Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Examine different machine learning techniques to determine how effectively they detect, classify, and extract sand and gravel surface mines from sentinel images.

- Build a classification model set that can be used regionally for surface monitoring of mining sites.

- Use classified images from the model and perform change detection analysis of the study areas over a five-year period (2015 to 2019)

- Utilize the built model to calculate the area of mining sites for the five study areas over the five-year period.

2. Materials and Methods

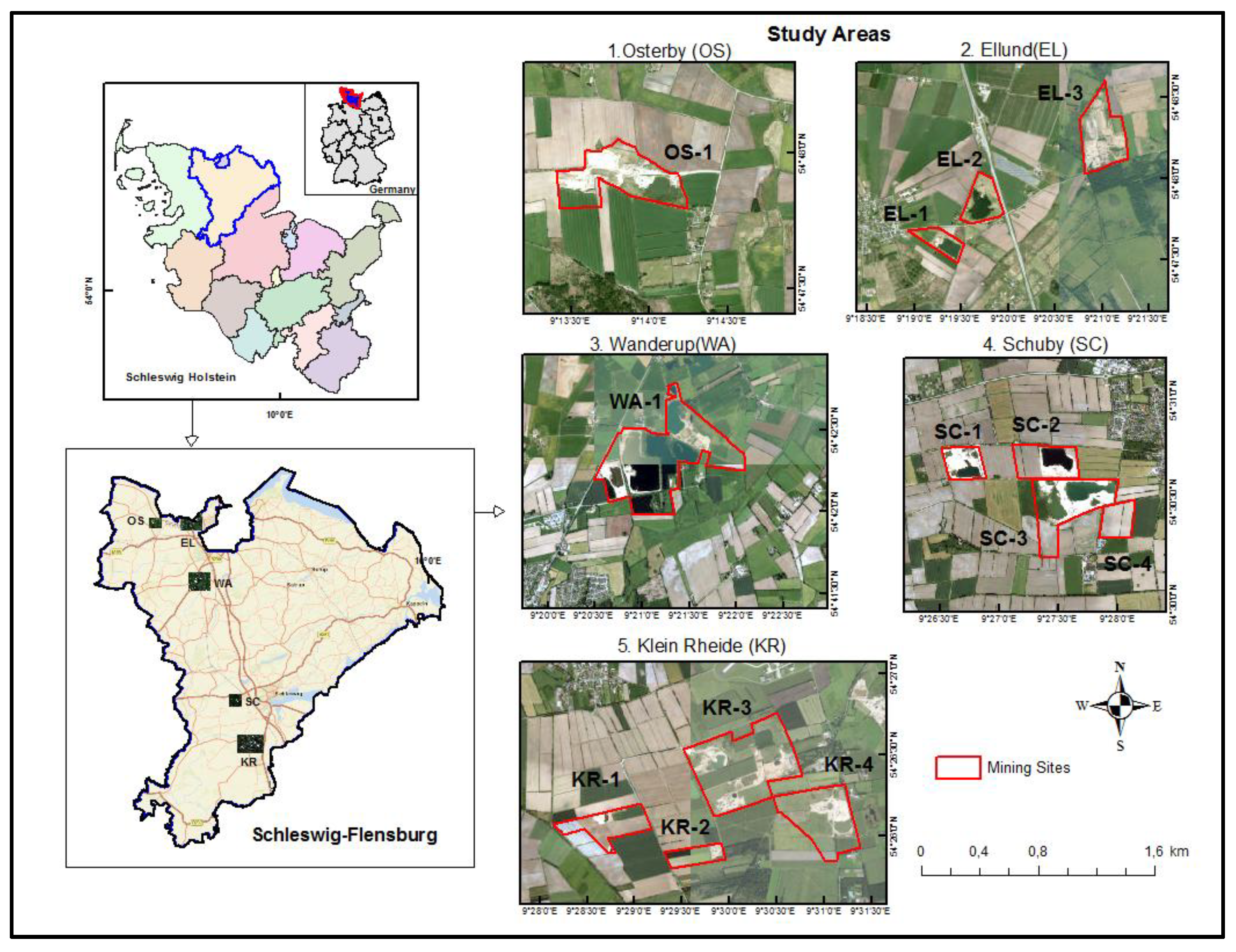

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Sentinel Data

2.2.2. Ancillary Data

