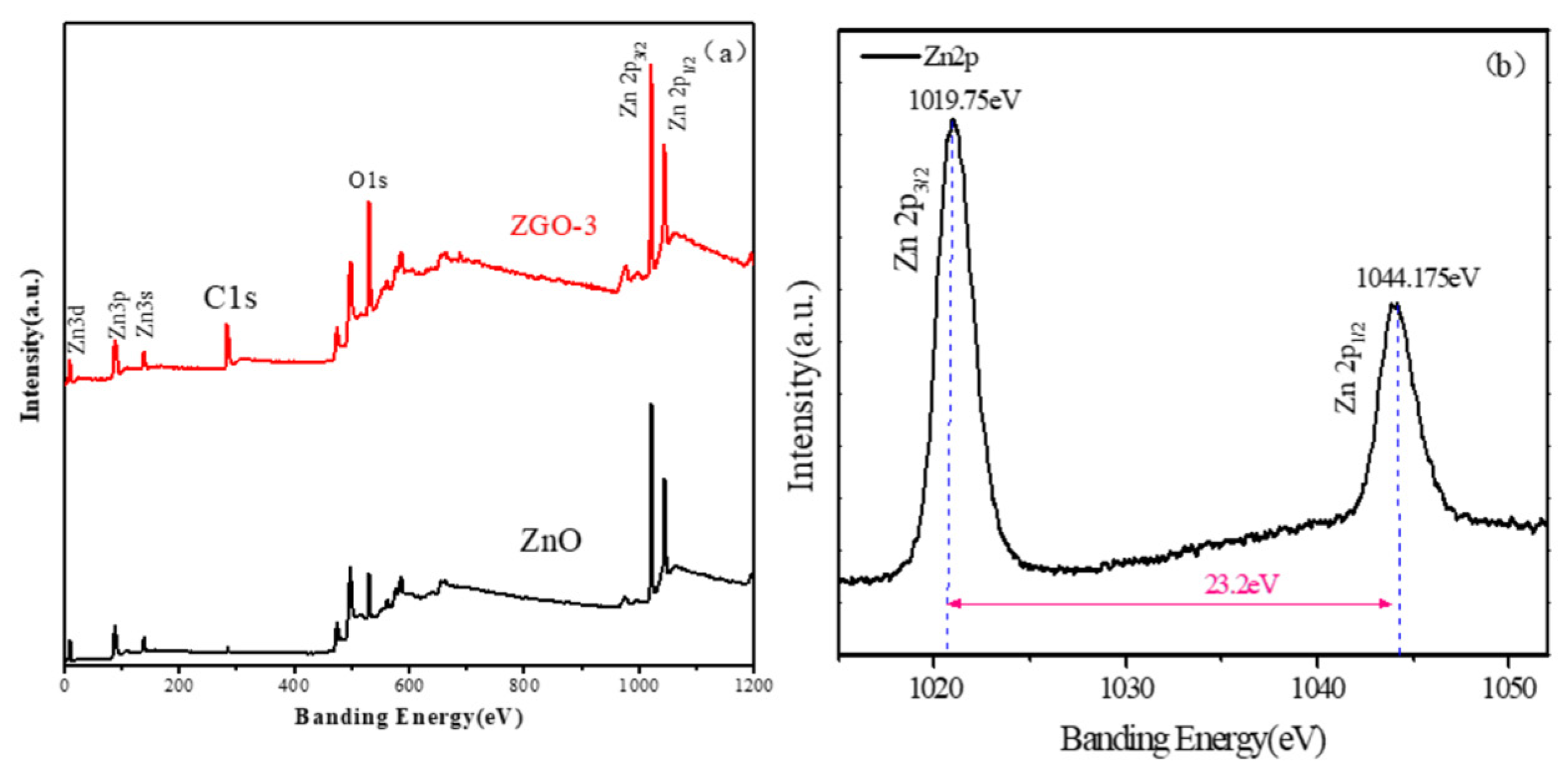

To ulteriorly identify the valence state of the major elements in the sample, we checked the ZnO and ZGO-3 by the XPS technique. The results of full survey (

