Submitted:

22 May 2023

Posted:

24 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

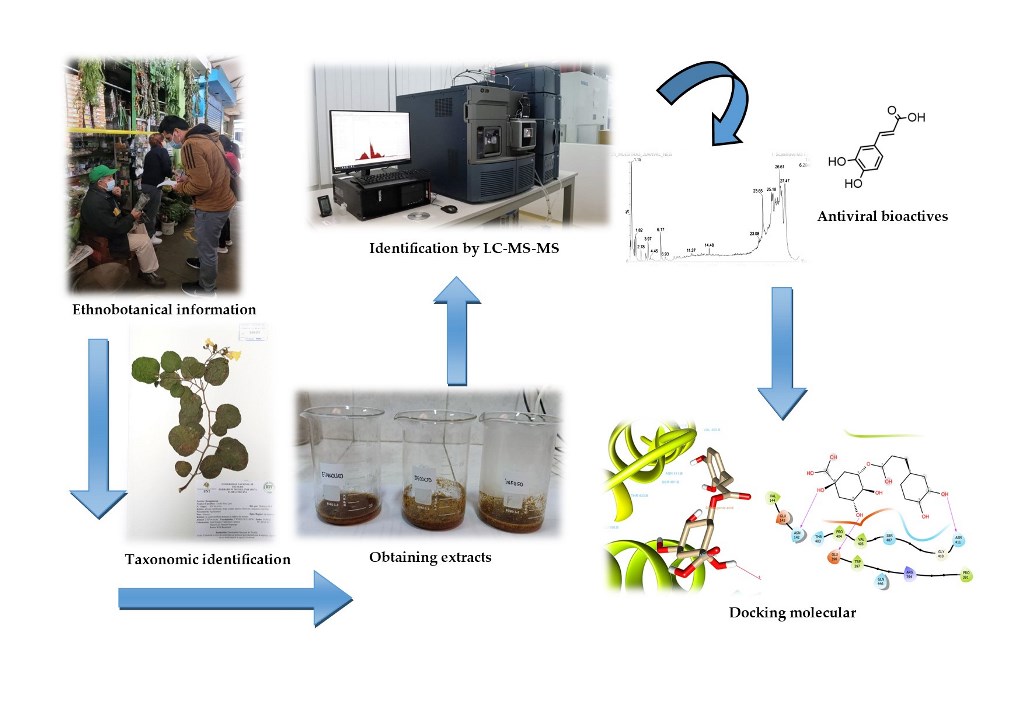

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Taxonomic and Ethnobotany of Medicinal Plants

