Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

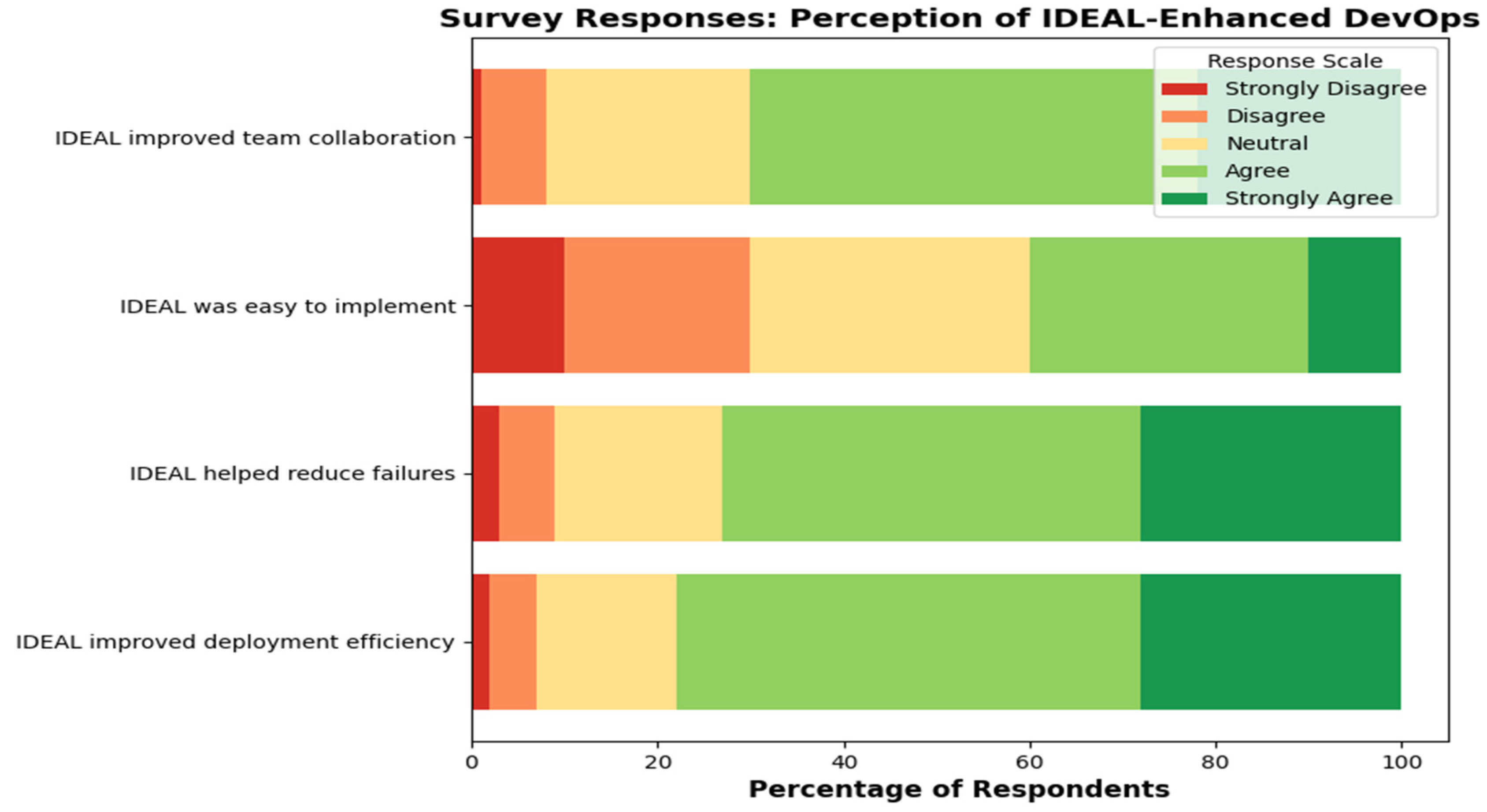

Recent advances in DevOps have dramatically reshaped software development and operations by emphasizing automation, continuous integration/delivery, and rapid feedback. However, organizations still struggle to achieve predictable improvements despite widespread adoption. In this study, we propose an “IDEAL-Enhanced DevOps” framework that integrates the five-phase IDEAL model—Initiate, Diagnose, Establish, Act, and Learn—into a DevOps transformation process. The proposed method lays out a structured approach to applying incremental improvements throughout the software delivery process. By a review of literature, in-depth analysis of case studies, and dis-semination of a questionnaire to practitioners in the field, this research explains how the IDEAL stages can be mapped to key processes in DevOps, address automation and scalability challenges, and facilitate a learning-centered, cooperative culture. The results show that a well-defined process-improvement approach can effectively reduce error incidence, enhance usability of tools, and significantly shorten time to get products to market. Our analysis shows that coupling IDEAL with DevOps not only clarifies responsibilities and organizational roles, but also lays a foundation for more resilient, high-quality, and adaptable software engineering methods.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of Toolchain Selection and Implementation

- Assessment of Technological Constraints (Diagnose Phase): Organizations evaluate their current infrastructure—whether legacy systems, hybrid environments, or cloud-native architectures—to determine appropriate automation and modernization strategies.

- Selection of Implementation Routes (Establish Phase): After detailed and extensive evaluation, companies have to take the key decision between adopting two fundamentally different routes: incrementally automated in accordance with their current legacy systems, or otherwise adopting superior and advanced optimisations that are cloud-native in design.

2.2. Version Control and Source Code Management

- Cloud-native organizations utilize GitHub for seamless integration with cloud-based CI/CD and serverless pipelines.

