1. Introduction

Lightweight concrete has been the most popular building material for constructing various civil infrastructure projects. In general, more than ten billion tons of concrete is produced annually which consist of natural aggregate such as crushed rock, fine sand, and gravel [

1,

2]. Construction sector contributes substantially to society and economic development by improving well-being and the quality of people’s life [

3,

4,

5]. The construction industry significantly impacts the environment, accounting for a considerable portion of natural resource depletion. The current trend in the construction industry is towards using alternative renewable construction materials. Therefore, growing awareness has been introduced to the various surface modification methods of the renewable aggregate to minimise the impact towards resources, thereby reducing environmental impact to produce environmentally friendly concrete [

6,

7,

8,

9].

The utilisation of lightweight crushed oil palm shell (OPS) to substitute conventional coarse aggregates had been initiated since early 1984 in Malaysia by Abang [

10]. The use of lightweight plant-based aggregate in concrete can provide possible solutions to mitigate the depletion problem of natural resources. Recently, many researchers have utilised renewable and recycled lightweight plant-based aggregate (LWPA) such as wood, palm kernel shells, peach shells, mussel shells, coconut shells, bamboo, and apricot shells to produce lightweight concrete [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. The advances of incorporating plant-based aggregate in lightweight concrete is to further reduce the concrete self-weight, alleviating the damage caused to the natural environment, and saving construction costs [

16,

17]. Therefore, the utilization of unwanted wastes from agricultural activities such as OPS in the concrete can provide a sustainable development of construction in contributing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions issue. Many scientists have found that the utilization of effective surface modification methods on plant-based aggregates can produce better concrete quality [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The modification techniques consist of carbonization, particle shaping, microwave heating and soaking of chemical solution to enhance the strengthening of the adhered shell.

According to Malaysia Palm Oil Council (MPOC), it has reported that Malaysia is one of the largest producers of crude palm oil and expected to export approximately 0.19 billion tons of crude palm oil each year which is 12% of global oil palm [

24]. Indonesia and Malaysia are responsible for supplying of the global oil palm and fulfil 34% of global vegetable oil demand [

25]. In Malaysia, most of the oil palm fruit can be categorized into tenera and dura [

26]. The total export of oil palm products has achieved more than RM 67.5 million and contributed 37.7% of Malaysia’s agricultural GDP. It has been reported that 2.7 million hectares of land areas are covered with oil palm plantation and more new oil palm plantations areas are introduced and developed within the states [

27]. The production of crude palm oil (CPO) is estimated to reach 5.5 million and increases every year. With the demand of palm oil, a large amount of oil palm by-product wastes is produced. From the recent studies, many scientists have investigated oil palm shell as bio-based lightweight aggregate to produce green lightweight concrete [

28,

29,

30]. Lightweight concrete can be produced by using variety of materials such as lightweight fine and coarse aggregate as well as bubble foamed [

31,

32,

33]. Some of the lightweight aggregate used are perlites, pumice and scoria. Furthermore, lightweight foamed concrete is produced by adding foaming agent in which up to 75% of air-voids can be entrapped in mortar mix. According to Loh et al., one of the most popular techniques to produce lightweight concrete is to incorporate lightweight aggregate [

34]. From the previous study, high strength lightweight concrete incorporated plant-based aggregate is generally obtained a compressive strength within the range of 40-54 MPa and oven-dry density less than 1900 kg/m

3 [

26].

Most current research on OPS lightweight concrete focused on the investigation of their surface modification with the heat-treatment and grout spray coating method [

7,

22]. However, no information is available regarding the pre-soaking treatment techniques on plant-based aggregates. Therefore, implementation of innovative techniques on plant-based aggregate with the consideration of effective methods to mitigate environmental issue should be strongly recommended. Thus, the influences of pre-soaking techniques with various w/c ratios formulation (0.6, 0.8, 1.0 and 1.2) on dura and tenera plant-based aggregates in terms of mechanical and durability properties will be investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