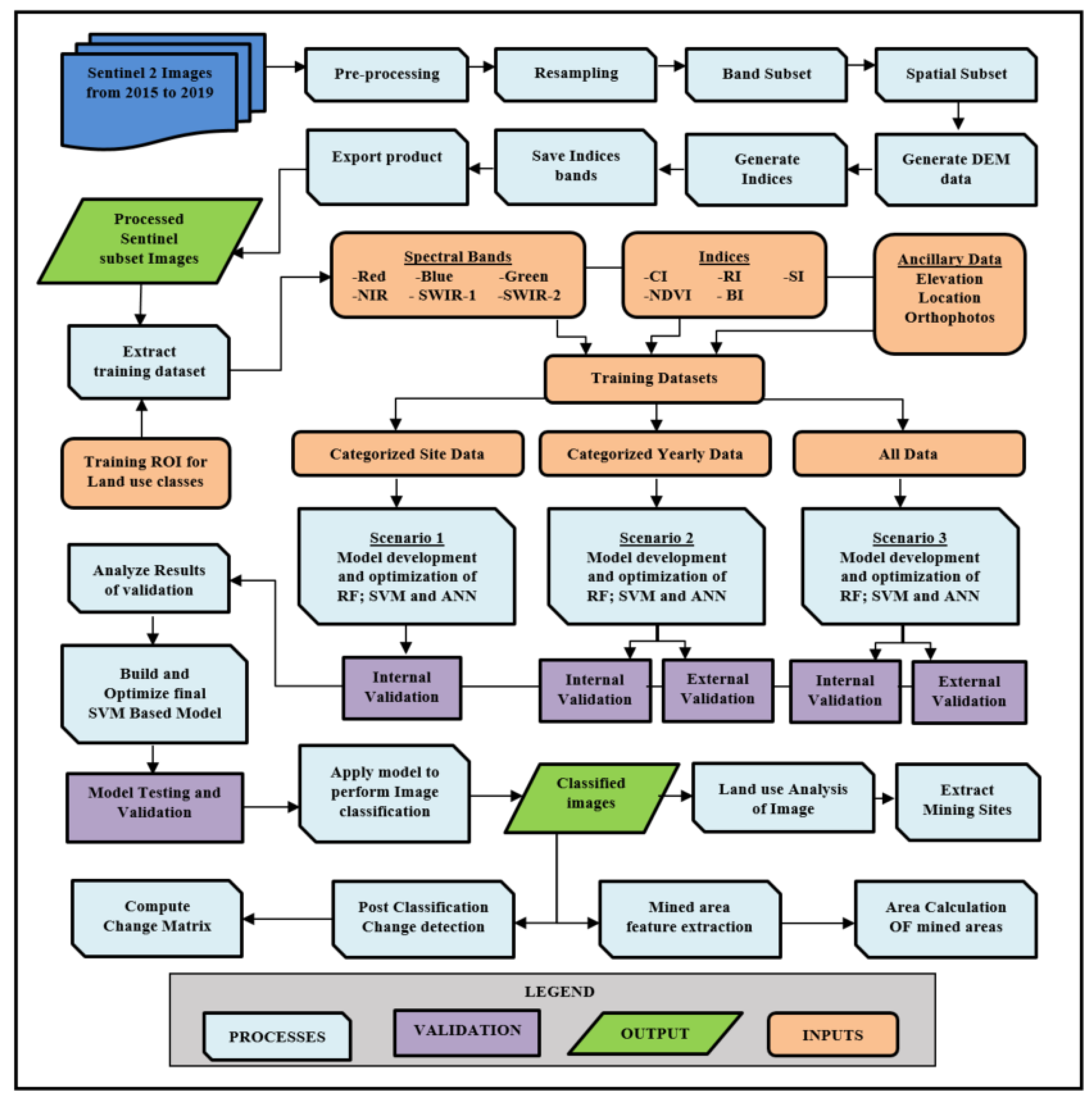

2.3. Data Processing

2.3.1. Sentinel Data Pre-Processing

2.3.2. Machine Learning Algorithms

2.3.3. Training Samples and Trials for Model Development

2.3. Model Set-Ups and Calibration

2.3.1. Model Set-Up of Machine Learning Classifiers

2.3.2. Calibration and Validation of RF, SVM, and ANN Classifiers

2.3.3. Accuracy Assessment

2.4. Classification of Images

2.5. Post-Classification Change Detection and Area Calculations

3. Results

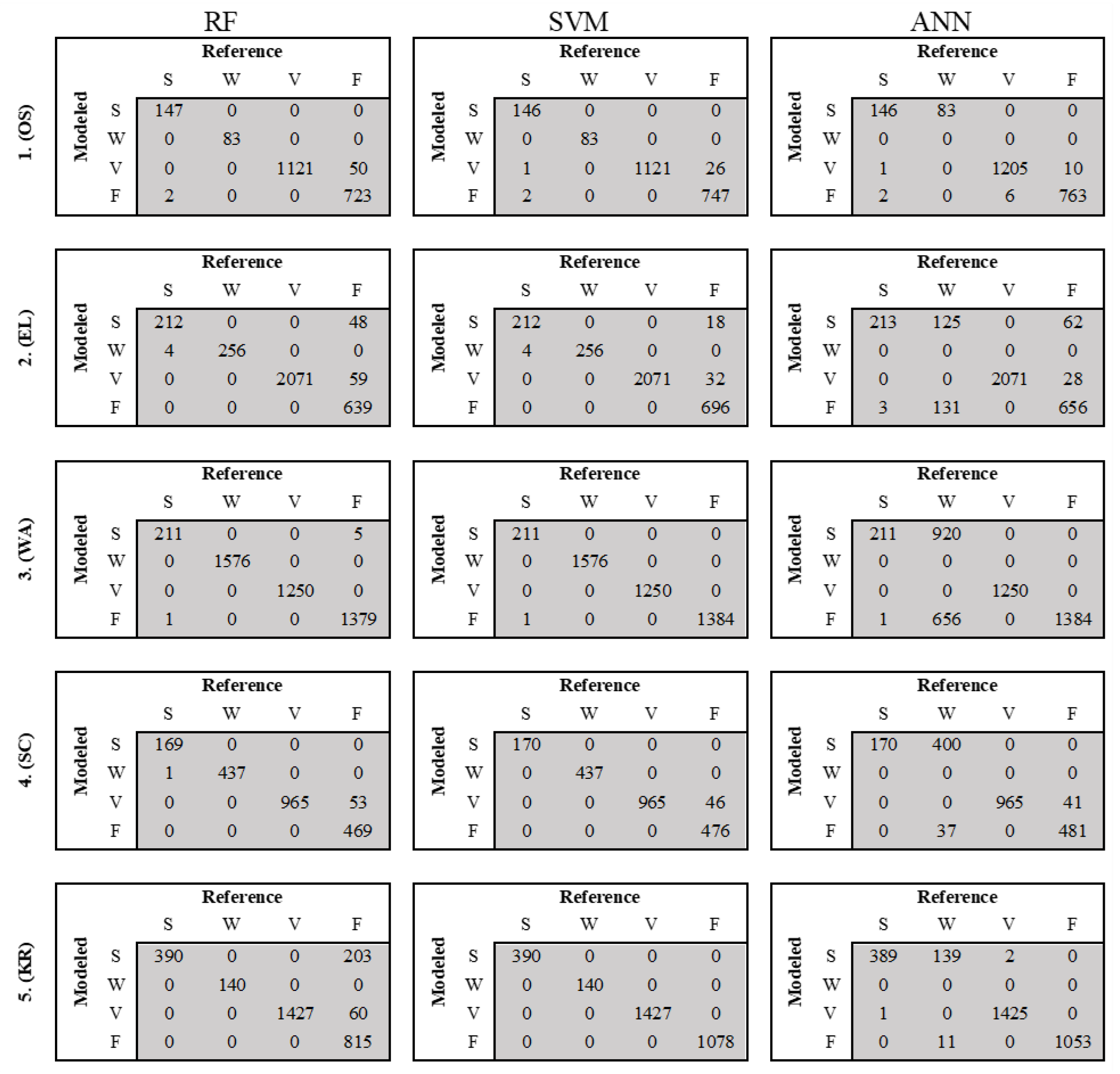

3.1. Accuracy Performance and Visual Assessment of Models Specific to Study Areas

3.1.1. Accuracy Performance of Models

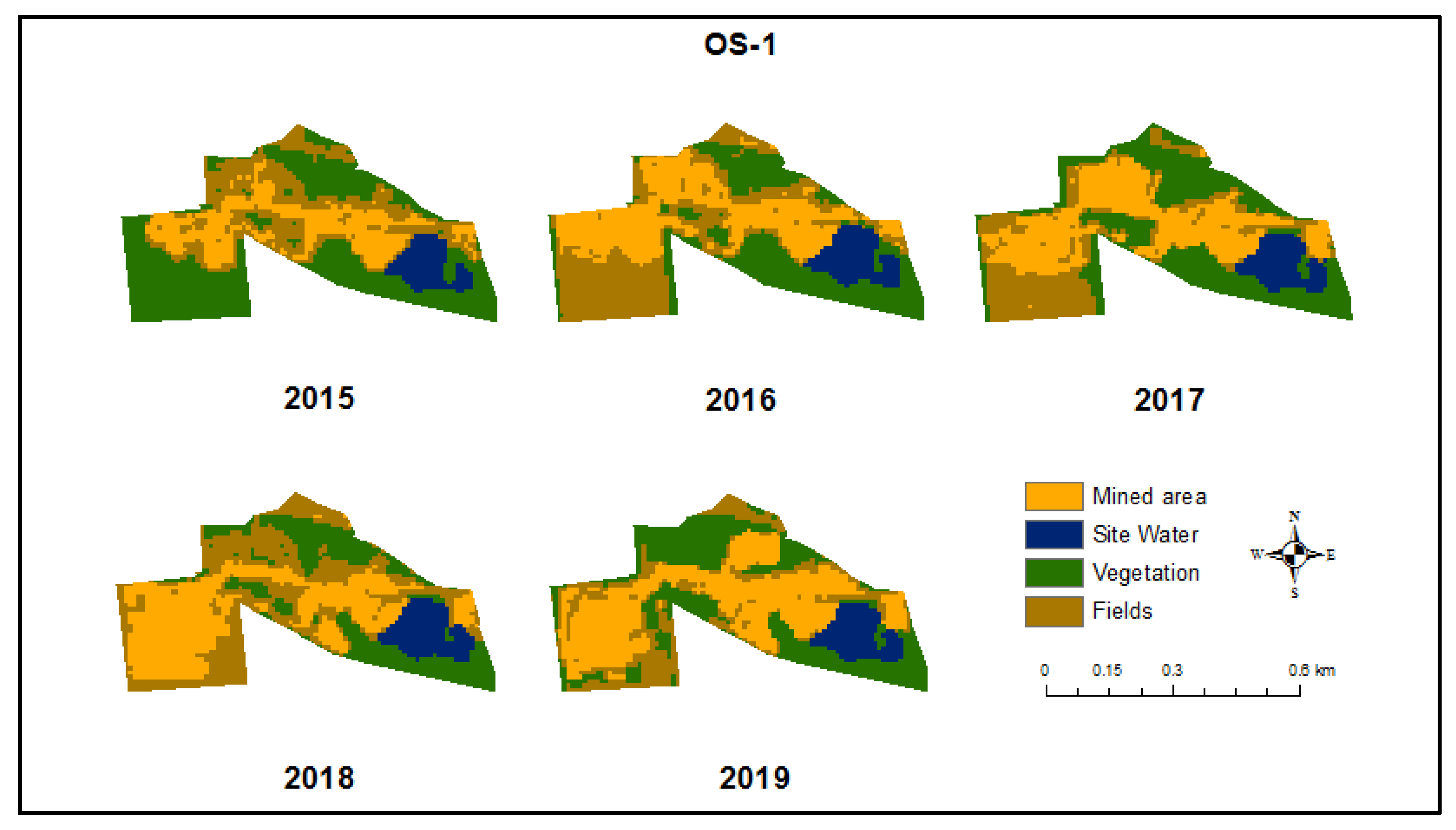

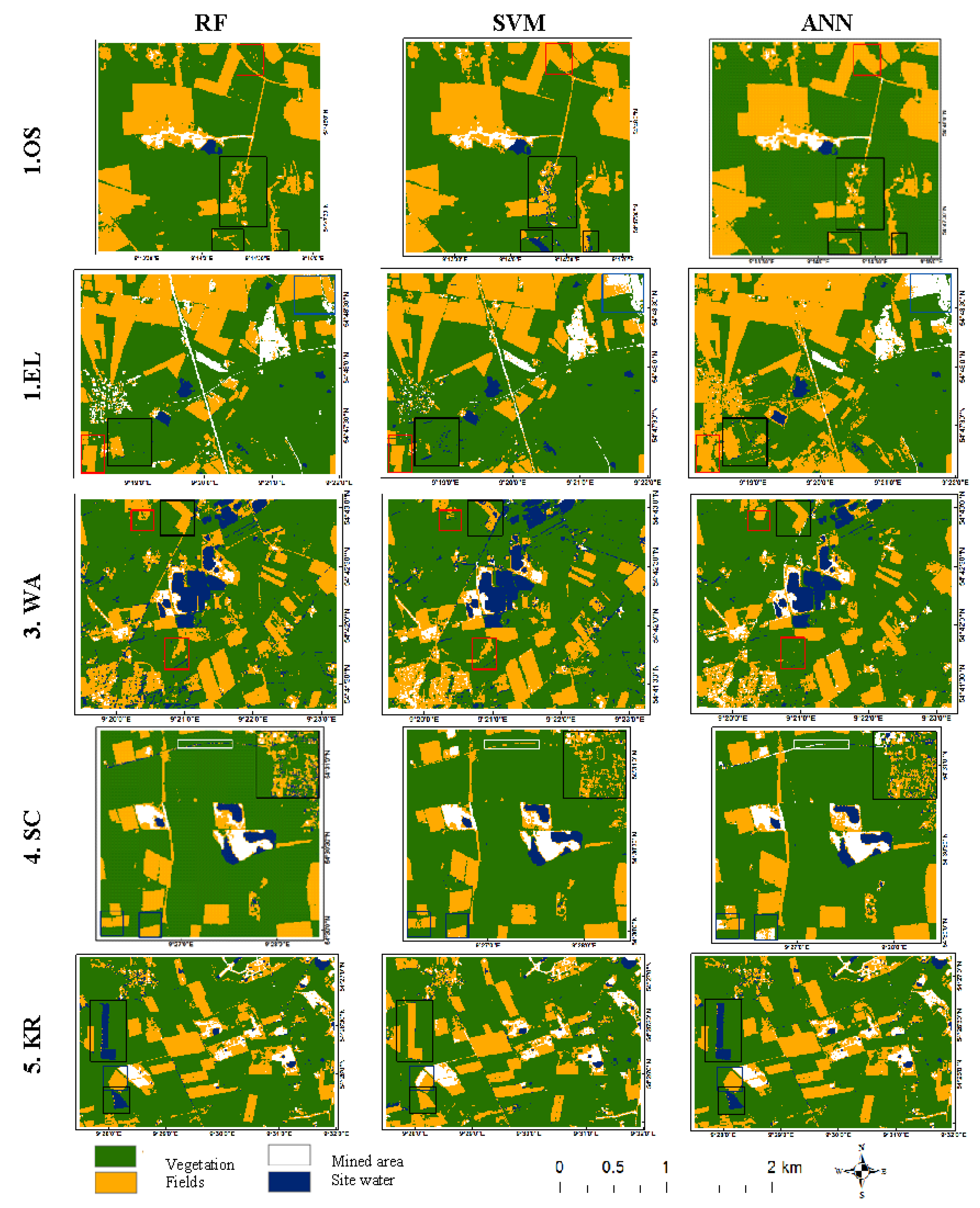

3.1.2. Visual Assessment of Classification Results

