Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

29 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

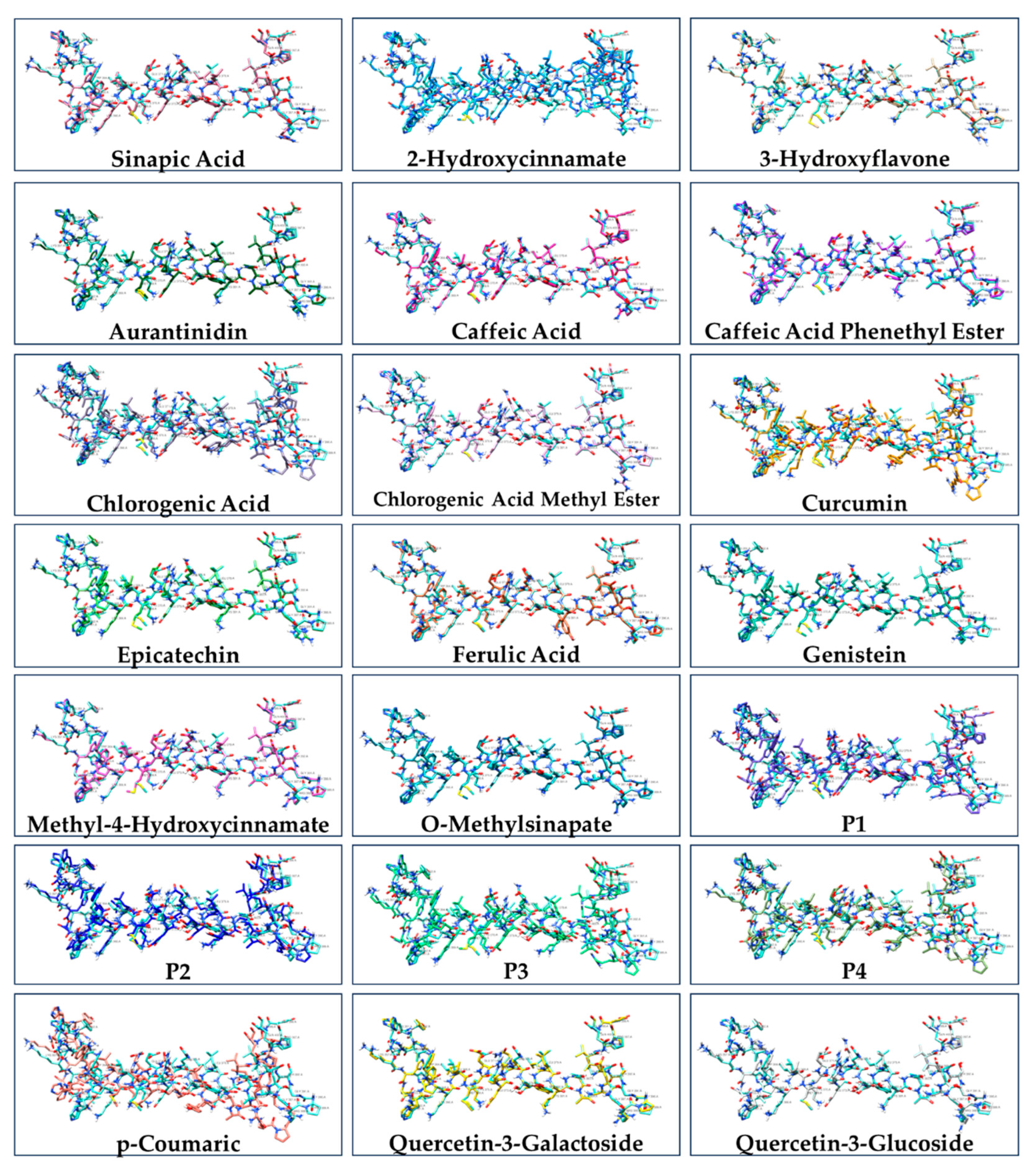

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a metabolic disorder described by the deposition of triglycerides in the liver, which primarily occurs due to insulin resistance and obesity. Thyroid hormone receptor alpha (THRA) is involved in metabolic pathways that promote lipolysis, which can prevent the accumulation of liver fat. As a possible treatment for NAFLD, this in silico study examines the binding interactions between THRA and polyphenols and flavonoids present in fruits and vegetables. Including caffeic acid, curcumin, and chlorogenic acid, the binding affinities of the natural substances to THRA were found comparable to the hormone T3, boosting the THRA-TRAP220 complex, promoting fatty acid oxidation, while decreasing lipid accumulation in the liver.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J Hepatol 2015, 62, S47–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.L.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Rinella, M.; Sanyal, A.J. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med 2018, 24, 908–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gofton, C.; Upendran, Y.; Zheng, M.H.; George, J. MAFLD: How is it different from NAFLD? Clin Mol Hepatol 2023, 29, S17–s31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouwels, S.; Sakran, N.; Graham, Y.; Leal, A.; Pintar, T.; Yang, W.; Kassir, R.; Singhal, R.; Mahawar, K.; Ramnarain, D. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a review of pathophysiology, clinical management and effects of weight loss. BMC Endocr Disord 2022, 22, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z.; Anstee, Q.M.; Marietti, M.; Hardy, T.; Henry, L.; Eslam, M.; George, J.; Bugianesi, E. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 15, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Yin, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Pathogenesis and Natural Products for Prevention and Treatment. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.L.; Ng, C.H.; Huang, D.Q.; Chan, K.E.; Tan, D.J.; Lim, W.H.; Yang, J.D.; Tan, E.; Muthiah, M.D. Global incidence and prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2023, 29, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Golabi, P.; Paik, J.M.; Henry, A.; Van Dongen, C.; Henry, L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2023, 77, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2023, 78, 1966–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, E.E.; Finn, P.D.; Stebbins, J.W.; Hou, J.; Ito, B.R.; van Poelje, P.D.; Linemeyer, D.L.; Erion, M.D. Reduction of hepatic steatosis in rats and mice after treatment with a liver-targeted thyroid hormone receptor agonist. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2009, 49, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenmakers, N. Genetic Causes of Congenital Hypothyroidism. Encyclopedia of Endocrine Diseases 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Real, J.M.; Corella, D.; Goumidi, L.; Mercader, J.M.; Valdés, S.; Rojo Martínez, G.; Ortega, F.; Martinez-Larrad, M.T.; Gómez-Zumaquero, J.M.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; et al. Thyroid hormone receptor alpha gene variants increase the risk of developing obesity and show gene-diet interactions. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013, 37, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Cevallos, P.; Murúa-Beltrán Gall, S.; Uribe, M.; Chávez-Tapia, N.C. Understanding the Relationship between Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Thyroid Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Xie, H.; Shan, H.; Zheng, Z.; Li, G.; Li, M.; Hong, L. Development of Thyroid Hormones and Synthetic Thyromimetics in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, F.; Rochira, A.; Gnoni, A.; Siculella, L. Action of Thyroid Hormones, T3 and T2, on Hepatic Fatty Acids: Differences in Metabolic Effects and Molecular Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paisdzior, S.; Knierim, E.; Kleinau, G.; Biebermann, H.; Krude, H.; Straussberg, R.; Schuelke, M. A New Mechanism in THRA Resistance: The First Disease-Associated Variant Leading to an Increased Inhibitory Function of THRA2. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Li, G.; Lin, Y.P.; Barrero, M.J.; Ge, K.; Roeder, R.G.; Wei, L.N. Thyroid hormone-induced juxtaposition of regulatory elements/factors and chromatin remodeling of Crabp1 dependent on MED1/TRAP220. Mol Cell 2005, 19, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, M.; Bertoni, D.; Magana, P.; Paramval, U.; Pidruchna, I.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Tsenkov, M.; Nair, S.; Mirdita, M.; Yeo, J.; et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database in 2024: providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seok, C.; Baek, M.; Steinegger, M.; Park, H.; Lee, G.R.; Won, J. Accurate protein structure prediction: what comes next? BIODESIGN 2021, 9, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, L.; Park, S.; Seok, C. GalaxyWater-wKGB: Prediction of Water Positions on Protein Structure Using wKGB Statistical Potential. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2021, 61, 2283–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Thiessen, P.A.; Bolton, E.E.; Chen, J.; Fu, G.; Gindulyte, A.; Han, L.; He, J.; He, S.; Shoemaker, B.A.; et al. PubChem Substance and Compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, D1202–D1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. Journal of Cheminformatics 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.R.; Seok, C. Galaxy7TM: flexible GPCR-ligand docking by structure refinement. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of computational chemistry 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoorah, A.W.; Devignes, M.-D.; Smaïl-Tabbone, M.; Ritchie, D.W. Protein docking using case-based reasoning. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2013, 81, 2150–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, B.J.; Gahbauer, S.; Luttens, A.; Lyu, J.; Webb, C.M.; Stein, R.M.; Fink, E.A.; Balius, T.E.; Carlsson, J.; Irwin, J.J.; et al. A practical guide to large-scale docking. Nature Protocols 2021, 16, 4799–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, J.; Park, H.; Seok, C. GalaxyTBM: template-based modeling by building a reliable core and refining unreliable local regions. BMC Bioinformatics 2012, 13, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugnon, M.; Röhrig, U.F.; Goullieux, M.; Perez, M.A.S.; Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissDock 2024: major enhancements for small-molecule docking with Attracting Cavities and AutoDock Vina. Nucleic Acids Research 2024, 52, W324–W332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosdidier, A.; Zoete, V.; Michielin, O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Research 2011, 39, W270–W277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of computational chemistry 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-García, B.; Pons, C.; Fernández-Recio, J. pyDockWEB: a web server for rigid-body protein-protein docking using electrostatics and desolvation scoring. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2013, 29, 1698–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korlepara, D.B.; Vasavi, C.S.; Jeurkar, S.; Pal, P.K.; Roy, S.; Mehta, S.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, V.; Muvva, C.; Sridharan, B.; et al. PLAS-5k: Dataset of Protein-Ligand Affinities from Molecular Dynamics for Machine Learning Applications. Scientific Data 2022, 9, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, A.E.; Assaf, H.K.; Hassan, H.A.; Shimizu, K.; Elshaier, Y.A.M.M. An in silico perception for newly isolated flavonoids from peach fruit as privileged avenue for a countermeasure outbreak of COVID-19. RSC Advances 2020, 10, 29983–29998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, K.; Blessinger, S.; Bailey, N.T.; Scaife, R.; Liu, G.; Khambu, B. Therapeutic regulation of autophagy in hepatic metabolism. Acta Pharm Sin B 2022, 12, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Gu, Y.; Liang, J.; Ning, M.