Submitted:

10 May 2023

Posted:

11 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental design

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Artificial wounding of potato tubers

2.3.2. Determination of dry rot disease index and loss of fresh weight in wounded potato tubers.

2.3.3. Microscopic observation of SPP and lignin deposition at the wound site of potato tubers

2.3.4. Sample collection

2.3.5. Determination of enzyme activities in SPP and lignin anabolism

2.3.6. Determination of metabolic contents of Suberization

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

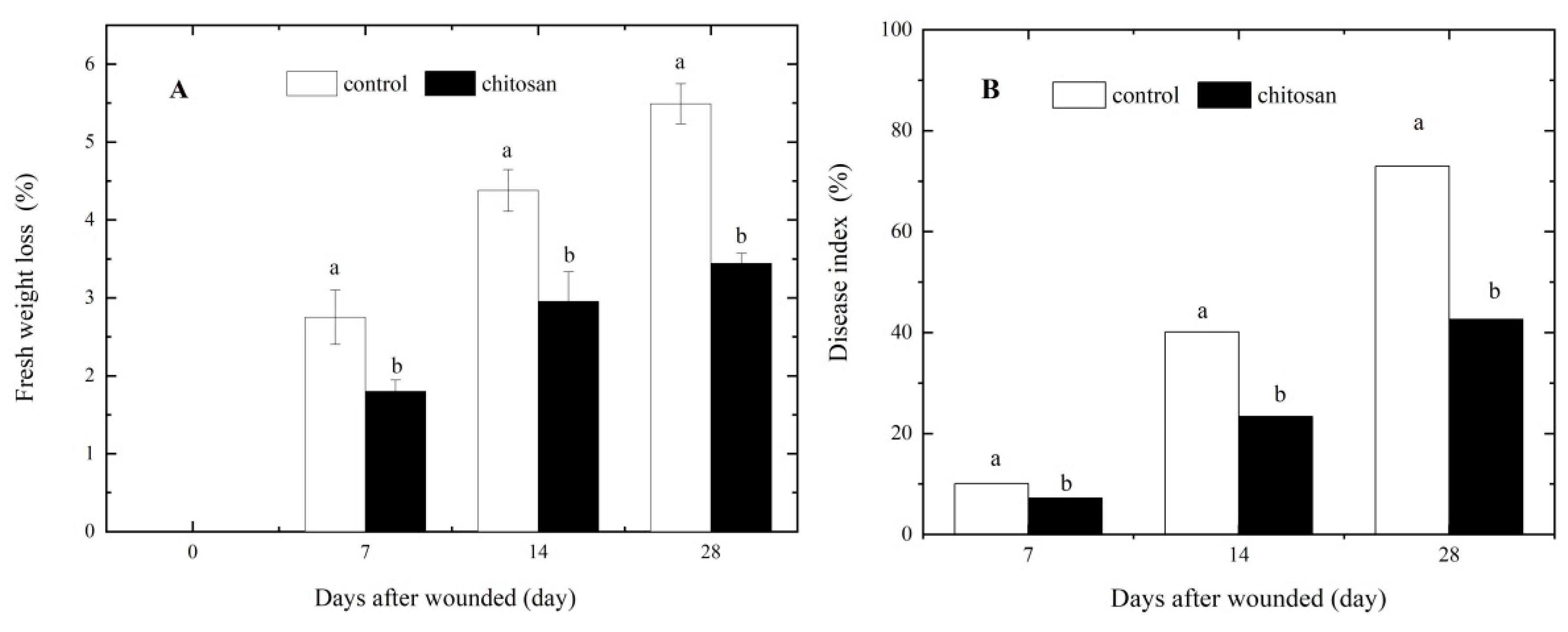

3.1. Foliar spraying of chitosan treatment reduces the effects of wounding on tuber fresh weight loss and dry rot development

