Submitted:

03 April 2024

Posted:

03 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

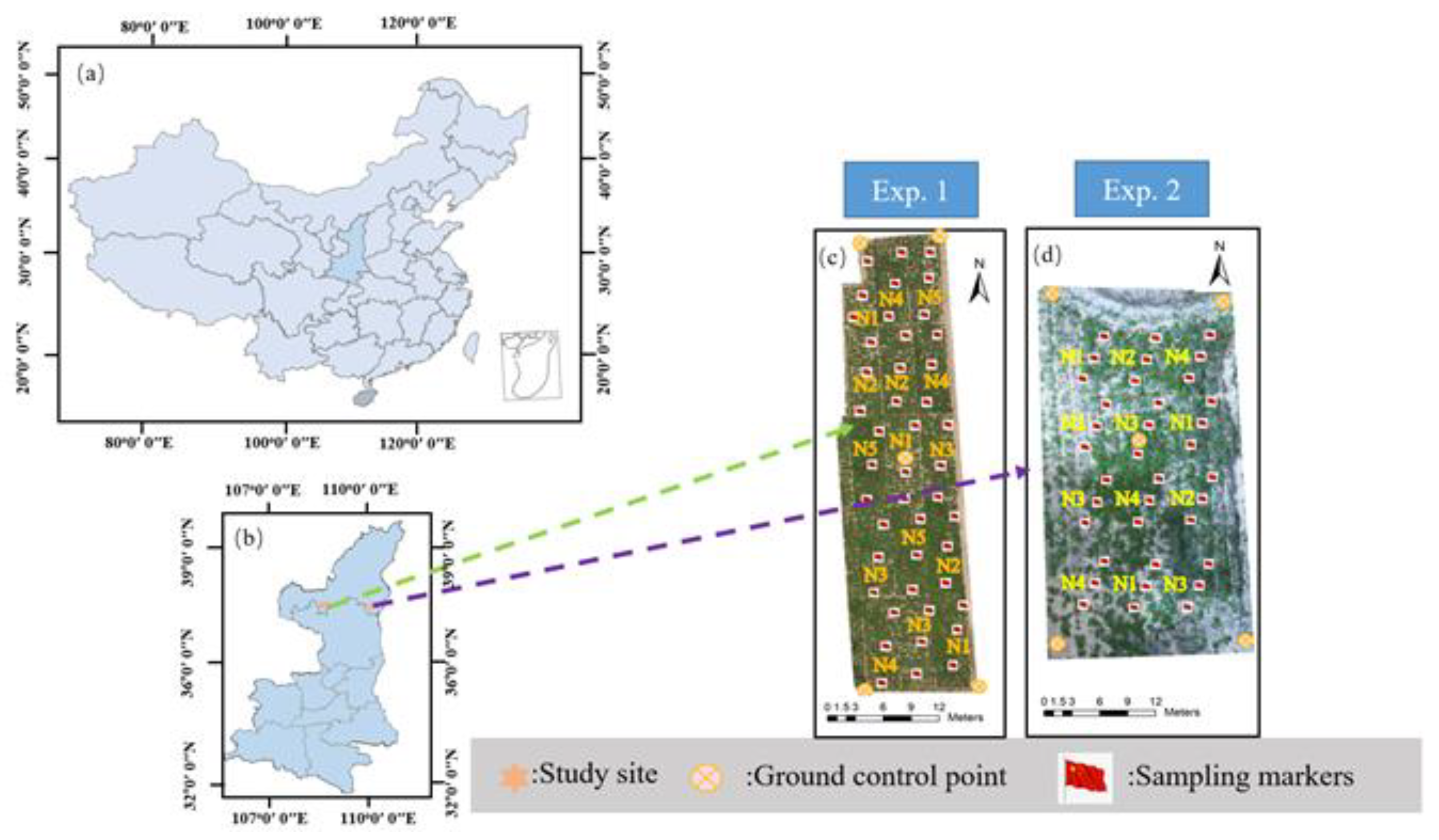

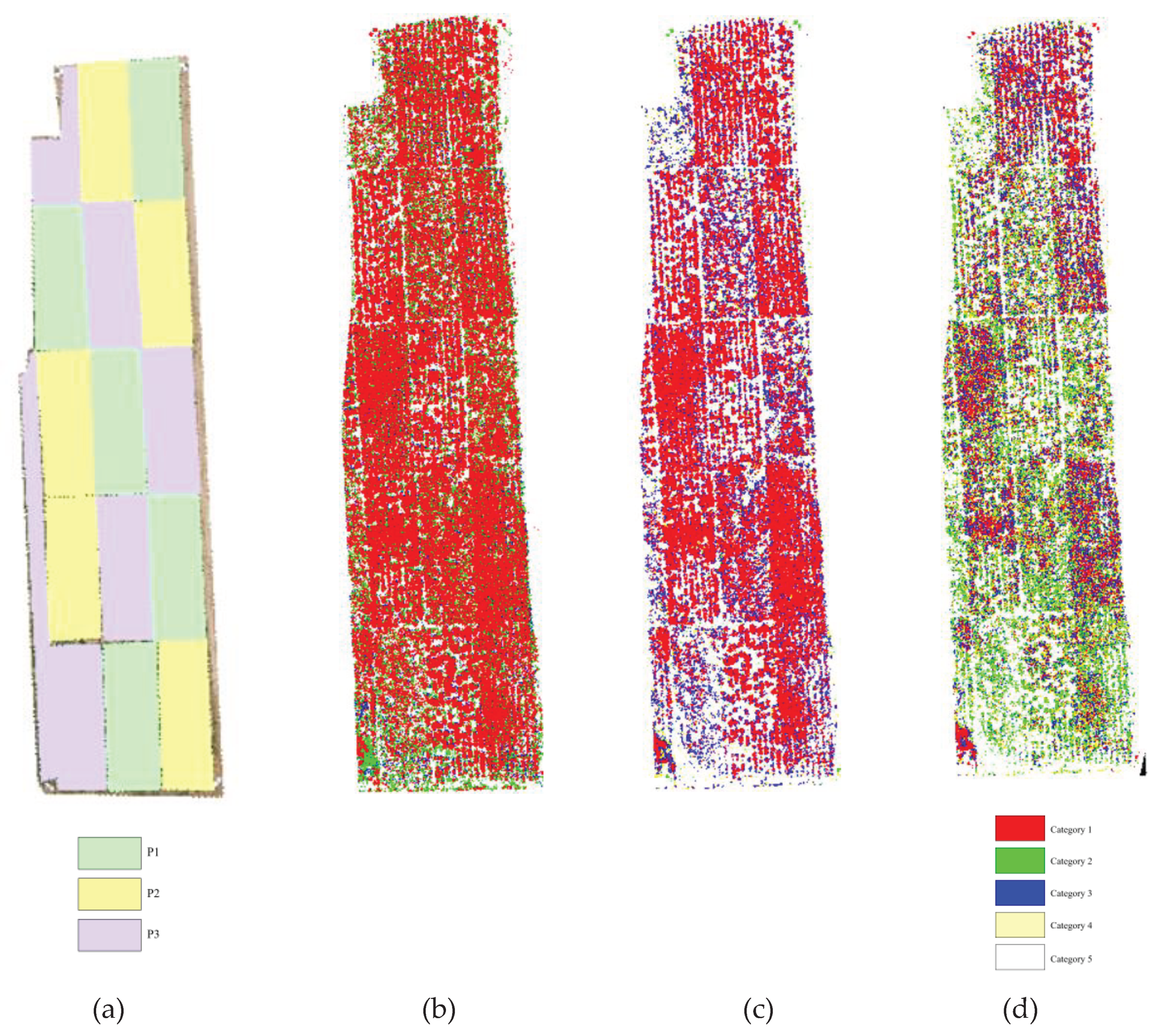

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Experiment Description

2.3. Chlorophyll Content Measurement

