1. Introduction

Potato (

Solanum tubulosum L.) is the most consumed non-cereal food and vegetable crop and fourth largest food crop in the world after maize, rice, and wheat [

1]. It is also an excellent source of energy, protein, vitamins, and minerals. Potato species with 24, 36, 48, 60, 72 polyploidy exist in nature [

2]. Among them, most of the commercially cultivated potato species are autotetraploid. Autotetraploid potato has a high frequency of chromosome recombination and a low frequency of recessive gene expression, which can be fixed by asexual propagation. However, its genome is highly heterozygous, which hinders genetic analysis and improvement. Therefore, it is important to investigate and identify molecular markers and key genes for the genetic development of autotetraploid potato. High-throughput bioinformatics approaches can be used to map genes of interest more quickly and easily than traditional molecular biology techniques [

3,

4]. In 2011, the genome of the heterozygous diploid potato RH (

S. tuberosum group) was sequenced and assembled by the International Potato Sequencing Team (PGSC) and it provided a reference database for discovering useful genetic information from massive biological data [

1].

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) is a method to specify modules based on the expression data of gene chip or RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq). It uses system biology to understand co-expression networks and explore connections between genes and target traits [

4]. Moreover, WGCNA provides clues for screening the signaling pathways and regulatory factors involved in the target genes [

5]. At present, a large number of literatures have used WGCNA to study potato disease resistance and defense mechanisms. Yan et al. used different hormones to treat late blight resistant potato genotype SD20 and used WGCNA to analyze transcriptome data to obtain nine defense genes, which provided reliable targets for functional verification [

6]. Jing et al. used WGCNA analysis to find 13 TF-hub genes related to proline metabolism and salt stress resistance in potato [

7]. Guo et al. analyzed gene expression in potato tissues under nitrogen-sufficient and nitrogen-deficiency conditions, and generated 23 modules from 116 differentially expressed hub genes involved in photosynthesis, nitrogen metabolism, and secondary metabolites by WGCNA [

8]. Cao et al. identified number of potato hub genes by WGCNA, including genes that regulate plant immune responses such as

flagellin-sensitive 2 and

chitinases [

9]. Additionally, studies have also used WGCNA to explore the molecular mechanisms of plant growth and development in other species. Liu et al., constructed a co-expression network of genes in rutabaga hypocotyl tuber, and WGCNA identified 59 co-expressed gene modules. Among them, two genes,

Bra-FLOR1 and

Bra-CYP735A2, related to tuber growth were grouped in the same module. This module also included genes involved in carbohydrate transport and metabolism, cell wall growth, auxin regulation, and secondary metabolism [

10]. To date, only few studies have investigated the growth and development of potato by WGCNA.

