Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

23 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

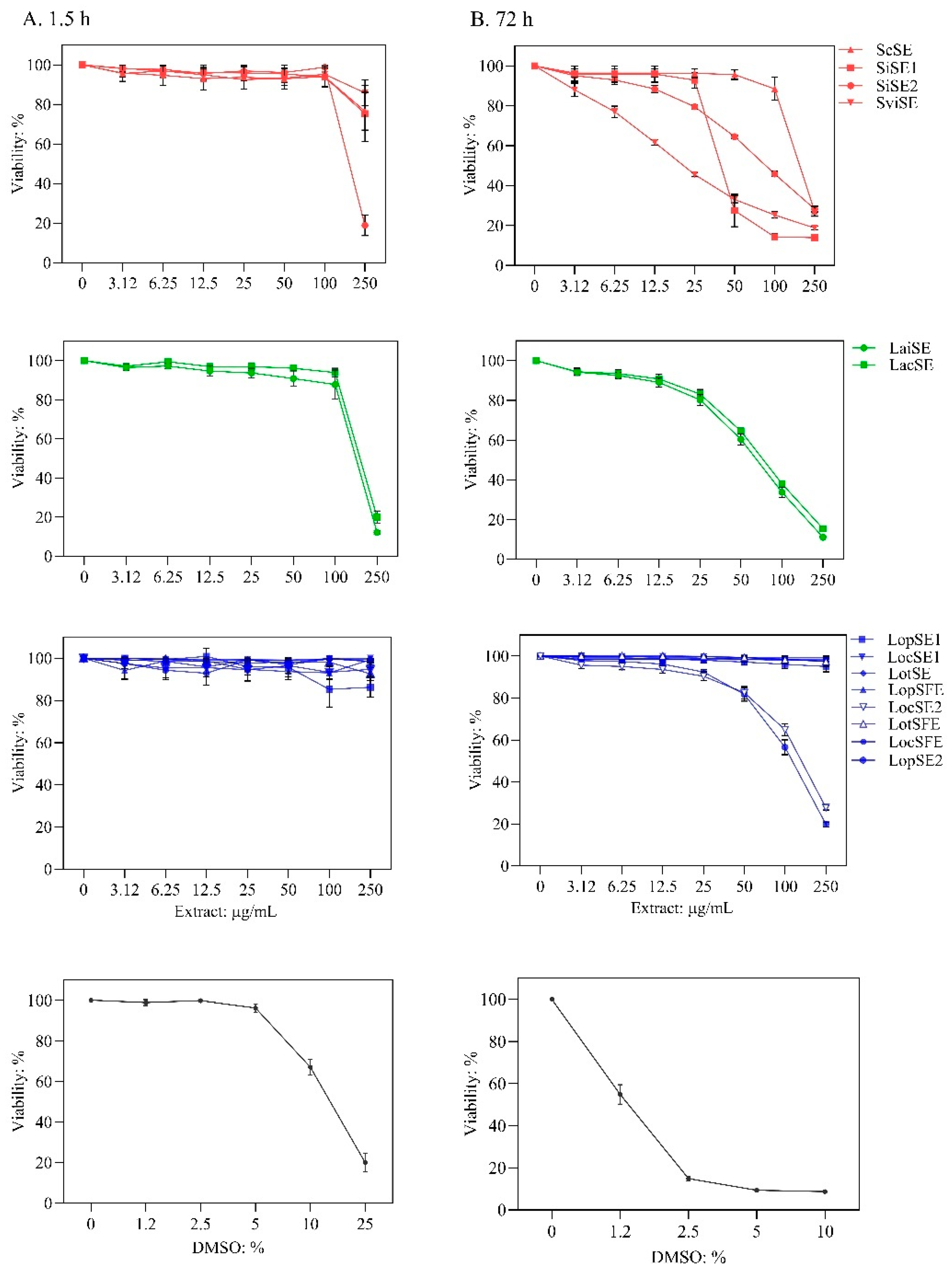

2.1. Cytotoxicity

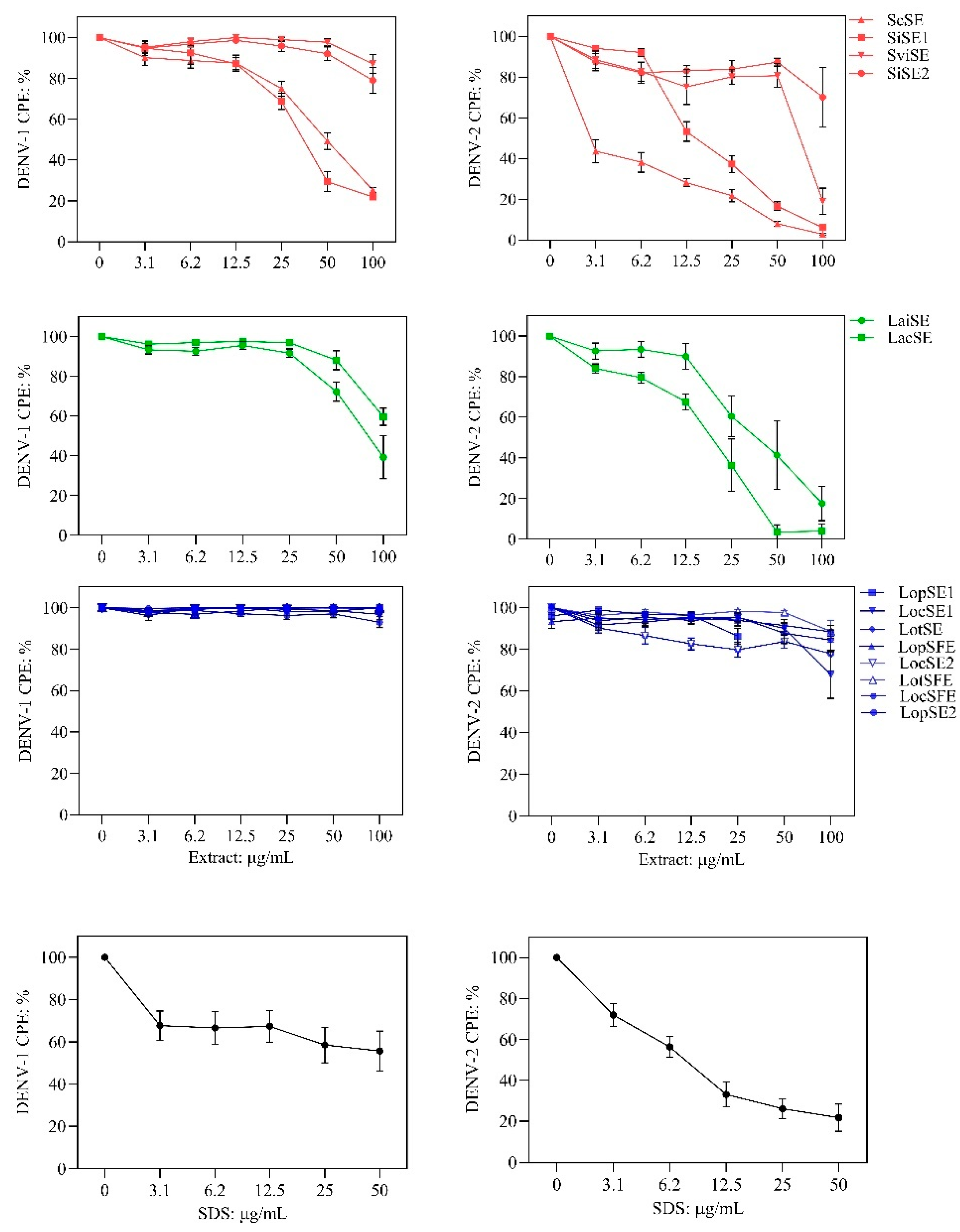

2.2. Antiviral Effect

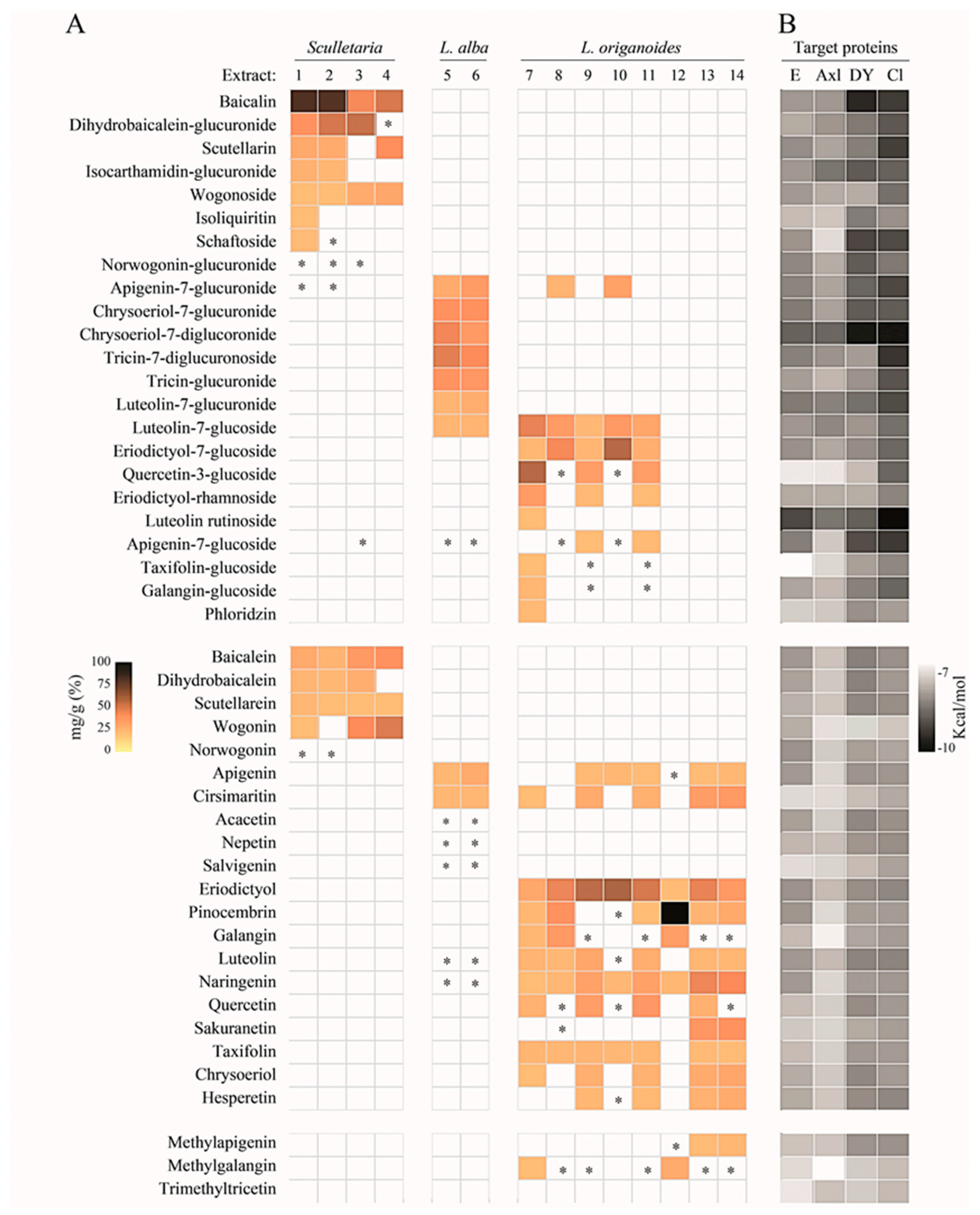

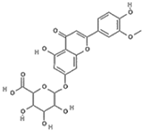

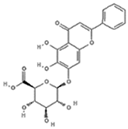

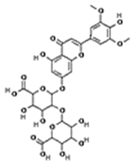

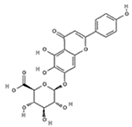

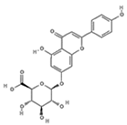

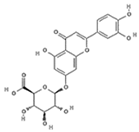

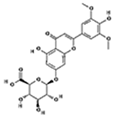

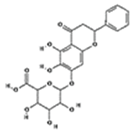

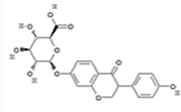

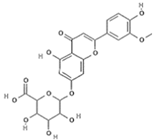

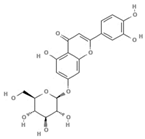

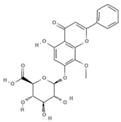

2.3. UHPLC/ESI-Q-Orbitrap-MS Analysis of the Extracts Prepared in This Study

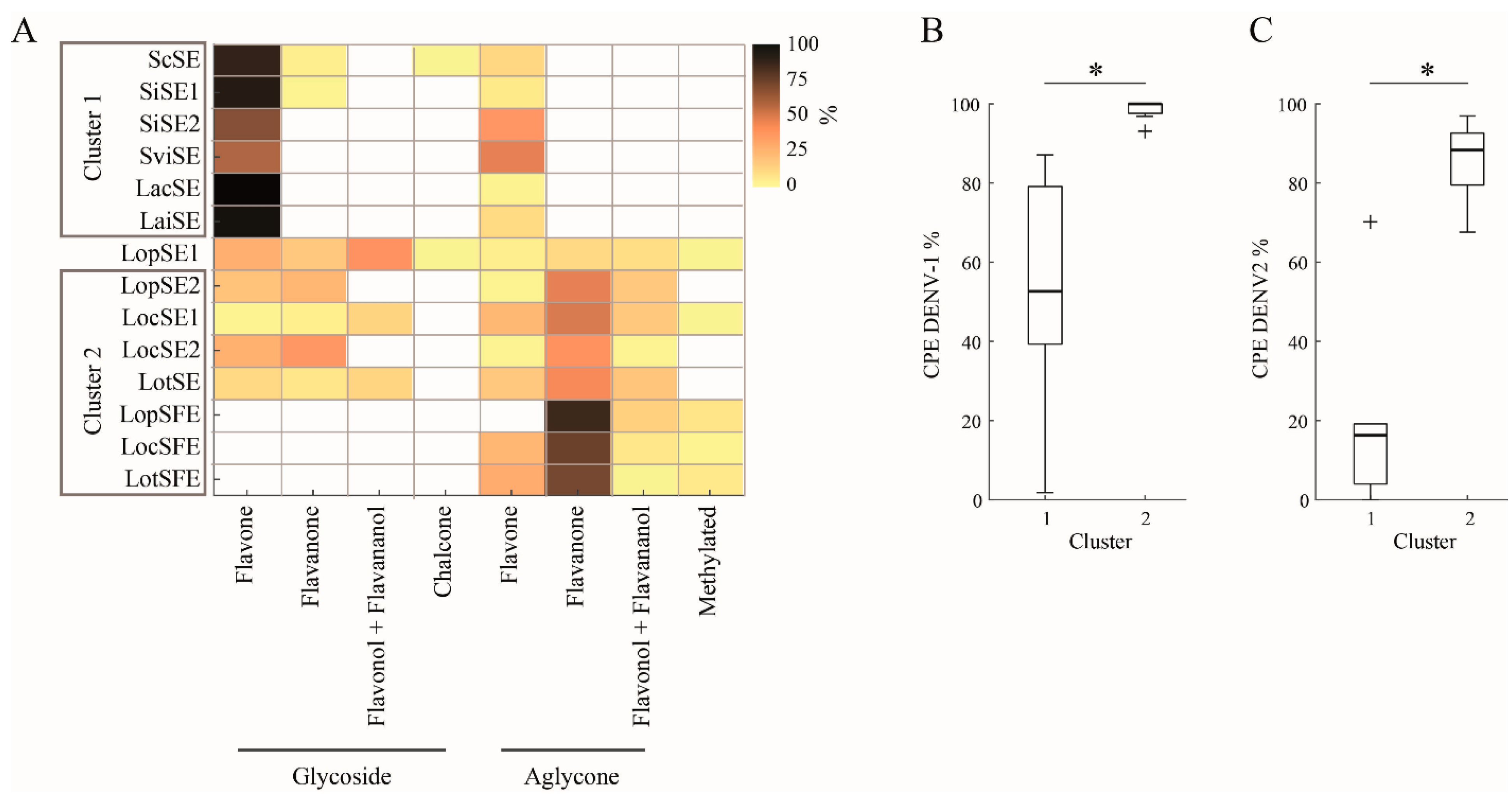

2.4. Relationship Between Anti-DENV Effect and the Flavonoid Content

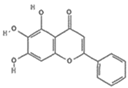

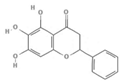

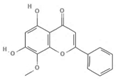

2.5. Molecular Interactions Between Flavonoids and DENV and Vero Cell Proteins

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Viruses and Cell

4.3. Extracts

4.4. UHPLC/ESI-Q-Orbitrap-MS Analysis

4.5. Crystal Violet Assays

4.6. Cytopathic Effect (CPE)-Based Antiviral Assay

4.7. Molecular Docking Analysis

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Ooi, E.E.; Horstick, O.; Wills, B. Dengue. The Lancet. 2019, 393, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Dengue epidemiological situation in the region of the Americas, epidemiological week 35, 2025. PAHO: Washington, D.C. 2025. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/dengue-epidemiological-situation-region-americas-epidemiological-week-35-2025 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Obi, J.O.; Gutiérrez-Barbosa, H.; Chua, J.V.; Deredge, D.J. Current trends and limitations in dengue antiviral research. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2021, 30, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanichamy Kala, M.; St John, A.L.; Rathore, A.P.S. Dengue: update on clinically relevant therapeutic strategies and vaccines. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2023, 15, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, B.; Ahmed, A.; Khan, S.; et al. Exploring plant-based dengue therapeutics: from laboratory to clinic. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2024, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, S.; de Silva, N.L.; Weeratunga, P.; Rodrigo, C.; Sigera, C.; Fernando, S.D. Carica papaya extract in dengue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019, 11, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeosun, W.B.; Loots, D.T. Medicinal Plants against Viral Infections: A Review of Metabolomics Evidence for the Antiviral Properties and Potentials in Plant Sources. Viruses. 