1. Introduction

In her book Kissing architecture, Sylvia Lavin extensively discusses dichotomies embedded deeply into the body of architecture as a discipline: one that contests it’s ability to socially engage versus establishing neutral autonomy of the discipline, as well as the one where discipline is considered to be a measure/model for the wholeness of cultural production, contrary to periods where it is defined only in terms of difference from other mediums. [

1] These dichotomies can, furthermore, be discussed formally as well, in terms of classification of the architecture as a field of research, where an ongoing debate whether it belongs to the arts or sciences creates a form of internal disciplinary confusion, regarding the architectural method itself, measuring progress or measurements of the final results, both in terms of practice or academic achievement. [

2,

3] These divisions create great bias in the minds of architects that can furthermore be deepened when new technology is introduced to the discipline. [

4,

5] Rapid development of software tools which created a radical shift in architectural practice, besides increased efficiency, also introduced a new set of limitations associated with the limitations of the software itself. Some authors [

6] even find design technologies, rather than influencing incremental change, being totalitarian in their effects. On the other hand, the problem of classifying architecture as a discipline can be observed as a new paradigm in itself. This point of view calls for externalization, meaning that the discipline and its design method should be observed from beyond the limits of architecture.

This perspective can be compared to the term of metafiction, or even more precise poioumenon. This term comes from the field of postmodern literature and is usually used for the literary works that use a process of creating another literary work as a main motif. The term (coming from Ancient Greek and meaning “product” in direct translation) was coined by Alastair Fowler in order to refer to a specific type of metafiction: “the poioumenon is calculated to offer opportunities to explore the boundaries of fiction and reality—the limits of narrative truth.” [

7] These limits of narrative truth, or the ones between reality and fiction, can easily be recognized as constitutive attributes of the architectural design process, since design itself always aims at something that is not existing in the present time, thus being the form of critique. [

8] As Boris Groyce suggests, this functions as a Derridean pharmakon: while design can elevate the experience of using a designed object or space, at the same time it opens a new arena of questions regarding the actual characteristics of the object before design, emphasizing the negative sides. This further expands the space between real (or what-is- reality) and virtual or designed (what-could-be-reality). Often this gap is continued even after the architectural space becomes built or real, where it now takes the form of the difference between the expected and the materialized. This divergence points out that it is necessary to review the boundaries of the virtual and the real in the design process, that is, to observe the method from a position outside the architecture as discipline, while considering the complexity of its nature.

To do so, it is very important to try to cover the scope of architectural work. According to the RIBA, only 6% of new homes in the UK are designed by architects. [

9] Also, architects design only a small percentage of what gets built in the United States, leaving around 75% of all new construction in the form of the urban sprawl landscape [

10] “a landscape almost entirely uninformed by the critical agendas or ideas of the discipline”. On the other hand, hundreds of architectural practices are ready to compete for a single project of a significant public project. We can conclude that, in order to increase the impact of the discipline on society, architectural practices should also open towards expanding portfolio so that they can cover different architectural programmes, even the ones that possibly lack public visibility. This expansion would open up the need for a new type of work organization within architectural practices and lead to possible changes in the system of architectural education.

Substantial knowledge is required in conceptual architectural design: knowledge about various requirements (functional, formal, programmatic, urban parameters, lifestyles etc.), as well as broad concepts and their interplay, etc.

Unfortunately in the conceptual design stage, such knowledge is often incomplete, meaning that the designers may have limited understanding of what should be treated as important requirements, promising concepts, and how the requirements and concepts may affect each other, etc. Their understanding of these issues may become even more limited when confronted with many conflicting requirements and competing concepts. As a result, initial requirements and concepts are often vague, uncertain, and incomplete; more generally speaking, a number of issues in conceptual architectural design are ill-defined [

11,

12]. This leads to an increased number of changes during the design process, as well as iterations through which the optimal solution is to be achieved. These iterations, sometimes obtaining the form of a complete conceptual solution are usually lost — in the sense of becoming materialized — meaning that they keep their virtual form forever. Also, due to reasons stated above, even when the project is built, it can fail to meet the expectations, because of insufficient parameters included in the design or unexpected circumstances that occurred during the building process that were not eligible for change. We can conclude that change in methodology of creating architectural space should vitally include:

1. possibility of simultaneously working on a number of different uncorrelated low-key projects at the same time, dedicated to smaller design teams,

2. shorter periods for deliverables (both in terms of finished design, as well as its individual elements or phases),

3. more opportunities to return to an earlier stage of design.