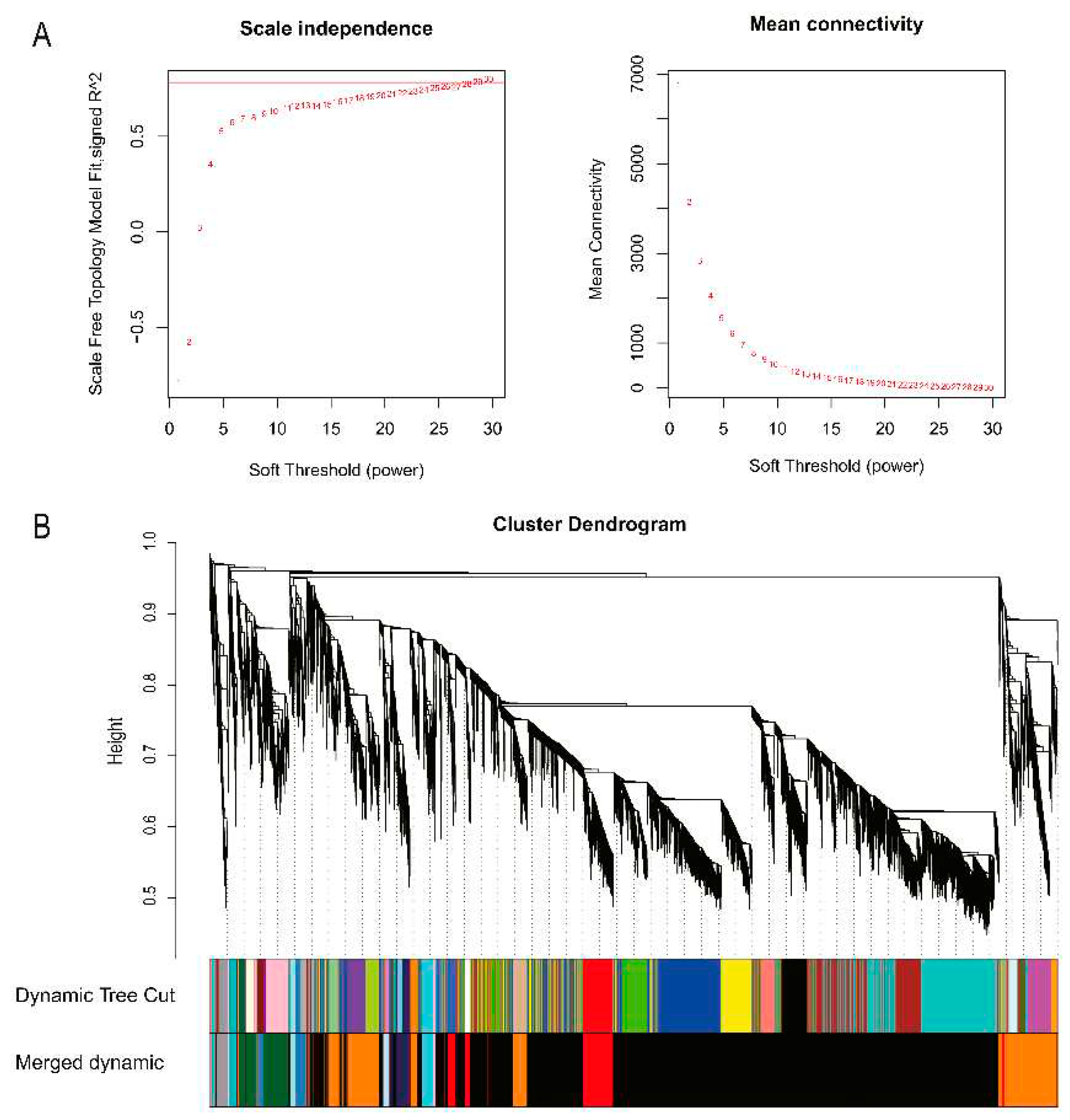

In this study, we aimed to explore the co-expression network of genes involved in potato growth and development. Firstly, transcriptome sequencing was performed on roots, stems and leaves of the autotetraploid potato JC14 at three developmental stages, and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were analyzed. Secondly, the Gene Co-expression Network was constructed by WGCNA, and the target gene modules related to growth and development traits were screened. Thirdly, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene ontology (GO) analysis were performed to reveal the major metabolic pathways involved in the target gene modules and the potential functions of these genes. The key genes in the module were then identified according to the connectivity of the genes in the corresponding network. Finally, real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was used to verify the expression pattern of these key genes during growth and development in Solanum tubulosum L. This study was expected to construct a comprehensive and dynamic gene co-expression network of potato growth and development, reveal the spatio-temporal expression of genes and the regulation mechanism of traits at different developmental stages, lay a theoretical foundation for exploring the molecular mechanism of potato growth and development regulation, and provide new genetic resources for molecular breeding of autotetraploid potato.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant material culture and sampling

Potato genotype JC14 was cultivated in Nankou Pilot Base, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing (longitude 116.408490; Latitude 40.154860) in a greenhouse with natural light from 2022 to 2023. Cultivation and field management followed normal production protocols. Potato roots, stems, and leaf tissues and organs were sampled at the seedling, tuber formation, and tuber expansion stages in three biological replicates. After collection, the samples were washed with pure water, quickly froze in liquid nitrogen, and kept at -80°C for subsequent total RNA extraction.

2.2. RNA extraction, Illumina sequencing and data analysis

Total RNA from 27 samples was extracted using TIANGEN's plant RNA extraction kit by magnetic bead method (item number: DP762-T1) (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol.Total RNA purity was detected using a Nano Photometer® spectrophotometer (IMPLEN, CA, USA) and total RNA samples were tested for concentration and integrity using Agilent 2100 RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) in the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). When RNA integrity RIN >= 7, the requirements of cDNA library construction and subsequent sequencing was fulfilled. After the total RNA samples were qualified, 1-3μg of which from each sample was used as starting material to construct the transcriptome sequencing library. According to the VAHTS Universal V6 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit for Illumina (No. NR604-01/02) (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), different index tags were selected to build the sequencing library. For qualified Total RNA samples, the eukaryotic mRNA was enriched by magnetic beads with Oligo (dT), and then the mRNA was broken into short fragments by adding fragmentation buffer. One-strand cDNA was synthesized with random hexamers, followed by adding buffer, dNTPs, RNase H and DNA polymerase I to synthesize double-stranded cDNA. The double-stranded cDNA was then purified using AMPure P beads purification or QiaQuick PCR kit. The purified double-stranded cDNA was subjected to end repair, A-tail addition and sequencing adapter ligation, followed by fragment size selection, and finally PCR enrichment to obtain the final cDNA library. After the library was constructed, the Qubit 3.0 was used for preliminary quantification, and the library was diluted to 1 ng/μL, and finally Bio-RAD KIT iQ SYBR GRN was used for QPCR to accurately quantify the effective concentration of the library (library effective concentration > 10 nM) to ensure library quality. The NovaSeq 6000 S4 Reagent kit V1.5 was used for clustering and sequencing on the NovaSeq 6000 S4 platform, and the double-end sequencing program (PE) was run to obtain 150 bp double-end sequencing reads.

Sequencing quality was assessed using FastQC and Trimmomatic software [

11]. Raw reads were trimmed by eliminating adapters, poly-N, and low-quality reads to obtain clean data, which were then mapped to the potato reference genome using HISAT2 [

12]. The reference genome was downloaded from Spud DB Potato Genomics Resource (

http://spuddb.uga.edu/rh_potato_download.shtml). Transcription and expression level of genes were measured using FPKM (fragments per KB of transcript per million fragments mapped) in StringTie [

13] and differential expression was analyzed using the DESeq R package [

14]. In this study, a DEG was considered if the fold change was >2 and q-valuewas <0.05.

