Submitted:

03 August 2023

Posted:

04 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials

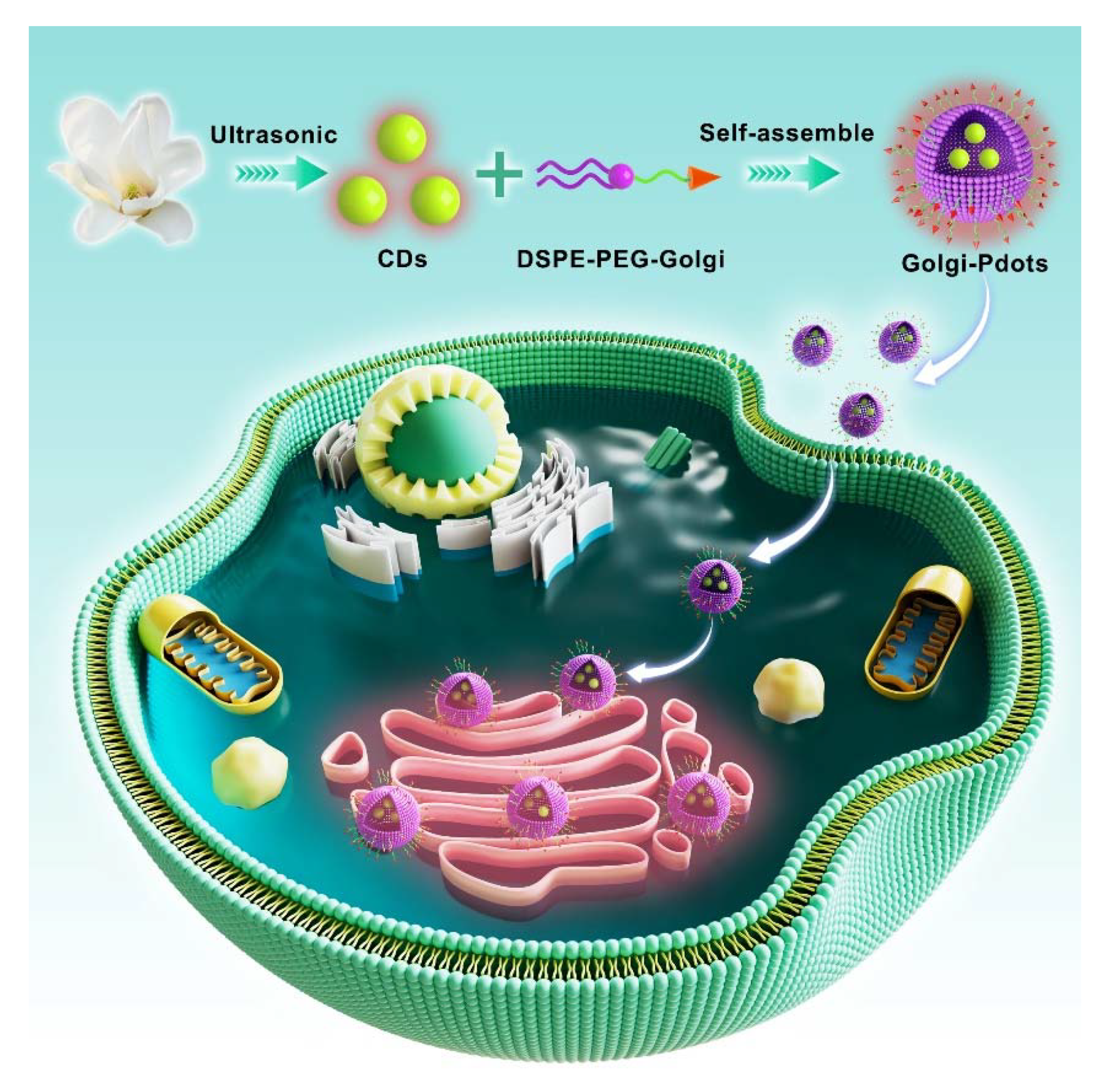

2.2. Preparation of NIR fluorescent CDs

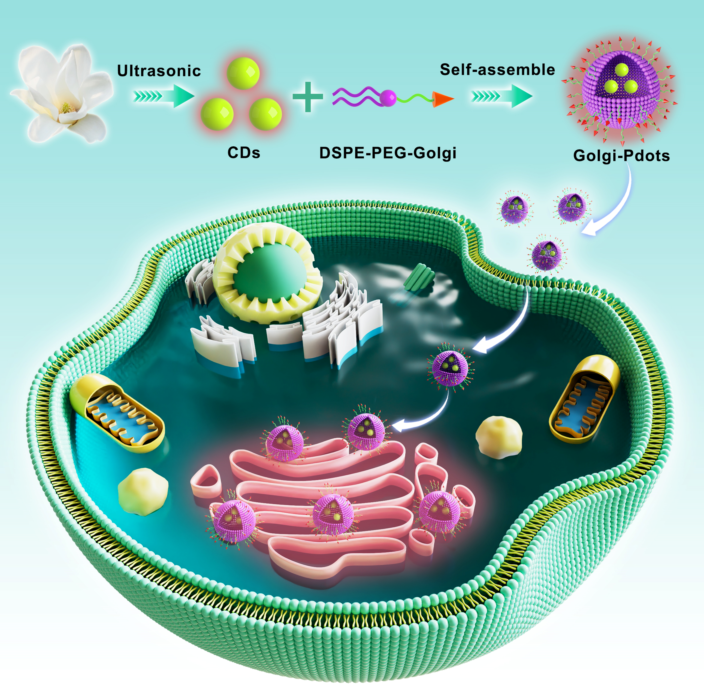

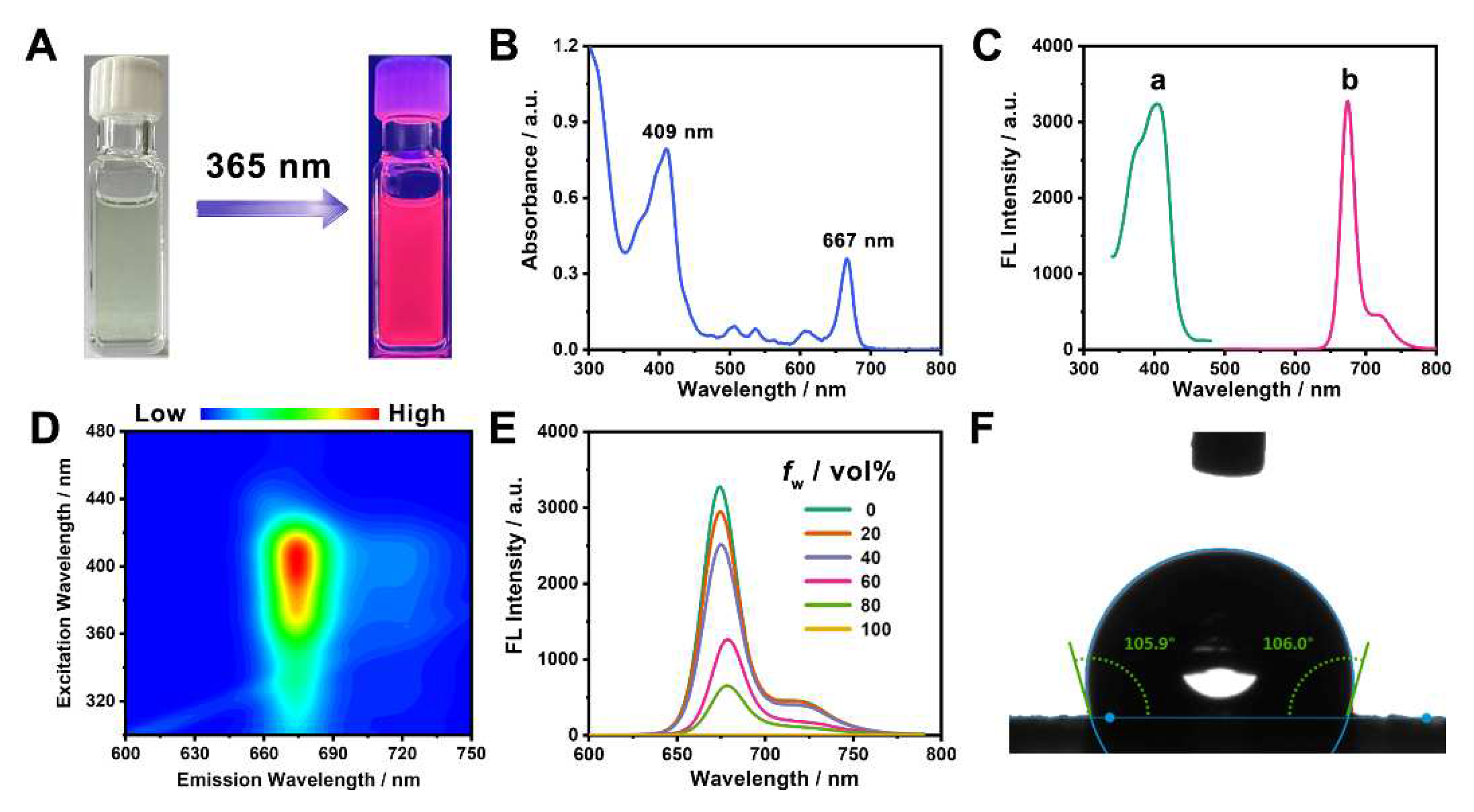

2.3. Fabrication of NIR emissive CDs-encapsulated Golgi-Pdots

2.4. Fluorescent imaging

3. Results and discussions

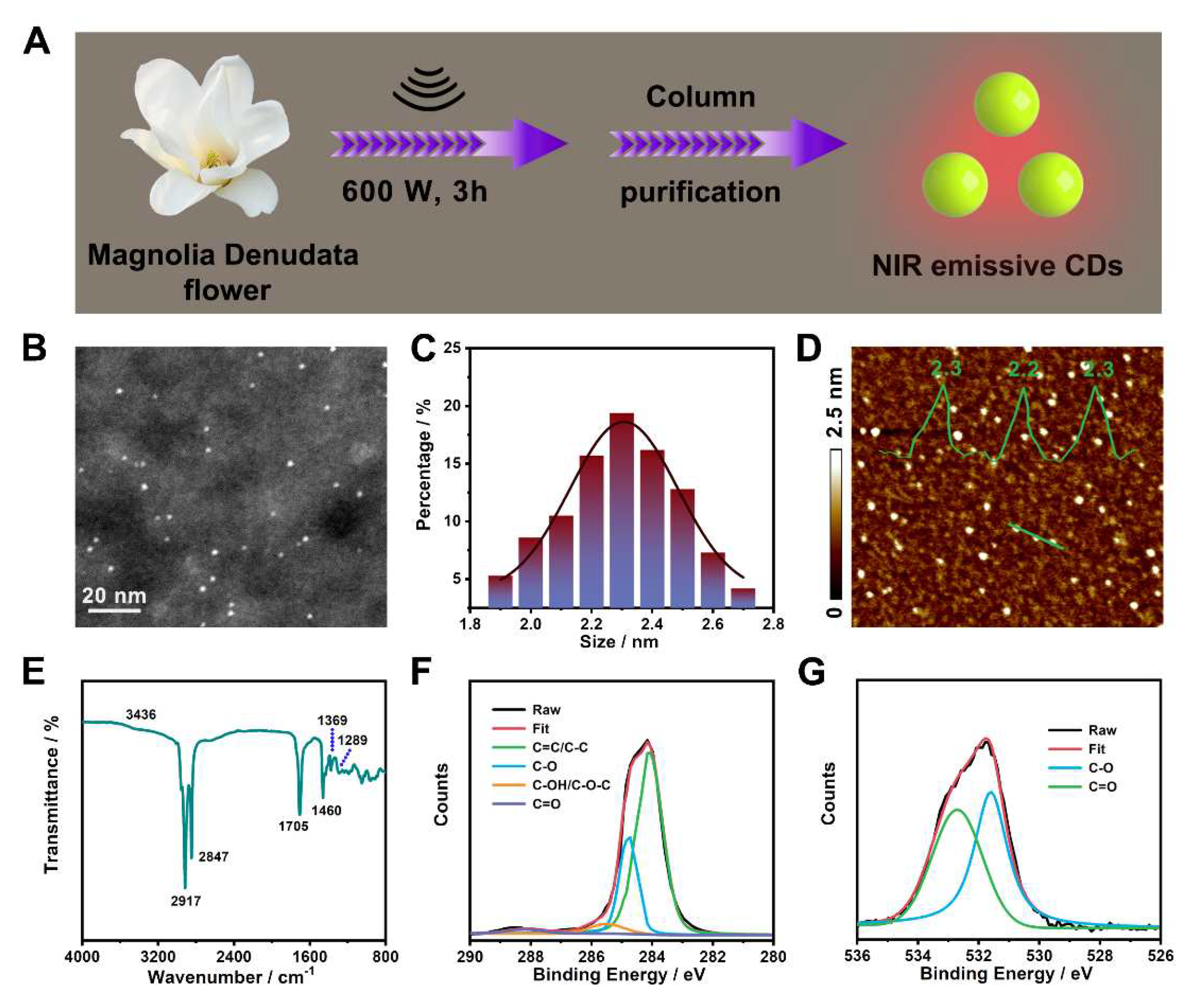

3.1. Preparation and characterization of NIR emissive CDs

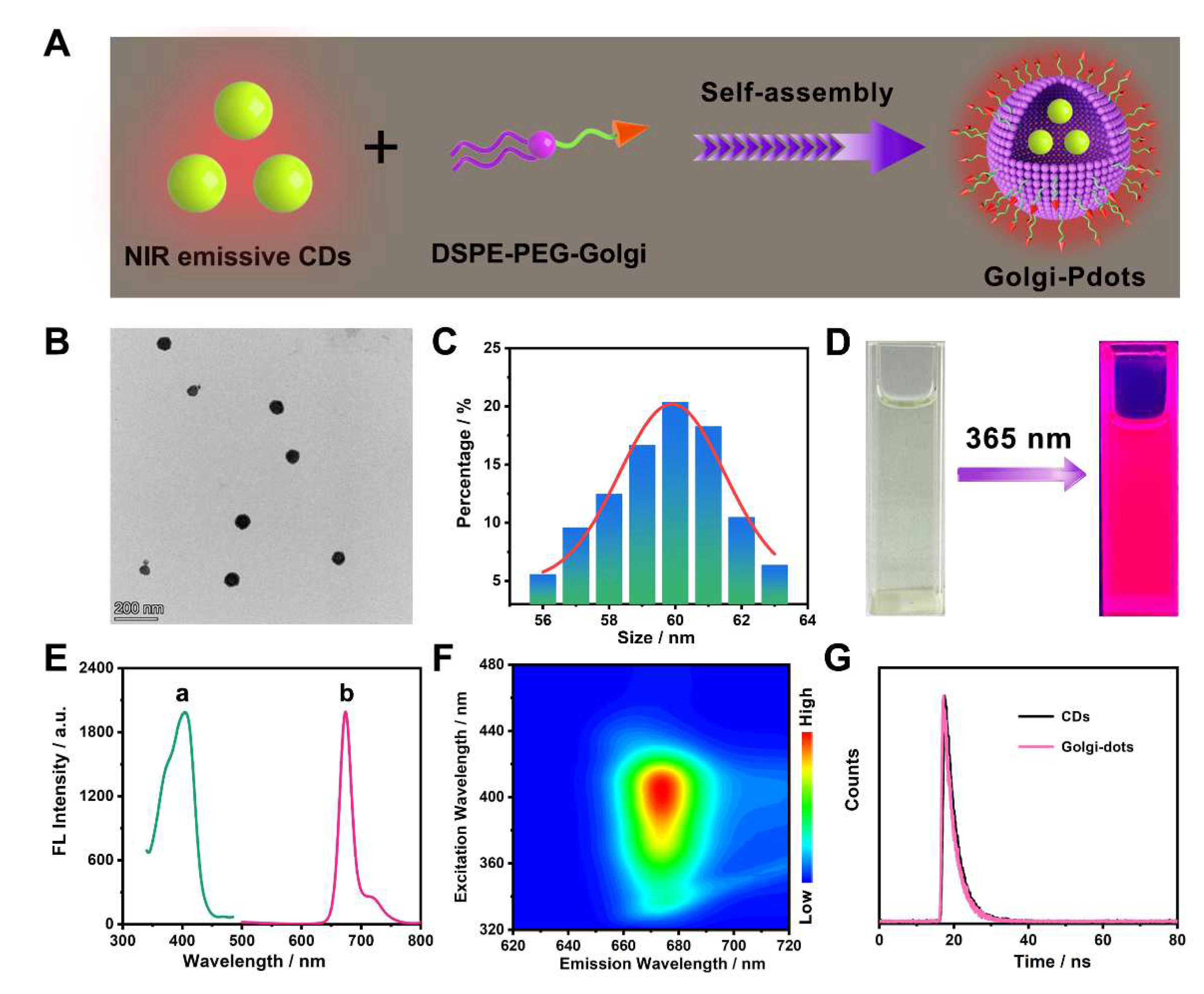

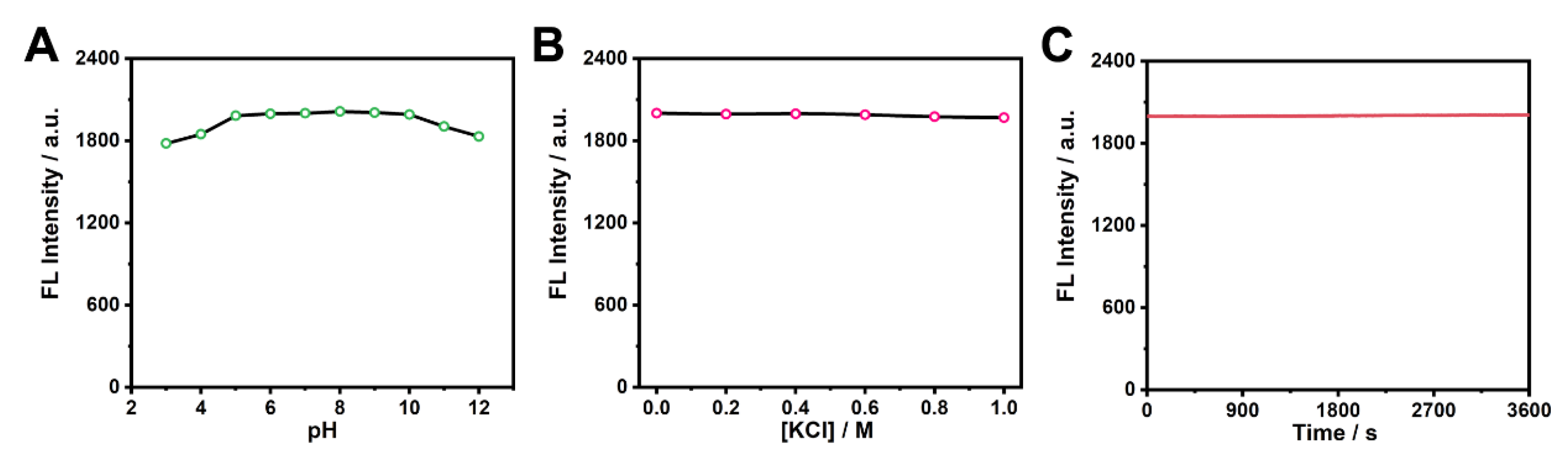

3.2. Fabrication and characterization of Pdots incorporated with CDs

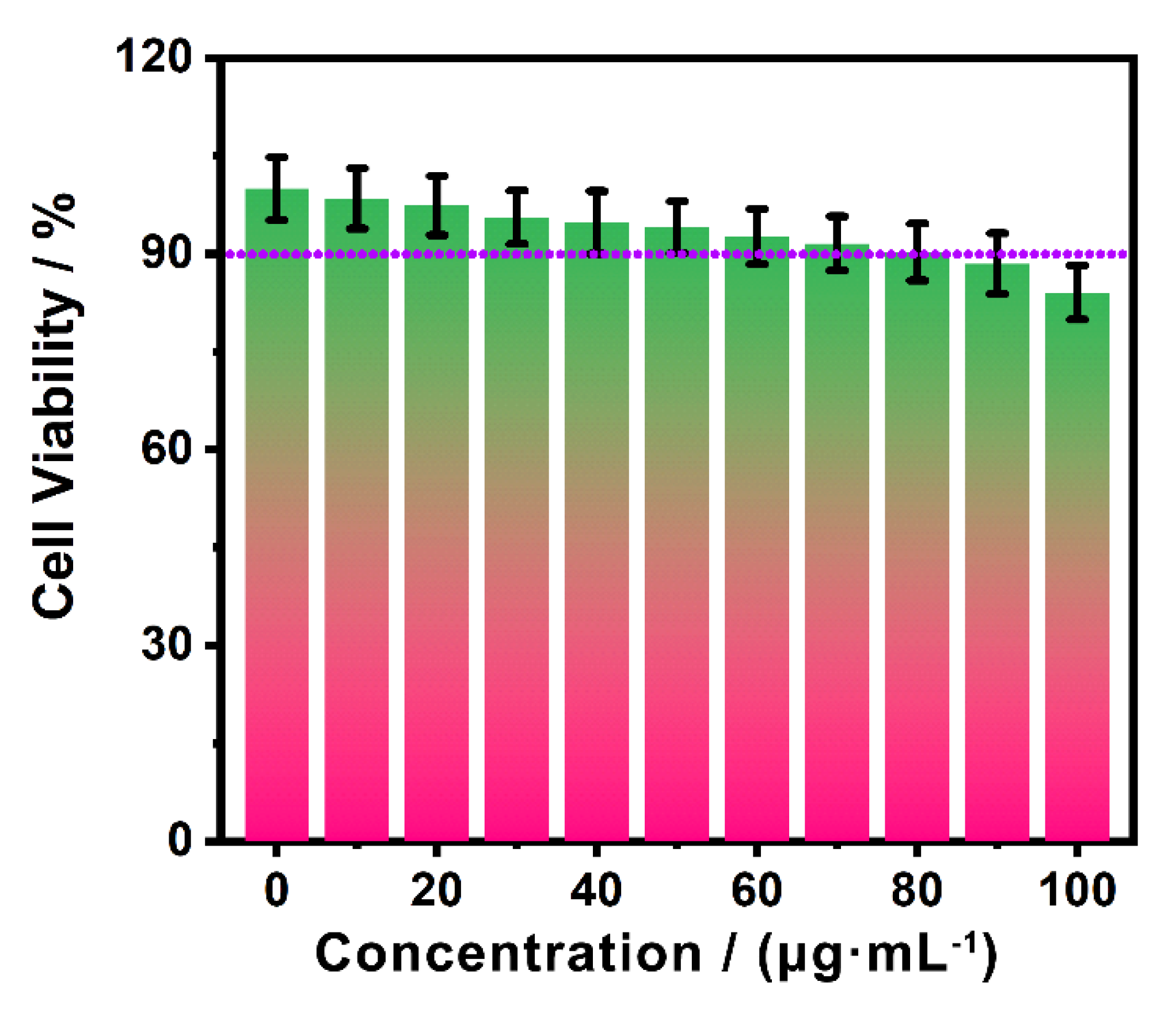

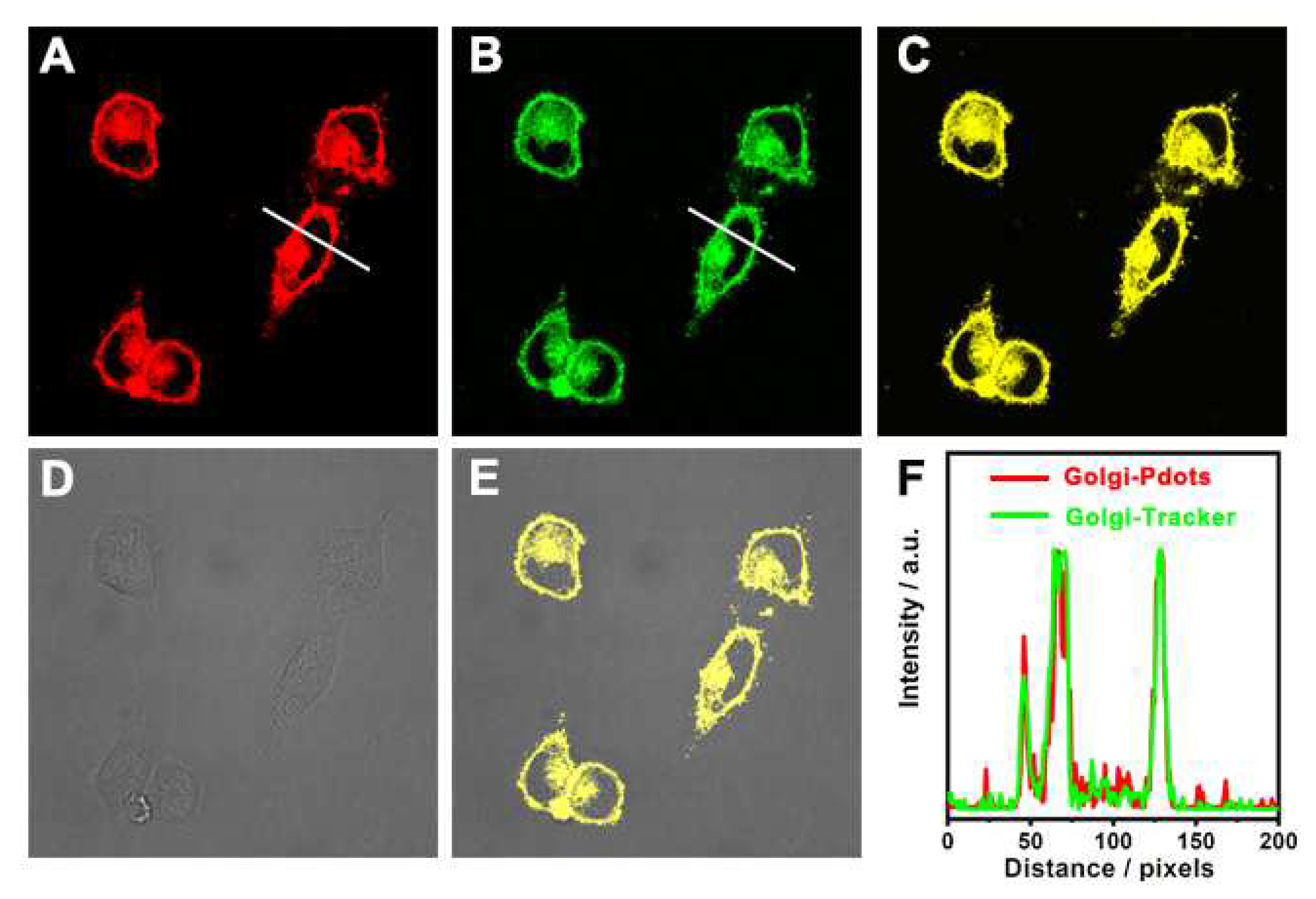

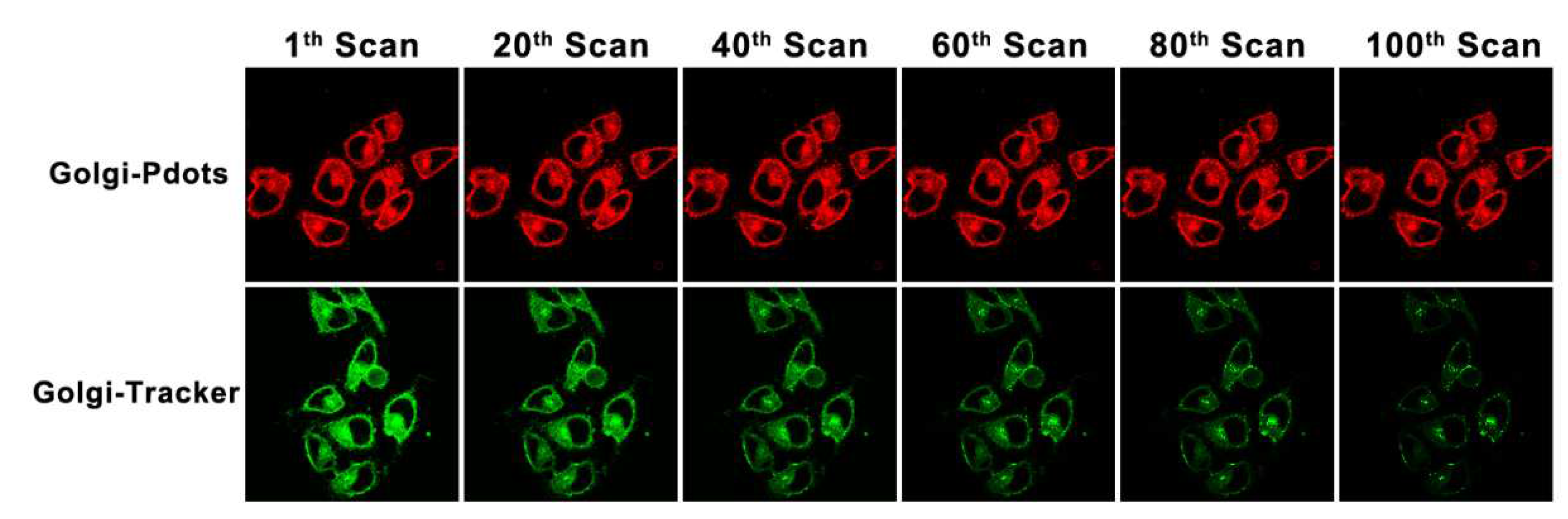

3.3. Cellular imaging

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Jiang, J.; Bi, G.; Zhang, G.; Li, G.; Chen, X. Highly selective and efficient synthesis of 7-aminoquinolines and their applications as Golgi-localized probes. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, H.; Cui, T.; Yao, S.; Jin, S.; Fan, H.; Wang, C.; Xie, R.; He, W.; Guo, Z. Golgi apparatus-targeted aggregation-induced emission luminogens for effective cancer photodynamic therapy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Su, M.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Rong, X.; Wang, K.; Li, X.; Zhu, B. Recent advances in Golgi-targeted small-molecule fluorescent probes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 462, 214504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, C.; Rong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Su, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Sheng, W.; Zhu, B. A new isothiocyanate-based Golgi-targeting fluorescent probe for Cys and its bioimaging applications during the Golgi stress response. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 122, 105741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, W.; Li, P.; Tang, B. Ratiometric fluorescence imaging of Golgi H2O2 reveals a correlation between Golgi oxidative stress and hypertension. