1. Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is considered to be the liver manifestation of metabolic syndrome and is characterized by excessive lipid accumulation in liver [

1,

2]. It encompasses two subtypes: nonalcoholic simple fatty liver (NASFL), the non-progressive form of NAFLD, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which can progress to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver-related death [

3,

4,

5]. Nowadays, NAFLD has become the most common chronic liver disease and is threating 38% of the global population [

6]. Resmetirom, an oral thyroid hormone receptor-β agonist, was approved for the treatment of NASH (the more advanced subtype of NAFLD) in March 2024, which is the first, and only, approved drug for NAFLD [

7]. However, due to the complicated pathogenesis underlying NAFLD, it is still imperative to target other genes involved in lipid metabolism to develop inhibitors or agonists for the treatment of NAFLD [

8,

9].

Accumulating evidence indicates that cholesterol metabolism plays a key role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Excess cholesterol is preferentially stored in the liver to impair liver cells through multiple mechanisms and contributes to NAFLD progression [

10]. Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) is the crucial target mediating intestinal cholesterol absorption and its inactivation has been shown to alleviate NAFLD [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. More recently, curcumin and diosgenin, two natural compounds derived from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), were also reported to alleviate NAFLD by affecting NPC1L1 [

21,

22]. These findings indicate that NPC1L1 may be a potential target for NAFLD.

Danshen (the dried root of

Salvia miltiorrhiza Burge) is a well-known TCM and has gained increasing attention due to the protective effects on NAFLD [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. A meta-analysis suggests that Danshen preparations have positive effects on NAFLD, reducing hepatic lipid content and increasing total effectiveness rate [

23]. The effects of several compounds in Danshen on NAFLD have also been reported [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Salvianolic acid B, the hydrosoluble compound in Danshen, ameliorates NAFLD by regulating gut microbiota, LPS/TLR4 signaling pathway and NLRP3 inflammasome [

25,

26]. Tanshinone IIA, the liposoluble compound in Danshen, acts by inhibiting lipogenesis and inflammation and activating TFEB [

27,

28]. Nevertheless, owing to the nature of multi-components and multi-targets in TCM, the molecular basis and working mechanism of Danshen remain to be revealed.

In the present study, we identified cryptotanshinone (CTS), the liposoluble compound in Danshen, as a novel NPC1L1 inhibitor, and which significantly alleviated hepatic steatosis in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice. Our findings suggest that inhibition of NPC1L1 by CTS has the potential to serve as a new, safe and effective anti-NAFLD strategy for future clinical use. Furthermore, this study also provides a work basis for the future development of NPC1L1 inhibitors with high therapeutic indices and demonstrates the feasibility of exploring the bioactive molecules in TCM against new therapeutic targets.

