1. Introduction

Mineral prospectivity mapping (MPM) is a multi-criteria and computer-aided approach that aims to delineate and prioritize favorable exploration targets for discovering new mineral deposits of the type sought [

1,

2]. Advances in geoscientific computer techniques facilitate the collection, integration, visualization, and modeling of geo-information representing vital ore-forming processes of mineral system [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], which builds a sound foundation for MPM. In recent two decades, machine learning algorithms boom in the field of mineral potential modeling, among which supervised data-driven machine learning are the most commonly used [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Data-driven algorithm generates models and assigns evidential weights based on the spatial relationship between evidential maps and known mineral deposits [

15,

16]. This method has flourished in the MPM due to the abundant publicly accessible multi-source data, excellent model performance and easy transfer of the state-of-the-art algorithms from other fields.

Supervised data-driven machine learning-based MPM is faced with three intrinsic challenges, that is: (i) scarcity of labeled data; (ii) over-fitting of models; and (iii) uncertainty of predictive results [

4]. The origin of these challenges roots in that machine learning is data-greedy, requiring a labeled dataset consisting of a large number of both positive and negative samples. However, in the MPM field, as end-products of rare mineralization events, mineral deposits which serve as positive samples are extremely scarce [

17]. On the other hand, machine learning algorithms, mostly stem from matured industrial field aiming to handle thousands of or even millions of samples, tend to have elaborately complex architectures. Introduction of these complex machine learning models on MPM scarce data easily induces severe over-fitting problems [

18]. Besides, the uncertainty, owing to incomplete understanding of mineral systems, bias occurring in the observation and measurement of exploration criteria, as well as inherent and stochastic errors when training and applying machine learning models [

19], inevitably emerges within the whole process of MPM modeling.

Few-shot learning (FSL), which aims to enable learning from a limited number of samples, is an alternative option to address the above-mentioned issues. The methods of few-shot learning can be roughly categorized into three threads, namely data augmentation, transfer learning and meta-learning [

20]. To the best of our knowledge, only the former two methods have been applied in the MPM field. A straightforward solution of few-shot issues is to enlarge the number of labeled data by data augmentation [

21]. Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) has been employed by many scholars to over-sample labeled data of minor class in the MPM modeling, demonstrating the effectiveness of this technique in improving the performance of the models trained by imbalanced data [

17,

22,

23]. Learning knowledge from related large data and transferring it to the target scarce data is the most intuitive solution for few-shot tasks [

20]. However, there are few contributions related to application of this method in MPM field, except for an attempt of transferring classic image-based network models to map mineral potential [

24,

25,

26]. Such limited application results from a fact that it is hard to find a large transferable source dataset that is similar with or related to target complex mineralization data.

A FSL framework combining data augmentation and transfer learning is proposed in this study. SMOTE augmented data serve as synthetic source data related to target mineralization dataset, and the knowledge learned from the source dataset transfers to map mineral prospectivity via fine-tuning. Another focus of this study is to quantitatively evaluate and control the over-fitting and uncertainty, generating a robust and low-risk exploration targeting model. This framework has been applied to tungsten prospectivity mapping in southern Jiangxi Province, which is a representative brown field well-suited for a data-driven prospectivity modeling.

2. Study Area and Data Used

2.1. Geological Setting

The southern Jiangxi Province, situated in the central part of the Cathaysian Block, constitutes the eastern segment of the giant Nanling metallogenic belt (

Figure 1). The sedimentary successions exposed in this area span from Proterozoic to Cenozoic, with absence of Silurian and Triassic units. The Proterozoic lower greenschist facies clastic rocks compose the metamorphic basement, which is overlain by Paleozoic shallow marine carbonate and siliclastic rocks. Mesozoic volcaniclastics and terrigenous red-bed sandstone are preserved in faulted basins [

27]. The tectonic framework in this region comprises a group of NE-, EW- and NW-trending faults. More than 400 granitic intrusions outcrop in this area, occupying an extensive surface area of 14,000 km

2 [

27]. Four episodes of granitic magmatism have been identified, namely Caledonian, Hercynian, Indosinian and Yanshanian, of which the Yanshanian intrusions are believed to be responsible for widespread tungsten mineralization in this area. The southern Jiangxi Province is well known as a tungsten-producing region, characterized by its dominant quartz vein-type wolframite deposits [

27,

28]. Considerable tungsten deposits, including eight large-scale, 18 moderate-scale and numerous small-scale deposits, have been mined or discovered in this area, accumulating a proved tungsten reserve of 1.7 Mt [29]. Most of tungsten deposits are located in four ore clustering districts including Chongyi-Dayu-Shangyou, Ganxian-Yudu, Longnan-Dingnan-Quanan and Ningdu-Xingguo (

Figure 1).

2.2. Mineral System

In order to extract reliable targeting criteria for the following prospectivity modeling, a mineral systems approach is employed to transfer understandings of tungsten mineral system into a set of mappable spatial proxies representing critical ore-forming processes related to source, transport, physical trap and chemical deposition [32–35] (

Figure 2).

The hydrothermal mineral systems in many cases have a single source that provides not only energy gradient triggering mineralization events but also necessary components required for ore formation (e.g., metal, fluids and ligands) [34]. In the study area, the Yanshanian granitic intrusions are believed to play such a role that provides ore-related fluids and metals, based on the understandings of previous researches. The chronological studies indicate that the formation of tungsten orebodies in the study area is temporally identical to their proximal granitic intrusions (mainly 170-150 Ma) [36–38]. Spatially, most of the tungsten orebodies are found at the inner- and/or out-contacts of Yanshanian granitic intrusions [39,40]. Accordingly, proximity to exposed Yanshanian intrusions, as well as magnetic and gravity anomalies that may infer in-depth intrusions, were employed as evidential layers representing source process.

Active pathways are essential for transporting ore-forming components from deep source regions to shallow trap zones [34]. As mentioned above, the Yanshanian tectono-magmatic activity is believed to be responsible for regional tungsten mineralization, while the regional fault system was interpreted to provide pathways for the ascent of ore-related magma. It is noteworthy that only those faults formed before or in the mineralization era can play the pathway role that promotes the mineralization process. By contrast, the faults formed after mineralization usually disconnect pre-formed ore-bearing structures and thus exerting a negative impact on mineral prospecting. The previous spatial analyses indicate that the EW- and NE-trending faults were formed or re-activated in the Yanshanian epoch, which serve as metalliferous magma/fluid-conducting conduits [41]. The Density of these faults was used to reflect transport process.

Regarding hydrothermal deposits, physical traps are favorable loci that trap ore-forming fluids. These loci are mostly related to dilatational zones induced by ore-related structural activities [42]. In the study area, EW- and NE-trending faults in the caprocks constitute transport networks for the metalliferous fluids, while the intersections of these faults provide dilatational zones with high permeability that are conducive to trap and focus the fluids [41].