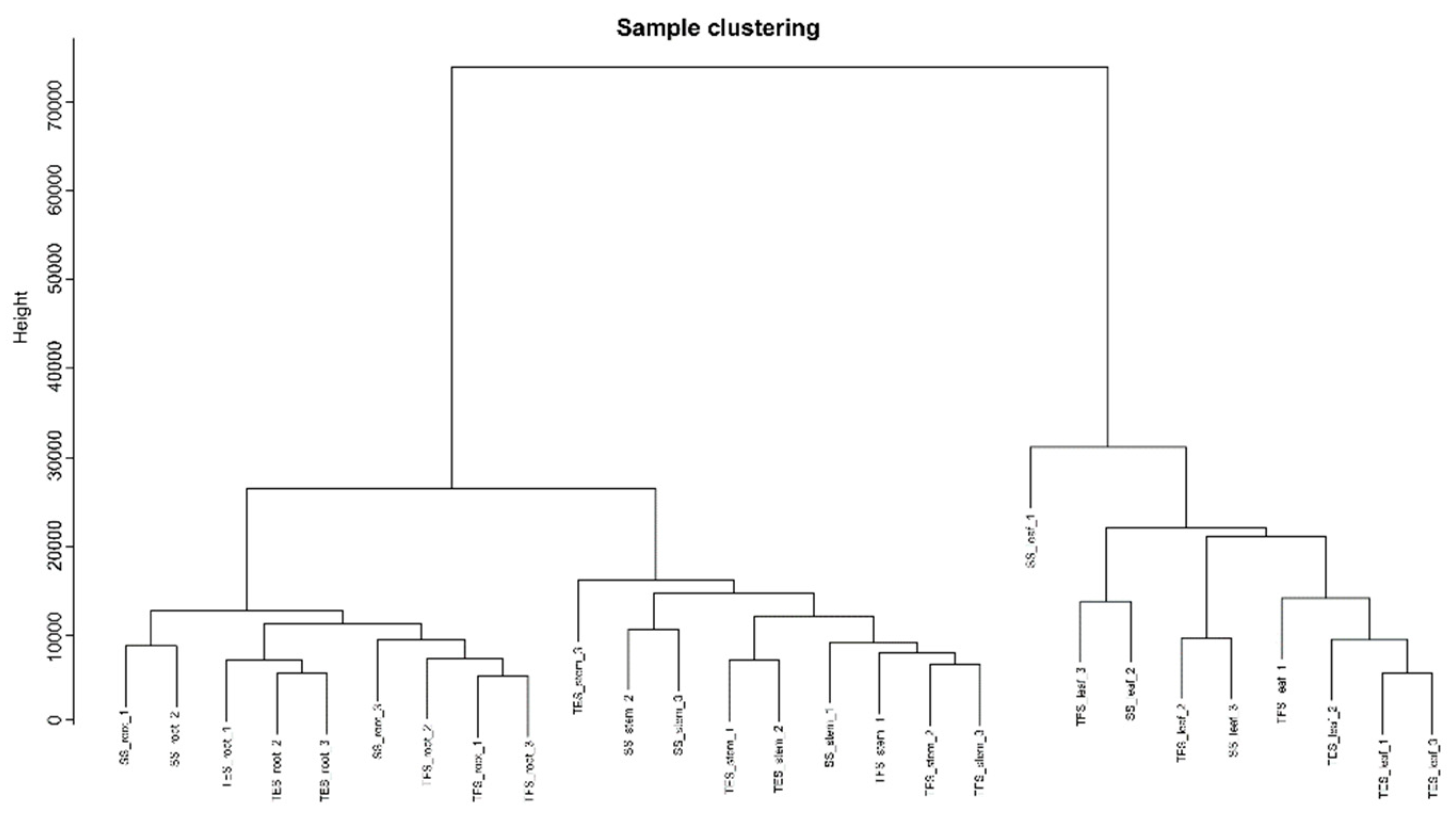

2.3. Construction of weighted co-expressed gene networks

By referring to the tutorial on the WGCNA official website, The WGCNA package of R software was used to construct the co-expressed gene network [

4]. Firstly, samples with low correlation or that could not be clustered on the dendrogram were removed and cluster analysis was performed. Secondly, in order to meet the premise of scale-free network distribution, the pick soft threshold function in the WGCNA package was used to calculate the soft threshold. When the fitting curve was close to 0.9 for the first time, the threshold parameter β was selected. Then, according to the value of β, the correlation based association between phenotype and gene modules was performed to create the adjacency matrix. The adjacency matrix was further transformed into topological overlap matrix (TOM) to construct the gene connectivity network. Finally, based on the eigengenes of each module, the gene modules are identified and clustered by the dynamic tree cut method, and the modules that are closer to each other are merged into new modules. In this study, the module similarity threshold was set to 0.25, the expression threshold was set to 2, and the minimum number of genes in a module was set to 30 to partition modules.

2.4. Selection and enrichment analysis of key modules

To further investigate the gene modules related to potato growth and development, the correlation coefficients between the module characteristic genes and different samples were calculated. The module with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.5 was selected as the target gene module. DEGs in the target module were annotated using Blast2Go [

15]. Blast2Go was used to retrieve gene ontology (GO) entries, including biological processes, molecular functions and cellular components. Pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs within the target module was performed using KEGG database [

16].

2.5. Screening and functional analysis of hub genes

All DEGs of the four target modules were selected and using the WGCNA R package to calculate the intra-module gene significance, edges, and nodes [

4] (

Table S5). The information was exported to Cytoscape 3.9.1 software for gene network analysis and mapping [

17]. DEGs with high connectivity in the target gene module were screened as candidate hub genes. Swiss-port databases [

18] was used for homology annotation.

