Submitted:

12 June 2023

Posted:

13 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

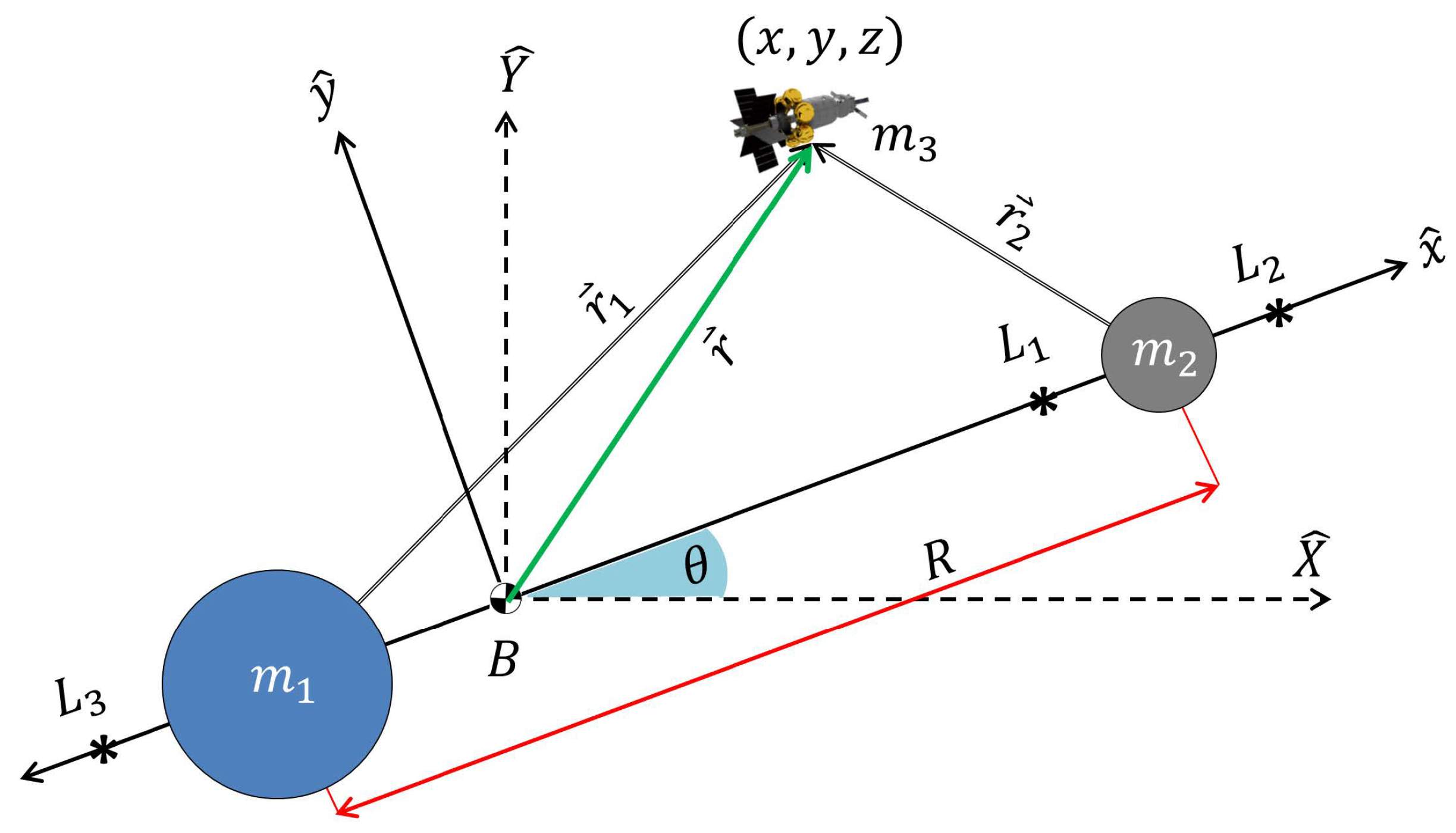

2. Background Theory

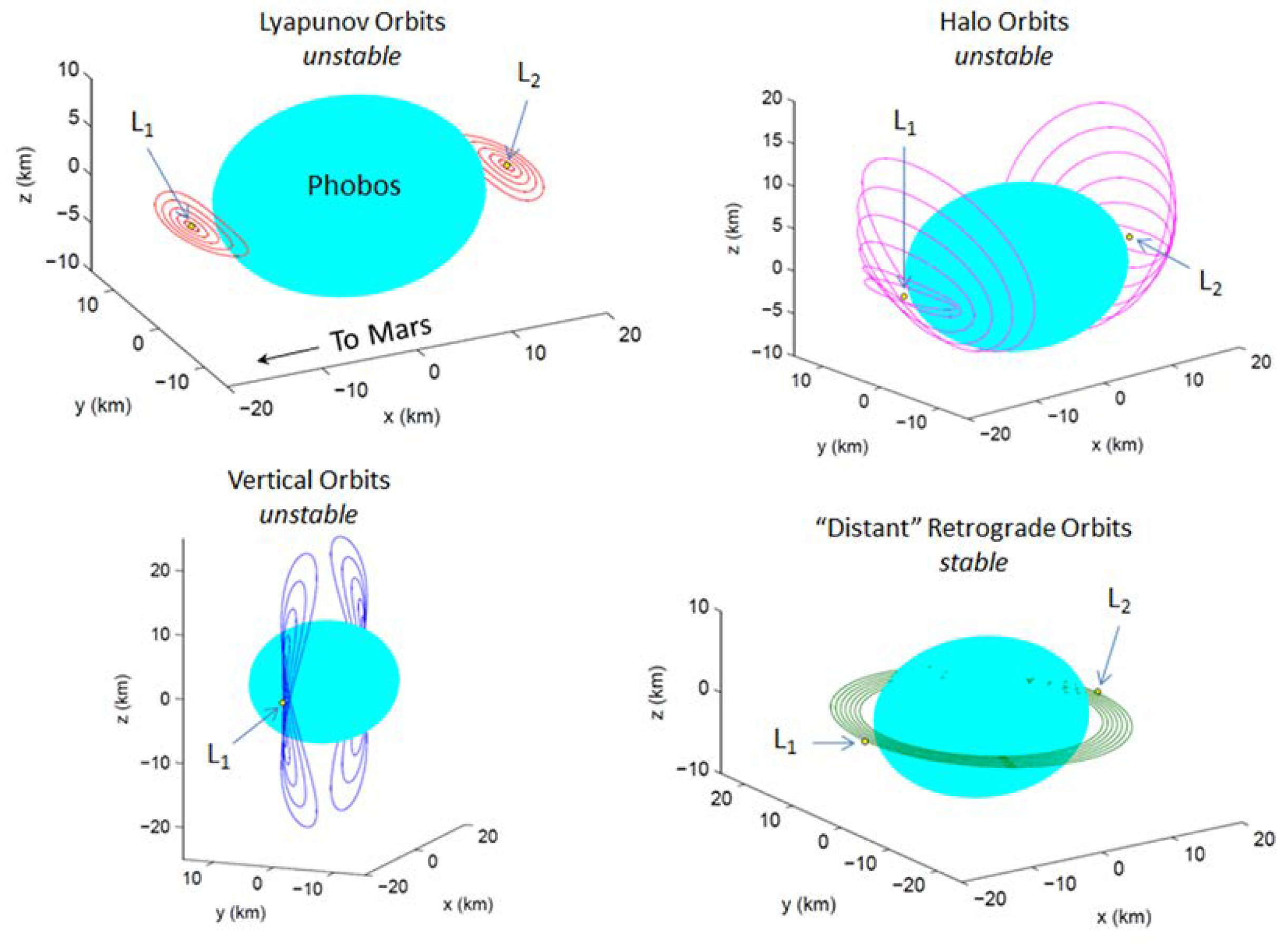

