Submitted:

01 June 2025

Posted:

02 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Questions

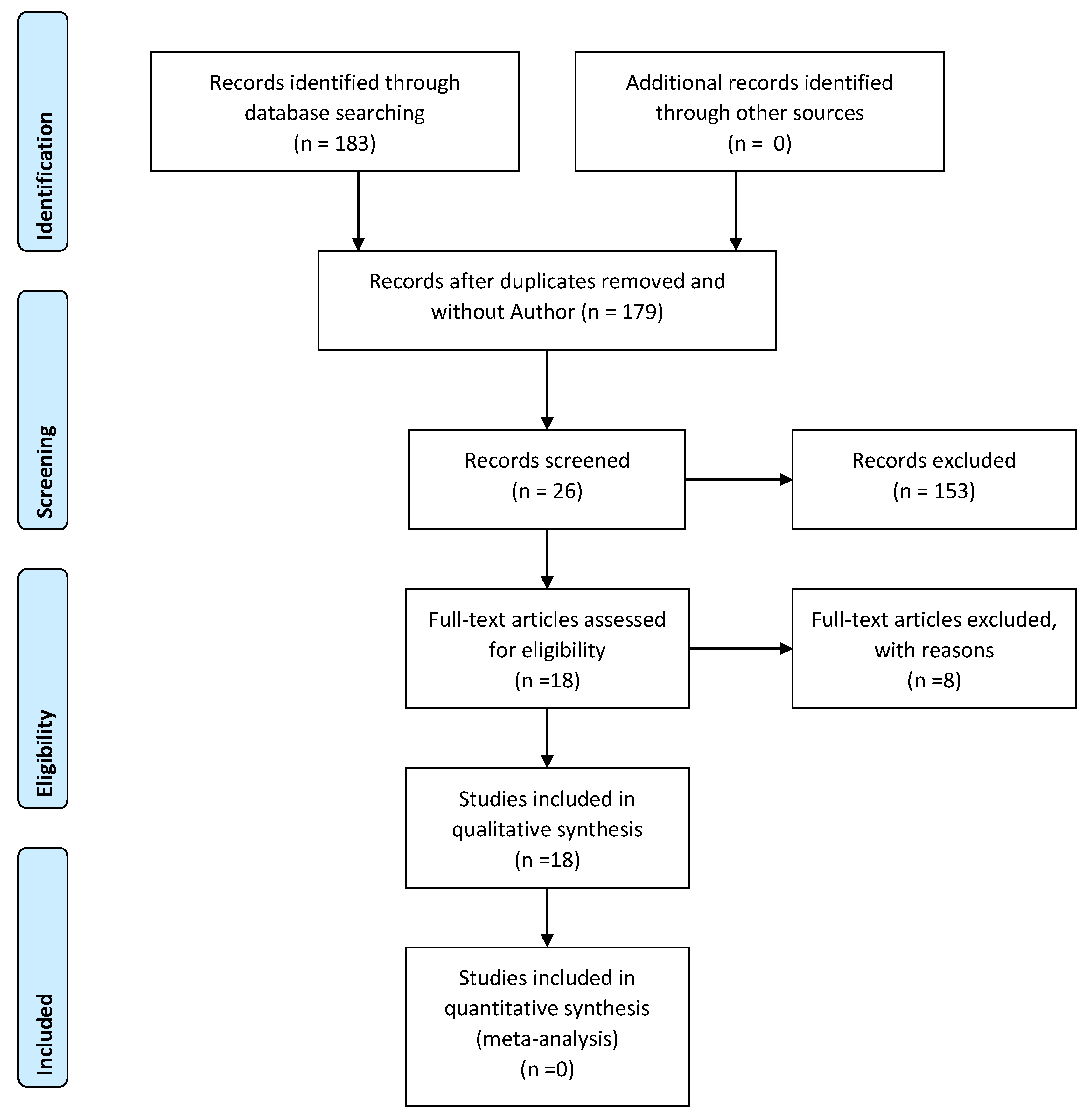

3.2. Search Strategy

3.3. Inclusion Criteria

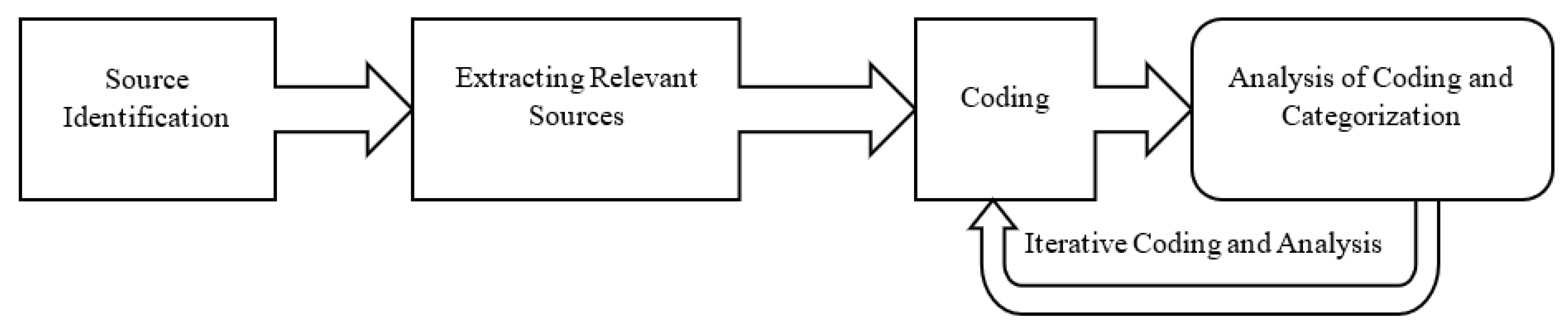

3.4. Research Processes

4. Analysis

4.1. Agile Scrum Challenges Themes and Subthemes

4.1.1. Challenges of using Agile Scrum/Results

4.1.1.1. Dependency Issues

4.1.1.2. Agile Difficult to Implement

4.1.1.3. Multi-team Environment Challenges

4.1.1.4. Challenges of Requirement Engineering

4.1.1.5. Knowledge Issues

4.1.1.6. Resistance to Change

4.1.1.7. Organizational Structures and Boundaries

4.1.1.8. Quality Assurance Challenges

5. Discussions

5.1. Limitations of the research

6. Conclusions

7. Recommendations for future Studies

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Challenge Type | Primary Sources | Case Organization | #of cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependency Issues (12)-67% | |||

| General Lack of Task Dependency Awareness | P01,P02,P04,P07,P08,P09,P10,P15 | C01,C02,C04,C07,C08,C09,C10,C15 | 8(44%) |

| Expertise dependency | P08,P09,P11,P12 | C08,C09,C11,C12 | 4(22%) |

