2.2. Methodology for valuating the productive function of forests with water protection functions and distribution of income between the forest owner and the user of forest ecosystem services

The economic valuations of forests referred to in scientific literature are based on the permanent annual income obtained from them. Thus, the monetary value of the forest or of parts thereof is calculated as the difference between the capital used and the income generated. As far back as 1796, Burgsdorf tried to calculate the monetary value of forests in exactly the same way. Shortly before that (in 1788), the first forest valuation regulation was issued by means of the so-called Austrian cameral tax. According to it, the possible normal income from the forest and its corresponding normal stock should be calculated first. Afterwards, after deducting allowance for taxes and forest management costs, the remaining income is capitalized at 5% during the adopted rotation period and thus the normal value of the forest is calculated. In principle, the actual forest deviates from the normal one, so in proportion to this deviation, the normal value of the forest is reduced or increased, and its actual value is thus obtained [

20].

In 1849, Faustmann derived and proposed the formula for calculating the value of the land, and in 1854 – the formula for calculating the planting costs [

17].

Forest investments are usually analyzed using the Faustmann model (Faustmann 1849, Samuelson 1976). This method was mainly discussed by Conrad and Clark (1987) and Comolli (1981), and later revised by Yin and Newman (1997) [

8,

9,

40,

45].

In Bulgaria, the issue of forest valuation has also been considered. Prof. Temelko Ivanchev (1940) was the first to lay the theoretical and methodological foundations of forest valuation. For this purpose, he used German textbooks on the subject, published at the beginning of the 20th century (1912, 1919, 1921) [

20].

Angel Baev recommended that the comprehensive valuation of forest resources should be carried out by creating a forest register as part of the comprehensive valuation of all natural resources. According to him, such unified economic valuation of forest resources will provide a basis for determining the most effective forestry activities, as well as an accurate assessment of their effect [

4].

H. Sirakov suggested that when assessing the future composition of forests, the following indicators should also be applied: vitality; productivity; economy and user satisfaction. As a starting point for their application are the site conditions, with preference given to the most viable species; of them – to the most productive; to the most economical in terms of cost-effectiveness and to the most widely used timber species. Some of these indicators can also be applied to the assessment of plantations [

42].

I. Yovkov, I. Paligorov and Y. Poryazov, using the theory of contribution, developed a solution to the economic problem of optimal duration of the felling cycle in order to achieve the maximum financial contribution from the use of the clear-cutting form of forest management [

22]. I. Yovkov, I. Paligorov and I. Dobrichov (1992) undertook the task to determine the optimal stock at which the maximum financial contribution would be achieved from the use of the selective cutting form to forest management [

21].

I. Paligorov made an economic valuation of the use of different cutting technologies and techniques for the thinning of uneven-aged plantations. The factors that influence the thinning and sanitation cutting of coniferous forests were determined. The costs associated with thinning activities and the income were calculated. The economic indicators of the use of timber from thinnings were determined using the contribution theory [

38].

D. Georgieva perfected the approach for economic valuation of selectively cut forests in structural balance by using net present value in perpetuity. She proposed an approach for choosing the optimal target diameter of selectively cut forests under conditions of uncertainty by means of the marginal analysis method [

18].

In 1998, Ordinance No. 32 on the valuation of forests and lands in the forest fund was adopted in Bulgaria. Subsequently, it was repealed and the Ordinance on fixing base prices, prices for excluded areas and establishing rights of use and easements on forests and lands from the forest fund was adopted [

34], and in 2011 pursuant to Resolution No. 236 of the Council of Ministers, the Ordinance on valuation of land properties in forest territories was issued. It is currently a valid normative document which provides a mechanism for fixing regulated prices [

36].

It should be noted that all authors listed so far have succeeded in valuating forests with timber production functions. However, both the theory and practice lack an economic valuation of the other functions [

1,

44]. On the other hand, the methods and valuations turn to the ecological functions of forests [

6,

7,

10,

11,

37].