2. Methods—How to Change the Process of Creating Architectural Space?

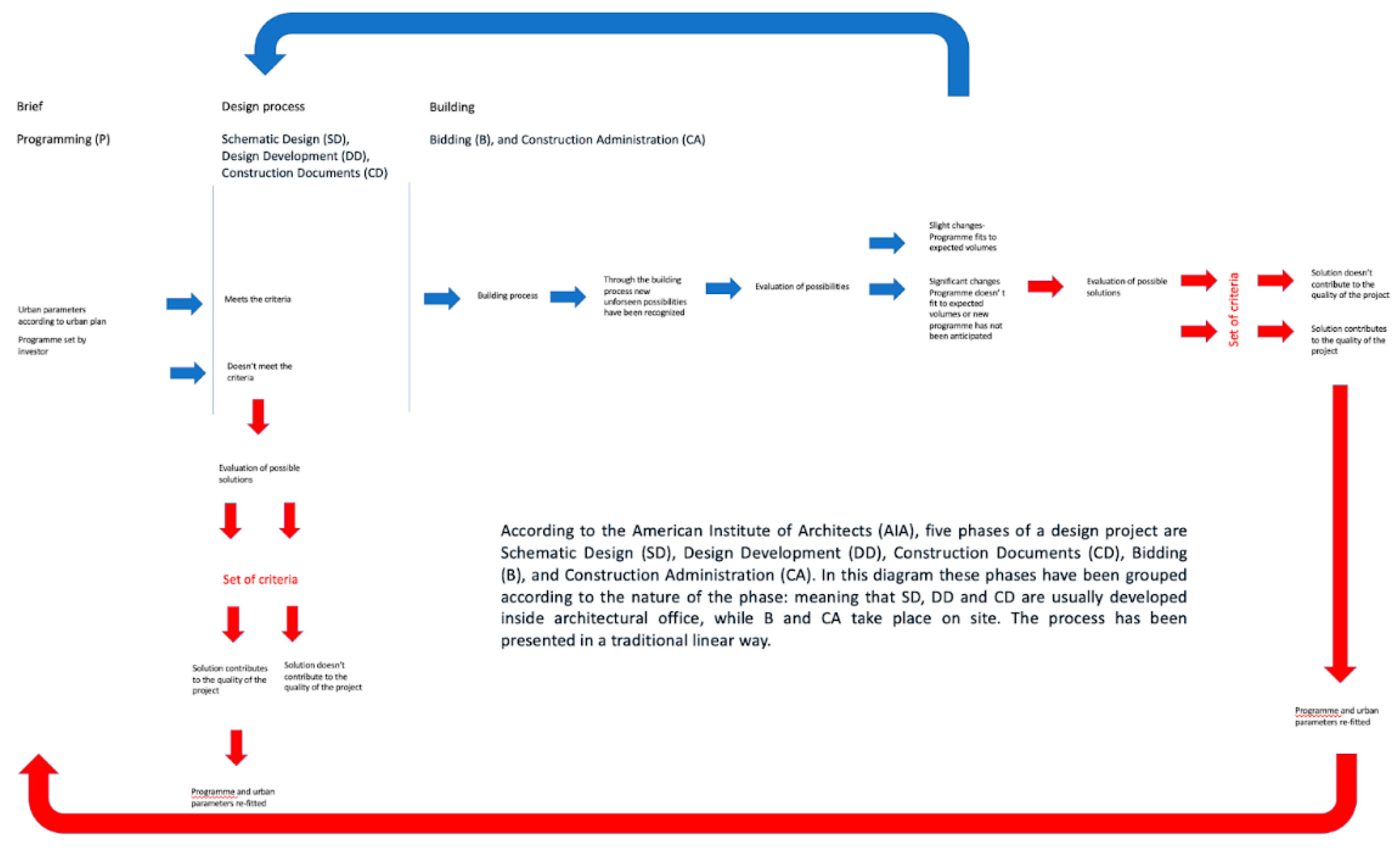

As stated before, in the past decades software development had a decisive influence on the process of architectural design, even leaning towards customizing design decisions towards the possibilities that the software offers. This technological development has become deeply incorporated in all phases of designing and building spaces. Nevertheless, the only area of architecture that has not been changed by this development is the design methodology itself, especially when viewed externally. Deeply linear and consecutive in its nature (

Figure 1), the architectural design process has changed very little since the invention of perspective drawing [

13], even though specific analytical research strategies and the development of a methodological framework for their application are central problems in the contemporary field of architectural research, education, and practice [

14].

