1. Introduction

Hypertension in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) poses a significant challenge due to the complex interplay between the two conditions. Hypertension can damage the kidneys, which contributes to the progression of CKD, subsequently exacerbating hypertension and increasing the risk of cardiovascular events and mortality [

1,

2]. Key factors in this pathological relationship include the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, oxidative stress, and inflammation, all of which significantly contribute to the onset and progression of both conditions [3-5]. Implementing comprehensive therapeutic strategies that encompass strict blood pressure control, pharmacological therapies, lifestyle modifications, and management of underlying causes is crucial for addressing this intricate interaction and improving patient prognosis [

6]. While treating hypertension in CKD is already challenging, understanding its mechanisms is essential for applying an integrated approach that enhances patient outcomes [

4,

7] .

Numerous studies have linked nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation to various inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, and atherosclerosis, where it regulates key processes in the development of atherosclerotic plaques [

8,

9]. Evidence suggests that abnormal activation of NF-κB may significantly influence the pathogenesis of arterial hypertension and kidney damage [

10,

11]. NF-κB serves as a critical regulator of gene expression, consisting of five dimers in both homo- and hetero-forms, including RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, NF-κB1 (p50 subunit and precursor p105), and NF-κB2 [

12,

13]. Henke et al. contributed to elucidate the roles of these proteins in autoimmune diseases, tumorigenesis, and cardiovascular and renal disorders, as pivotal in the inflammatory response and the pathogenesis of various conditions [

14]. This indicates that the NF-κB pathway may represent a promising therapeutic target across multiple diseases [

15]. Notably, NF-κB is central to regulate inflammation, a vital biological process in defending the body against pathogens and injuries [

9,

16]. Other reports suggest that abnormal activation of NF-κB may significantly influence the pathogenesis of arterial hypertension and kidney damage [

10,

11].

Some strategies to modulate NF-κB activity includes the use of compounds such as resveratrol and curcumin, Japonicone A, which have been explored in silico studies [12,17-23]. These compounds exhibit anti-inflammatory properties by inhibiting NF-κB activation.

Understanding the role of NF-κB in inflammation and its potential involvement in hypertension and kidney damage opens new avenues for developing more effective therapies. The design of drugs specifically targeting NF-κB activity could become a viable alternative for improving the quality-of-life patients. In this context, sildenafil, a drug primarily marketed for erectile dysfunction, has also been used to manage pulmonary arterial hypertension due to its ability to inhibit phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) and mitigate endothelial damage through a well-established mechanism [

24]. Other reports suggest that sildenafil possesses anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective actions, likely through the modulation of various transcription factors, including NF-κB [

25]. Given NF-κB's significant role in inflammation and the pathogenesis of cardiovascular and renal diseases, researchers have extensively examined the potential for direct interaction and inhibition of NF-κB by various compounds [12, 17-22], including natural substances known for their antioxidant properties, such as resveratrol. This preliminary exploration underscores the potential of targeting NF-κB in therapeutic strategies for inflammatory and cardiovascular conditions [

26].

Base on, given sildenafil’s reported anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects, and the incomplete understanding of its interaction with NF-κB, exploring other pharmacological pathways is crucial. This will refine its clinical use and enhance our understanding of its role in inflammation control as a multi-target therapeutic agent [

27,

28]. Notably, sildenafil exhibits lipophilicity like compounds identified as potential NF-κB inhibitors, such as resveratrol, which may facilitate the entry of such compounds into subcellular compartments [

12,

21]. Therefore, we hypothesize that sildenafil could interact with NF-κB, inducing conformational or structural changes that disrupt and inhibit the biological activity of this transcription factor, leading to a reduction in inflammation. Our previous studies in animal models have demonstrated that sildenafil treatment can improve and prevent hypertension, enhance renal function, and reduce histological damage, inflammation, and apoptosis, while also preserving the integrity of renal capillaries [

29,

30]. Furthermore, sildenafil has been shown to reverse endothelial dysfunction and decrease renal oxidative stress and macrophage accumulation [

30,

31]. Given that NF-κB is a key regulator of inflammatory gene expression, with its activation stimulating the expression of genes associated with inflammation in conditions such as inflammatory lesions, atherosclerosis, and kidney damage, cell and animal models suggest that specific inhibition of NF-κB in endothelial cells could mitigate kidney damage caused by hypertension without affecting blood pressure levels [

14].

It has been proposed that drugs with significant anti-inflammatory activity can bind to and influence the recognition and biological function of various proteins in the inflammatory cascade, including NF-κB, by inducing changes in their conformation, structure, size, and shape [

19]. The beneficial effects observed from the modulation of hypertension, inflammation, and kidney damage by drugs like sildenafil suggest that this compound may possess an alternative molecular mechanism of action linked to the interaction with and disruption of the geometric, structural, and volumetric properties of NF-κB. Here, immunohistological analyses were conducted on biopsies from two previously described experimental models to assess the effects of sildenafil on kidney damage and hypertension [

29,

30]. The interaction and possible structural changes induced by sildenafil and this important protein in the regulation of the inflammatory cascade, such as NF-κB, were evaluated

in silico.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Data Set and Database Screening

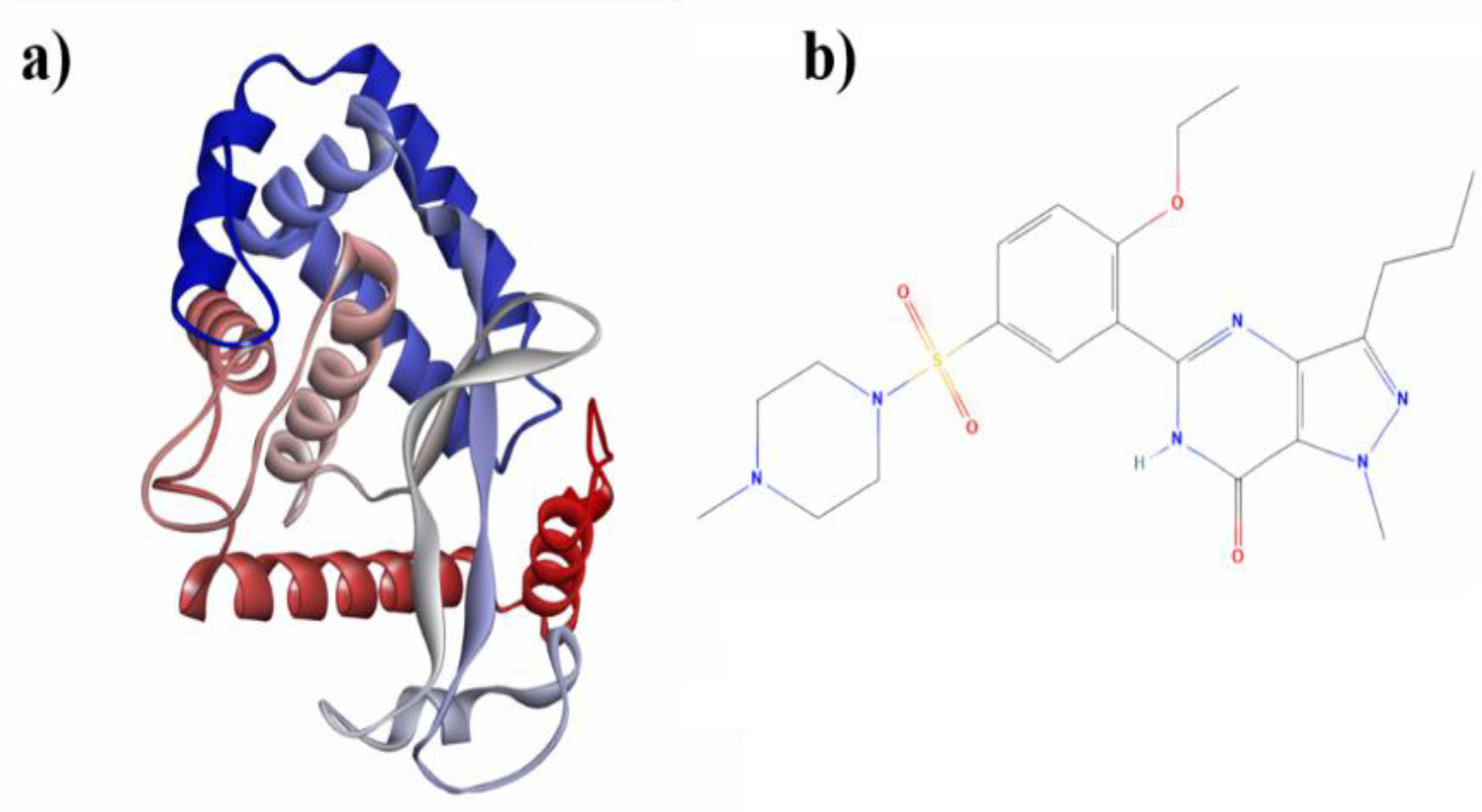

The three-dimensional crystal structures of NF-κB (Rel A, p65) (PDB ID: 4Q3J) [

32] (

Figure 1a) were obtained from the Protein Data Bank database (

http://www.rcsb.org/). The raw PDB file of the protein was then prepared for docking studies. The structures of the compound Sildenafil (CID_135398744) (

Figure 1b) were selected from the PUBCHEM database (

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) [

33]. The Molegro Molecular Viewer (MMV) [

34] and Discovery Studio Visualizer BIOVIA [

35] packages were used for visualization and file preparation.

