Submitted:

09 May 2023

Posted:

10 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

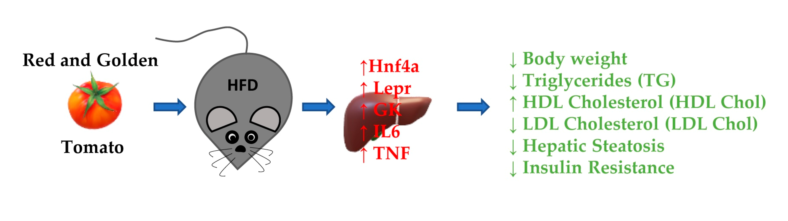

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

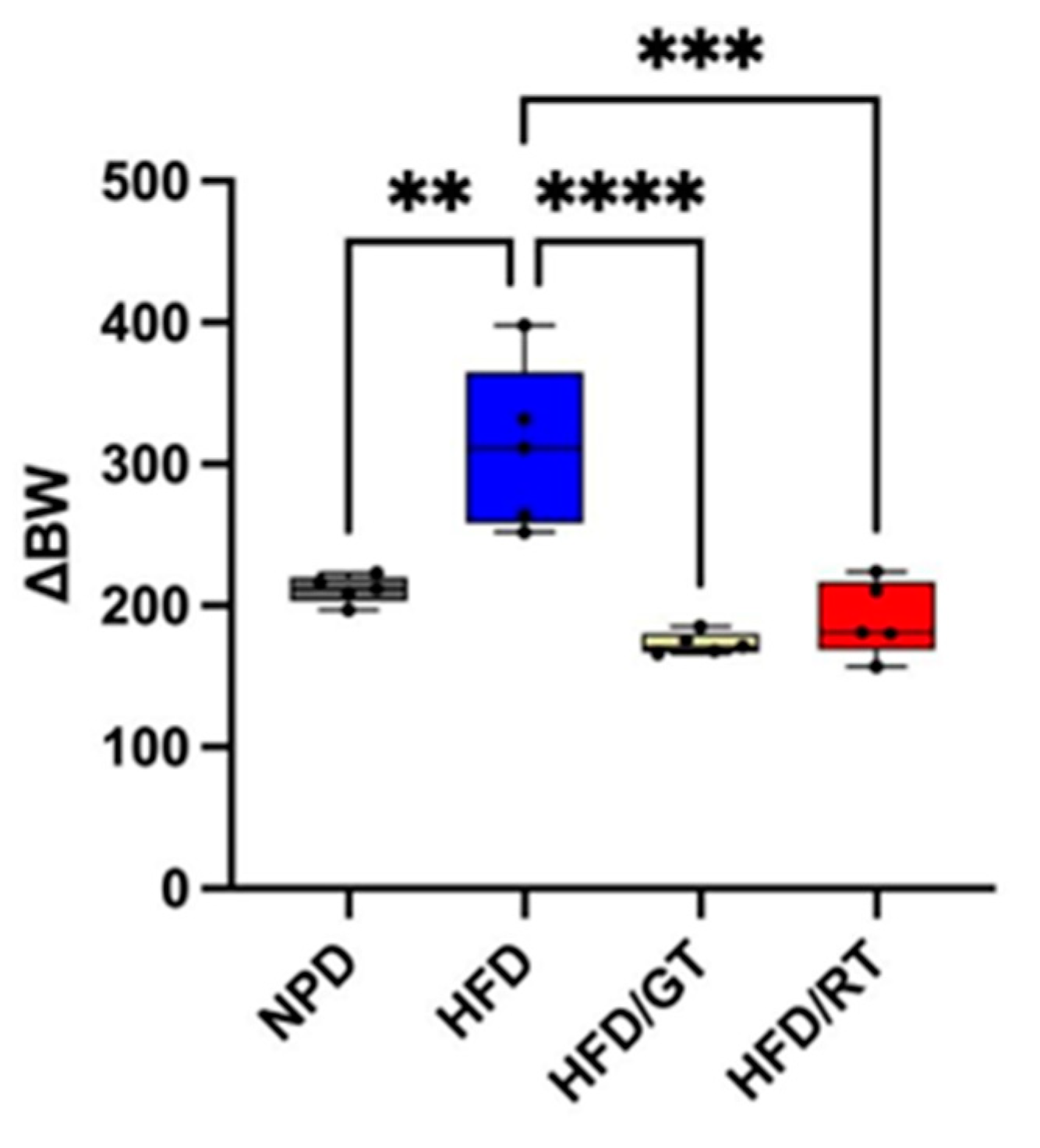

2.1. Effects of Red Tomato and Glolden Tomato Diet on Body Weight

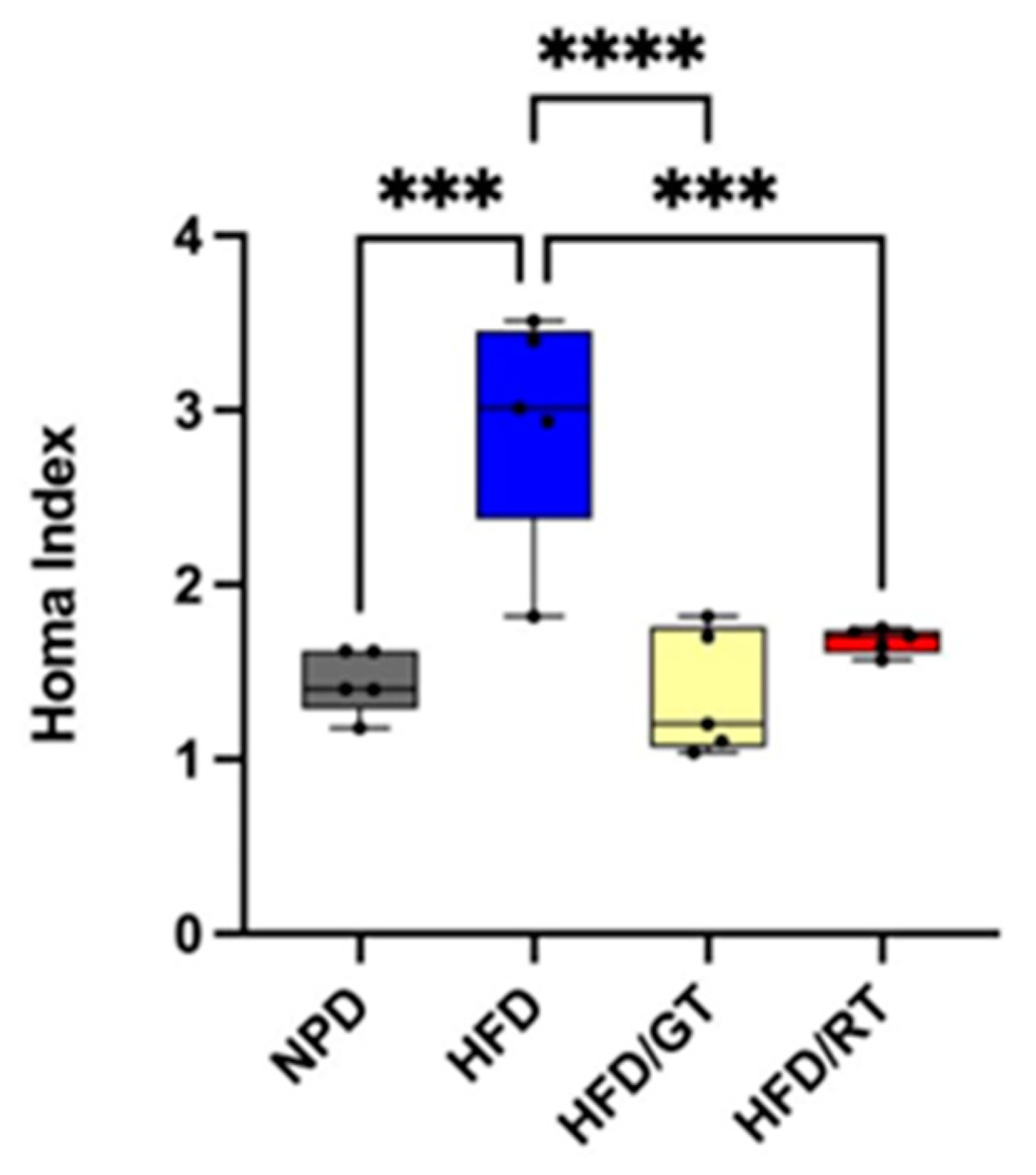

2.2. Effects of Red Tomato and Golden Tomato Diet on Metabolic Profile

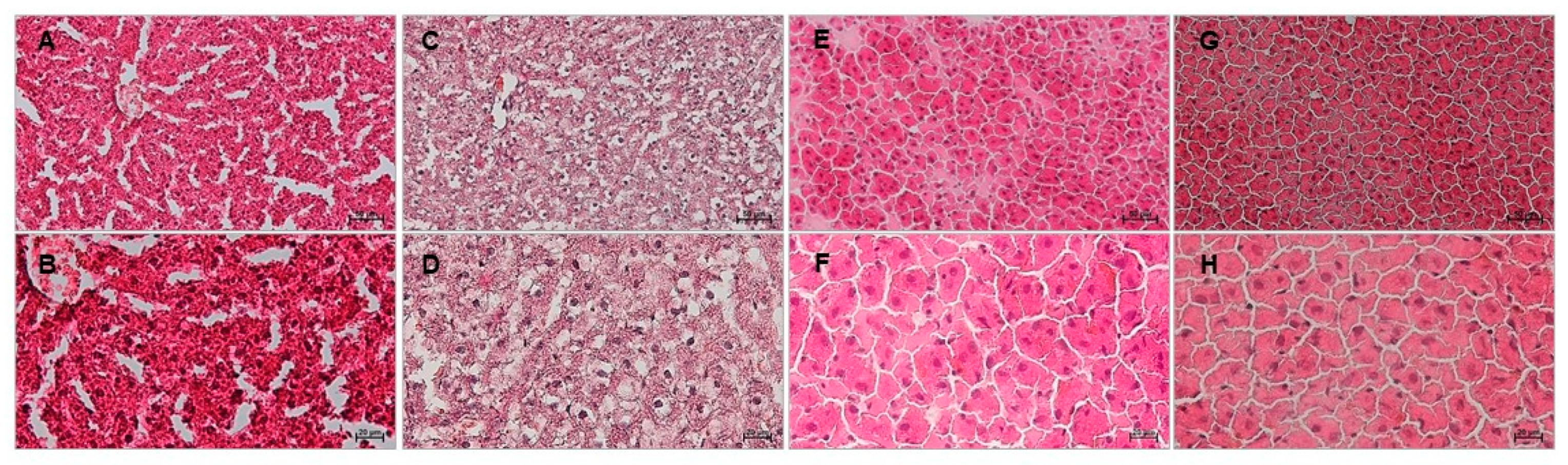

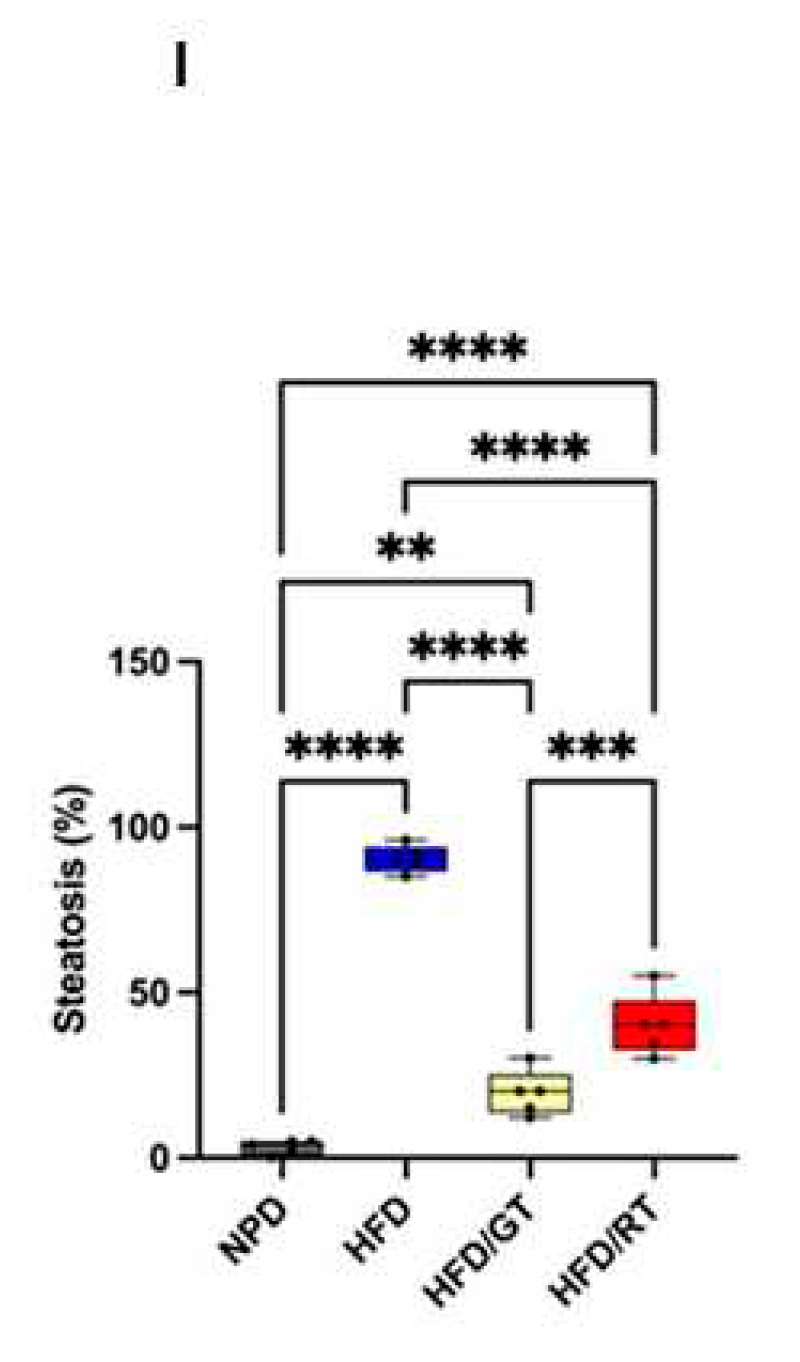

2.3. Effects of Red Tomato and Golden Tomato Diet on Hepatic Steatosis

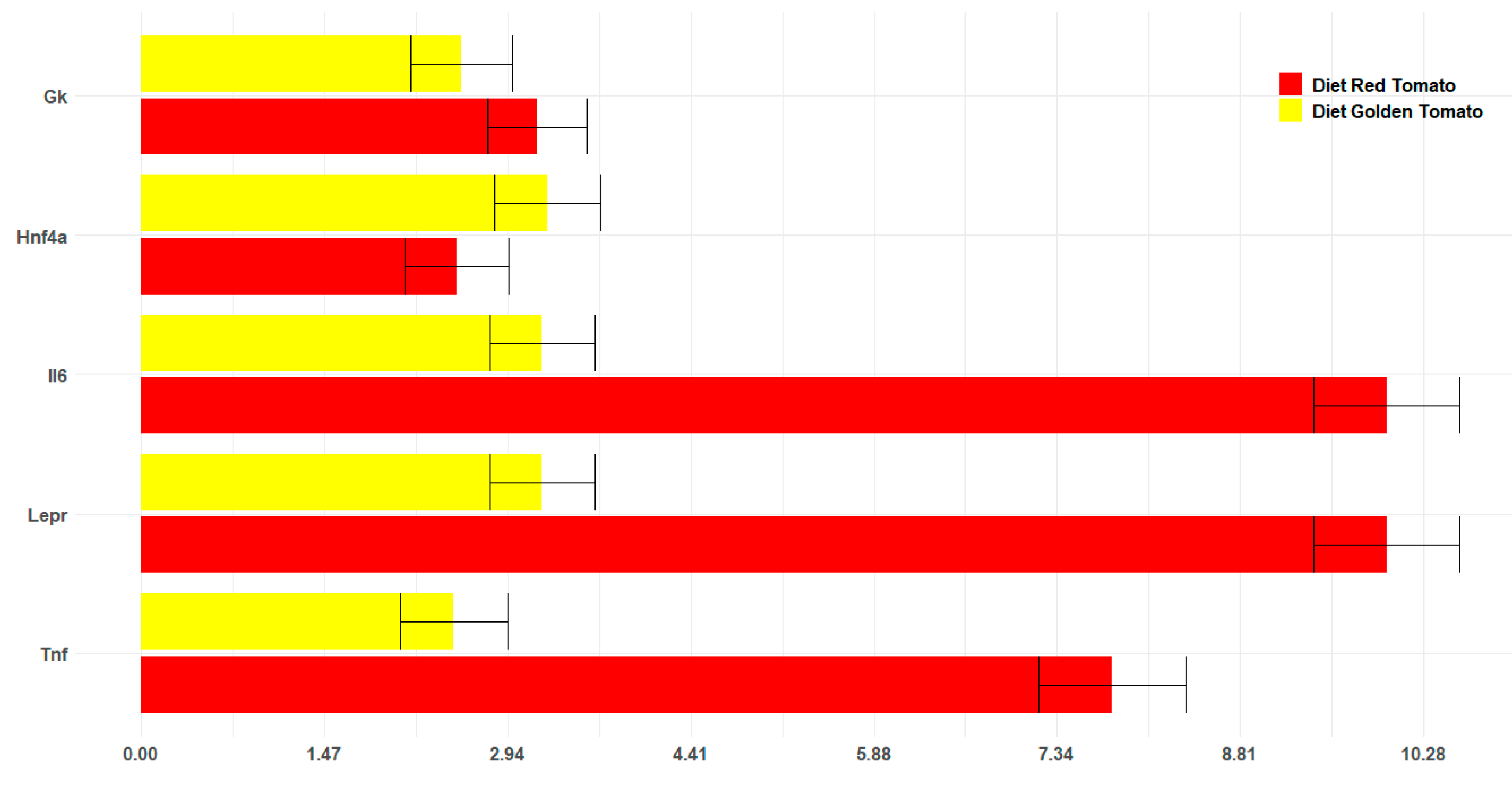

2.5. Effects of Red and Golden Tomatoes Intake on Metabolic, Adipokine, and Inflammatory Signalling

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

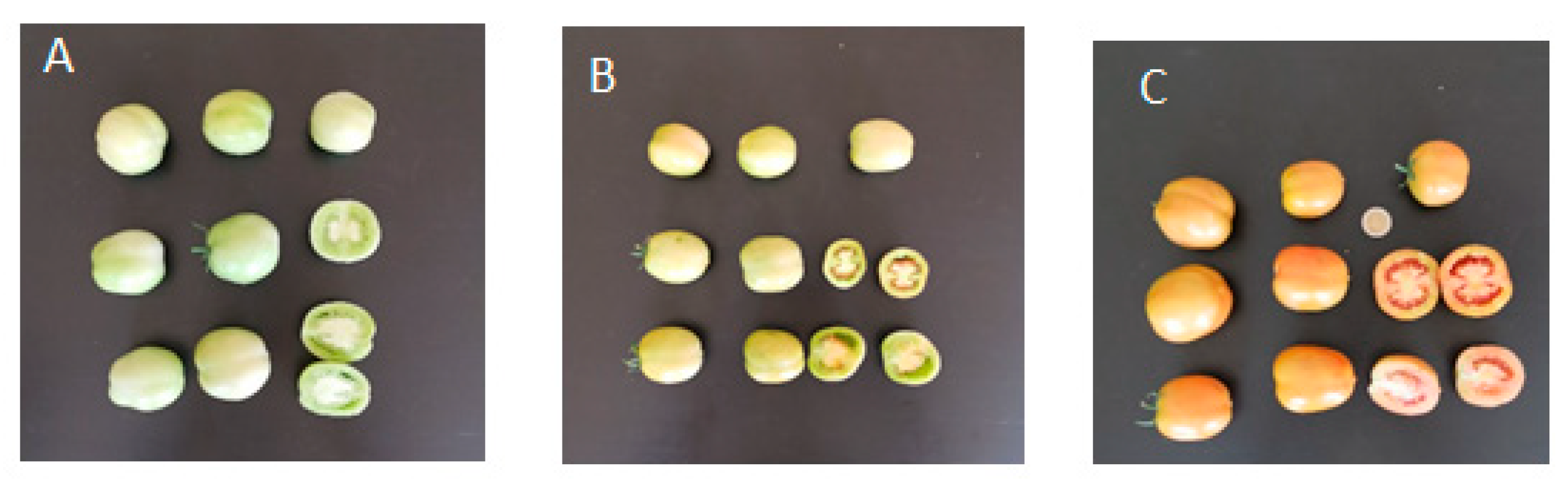

4.1. Preparation and Treatment of Golden and Red Tomatoes

4.1.1. Tomatoes Solutions for Oral Administration

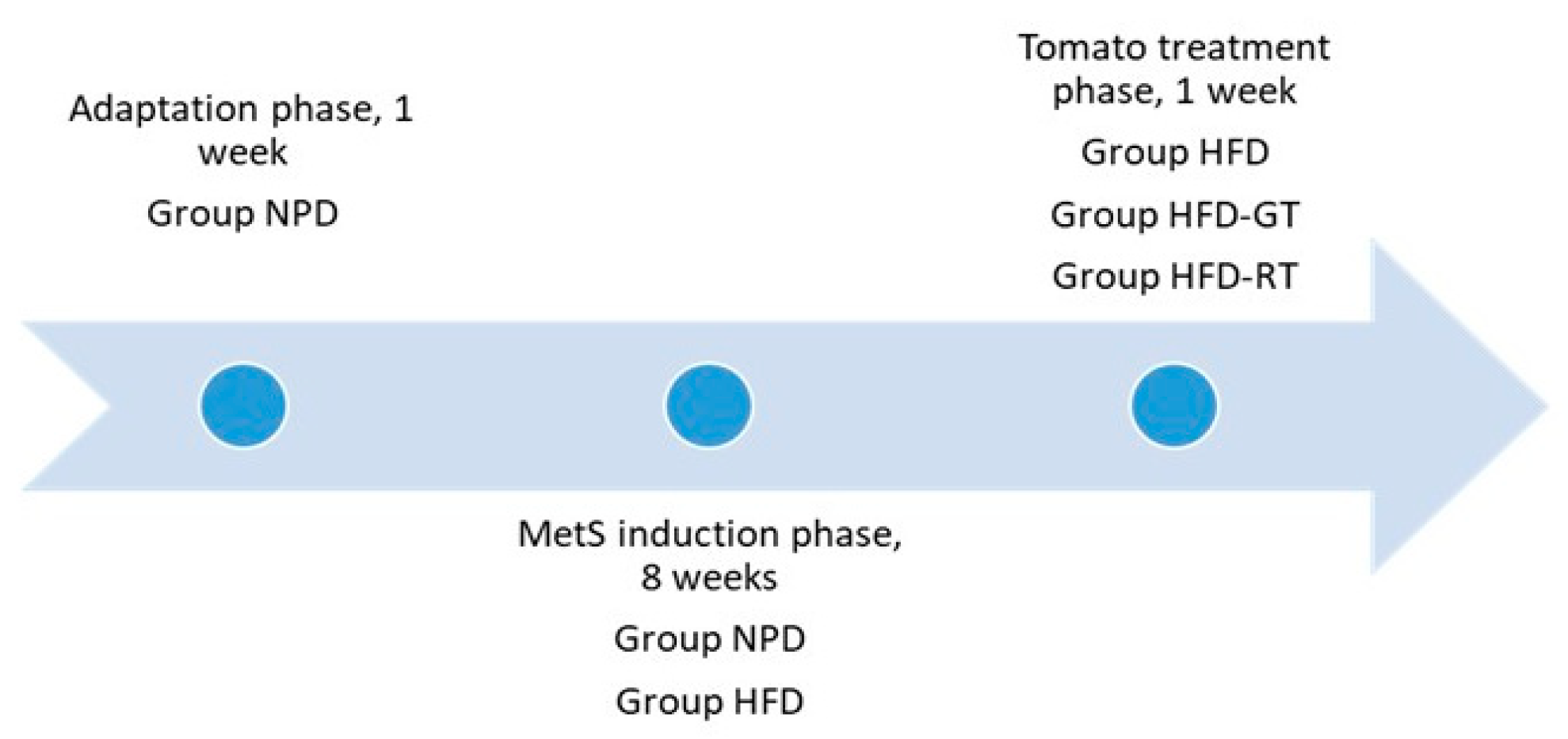

