1. Introduction

Nitrogen is an indispensable element for the growth of green plants since it is involved in the synthesis of photosynthetic pigments, photosynthesis, yield, and quality. The administration of appropriate nitrogen can boost the synthesis of photosynthetic pigments, improving the efficiency of photosynthesis. This process can aid in the synthesis of organic compounds, which ultimately encourage the growth and development of plants [

1,

2,

3]. Plants with low nitrogen levels restrict the production of photosynthetic pigments, resulting in yellowing of leaves and stunted growth [

4,

5]. Excessive nitrogen inhibits the absorption of other essential elements, such as potassium and magnesium, leading to a deficiency in these elements [

4,

5]. This shortage, in turn, has an impact on physiological function. Furthermore, it reduces the quality of flowers and fruits and the ability to resist pests and diseases. The growth and development of plants can be affected by varying levels of nitrogen. Notably, there is a positive correlation between the content of photosynthetic pigment concentration and nitrogen status. The determination of pigment content in leaves can serve as an indirect indicator of nitrogen diagnosis. Nitrogen is readily transported inside plants, leading to variations in pigment content across different leaf locations [

6]. Regarding the inspection of the pigment aspect, the traditional laboratory chemical analysis remains the predominant method. Although this approach produces accurate and intuitive results, it is also time-consuming, destructive, and environmentally unfriendly. Obtaining accurate results for large samples promptly is even more challenging. This hysteresis not only has an impact on agricultural production but also makes it difficult for agricultural managers to make scientifically sound decisions. Visible-near infrared (VNIR) spectroscopy is a rapid, efficient, and non-destructive inspection method that has been used to obtain differences in pigment concentration in plant leaves [

7]. As a result, spectrum analysis has become a prominent research topic for scholars both domestically and abroad in recent years.

The visible-near infrared hyperspectral imager (VNIR-HSI) is a non-contact technology that integrates spectrum and images, making it a powerful tool for environmental monitoring, agricultural production, medical diagnosis, and other fields [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. VNIR-HSI technology provides an effective means for quantitative and qualitative analysis of crop growth monitoring, quality detection, and nutritional diagnosis in agricultural production. Producers can accurately evaluate the growth state, quality features, and nutrient level using reflectance spectrum analysis, enabling them to perform precision management of the environment and fertilization. The fundamental components of photosynthesis in green plants are photosynthetic pigments, primarily chlorophyll (Chll) and carotenoid (Caro). These molecules can absorb light energy and convert it into chemical energy to promote the process of photosynthesis. Chll, comprising mainly chlorophyll a (Chla) and chlorophyll b (Chlb), is the main light-capturing molecule that absorbs light energy and transfers it to the reaction center to catalyze the process [

13]. Meanwhile, Caro plays a supporting part. Different photosynthetic pigments in leaves collaborate to regulate photosynthesis to achieve the best photosynthetic efficiency and growth condition. Thus, leaf pigment concentration is directly tied to the photosynthetic rate and directly impacts plant growth and development. VNIR-HSI is performed on plant leaves to determine the spatial distribution and spectrum features. The accuracy and quality of the data are improved through various processing techniques such as denoising, calibration, dimensioning, and so on [

14,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Vahtmäe et al. [

15] established a prediction model for the concentrations of Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro in various Baltic Sea Macroalgae, demonstrating that VNIR-HSI technology may be effectively applied to the detection of photosynthetic pigment. Wang et al. [

16] took Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro in tea under various nitrogen treatment levels as the research indicates. Combined with VNIR-HSI technology and feature selection algorithm to construct prediction models, the correlation coefficients of each pigment prediction were greater than 0.9. It demonstrates that VNIR-HSI can be applied to the rapid and accurate prediction of pigment content. Che et al. [

17] analyzed the phenotypes of photosynthetic pigments in

Neopyropia yezoensis for phycoerythrin (PE), phycocyanin (PC), allophycocyanin (APC), and Chla using VNIR-HSI. Two machine learning techniques, partial least squares regression (PLSR) and support vector machine regression (SVR), were employed in the prediction model after several pre-processing approaches. However, there has been no research on the spatial composition and distribution of photosynthetic pigments in crops.

This work aimed to use VNIR-HSI technology to simultaneously detect and visualize the distribution of pigment content in

Lycopersicon esculentum Mill leaves. More specifically, the research objects were the leaves of

Lycopersicon esculentum Mill seedlings cultivated in nutritional solutions with variable nitrogen concentrations at various leaf locations. The content of Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro were used as research indexes. The chemical constituents of the leaves were determined by traditional laboratory methods, and the spectrum and image were obtained by VNIR-HSI. The batch extraction and processing software was compiled for selecting regions of interest (ROI). A "coarse-fine" characteristic variable screening strategy was adopted for the pre-treated spectral data to establish quantitative models that could simultaneously predict multiple pigments. Finally, these models were applied to the image to visualize the pigment content and distribution.

Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of this work. The significance of this study is to, on the one hand, use hyperspectral imaging technology combined with a machine learning algorithm to construct pigment prediction models and carry out visual expression. On the other hand, the optimum nitrogen concentration of

Lycopersicon esculentum Mill nutrient solution in facility agriculture has been explored to provide a scientific basis for precise fertilizer management in facility agriculture.

Figure 1.

The schematic diagram of this work.

Figure 1.

The schematic diagram of this work.

