Submitted:

11 April 2023

Posted:

12 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Submerged Landscapes: The Impact of Climate Change on Coastal Territories

1.2. The “regulatory dimension” of territorial government tools

- STEP 1 | Implementation of the territory’s cognitive framework through the preparation of a “multi-risk” map - with a time horizon to 2100 - concerning the consistency of floods caused by the concomitance of heavy rainfall and river’s overflow (transient and non-linear phenomena) and sea-level rise (stable and progressive phenomenon);

- STEP 2 | Definition of a toolkit of site-specific adaptation actions embedded in broader urban resilience strategies of “defence”, “adaptation” and “relocation” [24], complementing the prescriptive apparatus of the Local Urban Plan (STEP 2).

2. Materials

2.1. Case Study

2.2. PRG of the Municipality of Fiumicino

- Zone A: historic center, historic buildings;

- Zone B: completion zone, consolidated residential building;

- Zone C: expansion housing;

- Zone D: zone for productive settlements;

- Zone E: agricultural area;

- Zone F: zone for collective facilities and equipment.

2.3. PGRAAC risk maps

- a)

- low probability or extreme event scenarios

- b)

- average probability of flooding

- c)

- high probability of flooding

2.4. SLR projections to 2100

- RCP 2.6 mitigation scenario (very high emission reduction);

- RCP 4.5 stabilization scenario (large reductions);

- CPR 6.0 stabilization scenario (mild reductions);

- RCP 8.5 high emission scenario (“business as usual”).

