1. Introduction

In comparison with classical mechanics which considers macroscopic objects both in deterministic and stochastic settings, quantum mechanics, concerned with physical phenomena at atomic and subatomic scales, inherently incorporates randomness. In particular, the squared absolute value of the wave function of a quantum mechanical particle is interpreted as a probability density function, mixed quantum states are built of pure ones using randomisation, and the latter is also present in the model of quantum measurement [

39,

51]. However, in contrast to scalar-valued classical probability measures [

41], quantum probability describes statistical properties of quantum variables by using quantum states in the form of density operators [

16,

30] on the same Hilbert space where those variables act as linear operators.

The noncommutativity and canonical commutation structures, coming from the operator-valued nature of quantum variables and quantum states, give rise to specific features of quantum probability such as the absence of a classical joint probability distribution and conditional expectations for a set of noncommuting quantum variables (whereas an individual self-adjoint operator has a well-defined marginal distribution). Furthermore, since the microscopic realm is less amenable to manipulation by conventional macroscopic tools (unlike, for example, the coin tossing as a manageable “random number generator” for thought and practical experiments in classical probability theory), its natural time evolution makes statistical properties of quantum systems particularly tied to their dynamics. While an isolated quantum system undergoes a reversible evolution (according to a one-parameter unitary group generated by the system Hamiltonian), a more realistic open dynamics scenario [

6] involves interaction of the system with its environment which can include other quantum or classical systems, measuring devices and external quantum fields (quantised electromagnetic radiation).

The interaction of an open quantum system with its surroundings is accompanied by energy exchange between the subsystems and gives rise to dissipative effects. This provides a way to influence statistical and dynamic properties of such systems by arranging them into quantum networks [

14] and varying the energy and coupling parameters of the resulting interconnections, which can consist of a quantum plant coupled in a measurement-based or coherent (that is, measurement-free) fashion to a controller or observer. This paradigm is used in quantum control [

3,

5,

8] which develops systematic methods for achieving stability, robustness with respect to unmodelled dynamics, and optimality in the sense of relevant performance criteria for quantum systems and their applications, for example, in quantum optics [

11,

50] and quantum information processing [

32].

An important part in these developments belongs to quantum filtering, which, similarly to its classical predecessor (see for example, [

23,

28]), is concerned with mean square optimal real time estimation of the internal variables of the quantum plant using a measurement-based quantum Kalman filter [

2,

4,

9] or a qualitatively different coherent quantum observer [

31,

45]. The latter does not process classical observations and, in contrast to the classical filters, does not compute the conditional expectations of the plant variables (this conditioning and related Bayesian approaches are not applicable in the noncommutative quantum case as mentioned above). Instead, the coherent quantum filter is driven by the output quantum fields of the plant so as to produce a quantum process, whose performance, as an estimator of the plant variables, can be optimised in the sense of minimising the mean square value of the “estimation error” by varying the parameters of the Hamiltonian and coupling operators of the filter.

The optimisation problems, arising in coherent quantum filtering and control (with the latter considering more complicated feedback interconnections of a quantum plant and a quantum controller) involve physical realisability (PR) constraints [

22,

40] which originate from the canonical commutation structures of quantum dynamic variables, the energetics of open quantum systems, and unitarity in the augmented system-environment evolution. These features of open quantum dynamics are incorporated in the Hudson-Parthasarathy quantum stochastic calculus [

19,

35] (see also [

15]) which is often employed as a unified modelling framework in quantum filtering and control. In this approach, the external fields at the input of a quantum system of interest are represented by a multichannel quantum Wiener process with noncommuting components, which act on a symmetric Fock space and drive the quantum stochastic differential equation (QSDE) governing the system dynamics. In contrast to the classical SDEs with a standard Wiener process [

24], the QSDE reflects the unitarity of the augmented system-field evolution, and its drift and dispersion terms (as well as the generator of Markovian quantum dynamics) are specified by the Hamiltonian and coupling operators. These operators (together with a scattering matrix representing the photon exchange between the fields [

35]) describe the energetics of the quantum system and its interaction with the environment and are usually functions (for example, polynomials or Weyl quantization integrals [

10]) of the system variables. A particular form of this dependence and the commutation structure of the system variables affect tractability of the quantum system.

In particular, a quadratic dependence of the system Hamiltonian and a linear dependence of the system-field coupling operators on the quantum mechanical position-momentum variables [

29] lead to linear QSDEs for open quantum harmonic oscillators (OQHOs) [

9,

11] which play the role of building blocks in linear quantum control theory [

8,

22,

34,

38,

54,

55]. The dynamics of such systems are relatively well understood and are similar to the classical linear SDEs in a number of respects, including the preservation of Gaussian nature of quantum states [

20,

36] in the case of vacuum input fields. However, the coherent quantum analogue [

33] of the classical linear-quadratic-Gaussian (LQG) control problem [

1,

25] for OQHOs is complicated by the above mentioned PR constraints on the state-space matrices of the quantum controller and by the impossibility to take advantage of the classical estimation-actuation separation principle and classical conditional expectations with their variational properties [

28].