- Hybrid and on-premise organizations prefer to go with either GitLab or Bitbucket while choosing an on-premise version control solution. Both these organizations have immense benefits to offer, especially since both support in-built security compliance tools that secure their projects and content.

2.3. Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) Pipelines

- Incremental CI/CD Implementation in Legacy Systems: Within most enterprises, an emerging practice is to integrate with Jenkins to support mixed workflows or otherwise leverage GitLab CI/CD to achieve in-house automation.

- Comprehensive CI/CD Optimization in Natively Clouded Workloads: Organizations now increasingly employ tools including GitHub Actions, ArgoCD, or FluxCD to leverage declarative deployment methods following the principles of GitOps. Furthermore, these tools support management of multi-cloud orchestration to have improved process deployments in diverse cloud setups.

- GitOps-Driven Deployments: Cloud-first organizations adopt ArgoCD and FluxCD to ensure self-healing Kubernetes workloads and infrastructure-as-code governance.

2.4. Code Quality and Security Scans

- Within the legacy application context, full functionality is achieved through extensive static analysis by leveraging advanced capabilities through SonarQube. Checkmarx and Trivy tools are used to support increment scanning in order to efficiently handle and optimize workloads in a containerized context.

- Within the context of cloud-native infrastructure, automated policy enforcement is achieved through leveraging an assortment of specialized tools, including Open Policy Agent (OPA), Kyverno, and Aqua Security. This enforcement process is implemented with the ultimate goal of ensuring that environments running in Kubernetes have continuous and continuous verification of compliance in perpetuity.

2.5. Containerization and Orchestration

- Within hybrid organizations, workloads are orchestrated through making use of Kubernetes clusters that run locally. Such clusters have the ability to efficiently balance workloads that are located both in an on-premises context and in cloud environments.

- Organizations that value agility and efficiency in mostly cloud-based environments can achieve these aims by taking full-managed options including OpenShift, AWS Fargate, and automated Kubernetes tools. Together, these options support scalability while guaranteeing reliability in process management.

