1. Introduction

As early as 2010, IFN-λ3 cDNA prediction sequences of bovine type III IFN published in NCBI and first cloned in 2011[

1]. It is located on chromosome 18 and contains 588 bases, encoding 195 amino acids and 23 signal peptides. IFN-λ which is also known as IL-28B have remarkable antiviral activity and immunomodulatory function and is expressed to varying degrees in different tissues and organs[

2]. Human IFN-λ1 is a glycosylated protein while IFN-λ2 and IFN-λ3 are not. The two members of the mouse type III interferon family (IFN-λ2 and IFN-λ3) are located on chromosome 7A3 of mice, with a 98% similarity in their genes. It is worth noting that IFN-λ1 is a pseudogene, while both IFN-λ2 and IFN-λ3 undergo glycosylation modification[

3]. Antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells are the central cells that produce IFN-λ induced by virus or RNA.

Ifn-λ gene was significantly expressed after infection with influenza virus or/and stimulation with pathogen-associated molecular pattern, such as lipopolysaccharide or poly I: C[

4,

5]. In skin tissue, IFN-λ is secreted by dendritic cells and regulatory T cells and has biological effects on keratinocytes and melanocytes[

6].

P. pastoris combines the advantages of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic expression systems, with easy preparation and purification, and is suitable for high-level expression, and is characterized not only by intracellular and secretory expression but also by post-translational modifications[

7,

8]. More than 500 proteins have been successfully expressed in

P. pastoris expression system[

9]. The bovine IFN-α was efficiently expressed through codon optimization of

P. pastoris, which expression yield was about three times than that wild type at the same copies, and opti-boIFN-α showed antiviral activity in MDBK and IBRS-2 cells all over 10

5 U/mg against VSV[

7].

P. pastoris expression involves modifying precursor proteins via proper folding, disulfide bond formation, and moderate O-glycosylation and N-glycosylation. Protein folding and disulfide bond formation are recognized as rate-limiting steps in the expression of exogenous proteins in

P. pastoris. The organism's ability to process, fold and secrete recombinant proteins determines the productivity of the yeast expression system. Over-glycosylation of yeast or protein in some natural active states is non-glycosylated, while yeast expression shows glycosylation, which is an unfavorable factor for

P. pastoris expression. This type of protein often results in defects in biological activity and an increase in adverse reactions. Genetic engineering and exogenous gene modification technology can be used to mutate or modify glycosylation sites[

10].

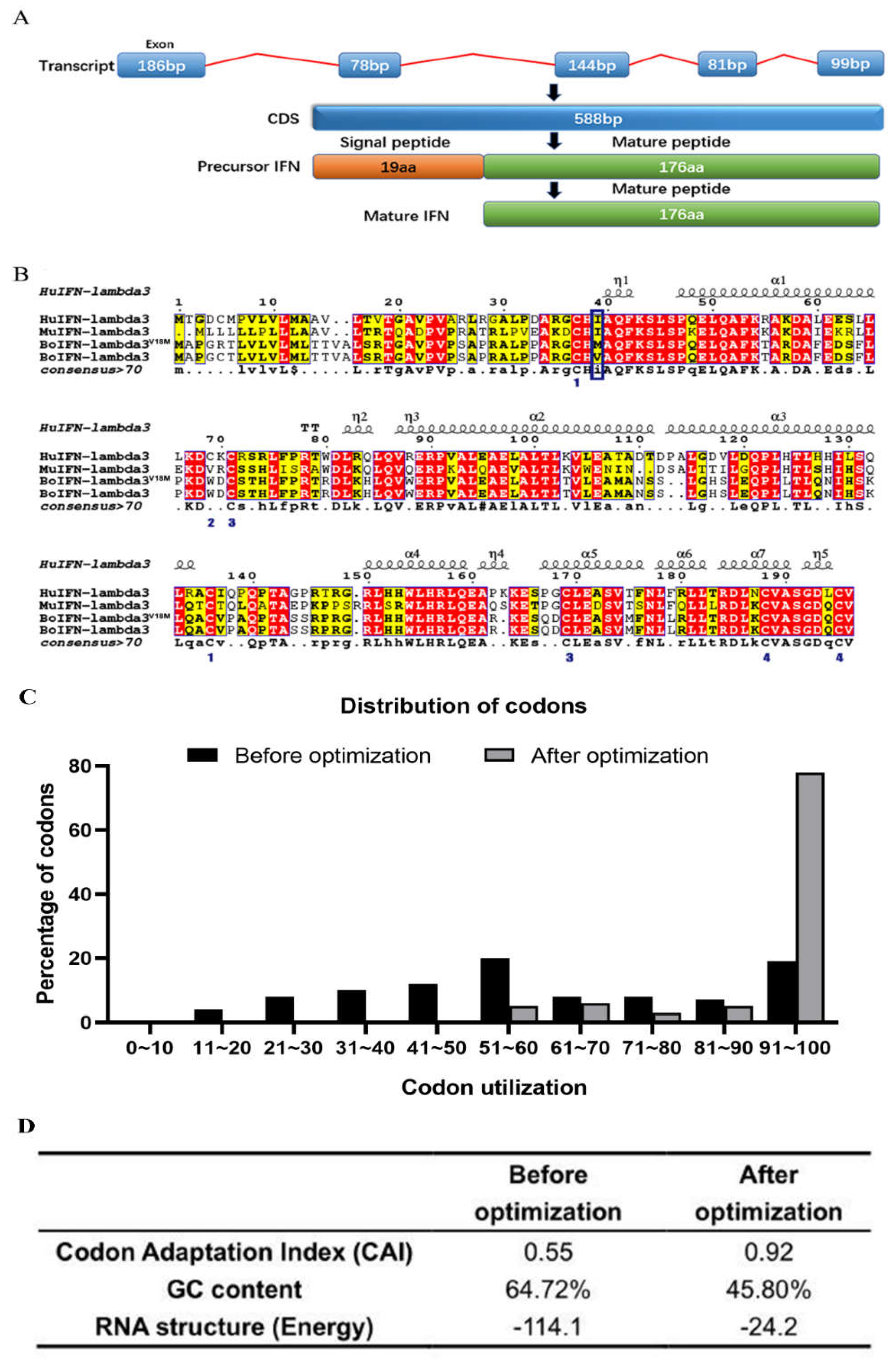

To achieve high-level expression of bovine IFN-λ3 (boIFN-λ3), we optimized boIFN-λ3, and achieved extracellular expression of optimized (opti)-boIFN-λ3 in P. pastoris. We amplified the 18th amino acid mutant of boIFN-λ3 by accident. This study intends to express boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M by P. pastoris production system. We compared the biological activity of the optimized codon between boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M. To further understand the biological function of boIFN-λ3 and provide material for the preparation of antiviral agents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plasmid, strains, cells, virus and antibody

The competent cell DH5α were preserved and used in our laboratory P. pastoris. The host strain GS115 and expression vector pPICZαA were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, United States). Madin–Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) cells were preserved in our laboratory. VSV (Vesicular Stomatitis Virus) was purchased from the China Institute of Veterinary Drug Control. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies (PAb) against human IL-28B (IFN-λ3) (GTX123335) were purchased from GeneTex (CA, USA), Rabbit PAb against bovine IL-28B (IFN-λ3) is prepared by our laboratory.

2.2. Design and synthesis of boIFN-λ3

Codon usage of predicting and cloned boIFN-λ3 (GenBank Accession No. XM_002695050 and No. HQ317919) from Bos taurus was analyzed using Dnastar Lasergene software and optimized by replacing a base frequently used in

P. pastoris with frequently used codons and changed single-nucleotide using by PCR amplification resulting in the 18th amino acid of the mature peptide, the former (called opti-boIFN-λ3, GenBank Accession No. OQ565418) being valine (V) and the latter (called boIFN-λ3V18M, GenBank Accession No. OQ565419) methionine (M). Opti-boIFN-λ3, referring to the principle of gene splicing by overlap extension (SOE), designed 14 oligonucleotide chains with about 20 bp overlap each other (

Table 1). BGI Co., Ltd synthesized the oligonucleotide chains.

