Submitted:

18 April 2023

Posted:

18 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Inflammasome's Mechanism of action

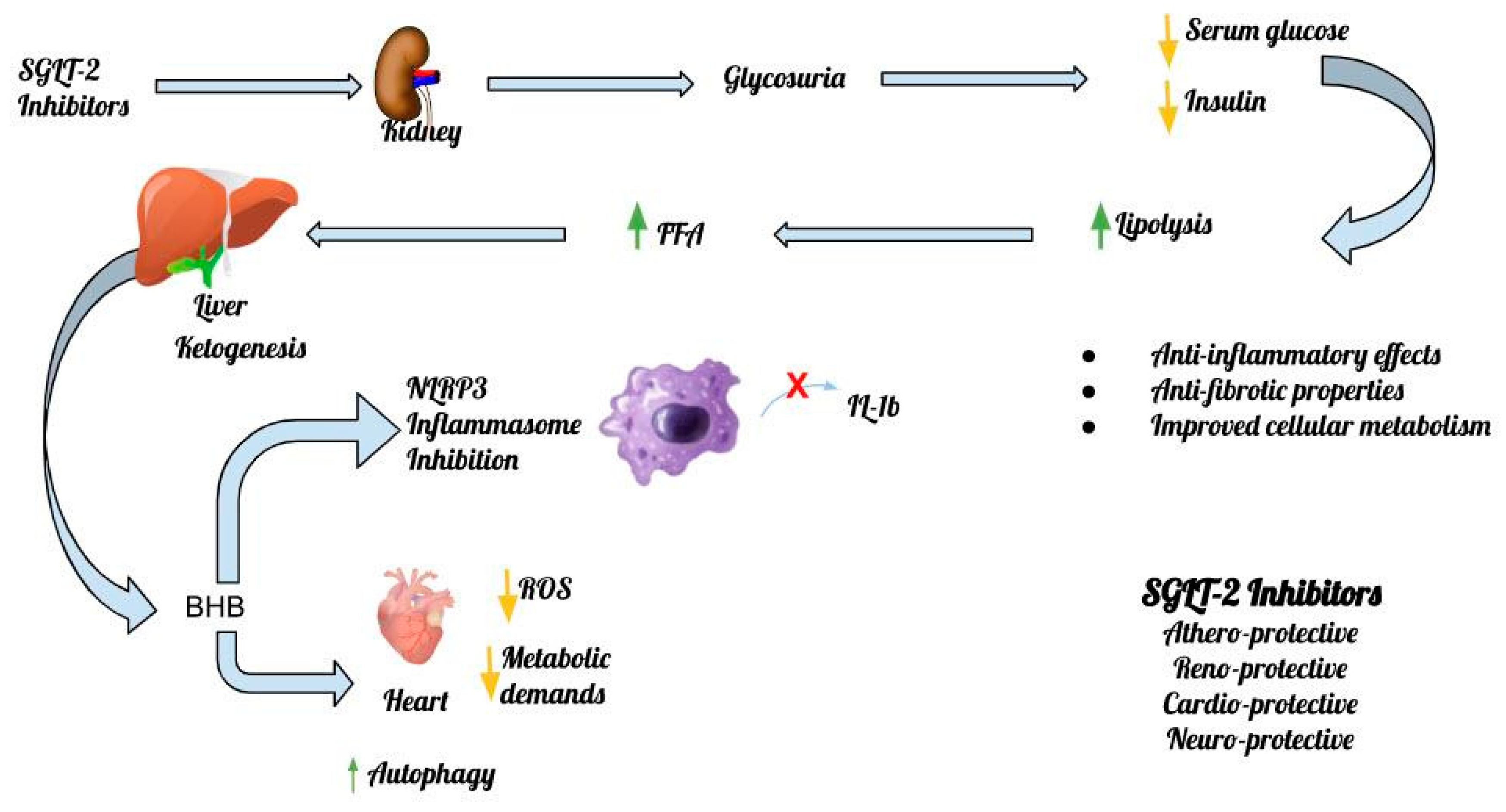

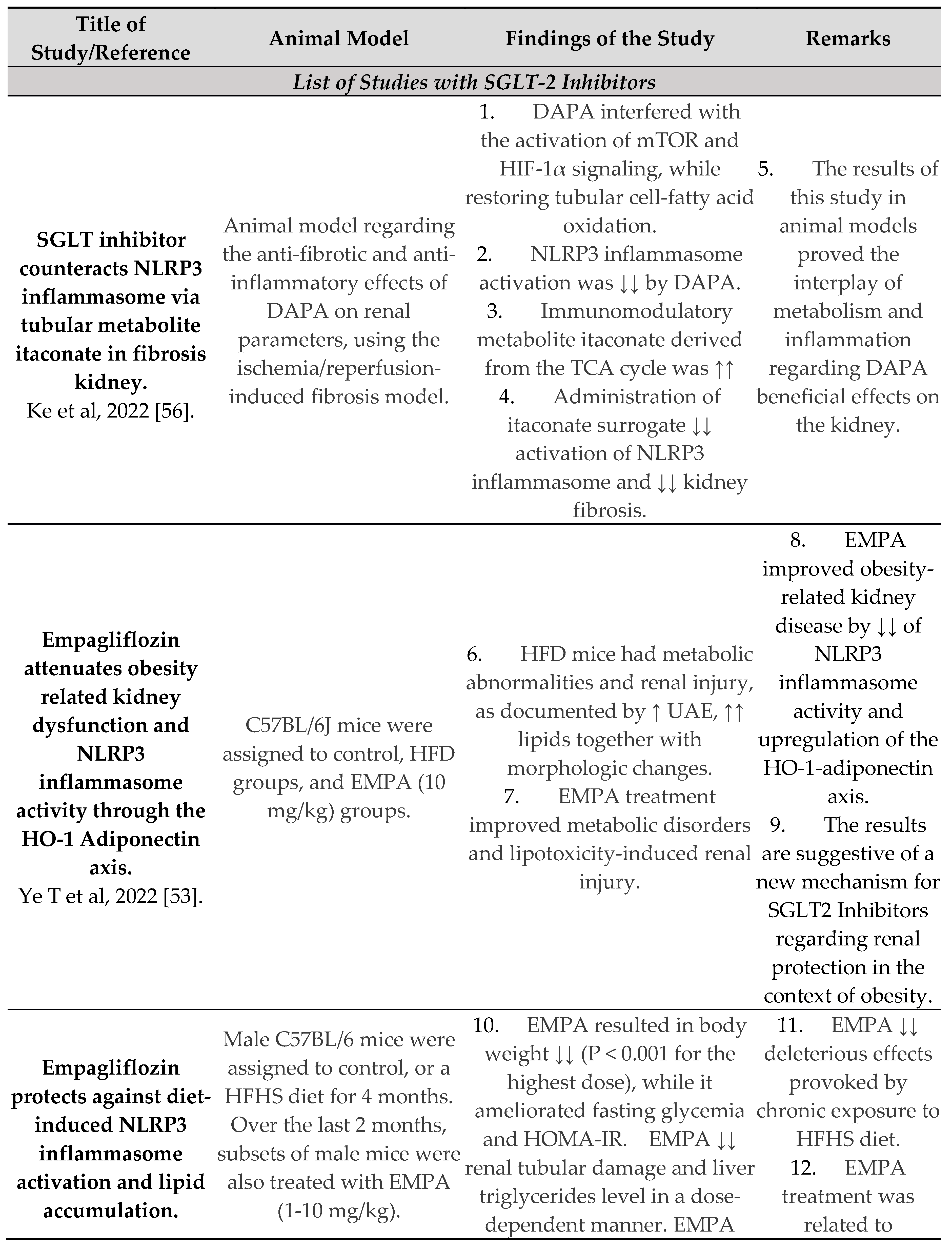

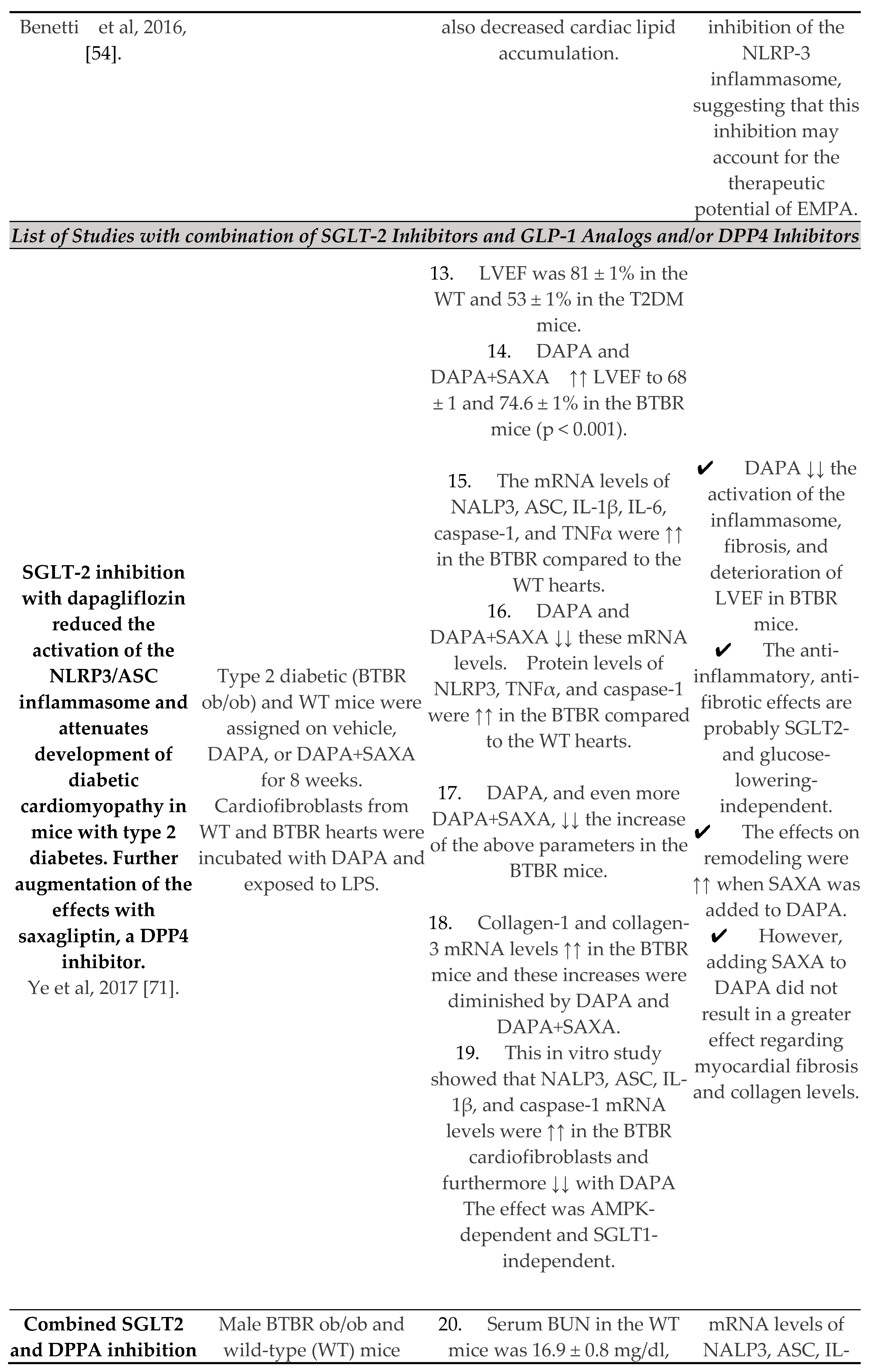

SGLT-2 inhibitors' Anti-inflammatory effects

SGLT-2 and the heart

The Inflammasome and Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

The Inflammasome and Central Nervous System

Conclusion

Abbreviations

References

- Caparrotta, T.M.; Greenhalgh, A.M.; Osinski, K.; Gifford, R.M.; Moser, S.; Wild, S.H.; Reynolds, R.M.; Webb, D.J.; Colhoun, H.M. Sodium–Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitors (SGLT2i) Exposure and Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Observational Studies. Diabetes Ther. 2021, 12, 991–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, A.; Jardine, M.J. SGLT2 inhibitors may offer benefit beyond diabetes. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 17, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cefalu, W.T.; Riddle, M.C. SGLT2 Inhibitors: The Latest “New Kids on the Block”! Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 352–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Christodoulatos, G.S.; Kounatidis, D.; Dalamaga, M. Sotagliflozin, a dual SGLT1 and SGLT2 inhibitor: In the heart of the problem. Metab. Open 2021, 10, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, C. Analyse des Phloridzins. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1835, 15, 178–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.R. Apple Trees to Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter Inhibitors: A Review of SGLT2 Inhibition. Clin. Diabetes 2010, 28, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Trigkidis, K.; Kazazis, C. Sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors and their nephroprotective potential. Clin. Nephrol. 2017, 87, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: www.uptodate.com (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- The Human Protein Atlas Single Cell Type—NLRP3. Available online: https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000162711-NLRP3 /single+cell+type (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Marcuzzi, A.; Melloni, E.; Zauli, G.; Romani, A.; Secchiero, P.; Maximova, N.; Rimondi, E. Autoinflammatory Diseases and Cytokine Storms—Imbalances of Innate and Adaptative Immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P.-Y. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdette, B.E.; Esparza, A.N.; Zhu, H.; Wang, S. Gasdermin D in pyroptosis. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 2768–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-M.; Kim, J.