1. Introduction

The current global population and technological advancements have created a pressing need for a sustainable society, where green economy plays a key role [

1]. In response to the growing demand for reducing environmental impact, it has become imperative to integrate, innovate, and embrace renewable sources of energy and materials to achieve climate neutrality. Achieving climate neutrality means creating a balance between greenhouse gas emissions and their removal, primarily by reducing emissions, advancing sustainable technologies, and preserving natural ecosystems [

2]. Since the foundation of economic growth is built upon infrastructure, the cement industry plays here a crucial role [

1]. However, producing cement clinker is energetically intensive and poses as a significant contributor to CO2 emissions worldwide, but it is known that the industry is proactively pursuing ways to transition towards low-carbon practices to promote sustainable and environmentally conscious practices [

3,

4]. Additionally, the use of refused derived fuels (RDF) to substitute fossil fuels is also very appealing in cement industry, as these present the potential to lower the clinker production costs and CO2 emissions [

5,

6,

7]. The use of RDF fuels in cement industry is actually a common practice since 1980’s. It was introduced to fight the large costs inherent to the first oil crisis and is considered ever since an efficient way of boosting industry decarbonization [

3].

The increase in waste generation coupled with the inadequate management strategies currently employed mean that the co-processing of waste as an alternative fuel in cement plants offers significant advantages by avoiding landfills [

3,

5,

8,

9].

However, RDF fuels are difficult to handle due to their variable physical and chemical properties, such as density, homogeneity, moisture content and composition and, for that reason, can greatly affect the combustion behavior within a cement rotary kiln [

3]. For instance, high-density particles tend to exhibit lower suspension capacities in a gas flow, implying a change in their trajectory and residence time in open flames [

10]. This behavior can significantly affect particles’ burnout and, if a particle is left unburnt, it may deposit onto the clinker being produced and reduce its quality [

11].

Conducting experiments in industrial facilities can be prohibitively expensive, underlining the extreme importance of modeling to simulate and optimize processes before implementing them in a real-world setting, especially using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) [

10,

11,

12]. Some authors have used CFD modeling to predict the combustion behavior using alternative fuels, in industrial cement rotary kilns in terms of flame temperature, flow velocity, flame stability, fuel and oxidant composition, emissions and calcination reactions [

7,

10,

11,

13,

14]. Liedman et al. [

7] started to study the influence of operating conditions in cement rotary kilns by co-firing different mixtures of RDF and pulverized coal. The authors characterized experimentally the different constituents of RDF (2D foils, 3D plastics, paper and cardboard, textiles and fines) and studied their specific flight paths in an automated drop-shaft to obtain drag and lift coefficients and their correspondent fluctuations. With this preliminary study, the authors concluded that each type of particle fraction had different motion trajectories especially when compared to the ones of pulverized coal. Hence, it was stated that this phenomenon should be taken into consideration when modeling combustion. Later, Liedman et al. [

10] continued their research and presented a simplified model approach that allow the prediction of the trajectory of each particle fraction and their combustion behavior separately. The authors concluded that the simplified model provided detailed information about each particle fraction trajectory and combustion. For the specific case of substituting 15% of the thermal heat using RDF a burnout of 83% was observed. Pieper et al. [

11] studied the combustion behavior in an industrial rotary cement kiln using a mixture of pulverized coal and RDF. The authors used advanced CFD models to characterize the thermal conversion process of non-spherical RDF particles and complemented this study by coupling a simplified 1-D model to evaluate the heat and mass transfer between the clinker bed and the gas phase within the kiln. The authors concluded that having a mixture of 50% RDF with 50% lignite showed a combustion delay, a temperature increase in the direction of the fuels’ inlet and a temperature drop of 45K in the gas phase in the sintering zone. They also added that larger particles can be projected to the clinker bed or to the kiln walls showing different burnout behaviors, limiting the conversion degree to 68%. In a later work, Pieper et al. [

13] extended their study to predict where were the regions inside the rotary kiln that exhibit coating layers from both RDF combustion and the clinker phase, i.e., adhesion of agglomerated particles that can decrease the process efficiency and clinker quality. The authors concluded that coating layers could decrease the residence time and the burnout of RDF particles during the gas phase being, thus, deposited unburnt in the clinker bed. The authors also stated that interaction mechanisms inside a rotary kiln are substantially more complex and that a validation of these results with the plant data is impractical, for obvious reasons. Nevertheless, predictions show good qualitative agreement when comparing these with observations made by cement plant operators. Ariyaratne et al. [

14] performed 3D CFD simulations to predict the effect of fuel particle size and feeding in the combustion behavior within an industrial cement rotary kiln. The authors modeled independently different cases with the use of pulverized coal and meat and bone meal (MBM), using different excess air coefficients, fuel feeding rate and particle size distribution. The authors concluded that for the same thermal input, when coal is compared with MBM, the gas temperature is lower. This is expected due to the high content of moisture and ashes present in the MBM composition and, as a consequence, a slower devolatilization in the flame region. It was also added that combustion is more efficient for smaller particles since a higher burnout is reached.

It is well established that an industrial burner of a cement rotary kiln has different entries to receive the primary and the alternative fuels, in different states of matter [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Additionally, to achieve a self-sustained combustion, different air mass flows must be supplied (commonly, primary and pre-heated secondary air) [

15,

16]. Given the above, it is realizable that modeling is usually performed simplifying the geometry of the burner or the mixture of fuels,. Additionally, in most cases, only a 2D CFD turbulent combustion model is provided to describe the functioning inside the rotary kiln, which provides nonetheless significant information. However, in these cases, symmetry conditions are assumed when in real setups these do not occur. In a way of contributing to filling this gap, in the present work it will be performed a 3D CFD turbulent combustion model considering a Pillard NOVAFLAM® burner type, with multiple entries for different fuels and multiple entries for the primary air and secondary air, including swirl. The model will be formulated in Ansys® version 2022 R2, using blends of different fuels (petcoke and RDF), having as base case scenarios from an industrial cement rotary kiln. The main objective of this work will be to provide valuable knowledge about the combustion behavior occurring within the rotary kiln studying real case scenarios and, to take one step forward and evaluate how far it is possible to go with substituting alternative fuels with fossil fuels, to contribute to the mitigation of CO2 emissions. Predictions will provide information of temperature and velocity fields, flame length, position and temperature, emissions, major species devolatilization and volatiles combustion.

2. Materials and Methods

The fuels used for the simulation – and their respective properties – are presented in

Table 1. These are divided into a fossil fuel, petcoke, and Refuse Derived Fuels (RDF) as the alternative one.

