Submitted:

25 July 2023

Posted:

26 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Qualitative Analyses of the 3 Sources of hMSC

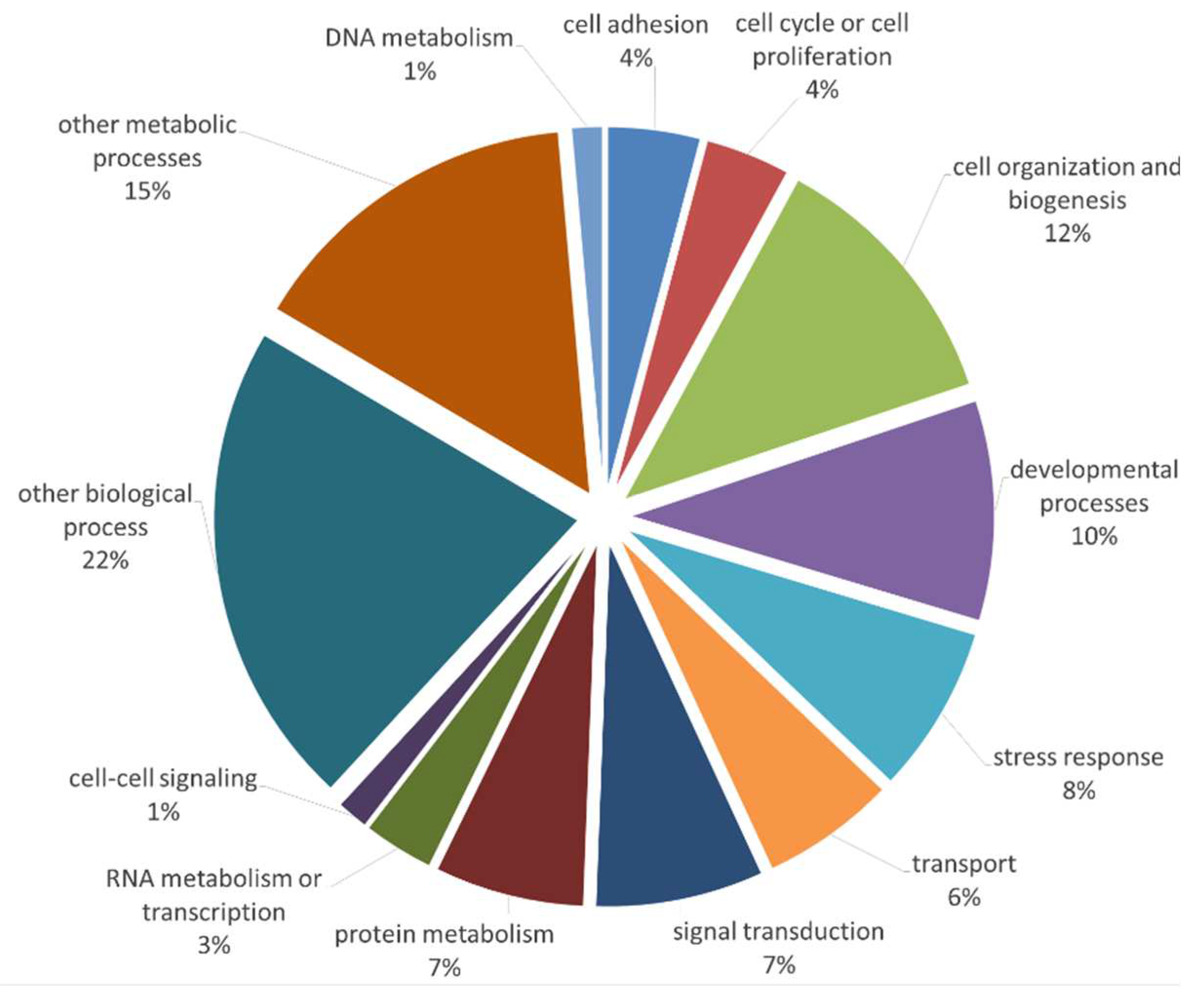

2.1.1. Differentially Expressed Proteins and Biological Processes Involved

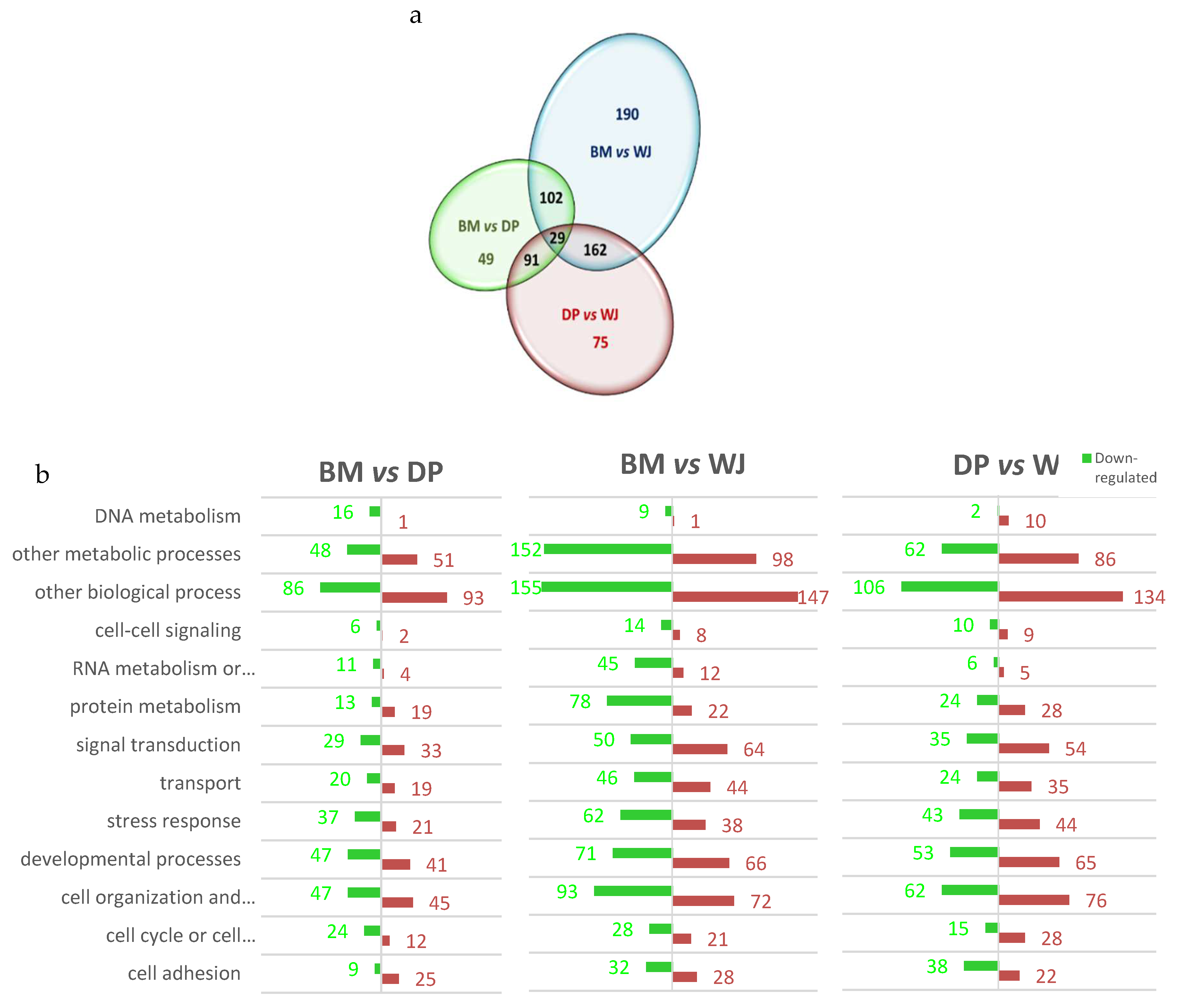

2.1.2. Group Comparison

2.2. Analyses Focused on the Functions of Interest of MSC in Cell Therapy

2.2.1. MSC Characteristics

- CD markers of MSC

- Differentiation capacities

2.2.2. ECM Production

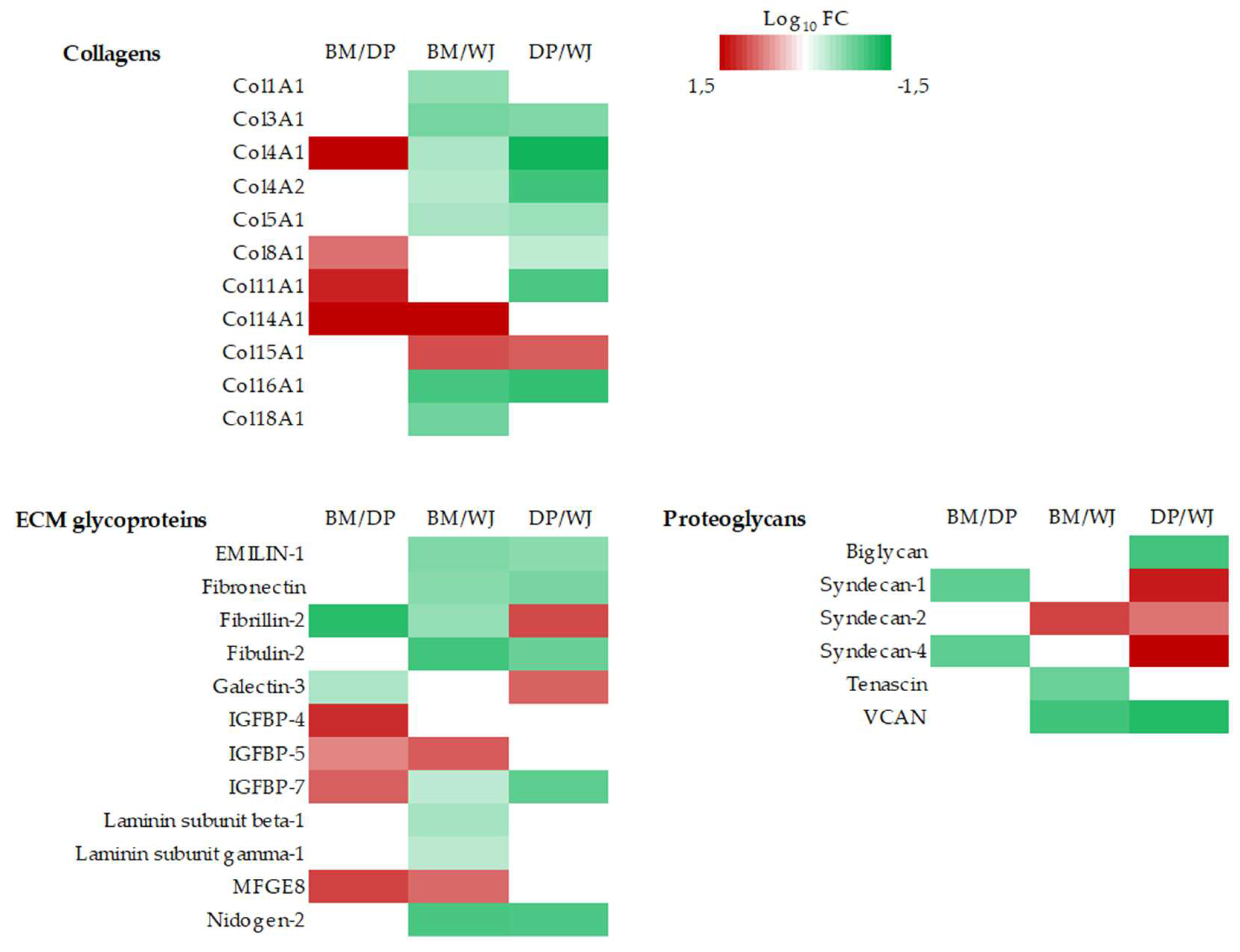

- collagens, ECM glycoproteins and proteoglycans

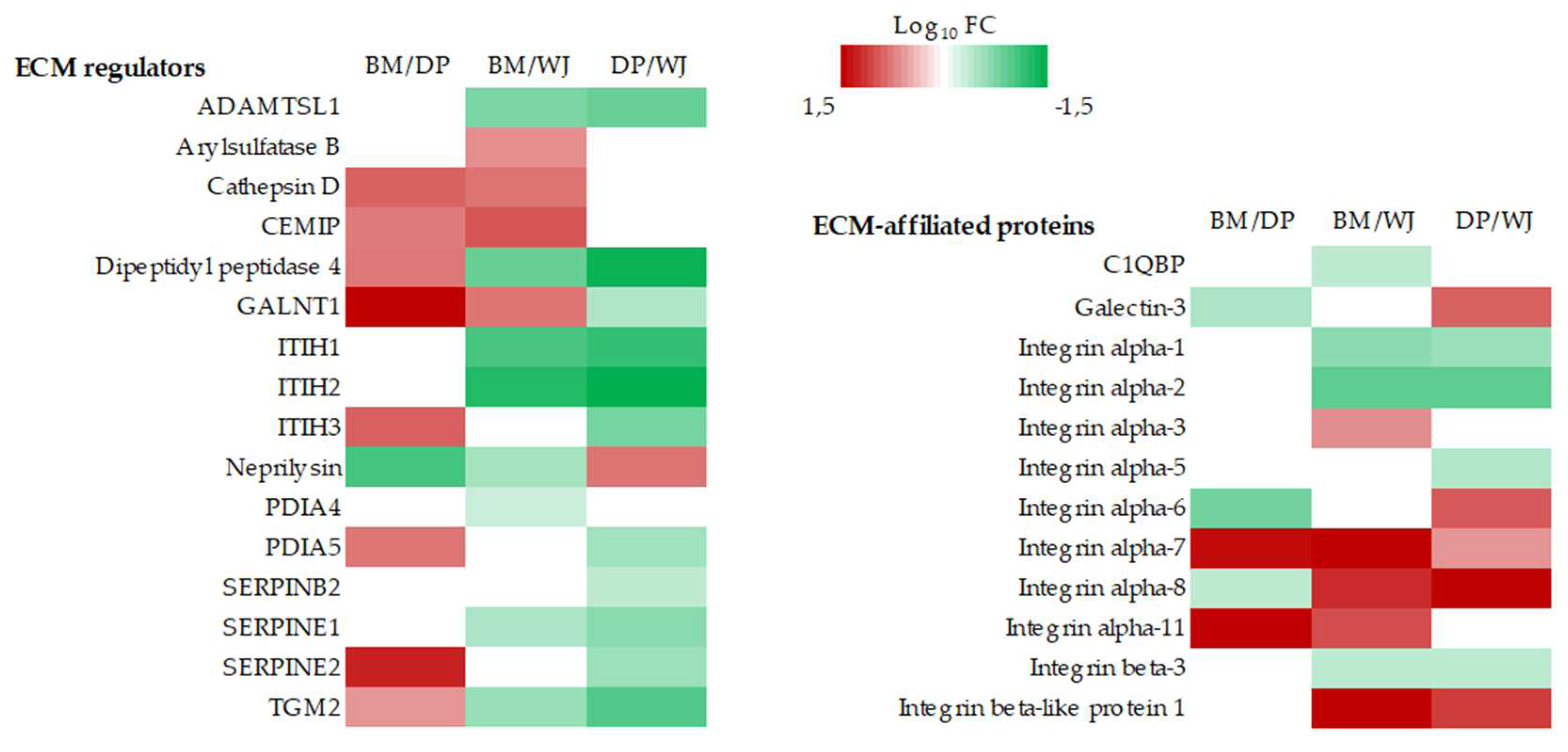

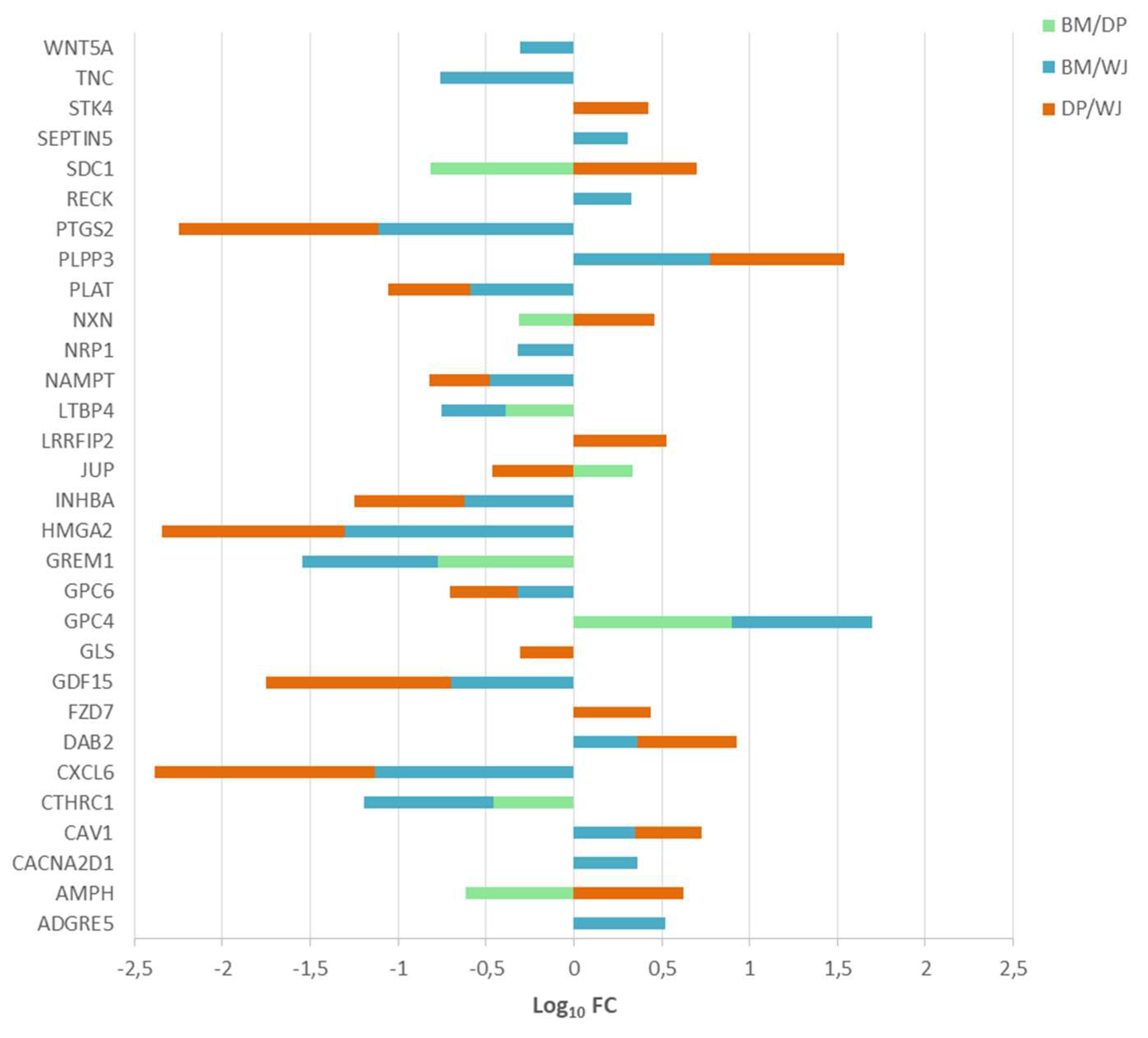

- ECM-associated proteins

2.2.3. Cell-Cell Signaling

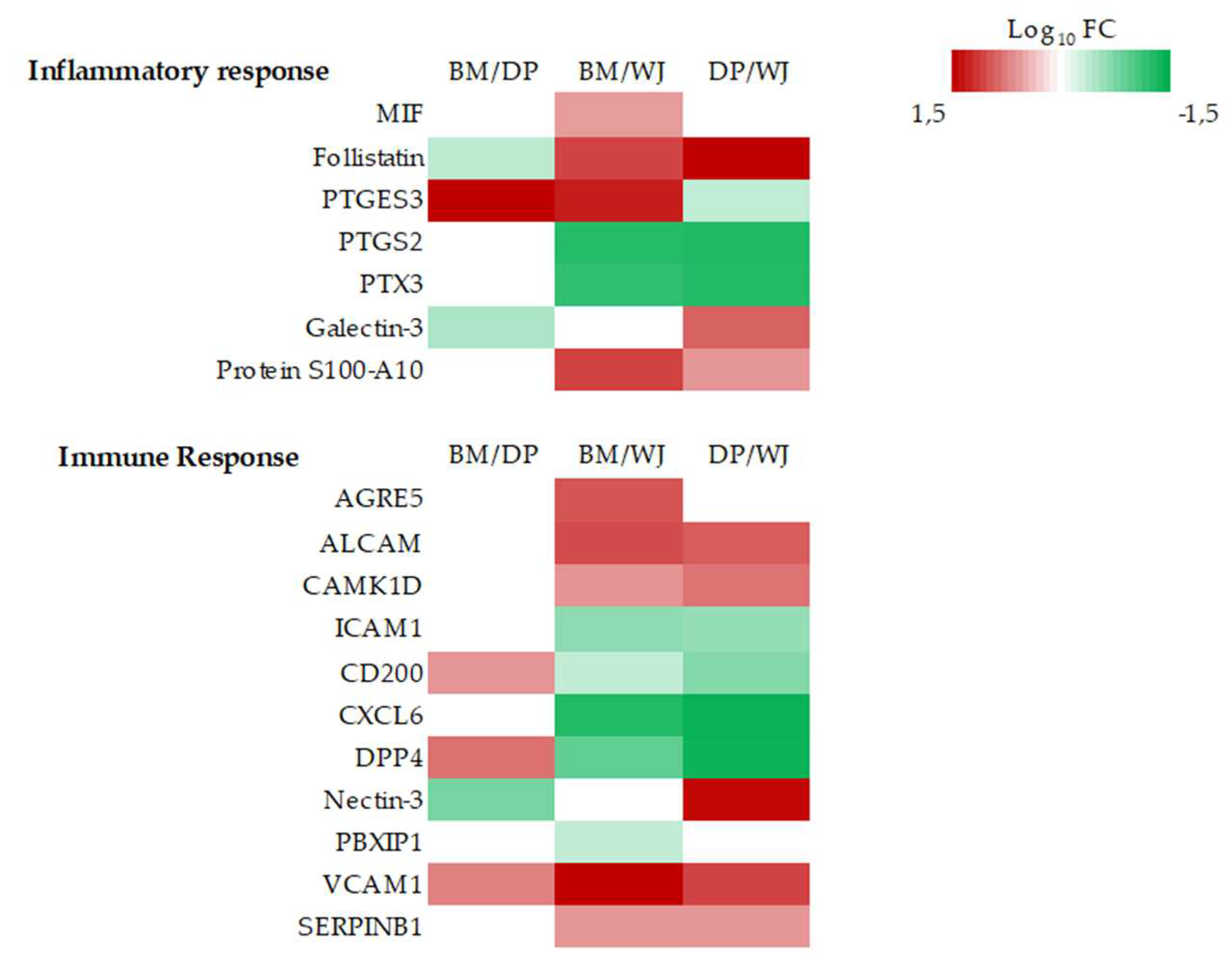

2.2.4. Inflammation and Immune Response