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, H.; Yang, Y.; Leng, Y.; Zhou, B. Discovery of Highly Potent and Selective Thyroid Hormone Receptor β Agonists for the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. J Med Chem 2023, 66, 3284–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jornayvaz, F.R.; Lee, H.Y.; Jurczak, M.J.; Alves, T.C.; Guebre-Egziabher, F.; Guigni, B.A.; Zhang, D.; Samuel, V.T.; Silva, J.E.; Shulman, G.I. Thyroid hormone receptor-α gene knockout mice are protected from diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Sinha, R.A.; Yen, P.M. Novel Transcriptional Mechanisms for Regulating Metabolism by Thyroid Hormone. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucchi, R. Thyroid Hormone Analogues: An Update. Thyroid 2020, 30, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q.; Sun, Q.; Fu, J. Dysfunction of autophagy in high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Autophagy 2024, 20, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.X.; Ito, M.; Fondell, J.D.; Fu, Z.Y.; Roeder, R.G. The TRAP220 component of a thyroid hormone receptor- associated protein (TRAP) coactivator complex interacts directly with nuclear receptors in a ligand-dependent fashion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 7939–7944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Qiu, F.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T. Effects of Natural Products on Fructose-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Z.; Chen, N.; Ma, N.; Li, M.R. Mechanism and Progress of Natural Products in the Treatment of NAFLD-Related Fibrosis. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meroni, M.; Longo, M.; Rustichelli, A.; Dongiovanni, P. Nutrition and Genetics in NAFLD: The Perfect Binomium. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yan, Y.; Wu, L.; Peng, J. Natural products in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): Novel lead discovery for drug development. Pharmacol Res 2023, 196, 106925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.P.; Ji, G. Natural Products on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Curr Drug Targets 2015, 16, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemel, M.B. Natural Products: New Hope for Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis? J Med Food 2019, 22, 1187–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.R.; Li, S.S.; Zheng, W.Q.; Ni, W.J.; Cai, M.; Liu, H.P. Targeted modulation of gut microbiota by traditional Chinese medicine and natural products for liver disease therapy. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1086078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Sullivan, M.A.; Chen, W.; Jing, X.; Yu, H.; Li, F.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Quercetin ameliorates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) via the promotion of AMPK-mediated hepatic mitophagy. J Nutr Biochem 2023, 120, 109414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Qin, Y.; Xin, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Feng, X. The great potential of flavonoids as candidate drugs for NAFLD. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 164, 114991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tan, W.; Liu, X.; Deng, L.; Huang, L.; Wang, X.; Gao, X. New insight and potential therapy for NAFLD: CYP2E1 and flavonoids. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 137, 111326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Changes in phenolics and antioxidant property of peach fruit during ripening and responses to 1-methylcyclopropene. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2015, 108, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, K.; Pao, S.; Dormedy, E.; Phillips, T.; Nikolich, G.; Li, L. Microbial evaluation of automated sorting systems in stone fruit packinghouses during peach packing. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2018, 285, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, P.; Sánchez, C.; Romero, J.; Alfaro, P.; Batlle, R.; Nerín, C. Development and application of an active package to increase the shelf-life of “Calanda peach”. NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL-IMCB UNIVERSITY OF NAPLES-DSA AND DIMP 2009.