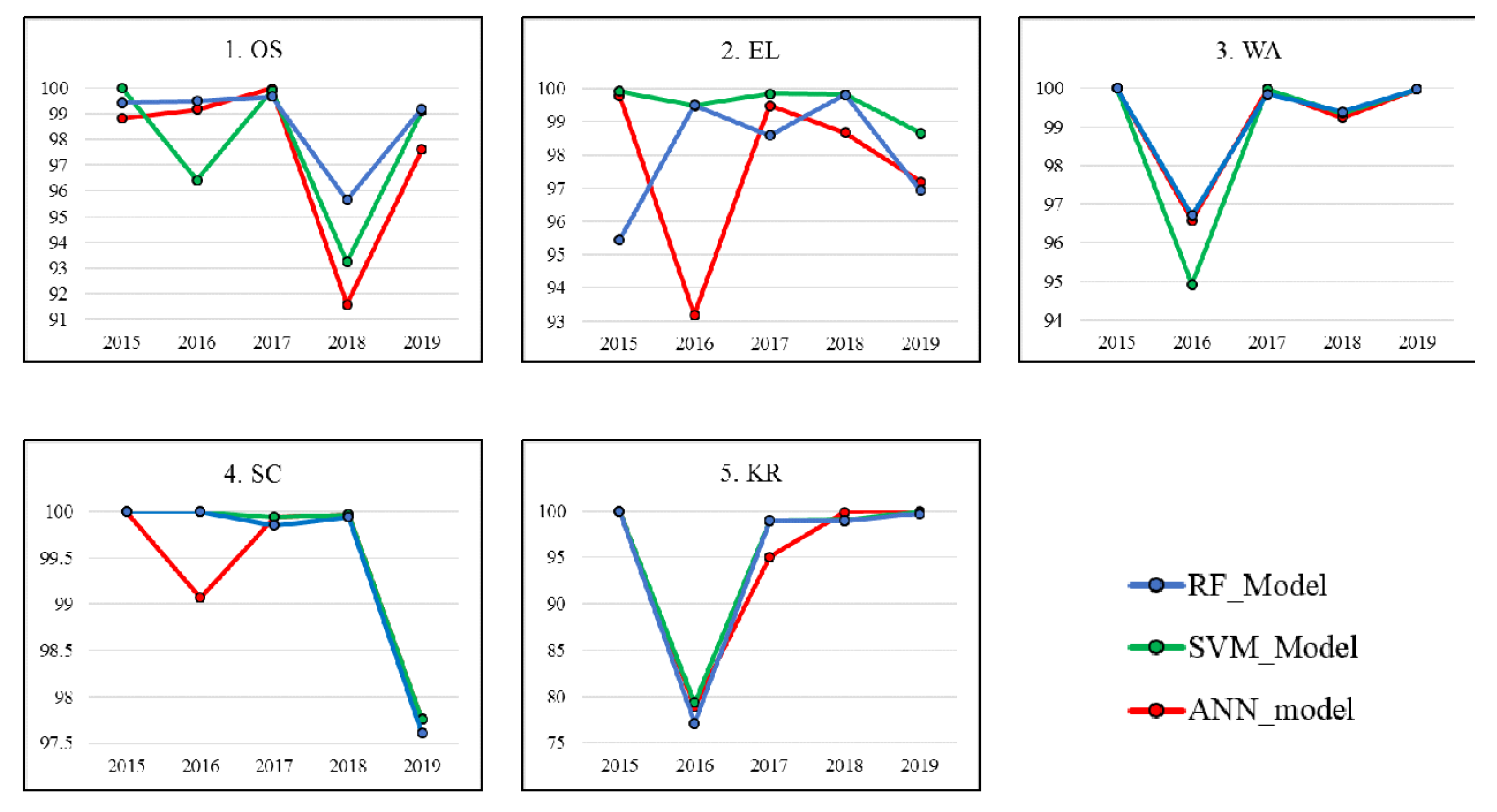

3.2. Accuracy Performance of Models Specific to Years

3.2.1. Internal Validation

3.2.2. External Validation

3.3. Accuracy Performance of Overall Model

3.3.1. Internal Accuracy Statistics

3.3.2. External Accuracy

3.4. Classification Results and Performance with Support Vector Machine Model

3.4.1. External Accuracy

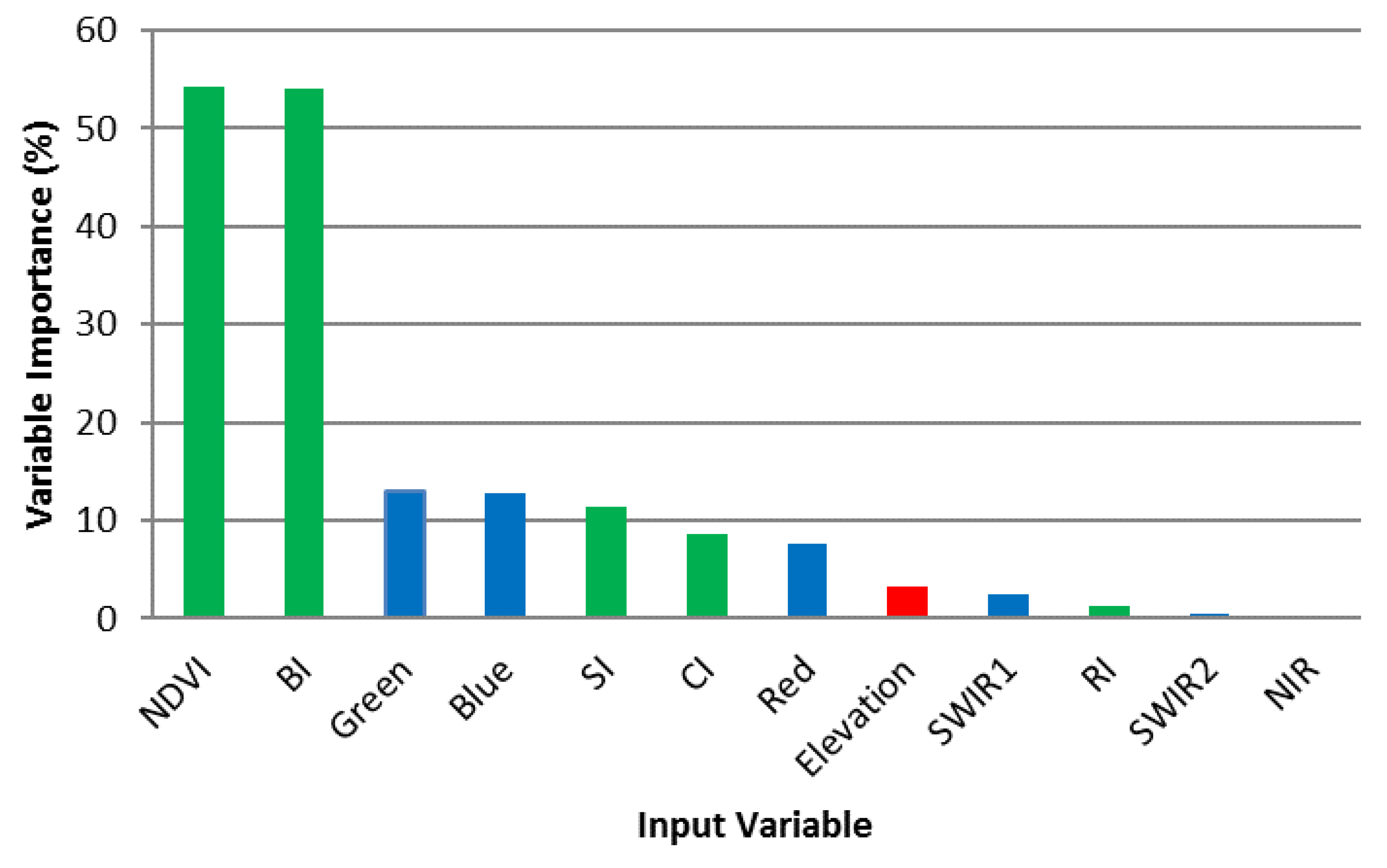

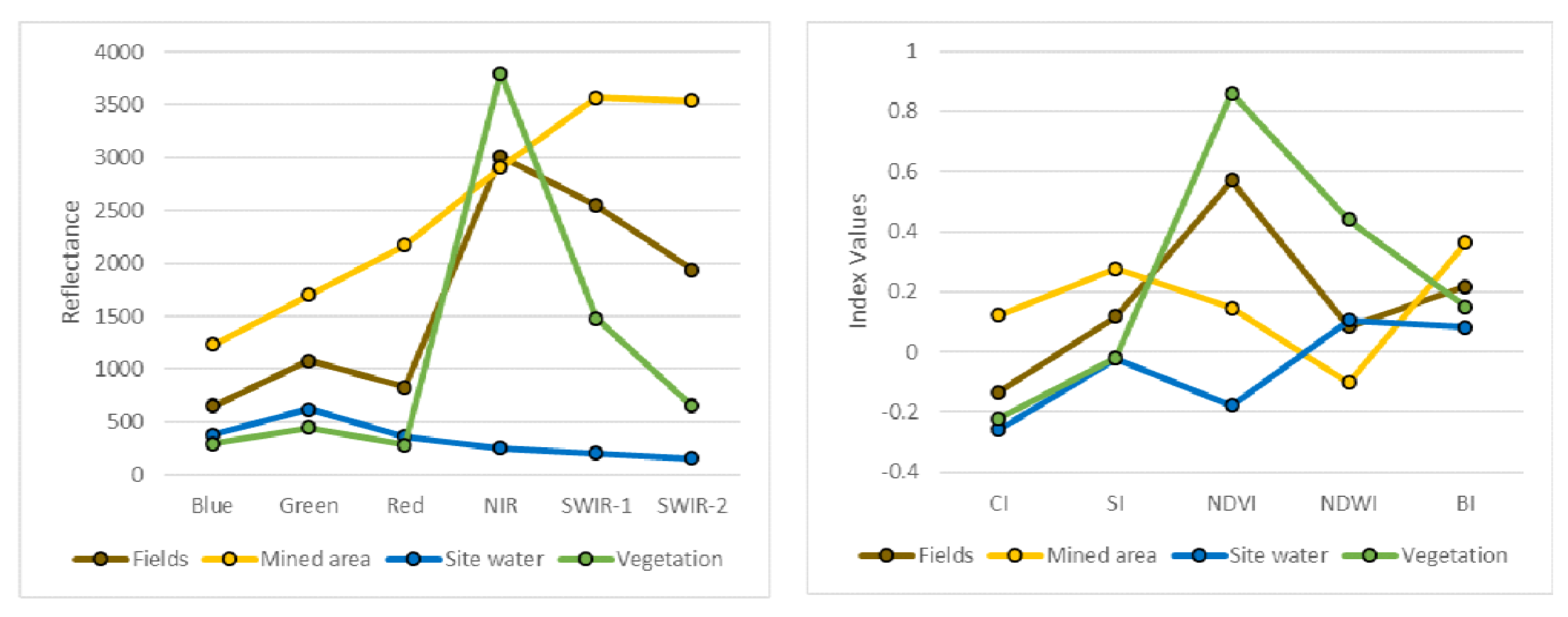

3.4.2. Variable Influence on Classification

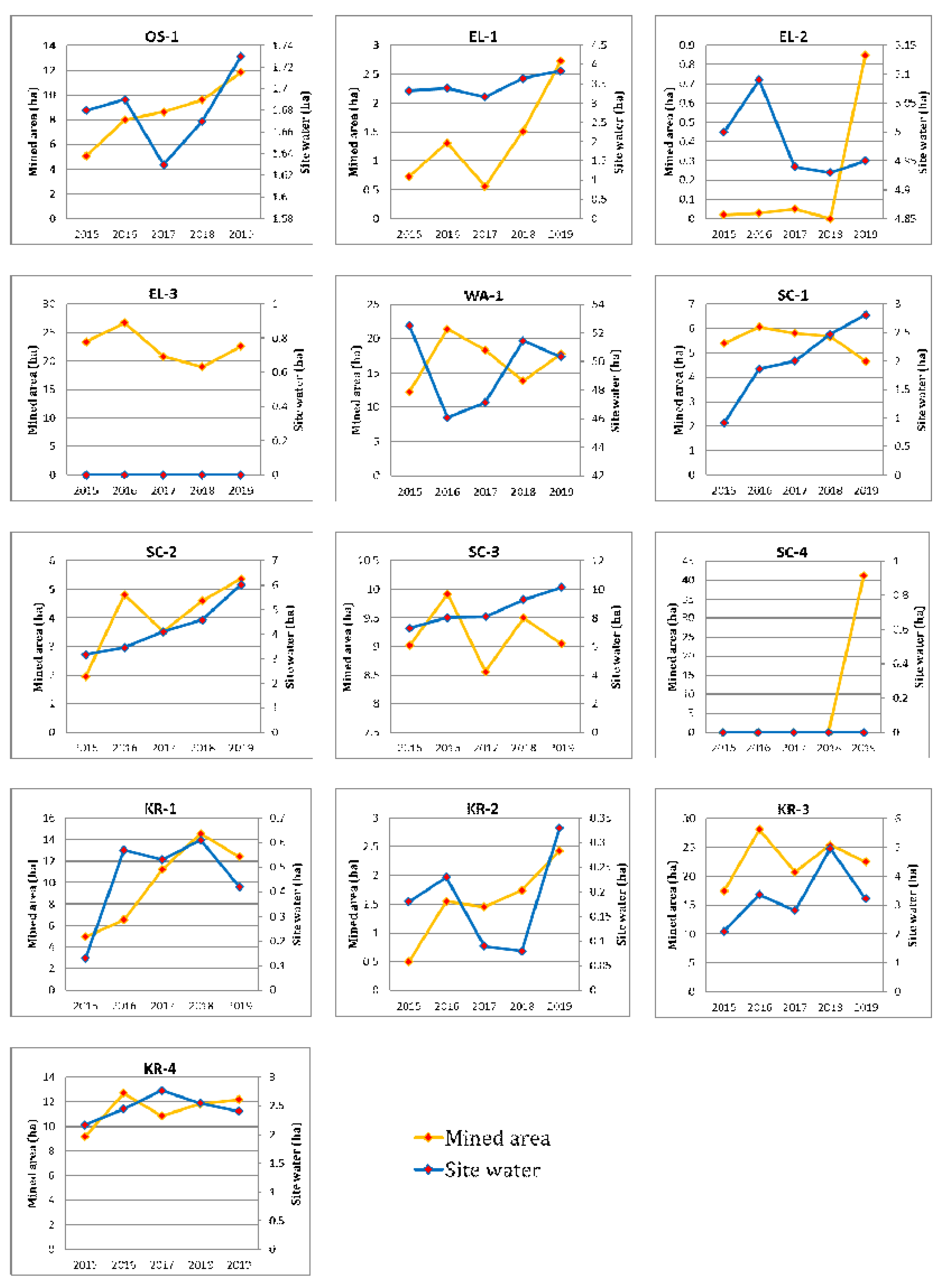

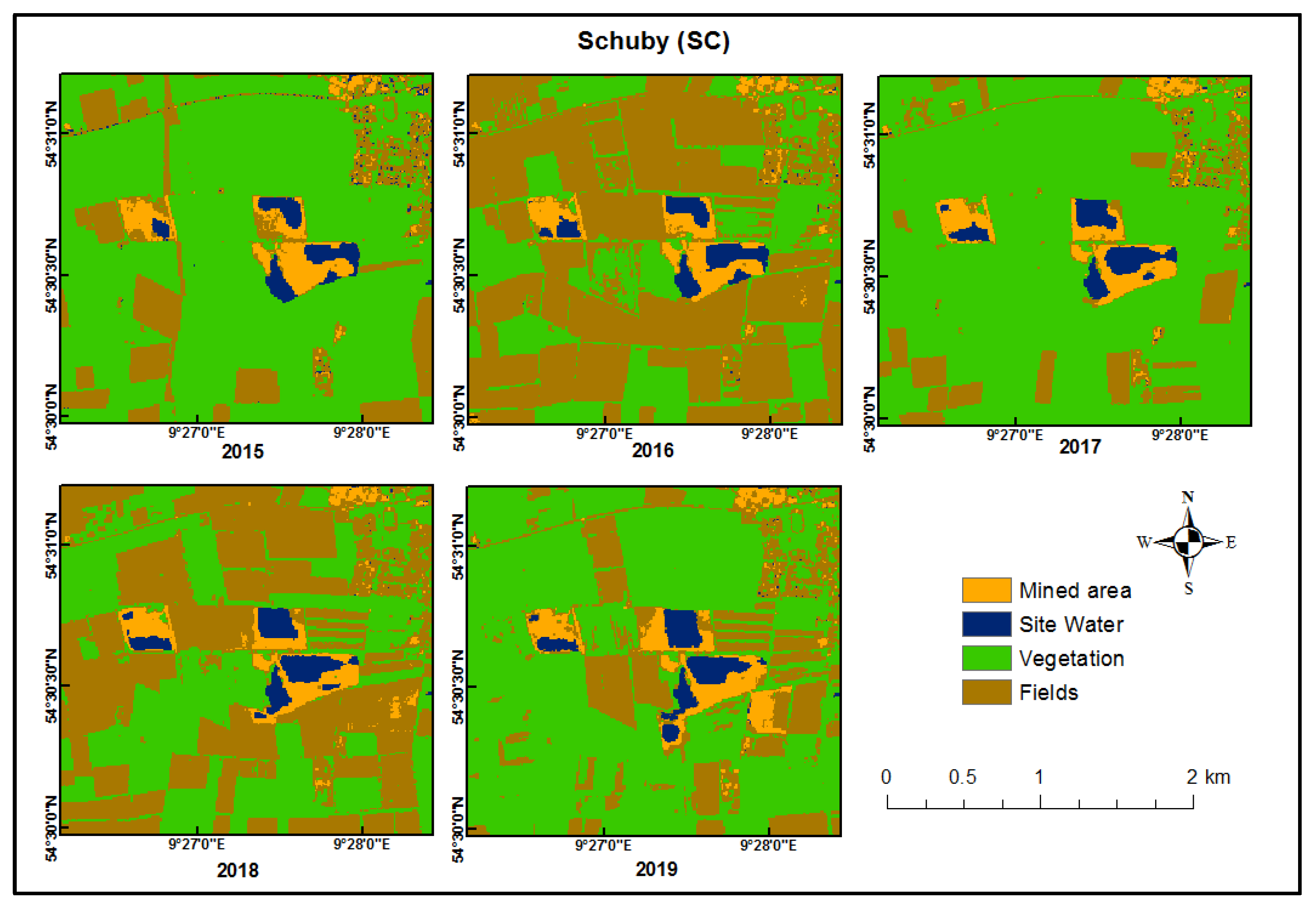

3.5. Spatial and Temporal Assessment of Land Use Changes from 2015 to 2019

3.5.1. Changes in Mined Areas

3.5.2. Changes in Site Water

4. Discussion