| Business process and Historical dependency | P08,P11 | C08,C11 | 2(11%) |

| Entity Dependency | P08,P18 | C08,C18 | 2(11%) |

| Technical Dependency | P08,P14,P15,P18 | C08,C14,C15,C18 | 4(22%) |

| Social Loafing | P04,P10 | C04,C10 | 2(11%) |

| Agile Difficulty to implement (16)-89% | |||

| Old Software Culture to move to Agile and Lean | P05,P06,P10,P15,P17 | C05,C06,C10,C17,C15 | 5(28%) |

| Too many and Long Scrum Meetings | P02,P04,P07,P13,P17 | C02,C07,C04,C17,C13 | 5(28%) |

| Improper implementation of Agile Processes | P07,P17 | C07,C17 | 2(11%) |

| Lack of guidance from Literature | P10,P18 | C10,C18 | 2(11%) |

| ASD (Agile Software Development) doesn't encourage reuse | P07,P11,P14 | C07,C11,C14 | 3(17%) |

| Agile Projects' Contract and Risk Management Issues | P12,P14,P15,P17 | C12,C14,C15,C17 | 4(22%) |

| project size | P01,P02,P03,P04,P09 | C01,C02,C03,C04,C09 | 5(28%) |

| Agile practices adoption degree (Lacking Agile mindset) | P01,P03,P06,P10,P12,P13 | C01,C03,C06,C10,C12,C13 | 6(33%) |

| challenges in portfolio management | P02,P06,P07,P09,P14 | C02,C06,C07,C09,C14 | 5(28%) |