2.6. Monitoring, Logging, and Observability

- Traditional monitoring for legacy applications: Nagios, Prometheus, and basic logging solutions enable incremental observability for on-premise systems.

- Advanced observability in cloud-native DevOps is necessary in this era where technology is changing incredibly fast. Tools like OpenTelemetry, Grafana, and

- ELK Stack take over to accomplish this through capabilities that range from real-time distributed traces to system-wide in-depth analytics to efficient log centralization.By providing multiple options for gradual adoption to observability, IDEAL efficiently eliminates the incidence of data overload that has been known to affect conventional enterprises. Meanwhile, it provides solid support to advanced monitor requirements necessary in cloud-native systems.

2.7. Policy and Compliance Governance

2.8. Decision Making Process in the IDEAL Framework in Choosing an Acceptable and Proper Toolchain

- Legacy-bound enterprises: Prioritize incremental automation, container adoption, and hybrid CI/CD integrations.

- Hybrid organizations: Balance between on-premise infrastructure & cloud-native DevOps while maintaining security compliance in the layer of orchestration.

- Organizations that have cloud-first in their strategical vision stress adopting automated practices through practices in GitOps, in addition to advanced methods in container orchestration and integrating chaos engineering practices, as key steps to reinforce resilience to potential failures.

3. Frameworks

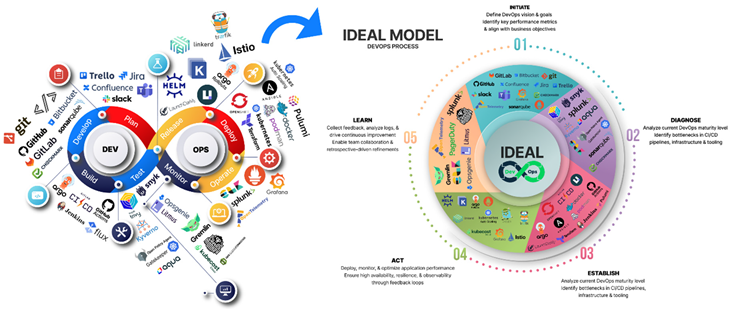

3.1. IDEAL Model Enhanced DevOps

3.1.1. IDEAL-Enhanced DevOps that Is in Accordance with Present Practices and Methods that Have Been Established in DevOps.

- Deployment Frequency (DF) – This is the frequency with which new releases of software are deployed and delivered to customers.

- Lead Time to Change (LT) – This is used to describe the amount of time required to properly apply changes, perform required testing, and ultimately deploy those changes to the appropriate environment.

- Change Failure Rate (CFR) refers to the percentage in specifics of changes that ultimately lead to an undesirable conclusion indicated by failure.

- Mean Time to Restore (MTTR) is an indicator used to monitor performance that reflects an average amount of time to restore following an incidence or failure event.