One of the existing approaches to the coherent quantum LQG (CQLQG) control and coherent quantum filtering (CQF) problems employs the Frechet derivatives of the mean square cost (with respect to the state-space matrices subject to the PR constraints) for obtaining the optimality conditions [

44,

45] and for the numerical optimization [

42]. This approach takes into account the quantum nature of the underlying problem only through the PR constraints, being “classical” in all other respects, which has its own advantages from the viewpoint of well-developed conventional optimization methods. However, a disadvantage of this approach is that it is limited to certain parametric classes of linear controllers and observers. In particular, the resulting optimality conditions do not provide information on whether nonlinear quantum controllers or observers can outperform the linear ones for linear quantum plants. For this reason, the coherent quantum control and filtering problems require novel variational methods for their solution, which would be able to operate with sensitivity of the system dynamics and relevant cost functionals to perturbations over wider classes of the Hamiltonian and coupling operators in a “coordinate-free” fashion.

To this end, the present paper (some of its results were briefly announced in [

48]) outlines a fully quantum variational method which allows the sensitivity of the internal and output variables of a nonlinear quantum stochastic system to be investigated with respect to arbitrary (that is, not only linear-quadratic) perturbations of the Hamiltonian and coupling operators. This approach is based on using a

transverse Hamiltonian, defined as an auxiliary time-varying self-adjoint operator which encodes the propagation of such perturbations through the unitary system-field evolution. This leads to an infinitesimal perturbation formula for quantum averaged performance criteria (such as the mean square cost functional) which is applicable to the development of optimality conditions in coherent quantum control and filtering problems over larger classes of controllers and observers. In particular, this approach allows the sensitivity of OQHOs with quadratic performance criteria to be studied with respect to general perturbations of the Hamiltonian and coupling operators. In fact, the transverse Hamiltonian method has already been employed in [

47] in order to establish local sufficiency of linear observers in the mean square optimal CQF problem [

45] for linear quantum systems with respect to varying the Hamiltonian and coupling operators of the observer along linear combinations of the Weyl operators [

10]. Note that our approach is different from [

13] which develops a quantum Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman principle (for the density operator instead of the dynamic variables) in a measurement-based quantum feedback control problem. We also mention a parallel between the perturbation analysis, discussed in the present paper, and the fluctuation-dissipation theorem [

26].

The paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 specifies the class of quantum stochastic systems under consideration.

Section 3 discusses sensitivity of the internal and output variables of OQHOs to parametric perturbations within the families of quadratic system Hamiltonians and linear system-field coupling operators.

Section 4 returns to general QSDEs and introduces the transverse Hamiltonian associated with arbitrary perturbations of the Hamiltonian and coupling operators of the system. The transverse Hamiltonian is used in

Section 5 for infinitesimal perturbation analysis of system operators.

Section 6 extends the transverse Hamiltonian method to quantum averaged performance criteria.

Section 7 applies this approach to a mean square optimal CQF problem.

Section 8 makes concluding remarks.

We use the following principal notation in the paper. Denoted by is the commutator of linear operators A, B, with a linear superoperator associated with A. This extends to the commutator -matrix for vectors X, Y of operators , , respectively. Vectors are organised as columns unless indicated otherwise, and the transpose acts on matrices of operators as if their entries were scalars. In application to such matrices, is the transpose of the entry-wise operator adjoint . For complex matrices, is the usual complex conjugate transpose . The subspaces of real symmetric, real antisymmetric and complex Hermitian matrices of order n are denoted by , and , respectively, where is the imaginary unit. The real and imaginary parts of a complex matrix are denoted by and . These extend to matrices M with operator-valued entries as and which consist of self-adjoint operators. Positive (semi-) definiteness of matrices and the corresponding partial ordering are denoted by (≽) ≻. Also, and denote the sets of positive semi-definite real symmetric and complex Hermitian matrices of order n, respectively. The tensor product of spaces or operators (in particular, the Kronecker product of matrices) is denoted by ⊗. The tensor product of operators A, B acting on different spaces will sometimes be abbreviated as . The identity matrix of order n is denoted by , and the identity operator on a space H by . The Frobenius inner product of real or complex matrices is denoted by . Denoted by is a weighted Euclidean (semi-)norm of a real vector v specified by a real positive (semi-)definite symmetric matrix K. The quantum expectation of a quantum variable over a density operator extends in an entry-wise fashion to vectors and matrices of such variables.

2. Quantum stochastic systems being considered

We consider an open quantum system, which interacts with an external multichannel bosonic field and is equipped with dynamic variables

, evolving in time

and assembled into a vector

. These system variables are assumed to be self-adjoint operators on a composite system-field Hilbert space

. Here,

is the initial space of the system, which provides a domain for

, and

is a symmetric Fock space [

35] for the action of an even number

m of quantum Wiener processes

. The latter are time-varying self-adjoint operators, which model the external fields and are assembled into a vector

. Unlike the classical Brownian motion [

24] in

, the quantum Wiener process

W consists of noncommuting operator-valued components and has a complex Ito matrix

(identified with

) for its future-pointing Ito increments

:

Here, the matrix

specifies the canonical commutation relations (CCRs) for the constituent field processes

:

(with

spanning the subspace of antisymmetric

-matrices), which is an incremental form of the two-point CCRs

These CCRs are closely related to the continuous tensor-product structure of the Fock space [

37] and are complemented by the commutativity between the Ito increments of

W and adapted processes

taken at the same (or an earlier) moment of time:

The adaptedness of quantum processes on the system-field space

is understood with respect to a filtration

, where

and

is the Fock space filtration, so that for any

, the operators

act effectively on

, while

act on the subspace

.

