1. Introduction

Plants are successfully used as 'biofactories' for the production of complex proteins able to exert therapeutic functions (growth regulators, antibodies, vaccines, hormones, cytokines and enzymes) or to be used for diagnostic purposes, also thanks to their ability to carry out post-translational modifications that are often fundamental for maintaining protein functions [

1]. This area of plant biotechnology called “Plant Molecular Farming” (PMF) is an innovative and advantageous biopharmaceuticals production strategy that promises to reduce production’s costs, and increase its speed and biosafety [

2,

3].

In recent years, the huge demand for diagnostic kits during SARS-CoV-2 pandemics, followed by a severe shortage of reagents (recombinant antigens and antibodies), has highlighted the need for alternative platforms for biopharmaceutical production [

4]. Thus, there is a great interest, both by scientific community and biopharmaceutic industries, in understanding if PMF can be effective in clinical practice and, consequently, used for large-scale reagents’ production.

Indeed, PMF has emerged as a potentially effective strategy since it has already proven to be ideal for the production of SARS-CoV-1 virus antigens [

5], and in the recent SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, numerous studies have been carried out showing the successful production of recombinant antigens in plants, not only for vaccines production but also for diagnostic use [

6,

7].

The diagnostic tests currently available for SARS-CoV-2 detection are of various types and can be based on the use of recombinant antigens or of monoclonal antibodies. As for the former, these are called antibody tests and are able to detect the presence and concentration of IgM and IgG levels in blood, serum or plasma samples to determine whether the tested subject has come into contact with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. For these tests, recombinant antigens are used that simulate the presence of the virus and to which any antibody present in the sample binds [

8]. Even if these tests are effective, their production often requires long time and high costs. The development of alternative strategies for high-quality and low-costs reagents’ production has become an important issue, also to be able to respond promptly to new possible health emergencies.

Here, we report the use of plant produced recombinant antigens for diagnostic purposes. In particular, we tested the receptor-binding domain (RBD)w-Fc antigen of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein [

9] and used it to set-up an antigen-based assay able to screen vaccinated or infected sera samples. The results reported herein not only show that the proposed strategy is effective for SARS-CoV-2 rapid and cost-effective screening, but also provide an affordable methodology that can be easily transferred to other diseases, thus improving large-scale production of high-quality reagents.