| Over-optimism | P10,P17 | C10,C17 | 2(11%) |

| Multi-team Environment Challenges (15)-83% | |||

| Inter-team coordination Challenges | P01,P02,P04,P05,P06,P07,P08,P09,P10,P13,P14,P15,P18 | C01,C02,C04,C05,C06,C07,C08,C09,C10,C13,C14,C15,C18 | 13(72%) |

| Inter-team Communication Challenges | P01,P02,P03,P04,P05,P06,P07,P08,P09,P12,P13,P14,P15,P18 | C01,C02,C03,C04,C05,C06,C07,C08,C09,C12,C13,C14,C15,C18 | 14(78%) |

| Alignment Issues between teams and other stakeholders | P01,P02,P03,P09,P10,P15 | C01,C02,C03,C09,C10,C15 | 6(33%) |

| Geographic Distribution Challenges | P04,P06,P07,P09,P10,P12,P13,P15,P18 | C04,C06,C07,C09,C10,C12,C13,C15,C18 | 9(50%) |

| unpredictability of delivery to commitment | P02,P04,P09,P18 | C02,C04,C09,C18 | 4(22%) |

| Group Maturity Issues | P06,P08,P09 | C06,C08,C09 | 3(17%) |

| Visibility of Product Backlog and Operations Issues | P06,P07,P10 | C06,C07,C10 | 3(17%) |

| Collaboration Challenges | P03,P04,P09,P15 | C03,C04,C09,C15 | 4(22%) |

| Challenges of Requirement Engineering (14)-78% | |||

| Requirements volatility and interdependencies | P01,P02,P08,P09,P10 | C01,C02,C08,C09,C10 | 5(28%) |

| Lack of Software Architecture Solutions Description/Documentation | P01,P02,P07,P08,P09,P10,P11,P13,P14 | C01,C02,C07,C08,C09,C10,C11,C13,C14 | 9(50%) |

| Misalignment of Specification | P01,P04,P08 | C01,C04,C08 | 3(17%) |

| Misalignment of Backlog Prioritization | P01,P02,P08,P09,P10,P14,P18,P15 | C01,C02,C08,C09,C10,C14,C18,C15 | 8(44%) |

| Misalignment of Effort Estimation | P01,P04,P07,P10,P12,P15 | C01,C04,C07,C10,C12,C15 | 6(33%) |

| misaligned planning | P01,P02,P09,P10 | C01,C02,C09,C10 | 4(22%) |

| Unclear Decision Among Team Members | P04,P06 | C04,C06 | 2(11%) |

| Misalignment of Task Allocation | P01,P04,P08 | C01,C04,C08 | 3(17%) |

| Customer Involvement Issues | P01,P02,P04,P08,P09,P10,P12,P15 | C01,C02,C04,C08,C09,C10,C12,C15 | 8(44%) |

| Requirements Management in Waterfall Mode | P10,P15 | C10,C15 | 2(11%) |

| Issues of release planning | P02,P09,P10,P15 | C02,C09,C10,C15 | 4(22%) |

| Knowledge Issues (13)-72% | |||

| Ineffective Leadership | P01,P02,P03,P05,P08 | C01,C02,C03,C05,C08 | 5(28%) |

| Tacit knowledge management challenges | P02,P06,P08,P09,P11,P12,P13 | C02,C06,C08,C09,C11,C12,C13 | 7(39%) |

| End-to-end implementation knowledge Issues | P01,P02,P08,P10,P12 | C01,C02,C08,C10,C12 | 5(28%) |

| Fragmented view of the system | P02,P05,P09,P10,P14,P18 | C02,C05,C09,C10,C14,C18 | 6(33%) |

| Proof-of-concepts with core technology | P02,P14 | C02,C14 | 2(11%) |

| Resistance to Change (3)-17% | |||

| Skepticism towards the new Software Method | P09,P17 | C09,C17 | 2(11%) |

| Management resistance to Change | P15,P17 | C15,C17 | 2(11%) |

| Organizational Structure and Boundaries (4)-22% | |||

| Traditional IT Organizational Structure | P12,P15 | C12,C15 | 2(11%) |

| Superfluous Old Organizational Processes | P13,P17 | C13,C17 | 2(11%) |

| Quality Assurance Challenges (4)-22% | |||

| Compromised Quality with the Smaller Releases | P04,P09,P10,P15 | C04,C09,C10,C15 | 4(22%) |

