1. Introduction

Leptospirosis is a bacterial disease caused by multiple species of the Leptospira genus (Levett et al., 2001). The diseases affects various animal species (Boqvist et al., 2002), including pigs, and can be transmitted to humans through contact with water or soil contaminated with the urine of infected animals (Faine et al., 1999). The disease is caused by different serovars of the spirochete bacteria that are morphologically and physiologically similar; however, they react to different antigens, all of which belong to the genus Leptospira spp. that is distributed almost worldwide (Pappas et al. 2008; Bharti, 2003). Reservoir animals harbor leptospiras in their kidneys for a long time, often without clinical signs, shedding them in the environment through urinary elimination and playing an important role as a source of infection (Raghavan et al. 2011; Ward et al. 2004). Animals can present variable clinical signs such as fever, renal and hepatic failure, and reproductive disorders (Ellis et al. 1999; Cilia et al. 2020). As concerning the association of serovar-reservoir, many epidemiological studies reported specific animal species might act as the reservoir for particular Leptospira serovars (Medeiros et al. 2020). For example, swine act as a maintenance host for leptospires and are a possible source of human and domestic animal infections (Ellis et al. 1999).

Leptospirosis infections in pigs can result in various clinical signs, including fever, jaundice, loss of appetite, lethargy, and abortion in pregnant females (Ellis, 2015). Additionally, maintenance hosts generally do not develop clinic forms of the disease, but act as natural pathogen sources, highly influencing Leptospira spp. epidemiology (Cerri et al. 2003; Soto et al., 2007; Ellis, 2015). The presence of the disease results in economic losses in pig farming (Boqvist et al., 2002), as reproductive failures can occur, such as fetal death, abortion in the early third of gestation, infertility, and the birth of weak piglets (Ngugi et. al, 2019). Historically, pigs act as a maintenance host for the serovars Bratislava, Pomona and Tarassovi, while among the incidental serovars, the most important in pigs are those belonging to the Australis, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Canicola and Grippotyphosa serogroups (Ellis et al. 1999; Strutzberg-Minder et al. 2018; Strutzberg-Minder et al. 2022).

Diseases with zoonotic potential require attention and control due to the risk they pose to One Health approach. In Brazil, leptospirosis is a disease that must be notified monthly to the Official Veterinary Service as established by normative instruction nº 50 09/24/2013, of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Food Supply (MAPA) (MAPA, 2013). The MAPA has programs and policies to encourage the production of subsistence pigs on small rural properties, including funding and technical training programs. However, animal health promotion and disease prevention, such as leptospirosis, must be considered priorities to ensure food safety and public health. The microscopic agglutination test (MAT) is a widely used method for the serological diagnosis of leptospirosis, particularly for epidemiological research, as it allows for the simultaneous detection of various serovars that belong to different serogroups (Faine et al., 1999; Ellis, 2015). The test is based on the principle of antigen-antibody reaction and can identify both IgM and IgG antibody classes. (Guedes et al., 2021).

Individuals in different occupations that involve direct contact with animals, such as rural workers, animal handlers, veterinarians, and slaughterhouse workers, may contract the disease or become seropositive for some Leptospira spp. serovars (Dung et al., 2022; Viroj et al. 2021; Calderón et al., 2014). The disease is primarily transmitted to humans through the urine, blood, saliva, and semen of infected animals, particularly rodents and dogs (Medeiros et al. 2020; Guerra, 2013). Additionally, the lack of effective sanitary measures and promiscuity among animal species have been shown to facilitate the spread of the pathogen in pig farming (Barragan et al., 2017; Delbem et al., 2004). In subsistence pig farming, where animals are raised on a small scale for self-consumption or local sale, leptospirosis can be a significant concern due to inadequate hygiene and management conditions (Lacerda et al. 2008).

Leptospirosis occurs in Brazil with varying frequencies and varies according to the region studied, as reported by Delbem et al. (2004). Several serovars of Leptospira interrogans have been associated with infections in pigs from commercial farms. In a study conducted by Favero et al. in 2002 [2002], seroprevalence rates of 33.4%, 50%, and 66.6% were reported for the serovars Grippotyphosa, Autumnalis and Pomona, respectively, across 10 different Brazilian states including Bahia, Maranhão, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, Paraná, Goiás, Santa Catarina, São Paulo, Ceará, Rio Grande do Sul, Pernambuco, while Ramos et al. (2006) reported infections with the serovars Pomona, Copenhageni, Tarassovi, Hardjo, Bratislava, and Wolffi in 18 technified pig farms with reproductive disorders in Rio de Janeiro. Finally, Azevedo et al. 2008) reported a seroprevalence rate of 29% for serovar Pomona in serum samples from swine slaughtered in Paraiba state in 2008. Both studies reported a high prevalence of serovar Pomona, which was gradually replaced by Icterohaemorragiae in parallel with advances in improving procedures aimed at controlling rodents and adopting strategies to improve biosecurity as part of the management of Brazilian industrial pig farms, as reported by Petri et al. (2021).