- Abidi, W.; Akrimi, R. Phenotypic diversity of nutritional quality attributes and chilling injury symptoms in four early peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] cultivars grown in west central Tunisia. J Food Sci Technol 2022, 59, 3938–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drincovich, M.F. Identifying sources of metabolomic diversity and reconfiguration in peach fruit: taking notes for quality fruit improvement. FEBS Open Bio 2021, 11, 3211–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiggert, R.M.; Carle, R. Carotenoid deposition in plant and animal foods and its impact on bioavailability. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2017, 57, 1807–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bento, C.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Silva, B.; Silva, L.R. Peach (Prunus Persica): Phytochemicals and Health Benefits. Food Reviews International 2022, 38, 1703–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Lu, X.; Lei, F.; Sun, H.; Jiang, J.; Xing, D.; Du, L. Novel Effect of p-Coumaric Acid on Hepatic Lipolysis: Inhibition of Hepatic Lipid-Droplets. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prša, P.; Karademir, B.; Biçim, G.; Mahmoud, H.; Dahan, I.; Yalçın, A.S.; Mahajna, J.; Milisav, I. The potential use of natural products to negate hepatic, renal and neuronal toxicity induced by cancer therapeutics. Biochem Pharmacol 2020, 173, 113551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Sinapic Acid and Its Derivatives as Medicine in Oxidative Stress-Induced Diseases and Aging. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 3571614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pan, X.; Jiang, L.; Chu, Y.; Gao, S.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Luo, S.; Peng, C. The Biological Activity Mechanism of Chlorogenic Acid and Its Applications in Food Industry: A Review. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 943911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Gu, X.; Zhang, M.; Zu, X.; Shen, F.; Hou, X.; Hao, E.; Bai, G. Ferulic acid targets ACSL1 to ameliorate lipid metabolic disorders in db/db mice. Journal of Functional Foods 2022, 91, 105009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.N.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, R.Y.; Tang, W.Q.; Li, H.X.; Wang, S.M.; Li, J.; Chen, W.X.; Dong, J. Caffeic acid prevents non-alcoholic fatty liver disease induced by a high-fat diet through gut microbiota modulation in mice. Food Res Int 2021, 143, 110240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, A.S.; Jeon, S.M.; Kim, M.J.; Yeo, J.; Seo, K.I.; Choi, M.S.; Lee, M.K. Chlorogenic acid exhibits anti-obesity property and improves lipid metabolism in high-fat diet-induced-obese mice. Food Chem Toxicol 2010, 48, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, A.; Malik, M. Effects of curcumin in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can Liver J 2024, 7, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Jamal, A.; Jamil, D.A.; Al-Aubaidy, H.A. A systematic review exploring the mechanisms by which citrus bioflavonoid supplementation benefits blood glucose levels and metabolic complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2023, 17, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, J.; Liu, D.; Qin, C.; Yan, X.; Yang, L.; Xu, X.; Nie, G. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate or (−)-epicatechin enhances lipid catabolism and antioxidant defense in common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) fed a high-fat diet: Mechanistic insights from the AMPK/Sirt1/PGC-1α signaling pathway. Aquaculture 2024, 587, 740876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.W.; Seo, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Choi, J.W.; Cho, S.; Bae, J.Y.; Sohng, J.K.; Kim, S.O.; Kim, J.; Park, Y.I. 3-O-Glucosylation of quercetin enhances inhibitory effects on the adipocyte differentiation and lipogenesis. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 95, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čižmárová, B.; Tomečková, V.; Hubková, B.; Birková, A. Anti-obesity properties and mechanism of action of genistein. Food and Functional Food Science in Obesity 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.C.; Puhl, A.C.; Martínez, L.; Aparício, R.; Nascimento, A.S.; Figueira, A.C.; Nguyen, P.; Webb, P.; Skaf, M.S.; Polikarpov, I. Identification of a new hormone-binding site on the surface of thyroid hormone receptor. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md.) 2014, 28, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ligand | ΔG of binding to THRA (kcal/mol) | MMGBSA ΔG Binding Energy (Kcal/mol) of GalaxyWEB model | ΔG of THRA-liganded binding to TRAP220 (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-Coumaric | -7.948 | -7.381 | -812.60 |