| Lack of Automated Testing | P04,P09 | C04,C09 | 2(11%) |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1

| Study Type (C-case study, ER-Experience Report, Empirical Study-ES) | Paper (s) | Company | Business area | Software Organization Size | Operating Locations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C01 | P01 | Anonymous | Enterprise Software Solutions | 13 dev teams (Each consists of 6 to 16 developers) and total of over 140 Employees | China, India and Germany |

| C02 | P02 | Norwegian Public Service Pension Fund (the “Pension Fund”) Developed by the Pension Fund internal development unit, and Accenture and Steria Consulting Firms |

Automation of Public Service Pension Fund | 12 collocated development teams with more 175 people involved. The development ran for four years. | Norway |

| C03 (ES) | P03 | Anonymous | Pakistan | ||

| C04 (ES) | P04 | Anonymous | Researchers from Pakistan | ||

| C05 (ER) | P05 | Comptel | Telecommunications | 750+ employees | Finland |

| C06 (ER) | P06 | Anonymous | Different places | ||

| C07 (ES) | P07 | Anonymous | Companies involved in the study were based in U.K. and India | ||

| C08 | P08 | Anonymous | Government, Commercial service provider, and Commercial software development firm | Three companies with 2000, 200, and 20 employees, respectively | New Zealand |

| C09 | P09 | Anonymous | Retail Banking, Telecommunications, Insurance | 150 Scrum Teams, 34 Scrum Teams, and 5 Scrum Teams, respectively. Each of this case organizations have from 250 to 1500 IT development employees. | Netherlands |

| C10 | P10 | F-Secure | PC, Mobile and Data Security | More than 800 Employees | Finland (Development teams from Poland and Malaysia were involved) |

| C11 (ES) | P11 | Anonymous | |||

| C12 | P12 | Anonymous | Healthcare provider in the USA | Six Agile Scrum Teams (Each contains six to seven developers) | The Development was carried out in three locations (U.S.A. (Owner of the Project), Chennai and Bangalore) |

| C13 | P13 | Ericsson | Telecommunication | 400 persons in 40 Scrum teams at three sites | Finland, Hungary and the US |

| C14 | P14 | Anonymous | Financial | Very big Financial IT Systems | Not mentioned |

| C15 | P15 | Anonymous | Financial and Manufacturing | 26,000 and more than 100,000 employees, respectively | Netherlands |

| C16 | P16 | Anonymous | Rapid application development and production tool | More than 20,000 employees and has clients in 70 countries | Not mentioned |

| C17 (ER) | P17 | Anonymous | Telecommunications | More 200 | U.A.E |

| C18 | P18 | Anonymous | Media Organization | Not mentioned | Not mentioned |

Appendix C

Appendix C.1

| Case | Study Focus | Key Results the Study Focuses On | Subject |

|---|---|---|---|

| C01 | Coordination Challenges in Large-Scale Software Development | Planning misalignment leads to lack of dependency awareness, which ultimately leads to coordination challenges | 23 semi-structured interviews with key informants and analysis of documents. |

| C02 | Adoption of Agile Scrum in Large-Scale Software Development | customer involvement, software architecture, and inter-team coordination were identified as key challenges |

group interviews with 24 participants and documents |

| ES03 | Social Success Factors Affecting Implementation of Agile Software Development Methodologies | visionary leadership, degree or level of Agile software practices, congruence value, etc. were identified as significant contributors to the success of a project | Interviews with 271 software professionals representing 28 companies |

| ES04 | Preference of Using Agile Scrum with Large Team size | Agile scrum is preferred to be used when the team size is less than 25 | Survey data was collected from several software houses in a developing country |

| ER05 | Adoption of SAFe (Scaled Agile Framework) in two business lines of Comptel | Key areas for successful adoption of the agile framework | Interviews with key informants |

| ES06 | Group development and group maturity when building agile teams | group developmental aspects is key factors to a successful agile transition | Ten semi-structured Interviews with individuals from four companies and 66 Surveys from another four companies, a total of eight companies |

| ES07 | Identifying Agile Artefacts to enrich the traditional Agile Ceremonies | By way of Identifying Agile Artefacts additional Agile Ceremonies were identified | 46 practitioner interviews, documentary sources and observations, in nine international companies |

| C08 | Taxonomy of dependencies to apply appropriate coordination in Agile | Identified the key dependency taxonomy and Suitable Agile coordination | 11 interviews (project leader, developer, business analyst, domain expert, or tester)-Each Interview lasted 40 to 90 min following a semi-structured interview schedule. |

| C09 | Identify the collaboration related issues in chains of Scrum teams | governance framework to manage chains of Scrum teams |

