Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The knowledge that supports the identification and assessment of risks to the built environment, settled communities and infrastructures;

- The tools and the modalities of intervention urban planning can deploy to reduce and mitigate expected negative impacts and damages;

- The constraints and obstacles in implementing such plans and interventions.

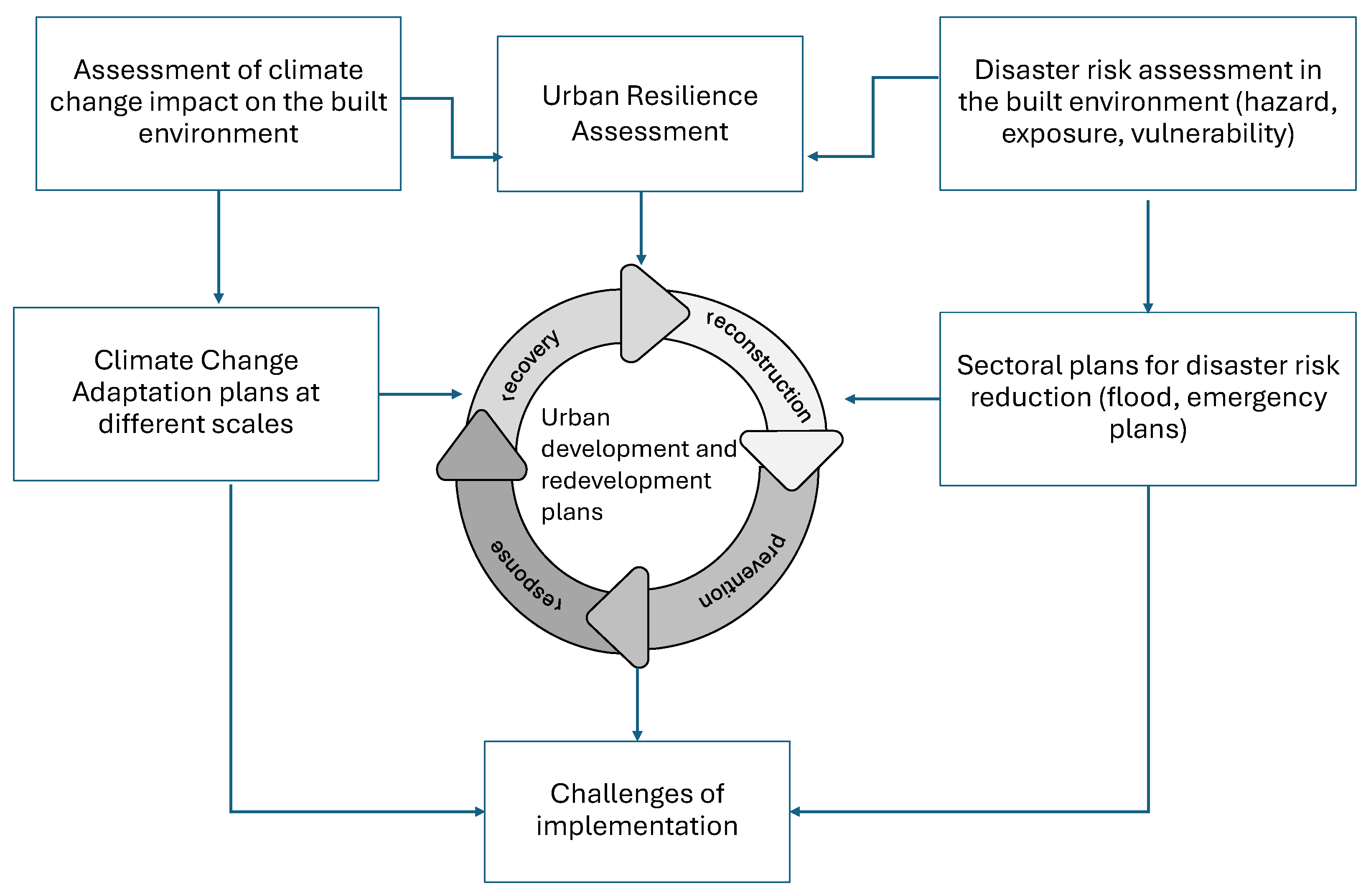

2. Urban Planning for Reducing Risks and Adapting to Climate Change: The Approach to the Review

- Comprehensive risk assessment in and for urban areas, with particular regard to the risk components of exposure and vulnerability to single and multi-hazard conditions,

- Resilience and urban resilience in particular as a concept that can help reconciling until now disjunct policies and provisions for CCA and DRR,

- Urban planning for resilience, addressing the role urban planning plays across the entire timescale of disasters and crises bridging between DRR and CCA,

- Issues inherent in plans implementation due to governance pitfalls and to land property rights.

| The strategy that has been followed here can be considered a hybrid between different types of reviews as classified for example by Cooper [42], Grant et al [22], Peré et al [23]. By relying on literature reviews for topics for which those were available it can be considered an umbrella review. By making an attempt to produce a new conceptualization of the broad problem set for the review, it shares elements of mapping, “critical” and/or “theoretical” review. As for the former, it provides a mapping of literature in different disciplinary domains, from engineering to climate change studies on the specific aspect of urban resilience and risk prevention. As for the latter as defined in Paré et al [23] it makes an attempt to bring the different streams of literature into a conceptual framework. By doing so it acknowledges that there is a mature body of knowledge on the topic of urban prevention, urban resilience which nevertheless would benefit from improved integration of contributions and explicit analysis of interrelationships between them (critical review according to Snyder [21]. |

Authoritative references in DRR & CCA |

Multirisk Exposure and Vulnerability of urban areas | Urban Resilience | Planning for DRR and/or CCA and Linking DRR to CCA | Challenges and obstacles to plans implementation | Illustrative examples |

| Articles and books that have become authoritative references for researchers and practitioners; Books and articles in this category have recorded more than 1000 citations according to GoogleScholar |