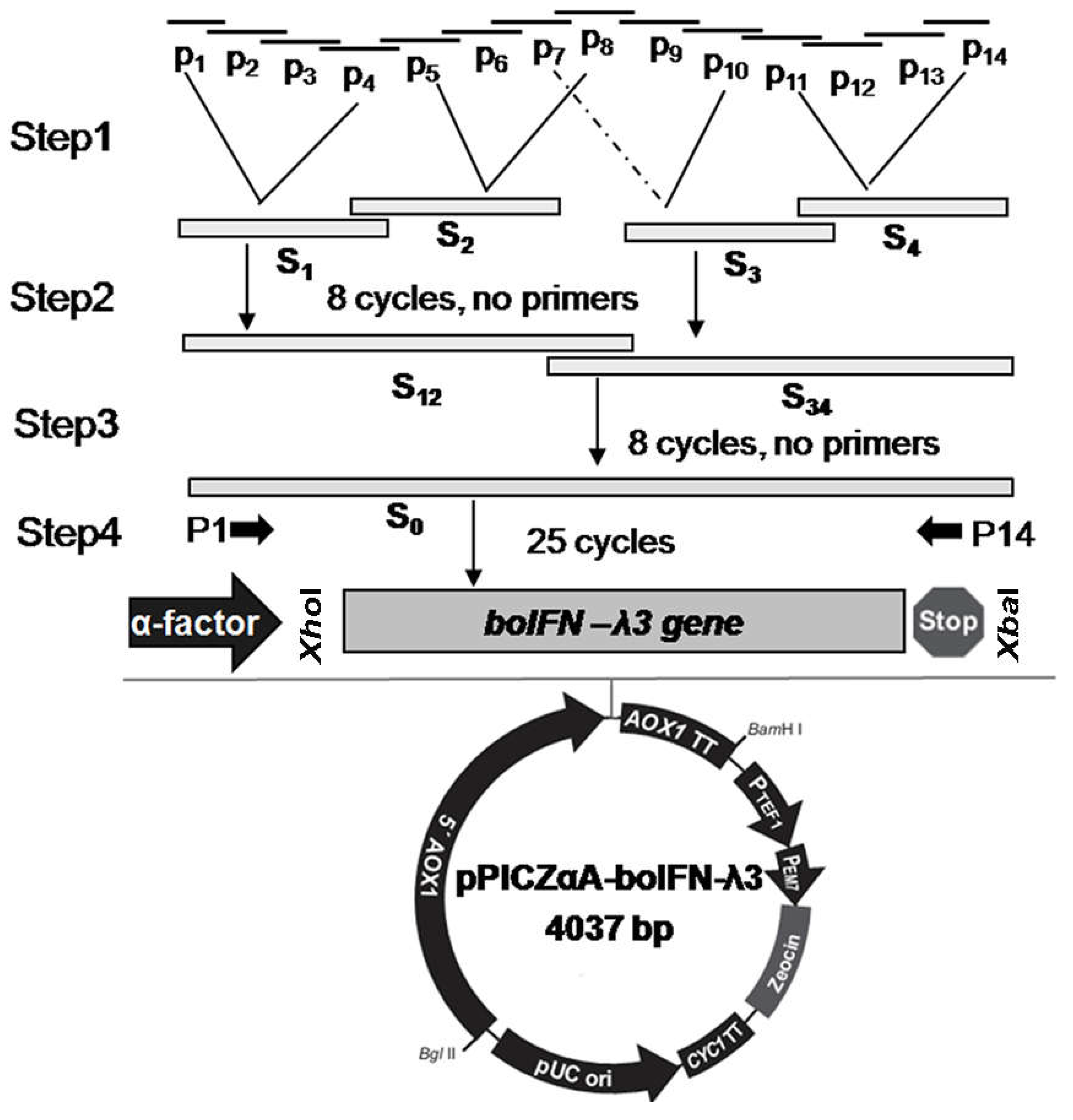

2.3. Construction of recombinant expression vector

The

boifn-λ3 gene was amplified with SOE PCR, each of the four oligonucleotide chains P1 ~ P4, P5 ~ P8, P7 ~ P10 and P11 ~ P14 were fused to obtain S1 ~ S4 product fragments, and then S1 and S2, S3 and S4 products were fused to obtain S12 and S34 fusion fragments, respectively. The fusion fragments were fused to obtain the template for boIFN-λ3 amplification, and then P1 and P14 were used for ordinary PCR amplification (

Figure 1). The

boifn-λ3/λ3V18M gene fragment ligated to the pPICZαA vector between

Xho I and

Xba I sites, the restriction enzyme (TaKaRa, Japan) sites are underlined corner markers. P2 is for cloning boIFN-λ3, while P2′ for boIFN-λ3

V18M, then recombinant plasmid pPICAαA-boIFN-λ3/λ3

V18M was obtained and transformed into

E. coli DH5α (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). Positive transformants identified using restriction analysis and sequencing. Then the plasmids pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3/λ3

V18M and pPICZαA were linearized with

Sac I, and transformed into competent

P. pastoris GS115 cells mediated by electroporation separately. After incubation in YPD (Yeast Extract-Peptone Dextrose) medium with zeocin at 30 °C for at least 72 h, the gene integration was verified by PCR using yeast genomic DNA as a template, and 5′AOX1(5′-GACTGGTTCCAATTGAGAAGC-3′) and 3′AOX1(5′-GCAAATGGCATTCTGACATCC-3′) as primers, and positive transformants were selected for expression.

2.4. Expression and identification of boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M

Selected positive transformants transformed in P. pastoris GS115 cells were grown in BMGY (Buffered Glycerol-complex Medium) at 28 °C until an OD600 of between 2 and 6 was reached, and then centrifuged and resuspended with BMMY (Buffered Methanol-complex Medium). After induction, the entire culture supernatant was harvested by centrifuging at 3000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. Then SDS-PAGE was performed to analyze the expression of boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M, and Western blot was used to analyze the specificity of boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M with rabbit PAb against human/bovine IL-28B.

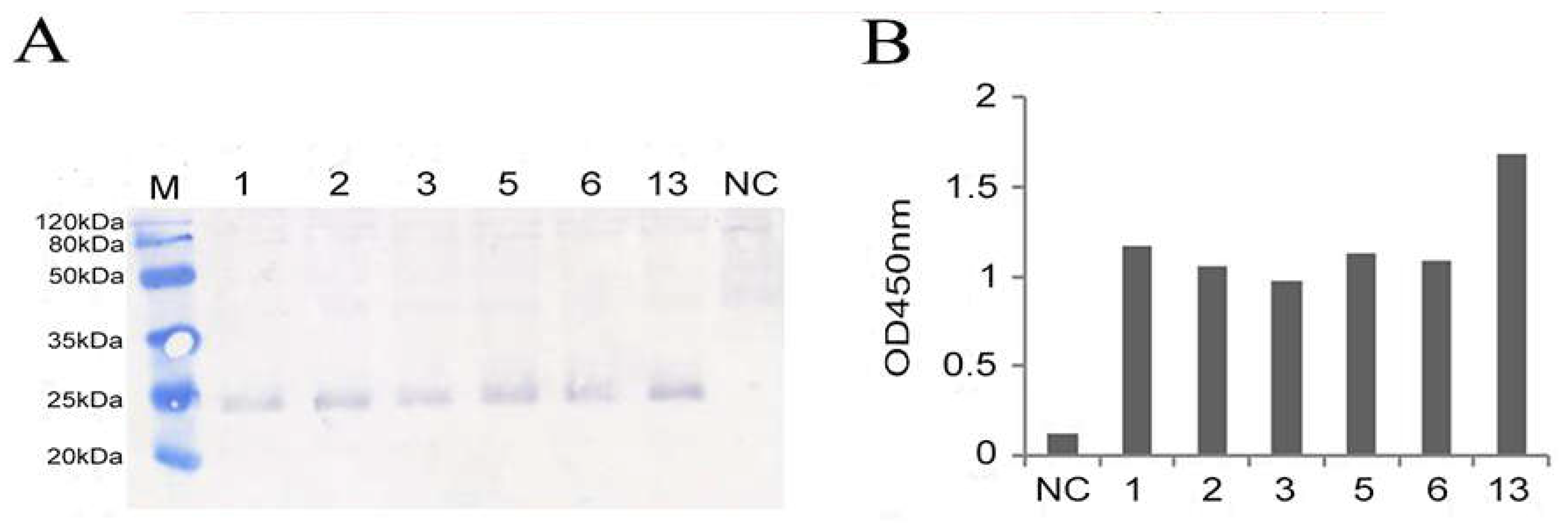

2.5. Screening dominant expression strains of boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M

Western blot analysis was performed to screen for protein expression. Supernatant was collected from the expressing strain after 72 h and 6 μL was spotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and allowed to dry naturally. PBST and supernatant from induced GS115-pPICZαA were used as controls. The membrane was blocked with 5% skimmed milk PBST and incubated with a dilution of rabbit anti-human IL-28B primary antibody followed by HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. The membrane was washed and developed using a CN/DAB substrate kit (Thermo Scientific, USA)[

11].