2.2. Molecular Docking, Theoretical Inhibition Constant (Ki), and Molecular Dynamics (MD) Analysis

CB-Dock (

http://clab.labshare.cn/cb-dock/), a protein-ligand docking tool that automatically finds potential binding sites on a protein, calculates their center and size to fit the ligand molecule and then uses AutoDock Vina to perform the docking simulation, was employed [

36,

37]. Subsequently, the best poses predicted by CB-Dock were reclassified using a combination of molecular mechanics with the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) method and continuous solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), or MM/PBSA, using the fastDRH server (

http://cadd.zju.edu.cn/fastdrh/overview). Calculations based on the relative binding energy predicted by MM/PBSA [

38,

39] were also used to calculate the suggested kinetic parameters for competitive inhibition, based on the relationship between the free binding energy (ΔG), the universal gas constant, and the absolute reaction temperature[

40]. The inhibitor concentration required to achieve 50% inhibition (IC50) in molar concentration (M) was theoretically calculated using the Dixon method and the BotDB web tool (

https://bioinfo-abcc.ncifcrf.gov/IC50_Ki_Converter/index.php), assuming competitive inhibition as suggested in [

40]. From the Ki values, the IC50 values for competitive inhibition of a specific substrate can be estimated. This approach provides an estimate of the IC50 values for competitive inhibition of a specific substrate based on the Ki values [

41]. In this study, a hypothetical 1:1 relationship between the "substrate" (NF-κB) and the inhibitor sildenafil was considered to simulate the molecular docking conditions and avoid concentration-dependent associations, assuming structural similarities between the ligand and the substrate. For comparative purposes, experimental values of inhibitory concentration in molar expression were collected for other compounds considered as NF-κB inhibitors, as reported [12, 18-21]. The inhibition was evaluated in terms of Ki, IC50, and pIC50.

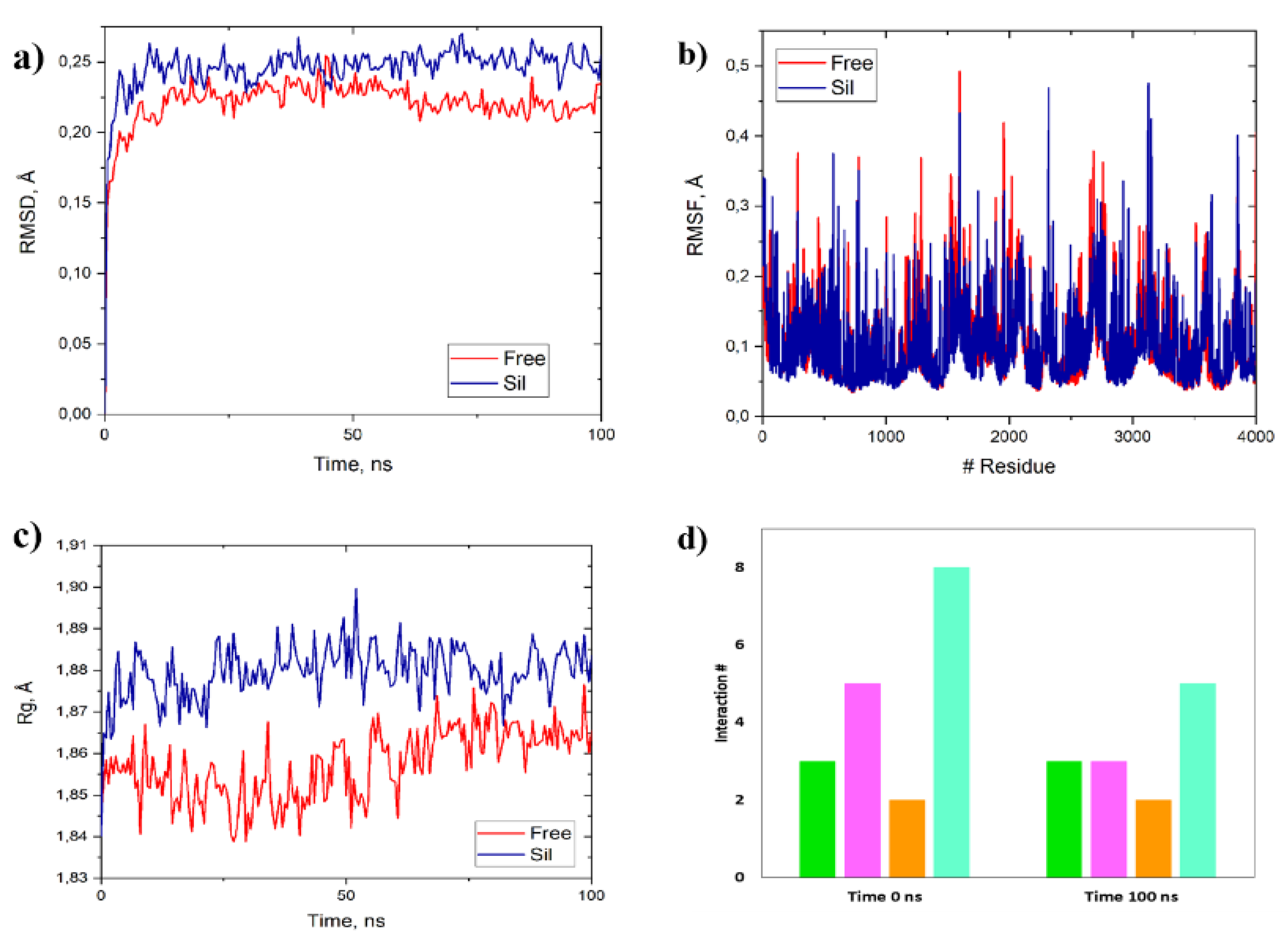

The complexes were used in MD simulations to evaluate the stability of NF-κB and sildenafil and select low-energy conformations to study the deformability and conformational and energy-structural changes of NF-κB in the presence of each ligand (sildenafil). These simulations were performed in an explicit, solvated and neutralized water system at a molar density like physiological serum. Automatic generation of topology files for sildenafil and NF-κB was performed using GROMACS with the MyPresto Portal graphical interface, employing the Amber99SB-ILDN force fields and the TIP3P water model. For each complex, minimization procedures were carried out to relax the MD system, through three phases: relaxation, equilibrium and finally production under isothermal-isobaric conditions to stabilize the system at 1 bar and 300 K for 100 ns, obtaining minimum energy structures for subsequent analyses according to the recommendations [40, 42-44]. From the minimum energy structures generated by MD, empirical data were obtained for 1) binding energy using MM/PBSA with fastDRH, 2) root mean square deviation (RMSD) (

Figure 3A), 3) root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) (

Figure 3B), 4) Radius of gyration (Rg) (

Figure 3c), and 5) depletion of hydrophobic, electrostatic and hydrogen bond interactions (

Figure 3d) ) as previously suggested [40, 42-44].

2.3. Conformational Changes in Molecular Complex Using Statistical Potentials and Elastic Network Models

To validate the results obtained by classical molecular dynamics in this work, the minimum energy structures at 100ns of free NF-κB and in complex with Sildenafil were subjected to multiple "coarse-grained" molecular dynamics methods, which consider simplified representations of the protein to calculate multiple structural biochemical parameters related to its function [41, 42]. In this sense, elastic network models (ENM) [

45] were used, which allow for predicting vibrational dynamic aspects of the minimum energy structures of a protein[

45,

46] through the different servers.