Figure 6a) and the fine spectrum of Zn (

Figure 6b) are displayed respectively. The surface of ZnO/r-GO composites is mainly composed of C, Zn, O, elements. Moreover, the content of C in the ZGO-3 is obviously more than that of the ZnO nanoparticles alone. This may be caused by the fact that a portion of r-GO in the ZGO-3 sample was reduced to produce r-GO. For the Zn2p spectrum of ZGO-3, the binding energy of Zn2p1/2 and Zn2p

3/2 are located at1044.175 eV and 1019.75eV, respectively. While the spin-orbit splitting value of these peaks is 23.2 eV, which clearly indicates the presence of Zn

2+ in the ZnO[

30,

31,

32].

3.2. Catalytic Analysis

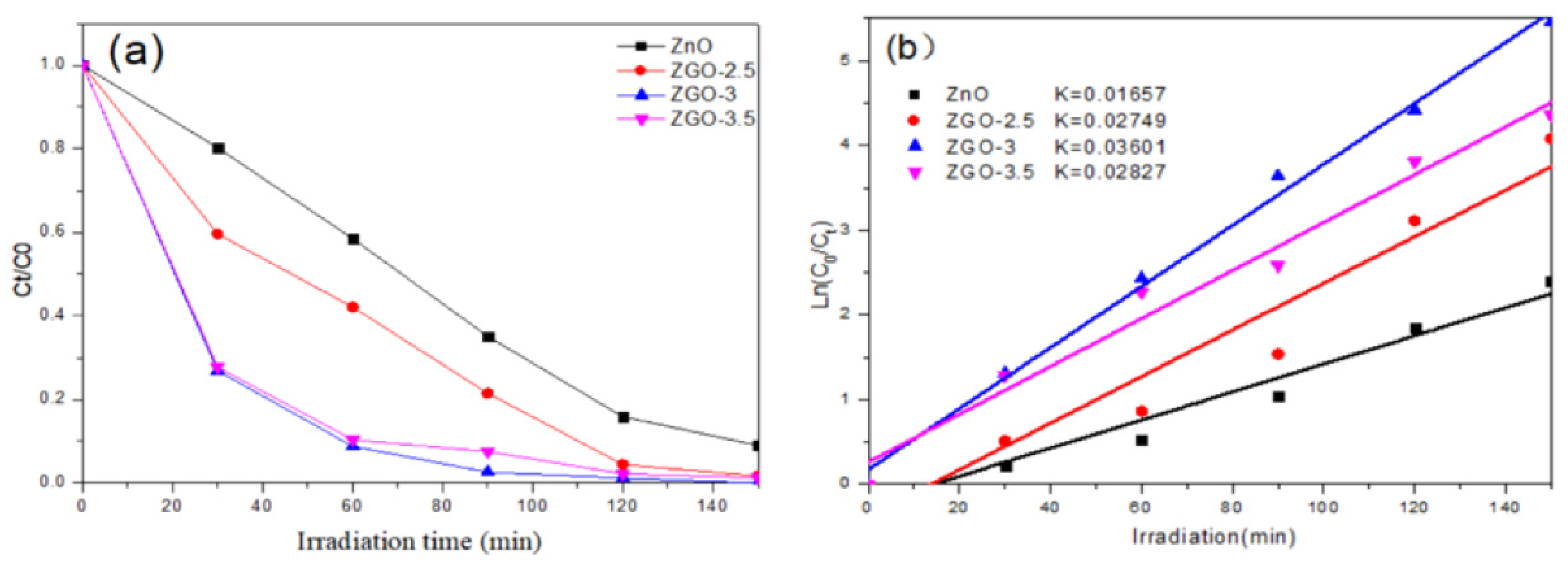

We simulated the photodegradation of rhodamine B(RhB) to determine the photocatalytic performance of the ZGO-x(