Articles, books, reports on the challenges and the available methodologies for assessing risk and multirisk in urban areas | Literature on urban resilience and on resilience more in general with implications for urban areas | Literature on how disaster prevention and management, and on climate impacts adaptation is or can be mainstreamed in land use and urban planning; Literature on the need and opportunities for bridging/linking/connecting CCA and DRR. | Literature on challenges and obstacles to plans implementation in general and more specifically on plans for CCA and disaster prevention and management | Case studies have been mainly drawn from citations of consulted articles and books selected according to the criteria in the previous columns; Some (such as Cologne, Thessalonikki, Barcelona) have been also found while searching literature according to the criteria in the previous columns. |

|

|

Urban vulnerability; vulnerability assessment cities; Exposure to natural hazards/disasters in urban areas/cities; exposed sectors to natural hazards/disasters; Exposed urban areas/ functions; multihazard/ multirisk conditions; multi hazard in urban areas/cities; urban xposure/vulnerability to floods, earthquakes, landslides… |

Urban resilience; resilience of urban systems; communities resilience; resilience of urban infrastructures; operationalization, measurability of resilience | Urban planning for DRR; Urban planning for resilience; climate adaptation cities; Linking DRR to CCA; hazards and climate impacts assessment; Urban planning in flood/earthquakes or seismic/landslides areas |

Implementation of public policies; Implementation obstacles/challenges/failures of CCA in cities ; Obstacles/challenges, failures in delivering/implemeneting urban plans for DRR |

Following the keywords in the previous columns | |

| 20 | 18 | 25 | 30 | 29 | 5 | |

| Searched Databases Reports |

GoogleScholar, Scopus Poljansek, K et al, Science for disaster risk management 2017. Knowing better and losing less, European Commission, DG-JRC; Casajus Valles, A. et al, Science for Disaster Risk Management 2020: acting today, protecting tomorrow, European Commission, DG-JRC |