2. Results

2.1. Plant Production of RBDw-Fc Recombinant Antigen

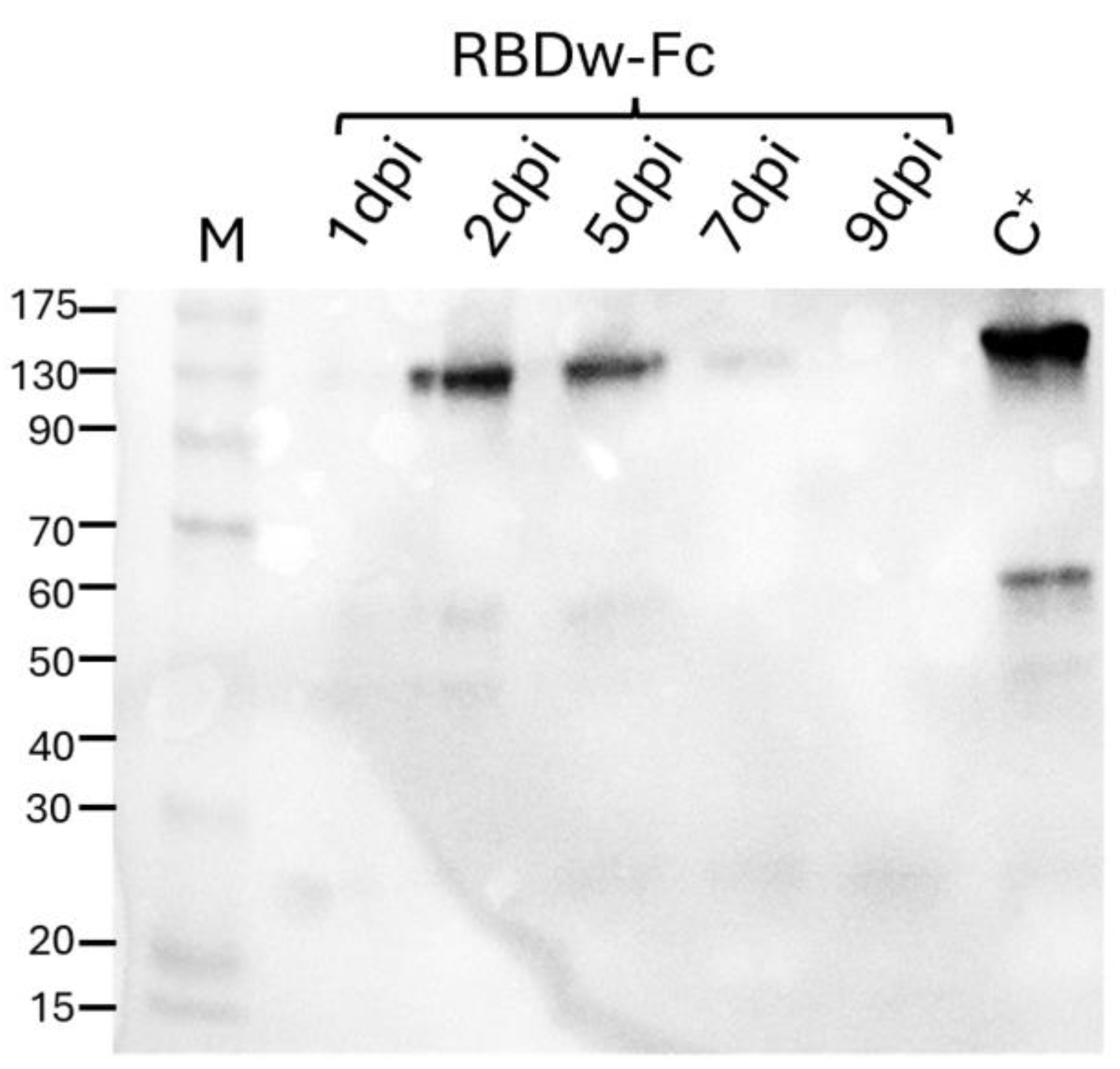

N. benthamiana plants, 6 weeks after sowing, were used for agroinfiltration using a vacuum pump. These were entirely immersed in the bacterial suspension containing in equimolar concentration (1:1 ratio) the cultures transformed with the constructs coding for RBDw-Fc and the gene silencing inhibitor P19. Leaf samples were collected at 1, 2, 5, 7, and 9 days post infiltration (dpi) to identify the day corresponding to the peak of expression of the recombinant antigen (

Figure 1).

Western blot analysis performed under non-reducing conditions, using a human neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibody (mAb 675) against RBD, allowed to detect the presence of a band at about 110 kDa, which corresponds to the RBDw-Fc protein in dimeric form, also visible in the commercial RBD protein used as positive control (C+), and other faint bands at lower molecular weight probably due to the unassembled monomeric antigen (60 kDa) and to degradation fragments (

Figure 1). The RBDw-Fc showed the maximum level of accumulation 2 days after agroinfiltration.

2.2. RBDw-Fc Purification and Characterization

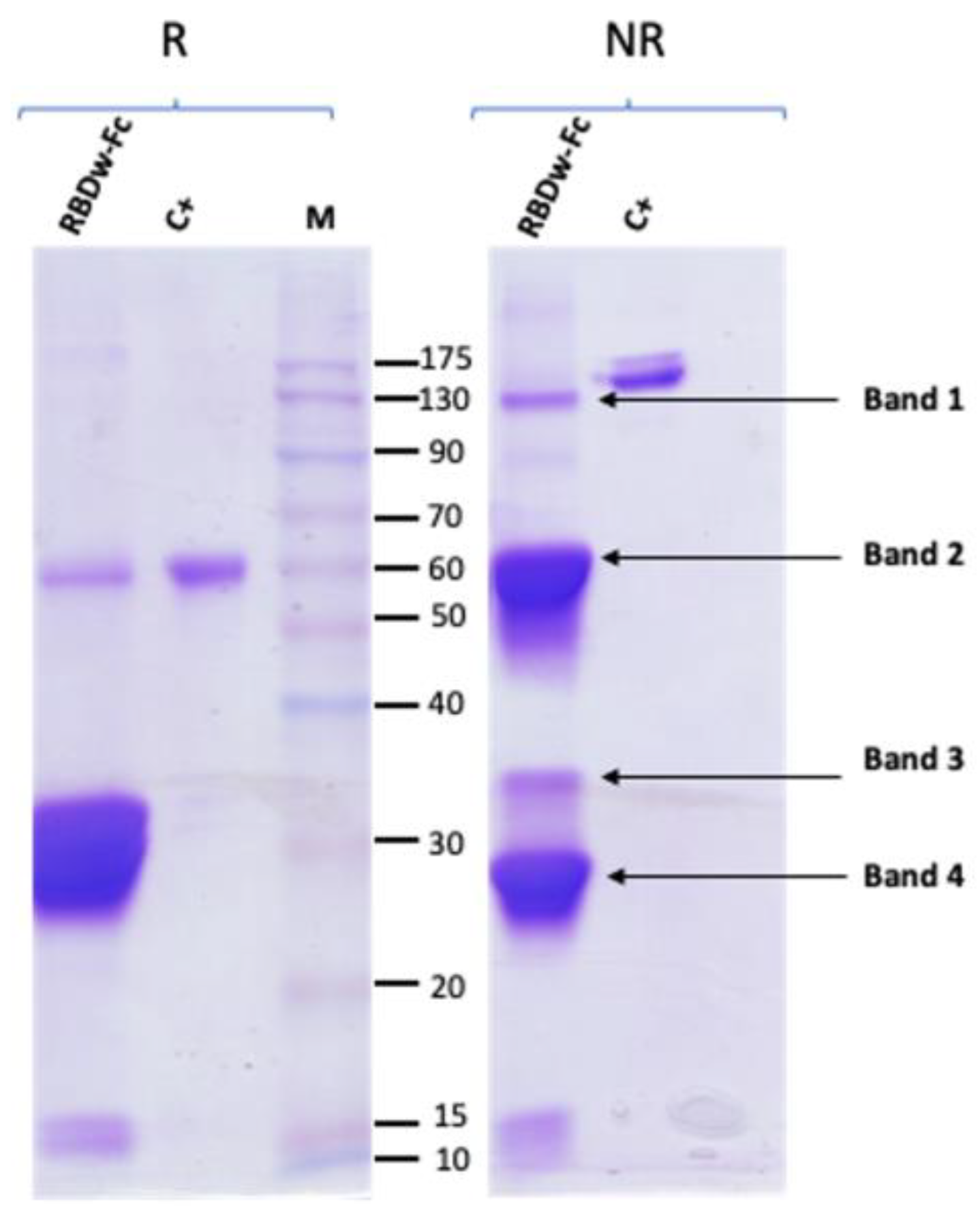

Purification of the RBDw-Fc antigen was performed by affinity chromatography. Starting from a total extract obtained by trituration and mechanical homogenization of the leaves (40 g), the RBDw-Fc antigen was purified by HiTrap protein-A affinity column chromatography, as described in Materials and Methods. The protein was then analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE analysis and Coomassie staining under reducing (R) and non-reducing (NR) conditions (

Figure 2).