The energetics of the quantum system and its interaction with the external fields is specified by a system Hamiltonian and system-field coupling operators which are time-varying self-adjoint operators, organised as deterministic functions (for example, polynomials with constant coefficients) of the system variables and assembled into a vector . Accordingly, the operators , act on the initial space . Depending on the context, a system operator (a function of the initial system variables ) on the initial space will be identified with its extension to the system-field space .

The system and the fields form a composite quantum system which evolves according to a quantum stochastic flow as described below. This evolution is specified at any time

by a unitary operator

on

governed by the following stochastic Schrödinger equation [

19,

35]:

with initial condition

, so that

captures the internal dynamics of the system and the system-field interaction over the time interval

. Here and in what follows, the subscript 0 marks the initial values of time-varying operators (or vectors or matrices of operators):

,

,

, while the time arguments will often be omitted for the sake of brevity. Also, the units are chosen so that the reduced Planck constant is

. The quantum stochastic differential equation (QSDE) (

6) corresponds to a particular yet important case of the identity scattering matrix, when there is no photon exchange between the fields, and the gauge processes [

35] can be eliminated from consideration. The term

in (

6) can be interpreted as an incremental Hamiltonian of the system-field interaction, while

involves the quantum Ito matrix

from (

1) and counterbalances the Ito correction term

in the differential relation

which describes the preservation of the co-isometry property

for all

. The system variables at time

, as operators on the system-field space

, are the images

of their initial values under the quantum stochastic flow

which maps a system operator

on the initial space

to the operator

on

in (

5). The resulting quantum adapted process

satisfies the following Hudson-Parthasarathy QSDE [

19,

35]:

where use is made of the Hamiltonian and the coupling operators evolved by the flow

from (

8) as

(the flow acts entry-wise on vectors and matrices of operators). Also,

in (

9) is the decoherence superoperator which acts on

as

The second equality in (

11) is applicable to the case when

is a vector of operators on which the superoperator

acts entry-wise. The superoperator

in (

9) is the Gorini-Kossakowski-Sudarshan-Lindblad (GKSL) generator [

12,

27], which is a quantum counterpart of the infinitesimal generators of classical Markov processes [

24]. The identity

, which holds for system operators

in view of (

8) and the unitarity of

, allows the QSDE (

6) to be represented in the Heisenberg picture by using (

10) along with the commutativity (

4) as

In application to the vector

of system variables, the quantum stochastic flow

also acts entry-wise as

in accordance with (

7), (

8), so that the corresponding QSDE (

9) can be represented in vector-matrix form:

where the

n-dimensional drift vector

and the dispersion

-matrix

consist of time-varying self-adjoint operators on

.

The interaction of the system with the input field

W produces the output fields

assembled into a vector

where the system-field unitary evolution is applied to the current input field variables (which reflects the innovation nature of the quantum Wiener process and the continuous tensor product structure of the Fock space mentioned above). The output field

Y satisfies the QSDE

where the matrix

J is given by (

2), and

L is the vector of system-field coupling operators from (

10). The system-field interaction makes the output field

Y different from the input field

W only through the drift vector

in (

16).

The common unitary evolution in (

13), (

15) preserves the commutativity between the system variables and the output field variables in time

:

where the entries of

,

commute as operators on different spaces

,

. By a similar reasoning, the output field

Y inherits the CCR matrix

J from the input quantum Wiener process

W:

where (

3) is used with

. By (

1), (

2), the relation (

18) can also be established as a corollary of the property that

Y in (

16) inherits the quantum Ito matrix

from

W as

.

In view of (

6) (see also (

12)), the quantum stochastic flow

in (

8) depends on the system Hamiltonian

and the system-field coupling operators in

. In turn,

and

are usually functions (such as polynomials or Weyl quantization integrals [

10] in [

49]) of the initial system variables

. The dependence of

,

on

is inherited by

H,

L as functions of

X and (along with a given commutation structure of the system variables) specifies a particular form of the resulting QSDEs (

14), (

16), thus influencing their tractability.

3. Open quantum harmonic oscillators with parametric dependence

An important class of quantum stochastic systems is provided by multimode open quantum harmonic oscillators (OQHOs) [

9] with an even number

n of system variables

(for example, consisting of

conjugate position-momentum pairs [

29]) satisfying the Heisenberg CCRs

(on a dense domain in

), where the CCR matrix

is identified with

and remains unchanged over the course of time

. The Hamiltonian

H of the OQHO is a quadratic function and the system-field coupling operators

in (

10) are linear functions of the system variables,

parameterised by an

energy matrix and a

coupling matrix. In this case, the QSDEs (

14), (

16) take the form

where the drifts

and

depend linearly on the system variables

, with

,

and the dispersion matrices

and

being constant real matrices. This linearity makes some of the dynamic properties of (

21) similar to those of a classical linear stochastic system with a state-space realization quadruple

and the corresponding

-valued transfer function

F on the complex plane:

thus allowing for application of transfer function techniques [

52]. However, in addition to the noncommutative nature of quantum variables, the matrices of coefficients of these QSDEs have a specific parameterization in terms of the energy, coupling and CCR matrices:

Since the energy matrix

R is symmetric, and the CCR matrices

,

J are antisymmetric, the matrices

A,

B,

C satisfy

These equalities pertain to the fulfillment of the CCRs (

19) and the commutativity (

17) at any moment of time and provide necessary and sufficient conditions for physical realizability (PR) [

22,

40] of the linear QSDEs (

21) as an OQHO with the CCR matrix

for the system variables. The first equality in (

24) has the structure of an algebraic Lyapunov equation (ALE) with respect to

, which has a unique solution if and only if the Kronecker sum

is a nonsingular matrix (that is, no two eigenvalues of

A are centrally symmetric about the origin in

). The latter condition holds, for example, when the matrix

A is Hurwitz. For more general open quantum systems (such as anharmonic oscillators whose dynamic variables satisfy the CCRs (

19), while the Hamiltonian and the coupling operators are not necessarily quadratic and linear functions of the system variables), the CCR preservation is secured by the unitary evolution of the system variables in (

13).