2.2. Antiviral Activity of Phytometabolites Polyphenolics of Medicinal Plants

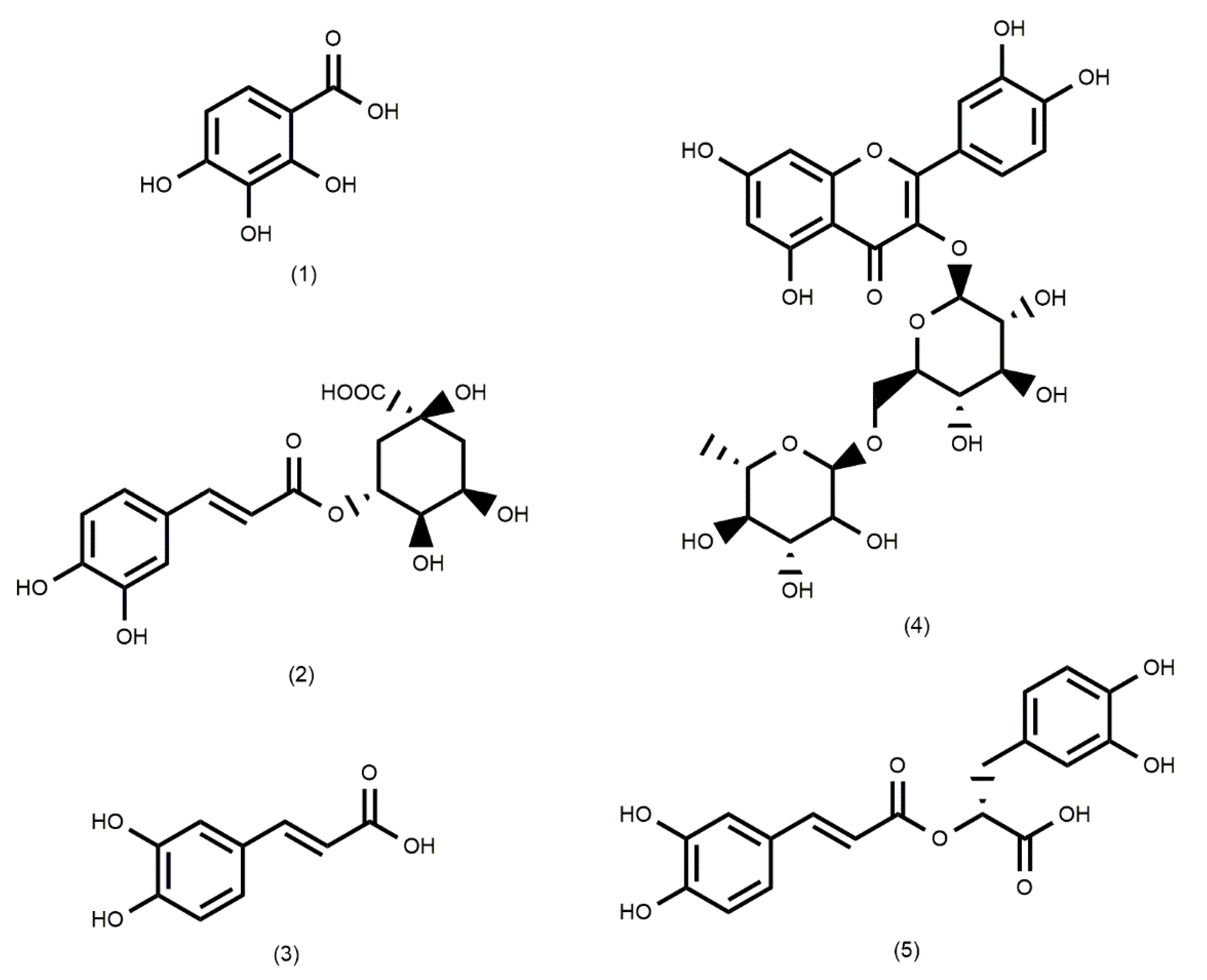

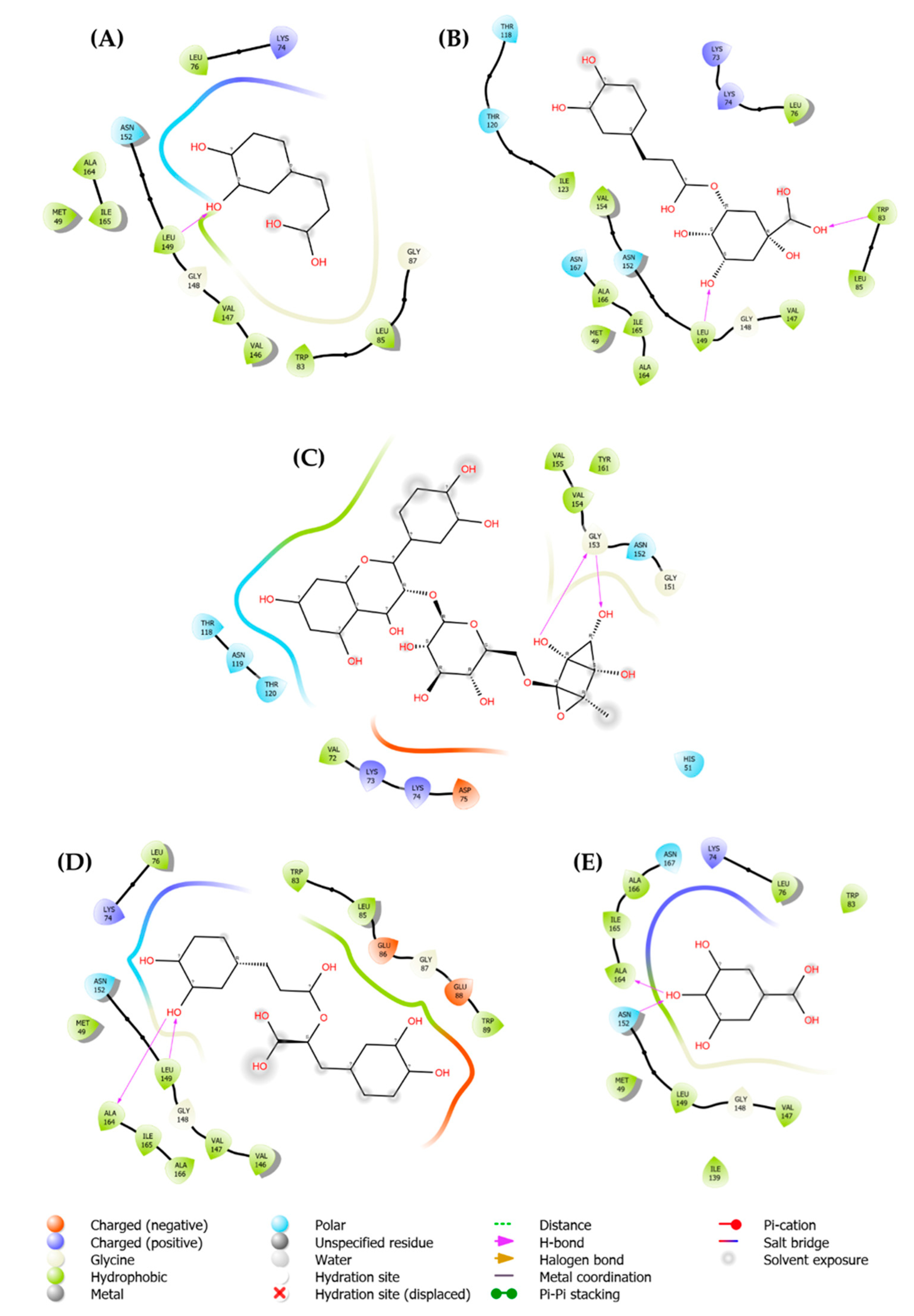

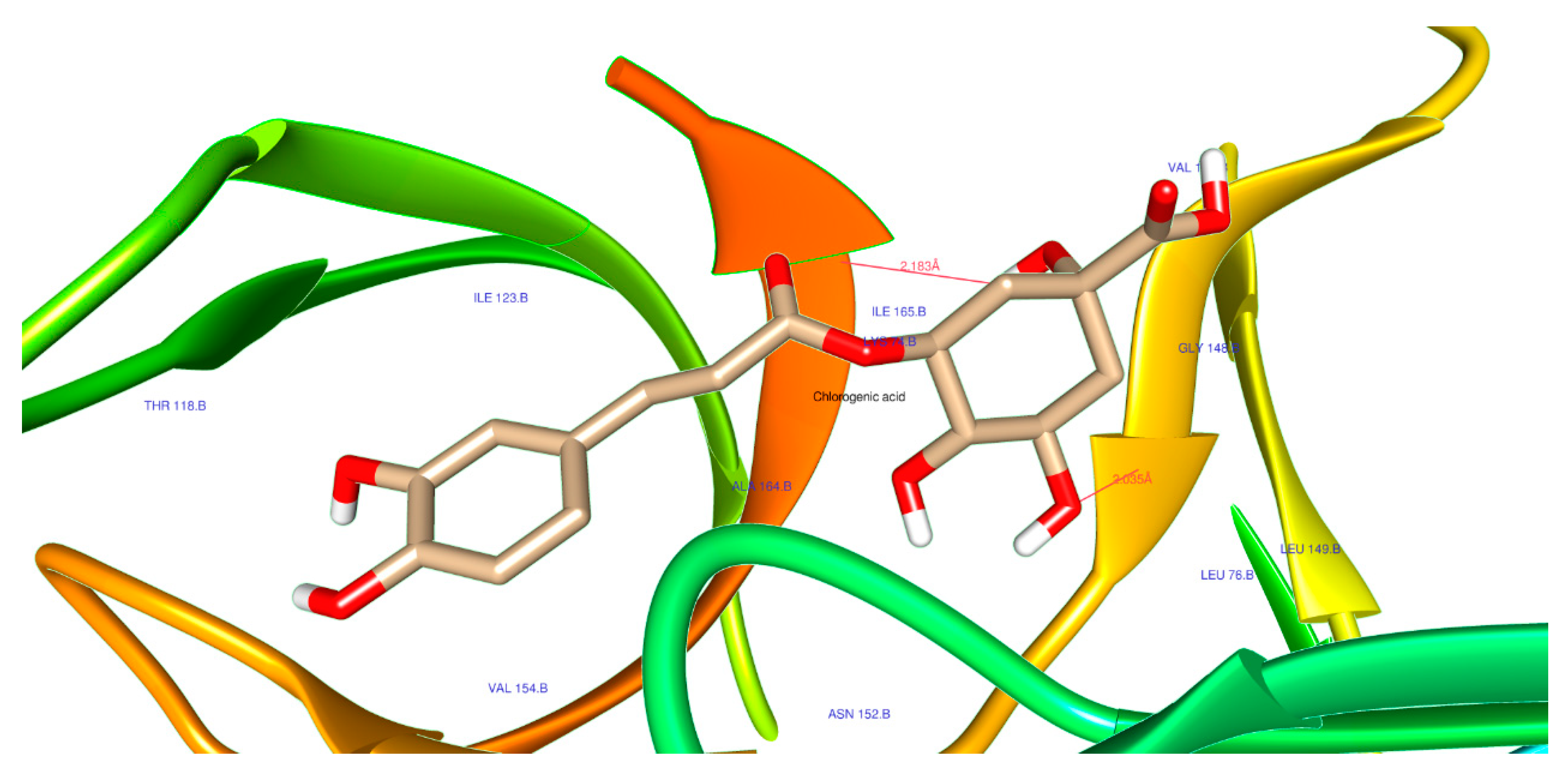

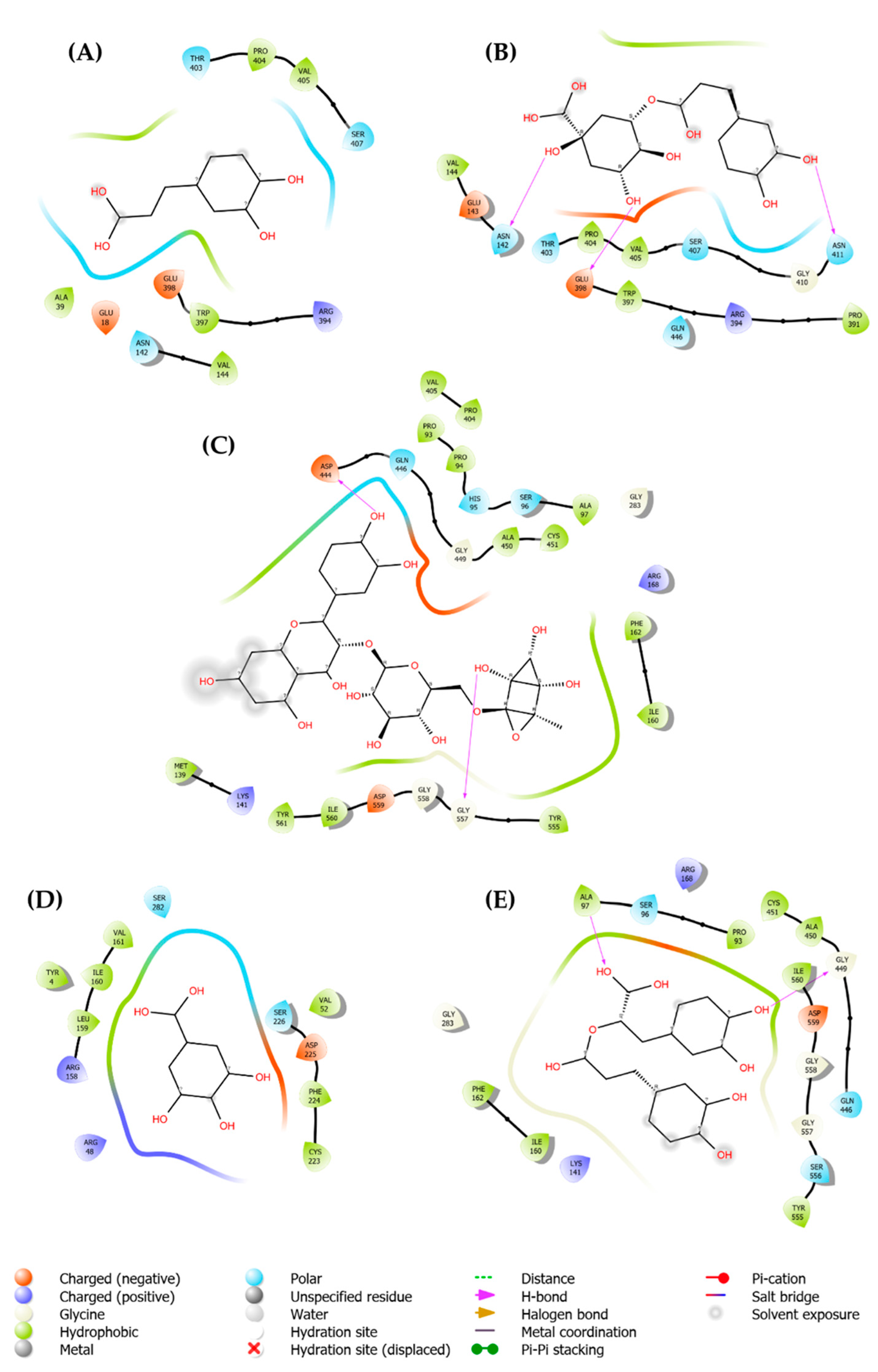

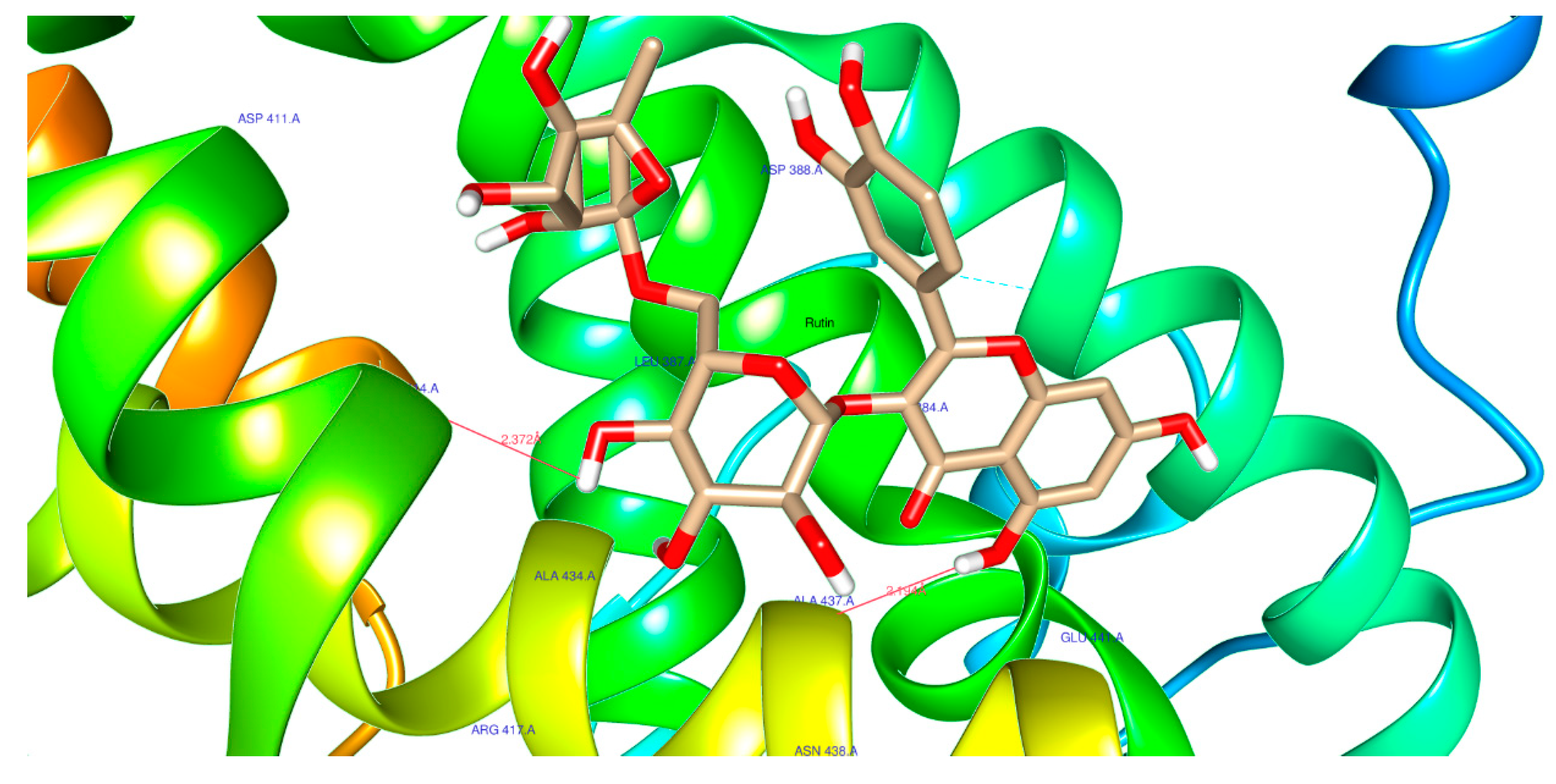

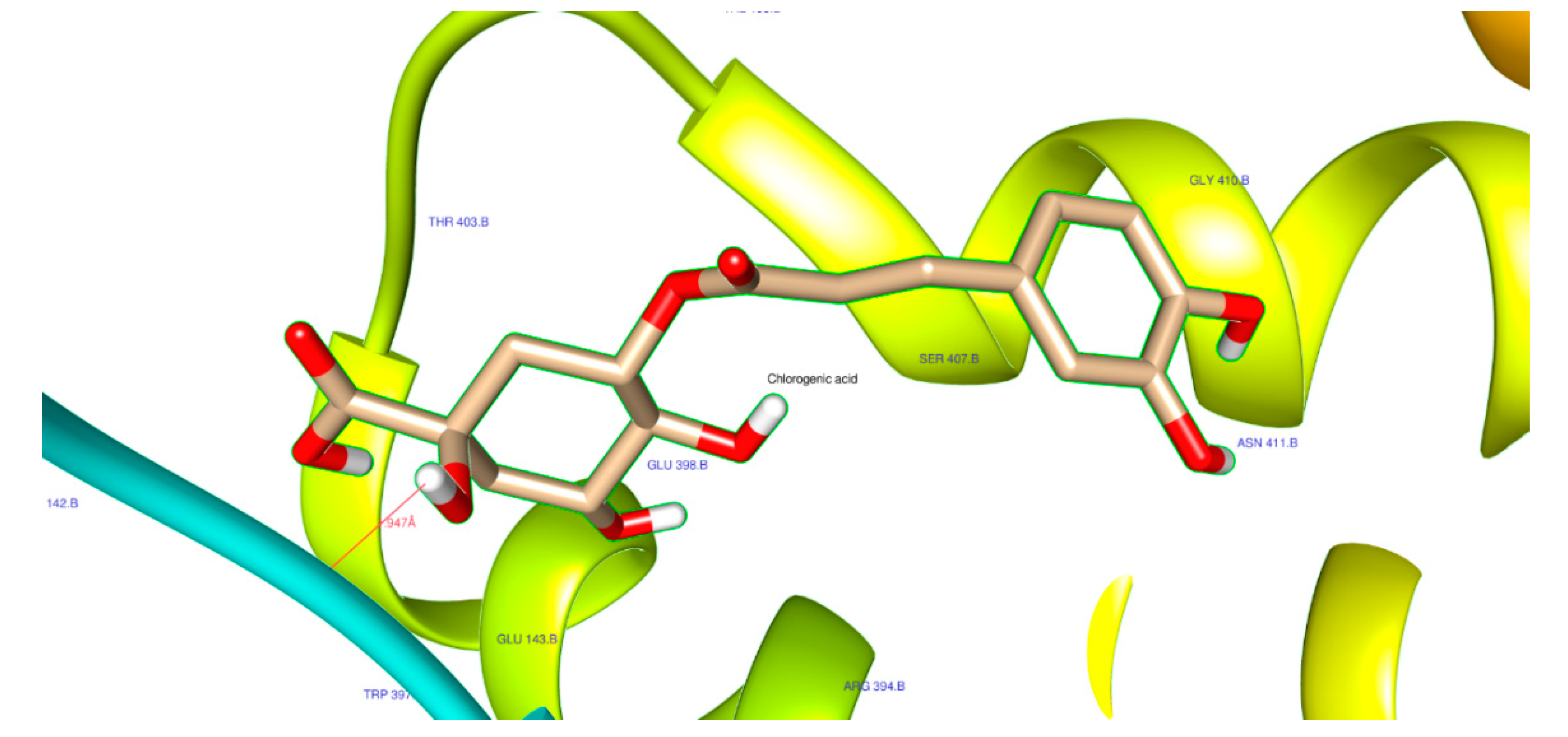

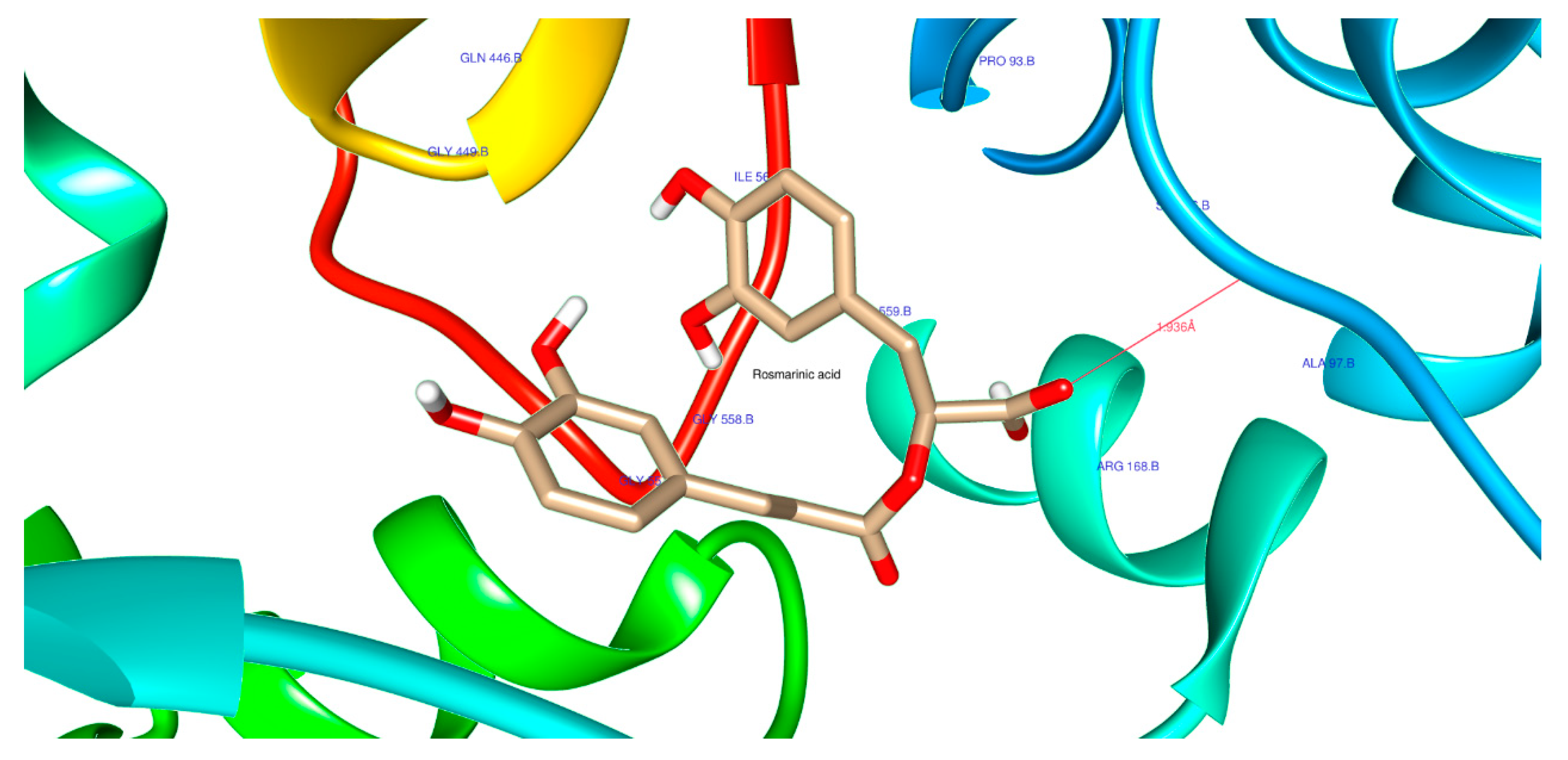

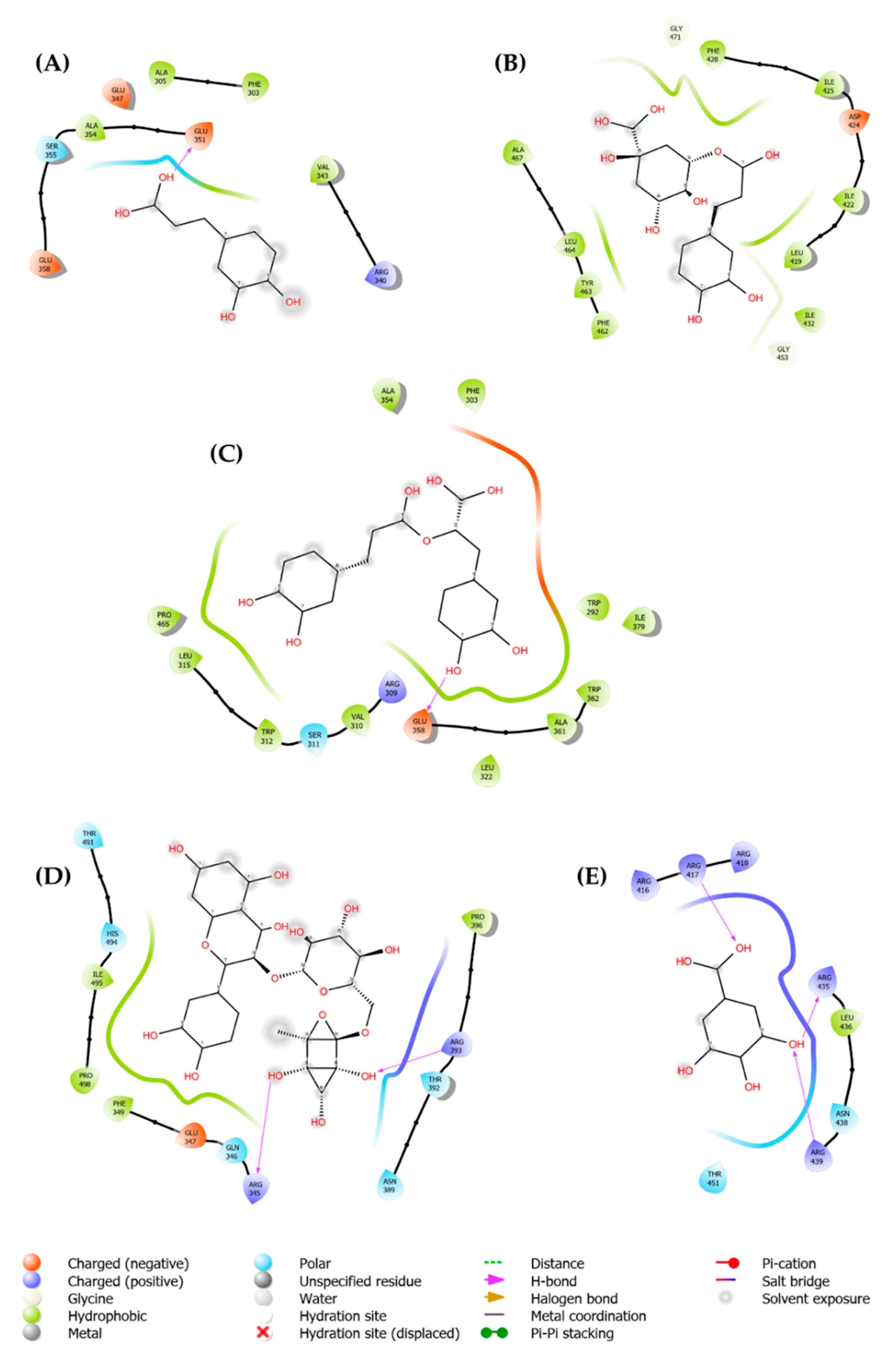

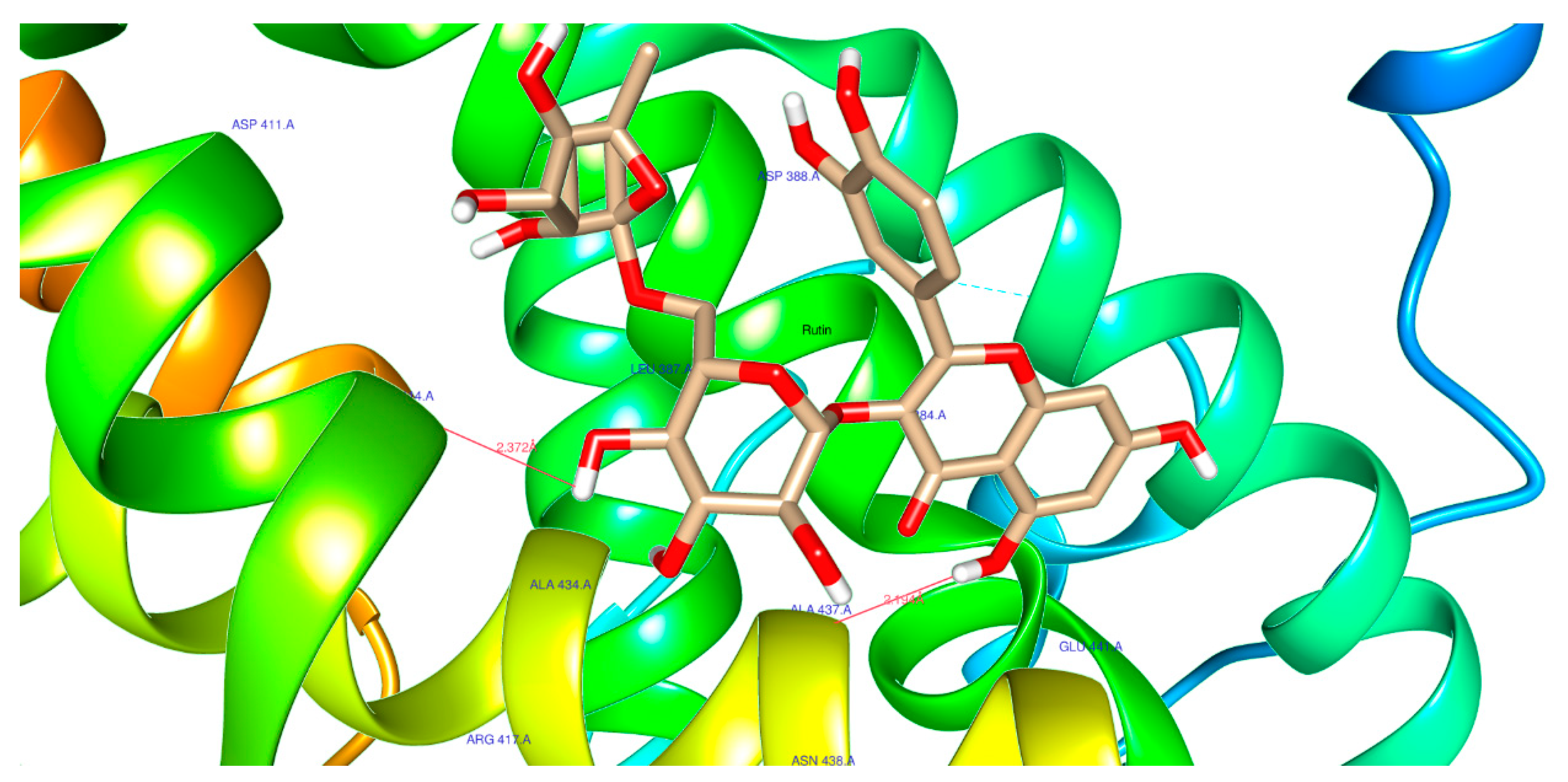

2.3. Molecular Docking Analysis

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Selection, Collection, and Stabilization of Plant Drugs

4.3. Ethnobotanical Study

4.4. Identification of Phytometabolites Polyphenolics from Medicinal Plants Referred to in the Literature and Their Antiviral Activity

4.5. Identification of Polyphenols by UPLC–PDA–ESI–MS/MS

4.6. In Silico Antiviral Activity

4.6.1. Ligand preparation

4.6.2. Protein preparation

4.6.3. Molecular docking

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lim, S.; Jeong, I.; Cho, J.; Shin, C.; Kim, K.I.; Shim, B.S.; Ko, S.G.; Kim, B. The natural products targeting on allergic rhinitis: from traditional medicine to modern drug discovery. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, B.; Wolfender, J.L.; Dias, D. A. The pharmaceutical industry and natural products: historical status and new trends. Phytochem. Rev. 2015, 14, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, S.; Tiezzi, A.; Laghezza Masci, V.; Ovidi, E. Natural products for human health: An historical overview of the drug discovery approaches. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 1926–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, A.R.; Chia, S.L.; Looi, Q.H.; Omar, A.R.; Noordin, M.M.; Ideris, A. Chapter 7 - Herbal extracts as antiviral agents. In Feed Additives; Florou-Paneri, P., Christaki, E., Giannenas, I., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 115–132. [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, S.; Ahmed, S.; Ali, A.; Xue, M.; Ali, L.; Hamza, M.; Munir, A.; Ur, R.S.; Mehmood, K.A.; Hussain, S.A.; Bai, Q. In silico analysis of quranic and prophetic medicinals plants for the treatment of infectious viral diseases including corona virus. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 3137–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.K.; Micali, M.; Rana, B.K.; Pellerito, A.; Singla, R.K. Relevance of ayurveda. therapy of holistic application and classification of herbs. In Indian Herbal Medicines: Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties; Sharma, R.K., Micali, M., Rana, B.K., Pellerito, A., Singla, R.K., Eds.; SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, A.; Oliveira-Miranda, M.A.; Velázquez, D. La investigación etnobotánica sobre plantas medicinales: Una revisión de sus objetivos y enfoques actuales. Interciencia 2005, 30, 453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Lalama, A.J.M.; Montes, C.S.; Zaldumbide, V.M.A. Etnobotánica de plantas medicinales en el cantón Tena, para contribuir al conocimiento, conservación y valoración de la diversidad vegetal de la región Amazónica. Dominio Las Cienc. 2016, 2, 26–52. [Google Scholar]