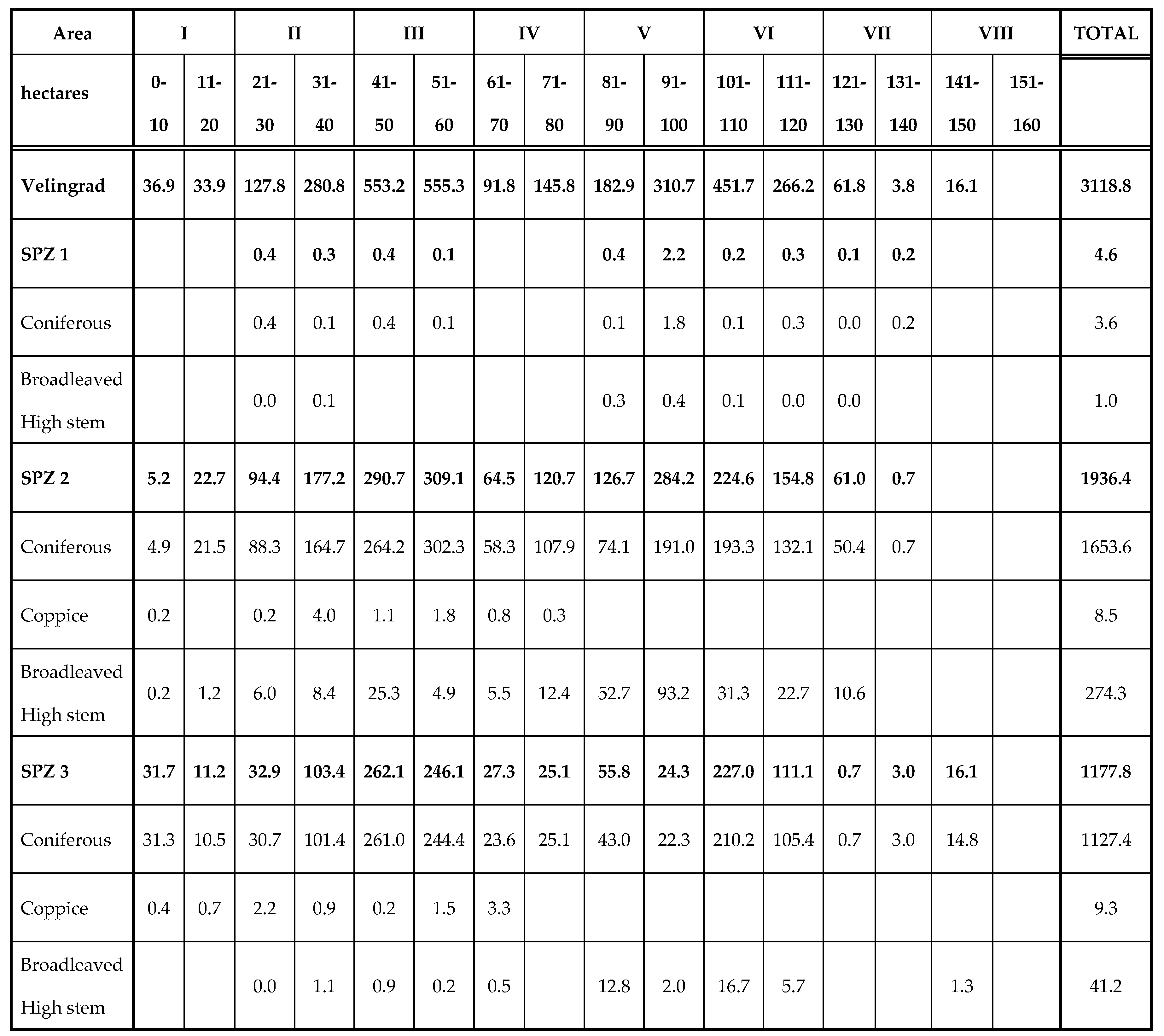

Despite having a significant contribution to the management of forest ecosystems, the silvicultural ecological approach leaves a certain gap in the theory and practice of forest management. The water protection functions of forests, their recreational and tourist functions, their field protective functions, etc., remain undervalued. Тhe main commodity produced by forests with such functions is not wood, but water, tourist products and services, agricultural products, etc. In the present study, it is therefore justified to make a valuation of the water protection function. Its economic aspect is missing both in the economic theory of forestry and in the well-established practical market approach to forest management. The reason for this is that forests in general, including water protection forests, are still viewed as a fund and not as capital. If forests are viewed as capital, then they constitute an investment and should be valued as such. This is precisely what is missing in existing research.