| P4* | -17.269 | -17.953 | -694.70 |

| 2-Hydroxycinnamate | -5.804 | -6.201 | -669.50 |

| P2* | -12.110 | -11.995 | -665.11 |

| P1* | -10.579 | -11.003 | -654.50 |

| Caffeic Acid | -8.499 | -8.421 | -651.59 |

| Curcumin | -15.491 | -16.113 | -649.71 |

| Methyl-4-Hydroxycinnamate | -7.914 | -8.004 | -641.87 |

| Chlorogenic Acid | -13.616 | -13.412 | -627.93 |

| Chlorogenic Acid Methyl Ester | -15.155 | -14.950 | -617.52 |

| Quercetin-3-Galactoside | -17.321 | -17.117 | -599.31 |

| Epicatechin | -11.952 | -12.021 | -596.21 |

| Genistein | -9.671 | -10.423 | -595.28 |

| O-Methylsinapate | -9.628 | -9.527 | -588.62 |

| T3 | -13.388 | -13.216 | -582.45 |

| Quercetin-3-Glucoside | -15.370 | -15.444 | -576.29 |

| 3-Hydroxyflavone | -9.231 | -9.785 | -570.24 |

| Ferulic Acid | -8.980 | -9.075 | -563.35 |

| Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester | -12.300 | -11.889 | -562.89 |

| Sinapic Acid | -9.274 | -10.004 | -559.81 |

| Aurantinidin | -14.221 | -12.925 | -559.73 |

| P3* | -18.465 | -17.563 | -525.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).