3. Methodology

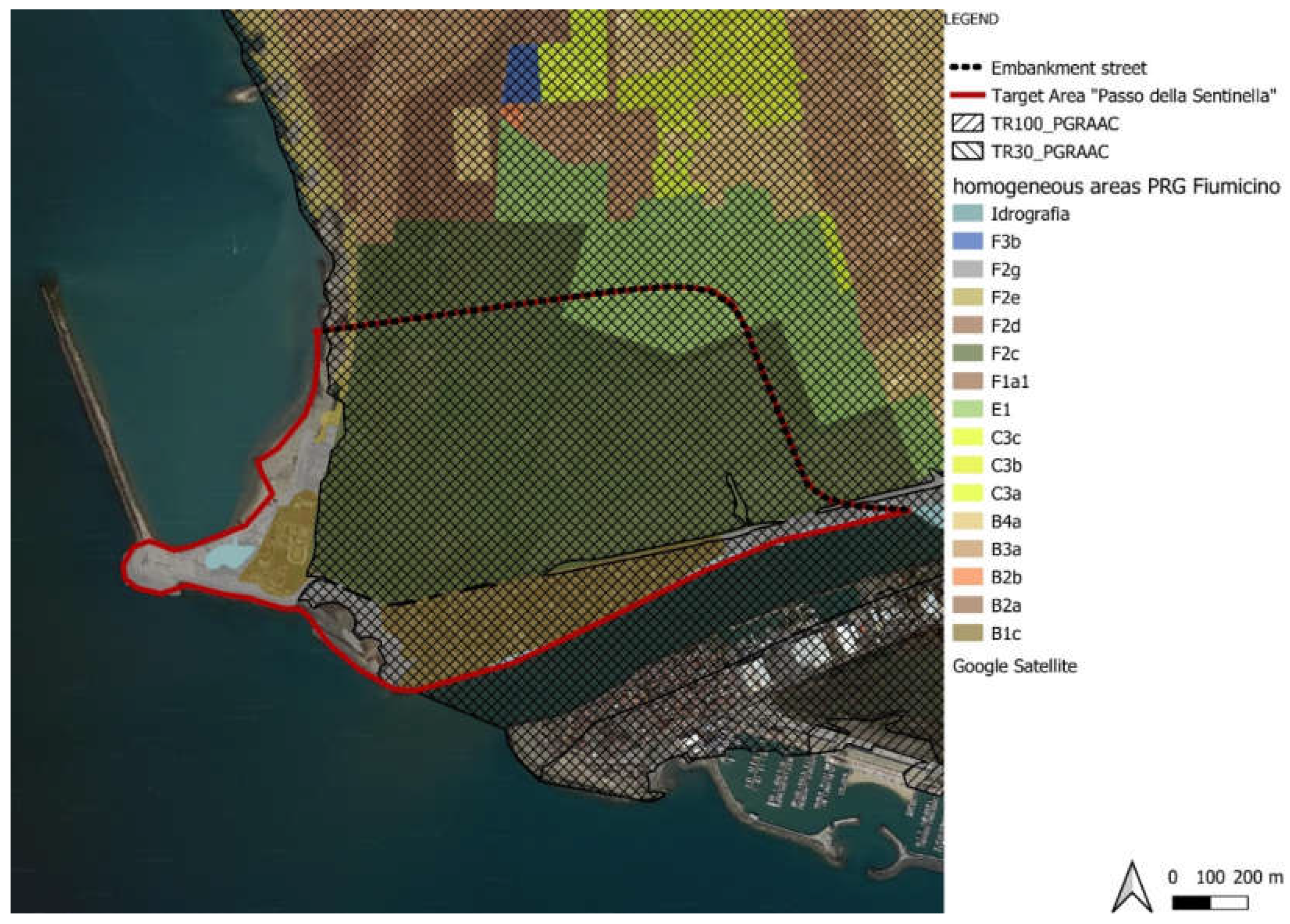

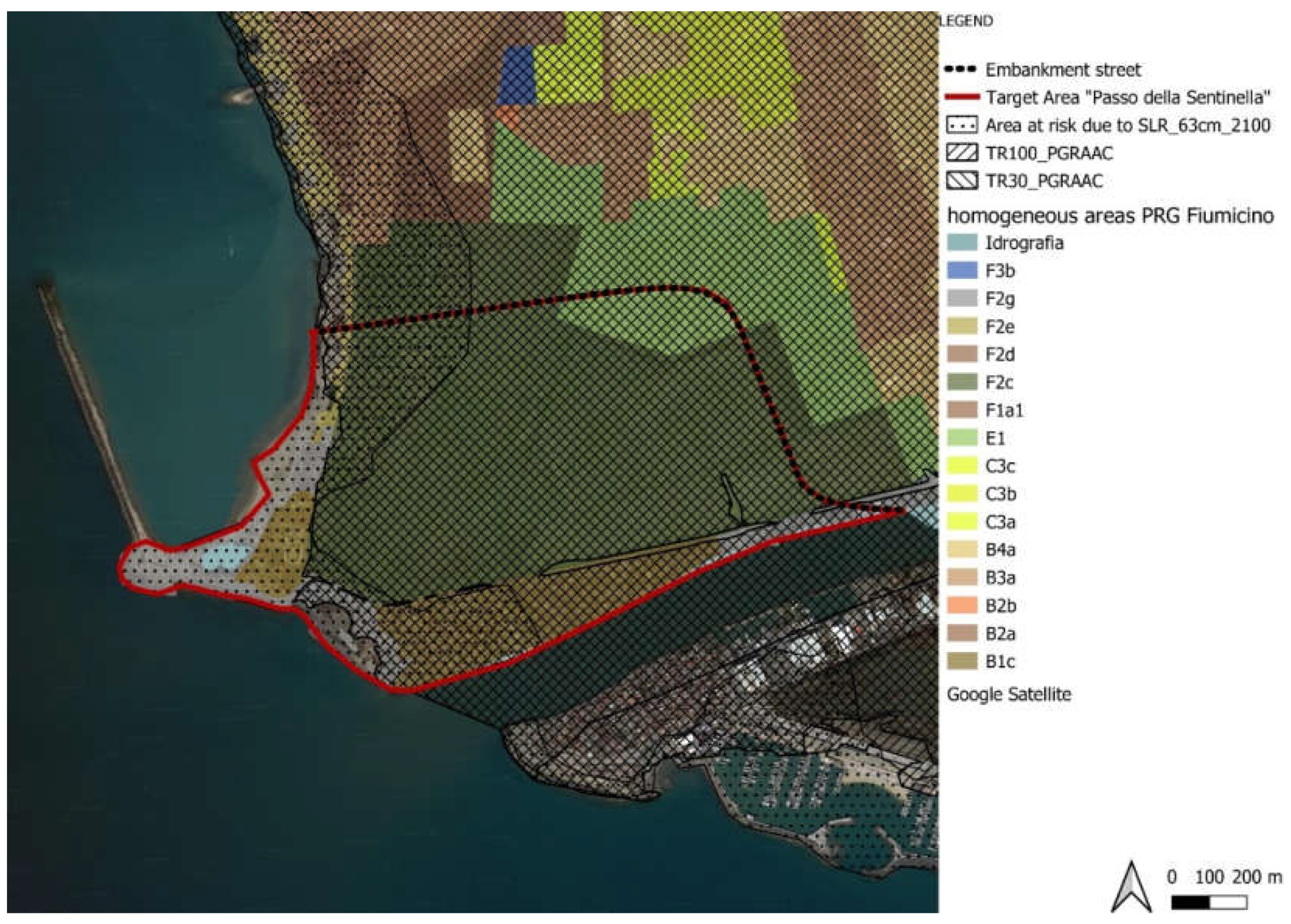

3.1. STEP 1: Integration of the territory's cognitive framework concerning the risk of flooding due to heavy rainfall and river’s overflow and sea-level rise phenomena