To the best of our knowledge, there is limited data on the epidemiology of swine leptospirosis in rural subsistence pig farms in the literature. A study conducted in the state of Paraná evaluated the prevalence and risk factors associated with Leptospira infection in 344 pigs raised on 86 rural properties (Oliveira et al. 2018), where Copenhageni and Hardjo serovars were most prevalent. In summary, Leptospira infection in pigs raised in non-technified systems poses a significant problem in Brazil, especially in rural and family agriculture areas. Preventing the disease is crucial to ensure animal health and food safety. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the seroprevalence and geospatial distribution of swine leptospirosis in the state of Paraná, Brazil, considering the occurrence of this type of animal rearing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample design and study area

Sample collection was carried out for laboratory analyses and did not involve any suffering of the sampled animals. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The research procedures were submitted for approval to the Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals (CEUA) of FCAV/Unesp Jaboticabal under the protocol #21/001469.

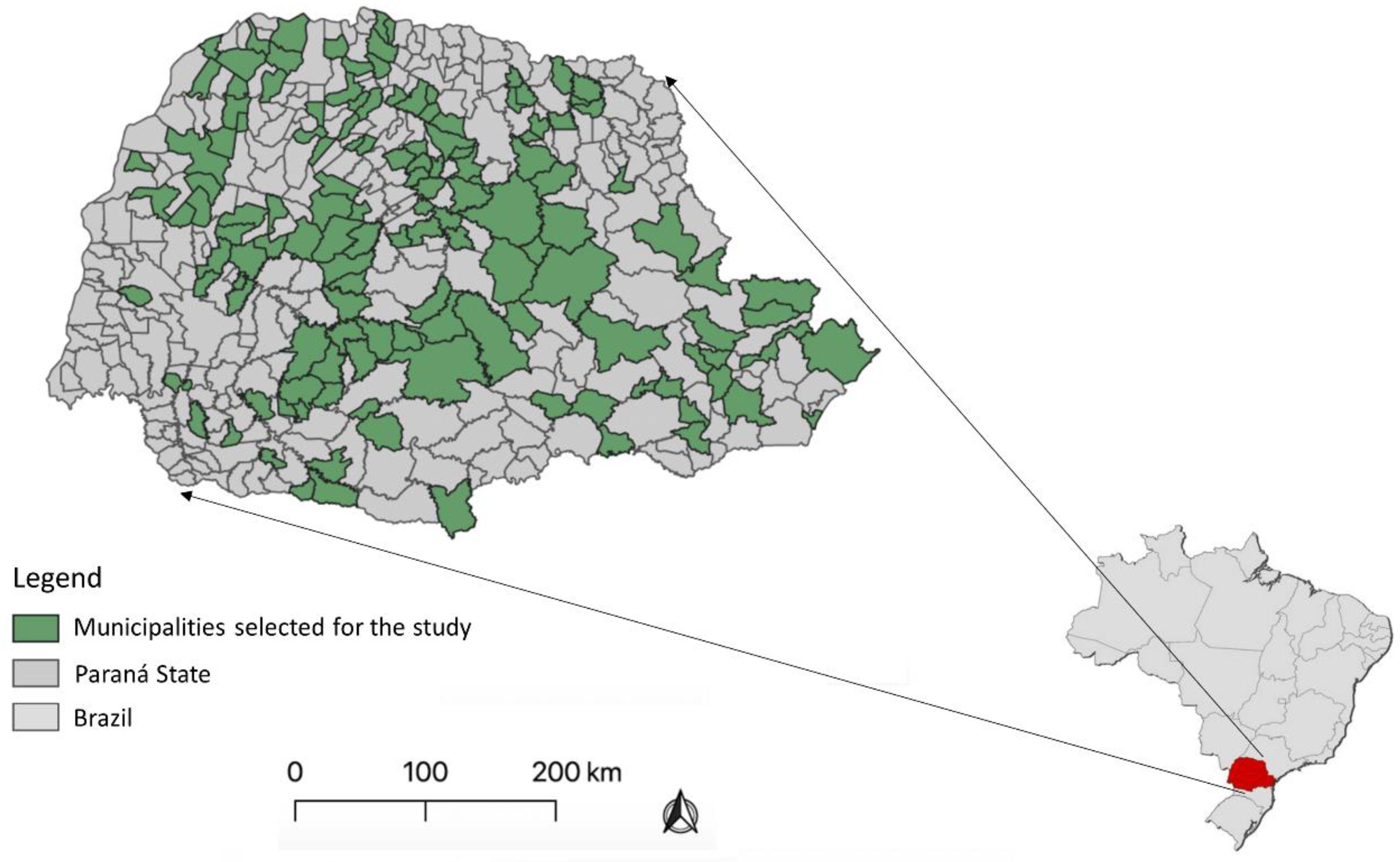

To conduct this study, the Agricultural Defense Agency of Paraná (ADAPAR) provided support in selecting 188 subsistence pig farms (SPF) from 136 different municipalities in the state of Paraná, Brazil. These farms were characterized as non-technical subsistence farms, and samples were collected by the ADAPAR team between January and March 2020. To ensure the reliability of the results, only farms with at least five adult pigs were included in the study, and a minimum distance of five kilometers was determined between the selected farms to minimize the risk of cross-contamination.

Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the selected municipalities.

For sample collection, only adult pigs over 8 months of age or already of reproductive age were considered, in accordance with the parameters established in

Table 1. The blood samples were collected from jugular vein using sterile disposable syringes and needles, and deposited in vacuum tubes, free of anticoagulant and with clot activator (BD® Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Blood serum was separated by centrifugation at 1500×g for 10 min, aliquoted into plastic graduated microtubes (Eppendorf®, Hamburg, Germany). The samples were transported to the Swine Medicine Laboratory at FCAV/Unesp Jaboticabal, where they transferred to a −20 °C freezer until further processing.

2.2. Epidemiological questionnaire application

To obtain epidemiological data on the properties, the owner completes a questionnaire that pertains to potential pigd- and property-level risk factors. The questionnaire was based on Loeffen et al. (2009) and comprised mostly of dichotomous questions with possible answers limited to "yes" or "no". The questionnaire covered demographic information such as sex, age, role (sow or boar) of the pigs and the risk factors analyzed were SPF located in settlement, proximity to peri-urban areas, extensive breeding, washing as a component in animal feed, proximity to landfills, proximity to nature reserves and contact with pigs.

2.3. Microscopic Agglutination Test (MAT) and titration of anti-Leptospira spp. antibodies.

For the serological detection of Leptospira spp., OIE guidelines were followed to perform the MAT, a standardized technique for serological diagnosis of the pathogen (Santa Rosa, 1970; OIE, 2021),. This technique is performed using a collection of live antigens from Leptospira spp. that includes 22 pathogenic serological variants (Australis, Bratislava, Autumnalis, Butembo, Castellonis, Batavie, Canicola, Whitcombi, Cinoptery, Grippotyphosa, Hebdomadis, Copenhageni, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Javanica, Panama, Pomona, Pyrogenes, Hardjo, Wolffi, Shermani, Tarassovi, Sentot) and 2 non-pathogenic serovars (Andamana and Patoc) as adopted by Petri et al. (2021). For laboratory analyses, the 24 serological variants identified above, which were in turn cultured in Leptospira Medium Base EMJH (Difco™, BD, NY, USA) for approximately 4 to 8 days and at a concentration of approximately 2.0 x 108 bacteria/mL, determined by counting in a dark-field microscope, were used. The principle behind MAT is simple, but it requires maintaining a panel of live leptospires, representing a biological risk and restricting its practice to specialized laboratories (Koizumi and Micardeau, 2020)

Briefly, a 1:50 mixture of Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS 1×, pH 7.4; Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) solution and blood serum is prepared. In addition, an aliquot of the serovar of Leptospira spp. from culture in the EMJH medium is added to react with the serum to be tested. At the end, 24 serovars are tested in each blood serum sample. Homogenization is performed and the plate is placed in an incubator at 37°C and the reaction is read after 40 minutes. The final dilution of the serum:antigen mixture is defined as 1:100 and is considered the reaction threshold (cut off). The sera that showed 50% of agglutinated leptospiras under the dark field microscope will be titrated with their respective antigens in a geometric series of dilutions of ratio 2. In the screening, the final titer is given as the reciprocal of the highest dilution at which agglutination occurred (Goris & Hartskeerl, 2014; Santa Rosa, 1970), in which each sample is classified as reactive or non-reactive with the aid of a dark field microscope with phase contrast.

2.4. Data analysis

The seroprevalence values obtained for each serovar tested considered a 95% confidence interval calculated by the Wilson method. We used Fisher's exact test (p < 0.05) to investigate possible associations between the variables in the property characterization questionnaire and the occurrence of Leptospira spp. seropositive animals, with each herd considered a sampling unit. The relative risk estimate (odds ratio) was also calculated considering 95% confidence interval. The analyses were performed using the EpiInfoₒ software (version 7.2.2.6-CDC, Atlanta, USA). Lastly, the calculation of the percentage of reactive samples was performed by dividing the total number of positive reactors by the total number of samples and multiplying this value by 100.

3. Results

3.1. Occurrence of antibodies anti-Leptospira spp.

Overall, out of the 1393 serum samples tested, 221 were identified as reagents with a titer of at 1:100 for at least one of the 24 serovars of

Leptospira spp. Tested. The prevalence of anti-

Leptospira spp. In the sampled properties was 15.87% (221/1393; 95% CI 13.95 – 17.78%). Out of the 188 properties tested, 92 had at least one reagent sample, representing a prevalence rate of 48.94% (95% CI 38.70% - 59.17%). The number of reactive samples by sorovar and antibody titer, as well as the prevalence rate and 95% confidence interval are presented in

Table 2. The most prevalent serovars in the study was Icterohaemorrhagiae with a seroprevalence of 4.88% (68/1393; 95% CI 3.75 - 6.01%), Butembo, with a prevalence of 1.72% (24/1393; 95% CI 1.04 - 2.41%), and Patoc, with a prevalence of 1.0% (23/1393%; 32.95%). None of the animals sampled showed antibodies against the serovars Australis, Autumnalis, Batavie, Cinoptery, Javanica, Pyrogenes, Shermani, Sentot and Andamana.