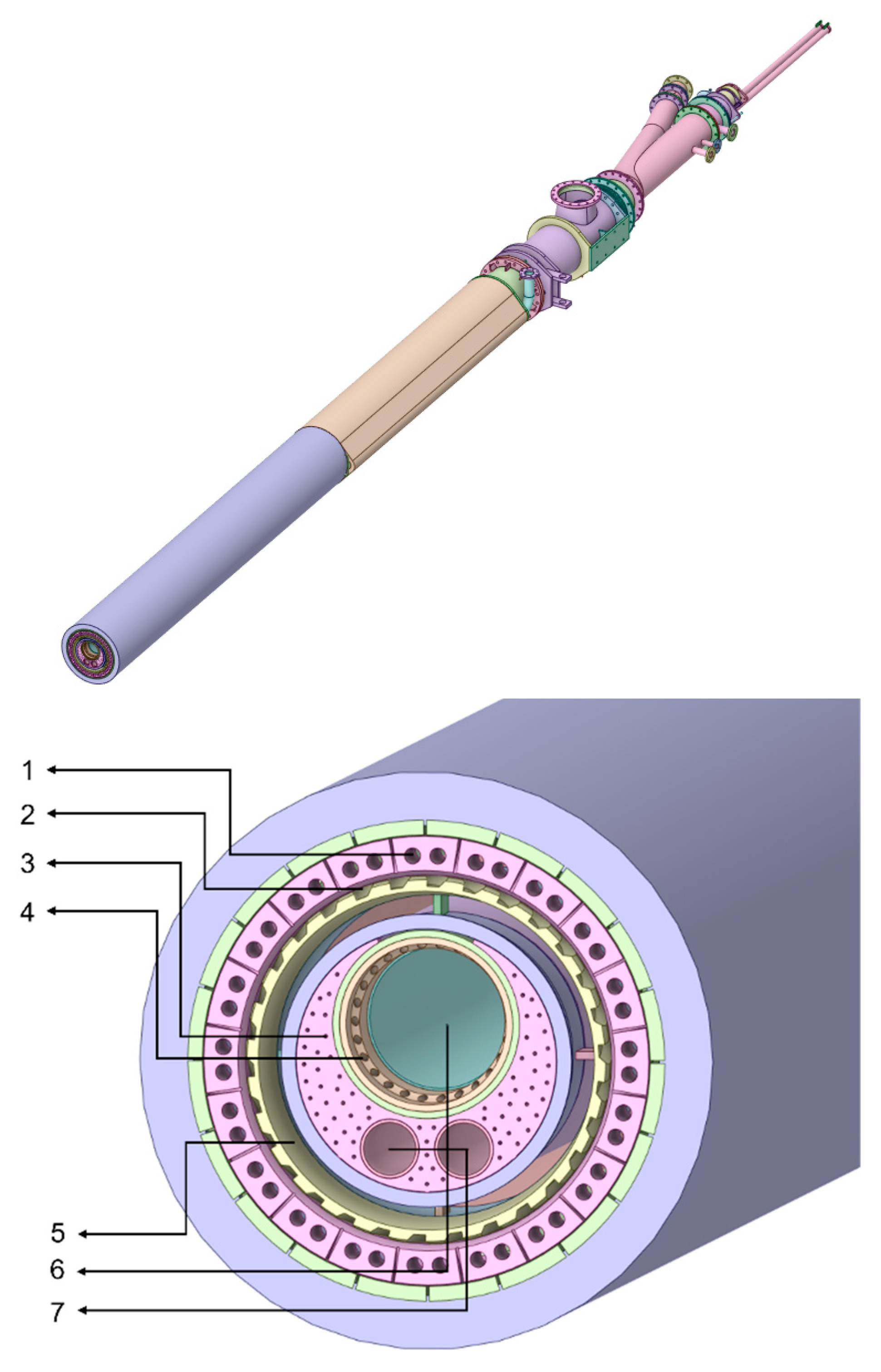

Kiln model geometry

Figure 1 shows the geometry of the burner and burner tip. The burner is focused on solid fuel combustion, with an annular inlet for fossil fuel (5), a larger central circular inlet for solid alternative fuels (6), and two smaller inlet nozzles for the igniter and liquid alternative fuels (7). Primary air can be seen through a combination of the outer circular inlets that feed in the axial air (1), immediately followed by the slots where radial air is fed (2). The solid alternative fuel inlet is also surrounded by small nozzles to improve the mixture of air and fuel prior to burning (4). Lastly, several small inlets constitute cooling air to prevent damage to the burner end plate (3).

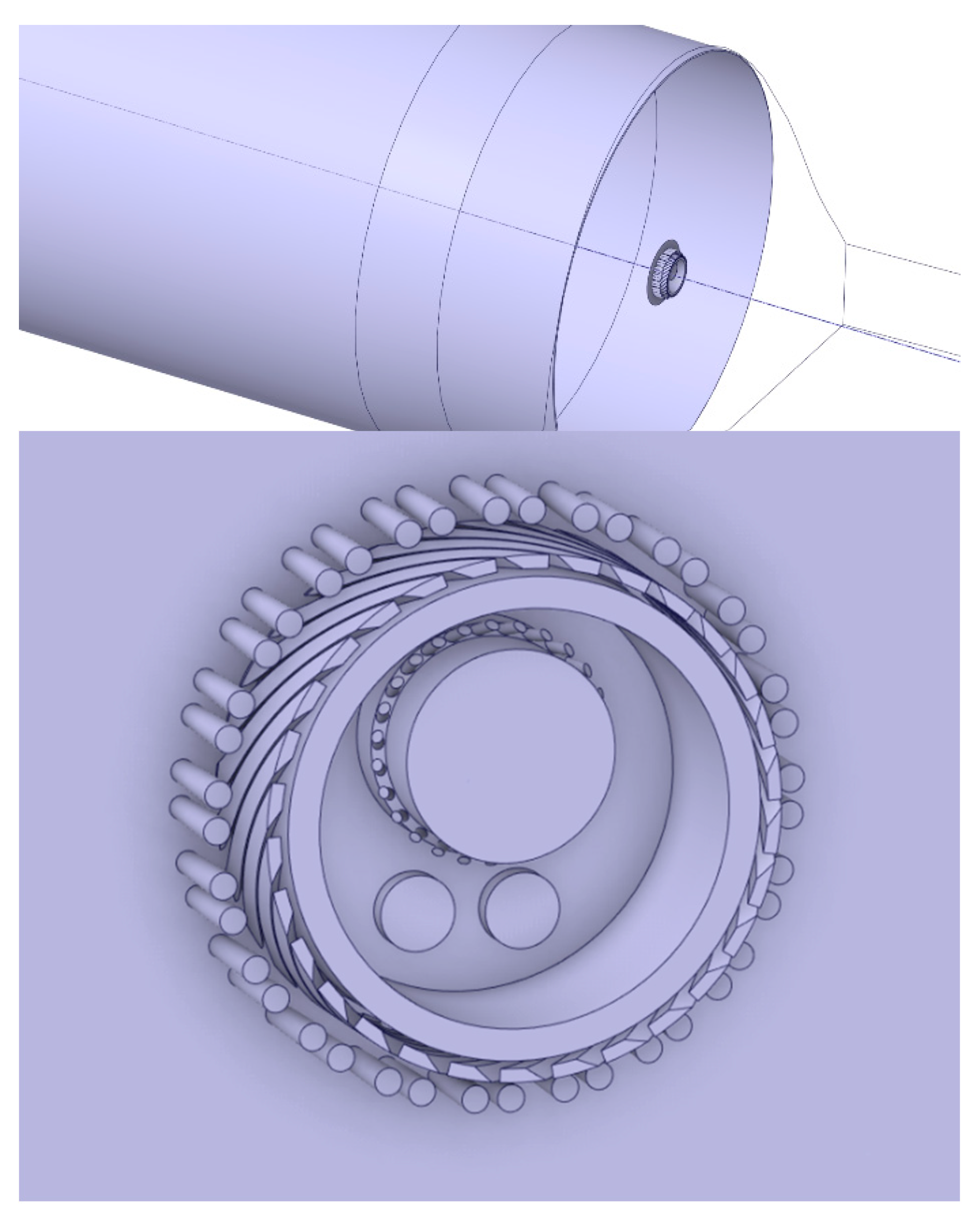

Taking this geometry, the fluid volume within is extracted and combined, in order to produce a continuous solid, depicted in

Figure 2. The cooling air nozzles were removed for simplification, as the amount of air injected is insignificant and does not impact flame shape.