ELISA analysis was performed to screen for protein expression. Supernatant was collected from the expressing strain after 72 h and diluted appropriately with 0.05M carbonate buffer (pH9.6) to serve as the coating solution. The solution was added to ELISA plates and incubated at 4 °C overnight. The plates were then blocked with 5% skimmed milk and incubated with serial dilutions of rabbit PAb against human IL-28B antibody. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was used as the secondary antibody. Reactivity was visualized by color development using a chromogen/substrate mixture of 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine/H

2O

2 (Sigma–Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA). The reaction was terminated using 1M H

2SO

4 and the absorbance of each well at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA)[

12].

2.6. Optimization of expression conditions

Selected recombinant strains integrated with the boifn-λ3/λ3V18M gene were cultivated in 25 mL of BMGY medium at 28 °C with constant shaking at 200 × g until OD600 was about 2. The recombinant protein was induced in a BMMY medium with methanol at a 0.5 % final concentration. At 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, 48 h, 60 h, 72 h, 84 h, and 96 h, supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 12000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. Similarly, methanol was added to a final concentration of 0.5%, 1%, 1.5%, 2%, 3%, 4% to maintain induction. Clarified supernatants were collected for SDS-PAGE analysis or protein purification.

2.7. Purification of boIFN-λ3

The expressed boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M was purified with ammonium sulfate precipitation and ion exchange chromatography, and dialyzed with PBS for 48 h. The final protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, Beijing, China). Detailed description is as follows:

For the ammonium sulfate precipitation method, samples of supernatant of cleared yeast were poured into the beakers. While stirring at 4 °C with a final concentration of 60 % ammonium sulfate. After the addition was complete, samples were left to stand overnight at 4 °C and then centrifuged at 5000 × g for 15 min. Next, the supernatants were carefully removed and pellets were resuspended into 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH8.0, containing 0.15 M NaCl and 1 mM CaCl2 and dialyzed for 24 h to 48 h to remove NaCl. The suspensions were centrifuged at 12000 × g for 15 min to remove any remaining debris. Supernatants and dissolved pellets were analyzed for the presence of boIFN-λ3. For the ion exchange and gel filtration chromatography, the ammonium sulfate fraction was applied to a column (1.25 × 6 cm) of Q-Sepharose FF (Pharmacia Biotechnology) equilibrated with 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH6.8. The column was washed with the same buffer, and bound protein was eluted by the step wise addition of buffers containing 0.25 M, 0.5 M and 1.0 M NaCl. Fractions of 6 mL were collected dialyzed again by PBS, and the protein concentration was determined after PEG20000 concentration. The collected solution was purified by Sephadex G-50 Sephadex (Pharmacia Biotechnology) gel filtration chromatography. The protein equilibrium and elution by PBS.

2.8. Recombinant protein glycosylation analysis

Purified recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M were stained for glycoprotein analysis using the Protein Stains R Glycoprotein Gel Staining Kit from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China).

2.9. Antiviral activity assay

Antiviral activity of the recombinant of boIFN-λ3/λ3

V18M were titrated as described and measured on the MDBK/VSV system, with modifications[

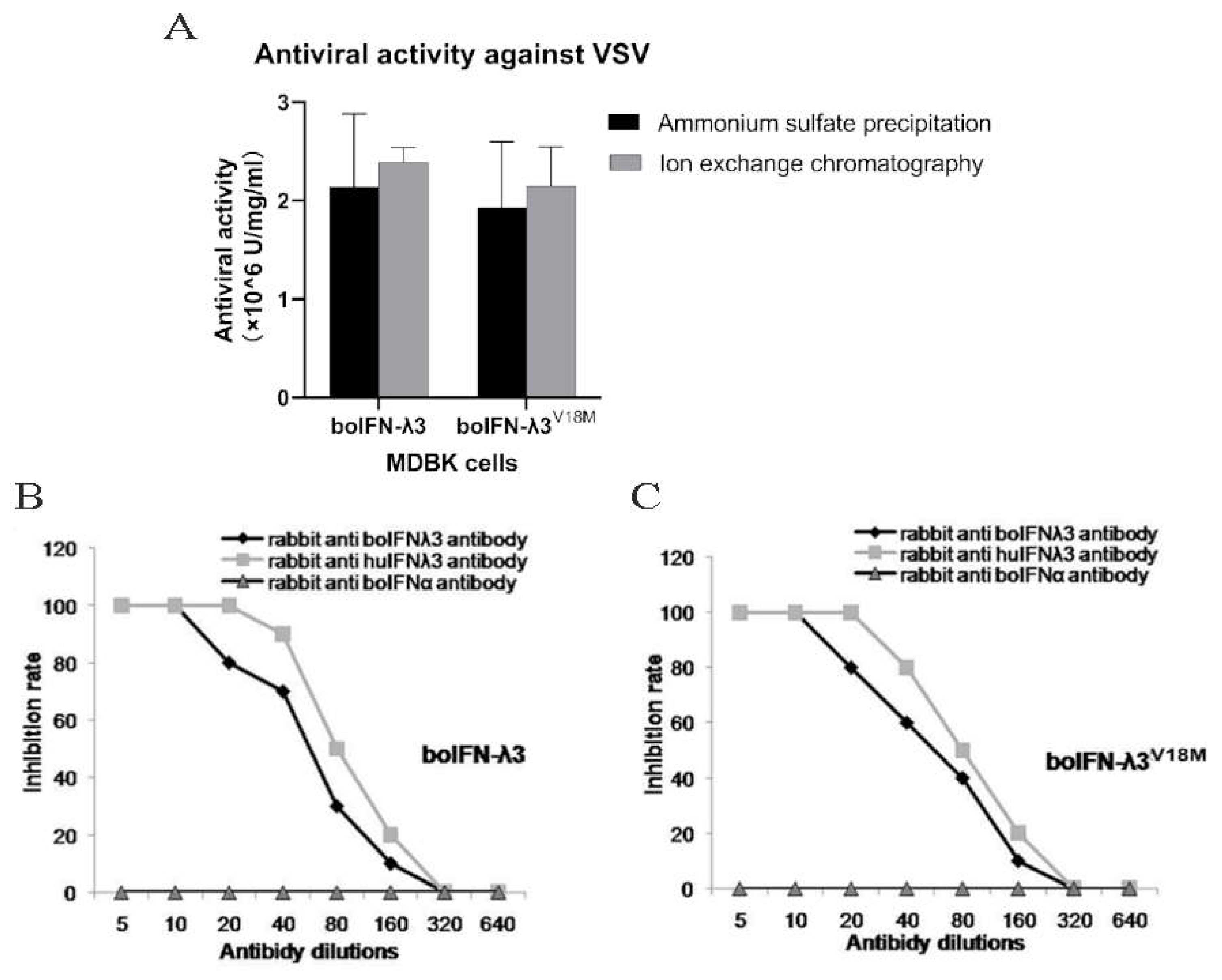

13]. MDBK cells in 96-well plates were grown to approximately 90% confluence. Then, 100 μL of purified boIFN supernatant were both fourfold serial dilutions for 24 h, and challenged with 100TCID50 VSV for another 24~48 h. Antiviral activity units (U) of IFN were calculated by the Reed-Muench method. The wells without viruses were considered as the mock-treated controls, and the wells without IFNs were designated as the virus controls. One unit of interferon activity was defined as the amount to inhibit the destruction of the cell monolayer by 50%[

14].Rabbit anti-bovine and Rabbit anti-human IFN-λ3 PAb were diluted gradiently and mixed with 100 U/mg/ boIFN-λ3. Each PAb was diluted in a 96-well plate, and the inhibition effect of PAb on IFN was determined at 37 °C for 1 h. Rabbit anti-bovine IFN-α PAb was used as a negative control[

15].

