Introduction

African Swine Fever (ASF) is a highly contagious viral disease affecting domestic pigs with severe negative implications for food security and developing economies. Since its introduction into Nigeria over two decades ago, ASF has caused near-annual epizootic-scale outbreaks with devastating impacts on smallholder pig farmers whose livelihoods depend heavily on swine production [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These resurgent outbreaks have raised pressing questions about the virus, particularly the genotypes in circulation and the factor(s) fueling its persistence.

Until recently, genotype I had been the dominant variant in Nigeria. However, the recent identification of genotype II marked a turning point, suggesting a potential shift in the epidemiology of ASF within the country [

5]. This discovery underscores the need for active surveillance to determine whether the current wave of infections is driven by genotype II, genotype I, both, or even an entirely new genotype, prompting this study to sample pigs during known outbreak periods. Also, in order to understand the factor(s) driving the resurgence, pigs, hard ticks, and farm behaviors were also assessed during non-outbreak periods.

Japanese encephalitis (JE) has long been a significant public health challenge, especially in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific, and is spread primarily by mosquitoes of the

Culex genus [

6]. Recent estimates placed the burden in 24 endemic countries at approximately 67,900 cases annually—an incidence rate of 1.8 per 100,000 people—while globally, cases are estimated at approximately 2,114 annually, with an incidence rate of 0.5 per 1,000,000 total population [

7,

8].

Although JE is well-documented in Asia, its presence in Africa remains ambiguous, with Angola being the only country to have detected the virus [

9]. In Nigeria, evidence of JEV circulation is sparse. Serological surveys have reported antibody titers in 11.5% [

10] and 35.1% [

11] of pigs—suggestive of natural exposure and perhaps cryptic circulation of the virus in the swine population. Despite the compelling serological surveys, no study in Nigeria has embarked on a confirmatory molecular surveillance of the pathogen in pigs and mosquitoes.

This study presents two independent investigations into the epidemiology of African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV)—an endemic pathogen—and Japanese Encephalitis Virus (JEV)—potentially an emerging pathogen—in Southern Nigeria. Although these viruses differ biologically, with distinct transmission cycles, host dynamics, and public health implications, both are relevant within the shared context of pig farming in the region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with national and institutional guidelines, with ethical approval obtained from NHREC (NHREC/01/01/2007) and AUCC (AEC/02/123/22). All sampling procedures adhered to animal welfare standards and were performed exclusively by licensed veterinarians. Prior to blood sample collection, farmers were informed of the survey’s objectives and its rationale. Participation was entirely voluntary, with individuals free to withdraw at any point.