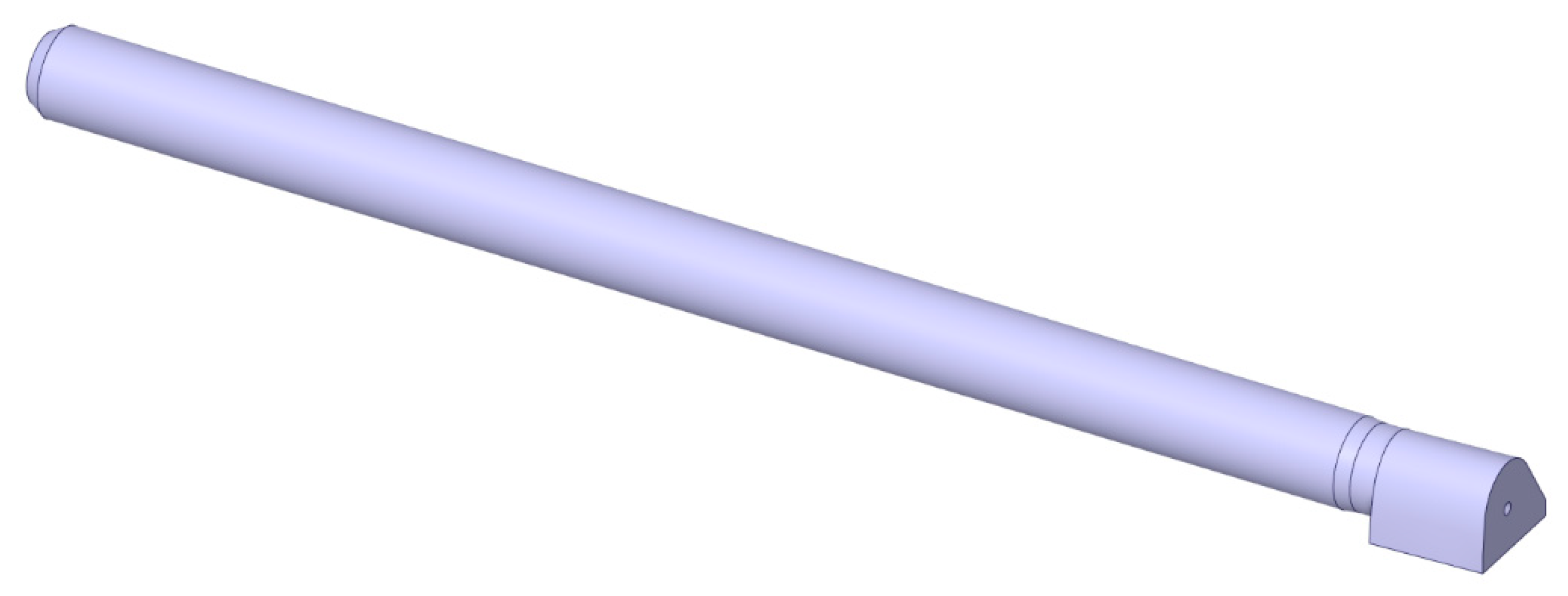

Lastly, the kiln and burner geometries were combined with the clinker cooler hood, yielding the final simulated geometry, depicted in

Figure 3. In addition to the specified burner inlets, on the right end of the geometry is the clinker cooler hood, where the preheated secondary air enters the system. The hot flue gases resulting from the combustion process then exit the domain at the leftmost boundary of the domain, which represents the boundary between the rotary kiln and the fume hood at the bottom of the preheater tower.