2.10. Physicochemical characteristics analysis of boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M

boIFN-λ3/λ3

V18M was treated with trypsin at a final concentration of 0.25% and then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. boIFN-λ3/λ3

V18M was centrifuged at 15000 × g 4 °C for 20 min. The boIFN-λ3/λ3

V18M samples adjusted to pH2.0, 4.0 and 10.0, 12.0 with HCl and NaOH were incubated at 4 °C for 24 h, then the pHs were adjusted back to the original pH of boIFN-λ3/λ3

V18M. The boIFN-λ3/λ3

V18M samples were separately incubated at 42 °C, 56 °C, and 63 °C for 2 h. MDBK/VSV system was used to assess the antiviral activity with respect to that of the untreated boIFN-λ3/λ3

V18M samples[

8,

14,

16].

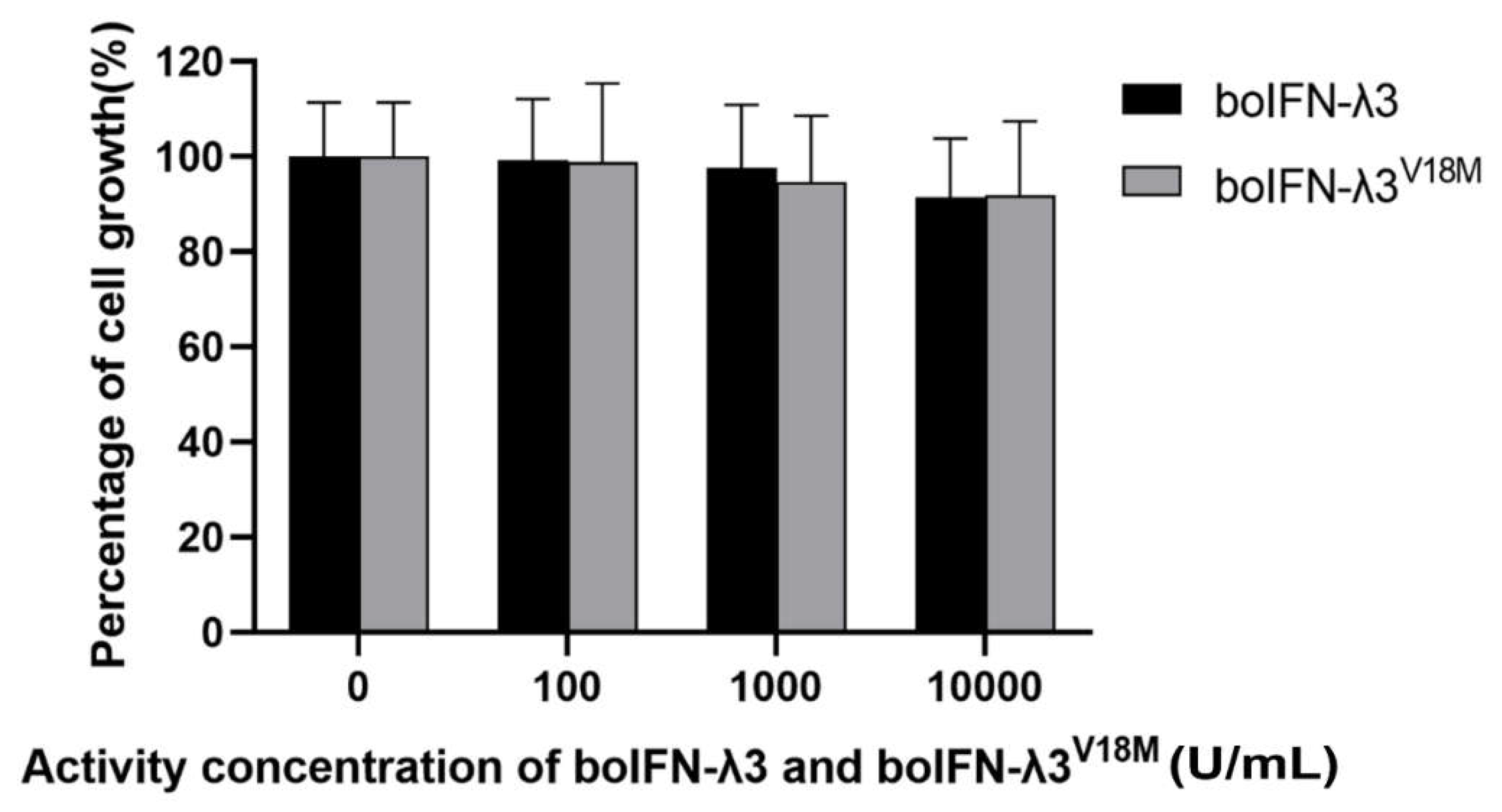

2.11. Antiproliferative assays of boIFN-λ3

The antiproliferative activity of boIFN-λ3 on MDBK cells was measured by MTT assay[

8]. Cells seeded in 96-well plates were treated with 0 U/mL, 10 U/mL, 100 U/mL, 1000 U/mL, and 10000 U/mL boIFN-λ separately and then incubated with MTT for 4 h. DMSO was added after removing the culture medium, and OD490 was measured.

2.12. Statistical

All experiments were repeated three independent times. Data are expressed as the mean values standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software. Statistical significance of the differences between groups was determined by Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests: * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

IFN-λs, as a type III interferon family, has potential development in the treatment of viral infection, which with more excellent antiviral and immunomodulatory effects than type I IFN[

17]. To obtain a large number of bioactive boIFN-λ3 similar to native boIFN-λ3. We prepared the optimized

boifn-λ3 gene by considering the yeast codon usage preference, the mRNA free energy, and secondary structure[

18], which was designed and developed. After optimization, the codon adaptation index was improved and the GC content was decreased. However, the free energy after optimization is not lower than before, in other words, the structure is not stable after optimization, indicating that the natural conformation is the most suitable structure for preferential stability.