|||||

3. Assessing Disasters and Climate Change Impacts in Cities

3.1. Open Questions in Assessing Exposure and Vulnerabilities in Cities

3.2. Towards Multi-Hazard and Multi-Risk Assessment

4. Resilience as a Bridging Concept Between DRR and CCA

5. Urban Planning for Resilience

6. Challenges to Implement Plans for Resilience

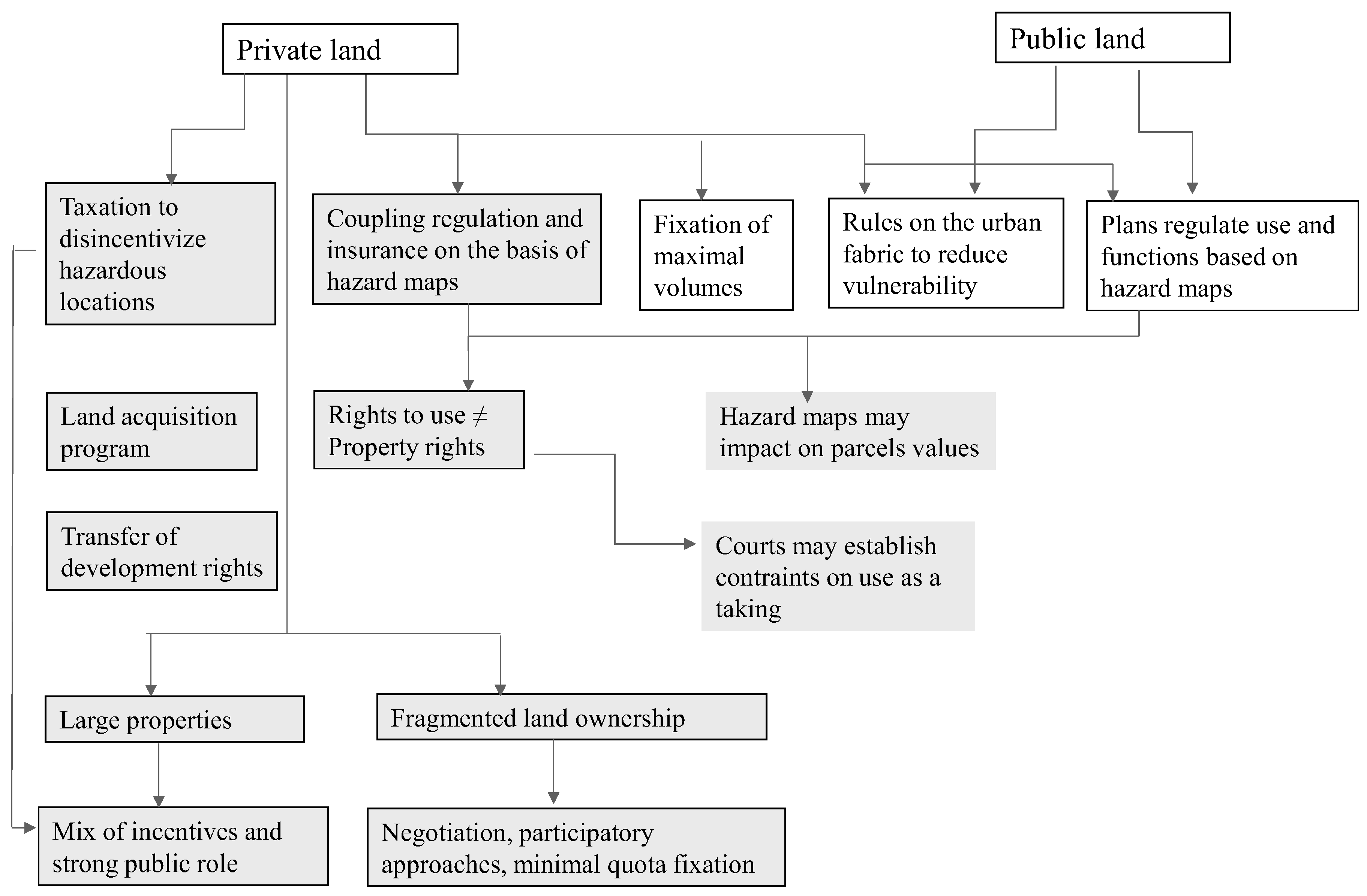

6.1. The Relevance of Land Property Rights Management for Enforcing Urban Plans for Resilience

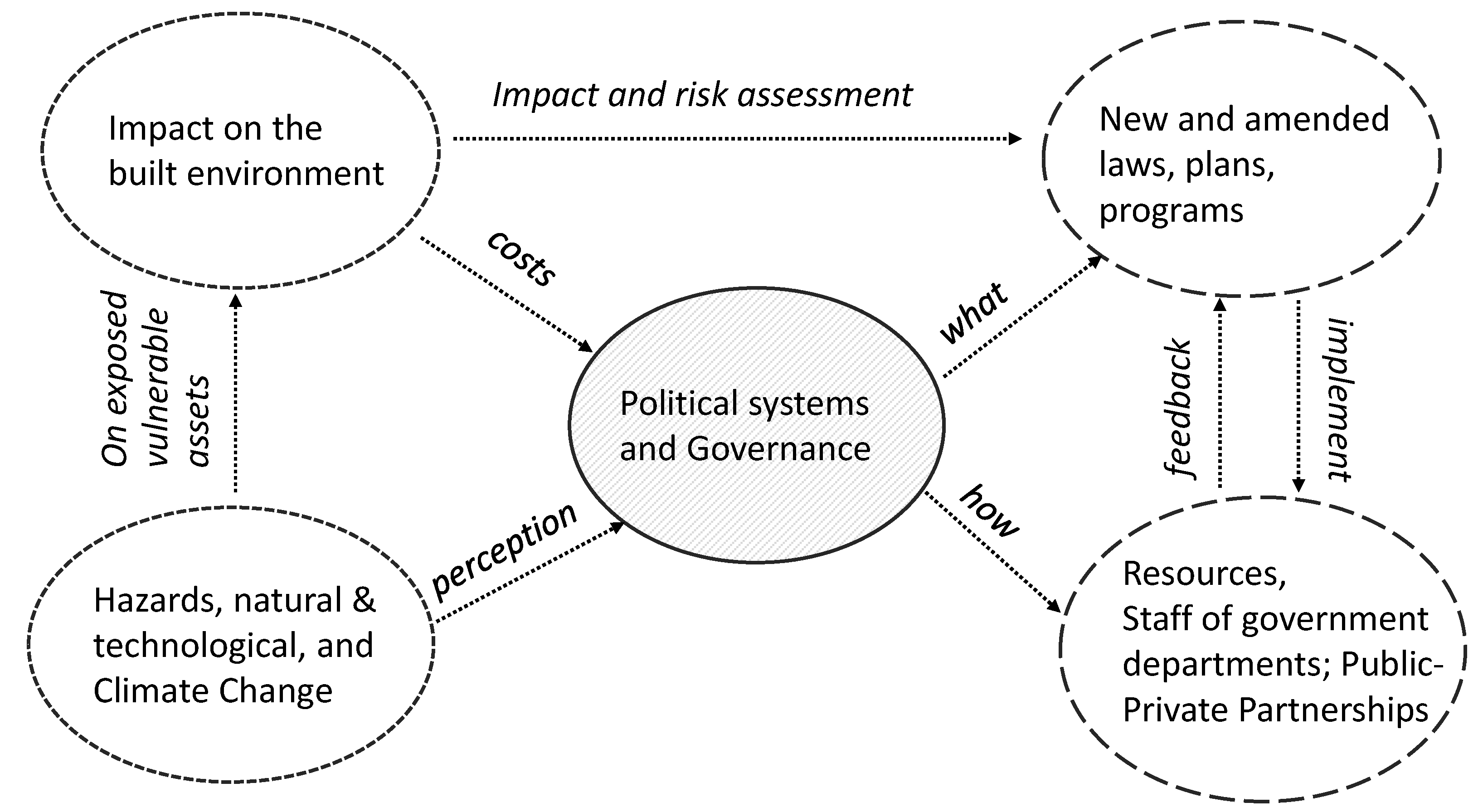

6.2. Governance for Urban Resilience

7. Conclusions

| [1] | See Menoni et al. (2012). Assessing multifaceted vulnerability and resilience in order to design risk-mitigation strategies. Natural hazards, 64 |

| [2] | |

| [3] |

References

- Ratcliffe, J.; Krawczyk, E. Imagineering city futures: The use of prospective through scenarios in urban planning. Futures 2011, 43, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.; Kupers, R.; Mangalagiu, D. How plausibility-based scenario practices are grappling with complexity to appreciate and address 21st century challenges. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2013, 80, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, R.; Selin, C. Plausibility and probability in scenario planning. Foresight 2014, 16, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringland, G. Scenario planning. Managing for the future; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: 1999.