-J.; Kim, H.J.; Shong, M.; Ku, B.J.; Jo, E.-K. Upregulated NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2012, 62, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, A.; Toldo, S.; Marchetti, C.; Kron, J.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Dinarello, C.A. Interleukin-1 and the Inflammasome as Therapeutic Targets in Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1260–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Meng, X.-F.; Zhang, C. NLRP3 Inflammasome in Metabolic-Associated Kidney Diseases: An Update. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feijóo-Bandín, S.; Aragón-Herrera, A.; Otero-Santiago, M.; Anido-Varela, L.; Moraña-Fernández, S.; Tarazón, E.; Roselló-Lletí, E.; Portolés, M.; Gualillo, O.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; et al. Role of Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitors in the Regulation of Inflammatory Processes in Animal Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Mamun, A.; Akter, A.; Hossain, S.; Sarker, T.; Safa, S.A.; Mustafa, Q.G.; Muhammad, S.A.; Munir, F. Role of NLRP3 inflammasome in liver disease. J. Dig. Dis. 2020, 21, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.R.; Lee, S.-G.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, E.; Cho, W.; Rim, J.H.; Hwang, I.; Lee, C.J.; Lee, M.; et al. SGLT2 inhibition modulates NLRP3 inflammasome activity via ketones and insulin in diabetes with cardiovascular disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetti, E.; Mastrocola, R.; Vitarelli, G.; Cutrin, J.C.; Nigro, D.; Chiazza, F.; Mayoux, E.; Collino, M.; Fantozzi, R. Empagliflozin Protects against Diet-Induced NLRP-3 Inflammasome Activation and Lipid Accumulation. Experiment 2016, 359, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigalou, C.; Vallianou, N.; Dalamaga, M. Autoantibody Production in Obesity: Is There Evidence for a Link Between Obesity and Autoimmunity? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2020, 9, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strowig, T.; Henao-Mejia, J.; Elinav, E.; Flavell, R. Inflammasomes in health and disease. Nature 2012, 481, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Tschöpe, C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, H.; Che, R.; Zhang, A. Inflammasomes in the Pathophysiology of Kidney Diseases. Kidney Dis. 2015, 1, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, J.L.; Davidson, M.T.; Kurishima, C.; Vega, R.B.; Powers, J.C.; Matsuura, T.R.; Petucci, C.; Lewandowski, E.D.; Crawford, P.A.; Muoio, D.M.; et al. The failing heart utilizes 3-hydroxybutyrate as a metabolic stress defense. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 4, e124079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youm, Y.