2.2. Study Area

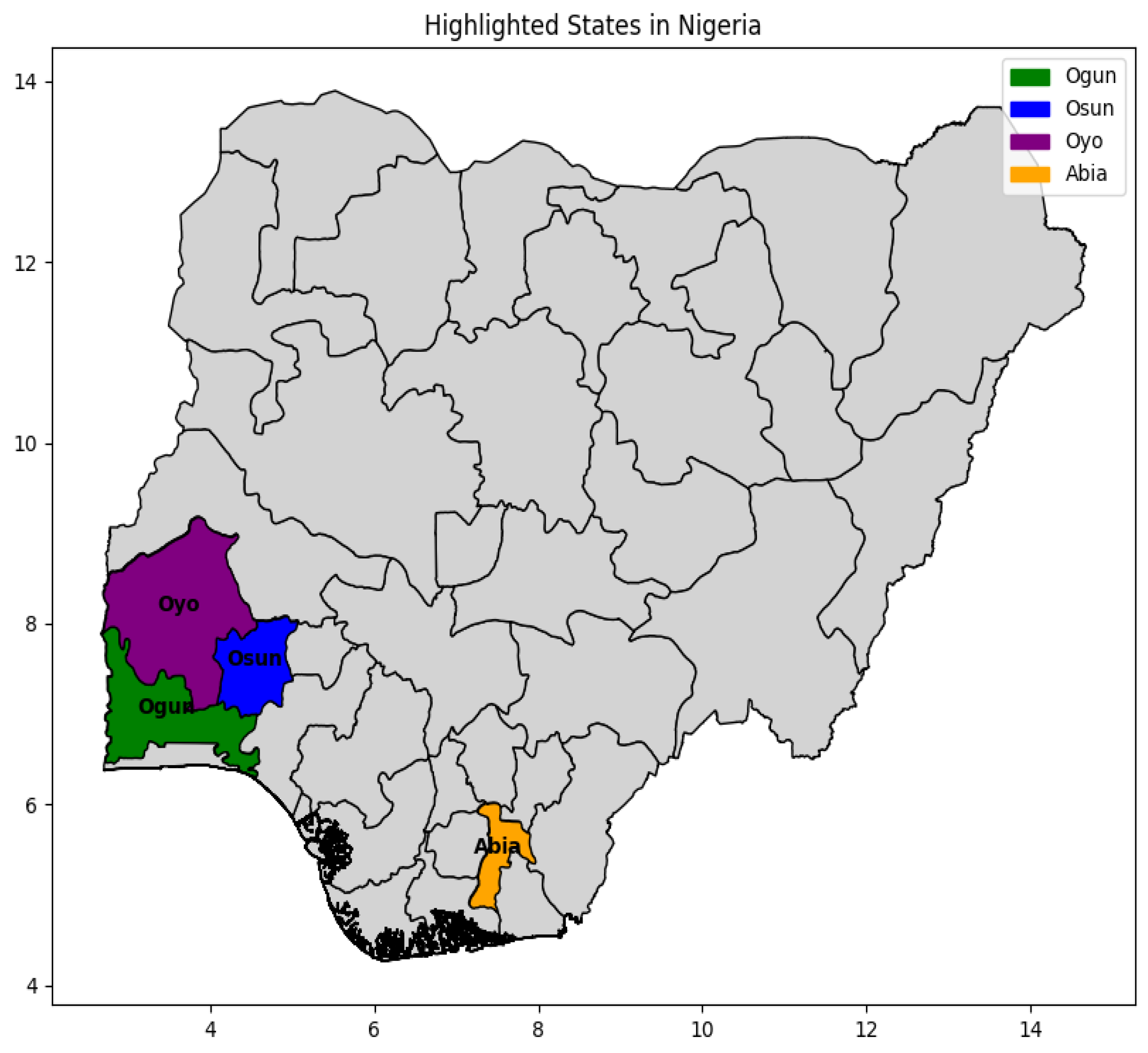

The investigations were conducted across pig farms and abattoirs in Ogun and Oyo States, and only across farms in Osun and Abia States, Southern Nigeria (

Figure 1).

2.3. Study Design and Field Data Collection

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted between September 2022 and August 2023. During this period, 40 pig farms and two abattoirs were visited, and a total of 231 whole blood samples were collected for analysis. At each site, observed ticks were collected, mosquito traps were deployed, and insects captured from the traps were retrieved. Data collection comprised two main components: (1) standardized questionnaires administered to farm personnel, and (2) farm-level risk assessments conducted by the research team. Both approaches focused on risk factors for African swine fever virus (ASFV) and were applied only to farms without active ASF cases at the time of visit.