2. Results

2.1. Statistical analysis of measured pigments content of leaf position

Different nitrogen concentrations in the nutrient solution caused significant differences in pigment content of leaf position for

Lycopersicon esculentum Mill, as shown in

Figure 2. The maximum growth rate with increasing concentration was 7.32%, 11.56%, 7.70%, and 10.44% for Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro, respectively, at nitrogen concentrations below N100 (302.84 mg/L). When the nitrogen concentration was greater than N100, the maximum rate of decline with increasing concentration reached 11.32%, 12.46%, 11.63%, and 8.56%, respectively. As a result, the maximum amount of leaf pigment and the optimal nitrogen concentration for

Lycopersicon esculentum Mill seedlings was 302.84 mg/L in the nutrient solution. Meanwhile, the inhibitory effect of high concentration was stronger than that of low concentration. Since nitrogen is readily translocated in the plant organism. The content reduction rates from Upper to Middle for Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro were 11.48%, 15.13%, 7.55%, and 18.22%, respectively. The reduction rates from Middle to Lower were 15.47%, 12.41%, 14.13%, and 22.52%, respectively. Therefore, the distribution pattern of leaf pigment content was Upper > Middle > Lower. This conclusion is the absorption of nutrient elements by photosynthesis of crops.

Figure 2.

Effect of nitrogen concentration on pigment content in Lycopersicon esculentum Mill leaves.

Figure 2.

Effect of nitrogen concentration on pigment content in Lycopersicon esculentum Mill leaves.

2.2. Sample partition and data preprocessing

This work aimed to construct simultaneous quantification models for Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro. In model development, calibration is required to construct the model and perform cross-validation, while prediction is used to evaluate the predictive performance of the model. All samples (N = 435) were divided into two datasets by the SPXY algorithm [

18,

19], which partitions sample sets based on joint x-y distance. Among them, 326 samples (accounting for 75% of the total) and 109 samples (accounting for 25% of the total) constitute the calibration and prediction datasets, respectively. Different spectral pretreatment methods were adopted for different pigment indicators. For different pigment markers, various pretreatment techniques were used. No-pretreatment and pretreatment spectral variables were predicted using PLS [

20,

21], and the results are shown in

Table S1. The S-G+SNV pretreatment with R

p2 = 0.8064, RMSE

p = 1.49, and RPD = 2.27 produced the best results for Chla. The S-G pretreatment with R

p2 = 0.8286, RMSE

p = 0.54, and RPD = 2.42 produced the best results for Chlb. The SNV pretreatment with R

p2 = 0.7776, RMSE

p = 2.29, and RPD = 2.12 produced the best results for Chll. The SNV pretreatment with R

p2 = 0.7294, RMSE

p = 0.29, and RPD = 1.92 produced the best results for Caro.

Table 1 displays the statistical reference values for various pigment indicators in leaves using the best pretreatment strategy. The similarity between the sample mean of the calibration and prediction indicates the rationality of dataset partitioning.

Table 1.

Statistics of pigments content in leaves.

Table 1.

Statistics of pigments content in leaves.

| Pigments |

Subsets |

NSa

|

Range (mg/L) |

Mean (mg/L) |

SDb (mg/L) |

| Chla |

Calibration set |

326 |

3.37-21.13 |

9.22 |

3.05 |

| Prediction set |

109 |

5.56-20.14 |

9.61 |

2.52 |

| Chlb |

Calibration set |

326 |

1.22-8.49 |

3.29 |

1.23 |

| Prediction set |

109 |

1.80-7.89 |

3.45 |

1.04 |

| Chll |

Calibration set |

326 |

4.61-29.62 |

12.44 |

4.19 |

| Prediction set |

109 |

7.52-28.02 |

13.26 |

5.07 |

| Caro |

Calibration set |

326 |

0.6-3.23 |

1.48 |

0.48 |

| Prediction set |

109 |

0.9-2.8 |

1.50 |

0.42 |

2.3. Results of CARS-PLS modeling

The purpose of the CARS algorithm is to eliminate irrelevant variables and reduce collinearity between variables.

Figures S1–S4 describes the changes in the number of sample variables (NSV), root mean square error of cross-validation (RMSE

cv), and regression coefficient path (RCs) in the subset as the number of MCS runs increases. As the number of MCS runs increased, the filtered variables declined exponentially at first, then gradually leveled off. The RMSE

cv showed a trend of decreasing and then increasing. It indicated that the variables that were removed at the beginning of the variable screening process were not correlated with the components to be measured. Subsequently, unrelated variables were added to the subset of variables. More effective wavelengths have been retained in the RCs annotation. At this time, the RMSE

cv reached the minimum value, and the selected variables were the optimal variable set, . For Chla, the RMSE

cv was minimum when the sampling frequency was 64. The prediction model was created with 16 variables in the subset (R

p2 = 0.8168, RMSE

p = 1.45, RPD = 2.34), as shown in

Figure S1,

Table S3 and

Table 2. For Chlb, when the sampling frequency was 64, the RMSE

cv was minimum. The prediction model was created with 16 variables in the subset (R

p2 = 0.8302, RMSE

p = 0.54, RPD = 2.43), as shown in

Figure S2,

Table S3 and

Table 2. For Chll, when the sampling frequency was 61, the RMSE

cv was minimum. The prediction model was created with 19 variables in the subset (R

p2 = 0.7869, RMSE

p = 2.25, RPD = 2.17), as shown in

Figure S3,

Table S3 and

Table 2. For Caro, when the sampling frequency was 62, the RMSE

cv was minimum. The prediction model was created with 18 variables in the subset (R

p2 = 0.7532, RMSE

p = 0.28, RPD = 2.01), as shown in

Figure S4,

Table S3 and

Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of prediction models for different pigments.

Table 2.