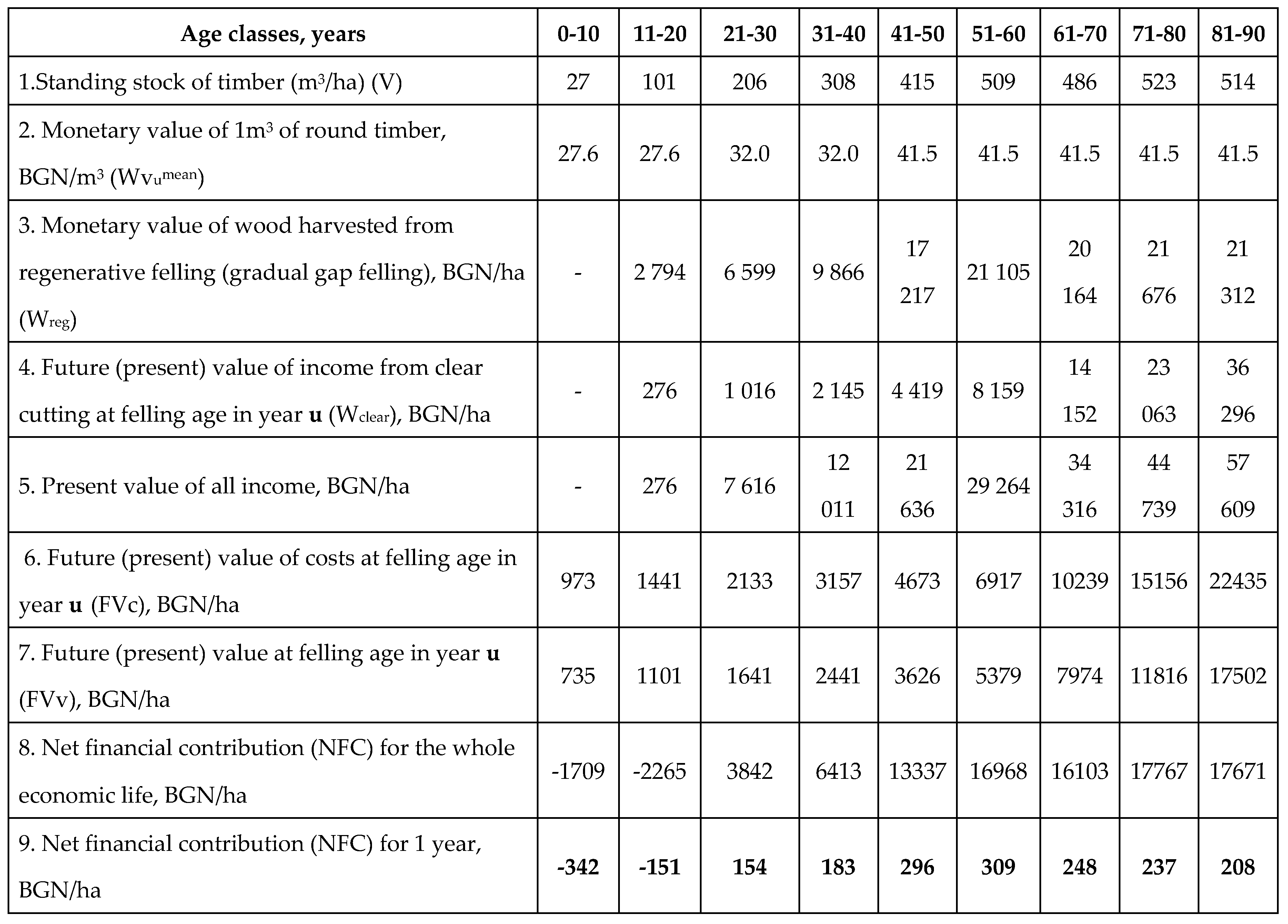

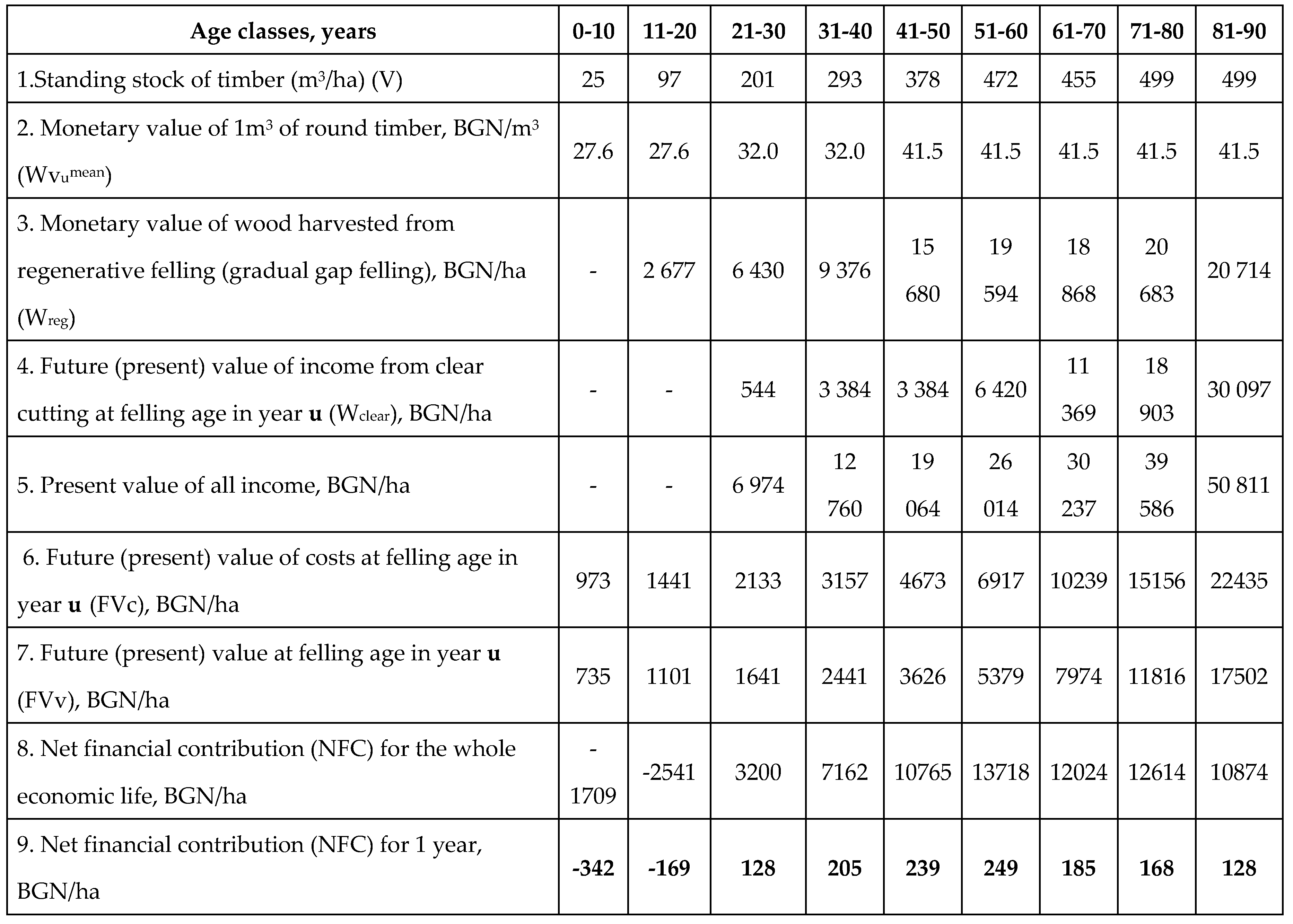

The silvicultural systems that are currently used in Bulgaria are mainly even-aged forest management systems (clear-cutting). These systems employ regenerative felling methods, which result in even-aged, and uniform in structure and density stands over large areas. In this context, it is advisable to make an economic valuation of the investments in water protection forests precisely in the case of the clear-cutting form of forest management. It should be emphasized here that, depending on the type of regenration felling, it can be clear-cutting, shelterwood and selective logging [

5,

43]. The clear-cutting form of forest management is limited by law, and shelterwood is most commonly used in practice. Shelterwood involves gradual felling. The types of shelterwood fellings are short-term-gradual, gradual-gap, group-gradual and uneven-gradual [

35]. Short-term gradual fellings have a regeneration period of up to one age class and is suitable for even-aged plantations [

29]. For this reason, the methodology for economic valuation of the water protection function of forest territories is limited to this type of felling, and its silvicultural technical characteristics have been briefly presented.