A hydrothermal deposit is the direct result of massive metal deposition. This critical process stems from reduction of metal solubility in fluids, which is induced by a variety of sub-processes associated with changes in physical and chemical conditions [34], e.g., fluid mixing, fluid-rock reactions, and cooling of fluids. Unfortunately, it is impossible to directly trace these sub-processes from the perspective of regional-scale spatial proxies. Instead, we employ geochemical anomalies, which are footprints of ore-induced chemical sub-processes, as effective proxies of metal deposition. W, Mn and Fe are selected as targeted geochemical elements since they are components of wolframite ((Fe,Mn)WO4) that dominates the ores in the study area.

2.3. Input Dataset

An integral and reliable input dataset is an essential prerequisite for a robust machine learning-based predictive modeling. For a MPM task, the preparation of input dataset includes data generation of evidential layers and target variables.

The evidential layers are featured predictive maps representing critical ore-forming processes, which are employed as judging conditions for predicting mineral potential. As mentioned above, eight evidential layers were generated on the basis of analyses of the mineral systems approach (

Figure 2). The mappable intrusions, faults and geophysical anomalies were derived from the Database of Ganzhou Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources (DGBGMR) based on field investigations since 1980s. Geochemical anomalies of W, Mn and Fe were extracted from stream sediment data of Nanling Range, which stem from China’s National Geochemical Mapping Project with sampling density of one sample per km

2 [43,44]. The eight predictor maps were generated by rasterizing mappable ore-related features. The rasterizing cell size, i.e., predictive resolution, is 450 m, which is determined based on resolution of evidential maps and distance of any two nearest deposits [9,45,46]. A total of 195, 174 cells were generated covering the whole study area.

Target variables in the MPM includes positive and negative samples used for training and testing models. 118 mines, historic mines and mineralized spots representing known deposit locations were derived from DGBGMR and online database of China Geology Survey [31], which were employed as positive samples. The negative samples representing non-deposit locations were selected based on the criteria proposed by Carranza and Zuo [47,48]. 346 non-deposit locations were selected as negative samples in this study, allowing for an experiment of data imbalancing.

3. Methods

3.1. Few-Shot Learning Framework

The proposed few-shot learning framework is composed of two components including data augmentation for addressing imbalanced dataset and transfer learning for training prospectivity model by limited labeled data, as shown in

Figure 3.

An imbalanced dataset consists of variable classes that are not approximately equally represented [49]. It is widely acknowledged that machine learning algorithms have poor performance in highly imbalanced datasets [

50]. However, it is a fact that non-deposit sites (negative samples) largely outnumber deposit locations (positive samples) in any case study of MPM, arising a severe issue of imbalanced dataset. This issue can be addressed by assigning costs to training samples of different classes or re-sampling of the original dataset. The latter solution, including over-sampling of the minority class and under-sampling of the majority class, is commonly used in machine learning-based MPM. SMOTE, proven to be effective in the MPM prediction [

17,

51], is employed in this study to over-sample minor deposits. SMOTE works by generating new synthetic samples from the existing samples of minority class based on their nearest neighbors in the feature space. As depicted in

Figure 4, for a given minority-class sample

Xi,

k (

k=6 in this example) nearest neighboring minority-class samples are chosen.

X2 is randomly selected from these four samples, and then a feature vector along the line segment between

Xi and

X2 is generated. A synthetic sample

Xn is created by using equation (1) [

52].

Where rand(0,1) denotes a random number ranging from 0 to 1.

The data augmentation is task-specific, yielding the data well-suited for the subsequent training tasks. In this study, 20% and 15% deposit samples were randomly selected from the original dataset of positive labels. They combined with an equal number of randomly selected non-deposits to constitute the test and target domain dataset, respectively. SOMTE was then conducted on the rest 76 deposits and 304 non-deposits to generate a synthetic balanced dataset of source domain (

Figure 3).

Essentially, transfer learning is the reuse of pre-trained model on a new domain, which includes two key tasks, namely learning knowledge from lots of available labeled data and transferring knowledge to a different but related problem. As mentioned above, the difficulty of finding a model of similar task transferable for training non-image-based ore-related data is the severest issue that impedes the application of transfer learning in the MPM field. In this study, the solution to this issue is to pre-train the transferable model based on the large synthetic dataset of source domain. The idea of meta-learning was introduced in the process of pre-training. Specifically,

N subsets called support sets were generated by bootstrapping. Bootstrapping is a sampling procedure that randomly selects samples from the original dataset with replacement. A set of neural network models were trained by support sets, after which they ensembled to generate a pre-trained model. The model parameters were assumed to reach a suboptimal state by multi-task pre-training in the source domain, and then a small number of samples in the target domain were used to train the model to achieve the optimal state by slight tune of model architecture [

53]. Such process is called fine-tuning. By fine-tuning, the trained model reached satisfactory performance whilst fitting the data distribution of the target domain. The trained model was assessed by test dataset and output the final predictions.

3.2. Benchmark Machine Learning Algorithms

Benchmark algorithms allow for comparative study of model performance, which is strongly suggested in the data-driven machine learning-based modeling [

54]. Two widely applied models, namely random forest and support vector machine, were employed as benchmark algorithms in this study.

Random forest, proposed by Breiman [

55], is a classic ensemble learning algorithm that aggregates a large number of base tree models to perform repeated predictions of a specific phenomenon [

16,

56]. Two key random scenarios are employed to enhance the performance of model. Firstly, bootstrapping, as mentioned above, is used to create diverse subsets of original labeled data for training each base tree. Secondly, a randomly selected subset of input features is utilized as discriminative conditions at each node of the tree in the forest. The algorithm then searches across all the nodes to find the optimal one that maximizes the purity of resulting trees. The purity can be measured by many indices, e.g., Gini index, Chi-square and Gain ratio [

16]. The final prediction is made by majority voting of all the base trees in the forest.

Support vector machine exhibits its great performance in conditional classification, based on theories of statistical learning and structural risk minimization [

47,

57,

58]. The algorithm seeks to generate an optimal classifier that separates labels of different classes by the widest discriminative boundaries. This algorithm works by finding a hyperplane that has the largest margin in the feature space, i.e., the distance between the hyperplane and its closest data points of each class is maximum, which allows for generation of the classier with the lowest errors [

59,

60].

Since benchmark algorithms are not the main theme of this study, only a brief introduction is presented above. Detailed descriptions of the algorithms can be referred to [

47,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60].

3.3. Performance Metric

The model performance can be evaluated by a set of quantitative measurements. The indices employed in this study emphasize their capability in assessing the robustness and predictive efficiency of the models.