4.2. Animals and Experimental Groups

4.3. Diet Composition

4.4. Body Weight Gain

4.5. Glucose and Lipid Homeostasis Assays

4.6. Determination of Hepatic Steatosis

4.7. RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR Microarray

4.8. Statistical Analisys

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Bugianesi, E.; Gish, R.G.; Lammert, F.; Tilg, H.; Nguyen, M.H.; Sarin, S.K.; Fabrellas, N.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Fan, J.G.; et al. Global Multi-Stakeholder Endorsement of the MAFLD Definition. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 7, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotter, T.G.; Rinella, M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease 2020: The State of the Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1851–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WJG-2Antioxidant in NAFLD.

- Di Majo, D.; Cacciabaudo, F.; Accardi, G.; Gambino, G.; Giglia, G.; Ferraro, G.; Candore, G.; Sardo, P. Ketogenic and Modified Mediterranean Diet as a Tool to Counteract Neuroinflammation in Multiple Sclerosis: Nutritional Suggestions. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-González, I.; García-Alonso, J.; Periago, M.J. Bioactive Compounds of Tomato: Cancer Chemopreventive Effects and Influence on the Transcriptome in Hepatocytes. J Funct Foods 2018, 42, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, P.; Joyce, S.A.; O’toole, P.W.; O’connor, E.M. Dietary Fibre Modulates the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.Y.; Sina, A.A.I.; Khandker, S.S.; Neesa, L.; Tanvir, E.M.; Kabir, A.; Khalil, M.I.; Gan, S.H. Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds in Tomatoes and Their Impact on Human Health and Disease: A Review. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenni, S.; Hammou, H.; Astier, J.; Bonnet, L.; Karkeni, E.; Couturier, C.; Tourniaire, F.; Landrier, J.F. Lycopene and Tomato Powder Supplementation Similarly Inhibit High-Fat Diet Induced Obesity, Inflammatory Response, and Associated Metabolic Disorders. Mol Nutr Food Res 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Guo, M.H.; Hai, X. Hepatoprotective and Antioxidant Effects of Lycopene on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Rat. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 10180–10188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Gao, M.; Liu, D. Chlorogenic Acid Improves High Fat Diet-Induced Hepatic Steatosis and Insulin Resistance in Mice. Pharm Res 2015, 32, 1200–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, G.C.; Larter, C.Z. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: From Steatosis to Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2006, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, A.; Svegliati-Baroni, G.; Ortolani, A.; Cucco, M.; Dalla Riva, G. V.; Giannini, E.G.; Piscaglia, F.; Rapaccini, G.; Di Marco, M.; Caturelli, E.; et al. Epidemiological Trends and Trajectories of MAFLD-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma 2002-2033: The ITA.LI.CA Database. Gut 2023, 72, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.J.; Cheung, R.; Ahmed, A. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Is the Most Rapidly Growing Indication for Liver Transplantation in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the U.S. Hepatology 2014, 59, 2188–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R. Evolution of Inflammation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: The Multiple Parallel Hits Hypothesis. Hepatology 2010, 52, 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francque, S.M.; Marchesini, G.; Kautz, A.; Walmsley, M.; Dorner, R.; Lazarus, J. V.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Hallsworth, K.; Busetto, L.; Frühbeck, G.; et al. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Patient Guideline. JHEP Reports 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Cusi, K. New Diagnostic and Treatment Approaches in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). Ann Med 2009, 41, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiray, E.; Tulek, Y.; Yilmaz, Y. Degradation Kinetics of Lycopene, β-Carotene and Ascorbic Acid in Tomatoes during Hot Air Drying. LWT 2013, 50, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Hu, S.; Park, Y.K.; Lee, J.Y. Health Benefits of Carotenoids: A Role of Carotenoids in the Prevention of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Prev Nutr Food Sci 2019, 24, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okechukwu, G.N.; Nweke, O.B.; Nwafor, A.J.; Godson, A.G.; Kenneth, E.U.; Ibegbu, A.O. Beta (β)-Carotene-Induced Effects on the Hepato-Biochemical Parameters in Wistar Rats Fed Dietary Fats; 2019; Vol. 12;