3. Discussion

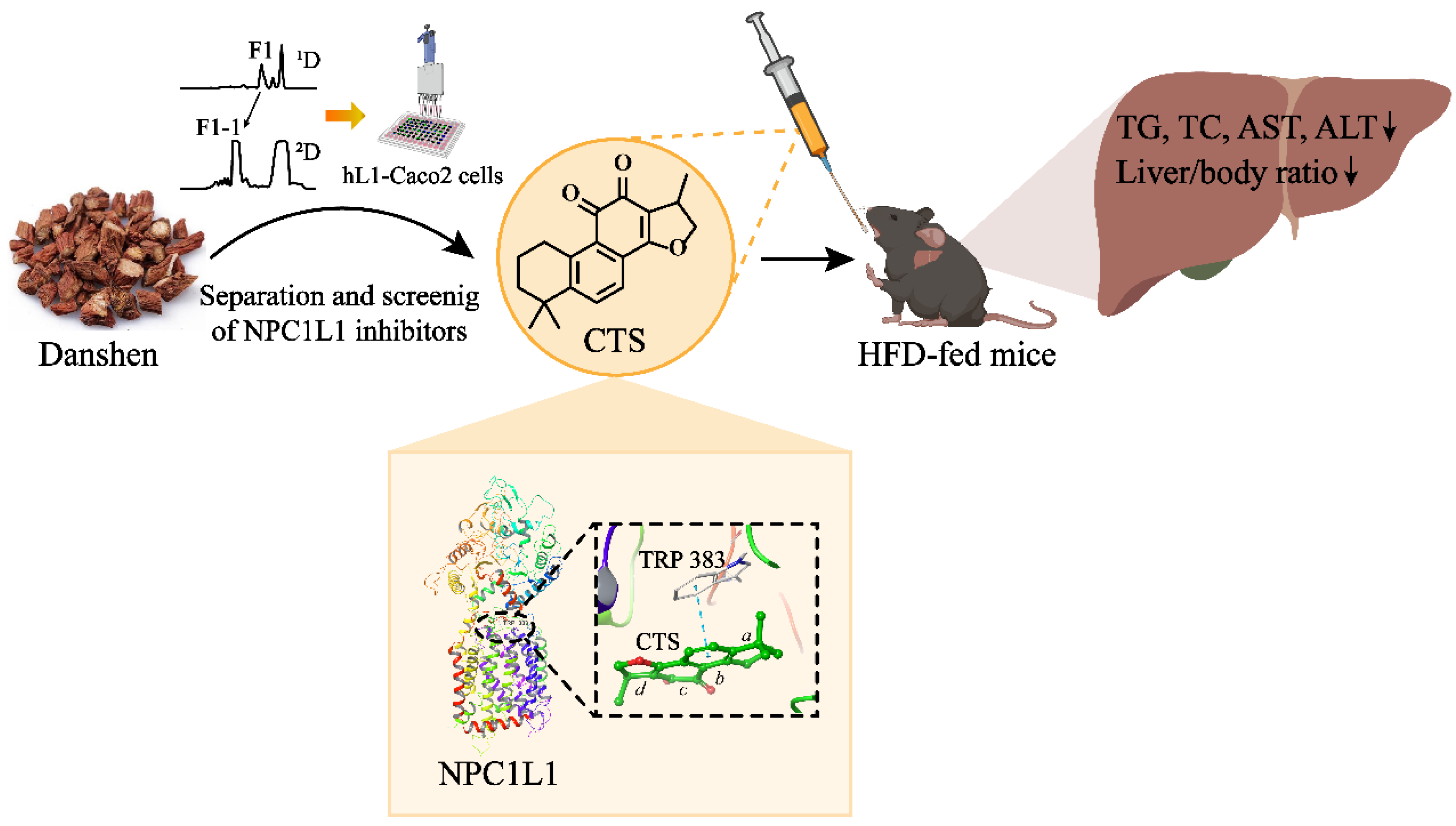

In this study, we developed a high-throughput screening method for NPC1L1 inhibitors and explored the active compounds in Danshen. Ultimately, CTS, the liposoluble compound in Danshen, was identified as a novel NPC1L1 inhibitor. Furthermore, CTS treatment significantly alleviated hepatic steatosis in HFD-fed NAFLD mice, suggesting that NPC1L1 inhibition by CTS may represent a potential therapeutic strategy for NAFLD (

Figure 6).

The development of NPC1L1 inhibitors encounters many challenges, and only one inhibitor (ezetimibe) has been approved so far [

30]. NPC1L1 is a 13-pass trans-membrane receptor protein with 1332 amino acids, making it extremely difficult to obtain the intact protein, which limits the screening of its inhibitors at the protein level. Although the crystal structure of NPC1L1 was revealed in 2020 [

31], its expression and purification remain challenging. However, the elucidated crystal structure will provide great help for virtual screening and binding studies of candidates with NPC1L1. The cell lines expressing NPC1L1 can be used for the screening of NPC1L1 inhibitors, such as Caco2 and HepG2 cells [

21,

32]. It is essentially to study the effects of candidates on the function of NPC1L1-mediated cholesterol absorption. [

3H]-cholesterol is the optimal tracer, while it is radioactive and the assay can’t be performed in a conventional laboratory [

33]. NBD-cholesterol labeled with green fluorescence is becoming an effective substitute for [

3H]-cholesterol to trace cholesterol absorption in cells [

21,

32]. Thus, for the high-throughput screening of NPC1L1 inhibitors, we constructed the stable Caco2 cell lines expressing hNPC1L1 (hL1-Caco2) and used NBD-cholesterol as the probe. The binding modes and stability between candidates and NPC1L1 were confirmed through molecular docking and dynamics simulation based on the elucidated crystal structure of NPC1L1.