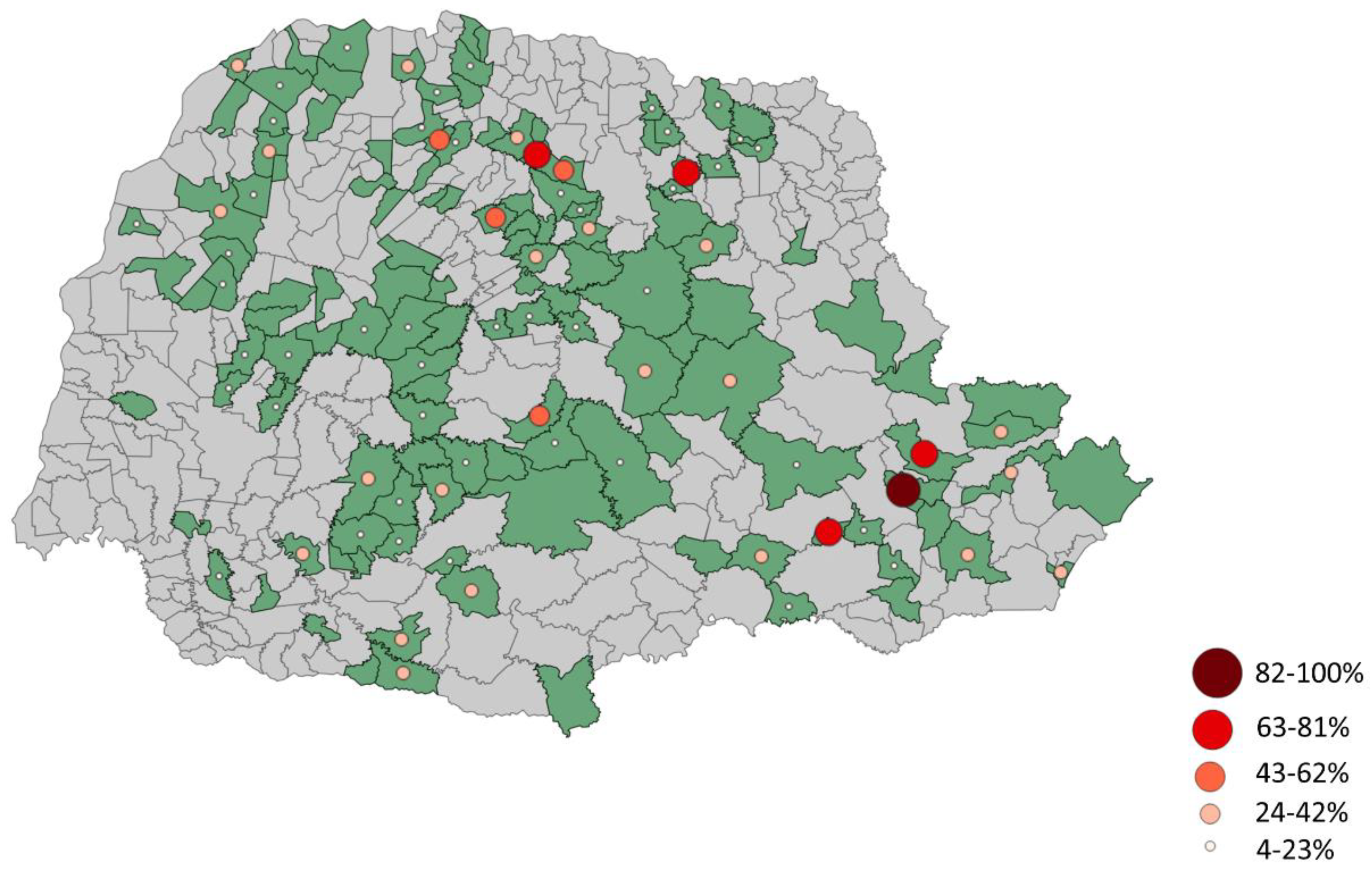

3.2. Distribution of seropositive animals for Leptospira spp.

Based on the MAT and analysis of data collected, it was found that the most commonly occurring serovar of

Leptospira spp. was Icterohaemorrhagiae, which was detected a prevalence of 17.99%. Additionally, Butembo and Pomona were also detected in 15 properties each, with a prevalence of 7.94%. These findings are presented in

Table 3. To provide a better understanding of the distribution of seroprevalence of animals against

Leptospira spp,

Figure 2 displays this information by municipality. Furthermore,

Table 3 describes the prevalence of each sorovar based on the number of properties with seroreactive animals. Overall, the prevalence of

Leptospira spp. was found to be 68.78%.

3.3. Risk factors associated with Leptospira spp. antibodies

Following data collection and analysis from epidemiological questionnaires answered by farmers in the study area, it was determined that none of the identified risk factors were found to be statistically significant in relation to the prevalence of leptospirosis in pigs.