Figure 7). Prior to photodegradation, we evaluated the photocatalytic performance of the r-GO sample in RhB, which showed weak photocatalytic activity under sunlight. The reaction process of RhB degradation involving ZGO-x at the different time course can be discerned (

Figure 7a). The results show that the photocatalytic mainly comes from Zn species. Secondly, under the same conditions, the photocatalytic performance of ZGO-x series catalysts varied with the irradiation time, which should be related to the different physicochemical properties of the ZGO-x. It is noteworthy that the photocatalytic activity shows the interesting trend with increasing ZnO loading in r - GO. The catalytic performance increased from ZGO-2.5 to ZGO-3, while the catalytic activity showed a decreasing trend when the ZnO loading was further raised to 3.5%. Among all the samples, sample ZGO-3 showed the best photocatalytic performance, which the RhB was almost 100% degraded after 150 min of the degradation reaction. However, the ZnO degraded about 83% of RhB under the same conditions.

Next, assuming that all the degradation reactions conform to the proposed first-order kinetic model, the reaction kinetic rate constants were calculated by making a linear fit plot of ln(C

0/C

t) against time[

33]. From

Figure 7b, it is obvious that the relationship between the magnitude of the reaction rate constants for each sample is: ZGO-3 (k=0.03601) > ZGO-3.5 (k=0.02827) > ZGO-2.5 (k=0.02749) > ZnO (k=0.01657). Therefore, we can know that the reaction rate of sample ZGO-3 is the fastest and the photocatalytic effect is the best. Methyl orange was also chosen as the target simulated pollutant, and the photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange was conducted by the above four samples. The sample ZGO-3 showed the best photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange under simulated sunlight, with 100% degradation within 180 min, while the pure ZnO only degraded 87.64% of methyl orange under sunlight(

