Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

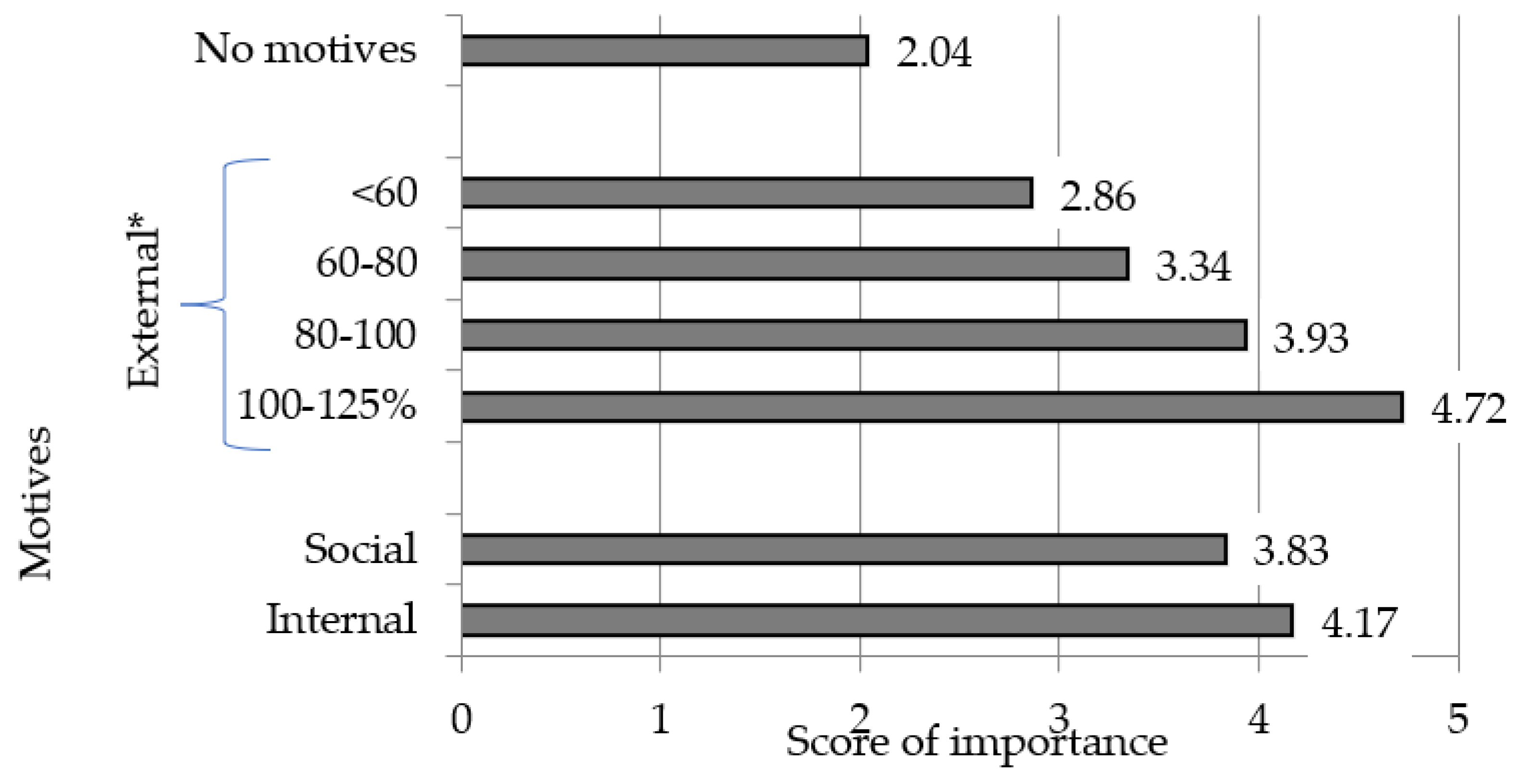

- Internal motives: these include the desire to improve environmental quality, enhance community well-being, preserve inheritance values, foster an emotional connection to the forest, engage in forest activities, and express or realise personal ideas in forest management.

- Social motives: these encompass factors such as reputation, image, moral satisfaction, and the desire to belong to or distinguish oneself from a group.

- External motives: primarily financial compensation.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Civic, K. Voluntary protection of forests in Finland, Sweden and Norway. European Land Conservation Network. 2018. Available online: https://elcn.eu/index.php/news/voluntary-protection-forests-finland-sweden-and-norway.