- Wibeck, V.; Eliasson, K.; Neset, T.S. Co-creation research for transformative times: Facilitating foresight capacity in view of global sustainability challenges. Environmental Science & Policy 2022, 128, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayland, R. Strategic foresight in a changing world. Foresight 2015, 17, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daffara, P. Rethinking tomorrow's cities: Emerging issues on city foresight. Futures 2011, 43, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjark, G.; Allam, Z. Strategic Foresight and Futures Thinking in Urban Development: Reframing Planning Perspectives and Decolonising Urban Futures, Future Cities Series: Practical Guidance for innovative, resilient and inclusive Cities of the Future, UN-Habitat, ISOCARP. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, W.; Kilvington, M. Innovative land use planning for natural hazard risk reduction: A consequence-driven approach from New Zealand. International Journal of DRR 2016, 18, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarantelli, E. L. The future is not the past repeated: Projecting disasters in the 21st century from current trends. Journal of contingencies and crisis management 1996, 4, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burby, R. (Ed.) Cooperating with nature. Confronting natural hazards with land-use planning for sustainable communities; Joseph Henry Press: Washington D.C, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, C.; Saperstein, M.; Barbee, D. Community recovery from a major natural disaster. FMHI Publications 1985, 87. [Google Scholar]

- White, G. F. Strategic aspects of urban flood-plain occupance. Journal of the Hydraulics Division 1960, 86, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, M.J.; Kebede, A.S.; König, C.S. The safe development paradox in flood risk management: a critical review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.F.; Kates, R.W.; Burton, I. Knowing better and losing even more: the use of knowledge in hazards management. Global Environmental Change Part B: Environmental Hazards 2001, 3, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit-Boix, A.; Leipold, S. Circular economy in cities: Reviewing how environmental research aligns with local practices. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 195, 1270–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depietri, Y.; McPhearson, T. Changing urban risk: 140 years of climatic hazards in New York City. Climatic Change 2018, 148, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forzieri, G.; Feyen, L.; Russo, S.; Vousdoukas, M.; Alfieri, L.; Outten, S.; Cid, A. Multi-hazard assessment in Europe under climate change. Climatic Change 2016, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aalst, M. K. The impacts of climate change on the risk of natural disasters. Disasters 2006, 30, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, R. Reviewing literature in bioethics research: Increasing rigour in non-systematic reviews. Bioethics 2015, 29, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of business research 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health information & libraries journal 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Paré, G.; Trudel, M.C.; Jaana, M.; Kitsiou, S. Synthesizing information systems knowledge: A typology of literature reviews. Information & management 2015, 52, 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, M.T.; Piracha, A. Natural Disasters—Origins, Impacts, Management. Barretta, R., Agarwal, R., Zur. K., and Ruta, G. (Eds), Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 1101–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhearson, T.; Haasea, D.; Kabischa, N. Advancing understanding of the complex nature of urban systems. Editorial, Ecological Indicators 2016, 70, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Surveyer, A.; Elmqvist, T.; Gatzweiler, F.W.; Güneralp, B.; Parnell, S.; Webb, R. Defining and advancing a systems approach for sustainable cities. Current opinion in environmental sustainability 2016, 23, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Seager, T.P.; Rao, P.S.C.; Convertino, M.; Linkov, I. Integrating risk and resilience approaches to catastrophe management in engineering systems. Risk analysis 2013, 33, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinari, D.; Menoni, S.; Aronica, G.T.; Ballio, F.; Berni, N.; Pandolfo, C.; Minucci, G. Ex post damage assessment: an Italian experience. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischhauer, M.; Greiving, S.; Wanczura, S. D: hazards and spatial planning in Europe; Dortmunder Vertrieb für Bau- und Planungsliteratur, 2006.

- Weichselgartner, J.; Pigeon, P. The role of knowledge in disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 2015, 6, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J. K. Natural hazards research. Manners, I. R., & Mikesell, M. W. (Eds). Perspectives on environment 1974, 311-341.

- Alexander, D. E. Alexander, D. E. A survey of the field of natural hazards and disaster studies. In Carrara, A. &Guzzetti, F. (Eds) Geographical information systems in assessing natural hazards (pp. 1-19); Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, D. The study of natural disasters, 1977–97: Some reflections on a changing field of knowledge. Disasters 1997, 21, 284–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendra, J.; Nigg, J. Engineering and the social sciences: historical evolution of interdisciplinary approaches to hazard and disaster. Engineering Studies 2014, 6, 134–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, I.; Gaillard, J.C.; Lewis, J.; Mercer, J. Learning from the history of disaster vulnerability and resilience research and practice for climate change. Natural Hazards 2016, 82, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, M.; Nguyen, K.H.; Cutter, S.L. Integrated research on disaster risk: Is it really integrated? . International journal of disaster risk reduction 2015, 12, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljansek, K.; et al. Science for disaster risk management 2017.

- Casajus Valles, A.; et al. a: for Disaster Risk Management 2020, 2020.

- Cornish, F. Evidence synthesis in international development: a critique of systematic reviews and a pragmatist alternative. Anthropology & medicine 2015, 22, 263–277. [Google Scholar]

- Montuori, A. The complexity of transdisciplinary literature reviews. Complicity: An International Journal of Complexity and Education 2013, 10.

- Polonioli, A. In search of better science: on the epistemic costs of systematic reviews and the need for a pluralistic stance to literature search. Scientometrics 2020, 122, 1267–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H. M. Organizing knowledge syntheses: A taxonomy of literature reviews. Knowledge in society 1988, 1, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J. A. Megacities and small towns: different perspectives on hazard vulnerability. Global Environmental Change Part B: Environmental Hazards 2001, 3.

- Menoni, S.; Boni, M.P. A systemic approach for dealing with chained damages triggered by natural hazards in complex human settlements. International Journal of DRR 2020, 51, 101751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handmer, J. Natural and anthropogenic hazards in the Sydney sprawl: Is the city sustainable?. Mitchell, J (Ed) Crucibles of hazard : mega-cities and disasters in transition; UN University Press: Tokyo, New York, Paris, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Birkmann, J.; Welle, T. Assessing the risk of loss and damage: exposure, vulnerability and risk to climate-related hazards for different country classifications. International Journal of Global Warming 2015, 8, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbane, C.; et al. Current and innovative methods to define exposure. in K. Poljansek et al., Science for disaster risk management 2017. Knowing better and losing less, European Commission, DG-JRC, 2017; p. 59-69.