The classification accuracy is used to rapidly appraise the effect of parameter optimization. It can be calculated by the ratio of the number of correctly classified samples to the total number of the samples, however, this index fails to evaluate the predictive performance of the model. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and success-rate curve are used to measure the overall predictive performance. There curves are drawn based on the varying discriminative thresholds the define the predictive results of a binary classification system [

61,

62]. A cell with probability value greater or lower than the discriminative threshold is predicted as a deposit or non-deposit. The sensitivity and specificity are computed by equations (2) and (3) [

63].

(3) Where TP represents a result that a deposit is correctly predicted as a deposit; FN means that a deposit is incorrectly predicted as a non-deposit; TN depicts a result that a non-deposit is correctly predicted as a non-deposit; FP represents a result that a non-deposit is incorrectly predicted as a deposit. The ROC curve is generated by plotting sensitivity on the y-axis against (1-specificity) on the x-axis at gradually decreasing discriminative thresholds. The closer the ROC curve towards the upper left corner, the better the model performs [

64]. Such criteria can be quantified by the area under the curve (AUC), which ranging from 0 (the poorest performance) to 1 (perfect prediction). The success rate is the ratio of the number of deposits contained in the targeting regions to the total number of deposits. The success-rate curve is generated by plotting the success rate on the y-axis against the area percentage of targeting regions on the x-axis at gradually decreasing discriminative thresholds.

In this study, the over-fitting of a predictive model is quantified by two indices, i.e., bias and variance. Bias is linked to the ability of a model to fit the labeled data of training dataset, while variance is related to the ability of a model to correlate with those labeled samples excluded from training dataset [

4,

65,

66]. Given that the AUC is used to assess overall predictive performance, the values of (1-AUC) calculated on the training and test dataset are used to estimate bias and variance, respectively. The difference between bias and variance can be regarded as a quantitative measurement of over-fitting [

66]. In order to measure the uncertainty of predictive results, 10-time randomly split of original data together with bootstrapping were implemented, resulting in 10 predictive models. The mean and standard deviation of predictive values in each cell were considered as modulated predictive values and quantitative uncertainty.

Information gain (IG) was used to quantify the contribution of each featured layer to the trained model, which can be calculated by the following formula [

67].

Where

Y is output class (deposit or non-deposit);

Fi represents a specific featured layer;

H(Y) is the entropy value of

Y;

H(Y|Fi) is the entropy value

Y after associating the feature values of

Fi (see [

67] for details).

4. Results

4.1. Data Imbalancing Analysis of SMOTE Augmentation

SMOTE was used in this study to augment minor positive samples for balancing the training dataset. In order to reveal the effectiveness of data augmentation and determine the optimum composition of training dataset, a grid search procedure was implemented on 182 SMOTE-ed training datasets involving variable over-sampling and under-sampling rates. The accuracies of trained models were calculated to measure their performance, as shown in

Figure 5a.

The models with the lowest accuracies are those trained by datasets with low positive over-sampling rates and high negative under-sampling rates, mostly occupying the upper left corner of the graph. In contrast, the models with the highest accuracies generally have high positive over-sampling rates, occurring in the right half of the graph. The impact of individual sampling rate on model performance was further delineated by statistical results of model accuracies that takes a specific positive over-sampling rate or negative under-sampling rate (

Figure 5b and

Figure 5c). The results indicate that the accuracies generally increase as the positive over-sampling rate increases, whereas the models’ performance becomes more unfavorable with the increasing of the negative under-sampling rate. More specifically, the rates of positive samples to negative samples were grouped into eight intervals to test reasonable positive/negative ratio employed in training dataset. The result indicates that the accuracies consistently increase as the positive/negative rate increases at the interval between 0.25 and 1, after which the models’ accuracies achieve a stably high level (

Figure 5d). Based on the above results, it suggests that models trained by datasets with high positive to negative ratios, i.e., greater than 1, tend to be more accurate and stable. In light of the criteria inferred from previous data-balancing studies [

17], 1:1 balanced positive and negative samples generalize better model performance. Therefore, a dataset including 228 positive samples and 209 negative samples, which yields the best model accuracy of 94.44% in this study (

Figure 5a), was employed to train the FSL models.

4.2. Assessment of Model Precision and Generalization

Random data-split procedure was iterated 10 times to create 10 different sub-datasets, which allows for measuring the overall performance and stochastic uncertainty of few-shot learning models in a robust way. RF and SVM models, served as benchmark models in this study, were also generated from 10 random selected training datasets. For each algorithm, the resulted probability and uncertainty values of 10 trained models were normalized to a [0, 1] range (

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10), allowing for a comparative analysis.