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 10876–10880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Wei, Y.-Y.; Du, J.-L.; Yu, S.-P.; Liu, X.-G.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.-J.; Yang, Y.-Z.; Li, Q. Cyclooxygenase-2-targeting fluorescent carbon dots for the selective imaging of Golgi apparatus. Dyes Pigments 2022, 201, 110213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, Y.; Man, H.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xie, L.; Xiao, Y. A Golgi-targeted viscosity rotor for monitoring early alcohol-induced liver injury. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 10052–10055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Mao, S.; Sun, Y.; Sun, L.; Ding, N.; Li, C.; Zhou, J. A mitochondria-targeted near-infrared fluorescent probe for imaging viscosity in living cells and a diabetic mice model. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 4376–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Han, W.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, T.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Y.; He, Y.; Zhou, J. A lipid droplet-specific NIR fluorescent probe with a large stokes shift for in vivo visualization of polarity in contrast-induced acute kidney Injury. Anal. Chem. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Tian, Y. Recent advances in development of devices and probes for sensing and imaging in the brain. Sci. China Chem. 2021, 64, 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Q.; Cai, X.; Li, J.; LH, W.; Tao, C.; Yin, X.; Li, X.; Hou, S.; Jiang, D.; Liu, K.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Fan, C.; Tian, Y. Structural and functional imaging of brains. Sci. China Chem. 2023, 66, 324–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P.; Pan, W.; Li, N.; Tang, B. Fluorescent probes for organelle-targeted bioactive species imaging. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 6035–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Tian, Y. A ratiometric fluorescent probe for bioimaging and biosensing of HBrO in mitochondria upon oxidative stress. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 12198–12201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Ma, K.; Kang, M.; Huang, L.; Wu, Q.; Song, N.; Ge, J.; Li, D.; Dong, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, D.; Tang, B.Z. An aggregation-induced emission platform for efficient Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum specific imaging. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 13949–13957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, S.; Yoshikawa, M.; Tsutsui, K.; Miyazaki, T.; Kano, K.; Mishiro-Sato, E.; Tsukiji, S. Palmitoylation-dependent small-molecule fluorescent probes for live-cell Golgi imaging. ACS Chem. Biol. 2023, 18, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.-W.; Hong, S.T.; Kim, M.S.; Paik, K.C.; Han, M.S.; Cho, B.R. Two-photon probes for Golgi apparatus: Detection of Golgi apparatus in live tissue by two-photon microscopy, Anal. Chem. ( 2019. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, S.; Bhattacharya, A.; Hazra, N.; Gayen, K.; Sen, P.; Banerjee, A. Yellow-emitting carbon dots for selective fluorescence imaging of lipid droplets in living cells. Langmuir 2022, 38, 8829–8836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Liang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gao, W.; Liu, Z.; Tang, B. One-step fabrication of functional carbon dots with 90% fluorescence quantum yield for long-term lysosome imaging. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 6430–6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Cai, H.; Zhou, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Bi, H. RNA-targeting carbon dots for live-cell imaging of granule dynamics. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2210776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Liu, B.; Han, M.-Y.; Han, G.; Zhang, Z. One-step synthesized amphiphilic carbon dots for the super-resolution imaging of endoplasmic reticulum in live cells. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 19424–19430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhou, R.; Shan, C. Multicolor biomass based carbon nanodots for bacterial imaging. Chinese Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Dai, J.; Hu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhen, S.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Hu, J.J.; Lou, X.; Xia, F. Nanococktail based on AIEgens and semiconducting polymers: a single laser excited image-guided dual photothermal therapy. Theranostics 2020, 10, 2260–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Wu, J.; Jiang, M.; Sha, J.; Liu, W.; Ren, H.; Zhang, W.; Lee, C.-S.; Wang, P. A rhodamine derivative-based fluorescent probe for visual monitoring of pH changes in the Golgi apparatus. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 2022, 366, 131963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Ren, S.; Dang, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, K.; Long, X.; Jia, K. Coal-derived graphene quantum dots produced by ultrasonic physical tailoring and their capacity for Cu(II) detection. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 9793–9799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Cui, Y.; Liu, M.; Chen, J.; Wan, Q.; Wen, Y.; Deng, F.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y. A one-step ultrasonic irradiation assisted strategy for the preparation of polymer-functionalized carbon quantum dots and their biological imaging. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2018, 532, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Cui, K.; Gong, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhai, Z.; Hou, L.; Zaman, F.U.; Yuan, C. Ultrasonic-assisted synthesis of N-doped, multicolor carbon dots toward fluorescent inks, fluorescence sensors. and logic gate operations, Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.-B.; Liu, K.-K.; Song, S.-Y.; Zhou, R.; Shan, C.