Table 4 provides the risk ratio, 95% confidence interval, and

p-value for each analyzed risk factor, indicating that none of these factors were found to have a significant association with the occurrence of the disease.

4. Discussion

The detection of serogroups using MAT is dependent on the phase of the infection being investigated (Levett et al.,

2001). During the first phase of infection, low antibody titers against common antigens of

Leptospira spp., and cross-reactivity of serogroups are typical (Levett et al.,

2001; Bolin et al.

1992). Titers of 1:100 or 1:200 may suggest an early stage of infection, while higher titers are indicative of endemic infection (Picardeau et al.

2013). In our study, the low titers observed in most samples could suggest a recent exposure to

Leptospira spp, as shown in

Table 2. Furthermore, the presence of positive sera reactions to two serovars at the same time indicated cross-reactivity and confirmed the first phase of infection, as antibodies against common antigens of Leptospira are frequently induced during the acute phase of infection (Bertasio et al.

2020).

Based on our findings, it is evident that leptospirosis is a significant public health concern in the state of Paraná, particularly for those involved in subsistence agriculture. The high prevalence of seroreactivity (68.78%) suggests that

Leptospira spp. can be present in subsistence farms, even those that do not exclusively rear pigs. We observed variation in the identified serogroups (including Icterohaemorrhagiae, Butembo, Pomona, Tarassovi, Castellones, and others), which indicates that there are multiple sources of infection. However, Icterohaemorrhagiae (17.99%) and Butembo/Pomona (7.94%) were the most commonly detected serogroups (

Table 3). Results of seroprevalence of anti-

Leptospira spp. antibodies are essential to understand the epidemiology of infections caused by the pathogen in non-technical properties because animals are not immunized, thus the detection of antibodies is associated to infection.

A study by Oliveira et al. (2018) [2018] in the state of Paraná assessed the prevalence and risk factors associated with Leptospira infection in pigs raised in non-technified systems. The study involved serological test MAT performed on serum samples from 344 pigs across 86 rural properties, and the results revealed a 26.5% prevalence of seropositive pigs for Leptospira spp. The most prevalent serovars were L. interrogans serovar Copenhageni and L. borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo. Risk factors associated with infection included the presence of other animal species on the property, pigs' access to water from streams and creeks, and inadequate hygiene and sanitary management. A similar study was also conducted in the state of Pernambuco (Santos et al. 2019) which found that the most common serovars associated with infections in pigs were Icterohaemorrhagiae (39.1%), Pomona (25.9%), and Shermani (14.0%). Risk factors associated with infection included stagnant water sources, farms where the healthy animals were bred with sick ones, and properties with flooded areas.

The prevalence of Leptospira Icterohaemorrhagiae varies across different animal species. While the bacteria may be more commonly found in pigs than in cattle or horses in some cases, the situation may be reversed in other regions or rearing conditions (Ellis, 2010; Langoni et al. 2004; Yatbantoong et al., 2019).Our findings shown a significance for this serovar, being the more found serovar with prevalence rate of 17.99% present in 26.15% of properties. In certain regions, the prevalence of Leptospira Pomona, among other species, may exceed that of Leptospira Icterohaemorrhagiae, leading to a greater number of leptospirosis cases in pigs, cattle, and horses (Ellis, 2010; Smith et al. 2015; Aragão, 2021). Gaining insight into these differences in prevalence is essential for comprehending the epidemiology of leptospirosis and for devising appropriate prevention and control strategies.

In subsistence farming, Pomona is an important serovar in pigs as it can cause reproductive problems, such as abortion and stillbirths, as well as other clinical signs, such as fever and anemia. Pigs are considered natural carriers of the bacterium, shedding it in their urine and contaminating the environment (Faine et al. 1999), which can also affect other species, such as dogs, cattle, sheep and cats (Guedes et al. 2021; Aliberti et al. 2022; Hamond et al. 2019; Grippi et al. 2023; Donato et al. 2022). Incidental infections ruminants can occur due to co-grazing with other species, leading to outbreaks and severe clinical illness, while infections by adapted strains are usually chronic and only exhibit mild clinical signs, particularly with regards to reproductive function (Martins et al. 2012). In humans, infection with Pomona and other serovars can occur through contact with contaminated animal tissues or fluids, leading to a range of symptoms, from mild flu-like illness to severe disease (McBride et al. 2005)

To combat the spread of Leptospira spp. infection in subsistence pig production, it is crucial to implement measures such as improving housing conditions, controlling rodent populations, and providing veterinary assistance. Additionally, it is essential to educate pig farmers and other stakeholders on the importance of early detection, treatment, and prevention of Leptospira spp. infection in pigs to minimize the risk of zoonotic transmission to humans and other animal species. Overall, this study highlights the urgent need for robust surveillance and control strategies to prevent and control the spread of Leptospira spp. infection in subsistence pig production systems in Paraná, Brazil, and underscores the importance of One Health approaches to tackle zoonotic diseases like Leptospirosis.