3.1.2. Initiate – Strategic Planning and Objective Setting

3.1.3. Diagnose – Identifying Bottlenecks and Security Gaps

3.1.4. Establish – Implementing Core DevOps Practices

3.1.5. Act – Deployment, Scaling, and Observability

3.1.6. Learn - Continuous Feedback and Optimization

3.3. Results

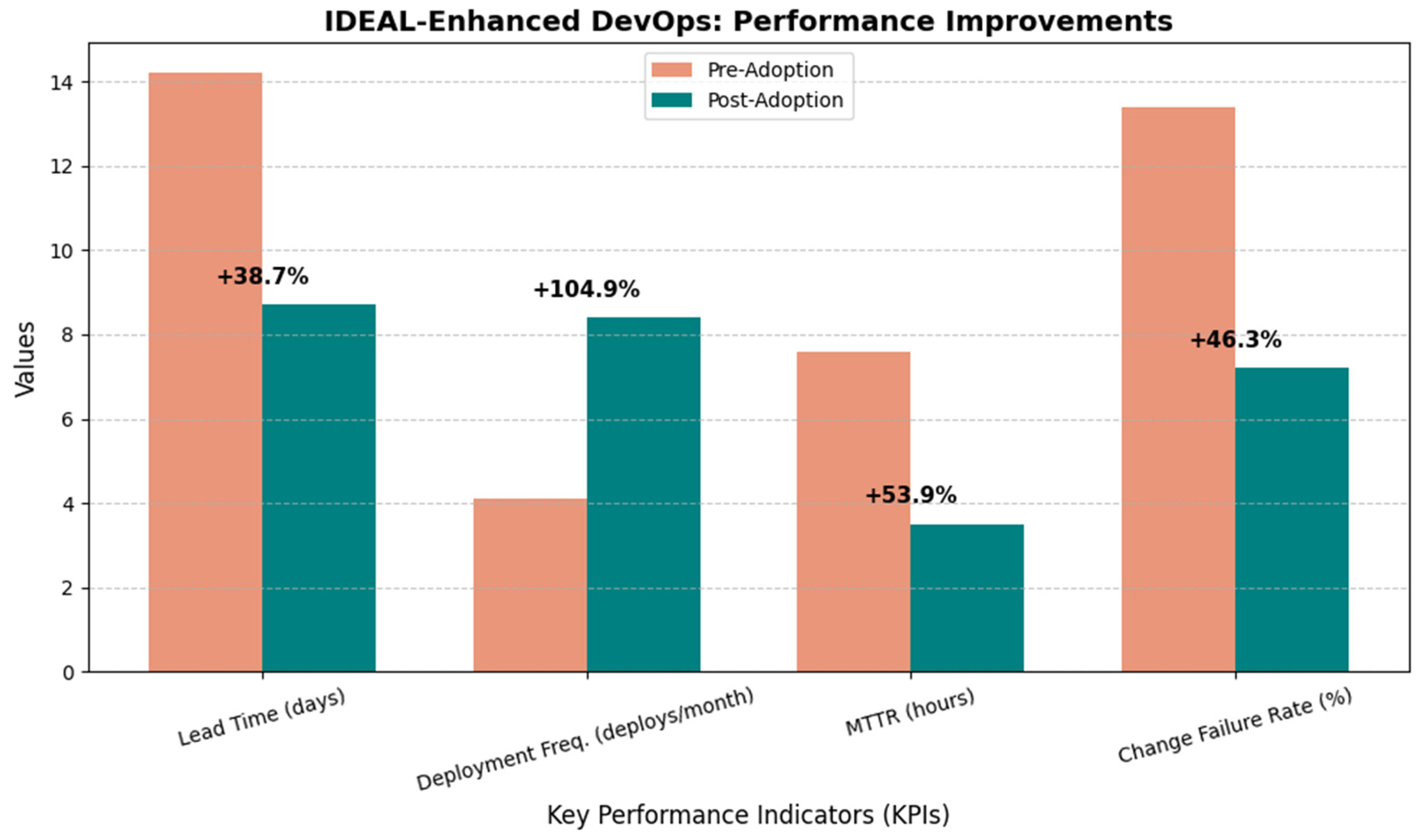

3.3.1. Quantitative Findings

- Lead Time (days): Number of days from code commit to release to production.

- Deployment Frequency (deploys per month): A measure of how often a production environment is released or updated.

- Mean Time to Restore (MTTR) (hours): Average time to restore from a production outage.

- Change Failure Rate (%): Percentage of changes which result in unacceptable service and must be remediated.

3.4. Subsection

3.4.1. Subsubsection

- Having specific cross-functional groups helped with increased problem-solving through a focused, coherent pipeline mechanism.

- Institutionalized feedback processes reduced feedback lag.

- Sharing of information at an overall level encouraged uniform practice acceptance.

- Normalized pipelines for CI/CD reduced configuration drift.

- Automated testing techniques (unit, integration, and load testing) lowered defects significantly.