-X. Fluorescent nano-biomass dots: ultrasonic-assisted extraction and their application as nanoprobe for Fe3+ detection. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Gao, P.; Zhang, G.; Shi, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, J.; Shuang, S.; Zhang, Y. Rapid sonochemical synthesis of copper nanoclusters with red fluorescence for highly sensitive detection of silver ions. Microchem. J. 2022, 178, 107370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, S.; Chen, B.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Qiu, M.; Pan, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Endoplasmic reticulum-targeted polymer dots encapsulated with ultrasonic synthesized near-infrared carbon nanodots and their application for in vivo monitoring of Cu2+. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2022, 627, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedanken, A. Using sonochemistry for the fabrication of nanomaterials. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2004, 11, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, H.; Huang, L.-K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.-F.; Chen, S. Large-scale ultrasonic fabrication of white fluorescent carbon dots. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 5335–5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Geng, Y.; Li, D.; Yao, H.; Huo, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, S.; Wei, H.; Xu, W.; Jiang, J.; Yang, B. Deep red emissive carbonized polymer dots with unprecedented narrow full width at half maximum. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1906641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Kong, T.; Xiong, H.-M. Mulberry-leaves-derived red-emissive carbon dots for feeding silkworms to produce brightly fluorescent silk. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2200152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Liu, D.; Yang, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, S.; Yang, B. Self-enhanced carbonized polymer dots for selective visualization of lysosomes and real-time apoptosis monitoring. iScience 2020, 23, 100982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Song, H.; Tang, Z.; Yang, B.; Lu, S. Ethanol-derived white emissive carbon dots: the formation process investigation and multi-color/white LEDs preparation. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Shen, C.; Zhao, W.; Zheng, G.; Jiao, F.; Lou, Q.; Liu, K.; Shan, C.-X.; Dong, L. Biosynthesis of the narrowband deep-red emissive carbon nanodots from eggshells. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 6535–6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.-B.; Wang, R.-T.; Liu, K.-K.; Du, M.-R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Zhou, R.; Liang, Y.-C.; Ma, R.-N.; Sui, L.-Z.; Lou, Q.; Hou, L.; Shan, C.-X. Near-infrared carbon nanodots for effective identification and inactivation of Gram-positive bacteria. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Li, X. A yellow-emissive carbon nanodot-based ratiometric fluorescent nanosensor for visualization of exogenous and endogenous hydroxyl radicals in the mitochondria of live cells. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 3737–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.-B.; Chen, D.-D.; Liu, K.-K.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Song, S.-Y.; Li, F.-K.; Sui, L.-Z.; Lou, Q.; Hou, L.; Shan, C.-X. Near-infrared I/II emission and absorption carbon dots via constructing localized excited/charge transfer state for multiphoton imaging and photothermal therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.-W.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Y.-W.; Li, Y.-H.; Gao, G.; Zhu, Y.-X.; Lin, F.; Wu, F.-G. Rose bengal-derived ultrabright sulfur-doped carbon dots for fast discrimination between live and dead cells. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 4243–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wei, Z.; Sui, L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Feng, S.; Song, H.; Yong, X.; Tian, Y.; Yang, B.; Lu, S. Electron–phonon coupling-assisted universal red luminescence of o-phenylenediamine-based carbon dots. Light Sci. Appl. 2022, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, X.; Wei, C.; Gao, Y.; Han, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z. Long-lived phosphorescent carbon dots as photosensitizers for total antioxidant capacity assay. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 8914–8921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.-X.; Hu, L.; Wang, W.-J.; Kong, F.-Y.; Wei, M.-J.; Fang, H.-L.; Li, Q.-L.; Wang, W. One-pot green preparation of deep-ultraviolet and dual-emission carbon nanodots for dual-channel ratiometric determination of polyphenol in tea sample. Microchim. Acta 2022, 189, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.-K.; Song, S.-Y.; Sui, L.-Z.; Wu, S.-X.; Jing, P.-T.; Wang, R.-Q.; Li, Q.-Y.; Wu, G.-R.; Zhang, Z.-Z.; Yuan, K.-J.; Shan, C.-X. Efficient red/near-infrared-emissive carbon nanodots with multiphoton excited upconversion fluorescence. Adv. Sci. 2019, 0, 1900766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Huang, H.; Wang, T.; Zhou, D.; Chen, Q.; Li, D.; Chen, S.; Lin, P. Endoplasmic reticulum-targetable selenium-doped carbon nanodots with redox-responsive fluorescence for in situ free-radical scavenging in cells and mice. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 105036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, L.; Jia, J.; Eltayeb, O.; Lu, W.; Tang, Y.; Dong, C.; Shuang, S. Dual photoluminescence emission carbon dots for ratiometric fluorescent GSH sensing and cancer cell recognition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 18250–18257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, W.U.; Qin, L.; Alam, A.; Zhou, P.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Y. Water-soluble green-emitting carbon nanodots with enhanced thermal stability for biological applications. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 4301–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Jia, P.; Zhang, H.; Duan, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Qu, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, D.