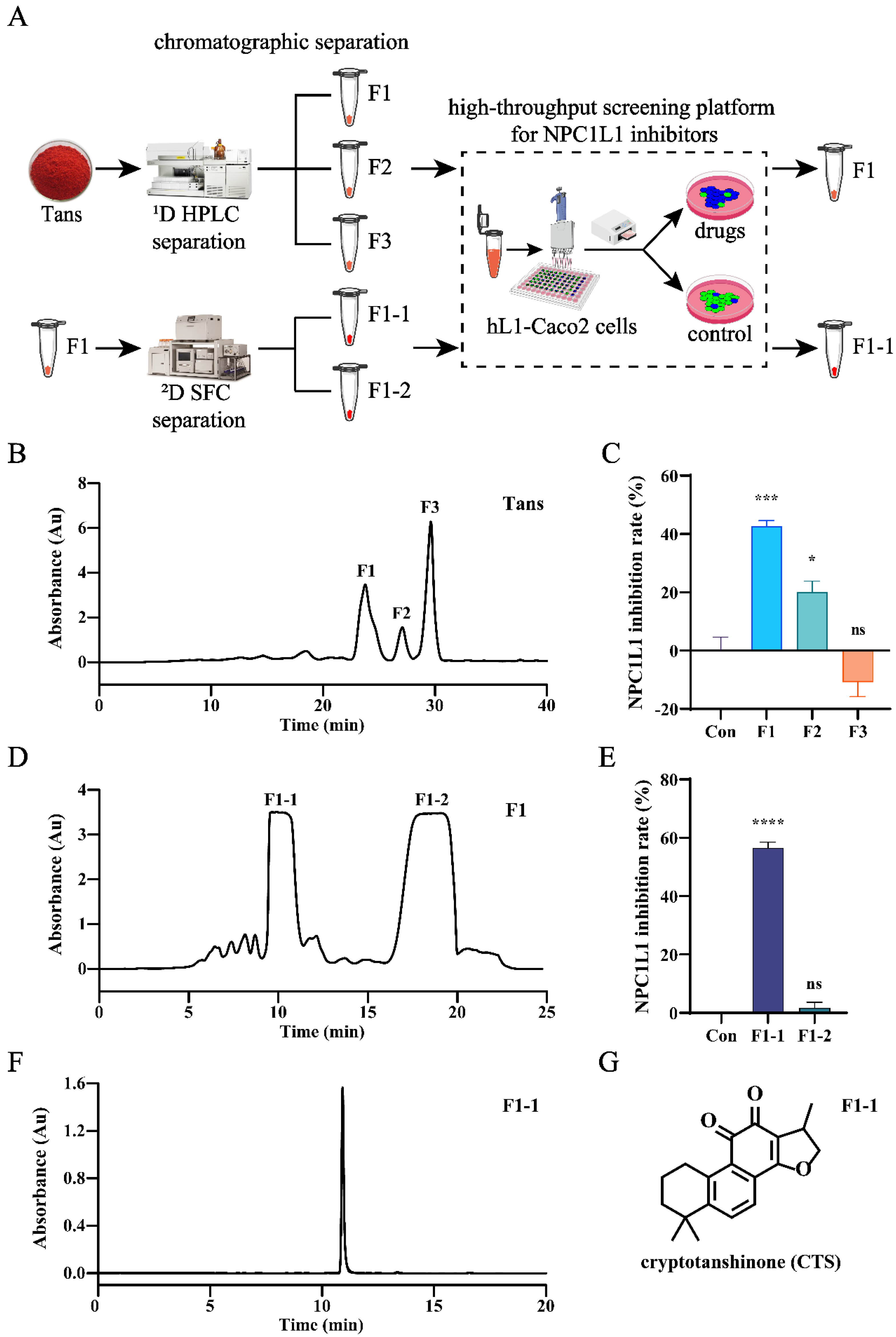

For the development of active compounds in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), effective separation of TCM and high-throughput screening are equally important. TCM has to suffer multiple rounds of screening and separation owing to its highly complex chemical components. Chromatographic techniques have demonstrated powerful separation capabilities in TCM [

34]. The optimization of chromatographic modes, stationary phases and mobile phases can provide comprehensive solutions for the multi-dimensional separation of TCM. Herein, to identify the active compounds in Danshen, activity-oriented separation was performed by two-dimensional chromatographic techniques (RPLC and SFC), and CTS was finally identified as a novel NPC1L1 inhibitor.

NPC1L1 mediates intestinal cholesterol absorption, and cholesterol flows in small intestine and liver by enterohepatic circulation [

21]. It is well established that excess cholesterol accelerates the progression of NAFLD [

10]. Accordingly, it makes sense in principle to alleviate NAFLD by inhibiting NPC1L1, which has been demonstrated in previous studies [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The possible mechanisms for inhibition of NPC1L1 to alleviate NAFLD has also been proposed. It was believed that NPC1L1 inhibition reduced hepatic cholesterol content and cholesterol-dependent activation of liver X receptor, a nuclear receptor promoting hepatic lipogenesis [

16]. In our study, CTS, the novel NPC1L1 inhibitor, significantly alleviated hepatic steatosis in HFD-fed mice, indicating that NPC1L1 inhibition with CTS could be a potential strategy for NAFLD treatment. Moreover, the positive effect of CTS on NAFLD also shows the feasibility of our screening protocol for NPC1L1 inhibitors.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Materials

Tanshinones (Tans), the liposoluble components in Danshen, was provided by Xi'an Hao-Xuan Bio-Tech Co., Ltd. (Xi'an, China). Cryptotanshinone (CTS, cat. BP0412, HPLC purity 97%), the liposoluble compound purified from Danshen, was purchased from Chengdu Biopurify Phytochemicals Ltd. (Chengdu, China). The probe molecule 22-(N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1, 3-diazol-4-yl)-labeled cholesterol (NBD-cholesterol) and reagents for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Other relevant reagents for chromatographic separation and analysis were all purchased from Meryer Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

