Submitted:

18 April 2023

Posted:

19 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

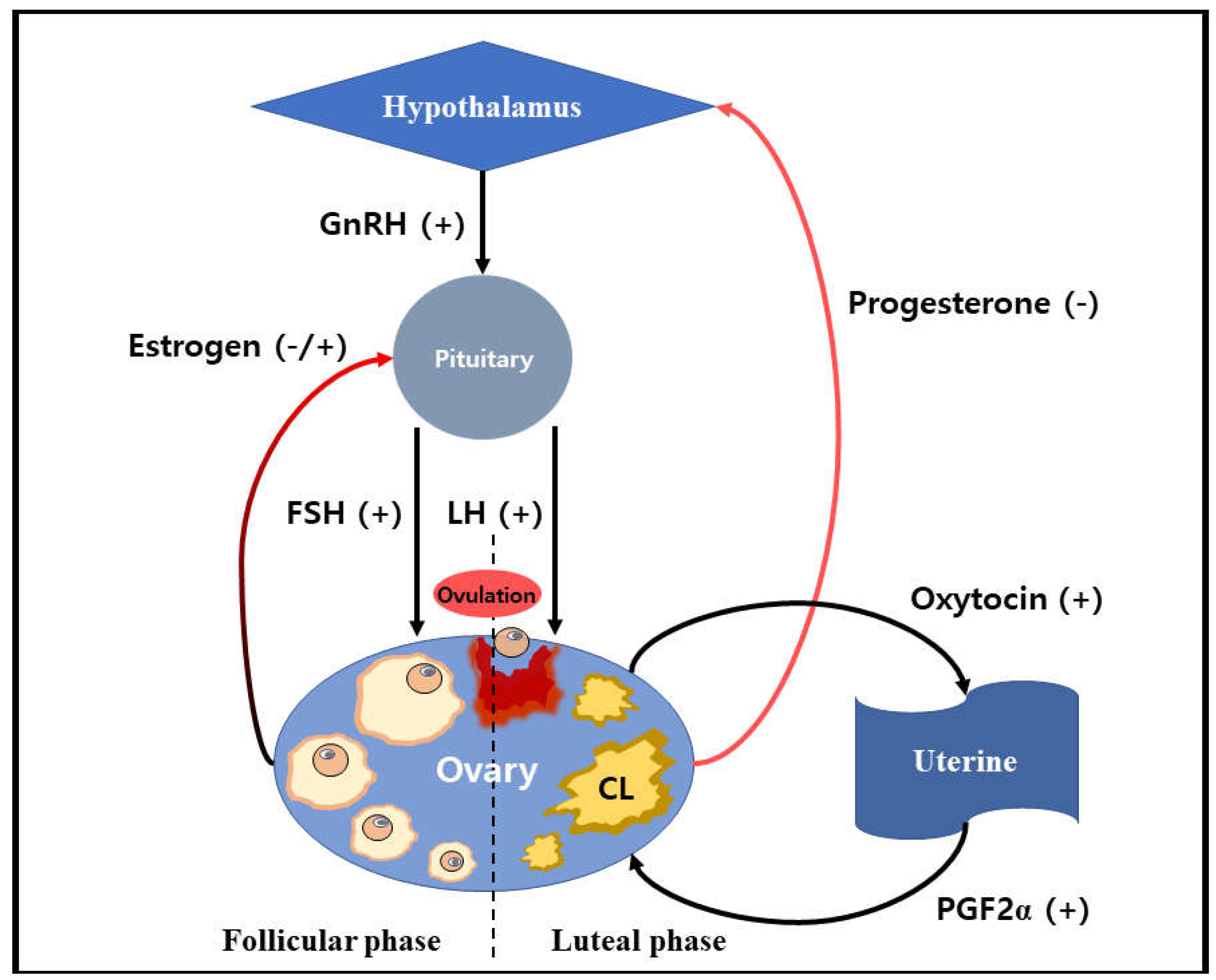

2. The functions of reproductive hormone in the ovarian corpus luteum

2.1. Estrogen

2.2. Progesterone

2.3. Prostaglandin F2α

2.4. Oxytocin

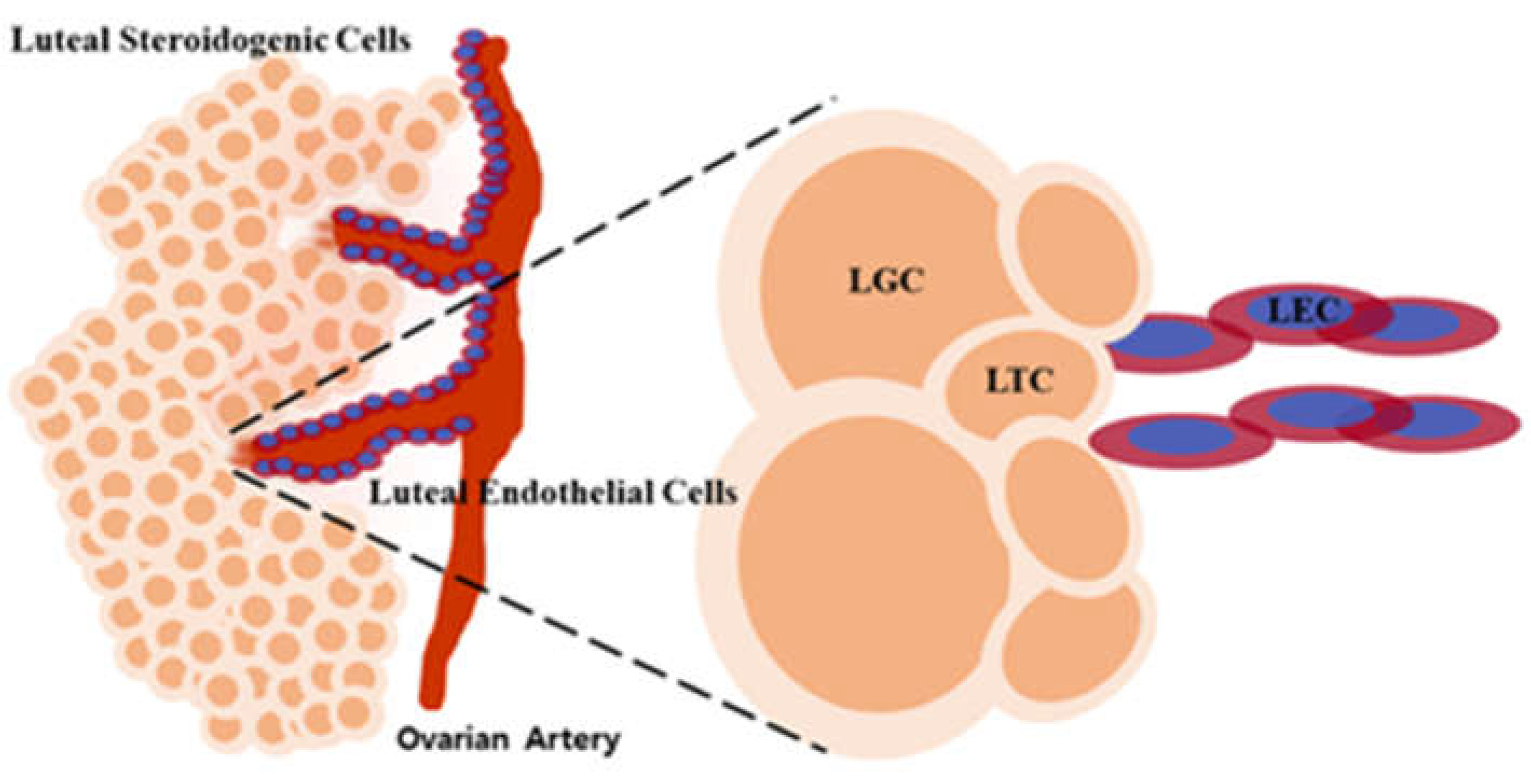

3. Luteal cell types of the corpus luteum

3.1. Luteal steroidogenic cell

3.2. Luteal granulosa cell

3.3. Luteal theca cell

3.4. Luteal endothelial cell

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Billhaq, D.H. Microenvironment system during the stage of formation and regression of the ovarian corpus luteum in cows. M.S., Kangwon National University, Republic of Korea, February 22, 2020.