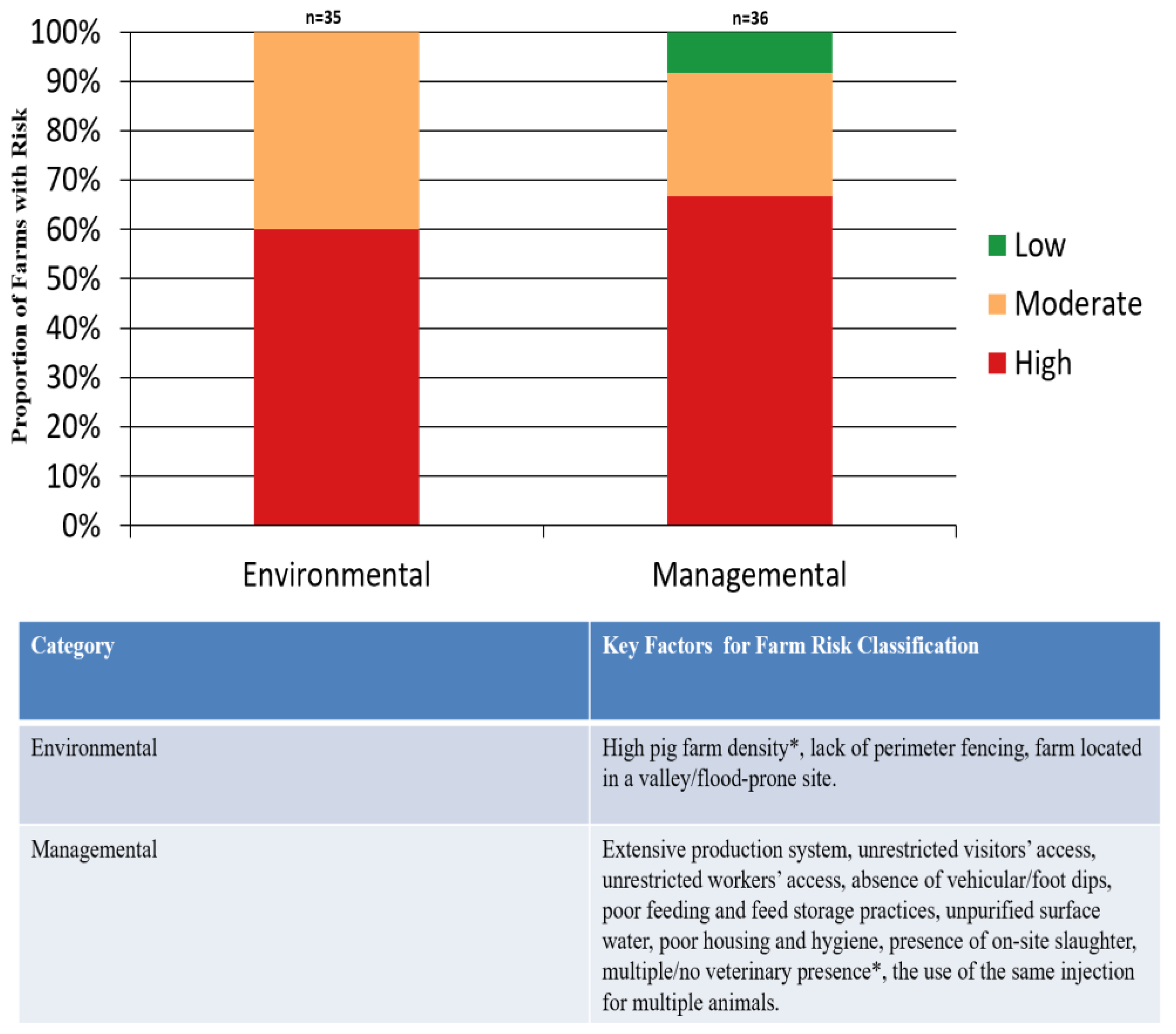

The risk assessment process involved two steps: (A) extraction of risk factors from existing literature on ASF, followed by grouping them into two categories—environmental and managemental [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]; and (B) evaluation of each farm for the presence of factors within these categories. A farm exhibiting a number of factors (i.e., 3/3 for environmental and 7/10 and above for managemental) was classified as having a high risk in these categories. A farm exhibiting 2/3 or 4-6/10 was categorized as medium risk, and one exhibiting 1/3 or 1-3/10 of the factors was considered as having a low risk.

2.4. Sampling, Processing, and Storage

2.4.1. Pig Blood

From each pig, 5 mL of whole blood was collected. A 1.5 mL aliquot was preserved in DNA/RNA Shield™ (ZYMO RESEARCH) for ASFV nucleic acid testing, while the remaining 3.5 mL was processed to obtain plasma. The plasma was divided into three portions: one (unpreserved) was used for ASFV ELISA antibody detection, another—stored in DNA/RNA Shield™—for JEV RT-qPCR, and a third, unpreserved, for JEV antibody detection. All samples were stored at –20 °C until further analysis.

2.4.2. Arthropod

Hard Ticks were collected from pigs and their immediate environment. Each tick was bisected, and halves were pooled in groups (a maximum of five halves per pool), resulting in four pools from eighteen ticks. All pools were preserved in DNA/RNA Shield™ and stored at –20°C.

Overnight mosquito trapping using BG-Sentinel™ traps (in Ogun, Osun, and Oyo) and Dynatrap™ UV light traps (in Abia) yielded a total of 616 adult mosquitoes. Captured specimens were transported on ice and stored at –20 °C. Subsequently, mosquitoes were sorted by genus and dissected into thorax and abdomen. Thoraxes were stored individually, while abdomens were pooled (approximately 20 per pool), resulting in 31 pools preserved in DNA/RNA Shield™ and stored at –80 °C.

2.5. Nucleic Acid Detection in Pigs and Arthropods

For ASFV, total DNA, from a total of 231 samples, was extracted from 200 µL of whole blood using the QIAamp Viral DNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). All four tick pools were homogenized with glass beads prior to DNA extraction using the same kit. PCR targeting p72 and p54 genes was carried out using a 25 µL reaction mix: 22 µL of lyophilized PuReTaq™ Ready-To-Go™ PCR mix (Cytiva), 0.25 µM of each primer, and 3 µL of DNA extract, with all results benchmarked against a positive control [

18,

19].

For JEV, RNA was extracted from a total of 204 pig plasma samples and 31 mosquito pools using the QIAamp Viral RNA Kit. RT-qPCR targeting the NS5 gene was performed using the Superscript III Platinum® One-Step RT-qPCR system and a primer-probe set (JEV1-F: ATCTGGTGYGGYAGTCTCA; JEV1-R: CGCGTAGATGTTCTCAGCCC; JEV1-Pr: CGGAACGCGATCCAGGGCAA) for a 62 bp region. To validate, an additional RT-qPCR targeting the NS1 gene was run using TaqPath reagents on the Roche LightCycler 96 system, as described by Chapagain et al., (2022) [

20]. Samples with Ct values <40 were deemed positive, with all results benchmarked against a JEV g-block positive control.

2.6. Antibody Detection in Pigs

ASFV antibodies were screened in 46 randomly selected plasma samples using the Elabscience indirect ELISA kit (E-AD-E106) coated with p30 antigens. Per manufacturer’s instructions, samples were classified as positive (S/P ≥ 50%), negative (S/P < 40%), or invalid (S/P 40–50%).

JEV antibody screening was performed on 126 randomly selected plasma samples using the Elabscience IgG ELISA kit (E-AD-E002). Optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm and 630 nm; samples with OD > 0.2 were considered seropositive. The assay had a reported specificity of 98.2% and sensitivity of 98.3%.

2.7. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

Selected ASFV-positive samples (DNA) were quantified using the Qubit™ High Sensitivity DNA Assay. Host DNA was removed using the NEBNext® Microbiome DNA Enrichment Kit, after which libraries were prepared and sequenced on the Oxford Nanopore GridION platform using MinKNOW™ software.

2.8. Statistical and Bioinformatic Analysis

2.8.1. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses using Python (Pandas library) were employed to summarize farm practices and risk scores obtained from questionnaires and farm assessments. Matplotlib was used for visualizations.

2.8.2. Reference-Based Genome Assembly and Genotype Assignment

High-quality reads (Q score ≥ 9) were aligned to 17 ASFV reference genomes using minimap2. The genome with the highest coverage and identity was selected for final analysis. Samples with a minimum average read depth of 20× were considered adequate for genotype assignment.