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedenstein, A.J.; Chailakhyan, R.K.; Gerasimov, U.V. Bone marrow osteogenic stem cells: In vitro cultivation and transplantation in diffusion chambers. Cell Prolif. 1987, 20, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, P. ; Robey; P. G., Simmons, P.J. Mesenchymal stem cells: revisiting history, concepts, and assays. Cell Stem Cell. 2008, 2, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.M.; Barry, F.P.; Murphy, J.M.; Mahon, B.P. , Mesenchymal stem cells avoid allogeneic rejection. J. of Inflammation 2005, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Chiu, S.M.; Motan, D.A.L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Ji, H.-L.; Tse, H.-F.; Fu, Q.-L.; Lian, Q. Mesenchymal stem cells and immunomodulation: current status and future prospects. Cell Death & Disease 2016, 7, e2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.Y.; Karunanithi, P.; Loo, W.C.; Naveen, S.; Chen, H.; Hussin, P.; Chan, L.; Kamarul, T. The effects of staged intra-articular injection of cultured autologous mesenchymal stromal cells on the repair of damaged cartilage: a pilot study in caprine model. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2013, 15, R129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruder, S.P.; Kurth, A.A.; Shea, M.; Hayes, W.C.; Jaiswal, N.; Kadiyala, S. Bone regeneration by implantation of purified, culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1998, 16, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah-Mohellibi, N.; Millet, G.; André-Schmutz, I.; Desforges, B.; Olaso, R.; Roblot, N.; Courageot, S.; Bensimon, G.; Cavazzana-Calvo, M.; Melki, J. Bone marrow transplantation attenuates the myopathic phenotype of a muscular mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Stem Cells. 2006, 12, 2723–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oryan, A.; Kamali, A.; Moshiri, A.; Eslaminejad, M.B. Role of mesenchymal stem cells in bone regenerative medicine: what is the evidence? Cells Tissues Organs 