4.1. Methods Employed for Classification of Sentinel Data

4.1.1. Application of Sentinel Data

4.1.2. Effectiveness of the Support Vector Machines (SVM) Model

4.1.3. Spectral Bands and Indices

4.2. Spatial Changes in Mining Sites

4.2.1. Land Cover / Land Use Changes

4.2.2. Changes in Mined Sites

4.3. Importance to Regional Monitoring on Mined Area

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- H. M. Hamada, F. Abed, Z. A. Al-Sadoon, Z. Elnassar, and A. Hassan, “The use of treated desert sand in sustainable concrete: A mechanical and microstructure study,” J. Build. Eng., vol. 79, p. 107843, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Sinclair, “Applications of Probability Graphs in Mineral Exploration,” Miner. Explor., 1976.

- J. Blachowski, “Spatial analysis of the mining and transport of rock minerals (aggregates) in the context of regional development,” Environ. Earth Sci., vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 1327–1338, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Torres, J. Brandt, K. Lear, and J. Liu, “A looming tragedy of the sand commons,” Science, vol. 357, no. 6355, pp. 970–971, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Chilamkurthy, A. V. Marckson, S. T. Chopperla, and M. Santhanam, “A statistical overview of sand demand in Asia and Europe.,” 2016.

- J. Lowry, T. Coulthard, M. Saynor, and G. Hancock, “A comparison of landform evolution model predictions with multi-year observations from a rehabilitated landform,” 2020.

