Submitted:

17 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

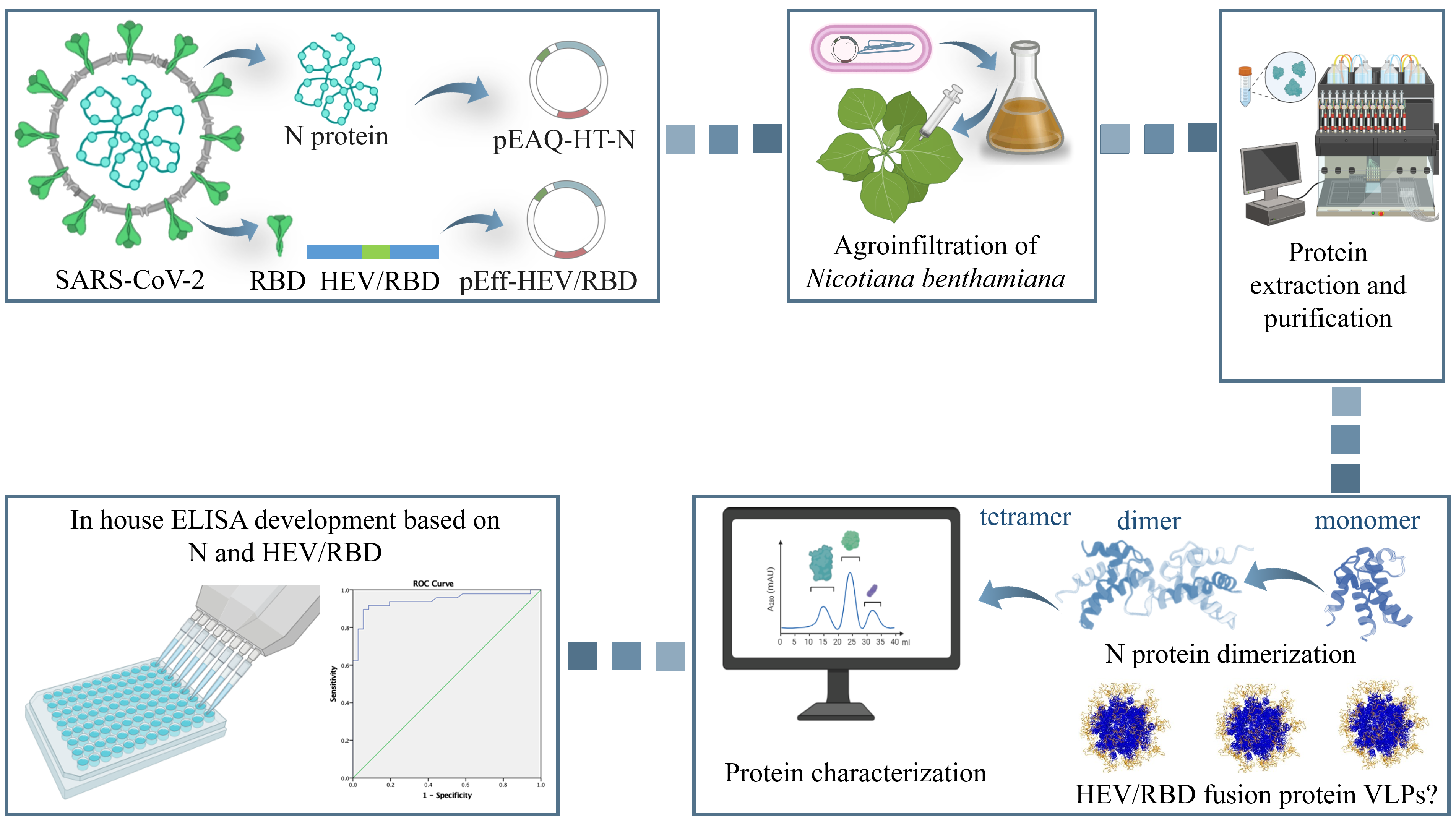

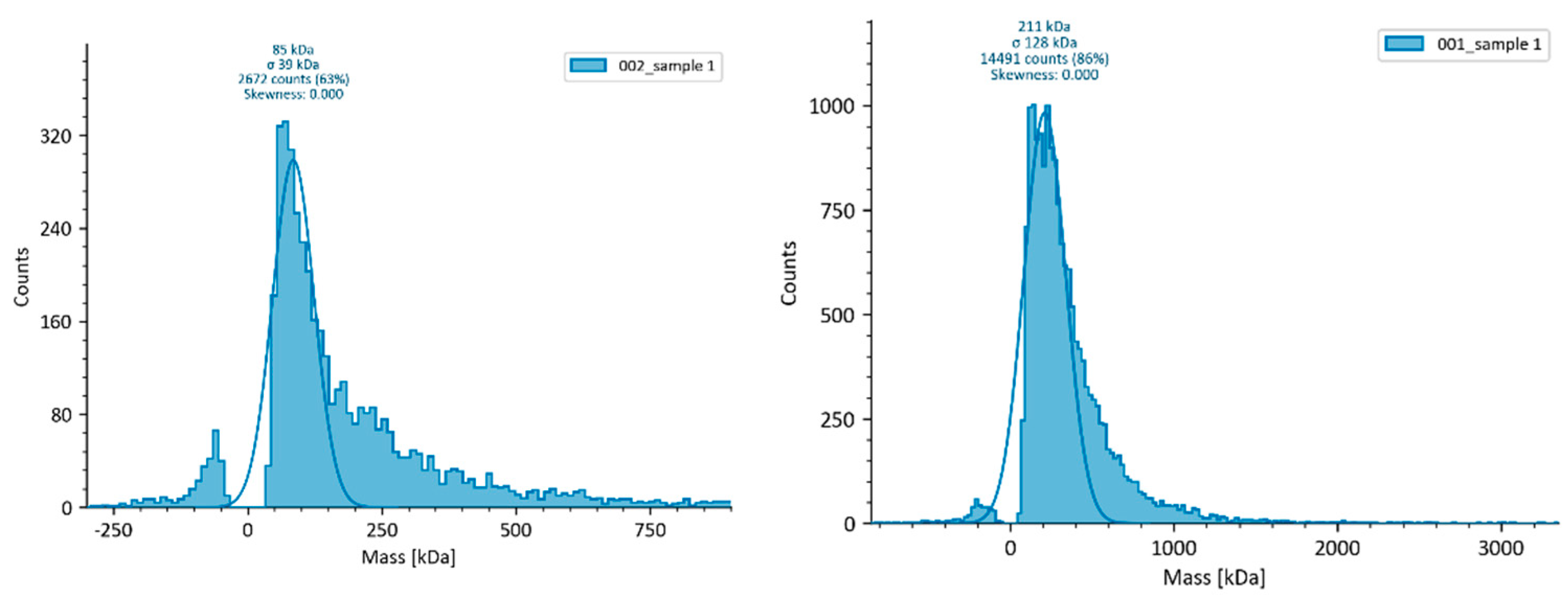

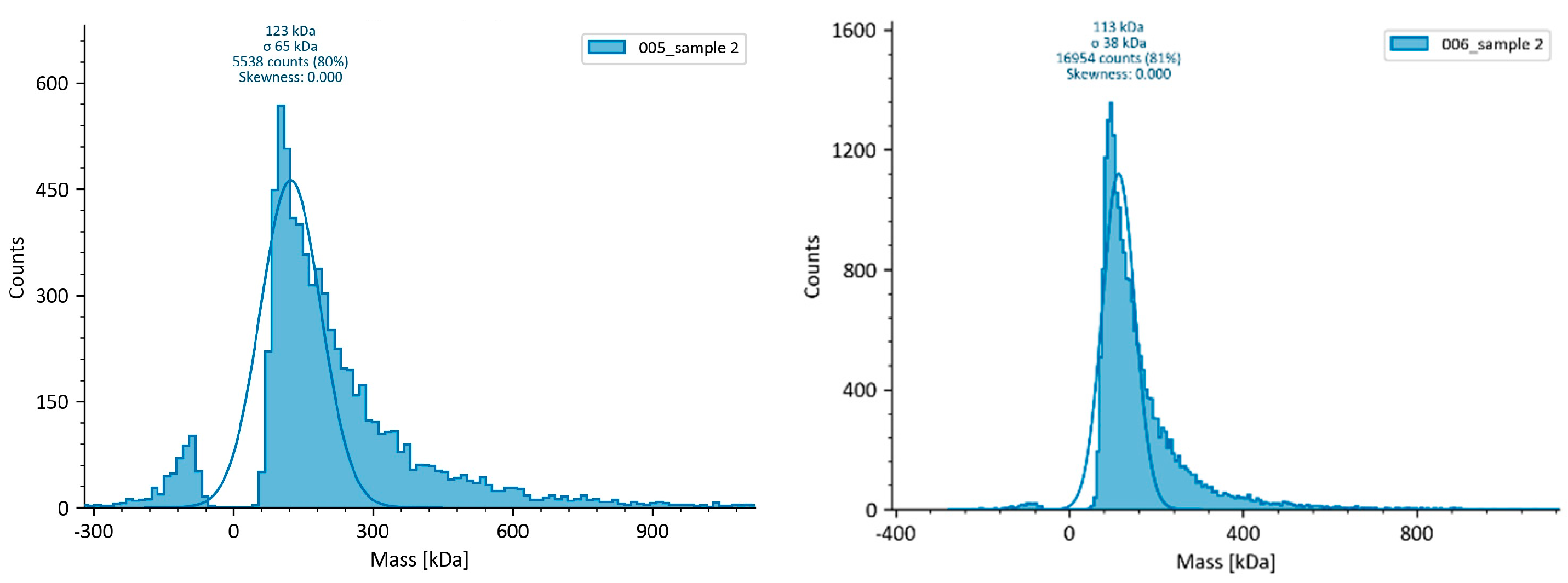

During the current severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, the rapid development of efficient and sensitive serological tests for monitoring the dynamics of the disease as well as the immune response after illness or vaccination was critical. In this regard, low-cost and fast production of immunogenic antigens is essential for the rapid development of diagnostic serological kits. This study assessed the plant-based production of nucleoprotein (N) of SARS-CoV-2 and chimeric receptor-binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 presented by hepatitis E virus capsid (HEV/RBD) and validation of the plant-derived proteins as diagnostic antigens for serological tests. The hepatitis E virus capsid protein was used as a carrier of RBD because of its ability to be expressed in plants in huge amounts and spontaneously assemble into higher order structures stabilizing inserted foreign immunogenic peptides. The N and chimeric HEV/RBD were expressed in and extracted from Nicotiana benthamiana plants and purified through immobilized metal-anion chromatography (IMAC). The resulting protein yield of chimeric HEV/RBD protein reached 100 mg/kg fresh weight, and 30 mg/kg fresh weight for N protein. Mass photometry analysis revealed that the N protein mainly forms tetramers, for HEV/RBD, results suggest that the fusion protein is largely monomeric. The purified N protein and HEV-RBD protein were used to develop an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (iELISA) for the detection of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in human sera. To validate the iELISA tests, a panel of 84 sera from patients diagnosed with COVID-19 was used, and the results were compared to those obtained by another commercially available ELISA Kit (Dia.Pro D. B., Italy). The performance of an HEV/RBD in-hose ELISA showed a sensitivity of 89.58% (95% Cl: 75.23-95.37) and a specificity of 94.44% (95% Cl: 76.94-98.2). Double Recognition iELISA based on HEV/RBD and N protein is characterized by a lower sensitivity of 85.42% (95% Cl: 72.24-93.93), and specificity of 94.44% (95% Cl: 81.34-99.32) at cut-off = 0.154, compared with iELISA based on HEV/RBD. Our study confirms that the transiently expressed in plants N and fusion HEV/RBD proteins can be used to detect responses to SARS-CoV-2 in human sera reliably. Our research validates the commercial potential of using plants as an expression system for recombinant protein production and their application as diagnostic reagents for serological detection of infectious diseases, hence lowering the cost of diagnostic kits.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