Results of prediction models for different pigments.

| Pigments |

Models |

Calibration set |

|

Prediction set |

RPD |

| Rc2

|

RMSEc

|

|

Rp2

|

RMSEp

|

| Chla |

PLS |

0.7877 |

1.88 |

|

0.8064 |

1.49 |

2.27 |

| CARS-PLS |

0.8040 |

1.81 |

|

0.8168 |

1.45 |

2.34 |

| CARS-IRIV-PLS |

0.8045 |

1.81 |

|

0.8240 |

1.43 |

2.38 |

| Chlb |

PLS |

0.7790 |

0.79 |

|

0.8286 |

0.54 |

2.42 |

| CARS-PLS |

0.7899 |

0.77 |

|

0.8302 |

0.54 |

2.43 |

| CARS-IRIV-PLS |

0.7953 |

0.74 |

|

0.8391 |

0.53 |

2.49 |

| Chll |

PLS |

0.7964 |

2.53 |

|

0.7776 |

2.25 |

2.12 |

| CARS-PLS |

0.8185 |

2.41 |

|

0.7869 |

2.25 |

2.17 |

| CARS-IRIV-PLS |

0.8190 |

2.40 |

|

0.7899 |

2.24 |

2.18 |

| Caro |

PLS |

0.6768 |

0.35 |

|

0.7294 |

0.29 |

1.92 |

| CARS-PLS |

0.7170 |

0.33 |

|

0.7532 |

0.28 |

2.01 |

| CARS-IRIV-PLS |

0.7191 |

0.33 |

|

0.7577 |

0.27 |

2.03 |

2.4. Results of CARS-IRIV-PLS modeling

Considering the existence of adjacent variables in the characteristic variables screened by CARS, there may be redundant variables present. The IRIV algorithm establishes a series of sub-models based on a randomly generated subset of sample variables. Variables that appear more frequently in the sub-models have higher weights and are retained during multiple iterations. However, this algorithm requires multiple iterations, resulting in a relatively large computational workload. Given this, this work combines CARS and IRIV algorithms to "exploit strengths and avoid weaknesses". The IRIV algorithm was used to screen the characteristic variables of the CARS algorithm. Furthermore, the variables selected by the CARS algorithm were determined to be strong informative variables, weak informative variables, uninformative variables, and interfering variables.

Table S2 describes the classification of variables screened by the CARS algorithm using the IRIV algorithm. The results showed that only strong and weak variables existed in the variables selected by the CARS algorithm after judging by the IRIV algorithm. The optimal combination of variables was obtained by cross-validating the inverse elimination of the combination of strong and weak information variables by the IRIV algorithm, as shown in

Table S3.

Table 2 describes the results of prediction models for Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro. For Chla, the prediction model was created to achieve the optimal effect with 12 variables by the CARS-IRIV algorithm (R

p2 = 0.8240, RMSE

p = 1.43, RPD = 2.38). For Chlb, the prediction model was created to achieve the optimal effect with 10 variables (R

p2 = 0.8391, RMSE

p = 0.53, RPD = 2.49). For Chll, the prediction model was created to achieve the optimal effect with 10 variables (R

p2 = 0.7899, RMSE

p = 2.24, RPD = 2.18). For Caro, the prediction model was created to achieve the optimal effect with 11 variables (R

p2 = 0.7577, RMSE

p = 0.27, RPD = 2.03).

2.5. Visualized distribution of leaf pigments

The image information of the leaf position of

Lycopersicon esculentum Mill seedling under different nitrogen concentrations was collected using hyperspectral imaging system. The leaves from the N60, N100, and N140 cultivation were selected and their contour was extracted using ENVI software. The characteristic wavelengths were superimposed to calculate the pigment content value of each pixel to generate the leaf gray level map using the optimal prediction model of Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro. The leaf image was inverted and color rendering was applied to the pixels in accordance with the content value and pseudo-color map to produce a visualization that shows the distribution of pigment.

Figure 3 describe the distribution and content of pigments at different leaf locations of N60, N100 and N140 nitrogen concentrations, respectively. The pigment concentration ranged from 0 to 30 mg/L. The numerical annotation represents the corresponding leaf pigment content. The results showed that the maximum content of each pigment in the leaves was reached under the N100 concentration treatment, and the pigment content was higher under the N60 concentration treatment than N140. This result further indicates that N100 was the optimum nitrogen concentration for

Lycopersicon esculentum Mill seedlings, while the inhibitory effect was stronger at higher concentrations than at lower ones. The pigment content of leaves showed a pattern of Chll > Chla > Chlb > Caro. The pigment content between leaf locations showed a distribution of Upper > Middle > Lower. It is caused by the absorption of nutrients during the photosynthesis of the crop. The results are in agreement with the chemical measurement. Thus, visualization analysis can clearly elucidate the distribution and content of pigments in different leaf positions at different nutrient nitrogen concentrations.

Figure 3.

Visualization of pigment content and distribution pattern of leaf position under cultivation with different nitrogen concentration. (a) Visualization of leaf pigments under N60 cultivation; (b) Visualization of leaf pigments under N100 cultivation; (c) Visualization of leaf pigments under N140 cultivation. (blue represents the minimum value, and red represents the maximum value).

Figure 3.

Visualization of pigment content and distribution pattern of leaf position under cultivation with different nitrogen concentration. (a) Visualization of leaf pigments under N60 cultivation; (b) Visualization of leaf pigments under N100 cultivation; (c) Visualization of leaf pigments under N140 cultivation. (blue represents the minimum value, and red represents the maximum value).

3. Discussion

The CARS algorithm adopts EDF to remove the wave points with small regression coefficients, which can enhance the characteristic extraction process. The characteristic wavelengths for Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro accounted for 2.48% (16/646), 2.48% (16/646), 2.94% (19/646), and 2.79% (18/646) of the full spectrum, respectively. However, there were adjacent wavelengths present in the optimal combination of variables for each pigment correlation. The IRIV algorithm uses Mann-Whitney U-test to discriminate the degree of correlation of variables, and the optimal variable set for each pigment has no uninformative or interfering variables. This indicates that the CARS algorithm has certain advantages in characteristic variable extraction. The optimal combination of variables was obtained by inverse elimination of the set of variables. Finally, the characteristic wavelengths were extracted for Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro accounting for 1.86% (12/646), 1.55% (10/646), 1.86% (12/646), and 1.70% (11/646) of the full spectrum, respectively. The characteristic variables extracted were reduced by 0.62%, 0.93%, 1.08%, and 1.09%, respectively, compared to those extracted by the CARS algorithm. It is also shown that weak information variables play an important role in the combination, which can effectively improve the predictive performance of the model. From

Table 2, it can be concluded that the prediction effect was CARS-IRIV-PLS > CARS-PLS > PLS. This demonstrates the reliability of the "coarse-fine" characteristic extraction strategy of CARS-IRIV proposed in this study. This also reflects the enormous potential of VNIR-HSI technology combined with the CARS-IRIV-PLS model in the synchronous quantitative detection of pigments.