2024, 31, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Qian, S.; Wang, X.; Si, T.; Xu, J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Q.; Yang, Y.; Rong, R. UPLC-Q-Exactive/MS based analysis explore the correlation between components variations and anti-influenza virus effect of four quantified extracts of Chaihu Guizhi decoction. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 30, 319, 117318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Yuan, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, B. Comparison of different methods for extraction of Cinnamomi ramulus: yield, chemical composition and in vitro antiviral activities, Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 24, 2909–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badshah, S.L.; Faisal, S.; Muhammad, A.; Poulson, B.G.; Emwas, A.H.; Jaremko, M. Antiviral activities of flavonoids. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loaiza-Cano, V.; Monsalve-Escudero, L.M.; Filho, C.D.S.M.B.; Martinez-Gutierrez, M.; Sousa, D.P. Antiviral role of phenolic compounds against dengue virus: A Review. Biomolecules. 2020, 24, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Li, P.; Liu, S.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; He, C.; Xiao, P. Traditional uses, ten-years research progress on phytochemistry and pharmacology, and clinical studies of the genus Scutellaria. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 30, 265, 113198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wang, M.; Wang, M.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, X.; Guo, H.; He, R.; Luo, Z. Scutellaria baicalensis: a promising natural source of antiviral compounds for the treatment of viral diseases. Chin J Nat Med. 2023, 21, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, S. Verbenaceae: the families and genera of fowering plants. Berlin: Springer; 2004, 7, 449–68. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, M.E.; Slowing, K.; Carretero, E.; Mata, D.S.; Villar, A. Lippia: traditional uses, chemistry and pharmacology: a review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 76, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennebelle, T.; Sahpaz, S.; Joseph, H.; Bailleul, F. Ethnopharmacology of Lippia alba. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 5, 116, 211–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, D.R.; Leitão, G.G.; Fernandes, P.D.; Leitã, S.G. Ethnopharmacological studies of Lippia origanoides. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia. 2014, 24, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun-Or-Rashid, A. N. M.; Sen, M. K.; Jamal, M. A. H. M.; Nasrin, S. A comprehensive ethnopharmacological review on Lippia alba M. Int. J Biomed. Mater. Res. 2013, 1, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zandi, K.; Lim, T.H.; Rahim, N.A.; Shu, M.H.; Teoh, B.T.; Sam, S.S.; Danlami, M.B.; Tan, K.K.; Abubakar, S. Extract of Scutellaria baicalensis inhibits dengue virus replication. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013, 29, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Rueda, E.; Velandia, S.A.; Ocazionez, R.E.; Stashenko, E.E.; Rondón-Villarreal, P. Comparative anti-dengue activities of ethanolic and supercritical extracts of Lippia origanoides Kunth: in-vitro and in-silico analyses. Recs Nat Prod. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, J.; Mejía, J.; Córdoba, Y.; Martínez, J.R.; Stashenko, E.E.; del Valle, J.M. Optimization of flavonoids extraction from Lippia graveolens and Lippia origanoides chemotypes with ethanol-modified supercritical CO2 after steam distillation, Ind. Crops. and Prod. 2020, 146, 112170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, S.M.; Saavedra, R.A.; Sierra, L.J.; González, R.T.; Martínez, J.R.; Stashenko, E.E. Chemical characterization and determination of the antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds in three Scutellaria sp. plants grown in Colombia. Molecules. 2023, 14, 28, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, W.L.; Moreno, E.M.; Pinto, S.M.L.; Sanabria, S.M.; Stashenko, E.; García, L.T. Immunomodulatory, trypanocide, and antioxidant properties of essential oil fractions of Lippia alba (Verbenaceae). BMC Complement Med Ther. 2021, 2, 21, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stashenko, E.E.; Martínez, J.R.; Cala, M.P.; Durán, D.C.; Caballero, D. Chromatographic and mass spectrometric characterization of essential oils and extracts from Lippia (Verbenaceae) aromatic plants. J Sep Sci. 2013, 36, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Morales, A.J.; López-Medina, E.; Arboleda, I.; Cardona-Ospina, J.A.; Castellanos, J.E.; Faccini-Martínez, Á.A.; Gallagher, E.; Hanley, R.; Lopez, P.; Mattar, S.; Pérez, C.E.; Kastner, R.; Reynales, H.; Rosso, F.; Shen, J.; Villamil-Gómez, W.E.; Fuquen, M. The epidemiological impact of dengue in Colombia: a systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2024, 29, 112, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pájaro-González, Y.; Oliveros-Díaz, A.F.; Cabrera-Barraza, J.; CerraDominguez, J.; Díaz-Castillo, F. Chapter 1- A review of medicinal plants used as antimicrobials in Colombia. In: Chassagne, F. (Ed.). Medicinal Plants as Anti-Infectives. Academic Press. 2022; pp. 3–57.