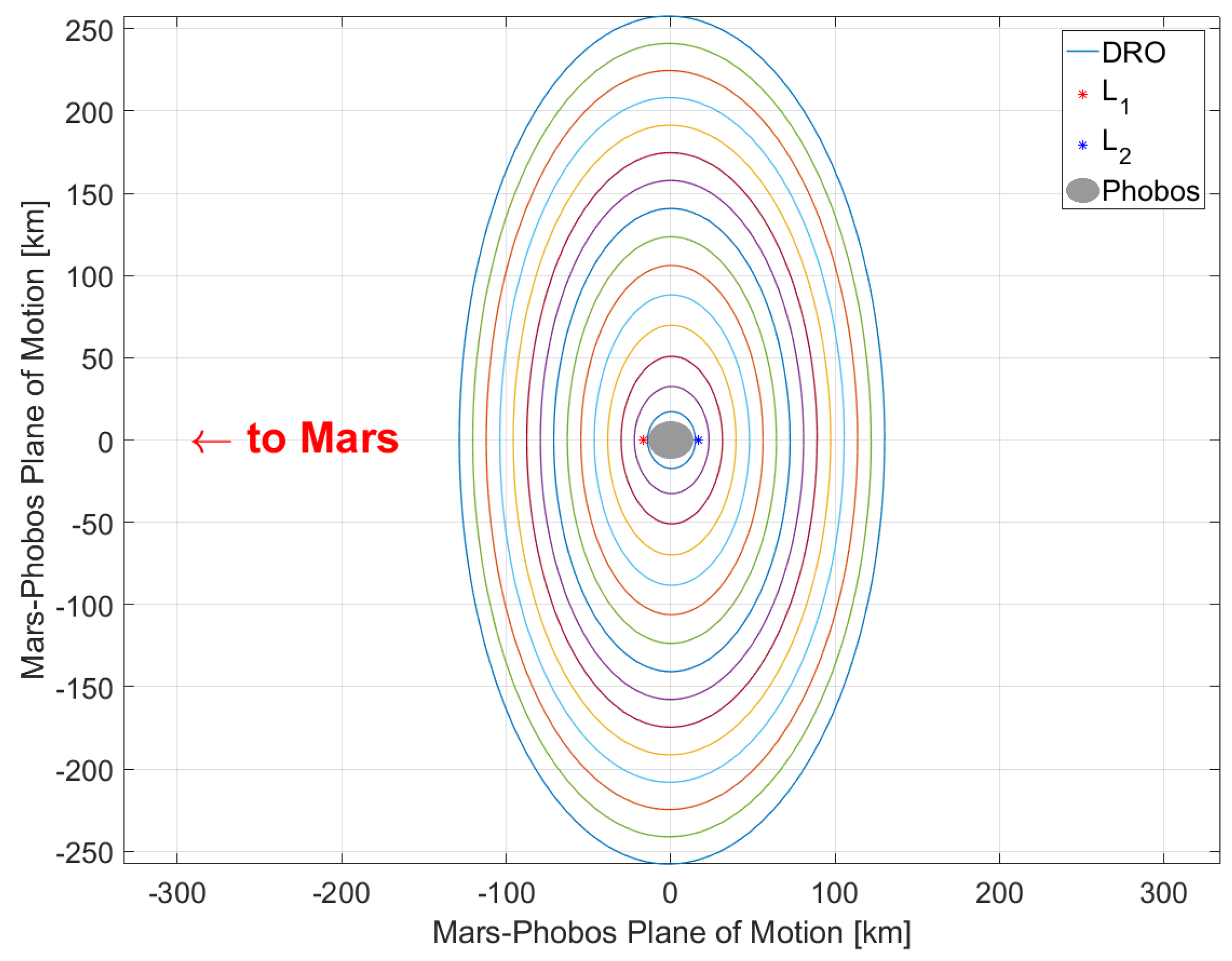

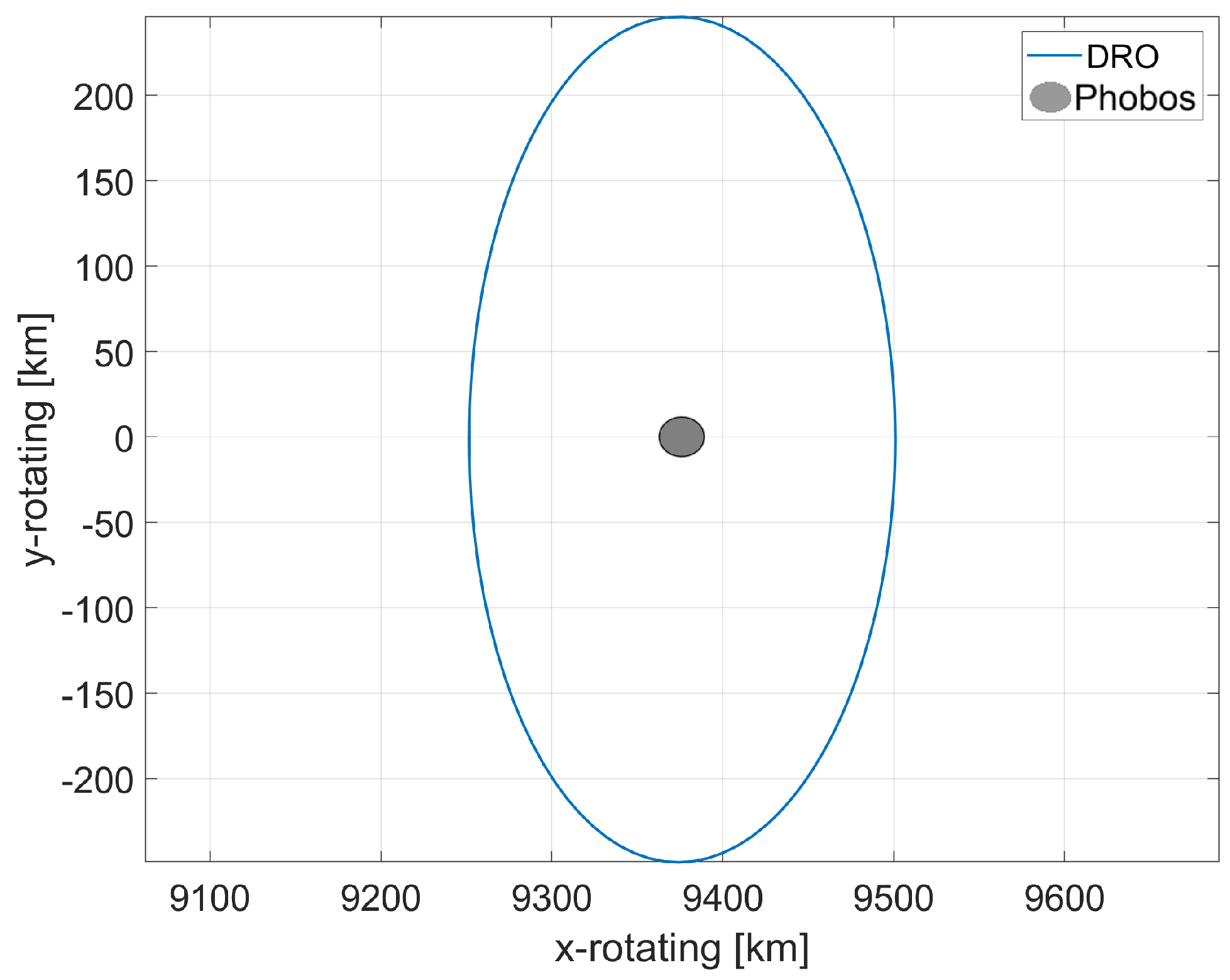

2.1. Distant Retrograde Orbits

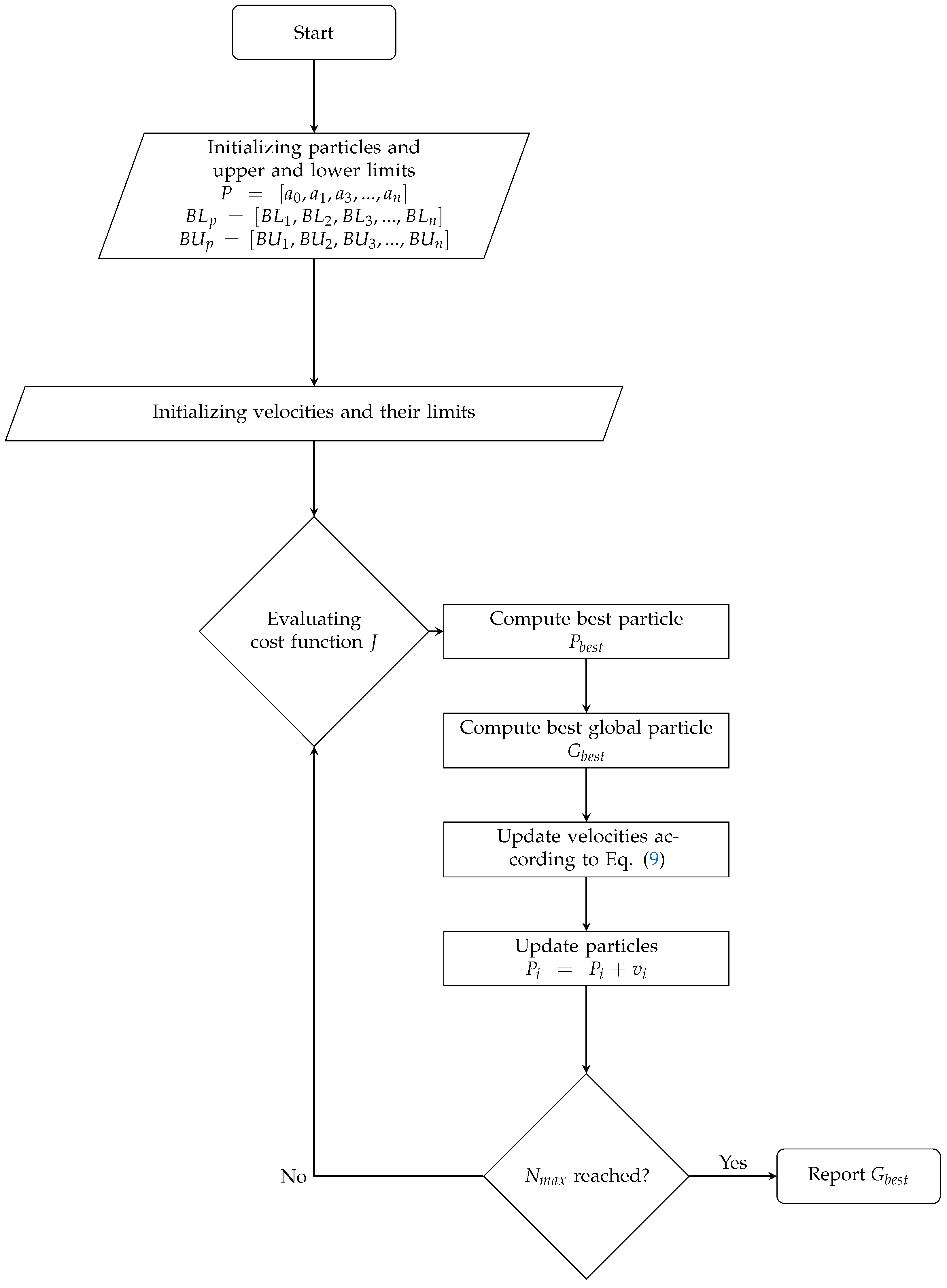

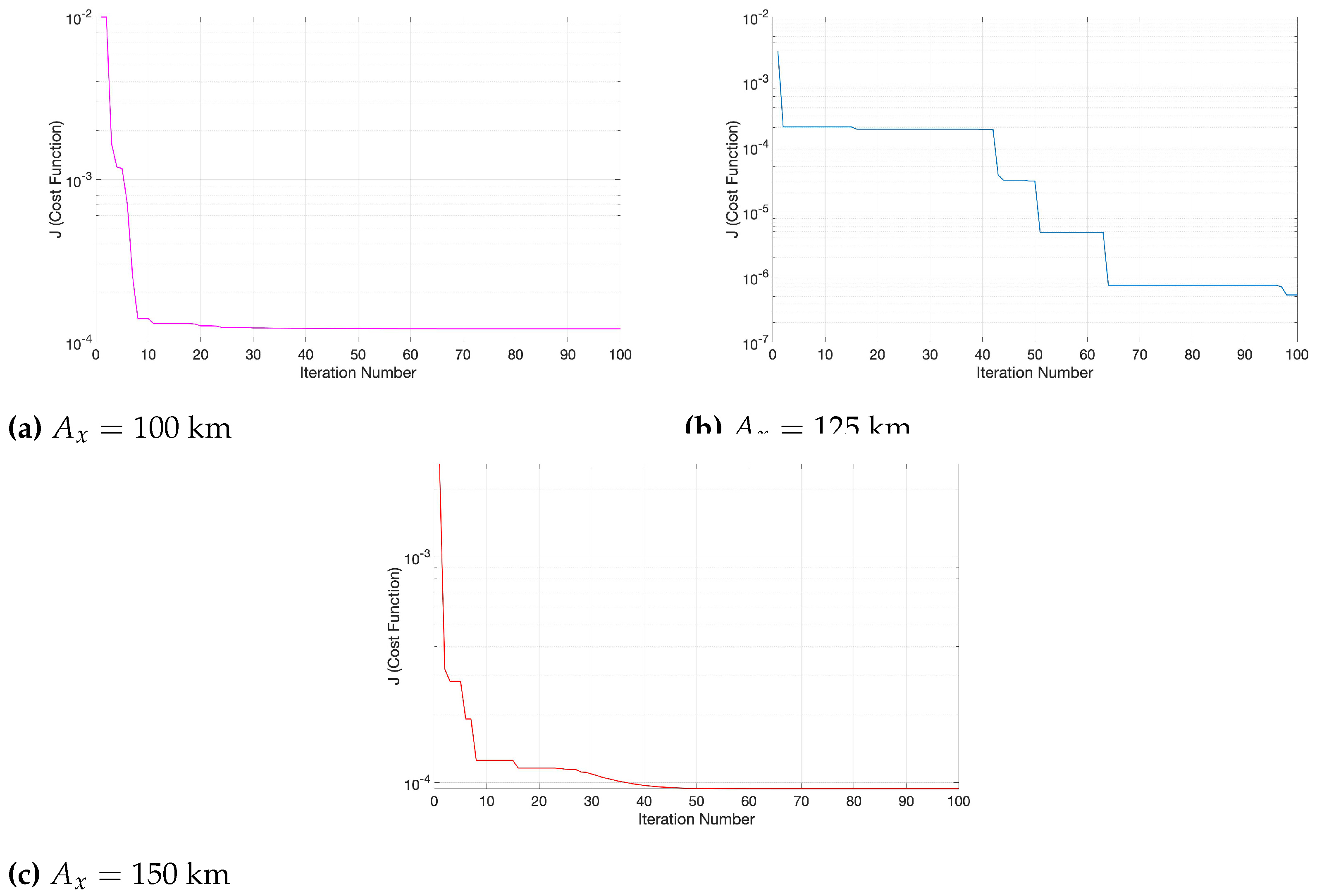

2.2. Particle Swarm Optimization