- Frank, G.; Muller, F. Voluntary approaches in the protection of forests in Austria. Environ. Sci. Policy. 2006, 6, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosenius, A. K. Forest Owner Attitudes and Preferences for Voluntary Temporary Forest Conservation. Small-scale For. 2024, 23, 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, V.; Vistad, O. I.; Skjeggedal, T. Forest owners’ perspectives on forest protection in Norway. Scand. J. Forest Res. 2022, 37, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranovskis, G.; Nikodemus, O.; Brūmelis, G.; Elferts, D. Biodiversity conservation in private forests: Factors driving landowners attitude. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 266, 109441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela, T.; Karppinen, H. Forest Owners Willingness to Implement Measures to Safeguard Biodiversity: Values, Attitudes. Ecological Worldview and Forest Ownership Objectives. Small-scale For. 2021, 20, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juutinen, A.; Kurttila, M.; Pohjanmies, T.; Tolvanen, A.; Kuhlmey, K.; Skudnik, M.; Triplat, M.; Westin, K.; Makipaa, R. Forest owner's preferences for contract-based management to enhance environmental values versus timber production. Forest Policy Econ. 2021, 132, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danley, B.; Bjärstig, T.; Sandström, C. At the limit of volunteerism? Swedish family forest owners and two policy strategies to increase forest biodiversity. Land Use. 2021, 105, 105–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abildtrup, J.; Stenger, A.; de Morogues, F.; Polome, P.; Blondet, M.; Michel, C. Biodiversity Protection in Private Forests: PES Schemes, Institutions and Prosocial Behavior. Forests. 2021, 12, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polome, P. Private forest owners' motivation for adopting biodiversity-related protection programs. J. Environ. Manage. 2016, 183, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitani, Y.; Lindhjem, H. Forest Owners’ Participation in Voluntary Biodiversity Conservation: What Does it Take to Forgo Forestry for Eternity? Land Econ. 2015, 91, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górriz, E.; Mäntymaa, E.; Petucco, C.; Schubert, F.; Vedel, S. E.; Mantau, U.; Prokofieva, I. Explaining participation of private forest owners in economic incentives. Case studies in Europe. Scandinavian Forest Economics. Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Scandinavian Society of Forest Economics. 2014, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Götmark, F. Conflicts in conservation: Woodland key habitats, authorities and private forest owners in Sweden. Scand. J. Forest Res. 2009, 24, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- METSO. Voluntary forest protection popular among forest owners – record numbers of environmental aid agreements and nature management measures under METSO Programme. METSO news, 2024-02-14. Available online: https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/-/1410903/voluntary-forest-protection-popular-among-forest-owners-record-numbers-of-environmental-aid-agreements-and-nature-management-measures-under-metso-programme.

- METSO. Almost 90 percent of the protection target set in the METSO Programme has already been reached – more funding is needed for environmental subsidies and nature management. METSO news, 2022-07-17. Available online: https://metsonpolku.fi/en/-/almost-90-per-cent-of-protection-target-set-in-metso-programme-already-reached-more-funding-needed-for-environmental-subsidies-and-nature-management.

- Syrjänen, K.; Apala, K.; Anttila, S.; and, S. Kuusela, S. Success and challenges of voluntary forest conservation in Finland. 5th European Congress of Conservation Biology. 2018. [CrossRef]

- METSO – The Forest Biodiversity Programme for Southern Finland. 19-06-2023. Available online: https://www.ymparisto.fi/en/nature-waters-and-seas/natural-diversity/conservation-and-research-programmes/metso-forest-biodiversity-programme-southern-finland.

- Borg, R.; Paloniemi, R. Deliberation in cooperative networks for forest conservation. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2012, 9, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntymaa, E.; Juutinen, A.; Mönkkönen, M.; Svento, R. . 2009. Participation and compensation claims in voluntary forest conservation: A case of privately owned forests in Finland. Forest Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- METSO. Government resolution on the Forest Biodiversity Programme for Southern Finland 2008–2016 (METSO-Programme). 27 March 2008.

- Hiedanpää, J. The edges of conflict and consensus: a case for creativity in regional forest policy in Southwest Finland. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 55, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, P.; Ovaskainen, V.; Koskela, T. Economic and social implications of incentive-based policy mechanisms in biodiversity conservation. Working Papers of Finnish Forest Research Institute. 2004. Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://jukuri.luke.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/535918/mwp001.pdf?sequence=1.

- Thomasson, T. Payments for Ecosystem Services: What role for a green economy? Swedish Forest Agency. 2011. Available online: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/timber/meetings/20110704/2-KOMET_Sweden_Tove_Thomasson_Geneva_5_July_2011.pdf.

- Kometprogrammet 2010-2014. Naturvardsverket raport. 2014, 6621. Stockholm, 2014, 57 p. Available online: https://naturvardsverket.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1389402/FULLTEXT01.

- Widman, U. Exploring the Role of Public-Private Partnership in Forest Protection. Sustainability. 2016, 8(5), 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaro, I. Voluntary protection of forests in Norway. CEPF Blank page. 2022. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=6405969259418430&set=a.207454412603310.

- Dalkey, N. The Delphi method: An experimental study of group opinion. Santa Monica, USA, 1969, 90 p. Available online: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_memoranda/2005/RM5888.