2.4. Frustratometer

The magnitude of local frustration obtained for each docked structure was calculated using the Frustratometer Server (

http://frustratometer.qb.fcen.uba.ar/). This server employs the Water-mediated, Structure, and Energy-based Association Memory (AWSEM) model with a non-additive coarse-grained force field that reduces computational costs compared to all-atom models. This method quantifies the energy contribution of each pair of amino acids in the protein relative to structural decoys with varying identity, distance, and residue density, in a normalized frustration index [

46,

47].

2.5. SPECTRUS

The SPECTRUS (Subdivision based on Spectra of Rigid Units) tool (

http://spectrus.sissa.it/#home) was used to perform a decomposition into quasi-rigid regions or domains (Q) of each free and bound peptide, based on the analysis of distance fluctuations between pairs of amino acids. SPECTRUS employs the Elastic Network Model (ENM), which, thanks to the specific properties of each complex and its free energy landscape, can reliably reproduce structural fluctuations. The method of decomposition into quasi-rigid regions is based on the idea that in genuinely rigid (conserved) regions, the distances between two constituent points are strictly maintained during the motion in space by the MD simulation [

47,

48].

2.6. SWOTein

The SWOTein (Strengths and Weaknesses of Proteins) tool (

http://babylone.3bio.ulb.ac.be/SWOTein/index.php) was used [

49], which is an algorithm based on the "statistical potentials" approach that allows studying the stability of protein biomolecules in relation to fluctuations in their energy landscape, both in the free state and in docked states. This approach analyzes the contributions of the interresidue distance, solvent accessibility and backbone torsion angles to the overall folding free energy. Additionally, it relates the free energy of a conformation to the probability of observing that conformation. SWOTein uses a simplified coarse-grained representation of the structures under study and has been previously used to investigate the biophysical properties of proteins, such as interactions with other biomolecules [

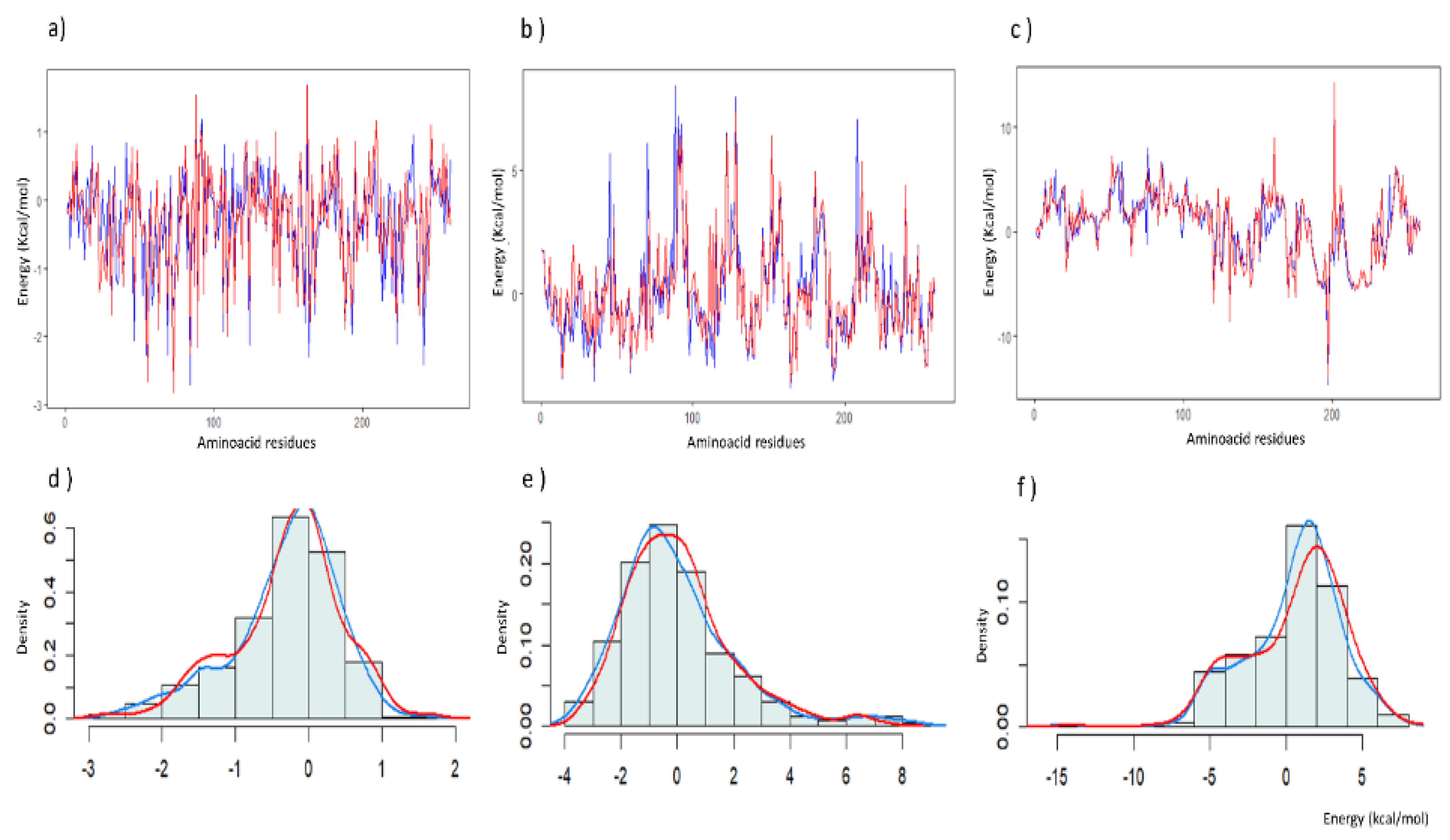

48]. The contribution of the amino acid residues to the overall folding free energy in wild-type NF-κB and NF-κB+Sildenafil was evaluated from the minimum energy structures (100 ns) obtained in the dynamic simulation. R statistics v4.4.0 [

50] was used to perform a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate the effect of the sildenafil complex on the structure of the NF-κB protein. The factors analyzed were: (a) NF-κB protein with two levels (free and with Sildenafil), (b) amino acid residues with 259 levels corresponding to each of the residues of the protein. The statistical potential of distance, solvent accessibility and torsion angle obtained using the SWOTein software was used as the dependent variable for each amino acid residue. The two-way ANOVA allowed determining if there are significant differences in the statistical potential of distance, solvent accessibility and torsion angle between the free NF-κB proteins and NF-κB with sildenafil, if at least one amino acid residue presents a different energy contribution of distance compared to the others. A significance level of 0.05 was considered for all statistical tests.

2.7. webPSN

Another computational model that allows studying the structural dynamics of proteins is based on the Protein Structure Network (PSN) method (

http://webpsn.hpc.unimo.it/wpsn3.php). This method considers each amino acid as nodes connected by links, defined by their non-covalent interaction strength. This methodology provides information related to protein folding, allostery, and protein-protein binding stability [

51,

52].

2.8. Volumetric Analysis of Internal Cavities of the NF-κB Protein and the NF-κB + Sildenafil Complex

The MOLE 2.5 program (

https://mole.upol.cz/) was employed, a widely used algorithm for the rapid and fully automated location and characterization of channels, tunnels and pores in simple and complex biomacromolecular structures. This method was applied in its default configuration, with a 5 Å probe and 1.1 Å interior threshold to estimate the number and volume of internal cavities in the minimum energy conformation at 100 ns for the free NF-κB protein and for the NF-κB + sildenafil complex. With the volume of each internal cavity V_v estimated for the free protein and the protein-ligand complex, the root mean square of the volume fluctuation 〈〖δV〗_v^2 〉^(1/2) was calculated [52-56].

2.9. Experimental Rat Models

Biopsies obtained from previous experiments were evaluated, in which sildenafil was administered at a daily dose of 2.5 mg/Kg in two experimental models of hypertension and kidney damage: 1) Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat (SHR) model of arterial hypertension and 2) 5/6 nephrectomy (5/6Nx) model of chronic kidney disease. Using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase methodology, lymphocytes (CD5-positive cells), macrophages (ED-1-positive cells), and the expression of the 65-kDa DNA-binding subunit of the transcription factor NF-κB were identified, employing previously described protocols. Additionally, glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial damage were classified using a scoring index, as reported in our previous studies [29-31, 57].