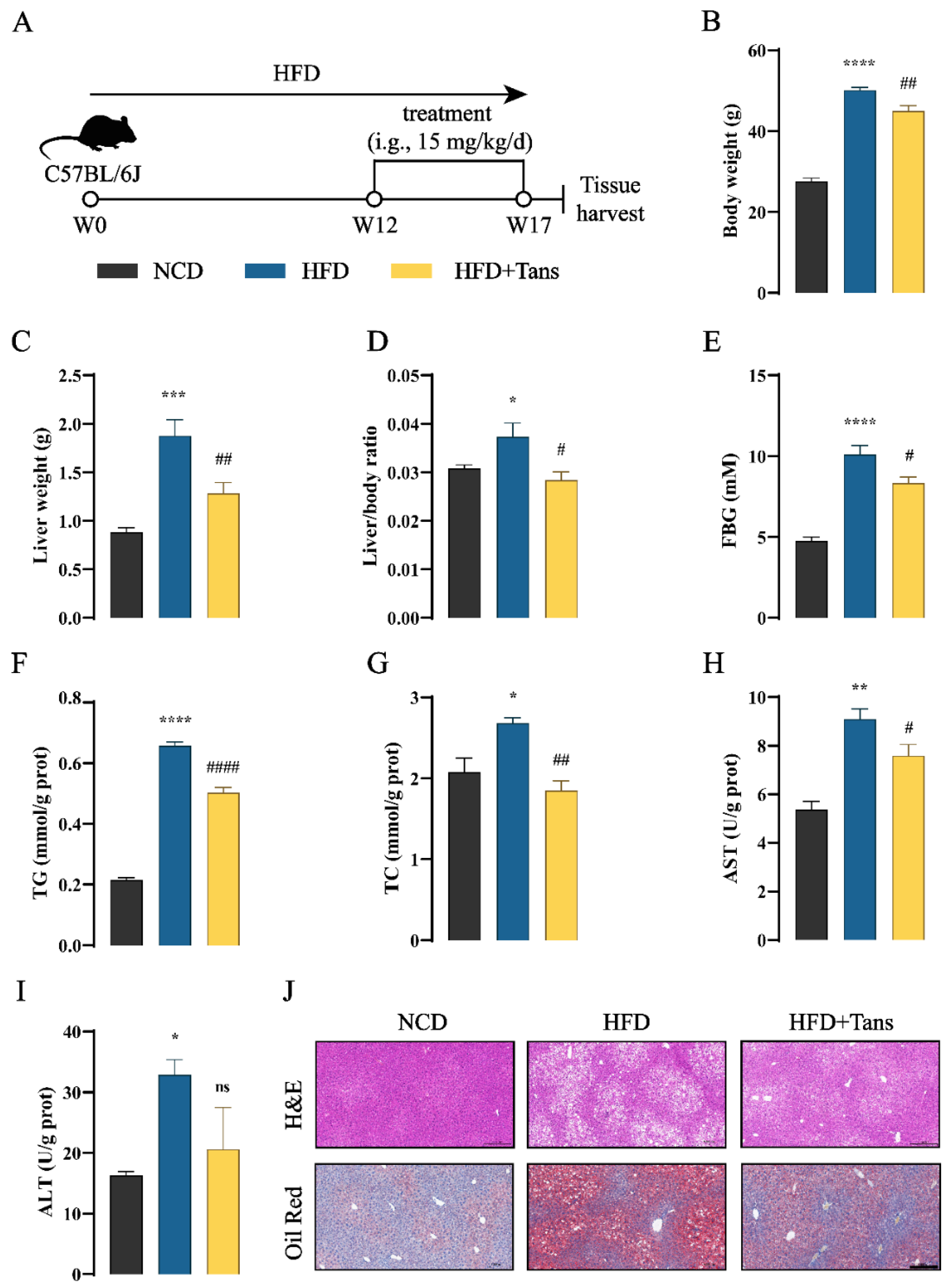

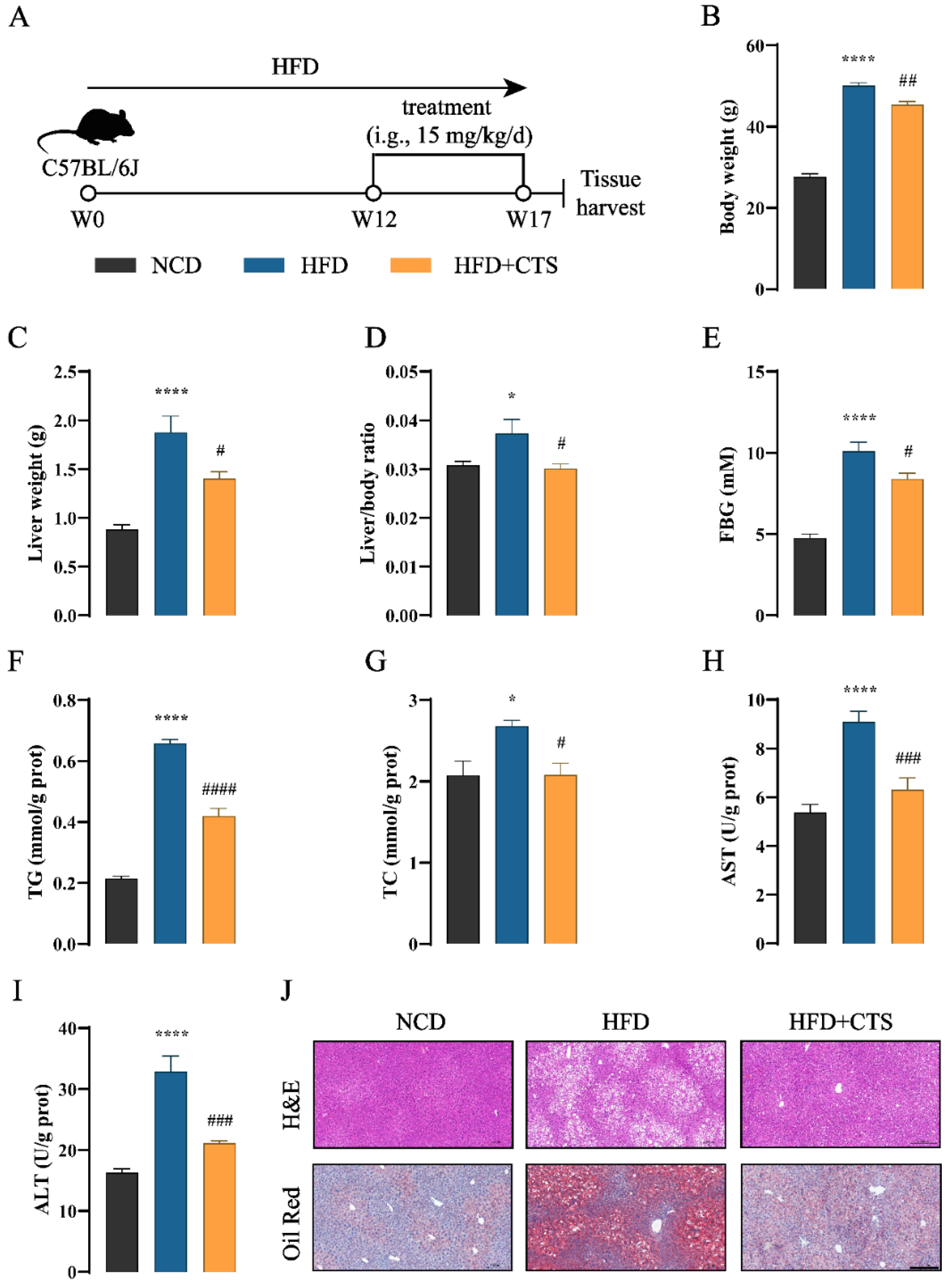

4.2. Animal Experiments

Male C57BL/6J mice (6-8 weeks old, 20 ± 2 g) were purchased from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China) and housed in a specific pathogen-free condition at 25 °C with 12 h light/dark cycle. After 1 week of acclimatization, C57BL/6J mice were fed either a high fat diet (60% fat, cat. TP23300, Trophic Animal Feed High-tech Co., Ltd., Nantong, China) or a normal chow diet (10% fat, cat. SWS9102, Jiangsu Xietong Pharmaceutical Bio-engineering Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) for 12 weeks and then mice were randomly assigned to four groups (n=5): normal chow diet group (NCD), high fat diet group (HFD), high fat diet with Tans treatment group (HFD+Tans), high fat diet with CTS treatment group (HFD+CTS). The drugs were dissolved in 0.5% carboxy-methyl-cellulose sodium (CMC-Na, Solarbio, Beijing, China) and administered daily via intragastric gavage with 15 mg/kg for 5 weeks. The dose employed in this study was based on previous study regarding the effectiveness of CTS in C57BL/6J mice with atherosclerosis [

35]. The NCD and HFD groups were orally administered 0.5% CMC-Na alone. Food and water were available

ad libitum. After 12 hours of fasting, all mice were anesthetized and sacrificed. The liver tissues were collected for further analysis.