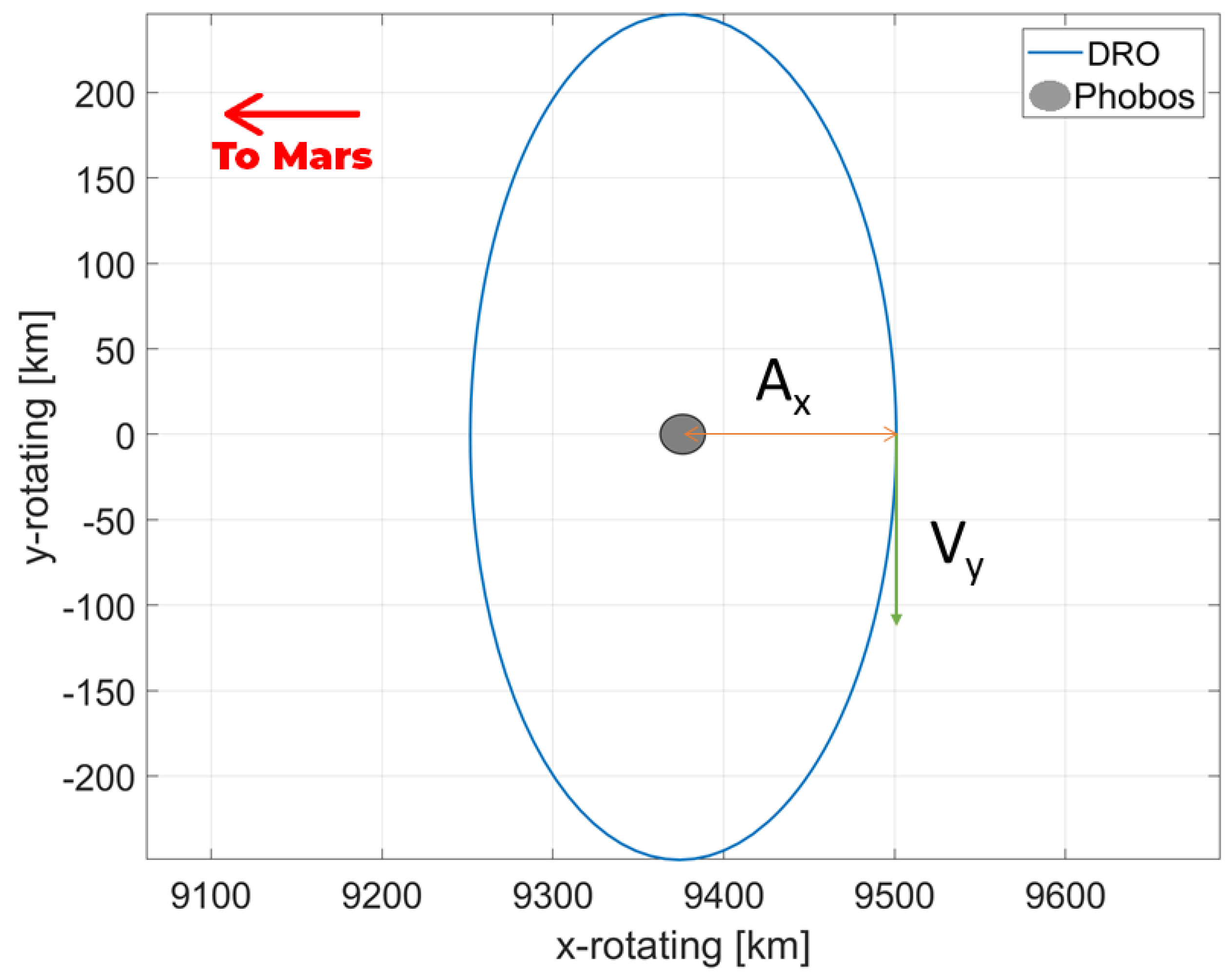

2.3. Mars-Phobos DRO

| Variable | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| (km3 s−2) | Gravitational parameter for Phobos |

|

| (km3 s−2) | Gravitational parameter for Mars |

|

| Mass ratio | ||

| R (km) | 9376 | Average distance Mars-Phobos |

| (km) | 125 | DRO Amplitude |

| Variable | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| () | Lower limit for (km/s) | |