The size of the felling area in short-term gradual felling is up to 2 ha, and the period of regeneration is a minimum of 15 years and a maximum of 20 years. Felling is carried out evenly over the felling area in 3 or 4 phases (preparatory, seeding, secondary and final). Each phase is characterized by a different felling intensity and canopy density. In the preparatory phase, canopy density is reduced to 0.7 - 0.8, and the felling intensity is up to 25%. This phase can be skipped if regular thinning has been carried out. The seeding phase is carried out no earlier than 5 years after the preparatory phase, where the felling intensity is up to 30%, and the canopy density is reduced to 0.5 - 0.6. During the secondary phase, the felling intensity is up to 30%, and the canopy density is reduced to 0.3 - 0.4. It is carried out no sooner than 5 years after the seeding phase. Finally, when the canopy density of tree stands in the felling area is not greater than 0.4 and more than 80% of the area is covered with undergrowth, the final felling phase is carried out [

29].

In accordance with the silvicultural and technical characteristics of the short-term gradual felling presented above, the methodology for valuating the water protection functions of even-aged forests is based on the following algorithm: determination of the stock of wood per root of uneven-aged plantations (Vu); determination of the present monetary value of wood from regenerative felling of uneven-aged plantations (Wreg); determination of the present monetary value of wood from thinnings (Wclear); determination of the costs of creating woodland and their capitalization at plantation age (c); determination of fixed costs and their capitalization for the entire economic life (V); determination of the net financial contribution of uneven-aged plantations (NFCu); determination of the forest rent from and the distribution of income between the forest owner and the user of the forest ecosystem services.