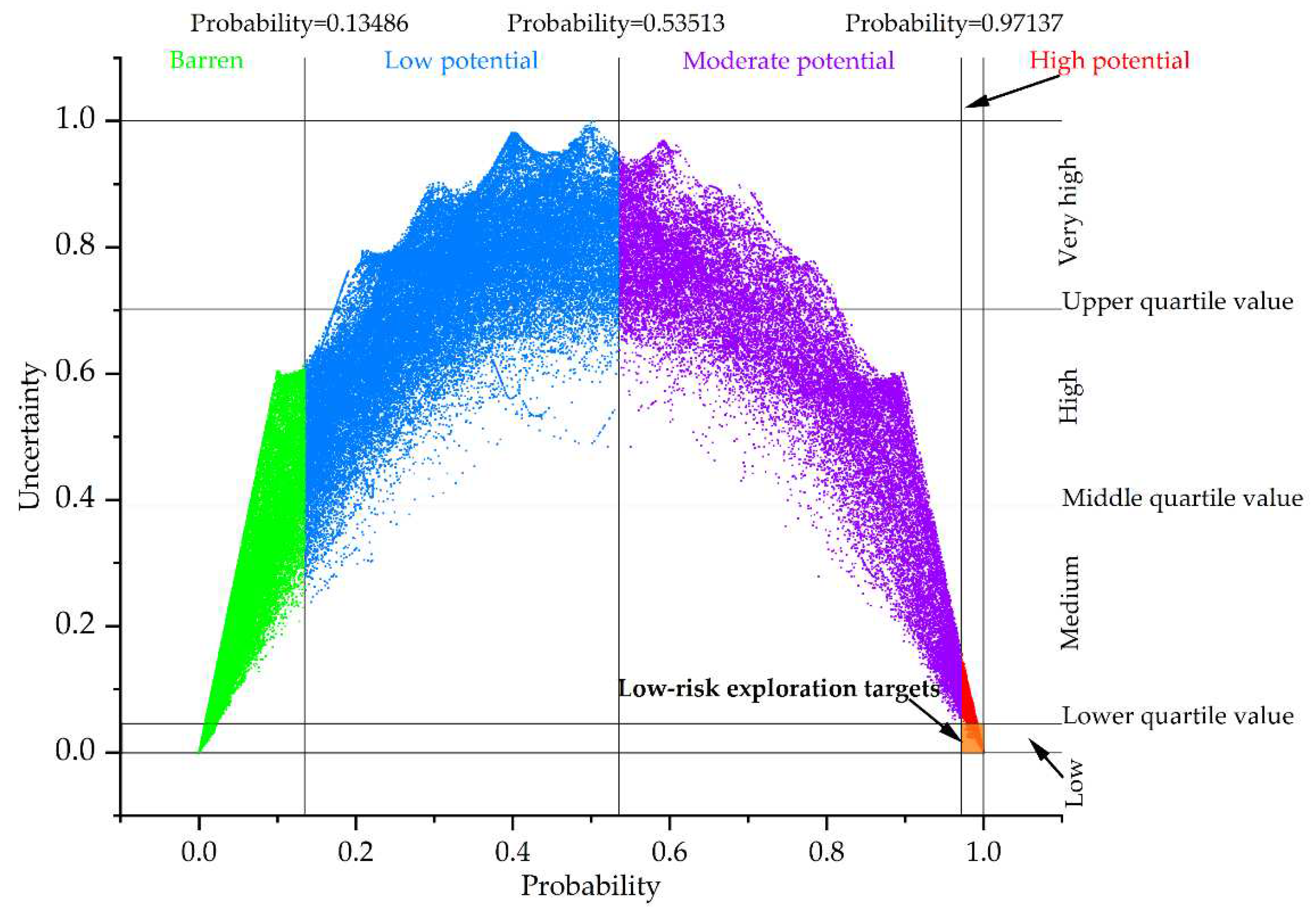

FSL and RF models output arch-shaped point patterns in the graph of uncertainty versus probability (Figures 7a and 8a). This pattern reflects that the cells with low uncertainty either have high mineralization probability or retain to low prospectivity zones, whereas those cells with moderate probability have high uncertainty. The points derived from SVM models are irregular. The cells with low uncertainty have varying probability values from 0 to 1, with no clustering trends towards to the lowest- or the highest-probability zones (

Figure 9a). For a mineral explorer, the arch-shaped point pattern is more favorable for the prospectivity mapping, since their attentions focus on high-probability cells, which are first-order targets of future exploration, as well as low-probability cells that should be excluded from target selection, while these focused cells with low uncertainty are deemed robust and low-risk targets.

The ROC curves for the three machine learning algorithms show marked differences (

Figure 7Figure 8 and

Figure 9). Two patterns of ROC curves are identified when the models are verified by training datasets, i.e., a perfect predictive curve with AUC equal to 1 (for RF and SVM models, shown in Figures 8b and 9b) and a step-shaped curve with AUC varying from 0.9 to 1 (for FSL models, shown in

Figure 7b). In contrast, all the three algorithms yield step-shaped curves when trained by test datasets. These patterns clearly show that RF and SVM models fall into the trap of over-fitting, which exhibits a perfect predictive performance on training datasets but fails to completely generalize over test datasets. Although the ROC curves of FSL models on both training and test datasets show step-shaped patterns, these models also suffer from over-fitting given that the AUCs of training datasets are greater than those of test datasets (Figures 7b,c). The over-fitting is quantified by bias and variance, as depicted in Figures 7d, 8d, 9d and

Table 1. RF models have the lowest average variance, implying the superior performance of RF models on test datasets (average AUC=0.9292), followed by FSL models which also achieve high AUCs on test datasets (average AUC=0.9172). FSL models have the lowest measured value of over-fitting (0.0313), which is far lower than that of RF (0.0708) and SVM models (0.1801).

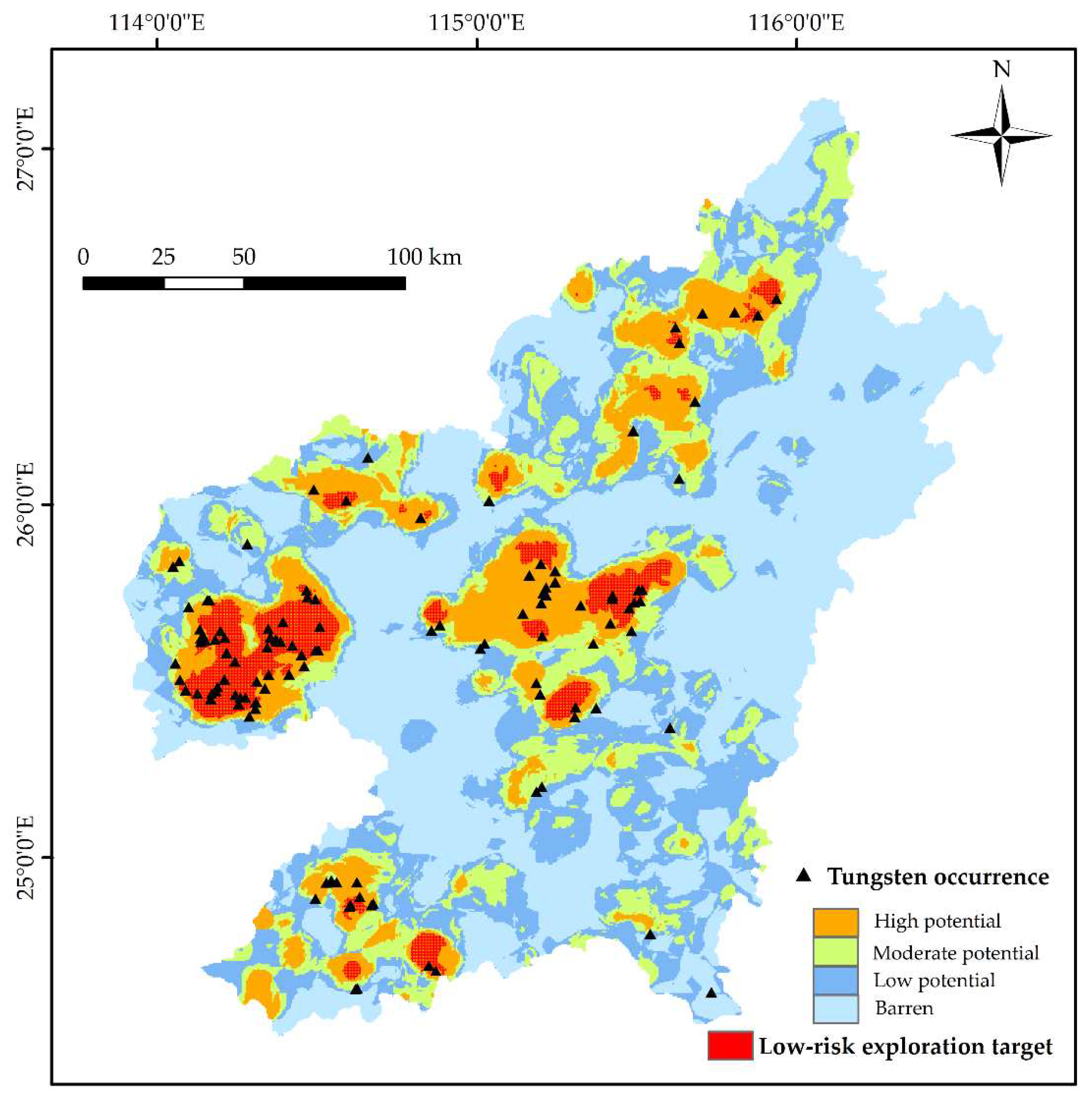

4.3. Targets of Predictive Modeling

Aiming to generate a robust prospectivity map with lowest uncertainty, the FSL models are chosen as final predictive models. However, it is still a challenging task to extract the optimal exploration targets from resulting FSL models. Excessively extensive prospective zones would greatly increase the exploration cost, whereas too limited targeting zones would reduce the success rate of prospecting. Therefore, predictive efficiency considering both success rate and delineated area is essential for the targeting task. A success-rate curve is employed here to measure the predictive efficiency of proposed models, as shown in