Two bands were identified in the reducing gel, one relating to the intact antigen in monomeric form (55 kDa) and a very intense band with a molecular weight of 30 kDa. In the non-reducing gel, three main bands were highlighted. A first band of expected molecular weight around 110 kDa corresponding to the intact antigen in dimeric form and two other more intense bands at lower molecular weights indicating the degradation of purified RBDw-Fc (

Figure 2). The purification yield calculated on the basis of three separate experiments was found to be 45.8 ± 15.8 mg per kg of agroinfiltrated leaves.

Thus, the strategy used herein seems to be effective for fast RBDw-Fc antigen production with a good efficiency based on the obtained yield.

2.3. The RBDw-Fc Antigen-Based Test Development and Validation

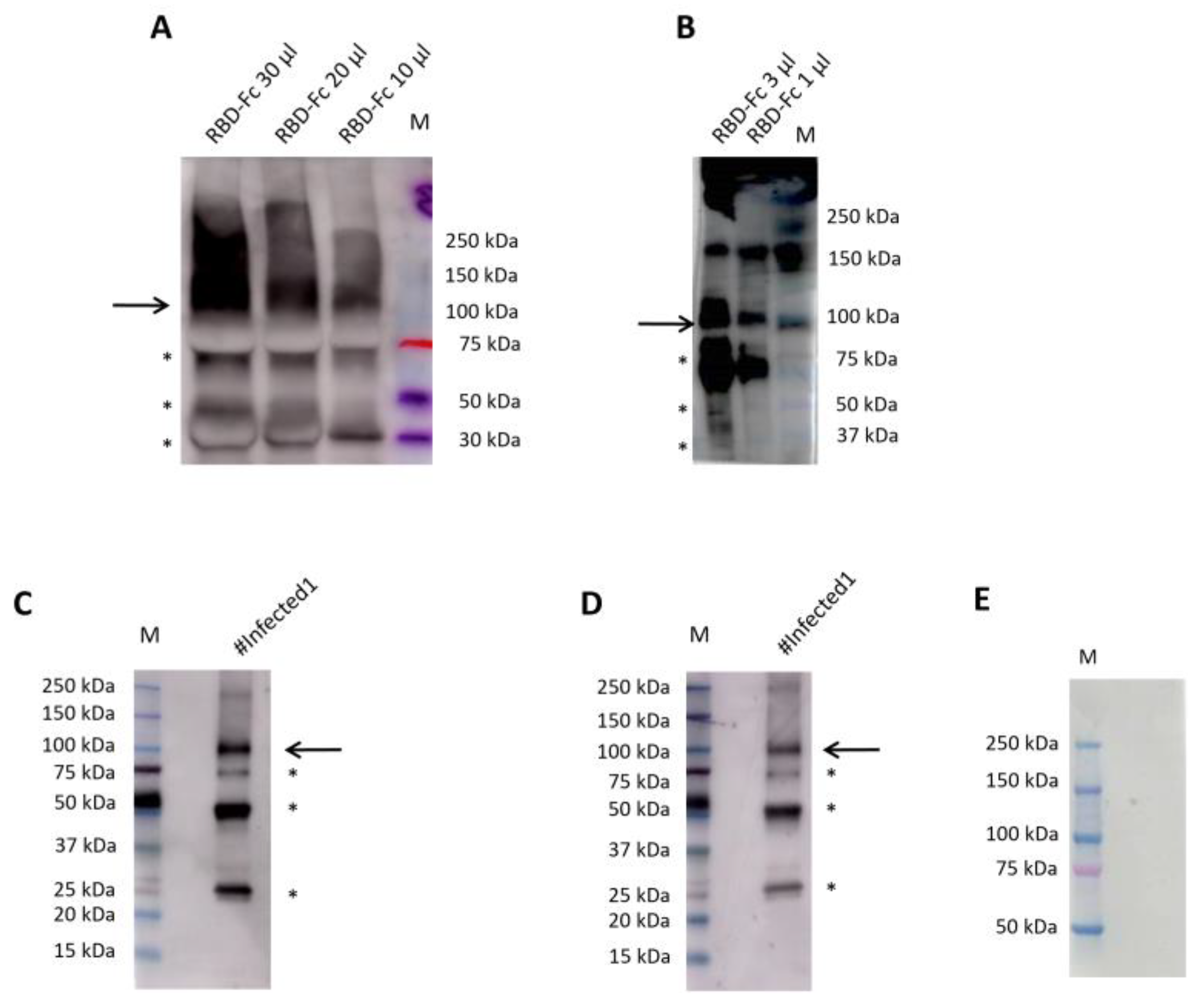

For the development of the method, we analyzed 3 samples of EDTA plasma, 3 plasma citrate, 3 plasma lithium heparin and 3 sera, with batch of plant extracts RBDw-Fc product in

Nicotiana benthamiana 1.0 µg/µl. In particular, we improved the conditions for this sample type as described below. To test the optimal conditions of RBDw-Fc antigen function, we used a western blot analysis by loading decreasing concentrations of antigen (30 µg/µl, 20 µg/µl, 10 µg/µl, 3µg/µl and 1µg/µl), in non-reducing (NR) conditions, and hybridizing them with all the 12 SARS-CoV-2 positive samples (3 EDTA plasma, 3 plasma citrate, 3 plasma lithium heparin and 3 sera samples) 1:500 in milk 5% over night at 4°C (Supplemental

Figure S1A, B). The results showed that the best antigen concentration was 1µg/µl (

Figure 3 A,B).