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation

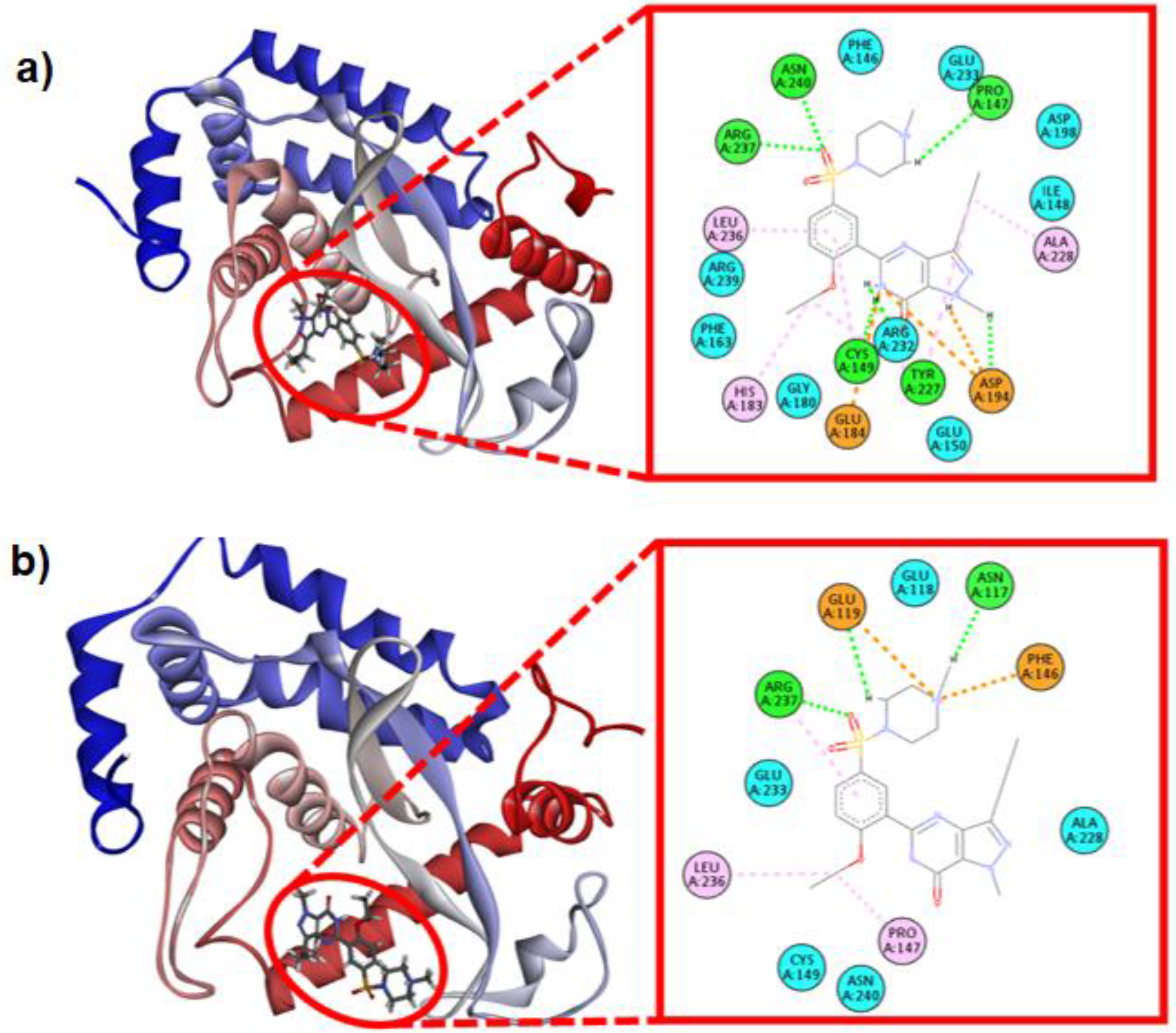

As shown in

Table 1, a thermodynamically favorable molecular complex was formed with sildenafil according to the scoring function in CBDock and more refined rescoring calculations using MM/PBSA before and after the MD simulation [

38,

39]. Sildenafil exhibited a favorable thermodynamic binding (ΔG ≈ -7.8 kcal/mol), similar to other reported compounds [12,18-21] represented in

Table 1, and was also stable over time when calculating the molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann solvent-accessible surface energy. Furthermore, the binding energy increased after the dynamics (0 ns: -1.84, 100 ns: -25.63) with a 73% success rate, showing a greater number of interactions, especially of a hydrophobic nature (

Figure 2). Inhibition was predicted in terms of Ki, IC50, and pIC50, showing that sildenafil has a similar inhibitory potency to the thermodynamic interaction reported for resveratrol, as shown in

Table 1. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using the GROMACS computational package were employed to study the stability and structural changes induced by sildenafil in the NF-κB complex for 100 ns. A low-energy conformation of the complex was identified, and its structural (RMSD, RMSF, Rg), energetic (MM/PBSA), and interaction (hydrophobic, electrostatic, and hydrogen bond) properties were analyzed [40, 58, 59]. The results revealed that, in addition to maintaining favorable and stable energy over time (

Table 1,

Figure 3).

3.2. Statistical Potentials and Elastic Network Models

To validate the results obtained by classical molecular dynamics in this work, the minimum energy structures at 100ns of free NF-κB and in complex with Sildenafil were subjected to multiple "coarse-grained" molecular dynamics methods, which consider simplified representations of the protein to calculate multiple structural biochemical parameters related to its function. In this sense, elastic network models (ENM) were employed, which allow for predicting vibrational dynamic aspects of the minimum energy structures of a protein [

42,

45], through the SPECTRUS servers (

http://spectrus.sissa.it/) [

60] , which indicated an increase in the most probable distribution of quasi-rigid domains of the protein induced by sildenafil, implying an increase in the distribution of discrete regions of amino acids that exhibit collective dynamic movements; and webPSN (

http://webpsn.hpc.unimore.it/), which determined the intramolecular energetic interactions of NF-κB in the form of communication pathways between amino acids based on collective dynamic movements related to protein functionality, observing an increase in the number of the aforementioned communication pathways along with a decrease in the intramolecular forces driving these interactions (

Table 2). Additionally, the Analysis of Variance revealed that the sildenafil complex has a significant impact on the structure of the NF-κB protein. Statistically significant differences were found in the statistical potential of distance (F=10.05; p<0.01), solvent accessibility (F=11.03; p<0.01) and torsion angle (F=11.30; p<0.01) between the free NF-κB protein and the NF-κB protein with the Sildenafil complex (p-value < 0.05). The data indicates that there are differences in the energy contribution of amino acid residues before and after interaction with sildenafil, altering the three-dimensional structure of NF-κB in terms of atomic distances, solvent accessibility, and torsion angles. As shown in

Figure 4, there are regions of the structure that exhibit significant changes towards values classified by SWOTein as having low to high stability in certain protein regions after the complex is formed, such as the potential torsion angle around residues 200-210 (

Figure 4d). These changes can also be observed in the density of data grouped into the stability categories, particularly for the potential solvent accessibility (

Figure 4e) and torsion angle (

Figure 4f).

3.3. Volumetric Analysis of Internal Cavities of NF-κB Protein and NF-κB + Sildenafil Complex

In this work, the MOLE 2.5 program (

https://mole.upol.cz/) was employed for this analysis [

60]. It was found that the NF-κB protein has a fluctuation in the volume of internal cavities 〈〖δV〗_v^2 〉^(1/2) of 35.2 Å3/molecule, and in the complex with sildenafil, the fluctuation in the volume of internal cavities increases to 52 Å3/molecule. Therefore, the fluctuation in the volume of internal cavities of the NF-κB + sildenafil complex increased by approximately 47.73%.