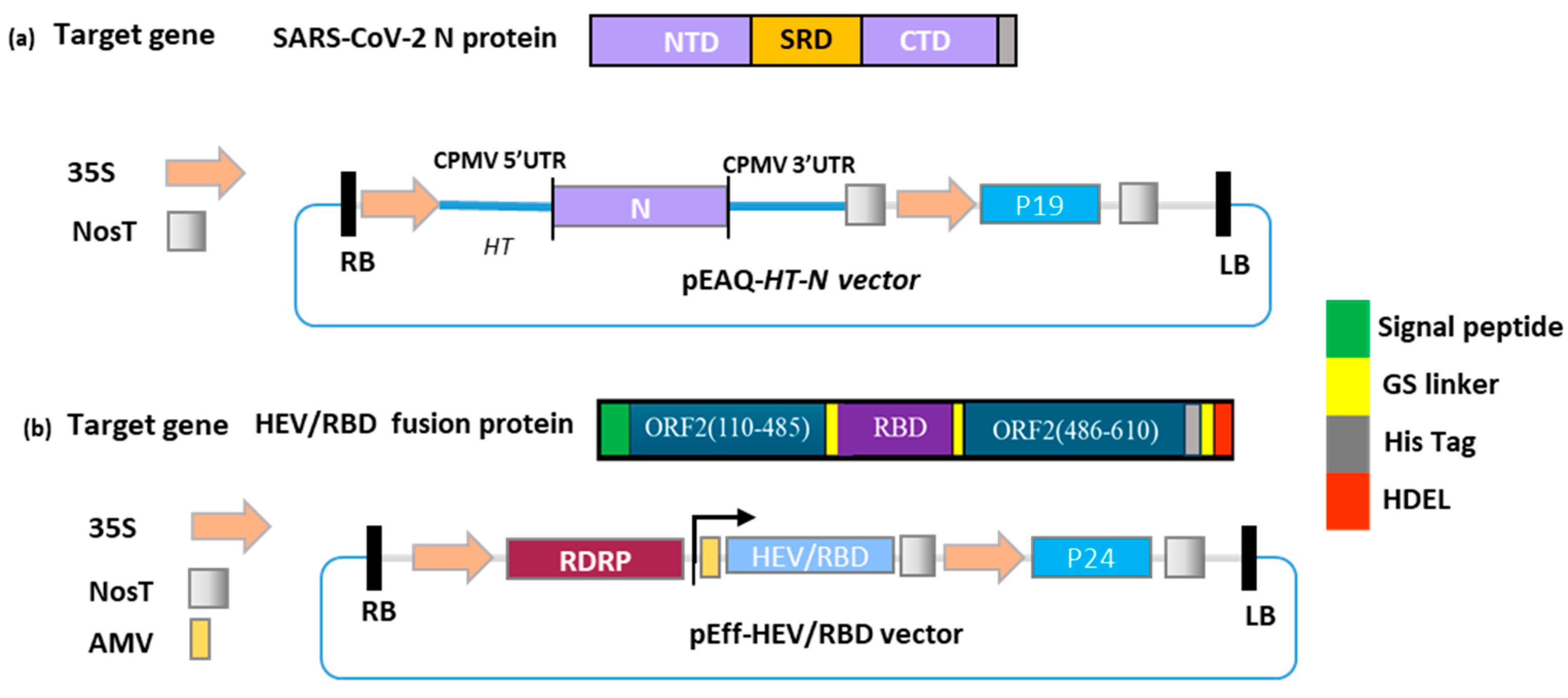

2.1. Gene preparation, Cloning of Nucleocapsid (N) in pEAQ-HT, and Agroinfiltration of Nicotiana benthamiana

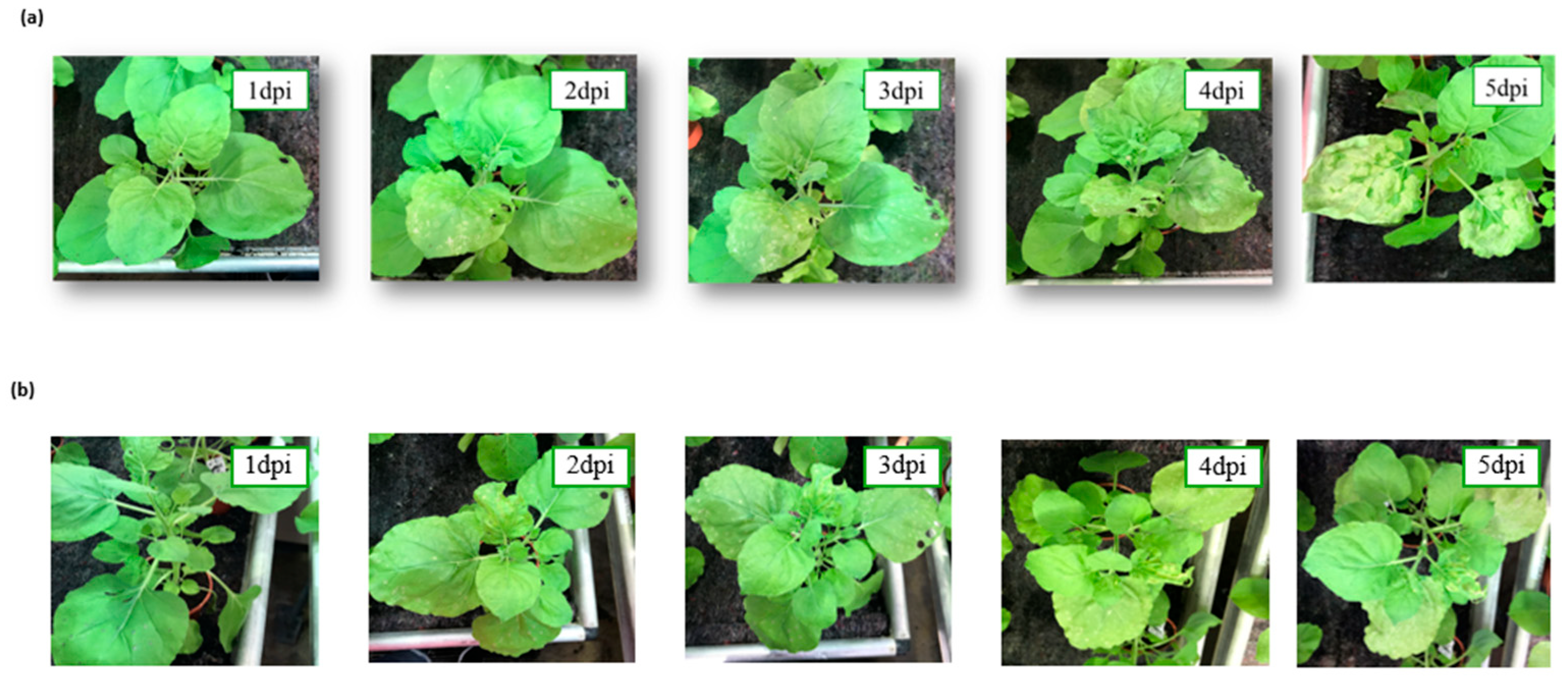

2.2. Transient Expression of N and HEV/RBD in Nicotiana benthamina

2.3. Purification of Plant-Produced N and HEV/RBD Using Affinity Chromatography

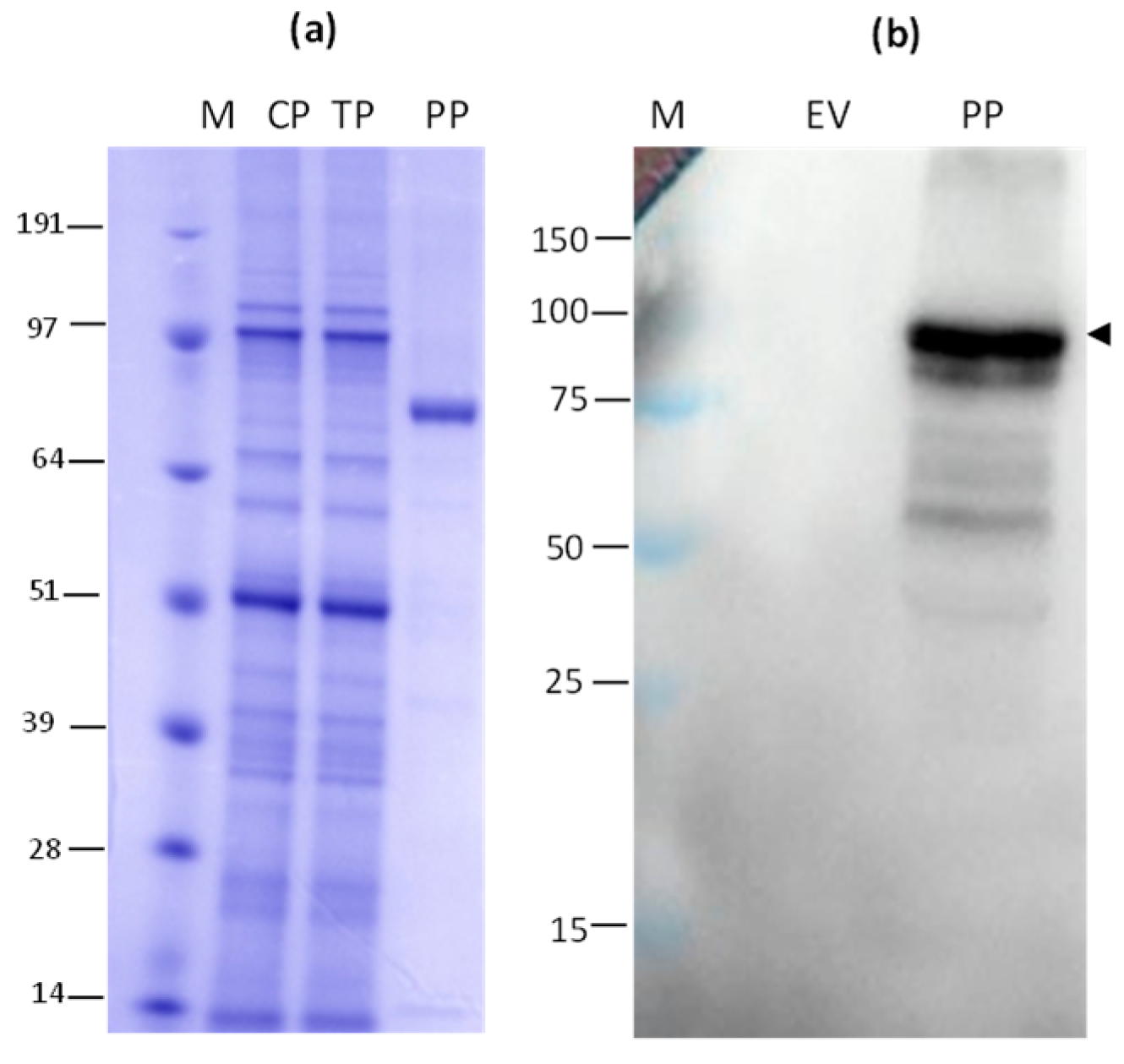

