1. Introduction

A critical step in planetary research is capturing a spacecraft from its hyperbolic trajectory to a closed orbit around the target planet. The traditional insertion burn method requires significant fuel allocation, reducing payload mass fraction. The aerocapture maneuver offers a solution that bypasses the need for large fuel fractions, potentially increasing payload capacity. Despite extensive study and optimization efforts, its implementation in interplanetary missions is yet to be realized due to spacecraft architecture difficulties and mission outcome sensitivity to minor, unpredictable uncertainties.

Recent optimization efforts in this field [

1,

2,

3,

4] have centered on the pursuit of efficient trans-atmospheric trajectories through meticulous manipulation of drag and lift forces to achieve an optimal aerocapture maneuver. Recent years have witnessed a push towards enhancing aerocapture technology through drag modulation (DM) techniques. These methods enable control over the spacecraft’s ballistic coefficient (

) by manipulating either the reference area or the drag coefficient (

) through continuous or discrete strategies, simplifying avionics and obviating the need for complex attitude control systems. However, certain technical challenges remain [

5]. In contrast, with a history of successful missions, lift modulation relies on complex avionics algorithms and control systems for continuous bank angle modulation. Despite the complexities associated with this technique, it remains better understood and established than DM techniques. Optimal aerocapture problems have often overlooked the complex engineering intricacies inherent in effecting control over these parameters. Furthermore, the influence of aerodynamic control on the resulting captured orbit is limited, and its nature is highly dependent upon the spacecraft’s state at the atmospheric interface

. Consequently, optimizing the atmospheric trajectory yields only incremental benefits to the overall mission, primarily impacting atmospheric phenomena such as heat loads.

Current optimization strategies face challenges due to highly nonlinear physics, requiring intricate nonlinear programming methods to address potential non-convexity. While Liu et al. [

2] explored optimizing nonlinear, heavily constrained re-entry trajectories by reframing the nonlinear problem as a convex one, their approach compromises generalizability, limiting its applicability. Hongwei et al. [

6] tackle the inherent non-linearity of the problem by reformulating it into a convex sub-problem. This reformulation enables the efficient resolution of the original problem through a sequence of convex optimization tasks. Nevertheless, this approach is also applied to the optimal guidance of the spacecraft during re-entry. Additionally, current strategies often employ multi-objective optimization (MOO) [

1,

2,

3,

4] for optimal re-entry trajectory problems, presenting numerical and decision-making challenges. MOO involves navigating a multi-dimensional objective space, resulting in trade-offs between objectives. The exploration of vast potential solutions and the non-convex and irregular Pareto front further complicates optimal solution searches. Selecting a single solution from a multitude of trade-offs involves considering subjective preferences, priorities, and uncertainty, requiring informed judgment, which can be challenging for algorithms due to ambiguous decision-making criteria. Moreover, the AMAT framework, developed by Girija et al. [

7] based on previous work by Girija [

8], offers a Python-based tool to assist in the design of re-entry vehicles. This framework is specifically geared towards facilitating trade-off analysis rather than optimizing the design process.

In light of these multifaceted challenges, we propose a novel framework, based around a new algorithm for the Determination of Aerocapture Successful Trajectories and Robust Optimization (D-ASTRO) algorithm. Developed within the MATLAB environment, D-ASTRO is an efficient and robust tool for rapidly analyzing and optimizing generic aerocapture missions. D-ASTRO’s unique capability lies in its ability to rapidly optimize non-thrusting, fixed angle-of-attack aerocapture-capable spacecraft and trajectories. By requiring only minimal aeroshell information and mission parameters, D-ASTRO employs a nonlinear, single-objective constrained optimization strategy to identify optimal values for the flight path angle () at the AI and the fixed ballistic coefficient () of the aeroshell.

This paper’s structure proceeds as follows: In

Section 2, we outline the equations of motion and physics models employed by D-ASTRO.

Section 3 introduces the concept of the aerocapture corridor. The optimization problem, along with novel objective functions and performance metrics, is discussed in

Section 4. The novel methodology used to rapidly compute the aerocapture corridor rapidly is covered in

Section 5 while

Section 6 focuses on the Numerical implementation and pipeline of the algorithm. Finally,

Section 7 presents the algorithm’s numerical stability and convergence properties applied to a typical Martian aerocapture mission test case, with computational considerations and performance of D-ASTRO explored in Section .

3. Aerocapture Corridor

Without employing lift or drag modulation, the flight path angle at AI and are the primary factors governing the vehicle dynamics during the atmospheric pass, thus determining the success of the aerocapture maneuver. The aerocapture corridor defines the range of and values that result in a successful maneuver. The lower limit occurs when excessive drag causes the spacecraft to collide with the surface. In contrast, the upper limit occurs when insufficient drag causes the vehicle to remain in a hyperbolic orbit. The lower limit is easily computed when the altitude reaches zero at any point in the trajectory. The spacecraft’s post-pass orbital eccentricity e determines the upper limit, where indicates a closed orbit.

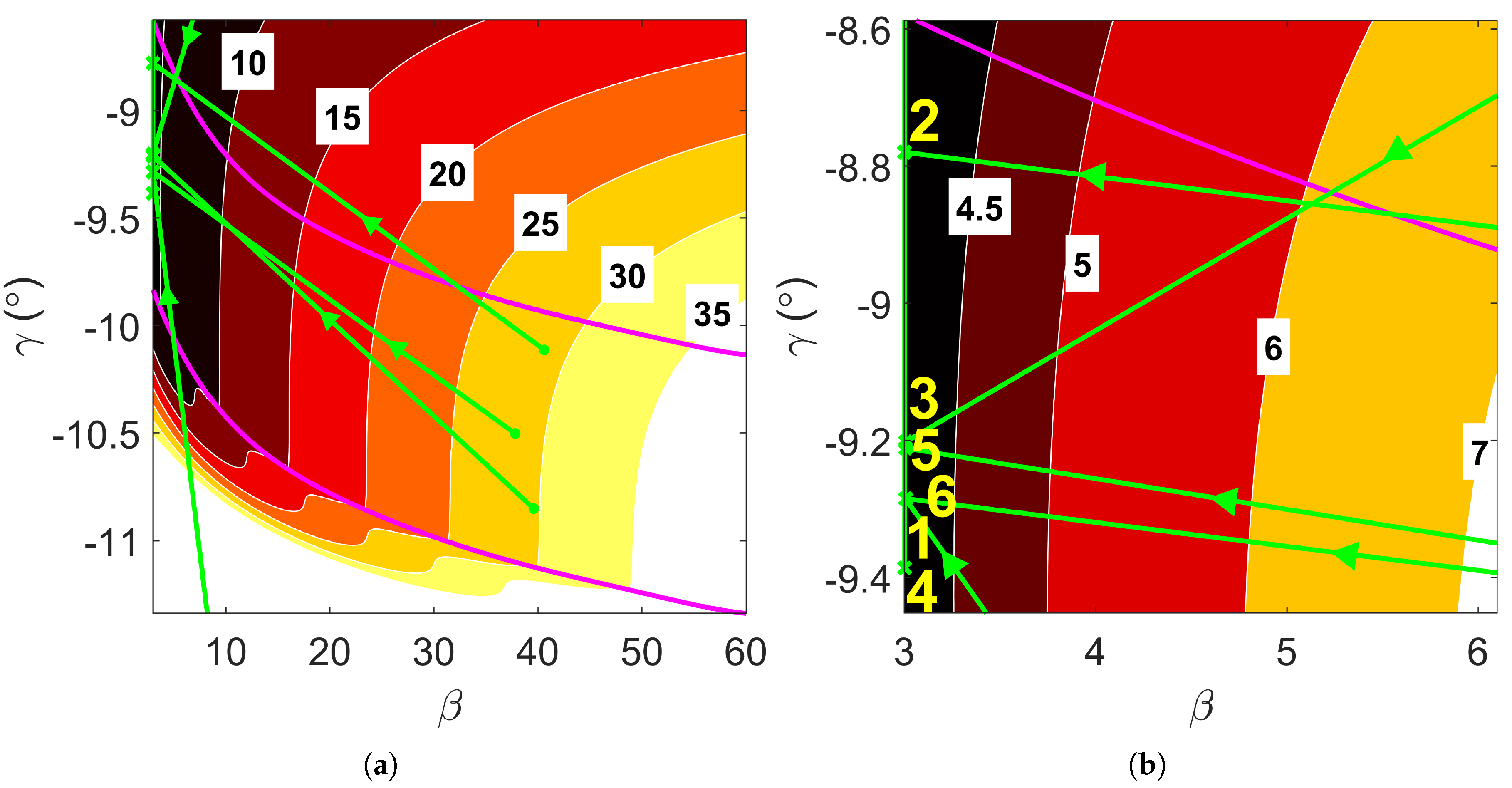

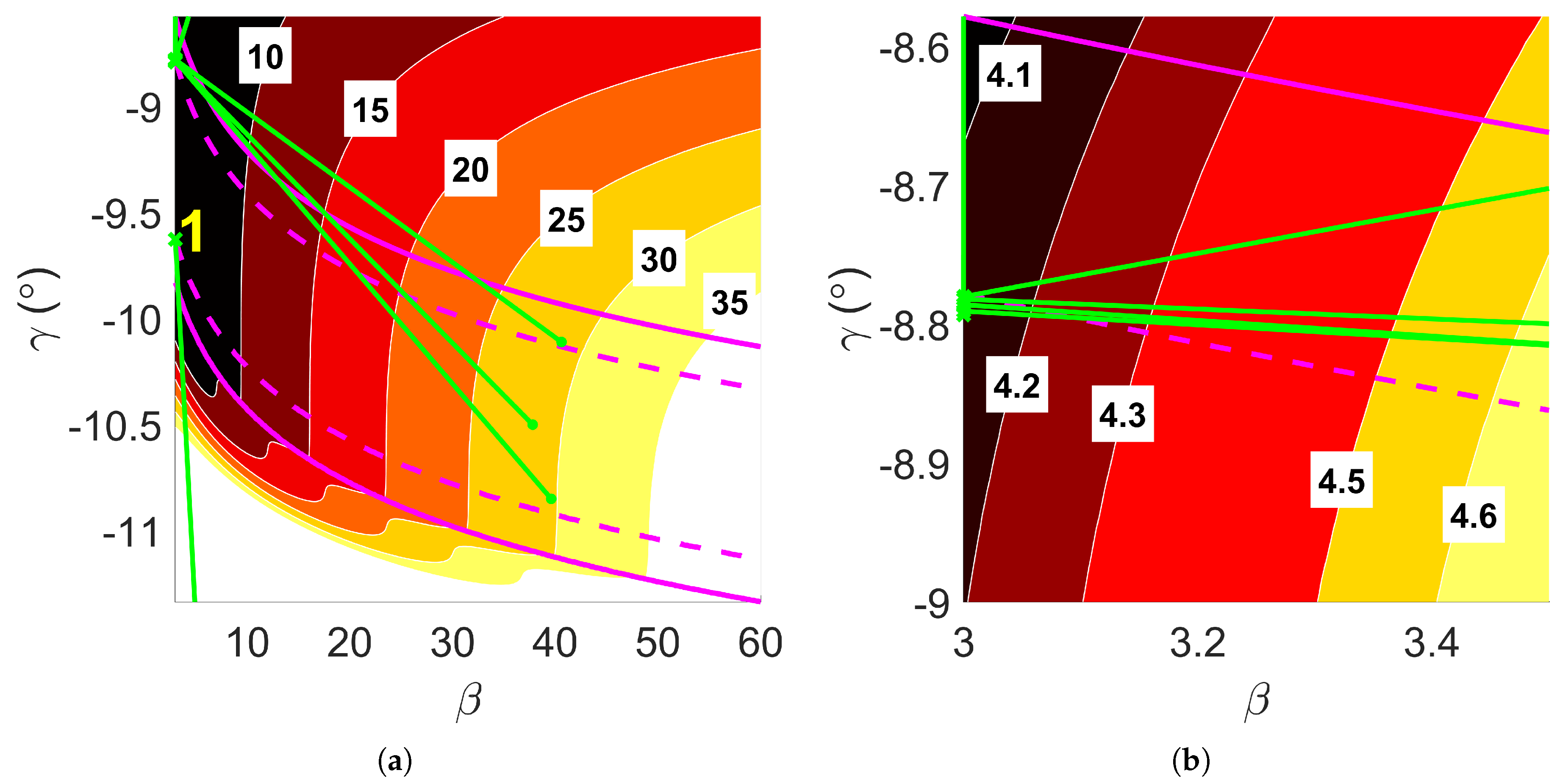

Figure 1.

Example of Martian aerocapture corridors with post-atmospheric pass orbital eccentricity contours: (a) Ballistic re-entry profile, . (b) Lifted re-entry profile,

Figure 1.

Example of Martian aerocapture corridors with post-atmospheric pass orbital eccentricity contours: (a) Ballistic re-entry profile, . (b) Lifted re-entry profile,

Figure compares the aerocapture corridors for ballistic and lifting re-entry profiles of a spacecraft approaching Mars with a hyperbolic excess velocity,

, of 3.5

. The maneuver’s success is represented by green hashing in Figure . These contours are depicted in the figures. These contours illustrate the intricate relationship among

,

, and the lift-to-drag ratio necessary for successful maneuvers. A lifting re-entry profile provides a more favorable corridor, reducing sensitivity to precise insertion attitudes. While D-ASTRO supports various re-entry profiles, this study focuses on non-zero

profiles for Martian aerocapture, utilizing a fixed value of 0.2, consistent with established norms for Martian re-entry vehicles [

18].