- Integration between ticketing, version controls, and platforms for deployment was performed seamlessly, providing real-time update information for statuses.

- Clear roles for each IDEAL stage helped maintain accountability.

- Bi-monthly audits (for six weeks at a stretch) helped recalibrate performance markers.

- Well-planned training programs kept workforce updated with new tool competencies at all times.

- End-To-End Visibility: Real-time dashboards helped monitor build statuses, environment statistics, and feedback received from users.

- Automated Quality Gates: Unit testing requirements of at least 85%, and integration testing pass requirements over 95%, were mandated.

- Iterative Learning Cycles: Bi-monthly retrospectives took place, with a specific focus to detect in which IDEAL stage adjustments and refinements must be addressed.

3.5. Figures, Tables and Schemes

| KPI | Pre-Adoption | Post-Adoption (Mean) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead Time (days) | 14.2 | 8.7 | 38.7% |

| Deployment Freq. (deploys/month) | 4.1 | 8.4 | 104.9% |

| MTTR | 7.6 | 3.5 | 53.9% |

| Change Failure | 13.4% | 7.2% | 46.3% |

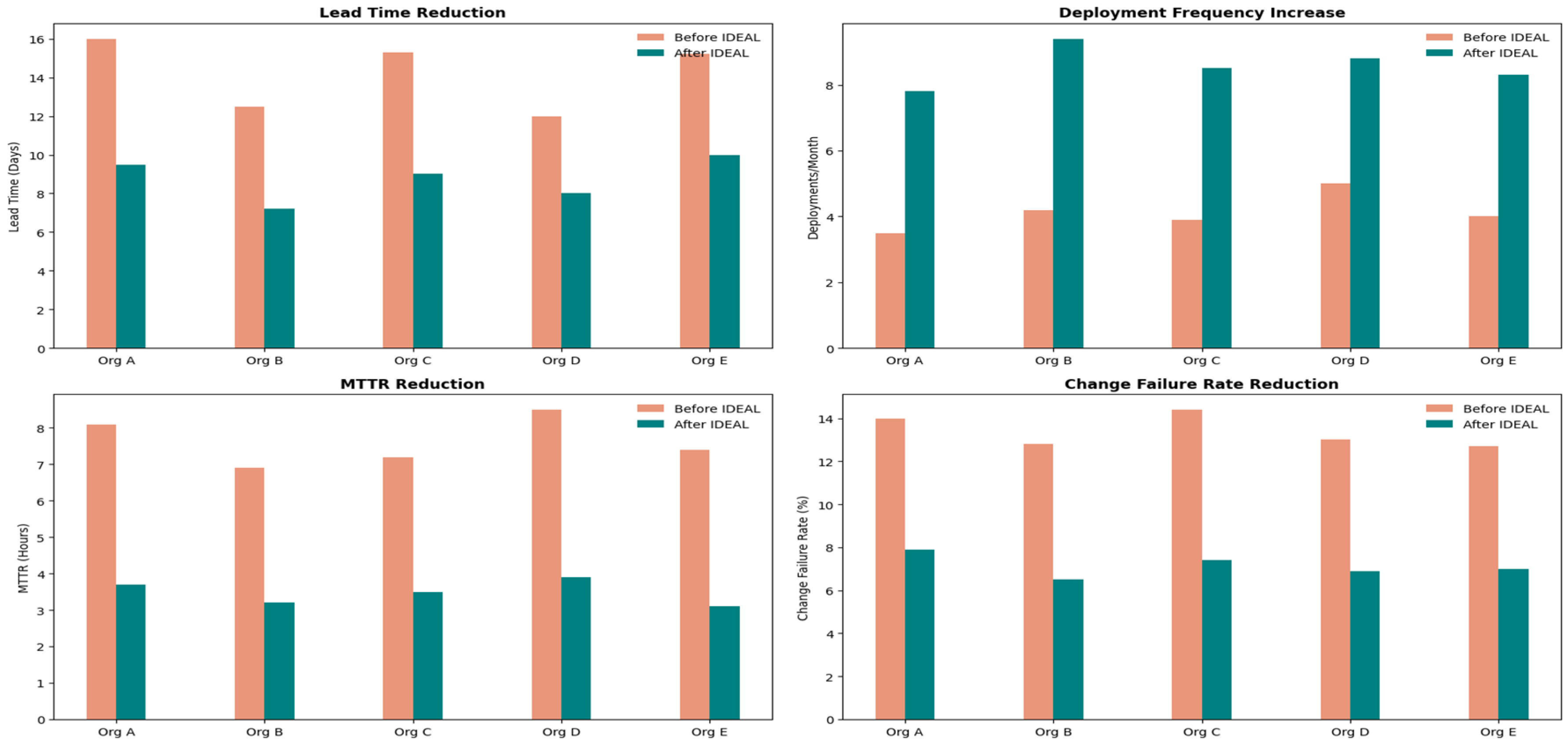

| Org | Employees | Leads Time (Days) | Deployment Frequency | MTTR (Hours) | Change Failure Rat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 12,000 | 16.0 → 9.5 | 3.5 → 7.8 | 8.1 → 3.7 | 14.0% → 7.9% |