- Gunasekera, R.; Ishizawa, O.; Aubrecht, C.; Blankespoor, B.; Murray, S.; Pomonis, A.; Daniell, J. Developing an adaptive global exposure model to support the generation of country disaster risk profiles. Earth-Science Reviews 2015, 150, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotten, R.; Mühlhofer, E.; Chatzistefanou, G.A.; Bachmann, D.; Chen, A.S.; Koks, E.E. Data for critical infrastructure network modelling of natural hazard impacts: Needs and influence on model characteristics. Resilient Cities and Structures 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bono, M.; Mora, M.G. A global exposure model for disaster risk assessment, International Journal of DRR 2014, 10, 442-451.

- Carbonara, S.; Stefano, D. Recupero edilizio, valori immobiliari e declino demografico nell’Abruzzo post-sisma 2009. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Forum of Architecture and Urbanism, Pescara, Italy, November 8-10 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Romao, X.; Pauperio, E. An indicator for post-disaster economic loss valuation of impacts on cultural heritage. International Journal of Architectural Heritage 2021, 15, 678–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaro, G. The Contribution of the Economic Thinking to Innovate DRR Policies and Action. In Galderisi A. and Colucci A. Smart, Resilient and Transition Cities: Emerging Approaches and Tools for A Climate-Sensitive Urban Development; Springer: 2018.

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J.M.; Jato-Espino, D. Analysis of vulnerability assessment frameworks and methodologies in urban areas. Natural Hazards 2020, 100, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgilevich, A.; Räsänen, A.; Groundstroem, F.; Juhola, S. A systematic review of dynamics in climate risk and vulnerability assessments. Environmental Research Letters 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapsell, S.; McCarthy, S.; Faulkner, H.; Alexander, M. Social vulnerability to natural hazards. State of the art report from CapHaz-Net’s WP4. London, 2010.

- Singh, S.R.; Eghdami, M.R.; Singh, S. The concept of social vulnerability: A review from disasters perspectives. International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies 2014, 1, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I.; Wisner, B. At risk: natural hazards, people's vulnerability and disasters; Routledge: 2014.

- Rose, A. Economic resilience to natural and man-made disasters: Multidisciplinary origins and contextual dimensions. Environmental hazards 2007, 7, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S. Global networks, linked cities; Routledge: 2016.

- Hutton, M. Neither passive nor powerless: reframing economic vulnerability via resilient pathways. In Consumer Vulnerability (pp. 46-68); Routledge: 2018.

- Noy, I.; Yonson, R. Economic vulnerability and resilience to natural hazards: A survey of concepts and measurements. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- duPont, I.V.W.; Noy, I. What happened to Kobe? A reassessment of the impact of the 1995 earthquake in Japan. Economic Development and Cultural Change 2015, 63, 777–812. [Google Scholar]

- Mili, R.R.; Hosseini, K.A.; Izadkhah, Y.O. Developing a holistic model for earthquake risk assessment and disaster management interventions in urban fabrics. International journal of DRR 2018, 27, 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Carreño, M.L.; Cardona, O.D.; Barbat, A. Urban seismic risk evaluation: a holistic approach. Natural Hazards 2007, 40, 137–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, A.; Argyroudis, S.; Pitilakis, K. Systemic seismic risk assessment of urban healthcare system considering interdependencies to critical infrastructures. International Journal of DRR 2024, 103, 104304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curt, C.; Tacnet, J.M. Resilience of critical infrastructures: Review and analysis of current approaches. Risk Analysis 2018, 38, 2441–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, A.; Limongi, G. A comprehensive assessment of exposure and vulnerabilities in multi-hazard urban environments: A key tool for risk-informed planning strategies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, D.E.; Pitman, S.J.; Byun, D.S. Earthquakes, coasts… and climate change? Multi-hazard opportunities, challenges and approaches for coastal cities. Journal of coastal research 2020, 95, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showalter, P.; Fran Myers, M. Natural disasters as the cause of technological emergencies: a review of the decade 1980-1989; Natural Hazard Research and Applications Center, University of Colorado: Boulder, Colorado, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, A.M.; Okada, N. Methodology for preliminary assessment of Natech risk in urban areas. Natural Hazards 2008, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santella, N.; Steinberg, L.J.; Sengul, H. Petroleum and hazardous material releases from industrial facilities associated with Hurricane Katrina. Risk Analysis: An International Journal 2010, 30, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Cruz, A.M.; Tzioutzios, D. Extracting Natech reports from large databases: development of a semi-intelligent Natech identification framework. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 2020, 11, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.C.; Malamud, B.D. Reviewing and visualizing the interactions of natural hazards. Reviews of geophysics 2014, 52, 680–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.C.; Malamud, B.D. Hazard interactions and interaction networks (cascades) within multi-hazard methodologies. Earth System Dynamics 2016, 7, 659–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zschau, J. 2.5 Where are we with multihazards, multirisks assessment capacities? Qualitative and quantitative approaches to risk assessment, In Poljansek K., M. Marín Ferrer, T. De Groeve, I. Clark (eds.) “Science for disaster risk Science for disaster risk management 2017. Knowing better and losing less, European Commission, DG-JRC: 2017.

- van Westen, C.; Woldai, T. The Riskcity training package on multi-hazard risk assessment. International Journal of Applied Geospatial Research (IJAGR) 2012, 3, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünthal, G.; Thieken, A.H.; Schwarz, J.; Radtke, K.S.; Smolka, A.; Merz, B. Comparative risk assessments for the city of Cologne–storms, floods, earthquakes. Natural Hazards 2006, 38, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, M.P.; Faiella, A.; Gazzola, V.; Pergalani, F. A multi-hazard and multi-risk assessment methodological approach to support Civil Protection planning in wide areas. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2025, 119, 105343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, A.; Colucci, A. Smart, Resilient and Transition Cities: Emerging Approaches and Tools for A Climate-Sensitive Urban Development; Elsevier: 2019.