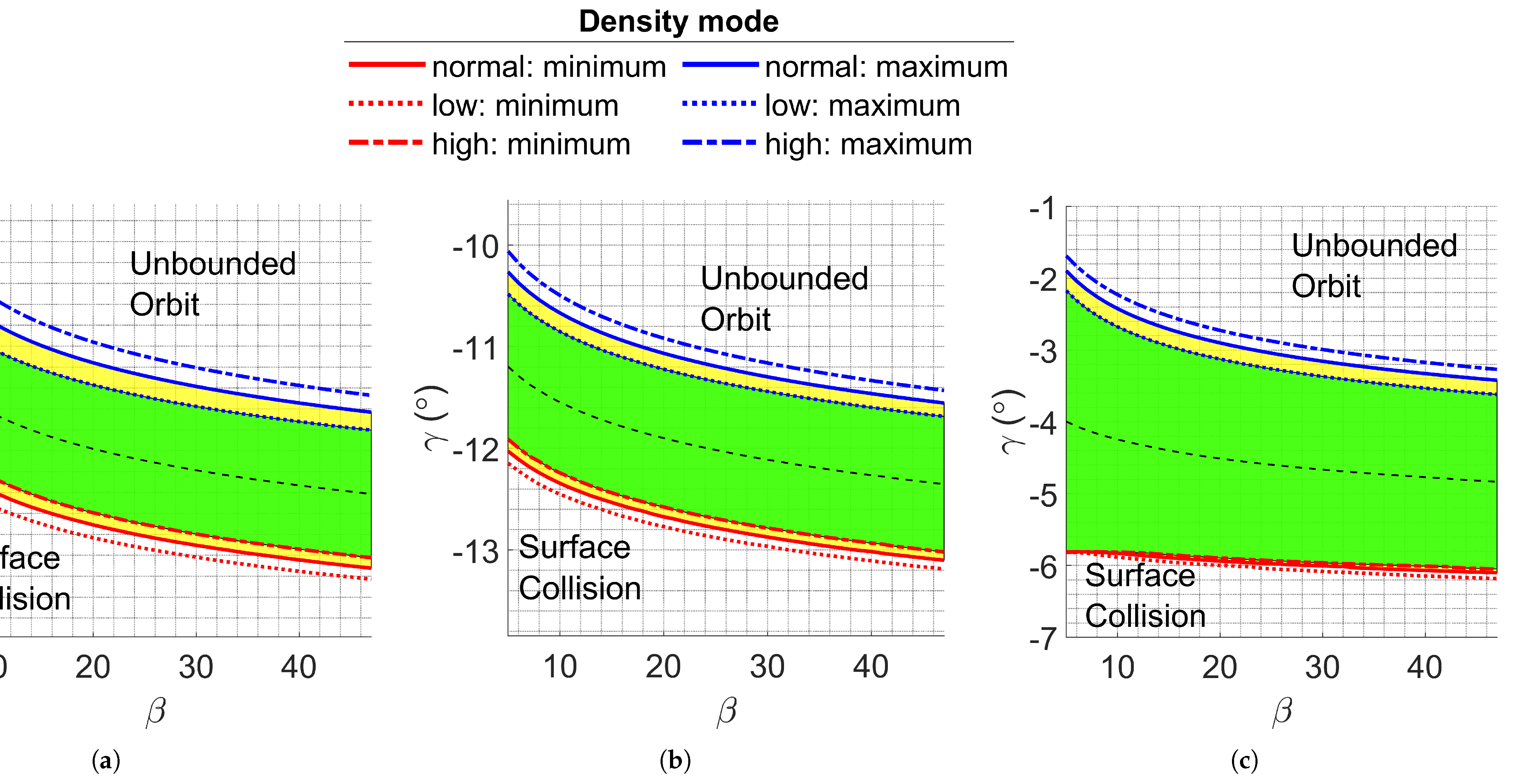

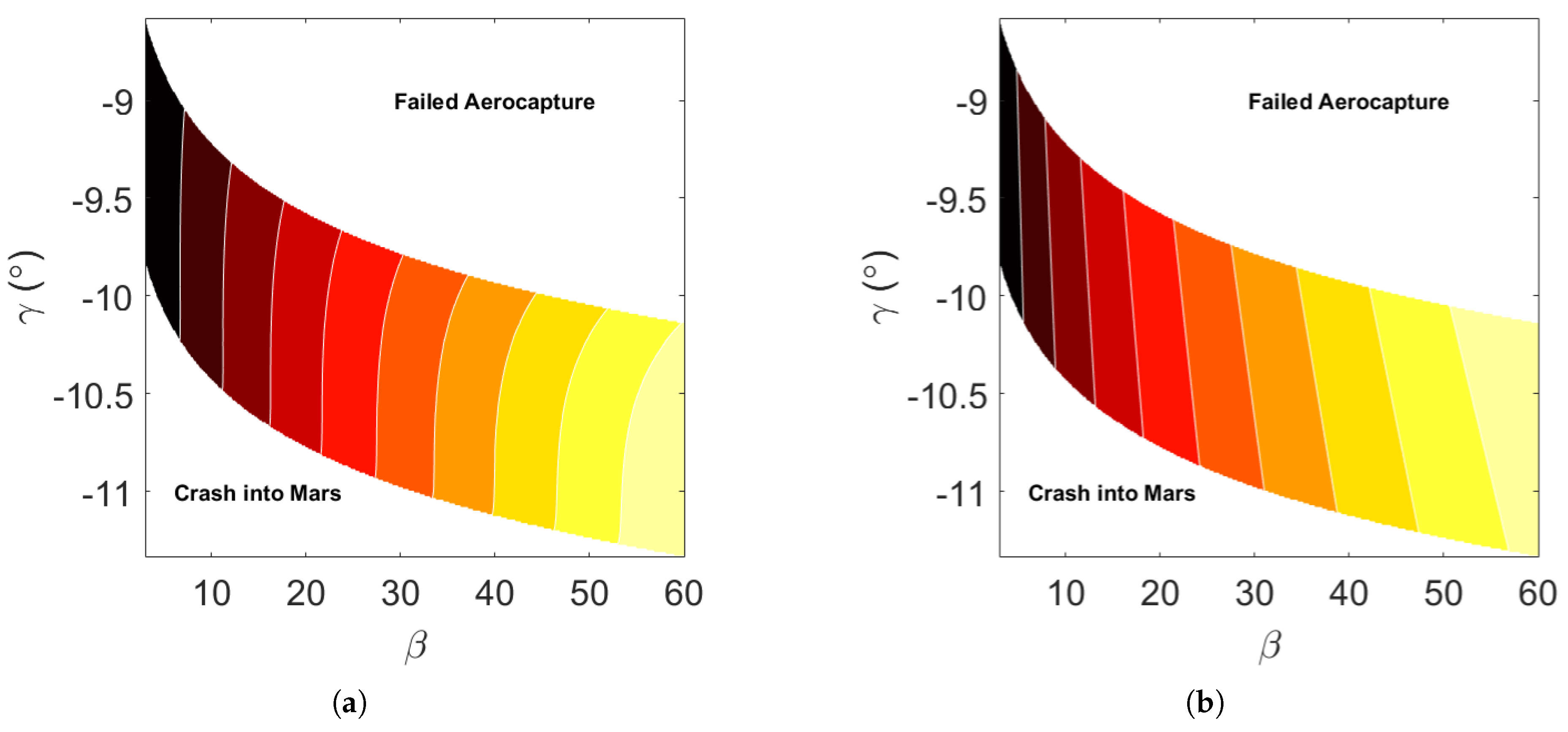

Uncertainties in atmospheric properties significantly influence the width of the aerocapture corridor. Variations in atmospheric density lead to changes in drag forces, causing the spacecraft to dissipate energy differently than expected. Near the aerocapture boundaries, even minor density fluctuations can result in maneuver failure, leading to either a hyperbolic orbit or surface collision. Two corridors are computed to establish a robust corridor: one with reduced atmospheric density and another with increased density. The `robust’ aerocapture corridor represents the intersection of these two, resulting in a narrowed corridor. These corridors are illustrated in

Figure 2, depicting Terrestrial and Martian corridors for various inbound

, where the green and yellow regions represent the robust and non-robust corridors.

5. Approximating Aerocapture Corridor Boundaries

The primary challenge in aerocapture optimization lies in handling the nonlinear constraints introduced by and in Problem P1. Current optimization techniques necessitate computing and at each internal candidate point, significantly increasing execution time despite efficient search algorithms. This is quantitatively characterized in Section .

Multiple aerocapture corridors for Martian and Terrestrial missions with various hyperbolic approach orbits were analyzed.

Figure 2 displays three examined corridors, with the upper boundary exhibiting an exponential trend across all cases, while the lower boundary differs from this trend in some scenarios. This discrepancy is imparted by the differing atmospheric structures of the planets at low altitudes. Several candidate fundamental functions were considered to rapidly map

to

and

, including exponential and polynomial curves.

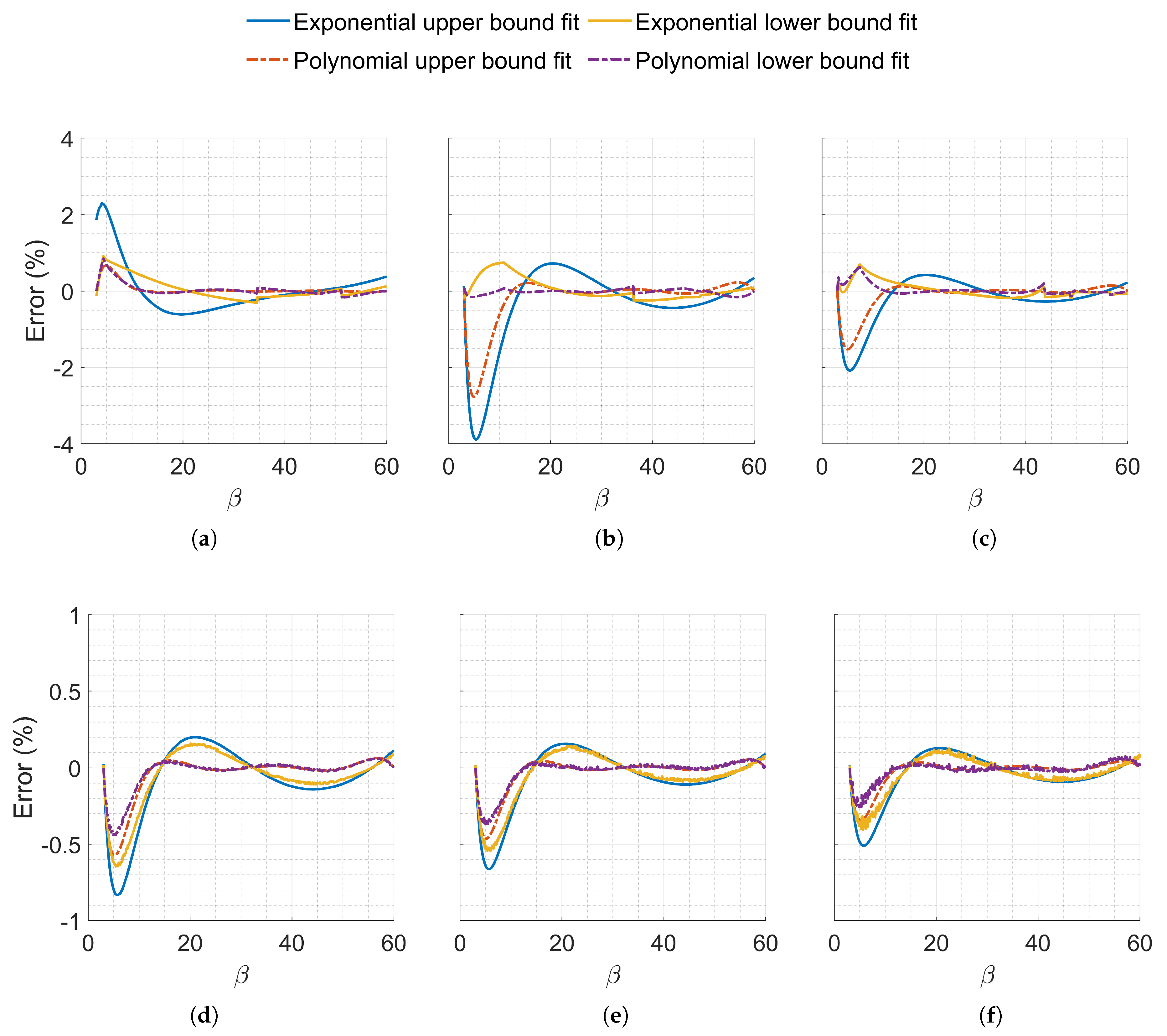

Initial testing revealed limitations of a primary exponential curve (

in Equation (16), leading to the adoption of a second-degree exponential fit (

), significantly enhancing predictive accuracy with error bounded by

and

for Terrestrial and Martian aerocaptures respectively. Additionally, sixth-degree polynomial curves were examined due to the potential flat nature of some boundaries. As illustrated by