2.4. UAV -Based Multispectral Images Collection and Preprocessing

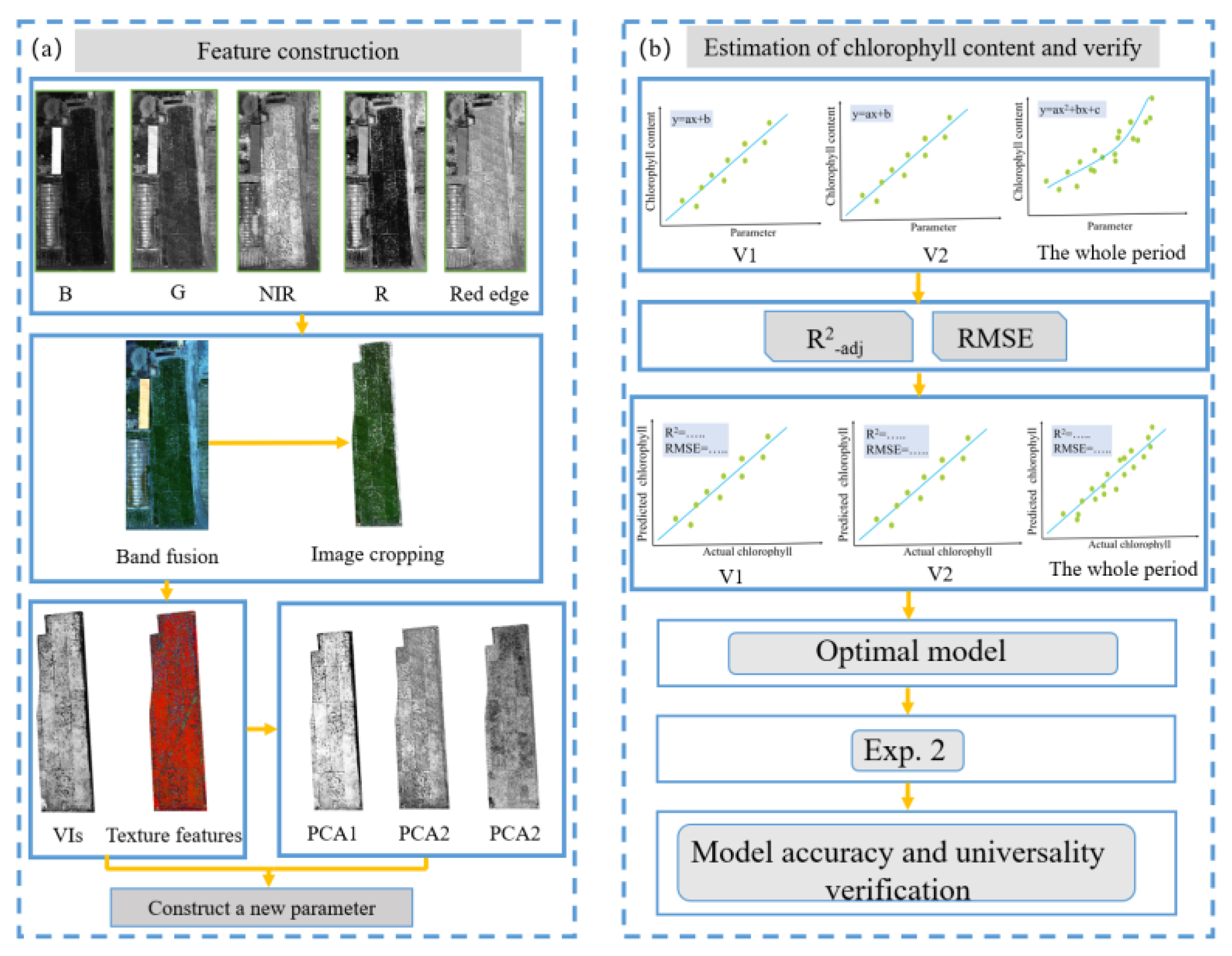

2.5. Methodology

2.5.1. The Calculation of VIs and Texture Features

2.5.2. Screen of Characteristic Parameters

2.5.3. Characteristic Parameter Construction

2.5.4. Accuracy Evaluation

3. Results

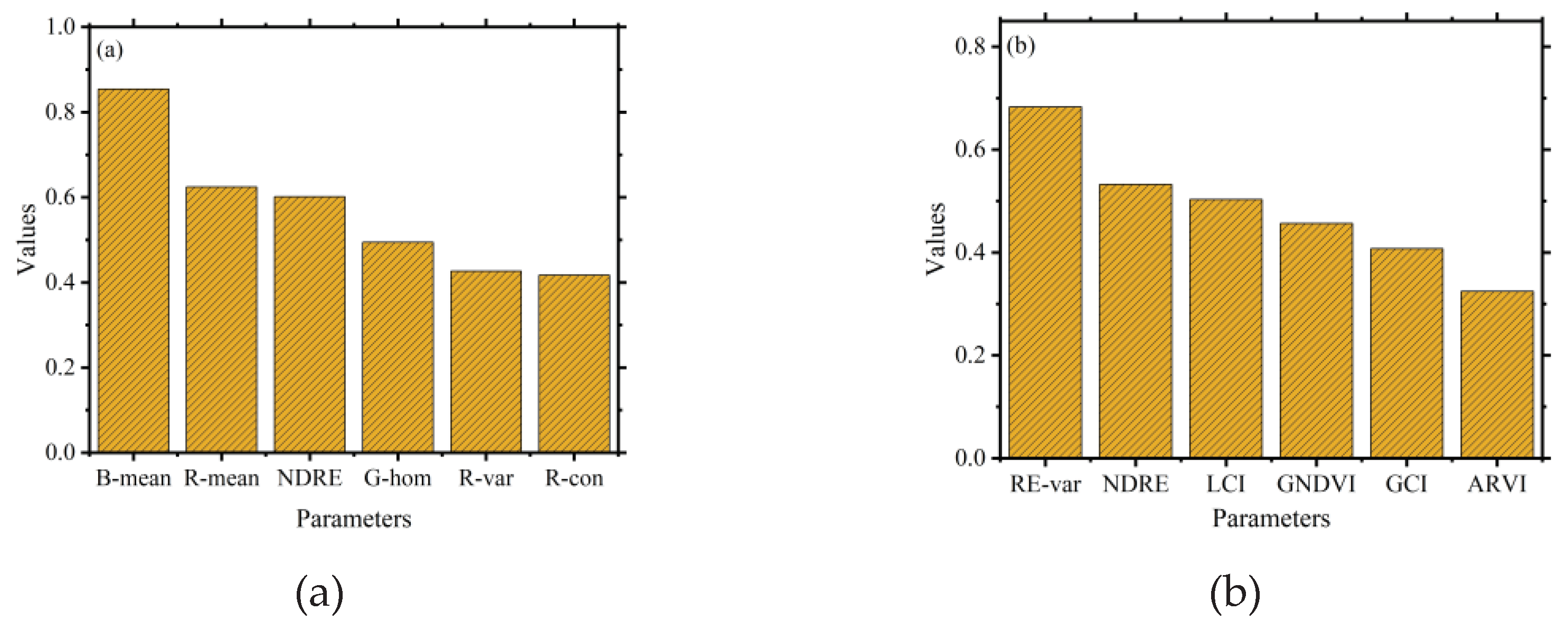