3. Results

3.1. ASFV PCR, Serology, and Genotyping Results

Out of 231 pig blood samples collected across four Nigerian states—Ogun (n = 61; 50 from farms and 11 from an abattoir), Osun (n = 66; all from farms), Oyo (n = 54; 52 from farms and 2 from an abattoir), and Abia (n = 50; all from farms)—PCR screening using p72 primers confirmed ASFV in 27 pigs, representing an overall detection rate of 11.69%. All positives were detected during the outbreak sampling period, representing a 100% positivity rate among samples collected during that time. Of the remaining samples, 35 yielded inconclusive results, which were subsequently designated as negative following confirmatory testing with p54 primers. Additionally, all four pools of ticks (representing 18 ticks, all hard ticks) tested negative by PCR. All 46 plasma samples screened for ASFV antibodies were seronegative.

Reference-based genome assembly was carried out on 13 ASF-positive samples. Seven complete genome assemblies were generated with each showing 96.5–96.8% genome coverage and read depths ranging from 127 to 435 reads per locus. All assemblies aligned best to the Georgia genotype II reference strain (NC_044959.2).

3.2. JEV RT-qPCR and Seropositivity

All 204 pig plasma samples and 616 mosquito specimens—comprising Culex (90.70%), Aedes (7.60%), and Anopheles (1.60%) spp. across 31 pools—tested negative for JEV using both primer sets described above. Of the 126 plasma samples analyzed for serology, 72 (57.14%) were seropositive. Seroprevalence was highest in Abia State (66.67%), followed by Oyo (60.53%), Osun (58.33%), and Ogun (40.91%).

3.3. Demographics

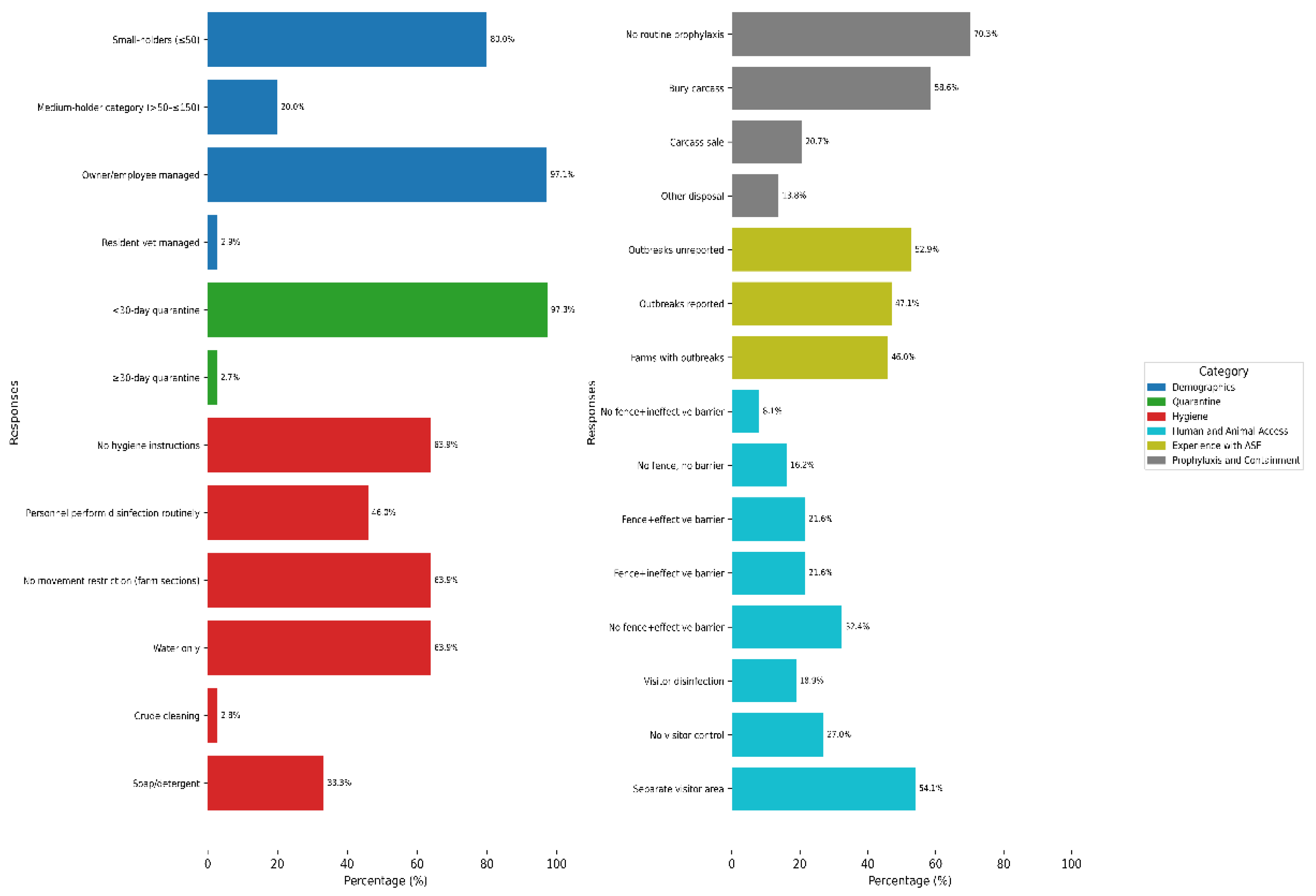

Small-holder units (≤ 50 pigs), peri-urban (54.29%) and rural (25.71%) settings dominated the sampling, with an overwhelming majority of farms managed by owners/employees (

Figure 2). Farm distribution by state was relatively balanced: Oyo and Osun each contributed 27.03%, Ogun 24.32%, and Abia 21.62%. Ogun and Oyo States each accounted for 50% of the sampled abattoirs.