Three case studies (9, 6, 3 Product Owners, Line Managers and Scrum Masters were interviewed from each case, respectively). |

| C10 | Release Iteration Planning in Agile Development | Benefits and best practices of Release Iteration Planning in Agile | Two Case Studies (Interviews and Observation) |

| ES11 | Case Based Reasoning (CBR) in Agile Scrum Development | CBR to learn from past projects in Agile Scrum is useful | Experiment and survey (27 developers from two companies) |

| C12 | risk management in a large offshore-outsourced Agile Scrum software development | Risk identification and mitigation techniques in a large offshore-outsourced Agile Scrum Software Development | 1 Offshore Development Center Project Manger and 2 Scrum Masters) |

| C13 | Community of Practice (CoP) to help improve Agile Adoption | CoPs is supporting continuous organizational improvements | 52 semi-structured interviews on two sites |

| C14 | studying the adoption and architectural extensions of the Scum method in large Financial IT Systems |

Methods and Practices to adopt Agile Scrum in Financial IT Sector | 21 interviews, including 33 specialists from the case organization’s different areas and managerial levels (each interview lasted 1.5-2 hours) and workshops were organized |

| C15 | Challenges and Remedies of Coexistence of Plan-driven and Agile Methods | Suggested mitigation Strategies to coexist the two methodologies. | Interviews with 21 Agile Practitioners from two Large Enterprise Organizations (duration of Interview 1 to 1.5 hours) |

| C16 | onside customer involvement in Agile Scrum development | Scrum can be successfully used without intensive involvement of onsite customer | Interview, Observation, Survey, and Document analysis. |

| ER17 | Agile Scrum Adoption Strategy | Agile Scrum Adoption Failure, case study | Experience report on Agile Scrum Adoption |

| C18 | User Experience (UX) Design and Agile Method | cooperation between the Agile developers and UX designers was achieved through ongoing articulation work by the developers | Observation of and interview with 14 Agile Developers and 2 UX Designers |

Appendix D.

Appendix D1. List of References for the Review

- P01.

- Bick, S.; Spohrer, K.; Hoda, R.; Scheerer, A.; Heinzl, A. Coordination Challenges in Large-Scale Software Development: A Case Study of Planning Misalignment in Hybrid Settings. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 2018, 44, 932–950, doi:10.1109/TSE.2017.2730870.

- P02.

- Dingsøyr, T.; Moe, N.B.; Fægri, T.E.; Seim, E.A. Exploring Software Development at the Very Large-Scale: A Revelatory Case Study and Research Agenda for Agile Method Adaptation. Empir Softw Eng 2018, 23, 490–520, doi:10.1007/s10664-017-9524-2.

- P03.

- Riaz, M.N.; Mahboob, A.; Buriro, A. Social Success Factors Affecting Implementation of Agile Software Development Methodologies in Software Industry of Pakistan: An Empirical Study. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2018, 9, doi:10.14569/IJACSA.2018.090713.

- P04.

- Zia, A.; Arshad, W.; Mahmood, W. Preference in Using Agile Development with Larger Team Size. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2018, 9, doi:10.14569/IJACSA.2018.090716.

- P05.

- Ebert, C.; Paasivaara, M. Scaling Agile. IEEE Softw 2017, 34, 98–103, doi:10.1109/MS.2017.4121226.

- P06.

- Gren, L.; Torkar, R.; Feldt, R. Group Development and Group Maturity When Building Agile Teams: A Qualitative and Quantitative Investigation at Eight Large Companies. Journal of Systems and Software 2017, 124, 104–119, doi:10.1016/j.jss.2016.11.024.

- P07.