Figure 10. Four segments of success-rate curves are clearly identified, with fitting coefficients greater than 0.92. Given that the slope of the fitting curve indicates the ratio of successfully predicted deposits versus the delimited area, it can be employed as an effective means to quantify the predictive efficiency. The first segment of success-rate curve represents the predictive efficiency of those cells with top probabilities, thus reflecting the most important aspect of model’s predictive efficiency. The slope of the first segment of success-rate curve is 8.293, representing that 61.86% of known mineral deposits are captured within 7% of the study area. This result is superior to the best predictive efficiency of 6.7797 yielded from previous MPM modeling in this region [

9].

Different slopes of success-rate curves suggest different predictive efficiencies. Thus, the intersections of different segments of success-rate curves imply possible threshold values for classification of different prospectivity levels. In this regard, four levels of mineral prospectivity, namely high potential, moderate potential, low potential, and barren zones, are identified from

Figure 10, based on which a prospectivity map is generated (

Figure 11). Uncertainty is employed to further estimate the reliability of predictive results, reducing exploration risk. However, there is no common criteria for selecting threshold value for masking high uncertain cells [

4]. In this study, four levels of uncertainty, namely very high, high, medium and low, are determined based on the threshold values of three quartiles of uncertainty values. Considering both predictive efficiency and exploration risk, the final targets for future exploration fall on the cells with high potential and low uncertainty, as shown with the brown filled zone in

Figure 12. The final low-risk exploration targets only cover 4.27% of the area, but capture 41.53% of known tungsten deposits (

Figure 11), achieving the best predictive efficiency of 9.7155.

5. Discussion

The objective of MPM in this study is to generate a robust predictive model with low uncertainty, thus reducing the future exploration risk to the maximum extent. To achieve this goal, three aspects of scenarios have been implemented.

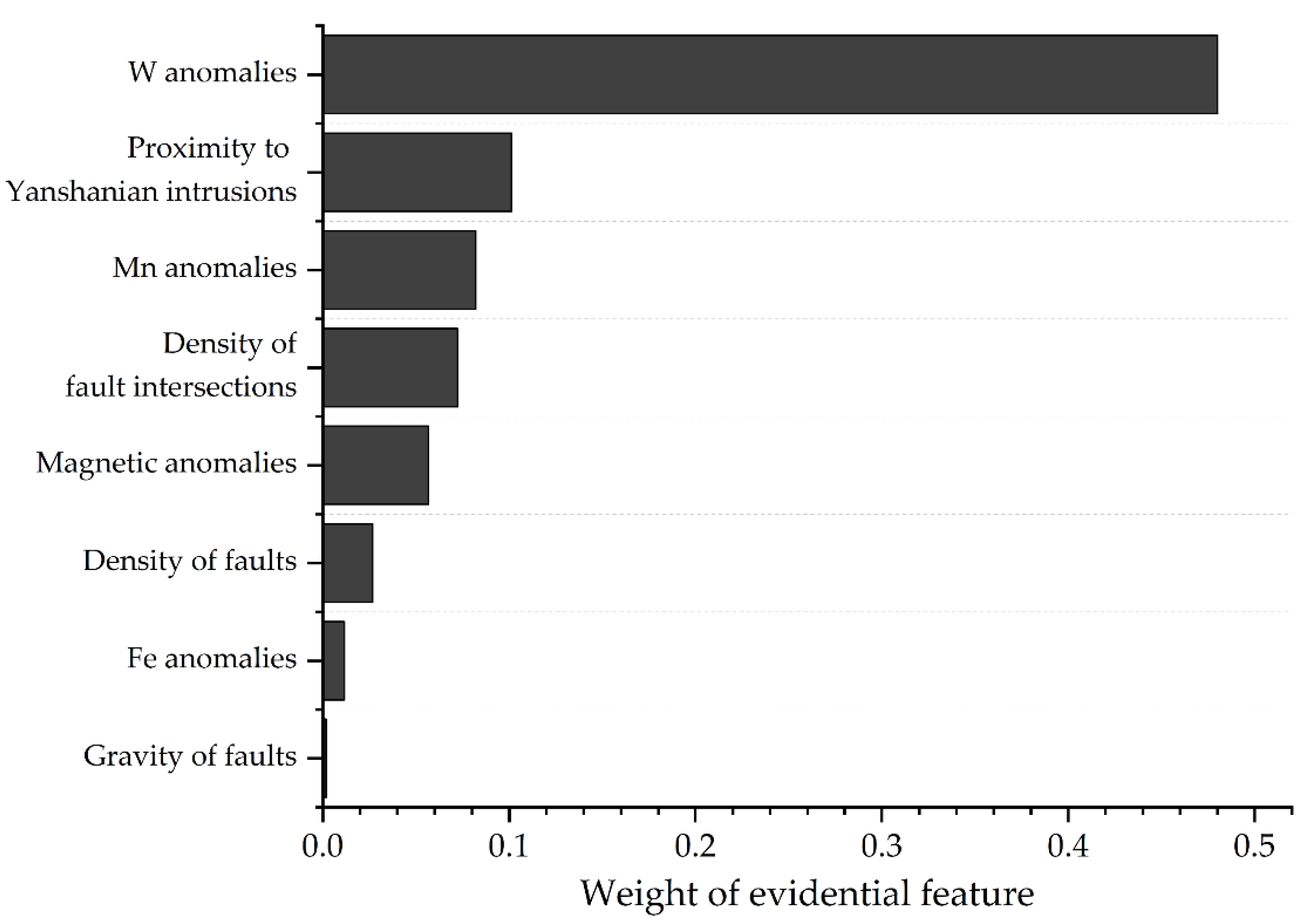

Geologically, the mineral systems approach was employed to translate our understanding of the tungsten mineral system into mappable exploration criteria, resulting in 8 evidential maps that represent source, transport, physical trap and chemical deposition processes critical for ore formation. The feature weights of evidential layers, measured by information gain, imply that most of selected evidences make major or significant contributions to the final predictions (