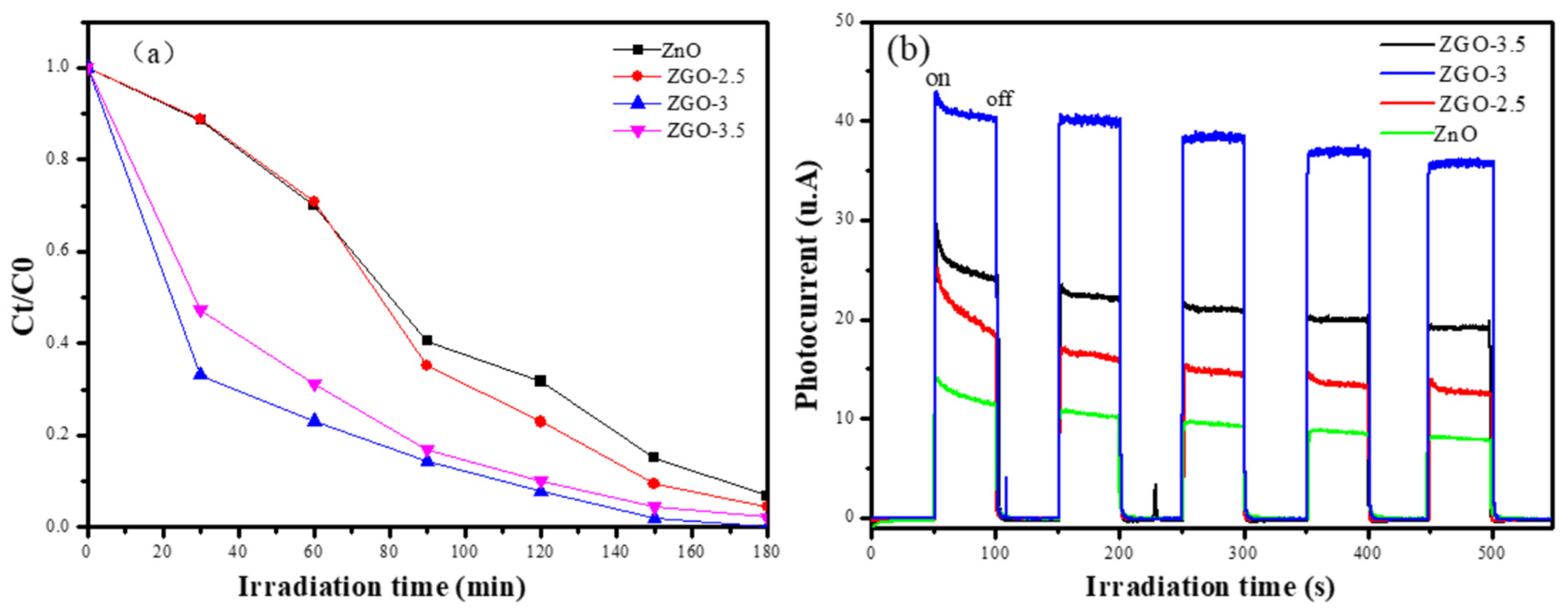

Figure 8a). Combined with the previously described characterisation, we suggested that ZnO may form agglomeration to some extent on the catalyst surface as excessive ZnO particles appear on the catalyst surface. In addition, the excessive introduction of the Zn element in r-GO will obviously damage the porous structure and lead to the degradation of physical structural properties. Even, the resulting light-exposed area of the catalyst will be reduced, which is unfavourable for the generation of photogenerated electrons.