5. Conclusions

This study has shed light on the significant prevalence of Leptospira spp. infection in subsistence pig production in the state of Paraná, Brazil. The high seroprevalence rate of Leptospira spp. antibodies in pigs indicates a considerable risk of zoonotic transmission to humans and other animal species. Moreover, the identification of significant risk factors, such as poor housing conditions, lack of rodent control, absence of veterinary assistance, and a history of reproductive problems, underscores the need for effective control measures to prevent and control the spread of Leptospirosis in subsistence pig production systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, L.G.d.O.; methodology, L.G.d.O., L.A.M. and J.H.T.d.C; formal analysis, G.F.d.S.; G.P.P.; F.A.M.P. A.C.B.M.; A.K.P.; investigation, J.H.T.d.C; resources, L.G.d.O.; writing—original draft preparation, G.F.d.S., F.A.M.P., A.K.P. and C.S.M.; writing—review and editing, F.A.M.P. and L.G.d.O.; supervision, L.G.d.O.; project administration, G.F.d.S and L.G.d.O.; funding acquisition, L.G.d.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

We are thankful to CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) for the Productivity Grant to L.G.O (CNPq Process #316447/2021-8).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee in Animal Use of the School of Agricultural and Veterinary Sciences, São Paulo State University, Campus Jaboticabal, under the protocol #21/001469. During the entire experiment, all animals received humane care in compliance with good animal practice to minimize animal sufferings during blood sampling, according to the animal ethics procedures and guidelines in Brazil.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Nivaldo Aparecido de Assis for the support in laboratory analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Levett, P.N. Leptospirosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001, 14, 296–326.

- Boqvist, S.; Thu, H.T.V.; Vågsholm, I.; Magnusson, U. The impact of Leptospira seropositivity on reproductive performance in sows in southern Viet Nam. Theriogenology 2002, 58, 1327–1335. [CrossRef]

- Faine, S.; Adler, B.; Bolin, C.; Perolat, P. Leptospira and Leptospirosis, 2nd ed.; MediSci: Melbourne, Australia, 1999.

- Pappas, G.; Papadimitriou, P.; Siozopoulou, V.; Christou, L.; Akritidis, N. The globalization of leptospirosis: Worldwide incidence trends. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 12, 351–357. [CrossRef]

- Bharti, A.R., Nally, J.E., Ricaldi, J.N., Matthias, M.A., Diaz, M.M., Lovett, M.A., Levett, P.N., Gilman, R.H., Willig, M.R., Gotuzzo, E., Vinetz, J.M., Peru-United States Leptospirosis Consortium. 2003. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect. Dis., 3 (12) (2003), 757-771. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, R.; Brenner, K.; Higgins, J.; Van der Merwe, D.; Harkin, K. REvaluations of land cover risk factors for canine leptospirosis: 94 cases (2002–2009). Prev. Vet. Med. 2011, 101, 241–249.

- Ward, M.P.; Guptill, L.F.; Wu, C.C. Evaluation of environmental risk factors for leptospirosis in dogs: 36 cases (1997–2002). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2004, 225, 72–77. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, W.A. Leptospirosis. In Diseases of Swine; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 483–554. Blackwell: Oxford, UK.

- Cilia, G.; Bertelloni, F.; Fratini, F. Leptospira Infections in Domestic and Wild Animals. Pathogens 2020, 9, 573. [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, L.D.S.; Domingos, S.C.B.; Di Azevedo, M.I.N.; Peruquetti, R.C.; De Albuquerque, N.F.; D′Andrea, P.S.; Botelho, A.L.D.M.; Crisóstomo, C.F.; Vieira, A.S.; Martins, G.; et al. Small Mammals as Carriers/Hosts of Leptospira spp. in the Western Amazon Forest. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 569004. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, W.A. Animal leptospirosis. Curr Top Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 387, 99–137.

- Cerri, D.; Ebani, V.V.; Fratini, F.; Pinzauti, P.; Andreani, E. Epidemiology of leptospirosis: Observations on serological data obtained by a “diagnostic laboratory for leptospirosis” from 1995 to 2001. New Microbiol. 2003, 26, 383–389.

- Soto, F.R.M.; Vasconcellos, S.A.; Pinheiro, S.R.; Bernarsi, F.; Camargo, S.R. 2007. Leptospirose suína. Arquivos do Instituto Biológico, 74, 4, p. 379-395.

