Submitted:

19 December 2023

Posted:

19 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Genome-wide Identification and Molecular Characterization of USP in Atlantic Potatoes

2.2. Chromosome Localization and Gene Duplication Analysis of StUSPs in Atlantic Potato

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of StUSPs

2.4. Analysis of StUSPs Gene Structure,Domain, Conserved Motifs, and Secondary Structure

2.5. Analysis of Cis-acting Elements of StUSPs

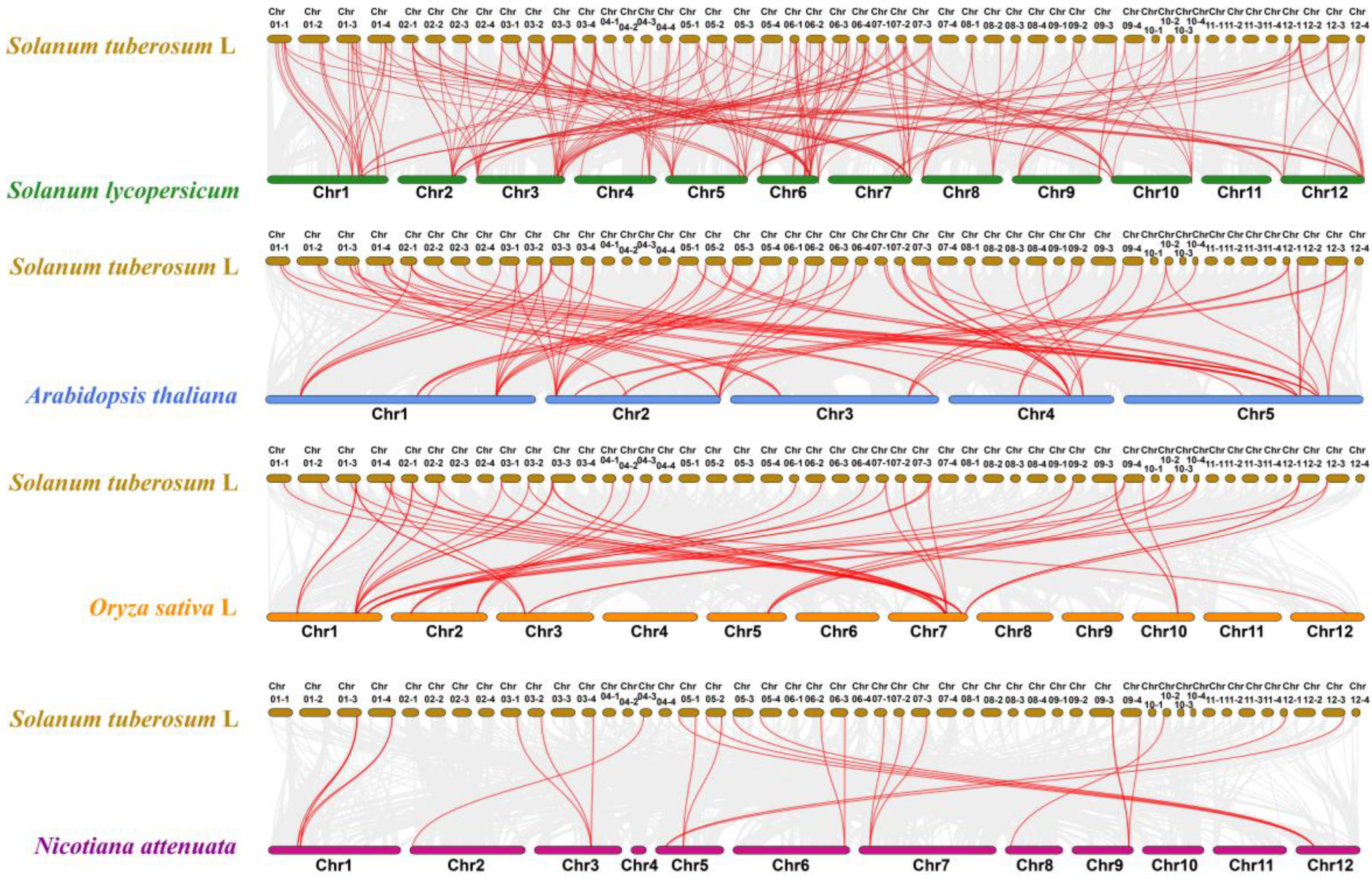

2.6. StUSP Gene Collinear Analysis

2.7. Analysis of Expression of StUSPs in Response to Mechanical Damageand and DON Stress

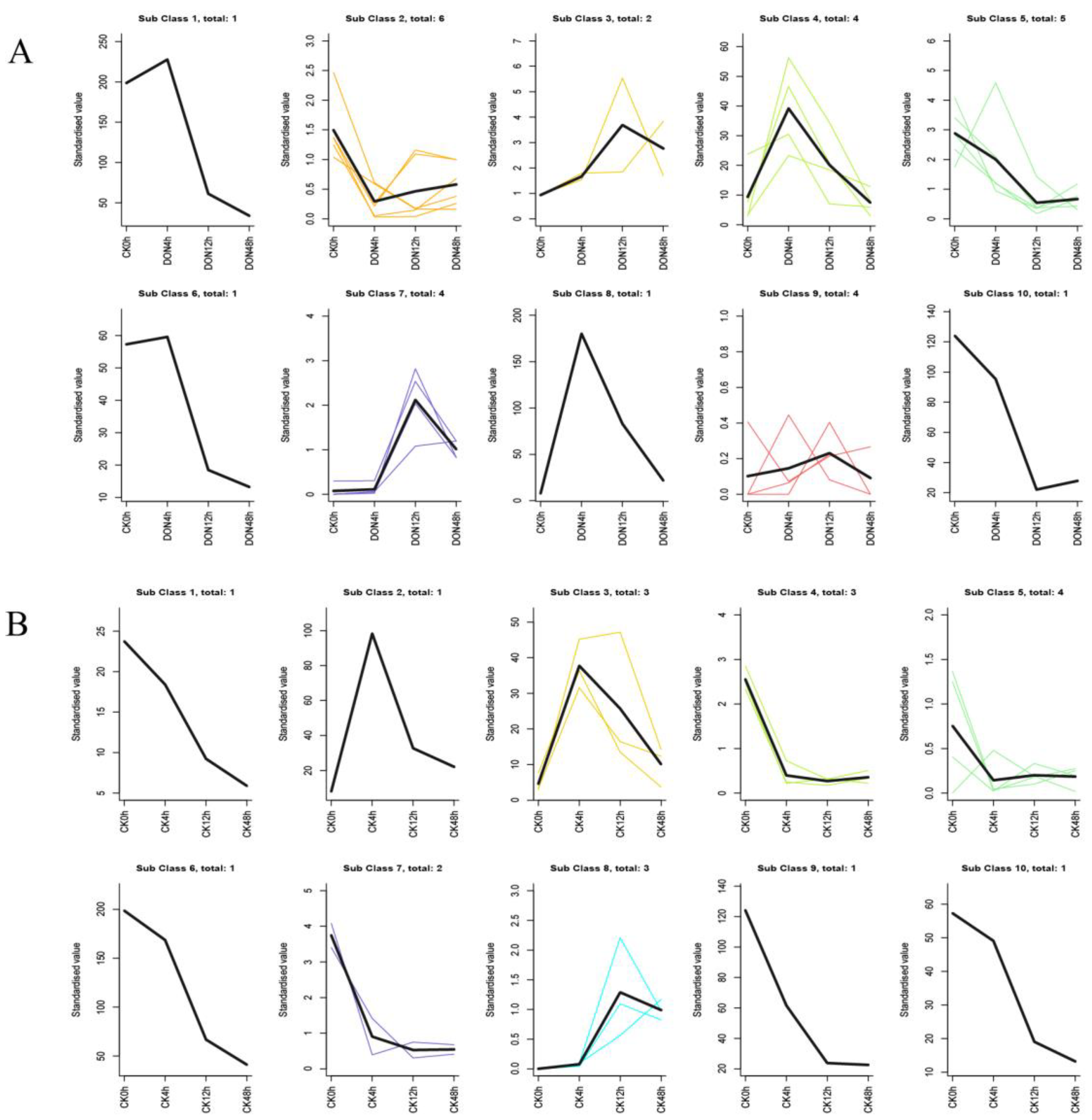

2.8. StUSPs K-means Analysis

2.9. Analysis of Gene Co-expression

2.10. qRT-PCR Verifies StUSP Gene Expression

3. Disscussion

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Identification of the USP Gene