- Smee, D.F.; Hurst, B.L.; Evans, W.J.; Clyde, N.; Wright, S.; Peterson, C.; Jung, K.H.; Day, C.W. Evaluation of cell viability dyes in antiviral assays with RNA viruses that exhibit different cytopathogenic properties. J Virol Methods. 2017, 246, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.F.; Almeida, M.P.; Leite, M.F.; Schwaiger, S.; Stuppner, H.; Halabalaki, M.; Amaral, J.G.; David, J.M. Seasonal variation in the chemical composition of two chemotypes of Lippia alba. Food Chem. 2019, 273, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.Z.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Robbins, R.J.; Harnly, J.M. Identification and quantification of flavonoids of Mexican oregano (Lippia graveolens) by LC-DAD-ESI/MS analysis. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2007, 20, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolin-Trindade, G.; Perez-Pinheiro, G.; Silva, A.A.R.; Porcari, A.M.; Sawaya, A.C.H.F. Sources of variation of the chemical composition of Lippia origanoides Kunth (Verbenaceae). Nat Prod Res. 2025, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center. The NIST Mass Spectral Search Program. Standard Reference Data Program of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S.A.; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Timóteoa, P.; Kariotia, A.; Leitãob, S.G.; Vincieri, F.F.; Bilia, A.R. HPLC/DAD/ESI-MS Analysis of non-volatile constituents of three Brazilian chemotypes of Lippia alba (Mill.) N. E. Brown. Nat Prod Com. 2008, 3, 12, 2017–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, R.; Shen, H.; Wang, M.; Yin, Z.; Cheng, A. Structures and functions of the envelope glycoprotein in flavivirus infections. Viruses. 2017, 13, 9, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meertens, L.; Carnec, X.; Lecoin, M.P.; Ramdasi, R.; Guivel-Benhassine, F.; Lew, E.; Lemke, G.; Schwartz, O.; Amara, A. The TIM and TAM families of phosphatidylserine receptors mediate dengue virus entry. Cell Host Microbe. 2012, 12, 544–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Oliveira, C.; Freire, J.M.; Conceição, T.M.; Higa, L.M.; Castanho, M.A.; Da Poian, A.T. Receptors and routes of dengue virus entry into the host cells. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2015, 39, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccini, L.E.; Castilla, V.; Damonte, E.B. Dengue-3 Virus Entry into Vero Cells: Role of Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis in the Outcome of Infection. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0140824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, E.G.; Castilla, V.; Damonte, E.B. Alternative infectious entry pathways for dengue virus serotypes into mammalian cells. Cell Microbiol. 2009, 11, 1533–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhausen, T.; Owen, D.; Harrison, S.C. Molecular structure, function, and dynamics of clathrin-mediated membrane traffic. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014, 6, a016725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, C. B.; Popoff, M. R.; McCluskey, A.; Robinson, P. J.; Meunier, F. A. Targeting membrane trafficking in infection prophylaxis: dynamin inhibitors. Trends in Cell Biology. 2013, 23(2), 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.R.; Tsai, T.T.; Chen, C.L.; et al. Blockade of dengue virus infection and viral cytotoxicity in neuronal cells in vitro and in vivo by targeting endocytic pathways. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Pang, S.; Zhong, M.; Sun, Y.; Qayum, A.; Liu, Y.; Rashid, A.; Xu, B.; Liang, Q.; Ma, H.; Ren, X. A comprehensive review of ultrasonic assisted extraction (UAE) for bioactive components: Principles, advantages, equipment, and combined technologies. Ultrason Sonochem. 2023, 101, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Hu, W.; Wang, A.; Xiu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Hao, K.; Sun, X.; Cao, D.; Lu, R.; Sun, J. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of total flavonoids from Pteris cretica L.: Process Optimization, HPLC Analysis, and Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019, 24, 8, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwineza, P.A.; Waśkiewicz, A. Recent advances in supercritical fluid extraction of natural bioactive compounds from natural plant materials. Molecules. 2020, 25, 3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J. Dietary flavonoid aglycones and their glycosides: Which show better biological significance? Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017, 57, 1874–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, E.; Teoh, BT.; Sam, SS.; Lani, R.; Hassandarvish, P.; Chik, Z.; Yueh, A.; Abubakar, S.; Zandi, K. Baicalin, a metabolite of baicalein with antiviral activity against dengue virus. Sci Rep. 2014, 4, 5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.T.; Suárez, A.I.; Serrano, M.L.; et al. The role of the glycosyl moiety of myricetin derivatives in anti-HIV-1 activity in vitro. AIDS Res Ther. 2017, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourfarzad, F.; Gheibi, N.; Namdar, P.; Gholamzadeh-Khoei, S.; Gheibi, N. Flavonoids antiviral effects: focusing on entry inhibition of influenza and coronavirus. J Inflamm Dis. 2024, 28, e153347. [Google Scholar]

- Naresh, P.; Selvaraj, A.; Shyam Sundar, P.; Murugesan, S.; Sathianarayananan, S.; Namboori P. K, K.; Jubie, S. Targeting a conserved pocket (n-octyl-β-D–glucoside) on the dengue virus envelope protein by small bioactive molecule inhibitors. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn 2022, 40, 4866–4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waiba, A.; Phunyal, A.; Lamichhane, TR.; Ghimire, MP.; Nyaupane, H.; Phuyal, A.; et al. Computational insights into flavonoids inhibition of dengue virus envelope protein: ADMET profiling, molecular docking, dynamics, PCA, and end-state free energy calculations. PLoS One. 2025, 20, e0327862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, M.; Lei, X.; Huang, M.; Ye, W.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, D. Luteolin inhibits angiogenesis by blocking Gas6/Axl signaling pathway. Int J Oncol. 2017, 51, 2, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkafaas, S.S.; Abdallah, A.M.; Ghosh, S.; Loutfy, S.A.; Elkafas, S.S.; Abdel-Fattah, N.F.; Hessien, M. Insight into the role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis inhibitors in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Rev Med Virol. 2023, 33, e2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapral-Piotrowska, J.; Strawa, J.W.; Jakimiuk, K.; Wiater, A.; Tomczyk, M.; Gruszecki, WI.; Pawlikowska-Pawlęga, B. Investigation of the membrane localization and interaction of selected flavonoids by NMR and FTIR Spectroscopy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 15275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Trujillo, L.; Quintero-Rueda, E.; Stashenko, E.E.; Conde-Ocazionez, S.; Rondón-Villarreal, P.; Ocazionez, R.E. Essential Oils from Colombian Plants: Antiviral Potential against Dengue Virus Based on Chemical Composition, In Vitro and In Silico Analyses. Molecules. 2022, 27, 6844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Acevedo, V.; Ocazionez, R.E.; Stashenko, E.E.; Silva-Trujillo, L.; Rondón-Villarreal, P. Comparative virucidal activities of essential oils and alcohol-based solutions against enveloped virus surrogates: in vitro and in silico analyses. Molecules 2023, 28, 4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohonen, T.; Somervuo, P. How to make large self-organizing maps for nonvectorial data. Neural Networks 2002, 15, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Plant | Voucher | Extract code | Extraction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technique | Conditions | |||

| Scutellaria coccineaKunth | UIS219784 | ScSE | UAE | 15 min; 50 oC |

| Scutellaria incarnata Vent | UIS219783 | SiSE1 | UAE | 5 min; 50 oC |

| SiSE2 | UAE | 60 min; 50 oC | ||

| Scutellaria ventenatii + incarnata (hybrid) | UIS219785 | SviSE | UAE | 60 min; 50 oC |

| Lippia alba (Mill) N.E. Brown | UIS22031a | LacSE | UAE | 60 min; 50 oC |

| UIS22002b | LaiSE | UAE | 60 min; 50 oC | |

| Lippia origanoides Kunth | UIS22035c | LopSE1 | UAE | 23 min; 47 oC |

| LopSE2 | UAE | 60 min; 50 oC | ||

| LopSFE | SFE | 96 min; 307 bar | ||

| UIS22034d | LocSE1 | UAE | 23 min; 47 oC | |

| LocSE2 | UAE | 60 min; 50 oC | ||

| LocSFE | SFE | 96 min; 307 bar | ||

| UIS19799e | LotSE | UAE | 23 min; 47 oC | |

| LotSFE | SFE | 96 min; 307 bar | ||

| Extract Code |

CC50: µg/mL |

DENV-1 | DENV-2 | Effect | |||||

| CPE % |

IC50: µg/mL |

SI |

CPE: % |

IC50: µg/mL |

SI |

||||

| ScSEa | 213 ± 1.1 | 25 ± 1.2 | 52 ± 1.3 | 4.1 | 2.9 ± 0.45 | 3 ± 1.3 | 71 | Strong | |