- S. K. Karan, S. R. Samadder, and S. K. Maiti, “Assessment of the capability of remote sensing and GIS techniques for monitoring reclamation success in coal mine degraded lands,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 182, pp. 272–283, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Kampmeier, E. M. Van Der Lee, U. Wichert, and J. Greinert, “Exploration of the munition dumpsite Kolberger Heide in Kiel Bay, Germany: Example for a standardised hydroacoustic and optic monitoring approach,” Cont. Shelf Res., vol. 198, p. 104108, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Leal Filho et al., “Heading towards an unsustainable world: some of the implications of not achieving the SDGs,” Discov. Sustain., vol. 1, no. 1, p. 2, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. D. Fachbeitrag Rohstoffsicherung., “Fachbeitrag Rohstoffsicherung,” 2019.

- A. M. Dewan and Y. Yamaguchi, “Using remote sensing and GIS to detect and monitor land use and land cover change in Dhaka Metropolitan of Bangladesh during 1960–2005,” Environ. Monit. Assess., vol. 150, no. 1–4, p. 237, Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- A. I. Alastal and A. H. Shaqfa, “GeoAI Technologies and Their Application Areas in Urban Planning and Development: Concepts, Opportunities and Challenges in Smart City (Kuwait, Study Case),” J. Data Anal. Inf. Process., vol. 10, no. 02, pp. 110–126, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Huang, B. Zhao, and Y. Song, “Urban land-use mapping using a deep convolutional neural network with high spatial resolution multispectral remote sensing imagery,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 214, pp. 73–86, Sep. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Tasionas et al., “UAV regular mapping focusing on surface mine monitoring,” in Eighth International Conference on Remote Sensing and Geoinformation of the Environment (RSCy2020), K. Themistocleous, S. Michaelides, V. Ambrosia, D. G. Hadjimitsis, and G. Papadavid, Eds., Paphos, Cyprus: SPIE, Aug. 2020, p. 72. [CrossRef]

- P. Tarolli, “High-resolution topography for understanding Earth surface processes: Opportunities and challenges,” Geomorphology, vol. 216, pp. 295–312, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. Giordan, Y. S. Hayakawa, F. Nex, and P. Tarolli, “Preface: The use of remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPAS) in monitoring applications and management of natural hazards,” Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., vol. 18, no. 11, pp. 3085–3087, Nov. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. E. Maxwell, T. A. Warner, M. P. Strager, and M. Pal, “Combining RapidEye Satellite Imagery and Lidar for Mapping of Mining and Mine Reclamation,” Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens., vol. 80, no. 2, pp. 179–189, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Maxwell, T. A. Warner, M. P. Strager, J. F. Conley, and A. L. Sharp, “Assessing machine-learning algorithms and image- and lidar-derived variables for GEOBIA classification of mining and mine reclamation,” Int. J. Remote Sens., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 954–978, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Schmidt and C. Glaesser, “Multitemporal analysis of satellite data and their use in the monitoring of the environmental impacts of open cast lignite mining areas in Eastern Germany,” Int. J. Remote Sens., vol. 19, no. 12, pp. 2245–2260, Jan. 1998. [CrossRef]

- D. Phiri, M. Simwanda, S. Salekin, V. Nyirenda, Y. Murayama, and M. Ranagalage, “Sentinel-2 Data for Land Cover/Use Mapping: A Review,” Remote Sens., vol. 12, no. 14, p. 2291, Jul. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. C. Duro, S. E. Franklin, and M. G. Dubé, “A comparison of pixel-based and object-based image analysis with selected machine learning algorithms for the classification of agricultural landscapes using SPOT-5 HRG imagery,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 118, pp. 259–272, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- L. Qu, Z. Chen, M. Li, J. Zhi, and H. Wang, “Accuracy Improvements to Pixel-Based and Object-Based LULC Classification with Auxiliary Datasets from Google Earth Engine,” Remote Sens., vol. 13, no. 3, p. 453, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Rogan, J. Franklin, and D. A. Roberts, “A comparison of methods for monitoring multitemporal vegetation change using Thematic Mapper imagery,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 80, no. 1, pp. 143–156, Apr. 2002. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Mas and J. J. Flores, “The application of artificial neural networks to the analysis of remotely sensed data,” Int. J. Remote Sens., vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 617–663, Feb. 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Yimer, A. Bouanani, N. Kumar, B. Tischbein, and C. Borgemeister, “Comparison of different machine-learning algorithms for land use land cover mapping in a heterogenous landscape over the Eastern Nile river basin, Ethiopia,” Adv. Space Res., vol. 74, no. 5, pp. 2180–2199, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, W. Chen, X. Cheng, and L. Wang, “A Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for Mapping of Complex Surface-Mined and Agricultural Landscapes Using ZiYuan-3 Stereo Satellite Imagery,” Remote Sens., vol. 8, no. 6, p. 514, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Gee, “Offshore wind power development as affected by seascape values on the German North Sea coast,” Land Use Policy, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 185–194, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Q. Wang, W. Shi, Z. Li, and P. M. Atkinson, “Fusion of Sentinel-2 images,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 187, pp. 241–252, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- O. Hagolle, M. Huc, D. Villa Pascual, and G. Dedieu, “A Multi-Temporal and Multi-Spectral Method to Estimate Aerosol Optical Thickness over Land, for the Atmospheric Correction of FormoSat-2, LandSat, VENμS and Sentinel-2 Images,” Remote Sens., vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 2668–2691, Mar. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Khatami, G. Mountrakis, and S. V. Stehman, “A meta-analysis of remote sensing research on supervised pixel-based land-cover image classification processes: General guidelines for practitioners and future research,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 177, pp. 89–100. May; 2016. [CrossRef]

- M.-R. Rujoiu-Mare, B. Olariu, B.-A. Mihai, C. Nistor, and I. Săvulescu, “Land cover classification in Romanian Carpathians and Subcarpathians using multi-date Sentinel-2 remote sensing imagery,” Eur. J. Remote Sens., vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 496–508, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Blaschke et al., “Geographic Object-Based Image Analysis – Towards a new paradigm,” ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens., vol. 87, pp. 180–191, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. Li and Y. Tang, “Two-dimensional nearest neighbor classification for agricultural remote sensing,” Neurocomputing, vol. 142, pp. 182–189, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Foody and A. Mathur, “A relative evaluation of multiclass image classification by support vector machines,” IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., vol. 42, no. 6, pp. 1335–1343, Jun. 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Cracknell and A. M. Reading, “Geological mapping using remote sensing data: A comparison of five machine learning algorithms, their response to variations in the spatial distribution of training data and the use of explicit spatial information,” Comput. Geosci., vol. 63, pp. 22–33, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. Huang, L. S. Davis, and J. R. G. Townshend, “An assessment of support vector machines for land cover classification,” Int. J. Remote Sens., vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 725–749, Jan. 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. S. De Fries, M. Hansen, J. R. G. Townshend, and R. Sohlberg, “Global land cover classifications at 8 km spatial resolution: The use of training data derived from Landsat imagery in decision tree classifiers,” Int. J. Remote Sens., vol. 19, no. 16, pp. 3141–3168, Jan. 1998. [CrossRef]

- C. Gómez, J. C. White, and M. A. Wulder, “Optical remotely sensed time series data for land cover classification: A review,” ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens., vol. 116, pp. 55–72, Jun. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Folke, L. Pritchard, Jr., F. Berkes, J. Colding, and U. Svedin, “The Problem of Fit between Ecosystems and Institutions: Ten Years Later,” Ecol. Soc., vol. 12, no. 1, p. art30, 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Knight, B. P. Tolcser, J. M. Corcoran, and L. P. Rampi, “The Effects of Data Selection and Thematic Detail on the Accuracy of High Spatial Resolution Wetland Classifications,” Photogramm. Eng., 2013.