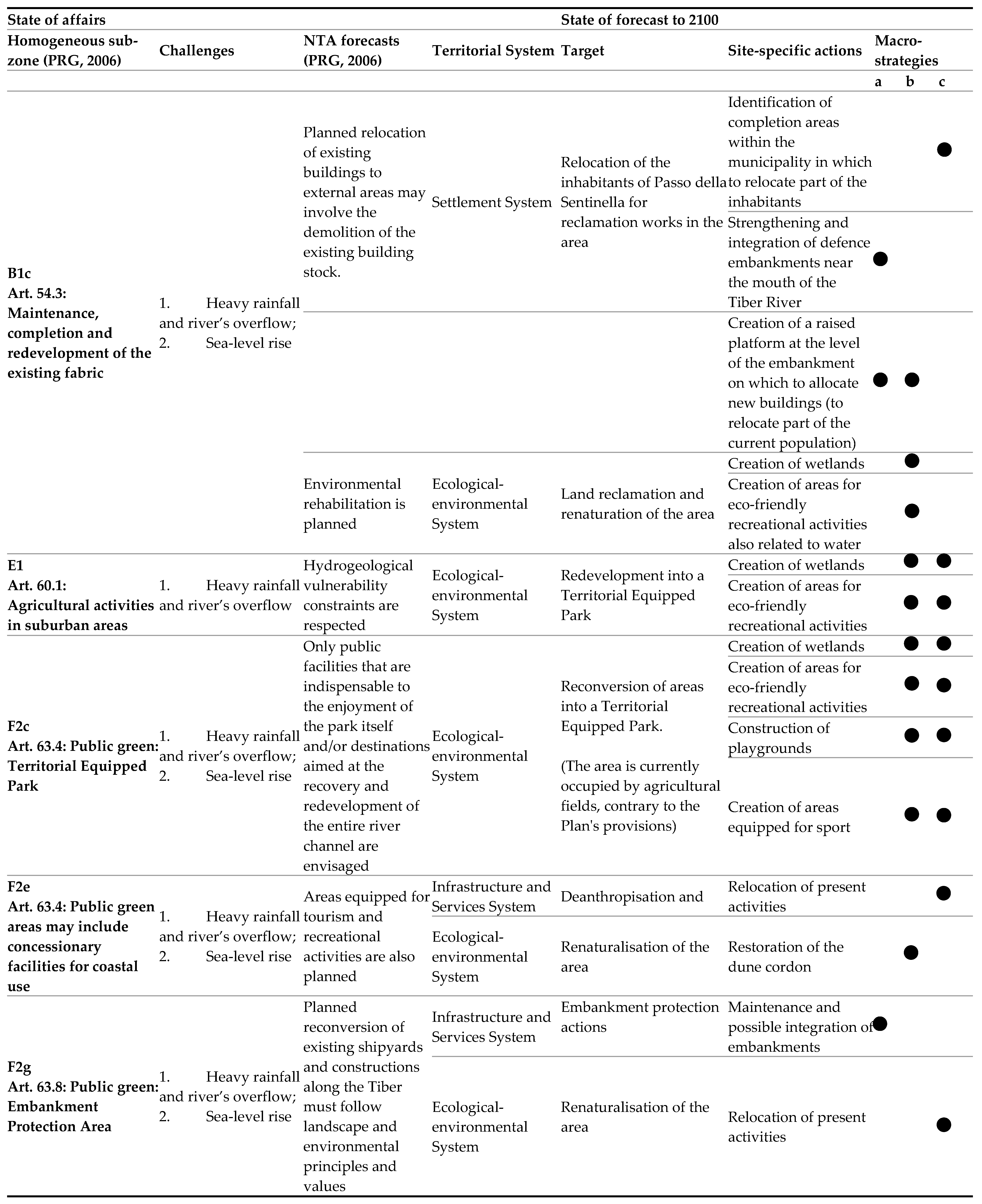

3.2. STEP 2: Definition of the site-specific action toolkit for the risk of flooding caused by heavy rainfall and river’s overflow and sea-level rise phenomena

- a “state of affairs”, which considers the current Local Plan forecasts for the Homogeneous sub-zones included in the Target Area;

- a “state of forecast to 2100”, with a 100-year time horizon, which validates or supplements the forecasts currently in force for those areas, to provide indications for the future updating of the Plan in the light of the risk highlighted by the multi-risk maps of the area obtained in "STEP 1".

- the Homogeneous sub-zones within the Target Area;

- the challenges affecting the reference sub-zones to which the adaptation action must respond (in this case heavy rainfall and river's overflow, and sea-level rise);

- the forecasts (currently in force) indicated in the NTAs of the Plan for each homogeneous sub-zones;

- the physical-territorial system most affected by the risk phenomenon and therefore the one that will receive the greatest benefits from adaptation action: the Ecological-environmental System, the Settlement System, the Infrastructure and Services System.

- some targets (i.e. the adaptation goals to be achieved in the light of the flood risk);

- several site-specific actions (each of which will refer to a reference macro-strategy: “defence”, “adaptation”, or “relocation”) to be sought (during the project phase) in best practices with similar characteristics to the area under study).

4. Discussion and Results

4.1. STEP 1 | Quanti-Qualitative Reading of Sub-zones at Risk of Flooding due to Heavy Rainfall and River’s Overflow, and Sea-level Rise

4.2. STEP 2: Application of the toolkit to Target Area A – passo della Sentinella

- a “state of affairs” that illustrates the current NTA prescriptions for the relevant sub-zones within the target area, the risk scenario they face (determined in STEP 1 with Table 2 and Table 3), and the territorial system in which the urban components most affected by flooding occur (Ecological-environmental System, Settlement System, Infrastructure, and Services System);

- a “state of forecast to 2100”, which outlines the goals for adapting the area through site-specific actions (which fall under one of the three macro-strategies of “defence”, “adaptation”, and “relocation”, indicated in Table 4 as “a”, “b”, and “c” respectively).

- The relocation of Passo della Sentinella's inhabitants for reclamation works (a target already stated in the current Plan's provisions);

- Land reclamation and renaturation of the area.

- 1.1.

- Identification of completion areas within the municipal territory to which part of the inhabitants will be relocated (an action also explicitly stated in the current Plan's forecasts);

- 1.2.

- Strengthening and integration of defence embankments near the mouth of the Tiber River;

- 1.3.

- Creation of a raised platform at the embankment level to construct buildings, including residential buildings, in which part of the current population will be relocated;

- 2.1.

- Creation of wetlands;

- 2.2.

- Creation of areas for eco-friendly recreational activities related to water.

- 1

- Reconversion into a Territorial Equipped Park, which aligns with the intended use of contiguous "F2c" zones as per the current NTAs. It is considered plausible that even though the portions of the E1 sub-zone falling within the target area A - Passo della Sentinella, seem not affected by flooding from SLR, this will still be affected in some way as they are excluded from the protection of the embankment road.

- 1.2.

- Creation of wetlands;

- 1.3.

- Creation of areas for eco-friendly recreational activities

- Deanthropisation;

- Renaturalisation of the area.

- 1.1.

- Relocation of present activities;

- 2.1.