Moreover, the best result was obtained using EDTA samples up to a concentration of 1 µg/µl of loaded antigen. Since the results with serum and EDTA were comparable and we had many more EDTA samples than of sera, we could use this type of sample; in this way, a small volume of the sample is used and, since the EDTA plasma is the same as the blood count, more information can be obtained with one sampling. Moreover, we verified other two batches of the same antigen 1.4 µg/µl and 1.7 µg/µl finding similar results (Supplemental

Figure S2). These evidences demonstrate that antigens produced in plant are featured by quality and efficiency.

Next, to further improve antigen-antibody binding efficiency, we tested 3 different dilutions of EDTA plasma in 5% milk (1:500, 1:1000 and 1:2000) over night: interestingly, we highlighted that the 1:2000 is the best concentration (

Figure 3B-D).

A band of 110 kDa molecular weight (indicated with an arrow) was evident in the non-reducing gel (

Figure 3A-D) representing the dimeric form of the antigen. Other bands observed at molecular weights of 70 kDa, 50kDa and 25 kDa (indicated with an asterisk) were products of degradation [

9]. In order to exclude a possible non-specific binding between the antigen and the human IgG present in the secondary antibody, we hybridized our antigen only against the secondary antibody used for 1 hour, observing, as expected, the total absence of bands (

Figure 3E). These data show the high specificity and binding affinity between our RBDw-Fc antigen and the IgG in EDTA plasma samples thus showing the efficacy of the proposed test and supporting its possible use in clinical settings.

2.4. RBDw-Fc Antigen-Based Test for Covid Infection Rapid Screening

After proving the ability to obtain an efficient production of the RBDw-Fc antigen in a PMF context and the subsequent optimization and validation of the analytic procedures using different human samples, we aimed to verify the possibility to use this proposed strategy for the rapid screening of Covid infection.