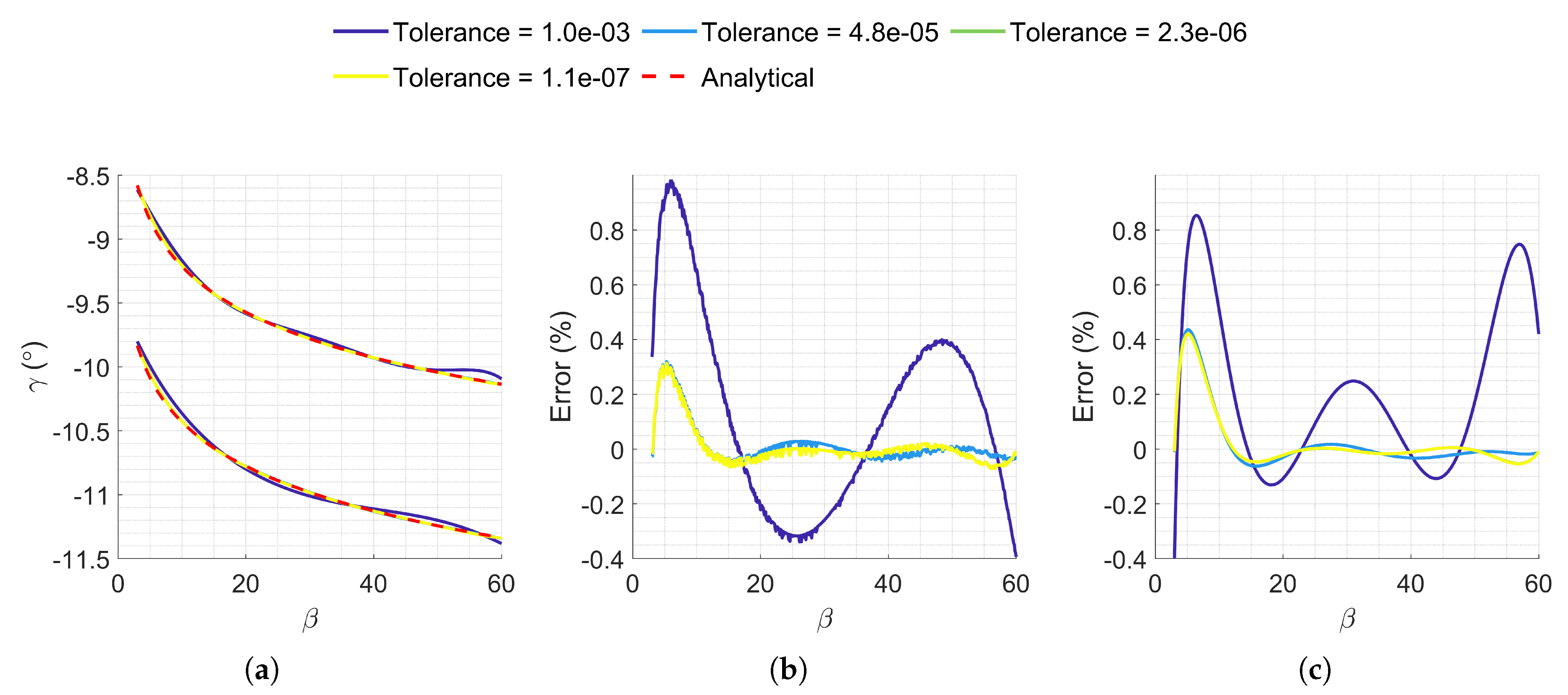

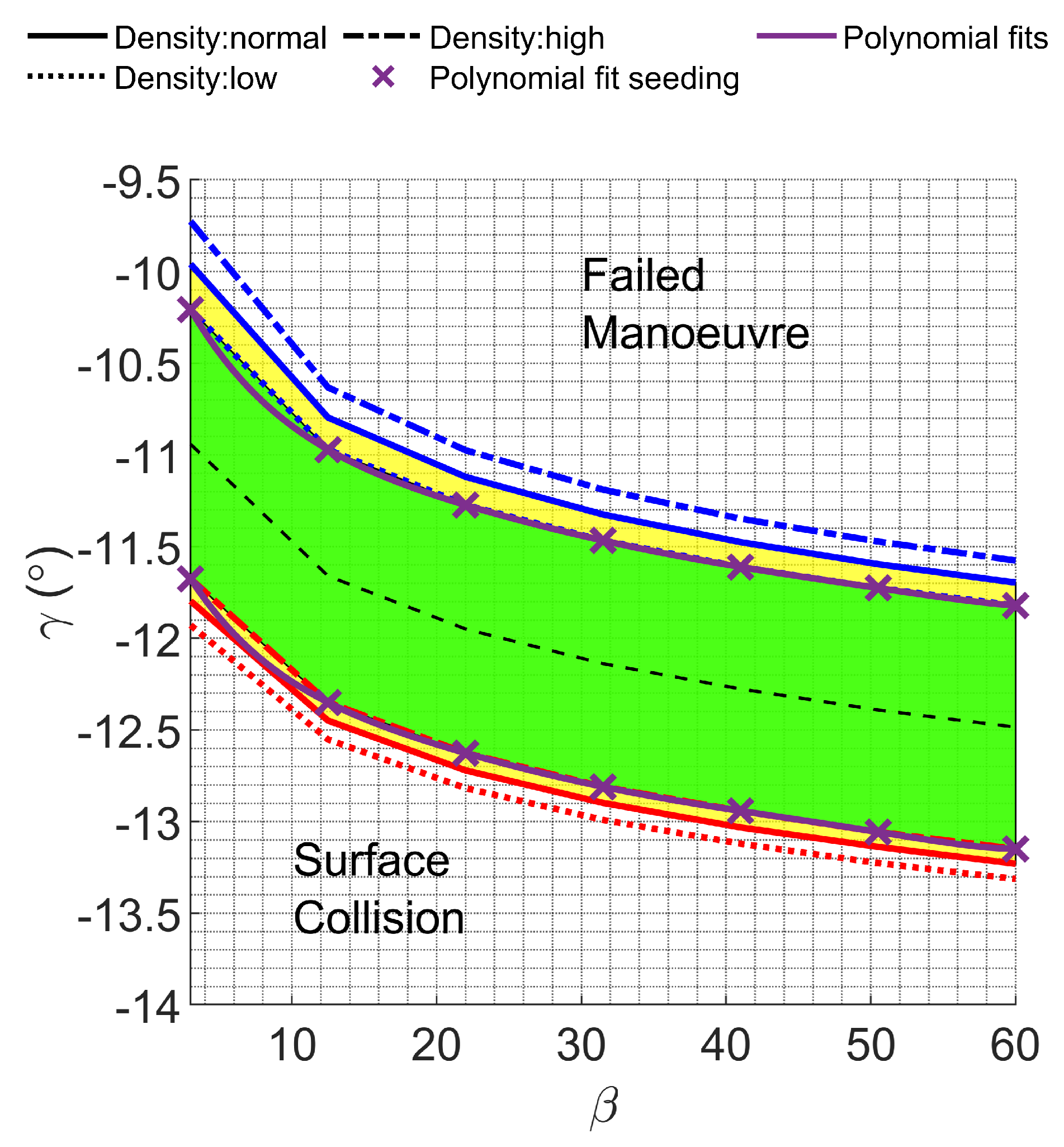

Figure 3, the polynomial curves resulted in excellent predictive capabilities, exceeding the former’s accuracy.

Exploration into the minimum number of points required for accurate fitting demonstrated that the accuracy of the fits was very sensitive to the selected fitting points. Randomly selecting seven points within the interest

range demonstrated poor fit accuracy, as illustrated by Figure A1. However, when the fitting points were evenly distributed across the range, both fits exhibited increased accuracy with fewer fitting points. Specifically, fitting the sixth-degree polynomial with seven linearly spaced points proved to capture boundaries accurately, showcasing superior capabilities in approximating flat boundaries, resulting in approximations within

and

for Terrestrial and Martian maneuvers, respectively.

Figure 3 illustrates the error between the actual boundary and the proposed fits, comparing the second-degree exponential fit with the sixth-degree polynomial fit, both fitted with 7 linearly spaced points.

9. Conclusions

This study presents a novel framework for the Determinations of Aerocapture Successful Trajectories and Robust Optimization (D-ASTRO) for the rapid optimization of aerocapture-capable spacecraft geometry and trans-atmospheric trajectory. D-ASTRO robustly identifies globally optimal trajectories by optimizing the flight path angle () at the atmospheric interface and ballistic coefficient () for specific target orbits and design requirements. This approach aims to assist mission designers in streamlining the architecture of aerocapture-capable spacecraft, facilitating the integration of aerocapture maneuvers into deep space exploration missions.

The proposed algorithm employs sixth-order polynomials to define the aerocapture corridor boundaries precisely, obviating the need for a double binary search at each candidate point to assess feasibility. This method substantially enhances computational efficiency and reduces execution time. While this approach necessitates a higher number of function evaluations to reach convergence, the execution time per function call is markedly reduced, typically around per evaluation. In contrast, implementing a double binary search at each candidate point results in an execution time per function call ranging from 300 to .

Departing from prevalent multi-objective optimization (MOO) paradigms, the D-ASTRO algorithm introduces an innovative single-objective constrained optimization approach, demonstrating clear superiority through direct comparison. By recognizing that performance metrics are bounded within aerocapture constraints, D-ASTRO incorporates feature normalization, effectively integrating knowledge of metric ranges into the optimization framework. This method accelerates gradient descent optimizers and enhances convergence to global optima. Furthermore, this modification allows for a representative trade-off analysis, where the weight vectors appropriately impose the corresponding impact of the design driver on cost.

A Martian aerocapture test mission showcases D-ASTRO’s capabilities and validates the feasibility of the proposed solutions. D-ASTRO successfully determines the optimal geometries and trajectories for various mission criteria. Optimal points attained through D-ASTRO exhibit lower costs relative to multi-objective optimal trajectories, primarily driven by reduced fuel requirements and volumetric considerations. However, this is achieved at the expense of augmented heat loads and peak heat transfers for the overall optimal trajectory. The algorithm consistently converges towards global minima, demonstrating enhanced convergence properties and numerical stability even under challenging initial conditions. This underscores its effectiveness in addressing complex optimization challenges within aerocapture trajectory design.

While the analysis conducted in this study has provided valuable insights, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations and outline potential directions for future research. One significant limitation lies in the assumption of a fixed lift-to-drag ratio (L/D) of 0.2, tailored for Martian re-entry missions. To enhance the algorithm’s applicability, future iterations should explore the optimization of L/D as a variable, thereby broadening its utility. Additionally, the assumed knowledge of the spacecraft’s state at orbital insertion presents a challenge, as these parameters are intricately linked to the design of the interplanetary insertion trajectory. Future research endeavors may involve coupling D-ASTRO with an interplanetary trajectory design tool to address this. This coupling would enable iterative refinement, ensuring coherence between the optimization of aerocapture trajectories and the design of the broader mission architecture. Through such enhancements, the algorithm can evolve to better meet the demands of complex aerocapture missions in the dynamic realm of space exploration.

Figure 2.

Martian and Terrestrial aerocapture corridors for multiple hyperbolic excess velocities, . The polynomial fits for low, mean, and high-density corridor boundaries are shown: (a) Martian aerocapture corridor with . (b) Martian aerocapture corridor with . (c) Terrestrial aerocapture corridor with

Figure 2.

Martian and Terrestrial aerocapture corridors for multiple hyperbolic excess velocities, . The polynomial fits for low, mean, and high-density corridor boundaries are shown: (a) Martian aerocapture corridor with . (b) Martian aerocapture corridor with . (c) Terrestrial aerocapture corridor with

Figure 3.

Percentage error between finely discretized corridor limits (570 points) and computed values using exponential and polynomial constructed from 7 points. (a) Earth, . (b) Earth, . (c) Earth, . (d) Mars, . (e) Mars, . (f) Mars, .

Figure 3.

Percentage error between finely discretized corridor limits (570 points) and computed values using exponential and polynomial constructed from 7 points. (a) Earth, . (b) Earth, . (c) Earth, . (d) Mars, . (e) Mars, . (f) Mars, .

Figure 4.

Coarse robust Martian aerocapture corridor for

used to compute normalization quantities listed in

Table 1 and sixth-degree polynomial fits.

Figure 4.

Coarse robust Martian aerocapture corridor for

used to compute normalization quantities listed in

Table 1 and sixth-degree polynomial fits.