- J. Corcoran, J. Knight, K. Pelletier, L. Rampi, and Y. Wang, “The Effects of Point or Polygon Based Training Data on RandomForest Classification Accuracy of Wetlands,” Remote Sens., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 4002–4025, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Townsend, D. P. Helmers, C. C. Kingdon, B. E. McNeil, K. M. De Beurs, and K. N. Eshleman, “Changes in the extent of surface mining and reclamation in the Central Appalachians detected using a 1976–2006 Landsat time series,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 113, no. 1, pp. 62–72, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Simmons et al., “FOREST TO RECLAIMED MINE LAND USE CHANGE LEADS TO ALTERED ECOSYSTEM STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION,” Ecol. Appl., vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 104–118, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Rajesh, “Application of remote sensing and GIS in mineral resource mapping ɻ An overview,” 2004.

- M. Drusch et al., “Sentinel-2: ESA’s Optical High-Resolution Mission for GMES Operational Services,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 120, pp. 25–36, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Whyte, K. P. Ferentinos, and G. P. Petropoulos, “A new synergistic approach for monitoring wetlands using Sentinels -1 and 2 data with object-based machine learning algorithms,” Environ. Model. Softw., vol. 104, pp. 40–54, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Korhonen, Hadi, P. Packalen, and M. Rautiainen, “Comparison of Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 in the estimation of boreal forest canopy cover and leaf area index,” Remote Sens. Environ., vol. 195, pp. 259–274, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Schneider, D. F. McGINNIS, and G. Stephens, “Monitoring Africa’s Lake Chad basin with LANDSAT and NOAA satellite data,” Int. J. Remote Sens., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 59–73, Jan. 1985. [CrossRef]

- F. F. Sabins, “Remote sensing for mineral exploration,” 1999.

- N.-T. Son, C.-F. Chen, C.-R. Chen, and V.-Q. Minh, “Assessment of Sentinel-1A data for rice crop classification using random forests and support vector machines,” Geocarto Int., pp. 1–15, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Maxwell and T. A. Warner, “Differentiating mine-reclaimed grasslands from spectrally similar land cover using terrain variables and object-based machine learning classification,” Int. J. Remote Sens., vol. 36, no. 17, pp. 4384–4410, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. Hildmann and M. Wonsche, “Lignite mining and its after-effects on the Central German landscape”.

- A. M. Dewan and Y. Yamaguchi, “Using remote sensing and GIS to detect and monitor land use and land cover change in Dhaka Metropolitan of Bangladesh during 1960–2005,” Environ. Monit. Assess., vol. 150, no. 1–4, p. 237, Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Myint and L. Wang, “Multicriteria decision approach for land use land cover change using Markov chain analysis and a cellular automata approach,” Can. J. Remote Sens., vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 390–404, Dec. 2006. [CrossRef]

| Study Area | 1(OS) | 2(EL) | 3(WA) | 4(SC) | 5(KR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Osterby | Ellund | Wanderup | Schuby | Klein Rheide |

| Area (sq. km) | 4322.8 | 12870.2 | 13258.7 | 5684 | 15600.9 |

| Pixels (10*10) | 214*202 | 406*317 | 403*329 | 245*232 | 483*323 |

| No. of mines | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Water | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year | Date Sensed | Tile Name |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 22.08.2015 | S2A_MSIL1C_20150822T104036_N0204_R008_T32UNF_20150822T104035 |

| 2016 | 04.06.2016 | S2A_MSIL1C_20160604T103032_N0202_R108_T32UNF_20160604T103026 |

| 2017 | 19.07.2017 | S2A_MSIL1C_20170719T103021_N0205_R108_T32UNF_20170719T103023 |

| 2018 | 25.05.2018 | S2A_MSIL1C_20180525T103021_N0206_R108_T32UNF_20180525T124252 |

| 2019 | 29.06.2019 | S2A_MSIL1C_20180525T103021_N0206_R108_T32UNF_20180525T124252 |

| Indices | Property | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | Health and amount of Vegetation | (NIR-R) / (NIR + R) |

| Brightness Index (BI) | Average reflectance magnitude | ((R2 + G2 + B2) / 3)0.5 |

| Coloration Index (CI) | Soil colour | (R-G) / (R + G) |

| Saturation Index (SI) | Spectral slope | (R-B) / (R + B) |

| Redness Index (RI) | Hematite content | R2 / (B * G3) |

| Data | Random Forest | Support Vector Machine | Neural Network | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Kappa | Accuracy | Kappa | Accuracy | Kappa | |

| 2015 | ||||||

| OS | 0.9991 | 0.9986 | 0.9994 | 0.9991 | 0.9994 | 0.9991 |

| EL | 0.9958 | 0.9932 | 0.9939 | 0.9900 | 0.9912 | 0.9858 |

| WA | 0.9988 | 0.9982 | 0.9901 | 0.9852 | 0.9980 | 0.9971 |

| SC | 0.9978 | 0.9970 | 0.9985 | 0.9978 | 0.9977 | 0.9967 |

| KR | 0.9993 | 0.9989 | 0.9973 | 0.9959 | 0.9986 | 0.9980 |

| 2016 | ||||||

| OS | 0.9984 | 0.9973 | 0.9971 | 0.9949 | 0.9949 | 0.9911 |

| EL | 0.9963 | 0.9934 | 0.9946 | 0.9904 | 0.9954 | 0.9918 |

| WA | 0.9967 | 0.9954 | 0.9956 | 0.9938 | 0.9957 | 0.9939 |

| SC | 0.9952 | 0.9927 | 0.9932 | 0.9897 | 0.9940 | 0.9910 |

| KR | 0.9847 | 0.9757 | 0.9781 | 0.9652 | 0.9781 | 0.9653 |

| 2017 | ||||||

| OS | 0.9910 | 0.9844 | 0.9828 | 0.9702 | 0.9853 | 0.9745 |

| EL | 0.9985 | 0.9974 | 0.9979 | 0.9964 | 0.9984 | 0.9973 |

| WA | 0.9951 | 0.9930 | 0.9919 | 0.9884 | 0.9930 | 0.9900 |

| SC | 0.9997 | 0.9994 | 0.9997 | 0.9994 | 0.9994 | 0.9990 |

| KR | 0.9981 | 0.9968 | 0.9967 | 0.9944 | 0.9967 | 0.9944 |

| 2018 | ||||||

| OS | 0.8465 | 0.7303 | 0.8477 | 0.7313 | 0.8597 | 0.7524 |

| EL | 0.9980 | 0.9966 | 0.9958 | 0.9929 | 0.9959 | 0.9930 |

| WA | 0.9963 | 0.9942 | 0.9756 | 0.9641 | 0.9843 | 0.9768 |

| SC | 0.9968 | 0.9949 | 0.9966 | 0.9946 | 0.9954 | 0.9927 |

| KR | 0.9997 | 0.9995 | 0.9993 | 0.9989 | 0.9995 | 0.9993 |

| 2019 | ||||||

| OS | 0.9577 | 0.9252 | 0.9087 | 0.8384 | 0.9205 | 0.8593 |

| EL | 0.9970 | 0.9915 | 0.9887 | 0.9675 | 0.9956 | 0.9874 |

| WA | 0.9973 | 0.9960 | 0.9938 | 0.9911 | 0.9931 | 0.9900 |

| SC | 0.9779 | 0.9624 | 0.9666 | 0.9436 | 0.9747 | 0.9569 |

| KR | 0.9889 | 0.9809 | 0.9858 | 0.9756 | 0.9856 | 0.9753 |

| Year | Random Forest | Support Vector Machine | Neural Network | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Kappa | Accuracy | Kappa | Accuracy | Kappa | |

| 2015 | 0.9984 | 0.9978 | 0.9980 | 0.9971 | 0.9966 | 0.9951 |

| 2016 | 0.9989 | 0.9983 | 0.9900 | 0.9835 | 0.9924 | 0.9883 |

| 2017 | 0.9990 | 0.9982 | 0.9966 | 0.9948 | 0.9945 | 0.9914 |

| 2018 | 0.9871 | 0.9802 | 0.9754 | 0.9620 | 0.9762 | 0.9632 |

| 2019 | 0.9951 | 0.9919 | 0.9715 | 0.9526 | 0.9632 | 0.9386 |

| Model | Accuracy | Kappa |

|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.9945 | 0.9916 |

| SVM | 0.9781 | 0.9663 |

| ANN | 0.9639 | 0.9399 |

| Data | Random Forest | Support Vector Machine | Neural Network | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Kappa | Specificity | Accuracy | Kappa | Specificity | Accuracy | Kappa | Specificity | |