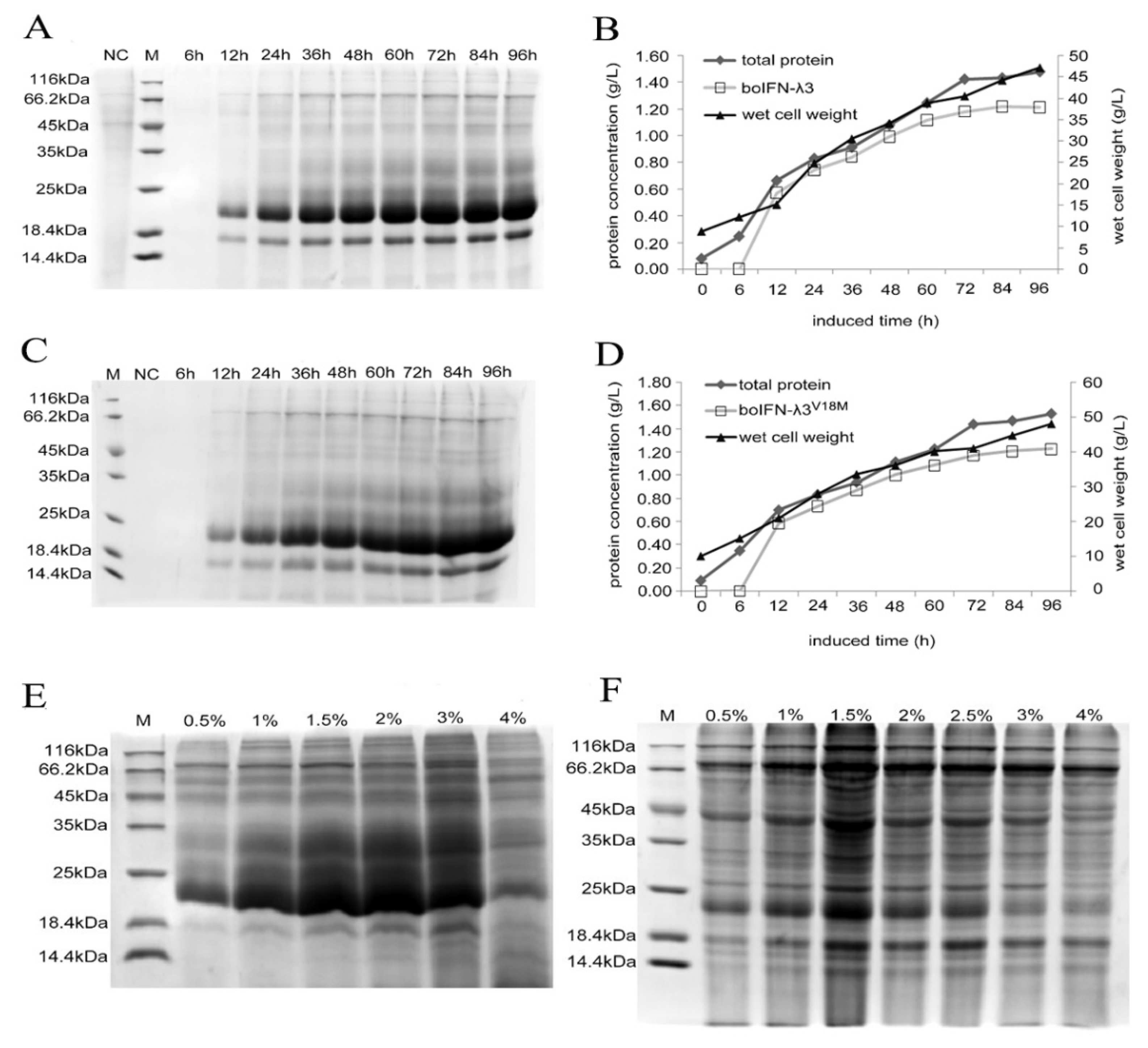

We optimized the methanol concentration and induction time which play an essential role in the amount of protein secreted and expressed by

P. pastoris. Methanol is the principal carbon source and gene expression inducer in

P. pastoris fermentation strategy, and its level affects cell growth and productivity. The expression of recombinant protein requires at least 0.5% methanol concentration, methanol-induced expression of the optimal concentration of up to 2~2.5%. Low concentration of methanol will cause the proteolytic degradation of the expressed protein. In addition, methanol with a concentration greater than 5% is toxic to cells[

19]. Our results showed that with the increase of methanol concentration, the expression of the target protein also increased, and after a certain methanol concentration reached the peak, the expression of the protein was significantly inhibited under high concentration of methanol, indicating that with the increase of methanol concentration, the cell may be damaged and its expression decreased. This is basically consistent with the above reviews.

Incubation time is one of the factors affecting the highest protein expression in

P. pastoris expression system. About 100 h of production time is relatively long. The incubation time was related to the number of yeast cells and the degree of target protein degradation. Studies have shown that

P. pastoris cells grow fastest at 96 h, whereas protein expression is highest at 48 h. It is likely that longer incubation time cause more proteolytic digestion of the expressed protein. Some studies suggest that optimal time for protein expression at 72 to 96 h[

19]. Our results confirm this, we can get the optimal expression time within 100 h, and determine the optimal expression at 72 h, with the further extension of time, the expression level is not obvious and showed a downward trend, may be caused by protein hydrolysis. In addition, such as

AOX gene subtypes, sorbitol concentration and temperature factors will affect the expression of the target protein, which is what we need to consider in the future to further optimize the expression.