Figure 13). As a direct indication of targeted mineralization, W anomalies impose the greatest influence on the predictive results. Proximity to Yanshanian intrusions and density of fault intersections, corresponding to spatial proxies of ore-forming parent magmatic rocks and regional structural that have been well recognized as ore-controlling factors, exert important influences on the predictions. It is interesting to observe that Mn anomalies make equal contribution to prediction as above-mentioned well-recognized elements, which is consistent with our previous study [

9], implying that Mn derived from host rocks may exert a significant control on wolframite precipitation. Magnetic anomalies, fault density and Fe anomalies make secondary contributions to predictions. It is worth noting that gravity anomalies are interpreted to contribute little to predictive results, implying their failure in spatially representing buried intrusions. This arises a limitation problem of this study based on 2D maps, that is, lacking of evidential layers that can effectively portray ore-related processes at depth. Integrating such evidences in future work would improve the effectiveness of predictor maps and boost the performance of predictive models.

Algorithmically, a FSL framework jointly employing data augmentation and transferring was proposed, which appears to be effective for controlling the over-fitting regarding model assessment (

Figure 7 and

Table 1). On the one hand, 10-time random data split were implemented, and bootstrapping was carried out based on the augmented data derived from robust SMOTE algorithm. This multi-round random scenario not only provides a means for quantifying uncertainty and reducing fluctuation of predictive results, but also greatly increases the diversity of input datasets and pre-trained models, thus prevents the models from excessively over-fitting. On the other hand, the augmented synthetic data creates a data-rich source domain, meanwhile, they are intrinsically correlated with labeled data in the target domain, which benefits to transfer the knowledge obtained from source domain to the target domain, thereby enhancing the generalization capability of these models. In this regard, the FSL model is considered as the optimal one that can be well generalized for further exploration targeting.

Practically, this study employed the performance metrics linking predictive results to realistic mineral exploration activity. The confusion matrix-based indices are usually employed to assess the accuracy of binary classification. However, in this study, they are only used to rapidly measure the effect of parameter optimization, but are not taken into account for performance evaluation. The reason is that the confusion matrix of binary classification takes 0.5 as a common threshold. The cell greater or lower than 0.5 is labeled as positive or negative. In MPM field, such criterion leads to excessively extensive “favorable regions” (often beyond 30% of the study area), which conflicts with one of the basic principles of mineral exploration, that is, narrowing down the area of exploration targets. Instead, performance metrics based on varying discriminative thresholds, i.e., ROC curve and success-rate curve, are employed in this study, and attention is especially focused on the high-probability and low-uncertainty zones. The final targets, capturing 49 out of 118 known deposits within only 4.27% of the total area, allow for an efficient and realistic exploration plan for future tungsten prospecting in this area.

6. Conclusions

Prospectivity map generated from a robust modeling process is crucial for an efficient exploration targeting. In this study, a FSL framework, combining the mineral systems approach, SMOTE augmentation algorithm, transfer learning and performance metrics linking to realistic mineral exploration, was proposed and applied in tungsten prospectivity mapping of southern Jiangxi Province. The resulting predictive model generates an arch-shaped point distribution pattern in the scatter plot of probability and uncertainty, favorable for focusing potential targets with high probability and low uncertainty, and achieves a high AUC value of 0.9172 on test dataset, as well as yields the lowest quantitative over-fitting value compared to benchmark machine learning algorithms. The predictive results demonstrate the excellent performance of the proposed framework in controlling over-fitting and generating high-potential, low-risk exploration targets. The final exploration targets only cover 4.27% of the area, but capture 41.53% known tungsten deposits, providing significant reference for further tungsten prospecting in the study area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S.; methodology, K.Z., T.S., and Y.L.; validation, K.Z., and M.F.; formal analysis, W.P., and J.T.; investigation, Y.L., and K.Z.; resources, J.H., and L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Z., and T.S.; visualization, K.Z.; project administration, T.S.; funding acquisition, T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42062021); Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province for Distinguished Young Scholars (Grant No. 20224ACB218003); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2019M662267); Program of Qingjiang Excellent Young Talents, Jiangxi University of Science and Technology (Grant No. JXUSTQJBJ2020001); and Science and Technology Program of Ganzhou City (Grant No. 202101095156).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Carranza, E.J.M.; Laborte, A.G. Data-driven predictive mapping of gold prospectivity, Baguio district, Philippines: application of Random Forests algorithm. Ore Geol. Rev. 2015, 71, 777–787. [CrossRef]

- Daviran, M.; Maghsoudi, A.; Ghezelbash, R.; Pradhan,B. A new strategy for spatial predictive mapping of mineral prospectivity: Automated hyperparameter tuning of random forest approach. Comput. Geosci. 2021, 148. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R.G. Geodata Science-Based Mineral Prospectivity Mapping: A Review. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29, 3415-3424. [CrossRef]

- Parsa, M; Lentz, D.R.; Walker J.A. Predictive Modeling of Prospectivity for VHMS Mineral Deposits, Northeastern Bathurst Mining Camp, NB, Canada, Using an Ensemble Regularization Technique. Nat. Resour. Res. 2022, 32, 19-36. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, X.; Yuan, F.; Ord, A.; Jowitt, S.M.; Li, Y.; Dai, W.; Zhou, T. Numerical Modeling of Ore-forming Processes within the Chating Cu-Au Porphyry-type Deposit, China: Implications for the Longevity of Hydrothermal Systems and Potential Uses in Mineral Exploration. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 116, 103230. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, G.; Yang, H.; Luo, J.; Ren, K.; Yang, Y. Numerical modeling of formation of the Maoping Pb-Zn deposit within the Sichuan-Yunnan-Guizhou Metallogenic Province, southwestern China: implications for the spatial distribution of concealed Pb mineralization and its controlling factors. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 140, 104573. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, L. Quantitative 3D Association of Geological Factors and Geophysical Fields with Mineralization and Its Significance for Ore Prediction: An Example from Anqing Orefield, China. Minerals. 2018, 8, 300. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, G.; Chen, Y.; Luo, J.; Yang, H.; Yang, Y.; Ren, K.; Li, Y.; Gao, L. Combination model-based numerical simulation of the mineralizing processes within iron oxide-apatite systems. Ore Geol. Rev. 2023, 156, 105394. [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Li, H.; Wu, K.; Chen, F.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, Z. Data-Driven Predictive Modelling of Mineral Prospectivity Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Methods: A Case Study from Southern Jiangxi Province, China. Minerals. 2020, 10, 102. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R.G.; Wang, Z.Y. Effects of Random Negative Training Samples on Mineral Prospectivity Mapping. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29. [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Ye, R.; Yuan, F. Three-Dimensional Mineral Prospectivity Modeling for Delineation of Deep-Seated Skarn-Type Mineralization in Xuancheng–Magushan Area, China. Minerals 2022, 12, 1174. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Wei, H.; Xiao, K.; Yang, F.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, S.H.; Xu, Y. Data-driven Mineral Prospectivity Mapping by Joint Application of Unsupervised Convolutional Auto-encoder Network and Supervised Convolutional Neural Network. Nat. Resour. Res. 2021, 30. /: ttps.