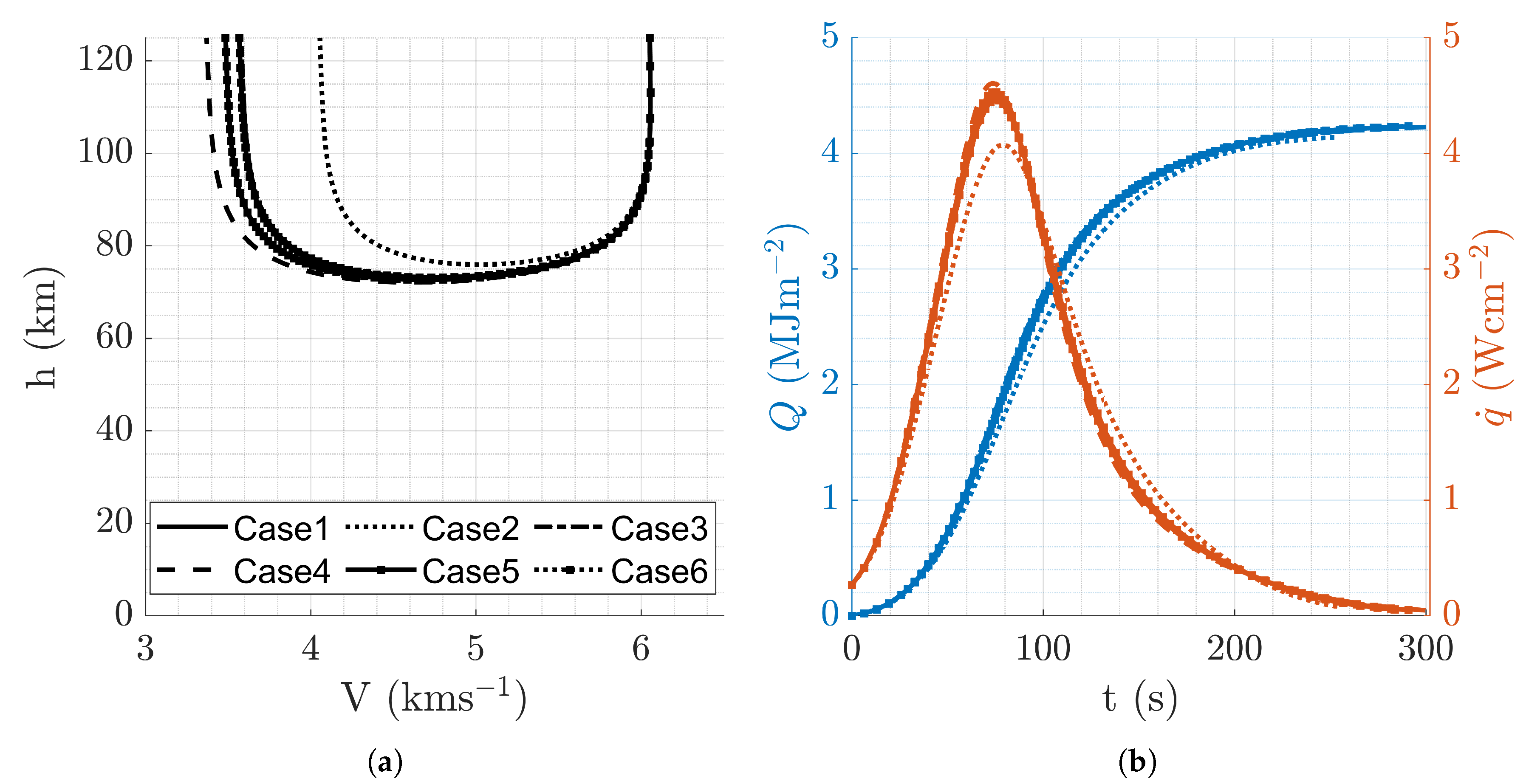

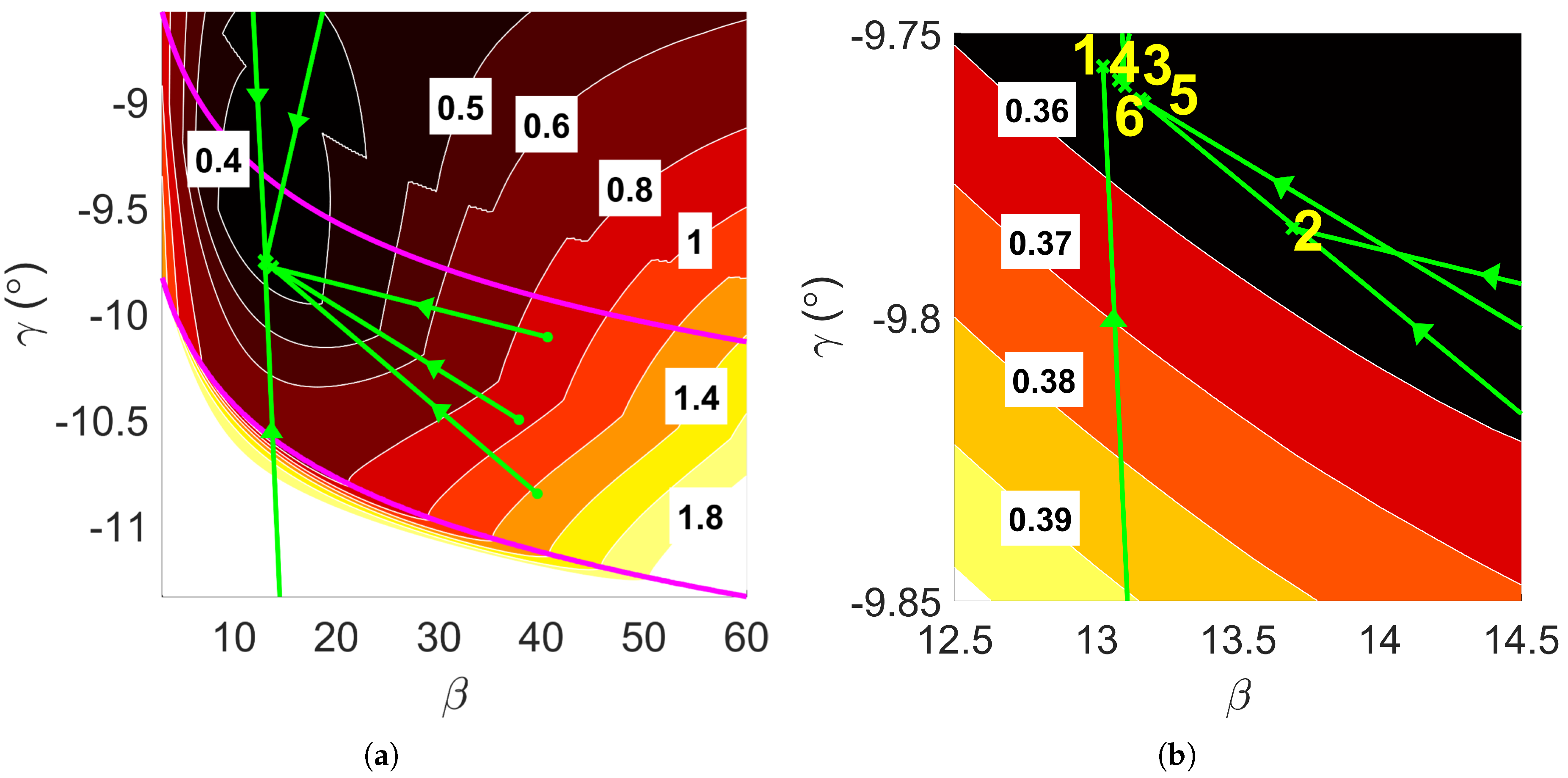

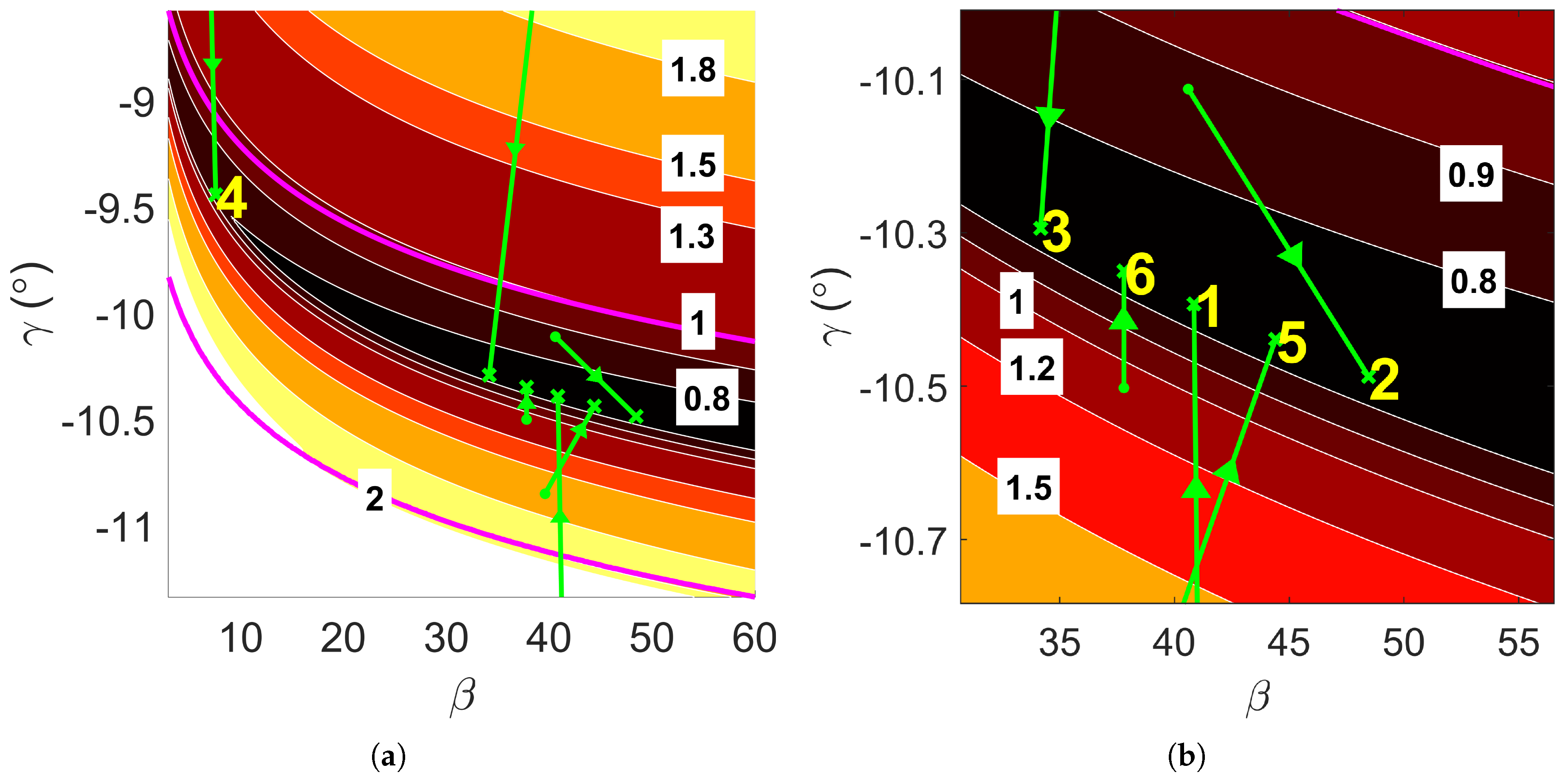

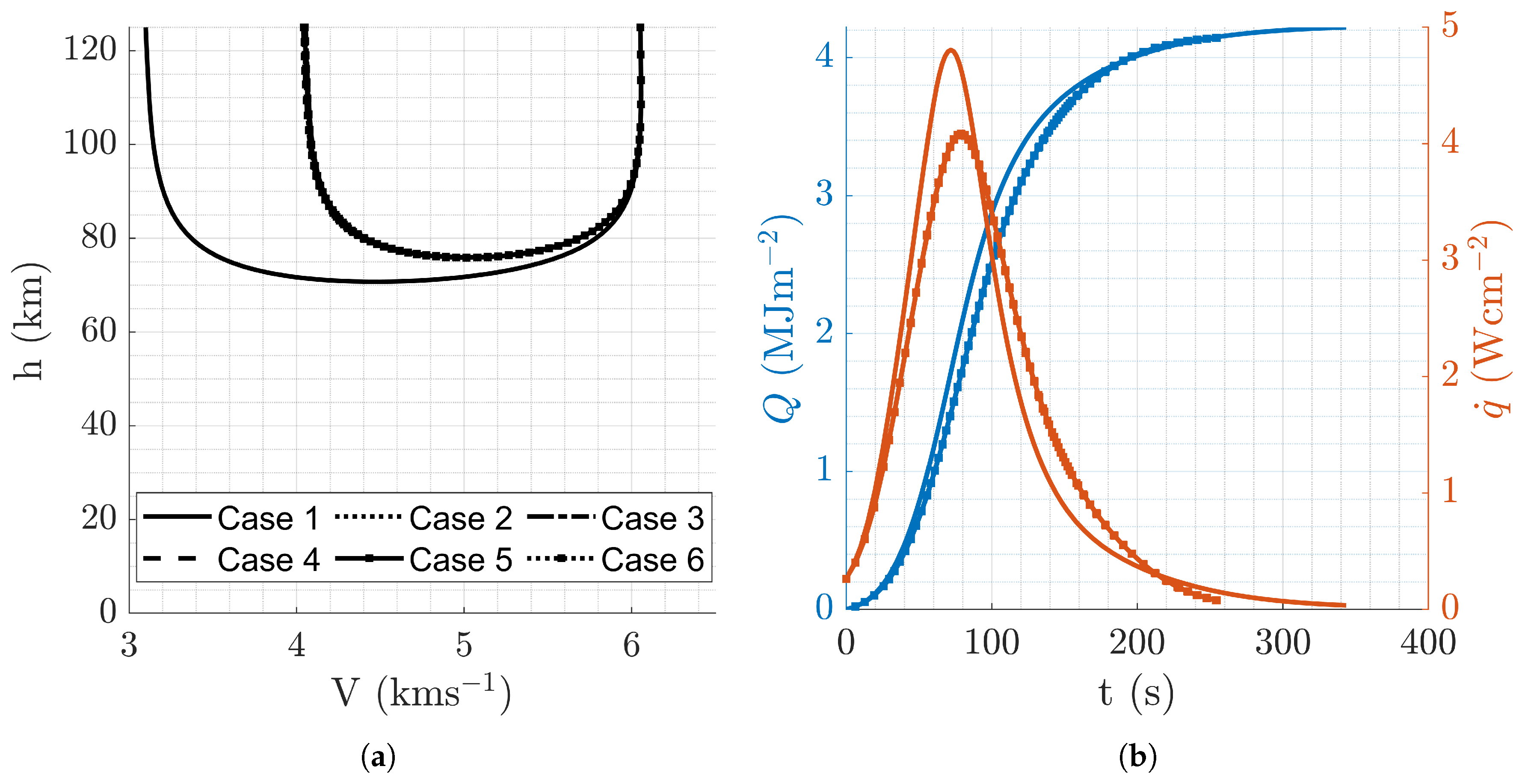

Figure 5.