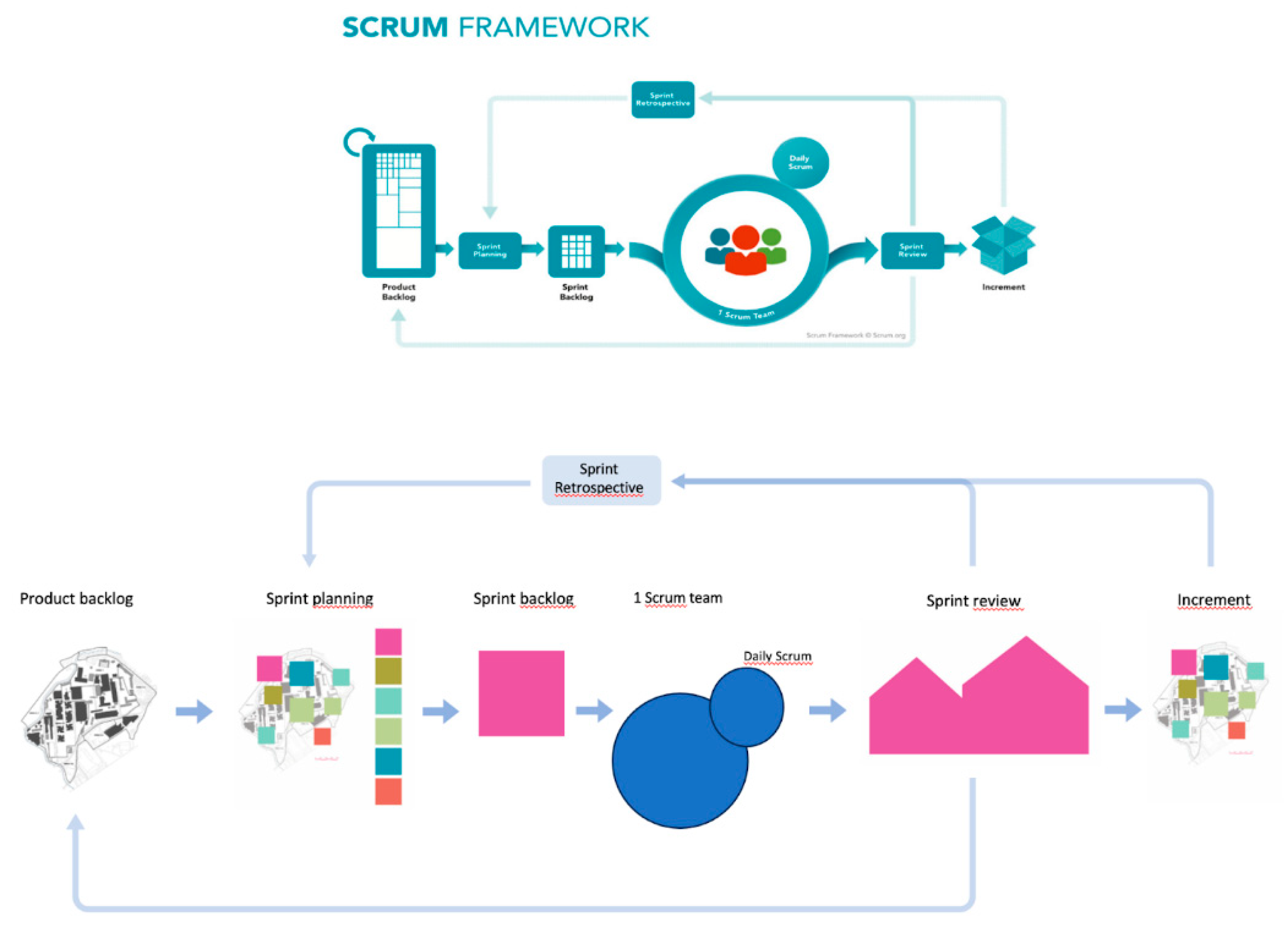

There are many parameters that restrict the process of architectural design, some of them being: existing urban plans and regulations, urban politics, societal and environmental challenges. Very important parameters for the process itself are also timeframes and costs that apply to executing the process (workforce, first of all). In a situation where more low-key projects are added to the design studio curricula, this load becomes even greater. When these requirements are being placed in order to be compared, we can easily find similarities regarding requests with the principles of Agile manifesto and Scrum methodology. It is also interesting to note that [

15] agile software development has been heavily influenced by works of Christopher Alexander, who was a very important figure in the fields of architecture and design theory.

As we can see from

Table 1, besides deadlines and cost being common denominators for a large set of processes including both software and architectural design, there are also other aspects of why it makes sense to look for alternative methodology in software. For example, it implies a significantly larger number of projects than in other industries and a greater willingness to experiment because failure costs less and has no lasting consequences. Both architecture and software can be characterized by a relatively large percentage of results (designs or software) that did not meet expectations, meaning that they were never put to practice. Another common thing for both disciplines is an idea of forming a list of requirements (in architecture called a programme or a brief, in scrum methodology called product backlog), as well as a strong emphasis on precise formulation of the problem and on the need to refine the formulation again during the design process. Of no less importance is the fact that architectural design is mostly realized in teams of authors, sometimes transdisciplinary in its nature, that Agile or Scrum (as an applied version of Agile Manifesto) support.

Therefore, it is possible to expect that application of Agile Manifesto in architectural design methodology might prove to be successful, which will be presented in the next chapter. That cross-disciplinary methodology, with analysis of advantages and disadvantages (possibilities and dangers of applying Scrum or some other similar agile methodology in architectural design) is the main novelty in this research.

It is also important to note that the presented approach differs from Agile Urbanism Blueprint or AUB [

6] in the sense that methodology presented in this paper is concentrated on architectural design methodology and practice itself. Nevertheless, these two methodologies can be compatible. Finally, it is important to note that the presented approach can be included in the group of concepts promoting the idea of open-source architecture, in the broader context [

17].