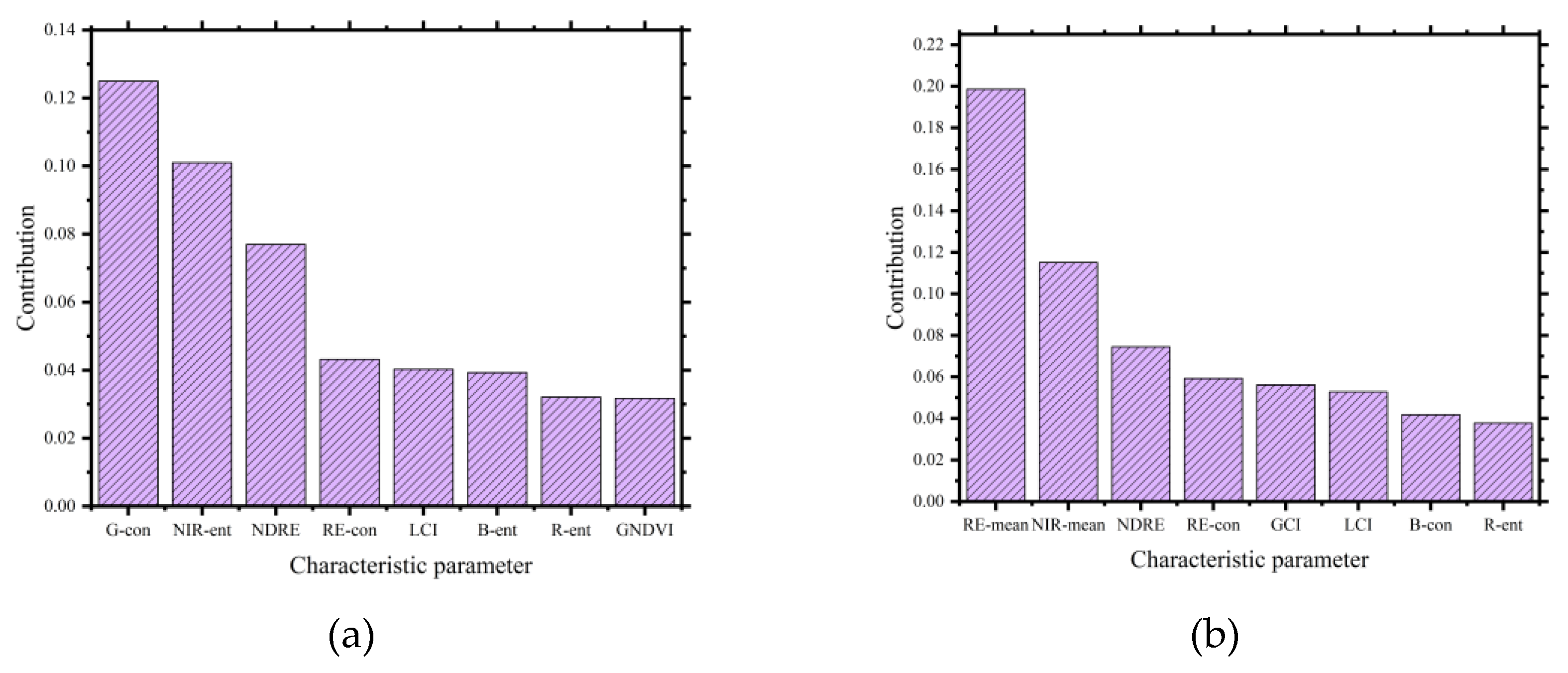

3.1. Feature Filtering Results

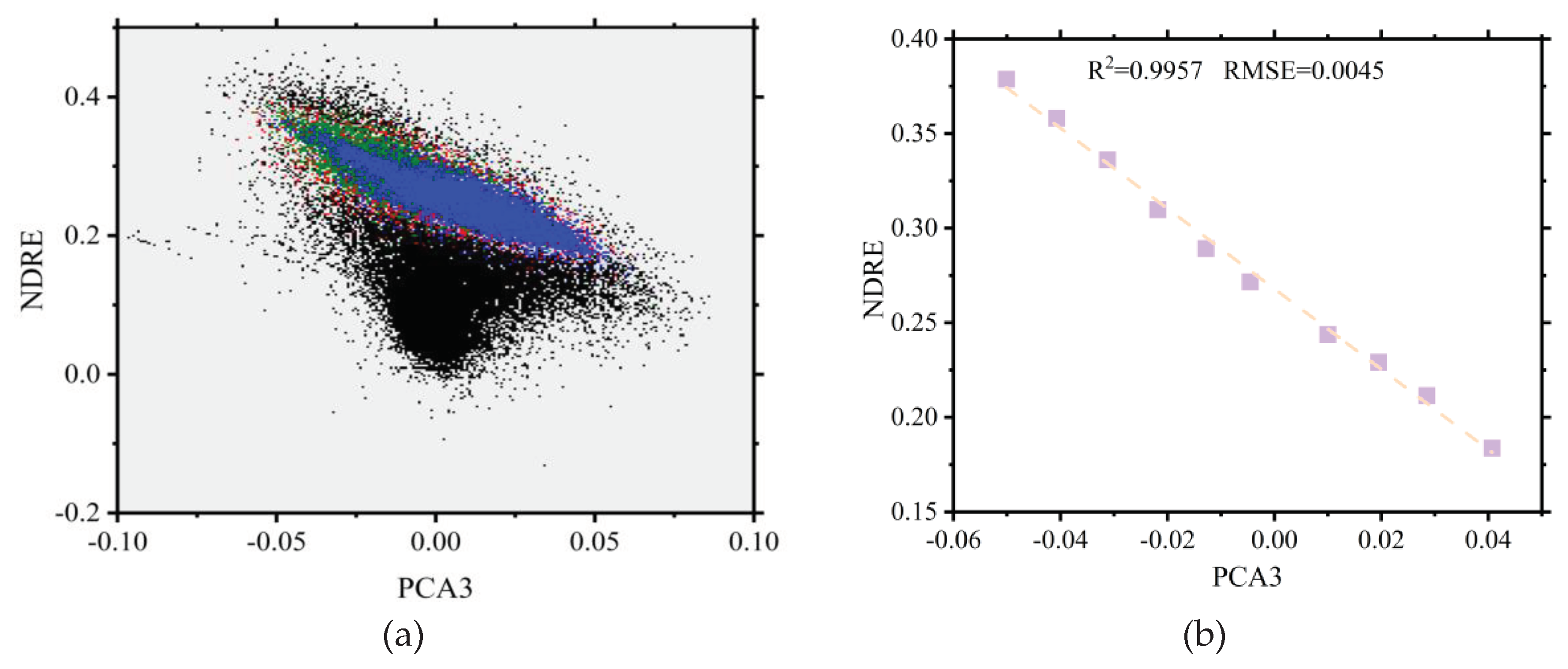

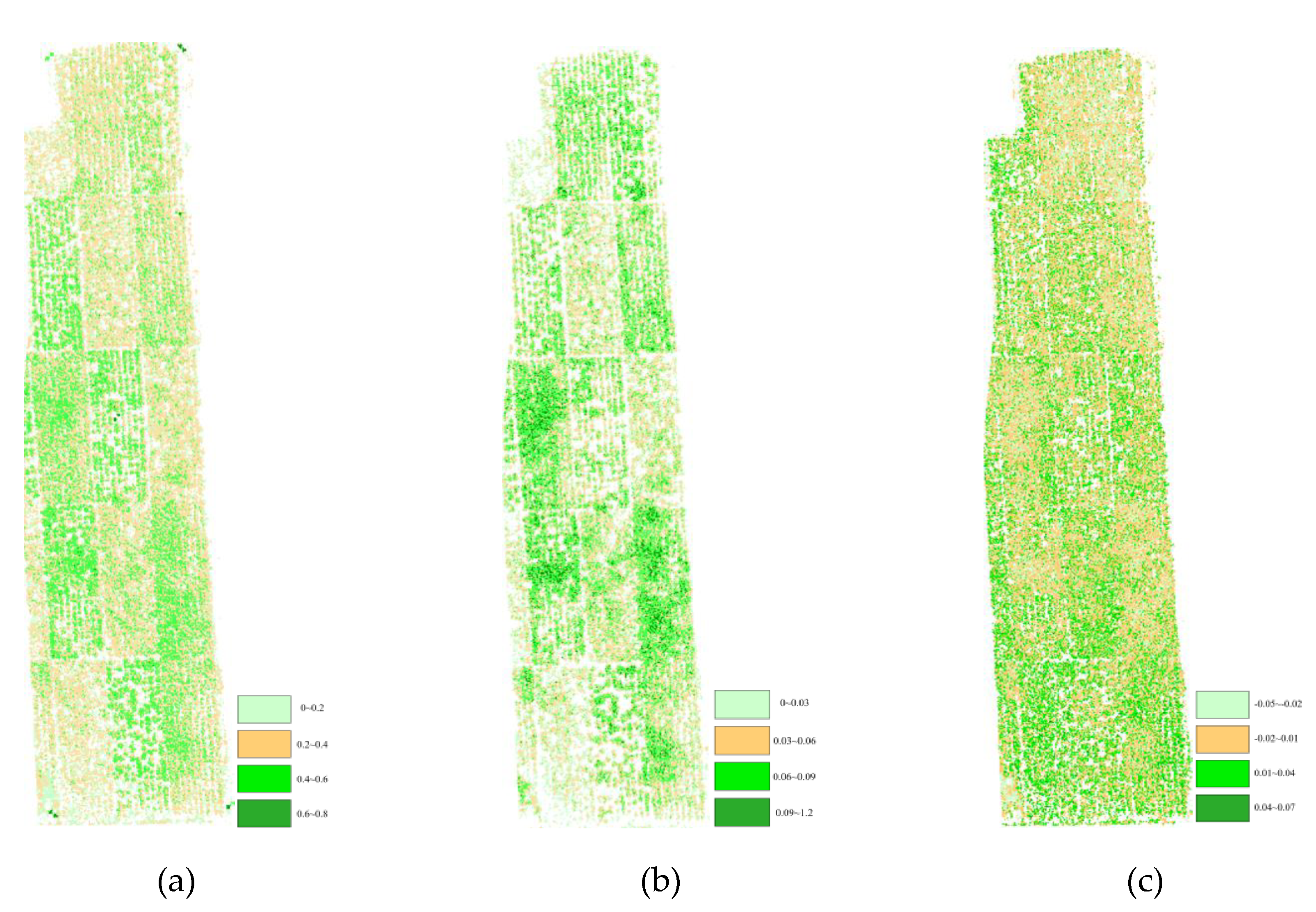

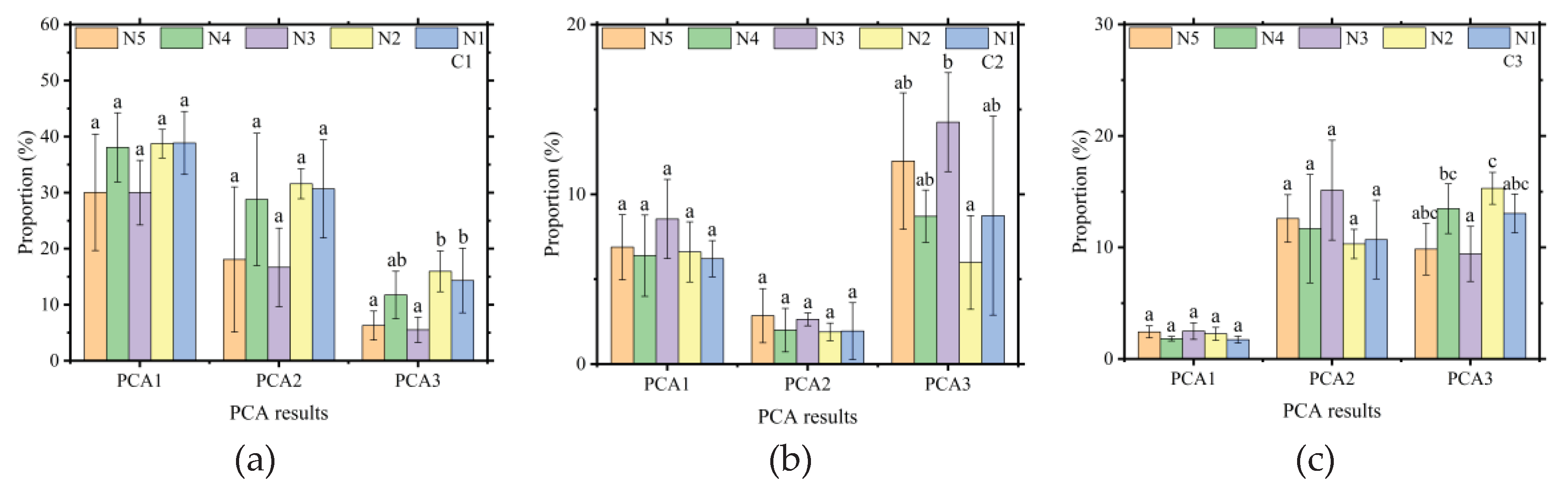

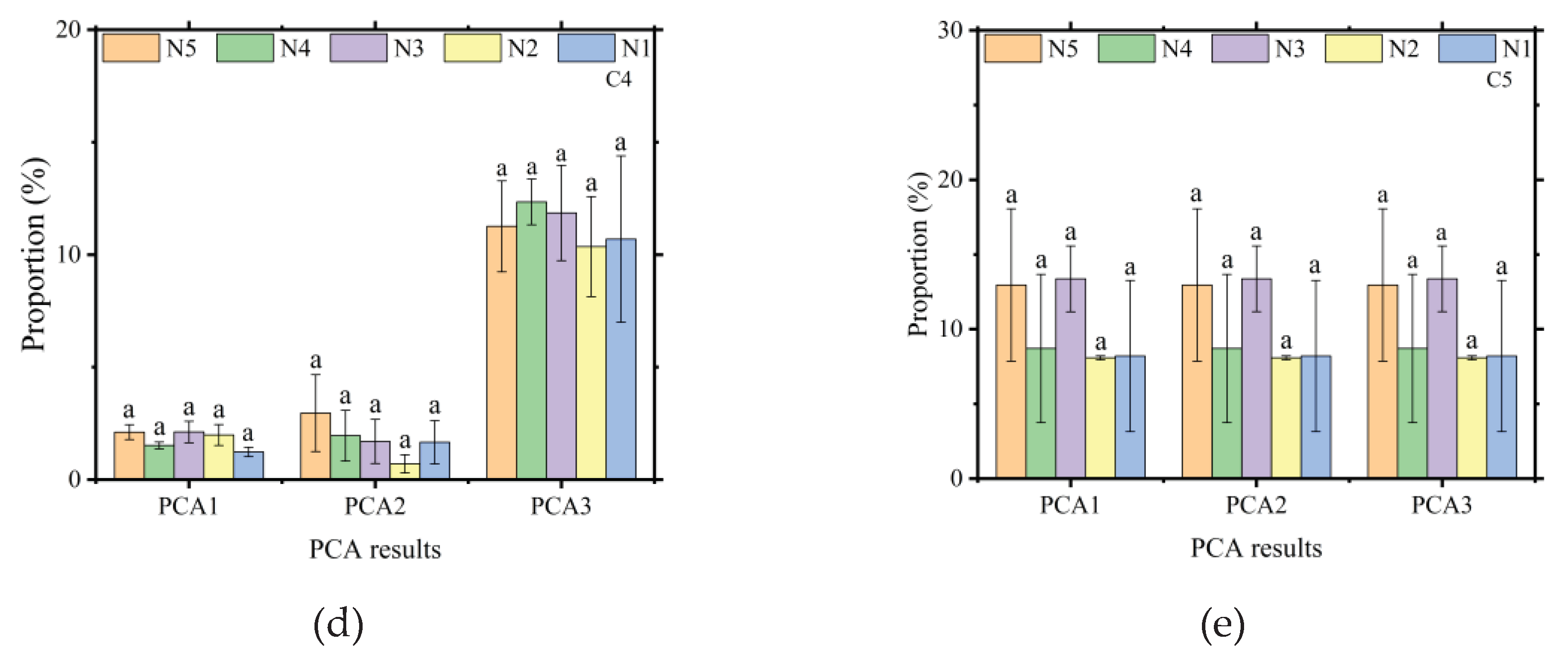

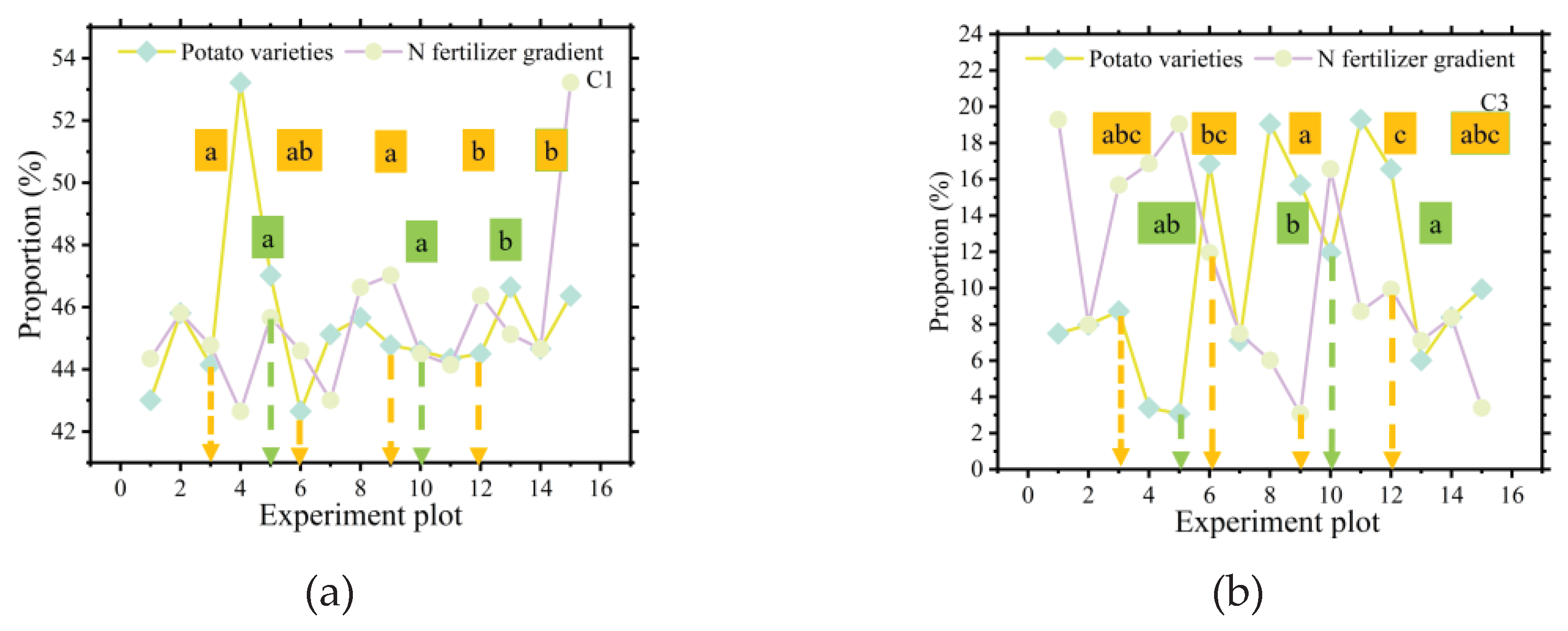