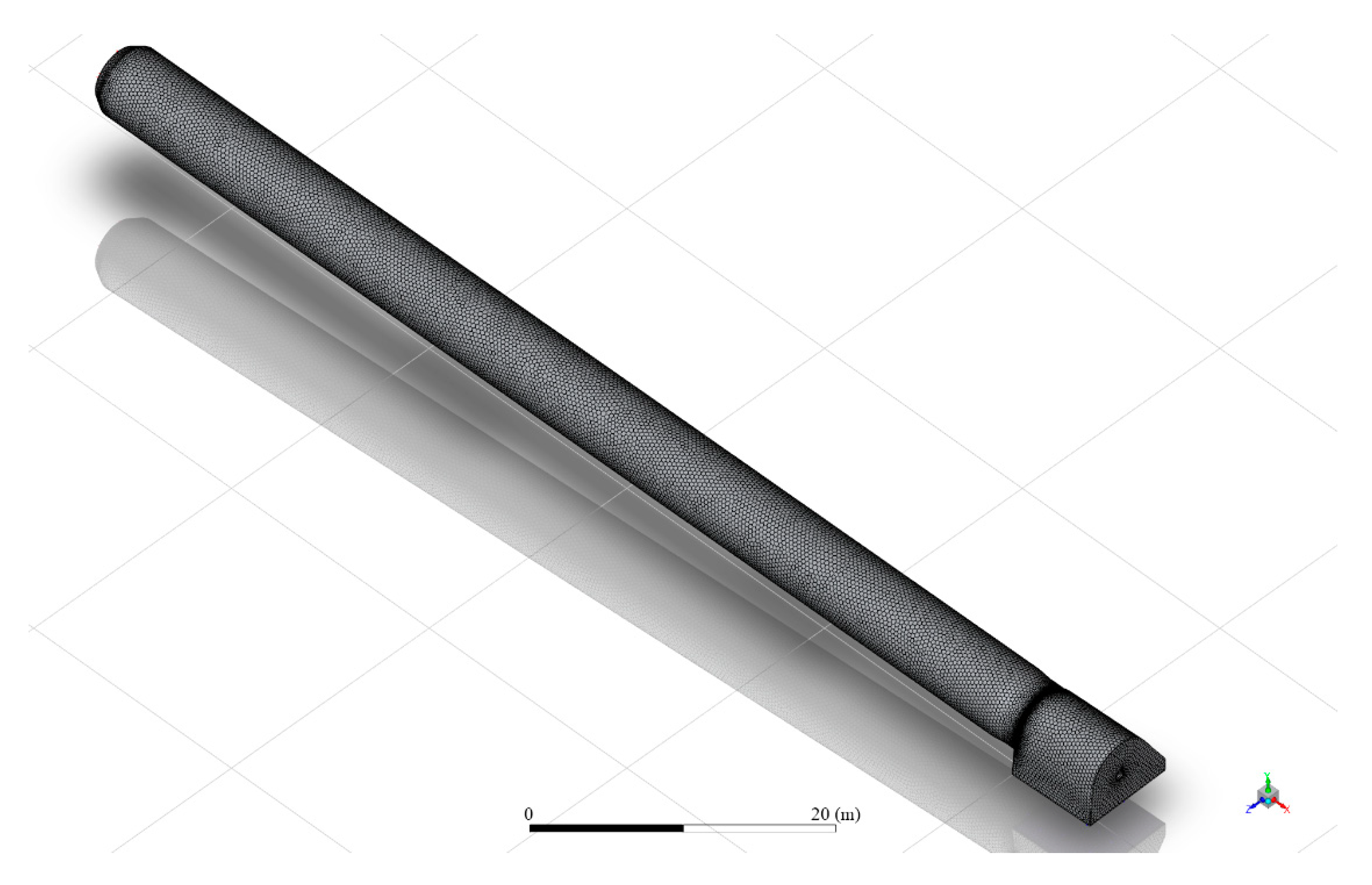

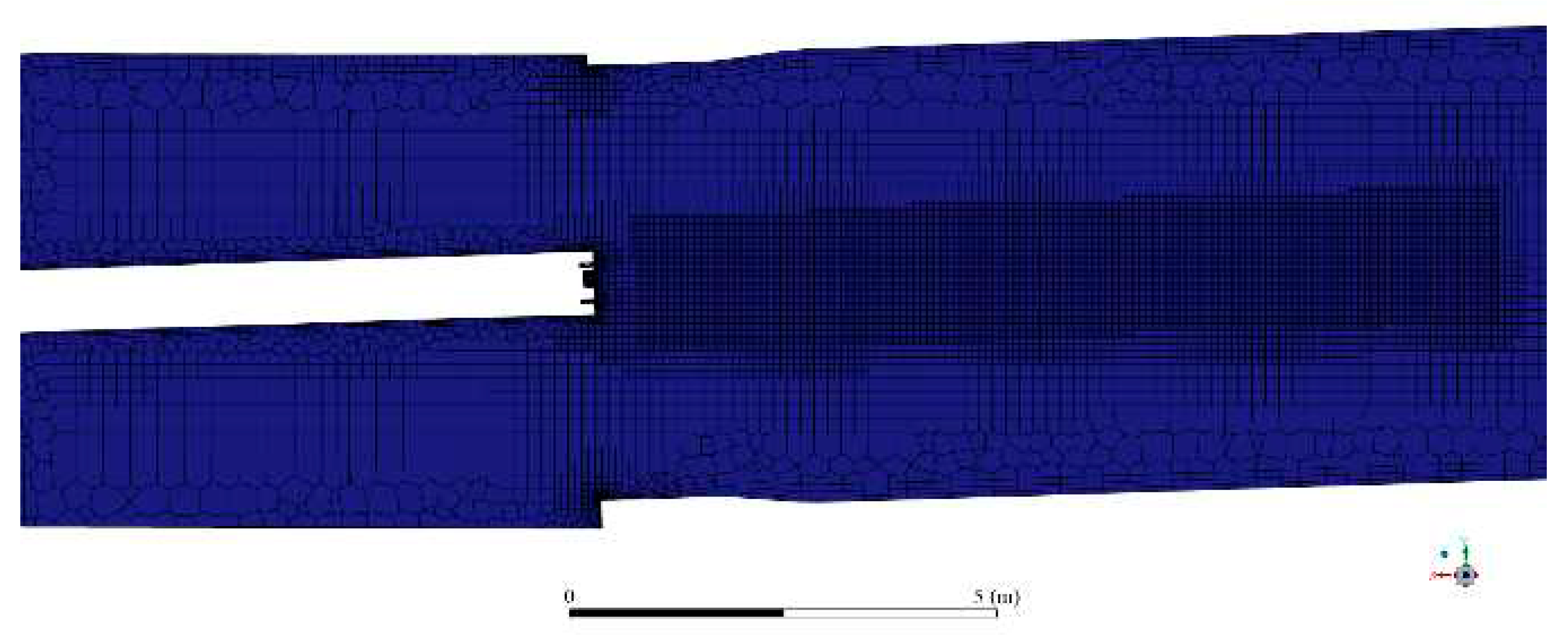

The volume was then discretized into a mesh, depicted in

Figure 4.

The volume was processed in Fluent Meshing, yielding a mesh with 1.2 million cells and a minimum orthogonal quality of 0.2, making it adequate for CFD simulation.

Figure 5 shows a cut along the kiln length. It shows a poly-hexcore mesh, with inflation near the walls and a body of influence (BOI) in the flame area. The body of influence is an important technique to improve resolution in critical areas, thus helping convergence while simultaneously keeping computational demands to an optimum value. In this case, the BOI increases the resolution in the flame area, where the complex combustion phenomena occur.

Turbulent combustion model

The turbulent flow field was modeled by employing the k-ω with shear stress transport (SST) model [

18,

19]. Radiative heat transfer was modeled using the Discrete Ordinates method [

20,

21], and the absorptivity of the flue gas mixture was modeled by the weighted-sum-of-gray-gases (WSSG) [

22].

The combustion of solid fuels is a mixture of complex phenomena, with increasing complexity associated with multiple fuels. In the current model, fossil and alternative solid fuels were introduced as the main combustible species in the CFD domain. A Euler-Lagrange combined model was chosen to describe its behavior, where the gas phase is described by the Euler equations and the solid particles moving through the gas are described by the Lagrangian equation of motion. The two phases interact with each other, exchanging momentum, heat and mass.

The behavior of the discrete phase is defined by a series of physical-chemical processes that begin as soon as the particle enters the domain. Firstly, the particle is heated up by contact with the hot gases, releasing moisture in the form of water vapor. Then, a constant rate devolatilization kinetic law defines the rate of gaseous volatile component release from the particle, while simultaneously decreasing its diameter.

Fuel composition will thoroughly affect combustion performance and is obtained from a combination of ultimate and proximate analyses. These define each of the fuels as a combination of ash, volatile matter, fixed carbon and moisture.

The release of gaseous volatile components generates a model compound

, whose subscripts are a result of the fuel analysis. Devolatilization was assumed to follow a constant rate model. Gas phase combustion follows the oxidation of the volatile model compound according to:

where the reaction rate is calculated between the minimum between the turbulent mixing rate (

) and the Arrhenius kinetic rate law (

), as follows:

where

is the pre-exponential factor,

is the activation energy,

is the concentration of reactant

to the power of

. The turbulent mixing rate is usually described by the Magnussen formula:

where A and B are the model coefficients and typically equal to 4 and 0.5, respectively. The overall reaction rate is chosen from the minimum value between the turbulent mixing rate and finite-rate Arrhenius kinetic.

The gaseous volatile component will then combust, generating the expected combustion products and pollutants, while an additional model governs soot formation and subsequent combustion.

Pollutant generation is also considered, namely SO

2 derived from the fuels’ Sulphur content and NO

X as a combined effect of fuel nitrogen and thermal mechanisms. The thermal NOx model is a postprocessing calculation performed after combustion, due to the low concentrations of NOx in the combustion system, which means that NO

X chemistry usually presents a negligible effect on the flow field. It follows the extended Zeldovich mechanism, while simultaneously considering an N

2O intermediate compound and interaction with turbulence and species [

23].

The kinetic constants were for the reactions were obtained from a critical analysis of literature data published by Hanson and Salimian [

24]. The net rate of formation of NO is given by the following equation:

Soot formation and combustion are solved by considering the one-step Khan and Greeves model [

25], which details a single transport equation for the soot mas fraction, as follows:

where

is the soot mass fraction,

represents the turbulent Prandtl number for soot transport and

represents the net rate of soot generation. The kinetics of soot combustion are given by the Magnussen and Hjertager model [

26], according to:

where

is a constant in the Magnussen model,

are the mass fractions of oxidizer and fuel, and

are the mass stoichiometries for soot and fuel combustion. Additionally, the rate of soot combustion is chosen as the minimum value obtained between

and

.

Finally, heat loss at the kiln walls is modeled by a combination of convection and radiation boundary conditions.

Tested scenarios

The CFD simulations performed for the kiln system are based on the principle of diagnosing the baseline operating conditions and attempting their optimization through fine-tuning operational parameters. Preliminary results suggest that there is not enough oxygen available for combustion in a critical area of the kiln (sintering zone), which prevents complete combustion from occurring. These preliminary results will be validated by simulation.

In order to attempt optimization of the solid fuel combustion, the mass flowrate of secondary air was slightly increased to better aerate the oxygen-deprived flame. Fuel composition and all other relevant parameters were kept constant, with the purpose of isolating the effect of the additional secondary air mass flowrate.

Table 2 summarizes the differences in operating/boundary conditions for the two different simulations (see fuels specifications in

Table 1).

3. Results and Discussion

As previously mentioned, two case scenarios were simulated for the combustion process of petcoke and RDF within a rotary cement kiln.