By analogy with the state-space realizations of transfer functions in classical linear systems theory [

1,

25], we will use the

input-output map for the OQHO (

21) with the matrix quadruple

:

Now, suppose the energy and coupling matrices

R,

N, which specify the Hamiltonian and the coupling operators in (

20), depend smoothly on an auxiliary parameter

(while the quantum Wiener process

W is independent of

). Then so also do the matrices

A,

B,

C in (

23) and the system and output variables which comprise the vectors

,

(the differentiability of

X,

Y is understood in the weak sense). The corresponding partial derivatives

at any

give rise to adapted quantum processes with self-adjoint operator-valued entries satisfying the QSDEs

(the second of which is, in fact, an ODE

involving the time derivative

of

), with zero initial conditions

,

since

,

do not depend on

. Here,

are the derivatives of the matrices

A,

B,

C from (

23) with respect to the parameter

satisfying the relations

which are obtained by differentiating the PR conditions (

24), with the CCR matrices

,

J being constant. Since the CCR matrices

,

J are antisymmetric (and hence,

), the first equality in (

29) implies that

By assembling the system variables and their parametric derivatives from (

26) to an augmented vector

a combination of the QSDEs (

21), (

27) allows the parametric derivative of the map (

25) to be represented as the input-output map

associated with

Here, the initial condition

, in view of

, is identified with

, and the matrices

,

,

are given by

This can also be obtained by using the transfer functions of the corresponding linear systems (including (

22)) as

for any

which is not an eigenvalue of

A. Here, use is made of a particular case of the block matrix inverse formula [

17]:

The block lower triangular structure of the dynamics matrix

in (

32), (

34) is closely related to the Gateaux derivative of the matrix exponential

in the direction

(see, for example, [

18]):

At any time

, both

and

depend linearly on the matrices

,

from (

28) in view of the following representation of the solutions of the QSDEs (

27), which regards

as a forcing term in the first of these QSDEs:

where

is the unperturbed solution of the first QSDE in (

21) which does not depend on

,

. In the case of linear QSDEs whose coefficients depend smoothly on parameters, the mean square differentiability of their solutions with respect to those parameters can be verified directly by using the closed form (

37) (under certain integrability conditions for the underlying quantum state in terms of relevant moments of the system variables such as

).

An additional insight into the structure of the process

is provided by its cross-commutation relations with

X,

W. In particular,

inherits the commutativity with the Ito increments of the input field

W from that of the underlying system variables in (

4), and so also does

in (

31):

Furthermore, the differentiation of (

19) in

, combined with the identity

for vectors

,

of operators, leads to

whereby the cross-commutation matrix

is symmetric (which holds regardless of a particular structure of the QSDEs (

21) and remains valid for quantum anharmonic oscillators with nonlinear dynamics). This matrix evolves in time (with zero initial condition because

) and has a steady-state value computed below.

Theorem 1.

Suppose the matrix A of the OQHO (21) in (23) is Hurwitz. Then there exist the following limits

where the matrices , are found as unique solutions of the ALEs

Proof. In view of the CCRs (

19), the commutator matrix for the vector

in (

31) is organised as

where the blocks

,

and

consist of time-varying skew self-adjoint operators on the system-field space

. By using the quantum Ito lemma [

19,

35] and the bilinearity of the commutator along with the QSDE (

33) and the commutativity (

38), it follows that (

43) satisfies the QSDE

which (similarly to [

22], Eq. (

56)]) reduces to the ODE

with the initial condition

in view of

. Hence, at any time

, the matrix

is an imaginary antisymmetric matrix which can be represented as

with time-varying matrices

and

. Substitution of (

46) into (

44) and using (

34) leads to the ODEs

with zero initial conditions

,

in accordance with the corresponding blocks in (

45). Now, the matrix

is symmetric at any time

due to (

39). This also follows from (

47) in view of the symmetry (

30). Hence,

, and the ODE (

48) takes the form

If the matrix

A is Hurwitz, then the solutions of the ODEs (

47), (

49) converge to their unique steady-state values which (slightly abusing notation) satisfy the ALEs (

41), (

42) and specify the limits (

40). □

The relations (

28)–(

36) and Theorem 1 provide infinitesimal perturbation analysis for sensitivity of the internal and output variables of the OQHO to the matrices

R,

N. Under the perturbations of

R,

N, the Hamiltonian

H and the coupling operators in

L, given by (

20), remain in the corresponding classes of quadratic and linear functions of the system variables. Accordingly, the above analysis is not applicable to more general perturbations (for example, higher order polynomials of the system variables) and is restricted to linear QSDEs, so that an alternative approach is needed in the general case.