- Reynolds, L.P.; Killilea, S.D.; Redmer, D.A. Angiogenesis in the female reproductive system. Faseb J. 1992, 6, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schams, D.; Berisha, B. Regulation of corpus luteum function in cattle–an overview. Reprod. Domest. Aanim. 2004, 39, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niswender, G.D.; Juengel, J.L.; Silva, P.J.; Rollyson, M.K.; McIntush, E.W. Mechanisms controlling the function and life span of the corpus luteum. Physiol. Rev. 2000, 80, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomac, J.; Cekinović, Đ.; Arapović, J. Biology of the corpus luteum. Period. Biol. 2011, 113, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Devoto, L.; Fuentes, A.; Kohen, P.; Céspedes, P.; Palomino, A.; Pommer, R.; Strauss III, J.F. The human corpus luteum: life cycle and function in natural cycles. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.L.; Robker, R.L. Molecular mechanisms of ovulation: co-ordination through the cumulus complex. Hum. Reprod. Update 2007, 13, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, H.K. Loss luteal sensitivity to luteinizing hormone underlies luteolysis in cattle: A hypothesis. Reprod.. Biol. 2021, 21, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, S.; Abe, H.; Sakumoto, R.; Okuda, K. Proliferation of luteal steroidogenic cells in cattle. PLoS One 2013, 8, e84186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, N.; Beltman, M.E.; Lonergan, P.; Diskin, M.; Roche, J.F.; Crowe, M.A. Oestrous cycles in Bos taurus cattle. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2011, 124, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carletti, M.Z.; Christenson, L.K. MicroRNA in the ovary and female reproductive tract. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, E29–E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.S.; Pangas, S.A. The ovary: basic biology and clinical implications. J. Clin. Invest. 2010, 120, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, F.; Inoue, N.; Manabe, N.; Ohkura, S. Follicular growth and atresia in mammalian ovaries: regulation by survival and death of granulosa cells. J. Reprod. Develop. 2012, 58, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, J.F. Control and regulation of folliculogenesis--a symposium in perspective. Rev. Reprod. 1996, 1, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginther, O.J.; Bergfelt, D.R.; Beg, M.A.; Kot, K. Role of low circulating FSH concentrations in controlling the interval to emergence of the subsequent follicular wave in cattle. Reproduction 2002, 124, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, M.G.; Robinson, R.S.; Mann, G.E.; Webb, R. Endocrine and paracrine control of follicular development and ovulation rate in farm species. Anim. Rreprod. Sci. 2004, 82, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshay, V.E.; Carr, B.R. Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery; Springer International Publishing: Cham, USA, 2017; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Berisha, B.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Schams, D. Expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in the bovine ovary during estrous cycle and pregnancy. Endocrine 2002, 17, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.S.; Mann, G.E.; Reynolds, T.S.; Lamming, G.E.; Wathes, D.C. Expression of oxytocin, oestrogen and progesterone receptors in uterine biopsy samples throughout the oestrous cycle and early pregnancy in cows. Reproduction 2001, 122, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berisha, B.; Schams, D. Ovarian function in ruminants. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2005, 29, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espey, L.L. Current status of the hypothesis that mammalian ovulation is comparable to an inflammatory reaction. Biol. Reprod. 1994, 50, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormshak, F. Biochemical and endocrine aspects of oxytocin production by the mammalian corpus luteum. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2003, 1, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwica, J.; Skarzynski, D.; Miszkiel, G.; Melin, P.; Okuda, K. Oxytocin modulates the pulsatile secretion of prostaglandin F2αin initiated luteolysis in cattle. Res. Vet. Sci. 1999, 66, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamshidi, A.A.; Girard, D.; Beaudry, F.; Goff, A.K. Progesterone metabolism in bovine endometrial cells and the effect of metabolites on the responsiveness of the cells to OT-stimulation of PGF2α. Steroids 2007, 72, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtani, M.; Kobayashi, S.I.; Miyamoto, A.; Hayashi, K.; Fukui, Y. Real-Time Relationships between Intraluteal and Plasma Concentrations of Endothelin, Oxytocin, and Progesterone during Prostaglandin F2α-Induced Luteolysis in the Cow. Biol. Reprod. 