- Vogel, C.; Susanne, C.M.; Roger, E.K.; Geoffrey, D.D. Linking vulnerability, adaptation, and resilience science to practice: pathways, players and partnerships1. In Integrating science and policy (pp. 97-127); Routledge: 2012.

- Glaas, E.; Jonsson, A.; Hjerpe, M.; Andersson-Skold, Y. Managing climate change vulnerabilities: formal institutions and knowledge use as determinants of adaptive capacity at the local level in Sweden, Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability 2010, 15, 525-539.

- Thomalla, F.; Downing, T.; Spanger-Siegfried, E.; Han, G.; Rockström, J. Reducing hazard vulnerability: towards a common approach between DRR and climate adaptation. Disasters 2006, 30, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.; Stevens, S.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.; Pfefferbaum, R. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graveline, M.H.; Germain, D. Disaster risk resilience: Conceptual evolution, key issues, and opportunities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 2022, 13, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosovac, A.; Logan, T.M. Resilience: lessons to be learned from safety and acceptable risk. Journal of safety science and resilience 2021, 2, 253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Manyena, S. B. The concept of resilience revisited. Disasters 2006, 30, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S.; Shaw, K.; Haider, L.J.; Quinlan, A.E.; Peterson, G.D.; Wilkinson, C.; Davoudi, S. Resilience: a bridging concept or a dead end? “Reframing” resilience: challenges for planning theory and practice interacting traps: resilience assessment of a pasture management system in Northern Afghanistan urban resilience: what does it mean in planning practice? Resilience as a useful concept for CCA? The politics of resilience for planning: a cautionary note: edited by Simin Davoudi and Libby Porter. Planning theory & practice 2012, 13, 299–333. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O'Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Von Winterfeldt, D. A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities. Earthquake spectra 2003, 19, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S.; Walker, B.; Anderies, J.M.; Abel, N. From metaphor to measurement: resilience of what to what? . Ecosystems 2001, 4, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.H.; Holling, C.S. (Eds.) . Panarchy: understanding transformations in human and natural systems; Island press: 2002.

- Rus, K.; Kilar, V.; Koren, D. Resilience assessment of complex urban systems to natural disasters: A new literature review. International journal of DRR 2018, 31, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. A critical review of selected tools for assessing community resilience. Ecological indicators 2016, 69, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, C.I.; Wiesmann, U.; Rist, S. An indicator framework for assessing livelihood resilience in the context of social–ecological dynamics. Global Environmental Change 2014, 28, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.G.; Williams, P.R. A systems approach to natural disaster resilience. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory 2016, 65, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.J.G.; Gonçalves, L.A.P.J. Urban resilience: A conceptual framework. Sustainable Cities and Society 2019, 50, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, J.; Kernaghan, S.; Luque, A. A systems approach to meeting the challenges of urban climate change. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 2012, 4, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.; Gurtner, Y.; Firdaus, A.; Harwood, S.; Cottrell, A. Land use planning for DRR and CCA: Operationalizing policy and legislation at local levels. International journal of disaster resilience in the built environment 2016, 7, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, A. O. Natural disasters and supply chain disruption in Southeast Asia; NeilsonJournals Publishing: 2018.

- Crosta, G.B.; Dal Negro, P.J.N.H. Observations and modelling of soil slip-debris flow initiation processes in pyroclastic deposits: the Sarno 1998 event. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2003, 3, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C. Towards a quantifiable measure of resilience. IDS Working Papers 2013, 2013, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xu, L.; Zhao, D.; Xu, T.; Lei, P. A new model for describing the urban resilience considering adaptability, resistance and recovery. Safety science 2020, 128, 104756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhreasai, A.N.; Persson, E.; Measuring Resilience. A Guide to Tracking Progress, ARUP. 2023. Available online: https://www.arup.com (accessed on day month year).

- Correa, E.; Ramírez, F.; Sanahuja, H. Populations at Risk of Disaster: A Resettlement Guide; The World Bank: Washington, DC, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, D.; Ramirez-Marquez, J.E. Generic metrics and quantitative approaches for system resilience as a function of time. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2012, 99, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Quintero, C.; Avila-Foucat, V.S. Operationalization and measurement of social-ecological resilience: a systematic review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkov, I.; Eisenberg, D.A.; Bates, M.E.; Chang, D.; Convertino, M.; Allen, J.H.; Seager, T.P. Measurable resilience for actionable policy. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, R.J.; Nicholls, R.J.; Thomalla, F. Resilience to natural hazards: How useful is this concept? . Global environmental change part B: environmental hazards 2003, 5, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox-Lent, C.; Linkov, I. Resilience matrix for comprehensive urban resilience planning. Resilience-Oriented Urban Planning: Theoretical and Empirical Insights 2018, 29-47.

- Cariolet, J.M.; Vuillet, M.; Diab, Y. Mapping urban resilience to disasters–A review. Sustainable Cities and Society 2019, 51, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, A. , D. A New Framework for a Resilience-Based Disaster Risk Management. In Handbook of DRR for Resilience: New Frameworks for Building Resilience to Disasters (pp. 131-156); Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jabareen, Y.; Jabareen, Y. The risk city resilience trajectory. The Risk City: Cities Countering Climate Change: Emerging Planning Theories and Practices around the World 2015, 137-159.

- Strunz, S. Is conceptual vagueness an asset? Arguments from philosophy of science applied to the concept of resilience. Ecological economics 2012, 76, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Peek, L.; Tobin, J.; Adams, R.M.; Wu, H.; Mathews, M.C. A framework for convergence research in the hazards and disaster field: The natural hazards engineering research infrastructure CONVERGE facility. Frontiers in Built Environment 2020, 6, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godschalk, D. R. Urban hazard mitigation: Creating resilient cities. Natural hazards review 2003, 4, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmutina, K.; Bosher, L.; Coaffee, J.; Rowlands, R. Towards integrated security and resilience framework: a tool for decision-makers. Procedia Economics and Finance 2014, 18, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Miner, T.W.; Stanton-Geddes, Z. (Eds.) . Building urban resilience: principles, tools, and practice; World Bank Publications: 2013.