3. Application of Agile Manifesto on Architectural Competition for the Urban Renewal and Rehabilitation of the Spatial Cultural-Historical Unit “Military-Technical Institute in Kragujevac”

Traditionally the designing of an architectural object is conducted as a linear process. Tasks defined by brief are being resolved through clearly defined and predetermined intervals and since it is not usual to measure the progress in a sense of working parts some of them stay partially resolved or completely unresolved.

This is especially noticeable in the case of an architectural/urban competition. Rigid and unchanging list of requirements, short deadlines, a larger number of team members often lead to the differentiation of the process in terms of the distribution of spatial and temporal patterns in the work team. That differentiation and linearity of design process as consequence sometimes has non-effective and very slow changes to the design, and often produces solutions that do not provide an answer to a series of qualitative and quantitative values. In that sense, the architectural competition is the ideal ground for examining new methodologies in architectural practice.

Here we will consider that architectural design is a type of activity in which the main result is the production of space and is characterized by the simultaneous development and evolution of the problem and its solution. An adaptable methodological framework, where a problem is created and developed while simultaneously looking for ideas for its solution, should lead us from an unchanging framework of solutions to unforeseen connections and solutions that are in accordance with social changes and architecture as a dynamic discipline that reacts and responds to such an environment. Framework defined like that allows us to formulate tasks that connect seemingly distant and incompatible topics and spatial levels, with the aim of better understanding the process of creating a certain spatial structure, but also constantly re-examining our own ideas.

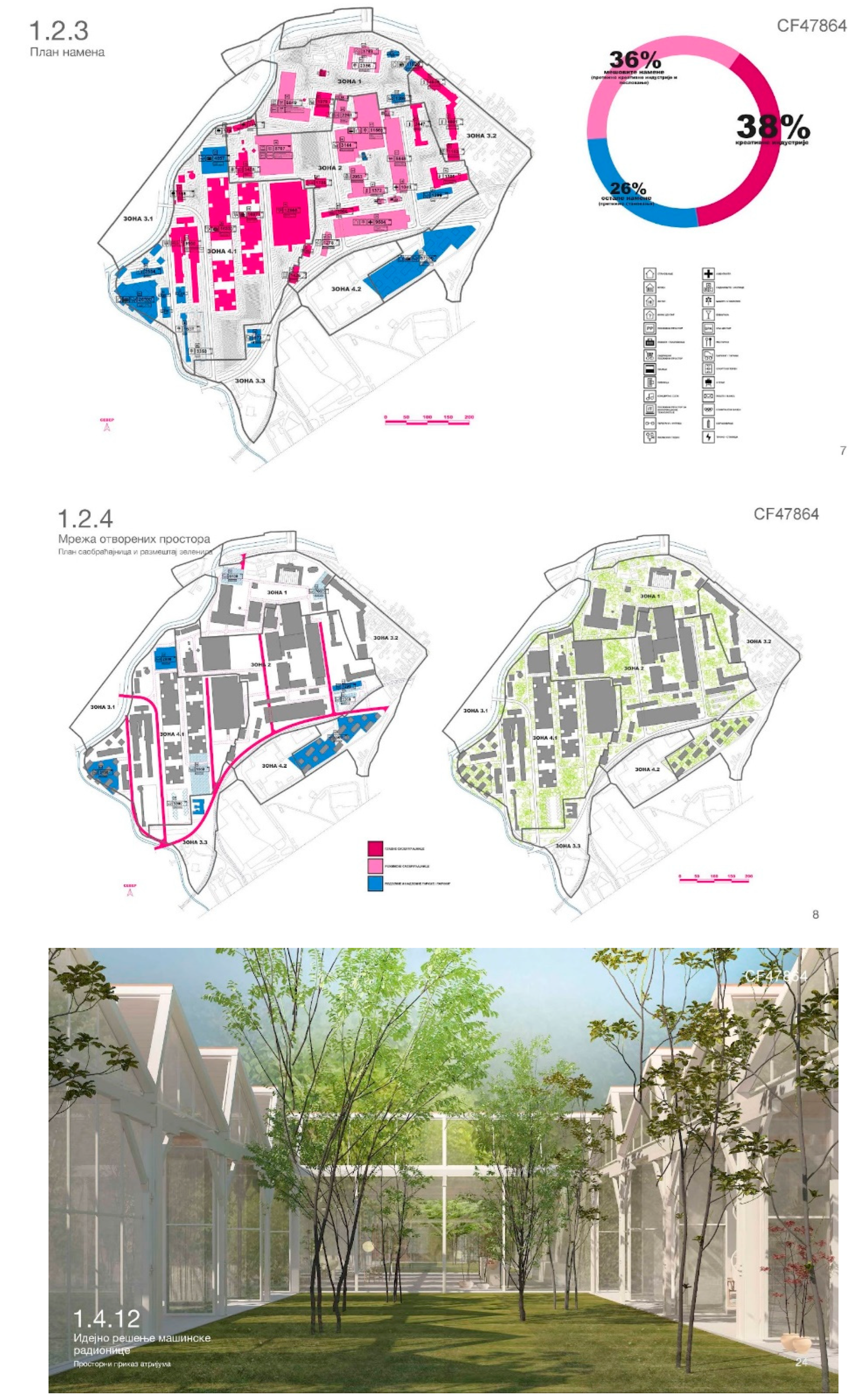

This point of view on architectural design, shaped according to Agile Manifesto and Scrum Framework (that come from software development instrumentaria), have been tested on larger scale architectural competitions in a team of 15 members. Architectural competition for urban renewal and rehabilitation of the spatial cultural and historical unit “Military-Technical Institute in Kragujevac” (launched in the year 2022) was chosen according to the following criteria:

size of competition area,

presence of cultural heritage on site,

strong requirements for both cultural heritage and environment protection,

great variety of programs defined by competition brief, ranging from housing to commercial use with emphasis on programs connected to creative industries and IT sector,

different private and public stakeholders.

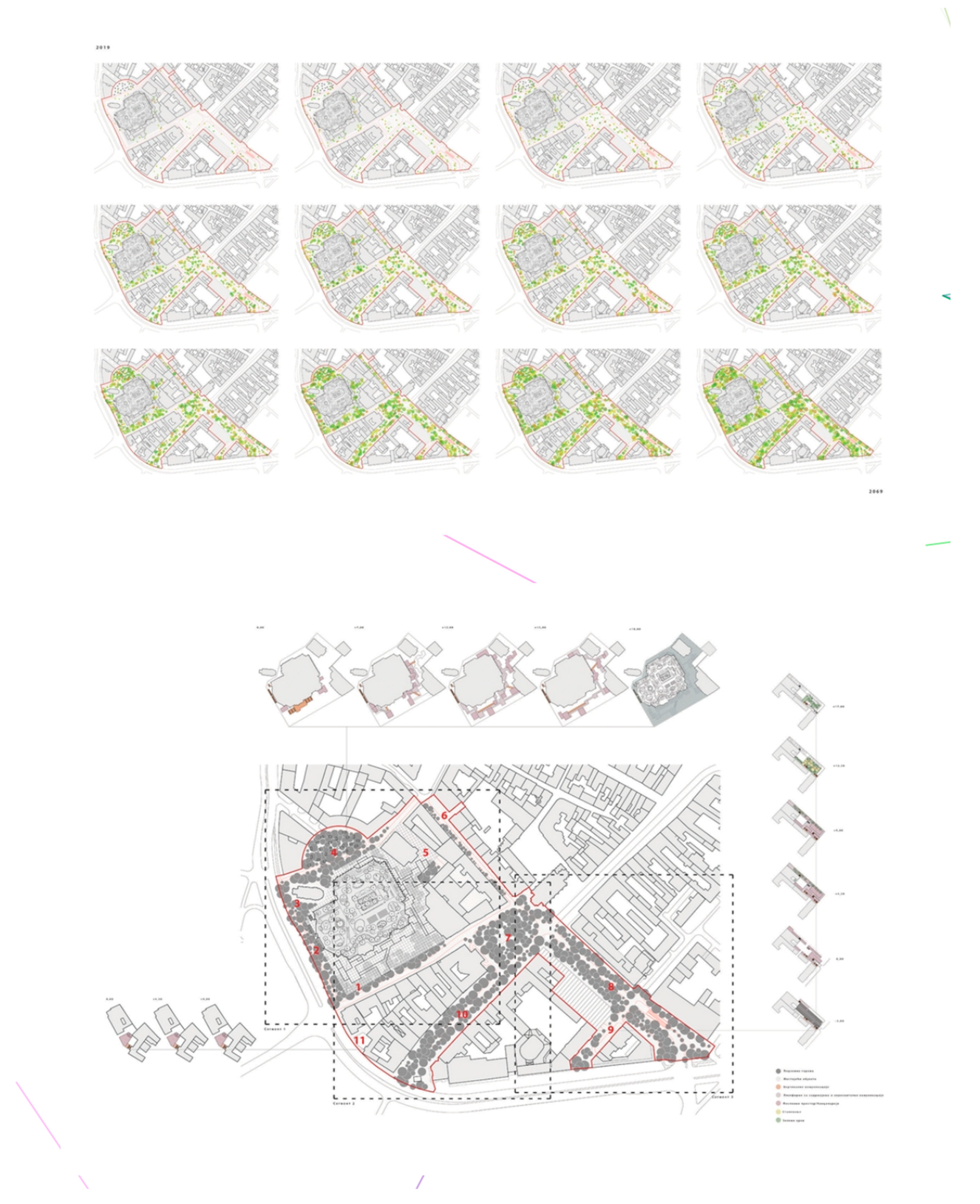

Applicability of Agile/Scrum was further enhanced by the fact that the architectural team that was applying for the competition was constituted of 20 members, who have already tested a similar approach on the architectural competition for the Public Spaces Design in the Centre of Novi Sad in the year 2018 (

Figure 2).