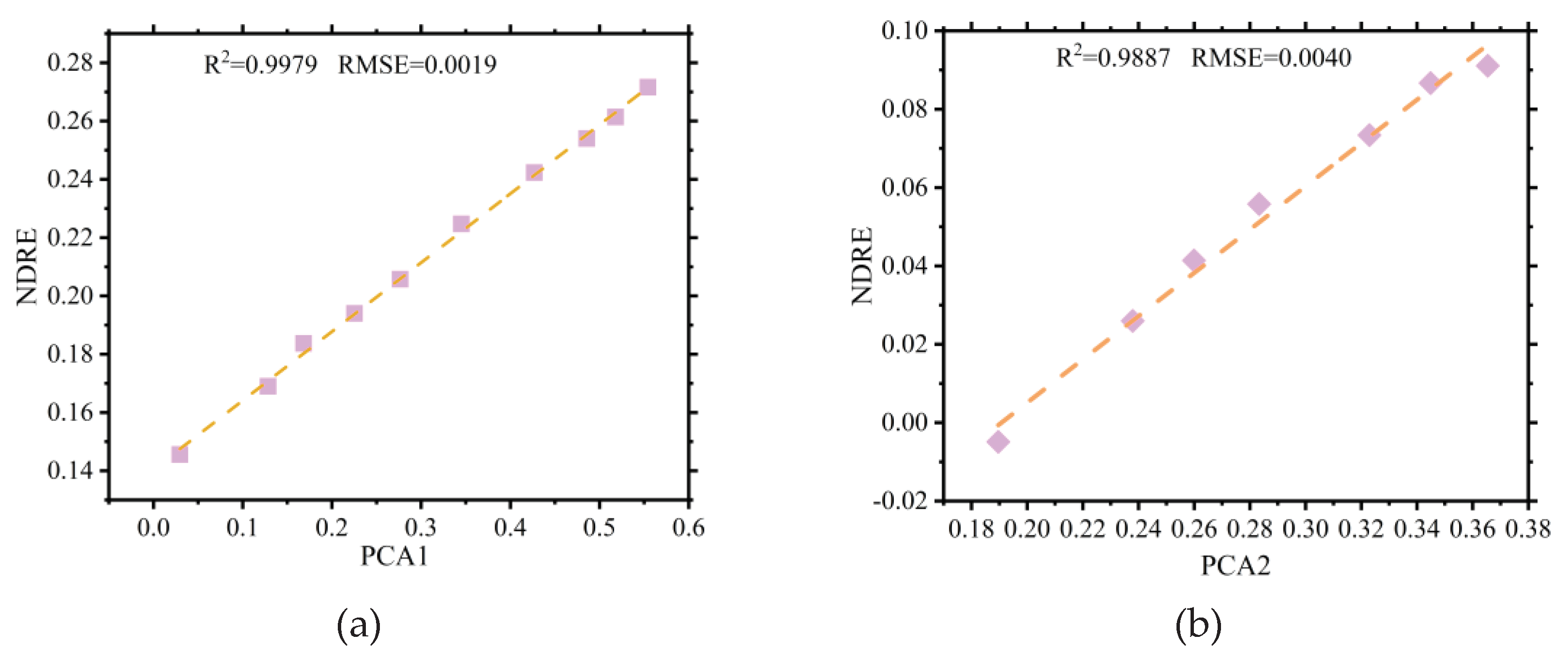

3.2. Feature Construction Results

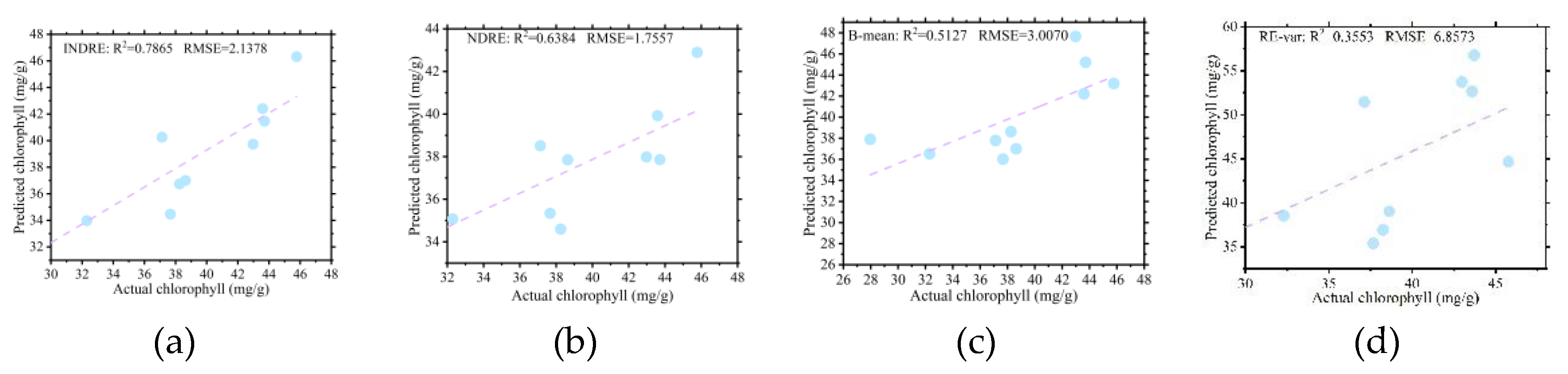

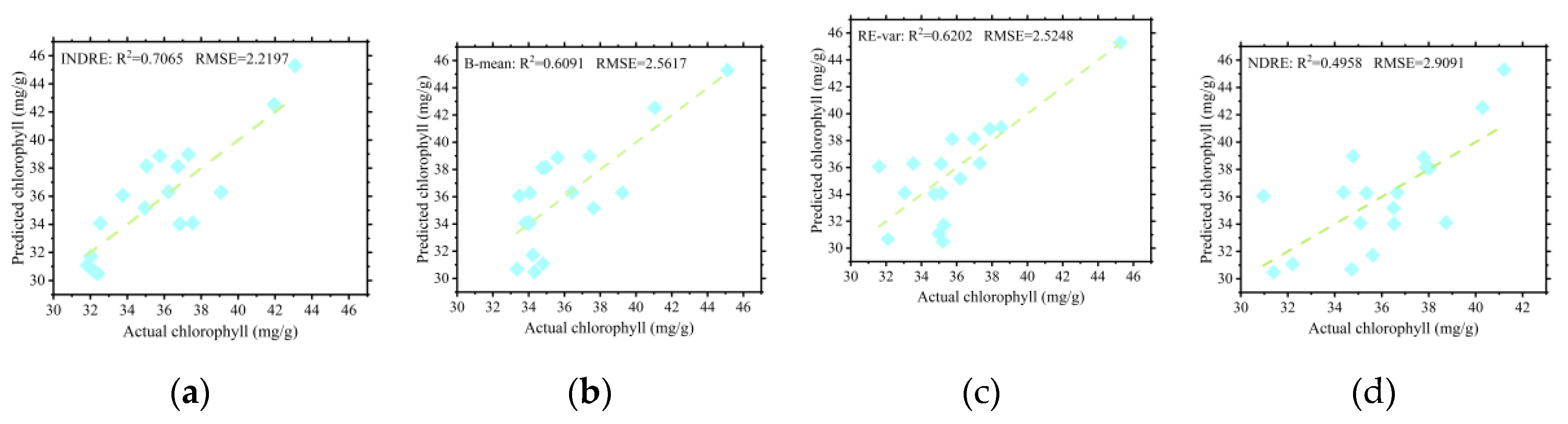

3.3. Results of Chlorophyll Content Estimation

4. Discussion

4.1. Universality of Chlorophyll Content Estimation Models

4.2. Comparison of Different Feature Selection Algorithms

4.3. The Effect of Fitting Parameter Selection on Estimation Accuracy

4.4. Significance, Advantages, and Disadvantages of This Study

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The screening results of the Pearson correlation coefficient method showed that the NDRE had the highest correlation with chlorophyll content at 75th day after potato planting. Although the feature screening results of RF showed that the contribution of NDRE in the two growth periods of potato plants was not the highest, combining the screening results of the two periods, NDRE had achieved well performance.