Temperature and velocity profiles

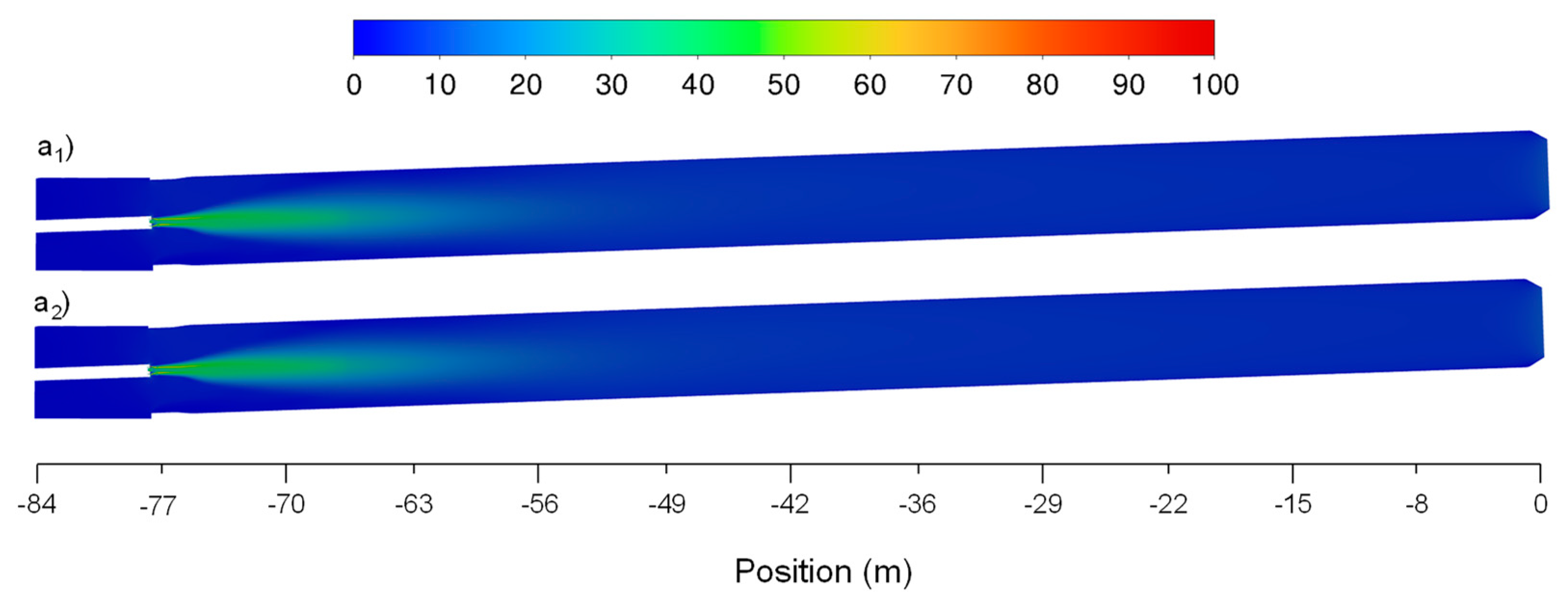

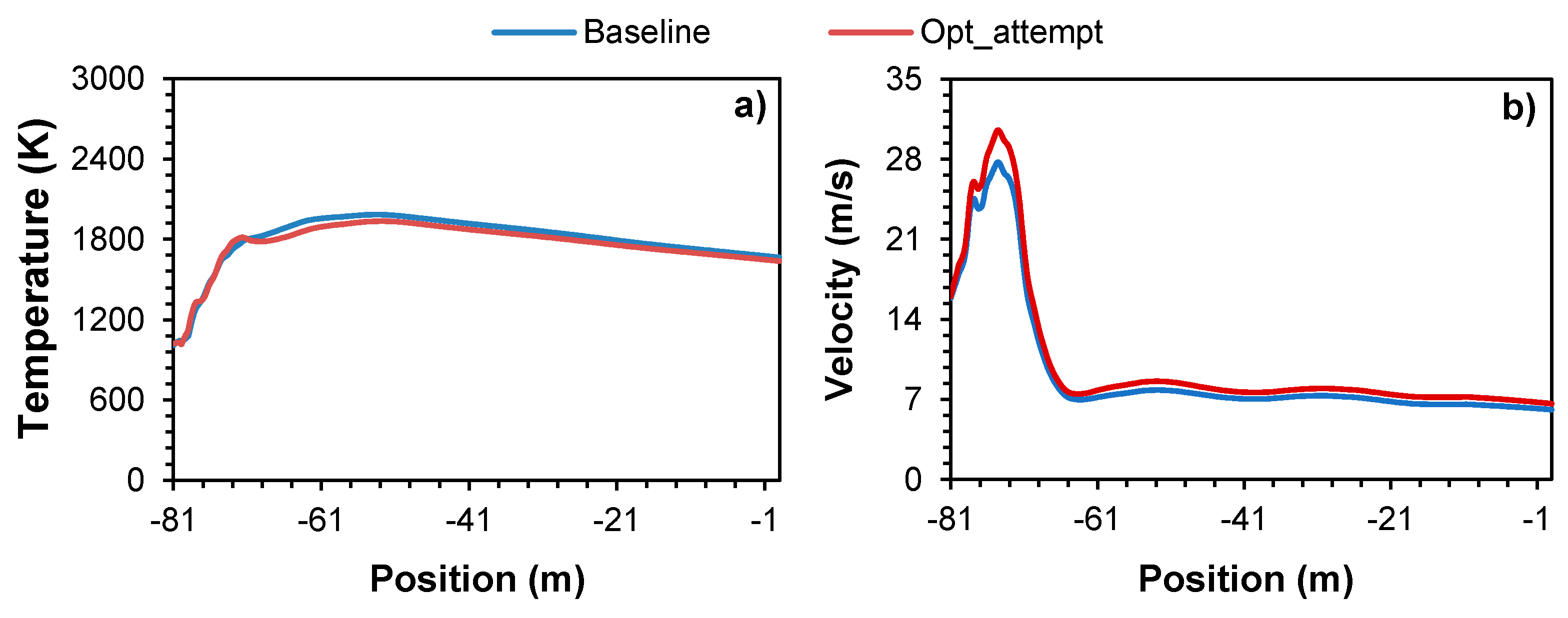

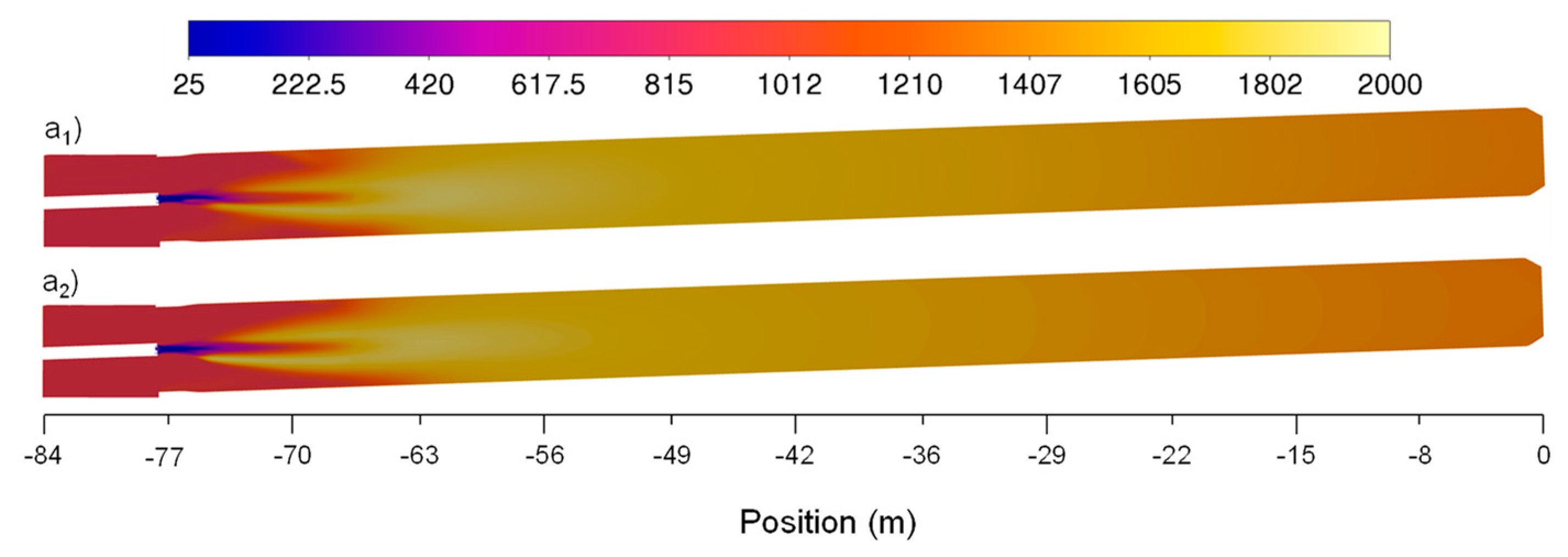

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 9 show the temperature and velocity average values and axial distribution fields along the rotary kiln, respectively. Since the axial distribution profiles are not easy to distinguish,

Figure 8 and 10 show the absolute difference between the two case scenarios for temperature and velocity axial distribution, respectively, highlighting their main differences.

Figure 6a shows that overall, the temperature profile reaches slightly lower values when the secondary air mass flow rate increases. However, the temperature difference is not significant between the two cases, showing a maximum absolute difference of 74 ºC, at -65m that corresponds to a deviation of 3.9% and 3.8% from the maximum temperature for the baseline and optimization case scenarios, respectively. Additionally, due to the higher secondary mass flow selected for the combustion optimization the maximum temperature location is reached with a marginal delay of 0.7m (correspondent to 0.9% of the kiln length), at -53m. Hence, it can be considered that the combustion process was not negatively affected. Observing

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 it is possible to identify the body of the flames in the two case scenarios and the absolute difference between them, respectively. The area that denotes a higher temperature absolute difference intensity is observed between -73m and -55m, which corresponds to the main body of the flame location and kiln walls. Similar temperature trends were observed in the works of Liedmann et al. [

7], Pieper et al. [

11] and Huang et al. [

12].