4. Transverse Hamiltonian

For the general quantum stochastic system, described in

Section 2 and governed by (

14), (

16), we will now consider its response to arbitrary perturbations in the system Hamiltonian

and the system-field coupling operators in

. More precisely, suppose they are perturbed in directions

,

as

Here,

and the entries of the

m-dimensional vector

are self-adjoint operators on the initial system space

, and

is a small real-valued parameter as before, so that

and

. In what follows, the derivative

is taken at

. The perturbations

,

in (

50) are also assumed to be functions of the initial system variables

, and these dependencies describe

as functions of

under the

unperturbed flow (

8). For example, in the case of OQHOs considered in

Section 3, the perturbations

K,

M, which are caused by the perturbations in the energy and coupling matrices

R,

N, inherit the structure of the Hamiltonian as a quadratic function and the coupling operators as linear functions of the system variables in (

20), respectively:

Returning to the general case, we will avoid at this stage technical assumptions on

,

in (

50), so that the calculations, carried out below for arbitrary perturbations, should be regarded as formal. Since the operators

,

completely specify the dynamics of the unitary operator

in (

6) which determines the evolution of the system and output field variables, the response of the latter to the perturbations (

50) of

,

reduces to that of

. Therefore, the propagation of the initial perturbations

,

of the operators

,

through the subsequent unitary system-field evolution can be described in terms of the operator

which satisfies

since

does not depend on

. The smoothness of dependence of

on the parameter

is analogous to the corresponding property of solutions of classical SDEs (whose drift and dispersion satisfy suitable regularity conditions [

24,

43]) and holds at least in the case of linear QSDEs discussed in

Section 3. The following theorem is closely related to Stone’s theorem on generators of one-parameter unitary groups [

53].

Theorem 2.

For any time , the operator in (53), associated with the unitary evolution from (6), can be represented as

Here, is a self-adjoint operator on the system-field space , which satisfies zero initial condition and is governed by the QSDE

Furthermore, depends linearly on the initial perturbations , of the Hamiltonian and coupling operators in (50) through their unperturbed evolutions in (51).

Proof. The differentiation of both sides of the unitarity relation

with respect to the parameter

at

leads to

, which implies self-adjointness of the operator

thus establishing (

54). Now, consider the time evolution of

. To this end, the differentiation of (

6) with respect to

yields

By left multiplying both sides of (

57) by

and recalling (

56), it follows that

where use is made of the evolved perturbations (

51). By a similar reasoning, a combination of (

12) with (

56) leads to

where use is also made of (

58) along with the quantum Ito product rules [

35] and (

1), (

4). It now follows from (

56), (

58)–(

60) that

which establishes (

55). The linear dependence of

on

,

follows from the integral representation

of the QSDE (

55) and the property that the evolved perturbations

K,

M in (

51) depend linearly on

,

, respectively. □

In view of Theorem 2, for any fixed but otherwise arbitrary time

, the relation (

54), represented as

has the structure of isolated quantum dynamics in fictitious time

, where

plays the role of a Hamiltonian pertaining to the perturbation of the unitary operator

. In order to reflect this property, we will refer to the time-varying operator

Q as the

transverse Hamiltonian associated with the perturbations

K,

M of the system Hamiltonian

H and the system-field coupling operators in

L. The computation of

Q is illustrated by the following two examples.

Example 1

In the absence of perturbation to the system-field coupling, when the vector

in (

50) consists of zero operators, and hence, so also does

M in (

51), the transverse Hamiltonian in (

61) reduces to

Moreover, if the system is isolated, that is,

, then (

6) reduces to the ODE

which leads to

with the Hamiltonian being preserved in time:

for all

. In this case of isolated system dynamics, (

62) takes the form

Here, use is made of Hadamard’s lemma [

29] along with an entire function

of a complex variable (with

by continuity) which plays a role in the solution of nonhomogeneous linear ODEs with constant coefficients and constant forcing terms [

18]. The Gateaux derivative (

53) of (

63) can be represented by using an operator version of (

35) as

which provides an alternative verification of (

54) for this particular case, with

Q given by (

64). ▲

Example 2

For the OQHO of

Section 3, substitution of the perturbations (

52) into (

61) leads to the transverse Hamiltonian

which depends linearly on the matrices

,

and in a quadratic fashion on the past history of the system variables. The latter are given by the unperturbed equation (

37). The last term

in (

66) comes from the relation

(following from (

1)) and the identity

which holds for any matrix

in view of the CCRs (

19). ▲

5. Infinitesimal perturbation analysis of system operators

Since the transverse Hamiltonian

in (

56), (

61) encodes the propagation of the initial perturbations of the Hamiltonian and coupling operators in (

50) through the unitary system-field evolution over the time interval

, it provides a tool for infinitesimal perturbation analysis of general system operators. The following theorem is concerned with an extended setting which, in addition to (

50), allows for a smooth dependence of a system operator

on the parameter

, so that an appropriate infinitesimal perturbation in it is specified by an operator

on the initial space

, with

also being a function of the initial system variables

.

Theorem 3.