- Thanh, L.T.; Andreadakis, Z.; Kumar, A.; Gómez, R.R.; Tollefsen, S.; Saville, M.; Mayhew, S. The Covid-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.; Gaoue, O.G. Alkaloid-poor plant families, Poaceae and Cyperaceae, are over-utilized for medicine in Hawaiian pharmacopoeia. Econ. Bot. 2017, 71, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutal, D.H.; Kunwar, R.M.; Uprety, Y.; Adhikari, Y.P.; Bhattarai, S.; Adhikari, B.; Kunwar, L.M.; Bhatt, M.D.; Bussmann, R.W. Selection of medicinal plants for traditional medicines in Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2021, 17, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, A.D.M.; Cevallos, D.; Gaoue, O.G.; Fadiman, M.G.; Hindle, T. Non-random medicinal plants selection in the Kichwa community of the Ecuadorian amazon. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 246, 112220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutal, D.; Kunwar, R.M.; Baral, K.; Sapkota, P.; Sharma, H.P.; Rimal, B. Factors that influence the plant use knowledge in the middle mountains of Nepal. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0246390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.C.S.; Junior, N.J.P.B.; Serejo, A.P.M.; Costa, I.S.; Neto, A.C.O.; Godinho, J.W.L.S.; Kzam, P.M.; Amaral, F.M.M. Espécies vegetais de uso popular no tratamento da dor: uma revisão sistemática. Res. Soc. Dev. 2022, 