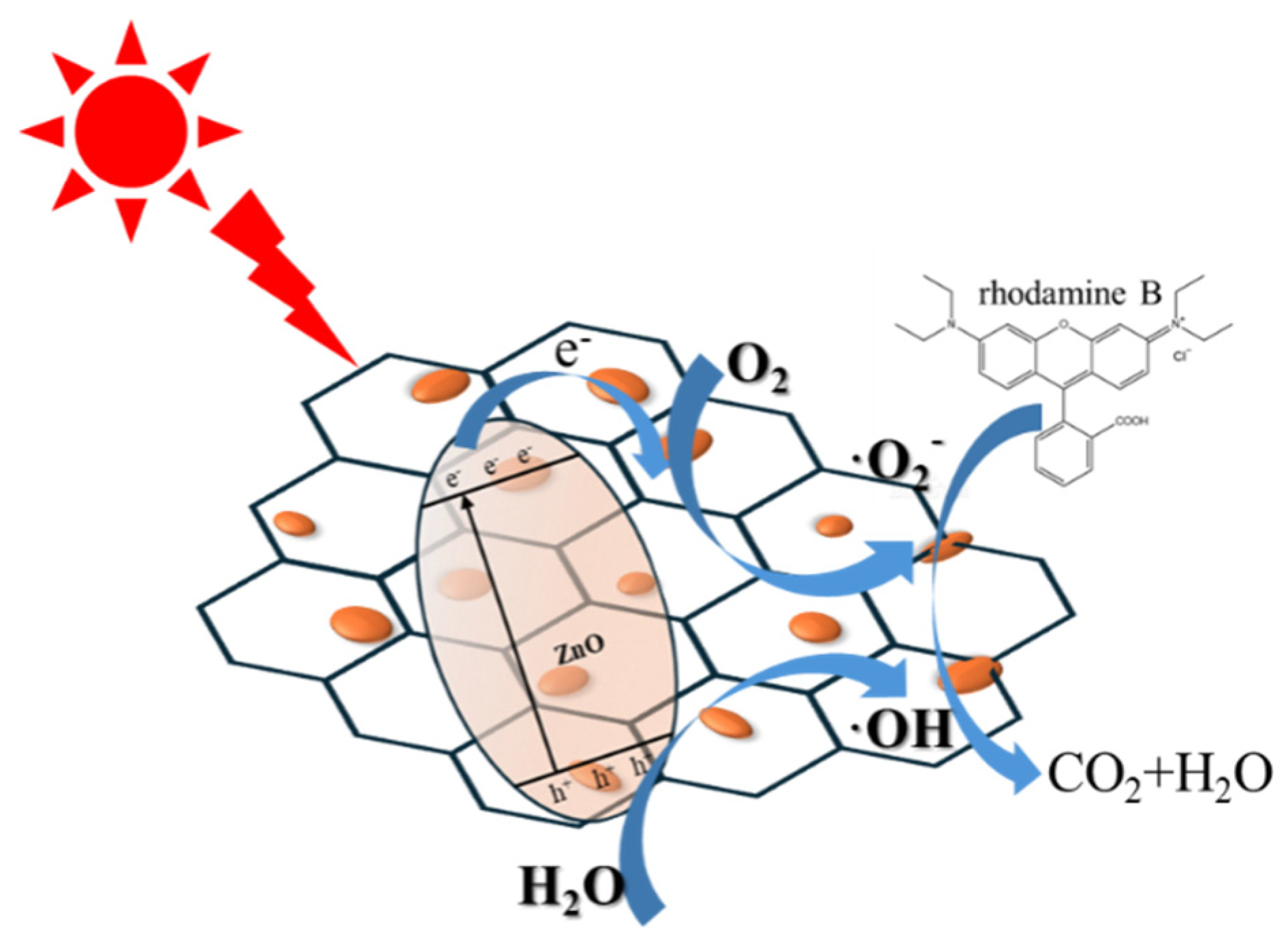

And, the ability to separate electrons (e

-) and holes (h

+) generated by photoexcitation is also a major factor affecting the photocatalytic reaction, and the photocurrent test was used to investigate the separation efficient of photogenerated electrons and holes of the prepared samples. In the absence of light exposure, no photocurrent was generated, whereas in the presence of light, a transient current was generated. The phenomenon suggests that when a light source irradiates a photocatalyst, directionally moving electrons are generated to form a photocurrent. As shown in the

Figure 8b, the photocurrent signal of sample ZGO-3 is the strongest with a maximum of 43.5 μA/cm

2 after five light-on/light-off cycles, which is 2.94 times higher than that of ZnO (14.8 μA/cm

2). The results clearly indicate that the effective complexation of ZnO with r-GO results in the transfer of photoexcited electrons from ZnO to r-GO, which serves to separate photogenerated electron-hole pairs and improve the photocatalytic performance.