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; An, X.; Lu, S.; Zhang, S. Carbon dots as a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of cancer-related anemia. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2200905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Jia, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J. Dynamic anti-counterfeiting and reversible multi-level encryption-decryption based on spirulina derived pH-responsive dual-emissive carbon dots. J. Lumin. 2023, 257, 119727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, B. Polymer-encapsulated organic nanoparticles for fluorescence and photoacoustic imaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6570–6597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhu, D.; Xie, Z.; Li, G.; Zhang, P.; Su, Z.; Dou, C.; Tang, B.Z. Ultrafast and noninvasive long-term bioimaging with highly stable red aggregation-induced emission nanoparticles. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 3467–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Han, H.-H.; He, L.; Li, L.; Zang, Y.; Li, J.; He, X.-P.; Ding, Y.; Cao, W.; James, T.D. Selective detection of peroxynitrite using an isatin receptor and a naphthalimide fluorophore. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 5051–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Xia, X.; Huang, W.; Yan, D. Redox-responsive drug-inhibitor conjugate encapsulated in DSPE-PEG2k micelles for overcoming multidrug resistance to chemotherapy. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 4335–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-X.; Wang, Y.; An, H.-W.; Qi, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Shi, J.; Mei, L.; Wang, H. Peptide-based autophagic gene and cisplatin co-delivery systems enable improved chemotherapy resistance. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 2968–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).