3.4. Assessing the Therapeutic Potential of Sildenafil in Treating Hypertension and Kidney Damage in Experimental Rat Models

The results obtained after analyzing the biopsies correspond to what was previously reported [29, 30]. A decrease in cellular infiltration and renal damage was observed in the group treated with sildenafil, as well as an improvement in renal damage and arterial hypertension. Additionally, the expression of the 65-kDa DNA-binding subunit of the transcription factor NF-κB was evaluated, and a decrease in the expression of NF-κB positive cells was observed in the groups treated with sildenafil, which could represent a reduction in inflammation in these models. The results are shown in

Table 3.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The in-silico results indicate that sildenafil induces conformational and structural changes in the transcription factor NF-κB (See

Figure 3). These changes may contribute to the reduction in inflammation observed in both previous and present experimental findings obtained from the biopsy analyses. Molecular docking using CB-Dock showed that a thermodynamically favorable complex is formed between sildenafil and NF-κB, with a relative binding energy (ΔG) of approximately -7.8 kcal/mol. This value is higher compared to other reported compounds as NF-κB inhibitors, such as resveratrol, curcumin, and tangeretin [12,18-21] (see

Table 1). MM/PBSA calculations revealed that the binding energy remained around -25.63 kcal/mol after 100 ns of MD simulation, with a 73% success rate in the predictions. This indicates a stable binding interaction between sildenafil and NF-κB, characterized by a higher number of interactions, particularly of a hydrophobic nature. Based on the relative binding energy predicted by MM/PBSA, kinetic parameters such as the inhibition constant (Ki) and the median inhibitory concentration (IC50) were estimated. For sildenafil, a theoretical Ki of 1.92 x 10-6 M and an IC50 of 0.137 μM were calculated, suggesting inhibition of NF-κB. These results suggest that sildenafil can directly interact with NF-κB, inducing conformational and structural changes that may alter its transcriptional activity and consequently reduce the expression of inflammatory genes. This is an additional mechanism, beyond the inhibition of phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5), through which sildenafil exerts its anti-inflammatory effects. In this study, a hypothetical 1:1 ratio of "substrate" (NF-κB) to inhibitor (sildenafil) was considered for molecular docking simulations to avoid concentration-dependent associations, assuming structural similarities between the ligand and substrate. For comparative purposes, experimental inhibitory concentration values expressed in molar terms were also obtained for reported compounds. The inhibition constant (Ki) was derived from the reported binding energy [12,18-21]. In this context, inhibition was predicted in terms of Ki, IC50, and pIC50, indicating that sildenafil exhibits a thermodynamic interaction behavior similar to that of resveratrol, as shown in

Table 1. Both free NF-κB and NF-κB complexed with sildenafil were submitted to 100 ns of all-atom molecular dynamics simulations, indicating that sildenafil induces a loss of conformational stability in the protein. This implies an alteration in the structure of NF-κB, affecting its biological function (

Figure 3A-C). The overall decrease in hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions displayed in

Figure 3D, coupled with the increase in the magnitude of binding free energy as predicted by MM/PBSA, shown in

Table 1, suggests a high complex binding stability due to a redistribution of protein-ligand interactions towards a more favorable bonding conformation. This result may be attributed to several factors: a) improved orientation and positioning of hydrogen bond acceptor and donor groups of the ligand and/or cavity residues. If the orientation of these groups becomes more favorable, the capacity for hydrogen bond formation increases, potentially leading to stronger interactions between the ligand and the protein's cavity residues; and b) a shortening of distances between oppositely charged groups. When the distances between charged groups decrease, the electrostatic interactions between them become stronger. However, this could also generate electrostatic repulsions between similarly charged groups, which may reduce the overall interaction between the molecules. These analyses elucidated the effects of the ligand on the stability, flexibility, and conformation of the protein, providing valuable insights into the mechanisms of molecular interaction. Additionally, methods based on the kinetic and thermodynamic principles of protein folding were employed through the Frustratometer and SWOTein servers. Both algorithms calculated drug-induced losses in stability due to an increase in the magnitude of highly frustrated (low stability) contacts between residues and shifts toward less favorable free energy values for the three statistical potentials considered (

Table 2), correlating with the results presented in

Figure 3A-C. Notably, an increase in stability was observed in the residues involved in the protein-sildenafil interaction after docking, evidenced by a decrease in highly frustrated contacts, which may relate to the enhanced protein-ligand affinity observed in

Table 1 following classical dynamics simulations.

Sildenafil may induce structural changes in NF-κB, this alteration in structure could lead to a decrease in the expression of this molecule in the groups treated with the drug and an overall improvement in the disease (see

Table 3). Similar results were obtained when examining distance, solvent accessibility, and torsion angles derived from statistical potentials. The data indicate that the sildenafil complex significantly impacts the structure of the NF-κB protein, differentially altering its statistical potential in terms of distance, accessibility, and torsion based on the specific amino acid residues considered. This suggests that the sildenafil complex uniquely affects the various amino acid residues that comprise the NF-κB protein. This preliminary analysis of the differential energy contributions of amino acid residues before and after complex formation emphasizes the importance of studying drug-protein interactions at the structural level to better understand their biological effects. Furthermore, our study reveals a significant 47.73% increase in the fluctuation of the internal cavity volumes of the NF-κB complex following interaction with sildenafil. This notable change suggests that sildenafil induces substantial alterations in the distribution of cavities within the protein, triggering important conformational changes. These structural modifications could directly impact the stability of NF-κB, potentially affecting its biological recognition function. Indeed, previous studies have shown that partially disordered states of globular proteins, characterized by a reduction in cavities, lead to increased instability [52-56]. It has also been established that changes in volumetric properties and the distribution of internal cavities significantly influence the structural flexibility, stability, and biological recognition function of proteins [

61,

62,

63]. Our research, consistent with these findings, provides valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms by which sildenafil modulates the activity of NF-κB [52-56]. This finding opens new avenues for developing therapeutic strategies that manipulate NF-κB activity by modulating its structure and function. Sildenafil, already approved for other medical uses, may possess untapped therapeutic potential in treating diseases associated with NF-κB dysfunction. In summary, our study underscores the critical role of internal cavities in the stability and function of NF-κB, revealing sildenafil's potential to modulate its activity through conformational changes.

This study investigates the potential of sildenafil to modulate NF-κB activity and reduce inflammation in the context of hypertension and chronic kidney disease. From a combination of computational techniques and experimental validation, the main findings are: (1) Molecular docking and MD simulations revealed that sildenafil induces conformational changes in NF-κB, reducing its activity and showing its inhibitory potency comparable to known anti-inflammatory compounds like resveratrol, and (2) in hypertensive and kidney-damaged rat models, sildenafil treatment significantly decreased cellular infiltration, kidney damage, and NF-κB expression, confirming its anti-inflammatory properties. The analysis of biopsies from the previously described experimental models reveals that the data align with prior reports. The inhibition of NF-κB by sildenafil likely contributes to its ability to decrease the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, thereby reducing the inflammatory milieu. Sildenafil induces structural changes in the transcription factor NF-κB, these changes may contribute to a reduction in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies investigate the effects of sildenafil on the structural changes of cytokines involved in the inflammatory cascade. This research could open new avenues for its therapeutic use and deepen our understanding of its mechanisms of action. In conclusion, this preliminary study indicates that Sildenafil shows promise as a therapeutic agent for managing hypertension and chronic kidney disease by modulating NF-κB activity and reducing inflammation. These findings suggest potential repurposing of sildenafil for comprehensive treatment of these conditions. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms. Additionally, it is essential to validate these findings in clinical settings and to investigate potential long-term effects and optimal dosing strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yasmir Quiroz-Perozo; Data curation, Yasmir Quiroz-Perozo, Alejandro Vivas, Lenin González-Paz, Ysaías. J. Alvarado, Patricia Rodriguez-Lugo, Arlene Cardozo-Urdaneta, Joan Vera-Villalobos, Felix Martinez-Rios, Jhoan Toro-Mendoza, Yovani Marrero-Ponce, Marcos A. Loroño-González and José L. Paz; Formal analysis, Yasmir Quiroz-Perozo, Alejandro Vivas, Lenin González-Paz, Ysaías. J. Alvarado, Patricia Rodriguez-Lugo, Arlene Cardozo-Urdaneta, Joan Vera-Villalobos, Felix Martinez-Rios, Jhoan Toro-Mendoza, Yovani Marrero-Ponce, Marcos A. Loroño-González and José L. Paz; Investigation, Yasmir Quiroz-Perozo, Marylu Mora, Alejandro Vivas, Lenin González-Paz, Ysaías. J. Alvarado, Patricia Rodriguez-Lugo, Arlene Cardozo-Urdaneta, Yanauri Bravo and José L. Paz; Methodology, Yasmir Quiroz-Perozo, Alejandro Vivas, Lenin González-Paz, Ysaías. J. Alvarado, Yanauri Bravo, Joan Vera-Villalobos, Felix Martinez-Rios, Jhoan Toro-Mendoza, Yovani Marrero-Ponce and José L. Paz; Writing – original draft, Yasmir Quiroz-Perozo and José L. Paz; Writing – review & editing, Yasmir Quiroz-Perozo, Marylu Mora, Lenin González-Paz, Ysaías. J. Alvarado, Jhoan Toro-Mendoza and Marcos A. Loroño-González.