Convergence property of D-ASTRO for overall optimal mission design, , with magenta lines delineating the boundaries of the aerocapture corridor. (a) Convergence of to . (b) Zoom into global minimum region

Figure 5.

Convergence property of D-ASTRO for overall optimal mission design, , with magenta lines delineating the boundaries of the aerocapture corridor. (a) Convergence of to . (b) Zoom into global minimum region

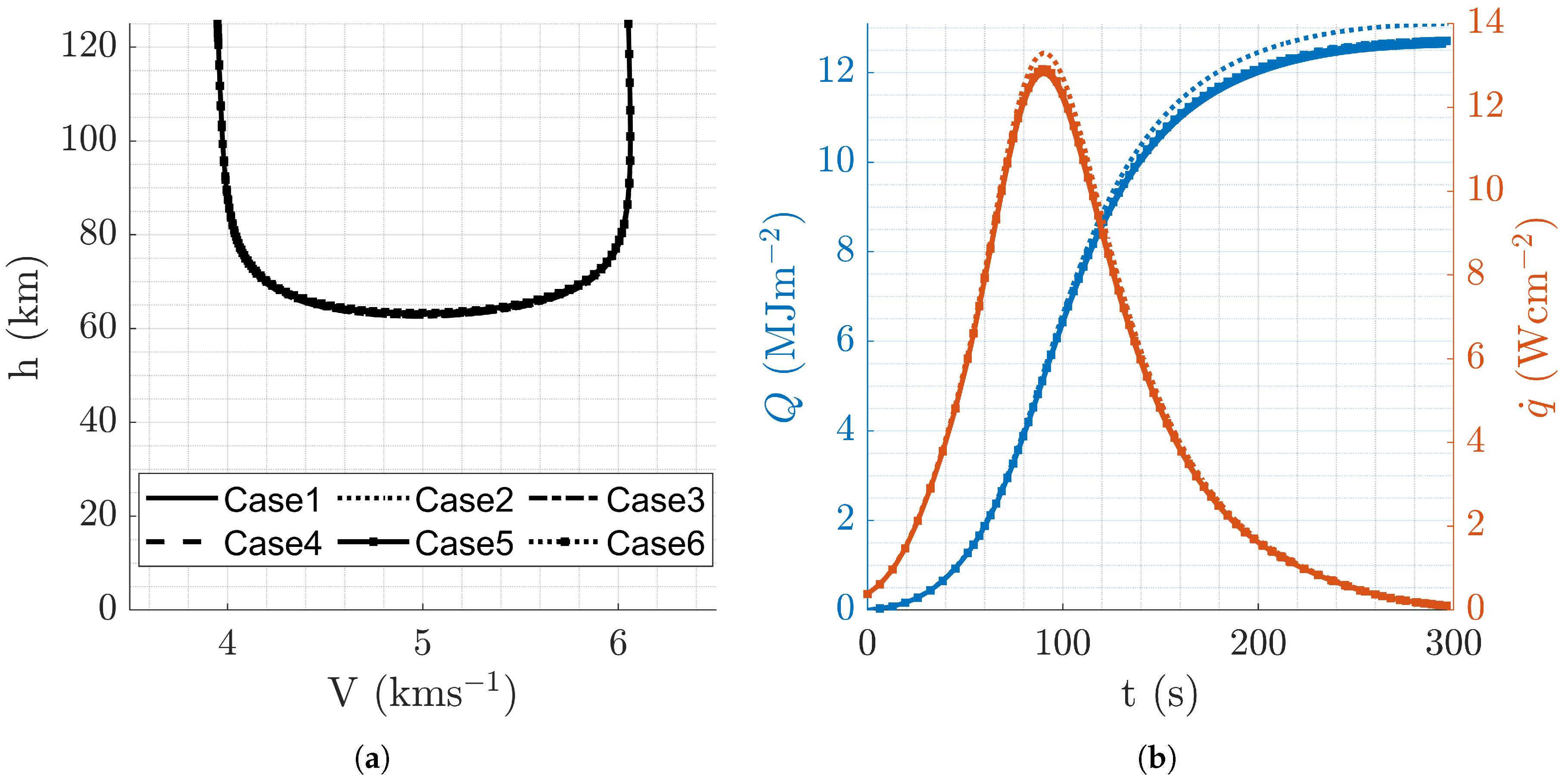

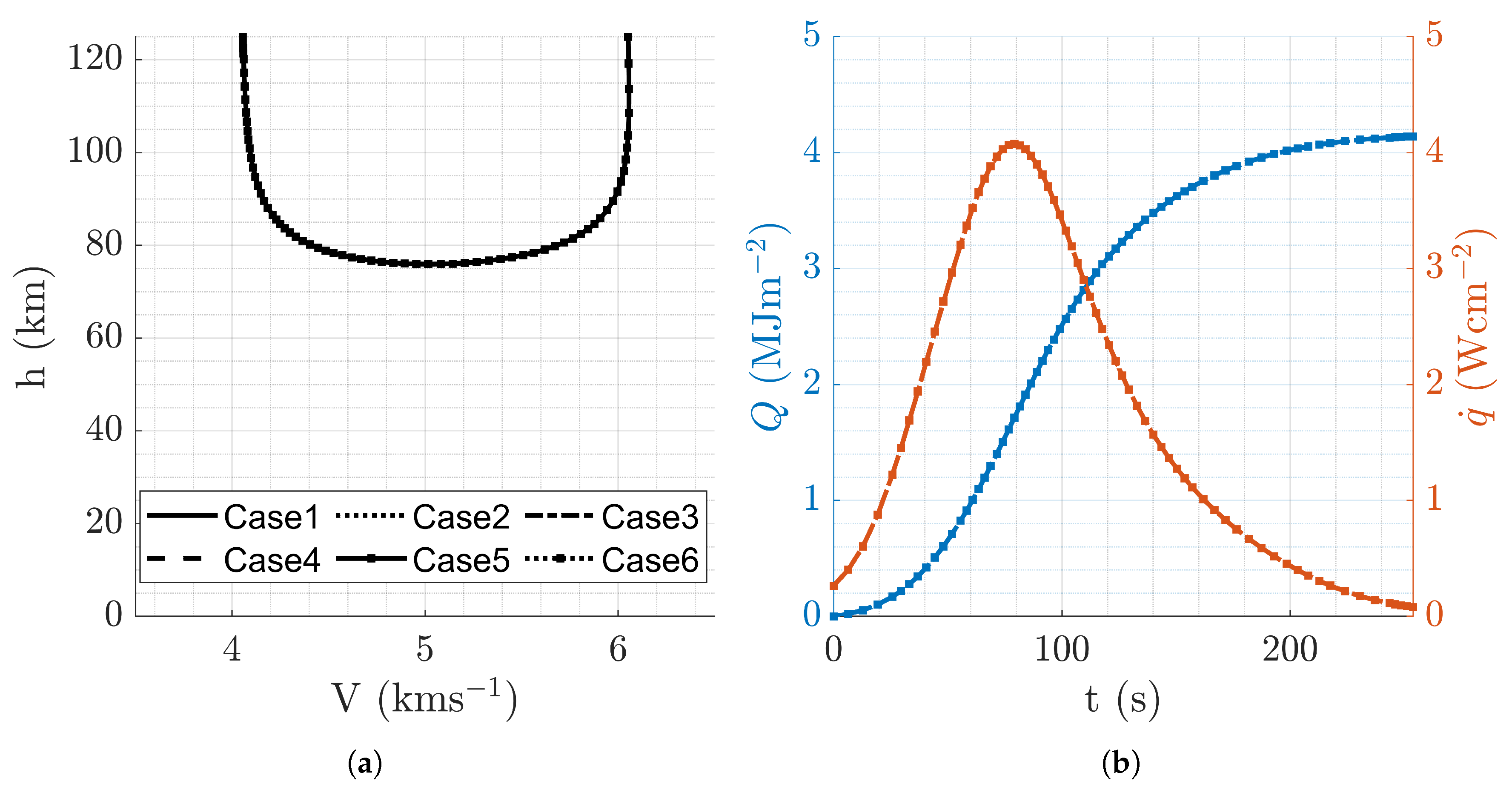

Figure 6.

Aerocapture trajectory profiles resulting from overall optimal mission design, .

(a) Altitude vs velocity. (b) Altitude and vs time.

Figure 6.

Aerocapture trajectory profiles resulting from overall optimal mission design, .

(a) Altitude vs velocity. (b) Altitude and vs time.