2017, 204, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decambron, A.; Fournet, A.; Bensidhoum, M.; Manassero, M.; Sailhan, F.; Petite, H.; Logeart-Avramoglou, D.; Viateau, V. Low-dose BMP-2 and MSC dual delivery onto coral scaffold for critical-size bone defect regeneration in sheep. J Orthop Res. 2017, 12, 2637–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, C.; Xue, D.; Yuan, W.; Wang, W.; Shen, D.; Tong, X.; Shi, D.; Liu, L.; Zheng, Q.; Gao, C.; Wang, J. Reconstruction of rat calvarial defects with human mesenchymal stem cells and osteoblast-like cells in poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid scaffolds. Eur Cell Mater. 2010, 20, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, M.; Liu, D.; Thakor, A.S. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Homing: Mechanisms and Strategies for Improvement. iScience 2019, 15, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan, M.; Yap, S.; Casteilla, L.; Chen, C.-W.; Corselli, M.; Park, T.S.; Andriolo, G.; Sun, B.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, L.; Norotte, C.; Teng, P.-N.; Traas, J.; Schugar, R.; Deasy, B.M.; Badylak, S.; Buhring, H.-J.; Giacobino, J.-P.; Lazzari, L.; Huard, J.; Péault, B. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008, 3, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronthos, S.; Mankani, M.; Brahim, J.; Gehron Robey, P.; Shi, S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000, 97, 13625–13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, B.-M.; Miura, M.; Gronthos, S.; Bartold, P.M.; Batouli, S.; Brahim, J.; Young, M.; Robey, P.G.; Wang, C.-Y.; Shi, S. Investigation of Multipotent Postnatal Stem Cells from Human Periodontal Ligament. Lancet 2004, 364, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riekstina, U.; Muceniece, R.; Cakstina, I.; Muiznieks, I.; Ancans, J. Characterization of human skin-derived mesenchymal stem cell proliferation rate in different growth conditions. Cytotechnology 2008, 58, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Qu, Z.; Yin, X.; Shang, C.; Ao, Q.; Gu, Y.; Liu, Y. Efficacy of umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy for osteonecrosis of the femoral head: A three-year follow-up study. Molecular Medecine Reports 2016, 14, 4209–4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.S.; Yen, H.H.; Chang, C.Y.; Lien, W.C.; Huang, S.H.; Lee, S.S.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.D. Adipose-Derived Stem Cell-Incubated HA-Rich Sponge Matrix Implant Modulates Oxidative Stress to Enhance VEGF and TGF-β Secretions for Extracellular Matrix Reconstruction In Vivo. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022, 9355692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Yin, Z.; Wu, T.; Li, Y.; Luo, X.; Xu, M.; Duan, L.; Li, J. Cell Transplantation 2018, 27, 1634–1643. [CrossRef]