-H.; Nguyen, K.Y.; Grant, R.W.; Goldberg, E.L.; Bodogai, M.; Kim, D.; D’Agostino, D.; Planavsky, N.; Lupfer, C.; Kanneganti, T.-D.; et al. The ketone metabolite β-hydroxybutyrate blocks NLRP3 inflammasome–mediated inflammatory disease. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, H.R.; Kim, D.H.; Park, M.H.; Lee, B.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, E.K.; Chung, K.W.; Kim, S.M.; Im, D.S.; Chung, H.Y. β-Hydroxybutyrate suppresses inflammasome formation by ameliorating endoplasmic reticulum stress via AMPK activation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 66444–66454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Xie, M.; Li, Q.; Xu, X.; Ou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Yu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Liang, Y.; et al. Targeting Mitochondria-Inflammation Circuit by β-Hydroxybutyrate Mitigates HFpEF. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liakos, A.; Tsapas, A.; Bekiari, E. Some glucose-lowering drugs reduce risk for major adverse cardiac events. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, JC9–JC10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiri-Ansari, N.; Nikolopoulou, C.; Papoutsi, K.; Kyrou, I.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Kyriakopoulos, G.; Chatzigeorgiou, A.; Kalotychou, V.; Randeva, M.S.; Chatha, K.; et al. Empagliflozin Attenuates Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) in High Fat Diet Fed ApoE(-/-) Mice by Activating Autophagy and Reducing ER Stress and Apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.; Meagher, P.; Connelly, K.A. Effect of Empagliflozin and Liraglutide on the Nucleotide-Binding and Oligomerization Domain-Like Receptor Family Pyrin Domain-Containing 3 Inflammasome in a Rodent Model of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Can. J. Diabetes 2020, 45, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzu, T.; Yokoyama, H.; Itoh, H.; Koya, D.; Nakagawa, A.; Nishizawa, M.; Maegawa, H.; Yokomaku, Y.; Araki, S.-I.; Abiko, A.; et al. Elevated serum levels of interleukin-18 in patients with overt diabetic nephropathy: effects of miglitol. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2010, 15, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Devarapu, S.K.; Motrapu, M.; Cohen, C.D.; Lindenmeyer, M.T.; Moll, S.; Kumar, S.V.; Anders, H.