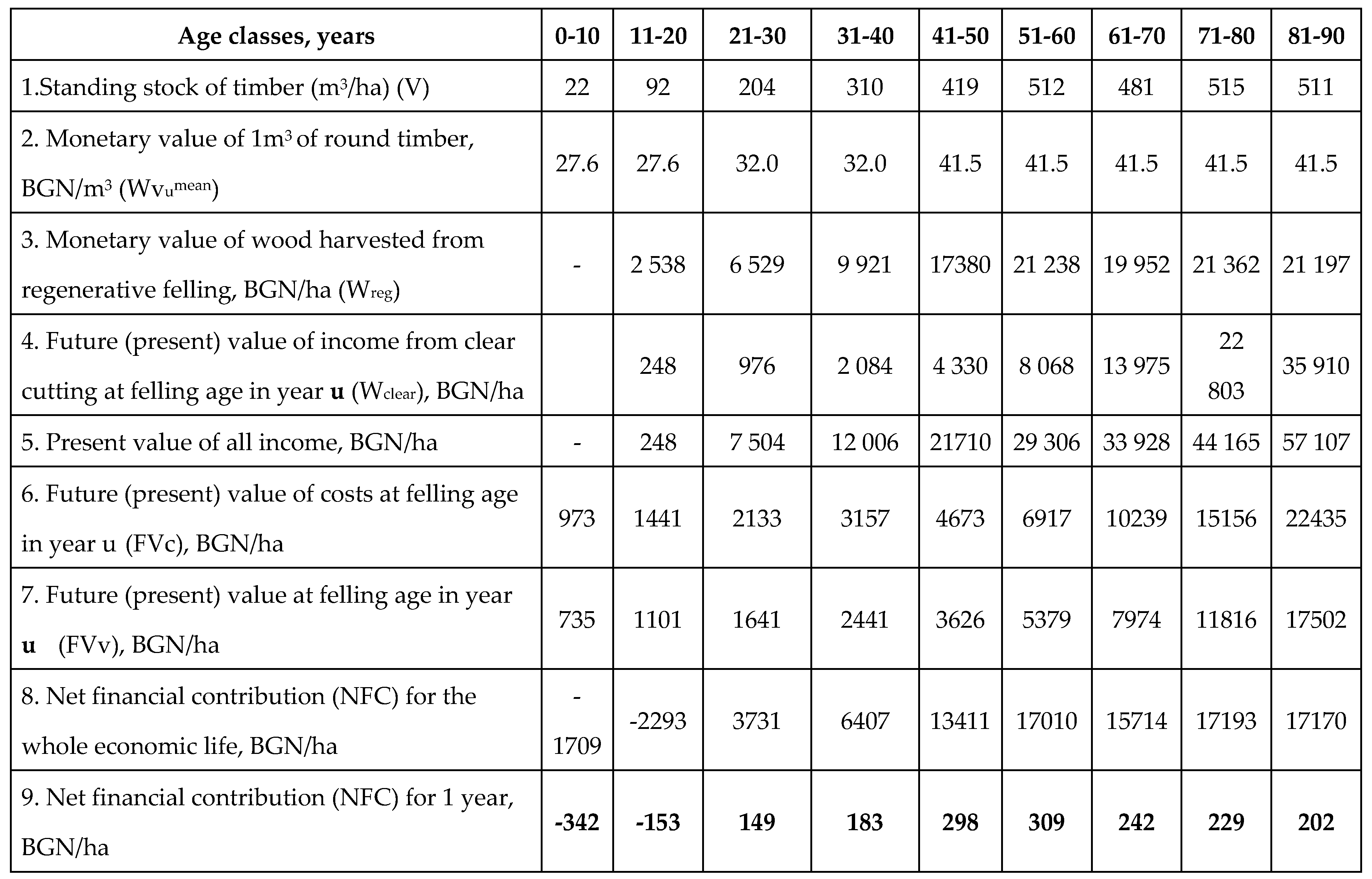

Determining the stock of wood per root (V)

The stock of wood is the volume of wood in the above-ground part of trees. It depends on the natural conditions of growth and development of the plantation and on the economic activity carried out in them. The stock (V) of the growing stand is calculated using several methods: the mean sample stem method, mensuration methods by girth and class, and mensuration table methods.

Determining the monetary value of wood from short-term gradual felling

Based on the silvicultural technical characteristics of short-term gradual felling described above, it is clear that income from regenerative felling (W

u) does not come all at once, but at different times during the regeneration period. In this case, a certain year is chosen, which is taken as the u felling age. This year or age is the year in which the final phase of regenerative felling occurs. It is clear that a portion of the income from regenerative felling (W

u) is received in the u year of final felling. Another part of this income (W

u-m) from preparatory felling is received before reaching the u age, for example in year m, and therefore this income is extended for the period from its receipt to year u, equal to (u - m) years [

26].

Capitalized monetary value of wood from the preparatory, seeding and secondary phases of felling:

where W

u-m is the capitalized value of wood from the preparatory, seeding and secondary phases of felling;

Qi – volume of wood from the ith category, m3;

Pi– the warehouse price of 1m3 of wood from the ith category BGN/m3, where m is the year of felling;

r – the rate of return on alternative investments for the period, percentage expressed as a fraction of 1.0.

The current methodology has adopted the use of the so-called forest interest rate r = 4% [

30]

Monetary value of wood from the final phase of felling (W

u):

Finally, the monetary value of wood from regenerative felling (W

reg) is determined using the formula (3):

Determining the present monetary value of wood from thinning (Wclear)

When calculating income from thinning, first of all, it should be examined and determined whether such income can be actually generated or not. Often times such revenues cannot be generated either due to the limited market conditions for the sale of wood harvested from thinning, or due to a lack of convenient and cost-effective freight transport. It is clear that given these unfavorable conditions, this intermittent income should be left out of the calculations.

There are also cases when, due to inefficient management, thinnings are not carried out, but they are perfectly possible, and then the income generated from them will have to be determined and included in the calculations. Data on the amount, receipt, etc. of the income from thinnings can be obtained from other neighboring state forestry offices working under approximately the same conditions, which carry out regular thinning activities and receive a corresponding income generated from them.

It goes without saying that, if thinning activities are carried out properly, in addition to being of great silvicultural importance, they are also sources of significant income for state forestry offices.

The monetary value of wood from thinning activities in year a (W

a) is calculated using the following formula:

In order to add the income from thinning to the income from regenerative felling, the former must be expressed in a comparable form, i.e. should receive a present value at the end of each plantation age.

The cash income from intermittent felling must be capitalized in year u when the income from the regenerative felling is received.

The total revenue from all thinning activities (W

clear) is calculated as follows:

where W

a, W

b,... and W

q are the monetary values of wood from thinning, BGN;

а, b... and q are the years in which thinning activities are carried out in the plantation.

Determining the costs of creating woodland and their future value at plantation age (FVc)

The costs of establishing a forest plantation include the costs incurred until the establishment of the plantation: clearing the felling area, soil preparation, delivery of planting material, tree planting, fertilization, replacement, cultivation, fencing. The costs of establishing the plantation depend on the tree species, its origin and the difficulty of the terrain during planting. This investment is one-off and is capitalized for the entire period of the adopted felling cycle.

The costs incurred initially to establish the forest plantation and capitalized at plantation age are calculated using the formula (6):

where FV

c is the future value of the costs of establishing the forest plantation at plantation age, BGN;

с – the costs of establishing the forest plantation, BGN.