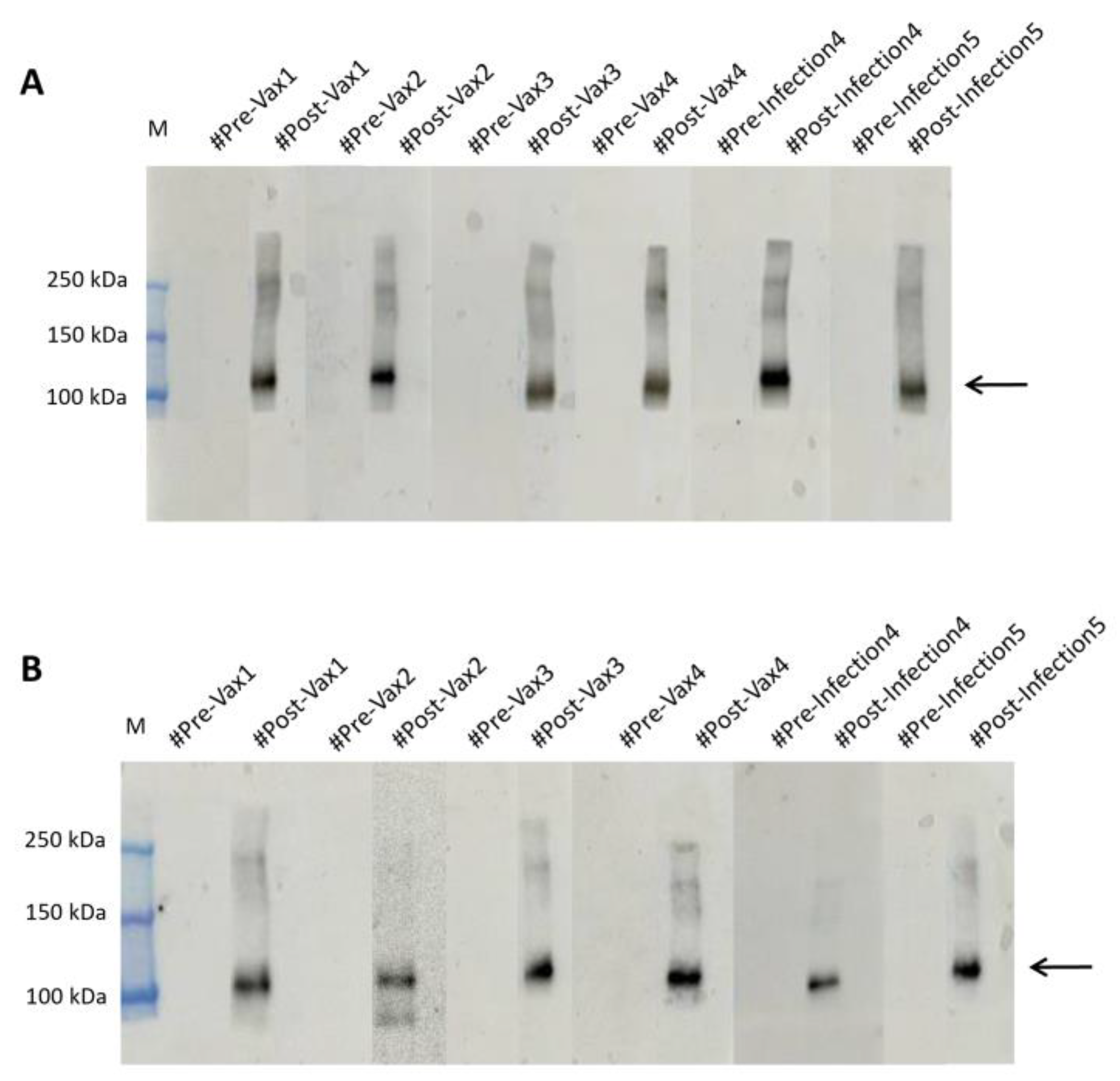

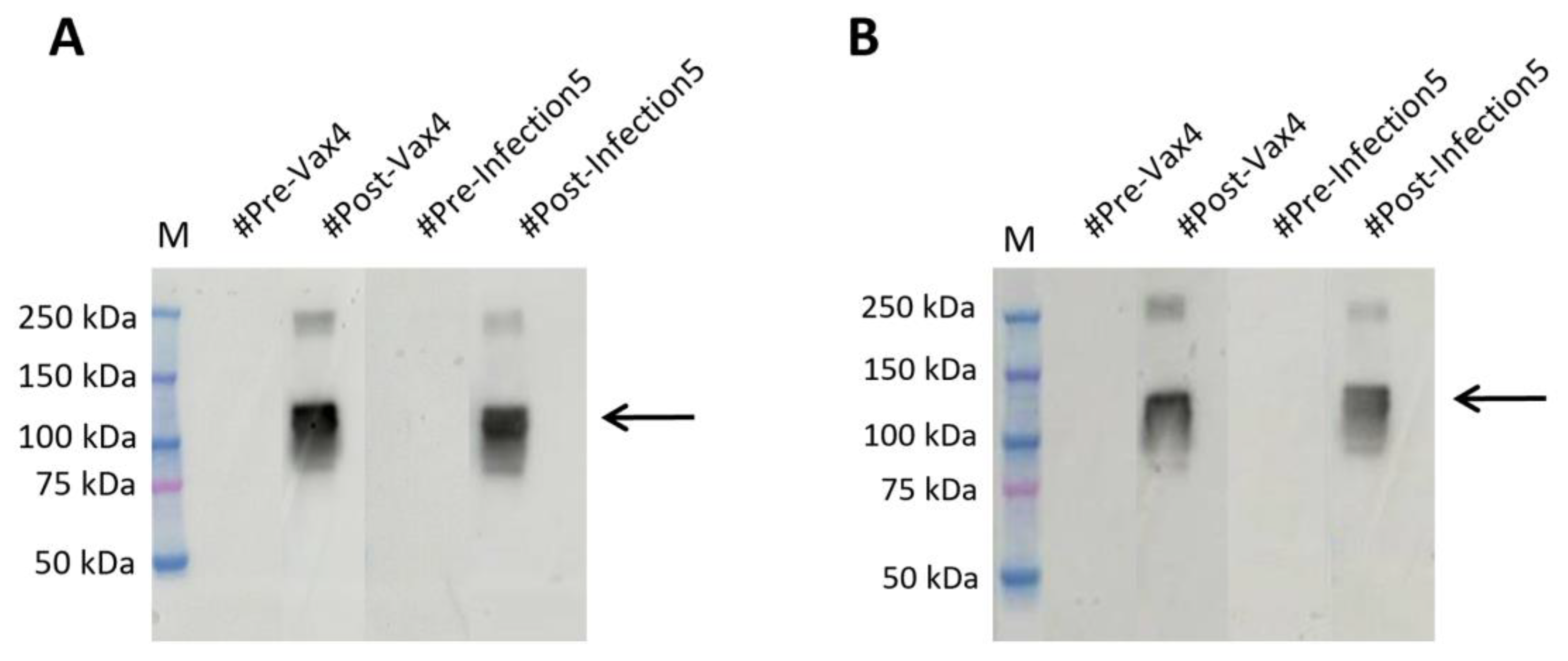

To this aim, we collected 98 anonymous samples, including both pre and post vaccination and pre and post infection samples, from the IRCCS San Raffaele Rome BioBank in blind and tested them on membranes in which we had run the produced antigen, hybridizing them over night at 4°C, so as to verify the actual presence or absence of bands as visible in

Figure 4A.

To further optimize screening times, we reduced the hybridization time to 10 minutes at RT (

Figure 4B). The data obtained, as expected, showed presence of signal in the samples that we later found to be from vaccinated patients or after viral infection. In contrast, plasma samples taken before contact with viral material showed no band. As shown in

Figure 4A,B. The result obtained on the 10 minutes hybridized samples at RT is indicative of the high potential of the plant-produced antigen as a low-cost and fast screening tool.

2.5. RBDw-Fc Antigen in Plant Is a Cheap and Innovative Test

To corroborate our thesis, we compared the results with those obtained by testing the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein (RBD) antigen (aa319-541), mFc Tag Recombinant Protein produced in HEK293 cells (Invitrogen) on the same EDTA plasma samples by means of the overnight test and 10 minute rapid test, and we verified, that protein recognition is similar to results we obtained with our antigen (

Figure 5A,B).

This result confirms our antigen RBDw-Fc as an innovative, cheap and high-quality test product obtained in plants.

3. Discussion

The recent SARS-CoV-2 pandemics, requiring large quantities of reagents for high-quality diagnosis quickly and cost-effectively, has drawn the attention of both researchers and pharmaceutical companies to the need to develop alternative production systems that can meet this growing market demand. In this scenario, Plant Molecular Farming (PMF) has emerged as a promising candidate strategy.