- (2)

- The PCA1 and PCA 2 of experimental field were greatly influenced by potato varieties, and the PCA3 was negatively correlated with N application rate. Moreover, NDRE had a negative correlation with the PCA3, which could be effectively combined.

- (3)

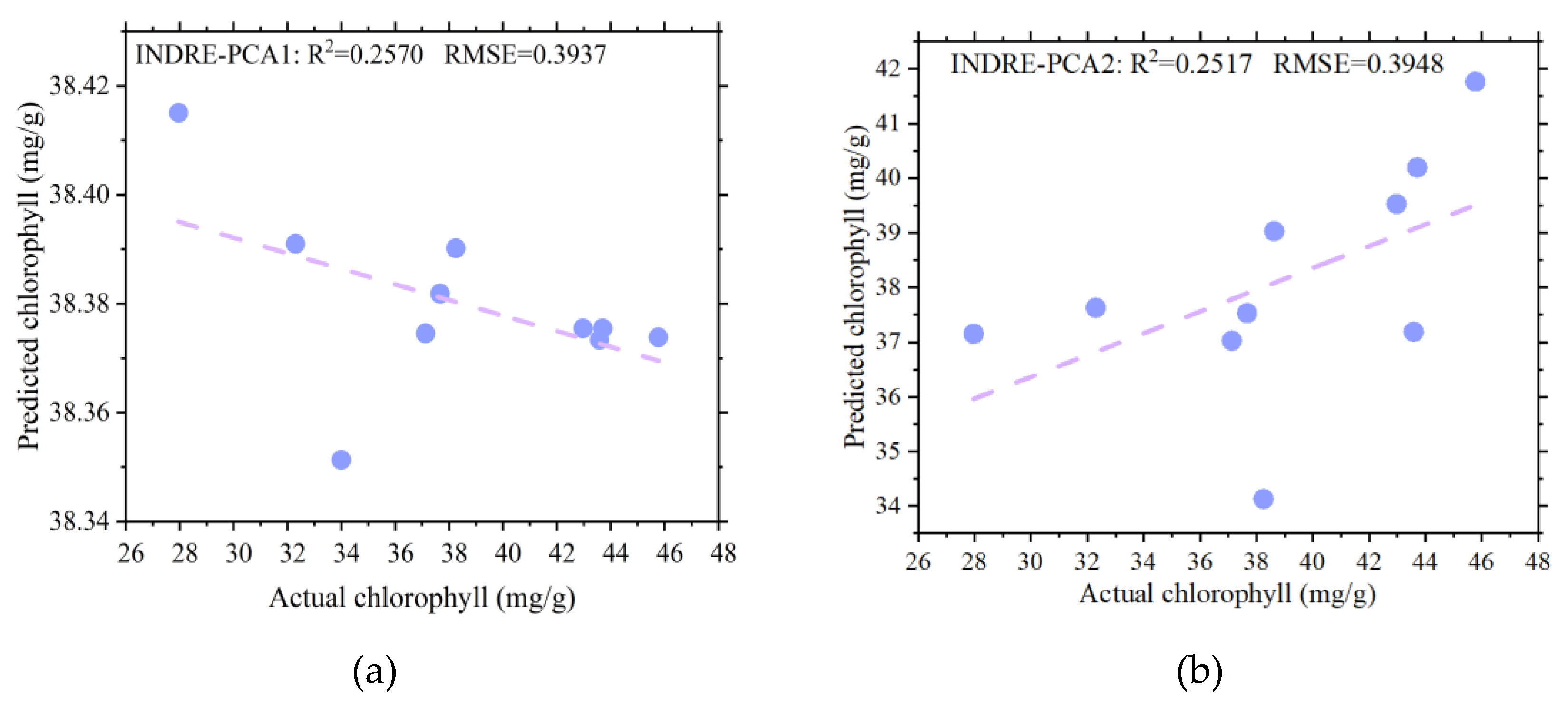

- The INDRE, proposed on the basis of the the construction principle of NDRE, and combining the NDRE with the PCA3 significantly improved the estimation accuracy of chlorophyll content. However, the INDRE constructed separately based on the PCA1 and PCA2 did not achieve promising performance. Besides, the model used for chlorophyll content retrieval in Exp.1 also performed well in Exp.2, which proved that the INDRE proposed in this paper had better estimation accuracy and robustness of chlorophyll content in potato plants.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- An, L.; Tang, W.; Qiao, L.; Zhao, R.; Sun, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, X. , Estimation of chlorophyll distribution in banana canopy based on RGB-NIR image correction for uneven illumination. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 202, 107358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; An, L.; Tang, W.; Gao, D.; Qiao, L.; Li, M.; Sun, H.; Qiao, J. , Deep learning assisted continuous wavelet transform-based spectrogram for the detection of chlorophyll content in potato leaves. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 195, 106802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Colombo, R.; Rossini, M.; Celesti, M.; Zhu, J.; Cogliati, S.; Cheng, T.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Yao, X. , Estimation of leaf nitrogen content and photosynthetic nitrogen use efficiency in wheat using sun-induced chlorophyll fluorescence at the leaf and canopy scales. European Journal of Agronomy 2021, 122, 126192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Yin, B.; Zhou, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y.; Han, R.; Shi, C.; Liang, B.; Xu, J. , Melatonin and dopamine mediate the regulation of nitrogen uptake and metabolism at low ammonium levels in Malus hupehensis. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2022, 171, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Fu, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, P.; He, S.; Shao, H.; Ni, Z.; Zhang, X. , Effects of irrigation and nitrogen on chlorophyll content, dry matter and nitrogen accumulation in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L. ). Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 16651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Tang, W.; Gao, D.; Zhao, R.; An, L.; Li, M.; Sun, H.; Song, D. , UAV-based chlorophyll content estimation by evaluating vegetation index responses under different crop coverages. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 196, 106775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhen, J.; Miao, J.; Zhao, D.; Shen, Z.; Jiang, J.; Gao, C.; Wu, G.; Wang, J. , Newly-developed three-band hyperspectral vegetation index for estimating leaf relative chlorophyll content of mangrove under different severities of pest and disease. Ecological Indicators 2022, 140, 108978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. , SPAD monitoring of saline vegetation based on Gaussian mixture model and UAV hyperspectral image feature classification. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 200, 107236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiyan, S.; Mengyuan, S.; Qizhou, D.; Xiaohong, Y.; Baoguo, L.; Yuntao, M. , Estimating the maize above-ground biomass by constructing the tridimensional concept model based on UAV-based digital and multi-spectral images. Field Crops Research 2022, 282, 108491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zarco-Tejada, P. J.; Schmidhalter, U.; Reynolds, M. P.; Hawkesford, M. J.; Varshney, R. K.; Yang, T.; Nie, C.; Li, Z.; Ming, B.; Xiao, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, S. , High-Throughput Estimation of Crop Traits: A Review of Ground and Aerial Phenotyping Platforms. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2021, 9, 200–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, R.; Ye, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, D.; Hua, K. , Winter wheat SPAD estimation from UAV hyperspectral data using cluster-regression methods. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2021, 105, 102618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yang, G.; Song, X.; Li, Z.; Xu, X.; Feng, H.; Zhao, C. , Improved estimation of winter wheat aboveground biomass using multiscale textures extracted from UAV-based digital images and hyperspectral feature analysis. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Tan, X.; Raza, M. A.; Ma, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, F.; Yang, W. , Assessing canopy nitrogen and carbon content in maize by canopy spectral reflectance and uninformative variable elimination. The Crop Journal 2022, 10, 1224–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Cunha, M.; Jayavelu, S.; Cammarano, D.; Fu, Y. , Machine Learning-Based Approaches for Predicting SPAD Values of Maize Using Multi-Spectral Images. In Remote Sensing, 2022; Vol. 14.