The animal experiment was approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Jiangnan University (JN.No20231007c1400430[468]). All animal experimental procedures followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

4.3. Establishment of Stable Caco2 Cell Lines Expressing Human-NPC1L1 (hL1-Caco2) and Cell Culture

The plasmid expressing human-NPC1L1 (hNPC1L1, NCBI Reference Sequence: NM_001101648.2) was constructed by Shenzhen BORUI Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). The CDS of hNPC1L1 was connected to the lentiviral vector EDV0005 containing puromycin resistance (puroR) gene. Kozak sequence was added to 5' end, and 3×Flag tag was added to 3' end. The recombinant plasmid was packaged with lentivirus and then transfected to Caco2 cells. The polyclonal cell pools were screened with 2 µg/mL puromycin (Meilunbio, Dalian, China) for two weeks. After limiting dilution, single-cell clones were generated and expanded to obtain monoclonal cell lines. The resulting stable Caco2 cell lines expressing human-NPC1L1 (hL1-Caco2) were cultured in high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (VivaCell Biosciences, Shanghai, China) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Meilunbio, Dalian, China) at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

4.4. Biochemical Analysis

Levels of hepatic total triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine transferase (ALT) were measured using commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng, China). Briefly, liver tissues (80-100 mg) were homogenized in cold PBS at a ratio of 1:9 (w/v). The homogenate was centrifuged (2500 rpm, 4 °C, 10 min) and the resulting supernatant was diluted to determine above indexes according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.5. Pathological Analysis

The liver was collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The paraffin-embedded sections were subjected to hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. The optimal cutting temperature-embedded sections were subjected to Oil Red O staining. The stained images were scanned by Panoramic MIDI (3D HISTECH, Budapest, Hungary) and presented at 200-fold magnification.