- Marcelino, G.; Machate, D.J.; Freitas, K. de C.; Hiane, P.A.; Maldonade, I.R.; Pott, A.; Asato, M.A.; Candido, C.J.; Guimarães, R. de C.A. β-Carotene: Preventive Role for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.; Lawler, T.; Mares, J. Dietary Carotenoids and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease among US Adults, NHANES 2003–2014. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baybutt, R.C.; Molteni, A. Dietary B-Carotene Protects Lung and Liver Parenchyma of Rats Treated with Monocrotaline; 1999; Vol. 137;

- Elvira-Torales, L.I.; García-Alonso, J.; Periago-Castón, M.J. Nutritional Importance of Carotenoids and Their Effect on Liver Health: A Review. Antioxidants 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palozza, P.; Catalano, A.; Simone, R.E.; Mele, M.C.; Cittadini, A. Effect of Lycopene and Tomato Products on Cholesterol Metabolism. Ann Nutr Metab 2012, 61, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Lee, C.H.; Moon, S.S.; Kim, E.; Kim, C.T.; Kim, B.H.; Bok, S.H.; Jeong, T.S. Naringenin Derivatives as Anti-Atherogenic Agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2003, 13, 3901–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzo, P.; Ascenzi, P.; Bulzomi, P.; Marino, M. The Nutritional Flavanone Naringenin Triggers Antiestrogenic Effects by Regulating Estrogen Receptor α-Palmitoylation. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 2567–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulvihill, E.E.; Allister, E.M.; Sutherland, B.G.; Telford, D.E.; Sawyez, C.G.; Edwards, J.Y.; Markle, J.M.; Hegele, R.A.; Huff, M.W. Naringenin Prevents Dyslipidemia, Apolipoprotein B Overproduction, and Hyperinsulinemia in LDL Receptor-Null Mice with Diet-Induced Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2009, 58, 2198–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Pozzo, E.; Costa, B.; Cavallini, C.; Testai, L.; Martelli, A.; Calderone, V.; Martini, C. The Citrus Flavanone Naringenin Protects Myocardial Cells against Age-Associated Damage. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeini, F.; Namkhah, Z.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Tutunchi, H.; Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M.J. A Comprehensive Systematic Review of the Effects of Naringenin, a Citrus-Derived Flavonoid, on Risk Factors for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Advances in Nutrition 2021, 12, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olthof, M.R. ; Peter, ^; Hollman, C.H.; Katan, M.B. Human Nutrition and Metabolism Chlorogenic Acid and Caffeic Acid Are Absorbed in Humans^; 2001; Vol. 131.

- Strack, D.; Gross, W. Properties and Activity Changes of Chlorogenic Acid:Glucaric Acid Caffeoyltransferase From Tomato (Lycopersicon Esculentum); 1990; Vol. 92;