| SiSE1a | 50 ± 1.2 | 22 ± 1.4 | 39 ± 1.2 | 1.2 | 6.1 ± 0.97 | 17 ± 1.2 | 2.9 | Strong | |

| SiSE2a | 91 ± 1.05 | 79 ± 6.5 | - | - | 70 ± 14.7 | - | - | Inactive | |

| SviSEa | 23 ± 2.0 | 87 ± 4.7 | - | - | 19 ± 6.5 | 65 ± 1.2 | 0.4 | Weak | |

| LaiSEb | 65 ± 1.1 | 39 ± 10.8 | 81 ± 1.1 | 0.8 | 17 ± 8.4 | 38 ± 1.2 | 1.7 | Weak | |

| LacSEb | 75 ± 1.0 | 60 ± 4.3 | - | - | 4 ± 3.7 | 19 ± 1.1 | 3.9 | Weak | |

| LopSE1c | >250.0 | 100 | - | - | 86 ± 3.7 | - | - | Inactive | |

| LopSE2c | 117 ± 1.0 | 93 ± 2.7 | - | - | 77 ± 8.4 | - | - | Inactive | |

| LopSFEc | >250.0 | 100 | - | - | 94 ± 3.2 | - | - | Inactive | |

| LocSE1c | >250.0 | 100 | - | - | 67 ± 11.2 | - | - | Inactive | |

| LocSE2c | 143 ± 1.1 | 100 | - | - | 88 ± 3.2 | - | - | Inactive | |

| LocSFEc | >250.0 | 96 ± 2.5 | - | - | 96 ± 2.0 | - | - | Inactive | |

| LotSEc | >250.0 | 100 | - | - | 84 ± 4.9 | - | - | Inactive | |

| LotSFEc | >250.0 | 99 ± 0.2 | - | - | 88 ± 5.2 | - | - | Inactive | |

| Name | Formula | Exp. Masses [M+H]+ |

Δ ppm |

HCD, eV | Product ions | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product ions Fragment type |

Formula | (m/z) | ||||||

| Apigenin-7-glucoside | C2120O10 | 433.11287 | 0.11 | 30 | [(M+H)−C6H10O5]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−CO]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−C8H6O]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−C8H6O3]+ |

C15H11O5 C15H9O4 C14H11O4 C7H5O4 C7H5O2 |

271.06012 253.04997 243.06558 153.01848 121.02852 |

[19,22] |

| Apigenin-7-glucuronide | C21H18O11 | 447.09056 | 0.54 | 20 | [(M+H)−C6H8O6]+ [(M+H)−C6H8O6−C8H6]+ |

C15H11O5 C7H5O5 |

271.06033 169.01256 |

[19,22] |

| Baicalin | C21H18O11 | 447.09056 | 0.33 | 20 | [(M+H)−C6H8O6]+ [(M+H)−C6H8O6−C8H6]+ |

C15H11O5 C7H5O5 |

271.06033 169.01256 |

[19,22] |

| Chrysoeriol-7-diglucuronide | C28H28O18 | 653.13484 | 0.50 | 20 | [(M+H)−C6H8O6]+ [(M+H)−2C6H8O6]+ |

C22H21O12 C16H13O6 |

477.10275 301.07066 |

[28,31] |

| Chrysoeriol-7-glucuronide | C22H20O12 | 477.10275 | 0.20 | 20 | [(M+H)−C6H8O6]+ | C16H13O6 | 301.07066 | [28,31] |

| Dihydrobaicalein-glucuronide | C21H20O11 | 449.10602 | 0.44 | 10 | [(M+H−)C6H8O6]+ [(M+H)−C6H8O6−C8H8]+ [(M+H)−C6H8O6−C6H6O4]+ |

C15H13O5 C7H5O5 C9H7O |

273.07538 169.01341 131.04932 |

[22] |

| Eriodictyol-7-glucoside | C21H22O11 | 451.12327 | 0.48 | 10 | [(M+H)−C6H10O5]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−C8H8O2]+ |

C15H13O6 C15H11O5 C7H5O4 |

289.07062 271.05969 153.01810 |

[29,30] |

| Luteolin-7-glucuronide | C21H18O12 | 463.08710 | 1.57 | 30 | [(M+H)−C6H7O6]+ [(M+H)−C6H7O6−H2O]+ |

C21H17O12 C20 13CH17O12 C21H17O11 18O |

461,07211 462,07553 463,07739 |

[29,30] |

| Eriodictyol-rhamnoside | C21H22O10 | 435.12845 | 0.28 | 30 | [(M+H)−C6H10O4]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O4−H2O]+ [(M+H) −C6H10O4−H2O−C6H4O2]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O4−C8H8O2]+ |

C15H13O6 C15H11O5 C9H7O3 C7H5O4 |

289.07086 271.05937 163.03883 153.01846 |

[29] |

| Galangin- glucoside | C21H20O10 | 433.11287 | 0.11 | 20 | [(M+H)−C6H10O5]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−C2H2O]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−C6H4O2]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−C8H6O]+ |

C15H11O5 C13H9O4 C9H7O3 C7H5O4 |

271.06012 229.04935 163.03894 153.01825 |

[20,29] |

| Luteolin-7-glucoside | C21H20O11 | 449.10791 | 1.07 | 20 | [(M+H)−C6H10O5]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−C2H2O]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−C6H4O2]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−C8H6O2]+ |

C15H11O6 C13H9O5 C9H7O4 C7H5O4 |

287.05515 245.04386 179.03411 153.01846 |

[29,30] |

| Luteolin-rutinoside | C27H30O15 | 595.16524 | 0.86 | 10 | [(M+H)−C6H10O4]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O4−C6H10O5]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O4−C6H10O5−C8H6O2]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O4−C6H10O5−C8H6O3]+ |

C21H21O11 C15H11O6 C7H5O4 C7H5O3 |

449.10864 287.05530 153.01832 137.02325 |

[29,30] |

| Phloridzin | C21H24O10 | 437.14386 | 0.82 | 10 | [(M+H)−C6H10O5]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−C7H6O]+ |

C15H15O5 C15H13O4 C8H9O4 |

275.09131 257.08081 169.04961 |

[20,31] |

| Quercetin-3-glucoside | C21H20O12 | 465.10287 | 0.35 | 10 | [(M+H)−C6H10O5]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−C8H6O3]+ |

C15H11O7 C15H9O6 C7H5O4 |

303.04971 285.03970 153.01811 |

[20] |

| Scutellarin | C21H18O12 | 463.08762 | 0.42 | 10 | [(M+H)−C6H8O6]+ [(M+H)−C6H8O6−C6H4O3]+ |

C15H11O6 C9H7O3 |

287.05537 163.03885 |

[22] |

| Taxifolin-glucoside | C21H22O12 | 467.11829 | 0.24 | 20 | [(M+H)−C6H10O5]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C6H10O5−C8H8O3]+ |

C15H13O7 C15H11O6 C7H5O4 |

305.06561 287.05496 153.01832 |

[20] |

| Tricin-7-diglucuronoside | C29H30O19 | 683.14540 | 0.28 | 30 | [(M+H)−C6H8O6]+ [(M+H)−2C6H8O6]+ |

C23H23O13 C17H15O7 |

507.11331 331.08122 |

[31,32] |

| Tricin-glucuronide | C23H22O13 | 507.11331 | 1.03 | 20 | [(M+H)−C6H8O6]+ | C17H15O7 | 331.08063 | [31,32] |

| Wogonoside | C22H20O11 | 461.17773 | 0.47 | 20 | [(M+H)−C6H8O6]+ [(M+H)−C6H8O6−CH3]+• |

C16H13O5 C15H10O5 |

285.07535 270.05164 |

[22] |

| Acacetin | C16H12O5 | 285.07541 | 1.19 | 50 | [(M+H)−CH3]+• [(M+H)−CH3−CO]+• [(M+H)−C9H8O]+ [(M+H)−C8H6O4]+ |