1998, 58, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocco, C.; Telleria, C.; Gibori, G. The molecular control of corpus luteum formation, function, and regression. Endocr. Rev. 2007, 28, 117–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plendl, J. Angiogenesis and vascular regression in the ovary. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2000, 29, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiyama, R.; Wada-Kiyama, Y. Estrogenic endocrine disruptors: Molecular mechanisms of action. Environ. Int. 2015, 83, 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.M.; McNeilly, A.S. Theca: the forgotten cell of the ovarian follicle. Reproduction 2010, 140, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimon-Dahari, N.; Yerushalmi-Heinemann, L.; Alyagor, L.; Dekel, N. Molecular mechanisms of cell differentiation in gonad development; Springer International Publishing: Cham, USA, 2016; pp. 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- Stouffer, R.L.; Bishop, C.V.; Bogan, R.L.; Xu, F.; Hennebold, J.D. Endocrine and local control of the primate corpus luteum. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 13, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makieva, S.; Saunders, P.T.; Norman, J.E. Androgens in pregnancy: roles in parturition. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.S.; Beshay, V.E.; Escobar, J.C.; Carr, B.R. 17α-Hydroxylase (CYP17) expression and subsequent androstenedione production in the human ovary. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 17, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moggs, J.G.; Orphanides, G. Estrogen receptors: orchestrators of pleiotropic cellular responses. EMBO Rep. 2001, 2, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taraborrelli, S. Physiology, production and action of progesterone. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2015, 94, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, K.; Cui, W.; Dhakal, P.; Wolfe, M.W.; Rumi, M.K.; Vivian, J.L.; Soares, M.J. Rethinking progesterone regulation of female reproductive cyclicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113, 4212–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Miyagawa, S.; Iguchi, T. Handbook of Hormones, 1st ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, USA, 2015; p. 507. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.S.; LaVoie, H.A. Molecular Regulation of Progesterone; Academic Press: Cambridge, USA, 2019; pp. 237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; O'Malley, B.W. Unfolding the action of progesterone receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 39261–39264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peluso, J.J. Progesterone receptor membrane component 1 and its role in ovarian follicle growth. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koensgen, D.; Mustea, A.; Klaman, I.; Sun, P.; Zafrakas, M.; Lichtenegger, W.; Sehouli, J. Expression analysis and RNA localization of PAI-RBP1 (SERBP1) in epithelial ovarian cancer: association with tumor progression. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 107, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, F.J.; Anderson, L.E.; Wu, Y.L.; Rabot, A.; Tsai, S.J.; Wiltbank, M.C. Regulation of progesterone and prostaglandin F2α production in the CL. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2002, 191, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginther, O.J.; Fuenzalida, M.J.; Shrestha, H.K.; Beg, M.A. The transition between pre-luteolysis and luteolysis in cattle. Theriogenology 2011, 75, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waclawik, A.; Jabbour, H.N.; Blitek, A.; Ziecik, A.J. Estradiol-17β, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and the PGE2 receptor are involved in PGE2 positive feedback loop in the porcine endometrium. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 3823–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rensis, F.; Saleri, R.; Tummaruk, P.; Techakumphu, M.; Kirkwood, R.N. Prostaglandin F2α and control of reproduction in female swine: a review. Theriogenology 2012, 77, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginther, O.J.; Shrestha, H.K.; Fuenzalida, M.J.; Imam, S.; Beg, M.A. Stimulation of pulses of 13, 14-dihydro-15-keto-PGF2α (PGFM) with estradiol-17β and changes in circulating progesterone concentrations within a PGFM pulse in heifers. Theriogenology 2010, 74, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, F.J.; Wiltbank, M.C. Acquisition of luteolytic capacity involves differential regulation by prostaglandin F2α of genes involved in progesterone biosynthesis in the porcine corpus luteum. Domestic animal endocrinology 2005, 28, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assad, N.I.; Pandey, A.K.; Sharma, L.M. Oxytocin, functions, uses and abuses: a brief review. Theriogenology 2016, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froemke, R.C.; Carcea, I. Principles of Gender-Specific Medicine, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, USA, 2017; pp. 161–182. [Google Scholar]