4.2. Physical Mapping of Genes on Chromosomes and Collinearity Analysis

4.3. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

4.4. Exon-intron, Conserved Motif Analysis, and Cis-acting Element Analysis

4.5. Analysis of Physical and Chemical Properties, Secondary Structure, and Subcellular Localization

4.6. Plant Materials and Stress Treatment

4.9. Analysis of RNA-seq and StUSP Gene Expression

4.8. Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

4.7. Real-time Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) Verification

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, X.; Yang, R.; Zhang, L.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y. A Review of Potato Salt Tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, A.; Zaidi, S.S.; Shakir, S.; Mansoor, S. Applications of New Breeding Technologies for Potato Improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Cao, C.; Cao, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X. Dietary flavonol and flavone intakes and their major food sources in Chinese adults. Nutr. Cancer 2010, 62, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y.; Higashi, C.; Iwama, M.; Ishihara, K.; Handa, S.; Mugita, H.; Maruyama, N.; Koga, H.; Ishigami, A. Bioavailability of vitamin C from mashed potatoes and potato chips after oral administration in healthy Japanese men. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, B.; Mouillé, B.; Charrondière, R. Nutrients, bioactive non-nutrients and anti-nutrients in potatoes. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2009, 22, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro Cordeiro de Azeredo, H.; Carvalho de Matos, M.; Madazio Niro, C. Something to chew on: technological aspects for novel snacks. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 2191–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.A.; Barpete, S.; Akdogan, G.; Aydİn, G.; Sancak, C.; Ozcan, S. Efficient regeneration and Agrobacterium tumefaciens mediated genetic transformation of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2018, 27, 3020–3027. [Google Scholar]