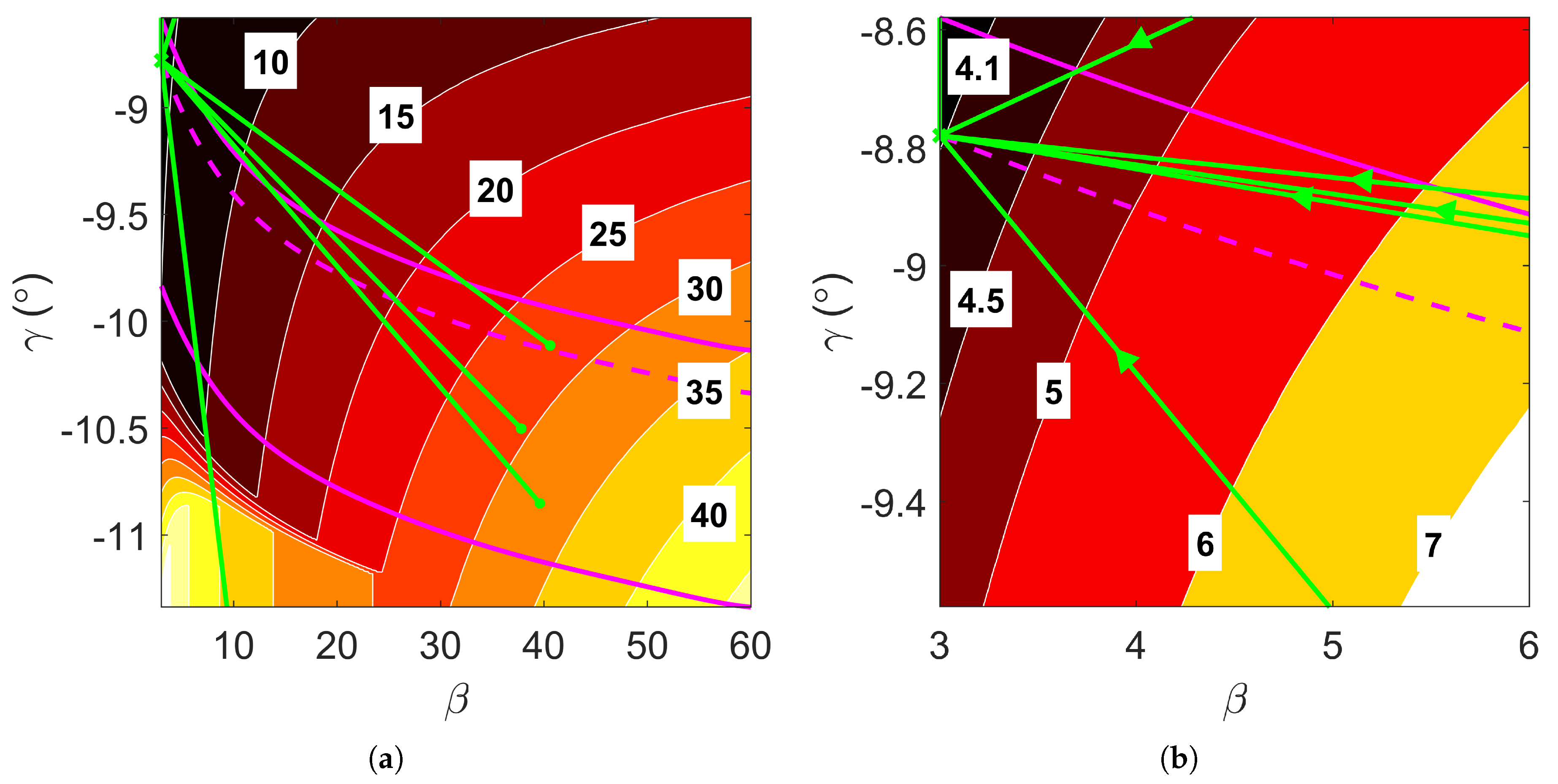

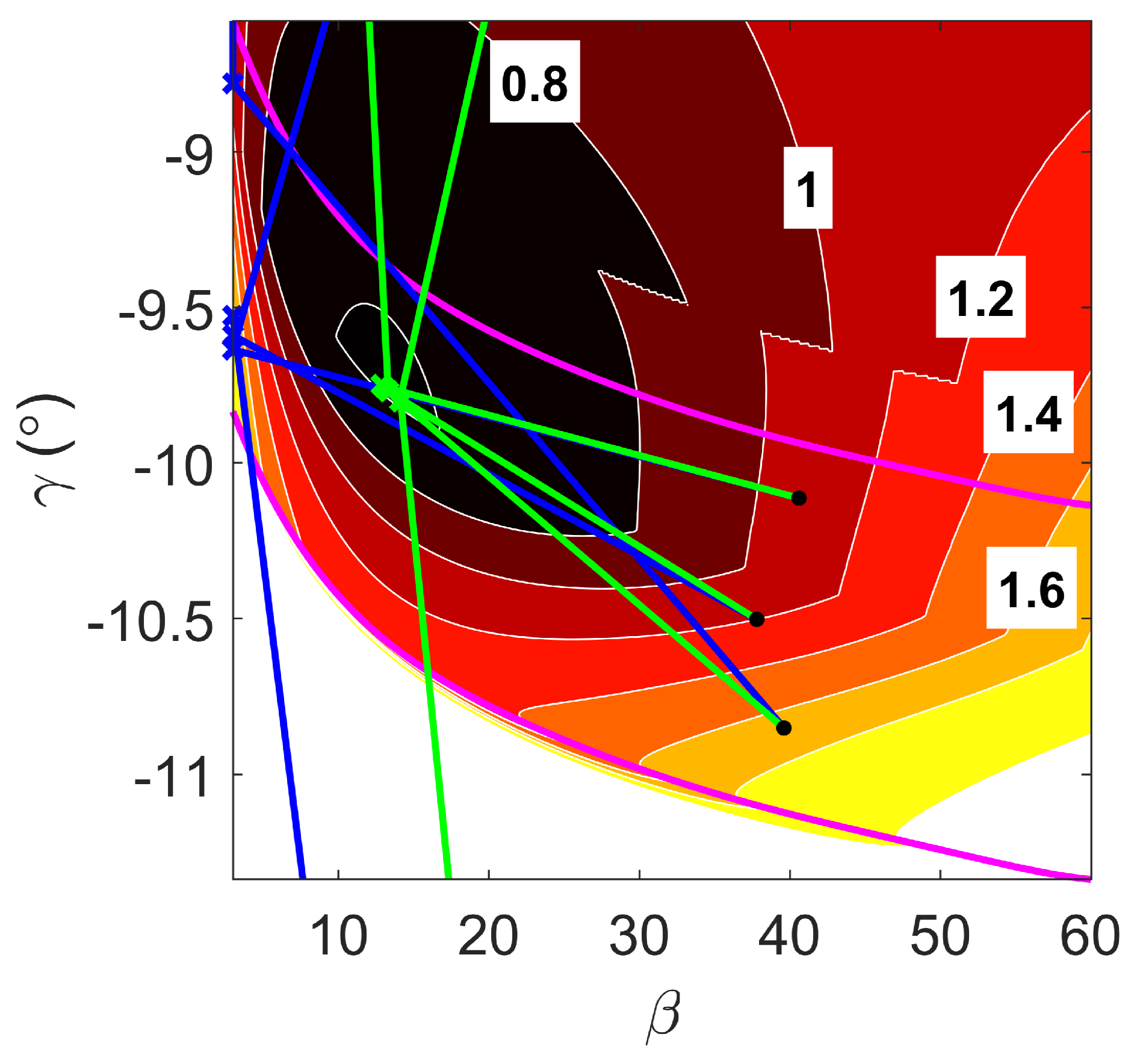

Figure 7.

Convergence property of D-ASTRO for minimum fuel mission design, , with magenta lines delineating the boundaries of the aerocapture corridor. (a) Convergence of to . (b) Zoom into global minimum region.

Figure 7.

Convergence property of D-ASTRO for minimum fuel mission design, , with magenta lines delineating the boundaries of the aerocapture corridor. (a) Convergence of to . (b) Zoom into global minimum region.

Figure 8.

contours for minimal fuel trajectory neglecting plane change maneuvers, , and .

Figure 8.

contours for minimal fuel trajectory neglecting plane change maneuvers, , and .

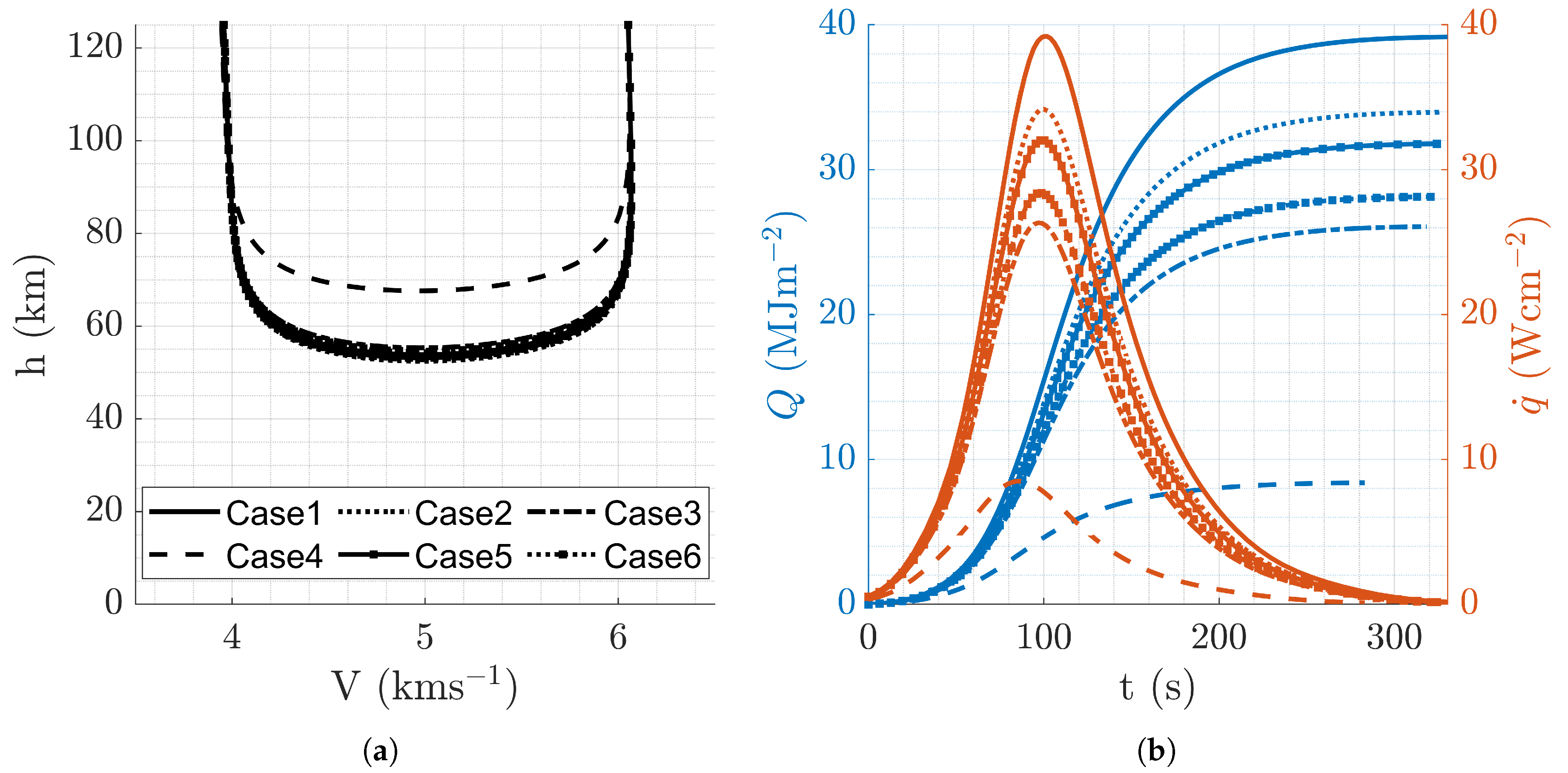

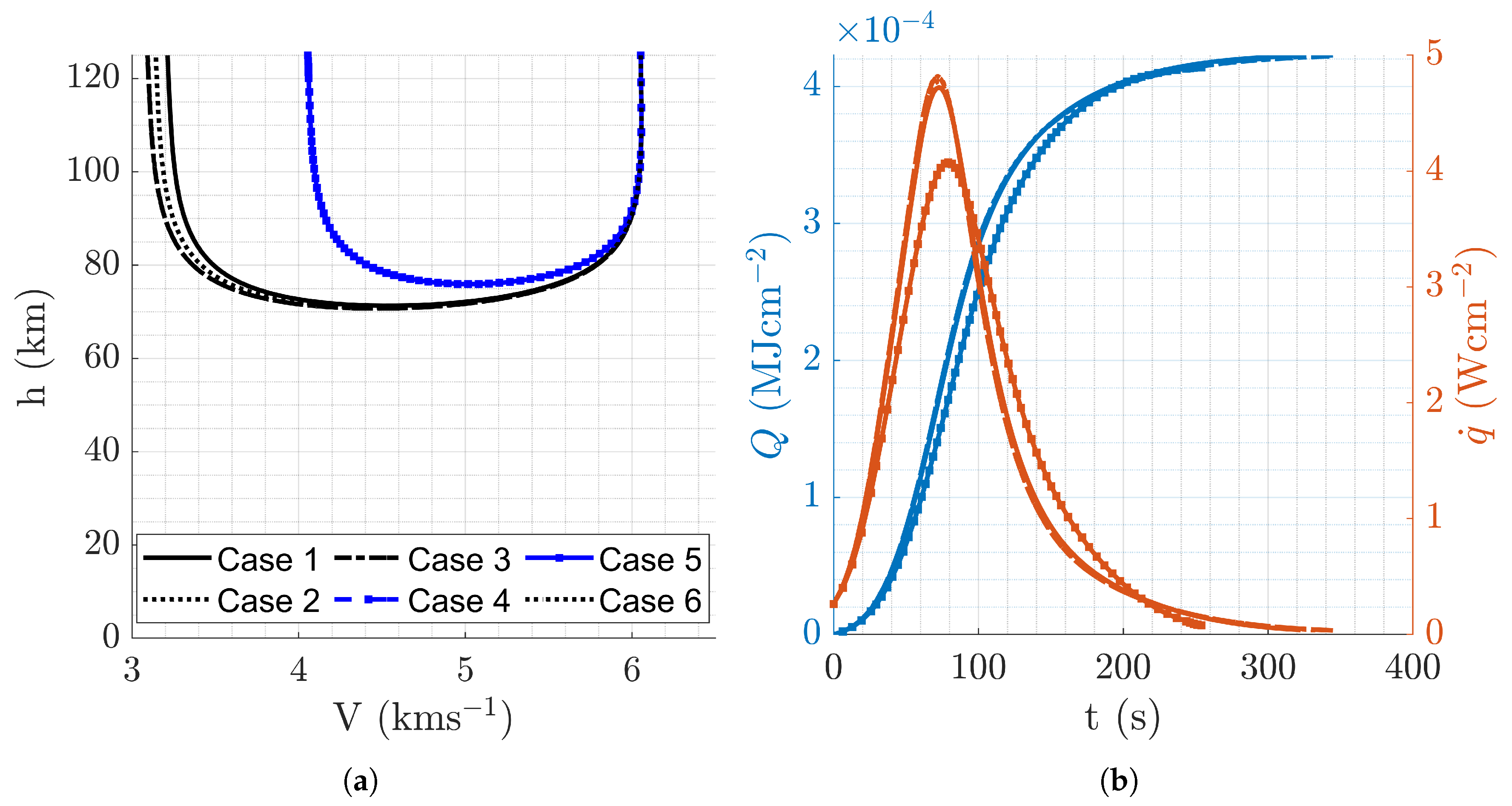

Figure 9.

Aerocapture trajectory profiles resulting from minimal fuel mission design, .

(a) Altitude vs velocity. (b) Altitude and vs time.

Figure 9.

Aerocapture trajectory profiles resulting from minimal fuel mission design, .

(a) Altitude vs velocity. (b) Altitude and vs time.