| () | Upper limit for (km/s) | |

| () | T | Lower limit for T (s) |

| () | Upper limit for T (s) | |

| 80 | Maximum number of iterations | |

| 40 | Number of particles |

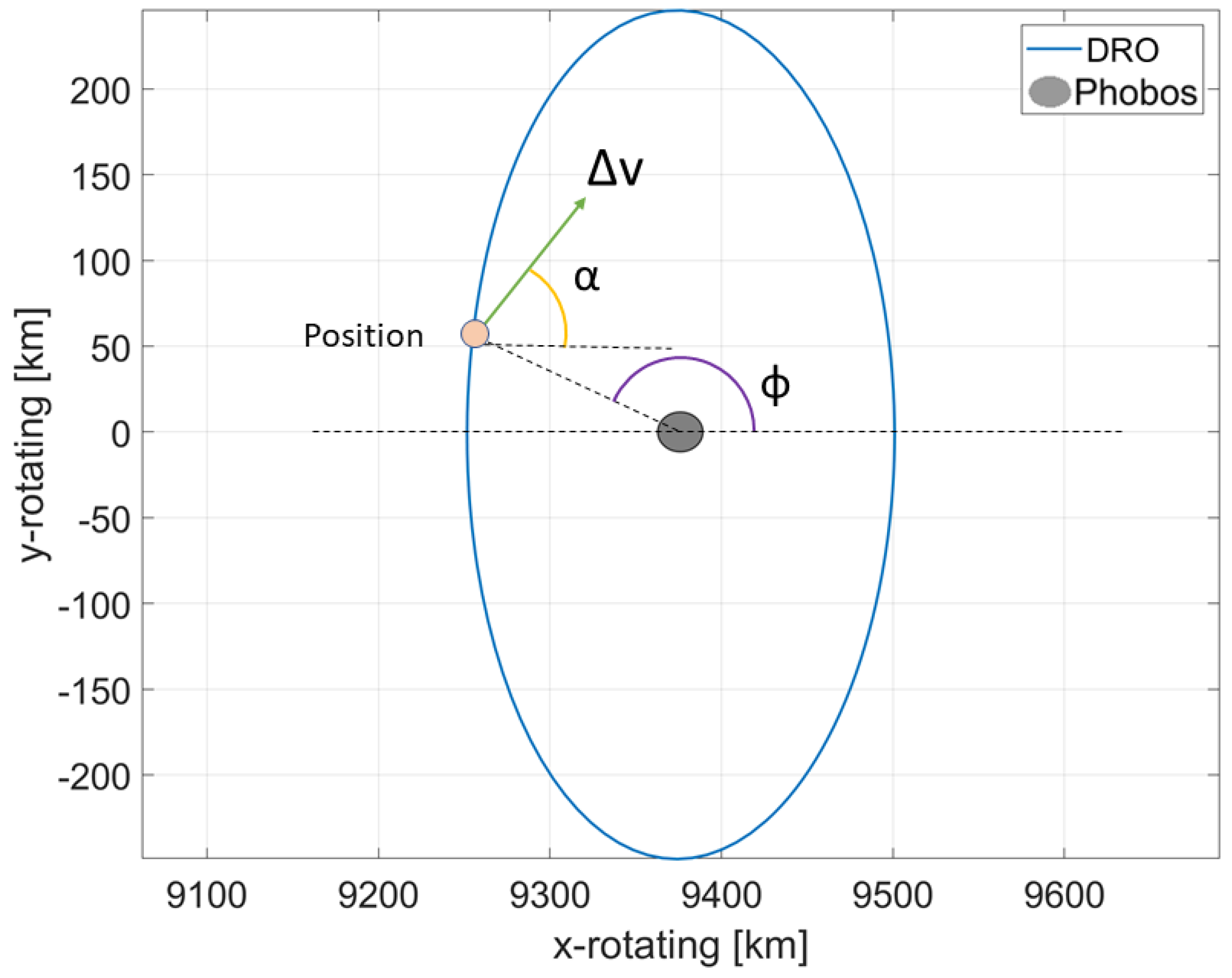

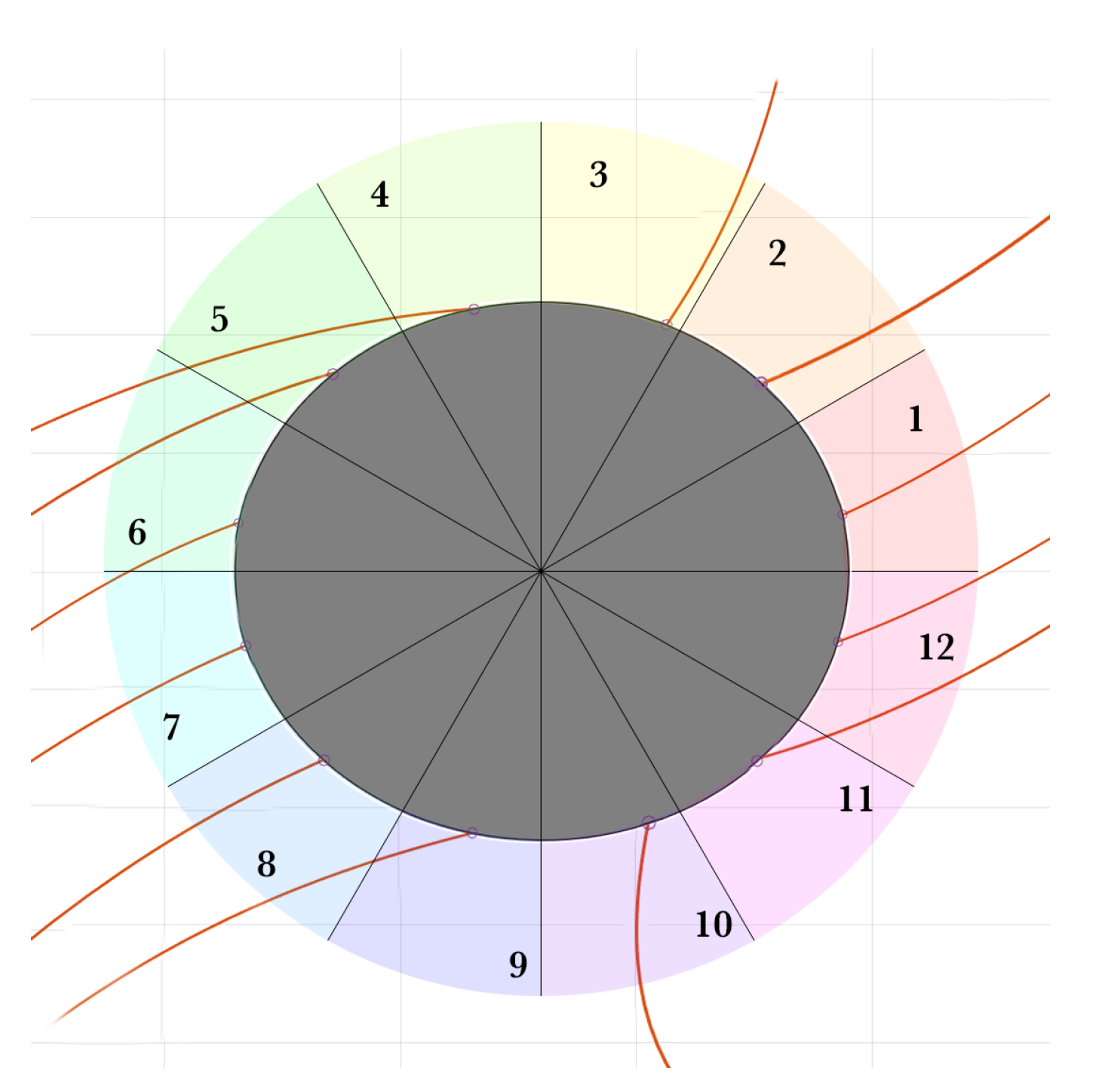

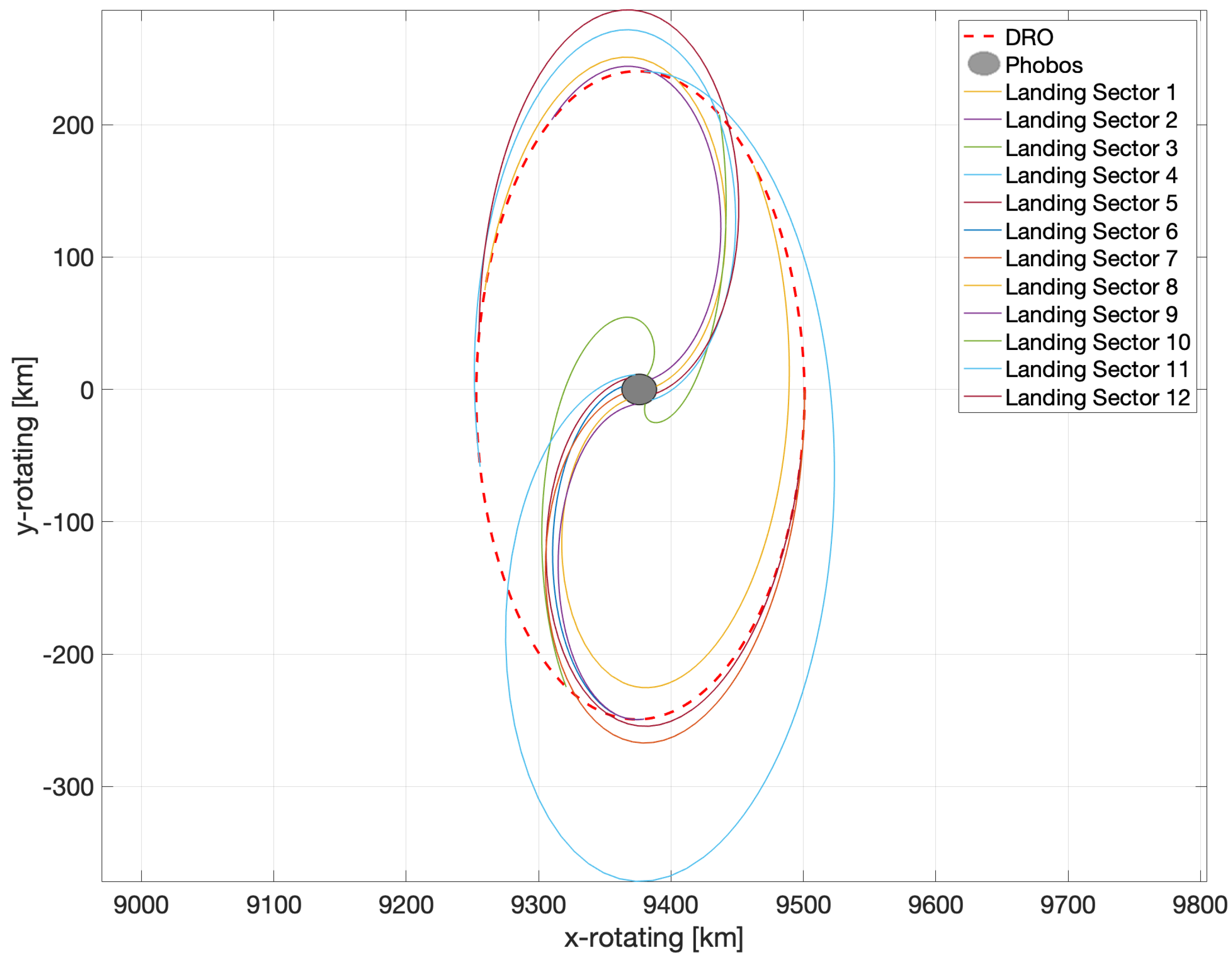

3. Landing Trajectory Optimization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Change in velocity (km/s) | |

| e | Orbit eccentricity |

| Larger x-coordinate from the primary body in the Circular Restricted Three-Body Problem (km) |

|

| y-component of velocity (km/s) | |

| Maximum number of iterations used in Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) |

|

| T | Orbital Period (s) |

| Number of particles used in PSO | |

| J | Cost function |

| Mass ratio of Mars and Phobos | |

| Position vector | |

| Velocity vector | |

| Number of particles in PSO | |

| Lower limit for particles in PSO | |

| Upper limit for particles in PSO | |

| Angle with respect to the x-axis at which the is applied (°) | |

| Position along the orbit with respect to the x-axis, starting at (°) | |

| Initial position vector | |

| Initial velocity vector | |

| Final position vector | |

| Final velocity vector | |

| Penalty scaling factor used by PSO | |