1

3.4. Farm Risk Evaluation to ASFV Infection using Questionnaire Findings

3.4.1. Sourcing and quarantine (n = 37)

Almost two-thirds of farms (64.86%) sourced pigs from distant locations. In addition, using the farm’s own breeding stock (i.e., retaining pigs born on-site for restocking) was also a common practice (62.16%). Other approaches included sourcing pigs from nearby farms (51.35%) and importing pigs from outside Nigeria (5.41%). Although most farms claimed to quarantine new arrivals, in reality, they fell short of recommended practice (

Figure 2).

3.4.2. Hygiene and movement control

Nearly two-thirds of farms lacked documented hygiene protocols and relied exclusively on water for cleaning waste and blood-contaminated areas. Fewer than half implemented personnel disinfection or restricted movement between farm sections (

Figure 2). A small proportion of farms (2.78%) reported using crude cleaning methods, such as manually removing wastes from pens without washing or disinfecting, or wiping off liquid waste and blood stains with only cloths (

Figure 2). With regard to equipment management, a majority (91.89%) preferred purchasing tools over borrowing or lending. Cleaning and disinfection practices of these tools varied but were relatively evenly distributed: 12 farms (32.43%) each reported cleaning either after use, on occasion, or both before and after use. Five farms (13.54%) did not use any disinfectant. IZAL, a phenol-based disinfectant, was the most commonly reported product (24.32%), followed by combinations of formalin and hypochlorite (5.41%), along with several others.

2

3.4.3. Human and animal access (n = 37)

Structural biosecurity measures were generally insufficient, with many farms lacking effective fencing, permitting contact between pigs and wild or stray animals and birds. Also, many farms implemented inadequate visitor control protocols (

Figure 2). Concerning the introduction of pigs from external sources, 72.97% of farms fully restricted such entries. Among the minority that allowed them, the primary reason cited was stud service (21.62%).

3.4.4. Experience with ASF outbreaks (n = 37)

Approximately 46% of farms reported having experienced an outbreak; however, only about half of these incidents were communicated to the authorities (

Figure 2). Among the unreported cases, the most common reason cited was a perceived lack of support (77.78%), followed by fear of closure (11.11%), while the remaining 11.11% offered no specific justification.

3.4.5. Prophylaxis and carcass management

Routine vaccination and deworming practices were largely absent across farms (

Figure 2). Additionally, most farms (56.76%) did not consult veterinarians during pig procurement, with only one farm (2.7%) engaging veterinary services exclusively at the point of purchase.

Carcass disposal practices varied among farms, ranging from on-site burial (on or near the farmland) to the sale of carcasses (

Figure 2). Additional methods included disposal in bushes (2 farms; 6.90%), rivers (1 farm; 3.45%), and dunghills (1 farm; 3.45%). Two farms (6.90%) reported no pig mortality at the time of the survey.

3

3.5. Farm Risk Evaluation to ASFV Infection using Farm Assessment

The majority of the farms had a high environmental and managemental risk of ASF (