C15H10O5 C14H10O4 C7H5O4 C8H7O |

270.05273 242.05754 153.01842 119.049228 |

[30,31] |

| Apigenin | C15H10O5 | 271.06042 | 0.82 | 40 | [(M+H)−H2O]+ [(M+H)−CO]+ [(M+H)−C8H6O]+ |

C15H9O4 C14H11O4 C7H5O4 |

253.04997 243.06558 153.01848 |

[21,22] |

| Baicalein | C15H10O5 | 271.05969 | 1.50 | 60 | [(M+H)−H2O]+ [(M+H)−H2O−CO]+ [(M+H)−C8H6]+ [(M+H)−C8H6−CO]+ [(M+H)−C8H6−CO−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C7H4O5]+ |

C15H9O4 C14H9O3 C7H5O5 C6H5O4 C6H3O3 C8H7 |

253.04919 225.05435 169.01305 141.01811 123.00773 103.04451 |

[19,22] |

| Chrysoeriol | C16H12O6 | 301.07036 | 0.99 | 30 | [(M+H)−CH3]+• [(M+H)−CH3−CO]+• [(M+H)−C9H8O2]+ [(M+H)−C7H4O4]+ [(M+H)−C8H6O5]+ |

C15H10O6 C14H10O5 C7H5O4 C9H9O2 C8H7O |

286.04718 258.05222 153.01855 149.05977 119.04939 |

[20,21] |

| Cirsimaritin | C17H14O6 | 315.08605 | 0.83 | 30 | [(M+H)−CH3]+• [(M+H)−2CH3]+• [(M+H)−CH3−H2O]+• [(M+H)−CH3−H2O−CO]+• [(M+H)−CH3−H2O−2CO]+• [(M+H)−C8H6O]+ |

C16H12O6 C15H9O6 C16H10O5 C15H10O4 C14H10O3 C9H9O5 |

300.06265 285.03961 282.05215 254.05727 226.06232 197.04445 |

[20,21] |

| Dihydrobaicalein | C15H12O5 | 273.07617 | 0.41 | 40 | [(M+H)−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C2H2O]+ [(M+H)−C8H8]+ [(M+H)−C6H6O4]+ |

C15H11O4 C13H11O4 C7H5O5 C9H7O |

255.06465 231.06482 169.01292 131.04906 |

[22] |

| Eriodictyol | C15H12O6 | 289.07105 | 0.57 | 20 | [(M+H)−H2O]+ [(M+H)−H2O−CO]+ [(M+H)−C6H6O2]+ [(M+H)−H2O−C6H4O2]+ [(M+H)−C8H8O2]+ |

C15H11O5 C14H11O4 C9H7O4 C9H7O3 C7H5O4 |

271.05969 243.05995 179.03374 163.03882 153.01810 |

[20,21] |

| Galangin | C15H10O5 | 271.06051 | 0.49 | 30 | [(M+H)−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C2H2O]+ [(M+H)−C6H4O2]+ [(M+H)−C8H6O]+ [(M+H)−C6H6O3]+ |

C15H9O4 C13H9O4 C9H7O3 C7H5O4 C9H5O2 |

253.04956 229.04935 163.03894 153.01825 145.02840 |

[20,21] |

| Hesperetin | C16H14O6 | 303.08620 | 0.35 | 20 | [(M+H)−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C2H2O]+ [(M+H)−C7H8O2]+ [(M+H)−C9H10O2]+ [(M+H)−C7H4O4]+ |

C16H13O5 C14H13O5 C9H7O4 C7H5O4 C9H11O2 |

285.07529 261.07568 179.03389 153.01828 151.07553 |

[20,21] |

| Luteolin | C15H10O6 | 287.05556 | 0.92 | 30 | [(M+H)−C2H2O]+ [(M+H)−C6H4O2]+ [(M+H)−C8H6O2]+ [(M+H)−C8H6O3]+ |

C13H9O5 C9H7O4 C7H5O4 C7H5O3 |

245.04393 179.03409 153.01822 137.02327 |

[21,24] |

| Nepetin | C16H12O7 | 317.06557 | 0.19 | 20 | [(M+H)−H2O]+ [(M+H)−CH2O]+ |

C16H11O6 C15H11O6 |

299.05501 287.05500 |

[30,31] |

| Naringenin | C15H12O5 | 273.07629 | 0.28 | 20 | [(M+H)−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C2H2O]+ [(M+H)−C8H8O]+ [(M+H)−C6H6O]+ [(M+H)−3C2H2O]+ |

C15H11O4 C13H11O4 C7H5O4 C9H7O4 C9H7O2 |

255.06464 231.06487 153.01810 179.03371 147.04393 |

[20,21] |

| Pinocembrin | C15H12O4 | 257.08132 | 0.20 | 20 | [(M+H)−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C2H2O]+ [(M+H)−C6H6]+ [(M+H)−C8H8]+ |

C15H11O3 C13H11O3 C9H7O4 C7H5O4 |

239.06998 215.07010 179.03415 153.01816 |

[21,24] |

| Quercetin | C15H10O7 | 303.05047 | 0.12 | 20 | [(M+H)−H2O]+ [(M+H)−2CO]+ [(M+H)−H2O−2CO]+ [(M+H)−C8H6O3]+ |

C15H9O6 C13H11O5 C13H9O4 C7H5O4 |

285.03787 247.06012 229.04951 153.01836 |

[20,21] |

| Sakuranetin | C16H14O5 | 287.09132 | 0.28 | 20 | (M+H)−C2H2O]+ [(M+H)−C6H6O]+ [(M+H)−C8H8O]+ [(M+H)−C7H8O3]+ |

C14H13O4 C10H9O4 C8H7O4 C9H7O2 |

245.08090 193.04971 167.03386 147.04402 |

[20,21] |

| Salvigenin | C18H16O6 | 329.10144 | 0.52 | 40 | [(M+H)−CH3]+∙ [(M+H)−CH3−H2O]+∙ [(M+H)−CH3−H2O−CO]+∙ |

C17H14O6 C17H12O5 C16H12O4 |

314.07794 296.06750 268.07200 |

[20,21] |

| Taxifolin | C15H12O7 | 305.06548 | 0.30 | 30 | [(M+H)−H2O]+ [(M+H)−H2O−CO]+ [(M+H)−H2O−2CO]+ [(M+H)−H2O−2CO−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C8H8O3]+ |

C15H11O6 C14H11O5 C13H11O4 C13H9O3 C7H5O4 |

287.05487 259.06003 231.06512 213.05463 153.01826 |

[20,21] |

| Scutellarein | C15H10O6 | 287.05444 | 0.57 | 60 | [(M+H)−H2O]+ [(M+H)−H2O−CO]+ [(M+H)−C8H6O]+ [(M+H)−C8H6O−CO]+ [(M+H)−C8H6O−CO−H2O]+ [(M+H)−C7H4O5]+ |

C15H9O5 C14H9O4 C7H5O5 C6H5O4 C6H3O3 C8H7O |

269.04416 241.04912 169.01280 141.01810 123.00771 119.04921 |

[22] |

| Wogonin | C16H12O5 | 285.07575 | 0.49 | 50 | [(M+H)−CH3]+• [(M+H)−CH3−CO]+• |

C15H10O5 C14H10O4 |

270.05176 242.05701 |

[22] |

| Methyl-apigenin | C16H12O5 | 285.07687 | 0.37 | 30 | [(M+H)−CH3]+• [(M+H)−CH3−CO]+• [(M+H)−C9H8O]+ |

C15H10O5 C14H10O4 C7H5O4 |

270.05219 242.05734 153.01848 |

[20,21] |

| Methyl-galangin | C16H12O5 | 285.07563 | 0.42 | 30 | [(M+H)−CH3]+• [(M+H)−CH3−CO]+• [(M+H)−CH3−CO−HCO]+• [(M+H)−C9H8O]+ |