Kabinet505 (

http://kabinet505.ftn.uns.ac.rs/) is a group of professionals from the fields of architecture, design, visual arts, computing and automation. The group engages in transdisciplinary architectural research formalized in the form of strategies and objects largely based on the accelerated development of digital technologies and the ways in which they can be implemented in numerous spheres of human activity, including architecture and design.

Different skills and professional background, but common interests and previous experiences in team dynamics, helped not only to facilitate the implementation of specific framework, but also to partially reduce the obstacles of nonexistent feedback of all stakeholders caused by anonymity of competition entries defined by rules of competition.

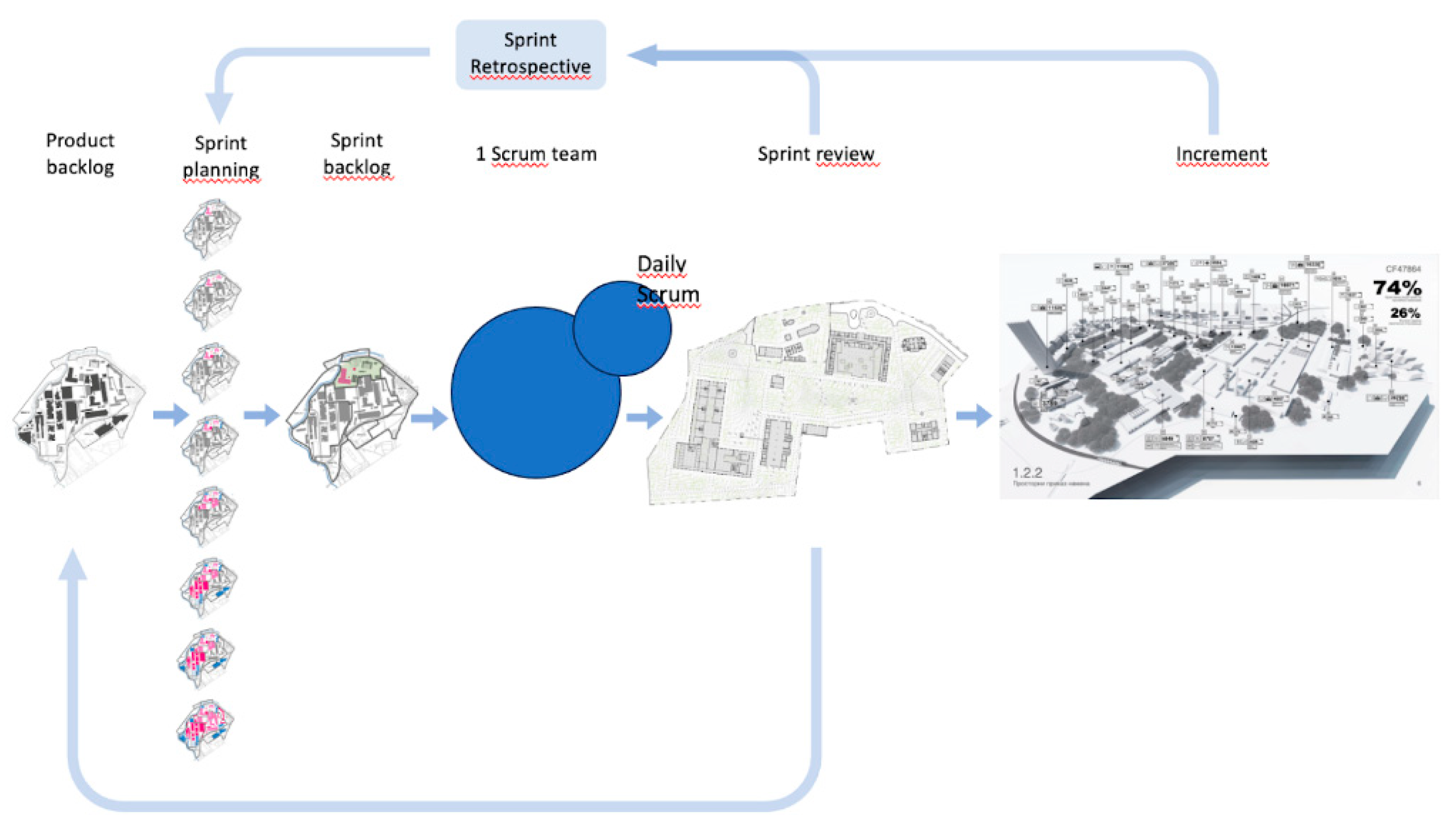

The Scrum framework was implemented as follows:

Competition tasks and eligibility criteria defined by brief were used as the starting point of defining product backlog of competition entry, as was overall concept defined through keywords based on priorities and sketches of main motifs of the overall design (

Figure 3);

Since competition tasks were different in sense of scale, level of elaboration in detail and type of design, Scrum planning and defining Scrum teams were crucial in further development of design,

Scrum teams were formed based on zones defined by competition tasks and milestones set by brief and conceptual ideas of the team forming the project network of teams;

Network was consisted of Scrum teams, which were consisted of two to three members, all together forming 8 teams working simultaneously on different sprints;

Each Scrum team had to address all aspects of the assigned task, meaning: 3D modeling and animation of existing area and proposed design; reconstruction and protection of designated heritage buildings and areas; distribution of programs and typology of buildings; “business model” of proposed design;

The frequency of sprint previews changed during the development of the project as follows:

In the first phase of working on the project, all Scrum teams had a daily sprint review to set specific goals and increments that relate to future design proposal (

Figure 4);

In the second phase, emphasis was shifted from daily to weekly sprint reviews, considering the fact that the level of detail in developing an architectural project becomes more complicated with the progress of the project itself (

Figure 5).