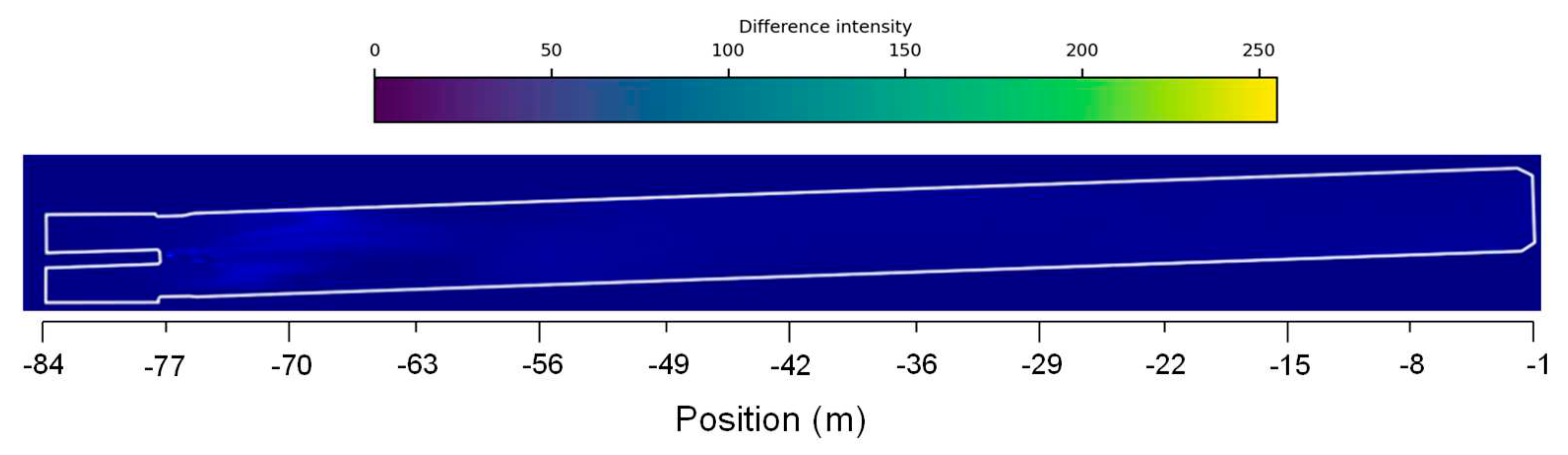

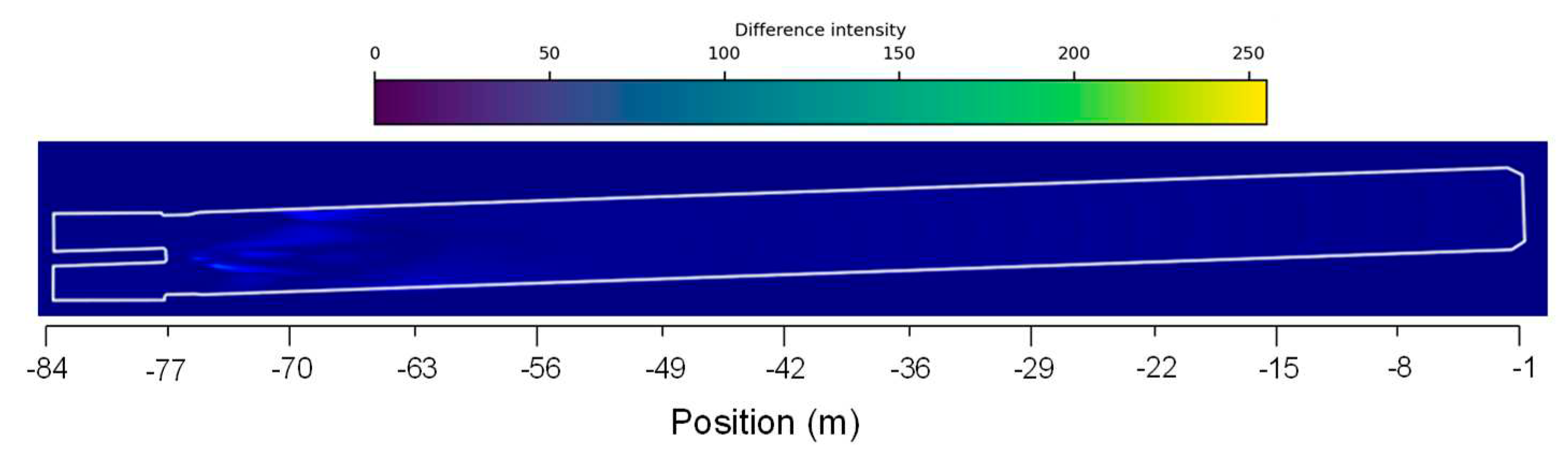

Figure 6b shows that, as expected, the velocity profile reaches higher values when the secondary air mass flow rate increases, being the maximum absolute difference of 2.85m/s located at -74m. The flow velocity for both scenarios stabilizes to some degree at approximately -65m having small oscillations between 6m/s and 8m/s. Observing

Figure 9 it is possible to identify that the flow reaches higher velocities in the area where the flame is located (higher temperature location) for the two case scenarios. Similar to

Figure 8,

Figure 10 denotes that the higher flow velocity absolute difference intensity is observed also between -75m and -55m which, showing a higher difference located in the center of the flame and kiln walls. Similar flow velocity trends were also observed in previous works [

7,

11,

12].

Figure 9.

Baseline and optimization attempt case scenarios for velocities (a1, a2) axial distribution fields along the rotary kiln, respectively.

Figure 9.

Baseline and optimization attempt case scenarios for velocities (a1, a2) axial distribution fields along the rotary kiln, respectively.

Figure 10.

Absolute difference between the two case scenarios of velocity distribution fields along the rotary kiln.

Figure 10.

Absolute difference between the two case scenarios of velocity distribution fields along the rotary kiln.

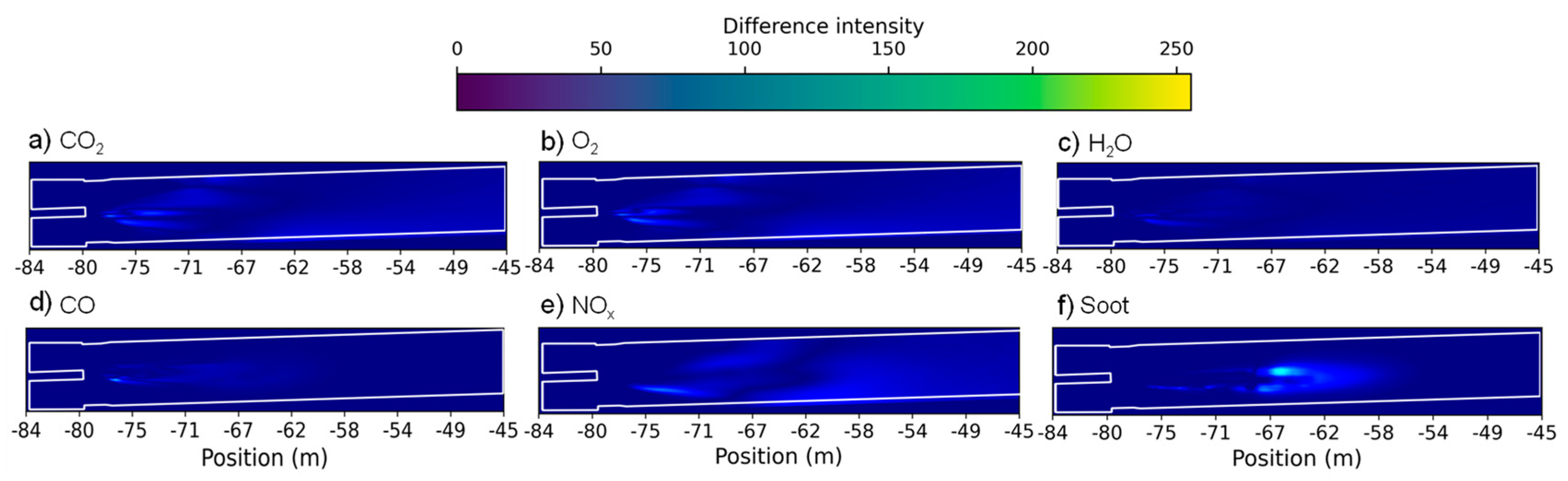

Chemical species and pollutants

Combustion is a fundamental process in the cement industry, where achieving a complete process is essential for maximizing energy efficiency and minimizing harmful emissions. When the fuels (petcoke and RDF, in the present case) burn in the presence of oxygen, the combustion process typically results in the formation of CO

2 and H

2O vapor as primary by-products. However, the ratio of fuel to air can significantly impact the outcome of this thermal conversion process. In a lean combustion regime, the higher amount of oxidant facilitates a more thorough and efficient combustion process. The excess air allows for the complete oxidation of the fuel, resulting in a higher conversion of the fuels and a reduced formation of pollutants such as CO, soot and unburned hydrocarbons [

27]. These occurrences can be observed in

Figure 11 and

Figure 13 and later in

Table 2.