| 2015 | |||||||||

| 1. OS | 0.987 | 0.975 | 1 | 0.929 | 0.853 | 1 | 0.843 | 0.689 | 0.974 |

| 2. EL | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.977 | 0.958 | 0.958 |

| 3. WA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.629 | 0.533 | 0.661 |

| 4. SC | 0.995 | 0.994 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.868 | 0.799 | 0.896 |

| 5. KR | 0.811 | 0.720 | 0.720 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.972 | 0.953 | 0.974 |

| 2016 | |||||||||

| 1. OS | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1 | 0.936 | 0.886 | 0.972 |

| 2. EL | 0.998 | 0.996 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.955 | 0.923 | 0.959 |

| 3. WA | 0.967 | 0.952 | 0.999 | 0.967 | 0.952 | 0.999 | 0.682 | 0.573 | 0.731 |

| 4. SC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.903 | 0.826 | 0.908 |

| 5. KR | 0.627 | 0.350 | 0.829 | 0.777 | 0.542 | 0.989 | 0.757 | 0.492 | 0.975 |

| 2017 | |||||||||

| 1. OS | 0.996 | 0.992 | 1 | 0.995 | 0.990 | 1 | 0.976 | 0.955 | 0.978 |

| 2. EL | 0.946 | 0.904 | 0.972 | 0.954 | 0.917 | 1 | 0.936 | 0.885 | 0.964 |

| 3. WA | 0.988 | 0.982 | 1 | 0.981 | 0.971 | 1 | 0.653 | 0.520 | 0.932 |

| 4. SC | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.843 | 0.764 | 0.838 |

| 5. KR | 0.881 | 0.812 | 0.896 | 0.99 | 0.983 | 1 | 0.957 | 0.925 | 0.986 |

| 2018 | |||||||||

| 1. OS | 0.918 | 0.845 | 1 | 0.980 | 0.963 | 1 | 0.943 | 0.893 | 0.971 |

| 2. EL | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 1 | 0.938 | 0.897 | 0.960 |

| 3. WA | 0.994 | 0.991 | 1 | 0.994 | 0.990 | 0.999 | 0.684 | 0.540 | 0.743 |

| 4. SC | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.993 | 0.989 | 0.993 | 0.866 | 0.733 | 0.805 |

| 5. KR | 0.858 | 0.769 | 0.850 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.968 | 0.939 | 0.991 |

| 2019 | |||||||||

| 1. OS | 0.977 | 0.959 | 1 | 0.987 | 0.977 | 1 | 0.954 | 0.920 | 0.960 |

| 2. EL | 0.966 | 0.937 | 0.984 | 0.987 | 0.970 | 0.994 | 0.894 | 0.802 | 0.782 |

| 3. WA | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1 | 0.643 | 0.533 | 0.782 |

| 4. SC | 0.974 | 0.962 | 1 | 0.978 | 0.967 | 1 | 0.772 | 0.672 | 0.792 |

| 5. KR | 0.913 | 0.866 | 0.866 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.945 | 0.912 | 0.951 |

| Year | Osterby (OS) | Ellund (EL) | Wanderup (WA) | Schuby (SC) | Klein Rheide (KR) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | F1 score | Accuracy | F1 score | Accuracy | F1 score | Accuracy | F1 score | Accuracy | F1 score | ||

| 2015 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2016 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.78 | 0.77 | |

| 2017 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| 2018 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| 2019 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Variable Combinations | Accuracy | Kappa |

|---|---|---|

| Red, Green, Blue, NIR | 0.968 | 0.940 |

| Red, Green, Blue, NIR, SWIR-1 | 0.970 | 0.944 |

| Red, Green, Blue, NIR, SWIR-1, SWIR-2 | 0.981 | 0.964 |

| Red, Green, Blue, NIR, SWIR-1, SWIR-2, CI | 0.980 | 0.963 |

| Red, Green, Blue, NIR, SWIR-1, SWIR-2, CI, RI | 0.980 | 0.963 |

| Red, Green, Blue, NIR, SWIR-1, SWIR-2, CI, RI, SI | 0.977 | 0.957 |

| Red, Green, Blue, NIR, SWIR-1, SWIR-2, CI, RI, SI, NDVI | 0.982 | 0.967 |

| Red, Green, Blue, NIR, SWIR-1, SWIR-2, CI, RI, SI, NDVI, BI | 0.983 | 0.968 |

| Red, Green, Blue, NIR, SWIR-1, SWIR-2, CI, RI, SI, NDVI, BI, Elevation | 0.984 | 0.970 |

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land cover | Area (km2) |

% of Area |

Area (km2) |

% of Area |

Area (km2) |

% of Area |

Area (km2) |

% of Area |

Area (km2) |

% of Area |

|

| Osterby (OS) | |||||||||||

| Mined area | 0.06 | 1.39 | 0.09 | 2.08 | 0.09 | 2.08 | 0.1 | 2.31 | 0.1 | 2.31 | |

| Water | 0.03 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.46 | |

| Vegetation | 3.58 | 82.87 | 2.41 | 55.79 | 3.22 | 74.36 | 2.15 | 49.77 | 3.04 | 70.37 | |

| Fields | 0.65 | 15.05 | 1.8 | 41.67 | 1 | 23.09 | 2.05 | 47.45 | 1.16 | 26.85 | |

| Ellund (EL) | |||||||||||

| Mined area | 0.36 | 2.8 | 0.33 | 2.56 | 0.27 | 2.1 | 0.34 | 2.64 | 0.38 | 2.95 | |

| Water | 0.17 | 1.32 | 0.15 | 1.17 | 0.13 | 1.01 | 0.16 | 1.24 | 0.13 | 1.01 | |

| Vegetation | 8.08 | 62.83 | 9.11 | 70.78 | 8.97 | 69.7 | 9.66 | 75.06 | 9.96 | 77.39 | |

| Fields | 4.25 | 33.05 | 3.28 | 25.49 | 3.5 | 27.2 | 2.71 | 21.06 | 2.4 | 18.65 | |

| Wanderup (WA) | |||||||||||

| Mined area | 0.29 | 2.19 | 0.31 | 2.34 | 0.3 | 2.26 | 0.29 | 2.19 | 0.34 | 2.44 | |

| Water | 0.66 | 4.98 | 0.63 | 4.75 | 0.61 | 4.6 | 0.65 | 4.9 | 0.62 | 4.44 | |

| Vegetation | 10.47 | 78.96 | 5.96 | 44.95 | 10.54 | 79.49 | 6.35 | 47.85 | 9.77 | 69.99 | |

| Fields | 1.84 | 13.88 | 6.36 | 47.96 | 1.81 | 13.65 | 5.98 | 45.06 | 3.23 | 23.14 | |

| Schuby (SC) | |||||||||||

| Mined area | 0.24 | 4.23 | 0.25 | 4.4 | 0.26 | 4.57 | 0.26 | 4.57 | 0.31 | 5.46 | |

| Water | 0.15 | 2.64 | 0.14 | 2.46 | 0.15 | 2.64 | 0.16 | 2.82 | 0.17 | 2.99 | |

| Vegetation | 4.21 | 74.12 | 1.69 | 29.75 | 4.51 | 79.26 | 2.27 | 39.96 | 3.83 | 67.43 | |

| Fields | 1.08 | 19.01 | 3.6 | 63.38 | 0.77 | 13.53 | 2.99 | 52.64 | 1.37 | 24.12 | |

| Klein Rheide (KR) | |||||||||||

| Mined area | 0.7 | 4.49 | 0.81 | 5.19 | 0.82 | 5.26 | 0.87 | 5.57 | 0.9 | 5.77 | |

| Water | 0.23 | 1.47 | 0.18 | 1.15 | 0.18 | 1.15 | 0.22 | 1.41 | 0.18 | 1.15 | |

| Vegetation | 11.38 | 72.95 | 7.08 | 45.38 | 11.47 | 73.53 | 7.17 | 45.93 | 10.48 | 67.18 | |

| Fields | 3.29 | 21.09 | 7.53 | 48.27 | 3.13 | 20.06 | 7.35 | 47.09 | 4.04 | 25.9 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).