Figure 4 depicts the distribution of characteristic variables extracted from pigments using CARS and CARS-IRIV algorithms. The characteristic wavelengths of Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro were mainly concentrated at 435-510 nm, 660-760 nm, and 800-895 nm. And all have 691 nm, 702 nm, 715 nm, 730 nm, and 760 nm selected. In the visible spectral region, Chla, Chlb, and Chll mainly absorb blue, purple, and red light, with two strong absorption regions at 400-460 nm and 630-680 nm [

5,

8,

22,

23]. Caro mainly absorbs blue, and purple light, which is a strong absorption region at 400-500 nm [

5,

10,

24,

25]. In the near-infrared spectral region, it is mainly caused by the absorption of water or oxygen. Notably, Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro have overlapping bands selected. The visible region is due to the action of the chromogenic group (C=O, C=C, C≡C) and chromatic group (-OH) [

26,

27,

28,

29]. In the near-infrared region, it was mainly affected by the O-H bond and O

2 inside the blade, the double frequency and triple frequency, and the combination frequency of the stretching vibration of the C-H group [

30].

Figure 4.

Extraction results of spectral variables for the Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro in Lycopersicon esculentum Mill leaves.

Figure 4.

Extraction results of spectral variables for the Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro in Lycopersicon esculentum Mill leaves.

Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro are the main photosynthetic pigments in plants. According to

Figure 3, the content and distribution of pigment in the leaves could be obtained. Chla decreased gradually from the bottom of the leaf to the top and from the vein to the edge of the leaf. This is caused that Chla is mainly present in the chloroplast thylakoid membrane, while the nutrients are transported to the leaves through the leaf veins [

16,

31]. Therefore, Chla content was higher in the bottom and vein parts of the leaves. In contrast, the top and leaf edge parts of the leaves had a relatively low nutrient supply, resulting in relatively low Chla content. Chlb is mainly distributed in the photosynthetic membrane of chloroplasts [

32]. The distribution in the leaves is heterogeneous, with higher levels around the leaves and in the veins, and lower levels in the center. Chll is mainly composed of Chla and Chlb. It is mainly distributed in chloroplasts, but also the other cytoplasm of leaves. The content of Chlb is much lower than that of Chla, accounting for only 10-15% of the Chll [

33], resulting in a distribution pattern of Chll that is roughly consistent with that of Chla. Caro is mainly distributed in the epidermis and subepidermis cells of leaves.

Lycopersicon esculentum Mill seedling is in the flourishing stage of development, photosynthesis promotes the active and high content of Chll in leaves. In this process, Caro protects the leaves from UV and free radical damage. Therefore, it is present in high levels in the epidermal and subepidermal cells of the leaves. However, Caro mainly acts on leaf color and their content is low, resulting in Caro being covered by Chll. It is similar to the distribution of Chlb in leaves. The differences in the distribution of pigments in leaf locations are due to differences in nutrient transport and light exposure, which are consistent with the physiological characteristics of green plants.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental design and sample collection

The experiment was carried out in the scientific greenhouse of the College of Agricultural Engineering, Shanxi Agricultural University (37°25' N, 112°34' E) from November 12, 2021, to December 13, 2021, and September 25, 2022, to October 18, 2022, respectively. The seedling of

Lycopersicum esculentum Mill.

cv. Provence with "4 leaves and 1 core" was purchased from the nursery company. A total of 145 plants were transplanted into a nutritive bowl with coconut bran as substrate. The nutrient solution adopted the

Lycopersicum esculentum Mill formula self-prepared water-soluble fertilizer of the Holland Greenhouse Horticulture Research Institute, with 10 nitrogen gradients (denote as N20, N40, N60, N80, N100, N120, N140, N160, N180, N200). Ca

2+ was supplemented with calcium fertilizer (Ca

2+ ≥ 94%, Green-Micro Power Crop Nutrition Co., UK) to keep the concentration constant. Nitrogen concentration was regulated using urea, and

Table S4 shows its precise addition, EC, and pH. The leaves were sampled at the "transplant-bloom" (seedling) stage. At this time, 10-11 branches extended from the main stem. As shown in

Figure 1A, arranged the leaves in descending order. Wherein, the 9-7 branch blades were classified as the upper leaf location (Upper), the 6-4 branch blades were the middle leaf location (Middle), and the 3-1 branch blades were the lower leaf location (Lower).

Lycopersicum esculentum Mill is a "single-branch and leafiness" plant. Therefore, sample collection on each branch is referred to in

Figure 1B. The leaves with uniform size and spreading were picked based on the sampling rule, with 6 leaves (1 sample) chosen from each leaf location for a total of 2610 leaves (435 samples). The samples were stored in sealed bags with sequential numbers and kept in a dry ice-filled incubator.

4.2. Hyperspectral image acquisition

Leaf images were collected using the VNIR-HSI (Headwall Photonics, Starter Kit, USA) scanning platform. This system captures 856 spectral bands from 380 to 1000 nm with a spectral resolution of approximately 0.727 nm. A spectral range with a total of 646 bands, ranging from 430 to 900 nm, is chosen due to the significant reflectivity error near the measuring range. The movement speed, push-broom stroke, and distance between the lens and leaf for the system were set to 2.721 mm/s, 100 mm, and 28 cm, respectively, to obtain clear and undistorted images. First, wash the dust and impurities off the leaf surface with deionized water. Second, blot the surface moisture with filter paper. Finally, the leaves were laid flat on the stage to obtain hyperspectral images. To reduce the image interference generated by the system light source and dark current, the hyperspectral image is corrected for black and white according to the following equation.