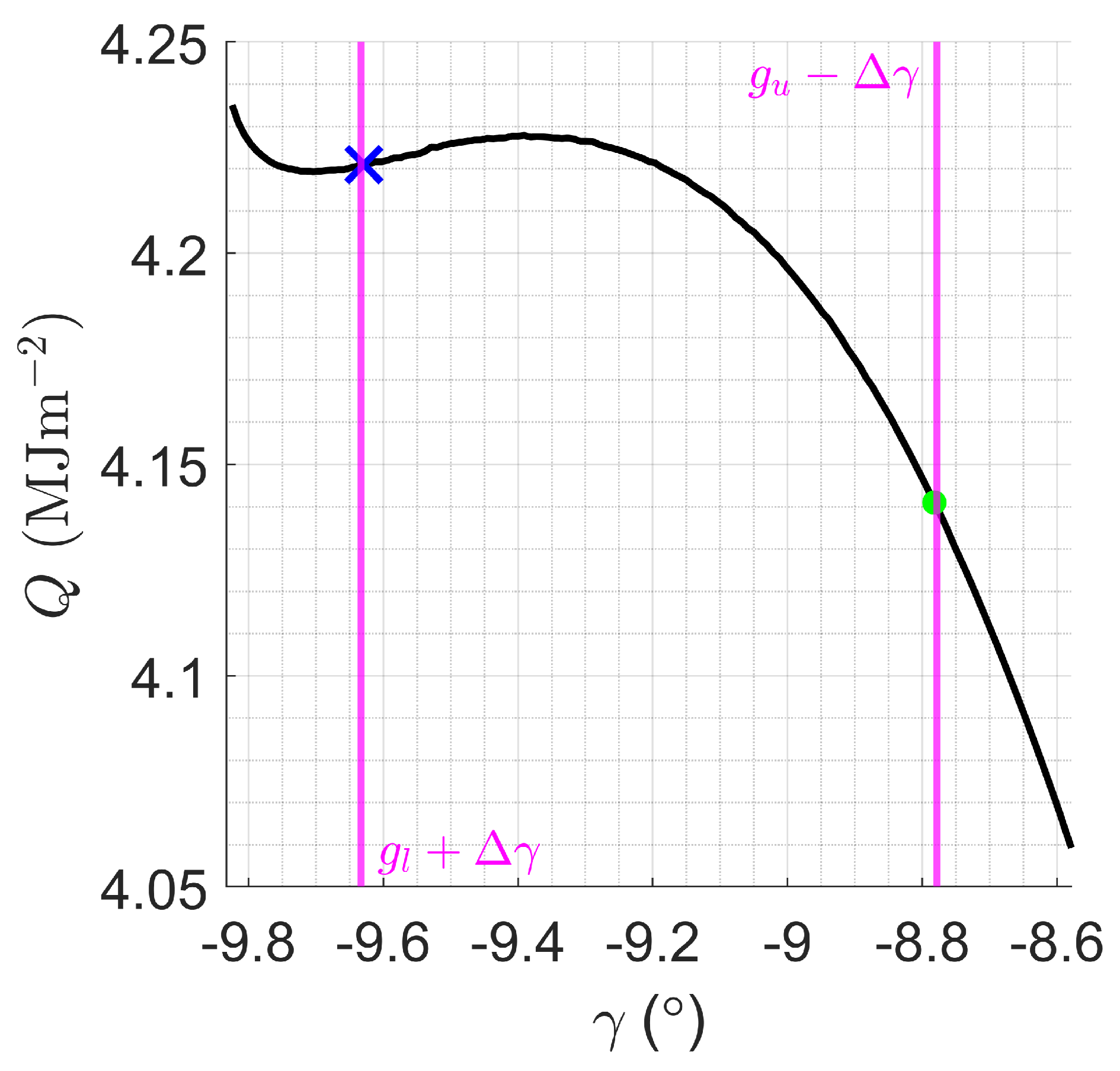

Figure 10.

Convergence property of D-ASTRO for minimum heat load mission design, , with magenta lines delineating the boundaries of the aerocapture corridor. (a) Convergence of to . (b) Zoom into global minimum region.

Figure 10.

Convergence property of D-ASTRO for minimum heat load mission design, , with magenta lines delineating the boundaries of the aerocapture corridor. (a) Convergence of to . (b) Zoom into global minimum region.

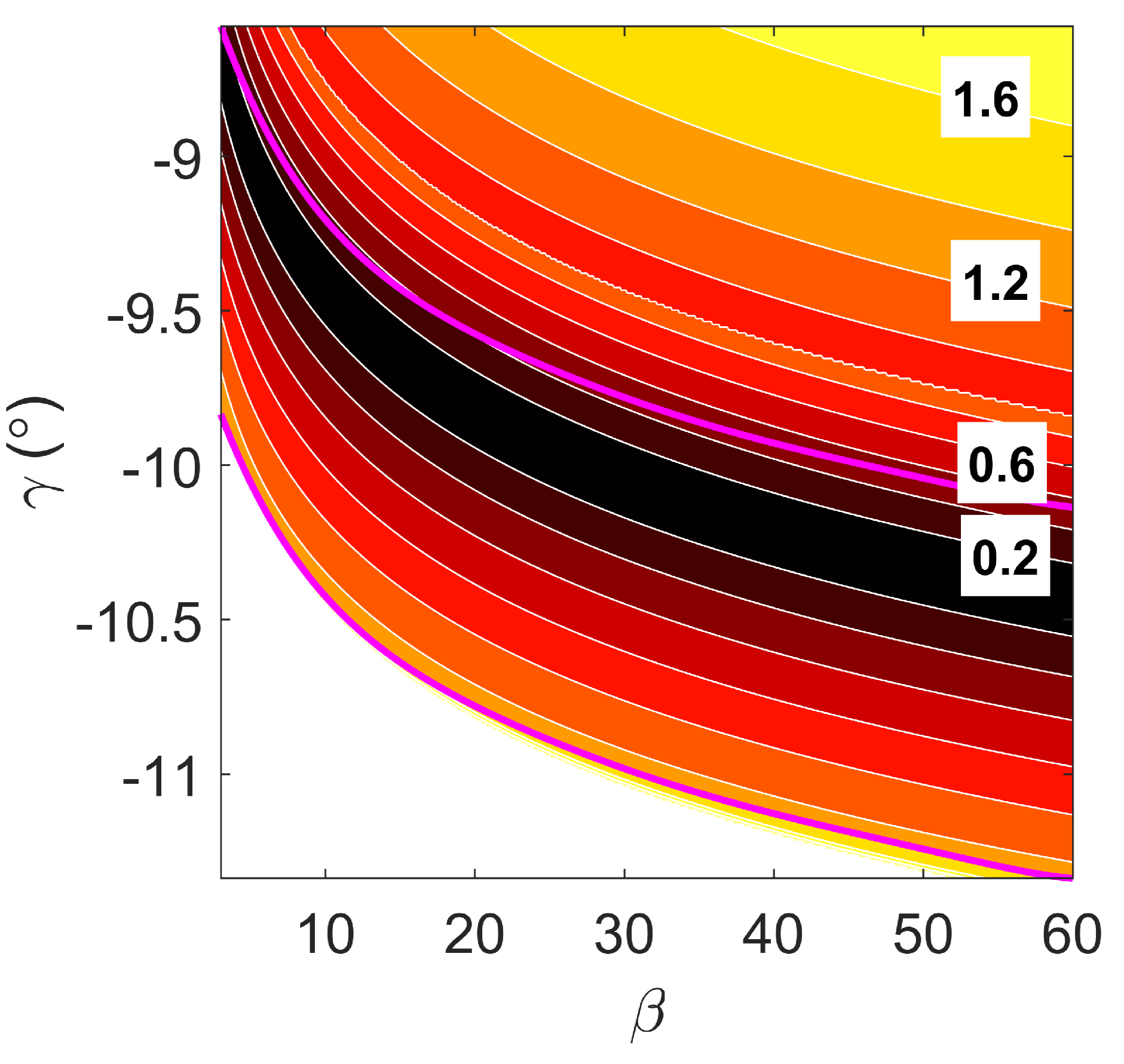

Figure 11.

Normalized heat load,

. (

a) Complete trajectory analysis. (

b) Predicted by Equation

16.

Figure 11.

Normalized heat load,

. (

a) Complete trajectory analysis. (

b) Predicted by Equation

16.

Figure 12.

Aerocapture trajectory profiles resulting from minimal heat load mission design,

. (a) Altitude vs velocity. (b) Altitude and vs time.

Figure 12.

Aerocapture trajectory profiles resulting from minimal heat load mission design,

. (a) Altitude vs velocity. (b) Altitude and vs time.

Figure 13.

Convergence property of D-ASTRO for minimum peak heating rate mission design, , with magenta lines delineating the boundaries of the aerocapture corridor. (a) Convergence of to . (b) Zoom into global minimum region.

Figure 13.

Convergence property of D-ASTRO for minimum peak heating rate mission design, , with magenta lines delineating the boundaries of the aerocapture corridor. (a) Convergence of to . (b) Zoom into global minimum region.

Figure 14.

Aerocapture trajectory profiles resulting from minimal peak heating rate mission design, . (a) Altitude vs velocity. (b) Altitude and vs time.

Figure 14.

Aerocapture trajectory profiles resulting from minimal peak heating rate mission design, . (a) Altitude vs velocity. (b) Altitude and vs time.

Figure 15.

Convergence property of MOO strategy for overall optimal mission design (blue) compared with D-ASTRO (green), , with magenta lines delineating the aerocapture boundaries.

Figure 15.

Convergence property of MOO strategy for overall optimal mission design (blue) compared with D-ASTRO (green), , with magenta lines delineating the aerocapture boundaries.

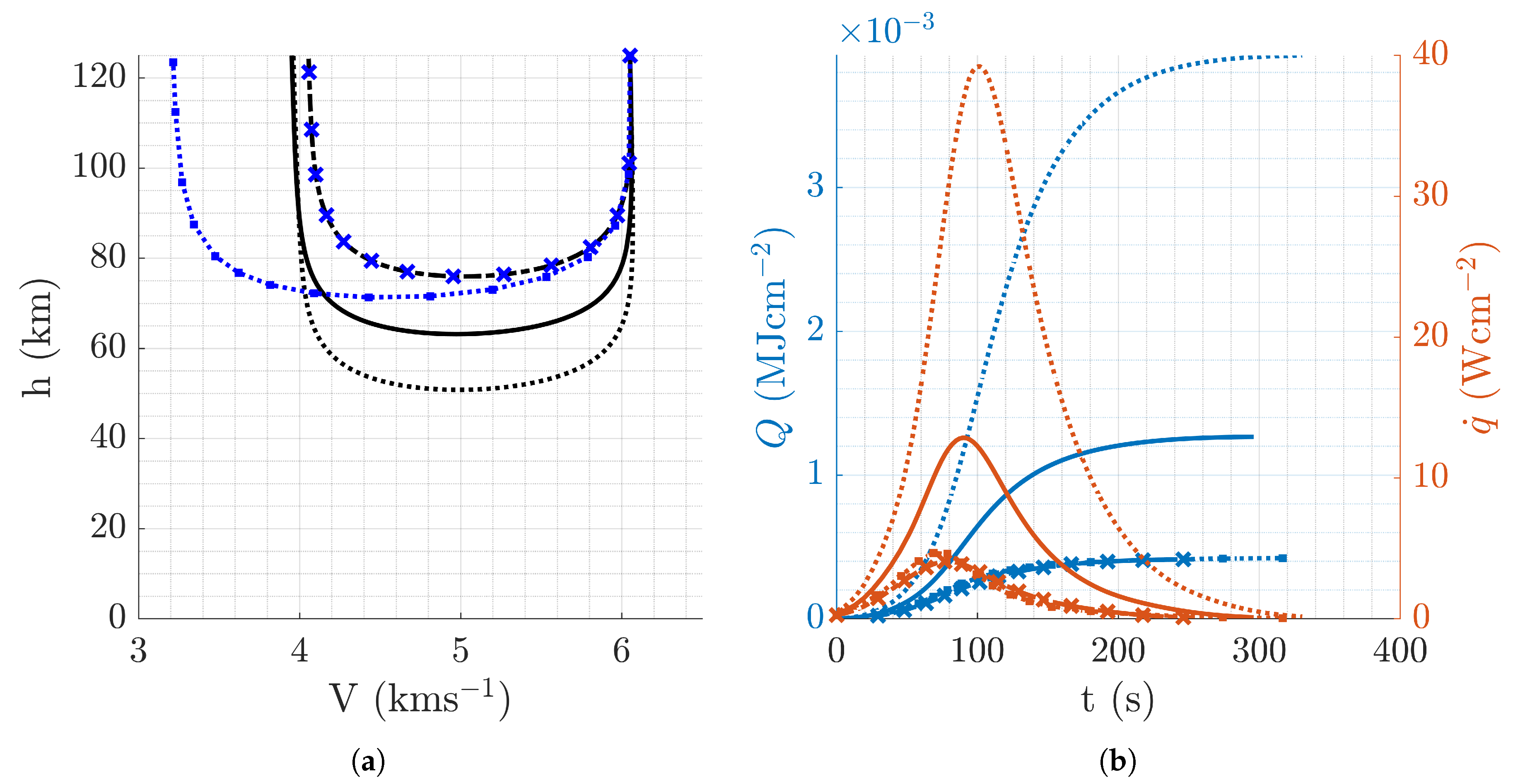

Figure 16.

Aerocapture trajectory profiles resulting from overall optimal mission design using MOO strategy, . (a) Altitude vs velocity. (b) Altitude and vs time.

Figure 16.

Aerocapture trajectory profiles resulting from overall optimal mission design using MOO strategy, . (a) Altitude vs velocity. (b) Altitude and vs time.

Figure 17.

Aerocapture trajectory profiles resulting from all optimal mission designs presented in this study. Initial conditions correspond to those that result in the lowest cost. (a) Altitude vs velocity. (b) Altitude and vs time.

Figure 17.

Aerocapture trajectory profiles resulting from all optimal mission designs presented in this study. Initial conditions correspond to those that result in the lowest cost. (a) Altitude vs velocity. (b) Altitude and vs time.