Determining the fixed costs and their future value at plantation age (FVv)

During the life of the plantation, usually every year until its regenerative felling, fixed costs amounting to BGN v are incurred [

23]. These costs have the characteristics of an annuity, whose future value is calculated using the formula (7) [

27]:

where FV

v is the present value of fixed costs, BGN.

v – average annual fixed costs, BGN;

Determining the net financial contribution at different plantation ages (NFCu)

The net financial contribution (NFCu) is calculated as the difference between the total updated income generated from thinning activities (Wclear) and regenerative felling (Wreg) and the total present costs of establishing the forest plantation (Fvc) and the average annual administrative costs (FVv).

Based on the above formulas for calculating the income and costs, the net financial contribution at the end of year u will equal [

23,

28]:

The above formula (8) gives us the net financial contribution of the plantation over its lifetime of u years. With its help, the production possibility frontier can be defined. At the same time, the economic choice is limited to alternative options. The criterion for this choice is the value of use (max NFCu) of forest ecosystems for different target functions or a combination of several functions.

Determining the forest rent and the distribution of the income between the forest owner and the user of forest ecosystem services

The resulting net financial contribution (NFC) has to serve the interests of the owners of the three types of capital: forestry, labor and entrepreneurial capital, i.e. the individual owners of the factors of production must obtain an economic benefit from their property . The factor of production – timber fund (standing timber) – has the characteristics of a natural resource. The economic benefit from any natural resource is the rent. Forest rent is an income generated from the property rights over forest resources. This income is acquired by the owners by means of two mechanisms. The first involves leasing the right of use, where the so-called "natural fruits" are acquired by the "user of the forest ecosystem services", and the "civil fruits" by the "forest owners". Historically, the institutional environment has been created in such a way as to support forest owners, protect their property rights (the forest) and improve the forest for future generations. A resource to help carry out this function is the rent (R). It is the economic benefit of ownership of forest territories. The user of the forest ecosystem services is the bearer of the property rights on the capital advanced for the forest business. The user is the entity that has a monopoly on the management of forest territories. The economic benefit from their property is the profit. The mechanism that reflects the nature of the transactions between the two entities and by means of which they acquire the rights to the property is expressed by Schenrock's formula [

19,

25,

30,

41]:

where: R is the forest rent (income from the right of use of forest property) for forest owners, BGN/m

3, BGN/kg, etc.;

P – the market price per forest product, BGN/m3, BGN/kg, etc.;

g – profitability based on production costs per user of forest ecosystem services, as a fraction of 1.0;

e – costs for harvesting forest products, BGN/m3, BGN/kg, etc.;

d – costs for transporting forest products EXW to the nearest location where the user of forest ecosystem services can receive them, BGN/m3, BGN/kg, etc.

The transactions under this mechanism are of such a nature that the two entities, guided by their interests and protecting them in the negotiation process, receive a fair value of the income from the invested capital. The meaning of fair here extends to the degree in which the institutions set up to regulate the market equally protect both types of property – that of forest owners and that of the user of forest ecosystem services. Under this mechanism, if the forest ecosystem has a wood production function, the rent (R) as an income for the forest owner will be generated based on the market price reached by wood resources.

According to this mechanism, the profit generated by a user of forest ecosystem services is the result of the amount of wood resources used and the rate of profit (g) of the market price per unit of wood resource. This norm reflects the following exchange relation: the price that the respective buyer has agreed to pay and the seller has agreed to accept under the circumstances existing at the time of each transaction. Therefore, it is fair insofar as the institutions provide conditions for the protection of the property rights of a user of forest ecosystem services. Finally, the operating costs (e+d) incurred by a user of forest ecosystem services will obviously depend on the price of the factors of production. These factors are territorially differentiated and obviously have an impact on the final income – rent and profit.