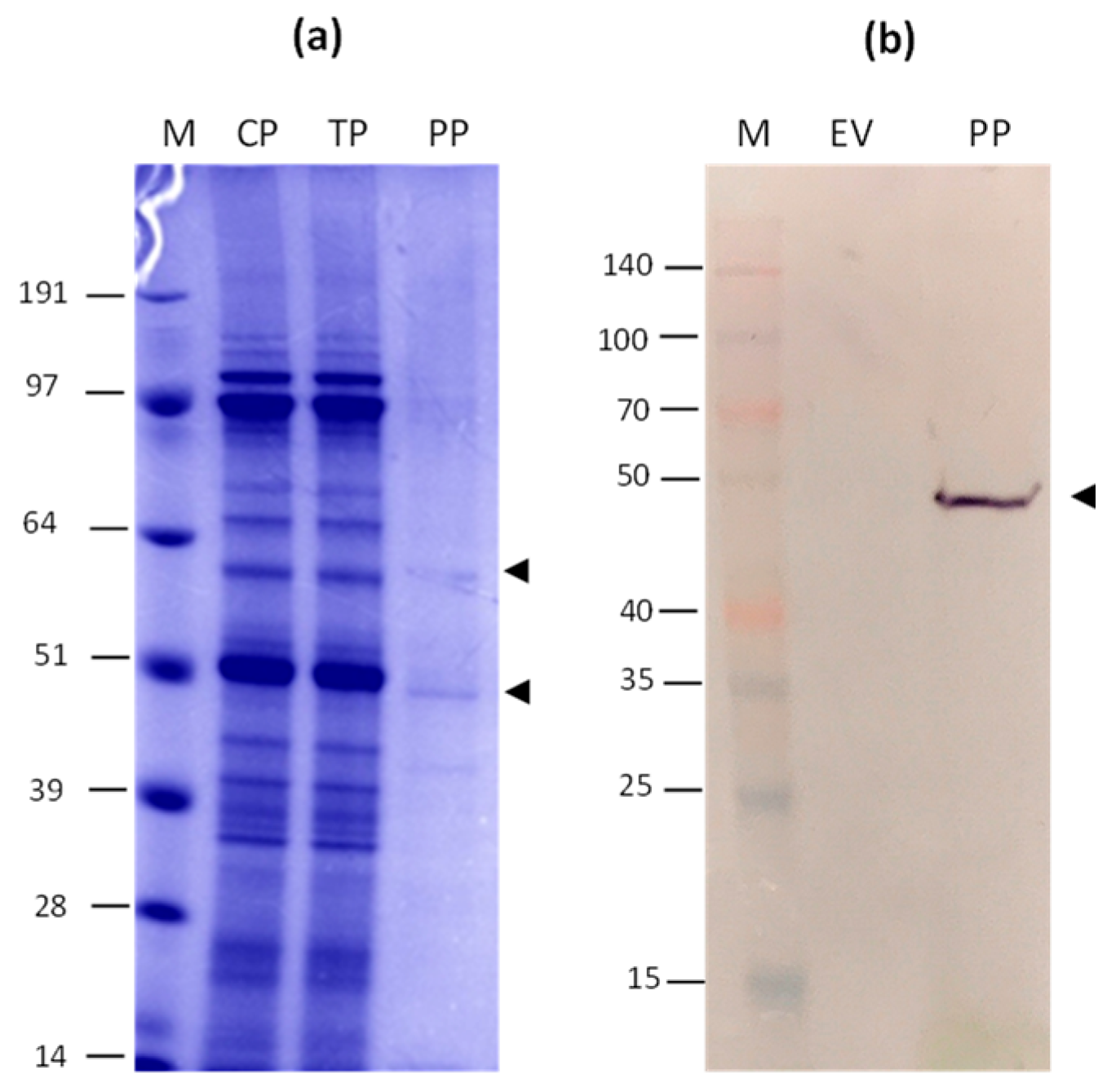

2.4. SDS-PAGE and Western Blot of Plant-Produced N and HEV/RBD

2.5. Mass Spectrometry

2.6. Mass Photometry of N and HEV/RBD

2.7. Serum Samples

2.8. Commercial Anti-Spike 1(RBD)/2 IgG ELISA Kit (Dia.Pro D. B., Italy)

2.9. Optimization of Indirect iELISA Protocol Based on HEV/RBD or N Recombinant Protein