- Ngugi, J.N.; Fèvre, E.M.; Mgode, G.F.; Obonyo, M.; Mhamphi, G.G.; Otieno, C.A.; Cook, E.A.J. Seroprevalence and associated risk factors of leptospirosis in slaughter pigs; a neglected public health risk, western Kenya. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 403. [CrossRef]

- Strutzberg-Minder, K.; Tschentscher, A.; Beyerbach, M.; Homuth, M.; Kreienbrock, L. Passive surveillance of Leptospira infection in swine in Germany. Porc. Health Manag. 2018, 4, 10. [CrossRef]

- Strutzberg-Minder, K.; Ullerich, A.; Dohmann, K.; Boehmer, J.; Goris, M. Comparison of Two Leptospira Type Strains of Serovar Grippotyphosa in Microscopic Agglutination Test (MAT) Diagnostics for the Detection of Infections with Leptospires in Horses, Dogs and Pigs. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 464. [CrossRef]

- Instrução Normativa nº 50, de 24 de Setembro de 2013. Altera a lista de doenças passíveis da aplicação de medidas de defesa sanitária animal, previstas no art. 61 do Regulamento do Serviço de Defesa Sanitária Animal. Ministério Da Agricultura, Pecuária E Abastecimento; Poder Executivo: Brasília, Brazil, 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/sanidade-animal-e-vegetal/saude-animal/programas-de-saude-animal/sanidade-suidea/legislacao-suideos/2013IN50de24desetembrode.pdf/view (accessed on 30 April 2023).

- Guedes, I.B.; Souza, G.O.; Castro, J.F.P.; Cavalini, M.B.; Souza Filho, A.F.; Heinemann, M.B. Usefulness of the ranking technique in the microscopic agglutination test (MAT) to predict the most likely infecting serogroup of Leptospira. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 654034. [CrossRef]

- Dung, L.P.; Hai, P.T.; Hoa, L.M.; Mai, T.N.P.; Hanh, N.T.M.; Than, P.D.; Tran, V.D.; Quyet, N.T.; Hai, H.; Ngoc, D.B.; Thu, N.T.; Mai, L.T.P. A case-control study of agricultural and behavioral factors associated with leptospirosis in Vietnam. BMC Infect Dis. 2022 Jun 29;22(1):583. [CrossRef]

- Viroj, J.; Claude, J.; Lajaunie, C.; Cappelle, J.; Kritiyakan, A.; Thuainan, P.; Chewnarupai, W.; Morand, S. Agro-Environmental Determinants of Leptospirosis: A Retrospective Spatiotemporal Analysis (2004–2014) in Mahasarakham Province (Thailand). Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 115. [CrossRef]

- Calderón, A.; Rodríguez, V.; Máttar, S.; Arrieta, G. Leptospirosis in pigs, dogs, rodents, humans, and water in an area of the Colombian tropics. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2014, 46, 427–432. [CrossRef]

- Guerra, M.A. Leptospirosis: Public health perspectives. Biologicals, v.41, p.295-297, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Barragan, V., Olivas, S., Keim, P., Pearson, T. 2017. Critical knowledge gaps in our understanding of environmental cycling and transmission of Leptospira spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 83 (19), e01190-e01217. [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, H.G.; Monteiro, G.R.; Oliveira, C.C.G.; Suassuna, F.B., Queiroz, J.W., et al. Leptospirosis in a subsistence farming community in Brazil. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2008; 102: 1233–1238. [CrossRef]

- Favero, A. C. M.; Pinheiro, S. R.; Vasconcelos, S. A.; Morais, Z. M.; Ferreira, F.; Ferreira Neto, J. S. 2002. Sorovares de Leptospiras predominantes em exames sorológicos de bubalinos, ovinos, caprinos, equinos, suínos e cães de diversos estados brasileiros. Ciência Rural, Santa Maria, 32, 4, 613-619.

- Ramos, A. C. F., Souza, G. N., & Lilenbaum, W. 2006. Influence of leptospirosis on reproductive performance of sows in Brazil. Theriogenology, 66(4), 1021–1025. [CrossRef]

- zevedo, S. S., Oliveira, R. M., Alves, C. J., Assis, D. M., Aquino, S. F., Farias, A. E. M., Assis, D. M., Lucena, T. C. C., Batista, C. S. A., Castro, V., & Genovez, M. E.. (2008). PREVALENCE OF ANTI-LEPTOSPIRA SPP. ANTIBODIES IN SWINE SLAUGHTERED IN THE PUBLIC SLAUGHTERHOUSE OF PATOS CITY, PARAÍBA STATE, NORTHEAST REGION OF BRAZIL. Arquivos Do Instituto Biológico, 75(4), 517–520. [CrossRef]

- Petri, F.A.M.; Sonalio, K; Almeida, H.M.d.S.; Mechler-Dreibi, M.L.; Galdeano, J.V.B.; Mathias, L.A.; Oliveira, L.G. Cross-sectional study of Leptospira spp. In commercial pig farms in the state of Goiás, Brazil. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2020 Nov 19;53(1):13. [CrossRef]

- Delbem, A. C. B.; Freire, R. L.; Silva, C. A.; Müller, E. E.; Dias, R. A.; Neto, J. S. F.; Freitas, J. C. 2004. Fatores de risco associados a soropositividade para leptospirose em matrizes suínas. Ciência Rural, Santa Maria, 34, 3, 847-852. 2. [CrossRef]

- Santa Rosa, C. A. Diagnóstico laboratorial das leptospiroses. Revista de Microbiologia, 1970, 1, 97-109.

- World Organization of Animal Health—OIE. Chapter 3.1.12. Leptospirosis. In Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals; OIE: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 1–13.

- Koizumi, N.; Micardeau, M. Leptospira spp. Methods and Protocols; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 277–286.