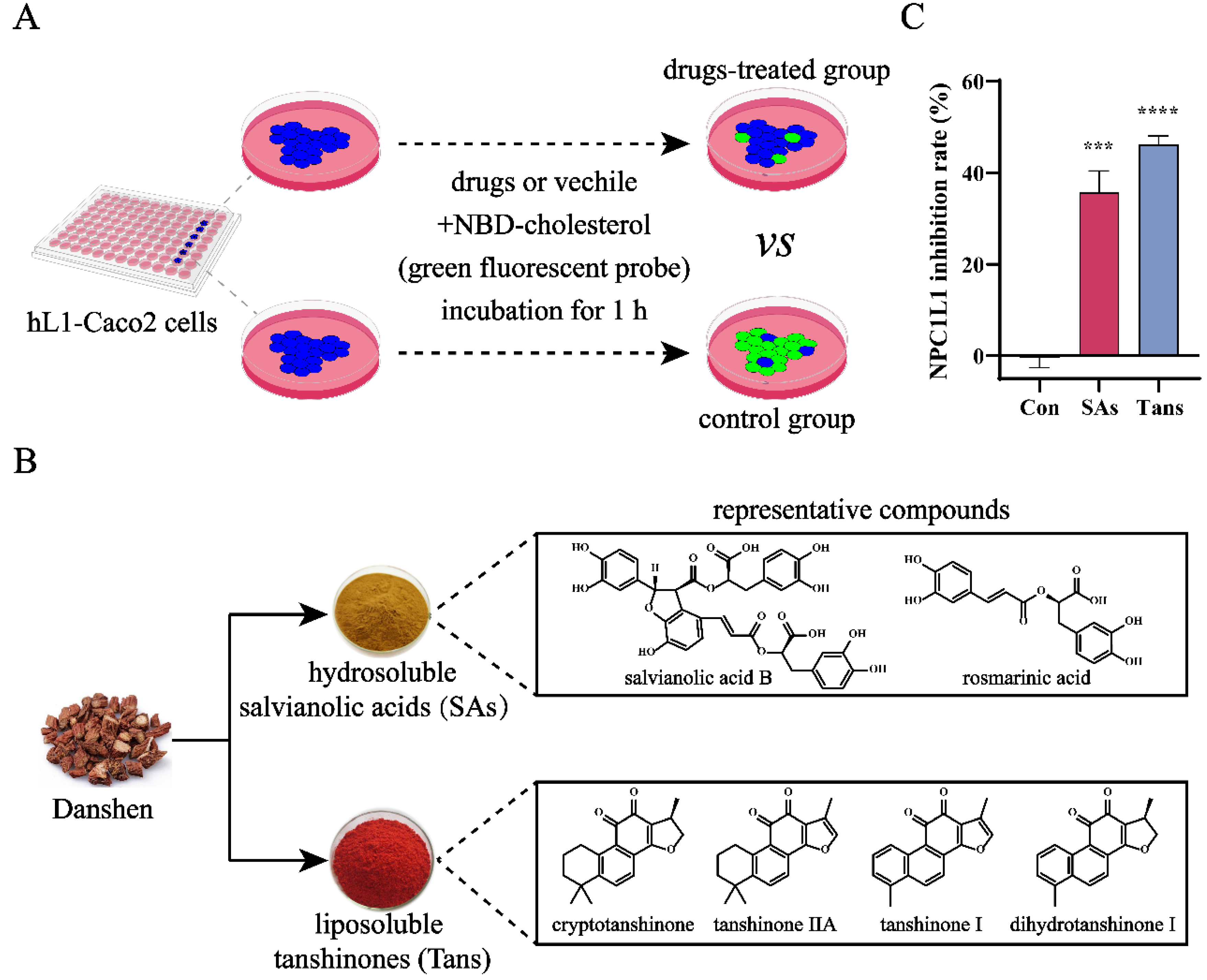

4.6. High-Throughput Screening of NPC1L1 Inhibitors

The high-throughput screening of NPC1L1 inhibitors was conducted by Shenzhen BORUI Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). The inhibitory activity against NPC1L1 was evaluated by NPC1L1-mediated intestinal cholesterol absorption in hL1-Caco2 cells. NBD-cholesterol with green fluorescence was used as the probe molecule to indicate free cholesterol absorbed by NPC1L1. In brief, hL1-Caco2 cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 4×104 cells/well and cultured until 100% confluence. The cells were then incubated with NBD-cholesterol (20 μg/mL) and indicated drugs for 60 min. Cellular mean fluorescence intensity (content of NBD-cholesterol absorbed by NPC1L1) at 0 min (F0) and 60 min (F60) were recorded by ELx-800 microplate reader (BioTek, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at λEx/Em 485/535 nm. The slope of fluorescence change (absorption rate of NBD-cholesterol by NPC1L1) was normalized by control group and defined as NPC1L1 inhibition rate.

4.7. Separation and Analysis of Tans and Related Fractions

The activity-oriented separation of Tans was performed by off-line two-dimensional chromatography. A C18HD column (50×250 mm, 10 µm, 100 Å, Acchrom, Beijing, China) was used for the first dimensional (1D) separation on a preparative high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Auto-P, Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Tans was dissolved in MeOH at a concentration of 10 mg/mL and 10 µL of the solution was injected to the system. The elution was carried out with 70~100% MeOH/H2O (v/v) for 40 min at a flow rate of 80 mL/min, and the three most abundant fractions at 270 nm were collected.

The second dimensional (2D) separation was accomplished on a semi-preparative supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) system (Investigator, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) using a ChiralGel BH column (10×250 mm, 7 µm, 100 Å, Acchrom, Beijing, China) at 35 ℃. Automated back-pressure regulator was set as 100 bar. Dichloromethane was used to dissolve the active fraction F1 (50 mg/mL) and 200 µL of which was injected. The mobile phase was composed of CO2 and MeOH, and a gradient program was employed as follows: 0~12 min, 5~20% MeOH; 12~18 min, 20% MeOH; 18.1~21 min, 65% MeOH; 21.1~25, 5% MeOH. The flow rate was 12 mL/min. The two most abundant fractions at 270 nm were collected.

LC-MS analysis of the active fraction F1-1 was conducted on an UPLC-QE Plus system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A BEH Phenyl column (2.1×150 mm, 1.7 µm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was used for the chromatographic separation at 35 ºC. The mobile phase consisted of (A) 0.1% FA/H2O (v/v) and B (ACN), and the elution was carried out with 35~50% B for 20 min at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The sample (F1-1) was dissolved using ACN at a concentration of 10 ppm and the injection volume was 0.3 µL. Full MS/dd-MS2 signal in positive ion mode was monitored with a scan range of 200~1500 m/z. Other MS parameters were set as default values.

The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of F1-1 were experimented using chloroform-d and recorded on a Bruker Avance III-400 spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin AG, Fällanden, Switzerland).