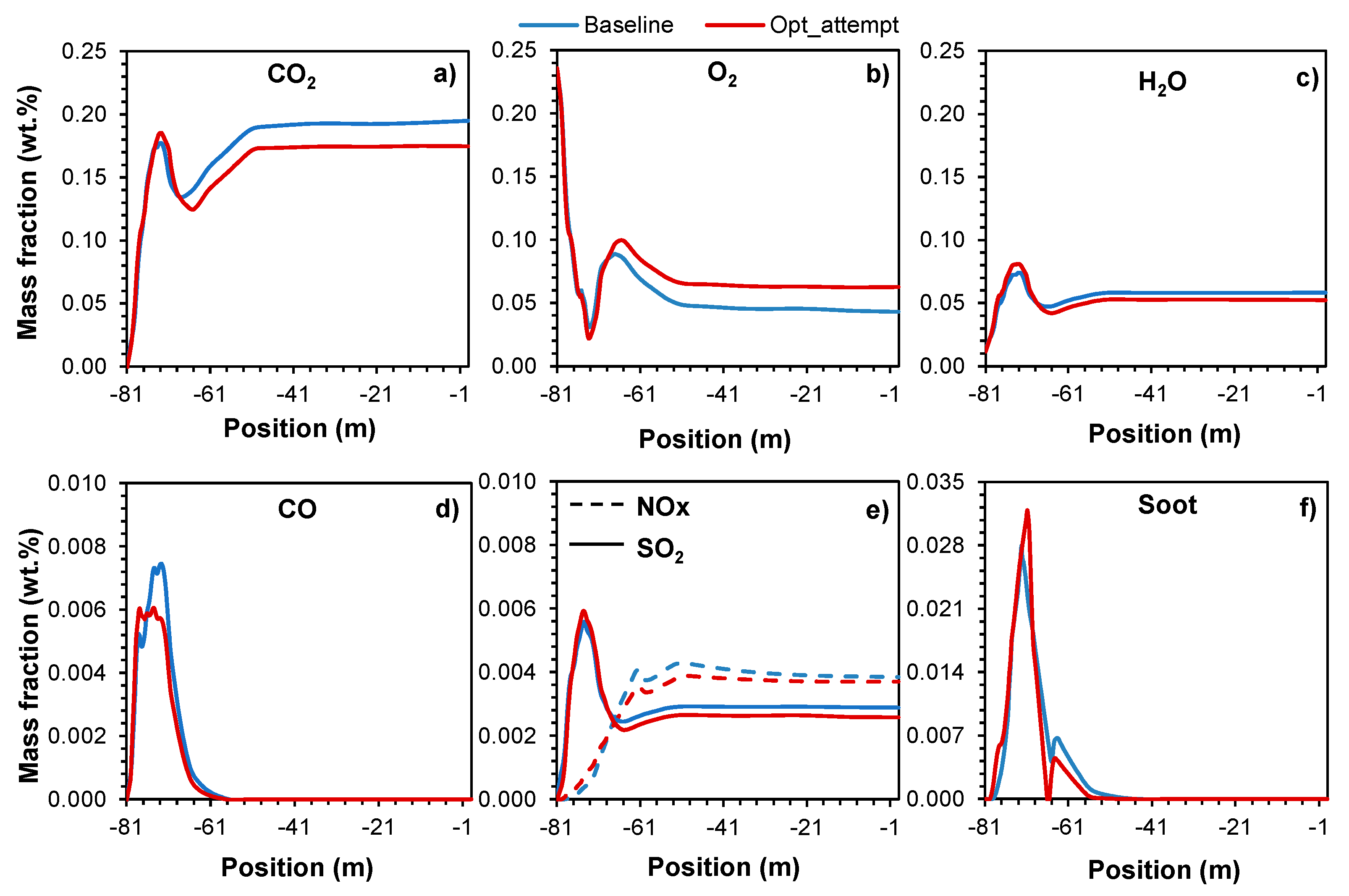

Figure 11 shows the mass fraction axial distribution of the most important species (CO

2, O

2, H

2O, CO, SO

2, NOx and soot) during the combustion process regarding the two case scenarios.

Figure 11 shows that it is possible to distinguish two combustion stages. Initially, the increase in CO

2 (

Figure 11a), H

2O (

Figure 11c) and CO (

Figure 11d) is primarily a result of the fuels devolatilization, i.e., when in contact with high temperature, the volatile matter present in the fuels starts to be immediately released and, due to the lack of O

2 (

Figure 11b), incomplete combustion occurs (also inherent to the presence of CO). Relating this phenomenon to

Figure 6a and 7, it can be seen that between -81m and -69m the body of the flame starts to form and the temperature starts to increase. Immediately afterwards, during the second stage of combustion, a further rise in CO

2 levels is observed. This phenomenon is attributed to the intense combustion of the remaining fuels and oxygen, where a greater amount of heat is released, leading to the formation of a localized high-temperature zone (flame area) at the center of the kiln (located between -69m and -41m). Finally, the consumption of oxygen reaches a state of stability, leading to a relative equilibrium in the levels of CO

2, CO, H

2O and the flow field (latter also observed in

Figure 9). These events were also observed in the work of Huang et al. [

12]. Comparing specifically the results of the simulated case scenarios, when the air mass flow increases (making the mixture leaner), more oxygen is available to achieve complete combustion. Under these conditions, there is a more complete oxidation of the fuel, resulting in an initially slightly high production of CO

2 and H

2O vapor while, simultaneously, the production of O

2 and CO is further reduced. It is also important to note that air is composed of about 79% nitrogen (N

2) by volume. Being N

2 a generally inert element in the combustion reaction, it will effectively dilute the concentration of the released gaseous species in the combustion products, decreasing their concentration in the exhaust gases, as observed in

Figure 11a–d. Additionally, although nitrogen is mostly inert, at high temperatures (above ~1800K) oxygen and nitrogen can react to form various nitrogen oxides (NOx). High temperature is a key factor that contributes to the formation of NOx [

27]. This phenomenon can be observed relating to

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 11e. Overall, the higher concentration of NOx is located in the area where the temperature is higher (center of the flame) and, additionally, the case scenario with higher temperature (less available air) results in higher NOx emissions, more denoted at -61m in

Figure 11e. Similar results were also observed by Huang et al. [

12].

SO

2 emissions primarily rely on the sulfur content within the fuel rather than the combustion regime. Regardless of whether the combustion conditions are lean or rich, sulfur is nearly entirely oxidized to SO

2 during the combustion process. Therefore, altering the air-fuel ratio by augmenting the air mass flow would have minimal impact on the quantity of SO

2 generated, assuming the sulfur content in the fuels remain constant [

27]. Nonetheless, the concentration of SO

2 in the flue gas could be lower under lean conditions, similar to the situation with the other released gaseous species, owing to the dilution effect resulting from the increased amount of nitrogen and other inert components in the excess air. The dilution effect is observed in

Figure 11e.