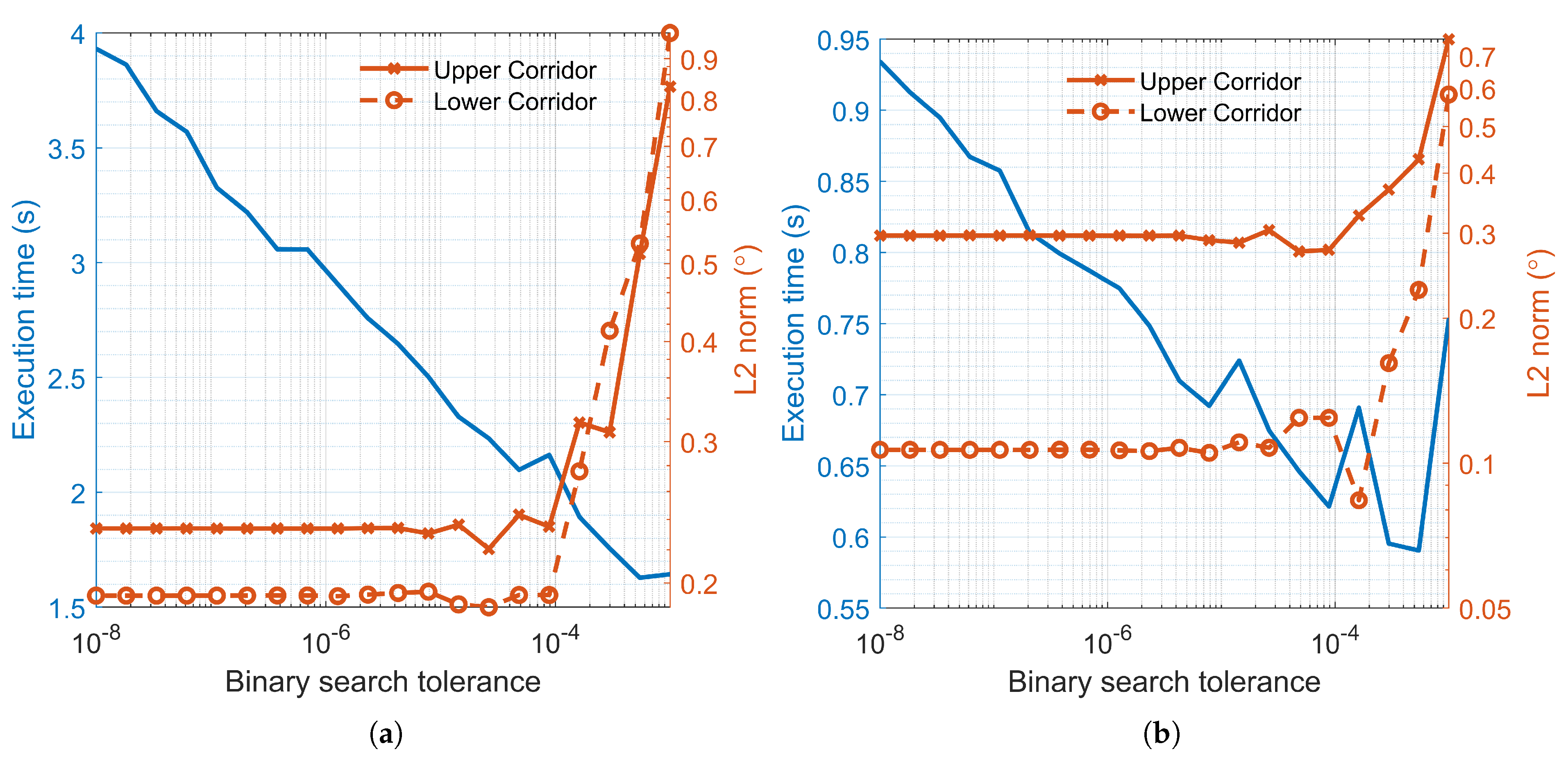

Figure 18.

Evolution of Euclidean L-2 norm of upper and lower boundary fits and execution time of robust coarse aerocapture corridor. (a) Martian Aerocapture, . (b) Terrestrial Aerocapture,

Figure 18.

Evolution of Euclidean L-2 norm of upper and lower boundary fits and execution time of robust coarse aerocapture corridor. (a) Martian Aerocapture, . (b) Terrestrial Aerocapture,

Table 1.

Minimum and maximum values of considered metrics for a Martian aerocapture corridor for

.

Table 1.

Minimum and maximum values of considered metrics for a Martian aerocapture corridor for

.

| Variable |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|

|

1.15 |

5.15 |

|

|

0.00 |

3.56 |

|

Q

|

3.42 |

41.53 |

|

|

3.45 |

46.32 |

Table 2.

Martian aerocapture simulation parameters

Table 2.

Martian aerocapture simulation parameters

| Parameter |

Value |

Parameter |

Value |

| Planetary parameters |

Insertion trajectory parameters |

| Radius of Mars,

|

3,390 |

km |

Hyperbolic excess velocity,

|

3.5 |

|

| Gravitational parameter,

|

|

|

Atmospheric interface altitude,

|

125 |

|

| Angular frequency of Mars,

|

|

|

Initial Radius,

|

|

|

| Vehicle parameters |

Initial velocity,

|

|

|

| Mass of vehicles, m

|

400 |

|

Initial longitude,

|

0.5798 |

|

| Drag coefficient,

|

1.6 |

|

Initial latitude,

|

34.49 |

|

| Lift-to-Drag ration,

|

0.2 |

|

Initial heading angle,

|

-18.24 |

|

| Nose radius to Body radius ratio,

|

0.5 |

|

Insertion flight path angle accuracy,

|

|

|

Table 3.

Target Operational orbit

Table 3.

Target Operational orbit

| Target parameter |

Semi-major axis, a

|

Inclination, i

|

Eccentricity, e

|

| Value |

4,621

|

70

|

0.05 |

Table 4.

Convergence properties of optimization algorithm with different initial conditions

Table 4.

Convergence properties of optimization algorithm with different initial conditions

| Case |

Initial Conditions |

Cost |

Optimized Parameters |

Performance Metrics |

| |

|

() |

|

|

() |

() |

() |

Q () |

() |

| 1 |

59.0 |

-60.000 |

0.5280 |

13.03 |

-9.756 |

2.472 |

0.777 |

12.608 |

12.805 |

| 2 |

40.6 |

-10.113 |

0.5280 |

13.69 |

-9.784 |

2.411 |

0.776 |

13.094 |

13.301 |

| 3 |

59.0 |

-0.057 |

0.5303 |

13.08 |

-9.758 |

2.467 |

0.778 |

12.649 |

12.846 |

| 4 |

3.0 |

-0.057 |

0.5283 |

13.10 |

-9.759 |

2.465 |

0.778 |

12.665 |

12.862 |

| 5 |

39.6 |

-10.852 |

0.5280 |

13.17 |

-9.762 |

2.458 |

0.778 |

12.714 |

12.913 |

| 6 |

37.8 |

-10.502 |

0.5283 |

13.16 |

-9.762 |

2.459 |

0.778 |

12.704 |

12.902 |

Table 5.

Optimal results for minimum fuel trajectory

Table 5.

Optimal results for minimum fuel trajectory

| Case |

|

() |

Cost

|

|

() |

() |

| 1 |

59.0 |

-60.000 |

0.1092 |

40.85 |

-10.393 |

0.7163 |

| 2 |

40.6 |

-10.113 |

0.1064 |

48.46 |

-10.487 |

0.7070 |

| 3 |

59.0 |

-0.057 |

0.1122 |

34.17 |

-10.294 |

0.7259 |

| 4 |

3.0 |

-0.057 |

0.1392 |

7.58 |

-9.445 |

0.8087 |

| 5 |

39.6 |

-10.852 |

0.1078 |

44.40 |

-10.439 |

0.7117 |

| 6 |

37.8 |

-10.502 |

0.1105 |

37.80 |

-10.350 |

0.7205 |

Table 6.

Optimal results for minimum heat load trajectory

Table 6.

Optimal results for minimum heat load trajectory

| Case |

|

() |

Cost

|

|

() |

Q () |

| 1 |

59.0 |

-60.000 |

|

3.00 |

-9.6289 |

4.221 |

| 2 |

40.6 |

-10.113 |

|

3.00 |

-8.7822 |

4.141 |

| 3 |

59.0 |

-0.057 |

|

3.00 |

-8.7803 |

4.140 |

| 4 |

3.0 |

-0.057 |

|

3.00 |

-8.7934 |

4.145 |

| 5 |

39.6 |

-10.852 |

|

3.00 |

-8.7862 |

4.142 |

| 6 |

37.8 |

-10.502 |

|

3.00 |

-8.7908 |

4.144 |

Table 7.

Optimal results for minimal trajectory.

Table 7.

Optimal results for minimal trajectory.

| Case |

|

() |

Cost

|

|

() |

() |

(deg) |

| 1 |

59.0 |

-60.000 |

7.92

|

3.0 |

-8.780 |

4.0754 |

0.2000 |

| 2 |

40.6 |

-10.113 |

7.92

|

3.0 |

-8.780 |

4.0754 |

0.2000 |

| 3 |

59.0 |

-0.057 |

7.92

|

3.0 |

-8.780 |

4.0754 |

0.2000 |

| 4 |

3.0 |

-0.057 |

7.92

|

3.0 |

-8.780 |

4.0754 |

0.2000 |

| 5 |

39.6 |

-10.852 |

7.92

|

3.0 |

-8.780 |

4.0754 |

0.2000 |

| 6 |

37.8 |

-10.502 |

7.92

|

3.0 |

-8.780 |

4.0754 |

0.2000 |

Table 8.

Convergence properties of MOO algorithm and D-ASTRO for overall optimal trajectory.

Table 8.

Convergence properties of MOO algorithm and D-ASTRO for overall optimal trajectory.

| Case |

|

() |

Strategy |

|

() |

() |

() |

Q () |

() |

| 1 |

59.0 |

-60.000 |

MOO |

3.000 |

-9.526 |

5.150 |

1.969 |

4.225 |

4.723 |

| |

|

|

D-ASTRO |

13.03 |

-9.756 |

2.472 |

0.779 |

12.608 |

12.805 |

| 2 |

40.6 |

-10.113 |

MOO |

3.007 |

-9.635 |

5.145 |

2.062 |

4.228 |

4.818 |

| |

|

|

D-ASTRO |

13.69 |

-9.784 |

2.411 |

0.776 |

13.094 |

13.301 |

| 3 |

59.0 |

-0.057 |

MOO |

3.000 |

-9.635 |

5.150 |

2.063 |

4.221 |

4.810 |

| |

|

|

D-ASTRO |

13.08 |

-9.758 |

2.467 |

0.778 |

12.649 |

12.846 |

| 4 |

3.0 |

-0.057 |

MOO |

3.000 |

-8.780 |

5.150 |

0.884 |

4.140 |

4.075 |

| |

|

|

D-ASTRO |

13.10 |

-9.759 |

2.465 |

0.778 |

12.665 |

12.862 |

| 5 |

39.6 |

-10.852 |

MOO |

3.000 |

-8.780 |

5.150 |

0.884 |

4.140 |

4.075 |

| |

|

|

D-ASTRO |

13.17 |

-9.762 |

2.458 |

0.778 |

12.714 |

12.913 |

| 6 |

37.8 |

-10.502 |

MOO |

3.000 |

-9.590 |

5.150 |

2.025 |

4.222 |

4.774 |

| |

|

|

D-ASTRO |

13.16 |

-9.762 |

2.459 |

0.778 |

12.704 |

12.902 |

Table 10.

Computational Performance and Suggested Optima of D-ASTRO and MOO strategies without employing polynomial fits to evaluate and . and used as initial guess for Martian test case.

Table 10.

Computational Performance and Suggested Optima of D-ASTRO and MOO strategies without employing polynomial fits to evaluate and . and used as initial guess for Martian test case.

| weights

|

Strategy |

Execution time (s) |

Function counts |

Time per function call (ms) |

|

|

|

D-ASTRO |

65.1 |

202 |

322 |

12.22 |

-9.719 |

| |

MOO |

90.2 |

304 |

297 |

3.00 |

-9.634 |

|

D-ASTRO |

48.9 |

162 |

302 |

40.60 |

-10.390 |

| |

MOO |

93.1 |

304 |

306 |

21.78 |

-8.501 |

|

D-ASTRO |

71.0 |

202 |

3528 |

16.00 |

-9.657 |

| |

MOO |

109 |

301 |

363 |

12.39 |

-9.853 |

Table 11.

Percentage difference in performance metrics when fits and binary search are used to assess the feasibility of candidate points.

Table 11.

Percentage difference in performance metrics when fits and binary search are used to assess the feasibility of candidate points.

| weights

|

Strategy |

Percentage Difference (%) |

| |

|

|

|

Q |

|

|

D-ASTRO |

4.036 |

0.566 |

-5.781 |

-5.798 |

| |

MOO |

0.454 |

0.097 |

-0.682 |

-0.673 |

|

D-ASTRO |

4.066 |

0.604 |

-5.842 |

-5.804 |

| |

MOO |

36.545 |

92.352 |

-58.701 |

-62.593 |

|

D-ASTRO |

-1.327 |

0.526 |

1.895 |

1.672 |

| |

MOO |

0.000 |

-0.046 |

-0.001 |

-0.005 |