PMF represents an innovative technological approach that uses plants as bio-factories to produce bioactive molecules for medical, industrial, and diagnostic applications. As recently reviewed elsewhere [

10], compared to traditional systems based on mammalian cell cultures, PMF offers several advantages, including lower production costs, scalability, enhanced biosafety, and a reduced risk of contamination with human or animal pathogens. In particular, transient expression in plants has shown its reliability in the generation of vaccines candidates and therapeutic molecules [

10]. To date, PMF has proven its efficacy in numerous applications. Indeed, PMF has been used successfully to produce vaccines against human papillomavirus (HPV) and zoonotic viruses, as well as SARS-CoV-2 during the COVID-19 pandemic [

7,

11,

12,

13]. Moreover, plant-derived monoclonal antibodies are proving their efficacy also as therapeutic compounds [

14] and allows the low-cost production of industrial enzymes [

15]. Finally, plant-produced recombinant antigens are becoming even more frequently used to develop novel diagnostic tests, as in the present study. Here, we aimed to test a PMF-based strategy for the development and validation of a rapid and cost-effective screening of infective diseases and used SARS-CoV-2 as case study. The obtained results not only demonstrate the efficacy of the method developed herein, but also its ability to address economic challenges associated with large-scale reagents’ production.

Most of the immunological diagnostic tests proposed for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies are based on the use of the full-length Spike glycoprotein, the shorter external S1 segment, the N protein, or on the use of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) [

16,

17]. With regard to the latter, a first study estimated that using

N. benthamiana plants for the expression of the RBD, between 2 and 4 μg of RBD/g of fresh weight of leaves were obtained

[19]. Similarly, [

19], producing the RBD domain of SARS-CoV-2 through transient expression in

N. benthamiana, obtained 8 μg of this antigen/g of fresh weight of leaves 3 days after agroinfiltration. In this work, the antigen showed binding specificity for the ACE2 receptor, thus showing its usefulness as a reagent in diagnostics. Further studies have also obtained higher yields, 10 μg/g [

20] and 25 μg/g [

21] the RBD antigen in

N. benthamiana plants and the possibility to rapidly produce different RBD variants of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein [

9,

21] demonstrating the suitability of plant-based platforms for the production of serological reagents to address future pandemic outbreaks.

With respect to these previous studies, our work demonstrates significant advancements in antigen yield and purity. Indeed, we have shown the maximum level of accumulation, just, 2 days after agroinfiltration, with a yield of 45,8 ± 15.8 mg per kg of agroinfiltrated leaves. Moreover, we have demonstrated high affinity and binding specificity of our RBDw-Fc antigen versus human IgG. Then, we have optimized the amount of antigen requirement to 1 μg and a dilution of 1:2000 for human EDTA plasma, incubated for only 30 minutes; as a result, we optimized the binding conditions and reduced diagnostic times. Theroretically, 1Kg of agroinfiltrated leaves would be sufficient to perform about 48.000 tests. Finally, our data show that the RBDw-Fc antigen-based test produced in plants is featured by strong and easy production, high specificity, short time, significantly reduced costs, without animal involvement and greater sustainability. All these features together represent a critical point towards practical applications in clinical and point-of-care settings.

Our work contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting PMF as an innovative and scalable approach to producing diagnostic kits. Indeed, the flexibility of PMF suggests its potential for rapid adaptation to other infectious diseases and promise for addressing current and future global health challenges. Future research could focus on expanding PMF-based diagnostics to include multiplex assays or custom-designed antigens for specific viral variants, further assessing the role of PMF in the field of global diagnostic strategies.

In conclusion, our study highlights that PMF is not only a valid solution for producing antigens for SARS-CoV-2 but also represents an innovative solution that may potentially impact diagnostic reagents production on a global scale.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant’s Production of RBDw-Fc

N. benthamiana plants were grown in a hydroponic system on rock wool cubes (Cultilene Grodan, Rijen the Netherlands) with Hydro Grow type nutrient solution (Growth Technology Ltd, Taunton, UK), at 24 °C, under LED lamps (Valoya AP673L, Helsinki, Finland) with light/dark cycles of 16/8 h. Expression was carried out in fucosyl and xylosyltransferase knock-out plants optimized for the protein glycosylation profile by genome editing [

22]. Transient expression was performed by vacuum agroinfiltration with a suspension of two different LBA4404

A. tumefaciens cultures, respectively containing RBDw-Fc [

9] and P19 silencing suppressor constructs [

23]. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 4,000 x g, resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 5.8), and suspensions were mixed (RBDw-Fc and P19 at a 1:1 ratio) reaching a final OD600 of 0.5 for each construct. Plants were infiltrated at the 6-7 leaves stage and grown for another 6 days post-infiltration. For recombinant protein purification, batches of agroinfiltrated leaves (40 g) were collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C before use.

4.2. Analysis of Plant Produced RBDw-Fc by Western Blotting

Plant tissues were triturated in liquid nitrogen with a mini tissue grinder pestle in an Eppendorf tube by adding an extraction buffer (100 μl/100 mg of tissue) consisting of 1X PBS and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete Mini, Roche). Each sample was then centrifuged at 20,000 x g for 20 minutes at 5°C. The supernatant containing total soluble proteins (TSP) was then recovered. The extracts were normalized to each other for the total amount of soluble protein using a Bradford colorimetric assay.