- Suda, S.; Nito, C.; Ihara, M.; Iguchi, Y.; Urabe, T.; Matsumaru, Y.; Sakai, N.; Kimura, K. Randomised placebo-controlled multicentre trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of JTR-161, allogeneic human dental pulp stem cells, in patients with Acute Ischaemic stRoke (J-REPAIR). BMJ Open 2022, 12, e054269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, J.S.; Gopalakrishnan, D.; Shankar, S.R.R.; Vasandan, A.B. Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines, IFNc and TNFa, Influence Immune Properties of Human Bone Marrow and Wharton Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells Differentially. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, J.; Houben, A.P.; Radke, T.F.; Stapelkamp, D.; Bünemann, E.; Balan, P.; Buchheiser, A.; Liedtke, S.; Kögler, G. Distinct Differentiation Potential of ‘‘MSC’’ Derived from Cord Blood and Umbilical Cord: Are Cord-Derived Cells True Mesenchymal Stromal Cells? Stem Cells and Development 2012, 21, 1977–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raicevic, G.; Najar, M.; Pieters, K.; De Bruyn, C.; Meuleman, N.; Bron, D.; Toungouz, M.; Lagneaux, L. Inflammation and Toll-Like Receptor Ligation Differentially Affect the Osteogenic Potential of Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Depending on Their Tissue Origin. Tissue Eng Part A 2012, 18, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanko, P.; Kaiserovab, K.; Altanerovab, V.; Altanerb, C. Comparison of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from dental pulp, bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord tissue by gene expression. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014, 158, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivanović, D.; Jauković, A.; Popović, B.; Krstić, J.; Mojsilović, S.; Okić-Djordjević, I.; Kukolj, T.; Obradović, H.; Santibanez, J.F.; Bugarski, D. Mesenchymal stem cells of different origin: Comparative evaluation of proliferative capacity, telomere length and pluripotency marker expression. Life Sciences 2015, 141, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, A.O.; Mendes-Pinheiro, B.; Teixeira, F.G.; Anjo, S.I.; Ribeiro-Samy, S.; Gomes, E.D.; Serra, S.C.; Silva, N.A.; Manadas, B. , Sousa, N.; Salgado, A.J. Unveiling the Differences of Secretome of Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells, Adipose Tissue derived Stem Cells and Human Umbilical Cord Perivascular Cells: A Proteomic Analysis. Stem Cells Dev. 2016, 25, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.N.; Fong, C.Y.; Subramanian, A.; Liu, W. , Feng, Y.; Choolani, M.; Biswas, A.; Rajapakse, J.; Bongso, A. Human Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells Show Unique Gene Expression Compared to Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Using Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing. Stem Cells Dev. 2019, 28, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.G.; He, Z.Y.; Liang, S.; Yang, Q.; Cheng, P.; Chen, A.M. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of exosomes derived from human bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2020, 11, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Lee, J.; Kwon, Y.; Park, K.-S.; Jeong, J.-H.; Choi, S.-J.; Bang, S.I.; Chang, J.W.; Lee, C. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of the Mesenchymal Stem Cells Secretome from Adipose, Bone Marrow, Placenta and Wharton’s Jelly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, A.; Swaminathan, G.; Garcia-Marques, F.; Regmi, S.; Yarani, R.; Primavera, R.; Chetty, S.; Bermudez, A.; Pitteri, S.J.; Thakor, A.S. Integrated transcriptome-proteome analyses of human stem cells reveal source-dependent differences in their regenerative signature. Stem Cell Reports 2022, 18, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.C.; Krause, D.S.; Deans, R.J.; Keating, A.; DJ Prockop, D.J.; Horwitz, E.M. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, S.; Bernardo, M.E. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Role in the BM Niche and in the Support of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. HemaSphere 2018, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudot, M.; Barre, A.; Caula, A.; Sevestre, H.; Dakpé, S.; Mueller, A.A.; Devauchelle, B.; Testelin, S.; Marolleau, J.P.; Le Ricousse, S. Co-transplantation of Wharton's jelly mesenchymal stem cellderived osteoblasts with differentiated endothelial cells does not stimulate blood vessel and osteoid formation in nude mice models. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2020, 14, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.Y.; Fu, Y.S.; Chang, S.J.; Tsuang, Y.H.; Wang, H.W. Functional module analysis reveals differential osteogenic and stemness potentials in human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and Wharton’s Jelly of umbilical cord. Stem Cell and Development, 2010, 19, 1895–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, K.N.; Vennila, R.; Secunda, R.; Sakthivel, S.; Pathak, S.; Jeswanth, S.; Surendran, R. Functional variations between Mesenchymal Stem Cells of different tissue origins: A comparative gene expression profiling. Biotechnol Lett. 2020, 42, 1287–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, R.; Bogie, J.F.J.; Ravanidis, S.; Gervois, P.; Vanheusden, M.; Marée, R.; Schrynemackers, M.; Smeets, H.J.M.; Pinxteren, J.; Gijbels, K.; Walbers, S.; Mays, R.W.; Deans, R.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Stinissen, P.; Lambrichts, I.; Gyselaers, W.; Hellings, N. Human Wharton's Jelly-Derived Stem Cells Display a Distinct Immunomodulatory and Proregenerative Transcriptional Signature Compared to Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2018, 27, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouw, J.K.; Ou, G.; Weaver, V.M. Extracellular matrix assembly: a multiscale deconstruction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahimic, C.G.T.; Wang, Y.; Bikle, D.D. Anabolic effects of IGF-1signaling on the skeleton. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2013, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, J.; Furtak, V.; Lukyanov, P. Extracellular functions of galectin-3. Glycoconj J. 2002, 19, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.W. Review of signaling pathways governing MSC osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation. Scientifica 2013, 684736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shizas, N.P.; Zafeiris, C.; Neri, A.-A.; Anastasopoulos, P.P.; Papaioannou, N.A.; Dontas, I.A. Inhibition versus activation of canonical Wnt-signaling, to promote chondrogenic differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. A review. Orthopedic Reviews 2021, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, J.; Chen, Q.; Yan, H.; Du, H.; Luo, W. Regulation of pathophysiological and tissue regenerative functions of MSCs mediated via the WNT signaling pathway (Review). Molecular Medecine Reports 2021, 24, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, W.S.; Lai, R.C.; Zhang, B.; Lim, S.K. MSC exosome works through a protein-based mechanism of action. Biochemical Society Transactions 2018, 46, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Teo, K.Y.W.; Chuah, S.J.; Lai, R.C.; Lim, S.K.; Toh, W.S. MSC exosomes alleviate temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis by attenuating inflammation and restoring matrix homeostasis. Biomaterials 2019, 200, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z. MSC-Derived Exosomes-Based Therapy for Peripheral Nerve Injury: A Novel Therapeutic Strategy. BioMed Research International 2019, 6458237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Miguel, M.P.; Fuentes-Julián, S.; Blázquez-Martínez, A.; Pascual, C.Y.; Aller, M.A.; Arias, J.; Arnalich-Montiel, F. Immunosuppressive Properties of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Advances and Application. Current Molecular Medicine 2012, 12, 574–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konala, V.B.R.; Bhonde, R.; Pal, R. Secretome studies of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) isolated from three tissue sources reveal subtle differences in potency. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Animal 2020, 56, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The, M.; Maccoss, M.; Noble, W.; Käll, L. Fast and AccurateProtein False Discovery Rates on Large-Scale Proteomics Data Sets with Percolator 3.0. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2016, 27, 1719–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Csordas, A.; Bai, J.; Bernal-Llinares, M.; Hewapathirana, S.; Kundu, D. J.; Inuganti, A.; Griss, J.; Mayer, G.; Eisenacher, M.; Pérez, E.; Uszkoreit, J.; Pfeuffer, J.; Sachsenberg, T.; Yılmaz, ¸ S.; Tiwary, S.; Cox, J.; Audain, E.; Walzer, M.