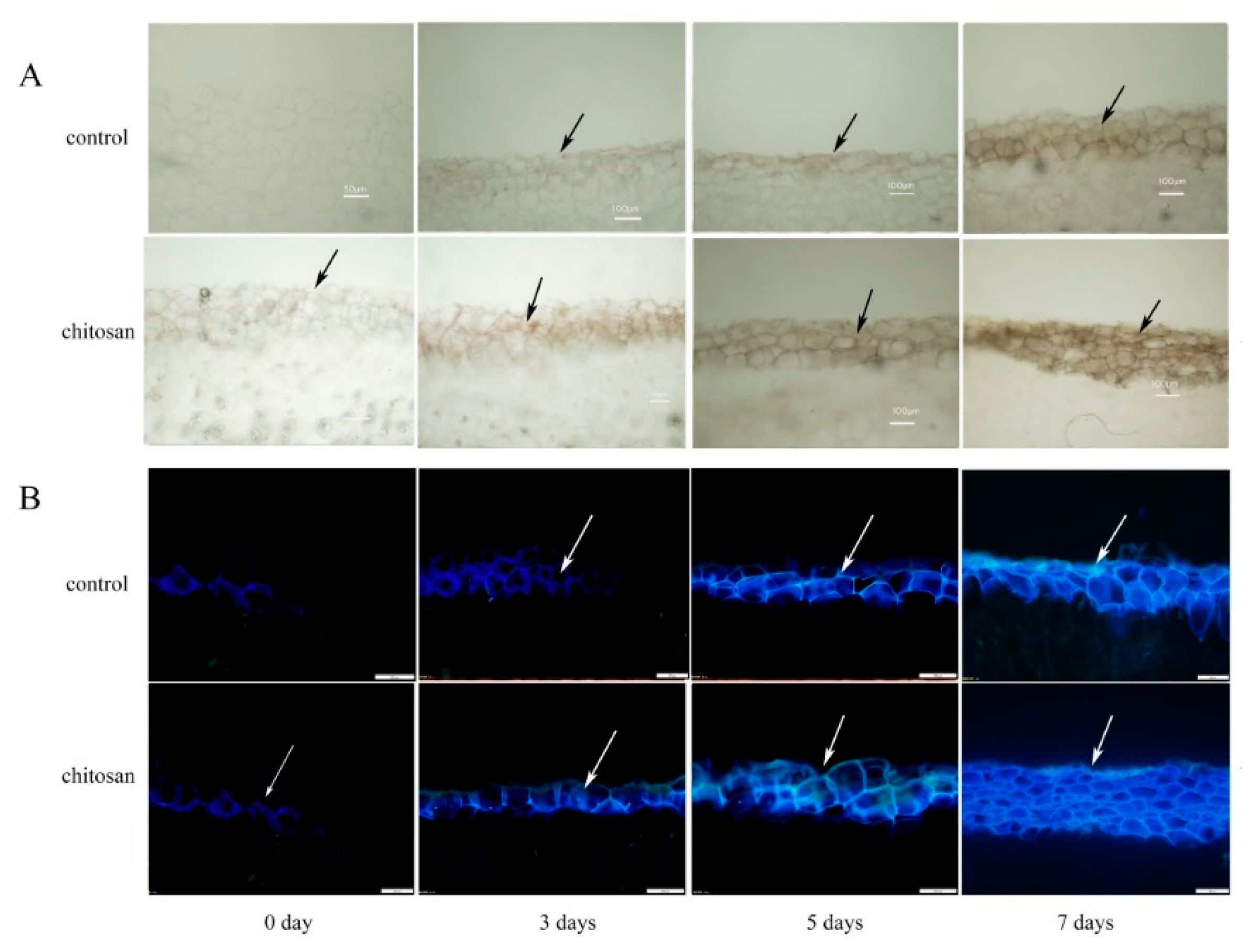

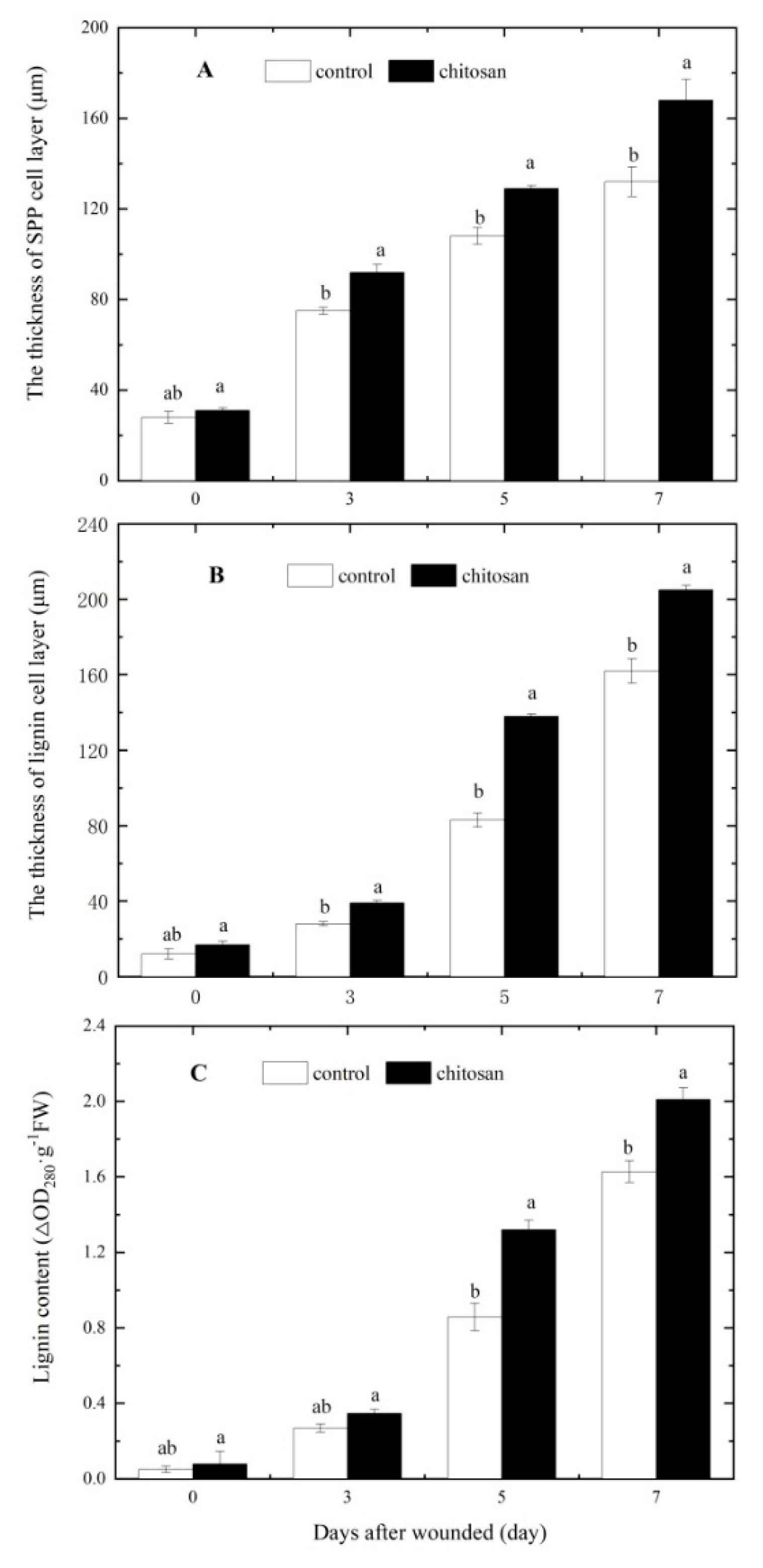

3.2. Effect of foliar spraying of