Further comments on the topic of application of agile methodology in architectural design process will be further discussed in the following chapter.

4. Discussion of the Results—Design Strategy and Design Tactics

In a heterogeneous environment with many variables, as it is in the case of the Architectural Competition for Urban Renewal and Rehabilitation of Spatial Cultural-Historical Unit “Military-Technical Institute in Kragujevac”, a linear and unchanging strategy does not leave the possibility of feedback and creating new connections and solutions. The methodology established in this way leads to isolation of certain design process phases, and as such cannot offer solutions that provide answers to changes in input data. A strategy based on such a common “prescribed” process creates ill-defined tasks whose solutions are often arbitrary and most often appear as an “in case” response to the problem. The unchanging path of problem solving based on a clear but rigid top-down principle often leaves several insufficiently clarified or unexplained parts that ultimately significantly affect the value of the solution, including its exploitation.

On the other hand, the proposed Agile/Scrum method offers a framework in which the work on finding solutions is based on tactics where individuals or teams not only offer an answer to a given problem, but create an environment in which it is easier to provide just-in-time answers to the requests. This is achieved through constant communication with all stakeholders in the design process. In this way, the obtained solutions do not solely represent the result of strategic rationalization and just-in-case responses to threats, but solutions that are the product of negotiations and practice of all interest groups, and therefore, adapted to different situations, functions, and problem tasks.

The case of the Architectural Competition for Urban Renewal and Rehabilitation of Spatial Cultural-Historical Unit “Military-Technical Institute in Kragujevac”, and the application of Agile/Scrum methodology can be indicated in several points that resulted in a significant change in the design process itself:

- -

Competition tasks and eligibility criteria defined by brief were different in sense of scale, detail requirement and type of design product, which implied several independent, parallel lines in the design process. The danger of creating solutions that remain insufficiently connected and uncoordinated in such an environment is precisely avoided by using the Agile/Scrum framework. The formation of individual Scrum teams with clear sprint backlogs provided the necessary connections and bridges between the different phases/lines defined by the competition.

- -

Individual teams that were in charge of specific topics such as 3D modeling and animation of existing areas and proposed design, reconstruction and protection of designated heritage buildings and areas, distribution of programs and typology of buildings, and the “business model” of the proposed design, were all better involved in the design process. Usually, teams with specific tasks appear as actors only at certain time intervals during the design process and are often faced with the fact that the inputs they receive are either insufficient and not fully defined, or otherwise unchangeable in the case of the final stages of design. The inclusion of the mentioned teams in the Scrum network enabled not only the fact that the data they receive is updated, but also created the possibility where they actively participate in all aspects of the design process (through the sprint review and sprint retrospective), which enabled better, higher quality and more harmonized individual solutions.

- -

Groups of Scrum teams that worked within the same or surrounding zones of the competition area were able to receive timely data on changes in all phases of the project through Scrum reviews within individual teams or groups of teams, but also to actively participate in the improvement of each phase. Team coordination and synchronization was done once at the end of each sprint, by means of face to face meetings between team leads.

- -

The environment created through the Agile/Scrum framework not only ensured the active participation of all team members during the entire development of the project, but also offered a solution in its entirety, both in terms of satisfying the set requirements, and in the presentation of the solution. It also offered a solution without blind spots, which is a rare case scenario in this type of architectural projects, and generally speaking, a huge problem of architectural practice.

6. Conclusions and Further Research

As discussed previously, the traditional process of architectural design is deeply linear in its nature, which leads to frequent misunderstandings and blind spots in between parties involved. This notion becomes even more emphasized when short deadlines are involved, as is always the case when any type of global or regional disruption takes place. The type of question that this research is trying to answer is what kind of sustainable methodology could be applied to the architectural design process itself? Sustainability here has been treated in the widest possible context, meaning that it is very important to use available resources wisely, with special attention to human resources and time available for a project. The methodology that is shown in this research is assisted with frequent communication between Scrum team members, as well as in between Scrum teams and other stakeholders, thus being participatory in its nature.

When we think of technological improvement in the context of architectural design, we usually think of software application, where software is a finalized product. Technology that has been applied here comes from one of the most propulsive spheres of activity in contemporary society - production of software, and in order to obtain optimal results, it is oriented towards the process itself. In this research, we have applied the technology of how software is actually produced, or so to speak - the method of software production. It is important to state that this does not limit the use of advanced technologies as design tools during the process organized according to the Agile principles.