-J. Interleukin-1β Inhibition for Chronic Kidney Disease in Obese Mice With Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, K.; Bock, F.; Dong, W.; Wang, H.; Kopf, S.; Kohli, S.; Al-Dabet, M.M.; Ranjan, S.; Wolter, J.; Wacker, C.; et al. Nlrp3-inflammasome activation in non-myeloid-derived cells aggravates diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2015, 87, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Lu, D.; Guo, R. Electro-Acupuncture Protects Diabetic Nephropathy-Induced Inflammation Through Suppression of NLRP3 Inflammasome in Renal Macrophage Isolation. Endocrine, Metab. Immune Disord. - Drug Targets 2021, 21, 2075–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Meng, X.-F.; Zhang, C. Inflammasome activation in podocytes: a new mechanism of glomerular diseases. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 69, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Shi, Y.; Han, W.; Song, S.; Mu, L.; Du, C.; Shi, Y. Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome ameliorates podocyte damage by suppressing lipid accumulation in diabetic nephropathy. Metabolism 2021, 118, 154748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, C.; Wu, W.; Tang, A.; Luo, N.; Tan, Y. lncRNA GAS5/miR-452-5p Reduces Oxidative Stress and Pyroptosis of High-Glucose-Stimulated Renal Tubular Cells. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obesity: Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 2609–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, H.; Peng, R.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Sun, Y.; Peng, H.-M.; Liu, H.-D.; Yu, L.-J.; Li, A.-L.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Jiang, W.-H.; et al. LincRNA-Gm4419 knockdown ameliorates NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tung, C.; Hsu, Y.; Shih, Y.; Chang, P.; Lin, C. Glomerular mesangial cell and podocyte injuries in diabetic nephropathy. Nephrology 2018, 23, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, X.; Li, L.; Ma, T.; Shi, M.; Yang, Y.; Fan, Q. A small molecule inhibitor MCC950 ameliorates kidney injury in diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obesity: Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhang, X.; Luan, J.; Bian, Q.; Ding, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Song, P.; et al. Interleukin-22 ameliorated renal injury and fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Han, W.; Song, S.; Du, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, N.; Wu, H.; Shi, Y.; Duan, H. NLRP3 deficiency ameliorates renal inflammation and fibrosis in diabetic mice. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2018, 478, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares JL, S.; Fernandes, F.P.; Patente, T.A.; Monteiro, M.B.; Parisi, M.C.; Giannella-Neto, D.; Corrêa-Giannella, M.L.; Pontillo, A. Gain-of-function Variants in NLRP1 Protect against the Development of Diabetic Kidney Disease: NLRP1 Inflammasome Role in Metabolic Stress Sensing? Clin. Immunol. 