Where, R is the corrected hyperspectral image; R0 is the original hyperspectral image; Rw is the white background image with the standard white calibration plate (> 99.9% reflectance); Rb is the dark background image with the lens cap closed (< 0% reflectance).

4.3. Chemical measurement of pigment content

After collecting spectral images from the samples, the content of Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro was measured using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Jingke Shangfen, Shanghai, China). After removing the veins, each sample was sliced into pieces of about 2*2 mm, mixed evenly, weighed 0.2 g, and deposited in a test tube. It was extracted with 96% ethyl alcohol in the darkness for 24 h until the pieces turned white. The absorbance of the prepared pigment extracts was measured at wavelengths of 665, 649, and 470 nm, respectively [

28]. Each sample was repeated 3 times, and the pigment content was calculated according to the following formula.

4.4. Selection of ROI

On the one hand, there are veins of different sizes distributed in the leaves, especially the largest midrib in the center. VNIR-HIS, on the other hand, has a high resolution and lots of pixels. Choosing the ROI for the leaves was challenging due to these factors. SpectralView software (Headwall Photonics, USA) was used for secondary development with Visual Basic (Version 6.0, Microsoft, USA), which produced software for batch extraction and processing of hyperspectral data. The core module of the program was made up of a pixel-generating module and a batch-processing module. The elliptical model was used to determine the coordinates of the center of ROI, the length of the X/Y semi-axis (a, b), and the distance between the X/Y axes (Δx, Δy were both set to 1). Followed the principle of "from left to right, from top to bottom" in the target image to sequentially collect the pixels in the ROI according to formula (6), and generated the ROI coordinate matrix. SpectralView software was used to import images and actively extract the reflectivity information based on the coordinate matrix. Depending on the requirements, the batch processing module could produce numerical calculation results such as mean, mean difference, and variance. The leaf is mostly made up of the leaf tip, leaf base, leaf margin, and other components. To extract as many of these parts as possible. Therefore, the leaf was divided into three areas to extract a total of 32,000 pixels, as shown in

Figure 1 ROI selection, that is, each sample extracted 192,000 (32,000 × 6) pixels. The sample average spectral (according to formula (7)) was adopted as the basic dataset for subsequent processing.

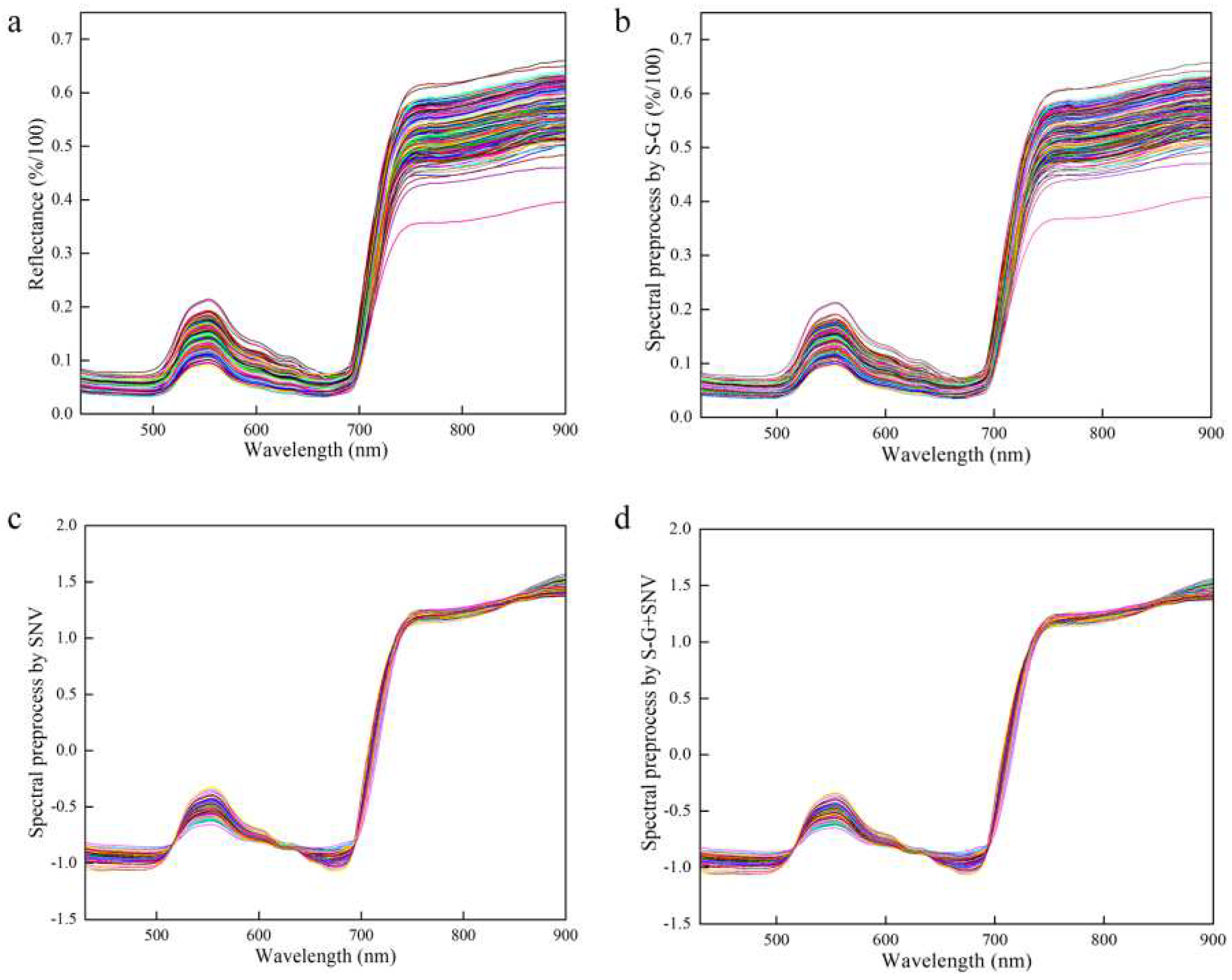

4.5. Spectrum pretreatment and model calibration

Spectrum stability is always influenced by leaf gloss, leaf reflection, background interference, and baseline drift during the scanning process. Therefore, the effective spectrum was preprocessed using the Sacitzky-Golay smoothing filter (S-G) [

34,

35], standard normal variable (SNV) [

36], and S-G+SNV [

37] approaches, which reduced interference before modeling and effectively improved the prediction accuracy of the model, as shown in

Figure 5.