- UNDRR. Implementation guide for land use and urban planning. Words into Action, UN, 2020. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/words-into-action/implementation-guide-land-use-and-urban-planning (accessed on day month year).

- Wamsler, C. ‘Planning ahead': Adapting settlements before disasters strike. In Hazards and the Built Environment (pp. 318-354); Routledge: 2008.

- Shaw, R. Post disaster recovery: Issues and challenges. Disaster recovery: Used or misused development opportunity, in Shaw (ed) Post disaster recovery: Issues and challenges; Springer: 2014; pp. 1-13.

- March, A.; Kornakova, M. (eds). Urban planning for disaster recovery. Butterworth Heinemann; Elsevier: 2017.

- Vale, L.J. , Campanella T.J. The Resilient City. How modern city recover form disaster; Oxford University Press: NY, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, M.; Salvati, L. ‘Interrupted’ landscapes: post-earthquake reconstruction in between Urban renewal and social identity of local communities. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Brink, E.; Rivera, C. Planning for climate change in urban areas: from theory to practice. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 50, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Mitchell, C.L. Weathering the storm: The politics of urban CCA planning. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 2017, 49, 2619–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Solecki, W. Hurricane Sandy and adaptation pathways in New York: Lessons from a first-responder city. Global Environmental Change 2014, 28, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, D.; Chandrasekhar, D.; Xiao, Y. A region recovers: Planning for resilience after superstorm Sandy. Journal of Planning Education and Research 2023, 43, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, K.; Rickards, L.; Wakefield, S. Becoming non-commensurable: synthesis, design, and the politics of urban experimentation in post-Superstorm Sandy New York. S: Sustainability, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Francini, M.; Gaudio, S.; Palermo, A.; Viapiana, M.F. A performance-based approach for innovative emergency planning, Sustainable Cities and Society 2020, 53, 101906.

- Gonzalez-Mathiesen, C.; Ruane, S.; March, A. Integrating wildfire risk management and spatial planning–A historical review of two Australian planning systems. International Journal of DRR 2021, 53, 101984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francini, M.; Palermo, A.; Viapiana, M.F. Il piano di emergenza nell'uso e nella gestione del territorio: atti del convegno scientifico Società italiana degli urbanisti-Università della Calabria, Rende (CS), 22-23 novembre 2019. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dolce, M.; Speranza, E.; Bocchi, F.; Conte, C. The method I. OPà. CLE for the formulation and calculation of structural operational efficiency indices for the assessment of emergency limit conditions., Proceedings of Anidis Pistoia 2017, 2-13.

- Galderisi, A. , Setti G., Tognon A. Disaster Recovery Reform and Resilience. In DRR for Resilience. In DRR for Resilience: Disaster and Social Aspects; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Finucane, M.L.; Acosta, J.; Wicker, A.; Whipkey, K. Short-term solutions to a long-term challenge: Rethinking disaster recovery planning to reduce vulnerabilities and inequities. International journal of environmental research and public health 2020, 17, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, L.J.; Campanella, T.J. (Eds.) . The resilient city: How modern cities recover from disaster; Oxford University Press: 2005.

- Edgington, D. W. Reflections on the Hanshin Earthquake of 1995 and the Reconstruction of Kobe, Japan. P. Daly and RM Feener (eds) 2016, 108–40. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, P.; Mahdi, S.; McCaughey, J.; Mundzir, I.; Halim, A.; Srimulyani, E. Rethinking relief, reconstruction and development: Evaluating the effectiveness and sustainability of post-disaster livelihood aid. International Journal of DRR 2020, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horney, J.; Dwyer, C.; Aminto, M.; Berke, P.; Smith, G. Developing indicators to measure post-disaster community recovery in the United States. Disasters 2017, 41, 124–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Olshansky, R.B. The theory and practice of building back better. Journal of the American Planning Association 2014, 80, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, M.; Kornhuber, K.; Kruczkiewicz, A. Enhanced urban adaptation efforts needed to counter rising extreme rainfall risks. NPJ Urban Sustainability 2022, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, E.; Boyd, E.; Otto, F. Stop blaming the climate for disasters. Communications Earth & Environment 2022, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahsen, M.; Ribot, J. Politics of attributing extreme events and disasters to climate change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 2022, 13, e750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa do Lago, A.; Sánchez Chaparro, T.; Lumbreras, J. A Decade of Climate Action and the Mission towards Climate Neutrality and Adaptation in European Cities: Delivering Urban Transformations? Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. SWD, Overview of Natural and Man Made Hazards. 2020. Available online: https://op.europa.

- Rentschler, J.; Avner, P.; Marconcini, M.; Su, R.; Strano, E.; Vousdoukas, M.; Hallegatte, S. Global evidence of rapid urban growth in flood zones since 1985. Nature 2023, 622, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Sullivan, F.; Mell, I.; Clement, S. Novel solutions or rebranded approaches: evaluating the use of nature-based solutions (NBS) in Europe. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 2020, 2, 572527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olazabal, M.; De Gopegui, M.R. Adaptation planning in large cities is unlikely to be effective. Landscape and Urban Planning 2021, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, A.; Crivello, S.; Haupt, W. Urban resilience as new ways of governing: the implementation of the 100 Resilient Cities initiative in Rome and Milan. Risk and Resilience: Socio-Spatial and Environmental Challenges 2020, 113-136.