- Restoration of the dune cordon.

- Actions to protect embankments (a target that is also made explicit in the current provisions of the Plan);

- Renaturalisation of the area.

- 1.1.

- Maintenance and possible integration of embankments;

- 1.1.

- Relocation of present activities

5. Conclusion

- Sub-zone B1c, concerning the relocation of the inhabitants of Passo della Sentinella to identified completion areas within the municipal territory.

- Sub-zone F2g, concerning embankment protection actions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GRID. 2022 Global Report on Internal Displacement; IDMC Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2022. Available online: https://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/IDMC_GRID_2022_LR.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- OIM Annual Report 2020; UN Migration. 2022. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/highlights-2020-annual-report (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- IPCC Climate Change and Land An IPCC Special Report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems; IPCC. 2019. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2019/11/SRCCL-Full-Report-Compiled-191128.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Susana, B. Adamo. Environmental migration and cities in the context of global environmental change. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 2010; 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhin, S. A. , et al. Migration health crisis associated with climate change: A systematic review. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. [CrossRef]

- COM. Communication on a New Pact on Migration and Asylum English; European Commission. 2020. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/migration-and-asylum-package-new-pact-migration-and-asylum-documents-adopted-23-september-2020_en (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Findlay, M. et al. Migrant destinations in an era of environmental change; Global Environmental Change, Volume 21, Pages S50-S58, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, O. , et al. Climate Change, Drought, and Potential Environmental Migration Flows Under Different Policy Scenarios. International Migration Review, 2023; 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. World Urbanization Prospects 2018; Department of Economic and Social AffairsPopulation Dynamics, 2018. Available onlie: https://population.un.org/wup/. (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Schug, G. R. , et al. Climate change, human health, and resilience in the Holocene; PNAS 2022. [CrossRef]

- Thi Phuoc Lai Nguyen, Salvatore G.P. Virdis, Thanh Bien Vu, “Matter of climate change” or “Matter of rapid urbanization”? Young people's concerns for the present and future urban water resources in Ho Chi Minh City metropolitan area, Vietnam; Applied Geography, Volume 153, 2023. [CrossRef]

- UN. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations, 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Kabisch, N. , et al. Principles for urban nature-based solutions; Ambio 51, 1388 (1401), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N. , et al. Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: Perspectives on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action; Ecology and Society, 21 (39), 2016. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; IPCC, 2019. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/ (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- EEA. Marine messages II Navigating the course towards clean, healthy and productive seas through implementation of an ecosystem-based approach; EEA Report No 17, 2019. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/marine-messages-2/ (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- UN-Habitat. Envisaging the Future of Cities; World city Report, 2022. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/06/wcr_2022.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- ISPRA. Rapporto sulle condizioni di pericolosità da alluvione in Italia e indicatori di rischio associati; ISPRA Report 353, 2021. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/files2021/pubblicazioni/rapporti/rapporto_alluvioni_ispra_353_16_11_2021_rev2.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Legambiente. I migranti ambientali. L’altra faccia della crisi climatica; Dossier, 2021. Available online: https://www.legambiente.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/I-migranti-ambientali_dossier_2021.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Gallina, V. et al. A Multi-Risk Methodology for the Assessment of Climate Change Impacts in Coastal Zones; Sustainability, 12, 3697, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Long, J. , et al. From sustainable urbanism to climate urbanism; Urban Studies, 56(5), 992–1008, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mariano, C. Climate Proof Planning for an urban regeneration Strategy. The Academic Research Community Publication, 6(1), 01-11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Marino, M. Governare la transizione. Il Piano urbanistico locale tra sperimentazione e innovazione climate-proof. FrancoAngeli.