2.10. Statistical Analysis, and Cut-off Evaluation of the iELISA

3. Results

3.1. Gene cloning, Production, and Purification of N and HEV/RBD Recombinant Proteins

3.2. Mass Spectrometry

3.3. Mass photometry (MP)

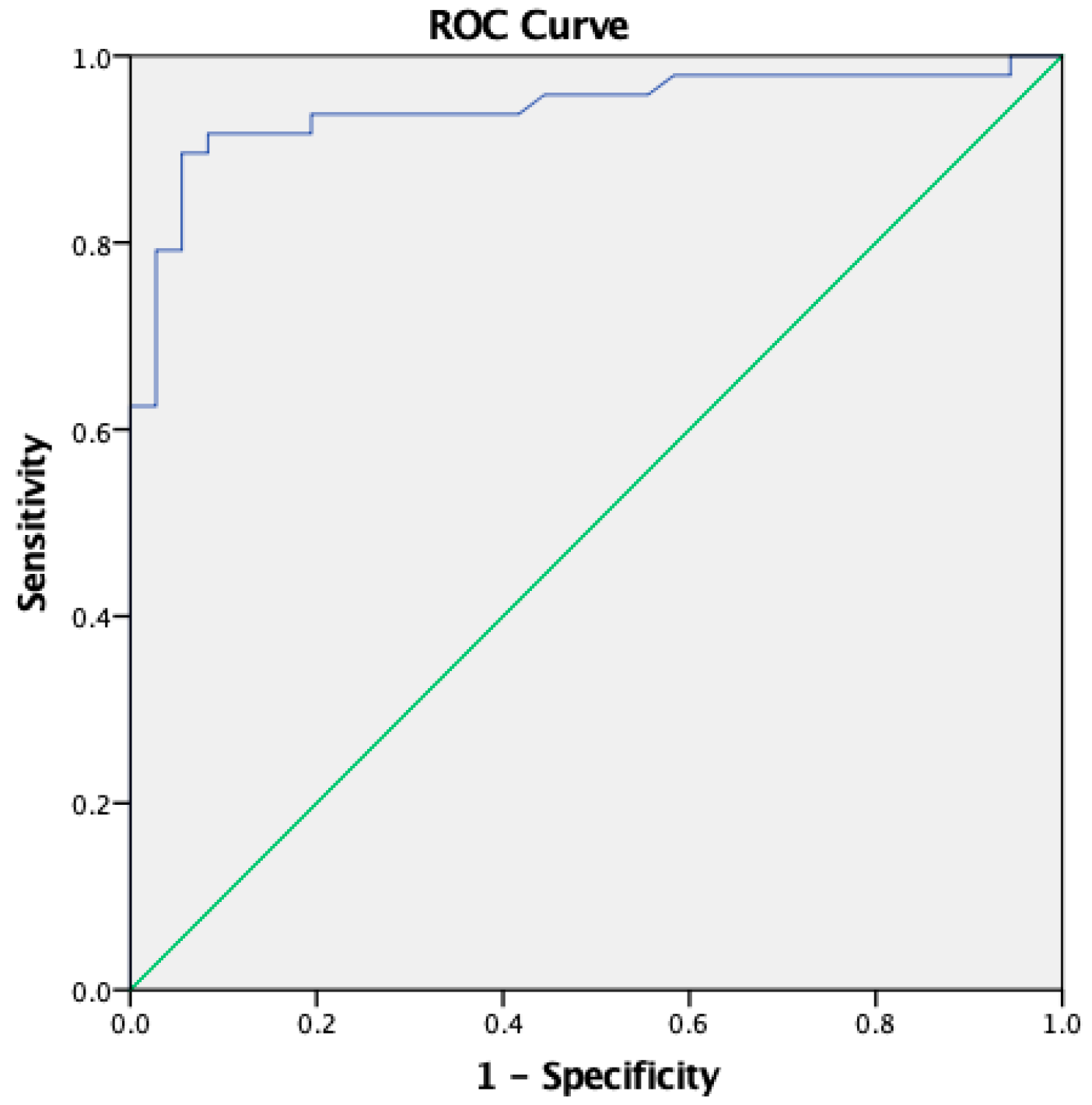

3.4. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC), Specificity, and Sensitivity of In-House ELISA with Plant-Derived HEV/RBD Protein