Funding

This work received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Molecular structures were visualized using The Molegro Molecular Viewer (MMV) and Discovery Studio Visualizer BIOVIA packages. CB-Dock (

http://clab.labshare.cn/cb-dock/), a protein-ligand docking tool. GROMACS with the MyPresto Portal graphical interface (

https://www.mypresto5.jp/en/), employing the Amber99SB-ILDN force fields and the TIP3P water model. The magnitude of local frustration obtained for each docked structure was calculated using the Frustratometer Server (

http://frustratometer.qb.fcen.uba.ar/). The SPECTRUS (Subdivision based on Spectra of Rigid Units) tool (

http://spectrus.sissa.it/#home) was used to perform a decomposition into quasi-rigid regions or domains (Q) of each free and bound peptide. The SWOTein (Strengths and Weaknesses of Proteins) tool (

http://babylone.3bio.ulb.ac.be/SWOTein/index.php) was used, which is an algorithm based on the "statistical potentials". R statistics v4.4.0 was used to perform a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Computational model that allows studying the structural dynamics of proteins is based on the Protein Structure Network (PSN) method (

http://webpsn.hpc.unimo.it/wpsn3.php). The MOLE 2.5 program (

https://mole.upol.cz/) was employed, a widely used algorithm for the rapid and fully automated location and characterization of channels, tunnels and pores in simple and complex biomacromolecular structures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ku E, Lee BJ, Wei J, Weir MR. Hypertension in CKD: Core Curriculum 2019. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019; 74(1):120-131; https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.12.044.

- Hamrahian SM. Management of Hypertension in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017. May; 19(5):43; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-017-0739-9.

- Johnson RJ, Lanaspa MA, Gabriela Sánchez-Lozada L, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. The discovery of hypertension: evolving views on the role of the kidneys and current hot topics. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015; Feb 1; 308(3):F167-78; https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00503.2014.

- De Bhailis ÁM, Kalra PA. Hypertension and the kidneys. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2022; May 2; 83(5):1-11; https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2021.0440.

- Loperena R, Harrison DG. Oxidative Stress and Hypertensive Diseases. Med Clin North Am. 2017; Jan; 101(1):169-193; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2016.08.004.

- Bansal S. Revisiting resistant hypertension in kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2024; ep 1;33(5):465-473; https://doi.org/10.1097/MNH.0000000000001002.

- Georgianos PI, Agarwal R. Hypertension in chronic kidney disease-treatment standard. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2023; Nov 30; 38(12):2694-2703; https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfad118.

- Yu H, Lin L, Zhang Z, Zhang H, & Hu H. Targeting NF-κB pathway for the therapy of diseases: mechanism and clinical study. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2020; 5, 209; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-00312-6.

- Ting Liu, Lingyun Zhang, Donghyun Joo and Shao-Cong Sun. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2017; 2, 17023; https://doi.org/10.1038/sigtrans.2017.23.

- Song Ning, Thaiss Friedrich, Guo Linlin. NFκB and Kidney Injury. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019; Volume 10. Article 815; https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00815.

- Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Ferrebuz A, Vanegas V, Quiroz Y, Mezzano S, Vaziri ND. Early and sustained inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB prevents hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005; Oct; 315(1):51-7; https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.105.088062.

- Begum Dariya, Santosh Kumar Behera, Gowru Srivani, Batoul Farran, Afroz Alam & Ganji Purnachandra Nagaraju. Computational analysis of nuclear factor-κB and resveratrol in colorectal cancer, Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 2021; 39:8, 2914-2922; https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2020.1757511.

- Zhang H, Sun SC. NF-κB in inflammation and renal diseases. Cell Biosci. 2015; 5, 63; https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-015-0056-4.

- Norbert Henke, Ruth Schmidt-Ullrich, Ralf Dechend, Joon-Keun Park, Fatimunnisa Qadri, Maren Wellner, Michael Obst, Volkmar Gross, Rainer Dietz, Friedrich C Luft, Claus Scheidereit and Dominik N. Muller. Vascular Endothelial Cell–Specific NF-κB Suppression Attenuates Hypertension-Induced Renal Damage. Circulation Research. 2007; Volume 101, Number 3; https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.150474.

- Mamatha Serasanambati, Shanmuga Reddy Chilakapati. Function of Nuclear Factor kappa B (NF-κB) in human diseases-A Review. South Indian Journal Of Biological Sciences 2016; 2(4):368; https://doi.org/10.22205/sijbs/2016/v2/i4/103443.

- Albert S. Baldwin, Jr. The transcription factor NF-B and human disease. J Clin Invest. 2001; Jan;107(1):3-6. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI11891.

- Purawarga Matada, GS, Dhiwar, PS, Abbas, N, Singh, E, Ghara, A, Das, A, & Bhargava, SV. Molecular docking and molecular dynamic studies: screening of phytochemicals against EGFR, HER2, estrogen and NF-B receptors for their potential use in breast cancer. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 2021; Aug;40(13):6183-6192; https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2021.1877823.

- Anil Kumar, Utpal Bora. In silico inhibition studies of NF-B p50 subunit by curcumin and its natural derivatives. Med Chem Res. 2012; 21, 3281–3287; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00044-011-9873-0.

- Cheemanapalli S, Chinthakunta N, Shaikh NM, Shivaranjani V, Pamuru RR, & Chitta SK. Comparative binding studies of curcumin and tangeretin on up-stream elements of NF-B cascade: a combined molecular docking approach. Network Modeling Analysis in Health Informatics and Bioinformatics. 2019; 8, 15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13721-019-0196-2.

- Pattnaik S, Murmu S, Prasad Rath B, Singh MK, Kumar S, & Mohanty C. In silico screening of phytoconstituents as potential anti-inflammatory agents targeting NF-κB p65: an approach to promote burn wound healing. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 2024; Jan 29:1-29; https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2024.2306199.

- Babajan Banaganapalli, Chaitanya Mulakayala, Gowsia D, Naveen Mulakayala, Madhusudana Pulaganti, Noor Ahmad Shaik, Anuradha CM, Raja Mohan Rao, Jumana Yousuf Al-Aama, Suresh Kumar Chitta. Synthesis and biological activity of new resveratrol derivative and molecular docking: dynamics studies on NFκB. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2013; № 7, p. 1639-1657; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-013-0448-z.

- Dariya B, Behera SK, Srivani G, Farran B, Alam A, Nagaraju GP. Computational analysis of nuclear factor-κB and resveratrol in colorectal cancer. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 2020; Mar;43(1):55-85 https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2020.1757511.

- Bailly C, & Vergoten G. Japonicone A and related dimeric sesquiterpene lactones: Molecular targets and mechanisms of anticancer activity. Inflammation Research. 2022; 18, 164; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-021-01538-y.

- Smith BP, Babos M. Sildenafil. [Updated 2023 Feb 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558978/.

- Ana Karolina Santana Nunes, Catarina Rapôso, Sura Wanessa Santos Rocha, Karla Patrícia de Sousa Barbosa, Rayana Leal de Almeida Luna, Maria Alice da Cruz-Höfling, Christina Alves Peixoto. Involvement of AMPK, IKβα-NFκB and eNOS in the sildenafil anti-inflammatory mechanism in a demyelination model. Brain Research. 2015; Nov 19;1627:119-33; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2015.09.008.

- Luft Friedrich C. Mechanisms and Cardiovascular Damage in Hypertension. Hypertension. 2001; Volume 37, Number 2; https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.37.2.594.

- Ribaudo G, Pagano MA, Bova S, Zagotto G. New Therapeutic Applications of Phosphodiesterase 5 Inhibitors (PDE5-Is). Curr Med Chem. 2016; Jun 17;11(12):1726-1739; https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867323666160428110059.