- Mariano, C. , Marino, M. Defense, adaptation and relocation. Three strategies for urban planning of coastal areas at risk of flooding, Planning, Nature and Ecosystem Services INPUT aCAdemy 2019 Conference proceedings, C. Gargiulo, C. Zoppi, edited by, TeMA. FedOA Press, 2019. ,. [CrossRef]

- Brick, M. , et al. Climate-proof planning for flood-prone areas: assessing the adaptive capacity of planning institutions in the Netherlands; Regional Environmental Change volume 14, pages981–995, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Swart, R. , et al, Climate-Proofing Spatial Planning and Water Management Projects: An Analysis of 100 Local and Regional Projects in the Netherlands; Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, Volume 16, Issue 1, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Biasin, A. , et al. Nature-Based Solutions Modeling and Cost-Benefit Analysis to Face Climate Change Risks in an Urban Area: The Case of Turin (Italy). Land, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonioli F., et al. Sea-level rise and potential drowning of the Italian coastal plains: Flooding risk scenarios for 2100; Quaternary Science Reviews, 158 (14), 2017. [CrossRef]

- PGRAAC. Piano di Gestione del Rischio Alluvioni del distretto idrografico dell’Appennino Centrale (PGRAAC); Autorità di bacino distrettuale dell'Appennino Centrale, 2018. Available online: autoritadistrettoac.it/pianificazione/pianificazione-distrettuale/pgraac (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- PGRAAC. Piano di Gestione del Rischio alluvioni dell’Appennino Centrale; Autorità di bacino distrettuale dell’Appennino Centrale, 2018. Available online: https://www.autoritadistrettoac.it/sites/default/files/pianificazione/pgraac_2/mappe_peric_rischio/valut_glob_provv.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Keay, S. , Millett,M., Strutt,K., Germoni, P. The Isola Sacra Survey Ostia, Portus and the port system of Imperial Rome, Mcdonald Institute Monographs; Cambridge, UK, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fiumicino PRG. Piano Regolatore Generale di Fiumicino; Comune di Fiumicino, 2006. Available online: https://www.comune.fiumicino.rm.it/index.php?option=com_docman&view=list&slug=piano-regolatore-generale&Itemid=389 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Tinitaly. DEM Italia; Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, 2010. Available online: https://tinitaly.pi.ingv.it/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Sannino G., et. Al. Modelling present and future climate in the Mediterranean Sea: a focus on sea-level change; Climate Dynamics, 59 (57–391), 2022. [CrossRef]

- PGRAAC. Alluvioni - Estensione dell'area allagabile (PGRA 2021); Geoportale Nazionale, 2021. Available online: pcn.minambiente.it/mattm/servizio-di-scaricamento-wfs/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- IPCC. AR5 – Synthesis Report; IPCC, 2013. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- IPCC. AR6 - Climate Change 2021. The Physical Science Basis Summary for Policymakers; IPCC, 2021 Available online:. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SPM_final.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Caserini, S. Scenari internazionali di emissione e assorbimenti di gas serra congruenti con l’Accordo di Parigi, Ispra Report. 2018. Available online: https://www. isprambiente.gov.it/files2018/eventi/gas-serra/CaseriniRoma1552018.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- van Vuuren, D.P. , et al. The representative concentration pathways: an overview; Climatic Change 109, 5. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, R. J.; , et al. Beyond shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) and representative concentration pathways (RCPs): climate policy implementation scenarios for Europe, the US and China. Climate Policy, Volume 21, Issue 4, 2021. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/global-literature-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/resource/pt/covidwho-990389 (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Mariano, C. , Marino, M., Pisacane, G., Sannino, G. Sea Level Rise and Coastal Impacts: Innovation and Improvement of the Local Urban Plan for a Climate-Proof Adaptation Strategy. Sustainability, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppla. Available online: https://oppla.eu/nbs/case-studies (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Naturvation. Available online: https://naturvation.eu/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- ThinkNature. Available online: https://www.think-nature.eu/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Natural Water Retention Measures Available online:. Available online: http://nwrm.eu/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Panorama EbA. Available online: https://panorama.solutions/en/portal/panorama-eba (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Mariano, C. , Marino, M. Urban planning for climate-change. A toolkit of actions for an integrated strategy of adaptation to heavy rains, river flood and sea level rise. Urban Science, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskamp, I. M. , et al. Nature-Based Solutions Tools for Planning Urban Climate Adaptation: State of the Art; Sustainability, 13, 6381, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Henstra, D. The tools of climate adaptation policy: analysing instruments and instrument selection; Climate Policy, Volume 16, Issue 4, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Abbate, A. , Giampino, A., Orlando, M., Todaro, V. Territori costieri; FrancoAngeli, Milano, 2009.