| B | 9,500 | 12.5 → 7.2 | 4.2 → 9.4 | 6.9 → 3.2 | 12.8% → 6.5% |

| C | 10,800 | 15.3 → 9.0 | 3.9 → 8.5 | 7.2 → 3.5 | 14.4% → 7.4% |

| D | 700 | 12.0 → 8.0 | 5.0 → 8.8 | 8.5 → 3.9 | 13.0% → 6.9% |

| E | 600 | 15.2 → 10.0 | 4.0 → 8.3 | 7.4 → 3.1 | 12.7% → 7.0% |

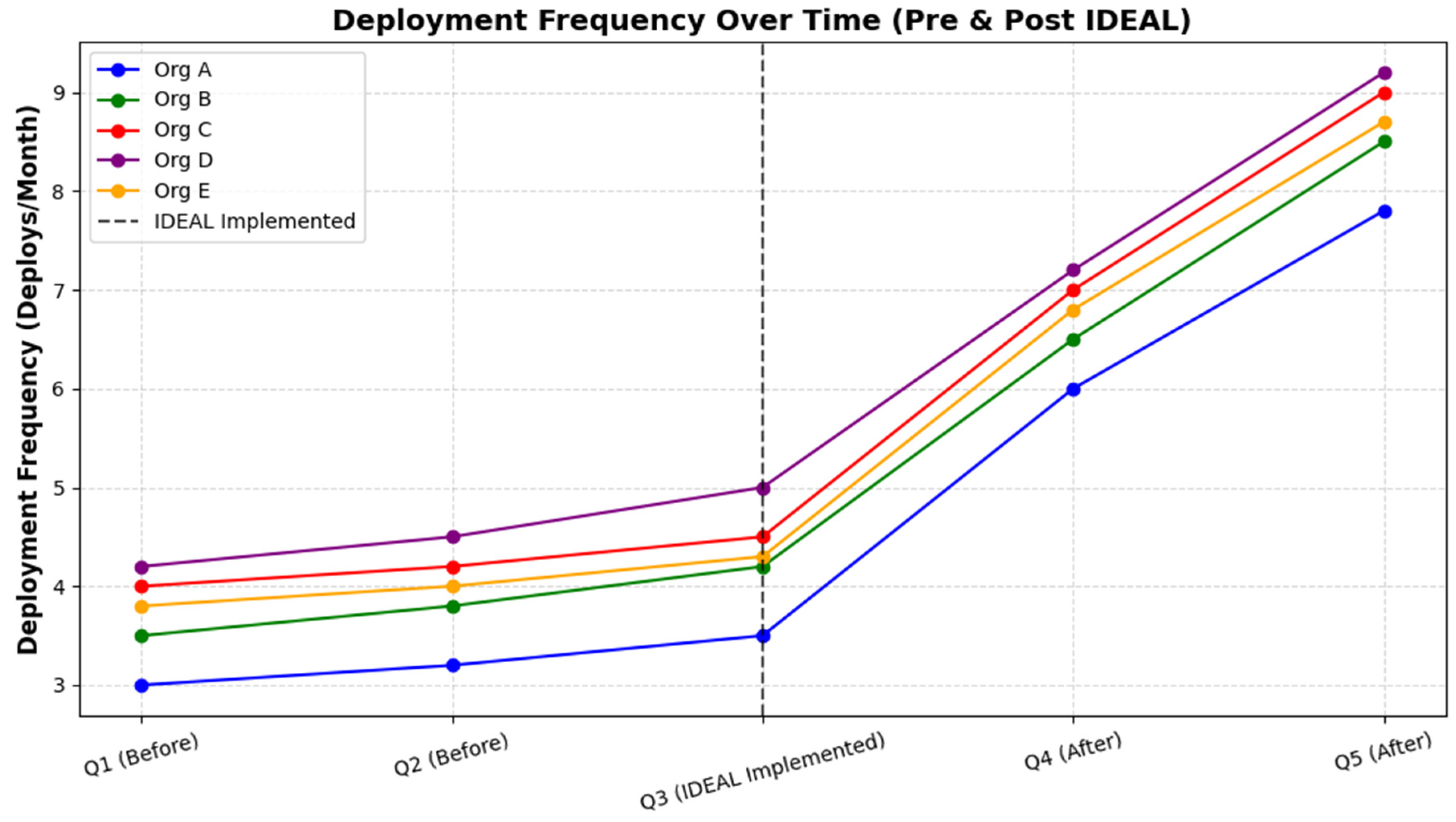

| Quarter | Org A | Org B | Org C | Org D | Org E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3.0 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 3.8 |

| B | 3.2 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 4.0 |

| C | 3.5 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 4.3 |

| D | 6.0 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 7.2 | 6.8 |

| E | 7.8 | 8.5 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 8.7 |

3.6. Formatting of Mathematical Components

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bass, L. , Weber, I., & Zhu, L. (2015). DevOps: A Software Architect’s Perspective. Addison-Wesley Professional.

- 2. Forsgren, N., & Kersten, M. (2018). DevOps delivers. Communications of the ACM, 61(4), 32–33.

- Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, C., Gallardo, G., Hernantes, J., & Serrano, N. (2016). DevOps. IEEE Software, 33(3), 94–100.

- Basiri, A. , van der Hoek, A., Brun, Y., & Medvidovic, N. (2019). Chaos engineering: A systematic review of approaches and challenges. ACM Computing Surveys, 52(5), 1-40. [CrossRef]

- Behnke, R. , Stier, C., Schmid, K., & Lehrig, S. (2021). Observability as a first-class citizen: Towards a structured approach to system monitoring. Journal of Systems and Software, 179, 110999. [CrossRef]

- Chacon, S.; Straub, B. Pro Git; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, GX, Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, B.; Stol, K.-J. Continuous software engineering: A roadmap and agenda. J. Syst. Softw. 2017, 123, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, D. (2014). Docker: Lightweight Linux containers for consistent development and deployment. Linux Journal, 2014(239), 2.

- Morris, K. (2020). Infrastructure as Code: Dynamic Systems for the Cloud Age (2nd ed.). O’Reilly Media.