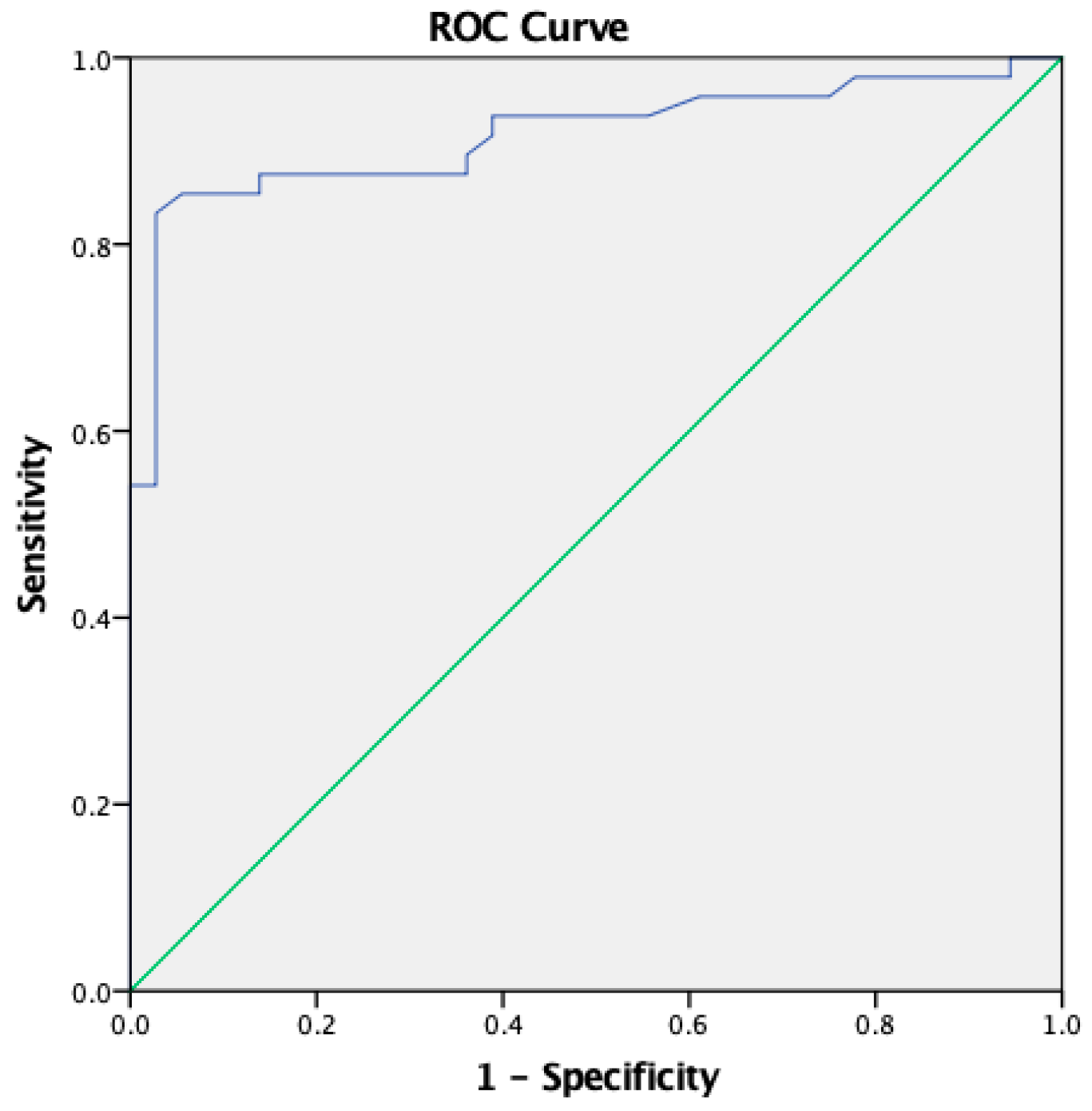

3.4. ROC, Specificity and Sensitivity of the In-House Double Recognition iELISA Based on HEV/RBD and N

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ws, K.; Jh, K.; J, L.; Sy, K.; Hd, C.; I, J.; St, J.; Jh, N. Functional Expression of the Recombinant Spike Receptor Binding Domain of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron in the Periplasm of Escherichia Coli. Bioengineering (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-H.; Pollet, J.; Strych, U.; Lee, J.; Liu, Z.; Kundu, R.T.; Versteeg, L.; Villar, M.J.; Adhikari, R.; Wei, J.; et al. Yeast-Expressed Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Receptor Binding Domain RBD203-N1 as a COVID-19 Protein Vaccine Candidate. Protein Expr Purif 2022, 190, 106003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaub, J.M.; Chou, C.-W.; Kuo, H.-C.; Javanmardi, K.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Goldsmith, J.; DiVenere, A.M.; Le, K.C.; Wrapp, D.; Byrne, P.O.; et al. Expression and Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Proteins. Nat Protoc 2021, 16, 5339–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarze, M.; Luo, J.; Brakel, A.; Krizsan, A.; Lakowa, N.; Grünewald, T.; Lehmann, C.; Wolf, J.; Borte, S.; Milkovska-Stamenova, S.; et al. Evaluation of S- and M-Proteins Expressed in Escherichia Coli and HEK Cells for Serological Detection of Antibodies in Response to SARS-CoV-2 Infections and mRNA-Based Vaccinations. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.-W.; Zahmanova, G.; Minkov, I.; Lomonossoff, G.P. Plant-Based Expression and Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 Virus-like Particles Presenting a Native Spike Protein. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2022, 20, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruocco, V.; Strasser, R. Transient Expression of Glycosylated SARS-CoV-2 Antigens in Nicotiana Benthamiana. Plants 2022, 11, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahmanova, G.; Takova, K.; Valkova, R.; Toneva, V.; Minkov, I.; Andonov, A.; Lukov, G.L. Plant-Derived Recombinant Vaccines against Zoonotic Viruses. Life (Basel) 2022, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, B.J.; Makarkov, A.; Séguin, A.; Pillet, S.; Trépanier, S.; Dhaliwall, J.; Libman, M.D.; Vesikari, T.; Landry, N. Efficacy, Immunogenicity, and Safety of a Plant-Derived, Quadrivalent, Virus-like Particle Influenza Vaccine in Adults (18–64 Years) and Older Adults (≥65 Years): Two Multicentre, Randomised Phase 3 Trials. The Lancet 2020, 396, 1491–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medicago and GSK Announce the Approval by Health Canada of COVIFENZ, an Adjuvanted Plant-Based COVID-19 Vaccine. Available online: https://www.biopharminternational.com/view/medicago-and-gsk-announce-the-approval-by-health-canada-of-covifenz-an-adjuvanted-plant-based-covid-19-vaccine (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Mardanova, E.S.; Takova, K.H.; Toneva, V.T.; Zahmanova, G.G.; Tsybalova, L.M.; Ravin, N.V. A Plant-Based Transient Expression System for the Rapid Production of Highly Immunogenic Hepatitis E Virus-like Particles. Biotechnol Lett 2020, 42, 2441–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahmanova, G.; Aljabali, A.A.; Takova, K.; Toneva, V.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Andonov, A.P.; Lukov, G.L.; Minkov, I. The Plant Viruses and Molecular Farming: How Beneficial They Might Be for Human and Animal Health? Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.; Buyel, J.F. Molecular Farming - The Slope of Enlightenment. Biotechnol Adv 2020, 40, 107519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyel, J.F.; Twyman, R.M.; Fischer, R. Extraction and Downstream Processing of Plant-Derived Recombinant Proteins. Biotechnol Adv 2015, 33, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahmanova, G.; Aljabali, A.A.A.; Takova, K.; Minkov, G.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Minkov, I.; Lomonossoff, G.P. Green Biologics: Harnessing the Power of Plants to Produce Pharmaceuticals. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 17575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elelyso®|Protalix. Available online: https://protalix.com/products/elelyso (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- iBio Reports Successful Preclinical Immunization Studies with Next-Gen Nucleocapsid COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate. Available online: https://ir.ibioinc.com/news-events/press-releases/detail/163/ibio-reports-successful-preclinical-immunization-studies (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Starkevič, U.; Bortesi, L.; Virgailis, M.; Ružauskas, M.; Giritch, A.; Ražanskienė, A. High-Yield Production of a Functional Bacteriophage Lysin with Antipneumococcal Activity Using a Plant Virus-Based Expression System. J Biotechnol 2015, 200, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ac, W.; Yj, P.; Ma, T.; A, W.; At, M.; D, V. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.; Drosten, C.; Müller, M.A. Serological Assays for Emerging Coronaviruses: Challenges and Pitfalls. Virus Res 2014, 194, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-Y.; Zhao, R.; Gao, L.-J.; Gao, X.-F.; Wang, D.-P.; Cao, J.-M. SARS-CoV-2: Structure, Biology, and Structure-Based Therapeutics Development. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 587269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Ye, G.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Cell Entry Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 11727–11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Ulasli, M.; Schepers, H.; Mauthe, M.; V’kovski, P.; Kriegenburg, F.; Thiel, V.; de Haan, C.A.M.; Reggiori, F. Nucleocapsid Protein Recruitment to Replication-Transcription Complexes Plays a Crucial Role in Coronaviral Life Cycle. J Virol 2020, 94, e01925-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Chen, C.