chitosan on lignin and SPP accumulation at the wound site of potato tuber

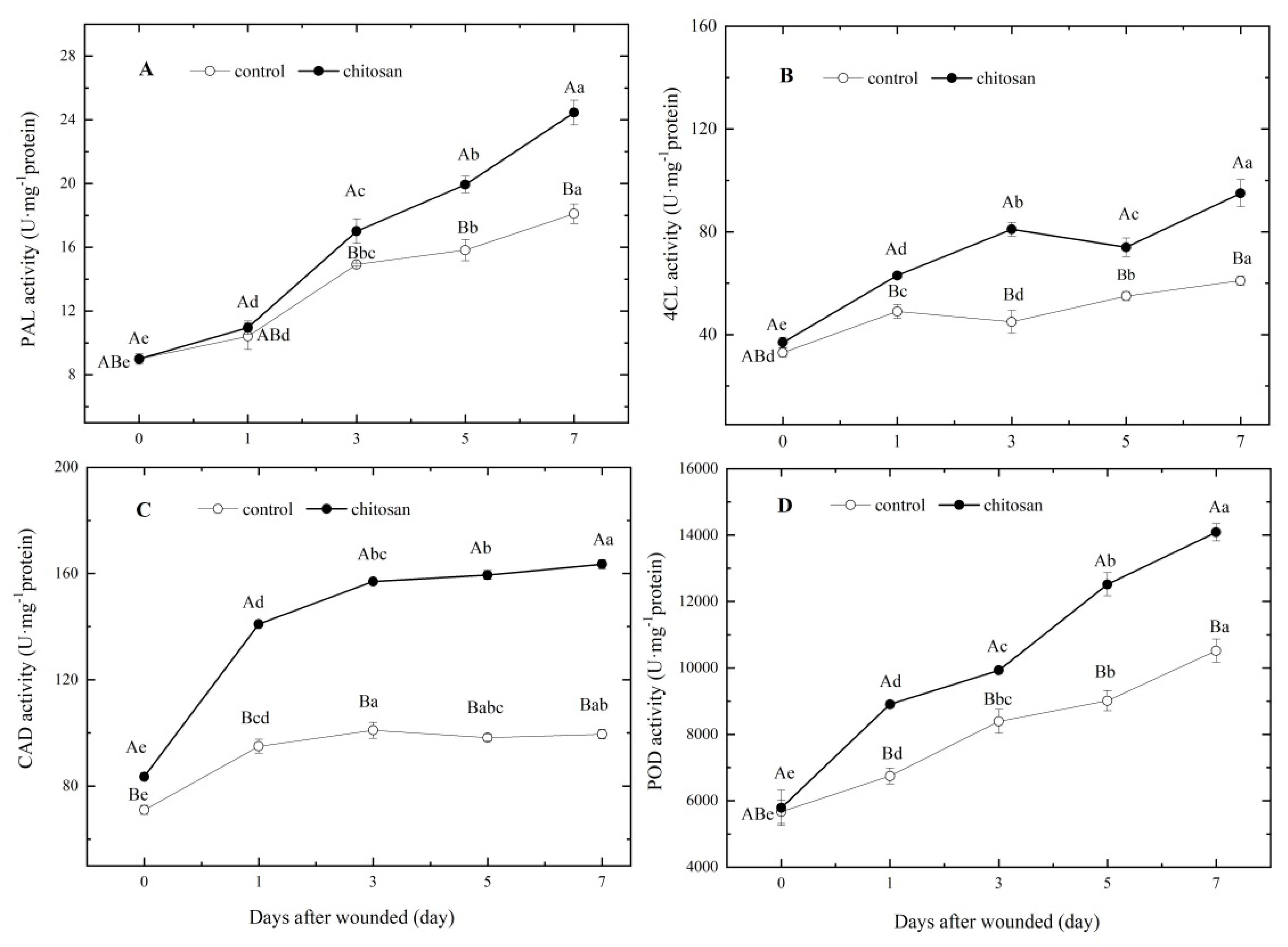

3.3. Effect of foliar spraying of chitosan on key enzyme activities of SPP and lignin anabolism during wound-induced suberization