- Silva dos Santos, V.; Gloaguen, E.; Hector Abud Louro, V.; Blouin, M. Machine Learning Methods for Quantifying Uncertainty in Prospectivity Mapping of Magmatic-Hydrothermal Gold Deposits: A Case Study from Juruena Mineral Province, Northern Mato Grosso, Brazil. Minerals 2022, 12, 941. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.Z.;Liu, L.M.; Wu, W.C. Machine Learning-Based 3D Modeling of Mineral Prospectivity Mapping in the Anqing Orefield, Eastern China. Natural Resources Research. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29. [CrossRef]

- Porwal, A.; Carranza, E.J.M. Introduction to the special issue: GIS-based mineral potential modelling and geological data analyses for mineral exploration. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2015, 71, 477–483. [CrossRef]

- odriguez-Galiano, V.; Sanchez-Castillo, M.; Chica-Olmo, M.; Chica-Rivas, M. Machine learning predictive models for mineral prospectivity: An evaluation of neural networks, random forest, regression trees and support vector machines. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2015, 71, 804–818. [CrossRef]

- Prado, E.M.G.; Filho, C.R.S.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Motta, J.G.M. Modeling of Cu-Au prospectivity in the Carajás mineral province (Brazil) through machine learning: Dealing with imbalanced training data. Ore Geol. Rev. 2020, 184, 103611. [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Chen, F.; Zhong, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y. GIS-based mineral prospectivity mapping using machine learning methods: A case study from Tongling ore district, eastern China. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2019, 109, 26–49. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R.G.; Kreuzer, O.P.; Wang, J.;Xiong, Y.H.;Zhang, Z.J.; Wang, Z.Y. Uncertainties in GIS-Based Mineral Prospectivity Mapping: Key Types, Potential Impacts and Possible Solutions. Nat. Resour. Res. 2021, 30. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Zhao, Z.B.; Sun, C.; Yan, R.Q.; Chen, X.F. Few-shot transfer learning for intelligent fault diagnosis of machin. Measurement. 2020, 166, 108202. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, Z.R.; Li, H.; Li, H.C.; Fu, K. Research Progress on Few-Shot Learning for Remote Sensing Image Interpretation. IEEE. J-Stars. 2021,14. [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, S.; Tirodkar, S.; Porwal, A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Joly, A. Random Forest-Based Prospectivity Modelling of Greenfield Terrains Using Sparse Deposit Data: An Example from the Tanami Region, Western Australia. Nat. Resour. Res. 2017, 26, 489–507. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xia, Q.; Zhao, M.; Gui, Z.; Leng, S. Prospectivity Mapping for Tungsten Polymetallic Mineral Resources, Nanling Metallogenic Belt, South China: Use of Random Forest Algorithm from a Perspective of Data Imbalance. Nat. Resour. Res. 2019, 29, 203-22. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, X.H.; Yuan, F.; Jowitt, S.M.; Zhang, M.M.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, T.F.; Li, X.L.; Ge, C.; Wu, B.C. Convolutional neural network and transfer learning based mineral prospectivity modeling for geochemical exploration of Au mineralization within the Guandian–Zhangbaling area, Anhui Province, China. Appl. Geochem. 2020, 122, 104747. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.C.; Li, X.H.; Yuan, F.; Li, H.; Zhang, M.M. Transfer learning and siamese neural network based identification of geochemical anomalies for mineral exploration: A case study from the Cu–Au deposit in the NW Junggar area of northern Xinjiang Province, China. J. Geochem. Explor. 2022, 232, 106904.

- Ding, K.; Xue, L.F.; Ran, X.J.; Wang, J.B.; Yan, Q. Siamese network based prospecting prediction method: A case study from the Au deposit in the Chongli mineral concentrate area in Zhangjiakou, Hebei Province, China. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2022, 148, 105024. [CrossRef]

- Feng, C. Y.; Zeng, Z.L.; Zhang, W.J.; Qu, W.J.; Du, A.D.; Li, D. X.; She, H.Q. SHRIMP zircon U–Pb and molybdenite Re–Os isotopic dating of the tungsten deposits in the Tianmenshan–Hongtaoling W–Sn orefield, southern Jiangxi Province, China, and geological implications. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2011, 43, 8–25.

- Mao, J.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, M.; Pirajno, F. Major types and time–space distribution of Mesozoic ore deposits in south China and their geodynamic settings. Miner. Depos. 2013, 48, 267–294.

- Feng, C.; Zhang, D.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, S. Chronology of the tungsten deposits in southern Jiangxi Province, and episodes and zonation of the regional W-Sn mineralization-evidence from high-precision zircon U-Pb, molybdenite Re-Os and muscovite Ar-Ar ages. Acta. Geol. Sin-Engl. 2012, 86, 555–567.

- Fang, G.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, X.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, Y. Geophysical investigations of the geology and structure of the Pangushan-Tieshanlong tungsten ore field, South Jiangxi, China—Evidence for site-selection of the 2000m Nanling scientific drilling project (SP-NLSD-2). J. Asian. Earth. Sci. 2015, 110, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- GeoCloud Database of China Geological Survey. Available online: http://geocloud.cgs.gov.cn (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Wyborn, L.A.I.; Heinrich, C.A.; Jaques, A.L. Australian Proterozoic mineral systems: essential ingredients and mappable criteria, Australia. Inst. Min. Metall. Publ. Ser. 1994, 5, 109–115.

- Kreuzer, O.P.; Miller, A.V.M.; Peters, K.J.; Payne, C.; Wildman, C.; Partington, G.A.; Puccioni, E.; McMahon, M.E.; Etheridge, M.A. Comparing prospectivity modelling results and past exploration data: A case study of porphyry Cu–Au mineral systems in the Macquarie Arc, Lachlan Fold Belt, New South Wales. Ore Geol. Rev. 2015, 71, 516–544.

- Hagemann, S.G.; Lisitsin, V.A.; Huston, D.L.; Mineral system analysis: Quo vadis. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 76, 504–522. [CrossRef]

- McCuaig, T.C.; Beresford, S.; Hronsky, J. Translating the mineral systems approach into an effective exploration targeting system. Ore Geol. Rev. 2010, 38, 128–138.