| Gravitational parameter (km3/s2) | |

| Total spacecraft mass (mt) | |

| Dry spacecraft mass (mt) | |

| Propellant mass (mt) | |

| Specific Impulse (s) | |

| Standard acceleration due to gravity at Earth’s sea level (m/s2) | |

| Exhaust velocity (m/s) |

References

- Loff, S. Lunar Gateway. 2012. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/topics/moon-to-mars/lunar-outpost (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Johnson, S.K.; Mortensen, D.J.; Chavez, M.A.; Woodland, C.L. Gateway – a communications platform for lunar exploration. In Proceedings of the 38th International Communications Satellite Systems Conference (ICSSC 2021), Vol. 2021; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) White Paper: Gateway Destination Orbit Model: A Continuous 15 Year NRHO Reference Trajectory. 2019.

- JAXA. Martian Moons Exploration: Mission Overview. http://www.isas.jaxa.jp/en/topics/files/MMX170412_EN.pdf, 2017.

- Ulamec, S.; Michel, P.; Grott, M.; Boettger, U.; Hübers, H.W.; Schröder, S.; Cho, Y.; Rull, F.; Murdoch, N.; Vernazza, P.; et al. Surface science on Phobos with the MMX Rover. 2022.

- Adams, E.; Murchie, S.; Eng, D.; Chabot, N.; Guo, Y.; Arvidson, R.; Trebi-ollennu, A.; Seelos, F. Mission concept for robotic exploration of Deimos. 61st International Astronautical Congress 2010, IAC 2010 2010, 11, 9249–9259. [Google Scholar]

- Ulamec, S.; Michel, P.; Grott, M.; Boettger, U.; Hübers, H.W.; Cho, Y.; Rull, F.; Murdoch, N.; Vernazza, P.; Biele, J.; et al. The MMX Rover Mission to Phobos: Science Objectives. 2021.

- Hopkins, J.; Pratt, W. Comparison of Phobos and Deimos as Destinations for Human Exploration, and Identification of Preferred Landing Sites. AIAA Space 2011 Conference and Exposition 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L. Lockheed Martin: Mars Base Camp. https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/products/mars-base-camp.html, 2012. Accessed: 2020-04-12.

- Cichan, T.; Norris, S.; Chambers, R.; Jolly, S.; Scott, A.; Bailey, S. Mars Base Camp: A Martian Moon Human Exploration Architecture. AIAA Space 2016 Conference and Exposition 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chican, T.; Bailey, S.; Antonelli, T.; Jolly, S.; Chambers, R.; Ramm, S. Mars Base Camp: An Architecture for Sending Humans to Mars. New Space 2017, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Conte, D. Determination of Optimal Earth-Mars Trajectories to Target the Moons of Mars. The Pennsylvania State University (Department of Aerospace Engineering).