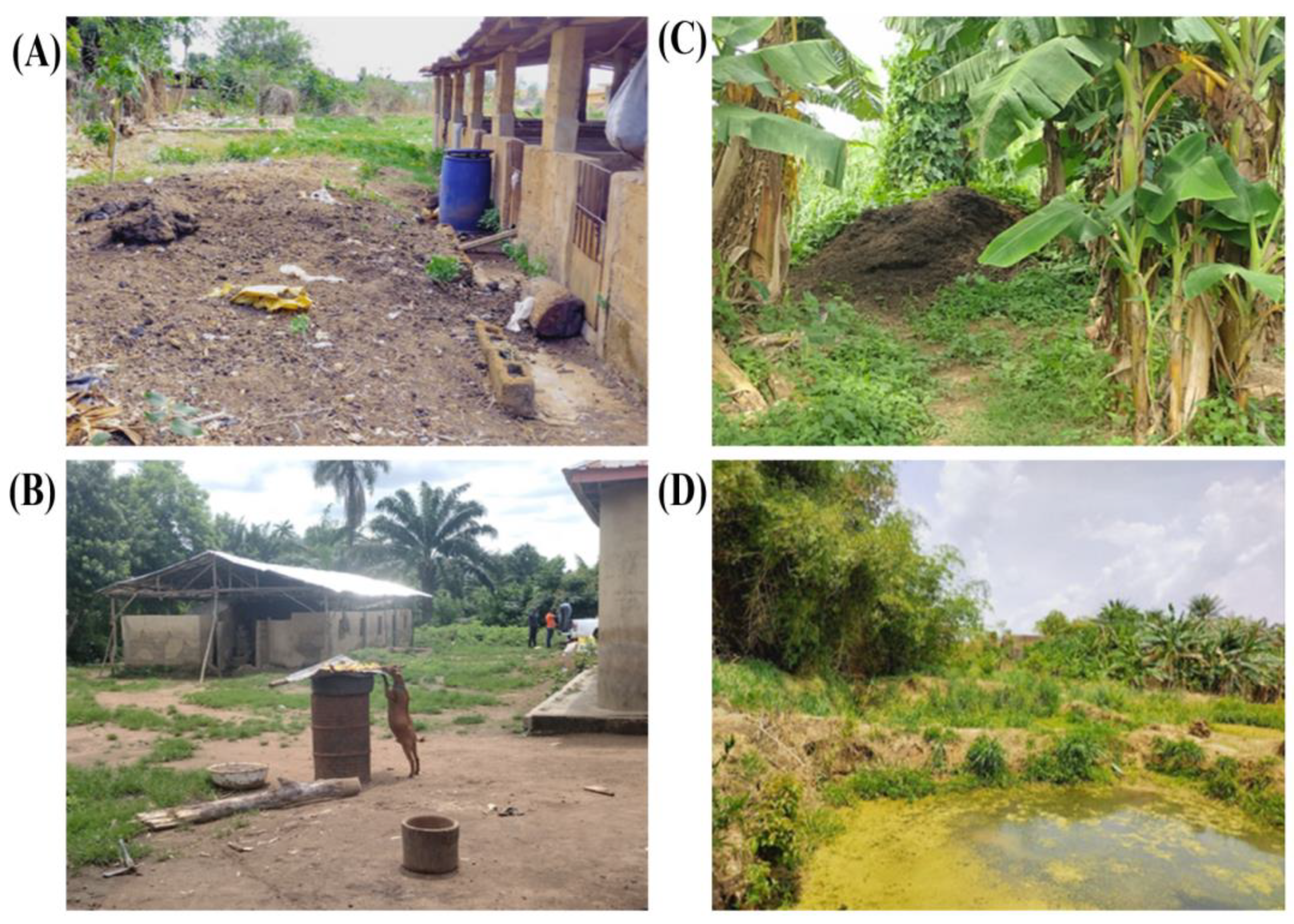

Figure 3). Also,

Figure 4 captures some visual examples of biosecurity breaches observed during the farm assessment.

Due to the lack of any definitive presence of JEV nucleic acid to confirm the presence of the agent, questionnaire and farm risk analysis regarding JEV were not undertaken.

4. Discussion

The identification of ASFV genotype II in positive samples during the outbreak period indicates the growing nature of this genotype in Nigeria, aligning with global epidemiological patterns. This finding corroborates previous reports that designate genotype II as the primary genotype responsible for the current global pig pandemic [

21,

22]. In the areas sampled and the viruses genotyped, it appears that ASFV genotype II may be replacing the ASFV genotype I in southern Nigeria.

This study also highlights that the recurrent nature of ASF appears largely shaped by structural and human-inclined risk factors, particularly inadequate infrastructure, suboptimal management practices, and economically motivated behaviors. Clearly, to control ASF spread within southern Nigeria, awareness and improved biosecurity measures are needed. Specifically, inadequate quarantine practices as well as hygiene deficiencies are both likely to have facilitated the spread of ASFV.

Also, disease containment practices following pig mortalities remained inadequate. Farmers frequently resorted to improper carcass disposal—such as panic sales, on-site burials, and discarding remains in bushes or waterways—thereby increasing the risk of environmental transmission. These practices are likely to be influenced by limited awareness of proper biosecurity protocols and economic constraints.

A key structural weakness observed was the predominance of smallholder operations—most farms housed ≤50 pigs and were managed by owners or staff with limited veterinary oversight. This pattern mirrors findings from other ASF-endemic regions, where the subsistence nature of pig farming often results in weak or poorly enforced biosecurity frameworks [

25,

26,

27,

28], fostering an environment highly conducive to ASFV transmission.

Tick sampling at farms yielded only hard ticks, and these were consistently negative, as anticipated, as hard ticks are not thought to be vectors of ASFV.

Regarding JE, this study represents the first to integrate serological, molecular, and vector surveillance, providing a still incomplete epidemiological picture of JE in Nigeria—a country where the disease’s presence has remained largely enigmatic. Despite rigorous RT-qPCR analysis of abundant pig and mosquito samples gathered from various areas in this study, there was no evidence of any JEV found. Conversely, an ELISA for antibodies proved positive in a high percentage of pig plasma samples. This corresponds to a serology study done on swine in the same region, which yielded positive antibodies to JEV, but no definitive evidence of clinical disease or virus [

11]. Similarly, a serologic study done in Ilorin (north of this study’s sites) described antibodies to JEV found in humans [

29]. Then, the virus itself was detected in Angola, far south of Nigeria, in a patient suffering severely from Yellow Fever infection, but a de novo assembly of sample reads yielded JEV in addition to the YF genome [

9]. Unfortunately, cross-reactivity of flaviviruses is a well-established phenomenon [

30,

31], and the pantheon of flaviviruses continues to expand. It is thought that many of the flaviviruses originate on the African continent and then are carried elsewhere to cause emerging diseases, e.g., West Nile virus, Zika virus. A recent, less well-known flavivirus, transmitted by

Culex spp., is Usutu virus, which is known to infect pigs without causing clinical disease [

32]. However, there are likely many other flaviviruses yet to be discovered, any of which might have caused the serologic positivity. Consequently, the results in this current study may have only added limited but important information, with the lack of any JEV genomic material found in numerous pigs and mosquitoes sampled. But the overall preponderance of

Culex mosquitoes obtained in the trapping is an indication of the fertile transmission capacity of JEV when/if it enters the population.