- Bell, S. , et al. Delta Urbanism. The Netherlands; American Planning Association, 2017.

- Crutzen, P. , Parlangeli A. (a cura di), Benvenuti nell'Antropocene. L'uomo ha cambiato il clima, la Terra entra in una nuova era; Mondadori, 2017.

- D. Ryan, B. D. Ryan, B., Vega-Barachowitz, D., Perkins-High, L. Rising tides: relocation and sea level rise in metropolitan Boston; Norman B. Leventhal Center for advanced urbanism, 2015.

- Maccarone, C. Profughi ambientali in cerca di protezione; Osservatorio diritti, 2017. Available online: https://www.osservatoriodiritti.it/2017/09/20/profughi-ambientali-immigrazione-asgi/ (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Musco, F. , Zanchini, E. Il clima cambia le città. Strategie di adattamento e mitigazione nella pianificazione urbanistica; Franco Angeli, Milano, 2014.

- The city of New York - Department of city planning, Coastal Cimate Resilience. Urban Waterfront Adaptive Strategies, 2013.

- The city of New York - Department of city planning, One New York The Plan for a Strong and Just City, 2015.

- Galderisi, A. Adapting Cities For A Changing Climate: An Integrated Approach For Sustainable Urban Development; WIT PRESS, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Climat ADAPT, Integration of climate change adaptation in land use planning, 2023. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/metadata/adaptation-options/adaptation-of-integrated-land-use-planning (accessed on 2 April 2023).

| Homogeneous Territorial Zones | Homogeneous sub-zone | Art. of the NTA | Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| B | Sub-zone B1c | Art. 54.3 Maintenance, completion and redevelopment of existing fabric: building maintenance zone for rehabilitation and environmental remediation |

[...] The nucleus known as Passo della Sentinella will be subjected to implementation planning aimed at the environmental redevelopment of the site. This target may be pursued through reclamation works, also after the demolition of the existing building stock and relocation of the same in external areas [...]. |

| E | Sub-zone E1 | Art. 60.1 Agricultural activities in suburban areas: agricultural areas in the settled territory | [...] Lands with hydrogeological vulnerability [...]. |

| F | Sub-zone F2c | Art. 63.4 Public green: Territorial Equipped Park | [...]Only public facilities that are essential for enjoying the park itself or for the recovery and redevelopment of the entire river channel are envisioned. |

| Sub-zone F2e | Art. 63.4 Public green areas may include concessionary facilities for coastal use, as well as open-air facilities for tourism and leisure activities | [...] The adaptation of sanitary facilities is permitted up to a 10% increase of the existing covered surface area, as well as the demolition and reconstruction of existing buildings, with indications of their use for bathing services, refreshments, storage, and outdoor equipment [...] | |

| Sub-zone F2g | Art. 63.8 Public green: Embankment Protection Area | [...] The reconversion of existing shipyards and buildings for use along the Tiber is allowed, if landscape and environmental principles and values are respected [...] |

| Homogeneous Territorial Zones | Homogeneous sub-zone | Area of the sub-zone within the target area | Area at risk falling within the sub-zone (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B | Sub-zone B1c | 186.294,84 m² | 111.421,442 m² (59,81%) |

| E | Sub-zone E1 | 57.865,863 m² | 0% |

| F | Sub-zone F2c | 781.719,024 m² | 115.745,177 m² (14,81%) |

| Sub-zone F2e | 9.239,793 m² | 100% | |

| Sub-zone F2g | 106.194,836 m² | 86.905,14 m² (81,84%) |

| Homogeneous Territorial Zones | Homogeneous sub-zone | Area of the sub-zone within the target area | Area at risk falling within the sub-zone (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B | Sub-zone B1c | 186.294,84 | 142.710,330 m² (76,69%) |

| E | Sub-zone E1 | 57.865,863 m² | 100% |

| F | Sub-zone F2c | 781.719,024 m² | 766.205,248 m² (98,02%) |

| Sub-zone F2e | 9.239,793 m² | 5.122,698 m² (55,44%) | |

| Sub-zone F2g | 106.194,836 m² | 38.362,938 m² (36,12%) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).