- Pușcașu C, Zanfirescu A, Negreș S, Șeremet OC. Exploring the Multifaceted Potential of Sildenafil in Medicine. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023; Dec 17;59(12):2190; https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59122190.

- Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Ferrebuz A, Vanegas V, Quiroz Y, Espinoza F, Pons H, Vaziri ND. Early treatment with cGMP phosphodiesterase inhibitor ameliorates progression of renal damage. Kidney Int. 2005; Nov;68(5):2131-42; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00669.x.

- Yaguas K, Bautista R, Quiroz Y, Ferrebuz A, Pons H, Franco M, Vaziri ND, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Chronic sildenafil treatment corrects endothelial dysfunction and improves hypertension. Am J Nephrol. 2010; 31(4):283-91; https://doi.org/10.1159/000279307.

- Quiroz Y, Bravo J, Herrera-Acosta J, Johnson RJ, Rodríguez-Iturbe B. Apoptosis and NFkappaB activation are simultaneously induced in renal tubulointerstitium in experimental hypertension. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003; October, Pages S27-S32; https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.64.s86.6.x.

- Michelle Marian Turco and Marcelo Carlos Sousa. The Structure and Specificity of the Type III Secretion System Effector NleC Suggest a DNA Mimicry Mechanism of Substrate Recognition. Biochemistry 2014; Aug 12;53(31):5131-9; https://doi.org/10.1021/bi500593e.

- Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, Gindulyte A, He J, He S, & Bolton EE. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023; Jan 6;51(D1):D1373-D1380; https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac956.

- Bitencourt-Ferreira G, & de Azevedo WF. Molegro virtual docker for docking. Docking screens for drug Discovery. 2019;2053:149-167; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9752-7_10.

- Baroroh U, Biotek M, Muscifa ZS, Destiarani W, Rohmatullah FG, & Yusuf M. Molecular interaction analysis and visualization of protein-ligand docking using Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer. IJCB. 2023; Vol 2, No 1; https://doi.org/10.24198/ijcb.v2i1.46322.

- Liu Y, Grimm M, Dai WT, Hou MC, Xiao ZX, Cao Y. CB-Dock: a web server for cavity detection-guided protein-ligand blind docking. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020; Jan;41(1):138-144; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-019-0228-6.

- Cao Y, Li L. Improved protein-ligand binding affinity prediction by using a curvature-dependent surface-area model. Bioinformatics. 2014; Jun 15;30(12):1674-80; https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu104.

- Genheden S, & Ryde U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery. 2015; May;10(5):449-61; https://doi.org/10.1517/17460441.2015.1032936.

- Wang Z, Pan H, Sun H, Kang Y, Liu H, Cao D, & Hou T. fastDRH: a webserver to predict and analyze protein–ligand complexes based on molecular docking and MM/PB (GB) SA computation. Brief. Bioinform. 2022; Sep 20;23(5):bbac201; https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbac201.

- González-Paz L, Lossada C, Hurtado-León ML, Vera-Villalobos J, Paz JL, Marrero-Ponce Y, & Alvarado YJ. Biophysical Analysis of Potential Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Cell Recognition and Their Effect on Viral Dynamics in Different Cell Types: A Computational Prediction from In Vitro Experimental Data. ACS Omega. 2024; Feb 14;9(8):8923-8939; https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c06968.

- Horowitz BZ. Silibinin: a toxicologist's herbal medicine? Clin Toxicol. 2022; 60(11), 1194–1197; https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2022.2128815.

- González-Paz L, Hurtado-León ML, Lossada C, Fernández-Materán FV, Vera-Villalobos J, Loroño M, Paz JL, Jeffreys L, Alvarado YJ. “Structural deformability in proteins of potential interest associated with COVID-19 by binding of homologues present in ivermectin: Comparative study based in elastic network models”, Journal of Molecular Liquids. 2021; Volume 340,117284; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117284.

- Kumari R, Kumar V, Dhankhar P, Dalal V. Promising antivirals for PLpro of SARS-CoV-2 using virtual screening, molecular docking, dynamics, and MMPBSA. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 2022; 41(10), 4650–4666; https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2022.2071340.

- González-Paz LA, Lossada CA, Fernández-Materán FV, Paz JL, Vera-Villalobos J, Alvarado YJ. Can Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs Affect the Interaction Between Receptor Binding Domain of SARS-COV-2 Spike and the Human ACE2 Receptor? A Computational Biophysical Study. Front. Phys. 2020; volume 8; article 587606; https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2020.587606.

- López-Blanco JR, Chacón P. “New generation of elastic network models”. Current Opinion in Structural Biology.2016; Volume 37, April 2016, Pages 46-53; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2015.11.013.

- Parra RG, Schafer NP, Radusky LG, Tsai M, Guzovsky AB, Wolynes PG, Ferreiro DU. “Protein Frustratometer 2: a tool to localize energetic frustration in protein molecules, now with electrostatics”, Nucleic Acids Research. 2016; Volume 44, Issue W1, 8 July; https://doi.org/10.1093%2Fnar%2Fgkw304.

- Chen M, Chen X, Schafer NP, Clementi C, Komives EA, Ferreiro DU, & Wolynes PG. Surveying biomolecular frustration at atomic resolution. Nature Communications. 2020; 11, Article number: 5944; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19560-9.

- Delgado A, Vera-Villalobos J, Paz JL, Lossada C, Hurtado-León ML, Marrero-Ponce Y, & González-Paz L Macromolecular crowding impact on anti-CRISPR AcrIIC3/NmeCas9 complex: Insights from scaled particle theory, molecular dynamics, and elastic networks models. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023; Volume 244, 31 July 2023, 125113; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125113.

- Hou Q, Pucci F, Ancien F, Kwasigroch JM, Bourgeas R, Rooman M. “SWOTein: a structure-based approach to predict stability Strengths and Weaknesses of prOTEINs”, Bioinformatics. 2021; Jul 15;37(14):1963–1971; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab034.

- Joaquim Llisterri. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. R Core Team. https://www.r-project.org/.

- Angelo Felline, Michele Seeber, Francesca Fanelli. PSNtools for standalone and web-based structure network analyses of conformational ensembles. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 2022; Volume 20, 640 – 649; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2021.12.044.

- Angelo Felline, Michele Seeber, Francesca Fanelli, webPSN v2.0: a webserver to infer fingerprints of structural communication in biomacromolecules. Nucleic Acids Research. 2020; Volume 48, Issue W1, 02 July, Pages W94–W103; https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa397.

- Chalikian TV, Macgregor Jr. RB. On empirical decomposition of volumetric data. Biophys. Chem. 2019; Volume 246, March 2019, Pages 8-15; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpc.2018.12.005.

- Barletta GP, Fernandez-Alberti, S. Protein fluctuations and cavity changes relationship. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018; December 20,Vol 14/Issue 2 https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00744.

- Jiang Y, Kirmizialtin S, Sanchez IC. Dynamic void distribution in myoglobin and five mutants. SCIENTIFIC REPORTS. 2014; 4, 4011; https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04011.

- Ysaias José Alvarado, Yosmari Olivarez, Carla Lossada, Joan Vera-Villalobos, José Luis Paz, Eddy Vera, Marcos Loroño, Alejandro Vivas, Fernando Javier Torres, Laura N Jeffreys, María Laura Hurtado-León, Lenin González-Paz. Interaction of the new inhibitor paxlovid (PF-07321332) and ivermectin with the monomer of the main protease SARS-CoV-2: A volumetric study based on molecular dynamics, elastic networks, classical thermodynamics and SPT. Computational Biology and Chemistry. 2022; Volume 99, August, 107692 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2022.107692.

- Nava M, Quiroz Y, Vaziri N, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Melatonin reduces renal interstitial inflammation and improves hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003; March 2003.

- 58. Pages F447-F454; https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00264.2002. [CrossRef]

- Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B, Lindahl E. “GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers”, SoftwareX. 2015;volume 1,pages19-25; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001.

- Kasahara K, Terazawa H, Itaya H, Goto S, Nakamura H, Takahashi T, Higo J. myPresto/omegagene 2020: a molecular dynamics simulation engine for virtual-system coupled sampling. BPPB. 2020; Volume 17 Pages 140-146; https://doi.org/10.2142/biophysico.BSJ-2020013.