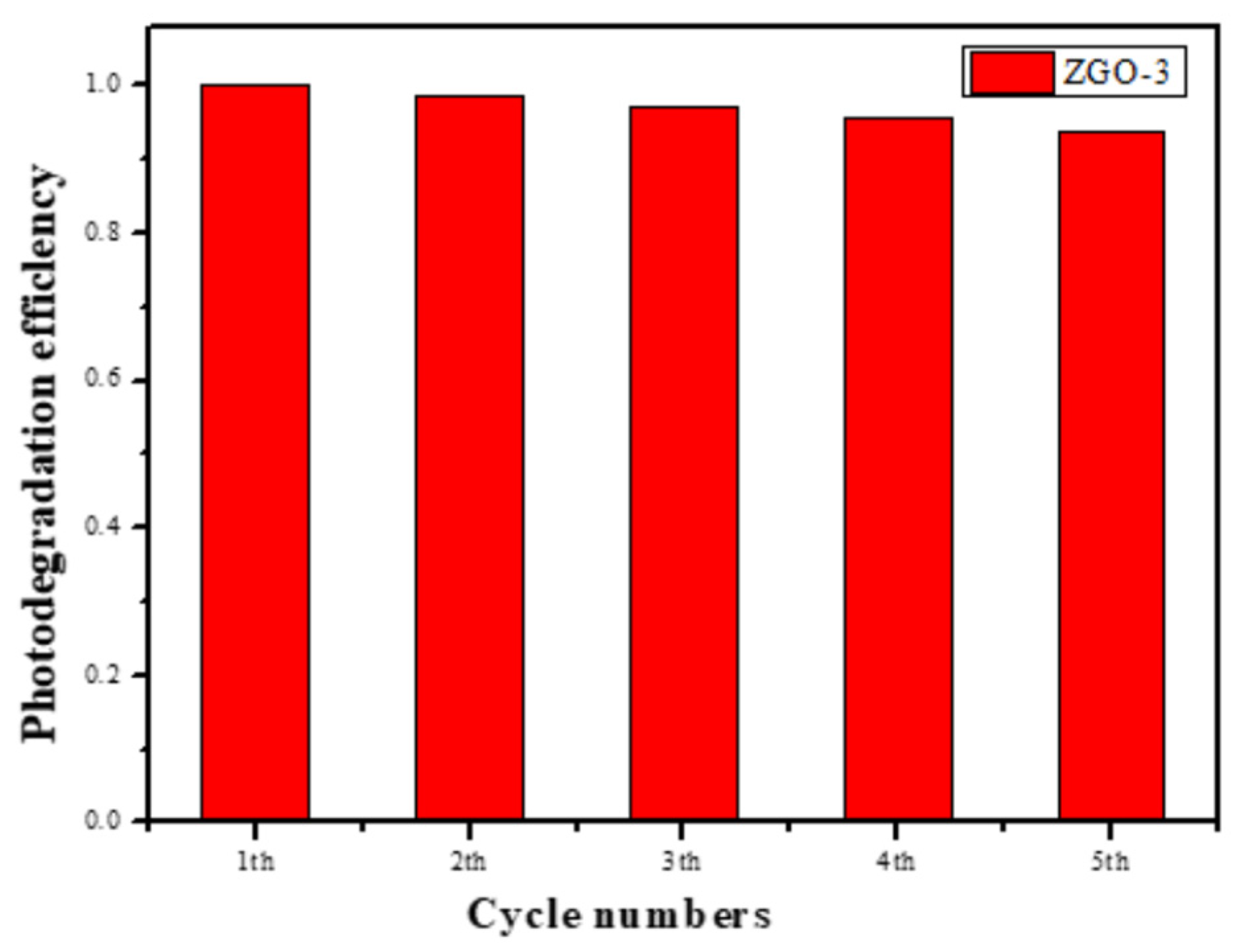

We then assessed the photocatalytic stability of the selected best catalyst by recovering the ZGO-3 catalyst and the photocatalytic results are shown in

Figure 9. Fortunately, the photocatalytic activity is capable of being retained for 5 times at least. However, careful observation showed that the photocatalytic activity decreased slightly. Subsequently, the zinc content in the catalyst was measured by ICP. The results showed that the zinc content decreased from 3 wt % to 2.8 wt %, which should be the reason for the decrease of c photocatalytic performance after 5 cycles.

Figure 9.

The recycling test results of ZGO-3.

Figure 9.

The recycling test results of ZGO-3.

Figure 10.

Schematic illustration of possible photodegradation of RhB process over ZGO-x.

Figure 10.

Schematic illustration of possible photodegradation of RhB process over ZGO-x.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we generated ZnO/r-GO composite catalysts by growing ZnO onto r-GO surface via a hydrothermal method. A series of characterisations showed that the composites retained the morphology and crystallinity of the original ZnO and exhibited strong stability and reliability. The ZGO-3 sample presented the highest degradation efficiency for RhB, which the RhB was almost 100% degraded after 150 min. The reason for the improved catalytic ability of ZnO/r-GO photocatalysts is due to the formation of a tight association between ZnO and r-GO sheets. In addition, the ZnO/rGO composites promote the reduction of the recombination of photo generated e-h pairs. This study supplies new thoughts for the build of ZnO/r-GO composites for environmental applications.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22272070,22362027 , 22302089), the Key Laboratory of Photochemical Conversion and Optoelectronic Materials, TIPC, CSA (No. PCOM201906), Jiangxi Province "double thousand plan" project (jxsq2019201007, jxsq2020102027), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province(20242BAB20183).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- J L Liu, Y H Wang, J Z Ma, et al. A review on bidirectional analogies between the photocatalysis and antibacterial properties of ZnO[J]. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2019, 783, 898-918. [CrossRef]

- H Fatima, M Azhar, M Khiadani et al. Prussian blue-conjugated ZnO nanoparticles for near-infrared light-responsive photocatalysis-ScienceDirect[J]. Materials Today Energy, 2021, 23, 100895.