The formation of soot, or particulate matter, is primarily influenced by the composition of the fuels and the equivalence ratio during combustion. Under lean combustion conditions, where the air mass flow is increased, the formation of soot tends to decrease. This is due to the more oxygen available to oxidize the fuels completely to CO

2 and H

2O vapor, reducing the formation of partially oxidized hydrocarbons and carbon particles. Also, the excess air can also oxidize any soot particles that are produced, further reducing soot emissions.

Figure 11b, f show the described relation between O

2 and soot particles formation.

Figure 12 shows the absolute difference between the two case scenarios of CO

2, O

2, H

2O, CO, NOx and soot distribution fields along the rotary kiln. Since the formation of SO

2 depends mainly on the composition of the fuels [

27], the discussion of this species on this topic was considered not relevant. Differently from what was observed for the temperature and velocity distribution fields (

Figure 8 and

Figure 10), and regardless of being located in the flame region, there are two defined areas that denote a higher absolute difference intensity, approximately separated at -69m. Relating this event to

Figure 11, this region corresponds not only to where both case scenarios present similar results, but also to the region that separates the two combustion stages. In the region of the first combustion stage the absolute difference intensity corresponds to the lower formation of CO (where partial combustion occurs), higher consumption of O

2, higher production of CO

2, H

2O and soot for the case scenario where the air mass flow was increase, whereas in the region of the second combustion regime the opposite trends are observed. Additionally, it is also possible to observe that complete combustion occurs, which can be easily related to the differences detected mostly in the production of CO

2 and soot and absence in the production of CO. Regarding

Figure 12e, since the temperature is generally lower for the referred case scenario, the absolute difference intensity corresponds to the lower formation of NOx. Once again it is also curious to observe the inverse relationship between O

2 (

Figure 12b) and soot (

Figure 12f) formation. The regions where lacks oxygen correspond to the regions where the production soot increases.

Figure 12.

Absolute difference between the two case scenarios of a) CO2, b) O2, c) H2O, d) CO, e) NOx and f) soot distribution fields along the rotary kiln.

Figure 12.

Absolute difference between the two case scenarios of a) CO2, b) O2, c) H2O, d) CO, e) NOx and f) soot distribution fields along the rotary kiln.

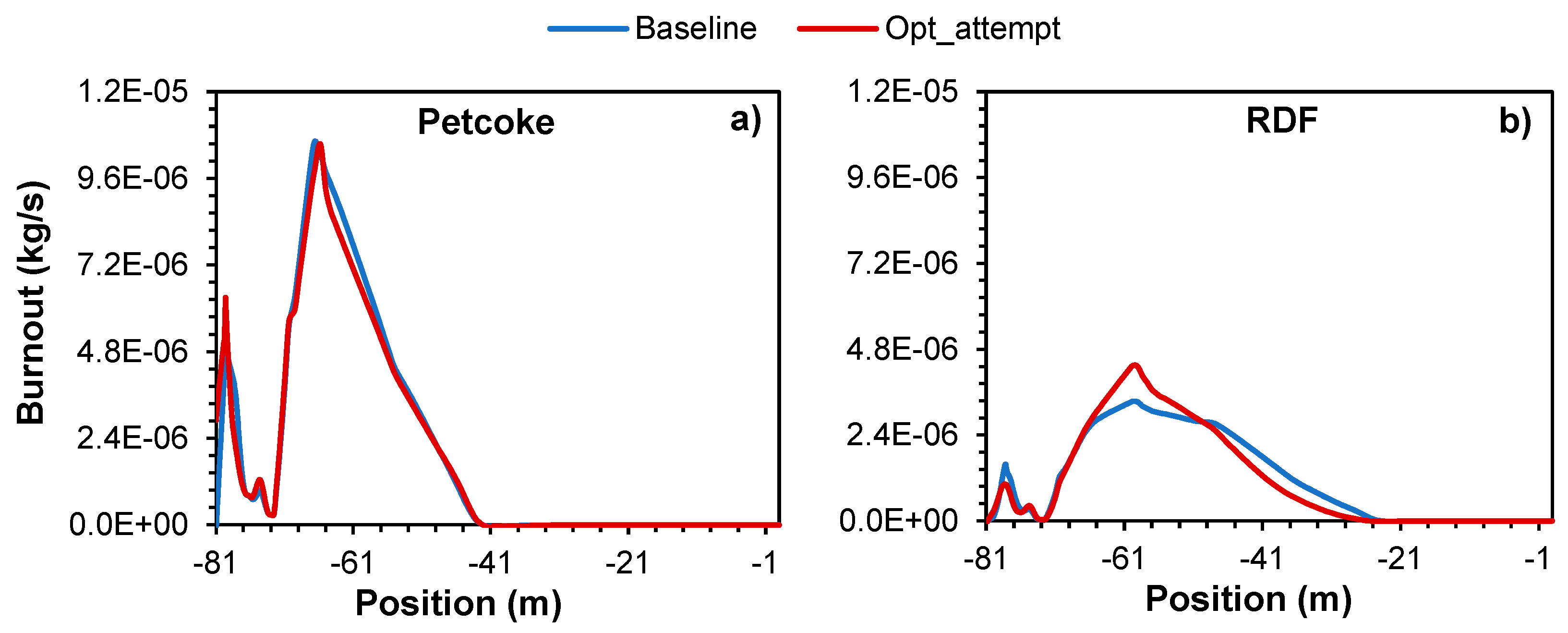

Solid fuels combustion and combustion efficiency

Particle burnout refers to the complete combustion of solid fuel particles, leaving no unburned material behind. This parameter represents a crucial aspect of combustion systems, ensuring maximum energy efficiency and minimal emissions [

27].

Figure 13 shows the axial distribution of the burnout rate of petcoke and RDF particles.

Figure 13.

Absolute difference between the two case scenarios of a) CO2, b) O2, c) H2O, d) CO, e) NOx and f) soot distribution fields along the rotary kiln.

Figure 13.

Absolute difference between the two case scenarios of a) CO2, b) O2, c) H2O, d) CO, e) NOx and f) soot distribution fields along the rotary kiln.

For the case of petcoke particles (

Figure 13a), it can be considered that the increase of the air mass flow had little effect on the burnout, meaning that the combustion of petcoke particles process was marginally affected, regardless the slightly decrease in the temperature at around -61m. On another hand, for the case of RDF particles (

Figure 13b), the excess air ensures a more efficient oxidation of the fuel particles, resulting in a higher and faster conversion of the fuel into gaseous combustion products. This leads to improved energy efficiency and reduced emissions of unburned material and pollutants by facilitating the breakdown of complex fuel molecules and promoting the complete oxidation of solid particles. The reason petcoke burnout rate ends first than RDF (around -41m and -30m, respectively) is primarily due to its higher thermal conductivity and heat content and due to the smaller particle size. Hence, when subject to a high temperature, petcoke will start to decompose and react faster than RDF. Similar results were observed in the works of Pieper et al. [

11] and Ariyaratne et al. [

14].

Table 2 shows the combustion process efficiency for the two simulated case scenarios. It is possible to conclude, for the tested conditions, that increasing the air mass flow by 10% improved carbon conversion efficiency by 3.25%. As a result, a lean combustion regime can lead to higher combustion efficiency as more of the fuel is oxidized. However, this must be balanced against the possibility of increasing emissions of NOx and potential impacts on the combustion operating conditions. Hence, there must be a balance between achieving efficient combustion, minimizing harmful emissions, and maintaining the reliability and performance of the combustion system.

Table 3.

Combustion process efficiency.

Table 3.

Combustion process efficiency.

| Fuels inlet |

| RDF Mass flow (kg/s) |

2.30 |

| CRDF yield (wt.%) |

0.63 |

| Petcoke Mass flow (kg/s) |

0.84 |

| CPetcoke yield (wt.%) |

0.86 |

| C Mass flow (kg/s) |

2.17 |

| Outlet |

| Gas Mass flow (kg/s) |

Baseline |

Optimization |

| Mass flow (kg/s) |

32.72 |

36.09 |

| CO2 yield (wt.%) |

0.19 |

0.18 |

| CO2 Mass flow (kg/s) |

6.33 |

6.55 |

| C Mass flow (kg/s) |

2.01 |

2.09 |

| Efficiency |

92.95 |

96.20 |