- Loebenstein, G.; Gaba, V. Viruses of potato. Adv. Virus Res. 2012, 84, 209–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wahrenburg, Z.; Benesch, E.; Lowe, C.; Jimenez, J.; Vulavala, V.K.R.; Lü, S.; Hammerschmidt, R.; Douches, D.; Yim, W.C.; Santos, P.; et al. Transcriptional regulation of wound suberin deposition in potato cultivars with differential wound healing capacity. Plant J. 2021, 107, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Sun, Z.; Zou, Y.; Li, W.; He, F.; Huang, X.; Lin, C.; Cai, Q.; Wisniewski, M.; Wu, X. Pre- and postharvest measures used to control decay and mycotoxigenic fungi in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during storage. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr 2022, 62, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Ma, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, J.; Yan, Y. The toxicity mechanisms of DON to humans and animals and potential biological treatment strategies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 790–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, G.; Tiley, H.; McCormick, S. Chitin Triggers Tissue-Specific Immunity in Wheat Associated with Fusarium Head Blight. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 832502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.J.; Bitto, E.; Bingman, C.A.; Kim, H.J.; Han, B.W.; Phillips, G.N., Jr. Crystal structure of the protein At3g01520, a eukaryotic universal stress protein-like protein from Arabidopsis thaliana in complex with AMP. Proteins 2015, 83, 1368–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollmer, A.C.; Bark, S.J. Twenty-Five Years of Investigating the Universal Stress Protein: Function, Structure, and Applications. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 102, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nyström, T.; Neidhardt, F.C. Cloning, mapping and nucleotide sequencing of a gene encoding a universal stress protein in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1992, 6, 3187–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, N.; Diez, A.; Nyström, T. The universal stress protein paralogues of Escherichia coli are co-ordinately regulated and co-operate in the defence against DNA damage. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 43, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.C.; McKay, D.B. Structure of the universal stress protein of Haemophilus influenzae. Structure 2001, 9, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanBogelen, R.A.; Hutton, M.E.; Neidhardt, F.C. Gene-protein database of Escherichia coli K-12: edition 3. Electrophoresis 1990, 11, 1131–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.T.; Wei, Y.M.; Wang, J.R.; Liu, C.J.; Lan, X.J.; Jiang, Q.T.; Pu, Z.E.; Zheng, Y.L. Identification, localization, and characterization of putative USP genes in barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 121, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanyalakshmi, K.H.; Nataraja, K.N. Universal stress protein-like gene from mulberry enhances abiotic stress tolerance in Escherichia coli and transgenic tobacco cells. Plant Biol. 2021, 23, 1190–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havis, S.; Bodunrin, A.; Rangel, J.; Zimmerer, R.; Murphy, J.; Storey, J.D.; Duong, T.D.; Mistretta, B.; Gunaratne, P.; Widger, W.R.; et al. A Universal Stress Protein That Controls Bacterial Stress Survival in Micrococcus luteus. J. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00497–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Gene networks involved in drought stress response and tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Zhang, P.; Hu, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, Q.; Guan, P.; Zhang, J. Genome-wide analysis of the Universal stress protein A gene family in Vitis and expression in response to abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 165, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.C.; Jung, Y.J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, I.R.; Seol, M.A.; Kim, E.J.; Jang, M.K.; Lee, J.R. Functional characterization of the Arabidopsis universal stress protein AtUSP with an antifungal activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 486, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauter, M.; Rzewuski, G.; Marwedel, T.; Lorbiecke, R. The novel ethylene-regulated gene OsUsp1 from rice encodes a member of a plant protein family related to prokaryotic universal stress proteins. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 2325–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Beltrán, E.; Personat, J.M.; de la Torre, F.; Del Pozo, O. Universal Stress Protein Involved in Oxidative Stress Is a Phosphorylation Target for Protein Kinase CIPK6. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 836–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, S.; Ahmad, A.; Batool, F.; Rashid, B.; Husnain, T. Genetic modification of Gossypium arboreum universal stress protein (GUSP1) improves drought tolerance in transgenic cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 1779–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Singhal, C.; Sharma, A.K.; Khurana, P. Identification of universal stress proteins in wheat and functional characterization during abiotic stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 1487–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerk, D.; Bulgrien, J.; Smith, D.W.; Gribskov, M. Arabidopsis proteins containing similarity to the universal stress protein domain of bacteria. Plant Physiol. 2003, 131, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuria, M.; Goel, P.; Kumar, S.; Singh, A.K. The Promoter of AtUSP Is Co-regulated by Phytohormones and Abiotic Stresses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuria, M.; Goel, P.; Kumar, S.; Singh, A.K. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of genes encoding universal stress proteins (USP) identify multi-stress responsive USP genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 2019, 24, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.J.; Melencion, S.M.; Lee, E.S.; Park, J.H.; Alinapon, C.V.; Oh, H.T.; Yun, D.J.; Chi, Y.H.; Lee, S.Y. Universal Stress Protein Exhibits a Redox-Dependent Chaperone Function in Arabidopsis and Enhances Plant Tolerance to Heat Shock and Oxidative Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melencion, S.M.B.; Chi, Y.H.; Pham, T.T.; Paeng, S.K.; Wi, S.D.; Lee, C.; Ryu, S.W.; Koo, S.S.; Lee, S.Y. RNA Chaperone Function of a Universal Stress Protein in Arabidopsis Confers Enhanced Cold Stress Tolerance in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuria, M.; Goel, P.; Kumar, S.; Singh, A.K. AtUSP17 negatively regulates salt stress tolerance through modulation of multiple signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Physiol. Plant 2022, 174, 13635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loukehaich, R.; Wang, T.; Ouyang, B.; Ziaf, K.