2018, 187, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F.; Kolb, R.; Pandey, G.; Li, W.; Sun, L.; Liu, F.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W. Involvement of the NLRC4-Inflammasome in Diabetic Nephropathy. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0164135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, P.; Zhuang, J.; Zou, J.; Li, H.; Shuai, P.; Xu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Kou, W.; Ji, S.; Peng, A.; et al. NLRC5 deficiency ameliorates diabetic nephropathy through alleviating inflammation. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 1070–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Shi, X.; Yang, L.; Hua, F.; Ma, J.; Zhu, W.; Liu, X.; Xuan, R.; Shen, Y.; et al. Metformin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and cell pyroptosis via AMPK/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Aging 2020, 12, 24270–24287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lech, M.; Avila-Ferrufino, A.; Skuginna, V.; Susanti, H.E.; Anders, H.-J. Quantitative expression of RIG-like helicase, NOD-like receptor and inflammasome-related mRNAs in humans and mice. Int. Immunol. 2010, 22, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komada, T.; Chung, H.; Lau, A.; Platnich, J.M.; Beck, P.L.; Benediktsson, H.; Duff, H.J.; Jenne, C.N.; Muruve, D.A. Macrophage Uptake of Necrotic Cell DNA Activates the AIM2 Inflammasome to Regulate a Proinflammatory Phenotype in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komada, T.; Muruve, D.A. The role of inflammasomes in kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 501–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valiño-Rivas, L.; Cuarental, L.; Nuñez, G.; Sanz, A.B.; Ortiz, A.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D. Loss of NLRP6 expression increases the severity of acute kidney injury. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2019, 35, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Cai, Y.; Xu, W.; Yin, Z.; Gao, X.; Xiong, S. AIM2 Facilitates the Apoptotic DNA-induced Systemic Lupus Erythematosus via Arbitrating Macrophage Functional Maturation. J. Clin. Immunol. 2013, 33, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, J.; Zhang, L.; Pan, J.; Ma, S.; Yu, X.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Du, W. AIM2 Mediates Inflammation-Associated Renal Damage in Hepatitis B Virus-Associated Glomerulonephritis by Regulating Caspase-1, IL-1β, and IL-18. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; Zhang, J.; Wu, D.; Shi, J.; Kuang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Q.; Chen, B.; Kan, C.; Sun, X.; et al. Empagliflozin Attenuates Obesity-Related Kidney Dysfunction and NLRP3 Inflammasome Activity Through the HO-1–Adiponectin Axis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 907984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benetti, E.; Mastrocola, R.; Vitarelli, G.; Cutrin, J.C.; Nigro, D.; Chiazza, F.; Mayoux, E.; Collino, M.; Fantozzi, R. Empagliflozin Protects against Diet-Induced NLRP-3 Inflammasome Activation and Lipid Accumulation. Experiment 2016, 359, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnbaum, Y.; Bajaj, M.; Yang, H.-C.; Ye, Y. Combined SGLT2 and DPP4 Inhibition Reduces the Activation of the Nlrp3/ASC Inflammasome and Attenuates the Development of Diabetic Nephropathy in Mice with Type 2 Diabetes. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2018, 32, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Q.; Shi, C.; Lv, Y.; Wang, L.; Luo, J.; Jiang, L.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Y. SGLT2 inhibitor counteracts NLRP3 inflammasome via tubular metabolite itaconate in fibrosis kidney. FASEB J. 2021, 36, e22078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahara, A.; Takasu, T.; Yokono, M.; Imamura, M.; Kurosaki, E. Characterization and comparison of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacologic effects. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 130, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, K.K.; DeSilva, S.; Abbruscato, T.J. The Role of Glucose Transporters in Brain Disease: Diabetes and Alzheimer's Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 12629–12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koepsell, H. Glucose transporters in the brain in health and disease. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2020, 472, 1299–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enerson, B.E.; Drewes, L.R. The Rat Blood—Brain Barrier Transcriptome. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 26, 959–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Wen, S.; Gong, M.; Yuan, X.; Xu, D.; Wang, C.; Jin, J.; Zhou, L. Dapagliflozin Activates Neurons in the Central Nervous System and Regulates Cardiovascular Activity by Inhibiting SGLT-2 in Mice. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obesity: Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 2781–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A.; Pal, G.K.; Ananthanarayanan, P.H.; Pal, P. Role of Ventromedial hypothalamus in high fat diet induced obesity in male rats: Association with lipid profile, thyroid profile and insulin resistance. Ann. Neurosci. 