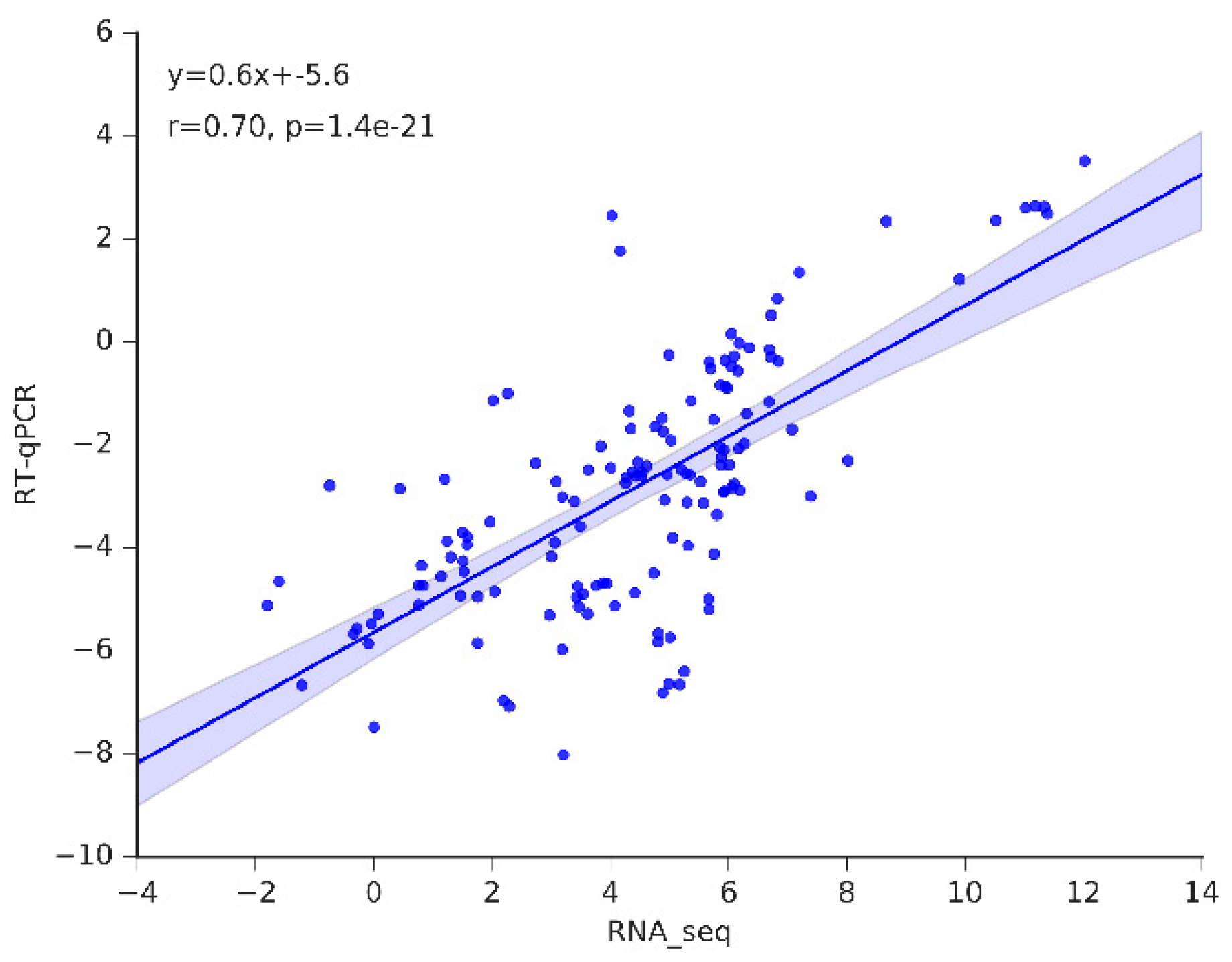

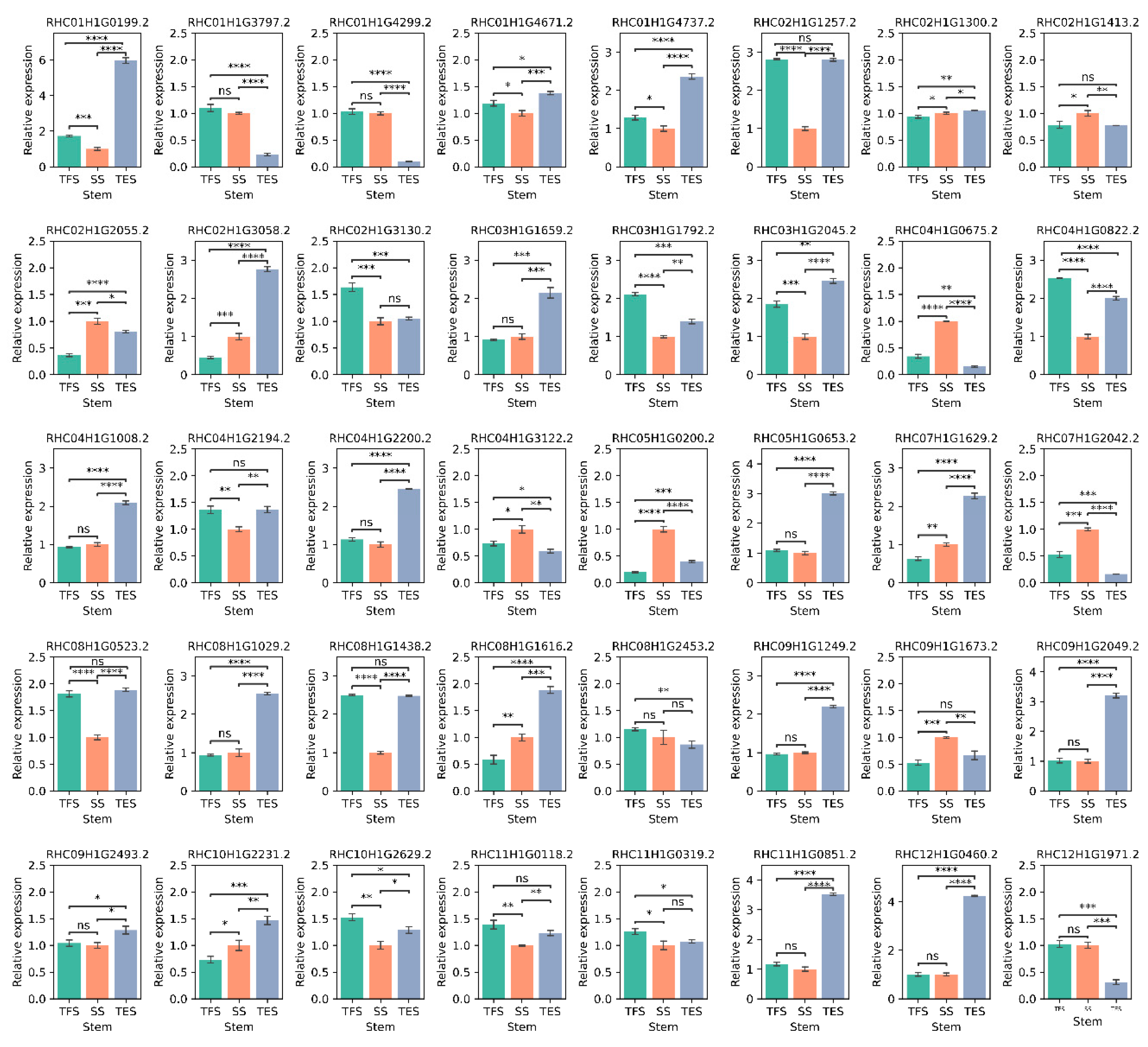

2.6. RT-qPCR was used to verify hub gene expression

In order to verify the reliability of RNA-seq data, 20 genes were used for RT-qPCR to determine the changes in their relative expression levels, and R package was used to calculate and plot the correlation between the relative expression levels and FPKM. And then, a total of 40 candidate hub genes were selected for RT-qPCR analysis to assess their expression levels. Primers for candidate hub genes were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 (

Table S8). Potato stems from the seedling, tuber formation and tuber expansion stages were selected as raw materials. Gene expression analysis of candidate hub genes was performed on the LightCycler480 system (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) with a total reaction volume of 10 µL for RT-qPCR, this included 12.5 µL 5 µL 2X SG Fast qPCR Master Mix (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), 0.2 µL primer (10 µM), 1.0 µL template (10×diluted cDNA liquid), and 3.6 µL ddH2O. Using actin as the reference gene and the 2−∆∆ CT methods, the expression levels of selected hub genes were calculated [

19]. Histograms were plotted by seaborn package in python. Three independent biological replicates were performed for each sample in this assay, significance and standard deviation was determined by independent t-test of statannot package (ns: p > 0.05; *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001; ****: p < 0.0001).

4. Discussion

Genetic analysis and improvement are obstructed by the high degree of genomic heterozygosity in cultivated cultivars of autotetraploid potatoes. Identifying key candidate genes related to growth and development can provide target gene resources for molecular breeding. Previous literatures have studied the mechanisms of potato cold resistance [

21], disease resistance [

22], and nitrogen utilization [