11, e22511225608–e22511225608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güçlü, İ.; Yüksel, V. Fitoterapide antiviral bitkiler. Deney. Tıp Araşt. Enstitüsü Derg. 2017, 7, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Denaro, M.; Smeriglio, A.; Barreca, D.; De Francesco, C.; Occhiuto, C.; Milano, G.; Trombetta, D. Antiviral activity of plants and their isolated bioactive compounds: An update. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 742–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaccho-Rojas, J.; Balladares, A.; Yanac-Tellería, W.; Rodríguez, C.; Villar-López, M. Review of antiviral and immunomodulatory effects of herbal medicine with reference to pandemic COVID-19. Arch. Venez. de Farmacol. y Ter. 2020, 795–807. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, M.; Tahir, I.M.; Shah, S.M.A.; Mahmood, Z.; Altaf, A.; Ahmad, K.; Munir, N.; Daniyal, M.; Nasir, S.; Mehboob, H. Antiviral potential of medicinal plants against HIV, HSV, influenza, hpatitis, and coxsackievirus: A systematic review. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Sand, L.; Bormann, M.; Schmitz, Y.; Heilingloh, C.S.; Witzke, O.; Krawczyk, A. Antiviral active compounds derived from natural sources against herpes simplex viruses. Viruses 2021, 13, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K. Quality control and evaluation of herbal drugs: evaluating natural products and traditional medicine; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2019; pp. 599–628. [Google Scholar]