While VNIR-HSI can effectively provide simultaneous data, the numerous variables also result in curses of dimensionality, which reduces the load and predictive capacity of the model. In this study, competitive adaptive reweighted sampling (CARS) and iterative retained information variable (IRIV) were used to reduce the dimension of variables. This is beneficial to the interpretability of variables and improves the accuracy of prediction models.

Figure 5.

Preprocessed of spectrum data. (a) Raw spectrum for all the samples; (b) S-G preprocessed spectrum for all the samples; (c) SNV preprocessed spectrum for all the samples; (d) S-G+SNV preprocessed spectrum for all the samples.

Figure 5.

Preprocessed of spectrum data. (a) Raw spectrum for all the samples; (b) S-G preprocessed spectrum for all the samples; (c) SNV preprocessed spectrum for all the samples; (d) S-G+SNV preprocessed spectrum for all the samples.

The CARS algorithm selects the optimal combination of effective variables in the spectrum by imitating the principle of "survival of the fittest" in Darwinian evolution [

38,

39]. For the spectrum array of m × p dimensions (m represents the number of samples, and p represents the number of variables), CARS selected the effective wavelengths through the following steps.

Based on monte carlo sampling (MCS), a PLS model is established by randomly selecting 80% of the calibration set of samples to obtain the regression coefficients |Ki| (i = 1, 2, ···, p) for the i-th wavelength;

The exponentially decreasing function (EDF) is applied to eliminate the wavelength with smaller |K

i|, and the retention rate of the variable is r

j = ae

-bj (j = 1, 2, ···, N). Among them, j represents the j-th MCS; N represents the number of MCS; a and b are constants, calculated by r

1 = 1 and r

N = 2/p, the formula are as follows;

-

The variables are further filtered based on the adaptive reweighted sampling (ARS) technique.

The variables were filtered by evaluating the weights (i = 1, 2, ···, p).

Repeat the above steps until the number of MCS reaches a predetermined value of N.

The 5-fold root mean square error of cross-validation (RMSEcv) is used as the evaluation criterion. The values of the subset of variables obtained from each MCS are compared, and the subset of variables corresponding to the minimum RMSEcv is selected as the optimal variable.

The iterative retaining information variable (IRIV) algorithm uses random combinations and interactions of variables to extract characteristic variables based on a binary matrix rearrangement filter [

40,

41,

42]. IRIV takes the following steps to select effective wavelengths.

The spectrum bands randomly generate an m × p matrix A containing only 0 and 1 (0 and 1 indicate whether the corresponding variables are involved in performing the modeling), with the same number of 0 and 1. The PLS model is established in each row of matrix A. The RMSEcv obtained from the 5-fold cross-validation is used as the evaluation criterion. This obtains an m × 1 vector denoted as RMSEcv0. Replace the 1 with 0 and the 0 with 1 in the i-th (i = 1, 2, ···, p) column of the A to obtain the matrix B. Similarly, a PLS model is established in each row of the B to obtain an m × 1 vector denoted as RMSEcvi;

Define Φ

0 and Φ

i to assess the importance of each variable with the following equations. The difference between the mean values of Φ

0 and Φ

i is denoted as DM

i. If DM

i < 0, it is a strong or weak information variable; If DM

i > 0, it is an uninformative or interfering variable. Mann-Whitney U-test is performed by defining P = 0.05 as the threshold. Finally, the variables are classified as strong information, weak information, uninformative, and interfering information;

In each iteration, strong and weak information variables are retained, and uninformative and interfering information variables are eliminated. Return to step 1) for the next iteration until only strong and weak information is left in the set of variables;

Backward elimination is performed for t retained variables. First, a PLS model is established for t variables to obtain RMSEcvt. Then, a PLS model is established for t-1 variables by eliminating the j-th (j = 1, 2, ···, t) variable to obtain RMSEcvj. If RMSEcvj is less than RMSEcvt, the j-th variable is eliminated, otherwise, it is retained. Loop this process, and the remaining variables are the final selected characteristic variables.

In this work, the CARA-IRIV algorithm was proposed by combining the advantages of the rapid iteration rate of CARS and the selection of strong and weak information variables by IRIV. It was used to screen pigment-related variables in leaves, thereby reducing the redundancy of explainable variables and improving model performance. Combined with PLS, the prediction models of CARS-PLS and CARS-IRIV-PLS were established, respectively. At the same time, 50 runs were performed on CARA-PLS and CARA-IRIV-PLS. The predictive ability of the model was evaluated by the coefficient determination of calibration (Rc2) and prediction (Rp2), root mean square error of calibration (RMSEc) and prediction (RMSEp), and ratio performance deviation (RPD). MATLAB software (Ver. 2018a, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) was used to process and analyze the data.

4.6. Visualization of leaf pigment

Hyperspectral imaging technology perfectly combines spectrum and image information, with each pixel on the image containing a spectrum curve. Aside from detecting the sample index, the detection index can be quantitatively inverted to the sample image combined with the optimal prediction model parameters to realize the visual expression of the index to be measured.

ENVI software (Ver. 5.1, Harris Geospatial, Broomfield, CO, USA) was used to process the corresponding wavelength multiplied by the weight coefficient to obtain the assignment value of each pixel, i.e., the leaf pigment content value. At the same time, the enhanced Lee filter was used to reduce the speckle noise. The filter size, damping coefficient, homogeneity zone, and heterogeneous zone were set to 3*3, 1, 0.52, and 1.73, respectively. Lastly, the pseudo-color map combined with the assignment size inverting the pixel points on the leaf image produces a visual representation of the content distribution.