5. Conclusions

This dual-pathogen epidemiological study underscores the necessity of proactive surveillance in generating critical data for understanding disease epidemiology and informing targeted intervention strategies. In the case of ASF, multifactorial biosecurity lapses appear to be the primary drivers of epizootic-scale outbreaks in Southern Nigeria. Strengthening biosecurity measures, implementing policy interventions that provide financial or material support for farm infrastructure and compensation for losses, incentivizing outbreak reporting, and enhancing farmer education on effective disease prevention and control are essential steps toward mitigating recurrent outbreaks. For JEV, although the full story of the disease is still unfolding, seropositivity rates in pigs are high, in the apparent absence of any circulating virus. Cross-reactivity to another flavivirus may have been responsible for the positive serology. JEV is transmitted by Culex, and the preponderance of this species of mosquitoes at the pig farms is a cause for concern, and continued surveillance to detect if/when JEV might emerge is recommended.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N.H.; methodology, A.S.O., J.F., O.A.O., A.E.S., F.S.M., O.A., A.O.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.O.; writing—review and editing, A.N.H., C.B., F.B., C.T.H.; supervision, A.N.H., C.T.H.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Global Partnership for Animal and Zoonotic Disease Surveillance, USDA-APHIS, AP22VSD&B000C030.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the farmers who granted permission to access and sample their animals. We also thank the staff of the Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Osun and Ogun States, who assisted us with the database of pig farmers in their regions and also with the sample collection. We sincerely appreciate all the support staff at IGH, too numerous to name here, and other support personnel in the communities visited for their tremendous contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASFV |

African swine fever virus |

| ASF |

African swine fever |

| JEV |

Japanese encephalitis virus |

| JE |

Japanese encephalitis |

| NHREC |

National Health Research Ethics Committee |

| AUCC |

Animal Use and Care Committee |

| RT-qPCR |

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic acid |

| IgG |

Immunoglobulin G |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| OD |

Optical density |

References

- Chieloka, O.S.; Gloria, M.O. Outbreak Investigation of African Swine Fever in Ebonyi State Nigeria,30th April to July, 6th , 2021. PAMJ-OH 2022, 7. [CrossRef]

- Awosanya EJ; Olugasa BO; Gimba FI; Sabri MY; Ogundipe GA Detection of African Swine Fever Virus in Pigs in Southwest Nigeria. Veterinary World 2021, 14(7).

- Orji, S. Worst Outbreak Ever’: Nearly a Million Pigs Culled in Nigeria Due to Swine Fever. The Guardian 2020.

- Odemuyiwa, S.O.; Adebayo, I.A.; Ammerlaan, W.; Ajuwape, A.T.P.; Alaka, O.O.; Oyedele, O.I.; Soyelu, K.O.; Olaleye, D.O.; Otesile, E.B.; Muller, C.P. An Outbreak of African Swine Fever in Nigeria: Virus Isolation and Molecular Characterization of the VP72 Gene of a First Isolate from West Africa. Virus Genes 2000, 20, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji AJ,; Luka PD; Atai RB; Olubade TA; Hambolu DA; Ogunleye MA; Muwanika VB; Masembe C First-Time Presence of African Swine Fever Virus Genotype II in Nigeria. Microbiology Resource Announcements. 2021, 10(26), 10–128.

- Burke, D.S.; Leake, C.J. Japanese Encephalitis. In Arboviruses; CRC Press, 2019; pp. 63–92.

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund Japanese Encephalitis (JE) Reported Cases and Incidence; WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form on Immunization (JRF); 2025.

- Campbell, G.; Hills, S.; Fischer, M.; Jacobson, J.; Hoke, C.; Hombach, J.; Marfin, A.; Solomon, T.; Tsai, T.; Tsui, V.; et al. Estimated Global Incidence of Japanese Encephalitis: Bull World Health Org 2011, 89, 766–774. [CrossRef]