- Tida, M.M.A.; Nanjarisoa, O.; Rabearivony, J.; Ranarijaona, H.L.T.; Fenoradosoa, T.A. Ethnobotanical survey of plant species used in traditional medicine in Bekaraoka region, northeastern Madagascar. Int. J. Adv. Res. Publ. 2020, 4, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf, T.; Rafique, S.; Wahid, F.; Rehman, S.; Nazir, A.; Rafique, J.; Aslam, K.; Shabir, G.; Shah, S.M. Phytochemical profiling and antiviral activity of Ajuga bracteosa, Ajuga parviflora, Berberis lycium and Citrus lemon against hepatitis C virus. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 118, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenn, V.; Bosone, C.; Burkard, T.R.; Spanier, J.; Kalinke, U.; Calistri, A.; Salata, C.; Christoff, R.R.; Garcez, P.P.; Mirazimi, A.; Knoblich, J.A. Organoid modeling of zika and herpes simplex virus 1 infections reveals virus-specific responses leading to microcephaly. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 1362–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, G.; Lee, C.K.; Lam, L.T.M.; Yan, B.; Chua, Y.X.; Lim, A.Y.N.; Phang, K.F.; Kew, G.S.; Teng, H.; Ngai, C.H.; Lin, L.; Foo, R.M.; Pada, S.; Ng, L.C.; Tambyah, P.A. Covert COVID-19 and false-positive dengue serology in Singapore. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolta, R.; Yadav, R.; Salaria, D.; Trivedi, S.; Imran, M.; Sourirajan, A.; Baumler, D.J.; Dev, K. In silico screening of hundred phytocompounds of ten medicinal plants as potential inhibitors of nucleocapsid phosphoprotein of Covid-19: An approach to prevent virus assembly. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 7017–7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, J.P.; Sasse, F.; Brönstrup, M.; Diez, J.; Meyerhans, A. Antiviral drug discovery: Broad-spectrum drugs from nature. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 32, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, J.M.J.; Kalaimathi, K.; Vijayakumar, S.; Varatharaju, G.; Karthikeyan, K.; Thiyagarajan, G.; Bhavani, K.; Manogar, P.; Prabhu, S. Anti-viral effectuality of plant polyphenols against mutated dengue protein NS2B47-NS3: A computational exploration. Gene Rep. 2022, 27, 101546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandscheer, C.B.; Duque, J.E.; da Silva, M.A.N.; Fukuyama, Y.; Wohlke, J.L.; Adelmann, J.; Fontana, J.D. Larvicidal action of ethanolic extracts from fruit endocarps of Melia azedarach and Azadirachta indica against the dengue mosquito Aedes aegypti. Toxicon 2004, 44, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, V.D.; Bharadwaj, S.; Afroz, S.; Khan, N.; Ansari, M.A.; Yadava, U.; Tripathi, R.C.; Tripathi, I.P.; Mishra, S.K.; Kang, S.G. Anti-dengue infectivity evaluation of bioflavonoid from Azadirachta indica by dengue virus serine protease inhibition. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 1417–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.B.; Liu, X.C.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Z.L. Essential oil composition and larvicidal activity of Clinopodium Gracile (Benth) Matsum (Labiatae) aerial parts against the Aedes Albopictus Mosquito. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 12, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, K.; Murugan, P.; Noortheen, A. Larvicidal and repellent potential of Albizzia amara boivin and Ocimum basilicum Linn against dengue vector, Aedes aegypti (Insecta:diptera:culicidae). Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonwera, M.; Sittichok, S. Adulticidal activities of Cymbopogon citratus (stapf.) and Eucalyptus globulus (labill.) essential oils and of their synergistic combinations against Aedes Aegypti (L.), Aedes Albopictus (Skuse), and Musca Domestica (L.). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 20201–20214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, R.C.; Sharma, S.; Garg, A.; Ghosh, S. Virus-induced gene silencing in sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum). in virus-induced gene silencing in plants: methods and protocols; Courdavault, V., Besseau, S., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer US: New York, NY, 2020; pp. 123–138. [CrossRef]

- Kanna, S.U.; Krishnakumar, N. Anti-dengue medicinal plants: A mini review. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 8, 4245–4249.

- Procópio, T.F.; Fernandes, K.M.; Pontual, E.V.; Ximenes, R.M.; Oliveira, A.R.C.; Souza, C.S.; Melo, A.M.M.A.; Navarro, D.M.A.F.; Paiva, P.M.G.; Martins, G.F.; Napoleão, T.H. Schinus Terebinthifolius leaf extract causes midgut damage, interfering with survival and development of Aedes Aegypti larvae. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseghai, G.B.; Belay, T.G.; Gebremariam, A.H. Mosquito repellent finishing of cotton using pepper tree (Schinus molle) seed oil extract. J. Text. Sci. Eng. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, N.; Faccin-Galhardi, L.C.; Espada, S.F.; Pacheco, A.C.; Ricardo, N.M.P.S.; Linhares, R.E.C.; Nozawa, C. Sulfated polysaccharide of Caesalpinia ferrea inhibits herpes simplex virus and poliovirus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 60, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, L.C.; Chiang, W.; Liu, M.C.; Lin, C.C. In vitro antiviral activities of Caesalpinia Pulcherrima and its related flavonoids. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 52, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, P.K.; Agrawal, C.; Blunden, G. Pharmacological significance of hesperidin and hesperetin, two Citrus flavonoids, as promising antiviral compounds for prophylaxis against and combating COVID-19. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2021, 16, 1934578X211042540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, A.; Barnard, L.; Pickrell, C. Review of whole plant extracts with activity against herpes simplex viruses in vitro and in vivo. J. Evid.-Based Integr. Med. 2021, 26, 2515690X20978394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, C.; Reichling, J.; Schnitzler, P. Essential oils inhibit replication of herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2. Bot. Med. Clin. Pract. 2008, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.B.S.; Valentim, I.B.; Rocha, T.S.; Santos, J.C.; Pires, K.S.N.; Tanabe, E.L.L.; Borbely, K.S.C.; Borbely, A.U.; Goulart, M.O.F. Schinus terebenthifolius Raddi extracts: from sunscreen activity toward protection of the placenta to zika virus infection, new uses for a well-known medicinal plant. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 152, 112503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocchi, S.R.; Ferreira, L.A.O.; Castro-Hoshino, L.V.; Truiti, M.C.T.; Natali, M.R.M.; Mello, J.C.P.; Baesso, M.L.; Dias, F.B.P.; Nakamura, C.V.; Ueda-Nakamura, T. Development and evaluation of topical formulations that contain hydroethanolic extract from Schinus Terebinthifolia against HSV-1 infection. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 58, e18637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocchi, S.R.; Companhoni, M.V.P.; Mello, J.C.P. de; Filho, B.P.D.; Nakamura, C.V.; Carollo, C.A.; Silva, D.B.; Ueda-Nakamura, T. Antiviral activity of crude hydroethanolic extract from Schinus Terebinthifolia against herpes simplex virus type 1. Planta Med. 2017, 234, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holidah, D.; Dewi, I.P.; Siregar, I.P.A.; Aftiningsih, D. Hepatoprotective effect of Caesalpinia Sappan L. ethanolic extract on alloxan induced diabetic rats: J. Farm. Galen. Galen. J. Pharm. E-J. 2022, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaurav, S.; Jeyabalan, G.; Anil, A. Antioxidant and skeletal muscle relaxant activity of leaf extract of plant Piper Attenuatum (B. HAM). Indian J. Pharm. Biol. Res. 2021, 9, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Reyes, S.G.; Villarreal-La Torre, V.E.; Silva-Correa, C.R.; Sagastegui, G.W.A.; Cruzado-Razco, J.L.; Gamarra-Sánchez, C.D.; Venegas, C.E.A.; Miranda-Leyva, M.; Valdiviezo, C.J.E.; Armando, C.C. Hepatoprotective activity of Cordia lutea Lam flower extracts against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Pharmacogn. J. 2021, 13, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Hayashi, T.; Morita, N.; Niwayama, S. Antiviral activity of an extract of Cordia Salicifolia on herpes simplex virus type 1. Planta Med. 1990, 56, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Ijaz, B.; Fatima, N.; Muhammad, S.A.; Riazuddin, S. Therapeutic potential of Taraxacum officinale against HCV NS5B polymerase: In vitro and in silico study. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 83, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Morris-Natschke, S.L.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Li, R.T. Development of anti-influenza agents from natural products. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 2290–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, A.; Saluja, A.K.; Kumar, M.; Atri, P. Antiviral activity of plant polyphenols. J. Pharm. Res. 2012, 5, 2402–2412. [Google Scholar]