- Hölscher, K.; Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Loorbach, D. Tales of Transforming Cities: Transformative Climate Governance Capacities in New York City, U. S. and Rotterdam, Netherlands. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 231, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reckien, D.; Salvia, M.; Heidrich, O.; Church, J.M.; Pietrapertosa, F.; De Gregorio-Hurtado, S.; Dawson, R. How are cities planning to respond to climate change? Assessment of local climate plans from 885 cities in the EU-28. Journal of cleaner production 2018, 191, 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddin, S. Resilience resistance: The challenges and implications of urban resilience implementation. Cities 2020, 103, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, T. Clumsy floodplains: Responsive land policy for extreme floods; Routledge: 2016.

- Platt, R. H. Land Use and Society: Fundamentals and Issues. Land Use and Society: Geography, Law, and Public Policy 2014, 13-39.

- Caron, C.; Menon, G.; Kuritz, L. Land tenure & disasters. USAID Issue brief. 2014.

- Hepperle, E.; Dixon-Gough, R.; Mansberger, R.; Paulsson, J.; Hernik, J.; Kalbro, T. (Eds.) . Land Development Strategies: Patterns, Risks, and Responsibilities Publisher: vdf Hochschulverlag AGEditor: Erwin Hepperle, Hans Lenk. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Handmer, J. W. Flood policy reversal in Australia. Disasters 1985, 9, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.J.; Deyle, R.E. Governing land use in hazardous areas with a patchwork system. In Burby R.J. (ed) Cooperating with nature: Confronting natural hazards with land-use planning for sustainable communities, 1998; pp 57-82.

- Platt, R.; Dawson, A. The taking issue and the regulation of hazardous areas, Natural Hazards Research Working Paper n. 95, Natural Hazards Research and Applications Information Center, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado, Boulder, 97. 19 June.

- Raška, P.; Bezak, N.; Ferreira, C.S.; Kalantari, Z.; Banasik, K.; Bertola, M.; Hartmann, T. Identifying barriers for nature-based solutions in flood risk management: An interdisciplinary overview using expert community approach. Journal of environmental management 2022, 310, 114725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterman, R.; Pellach, C. Regulating coastal zones: International perspectives on land management instruments (p. 456); Taylor & Francis: 2021.

- Mitchell, D.; Myers, M.; Grant, D. Land Valuation: Key Tool for Disaster Risk Management. Land Tenure Journal 2014, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, R. H. Disasters and democracy: The politics of extreme natural events; Island Press: 2012.

- Hooijer, A.; Klijn, F.; Pedroli, G.B.M.; Van Os, A.G. Towards sustainable flood risk management in the Rhine and Meuse river basins: synopsis of the findings of IRMA-SPONGE. River research and applications 2004, 20, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burby, R.J.; Dalton, L.C. Plans can matter! Public administration review 1994, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills Jr, R.M.; Schleicher, D. Building Coalitions Out of Thin Air: Transferable Development Rights and “Constituency Effects” in Land Use Law. Journal of Legal Analysis 2020, 12, 79–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, A.M.; Stewart, J.L.; Jackson, C.; White, J.T. Ownership diversity and fragmentation: A barrier to urban centre resilience. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 2023, 50, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavovic, B.C.; Saunders, W.S.A.; Becker, J.S. Land-use planning for natural hazards in New Zealand: the setting, barriers, ‘burning issues’ and priority actions. Natural hazards 2010, 54, 679–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, D.W.; Clark, W.C.; Alcock, F.; Dickson, N.M.; Eckley, N.; Guston, D.H.; Mitchell, R.B. Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 2003, 100, 8086–8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, L.; Schueller, L.A.; Scolobig, A.; Marx, S. Stakeholder solutions for building interdisciplinary and international synergies between CCA and DRR. International journal of DRR 2020, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Fioretti, C.; Pertoldi, M.; Busti, M.; Van Heerden, S. (Eds.) Handbook of Sustainable Urban Development Strategies, EUR 29990 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2020, JRC118841.

- Djalante, R. Adaptive governance and resilience: the role of multi-stakeholder platforms in DRR. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2012, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi, G.; Bobbitt, P. Tragic choices; WW Norton &, Co. 1978.

- Soltesova, K.; Brown, A.; Dayal, A.; Dodman, D. Community participation in urban adaptation to climate change: Potential and limits for community-based adaptation approaches. In Community-Based Adaptation to Climate Change (pp. 214-225); Routledge: 2014.

- Cloutier, G.; Joerin, F.; Dubois, C.; Labarthe, M.; Legay, C.; Viens, D. Planning adaptation based on local actors’ knowledge and participation: a climate governance experiment. Climate Policy 2015, 15, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.; Edelenbos, J.; van Buuren, A. Space for the River Governance experiences with multifunctional river flood management in the US and Europe; IWA Publishing: 2012.

- Wamsler, C.; Alkan-Olsson, J.; Björn, H.; Falck, H.; Hanson, H.; Oskarsson, T.; Zelmerlow, F. Beyond participation: when citizen engagement leads to undesirable outcomes for nature-based solutions and CCA. Climatic Change 2020, 158, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, M.T.; Schwarze, R. Sequential Disaster Forensics: A case study on direct and socio-economic impacts. Sustainability 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Smith, A.; Alcántara-Ayala, I.; Burton, I.; Lavell, A. Forensic Investigations of Disasters (FORIN): a conceptual framework and guide to research (IRDR FORIN Publication No. 2); Integrated Research on Disaster Risk: Beijing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Duy, P.; Tight, M.; Chapman, L.; Linh, P.; Thuong, L. Increasing vulnerability to floods in new development areas: evidence from Ho Chi Minh City. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 2017, 10, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics of the review | Categories |

| Focus | Practices or applications (to urban planning) |

| Goal | Identification of central issues (according to the proposed framing) |

| Pespective | Espousal of a position |

| Coverage | Central or Pivotal (considering the authoritative references) |

| Organisation | Conceptual |

| Audience | Scholars (urban planners and experts in disaster and climate change studies), practitioners, and policy makers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).