- Sudu, B.; Rong, G.; Guga, S.; Li, K.; Zhi, F.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bao, Y. , Retrieving SPAD values of summer maize using UAV hyperspectral data based on multiple machine learning algorithm. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. ; P.; G.; Rigon; S.; Capuani; D.; M.; Fernandes; T., A novel method for the estimation of soybean chlorophyll content using a smartphone and image analysis. Photosynthetica 2016, 54, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Hua, W.; Zou, J.; He, J.; Hui, D. , Effects of Nitrogen Application Rate and Leaf Age on the Distribution Pattern of Leaf SPAD Readings in the Rice Canopy. Plos One 2014, 9, e88421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Hou, B.; Chen, J. , A New Approach for Nitrogen Status Monitoring in Potato Plants by Combining RGB Images and SPAD Measurements. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Jun, Z.; Zhu, B. , Monitoring of peanut leaves chlorophyll content based on drone-based multispectral image feature extraction. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 187, 106292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Guo, T.; Chen, J. , Estimation of Potato Chlorophyll Content from UAV Multispectral Images with Stacking Ensemble Algorithm. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, G.; Bansod, B.; Mathew, L.; Goswami, J.; Choudhury, B. U.; Raju, P. L. N. , Chlorophyll estimation using multi-spectral unmanned aerial system based on machine learning techniques. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 2019, 15, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hui, J.; Qin, Q.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, H.; Li, M. , Transfer-learning-based approach for leaf chlorophyll content estimation of winter wheat from hyperspectral data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2021, 267, 112724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Gu, X.; Chen, L.; Xu, X.; Wei, Z.; Pan, Y.; Gao, Y. , Monitoring maize canopy chlorophyll density under lodging stress based on UAV hyperspectral imagery. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 193, 106671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, M.; Shen, M.; Zuo, J.; Yin, P.; Wang, M.; Xie, Z.; Tang, J.; Wang, R.; Li, B.; Yang, X.; Ma, Y. , The Application of UAV-Based Hyperspectral Imaging to Estimate Crop Traits in Maize Inbred Lines. Plant Phenomics 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, G.; Han, W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, P. , Estimation of transpiration coefficient and aboveground biomass in maize using time-series UAV multispectral imagery. The Crop Journal 2022, 10, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lan, Y.; Lu, L.; Gong, D.; Miao, J.; Zhao, J. , New method for cotton fractional vegetation cover extraction based on UAV RGB images. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 2022, 15, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi-Nasab, F. S.; Parastar, H. , VIs-NIR hyperspectral imaging coupled with independent component analysis for saffron authentication. Food Chemistry 2022, 393, 133450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xuan, G.; Li, Q.; Wang, F.; Shi, C.; Hu, Z. , Hyperspectral imaging for non-destructive detection of honey adulteration. Vibrational Spectroscopy 2022, 118, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Jaramillo, V.; Fries, A.; Bendix, J. , AGB Estimation in a Tropical Mountain Forest (TMF) by Means of RGB and Multispectral Images Using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, H.; Gebbers, R. , Assessing Nitrogen and water status of winter wheat using a digital camera. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 157, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Y. J.; Tanre, D. , Atmospherically resistant vegetation index (ARVI) for EOS-MODIS. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 1992, 30, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilabert, M. A.; González-Piqueras, J.; Garcı́a-Haro, F. J.; Meliá, J. , A generalized soil-adjusted vegetation index. Remote Sensing of Environment 2002, 82, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Gao, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Sun, H.; Ma, J. , Dynamic influence elimination and chlorophyll content diagnosis of maize using UAV spectral imagery. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Gao, S.; Chi, H.; Qi, J.; Song, W.; Tong, Y.; Mu, X.; Yan, G. , Evaluation of the Vegetation-Index-Based Dimidiate Pixel Model for Fractional Vegetation Cover Estimation. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, T. W.; Carlson, T. N.; Gillies, R. R. , An assessment of satellite remotely-sensed land cover parameters in quantitatively describing the climatic effect of urbanization. International Journal of Remote Sensing 1998, 19, 1663–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Cárdenas, D. A.; Ramón Valencia, J. A.; Alzate Velásquez, D. F.; Palacios Gonzalez, J. R. In Dynamics of the Indices NDVI and GNDVI in a Rice Growing in Its Reproduction Phase from Multi-spectral Aerial Images Taken by Drones, Advances in Information and Communication Technologies for Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change II, Cham, 2019//, 2019; Corrales, J. C.; Angelov, P.; Iglesias, J. A., Eds. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp 106-119.

- Virnodkar, S. S.; Pachghare, V. K.; Patil, V. C.; Jha, S. K. , Remote sensing and machine learning for crop water stress determination in various crops: a critical review. Precision Agriculture 2020, 21, 1121–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamid, F. A.; Bdier, D. , The Association Between Positive Religious Coping, Perceived Stress, and Depressive Symptoms During the Spread of Coronavirus (COVID-19) Among a Sample of Adults in Palestine: Across Sectional Study. Journal of Religion and Health 2021, 60, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Gao, M.; Cao, C.; You, J.; Zhang, X.; Shen, L. , Winter wheat chlorophyll content retrieval based on machine learning using in situ hyperspectral data. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 193, 106728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, J.; Qin, Y.; Fan, M. , Possibility of using a SPAD chlorophyll meter to establish a normalized threshold index of nitrogen status in different potato cultivars. Journal of Plant Nutrition 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L. C.; Faria, R. M.; De Souza, E.; Veloso, G. V.; Schaefer, C. E. G. R.; Filho, E. I. F. , Modelling and mapping soil organic carbon stocks in Brazil. Geoderma 2019, 340, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Plauborg, F.; Thomsen, A. G.; Andersen, M. N. , A RVI/LAI-reference curve to detect N stress and guide N fertigation using combined information from spectral reflectance and leaf area measurements in potato. European Journal of Agronomy 2017, 87, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| UAV | Camera | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Values | Parameters | Values |

| Product type | Quadcopter | Color output | Global shutter, and all spectral bands aligned |

| Longest flight time /min | 27 | Focal length/mm | 5.74 |

| Maximum takeoff weight /kg | 1.487 | Field of view/ (◦) | 62.7 |

| Operating temperature/℃ | 0-40 | Pixels | 1600×1300 |

| Digital communication distance/km | 7 | Wave length/mm | 200-800 |

| Maximum withstand wind speed(m/s) | 8 | Capture rate (time/s) | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).