- Badshah, S.L.; Faisal, S.; Muhammad, A.; Poulson, B.G.; Emwas, A.H.; Jaremko, M. Antiviral activities of flavonoids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh, A; Ghasemzadeh, N. Flavonoids and phenolic acids: role and biochemical activity in plants and human. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, K.; Jagtap, G.; Magdum, S. A Comprehensive review on herbal drug standardization. Am. J. PharmTech Res. 2019, 9, 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungmunnithum, D.; Thongboonyou, A.; Pholboon, A.; Yangsabai, A. Flavonoids and other phenolic compounds from medicinal plants for pharmaceutical and medical aspects: An overview. Medicines 2018, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Sayed, K.A. Natural products as antiviral agents. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta-ur-Rahman, Ed.; Bioactive Natural Products (Part E); Elsevier, 2000; Volume 24, pp. 473–572. [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.W.; Ernst, E. Antiviral agents from plants and herbs: A systematic review. Antivir. Ther. 2003, 8, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghildiyal, R.; Prakash, V.; Chaudhary, V.K.; Gupta, V.; Gabrani, R. Phytochemicals as antiviral agents: recent updates. In plant-derived bioactives: production, properties and therapeutic applications; Swamy, M.K., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, L.R.F.; Wu, H.; Nebo, L.; Fernandes, J.B.; da Silva, M.F.G.F.; Kiefer, W.; Kanitz, M.; Bodem, J.; Diederich, W.E.; Schirmeister, T.; Vieira, P.C. Flavonoids as noncompetitive inhibitors of dengue virus NS2B-NS3 protease: Inhibition kinetics and docking studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Kim, N.M.; Park, J.S.; Jang, T.S.; Kim, D. Inhibitory effect of flavonoids against NS2B-NS3 protease of zika virus and their structure activity relationship. Biotechnol. Lett. 2017, 39, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, S.; Feierberg, I.; Wang, T.; Blomberg, N.; Wade, R.C. Comparative binding energy analysis for binding affinity and target selectivity prediction. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2010, 78, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Bock, S.; Snitko, M.; Berger, T.; Weidner, T.; Holloway, S.; Kanitz, M.; Diederich, W. E.; Steuber, H.; Walter, C.; Hofmann, D.; Weißbrich, B.; Spannaus, R.; Acosta, E.G.; Bartenschlager, R.; Engels, B.; Schirmeister, T.; Bodem, J. Novel dengue virus NS2B/NS3 protease inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herowati, R.; Widodo, G.P.; Herowati, R.; Widodo, G.P. Chapter 5: Molecular docking analysis: interaction studies of natural compounds to anti-inflammatory targets; Kandemirli, F., Eds.; IntechOpen, 2017, pp. 63–73. [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.S.; Mottin, M.; de Assis, L.R.; Mesquita, N.C.M.R.; Sousa, B.K.P.; Coimbra, L.D.; Santos, K.B.; Zorn, K.M.; Guido, R.V.C.; Ekins, S.; Marques, R.E.; Proença-Modena, J.L.; Oliva, G.; Andrade, C.H.; Regasini, L.O. Flavonoids from Pterogyne Nitens as zika virus NS2B-NS3 protease inhibitors. Bioorganic Chem. 2021, 109, 104719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trujillo-Correa, A.I.; Quintero-Gil, D.C.; Diaz-Castillo, F.; Quiñones, W.; Robledo, S.M.; Martinez-Gutierrez, M. In vitro and in silico anti-dengue activity of compounds obtained from Psidium Guajava through Bioprospecting. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassandarvish, P.; Rothan, H.A.; Rezaei, S.; Yusof, R.; Abubakar, S.; Zandi, K. In silico study on baicalein and baicalin as inhibitors of dengue virus replication. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 31235–31247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadl, N.; Salem, T.Z. Hepatitis C genotype 4: A report on resistance-associated substitutions in NS3, NS5A, and NS5B genes. Rev. Med. Virol. 2020, 30, e2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.R.; Waly, N.G.F. M.; El-Baky, R.M.A.; Yahia, R.; Hetta, H.F.; Elsayed, A.M.; Ibrahem, R.A. Distribution of naturally occurring NS5B resistance-associated substitutions in Egyptian patients with chronic hepatitis C. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0249770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, E.; Ren, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Small molecule NS5B RdRp non-nucleoside inhibitors for the treatment of HCV infection: A medicinal chemistry perspective. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 240, 114595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, G.; Majid, M.; Ghaffar, A.; Yameen, M.; Samad, H.; Mahrosh, H. Screening and molecular docking of selected phytochemicals against NS5B polymerase of hepatitis C virus. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 33, 2317–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akher, F.B.; Farrokhzadeh, A.; Ramharack, P.; Shunmugam, L.; van Heerden, F. R.; Soliman, M.E.S. Discovery of novel natural flavonoids as potent antiviral candidates against hepatitis C virus NS5B polymerase. Med. Hypotheses 2019, 132, 109359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabi, I.I.; Mohinuddin, M.; Abir, A.Y.; Koo, S.; Alam, D.M.S. In-silico investigations on the antiviral activity of some polyphenolic derivatives: chemical reactivity descriptors, ADMET, QSAR and molecular docking studies against hepatitis C virus NS5B polymerase. Rochester, NY November 11, 2022. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4267458 (accessed 2023-02-27).

- Lakshmi, M.V.; Swapna, T.S.A. Computational study on cosmosiin, an antiviral compound from Memecylon randerianum S.M.Almeida & M.R.Almeida. Med. Plants - Int. J. Phytomedicines Relat. Ind. 2021, 13, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunnicliffe, R.B.; Hu, W.K.; Wu, M.Y.; Levy, C.; Mould, A.P.; McKenzie, E.A.; Sandri-Goldin, R.M.; Golovanov, A.P. Molecular mechanism of SR protein kinase 1 inhibition by the herpes virus protein ICP27. mBio 2019, 10, e02551–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandri-Goldin, R.M. The many roles of the highly interactive HSVprotein ICP27, a key regulator of infection. Future Microbiol. 2011, 6, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hennig, T.; Whisnant, A.W.; Erhard, F.; Prusty, B.K.; Friedel, C.C.; Forouzmand, E.; Hu, W.; Erber, L.; Chen, Y.; Sandri-Goldin, R.M.; Dölken, L.; Shi, Y. Herpes simplex virus blocks host transcription termination via the bimodal activities of ICP27. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borenstein, R.; Hanson, B.A.; Markosyan, R.M.; Gallo, E.S.; Narasipura, S.D.; Bhutta, M.; Shechter, O.; Lurain, N.S.; Cohen, F.S.; Al-Harthi, L.; Nicholson, D.A. Ginkgolic acid inhibits fusion of enveloped viruses. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Abu, H.S.H.; Elghandour, M.M.Y.; Kanth, R.P.R.; Salem, M.Z.M.; Anele, U.Y.; Ranga, R.P.P.; Salem, A.Z.M. Influence of Corymbia Citriodora leaf extract on growth performance, ruminal fermentation, nutrient digestibility, plasma antioxidant activity and faecal bacteria in young calves. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 261, 114394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treml, J.; Gazdová, M.; Šmejkal, K.; Šudomová, M.; Kubatka, P.; Hassan, S.T.S. Natural products derived chemicals: Breaking barriers to novel anti-HSV drug development. Viruses 2020, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Gao, Z.Q.; Majerciak, V.; Bai, L.; Hu, M.L.; Lin, X.X.; Zheng, Z.M.; Dong, Y.H.; Lan, K. The crystal structure of KSHV ORF57 reveals dimeric active sites important for protein stability and function. PLOS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunnicliffe, R.B.; Collins, R.F.; Ruiz, N.H.D.; Sandri-Goldin, R.M.; Golovanov, A.P. The ICP27 homology domain of the human cytomegalovirus protein UL69 adopts a dimer of dimers structure. mBio 2018, 9, e01112–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir-Hassan, A.; Lee, V.S.; Baharuddin, A.; Othman, S.; Xu, Y.; Huang, M.; Yusof, R.; Rahman, N.; Othman, R. Conformational and energy evaluations of novel peptides binding to dengue virus envelope protein. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2017, 74, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittinger, E.; Inhester, T.; Bietz, S.; Meyder, A.; Schomburg, K.T.; Lange, G.; Klein, R.; Rarey, M. Large scale analysis of hydrogen bond interaction patterns in protein ligand interfaces. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 4245–4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R.; Selvaraj, C.; Aarthy, M.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, A.; Singh, S.K.; Giri, R. Investigating into the molecular interactions of flavonoids targeting NS2B-NS3 protease from zika virus through in silico approaches. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, R.S.G.; Venegas, C.E.A.; Valdiviezo, C.J.E.; Ocaña, V.J.P.; Tadeo, H.M.A.V. Características farmacognósticas y cuantificación espectrofotométrica de antocianinas totales del fruto de Prunus serotina subsp. capuli (Cav.) McVaugh (Rosaceae) “capulí.” Arnaldoa 2018, 25, 961–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussmann, R.W.; Zambrana, P.; Narel, Y.; Sikharulidze, S.; Kikvidze, Z.; Kikodze, D.; Tchelidze, D.; Batsatsashvili, K.; Hart; Robbie, E. Ethnobotany of Samtskhe-Javakheti, Sakartvelo (Republic of Georgia), Caucasus. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2017, 16, 7–24.