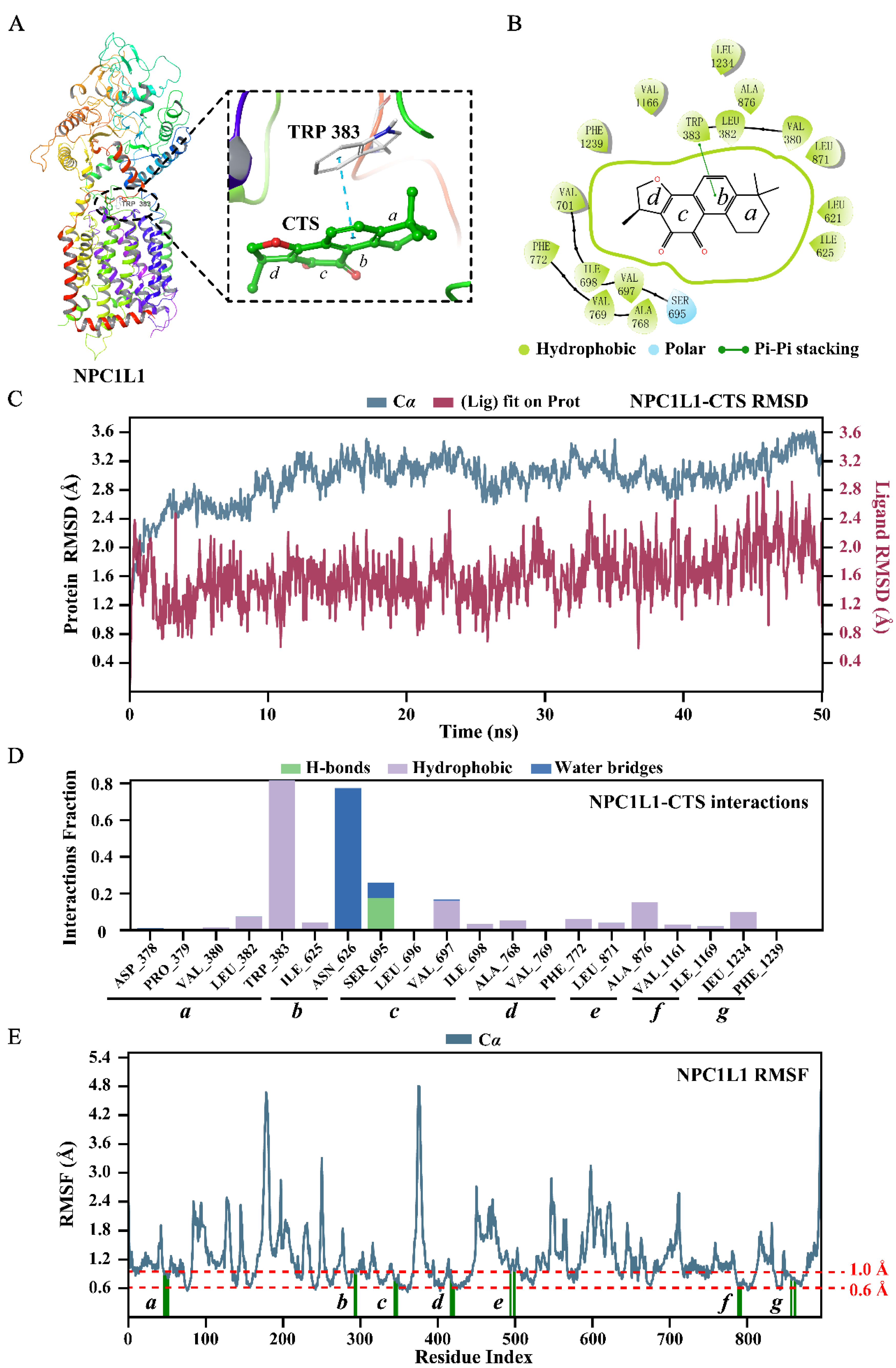

4.8. Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation

The co-crystal structure of NPC1L1 was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB: 7DFZ), and then prepared using Schrödinger 2021-2 (Schrödinger LLC, NY, USA). Protein Prepare Wizard module was employed to hydrogenate the complex, remove crystal waters and repair loop regions. The energy minimization was carried out by optimized potentials for liquid simulations-2005 force field. The docking protein grid (10 Å × 10 Å × 10 Å) centered on the original ligand was generated using the Receptor Grid Generation module. Subsequently, the original ligand was removed and CTS was docked into the prepared structure using the Glide module. The binding free energy was calculated using the molecular mechanics-generalized Born surface area method.

A 50-ns molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was performed to confirm the binding stability of NPC1L1-CTS complex using Desmond module of Schrödinger suite. The protocol was referenced to our previous study [

36].

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Origin Pro 2021 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) and GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The results were presented as the mean ± SEM. Student’s t test and one-way ANOVA were employed for two groups and multiple groups comparison, respectively. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

D.X.: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. X.J.: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. X.X.: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. H.Z.: Project administration. D.Y. and G.J.: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. X.Y. and S.Z.: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Z.G.: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. X.L.: Resources, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Tans inhibits NPC1L1-mediated cholesterol absorption in hL1-Caco2 cells. (A) Working principle of the high-throughput screening platform for NPC1L1 inhibitors. The inhibition activity against NPC1L1 was evaluated by measuring NPC1L1-mediated intestinal cholesterol absorption. Briefly, hL1-Caco2 cells were seeded into 96-well plates and the NBD-cholesterol (green fluorescent probe) absorbed by NPC1L1 was reduced after drugs treatment. (B) Chemical components of Danshen and structures of the representative compounds. (C) Inhibitory effects of the two major components in Danshen against NPC1L1. SAs, 100 µM; Tans, 8 µM. Data are presented as the means±SEMs (n=3 per group). ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs. the control group (Con).

Figure 1.

Tans inhibits NPC1L1-mediated cholesterol absorption in hL1-Caco2 cells. (A) Working principle of the high-throughput screening platform for NPC1L1 inhibitors. The inhibition activity against NPC1L1 was evaluated by measuring NPC1L1-mediated intestinal cholesterol absorption. Briefly, hL1-Caco2 cells were seeded into 96-well plates and the NBD-cholesterol (green fluorescent probe) absorbed by NPC1L1 was reduced after drugs treatment. (B) Chemical components of Danshen and structures of the representative compounds. (C) Inhibitory effects of the two major components in Danshen against NPC1L1. SAs, 100 µM; Tans, 8 µM. Data are presented as the means±SEMs (n=3 per group). ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs. the control group (Con).

Figure 2.

Tans protects against HFD-induced NAFLD in mice. (A) Schematic diagram of Tans treatment for NAFLD. C57BL/6J mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) for 12 weeks, followed by oral administration of Tans (15 mg/kg/d) for another 5 weeks (n=5). (B) Body weight. (C) Liver weight. (D) Liver/body ratio. (E) FBG levels. (F)-(I) Hepatic levels of TG (F), TC (G), AST (H) and ALT (I). (J) Representative H&E and Oil Red O staining of liver sections. Magnification: 200 ×, Scale bars: 200 µm. Data are presented as the means±SEMs (n=5 per group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs. the normal chow diet (NCD) group. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ####p < 0.0001 vs. the HFD group. ns, not significant.

Figure 2.

Tans protects against HFD-induced NAFLD in mice. (A) Schematic diagram of Tans treatment for NAFLD. C57BL/6J mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) for 12 weeks, followed by oral administration of Tans (15 mg/kg/d) for another 5 weeks (n=5). (B) Body weight. (C) Liver weight. (D) Liver/body ratio. (E) FBG levels. (F)-(I) Hepatic levels of TG (F), TC (G), AST (H) and ALT (I). (J) Representative H&E and Oil Red O staining of liver sections. Magnification: 200 ×, Scale bars: 200 µm. Data are presented as the means±SEMs (n=5 per group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs. the normal chow diet (NCD) group. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ####p < 0.0001 vs. the HFD group. ns, not significant.