Research shown, especially through the case study discussed in the paper, has led to a belief that this increased communication and loop organization of the process itself leads to final design solutions that meet a wider spectrum of set criteria, and therefore, a greater degree of agreement among all participants or stakeholders. This “trial and error approach” that is manifested in constant presentations of increments is a method to further foster persuasiveness of architectural argument, being constantly refined during the process itself.

Nevertheless, a few notes should be taken into consideration when Agile or Scrum frameworks are applied on architectural and urban design. First of all, this type of working environment is convenient when a relatively large team is involved in the activity of producing space, in order to be able to divide the team in smaller units with specialized tasks. The other option, that is very important for the future of architecture as a discipline, is to have a larger number of relatively small projects (single family houses, for example), that are set to demonstrate shared values amongst themselves (concepts or ideas of organizing space etc). In that case, Agile or Scrum could be the method to optimize common practices in architectural design studios. Also, this research was conducted in an environment of architectural competition, meaning that stages of Brief or Programming (P), as well as Building (B, CA), were not in focus (

Figure 1). If stages that are necessary to formulate the program or a brief were to be taken into consideration (urban plan parameters, for example), or demand for enhanced communication with the city authorities during the design process, even if the building itself was addressed - a significant change in practices of urban planning and legal regulations regarding building permits would have to take place.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: JAJ, MR; IM.; methodology, JAJ; MR; IM; ET; DE.; validation, MR, ET. ; formal analysis, JAJ, MR, IM.; investigation, JAJ, MR; IM; ET; DE; resources JAJ; IM; DE.; data curation, MR, ET.; writing—original draft preparation, JAJ; MR; IM; ET; DE.; writing—review and editing, JAJ; MR; IM; ET; DE.; visualization, JAJ; DE.; supervision, MR; ET.; project administration, JAJ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This research was done within the scope of the project “Innovative approaches and advancement of processes and methods in higher education in Architecture, Urbanism and Scene Design” at Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi Sad.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sylvia: L. ; Kissing Architecture, 28552nd ed.; Publisher: Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 2011.

- Grosz, E. ;A., Architecture from the outside: essays on virtual and real space. 2001: MIT Press.

- Cook, P., R. Llewellyn-Jones, and K. Norment, New spirit in architecture. 1991: Rizzoli.

- Cuff, D. ; Digital pedagogy: an essay. Archit Rec. 2001;(9):200-4, 206. PMID: 11573252.

- Robertson, B.F, Radcliffe, D.F, Impact of CAD tools on creative problem solving in engineering design. Computer-Aided Design, 2009. 41(3): p. 136-146.

- The Agile Urbanism Manifesto: A citizen-led blueprint for smart cities, smart communities, and smart democracy. Available online: https://grantmunro.com/the-agile-urbanism-manifesto-5f8c9f418a7f#_ENREF_11 (accessed on 14.06.2023).

- Alastair, F. ; A History of English Literature, Publisher: Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA (1989) ISBN 0-674-39664-2, p.372.

- Self-Design and Aesthetic Responsibility. Available online: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/07/61386/self-design-and-aesthetic-responsibility/ (accessed on 14.06.2023).

- Dezeen: “We need architects to work on ordinary briefs, for ordinary people”. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2017/12/04/finn-williams-opinion-public-practice-opportunities-architects-ordinary-briefs-ordinary-people/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20RIBA%2C%20only,to%20design%20a%20single%20museum.

- (accessed on 14.06.2023).

- Harvard design magazine: The Next Big Architectural Project.

- Available on: https://www.harvarddesignmagazine.org/issues/12/seventy-five-percent (accessed on 14.06.2023).

- Yang, D. ; Di Stefano, D., Turrin, M., Sariyildiz, S., & Sun, Y. (2020). Dynamic and interactive re-formulation of multi-objective optimization problems for conceptual architectural design exploration. Automation in Construction, 118, [103251]. [CrossRef]

- Herbert, A. S. ; The structure of ill structured problems, Artificial Intelligence, Volume 4, Issues 3–4, 1973, Pages 181-201, ISSN 0004-3702. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gómez, A. ; A.P. Gómez, and L. Pelletier, Architectural representation and the perspective hinge. 2000, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

- Milovanović, A. ; Uloga metodologije arhitektonskog programiranja u procesu projektovanja morfologije prostora: Primer trećeg Beograda, PhD dissertation, Belgrade, 2022.

- Cunningham, W; Michael W. (2013). “Wiki as pattern language”. Proceedings of the 20th Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs, October 23–26, 2013, Monticello, Illinois. PLoP ‘13. Corryton, TN: The Hillside Group. pp. 32:1–32:14. ISBN 9781941652008.

- Manifesto for Agile Software Development. Available on: http://agilemanifesto.org/ (accessed on 14.06.2023).

- Ratti C.; Claudel M.; Open-source Architecture; Publisher: WW Norton, 2015, ISBN 0500343063, 9780500343067.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).