- Zambrano-Intriago, L.F.; Buenaño-Allauca, M.P.; Mancera-Rodríguez, N.J.; Jiménez-Romero, E. Estudio etnobotánico de plantas medicinales utilizadas por los habitantes del área rural de la Parroquia San Carlos, Quevedo, Ecuador. Univ. Salud 2015, 17, 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero-Segura, N.A.; Gomez-Verjan, J.C. In silico screening of natural products isolated from Mexican herbal medicines against COVID-19. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Sohn, S.I.; Sathasivam, R.; Khaskheli, A.J.; Kim, M.C.; Kim, N.S.; Park, S.U. Targeted metabolic and in silico analyses highlight distinct glucosinolates and phenolics signatures in Korean rapeseed cultivars. Plants 2021, 10, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithilesh, S.; Raghunandan, D.; Suresh, P.K. In silico identification of natural compounds from traditional medicine as potential drug leads against SARS-CoV-2 through virtual screening. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 92, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zahar, H.; Menze, E.T.; Handoussa, H.; Osman, A.K.; El-Shazly, M.; Mostafa, N.M.; Swilam, N. UPLC-PDA-MS/MS profiling and healing activity of polyphenol rich fraction of Alhagi maurorum against oral ulcer in rats. Plants 2022, 11, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminformatics 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open babel: an open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminformatics 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Chen, C.; Lei, X.; Zhao, J.; Liang, J. CASTp 3.0: Computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W363–W367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhachoo, J.; Beuming, T. Investigating protein peptide interactions using the schrödinger computational suite. In Modeling Peptide-Protein Interactions: Methods and Protocols; Schueler-Furman, O., London, N., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, 2017; pp. 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, S.K.; Ahmad, I.; Shathi, J.F.; Mim, M.M.; Hassan, M.R.; Jewel, M.J.I.; Dey, P.; Islam, M.S.; Patel, H.; Morshed, M.R.; Shakil, M.S.; Hossen, M.S. A Comprehensive study to unleash the putative inhibitors of serotype2 of dengue virus: insights from an in silico structure-based drug discovery. Mol. Biotechnol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant species | Family | Vernacular name 1 | HUT code 2 | Type of viral affection |

Part used 1 | Way of preparation 1 |

Way of use 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azadirachta indica A. Juss. | Meliaceae | Paraíso | 60828 | Mosquito-borne | Le | Inf | A liter, three times a day |

|

Caesalpinia spinosa (Molina) Kuntze |

Fabaceae | Tara | 60820 | Dermatological, respiratory | Po, WP | Inf, De, Wa, Ba | Gargle, two times a day Wa, Ba: a time a day |

| Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck | Rutaceae | Limón | 60821 | Hepatic, dermatological, respiratory, COVID-19 | Le, Fr | Inf, Ba | Time water |

| Clinopodium pulchellum (Kunth) Govaerts | Lamiaceae | Panizara | 60830 | Mosquito-borne | WP | Inf, De | Time water |

| Cordia lutea Lam. | Boraginaceae | Overo | 60823 | Hepatic | Fl | Inf, De | A liter, three times a day |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Lamiaceae | Albahaca | 60826 | Respiratory, COVID-19, Mosquito-borne | WP | Inf, Ba | A liter, three times a day Ba: A time a day |

| Schinus molle L. | Anacardaceae | Molle | 60836 | Dermatological, respiratory, mosquito-borne | Le, Se, WP | Inf, Ba, Ru | A liter, three times a day Ba: three times a week |

| Taraxacum campylodes G. E. Haglund | Asteraceae | Diente de león | 60838 | Hepatic, respiratory, COVID-19 | AP, WP | Inf, De | A liter as time water |

| Virus | Plant species | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Denge virus | Azadirachta indica | [28,29] |

| Clinopodium gracile | [30] | |

| Ocimum basilicum | [31,32,33] | |

| Schinus molle | [34,35,36] | |

| Herpes simplex virus | Caesalpinia ferrea | [37] |

| Caesalpinia pucherrima | [38] | |

| Citrus limon | [39,40,41] | |

| Schinus terebinthifolia | [42,43,44] | |

| Hepatitis virus | Caesalpinia crista | [45] |

| Caesalpinia sappan | [46] | |

| Citrus limon | [22] | |

| Cordia lutea | [47,48] | |

| Taraxacum officinale | [49] |

| No | Rt (Min) | Chemical formula | [M-H]- (m/z) |

Fragment ions (m/z) |

Identified compound |

Plant species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.87 | C7H6O5 | 169 | 125, 78, 69 | Gallic acid |

Azadirachta indica Caesalpinia spinosa |

| 2 | 3.89 | C16H18O9 | 353 | 191, 179 | Chlorogenic acid |

Clinopodium pulchellum Schinus molle Taraxacum compylodes |

| 3 | 5.97 | C9H8O4 | 179 | 135, 107 | Caffeic acid |

Azadirachta indica Ocimun basilicum Taraxacum compylodes |

| 4 | 10.31 | C27H30O16 | 609 | 301, 169 | Rutin |

Azadirachta indica Citrus limon Clinopodium pulchellumCordia lutea Schinus molle |

| 5 | 13.91 | C18H16O8 | 359 | 197, 179, 161 | Rosmarinic acid | Clinopodium pulchellum Ocimun basilicum |

| Pubchem ID | Ligand | Parameters | DENV-2 (PDB: 2FOM) |

HCV (PDB: 4EO6) |

HSV-1 (PDB: 4YXP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1794427 | Chlorogenic acid | Score | -8.6 | -8.2 | -6.8 |

| H-Bonds | 4 | 3 | 0 | ||

| N. torsions | 11 | 11 | 11 | ||

| Bindig residues | TRP83, LEU149 | ASN142, GLU398, ASN411 |

- | ||

| 5280805 | Rutin | Score | -7.1 | -9.9 | -7.8 |

| H-Bonds | 2 | 2 | 3 | ||

| N. torsions | 16 | 16 | 16 | ||

| Bindig residues | GLY153(2) | ASP444, GLY557 | ARG345, ARG393 | ||

| 0370 | Gallic acid | Score | -5.7 | -5.9 | -5.6 |

| H-Bonds | 2 | 0 | 3 | ||

| N. torsions | 5 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Bindig residues | ALA164, ASN152 | - | ARG417, ARG435, ARG439 | ||

| 5281792 | Rosmarinic acid | Score | -7.9 | -7.9 | -6.8 |

| H-Bonds | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||

| N. torsions | 12 | 12 | 12 | ||

| Bindig residues | ALA164, LEU149 | ALA97, GLY449 | GLU358 | ||

| 689043 | Caffeic acid | Score | -6.2 | -6.1 | -5.7 |

| H-Bonds | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| N. torsions | 5 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Bindig residues | LEU149 | - | GLU351 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).