- D Smazna, S Shree, O Polonskyi, et al. Mutual Interplay of ZnO Micro- and Nanowires and Methylene Blue during Cyclic Photocatalysis Process[J]. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2019, 7(2), 103016. [CrossRef]

- R Nawaz, H Ullah, A A J Ghanim, et al. Green Synthesis of ZnO and Black TiO2 Materials and Their Application in Photodegradation of Organic Pollutants[J]. ACS Omega, 8(39), 36076-36087. [CrossRef]

- S Harish, J Archana, M Sabarinatha, et al. Controlled structural and compositional characteristic of visible light active ZnO/CuO photocatalyst for the degradation of organic pollutant[J]. Applied Surface Science, 2016, 418, 103-112. [CrossRef]

- X Ji, L Chen, M X Xu, et al. Crystal Imperfection Modulation Engineering for Functionalization of Wide Band Gap Semiconductor Radiation Detector [J]. Advanced Electronic Materials, 2018, 4(2), 1700307. [CrossRef]

- V C Padmanaban, M S G Nandagopal, G M Priyadharshini, et al. Advanced approach for degradation of recalcitrant by nanophotocatalysis using nanocomposites and their future perspectives[J]. International Journal of Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 13(6):1591-1606. [CrossRef]

- J Guo, M Si, X Zhao, et al. Altering interfacial properties through the integration of C-60 into ZnO ceramic via cold sintering process[J]. Carbon, 2022, 190,255-261. [CrossRef]

- S Aydogan, N Canpolat, A Kocyigit, et al. Synergistic enhancement of simazine degradation using ZnO nanosheets and ZnO/GO nanocomposites: A sol-gel synthesis approach [J]. Ceramics International, 2024, 50(14), 25080-25094. [CrossRef]

- M Zhu, P Chen, M Liu. Highly efficient visible-light-driven plasmonic photocatalysts based on graphene oxide-hybridized one-dimensional Ag/AgCl heteroarchitectures[J]. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 2012, 22: 21487. [CrossRef]

- H He, Y Cheng, S Qiu, et al. Construction and mechanistic insights of a novel ZnO functionalized rGO composite for efficient adsorption and reduction of Cr(VI)[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2024, 31(23):34607-34621. [CrossRef]

- Y Liu, Y Wang, J Shang, et al. Construction of a novel metal-free heterostructure photocatalyst PRGO/TP-COF for enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction[J]. Applied Catalysis B: Environment and Energy, 2024, 350: 123937. [CrossRef]

- C Rodwihok, D Wongratanaphisan, Y L T Ngo, et al. Effect of GO Additive in ZnO/rGO Nanocomposites with Enhanced Photosensitivity and Photocatalytic Activity[J]. Nanomaterials, 2019, 9: 1441. [CrossRef]

- C Paraschiv, G Hristea, M Iordoc, et al. Hydrothermal growth of ZnO/GO hybrid as an efficient electrode material for supercapacitor applications[J]. Scripta Materialia, 2021, 195:113708. [CrossRef]

- P Bharadwaj, G R Kiran, S G Acharyya. Remarkable performance of GO/ZnO nanocomposites under optimized parameters for remediation of Cd (II) from water[J]. Applied Surface Science, 2023, 626, 157238. [CrossRef]

- T Prabhuraj, S Prabhu, E Dhandapani, et al. Bifunctional ZnO sphere/r-GO composites for supercapacitor and photocatalytic activity of organic dye degradation[J]. Diamond and Related Materials, 2021,108592. [CrossRef]

- P Kumar, S Som, M K Pandey, et al. Investigations on optical properties of ZnO decorated graphene oxide (ZnO@GO) and reduced graphene oxide (ZnO@r-GO)[J]. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2018, 744, 64-74. [CrossRef]