- Jarnuczak, A.F.; Ternent, T.; Brazma, A.; Vizcaíno, J.A. The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: Improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D442–D450. [Google Scholar]

| Protein Name | Ratio | Most expressed by | Least expressed by | ||

| BM/DP | BM/WJ | DP/WJ | |||

| CD105: Endoglin | 2.842 | 2.542 | - | BM | |

| CD106: VCAM1 | 2.419 | 9.136 | 3.776 | BM | WJ |

| CD146: MCAM | 2.689 | 2.477 | - | BM | |

| CD166: ALCAM | - | 3.567 | 3.145 | WJ | |

| Protein Name | Gene Symbol | Ratio BM/DP | Ratio BM/WJ | Ration DP/WJ | Role of Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteoblast differentiations | |||||

| Alkaline phosphatase, tissue-nonspecific isozyme | ALPL | - | 5.508 | 4.441 | Promotes calcification |

| Transforming growth factor beta-1 proprotein | TGFB1 | - | - | 0.452 | TGF-β/BMP pathway controls the differentiation of mesenchymal precursor cells |

| Fibronectin | FN1 | - | - | 0.206 | Marker of osteoblast maturation |

| Adipocyte differentiations | |||||

| Prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 | PTGS2 | - | 0.077 | 0.073 | Suppressor of adipocytic differentiation |

| Adipogenesis regulatory factor | ADIRF | 3.25 | 5.483 | - | transcriptional regulator of white adipocyte differentiation |

| Neuronal differentiations | |||||

| Glia-derived nexin | SERPINE2 | 6.058 | - | 0.269 | Promotes neurite extension by inhibiting thrombin |

| Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2 | DPYSL2 | - | 2.706 | - | Involved in the regulation of axon formation during neuronal polarization as well as in axon growth and guidance |

| Echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 1 | EML1 | - | 2.598 | 4.279 | Required for normal proliferation of neuronal progenitor cells |

| Neuronal growth regulator 1 | NEGR1 | 2.263 | - | - | May function as a trans-neural growth-promoting factor in regenerative axon sprouting |

| Other differentiations | |||||

| Actin2, aortic smooth muscle | ACTA2 | 2.068 | - | - | Involved in vascular contractility and blood pressure homeostasis |

| Transgelin | TAGLN | 3.061 | 2.052 | - | Ubiquitously expressed in vascular and visceral smooth muscle and is an early marker of smooth muscle differentiation |

| Caldesmon | CALD1 | 2.139 | 2.48 | - | Regulated actomyosin interactions in smooth muscle and non-muscle cells Involved in Schwann cell migration during peripheral nerve regeneration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).