- Rahman, M. M. , Helms, E., Williams, L., & Bird, C. (2021). Feature toggles: A systematic mapping study and survey of practitioners. Empirical Software Engineering, 26(5), 1-40. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Meneely, A.; Williams, L.; Osborne, J.A. Evaluating Complexity, Code Churn, and Developer Activity Metrics as Indicators of Software Vulnerabilities. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2010, 37, 772–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. , Debois, P., Willis, J., & Humble, J. (2021). The DevOps Handbook: How to Create World-Class Agility, Reliability, & Security in Technology Organizations. IT Revolution Press.

- Kerzner, H. (2019). Strategic Planning for Project Management Using a Maturity Model. Wiley.

- Pautasso, C.; Zimmermann, O.; Amundsen, M.; Lewis, J.; Josuttis, N. Microservices in Practice, Part 1: Reality Check and Service Design. IEEE Softw. 2017, 34, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Nazir, S.; Bai, Y.; Anees, A. Security and provenance for Internet of Health Things: A systematic literature review. J. Software: Evol. Process. 2021, 33, e2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Wang, J.; Liu, D.; Guo, W.; Wu, P.; Bao, X. Byte-level malware classification based on markov images and deep learning. Comput. Secur. 2020, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, I. , Pérez, J., Díaz, J., López-Fernández, D., Pais, M., Kon, F., & Rocha, C. (2023). Harmonizing DevOps taxonomies—Theory operationalization and testing. 0003; arXiv:2302.00033. https://arxiv.org/abs/2302. [Google Scholar]

- Bildirici, F. , & Codal, K. DevOps and agile methods integrated software configuration management experience. arXiv preprint 1 arXiv:2306.13964. https://arxiv.org/abs/2306, 3964.

- Gokarna, M.; Singh, R. DevOps: A Historical Review and Future Works. 2021 International Conference on Computing, Communication, and Intelligent Systems (ICCCIS). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 366–371.

- Gwangwadza, A. , & Hanslo, R. (2022). Factors that contribute to the success of a software organisation’s DevOps environment: A systematic review. 0410; arXiv:2211.04101. https://arxiv.org/abs/2211. [Google Scholar]

- Kon, F. , Milojić, D., Meirelles, P., & Stettina, C. J. (2020). A survey of DevOps concepts and challenges. Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/ACM 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Marques, P. , & Correia, F. F. (2023). Foundational DevOps patterns. 0105; arXiv:2302.01053. https://arxiv.org/abs/2302. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, D. , Rawool, K. Automated DevOps pipeline generation for code repositories using large language models. arXiv preprint 1 arXiv:2312.13225. https://arxiv.org/abs/2312, 3225.

- Offerman, T.; Blinde, R.; Stettina, C.J.; Visser, J. A Study of Adoption and Effects of DevOps Practices. 2022 IEEE 28th International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC) & 31st International Association For Management of Technology (IAMOT) Joint Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, FranceDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–9.

- Senapathi, M. , Buchan, J., & Osman, H. (2019). DevOps capabilities, practices, and challenges: Insights from a case study. Proceedings of the 2019 ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Tanzil, M.H.; Sarker, M.; Uddin, G.; Iqbal, A. A mixed method study of DevOps challenges. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2023, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsgren, N. , & Storey, M.-A. (2020). DevOps metrics and performance: A large-scale study of the four key metrics. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 46(8), 865-890. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A. , & Lee, S. P. ( 29(5), 653–670. [CrossRef]

- Kerzner, H. (2019). Strategic continuous improvement with DevOps: An IDEAL-based approach. Project Management Journal, 50(2), 117-134. [CrossRef]

- Lwakatare, L. E. , Kuvaja, P., & Oivo, M. (2016). Dimensions of DevOps. International Conference on Agile Software Development (XP), Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, 251, 212-225. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Madeyski, L. , & Kitchenham, B. (2020). Software quality and DevOps: A systematic literature review. Journal of Systems and Software, 170, 110717. [CrossRef]

- Mojtaba, S. , Bass, J. M., & Schneider, J. (2017). Continuous integration, delivery, and deployment: A systematic review. IEEE Access, 5, 3909-3943. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).