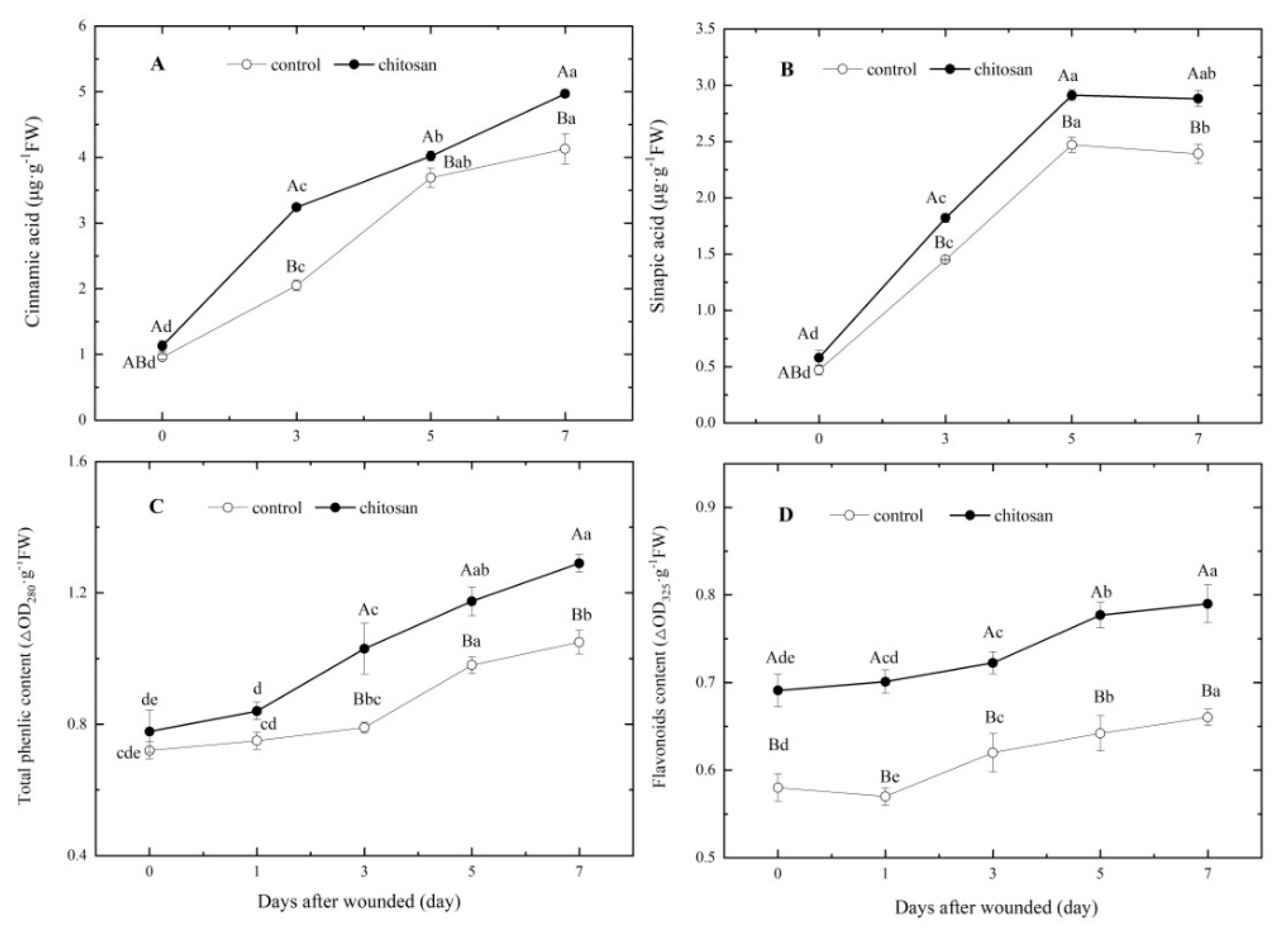

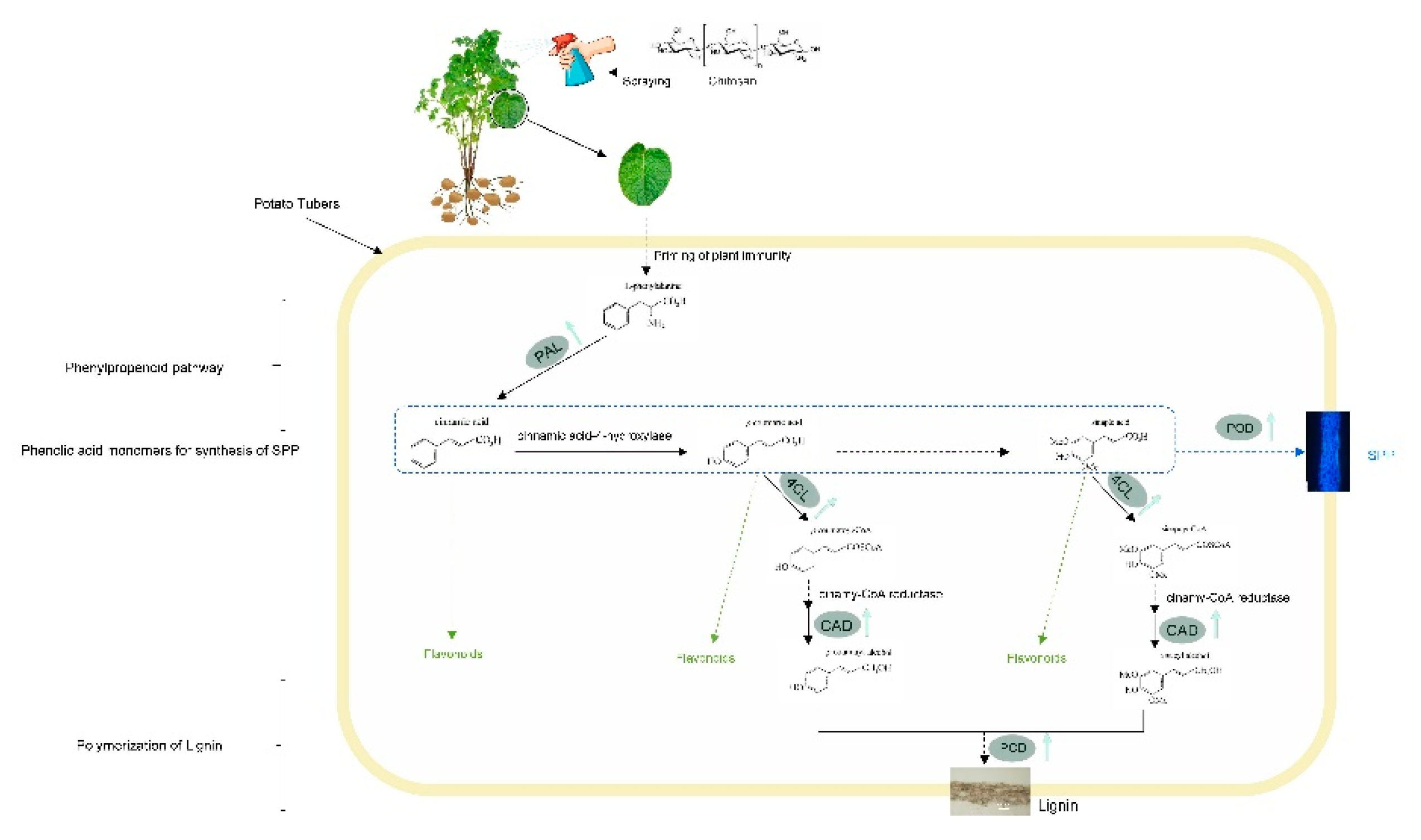

3.4. Effects of the foliar spraying of chitosan on the contents of phenolic acid monomers, flavonoids and total phenols in tubers during wound-induced suberization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, Z.; Sun, H.; Cheng, Q.; Zhu, M. Classification and integration of storage and transportation engineering technologies in potato producing areas of China. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2017, 18, 710–718. [Google Scholar]