C15H10O5 C14H10O4 C13H9O3 C7H5O4 |

270.05219 242.05734 213.05461 153.01830 |

[21] |

| Trimethyl-tricetin | C18H16O7 | 345.09659 | 0.80 | 30 | [(M+H)−CH3]+• [(M+H)−2CH3]+ [(M+H)−CH3−H2O]+• [(M+H)−CH3−H2O−CO]+• [(M+H)−C11H12O3]+ |

C17H14O7 C16H11O7 C17H12O6 C16H12O5 C7H5O4 |

330.07339 315.05063 312.06262 284.06769 153.01817 |

[20,31] |

| Name | Scutellaria | L. alba | L. origanoides | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiSE2 | SviSE | LacSE | LaiSE | LopSE2 | LocSE1 | LocSE2 | LotSE | |

| Flavonoid glycosides | ||||||||

| Apigenin-7-glucoside | <LOD | - | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.04 ± 0.01 | <LOD | 0.62 ± 0.2 |

| Apigenin-7-glucuronidea | - | - | 1.5 ± 0.09 | 2.3 ± 0.19 | 14 ± 1.00 | - | 27 ± 1.40 | - |

| Baicalin | 15.9 ± 0.02 | 16 ± 0.02 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Chrysoeriol-7-glucuronide | - | - | 3.8 ± 0.05 | 3.5 ± 0.01 | - | - | - | - |

| Chrysoeriol-7-diglucuronide | - | - | 4.9 ± 0.07 | 2.5 ± 0.03 | - | - | - | - |

| Dihydrobaicalein-glucuronidea | 23 ± 0.006 | <LOD | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Eriodictyol-7-glucoside | - | - | - | - | 80 ± 2.00 | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 89 ± 1.30 | 3.2 ± 0.3 |

| Eriodictyol-rhamnoside | - | - | - | - | - | 0.13 ± 0.01 | - | 0.32 ± 0.03 |

| Galangin-glucoside | - | - | - | - | - | <LOD | - | - |

| Luteolin-7-glucoside | - | - | 0.6 ± 0.11 | 0.68 ± 0.04 | 49 ± 1.00 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 35 ± 0.10 | 5.01 ± 0.3 |

| Luteolin-7-glucuronide | - | - | 0.8 ± 0.19 | 1.1 ± 0.33 | - | - | - | - |

| Luteolin-rutinoside | - | - | - | - | - | 0.02 ± 0.01 | - | 0.10 ± 0.01 |

| Quercetin-3-glucoside | - | - | - | - | <LOD | 1.5 ± 0.3 | <LOD | 6.2 ± 0.8 |

| Scutellarin | 11.4 ± 0.03 | 11.4 ± 0.03 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Taxifolin-glucoside | - | - | - | - | - | <LOD | - | <LOD |

| Tricin-glucuronide | - | - | 3.7 ± 0.12 | 2.8 ± 0.03 | - | - | - | - |

| Tricin-7-diglucuronoside | - | - | 5.5 ± 0.13 | 3.8 ± 0.04 | - | - | - | - |

| Wogonoside | 4.7 ± 0.03 | 4.7 ± 0.03 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Phloridzin | - | - | - | - | - | 0.01 ± 0.01 | - | 0.05 ± 0.04 |

|

Flavonoid aglycones |

||||||||

| Acacetin | - | - | <LOD | <LOD | - | - | ||

| Apigenin | - | - | 0.34 ± 0.06 | 1.2 ± 0.39 | - | 0.13 ± 0.01 | ||

| Baicalein | 10.1 ± 0.04 | 10 ± 0.04 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Chrysoeriol | - | - | - | - | - | 0.70 ± 0.04 | ||

| Cirsimaritin | - | - | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.40 ± 0.14 | - | 0.9 ± 0.04 | 4.3 ± 0.10 | 0.38 ± 0.01 |

| Baicalein | 10.1 ± 0.04 | 10 ± 0.04 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Chrysoeriol | - | - | - | - | - | 0.70 ± 0.04 | - | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

| Cirsimaritin | - | - | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.40 ± 0.14 | - | 0.9 ± 0.04 | - | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

| Dihydrobaicaleinc | 4.13 ± 0.007 | <LOD | - | - | - | - | ||

| Eriodictyol | - | - | - | - | 89 ± 1.00 | 4.5 ± 0.03 | ||

| Galangin | - | - | - | - | 50 ± 2.00 | <LOD | ||

| Hesperetin | - | - | - | - | - | 0.17 ± 0.01 | ||

| Luteolin | - | - | <LOD | <LOD | 7.3 ± 0.20 | 1.12 ± 0.05 | ||

| Naringenin | - | - | <LOD | <LOD | 6.0 ± 0.20 | 1.38 ± 0.05 | ||

| Nepetin | - | - | <LOD | <LOD | - | - | ||

| Pinocembrin | - | - | - | - | 71 ± 2.00 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | ||

| Quercetin | - | - | - | - | <LOD | 1.5 ± 0.1 | ||

| Sakuranetin | - | - | - | - | <LOD | 0.32 ± 0.02 | ||

| Salvigenin | - | - | <LOD | <LOD | - | - | ||

| Scutellarein | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.20 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Taxifolin | - | - | - | - | 4.8 ± 0.10 | 0.47 ± 0.02 | ||

| Wogonin | 15.4 ± 0.03 | 15 ± 0.03 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Methylated flavonoids | ||||||||

| Methylapigenin | - | - | - | - | - | 0.03±0.01 | - | |

| Methylgalangin | - | - | - | - | <LOD | <LOD | - | |

| Trimethyltricetin | - | - | - | - | - | 0.03±0.01 | - | |

| Extract |

Antiviral effect |

Total (mg/g) |

Glycoside (%) | Aglycone (%) |

Methylated (%) |

||||||||

| A | B | C | D | A | B | C | |||||||

| ScSE | Strong | 277.86 | 83.4 | 4.1 | 0 | 0.56 | 10.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| SiSE1 | Strong | 492.98 | 86.1 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 5.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| SviSE | Weak | 57.92 | 55.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 44.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| LacSE | Weak | 21.37 | 97.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| LaiSE | Weak | 18.34 | 90.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| SiSE2 | Inactive | 84.92 | 64.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| LopSE1 | Inactive | 27.58 | 24.7 | 15 | 37 | 0.9 | 3.9 | 10.1 | 8.0 | 0.4 | |||

| LopSE2 | Inactive | 371.10 | 17 | 21.6 | 0 | 0 | 2.0 | 44.7 | 14.8 | 0 | |||

| LocSE1 | Inactive | 13.59 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 11.0 | 0.07 | 21.0 | 47.1 | 14.5 | 0.4 | |||

| LocSE2 | Inactive | 259.00 | 23.9 | 34.4 | 0 | 0 | 1.7 | 38.2 | 1.8 | 0 | |||

| LotSE | Inactive | 57.44 | 10 | 6.1 | 10.8 | 0.1 | 15.1 | 41.4 | 16.2 | 0.2 | |||

| LopSFE | Inactive | 62.96 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 81.4 | 11.8 | 6.5 | |||

| LocSFE | Inactive | 19.85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21.4 | 70.7 | 6.0 | 1.9 | |||

| LotSFE | Inactive | 25.90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25.8 | 68.0 | 0.8 | 5.4 | |||

| Name/PubChem CID/formula | Target: site | Amino acids interacting through hydrogen bonds | kcal/mol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chrysoeriol-7-diglucoronide 44258206  |