Now, we can ask the question: What should the owner of forests with water protection functions receive if the nature of the transactions is of the type reflected in formula (9) in the case of an even-aged forest (under a clear cutting form of forest management)? According to economic logic, this would be the opportunity cost of the loss of rental income from unrealized gains from timber use rights. These unrealized gains can be:

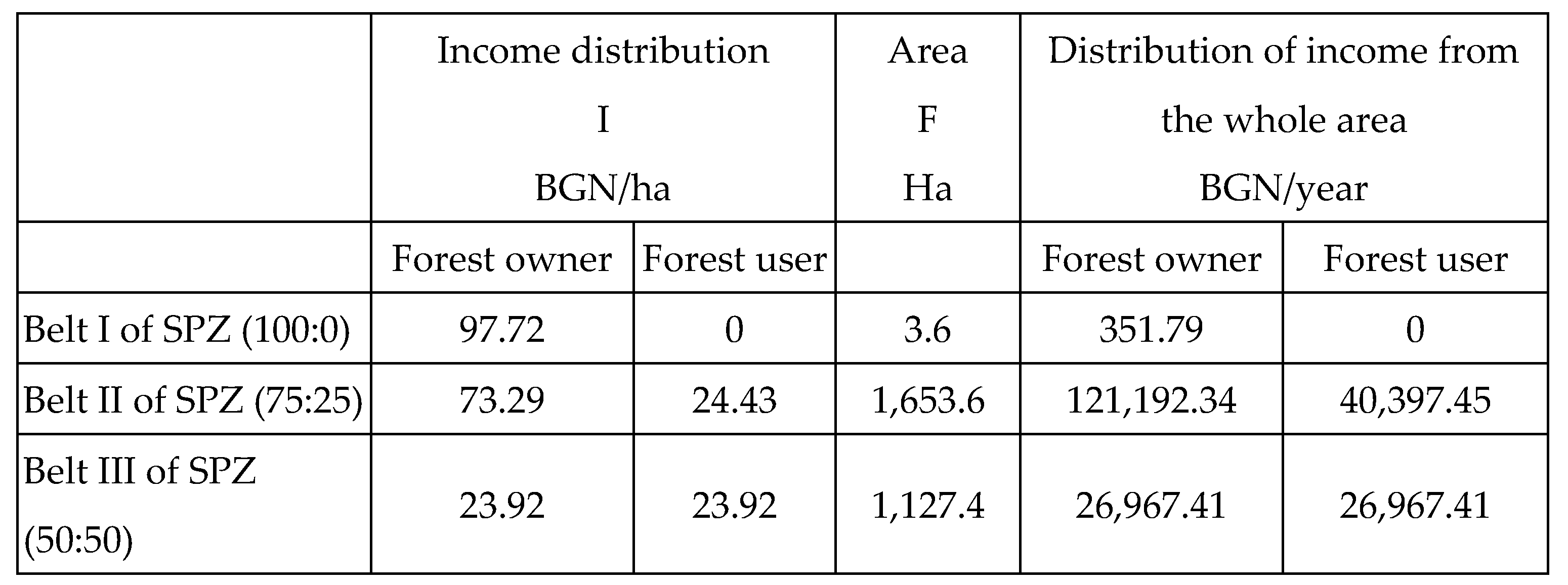

Full – when the forests are used only for their water protection function and the income from wood is zero. Here the loss from unrealized gains from forest use rights is 100% and should be 100% covered along the water consumption or wood production pricing chain;

Partially limited – when forests are used equally for both wood production and water protection. The fair allocation here requires that 50% of the income be at the expense of wood production, and the other 50% - at the expense of the water protection and water regulation function;

Limited – when the wood production function is given priority over the water protection function or vice versa. Here, it is reasonable that 75% of the income should be covered by the wood production function and 25% - by the water protection and regulation function or vice versa.

The second question that arises is what income the forest owner loses from unrealized gains from timber use rights over even-aged forests?

When a forest owner grants the timber use rights to a user of forest ecosystem services, their net financial contribution (NFC) will obviously acquire the characteristics of a rent. In order for it to be determined, the economic balance between the forest owner and the user of forest ecosystem services must also take into account the current costs of the user of forest ecosystem services. In this case, formula (9) calculating this balance takes the form of an annual balance between the two entities, i.e.:

where R

year is the annual forest rent, BGN/hа/year;

NFC

year – mean annual contribution per 1 year, BGN/ha/year. It is calculated using formula (11):

Qyear – the average volume of wood harvested per 1 year from thinning and regenerative felling under a clear cutting form of forest management, m3/ha/year.

Historically, in Bulgaria, а profit margin of g=20"\%" has been found to ensure a relatively good distribution of income between entities [

19,

30]. This balance again places the two entities on an equal footing, each of them having the right to receive income from the property they own. This income must be used by them to satisfy their needs, as well as to improve this property for future generations.