5. Conclusions

In this study, Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro of leaves in Lycopersicon esculentum Mill seedlings were studied under different nitrogen concentration cultivation. VNIR-HSI technology combined with a machine learning algorithm was used to model the prediction of pigment content. Thus, it is convenient to realize the visualization of pigment expression. The nitrogen concentration of the nutrient solution was 302.84 mg/L, and the pigment content of the leaves was the largest. The distribution pattern of pigment content in leaf position was Upper > Middle > Lower. Meanwhile, the inhibitory effect of high concentration was stronger than that of low concentration, which could provide data support for quantitative management of nitrogen concentration of water and fertilizer in facility agriculture. The “coarse-fine” characteristic variable extraction strategy of CARS-IRIV is proposed, which can effectively reduce adjacent bands and retain effective information as much as possible. The PLSR was used to establish the prediction model for each pigment index to achieve better results. The model prediction accuracy was improved after characteristic wavelengths screening. Combining the CARS-IRIV-PLSR model with hyperspectral imaging technology effectively visualizes the expression of leaf pigments. The content of pigments and their distribution in leaves can be visualized, which helps to monitor the growth condition, pigment content, and nutrient diagnosis of plants in facility agriculture non-destructively.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Prediction results of pigments using different pre-processing methods; Table S2: Classification of variables screened by the CARS algorithm using the IRIV algorithm; Table S3. The key wavelengths screened by CARS and CARS-IRIV algorithms for Chla, Chlb, Chll, and Caro; Table S4: Fertilizer (mg/L), EC, and pH with different nitrogen concentrations; Figure S1: The changes in sample variables (NSV), RMSEcv, and regression coefficient paths (RCs) in a subset of CARS arithmetic for Chla; Figure S2: The changes in sample variables (NSV), RMSEcv, and regression coefficient paths (RCs) in a subset of CARS arithmetic for Chlb; Figure S3: The changes in sample variables (NSV), RMSEcv, and regression coefficient paths (RCs) in a subset of CARS arithmetic for Chll; Figure S4: The changes in sample variables (NSV), RMSEcv, and regression coefficient paths (RCs) in a subset of CARS arithmetic for Caro.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z.; methodology, J.Z., N.C. and T.Z.; Investigation, X.Z., M.Y., and Z.W.; Writing - original draft, J.Z. and G.W.; Writing - review and editing, J.Z., Z.L. and H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Major Special Projects of National Key R&D, grant number 2021YFD1600301-4; Major Special Projects of National Key R&D, grant number 2017YFD0701501; Major Special Projects of Shanxi Province Key R&D, grant number 201903D211005; Construction Project of Shanxi Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The pigment content of leaves was determined in the chemistry laboratory of Department of Basic Sciences (Shanxi Agricultural University). Here we sincerely thank Professor H.D.'s team for providing experiment instruments and reagents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests. The funders have no role in the experimental design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Zeeshan, M.; Ahmad, W.; Hussain, F.; et al. Phytostabalization of the heavy metals in the soil with biochar applications, the impact on chlorophyll, carotene, soil fertility and tomato crop yield. J CLEAN PROD. 2020, 255, 120318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjaja Putra, B.T.; Soni, P. Enhanced broadband greenness in assessing Chlorophyll a and b, Carotenoid, and Nitrogen in Robusta coffee plantations using a digital camera. PRECIS AGRIC. 2018, 19, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Huang, W.; Zhang, J.; et al. A novel combined spectral index for estimating the ratio of carotenoid to chlorophyll content to monitor crop physiological and phenological status. INT J APPL EARTH OBS. 2019, 76, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Sangwanangkul, P.; Baek, D.R. Changes in carotenoid and chlorophyll content of black tomatoes (Lycopersicone sculentum L.) during storage at various temperatures. SAUDI J BIOL SCI. 2018, 25, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeb, A.; Imran, M. Carotenoids, pigments, phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of Oxalis corniculata leaves. FOOD BIOSCI. 2019, 32, 100472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonobe, R.; Miura, Y.; Sano, T.; et al. Estimating leaf carotenoid contents of shade-grown tea using hyperspectral indices and PROSPECT–D inversion. INT J REMOTE SENS. 2018, 39, 1306–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Chen, G.; Xiong, L.; et al. Accurate digitization of the chlorophyll distribution of individual rice leaves using hyperspectral imaging and an integrated image analysis pipeline. FRONT PLANT SCI. 2017, 8, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Raja Reddy, K.; Kakani, V.G.; et al. Corn (Zea mays L.) growth, leaf pigment concentration, photosynthesis and leaf hyperspectral reflectance properties as affected by nitrogen supply. PLANT SOIL. 2003, 257, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Berjón, A.; Lopez-Lozano, R.; et al. Assessing vineyard condition with hyperspectral indices: Leaf and canopy reflectance simulation in a row-structured discontinuous canopy. REMOTE SENS ENVIRON. 2005, 99, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefsrud, M.; Kopsell, D.; Wenzel, A.; et al. Changes in kale (Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala) carotenoid and chlorophyll pigment concentrations during leaf ontogeny. SCI HORTIC-AMSTERDAM. 2007, 112, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmilovitch, Z.; Ignat, T.; Alchanatis, V.; et al. Hyperspectral imaging of intact bell peppers. BIOSYST ENG. 2014, 117, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, A.; Xianchang, Y.U.; Yansu, L.I. Seed priming as a promising technique to improve growth, chlorophyll, photosynthesis and nutrient contents in cucumber seedlings. NOT BOT HORTI AGROBO. 2020, 48, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong CY, S.; D'Odorico, P.; Bhathena, Y.; et al. Carotenoid based vegetation indices for accurate monitoring of the phenology of photosynthesis at the leaf-scale in deciduous and evergreen trees. REMOTE SENS ENVIRON. 2019, 233, 111407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.H.; Bin, J.; Liu, D.L.; et al. A hybrid variable selection strategy based on continuous shrinkage of variable space in multivariate calibration. ANAL CHIM ACTA. 2019, 1058, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahtmäe, E.; Kotta, J.; Orav-Kotta, H.; et al. Predicting macroalgal pigments (chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, chlorophyll a+ b, carotenoids) in various environmental conditions using high-resolution hyperspectral spectroradiometers. INT J REMOTE SENS. 2018, 39, 5716–5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Jin, G.; et al. Rapid prediction of chlorophylls and carotenoids content in tea leaves under different levels of nitrogen application based on hyperspectral imaging. J SCI FOOD AGR. 2019, 99, 1997–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, S.; Du, G.; Zhong, X.; et al. Quantification of Photosynthetic Pigments in Neopyropia yezoensis Using Hyperspectral Imagery. Plant Phenomics. 2023, 5, 0012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvao RK, H.; Araujo MC, U.; José, G.E.; et al. A method for calibration and validation subset partitioning. TALANTA. 2005, 67, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Zhu, X.; Shi, X.; et al. Determination of hesperidin in tangerine leaf by near-infrared spectroscopy with SPXY algorithm for sample subset partitioning and Monte Carlo cross validation. SPECTROSC SPECT ANAL. 2009, 29, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. STRATEGIC MANAGE J, 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Hair Jr J, Sarstedt M, Hopkins L; et al. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research. EUR BUS REV. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyło, A.; Nowicka, P.; Tkacz, K.; et al. Fruit tree leaves as unconventional and valuable source of chlorophyll and carotenoid compounds determined by liquid chromatography-photodiode-quadrupole/time of flight-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (LC-PDA-qTof-ESI-MS). FOOD CHEM. 2021, 349, 129156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niroula, A.; Khatri, S.; Timilsina, R.; et al. Profile of chlorophylls and carotenoids of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) microgreens. J FOOD SCI TECH MYS. 2019, 56, 2758–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harizanova, A.; Koleva-Valkova, L. Effect of silicon on photosynthetic rate and the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters at hydroponically grown cucumber plants under salinity stress. J CENT EUR AGRIC. 2019, 20, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcioni, R.; Antunes, W.C.; Demattê JA, M.; et al. A Novel Method for Estimating Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Concentrations in Leaves: A Two Hyperspectral Sensor Approach. SENSORS-BASEL. 2023, 23, 3843. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roca, M.; Pérez-Gálvez, A. Metabolomics of Chlorophylls and Carotenoids: Analytical Methods and Metabolome-Based Studies. ANTIOXIDANTS-BASEL. 2021, 10, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler H K, Babani F. and chlorophylls to carotenoids (a+b)/(x+c) in C4 plants as compared to C3 plants. PHOTOSYNTHETICA. 2022, 60, 3–9. [CrossRef]