Plant extracts were separated on 12% T SDS-PAGE acrylamide gel and analysed by Western blotting. Proteins were electrotransferred onto a PVDF membrane (Trans-Blot Turbo Mini 0.2 µm PVDF Transfer Packs, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using the Trans-Blot® Turbo™ Transfer System (1704150, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Membranes were blocked with PBS containing 4% v/v milk, overnight. For detection of RBDw-Fc protein, the membrane was incubated with an anti-mouse-Fc HRP KPL (4741802 Milford, MA, USA) conjugated antibody, at a dilution of 1:5000 in PBS containing 2% v/v skimmed milk, for 1 h, at room temperature (RT). Proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL™ Prime Western Blotting System, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with the Invitrogen iBright CL1500 imaging system (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

4.3. RBDw-Fc Extraction and Protein-A Affinity Chromatography

Plant tissues frozen in liquid nitrogen were ground into a powder by using both pestle and mortar and adding 3.5 g of polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP) to 40 g of leaf tissue. Extraction buffer (2 ml/g of leaves) consisting of PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete TM Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and ascorbic acid (0.25 g in 80 ml) was added; resulting mixtures were homogenized with an Ultra-Turrax homogenizer T25 (IKA, Staufen, Germany). The slurry was filtered through Miracloth pore size 22-25 µm (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and clarified by a double centrifugation at 8,000 x g for 20 min, at 4 °C. The supernatant was loaded onto a protein-A affinity column (1 ml HiTrap™ Protein-A FF, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA), at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The column was washed with 10 vol of PBS, and each antibody was eluted with 200 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM glycine, pH 3.0. Eluted fractions (0.5 mL each) were neutralized to about pH 7.0 with 100 ml of 1M Tris-HCl pH 9.5. The eluted proteins were dialyzed/concentrated in PBS by ultrafiltration with Vivaspin® 5,000 MWCO HY concentrator. Antibody concentration was finally determined by measuring the corresponding absorbance at 280 nm, and the corresponding purity was evaluated by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining

4.4. Biological Samples Analyzed

For the analysis of the Spike Sars-Cov-2 protein, a total of 110 biological samples, including 3 EDTA plasma, 3 sera, 3 plasma lithium heparin and 3 plasma citrate positive samples to be used as controls, and 98 previously untested EDTA plasma samples collected from the Interinstitutional Multidisciplinary BioBank (BioBIM) of the IRCCS San Raffaele in Rome, Italy, was used.

Anonymous samples were provided from patients recruited over the years. In particular, the screened samples included both samples taken prior to the Covid period, and follow-up after vaccine inoculation or the viral infection, thus allowing for results comparison between the baseline, post-vaccine and viral infection samples. All participants were recruited and followed up under appropriate institutional ethics approval and in accordance with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All activities related to this project were performed in accordance with the national regulations of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Reg. EU 2016/679), and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, both with respect to the security and protection of personal data and the technical requirements for storing these data.

Each of the patients has previously signed an informed consent for data processing and privacy protection according to current regulations Art.13 of Legislative Decree no. 196/2003