8] through transcriptome approach. The mechanisms involved in the growth and development of autotetraploid potato, however, are extremely complex, gene expression changes in multiple metabolic pathways occur at different developmental stages. In this study, WGCNA was used to construct a co-expression network of weighted genes related to potato growth and development traits based on transcriptome datasets from roots, stems and leaves of potatoes at different developmental stages. A total of 12 gene modules were identified, of which 4 were significantly associated with stem growth and development. Thirty candidate hub genes with high connectivity were selected from each of the four modules to make a network diagram (

Figure 5C,

Figure 6C,

Figure 7C and

Figure 8C), and the top 10 hub genes in each module with the highest connectivity were selected for subsequent analysis. These hub genes may play important roles in potato growth and development through carbohydrate metabolism, cell growth, defense response and other related metabolic pathways.

Carbohydrate is an important energy substance and plays a crucial role in plant growth and development. Xylan is the most abundant hemicellulose, and the accuracy and location of xylan acetylation are critical for xylan function and plant growth and development. RWA protein family plays an important role in regulating cell wall acetylation after xylan synthesis and are essential for the efficient binding of xylan to cellulose [

23]. Over-expression of

Dendrobium officinale RWA3 significantly increased the acetylation level of polysaccharides in seeds, leaves and stems [

24]. PG is involved in carbohydrate metabolism and is very important for cell wall metabolism and maintenance of plant tissue morphology. Literature suggests that PG is associated with quality processes such as fruit ripening, flavor, firmness [

25]. Moreover, PG has a negative regulatory role in promoting fruit softening.

PG is highly expressed in immature fruits and plays an important role in maintaining the firmness of fruits [

26]. In addition, the up-regulation of genes related to cellulose and pectin metabolism pathways, including

PG, will increase the tensile stress of Catalpa bungei, which is conducive to the formation of high-quality wood [

27]. In this study,

RWA3 and

PG were highly expressed at all three stages, indicating their important involvement in the whole growth and development stages of the potato stem.