- Kira, O.; Linker, R.; Gitelson, A. Non-destructive estimation of foliar chlorophyll and carotenoid contents: Focus on informative spectral bands. INT J APPL EARTH OBS. 2015, 38, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupellini, L.; Calvani, D.; Jacquemin, D.; et al. Charge transfer from the carotenoid can quench chlorophyll excitation in antenna complexes of plants. NAT COMMUN. 2020, 11, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balevičius, V.; Duffy CD, P. Excitation quenching in chlorophyll–carotenoid antenna systems:‘coherent’or ‘incoherent’. PHOTOSYNTH RES. 2020, 144, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinsberg, D.; Ottmann, K.; Booth, P.J.; et al. Effects of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and xanthophylls on the in vitro assembly kinetics of the major light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b complex, LHCIIb. J MOL BIOL. 2001, 308, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Baran, C.; Tripathi, A.; et al. Phytochemical screening of the different cultivars of ixora flowers by non-destructive, label-free, and rapid spectroscopic techniques. ANAL LETT. 2021, 54, 2276–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Wang, Q. Developing Hyperspectral Indices for Assessing Seasonal Variations in the Ratio of Chlorophyll to Carotenoid in Deciduous Forests. REMOTE SENS-BASEL. 2022, 14, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Ying, K.; Bai, J. Savitzky - Golay smoothing and differentiation filter for even number data. SIGNAL PROCESS. 2005, 85, 1429–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candan, Ç.; Inan, H. A unified framework for derivation and implementation of Savitzky–Golay filters. SIGNAL PROCESS. 2014, 104, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, R.J.; Dhanoa, M.S.; Lister, S.J. Standard normal variate transformation and de-trending of near-infrared diffuse reflectance spectra. APPL SPECTROSC. 1989, 43, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Li, C.; Fu, X.; et al. Protected Geographical Indication Discrimination of Zhejiang and Non-Zhejiang Ophiopogonis japonicus by Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy Combined with Chemometrics: The Influence of Different Stoichiometric and Spectrogram Pretreatment Methods. MOLECULES. 2023, 28, 2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida TI, R.; Filho, D.S. Principal component analysis applied to feature-oriented band ratios of hyperspectral data: a tool for vegetation studies. INT J REMOTE SENS. 2004, 25, 5005–5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liang, Y.; Xu, Q.; et al. Key wavelengths screening using competitive adaptive reweighted sampling method for multivariate calibration. ANAL CHIM ACTA. 2009, 648, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Huang, Y.; Tian, K.; et al. A new spectral variable selection pattern using competitive adaptive reweighted sampling combined with successive projections algorithm. ANALYST. 2014, 139, 4894–4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.H.; Wang, W.T.; Tan, M.L.; et al. A strategy that iteratively retains informative variables for selecting optimal variable subset in multivariate calibration. ANAL CHIM ACTA. 2014, 807, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, B.; Yun, Y.; Liang, Y.; et al. A novel variable selection approach that iteratively optimizes variable space using weighted binary matrix sampling. ANALYST. 2014, 139, 4836–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).