For any self-adjoint system operator on the initial space , which smoothly depends on the same scalar parameter ϵ as in (50) and is evolved by the flow (8), the derivative of its evolved version with respect to ϵ can be represented as

at any time , where is the transverse Hamiltonian from Theorem 2. Here, the operator satisfies the QSDE

with zero initial condition , where is the unperturbed GKSL generator from (9), and χ is a linear superoperator given by

Proof. By using the Leibniz product rule together with (

8), (

53), (

54) and the self-adjointness of

, it follows that

which establishes (

67), with the initial condition

being inherited by

from

. We will now obtain a QSDE for the process

. To this end, by combining the quantum Ito lemma with the bilinearity of the commutator, and using the QSDEs (

9), (

55), it follows that

Here, the quantum Ito product rules are applied together with the commutativity (

4) between adapted processes and the Ito increments of the quantum Wiener process

W. In the second and third of the equalities (

71), use is also made of the relations

and

for appropriately dimensioned adapted processes

,

with self-adjoint operator-valued entries. These relations are combined with the identity

in the fourth equality of (

71). The QSDE (

68) is now obtained my multiplying both sides of (

71) by

i and using the superoperator

from (

69). □

As can be seen from (

70), the process

in (

67) is the response of

to the initial perturbation

of the system operator under the unperturbed flow (

8) and satisfies the QSDE (

9):

In contrast to

, the operator

in (

67) describes the response of the flow

itself to the perturbations (

50) of the Hamiltonian and coupling operators and will be referred to as the

derivative process for the system operator

. Accordingly, the term

in the drift of the QSDE (

68) is the derivative process for

. At any given time

, the last equality in (

67) is organised as the right-hand side of the Heisenberg ODE (in fictitious time

) of an isolated quantum system with the state space

and the Hamiltonian

. While

(evolved by the unperturbed flow) depends linearly on

, the derivative process

depends linearly on the perturbations

,

of the Hamiltonian

and the coupling operators in

through the transverse Hamiltonian

Q and the superoperator

in (

69).

In application to the vectors

X,

L of the system variables and the system-field coupling operators, the QSDEs (

68), (

72) and the definition (

69) lead to

where

F,

G are the unperturbed drift vector and the dispersion matrix from (

14). In (

73), use is also made of the absence

of initial perturbations in the system variables, whereby

for any

. Furthermore, in (

74), we have used the relations

in view of (

50), (

51). Since the matrix

J and the quantum Wiener process

W do not depend on the parameter

, the derivative of the output field

Y of the system in (

16) evolves according to the ODE

where

is governed by the QSDE (

74).

In particular, for the OQHO of

Section 3 with the perturbations (

52), the QSDEs (

73)–(

75) lead to the relations (

27), (

28) which were obtained in

Section 3 using more elementary techniques. However, the latter are limited to quadratic perturbations of the Hamiltonian and linear perturbations of the coupling operators in (

52), whereas the transverse Hamiltonian approach allows the system response to be investigated for general perturbations of these operators. Therefore, this approach can be used for the development of optimality conditions in quantum control and filtering problems for larger classes of controllers and observers.

6. Sensitivity of infinite-horizon quantum averaged functionals

Similarly to optimal control of classical time invariant stochastic systems [

1,

25], suppose the infinite-horizon performance of the quantum system being considered is described by a cost functional

which (whenever it exists) leads to the same Cesaro limit

and is to be minimised in optimal quantum control settings. Here, the quantum expectation

is taken over the tensor product

of the initial quantum state

of the system and the vacuum state [

35]

in the Fock space

for the external bosonic fields. This expectation is applied in (

76) to a quantum

criterion processZ, specified as

by a function

. The latter is extended to the noncommutative system variables and the coupling operators (with

L being in a bijective correspondence with the drift vector

of the output field in (

16) since

in view of (

2)) so as to make

a self-adjoint operator for any

. Such an operator-valued extension of

f is straightforward in the case of polynomials and can be carried out through the Weyl quantization [

10] for more general functions. In the coherent quantum linear-quadratic-Gaussian (CQLQG) control and filtering problems [

33,

44,

45], the function

f in (

78) is a positive semi-definite quadratic form, in which case, the minimization of (

76) provides an infinite-horizon mean square optimality criterion.

Now, if the Hamiltonian and coupling operators of the quantum system are perturbed according to (

50), then application of the transverse Hamiltonian

Q from Theorems 2, 3 leads to

where

is the derivative process for

Z. Note that, despite

, the operator

can be nonzero due to the dependence of

Z in (

78) on

L. Assuming the existence and interchangeability of appropriate limits, (

79) leads to the following perturbation formula for the cost functional

in (

76):

The right-hand side of (

80) is a linear functional of the perturbations

,

, which describes the corresponding (formal) Gateaux derivative of

in the direction

. Therefore, the quantum system is a stationary point of the performance criterion (

76) with respect to a subspace

of perturbations

in (

50), if

is contained by the null space of the linear functional

in (

80):

This inclusion provides a first-order necessary condition of optimality in the quantum control problem of minimising (

76) over a manifold of the Hamiltonian and coupling operators with the local tangent space

.

While

in (

80) reduces to averaging over the invariant quantum state of the unperturbed system (provided certain integrability conditions are satisfied together with the existence of and weak convergence to the invariant state), the computation of

is less straightforward. Due to the product structure (

77) of the system-field state

(with the external fields being in the vacuum state

), the martingale part of the QSDE (

68) does not contribute to the time derivative

where

is the derivative process for

, and the superoperator

from (

69) is applied to the criterion process

Z in (

78).