Auxin and cytokinins (CKs) are essential hormones that regulate plant growth and development. O-glucosyltransferase is involved in the metabolic process of plant CKs and catalyzes the reversible inactivation of O-glucosylation. It is an important mechanism for the homeostasis of plant CKs in vivo. Both O-glucosyltransferases and UDP glucosyltransferases are subfamilies in the glycosyltransferase superfamily. Among them, zeatin O-glucosyltransferase belongs to the CK O-glucosyltransferase superfamily [

28]. Zeatin O-glucosyltransferase is a negative regulator of growth and development, and its up regulation may be the reason for the long life and slow growth of Dracaena [

29]. In this study, the expression of

O-glucosyl transferase was low in the stem at the tuber formation stage and high at the tuber expansion stage, which may contribute to the gradual slowing of potato growth as development progressed. However,

UDP-glycosyltransferases (RHC01H1G4299.2) showed a low expression level at all three developmental stages.

Pathogenesis-related proteins are specific proteins induced under pathological conditions and play an important role in plant disease resistance.

GLU is a pathogenesis related protein in the pathogenesis-related family. Its expression is highly induced several hours after soybean infection with Phakopsora pachyrhizi. Soybean PEPPA-7431740 may trigger immunity by interfering with the activity of -1, 3-β-glucosidase within glucan and inhibiting pathogen-associated molecular patterns [

30]. The pesticide GLY-15 has a good antiviral activity against tobacco Mosaic virus in plants. It induces a stress response in plants, in which the expression of 12 key genes including

glucan-1, 3-β-glucosidase is significantly up-regulated [

31]. Other studies have shown that glucan endo-1, 3-β-glucosidase is involved in plant response to soil alkaline stress [

32]. 1, 3-β-glucan is a polysaccharide widely distributed in the cell walls of several phylogenetically distant organisms, such as bacteria, fungi, plants and microalgae, and is involved in cell wall degradation [

33]. CRRSP55 is a disease-related protein. MgMO237 interacted with rice defense related protein 1, 3-betaglucan synthase component (OsGSC) and OsCRRSP55 to inhibit plant basal immunity during the late parasitic stage of nematode. Thus, it promotes parasitism in gramineae [

34]. In this study,

GLU and

CRRSP55 genes were expressed in stems at all three developmental stages (

Figure 5A), suggesting that these genes may play an ongoing role in potato defense against pests and diseases.

In addition,

MYB61 and

PCF3 were selected as transcription factors in the module. Sugarcane MYBs play an important role in stem development and various stress responses, among which

MYB61 positively responds to drought stress [

35]. Seedlings of barren-tolerant wild soybean are more adaptive to phosphorus stress than common wild soybean, which absorb more phosphorus by increasing root length, and

MYB61 is a key transcription factor for resistance to low phosphorus stress in barren-tolerant wild soybean [

36]. Rice

MYB61 may regulate the efficiency of crop nitrogen usage, which in turn affects rice growth and yield [

37].

TCP (teosinte branched1/ccincinnata/proliferating cell factor) is a set of specific transcription factors plays an important role in plant growth and development, and

PCF3 is a TCP family transcription factor [

38].

TCP transcription factors regulate leaf curvature, flower symmetry and the synthesis of secondary metabolites. Most

TCPs in Ginkgo biloba also respond to exogenous hormones such as ABA, SA and MeJA [

39]. In this study, the expression of

MYB61 was higher in stems at the seedling and tuber formation stages and decreased at the tuber expansion stage, suggesting that

MYB61 may play a role in response to drought and low phosphorus stress and nitrogen fixation in the early growth stage of potato. As growth and development progressed, the expression of

PCF3 in the stem gradually increased and was highest at the tuber expansion stage, suggesting that

PCF3 may promote potato stem growth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and Jiayin.W.; methodology, Z.L.; software, Z.L.; validation, Z.L. and Juan.W.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, Z.L.; resources, Z.L. and Jiayin.W; data curation, Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, Jiayin.W.; visualization, Z.L.; supervision, Jiayin.W.; project administration, Jiayin.W.; funding acquisition, Jiayin.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