- Dalkey, N. An experimental study of group opinion. Futures. 1969, 1, 408–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colton, D.; Covert, R. W. Designing and constructing instruments for social research and evaluation. Published by Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2007, 394 p. ttps://www.wiley.com/en-in/Designing+and+Constructing+Instruments+for+Social+Research+and+Evaluation-p-9780787987848#download-product-flyer.

- Aiken, L. Attitudes and related psychosocial constructs: Theories, assessments, and research. Sage Publications, USA. 2002, 328 p. https://sk.sagepub.com/book/mono/attitudes-and-related-psychosocial-constructs/toc.

- Brukas, V.; Stanislovaitis, A.; Kavaliauskas, M.; Gaižutis., A. Protecting or destructing? Local perceptions of environmental consideration in Lithuanian forestry. Land use policy. 2018, 79, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavorienė,V. ES svarbos buveinės. Tikėjosi grąžos, bet gavo šnipštą. 2022. https://www.forest.lt/Naujienos/es-svarbos-buveines-tikejosi-grazos-bet-gavo-snipsta/.

- Kaip valstybei pavyks susitarti su savininkais dėl ST plėtros? Mano ūkis, 2021-02-25. https://www.manoukis.lt/naujienos/aplinka-miskai/kaip-valstybei-pavyks-susitarti-su-savininkais-del-saugomu-teritoriju-pletros.

| Article | Country |

|---|---|

| Kosenius, (2024),[3] | Finland |

| Gundersen et al.,(2022),[4] | Norway |

| Baranovskis et al.,(2022),[5] | Latvia |

| Koskela and Karppinen,(2021),[6] | Finland |

| Juutinen et al.,(2021),[7] | Finland |

| Danley et al.,(2021),[8] | Sweden |

| Abildtrup et al.,(2021),[9] | France |

| Palome, (2016),[10] | France |

| Mitani and Lindjeni,(2015),[11] | Norway |

| Goritz et al.,(2014),[12] | Finland, Denmark, France, Germany |

| Gotmark, ( 2009), [13] | Sweden |

| Thematic parts of questionnaire | Cronbach's Alpha |

|---|---|

| Priorities | 0.691 |

| Motives | 0.695 |

| Effectiveness | 0.693 |

| Instrument | Score of Likert scale* Number of experts/% |

Mean score | St. dev. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Land acquisition | 3/10.3 | 5/17.2 | 7/24.1 | 7/24.1 | 7/24.1 | 3.34 | 1.317 |

| Protection agreements | 1/3.4 | 2/6.9 | 3/10.3 | 8/27.6 | 15/51.7 | 4.17 | 1.104 |

| Information | 1/3.4 | 2/6.9 | 2/6.9 | 6/20.7 | 18/62.1 | 4.31 | 1.105 |

| Factors | Score of Likert scale* Number of experts/% |

Mean score | St. deviation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Property rights and freedom of decision-making | - | - | 6/20.7 | 11/37.9 | 12/41.4 | 4.21 | 0.774 |

| Amount of compensation | - | - | 1/3.4 | 7/24.1 | 21/72.4 | 4.69 | 0.541 |

| Clear definition of compensation | - | - | 1/3.4 | 12/41.4 | 16/55.2 | 4.52 | 0.574 |

| Cancelation policy for obligations | 1/3.4 | - | 6/20.7 | 10/34.5 | 12/41.4 | 4.10 | 0.976 |

| Compensation form | - | - | 4/13.8 | 12/41.4 | 13/44.8 | 4.31 | 0.712 |

| Duration of the Protection agreement (contract) | - | 2/6.9 | 2/6.9 | 17/58.6 | 8/27.6 | 4.07 | 0.799 |

| Restrictions on forest management (use) | - | - | 3/10.3 | 8/27.6 | 18/62.1 | 4.52 | 0.688 |

| Continuity of the Protection agreement (contract) | - | 1/3.4 | 8/27.6 | 11/37.9 | 9/31.0 | 3.97 | 0.865 |

| Distribution of compensation within the payment period specified in the Protection agreement (contract) | - | 1/3.4 | 7/24.1 | 14/48.3 | 7/24.1 | 3.93 | 0.799 |

| Initiator of the Protection agreements project (contract) | 2/6.9 | 3/10.3 | 10/34.5 | 12/41.4 | 2/6.9 | 3.31 | 1.004 |

| Achieving biodiversity and ecosystem protection goals | - | 4/13.8 | 11/37.9 | 9/31.0 | 5/17.2 | 3.52 | 0.949 |

| Impact on the local labor market | 3/10.3 | 6/20.7 | 10/34.5 | 6/20.7 | 4/13.8 | 3.07 | 1.193 |

| The significance of the Protection agreement (contract) at the national level | 1/3.4 | 8/27.6 | 9/31.0 | 7/24.1 | 3/10.3 | 3.11 | 1.066 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).