The relation (

82) is a complicated integro-differential equation (IDE). However, this IDE admits an efficient solution, for example, in the case when the system is an OQHO, and the function

f in (

78) is a polynomial. In this case, due to the structure of the GKSL generator of the OQHO,

is also a polynomial in the system variables of the same degree, thus leading to a linear relation (with constant coefficients) between the derivative processes

,

and to algebraic closedness in the IDE (

82). Therefore, for stable OQHOs (with a Hurwitz matrix

A) and a polynomial criterion process

Z, the computation of

(and verification of the stationarity condition (

81)) reduces to averaging over the unperturbed invariant state (which is unique and Gaussian [

36]). These calculations are exemplified below.

Example 3

Consider the OQHO of

Section 3, described by (

19)–(

23) with a Hurwitz matrix

A. Suppose the criterion process

Z in (

78) is a quadratic polynomial of the system variables

and the system-field coupling operators

:

where

is a given weighting matrix, partitioned into blocks

,

,

, and

is an auxiliary matrix which involves the coupling matrix

N from (

20). Then, in view of

, it follows from (

83), (

52) that

The second equality in (

83) allows the quantum average of the corresponding derivative process

in (

79) to be represented as

Here,

is the expectation of the derivative process

for

and hence, satisfies the following IDE, similar to (

82):

where the superoperator

from (

69) is applied to

entry-wise as

with

the

ℓth row of the CCR matrix

. By substituting the Hamiltonian and coupling operators of the OQHO from (

20) into the GKSL generator

in (

9), (

11) and using the CCRs (

19) together with the state-space matrices (

23), it follows that

Substitution of (

89) into (

87) reduces the IDE to a Lyapunov ODE:

Since the matrix

A is Hurwitz, the unperturbed OQHO has an invariant state which is Gaussian [

36] with zero mean

and covariance matrix

, where

is a unique solution of the ALE

Therefore, under appropriate integrability conditions for

, the solution of the Lyapunov ODE (

90) has a limit

which is a unique solution of the ALE

where

can be computed by averaging

over the invariant Gaussian state of the OQHO. Therefore, by assembling (

85), (

86) into (

80), it follows that

where the limit also reduces to averaging over the invariant Gaussian state and is expressed in terms of

as

The relations (

84), (

88), (

92)–(

94) allow the Gateaux derivative

of the quadratic cost functional (

76), specified by (

83), to be computed through mixed moments of the system variables

X and the perturbations

K,

M over the invariant zero-mean Gaussian quantum state whose covariance matrix is found from (

91). In particular, if

K,

M are polynomials of the system variables

, then these moments can be calculated in terms of the covariances by using the Isserlis-Wick theorem [

21]. Alternatively, the perturbations

K,

M can be trigonometric polynomials, that is, linear combinations of unitary Weyl operators [

10]

associated with the system variables, or more generally, represented as the Weyl quantization integrals

similar to those in [

49], (Eq.

32). Here,

,

are countably additive measures of finite variation on the

-algebra

of Borel subsets of

, which take values in

and

, respectively, and satisfy the Hermitian property

and

for any

, thus ensuring that

K and the entries of

M in (

96) are self-adjoint operators in view of the second equality in (

95). Now, the Weyl CCRs

for all

(with their infinitesimal Heisenberg form given by (

19)) imply that

, whereby

Since the quantum expectation commutes with the differential operator on the right-hand side of (

97), and the quasi-characteristic function [

7] of the invariant zero-mean Gaussian state is given by

, then

which can also be obtained by using quantum Price’s theorem [

46]. A combination of the second equality from (

96) with (

98) leads to

The computation of the limit in (

93) in the Weyl quantization framework is now completed by substituting (

99) into (

94). In this framework, the matrix

, which is needed for finding

from the ALE (

92) for the last term in (

93), is computed by averaging (

88) in a similar fashion. ▲

7. Mean square optimal coherent quantum filtering problem

We will now outline an application of the transverse Hamiltonian approach of

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6 to a quantum filtering problem for the open quantum system, described in

Section 2 and referred to as a

quantum plant. The plant has the Hamiltonian

H, the vector

L of system-field coupling operators, the input field

W, the vector

X of internal variables and the output field

Y governed by the QSDEs (

14), (

16). Although the plant is not necessarily an OQHO, we assume that the plant variables

are organised as position-momentum pairs and satisfy the CCRs (

19).