- Campilho, A.; Nieminen, K.; Ragni, L. The development of the periderm: the final frontier between a plant and its environment. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2020, 53, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Bhardwaj, V.; Kaur, K.; Kukreja, S.; Goutam, U. Potato Periderm is the First Layer of Defence against Biotic and Abiotic Stresses: a Review. Potato Res. 2020, 64, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Ren, X.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R. Characterization of Fusarium spp. Causing Potato Dry Rot in China and Susceptibility Evaluation of Chinese Potato Germplasm to the Pathogen. Potato Res. 2012, 55, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulai, E.C.; Neubauer, J.D. Wound-induced suberization genes are differentially expressed, spatially and temporally, during closing layer and wound periderm formation. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014, 90, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Jiang, H.; Bi, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Gong, D.; Wei, Y.; Li, Z.; Prusky, D. Comparison of wound healing abilities of four major cultivars of potato tubers in China. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mokadem, A.Z.; Alnaggar, A.E.-A.M.; Mancy, A.G.; Sofy, A.R.; Sofy, M.R.; Mohamed, A.K.S.H.; Abou Ghazala, M.M.A.; El-Zabalawy, K.M.; Salem, N.F.G.; Elnosary, M.E.; Agha, M.S. Foliar application of chitosan and phosphorus alleviate the potato virus Y-induced resistance by modulation of the reactive oxygen species, antioxidant defense system activity and gene expression in potato. Agronomy. 2022, 12, e3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Meng, X.; Meng, J.; Khan, I.H.; Dai, L.; Khan, A.; An, X.; Zhang, J.; Huq, T.; Ni, Y. Chitosan as A Preservative for Fruits and Vegetables: A Review on Chemistry and Antimicrobial Properties. J. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2019, 4, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Castro, S.P. Application of Chitosan in Fresh and Minimally Processed Fruits and Vegetables. Academic Press. 2016, 67–113. [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi, G.; Sanzani, S.M.; Bi, Y.; Tian, S.; Martínez, P.G.; Alkan, N. Induced resistance to control postharvest decay of fruit and vegetables. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 122, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Zhu, L.; Xi, L.; Guo, L.; Wang, H. An antimicrobial agent prepared by N-succinyl chitosan immobilized lysozyme and its application in strawberry preservation. Food Control. 2019, 108, 106829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, G.; Moumni, M. Chitosan and other edible coatings to extend shelf life, manage postharvest decay, and reduce loss and waste of fresh fruits and vegetables. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 78, 102834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshaies, M.; Lamari, N.; Ng, C.K.Y.; Ward, P.; Doohan, F.M. The impact of chitosan on the early metabolomic response of wheat to infection by Fusarium graminearum. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, E.O.; Shoala, T.; Attia, A.M.F.; Badr, O.A.M.; Mahmoud, S.Y.M.; Farrag, E.S.H.; EL-Fiki, I.A.I. Chitosan and nano-chitosan for management of Harpophora maydis: Approaches for investigating antifungal activity, pathogenicity, maize-resistant lines, and molecular diagnosis of plant infection. J. Fungi. 2022, 8, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.G.; Ru, P.; Yao, S.; Deng, L.; Zeng, K. Pichia membranaefaciens combined with chitosan treatment induces resistance to anthracnose in Citrus fruit. Food Sci. 2019, 40, 228–237. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Xue, S.; Xu, X.; Wang, B.; Zheng, X.; Li, B.; Xie, P.; Bi, Y.; Prusky, D. Preharvest multiple sprays with chitosan accelerate the deposition of suberin poly phenolic at wound sites of harvested muskmelons. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesney, M.S. Growth responses and lignin production in cell suspensions of Pinuse elliottii 'elicited' by chitin, chitosan or mycelium of Cronartium quercum f. sp. fusiforme. Plant Cell Tissue Org. 1989, 19, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notsu, S.; Saito, N.; Kosaki, H.; Inui, H.; Hirano, S. Stimulation of Phenylalanine Ammonia-lyase Activity and Lignification in Rice Callus Treated with Chitin, Chitosan, and Their Derivatives. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1994, 58, 552–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; Bi, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Prusky, D. Preharvest multiple fungicide stroby sprays promote wound healing of harvested potato tubers by activating phenylpropanoid metabolism. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 171, 111328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zong, Y.; Liang, W.; Kong, R.; Gong, D.; Han, Y.; Li, Y.; Bi, Y.; Prusky, D. Sorbitol immersion accelerates the deposition of suberin polyphenolic and lignin at wounds of potato tubers by activating phenylpropanoid metabolism. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 297, 110971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruz, J.; Novák, O.; Strnad, M. Rapid analysis of phenolic acids in beverages by UPLC–MS/MS. Food Chem. 2008, 111, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Shu, C.; Zhao, H.; Fan, X.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Preharvest chitosan oligochitosan and salicylic acid treatments enhance phenol metabolism and maintain the postharvest quality of apricots (Prunus armeniaca L.). Sci. Hortic. 2020, 267, 109334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkeblia, N.; Tennant, D.P.F.; Jawandha, S.K.; Gill, P.S. Preharvest and harvest factors influencing the postharvest quality of tropical and subtropical fruits. Postharvest Biology and Technology of Tropical and Subtropical Fruits; Yahia, E.M., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Sawston, Cambridge CB22 3HJ, UK, 2011; 142e, pp. 112-141. [Google Scholar]