- Simon-Loriere, E.; Faye, O.; Prot, M.; Casademont, I.; Fall, G.; Fernandez-Garcia, M.D.; Diagne, M.M.; Kipela, J.-M.; Fall, I.S.; Holmes, E.C.; et al. Autochthonous Japanese Encephalitis with Yellow Fever Coinfection in Africa. N Engl J Med 2017, 376, 1483–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiki-Raji, C.O.; Amza, A.; Adebiyi, A.I. Serological Screening for Porcine Japanese B Encephalitis Virus among Commercial Pigs in an Urban Abattoir in Southwest Nigeria. Tropical Veterinarian 2021, 39, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Adeleke, R. Serological Investigation of Japanese Encephalitis Virus Infection in Commercially Reared Pigs, Southwestern Nigeria. Veterinaria Italiana 2024, 59, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owolodun, O.A.; Yakubu, B.; Antiabong, J.F.; Ogedengbe, M.E.; Luka, P.D.; John Audu, B.; Ekong, P.S.; Shamaki, D. Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of African Swine Fever Outbreaks in Nigeria, 2002-2007: Dynamics of ASF in Nigeria. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2010, 57, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasina, F.O.; Agbaje, M.; Ajani, F.L.; Talabi, O.A.; Lazarus, D.D.; Gallardo, C.; Thompson, P.N.; Bastos, A.D.S. Risk Factors for Farm-Level African Swine Fever Infection in Major Pig-Producing Areas in Nigeria, 1997–2011. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2012, 107, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosanya, E.J.; Olugasa, B.; Ogundipe, G.; Grohn, Y.T. Sero-Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with African Swine Fever on Pig Farms in Southwest Nigeria. BMC Vet Res 2015, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asambe, A.; Sackey, A.K.B.; Tekdek, L.B. Sanitary Measures in Piggeries, Awareness, and Risk Factors of African Swine Fever in Benue State, Nigeria. Trop Anim Health Prod 2019, 51, 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bora, M.; Bora, D.P.; Manu, M.; Barman, N.N.; Dutta, L.J.; Kumar, P.P.; Poovathikkal, S.; Suresh, K.P.; Nimmanapalli, R. Assessment of Risk Factors of African Swine Fever in India: Perspectives on Future Outbreaks and Control Strategies. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, H.; Dups-Bergmann, J.; Schulz, K.; Probst, C.; Zani, L.; Fischer, M.; Gethmann, J.; Denzin, N.; Blome, S.; Conraths, F.J.; et al. Identification of Risk Factors for African Swine Fever: A Systematic Review. Viruses 2022, 14, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos AD; Penrith ML; Cruciere C; Edrich JL; Hutchings G; Roger F; Couacy-Hymann EG; Thomson G Genotyping Field Strains of African Swine Fever Virus by Partial P72 Gene Characterisation. Archives of virology 2003, 148, 693–706. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, C.; Mwaengo, D.M.; Macharia, J.M.; Arias, M.; Taracha, E.A.; Soler, A.; Okoth, E.; Martín, E.; Kasiti, J.; Bishop, R.P. Enhanced Discrimination of African Swine Fever Virus Isolates through Nucleotide Sequencing of the P54, P72, and pB602L (CVR) Genes. Virus Genes 2009, 38, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapagain, S.; Pal Singh, P.; Le, K.; Safronetz, D.; Wood, H.; Karniychuk, U. Japanese Encephalitis Virus Persists in the Human Reproductive Epithelium and Porcine Reproductive Tissues. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022, 16, e0010656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloum, A.; Van Schalkwyk, A.; Chernyshev, R.; Igolkin, A.; Heath, L.; Sprygin, A. A Guide to Molecular Characterization of Genotype II African Swine Fever Virus: Essential and Alternative Genome Markers. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njau, E.P.; Domelevo Entfellner, J.-B.; Machuka, E.M.; Bochere, E.N.; Cleaveland, S.; Shirima, G.M.; Kusiluka, L.J.; Upton, C.; Bishop, R.P.; Pelle, R.; et al. The First Genotype II African Swine Fever Virus Isolated in Africa Provides Insight into the Current Eurasian Pandemic. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 13081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuanualsuwan, S.; Songkasupa, T.; Boonpornprasert, P.; Suwankitwat, N.; Lohlamoh, W.; Nuengjamnong, C. Persistence of African Swine Fever Virus on Porous and Non-Porous Fomites at Environmental Temperatures. Porc Health Manag 2022, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederwerder, M.C.; Stoian, A.M.M.; Rowland, R.R.R.; Dritz, S.S.; Petrovan, V.; Constance, L.A.; Gebhardt, J.T.; Olcha, M.; Jones, C.K.; Woodworth, J.C.; et al. Infectious Dose of African Swine Fever Virus When Consumed Naturally in Liquid or Feed. Emerg Infect Dis 2019, 25, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costard, S.; Zagmutt, F.J.; Porphyre, T.; Pfeiffer, D.U. Small-Scale Pig Farmers’ Behavior, Silent Release of African Swine Fever Virus and Consequences for Disease Spread. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 17074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costard, S.; Wieland, B.; De Glanville, W.; Jori, F.; Rowlands, R.; Vosloo, W.; Roger, F.; Pfeiffer, D.U.; Dixon, L.K. African Swine Fever: How Can Global Spread Be Prevented? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2009, 364, 2683–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrith, M.-L.; Vosloo, W.; Jori, F.; Bastos, A.D.S. African Swine Fever Virus Eradication in Africa. Virus Research 2013, 173, 228–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesehinwa, A.O.K.; Aribido, S.O.; Oyediji, G.O.; Obiniyi, A.A. Production Strategies for Coping with the Demand and Supply of Pork in Some Peri-Urban Areas of Southwestern Nigeria. Livestock Research for Rural Development 2003, 15, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Udeze, A.O.; Odebisi-Omokanye, M.B. Sero-Evidence of Silent Japanese Encephalitis Virus Infection among Inhabitants of Ilorin, North-Central Nigeria: A Call for Active Surveillance. Journal of Immunoassay and Immunochemistry 2022, 43, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, K.L.; Horton, D.L.; Johnson, N.; Li, L.; Barrett, A.D.T.; Smith, D.J.; Galbraith, S.E.; Solomon, T.; Fooks, A.R. Flavivirus-Induced Antibody Cross-Reactivity. Journal of General Virology 2011, 92, 2821–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisher, C.H.; Karabatsos, N.; Dalrymple, J.M.; Shope, R.E.; Porterfield, J.S.; Westaway, E.G.; Brandt, W.E. Antigenic Relationships between Flaviviruses as Determined by Cross-Neutralization Tests with Polyclonal Antisera. Journal of General Virology 1989, 70, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, A.N.; Ploss, A. Emerging Mosquito-Borne Flaviviruses. mBio 2024, 15, e02946-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Notes

| 1 |

Response counts: holding capacity, location, and farm manager n = 35; state n = 37; abattoirs n = 2 |

| 2 |

Response counts: general hygiene protocols and personnel hygiene n= 36; equipment hygiene and disinfectants n= 37 |

| 3 |

Response counts: prophylactic practices n = 37; carcass disposal n = 29 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).