- Bass, J.M. Artefacts and Agile Method Tailoring in Large-Scale Offshore Software Development Programmes. Inf Softw Technol 2016, 75, 1–16, doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2016.03.001.

- P08.

- Strode, D.E. A Dependency Taxonomy for Agile Software Development Projects. Information Systems Frontiers 2016, 18, 23–46, doi:10.1007/s10796-015-9574-1.

- P09.

- Vlietland, J.; van Vliet, H. Towards a Governance Framework for Chains of Scrum Teams. Inf Softw Technol 2015, 57, 52–65, doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2014.08.008.

- P010.

- Heikkilä, V.T.; Paasivaara, M.; Rautiainen, K.; Lassenius, C.; Toivola, T.; Järvinen, J. Operational Release Planning in Large-Scale Scrum with Multiple Stakeholders – A Longitudinal Case Study at F-Secure Corporation. Inf Softw Technol 2015, 57, 116–140, doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2014.09.005.

- P011.

- Turani, A. APPLYING CASE BASED REASONING IN AGILE SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT. J Theor Appl Inf Technol 2015, 78.

- P012.

- Sundararajan, S.; Bhasi, M.; Vijayaraghavan, P.K. Case Study on Risk Management Practice in Large Offshore-outsourced Agile Software Projects. IET Software 2014, 8, 245–257, doi:10.1049/iet-sen.2013.0190.

- P013.

- Paasivaara, M.; Lassenius, C. Communities of Practice in a Large Distributed Agile Software Development Organization – Case Ericsson. Inf Softw Technol 2014, 56, 1556–1577, doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2014.06.008.

- P014.

- Hajjdiab, H.; Taleb, A.S.; Ali, J. An Industrial Case Study for Scrum Adoption. Journal of Software 2012, 7, 237–242, doi:10.4304/jsw.7.1.237-242.

- P015.

- Ihme, T. Scrum Adoption and Architectural Extensions in Developing New Service Applications of Large Financial IT Systems. Journal of the Brazilian Computer Society 2013, 19, 257–274, doi:10.1007/s13173-012-0096-0.

- P016.

- van Waardenburg, G.; van Vliet, H. When Agile Meets the Enterprise. Inf Softw Technol 2013, 55, 2154–2171, doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2013.07.012.

- P017.

- Inayat, I.; Noor, M.A.; Inayat, Z. Successful Product-Based Agile Software Development without Onsite Customer: An Industrial Case Study. International Journal of Software Engineering and Its Applications 2012, 6.

- P018.

- Ferreira, J.; Sharp, H.; Robinson, H. User Experience Design and Agile Development: Managing Cooperation through Articulation Work. Softw Pract Exp 2011, 41, 963–974, doi:10.1002/spe.1012.

References

- Schwaber, Ken. Agile Project Management with Scrum. In; Microsoft Press, 2004 ISBN 9780735619937.

- Schwaber, K.; Beedle, M. Agile Software Development with Scrum; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, 2002;

- Paasivaara, M. Adopting SAFe to Scale Agile in a Globally Distributed Organization. Proceedings - 2017 IEEE 12th International Conference on Global Software Engineering, ICGSE 2017 2017, 36–40. [CrossRef]

- Kasauli, R.; Knauss, E.; Kanagwa, B.; Balikuddembe, J.K.; Nilsson, A.; Calikli, G. Safety-Critical Systems and Agile Development: A Mapping Study. 2018 44th Euromicro Conference on Software Engineering and Advanced Applications (SEAA) 2018, 470–477. [CrossRef]

- Ebert, C.; Paasivaara, M. Scaling Agile. IEEE Softw 2017, 34, 98–103.

- Dikert, K.; Paasivaara, M.; Lassenius, C. Challenges and Success Factors for Large-Scale Agile Transformations: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Systems and Software 2016, 119, 87–108. [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Budgen, D., Brereton, P., Linkman, M.T.S., Mendes, M.J.E., Visaggio, G., Eds.; Version2.3.; Durham, UK, 2007;

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst Rev 2015, 4, 1. [CrossRef]

- Paasivaara, M.; Lassenius, C.; Heikkilä, V.T. Inter-Team Coordination in Large-Scale Globally Distributed Scrum. Proceedings of the ACM-IEEE international symposium on Empirical software engineering and measurement - ESEM ’12 2012, 235. [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.J. An Exploratory Study on Issues and Challenges of Agile Software Development with Scrum. All Graduate Theses and Dissertations 2010, 599.