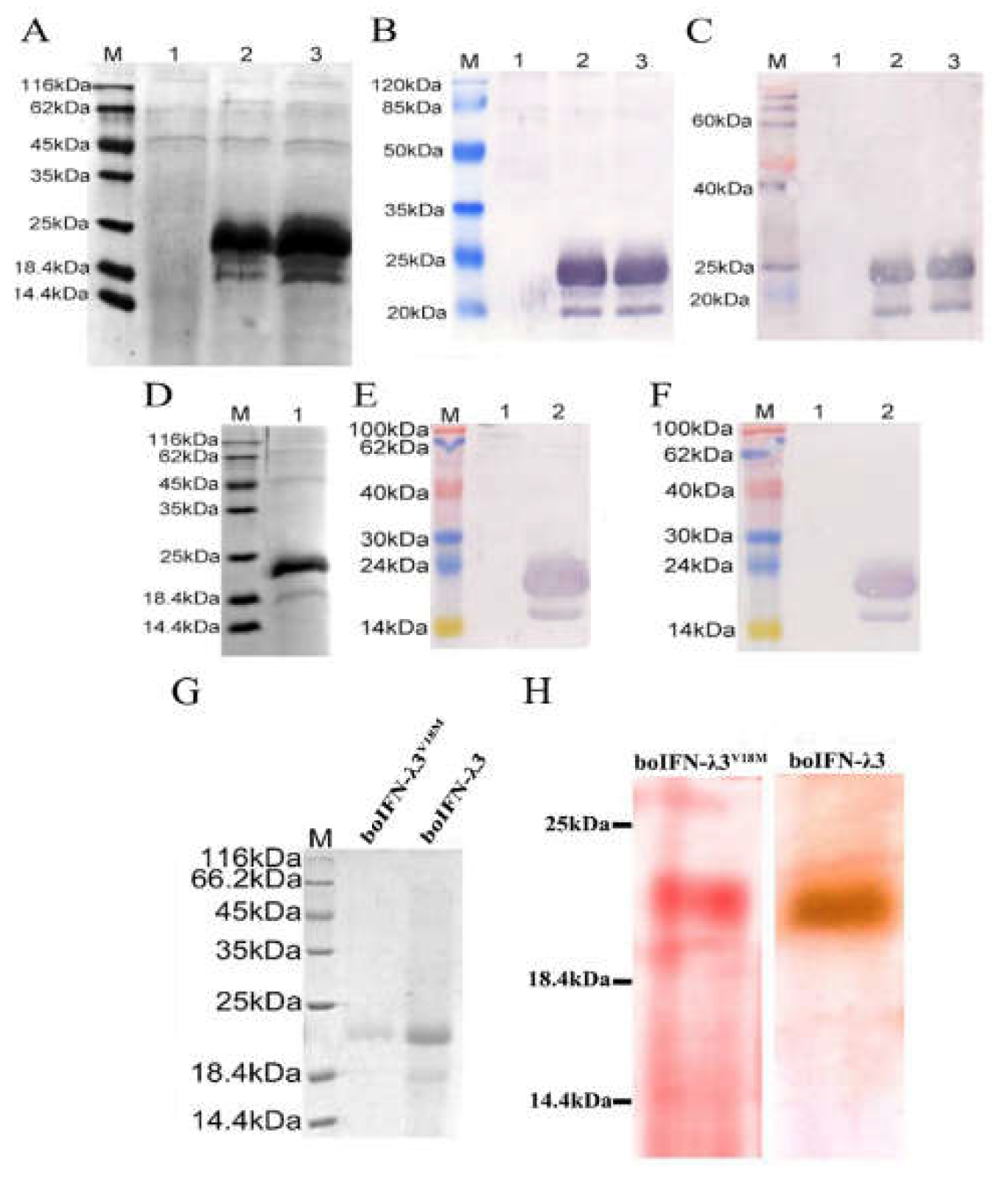

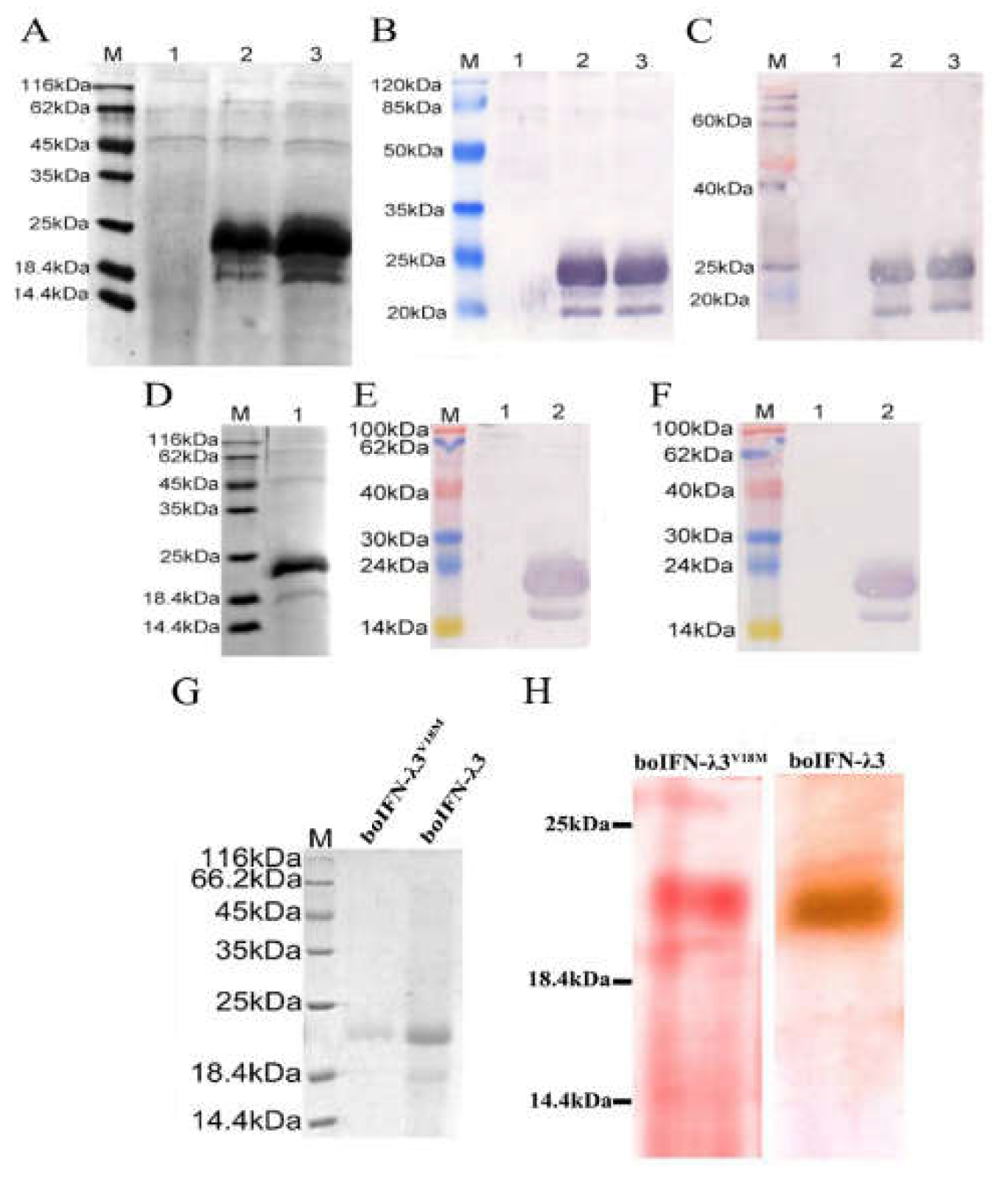

In this study,

P. pastoris secreted boIFN-λ3 and the target protein accounted for more than 85% of the total protein. Therefore, in the aspect of purification, the ammonium sulfate salting-out method was first selected for crude extraction. Then, depending on the theoretical isoelectric point of boIFN-λ3 for the characteristics of 8.31 and the molecular weight between 17~23 kDa, the crude protein was purified by cation exchange chromatography and gel filtration chromatography. Unfortunately, only the former purity 92% of the target protein. Gel filtration chromatography did not further obtain the target protein. Even if the gel medium was Sephadex G-50, the upper column’s volume and eluent were not obtained. It may pertain to the way of purification and the quality of gel. Even so, the purified recombinant protein was achieved by ammonium sulfate salting out and ion-exchange chromatography. By and large, recombinant proteins secreted by

P. pastoris are released into the culture supernatant and are easily purified due to limited production of endogenous secretory proteins[

19]. This yeast system is convenient, it also has relatively rapid expression times, cotranslational and posttranslational processing, especially for large-scale industrialization.

For interferon therapeutic proteins to attain their complete biological activity, glycosylation must play an important role.

P. pastoris is capable of performing posttranslational modifications like both N- and O-linked glycosylation[

18]. From glycosylation sites prediction and glycoprotein staining, we could conclude that recombinant boIFN-λ3 was expressed in glycosylated and non-glycosylated forms, consistent with the literature reports[

20]. SDS-PAGE and western blot showed that it mainly expresses in glycosylated form. In the expression and purification of boIFN-λ3

V18M, the glycosylation protein was reduced. The glycosylated boIFN-λ3 has good water solubility and the purified boIFN-λ3 results in less non-glycosylation, better hydrophilicity, and higher yields. Although boIFN-λ3

V18M whose alteration site was not at the glycosylation site was purified, the non-specific bands were decreased and its level of glycosylation was higher, indicating better water solubility. This is consistent with our general consensus that N-linked glycosylation constitutes plays a pivotal role to its hydrodynamic volume in therapeutic proteins and therefore to its pharmacodynamics behavior, which further reflects even the change of the 18th amino acid affected its glycosylation level[

18]. Moreover, very little O-linked glycosylation has been observed in

P. pastoris[

19]. Inconsistent with the number of glycosylation site categories predicted by software (Putative: One N-gly; two O-gly). Interestingly, there was no difference in the good performance of the physicochemical properties and antiviral activity of boIFN-λ3/λ3

V18M. In future production practice, boIFN-λ3/λ3

V18M can be mixed and used together, which can achieve both increased yield and increased solubility as well as antiviral activity. To further explore the effect of glycosylation on boIFN-λ3, the subsequent work needs to use glycosidase decomposition to obtain a single protein for research.

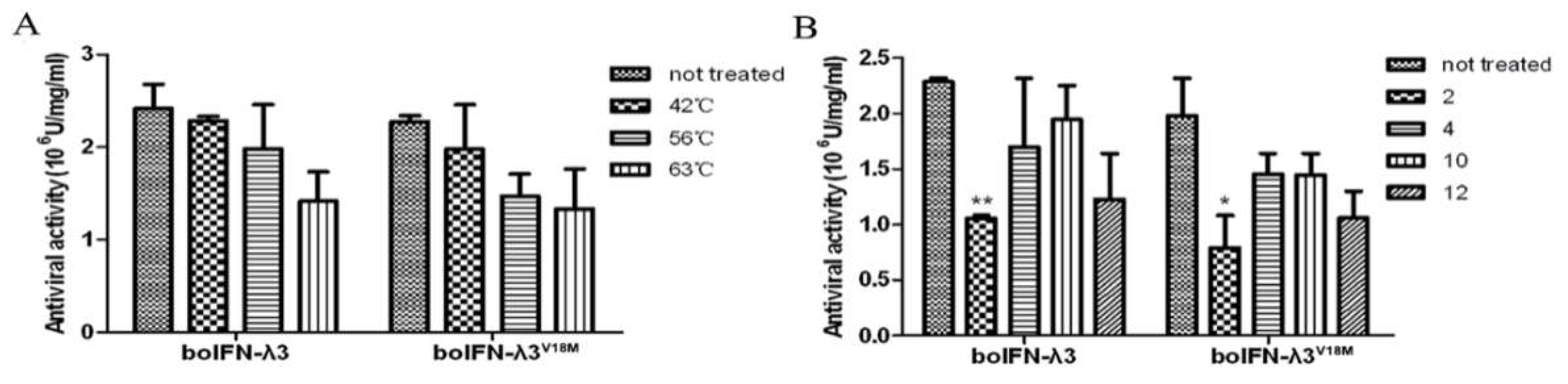

Physicochemical properties of recombinant boIFN-λ3 are neutralized by specific antibodies, heat-resistant, and acid and alkali-resistant[

8]. These properties are comparable to those of known type I interferon, confirming the functional similarity between IFN-λ and IFN-α[

21]. In this study, the effect of the 18th amino acid (V-M) change on the expression and activity of recombinant boIFN-λ3 was analyzed and showed that the difference of amino acid 18th of mature peptide did not affect the biological activity and physicochemical properties of recombinant boIFN-λ3. Gad’s research team found that each of the 16 amino acids exposed to IFN-λ3 at the helix A, D, F, and the corner of AB was mutated into alanine, which showed that the activity of the mutant was different after the mutation, 158th amino acid was the critical amino acid for its binding receptor, and it was inactivated after mutation[

22]. Therefore, 18th amino acid of the mature peptide is a dispensable amino acid for IFN-λ3 to play its role, which neither the structural characteristics of boIFN-λ3 nor hinders its antiviral activity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and M.G.; methodology, R.Z.; software, R.Z. and R.A.; validation, M.G., J.W. and Y.G.; formal analysis, R.Z. and R.A.; investigation, J.G.; resources, Y.G., M.G.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z. and R.A.; writing—review and editing, M.G., Y.G., R.Z., and R.A.; visualization, R.Z.; supervision, M.G. and Y.G.; project administration, Y.G. and M.G.; funding acquisition, Y.G. and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

The construction of pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3 by SOE with optimized codons.