- Bezrouk, C.; Parker, J. Ballistic Capture into DROs around Phobos: an Approach to Entering Orbit around Phobos without a Critical Maneuver near the Moon. Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy 2018, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraeman, A. Analysis of Disk-Resolved OMEGA and CRISM Spectral Observation of Phobos and Deimos. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2012, 117, 1991–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessen, A. Phobos: by the numbers. Available online: http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/mars-moons/phobos/by-the-numbers/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Conte, D.; Spencer, D. Mission Analysis for Earth to Mars-Phobos Distant Retrograde Orbits. Acta Astronautica 2018, 151, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borderies, N.; Yoder, C. Phobos Gravity Field and its Influence on its Orbit and Physical Libration. Astronomy and Astrophysics 1990, 233. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Willner, K.; Oberst, J.; Ping, J.; Ye, S. Earth-Mars Transfers through Moon Distant Retrograde Orbits. SCIENCE CHINA: Physics, Mechanics, and Astronomy 2012, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Maistre, S.L.; Rivoldini, A.; Rosenblatt, P. Signature of Phobos’ Interior Structure in its Gravity Field and Libration. Icarus 2019, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.; Parker, J.; Streange, N.; Grebow, D. Orbital Operations for Phobos and Deimos Exploration. AIAA/AAS Astrodynamics Specialist Conference 2012, 5067. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, C.; Spencer, D. Stability Mapping of Distant Retrograde Orbits and Transports in the Circular Restricted Three-Body Problem. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Bezrouk, C.; Parker, J. Long Duration Stability of Distant Retrograde Orbits. AIAA Space Forum 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, K.; de Week, O.; Hoffman, J.; Shishko, R. Dynamic Modeling and Optimization for Space Logistics using Time-Expanded Networks. Acta Astronautica 2014, 105(2), 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA. Artemis Plan: NASA’s Lunar Exploration Program Overview. https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/artemis_plan-20200921.pdf, 2020.

- Conte, D.; Carlo, M.D.; Ho, K.; Spencer, D.; Vasile, M. Earth-Mars Transfers through Moon Distant Retrograde Orbits. Acta Astronautica 2018, 143, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontani, M. Simple Method to Determine Globally Optimal Orbital Transfers. Journal of Guidance, Control and Dynamics 2009, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontani, M.; Ghosh, P.; Conway, B. Particle Swarm Optimization of Multiple-Burn Rendezvous Trajectories. Journal of Guidance, Control and Dynamics 2012, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontani, M. Particle Swarm Optimization of Ascent Trajectories of Multi-Stage Launch Vehicles. Acta Astronautica 2014, 94, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhart, R.; Kennedy, J. A New Optimizer using Particle Swarm Theory. Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Micromachine and Human Science 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart, R.; Kennedy, J. Particle Swarm Optimization. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Neural Networks 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pontani, M.; Conway, B. Particle Swarm Optimization applied to Space Trajectories. Journal of Guidance, Control and Dynamics 2010, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontani, M.; Conway, B. Particle Swarm Optimization applied to Impulsive Orbital Transfers. Acta Astronautica 2012, 74, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, D. Semi-Analytical Solutions for Proximity Operations in the Circular Restricted Three Body Problem. The Pennsylvania State University (Department of Aerospace Engineering).

- Conte, D.; Spencer, D.; He, G.; Melton, R. Fireworks Algorithm applied to Trajectory Design for Earth to Lunar Halo Orbits. Journal of Spacecrafts and Rockets 2020. [Google Scholar]

- SpaceX. Starship - Official SpaceX Starship Page. Available online: https://www.spacex.com/vehicles/starship/ (accessed on 12 April 2020).

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Operating System | MacOS Big Sur Version 11.2.3 |

| Processor | 3.3 GHz Dual-Core Intel Core i7 |

| RAM | 16 GB 2133 MHz |

| MatLab version | R2020b Update 3 |

| System architecture | 64-bit operating system, x-64-based processor |

| Variable | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| () | 0 | Lower limit for (km/s) |

| () | Upper limit for (km/s) | |

| () | 0 | Lower limit for (rad) |

| () | Upper limit for (rad) | |

| () | 0 | Lower limit for (rad) |

| () | Upper limit for (rad) | |

| 200 | Maximum number of iterations | |

| 100 | Number of particles |

| Variable | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| (km) | Initial position of parking DRO |

|

| (km/s) | Orbit velocity at position |

|

| (s) | Orbital period |

| Landing Location Sector | Computation time |

|---|---|

| 1 | 2 min, 56 s |

| 2 | 2 min, 21 s |

| 3 | 3 min, 20 s |

| 4 | 2 min, 17 s |

| 5 | 2 min, 42 s |

| 6 | 2 min, 15 s |

| 7 | 2 min, 56 s |

| 8 | 3 min, 17 s |

| 9 | 2 min, 21 s |

| 10 | 2 min, 19 s |

| 11 | 2 min, 53 s |

| 12 | 4 min, 8 s |

| Average | 2 min, 54 s |

| Landing Loc. Sector | Time of Flight | Total (m/s) | (°) | (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 hrs, 41 min | 27.35 | 246.10 | 147.14 |

| 2 | 3 hrs, 51 min | 29.24 | 205.53 | 108.16 |

| 3 | 5 hrs, 10 min | 31.02 | 347.27 | 256.35 |

| 4 | 7 hrs, 33 min | 32.42 | 101.32 | 89.22 |

| 5 | 4 hrs, 54 min | 27.27 | 88.41 | 337.07 |

| 6 | 3 hrs, 29 min | 32 | 0 | 270.49 |

| 7 | 5 hrs, 13 min | 27.41 | 100.38 | 0 |

| 8 | 6 hrs, 6 min | 28.72 | 154.32 | 62.75 |

| 9 | 3 hrs, 41 min | 31.93 | 0 | 270.84 |

| 10 | 4 hrs, 24 min | 31.34 | 168.82 | 73.85 |

| 11 | 5 hrs, 36 min | 27.66 | 260.27 | 204.36 |

| 12 | 5 hrs, 13 min | 30.25 | 209.12 | 161.04 |

| Average | 4 hrs, 59 min | 29.72 m/s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).