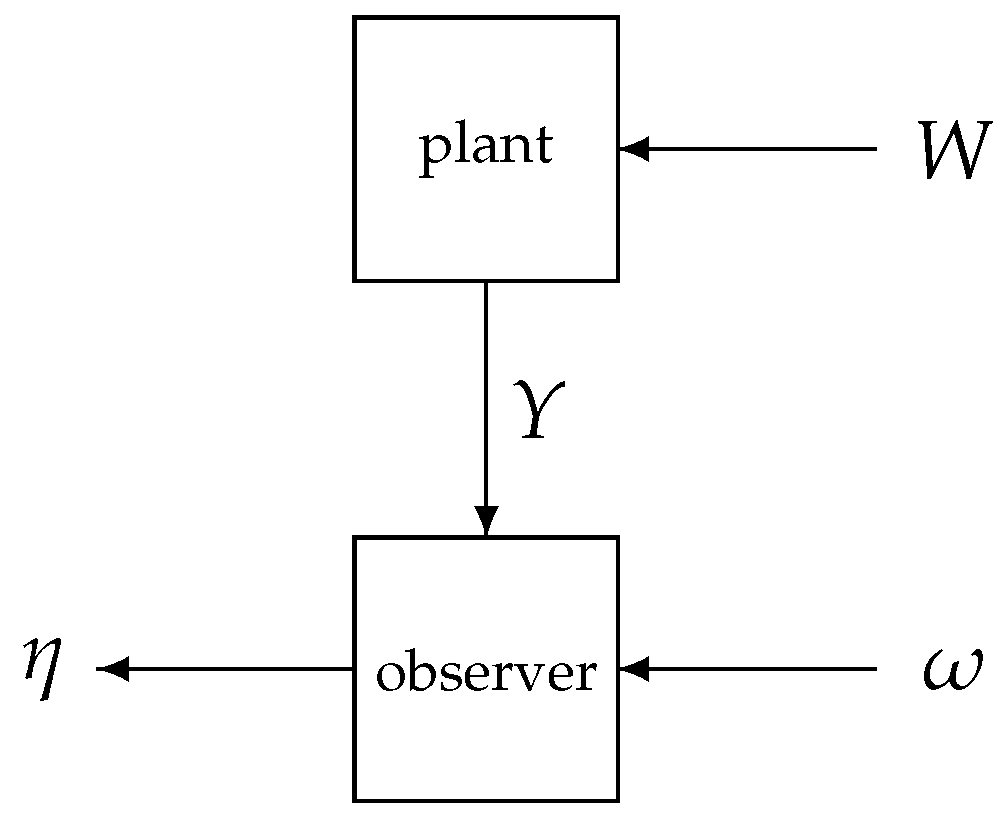

Suppose the quantum plant is cascaded in a measurement-free field-mediated fashion with another open quantum system, playing the role a

coherent quantum observer, which is driven by the plant output

Y and another quantum Wiener process

of an even dimension

on a different bosonic Fock space

; see Fig.

Figure 1.

The observer is endowed with its own initial Hilbert space

, dynamic variables

with a CCR matrix

(so that

for any

, similarly to (

19)), and an

-dimensional output field

:

Since the observer is driven by the plant output

Y (together with the quantum noise

), the observer output

acquires, over the course of time, quantum statistical correlations with the plant variables and can be used for estimating the latter in a mean square optimal fashion as specified below. To this end, we denote the observer Hamiltonian by

and the vectors of operators of coupling of the observer with the plant output

Y and with the quantum Wiener process

by

respectively. The Hamiltonian

and the coupling operators

,

are functions of the dynamic variables

of the observer and hence, commute with the plant variables and functions thereof, including

H,

L. The plant and observer form a composite quantum stochastic system, whose vector

of dynamic variables satisfies the CCRs

and is driven by an augmented quantum Wiener process

with the following Ito table:

Here, ℧ is the Ito matrix of the quantum Wiener process

of the observer, which is defined similarly to

from (

1), (

2) as

The quantum feedback network formalism [

14] allows the Hamiltonian

of the plant-observer system and its vector

of operators of coupling with

to be computed as

Hence, the internal and output variables

and

of the observer in (

100) are governed by the QSDEs

Here,

is the GKSL generator of the plant-observer system, and

is the corresponding decoherence superoperator, in accordance with (

11), (

103), (

105). In (

106), use is also made of the partial decoherence superoperator

which acts on the observer variables as

in view of (

102)–(

105). Now, consider a coherent quantum filtering (CQF) problem formulated as the minimisation of the mean square discrepancy

between

r linear combinations of the plant variables of interest and the entries of the drift part

of the observer output

in (

107) as specified by given weighting matrices

and

, with

,

. The criterion process

Z in (

108) is similar to that in (

83):

with

X being the only subvector of

from (

102) which is present in (

109). The minimization in (

108) is over the observer Hamiltonian

and the vector

of the observer-plant coupling operators in (

101) as functions of the observer variables

. This mean square optimal CQF problem extends [

45] in that we do not restrict attention to linear observers even if the plant is an OQHO and

depends linearly on the observer variables

. Note that the Hamiltonian

H of the plant and its coupling

L to the input quantum noise

W are fixed, and so also is the coupling

of the observer to the input quantum noise

; see

Figure 1. If

,

are perturbed in the directions

consisting of self-adjoint operators representable as functions of the initial observer variables

, then the corresponding perturbations of the plant-observer Hamiltonian and coupling operators in (

105) are

By applying Theorem 2 and using (

103), (

110), (

111), it follows that the corresponding transverse Hamiltonian

Q for the plant-observer system satisfies the QSDE

where use is also made of

(following from (

1) and the commutativity

). Then the Gateaux derivative

of the cost functional in (

108) is given by (

80), where

in view of (

109), (

111) and similarly to (

85). In accordance with (

82), the expectation of the derivative process

satisfies the IDE

where, in view of (

112), the superoperator

in (

69) is given by

In particular, if both the plant and the unperturbed observer are OQHOs with Hurwitz dynamics matrices (while the perturbations in (

110) are not necessarily linear-quadratic), then

can be found (in a form similar to (

93)) along the lines of Example 3 of

Section 6 due to the criterion process

Z in (

108), (

109) being a quadratic function of the plant and observer variables in

from (

102).

The transverse Hamiltonian method, outlined above, was used in [

47] for showing that, in the mean square optimal CQF problem for linear quantum plants, those observers, which are locally optimal in the class of linear quantum observers, cannot be improved locally (in the sense of the first-order optimality conditions (

81)) by varying the Hamiltonian and coupling operators of the observer along linear combinations of the Weyl operators associated with the observer variables.