- Wan, C.W.; Wong, C.N.Y.; Pin, W.K.; Wong, M.H.Y.; Kwok, C.Y.; Chan, R.Y.K.; Yu, P.H.F.; Chan, S.W. Chlorogenic Acid Exhibits Cholesterol Lowering and Fatty Liver Attenuating Properties by Up-Regulating the Gene Expression of PPAR-α in Hypercholesterolemic Rats Induced with a High-Cholesterol Diet. Phytotherapy Research 2013, 27, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naveed, M.; Hejazi, V.; Abbas, M.; Kamboh, A.A.; Khan, G.J.; Shumzaid, M.; Ahmad, F.; Babazadeh, D.; FangFang, X.; Modarresi-Ghazani, F.; et al. Chlorogenic Acid (CGA): A Pharmacological Review and Call for Further Research. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2018, 97, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, A.S.; Jeon, S.M.; Kim, M.J.; Yeo, J.; Seo, K. Il; Choi, M.S.; Lee, M.K. Chlorogenic Acid Exhibits Anti-Obesity Property and Improves Lipid Metabolism in High-Fat Diet-Induced-Obese Mice. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2010, 48, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Sahin, K.; Bilen, H.; Bahcecioglu, I.H.; Bilir, B.; Ashraf, S.; Halazun, K.J.; Kucuk, O. Carotenoids and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2015, 4, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Subhan, N.; Rahman, M.M.; Uddin, S.J.; Reza, H.M.; Sarker, S.D. Effect of Citrus Flavonoids, Naringin and Naringenin, on Metabolic Syndrome and Their Mechanisms of Action. Advances in Nutrition 2014, 5, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Chen, G.; Pan, M.; Zhang, J.; He, W.; Liu, Y.; Nian, X.; Sheng, L.; Xu, B. High Fat Diet-Induced Oxidative Stress Blocks Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4α and Leads to Hepatic Steatosis in Mice. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 4770–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zalzala, M.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Yin, L.; Zhang, Y. A Metabolic Stress-Inducible MiR-34a-HNF4α Pathway Regulates Lipid and Lipoprotein Metabolism. Nat Commun 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Park, S.H.; Ahn, J.; Hong, S.P.; Lee, E.; Jang, Y.J.; Ha, T.Y.; Huh, Y.H.; Ha, S.Y.; Jeon, T. Il; et al. Mir214-3p and Hnf4a/Hnf4α Reciprocally Regulate Ulk1 Expression and Autophagy in Nonalcoholic Hepatic Steatosis. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2415–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman, S.; Muzumdar, R.H.; Atzmon, G.; Ma, X.; Yang, X.; Einstein, F.H.; Barzilai, N. Resistance to Leptin Action Is the Major Determinant of Hepatic Triglyceride Accumulation in Vivo. The FASEB Journal 2007, 21, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, A.; Moreno, N.R.; Balaguer, I.; Méndez-Giménez, L.; Becerril, S.; Catalán, V.; Gómez-Ambrosi, J.; Portincasa, P.; Calamita, G.; Soveral, G.; et al. Leptin Administration Restores the Altered Adipose and Hepatic Expression of Aquaglyceroporins Improving the Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver of Ob/Ob Mice. Sci Rep 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulet, M.A.; Macarulla, M.T.; Portillo, M.P.; Noel-Suberville, C.; Higueret, P.; Martínez, J.A. Lipid and Glucose Utilization in Hypercholesterolemic Rats Fed a Diet Containing Heated Chickpea (Cicer Aretinum L.): A Potential Functional Food. International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research 1999, 69, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phachonpai, W.; Muchimapura, S.; Tong-Un, T.; Wattanathorn, J.; Thukhammee, W.; Thipkaew, C.; Sripanidkulchai, B.; Wannanon, P. ACUTE TOXICITY STUDY OF TOMATO POMACE EXTRACT IN RODENT. Online J Biol Sci 2013, 13, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aborehab, N.M.; El Bishbishy, M.H.; Waly, N.E. Resistin Mediates Tomato and Broccoli Extract Effects on Glucose Homeostasis in High Fat Diet-Induced Obesity in Rats. BMC Complement Altern Med 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Majo, D.; Sardo, P.; Giglia, G.; Di Liberto, V.; Zummo, F.P.; Zizzo, M.G.; Caldara, G.F.; Rappa, F.; Intili, G.; van Dijk, R.M.; et al. Correlation of Metabolic Syndrome with Redox Homeostasis Biomarkers: Evidence from High-Fat Diet Model in Wistar Rats. Antioxidants 2022, 12, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Correa, E.; González-Pérez, I.; Clavel-Pérez, P.I.; Contreras-Vargas, Y.; Carvajal, K. Biochemical and Nutritional Overview of Diet-Induced Metabolic Syndrome Models in Rats: What Is the Best Choice? Nutr Diabetes 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Hu, H.; Tang, N.; Zhang, C.; Liang, W.; Wang, M. Smad3 Specific Inhibitor, Naringenin, Decreases the Expression of Extracellular Matrix Induced by TGF-Β1 in Cultured Rat Hepatic Stellate Cells. Pharm Res 2006, 23, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Experimental Groups | TG | T Chol | LDL Chol | HDL Chol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPD | 80.42± 16.08 | 75.44±5.96 | 31.74±9.72 | 26.37±0.58 |

| HFD | 125.72± 12.83## | 93.55±4.49# | 52.56±6.00# | 16.12±2.62# |

| HFD/GT | 99.17± 7.31* | 110.49±12.47*# | 34.32±7.72** | 56.56±9.14***## |

| HFD/RT | 85.70±16.67** | 98.58±9.60# | 37.76±4.13* | 39.20±4.95**# |

| Experimental Groups | AUC | Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|

| NPD | 333.75± 38.65 | 103.34± 11.17 |

| HFD | 492.79±17.30## | 150.85± 35.41# |

| HFD/GT | 412.00± 18.76 **## | 108.53± 11.67* |

| HFD/RT | 448.40 ±41.24 | 126.91±9.60 |

| Component of diet | Pellet NPD (PF1609) | Pellet HFD (PF4215) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy (Kcal/Kg) | 3947 | 5500–6000 |

| Fat Total (g/100 g) | 3,5 | 60 |

| SFA (g/60 g) | 0,7 | 30 |

| MUFA (g/60 g | 0,8 | 23 |

| PUFA (g/60 g) | 2 | 7 |

| Crude Protein (g/100 g) | 22 | 23 |

| Carbohydrates (Starch g/100 g) | 35,18 | 38 |

| Fiber (g/100 g) | 4,5 | 5 |

| Ash (g/100 g) | 7,5 | 5,5 |

| Vitamin A (IU) | 8,4 | 19,5 |

| Vitamin D3 (IU) | 1260 | 2100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).