Figure 3.

CTS is the active compound in Tans that inhibits NPC1L1-mediated cholesterol absorption in hL1-Caco2 cells. (A) The schematic diagram of the screening for NPC1L1 inhibitors in Tans. (B) The HPLC separation chromatogram of Tans. (C) NPC1L1 inhibition rates of the three major fractions (10 µM) obtained by HPLC separation. (D) The SFC separation chromatogram of the fraction F1. (E) NPC1L1 inhibition rates of the two major fractions (10 µM) obtained by SFC separation. (F) Chromatogram of F1-1. (G) Structure of F1-1. Data are presented as the means±SEMs (n=3 per group). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs. the control group (Con). ns, not significant.

Figure 3.

CTS is the active compound in Tans that inhibits NPC1L1-mediated cholesterol absorption in hL1-Caco2 cells. (A) The schematic diagram of the screening for NPC1L1 inhibitors in Tans. (B) The HPLC separation chromatogram of Tans. (C) NPC1L1 inhibition rates of the three major fractions (10 µM) obtained by HPLC separation. (D) The SFC separation chromatogram of the fraction F1. (E) NPC1L1 inhibition rates of the two major fractions (10 µM) obtained by SFC separation. (F) Chromatogram of F1-1. (G) Structure of F1-1. Data are presented as the means±SEMs (n=3 per group). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs. the control group (Con). ns, not significant.

Figure 4.

CTS prevents HFD-induced NAFLD in mice. (A) Schematic diagram of CTS for NAFLD treatment. C57BL/6J mice were induced by a high-fat diet (HFD) for 12 weeks, followed by oral treated with CTS (15 mg/kg/d) for another 5 weeks (n=5). (B) Body weight. (C) Liver weight. (D) Liver/body ratio. (E) FBG levels. (F)-(I) Hepatic levels of TG (F), TC (G), AST (H) and ALT (I). (J) Representative H&E and Oil Red O staining of liver sections. Magnification: 200 ×, scale bars: 200 µm. Data are presented as the means±SEMs (n=5 per group). *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001 vs. the normal chow diet (NCD) group. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001 vs. the HFD group. It should be emphasized that this animal experiment was conducted simultaneously with Tans treatment. Consequently, the NCD and HFD groups of the two animal experiments in this study shared the same dataset.

Figure 4.

CTS prevents HFD-induced NAFLD in mice. (A) Schematic diagram of CTS for NAFLD treatment. C57BL/6J mice were induced by a high-fat diet (HFD) for 12 weeks, followed by oral treated with CTS (15 mg/kg/d) for another 5 weeks (n=5). (B) Body weight. (C) Liver weight. (D) Liver/body ratio. (E) FBG levels. (F)-(I) Hepatic levels of TG (F), TC (G), AST (H) and ALT (I). (J) Representative H&E and Oil Red O staining of liver sections. Magnification: 200 ×, scale bars: 200 µm. Data are presented as the means±SEMs (n=5 per group). *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001 vs. the normal chow diet (NCD) group. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001 vs. the HFD group. It should be emphasized that this animal experiment was conducted simultaneously with Tans treatment. Consequently, the NCD and HFD groups of the two animal experiments in this study shared the same dataset.

Figure 5.

CTS stably binds with NPC1L1. The binding modes of CTS to NPC1L1 (PDB: 7DFZ): (A) Three-dimensional presentation. NPC1L1 is represented by a ribbon diagram. CTS is represented by a ball-and-stick model. Carbon atoms are shown in green and oxygen atoms are shown in red. The π-π interaction between CTS and the key amino acid (TRP 383) is displayed using blue dashed lines; (B) Two-dimensional presentation. The thin green line marks the π-π interaction between CTS and TRP 383. The thick green circle shows the hydrophobic interaction between CTS and amino acids in the docking pocket. The molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of NPC1L1-CTS complex: (C) Root mean square deviation (RMSD) plots of NPC1L1 (blue, left Y-axis) and CTS (red, right Y-axis); (D) NPC1L1-CTS interactions; (E) Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) plot of NPC1L1. NPC1L1 protein residues that interact with CTS are marked with green vertical bars.

Figure 5.

CTS stably binds with NPC1L1. The binding modes of CTS to NPC1L1 (PDB: 7DFZ): (A) Three-dimensional presentation. NPC1L1 is represented by a ribbon diagram. CTS is represented by a ball-and-stick model. Carbon atoms are shown in green and oxygen atoms are shown in red. The π-π interaction between CTS and the key amino acid (TRP 383) is displayed using blue dashed lines; (B) Two-dimensional presentation. The thin green line marks the π-π interaction between CTS and TRP 383. The thick green circle shows the hydrophobic interaction between CTS and amino acids in the docking pocket. The molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of NPC1L1-CTS complex: (C) Root mean square deviation (RMSD) plots of NPC1L1 (blue, left Y-axis) and CTS (red, right Y-axis); (D) NPC1L1-CTS interactions; (E) Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) plot of NPC1L1. NPC1L1 protein residues that interact with CTS are marked with green vertical bars.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the study. CTS, the liposoluble compound in Danshen, was identified as a novel NPC1L1 inhibitor and has a positive effect on NAFLD in HFD-fed mice. Mechanistically, CTS alleviates NAFLD by inhibiting NPC1L1-mediated intestinal cholesterol absorption.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the study. CTS, the liposoluble compound in Danshen, was identified as a novel NPC1L1 inhibitor and has a positive effect on NAFLD in HFD-fed mice. Mechanistically, CTS alleviates NAFLD by inhibiting NPC1L1-mediated intestinal cholesterol absorption.