-M.M.; Chiang, M.; Hsu, Y.; Huang, T. Transient Oligomerization of the SARS-CoV N Protein – Implication for Virus Ribonucleoprotein Packaging. PLoS One 2013, 8, e65045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Yang, M.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Z.; Chen, X.; He, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Q.; et al. Crystal Structure of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein RNA Binding Domain Reveals Potential Unique Drug Targeting Sites. Acta Pharm Sin B 2020, 10, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilocca, B.; Soggiu, A.; Sanguinetti, M.; Musella, V.; Britti, D.; Bonizzi, L.; Urbani, A.; Roncada, P. Comparative Computational Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein Epitopes in Taxonomically Related Coronaviruses. Microbes Infect 2020, 22, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A Pneumonia Outbreak Associated with a New Coronavirus of Probable Bat Origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, H.; Sun, C.; Zhang, S. The SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein: Its Role in the Viral Life Cycle, Structure and Functions, and Use as a Potential Target in the Development of Vaccines and Diagnostics. Virol J 2023, 20, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockstroh, A.; Wolf, J.; Fertey, J.; Kalbitz, S.; Schroth, S.; Lübbert, C.; Ulbert, S.; Borte, S. Correlation of Humoral Immune Responses to Different SARS-CoV-2 Antigens with Virus Neutralizing Antibodies and Symptomatic Severity in a German COVID-19 Cohort. Emerg Microbes Infect 2021, 10, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atyeo, C.; Fischinger, S.; Zohar, T.; Slein, M.D.; Burke, J.; Loos, C.; McCulloch, D.J.; Newman, K.L.; Wolf, C.; Yu, J.; et al. Distinct Early Serological Signatures Track with SARS-CoV-2 Survival. Immunity 2020, 53, 524–532.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infantino, M.; Damiani, A.; Gobbi, F.L.; Grossi, V.; Lari, B.; Macchia, D.; Casprini, P.; Veneziani, F.; Villalta, D.; Bizzaro, N.; et al. Serological Assays for SARS-CoV-2 Infectious Disease: Benefits, Limitations and Perspectives. Isr Med Assoc J 2020, 22, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Mamedov, T.; Yuksel, D.; Gurbuzaslan, I.; Ilgin, M.; Gulec, B.; Mammadova, G.; Ozdarendeli, A.; Pavel, S.T.I.; Yetiskin, H.; Kaplan, B.; et al. Plant-Produced RBD and Cocktail-Based Vaccine Candidates Are Highly Effective against SARS-CoV-2, Independently of Its Emerging Variants. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1202570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamedov, T.; Yuksel, D.; Ilgın, M.; Gürbüzaslan, I.; Gulec, B.; Mammadova, G.; Ozdarendeli, A.; Yetiskin, H.; Kaplan, B.; Islam Pavel, S.T.; et al. Production and Characterization of Nucleocapsid and RBD Cocktail Antigens of SARS-CoV-2 in Nicotiana Benthamiana Plant as a Vaccine Candidate against COVID-19. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoni, M.; Gutierrez-Valdes, N.; Pivotto, D.; Zanichelli, E.; Rosa, A.; Sobrino-Mengual, G.; Balieu, J.; Lerouge, P.; Bardor, M.; Cecchetto, R.; et al. Performance of Plant-Produced RBDs as SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostic Reagents: A Tale of Two Plant Platforms. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1325162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardanova, E.S.; Kotlyarov, R.Y.; Stuchinskaya, M.D.; Nikolaeva, L.I.; Zahmanova, G.; Ravin, N.V. High-Yield Production of Chimeric Hepatitis E Virus-Like Particles Bearing the M2e Influenza Epitope and Receptor Binding Domain of SARS-CoV-2 in Plants Using Viral Vectors. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 15684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahmanova, G.G.; Mazalovska, M.; Takova, K.H.; Toneva, V.T.; Minkov, I.N.; Mardanova, E.S.; Ravin, N.V.; Lomonossoff, G.P. Rapid High-Yield Transient Expression of Swine Hepatitis E ORF2 Capsid Proteins in Nicotiana Benthamiana Plants and Production of Chimeric Hepatitis E Virus-Like Particles Bearing the M2e Influenza Epitope. Plants (Basel) 2019, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardanova, E.S.; Vasyagin, E.A.; Kotova, K.G.; Zahmanova, G.G.; Ravin, N.V. Plant-Produced Chimeric Hepatitis E Virus-like Particles as Carriers for Antigen Presentation. Viruses 2024, 16, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, H.; Maldonado-Agurto, R.; Dickson, A.J. The Endoplasmic Reticulum and Unfolded Protein Response in the Control of Mammalian Recombinant Protein Production. Biotechnol Lett 2014, 36, 1581–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitman, J.D.; Hiatt, J.; Mowery, C.T.; Shy, B.R.; Yu, R.; Yamamoto, T.N.; Rathore, U.; Goldgof, G.M.; Whitty, C.; Woo, J.M.; et al. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 Serology Assays Reveals a Range of Test Performance. Nat Biotechnol 2020, 38, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tré-Hardy, M.; Wilmet, A.; Beukinga, I.; Favresse, J.; Dogné, J.-M.; Douxfils, J.; Blairon, L. Analytical and Clinical Validation of an ELISA for Specific SARS-CoV-2 IgG, IgA, and IgM Antibodies. J Med Virol 2021, 93, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainsbury, F.; Thuenemann, E.C.; Lomonossoff, G.P. pEAQ: Versatile Expression Vectors for Easy and Quick Transient Expression of Heterologous Proteins in Plants. Plant Biotechnol J 2009, 7, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Nguyen, A.; Wu, D.; Li, Y.; Hassan, S.A.; Chen, J.; Shroff, H.; Piszczek, G.; Schuck, P. Plasticity in Structure and Assembly of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein. bioRxiv 2022, 2022.02.08.479556. [CrossRef]