Figure 1.

The construction of pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3 by SOE with optimized codons.

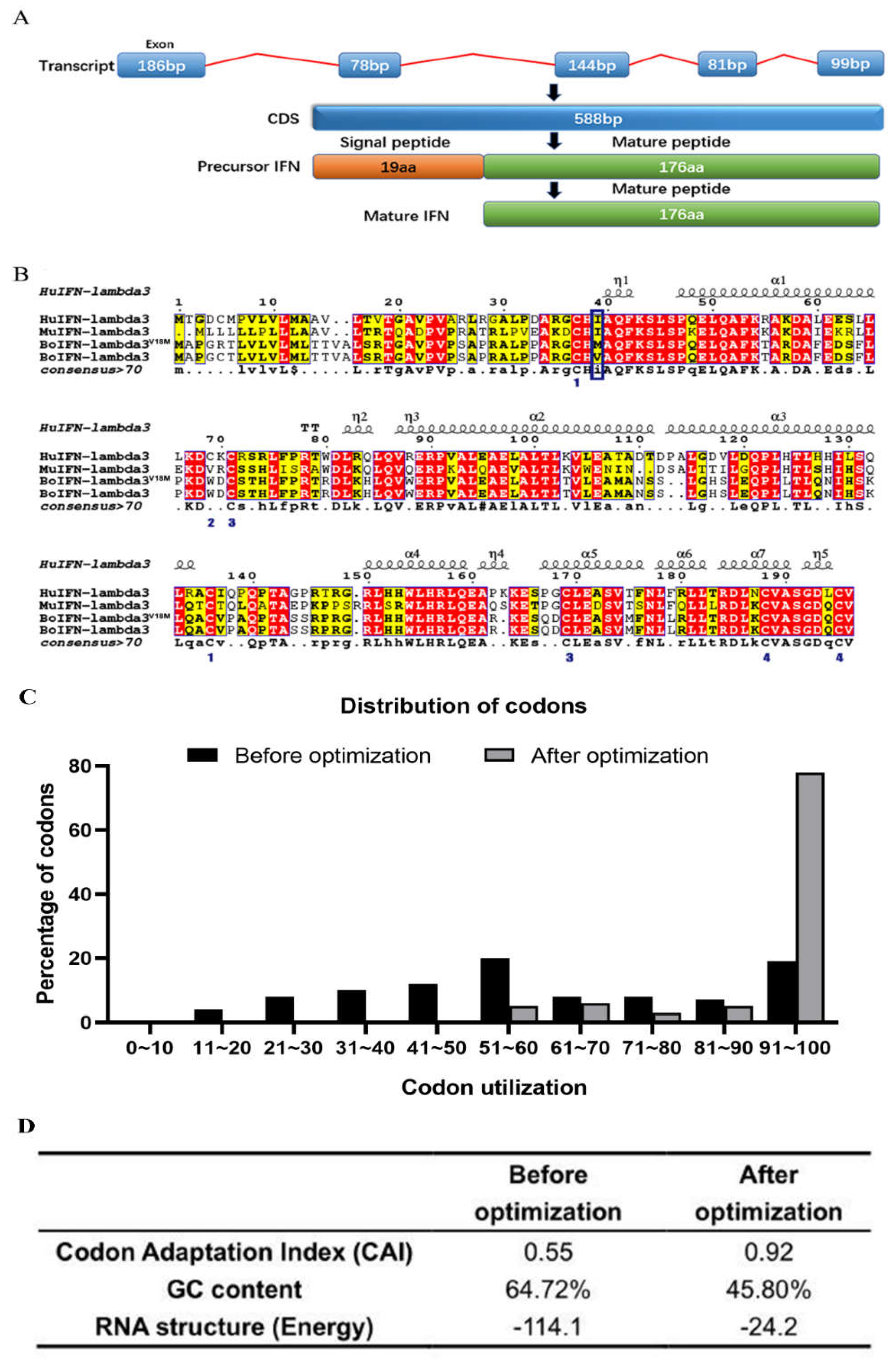

Figure 2.

Sequence alignment of codon-optimized boIFN-λ3V18M and original boIFN-λ3. (A). The translation process of IFN-λ3. (B). Sequence alignment of IFN-λ3. GenBank Accession: HuIFN-lambda3, NM_172139.2; MuIFN-lambda3, NM_177396.1; BoIFN-lambda3V18M, No. OQ565419; BoIFN-lambda3, No. OQ565418. (C). Optimization for codon usage rate of the bovine ifn-λ3 gene in P. pastoris. The percentage distribution of codons is computed in codon quality groups. The value of 100 is set for the codon with the highest usage frequency for a given amino acid in the desired expression organism. Codons with values lower than 30 are likely to hamper expression efficiency. (D). Comparison of the values of index optimization. The possibility of high protein expression level is correlated with the value of CAI (a CAI of 1.0 is considered to be ideal, whereas a CAI of > 0.8 is rated as good for the desired expression). The ideal percentage range of GC content is between 30% and 70%. Any peaks outside this range will adversely affect transcriptional and translational efficiency.

Figure 2.

Sequence alignment of codon-optimized boIFN-λ3V18M and original boIFN-λ3. (A). The translation process of IFN-λ3. (B). Sequence alignment of IFN-λ3. GenBank Accession: HuIFN-lambda3, NM_172139.2; MuIFN-lambda3, NM_177396.1; BoIFN-lambda3V18M, No. OQ565419; BoIFN-lambda3, No. OQ565418. (C). Optimization for codon usage rate of the bovine ifn-λ3 gene in P. pastoris. The percentage distribution of codons is computed in codon quality groups. The value of 100 is set for the codon with the highest usage frequency for a given amino acid in the desired expression organism. Codons with values lower than 30 are likely to hamper expression efficiency. (D). Comparison of the values of index optimization. The possibility of high protein expression level is correlated with the value of CAI (a CAI of 1.0 is considered to be ideal, whereas a CAI of > 0.8 is rated as good for the desired expression). The ideal percentage range of GC content is between 30% and 70%. Any peaks outside this range will adversely affect transcriptional and translational efficiency.

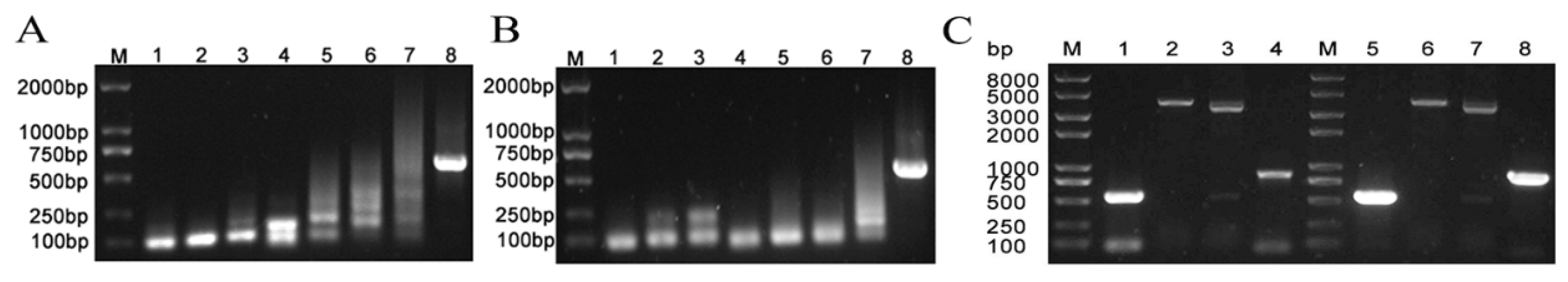

Figure 3.

Identification of boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M. (A) and (B). The boIFN-λ3 and the boIFN-λ3V18M SOE-PCR, respectively. M: Trans2K DNA Marker; 1~4, 5~6, 7 and 8 indicate the first, second, third and fourth PCR results, respectively. (C). The enzyme digestion and PCR identification of the P. pastoris transformants integrated into the boIFN-λ3 gene. M. Trans2K PlusII DNA Marker; 1 and 5. PCR Result based on P1/P14; 2 and 6. Xho I digested; 3 and 7 Xho I and Xba I digested; 4 and 8. PCR result based on 5′AOX/P14. 1~4 was the results of recombinant expression vector pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3 and 5~8 indicated the pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3V18M.