Cl: W-box | Ser34, Thr158, Gln265, Glu268, Arg157. | -10.01 ± 0.27 | |||

| DY: G4-switch1 | Ser41, Gly60, Lys113, Ala177, Asp180, Leu181, Lys206, Thr214, Asn236, Gln239. | -9.96 ± 0.44 | ||||

| E: DII (A/B) | Trp206, Thr239, His261, Thr265, Glu269, Ile270. | -8.78 ± 0.37 | ||||

| GX: Gas6-Lg1 | Gln78, Ser304, Gly307, Arg308, Leu309, Gln341, Ile426, Phe428, His429. | -8.69 ± 0.18 | ||||

| Baicalin 64982  |

DY: G4-switch1 | Ser41, Gly60, Ser61, Ala177, Asp180, Lys206, Thr214. | -9.67 ± 0.17 | |||

| Cl: W-box | Glu33, Lys112, Asn155, Arg157, The158, Met264, Gln265, Thr306 | -9.33 ± 0.49 | ||||

| GX: Gas6-Lg1/Lg2 | Met644, Thr645, Asp654, Leu655, Ala667. | -7.96 ± 0.18 | ||||

| E: DII/DI | Arg2, Glu44, Ile46, Asp98. | -7.96 ± 0.22 | ||||

| Tricin-7-diglucuronoside 131752191  |

Cl: W-box | Lys112, Arg157, Ser200, Phe201, Met264, Gln265, Ile266, Glu268, Thr306, Gly314. | -9.45 ± 0.17 | |||

| E: DII (A/B) | Leu65, Asp203, Lys204, Ala205, Val252, His261, Glu269. | -8.29 ± 0.21 | ||||

| DY: P-loop | Gln33, Arg67, Arg107, Gln117, Asn126, Asp130, Leu131, Lys166. | -7.88 ± 0.14 | ||||

| GX: Gas6-Lg1/Axl-Ig2 | Gln78, Ser302, Gly303, Arg308, Leu309, Gln341, Ile426, Phe428, His429. | -8.05 ± 0.20 | ||||

| Scutellarin 185617

|

Cl: W-box | Trp111, Lys112, Trp113, Arg157, Thr158, Met264, Gln265, Thr306. | -9.28 ± 0.39 | |||

| DY: G4-switch1 | Ser61, Asp180, Leu181, Lys206, Thr214. | -8.31 ± 0.16 | ||||

| E: DII (A/B) | Asp203, Lys204, Ala205, Thr262, Leu264, Thr265, Glu269. | -8.13 ± 0.32 | ||||

| GX: Gas6-Lg1/Lg2 | Glu331, Asn438, Arg476, Gly477, Asp654, Glu657, Ala667. | -7.80 ± 0.17 | ||||

| Apigenin-7-glucoronide 5319484

|

Cl: W-box | Lys112, Thr158, Gln265, Thr306 | -9.17 ± 0.27 | |||

| DY: G4-switch1 | Ser41, Ala42, Gly43, Lys44, Ser45, Ser46, Gly60, Val64, Thr65, Gln239. | -8.70 ± 0.16 | ||||

| E: DII (A/B) | Asp203, Lys204, Leu264, Thr262, Glu269. | -8.22 ± 0.17 | ||||

| GX: Gas6-Lg1/Lg2 | Phe328, Asn438, Arg476, Gly477, Asp654, Glu657, Ala667, His668. |

-7.82 ± 0.17 | ||||

| Luteolin-7-glucuronide 5280601  |

Cl: W-box | Glu33, Ser70, The109, Lys112, Ile153 | -9.10 ± 0.26 | |||

| DY: G4-switch1 | Ser41, Ala42, Gly43, Lys44, Ser46, Arg59, Gly60, Val64, Thr65, Lys206, Leu207, Asn236. | -8.52 ± 0.18 | ||||

| E: DII (A/B) | Lys204, Ala205, Thr265, Ala267, Glu269 | -8.41 ± 0.15 | ||||

| GX: Gas6-Lg2 | Gly477, Arg514, Asp654, Ala667. | -8.25 ± 0.21 | ||||

| Tricin-glucuronide 101939793

|

Cl: W-box | Lys112, Arg157, Ser200, Phe201, Met264, Gln265, Ile266, Glu268, Thr306, Gly314. | -9.45 ± 0.17 | |||

| GX: Gas6-Lg1/Lg2 | Gln78, Ser302, Gly303, Arg308, Leu309, Gln341, Ile426, Phe428, His429. | -8.05 ± 0.20 | ||||

| E: DII (A/B) | Leu65, Asp203, Lys204, Ala205, Val252, His261, Glu269, Trp206. | -8.29 ± 0.20 | ||||

| DY: P-loop | Gln117, Asn126, Asp130, Leu131, Gln33, Arg67, Arg107, Lys166. | -7.88 ± 0.14 | ||||

| Dihydrobaicalein-glucuronide 14135324  |

Cl: W-box | Ser28, Ser70, Thr109, Gln152, Ile153. | -8.90 ± 0.27 | |||

| DY: P-loop | Gln17, Asn26, Asn121. | -8.41 ± 0.20 | ||||

| GX: Gas6-Lg2 | Gln78, Arg308. | -7.99 ± 0.20 | ||||

| E: DI/DII | Gly102, Asn103, His149, Gly152, Asn153, Asp154, Thr155. | -7.72 ± 0.34 | ||||

| Isocarthamidin-glucuronide 101274424  |

DY: switch2-P | Lys142, Glu153, Lys188. | -8.87 ± 0.26 | |||

| Cl: W-box | Trp113, Arg157, Met264, Gln265, Glu268, Thr30. | -8.78 ± 0.35 | ||||

| GX: Gas6-Lg1/Lg2 | Arg476, Gly477, Ser478, Arg514, Thr645. | -8.46 ± 0.18 | ||||

| E: DI/DII | Asn103, Val151, Asp154, Thr155, His244, Lys246. | -7.97 ± 0.24 | ||||

| Chrysoeriol-7-glucuronide 14630700  |

DY: G4-switch1 | Ser41, Val64, Thr65, Ser179, Asp180, Lys206, Thr214, Asp215. | -8.85 ± 0.43 | |||

| Cl: W-box | Met32, Asn155, Gln265, Thr306, Glu301. | -8.85 ± 0.27 | ||||

| E: DII (A/B) | Lys204, Trp206, Thr262, Leu264, Thr265, Glu269. | -8.37 ± 0.16 | ||||

| GX: Gas6-Lg1/Lg2 | Lys290, Arg467, Ser663, Asp664. | -7.83 ± 0.16 | ||||

| Luteolin-7-glucoside 5280637

|

Cl: W-box | Ser70, Thr109, Lys112, Ile153. | -8.54 ± 0.26 | |||

| GX: Gas6-Lg2 | Ser478, Arg514, Cys643, Asp654, His668. | -8.18 ± 0.19 | ||||

| DY: G4-switch1 | Gly60, Ala177, Lys206, Leu209, Asp211, Asp236. | -8.00 ± 0.24 | ||||

| E: DII (A/B) | Lys204, Ala205, Thr262, Thr265. | -7.98 ± 0.17 | ||||

| Wogonoside 3084961  |

Cl: W-box | Arg157, Thr158, Ala160, Gln162, Phe201, Gln203, Glu268. | -8.51 ± 0.20 | |||

| E: DII (A/B) | Trp206, Gln256, Gly258, Leu264, Thr265, Glu269. | -7.94 ± 0.24 | ||||

| DY: G4-switch1 | Arg67, His85, Arg107, Asn121. | -7.69 ± 0.19 | ||||

| GX: Gas6-Lg1/Lg2 | Gln78, Leu309, Arg310, Gln341. | -7.69 ± 0.12 | ||||

| Baicalein 5281605

|

DY: switch2-P | Thr141, Glu153, Arg157, Asp185. | -8.26 ± 0.36 | |||

| Cl: W-box | Asn155, Arg157, Val262, Met264, Gln265, Thr306. | -8.08 ± 0.47 | ||||

| E: βOG pocket | His27, Thr48, Gly281, His282. | -7.92 ± 0.76 | ||||

| Dihydrobaicalein 9816931

|

DY: switch2-P | Thr141, Glu153, Arg157, Asp185. | -8.25 ± 0.40 | |||

| Cl: W-box | Ser70, Lys83, Trp111. | 7.97 ± 0.45 | ||||

| E: βOG pocket | Leu25, His27, Thr48, Gly281, His282. | -7.84 ± 0.80 | ||||

| Wogonin 5281703  |

E: βOG pocket | Thr48, Tyr137, Gly281, His281. | -7.66 ± 0.80 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).