- Abebe, E.C.; Dejenie, T.A. Protective Roles and Protective Mechanisms of Neutralizing Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Their Potential Clinical Implications. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1055457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Gao, Y.; Liu, X.; Nie, Z.; Sun, H.; Lin, K.; Peng, H.; Wang, S. Identification and Functional Analysis of the SARS-COV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein. BMC Microbiol 2021, 21, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, B.; Zhang, Q.; Ge, J.; Wang, R.; Sun, J.; Ge, X.; Yu, J.; Shan, S.; Zhou, B.; Song, S.; et al. Human Neutralizing Antibodies Elicited by SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Nature 2020, 584, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesov, D.E.; Sinegubova, M.V.; Dayanova, L.K.; Dolzhikova, I.V.; Vorobiev, I.I.; Orlova, N.A. Fast and Accurate Surrogate Virus Neutralization Test Based on Antibody-Mediated Blocking of the Interaction of ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein RBD. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, T.; Geppert, J.; Dinnes, J.; Scandrett, K.; Bigio, J.; Sulis, G.; Hettiarachchi, D.; Mathangasinghe, Y.; Weeratunga, P.; Wickramasinghe, D.; et al. Antibody Tests for Identification of Current and Past Infection with SARS-CoV-2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022, 11, CD013652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, K.-A.; Osorio, F.A.; Hiscox, J.A. Recombinant Viral Proteins for Use in Diagnostic ELISAs to Detect Virus Infection. Vaccine 2007, 25, 5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Li, G.; Ren, X.; Herrler, G. Select What You Need: A Comparative Evaluation of the Advantages and Limitations of Frequently Used Expression Systems for Foreign Genes. J Biotechnol 2007, 127, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.; Jurado, S.; Llorente, F.; Romualdo, A.; González, S.; Saconne, A.; Bronchalo, I.; Martínez-Cortes, M.; Pérez-Gómez, B.; Ponz, F.; et al. The C-Terminal Half of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein, Industrially Produced in Plants, Is Valid as Antigen in COVID-19 Serological Tests. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 699665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazalovska, M.; Varadinov, N.; Koynarski, T.; Minkov, I.; Teoharov, P.; Lomonossoff, G.P.; Zahmanova, G. Detection of Serum Antibodies to Hepatitis E Virus Based on HEV Genotype 3 ORF2 Capsid Protein Expressed in Nicotiana Benthamiana. Annals of Laboratory Medicine 2017, 37, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takova, K.; Koynarski, T.; Minkov, G.; Toneva, V.; Mardanova, E.; Ravin, N.; Lukov, G.L.; Zahmanova, G. Development and Optimization of an Enzyme Immunoassay to Detect Serum Antibodies against the Hepatitis E Virus in Pigs, Using Plant-Derived ORF2 Recombinant Protein. Vaccines 2021, 9, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet, M.-C.; Gaudreau, L.; Gagné, M.; Maltais, A.-M.; Laliberté, A.-C.; Éthier, G.; Bechtold, N.; Martel, M.; D’Aoust, M.-A.; Gosselin, A.; et al. Production of Biopharmaceuticals in Nicotiana Benthamiana—Axillary Stem Growth as a Key Determinant of Total Protein Yield. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyret, H.; Steele, J.F.C.; Jung, J.-W.; Thuenemann, E.C.; Meshcheriakova, Y.; Lomonossoff, G.P. Producing Vaccines against Enveloped Viruses in Plants: Making the Impossible, Difficult. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilho, A.; Schwestka, J.; Kienzl, N.F.; Vavra, U.; Grünwald-Gruber, C.; Izadi, S.; Hiremath, C.; Niederhöfer, J.; Laurent, E.; Monteil, V.; et al. Generation of Enzymatically Competent SARS-CoV-2 Decoy Receptor ACE2-Fc in Glycoengineered Nicotiana Benthamiana. Biotechnology Journal 2021, 16, 2000566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchol Tarazona, A.A.; Maresch, D.; Grill, A.; Bakalarz, J.; Torres Acosta, J.A.; Castilho, A.; Steinkellner, H.; Mach, L. Identification of Two Subtilisin-like Serine Proteases Engaged in the Degradation of Recombinant Proteins in Nicotiana Benthamiana. FEBS Lett 2021, 595, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shajahan, A.; Pepi, L.E.; Rouhani, D.S.; Heiss, C.; Azadi, P. Glycosylation of SARS-CoV-2: Structural and Functional Insights. Anal Bioanal Chem 2021, 7179–7193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, Y.; Berndsen, Z.T.; Raghwani, J.; Seabright, G.E.; Allen, J.D.; Pybus, O.G.; McLellan, J.S.; Wilson, I.A.; Bowden, T.A.; Ward, A.B.; et al. Vulnerabilities in Coronavirus Glycan Shields despite Extensive Glycosylation. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capell, T.; Twyman, R.M.; Armario-Najera, V.; Ma, J.K.-C.; Schillberg, S.; Christou, P. Potential Applications of Plant Biotechnology against SARS-CoV-2. Trends Plant Sci 2020, 25, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez-Ipiña, A.R.; González-González, E.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, I.P.; Lara-Mayorga, I.M.; Mejía-Manzano, L.A.; Sánchez-Salazar, M.G.; González-Valdez, J.G.; Ortiz-López, R.; Rojas-Martínez, A.; Trujillo-de Santiago, G.; et al. Serological Test to Determine Exposure to SARS-CoV-2: ELISA Based on the Receptor-Binding Domain of the Spike Protein (S-RBDN318-V510) Expressed in Escherichia Coli. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, W.H.; Khan, N.; Mishra, A.; Gupta, S.; Bansode, V.; Mehta, D.; Bhambure, R.; Ansari, M.A.; Das, S.; Rathore, A.S. Dimerization of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein Affects Sensitivity of ELISA Based Diagnostics of COVID-19. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 200, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdjieva, I.; Terziyski, I.; Zahmanova, G.; Simeonova, V.; Kulev, O.; Krastev, E.; Krachunov, M.; Nisheva-Pavlova, M.; Vassilev, D. HOMOLOGY BASED COMPUTATIONAL MODELLING OF HEPATITIS-E VIRAL FUSION CAPSID PROTEIN. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Long, Q.-X.; Liu, B.-Z.; Deng, H.-J.; Wu, G.-C.; Deng, K.; Chen, Y.-K.; Liao, P.; Qiu, J.-F.; Lin, Y.; Cai, X.-F.; et al. Antibody Responses to SARS-CoV-2 in Patients with COVID-19. Nat Med 2020, 26, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgenlander, W.R.; Henson, S.N.; Monaco, D.R.; Chen, A.; Littlefield, K.; Bloch, E.M.; Fujimura, E.; Ruczinski, I.; Crowley, A.R.; Natarajan, H.; et al. Antibody Responses to Endemic Coronaviruses Modulate COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma Functionality. J Clin Invest 2021, 131, e146927–146927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahmanova, G.; Takova, K.; Tonova, V.; Koynarski, T.; Lukov, L.L.; Minkov, I.; Pishmisheva, M.; Kotsev, S.; Tsachev, I.; Baymakova, M.; et al. The Re-Emergence of Hepatitis E Virus in Europe and Vaccine Development. Viruses 2023, 15, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharjan, P.M.; Cheon, J.; Jung, J.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Song, M.; Jeong, G.U.; Kwon, Y.; Shim, B.; Choe, S. Plant-Expressed Receptor Binding Domain of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Elicits Humoral Immunity in Mice. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean negative OD + 3SD | ROC curve | |

| Cut off | 0.139 | 0.175 |

| True Positive | 45/48 | 43/48 |

| True Negative | 29/36 | 34/36 |

| Sensitivity | 93.75% [82.8-98.69] | 89.58% [77.34-96.53] |

| Specificity | 80.56% [63.98-91.81] | 94.44% [81.34-99.32] |

| Accuracy | 88.10% [79.19-94.14] | 91.67% [83.58-96.58] |

| Positive Predictive Value | 86.54% [76.71-92.62] | 95.56% [84.78-98.81] |

| Negative Predictive Value | 90.62% [76.16-96.69] | 87.18% [74.72-93.99] |

| Commercial EIA | ||||

| iELISA | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 43 | 2 | 45 | |

| Negative | 5 | 34 | 39 | |

| Total | 48 | 36 | 84 | |

| Kappa index | 0.8316 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).