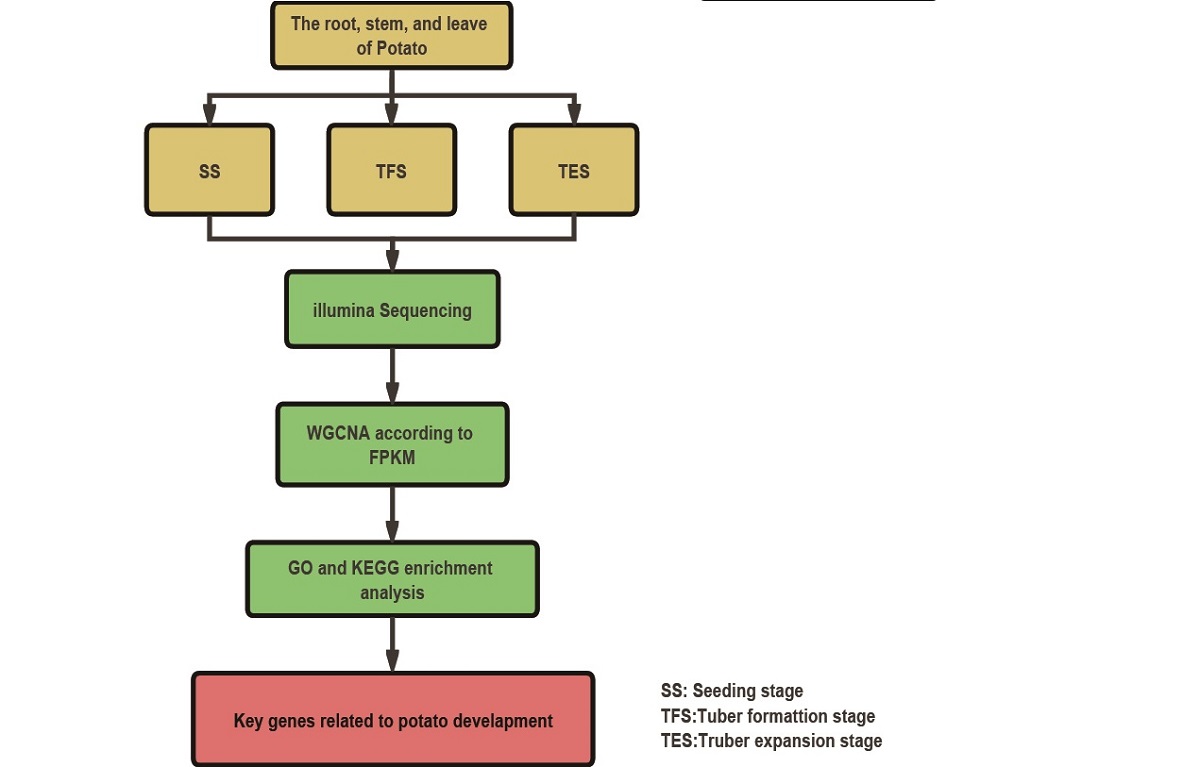

Figure 1.

Venn diagram of up and down regulated DEGs in different tissues of potato at different developmental stages. Different developmental stages: seedling stage, tuber formation stage, tuber expansion stage. (A) Venn diagram of DEGs in potato roots at different developmental stages. (B) Venn diagram of DEGs in potato stems at different developmental stages. (C) Venn diagram of DEGs in leaves at different developmental stages. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage; up: Up-regulation; down: Down-regulation.

Figure 1.

Venn diagram of up and down regulated DEGs in different tissues of potato at different developmental stages. Different developmental stages: seedling stage, tuber formation stage, tuber expansion stage. (A) Venn diagram of DEGs in potato roots at different developmental stages. (B) Venn diagram of DEGs in potato stems at different developmental stages. (C) Venn diagram of DEGs in leaves at different developmental stages. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage; up: Up-regulation; down: Down-regulation.

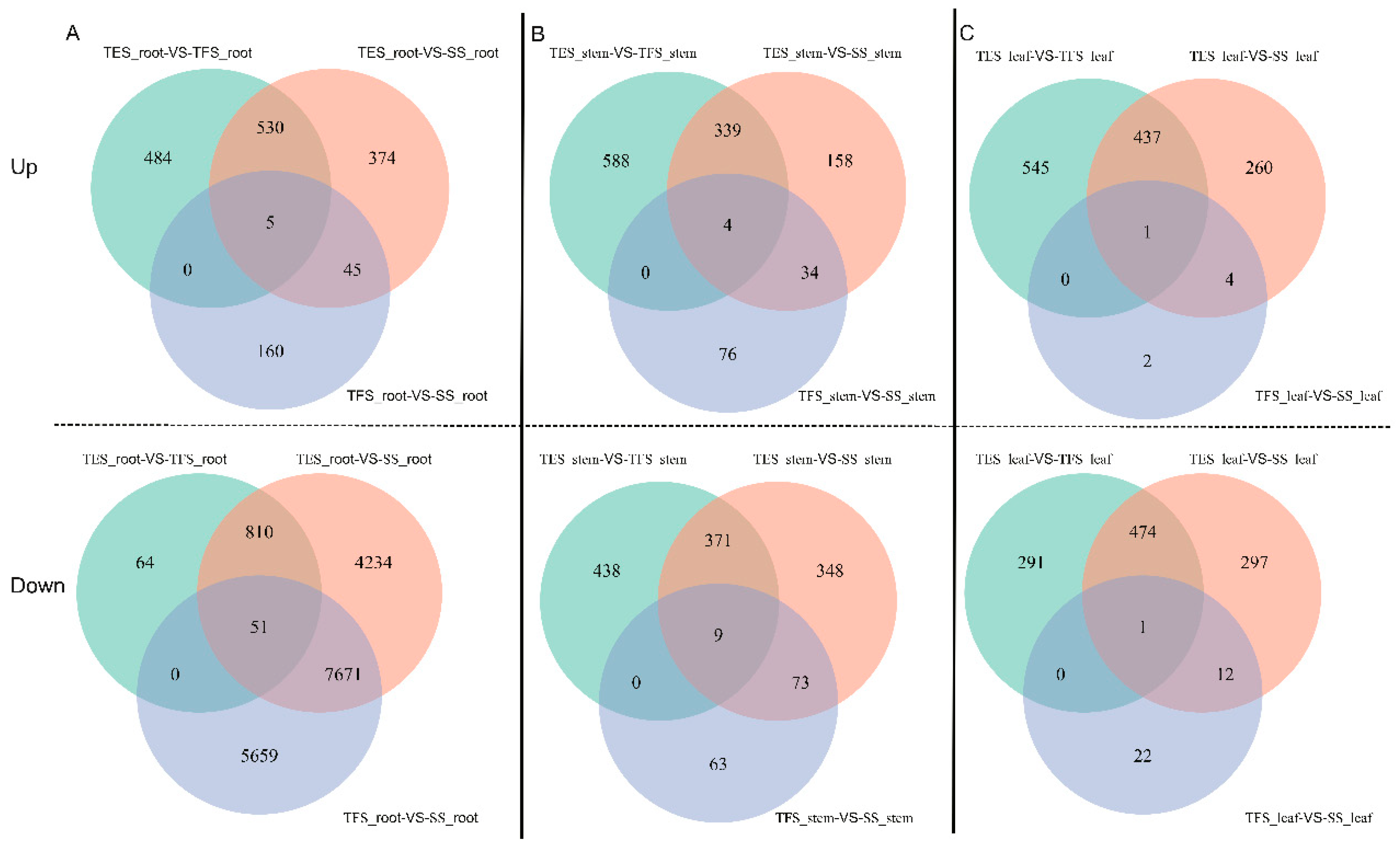

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic dendrogram of all 27 samples. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic dendrogram of all 27 samples. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 3.