- Yang, J.H.; Kang, L.F.; Peng, J.T.; Zhong, H.; Gao, J.F.; Liu, L. In-situ elemental and isotopic compositions of apatite and zircon from the Shuikoushan and Xihuashan granitic plutons: Implication for Jurassic granitoid-related Cu-Pb-Zn and W mineralization in the Nanling Range, south China. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2018, 93, 382–403. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Kang, L.F.; Liu, L.; Peng, J.T.; Qi, Y.Q. Tracing the origin of ore-forming fluids in the Piaotang tungsten deposit, south China: Constraints from in-situ analyses of wolframite and individual fluid inclusion. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2019, 111, 102939. [CrossRef]

- eng, C.; Zhang, D.; Zeng, Z.;Wang, S. Chronology of the tungsten deposits in southern Jiangxi Province, and episodes and zonation of the regionalW-Sn mineralization-evidence from high-precision zircon U-Pb, molybdenite Re-Os and muscovite Ar-Ar ages. Acta. Geol. Sin-Engl. 2012, 86, 555–567. 86.

- Zhao, W.W.; Zhou, M.F.; Li, Y.H.M.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, J.F. Genetic types, mineralization styles, and geodynamic settings of Mesozoic tungsten deposits in south China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 137, 109–140. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Dong, C.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, H.; Fu, J.; Wang, C.; Shan, Y. Zircon U–Pb, molybdenite Re–Os and muscovite Ar–Ar isotopic dating of the XitianW–Sn polymetallic deposit, eastern Hunan Province, south China and its geological significance. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2016, 78, 85–100.

- Nanling Range Group of Ministry of Geology and Mineral Resources. Study on Regional Tectonic Characteristics and Ore-Forming Structures in the Nanling Range; Geology Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1988; pp. 102-134. (In Chinese).

- Joly, A.; Porwal, A.; McCuaig, T.C. Exploration targeting for orogenic gold deposits in the Granites-Tanami Orogen: mineral system analysis, targeting model and prospectivity analysis. Ore Geol. Rev. 2012, 48, 349–383. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fu, J. Geochemical Maps of Nanling Range; China University of Geoscience Press: Wuhan, China; 2012, pp. 50-109. (In Chinese).

- Xie, X.J.; Mu, X.Z.; Ren, T.X. Geochemical mapping in China. J. Geochem. Explor. 1997, 60, 99–113.

- Carranza, E.J.M. Objective selection of suitable unit cell size in data-driven modeling of mineral prospectivity. Comput. Geosci. 2009, 35, 2032–2046. [CrossRef]

- Hengl, T. Finding the right pixel size. Comput. Geosci. 2006, 32, 1283–1298. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R.; Carranza, E.J.M. Support vector machine: A tool for mapping mineral prospectivity. Comput. Geosci. 2011, 37, 1967–1975.

- Carranza, E.J.M.; Hale, M.; Faassen, C. Selection of coherent deposit-type locations and their application in data-driven mineral prospectivity mapping. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2008, 33, 536–558. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [CrossRef]

- Shahinfar, S.; Al-Mamun, H.A.; Park, B.; Kim, S.; Gondro, C. Prediction of marbling score and carcass traits in Korean Hanwoo beef cattle using machine learning methods and synthetic minority oversampling technique. Meat Sci. 2020, 161, 107997. [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, S.; Tirodkar, S.; Porwal, A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Joly, A. Random Forest-Based Prospectivity Modelling of Greenfield Terrains Using Sparse Deposit Data: An Example from the Tanami Region, Western Australia. Nat. Resour. Res. 2017, 26. [CrossRef]

- Sohrawordi, M.; Hossain, M.A. Prediction of lysine formylation sites using support vector machine based on the sample selection from majority classes and synthetic minority over-sampling techniques. Biochimie 2022, 192, 125-135.

- Jia, S.; Jiang, S.G.; Lin, Z.J.; Meng, X.; Yu, S.Q. A survey: Deep learning for hyperspectral image classification with few labeled samples. Neurocomputing 2021, 448, 179-204. [CrossRef]

- Carranza, E.J.M.; van Ruitenbeek, F.J.A.; Hecker, C.; van der Meijde, M.; van der Meer, F.D. Knowledge-guided data-driven evidential belief modeling of mineral prospectivity in Cabo de Gata, SE Spain. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2008 10, 374–387. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. 2001; 45, 5–32.

- Carranza, E.J.M.; Laborte, A.G. Data-driven predictive mapping of gold prospectivity, Baguio district, Philippines: application of Random Forests algorithm. Ore Geol. Rev. 2015, 71, 777–787. [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory. Springer-Verlag; 2000, pp. 302-314.

- Shabankareh, M.; Hezarkhani, A. Application of support vector machines for copper potential mapping in Kerman region. Iran. J. Afr. Earth. Sci. 2017, 128, 116–126. [CrossRef]

- Mahvash Mohammadi, N.; Hezarkhani, A. Application of support vector machine for the separation of mineralised zones in the Takht-e-Gonbad porphyry deposit, SE Iran. J. Afr. Earth. Sci. 2018, 143, 301–308. [CrossRef]

- Asadi, H.H.; Hale, M. A predictive GIS model for mapping potential gold and base metal mineralization in Takab area, Iran. Comput. Geosci. 2001, 27, 901–912. [CrossRef]

- Nykänen, V.; Lahti, I.; Niiranen, T.; Korhonen, K. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) as validation tool for prospectivity models—A magmatic Ni–Cu case study from the Central Lapland Greenstone Belt, Northern Finland. Ore. Geol. Rev. 2015, 71, 853–860.

- Nykänen, V.; Niiranen, T.; Molnár, F.; Lahti, I.; Korhonen, K.; Cook, N.; Skyttä, P. Optimizing a knowledge-driven prospectivity model for gold deposits within Peräpohja Belt, Northern Finland. Nat. Resour. Res. 2017, 26, 571–584.

- Liu, C.; Berry, P.M.; Dawson, T.P.; Pearson, R.G. Selecting thresholds of occurrence in the prediction of species distributions. Ecography. 2005, 28, 385–393. [CrossRef]

- Truong, X.; Mitamura, M.; Kono, Y.; Raghavan, V.; Yonezawa, G.; Truong, X.; Do, T.; Tien Bui, D.; Lee, S. Enhancing prediction performance of landslide susceptibility model using hybrid machine learning approach of bagging ensemble and logistic model tree. Sn.Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1046. [CrossRef]

- Parsa, M.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Ahmadi, B. Deep GMDH Neural Networks for Predictive Mapping of Mineral Prospectivity in Terrains Hosting Few but Large Mineral Deposits. Nat. Resour. Res. 2021, 31. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Johnson, K. Applied predictive modeling. SpringerLink; 2013, pp. 13-26.

- Tien Bui, D.; Ho, T.C.; Pradhan, B.; Pham, B.T.; Nhu, V.H.; Revhaug, I. GIS-based modelling of rainfall-induced landslides using data mining-based functional trees classifier with AdaBoost, Bagging, and MultiBoost ensemble frameworks. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1101.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).