2014, 21, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, N.; Jeltema, D.; Duan, Y.; He, Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: An Overview of Mechanisms of Activation and Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Fu, J. Novel Insights Into the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2019, 8, e012219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heijden, T.; Kritikou, E.; Venema, W.; van Duijn, J.; van Santbrink, P.J.; Slütter, B.; Foks, A.C.; Bot, I.; Kuiper, J.; T, W.; et al. NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibition by MCC950 Reduces Atherosclerotic Lesion Development in Apolipoprotein E–Deficient Mice—Brief Report. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1457–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hierro-Bujalance, C.; Infante-Garcia, C.; del Marco, A.; Herrera, M.; Carranza-Naval, M.J.; Suarez, J.; Alves-Martinez, P.; Lubian-Lopez, S.; Garcia-Alloza, M. Empagliflozin reduces vascular damage and cognitive impairment in a mixed murine model of Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejera, D.; Mercan, D.; Sanchez-Caro, J.M.; Hanan, M.; Greenberg, D.; Soreq, H.; Latz, E.; Golenbock, D.; Heneka, M.T. Systemic inflammation impairs microglial Aβ clearance through NLRP 3 inflammasome. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e101064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonnemann, N.; Hosseini, S.; Marchetti, C.; Skouras, D.B.; Stefanoni, D.; D’alessandro, A.; Dinarello, C.A.; Korte, M. The NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor OLT1177 rescues cognitive impairment in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 32145–32154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-Y.; Iskander, C.; Wang, C.; Xiong, L.Y.; Shah, B.R.; Edwards, J.D.; Kapral, M.K.; Herrmann, N.; Lanctôt, K.L.; Masellis, M.; et al. Association of Sodium–Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors With Time to Dementia: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2022, 46, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Geladari, E.; Kazazis, C.E. SGLT-2 inhibitors: Their pleiotropic properties. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2017, 11, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Bajaj, M.; Yang, H.-C.; Perez-Polo, J.R.; Birnbaum, Y. SGLT-2 Inhibition with Dapagliflozin Reduces the Activation of the Nlrp3/ASC Inflammasome and Attenuates the Development of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy in Mice with Type 2 Diabetes. Further Augmentation of the Effects with Saxagliptin, a DPP4 Inhibitor. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2017, 31, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, Y.; Tran, D.; Bajaj, M.; Ye, Y. DPP-4 inhibition by linagliptin prevents cardiac dysfunction and inflammation by targeting the Nlrp3/ASC inflammasome. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2019, 114, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).