Figure 3.

Identification of boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M. (A) and (B). The boIFN-λ3 and the boIFN-λ3V18M SOE-PCR, respectively. M: Trans2K DNA Marker; 1~4, 5~6, 7 and 8 indicate the first, second, third and fourth PCR results, respectively. (C). The enzyme digestion and PCR identification of the P. pastoris transformants integrated into the boIFN-λ3 gene. M. Trans2K PlusII DNA Marker; 1 and 5. PCR Result based on P1/P14; 2 and 6. Xho I digested; 3 and 7 Xho I and Xba I digested; 4 and 8. PCR result based on 5′AOX/P14. 1~4 was the results of recombinant expression vector pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3 and 5~8 indicated the pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3V18M.

Figure 4.

Selection of high expressed recombinant GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 13 indicates the recombinant GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3, and NC indicates the GS115-pPICZαA. (A). Identification results of expressed recombinant GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3 by Western blot. (B). Results of supernatants of pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3 were identified by ELISA.

Figure 4.

Selection of high expressed recombinant GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 13 indicates the recombinant GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3, and NC indicates the GS115-pPICZαA. (A). Identification results of expressed recombinant GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3 by Western blot. (B). Results of supernatants of pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3 were identified by ELISA.

Figure 5.

Optimization of expression conditions of the recombinant boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M. (A, C) The SDS-PAGE analysis of different induction time of the recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M, respectively. (B, D). The protein weight analysis of different induction time of recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M, respectively. (E, F). The SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinant P. pastoris GS115 under different methanol concentrations. (E). GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3. (F). GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3V18M. M. Unstained protein molecular weight Marker; NC. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA.

Figure 5.

Optimization of expression conditions of the recombinant boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M. (A, C) The SDS-PAGE analysis of different induction time of the recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M, respectively. (B, D). The protein weight analysis of different induction time of recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M, respectively. (E, F). The SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinant P. pastoris GS115 under different methanol concentrations. (E). GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3. (F). GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3V18M. M. Unstained protein molecular weight Marker; NC. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA.

Figure 6.

Protein identification and glycoprotein analysis of recombinant boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M. (A). SDS-PAGE for recombinant boIFN-λ3 strains 5 and 13. M. Unstained protein molecular weight Marker, 1. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA, 2 and 3 is the induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3 strains 5 and 13, respectively. (B, C). Western blot analysis of Rabbit anti bovine IFN-λ3 polyclonal antibody (B) and Rabbit anti human IFN-λ3 polyclonal antibody (C) for immune response of recombinant boIFN-λ3. M. PageRuler Marker; 1. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA; 2,3. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3 strains 5 and 13, respectively. (D). SDS-PAGE for recombinant boIFN-λ3V18M strain 2. M. Unstained protein molecular weight Marker; 1. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3V18M strain 2. (E, F). Western blot analysis of Rabbit anti bovine IFN-λ3 polyclonal antibody (E) and Rabbit anti human IFN-λ3 polyclonal antibody (F) for immune response of recombinant boIFN-λ3V18M. M. PageRuler Marker; 1. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA; 2. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3V18M strain 2. (G). SDS-PAGE analysis of the purification of the recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M. (H). Glycoprotein staining the recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M.

Figure 6.

Protein identification and glycoprotein analysis of recombinant boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M. (A). SDS-PAGE for recombinant boIFN-λ3 strains 5 and 13. M. Unstained protein molecular weight Marker, 1. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA, 2 and 3 is the induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3 strains 5 and 13, respectively. (B, C). Western blot analysis of Rabbit anti bovine IFN-λ3 polyclonal antibody (B) and Rabbit anti human IFN-λ3 polyclonal antibody (C) for immune response of recombinant boIFN-λ3. M. PageRuler Marker; 1. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA; 2,3. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3 strains 5 and 13, respectively. (D). SDS-PAGE for recombinant boIFN-λ3V18M strain 2. M. Unstained protein molecular weight Marker; 1. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3V18M strain 2. (E, F). Western blot analysis of Rabbit anti bovine IFN-λ3 polyclonal antibody (E) and Rabbit anti human IFN-λ3 polyclonal antibody (F) for immune response of recombinant boIFN-λ3V18M. M. PageRuler Marker; 1. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA; 2. The induced protein of GS115-pPICZαA-boIFN-λ3V18M strain 2. (G). SDS-PAGE analysis of the purification of the recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M. (H). Glycoprotein staining the recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M.

Figure 7.

Antiviral activity analysis of the recombinant boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M (A) and Antibody neutralization test for the recombinant boIFN-λ3(B) and boIFN-λ3V18M(C).

Figure 7.

Antiviral activity analysis of the recombinant boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M (A) and Antibody neutralization test for the recombinant boIFN-λ3(B) and boIFN-λ3V18M(C).

Figure 8.

The characteristics of the recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M. (A). The results of the thermal stability test of the recombinant protein. (B). The acid and alkali resistance of the recombinant protein.

Figure 8.

The characteristics of the recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M. (A). The results of the thermal stability test of the recombinant protein. (B). The acid and alkali resistance of the recombinant protein.

Figure 9.

Antiproliferative analysis of boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M.

Figure 9.

Antiproliferative analysis of boIFN-λ3/λ3V18M.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides for synthesizing the boIFN-λ3 gene.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides for synthesizing the boIFN-λ3 gene.

| No. |

Oligonucleotide fragments (5′-3′) |

| P1 |

AGCTCTCGAGXhoⅠAAAAGAGTTCCAGTTCCATCTGCCCCAAGAGCTTTGCC |

| P2 |

AGACAAGGACTTAAATTGAGCCACGTGACAACCACGGGCTGGTGGCAAAGCTCTTGGGG |

| P2′ |

AGACAAGGACTTAAATTGAGCCATGTGACAACCACGGGCTGGTGGCAAAGCTCTTGGGG |

| P3 |

GCTCAATTTAAGTCCTTGTCTCCACAAGAATTGCAAGCCTTTAAGACTGCTAGAGACGC |

| P4 |

AGAACAGTCCCAGTCCTTTGGCAAGAAAGAGTCTTCGAAAGCGTCTCTAGCAGTCTTAA |

| P5 |

AAGGACTGGGACTGTTCTACTCACTTGTTCCCAAGAACTAGAGACTTGAAGCACTTGCA |

| P6 |

AGGCCAATTCAGCTTCCAAAGCAACAGGTCTTTCCCAAACTTGCAAGTGCTTCAAGTCT |

| P7 |

GGAAGCTGAATTGGCCTTGACTTTGACTGTTTTGGAAGCTATGGCTAACTCTTCTTTGG |

| P8 |

GTTTTGCAAAGTCAACAATGGCTGTTCCAAAGAGTGACCCAAAGAAGAGTTAGCCATAG |

| P9 |

CATTGTTGACTTTGCAAAACATCCACTCTAAGTTGCAAGCCTGTGTTCCAGCTCAACCA |

| P10 |

CAACCAGTGGTGCAATCTACCTCTAGGTCTGGAAGAGGCGGTTGGTTGAGCTGGAACAC |

| P11 |

AGATTGCACCACTGGTTGCACAGATTGCAAGAGGCTAGAAAGGAATCCCAAGACTGTTT |

| P12 |

AGTCAACAATCTCAACAAGTTGAACATAACAGAAGCCTCCAAACAGTCTTGGGATTCCT |

| P13 |

AACTTGTTGAGATTGTTGACTAGAGACTTGAAGTGTGTTGCTTCTGGTGACCAATGTGT |

| P14 |

GACTTCTAGAXbaⅠTTAAACACATTGGTCACCAGAAG |

Table 2.

The purification of the recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M.

Table 2.

The purification of the recombinant boIFN-λ3 and boIFN-λ3V18M.

| 100 mL volume |

Total protein(mg) |

Target protein(mg) |

Purity (%) |

| BoIFN-λ3 |

Ammonium sulfate precipitation |

180 |

152.1 |

84.5 |

| Ion exchange chromatography |

32 |

29.44 |

92 |

| BoIFN-λ3 V18M

|

Ammonium sulfate precipitation |

175 |

148.75 |

85 |

| Ion exchange chromatography |

34 |

31.45 |

92.5 |