4.5. Western Blot Analysis of Blood Samples

Three different batches of the plant extracts RBDw-Fc produced in

Nicotiana benthamiana (1.0 µg/µl,1.4 µg/µl and 1.7 µg/µl) [

9] were prepared with 4x Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA), boiled at 95°C for 5 min and run on a non-reducing 4-20% gradient SDS-PAGE (Mini-Protean TGX Stain-Free Precast Gels, Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA). For Western blot analysis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Trans-Blot Turbo Mini 0.2 µm Nitrocellulose Transfer Pack, Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) with Transfer unit (Trans-Blot® Turbo™ Transfer System, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) for 7 min. Membranes were blocked in 10 ml of EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) for 5 min, with agitation at RT, washed three times with TBS-T (final concentration TBS 1x, cat#1706435; 0,01% Tween-20 cat#1610781, Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA). After this, for the rapid tests, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (Plasma EDTA 1:500, 1:1000 and 1:2000 in TBS-T containing 5% milk) for 10 min at RT with agitation. The same samples and concentrations of Plasma EDTA were incubated overnight at 4˚C, as well as the samples of plasma citrate, plasma lithium heparin and sera concentrated 1:500 in TBS-T containing 5% milk. The membranes were washed three times with TBS-T followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated Goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody in dilution 1:10.000 in TBS-T containing (Invitrogen cat#31482, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) for 10 min with agitation in rapids test, and 1 hour for normal analysis. After washing, the signal was detected using LiteAblot ®PLUS Enhanced Chemiluminescent Substrate for Western Blotting (Euroclone S.p.A, Milan, Italy) and imaged using Amersham ImageQuant™ 800 (Amersham, UK). The protein molecular weight markers were BenchMark™ Pre-stained Protein Ladder (Invitrogen, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and Precision Plus Protein Kaleidoscope (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G. and M.D.; methodology, C.M., Ca.M., D.R., M.G.V., A.S., G.G., V.A. and L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M. and L.L.; writing—review and editing, P.F. and V.D.; supervision, F.G. and M.D.; funding acquisition, F.G. and M.D.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente) and the Italian Ministry of Education, Universities and Research with the 5X1000-2021 fund to the project “Plants as biofactories of vaccines and antibodies for the COVID-19 emergency”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The BioBIM project was approved by the IRCCS San Raffaele Ethics Committee on 15 November 2006 with approval number ISR/DMLBA/405. Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all recruited individuals. All activities related to this project are performed in accordance with the national regulations of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Reg. EU 2016/679), and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, both with respect to the security and protection of personal data and the technical requirements for storing these data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study for data processing and privacy protection according to current regulations Art.13 of Legislative Decree no. 196/2003.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are provided within this article. Further information can be provided by the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Julia Jansing and Luisa Bortesi for kindly providing N. benthamiana FX-KO seeds from RWTH Aachen University. In addition, the authors wish to thank Luigi Narducci and Danilo Sayed Ibrahim for their excellent technical assistance in biobanking activities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Obembe, O.O.; Popoola, J.O.; Leelavathi, S.; Reddy, S.V. Advances in plant molecular farming. Biotechnol Adv 2011, 29, 210–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, M.E.; Woodard, S.L.; Howard, J.A. Plant molecular farming: systems and products. Plant Cell Rep 2004, 22, 711–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugaraj, B.; Siriwattananon, K.; Wangkanont, K.; Phoolcharoen, W. Perspectives on monoclonal antibody therapy as potential therapeutic intervention for Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19). Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2020, 38, 10–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lico, C.; Santi, L.; Baschieri, S.; Noris, E.; Marusic, C.; Donini, M.; et al. Plant Molecular Farming as a Strategy Against COVID-19 – The Italian Perspective. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11, 609910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demurtas, O.C.; Massa, S.; Illiano, E.; De Martinis, D.; Chan, P.K.S.; Di Bonito, P.; et al. Antigen Production in Plant to Tackle Infectious Diseases Flare Up: The Case of SARS. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Verma, P.C.; Singh, P.K.; Tuli, R. Plants as bioreactors for the production of vaccine antigens. Biotechnol Adv 2009, 27, 449–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahmanova, G.; Takova, K.; Valkova, R.; Toneva, V.; Minkov, I.; Andonov, A.; et al. Plant-Derived Recombinant Vaccines against Zoonotic Viruses. Life 2022, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüce, M.; Filiztekin, E.; Özkaya, K.G. COVID-19 diagnosis -A review of current methods. Biosens Bioelectron 2021, 172, 112752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagiani, F.; Frigerio, R.; Salzano, A.M.; Scaloni, A.; Marusic, C.; Donini, M. Plant production of recombinant antigens containing the receptor binding domain (RBD) of two SARS-CoV-2 variants. Biotechnol 2024, 46, 1303–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, S. Plant Molecular Pharming and Plant-Derived Compounds towards Generation of Vaccines and Therapeutics against Coronaviruses. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.H.; Church, D.; Koellhoffer, E.C.; Osota, E.; Shukla, S.; Rybicki, E.P.; et al. Integrating plant molecular farming and materials research for next-generation vaccines. Nat Rev Mater 2022, 7, 372–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.J.; Kim, H.; Jang, E.Y.; Jeon, H.; Diao, H.P.; Khan, M.R.I.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike trimer vaccine expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana adjuvanted with Alum elicits protective immune responses in mice. Plant Biotechnol J 2022, 20, 2298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahmanova, G.; Aljabali, A.A.A.; Takova, K.; Minkov, G.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Minkov, I.; et al. Green Biologics: Harnessing the Power of Plants to Produce Pharmaceuticals. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 17575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussavou, G.; Ko, K.; Lee, J.H.; Choo, Y.K. Production of monoclonal antibodies in plants for cancer immunotherapy. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 306164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillberg, S.; Finnern, R. Plant molecular farming for the production of valuable proteins - Critical evaluation of achievements and future challenges. J Plant Physiol 2021, 153359, 258–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, K.G.; Wetzel, K.S.; Zhang, Y.; Zack, K.M.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Walters, S.M.; et al. A Mycobacteriophage-Based Vaccine Platform: SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Expression and Display. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumpp-Thomas, C.; Kalish, H.; Drew, M.; Hunsberger, S.; Snead, K.; Fay, M.P.; et al. Standardization of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for serosurveys of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic using clinical and at-home blood sampling. medRxi, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Diego-Martin, B.; González, B.; Vazquez-Vilar, M.; Selma, S. , Mateos-Fernández, R.; Gianoglio, S.; et al. Pilot Production of SARS-CoV-2 Related Proteins in Plants: A Proof of Concept for Rapid Repurposing of Indoor Farms Into Biomanufacturing Facilities. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11, 612781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanapisit, K.; Bulaon, C.J.I.; Khorattanakulchai, N.; Shanmugaraj, B.; Wangkanont, K.; Phoolcharoen, W. Plant-produced SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain (RBD) variants showed differential binding efficiency with anti-spike specific monoclonal antibodies. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0253574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.J.; König-Beihammer, J.; Vavra, U.; Schwestka, J.; Kienzl, N.F.; Klausberger, M.; et al. N-Glycosylation of the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor Binding Domain Is Important for Functional Expression in Plants. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 689104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwattananon, K.; Manopwisedjaroen, S.; Shanmugaraj, B.; Rattanapisit, K.; Phumiamorn, S.; Sapsutthipas, S.; et al. Plant-Produced Receptor-Binding Domain of SARS-CoV-2 Elicits Potent Neutralizing Responses in Mice and Non-human Primates. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 682953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansing, J.; Sack, M.; Augustine, S.M.; Fischer, R.; Bortesi, L. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of six glycosyltransferase genes in Nicotianabenthamiana for the production of recombinant proteins lacking β-1,2-xylose and core α-1,3-fucose. Plant Biotechnol J 2019, 17, 350–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, R.; Circelli, P.; Villani, M.E.; Buriani, G.; Nardi, L.; Coppola, V.; et al. High-level HIV-1 Nef transient expression in Nicotianabenthamiana using the P19 gene silencing suppressor protein of Artichoke Mottled Crinckle Virus. BMC Biotechnol 2009, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).