- Ponzoni L, Polles G, Carnevale V, Micheletti C. “SPECTRUS: A Dimensionality Reduction Approach for Identifying Dynamical Domains in Protein Complexes from Limited Structural Datasets”, Structure 2015; Volume 23, Issue 8, 1516 – 1525; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2015.05.022.

- Lukáš Pravda, David Sehnal, Dominik Toušek, Veronika Navrátilová, Václav Bazgier, Karel Berka, Radka Svobodová Vařeková, Jaroslav Koča, Michal Otyepka, MOLEonline: a web-based tool for analyzing channels, tunnels and pores. Nucleic Acids Research. 2018; Volume 46, Issue W1, 2 July 2018, Pages W368–W373; https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky309.

- Chennubhotla C. and Bahar I. Signal Propagation in Proteins and Relation to Equilibrium Fluctuations. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2007; 3(10): e223. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030223.

- Mengjun Xue, Takuro Wakamoto, Camilla Kejlberg, Yuichi Yoshimura, Tania Aaquist Nielsen, Michael Wulff Risor, Kristian Wejse Sanggaard, Ryo Kitahara and Frans AA Mulder. How internal cavities destabilize a protein. PNAS. 2019; September 30, 2019, 116 (42) 21031-21036; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1911181116.

Figure 1.

a) Crystal structure of NF-κB (PDB ID: 4Q3J) and b) 2D representation of sildenafil (CID_135398744).

Figure 1.

a) Crystal structure of NF-κB (PDB ID: 4Q3J) and b) 2D representation of sildenafil (CID_135398744).

Figure 2.

a) Minimum energy structure NF-κB +Sildenafil of molecular docking (0ns) and b) after 100 ns of molecular dynamics simulation, including the distribution of hydrogen bond (HB, green), hydrophobic (HP, pink), electrostatic (ES, orange) and van der Waals (vdW, light blue) protein-ligand interactions.

Figure 2.

a) Minimum energy structure NF-κB +Sildenafil of molecular docking (0ns) and b) after 100 ns of molecular dynamics simulation, including the distribution of hydrogen bond (HB, green), hydrophobic (HP, pink), electrostatic (ES, orange) and van der Waals (vdW, light blue) protein-ligand interactions.

Figure 3.

(a) Root mean square deviation (RMSD), (b) Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) and (c) Radius of gyration (Rg) of free NF-κB (red) and NF-κB + sildenafil complex (blue) (d) Depletion of hydrogen bonding (HB, green), hydrophobic (HP, pink), electrostatic (ES, orange), and Van der Waals (vdW, light blue) interactions of minimum energy NF-κB + sildenafil complexes at 0 ns and 100 ns of MD simulations.

Figure 3.

(a) Root mean square deviation (RMSD), (b) Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) and (c) Radius of gyration (Rg) of free NF-κB (red) and NF-κB + sildenafil complex (blue) (d) Depletion of hydrogen bonding (HB, green), hydrophobic (HP, pink), electrostatic (ES, orange), and Van der Waals (vdW, light blue) interactions of minimum energy NF-κB + sildenafil complexes at 0 ns and 100 ns of MD simulations.

Figure 4.

The figure plots the energy values (kcal/mol) against amino acid residues for the distance (a), solvent accessibility (b) and torsion angle (c) statistical potentials obtained from SWOTein. The blue line represents the NF-κB wild-type protein while the red line represents NF-κB + Sildenafil complex. This plot provides a visual comparison of the statistical distance potentials under these two conditions. Additionally, the distribution of data is shown demonstrating density versus Energy (kcal/mol) for distance (d), solvent accessibility (e) and torsion angle (f). In all figures, the blue line represents the NF-κB wild-type protein while the red line represents NF-κB + Sildenafil complex.

Figure 4.

The figure plots the energy values (kcal/mol) against amino acid residues for the distance (a), solvent accessibility (b) and torsion angle (c) statistical potentials obtained from SWOTein. The blue line represents the NF-κB wild-type protein while the red line represents NF-κB + Sildenafil complex. This plot provides a visual comparison of the statistical distance potentials under these two conditions. Additionally, the distribution of data is shown demonstrating density versus Energy (kcal/mol) for distance (d), solvent accessibility (e) and torsion angle (f). In all figures, the blue line represents the NF-κB wild-type protein while the red line represents NF-κB + Sildenafil complex.

Table 1.

Relative Binding Energies from Molecular Docking, MM/PBSA, Theoretical Inhibition Constants, and Potencies of NF-κB + Sildenafil and other reference compounds.

Table 1.

Relative Binding Energies from Molecular Docking, MM/PBSA, Theoretical Inhibition Constants, and Potencies of NF-κB + Sildenafil and other reference compounds.

| Complex |

Kcal/mol |

Molarity |

Kcal/mol |

|

| |

ΔG |

MMa

|

MMb

|

Ki

|

IC50

|

pIC50

|

Ref |

| Sildenafil |

- 7.8* |

-1.84* |

-25.63* |

1.92*c

|

0.137* |

5.4* |

This work |

| Resveratrol |

- 6.1 |

- |

- |

3.20b

|

0.015 |

4.2 |

21 |

| Resveratrol |

- 7.9 |

- |

- |

1.64c

|

0.149 |

5.5 |

21 |

| Resveratrol |

- 5.6 |

- |

- |

8.10b

|

0.006 |

3.8 |

12 |

| Curcumin sulphate |

- 8.9 |

- |

- |

2.80d

|

0.296 |

6.3 |

18 |

| Curcumin |

- 6.0 |

- |

- |

3.99b

|

0.012 |

4.1 |

19 |

| Tangeretin |

- 3.5 |

- |

- |

2.90a

|

0.00017 |

2.2 |

19 |

| Silibinin |

- 8.9 |

1.50 |

- |

2.99d

|

0.291 |

6.2 |

20 |

Table 2.

Comparison of the structural deformability parameters of free NF-κB and in complex with sildenafil, employing coarse-grained ENM and statistical energy function methods.

Table 2.

Comparison of the structural deformability parameters of free NF-κB and in complex with sildenafil, employing coarse-grained ENM and statistical energy function methods.

| |

Protein Structure Networkb

|

Average Highly Frustrated Contactsc

|

ΔG of Statistical Potentials (kcal/mol)d

|

| |

Q-rda

|

#Paths |

Avg.p.f. |

Protein Structure |

Interaction Residues |

Distance |

Accesibility |

Torsion |

| Free |

2 |

81654 |

25.69 |

1.84 |

1.83 |

-81,87 |

-4.2 |

136.36 |

| NF-B + sil |

9 |

101221 |

24.15 |

1.98 |

1.33 |

-74,44 |

16.5 |

167.88 |

Table 3.

Biopsy Analysis Data from Experimental Model 1) Arterial Hypertension in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats (SHR) and Experimental Model 2) Chronic Kidney Failure (5/6 Nephrectomy).

Table 3.

Biopsy Analysis Data from Experimental Model 1) Arterial Hypertension in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats (SHR) and Experimental Model 2) Chronic Kidney Failure (5/6 Nephrectomy).

| |

Experimental Model 1 |

Experimental Model 2 |

| |

Sham |

5/6Nx |

5/6Nx+Sil |

WKY |

SHR |

SHR+Sil |

| SBP mm Hg |

129 ± 3.5 |

162 ± 12.0 |

133 ± 9.1 |

129 ± 4.6 |

176 ± 2.8 |

149 ± 3.8 |

| GI |

4.5 ± 1.0 |

31 ± 1.0 |

12 ± 0.5 |

5.0 ± 0.8 |

7.3 ± 1.1 |

5.7 ± 0.9 |

| TDscore |

0.9 ± 2.0 |

3.0 ± 0.5 |

1.2 ± 0.3 |

1.1 ± 0.5 |

2.1 ± 0.5 |

1.8 ± 0.5 |

| CD5+ (cell/mm2) |

10 ± 3.0 |

37 ± 2.7 |

13 ± 0.7 |

23 ± 9.0 |

42 ± 5.0 |

40 ± 6.1 |

| ED1+ (cell/mm2) |

12 ± 5.1 |

51 ± 4.3 |

22 ± 2.6 |

16 ± 6.0 |

44 ± 6.1 |

30 ± 3.9 |

| NFB (cell/mm2) |

11 ± 2.3 |

33 ± 10 |

20 ± 8.0 |

12 ± 3.1 |

30 ± 5.5 |

22 ± 7.0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).