- Salmina, A.B.; Lopatina, O.; Ekimova, M.V.; Mikhutkina, S.V. , Higashida, H. CD38/Cyclic ADP-ribose system: a new player for oxytocin secretion and regulation of social behavior. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2010, 22, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrowsmith, S.; Wray, S. Oxytocin: its mechanism of action and receptor signalling in the myometrium. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 26, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smallman, M.S. Possible Autocrine/Paracrine Action of Progesterone in the Ovine Corpus Luteum. M.S., Oregon State University, USA, June 26, 2018.

- Woad, K.J.; Robinson, R.S. Luteal angiogenesis and its control. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewgenow, K.; Amelkina, O.; Painer, J.; Göritz, F.; Dehnhard, M. Life cycle of feline corpora lutea: histological and intraluteal hormone analysis. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2012, 47, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanhong, Y.; Yan, C.; Sijiu, Y. Histological characteristics of corpus luteum in yak during early pregnancy. In Proceedings of the 2004 International Congress on Yak, Chengdu, China, 19 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea, J.D.; Rodgers, R.J.; D'occhio, M.J. Cellular composition of the cyclic corpus luteum of the cow. Reproduction 1989, 85, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanel-Borowski, K. Five different phenotypes of endothelial cell cultures from the bovine corpus luteum: present outcome and role of potential dendritic cells in luteolysis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 338, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.R.; Palai, T.K. Steroidogenesis in luteal cell: A critical pathway for progesterone production. J. Invest. Biochem. 2015, 4, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, W.J.; Azhar, S. Cellular cholesterol delivery, intracellular processing and utilization for biosynthesis of steroid hormones. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaVoie, H.A. The Life Cycle of the Corpus Luteum; Springer International Publishing: Cham, USA, 2017; pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, V.; Miller, W.L. Role of mitochondria in steroidogenesis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endoc. Metab. 2012, 26, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, B.D. Models of luteinization. Biol. Reprod. 2000, 63, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.M.; Chegini, N.; Rao, C.V. Quantitative cell composition of human and bovine corpora lutea from various reproductive states. Biol. Reprod. 1991, 44, 1148–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenson, L.K.; Devoto, L. Cholesterol transport and steroidogenesis by the corpus luteum. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2003, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, K.; Rodler, D.; Sinowatz, F.; Meidan, R. The Ovary, 3rd ed.Academic Press: Rehovot, Israel, 2019; pp. 255–267. [Google Scholar]

- Shirasuna, K.; Akabane, Y.; Beindorff, N.; Nagai, K.; Sasaki, M.; Shimizu, T.; Miyamoto, A. Expression of prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) receptor and its isoforms in the bovine corpus luteum during the estrous cycle and PGF2α-induced luteolysis. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2012, 43, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, K.; Nishimura, R. The Life Cycle of the Corpus Luteum; Springer International Publishing: Cham, USA, 2017; pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).