Determination of soft thresholds for gene co-expression networks and detection of modules for gene cluster dendrograms. (A) Soft threshold determination. (B) Detection of modules by gene cluster dendrogram.

Figure 3.

Determination of soft thresholds for gene co-expression networks and detection of modules for gene cluster dendrograms. (A) Soft threshold determination. (B) Detection of modules by gene cluster dendrogram.

Figure 4.

Correlation analysis between modules and traits revealed by Pearson correlation coefficient. Leftmost co-expression modules are shown in different colors. Numbers in the figure indicate the correlation between the module and the trait, and numbers in parentheses are the correlation p-values. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 4.

Correlation analysis between modules and traits revealed by Pearson correlation coefficient. Leftmost co-expression modules are shown in different colors. Numbers in the figure indicate the correlation between the module and the trait, and numbers in parentheses are the correlation p-values. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 5.

Expression patterns of GO enrichment, KEGG enrichment, gene co-expression network, and hub genes in the gray60 module. (A) GO enrichment analysis. (B) KEGG enrichment analysis. (C) Gene co-expression network and hub genes. The figure shows top 30 hub genes with high connectivity, with the redder color representing higher connectivity. (D) Hub gene expression pattern in potato stems at seedling, tuber formation and tuber expansion stages. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 5.

Expression patterns of GO enrichment, KEGG enrichment, gene co-expression network, and hub genes in the gray60 module. (A) GO enrichment analysis. (B) KEGG enrichment analysis. (C) Gene co-expression network and hub genes. The figure shows top 30 hub genes with high connectivity, with the redder color representing higher connectivity. (D) Hub gene expression pattern in potato stems at seedling, tuber formation and tuber expansion stages. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 6.

Expression patterns of GO enrichment, KEGG enrichment, gene co-expression network, and hub genes in darkgreen module. (A) GO enrichment analysis. (B) KEGG enrichment analysis. (C) Gene co-expression network and hub genes. The figure shows top 30 hub genes with the highest connectivity, with the redder color representing higher connectivity. (D) Expression patterns of hub genes in potato stems at seedling stage, tuber formation stage and tuber expansion stage. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 6.

Expression patterns of GO enrichment, KEGG enrichment, gene co-expression network, and hub genes in darkgreen module. (A) GO enrichment analysis. (B) KEGG enrichment analysis. (C) Gene co-expression network and hub genes. The figure shows top 30 hub genes with the highest connectivity, with the redder color representing higher connectivity. (D) Expression patterns of hub genes in potato stems at seedling stage, tuber formation stage and tuber expansion stage. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 7.

GO enrichment, KEGG enrichment, gene co-expression network, and expression patterns of hub genes in steelblue module. (A) GO functional enrichment analysis. (B) KEGG functional enrichment analysis. (C) Gene co-expression network and hub genes. The figure shows top 30 hub genes with the highest connectivity, with the redder color representing higher connectivity. (D) Expression patterns of hub genes in potato stems at seedling stage, tuber formation stage and tuber expansion stage. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 7.

GO enrichment, KEGG enrichment, gene co-expression network, and expression patterns of hub genes in steelblue module. (A) GO functional enrichment analysis. (B) KEGG functional enrichment analysis. (C) Gene co-expression network and hub genes. The figure shows top 30 hub genes with the highest connectivity, with the redder color representing higher connectivity. (D) Expression patterns of hub genes in potato stems at seedling stage, tuber formation stage and tuber expansion stage. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 8.

Expression patterns of GO enrichment, KEGG enrichment, gene co-expression network, and hub genes in the paleturquoise module. (A) GO functional enrichment analysis. (B) KEGG functional enrichment analysis. (C) Gene co-expression network and hub genes.The figure shows top 30 hub genes with the highest connectivity, with a redder color representing higher connectivity. (D) Hub gene expression patterns in potato stems at seedling, tuber formation and tuber expansion stages. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 8.

Expression patterns of GO enrichment, KEGG enrichment, gene co-expression network, and hub genes in the paleturquoise module. (A) GO functional enrichment analysis. (B) KEGG functional enrichment analysis. (C) Gene co-expression network and hub genes.The figure shows top 30 hub genes with the highest connectivity, with a redder color representing higher connectivity. (D) Hub gene expression patterns in potato stems at seedling, tuber formation and tuber expansion stages. SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 9.

The correlation of expression levels of the selected genes as determined by RNA-seq and RT-qPCR are closely correlated.

Figure 9.

The correlation of expression levels of the selected genes as determined by RNA-seq and RT-qPCR are closely correlated.

Figure 10.

Relative expression of 40 hub genes in potato stems at seedling, tuber formation and tuber expansion stages by RT-qPCR. Three independent biological replicates were performed for each sample, and significance was determined by Mann-Whitney statistical of statannot package (ns: p > 0.05; *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001; ****: p < 0.0001). SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.

Figure 10.

Relative expression of 40 hub genes in potato stems at seedling, tuber formation and tuber expansion stages by RT-qPCR. Three independent biological replicates were performed for each sample, and significance was determined by Mann-Whitney statistical of statannot package (ns: p > 0.05; *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001; ****: p < 0.0001). SS: Seedling stage; TFS: Tuber formation stage; TES: Tuber expansion stage.