- Wójcik, P. Effects of preharvest sprays of iodine, selenium and calcium on apple biofortification and their quality and storability. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0282873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, T.; Mustafa, G.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Shao, Z. Quality Improvement of Tomato Fruits by Preharvest Application of Chitosan Oligosaccharide. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, E.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, W.; Chen, X.; Li, L. Chitosan Reduces Damages of Strawberry Seedlings under High-Temperature and High-Light Stress. Agronomy 2023, 13, e517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulai, E.C.; Campbell, L.G.; Fugate, K.K.; McCue, K.F. Biological differences that distinguish the 2 major stages of wound healing in potato tubers. Plant Signal. Behav. 2016, 11, e1256531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.Q.; Lin, H.X. Contribution of phenylpropanoid metabolism to plant development and plant–environment interactions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 180–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, T. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Mol. Plant. 2010, 3, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernards, M.A.; Razem, F.A. The poly(phenolic) domain of potato suberin: a non-lignin cell wall bio-polymer. Phytochemistry 2000, 57, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yang, R.; Wang, Q.; Wang, B.; Prusky, D. Sodium silicate promotes wound healing by inducing the deposition of suberin polyphenolic and lignin in potato tubers. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 942022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhou, Y.; Ming, J.; Yao, S.; Zeng, K. Wound healing in citrus fruit is promoted by chitosan and Pichia membranaefaciens as a resistance mechanism against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 145, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Kan, C.; Wan, C.; Chen, C.; Chen, M.; Chen, J. Quality and biochemical changes of navel orange fruits during storage as affected by cinnamaldehyde -chitosan coating. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 239, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.-H.; Guo, W.-L.; Guo, R.-Z.; Li, X.-Y.; Xue, Z.-H. Effects of Chitosan, Calcium Chloride, and Pullulan Coating Treatments on Antioxidant Activity in Pear cv. “Huang guan” During Storage. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 7, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Lin, L.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, X. Application of Chitosan-Lignosulfonate Composite Coating Film in Grape Preservation and Study on the Difference in Metabolites in Fruit Wine. Coatings 2022, 12, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zheng, J.; Huang, C.; Zhao, X.; Chen, H.; Sun, Z. Effects of Combined Aqueous Chlorine Dioxide and Chitosan Coatings on Microbial Growth and Quality Maintenance of Fresh-Cut Bamboo Shoots (Phyllostachys praecox f. prevernalis.) During Storage. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2015, 8, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahlbrock, K.; Grisebach, H. Enzymic Controls in the Biosynthesis of Lignin and Flavonoids. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1979, 30, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascaes, M.M.; Guilhon, G.M.S.P.; Zoghbi, M.d.G.; Andrade, E.H.A.; Santos, L.S.; da Silva, J.K.R.; Uetanabaro, A.P.T.; Araújo, I.S. Flavonoids, antioxidant potential and antimicrobial activity of Myrcia rufipila mcvaugh leaves (myrtaceae). Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 1717–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górniak, I.; Bartoszewski, R.; Króliczewski, J. Comprehensive review of antimicrobial activities of plant flavonoids. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 241–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).