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Ye, Z. SpUSP, an annexin-interacting universal stress protein, enhances drought tolerance in tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 5593–5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Beltrán, E.; Personat, J.M.; de la Torre, F.; Del Pozo, O. A Universal Stress Protein Involved in Oxidative Stress Is a Phosphorylation Target for Protein Kinase CIPK6. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 836–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Qadir, I.; Aslam, A.; Rashid, B.; Bilal Sarwar, M.; Husnain, T. Cloning, Genetic Transformation and Cellular Localization of Abiotic Stress Responsive Universal Stress Protein Gene (GUSP1) in Gossypium hirsutum. Iran. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 18, 2312. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, A.; Arshad, K.; Hafeez, M. Cloning and expression of universal stress protein 2 (usp2) gene in Escherichia coli. Biol. Clin. Sci. Res. J. 2021, 2, 2708–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udawat, P.; Jha, R.K.; Sinha, D.; Mishra, A.; Jha, B. Overexpression of a Cytosolic Abiotic Stress Responsive Universal Stress Protein (SbUSP) Mitigates Salt and Osmotic Stress in Transgenic Tobacco Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Ahmad, A.; Batool, F.; Rashid, B.; Husnain, T. Genetic modification of Gossypium arboreum universal stress protein (GUSP1) improves drought tolerance in transgenic cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 1779–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, M.N.; Khan, M.A.; Sarwar, B.; Hassan, S.; Ali, Q.; Husnain, T.; Rashid, B. Mutant Gossypium universal stress protein-2 (GUSP-2) gene confers resistance to various abiotic stresses in E. coli BL-21 and CIM-496-Gossypium hirsutum. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo Blaha, C.A.; Schrank, I.S. An Azospirillum brasilense Tn5 mutant with modified stress response and impaired in flocculation. Antonie Van. Leeuwenhoek 2003, 83, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.; Rai, R.; Chatterjee, A.; Rai, S.; Yadav, S.; Agrawal, C.; Rai, L.C. Molecular characterization of two novel proteins All1122 and Alr0750 of Anabaena PCC 7120 conferring tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in Escherichia coli. Gene 2019, 685, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkouropoulos, G.; Andreasson, E.; Hess, D.; Boller, T.; Peck, S.C. An Arabidopsis protein phosphorylated in response to microbial elicitation, AtPHOS32, is a substrate of MAP kinases 3 and 6. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 10493–10499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerk, D.; Bulgrien, J.; Smith, D.W.; Gribskov, M. Arabidopsis proteins containing similarity to the universal stress protein domain of bacteria. Plant Physiol. 2003, 131, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqbool, A.; Zahur, M.; Husnain, T.; Riazuddin, S. GUSP1 and GUSP2, Two Drought-Responsive Genes in Gossypium arboreum Have Homology to Universal Stress Proteins. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 2009, 27, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.T.; Wei, Y.M.; Wang, J.R.; Liu, C.J.; Lan, X.J.; Jiang, Q.T.; Pu, Z.E.; Zheng, Y.L. Identification, localization, and characterization of putative USP genes in barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2010, 121, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, P.; Pazhamala, L.T.; Singh, V.K.; Saxena, R.K.; Krishnamurthy, L.; Azam, S.; Khan, A.W.; Varshney, R.K. Identification and Validation of Selected Universal Stress Protein Domain Containing Drought-Responsive Genes in Pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 6, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.H.; Koo, S.S.; Oh, H.T.; Lee, E.S.; Park, J.H.; Phan, K.A.T.; Wi, S.D.; Bae, S.B.; Paeng, S.K.; Chae, H.B.; et al. The Physiological Functions of Universal Stress Proteins and Their Molecular Mechanism to Protect Plants From Environmental Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, J.; Gu, W.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zou, H.; Zong, C.; Ma, L. Comprehensive Analysis of Universal Stress Protein Family Genes and Their Expression in Fusarium oxysporum Response of Populus davidiana × P. alba var. pyramidalis Louche Based on the Transcriptome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhang, P.; Hu, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, Q.; Guan, P.; Zhang, J. Genome-wide analysis of the Universal stress protein A gene family in Vitis and expression in response to abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 165, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.F.; Su, J.; Yang, N.; Zhang, H.; Cao, X.Y.; Kang, J.F. Functional Characterization of Selected Universal Stress Protein from Salvia miltiorrhiza (SmUSP) in Escherichia coli. Genes 2017, 8, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoopes, G.; Meng, X.; Hamilton, J.P.; Achakkagari, S.R.; de Alves Freitas Guesdes, F.; Bolger, M.E.; Coombs, J.J.; Esselink, D.; Kaiser, N.R.; Kodde, L.; et al. Phased, chromosome-scale genome assemblies of tetraploid potato reveal a complex genome, transcriptome, and predicted proteome landscape underpinning genetic diversity. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 2000, 408, 796–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duitama, J.; Silva, A.; Sanabria, Y.; Cruz, D.F.; Quintero, C.; Ballen, C.; Lorieux, M.; Scheffler, B.; Farmer, A.; Torres, E.; et al. Whole genome sequencing of elite rice cultivars as a comprehensive information resource for marker assisted selection. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomato Genome Consortium. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature 2012, 485, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Brockmöller, T.; Navarro-Quezada, A.; Kuhl, H.; Gase, K.; Ling, Z.; Zhou, W.; Kreitzer, C.; Stanke, M.; Tang, H.; et al. Wild tobacco genomes reveal the evolution of nicotine biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 6133–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.M.; Rehman, A.; Razzaq, A.; Parvaiz, A.; Mustafa, G.; Sharif, F.; Mo, H.; Youlu, Y.; Shakeel, A.; Ren, M. Genome-wide characterization and expression analysis of Erf gene family in cotton. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadde, B.V.L. Not-so-selfish DNA? Intronic enhancers fine-tune spatiotemporal gene expression. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 1851–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudelaar, A.M.; Higgs, D.R. The relationship between genome structure and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021, 22, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuria, M.; Goel, P.; Kumar, S.; Singh, A.K. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of genes encoding universal stress proteins (USP) identify multi-stress responsive USP genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Rep. 2019, 24, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahur, M.; Maqbool, A.; Ifran, M.; Barozai, M.Y.; Rashid, B.; Riazuddin, S.; Husnain, T. Isolation and functional analysis of cotton universal stress proteinpromoter in response to phytohormones and abiotic stresses. Mol. Biol. 2009, 43, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zuo, L.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, J.; Tao, J.; Chen, C. Protein Kinase RhCIPK6 Promotes Petal Senescence in Response to Ethylene in Rose (Rosa Hybrida). Genes. 2022, 13, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Che, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wei, T.; Yan, G.; Song, W.; Yu, W. Universal stress protein in Malus sieversii confers enhanced drought tolerance. J. Plant Res. 2019, 132, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkouropoulos, G.; Tsaftaris, A.S. Differential Expression of Gossypium hirsutum USP-Related Genes, GhUSP1 and GhUSP2, During Development and upon Salt Stress. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 31, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Kwon, H.; Yang, X.; Lee, S.H. Novel QTL identification and candidate gene analysis for enhancing salt tolerance in soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Plant Sci. 2021, 313, 111085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabia, S.; Sami, A.A.; Akhter, S.; Sarker, R.H.; Islam, T. Comprehensive in silico Characterization of Universal Stress Proteins in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) With Insight Into Their Stress-Specific Transcriptional Modulation. Front. Plant Sci 2021, 12, 712607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazuko, Y.S.; Masahiro, K.; Satomi, U.; Kazuo, S. Molecular cloning and characterization of 9 cdnas for genes that are responsive to desiccation in arabidopsis thaliana: sequenceanalysis of one cdna clone that encodes a putative transmembrane channel protein. Plant Cell Physiol. 1992, 3, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzali, S.; Loreti, E.; Cardarelli, F.; Novi, G.; Parlanti, S.; Pucciariello, C.; Bassolino, L.; Banti, V.; Licausi, F.; Perata, P. Universal stress protein HRU1 mediates ROS homeostasis under anoxia. Nat. Plants 2015, 1, 15151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X.; van der Does, C.; Albers, S.V. SaUspA, the Universal Stress Protein of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius Stimulates the Activity of the PP2A Phosphatase and Is Involved in Growth at High Salinity. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 598821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, C.S.; Torres, A.G.; Caravelli, A.; Silva, A.; Polatto, J.M.; Piazza, R.M. Characterization of the universal stress protein F from atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and its prevalence in Enterobacteriaceae. Protein Sci. 2016, 25, 2142–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udawat, P.; Mishra, A.; Jha, B. Heterologous expression of an uncharacterized universal stress protein gene (SbUSP) from the extreme halophyte, Salicornia brachiata, which confers salt and osmotic tolerance to E. coli. Gene 2014, 536, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, J.; Chuguransky, S.; Williams, L.; Qureshi, M.; Salazar, G.A.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; Tosatto, S.C.E.; Paladin, L.; Raj, S.; Richardson, L.J.; et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, J.; Finn, R.D.; Eddy, S.R.; Bateman, A.; Punta, M. Challenges in homology search: HMMER3 and convergent evolution of coiled-coil regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Geer, L.Y.; Geer, R.C.; He, J.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; et al. CDD: NCBI’s conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D222–D226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Debarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.H.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchy, N.; Lehti-Shiu, M.; Shiu, S.H. Evolution of Gene Duplication in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2294–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.Q.; Wang, J.; Wong, G.K.; Yu, J. KaKs_Calculator: calculating Ka and Ks through model selection and model averaging. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2006, 4, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Bowers, J.E.; Wang, X.; Ming, R.; Alam, M.; Paterson, A.H. Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science 2008, 320, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. Meme Suite: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasteiger, E.; Gattiker, A.; Hoogland, C.; Ivanyi, I.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3784–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.J.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W585–W587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geourjon, C.; Deléage, G. SOPMA: significant improvements in protein secondary structure prediction by consensus prediction from multiple alignments. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1995, 11, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolde R: pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps.R package version 1.0.12 ed.2019.

- McLachlan, G.J.; Bean, R.W.; Ng, S.K. Clustering. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1526, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gene Ontology Consortium. Gene Ontology Consortium: going forward. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D1049–D1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Coulouris, G.; Zaretskaya, I.; Cutcutache, I.; Rozen, S.; Madden, T.L. Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, Z. Identification and Validation of Reference Genes for Gene Expression Analysis in Schima superba. Genes. 2021, 12, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).