- R K Jammula, V V Srikanth, B K Hazra, et al. ZnO nanoparticles' decorated reduced-graphene oxide: Easy synthesis, unique polarization behavior, and ionic conductivity[J]. Materials & Design, 2016, 110, 311-316. [CrossRef]

- H Khan. Graphene based semiconductor oxide photocatalysts for photocatalytic hydrogen (H2) production, a review[J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2014, 84, 356-371. [CrossRef]

- I D Kim, S J Choi, H J Cho. Graphene-Based Composite Materials for Chemical Sensor Application[J]. 2015.

- R Atchudan, S Perumal, M Shanmugam, et al. Direct solvothermal synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticle decorated graphene oxide nanocomposite for efficient photodegradation of azodyes[J]. Journal of Photochemistry & Photobiology A Chemistry, 2017, 337,100-111. [CrossRef]

- W X Ma, M L Lv, F P Cao, et al. Synthesis and characterization of ZnO-GO composites with their piezoelectric catalytic and antibacterial properties[J]. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2022, 10(3), 107840. [CrossRef]

- N Elumalai, S Prabhu, M Selvaraj, et al. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of ZnO hexagonal tube/rGO composite on degradation of organic aqueous pollutant and study of charge transport properties[J]. Chemosphere, 2021, 291,132782. [CrossRef]

- Y H Zou, G J Chang, S Chen, et al. Alginate/r-GO assisted synthesis of ultrathin LiFePO4 nanosheets with oriented (010) facet and ultralow antisite defect [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2018, 351,340-347. [CrossRef]

- S Dadashov, E Demirel, E Suvaci. Tailoring microstructure of polysulfone membranes via novel hexagonal ZnO particles to achieve improved filtration performance[J]. Journal of Membrane Science, 2022,651, 120462. [CrossRef]

- J Puneetha, K Nagaraju, A Rathna. Investigation of photocatalytic degradation of crystal violet and its correlation with bandgap in ZnO and ZnO/GO nanohybrid[J]. Inorganic Chemistry Communications, 2021, 125,108460. [CrossRef]

- X Wang, H Tian, X Cui, et al. One-pot hydrothermal synthesis of mesoporous Zn(x)Cd(1-x)S/reduced graphene oxide hybrid material and its enhanced photocatalytic activity.[J]. Dalton Trans, 2014, 43(34),12894-12903. [CrossRef]

- R Ivan, C Popescu, A. P Pino, et al. Carbon–based nanomaterials and ZnO ternary compound layers grown by laser technique for environmental and energy storage applications[J]. Applied Surface Science, 2020, 509, 145359. [CrossRef]

- H Y He, J Fei, J Lu. High photocatalytic and photo-Fenton-like activities of ZnO–reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites in the degradation of malachite green in water[J]. Iet Micro & Nano Letters, 2015, 10(8),389-394. [CrossRef]

- N Mukwevho, R Gusain, E F Kankeu, et al. Removal of naphthalene from simulated wastewater through adsorption-photodegradation by ZnO/Ag/GO nanocomposite[J]. Journal of industrial and engineering chemistry, 2020, 81, 393-404. [CrossRef]

- G J Rani, M A J Rajan, G G Kumar. Reduced graphene oxide/ZnFe2O4 nanocomposite as an efficient catalyst for the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye[J]. Research on Chemical Intermediates, 2016, 43(4), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- G M Reza, C T Dinh, F Béland, et al. Nanocomposite heterojunctions as sunlight-driven photocatalysts for hydrogen production from water splitting[J]. Nanoscale, 2015, 7(18), 8187- 8208. [CrossRef]

- F Yang, S Gao, Y Ding, et al. Excellent porous environmental nanocatalyst: tactically integrating size-confined highly active MnOx in nanospaces of mesopores enables the promotive catalytic degradation efficiency of organic contaminants[J].New Journal of Chemistry, 2019, 43(48), 19020-19034. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).