- Beck, K.; Beedle, M.; Van Bennekum, A.; Cockburn, A.; Cunningham, W.; Fowler, M.; Grenning, J.; Highsmith, J.; Hunt, A.; Jeffries, R.; et al. Manifesto for Agile Software Development Available online: https://moodle2016-17.ua.es/moodle/pluginfile.php/80324/mod_resource/content/2/agile-manifesto.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Dingsøyr, T.; Moe, N.B.; Fægri, T.E.; Seim, E.A. Exploring Software Development at the Very Large-Scale: A Revelatory Case Study and Research Agenda for Agile Method Adaptation. Empir Softw Eng 2018, 23, 490–520. [CrossRef]

- Vlietland, J.; Van Vliet, H. Towards a Governance Framework for Chains of Scrum Teams. Inf Softw Technol 2015, 57, 52–65. [CrossRef]

- Moe, N.B.; Olsson, H.H.; Dingsøyr, T. Trends in Large-Scale Agile Development: A Summary of the 4th Workshop at XP2016. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Scientific Workshop Proceedings of XP2016 on - XP ’16 Workshops; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 2016; Vol. 1, pp. 1–4.

- Malone, T.W.; Crowston, K. The Interdisciplinary Study of Coordination. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 1994, 26, 87–119. [CrossRef]

- Bick, S.; Spohrer, K.; Hoda, R.; Scheerer, A.; Heinzl, A. Coordination Challenges in Large-Scale Software Development: A Case Study of Planning Misalignment in Hybrid Settings. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 2018, 44, 932–950. [CrossRef]

- Paasivaara, M.; Lassenius, C. Communities of Practice in a Large Distributed Agile Software Development Organization - Case Ericsson. Inf Softw Technol 2014, 56, 1556–1577. [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, J. Agile Can Scale: Inventing and Reinventing SCRUM in Five Companies. Cutter IT Journal 2001, 14, 5–11. [CrossRef]

| Facet | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Agile Method | Scrum OR Agile AND Scrum |

| Development Context | Large OR “Large Scale” OR “Large team” OR “Large Project” OR “Large Software” OR “Large Software Development” |

| Scrum Issues | challenges OR practices OR “success factors” OR application OR use |

| Facet | Relevant topics | Example of non-relevant topics |

|---|---|---|

| Agile Software Development | The Company is a software organization that employs Scrum Methodology | Agile Scrum manufacturing; Scrum in management boards Comparison |

| Large Scale | Scrum/Agile Scrum applied in large scale software development projects | Scaling up from small; a single agile team in a large setting |

| Context | Challenges, Practices, Success factors, Application and Use | comparison of methodologies; comparison of before and after |

| Source Type | Journal | Books, Book Series and Conference Proceedings |

| Year of Publication | 2011-2023 | Any publication out of this range |

| Publication Language | English | Publication language except English |

| Number of Citation | >=3 | <3 |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( scrum OR agile AND scrum ) AND ( large OR "Large Scale" OR "Large team" OR "Large Project" OR "Large Software" OR "Large Software Development" ) AND ( challenges OR practices OR "success factors" OR application OR use ) ) AND PUBYEAR > 2010 AND PUBYEAR < 2024 AND ( LIMIT-TO ( PUBSTAGE , "final" ) ) AND ( EXCLUDE ( PREFNAMEAUID , "Undefined" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE , "English" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE , "ar" ) ) |

| Context Code | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Business area | The business area in which the organization operates |

| Organization Size | Identifying the size of the organization whenever possible |

| Research Process | The employed research process in each primary study |

| Database | URL | Number of Matches |

|---|---|---|

| IEEExplore | http://ieeexplore.ieee.org | 5 |

| Scopus | http://www.scopus.com/home.url | 178 |

| Year | Frequency |

|---|---|

| 2018 | 4 |

| 2017 | 2 |

| 2016 | 2 |

| 2015 | 3 |

| 2014 | 2 |

| 2013 | 2 |

| 2012 | 2 |

| 2011 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).