- Bolin, C.A.; Cassells, J.A. Isolation of Leptospira interrogans serovars ratislava and hardjo from swine at slaughter. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 1992, 4, 87–89.

- Picardeau, M. Diagnosis and epidemiology of leptospirosis. Méd. Mal. Infect. 2013, 43, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Bertasio, C.; Papetti, A.; Scaltriti, E.; Tagliabue, S.; D’Incau, M.; Boniotti, M.B. Serological Survey and Molecular Typing Reveal New Leptospira Serogroup Pomona Strains among Pigs of Northern Italy. Pathogens 2020, 9, 332. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R. C. et al. Prevalência e fatores de risco associados à infecção por Leptospira spp. em suínos de criações não-tecnificadas no estado do Paraná, Brasil. Semina: Ciências Agrárias, Londrina, v. 39, n. 6, p. 2565-2574, 2018. Disponível em: http://www.uel.br/revistas/uel/index.php/semagrarias/article/view/31022. (Access on 07 April. 2023).

- Loeffen, W.L.A.; van Beuningen, A.; Quak, S.; Elbers, A.R.W. Seroprevalence and risk factors for the presence of ruminant pestiviruses in the Dutch swine population, Veterinary Microbiology, 2009, 136, 240-245. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.V.B.d; Mathias, L.A.; Feitosa, P.J.d.S.; Oliveira, J.M.B.; Pinheiro-Júnior, J.W.; Brandespim, D.F. Risk factors associated with leptospirosis in swine in state of Pernambuco, Brazil. 2019. Arquivos Do Instituto Biológico, 86, e0632017. [CrossRef]

- Langoni H, Medeiros LM, Ribeiro MG, et al. (2004). Soroprevalência e fatores de risco associados à leptospirose em suínos no Estado de São Paulo. Arquivos do Instituto Biológico, 71(3), 259-264. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/aib/v71n3/a01v71n3.pdf.

- atbantoong, N.; Chaiyarat, R. Factors Associated with Leptospirosis in Domestic Cattle in Salakphra Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1042. [CrossRef]

- Callan, R.J. Leptospirosis. In Large Animal Internal Medicine, 4th ed.; Smith, B.P., Ed.; Mosby, Inc.: Maryland Heights, MO, USA, 2009; pp. 967–970. Smith, B.P. (Ed.) Mosby, Inc.: Maryland Heights, MO, USA.

- Aragão, A. T. I.. (2021) Soroprevalência e fatores de risco associados à leptospirose em equinos reprodutores no Estado de Santa Catarina, Brasil, nos anos de 2016 e 2020. Dissertação de Mestrado, Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. (Accessed on 01 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Guedes, I.B.; de Souza, G.O.; de Paula Castro, J.F.; Cavalini, M.B.; de Souza Filho, A.F.; Maia, A.L.P.; Dos Reis, E.A.; Cortez, A.; Heinemann, M.B. Leptospira interrogans serogroup Pomona strains isolated from river buffaloes. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 194. [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, A.; Blanda, V.; Di Marco Lo Presti, V.; Macaluso, G.; Galluzzo, P.; Bertasio, C.; Sciacca, C.; Arcuri, F.; D’Agostino, R.; Ippolito, D.; Pruiti Ciarello, F.; Torina, A.; Grippi, F. Leptospira interrogans Serogroup Pomona in a Dairy Cattle Farm in a Multi-Host Zootechnical System. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 83. [CrossRef]

- Hamond, C.; Silveira, C.S.; Buroni, F.; Suanes, A.; Nieves, C.; Salaberry, X.; Aráoz, V.; Costa, R.A.; Rivero, R.; Giannitti, F.; et al. Leptospira interrogans serogroup Pomona serovar Kennewicki infection in two sheep flocks with acute leptospirosis in Uruguay. Transbound. Emerg. Diseases. 2019, 66, 1186–1194.

- Grippi, F.; Cannella, V.; Macaluso, G.; Blanda, V.; Emmolo, G.; Santangelo, F.; Vicari, D.; Galluzzo, P.; Sciacca, C.; D’Agostino, R.; Giacchino, I.; Bertasio, C.; D’Incau, M.; Guercio, A.; Torina, A. Serological and Molecular Evidence of Pathogenic Leptospira spp. in Stray Dogs and Cats of Sicily (South Italy), 2017–2021. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 385.

- Donato, G.; Masucci, M.; Hartmann, K.; Goris, M.G.A.; Ahmed, A.A.; Archer, J.; Alibrandi, A.; Pennisi, M.G. Leptospira spp. Prevalence in Cats from Southern Italy with Evaluation of Risk Factors for Exposure and Clinical Findings in Infected Cats. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1129. [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.; Brandão, F.Z; Hamond, C.; Medeiros, M., Lilenbaum, W. Diagnosis and control of an outbreak of leptospirosis in goats with reproductive failure. Vet J. 2012 Aug;193(2):600-1. [CrossRef]

- McBride AJA, Athanazio DA, Reis MG, Ko AI. Leptospirosis. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2005; 18: 376–386.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).