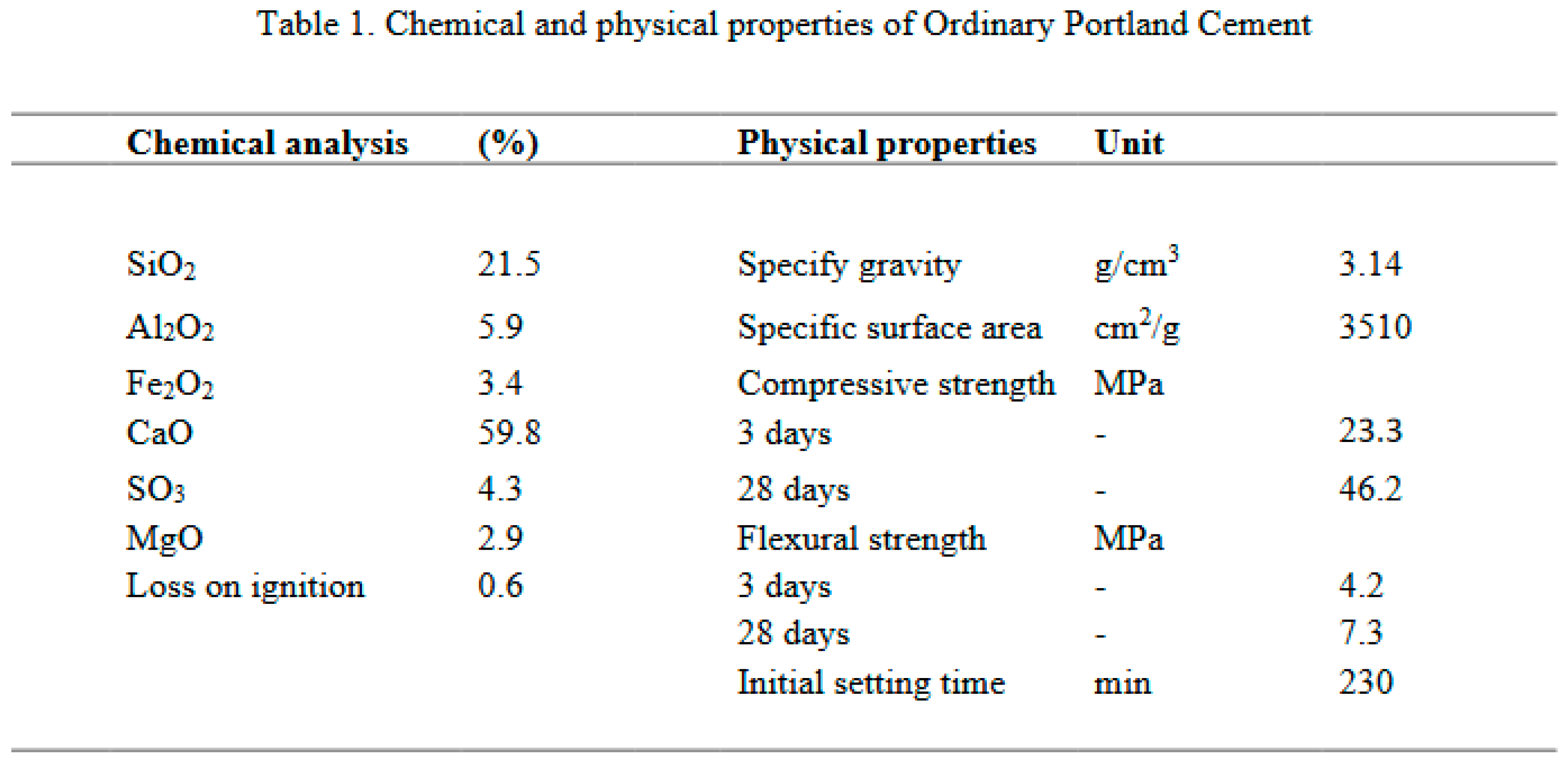

Locally produced Type I 43 grade Ordinary Portland Cement conforming Malaysia Standard and 5% of silica fume containing densified class pozzolana was adopted to be supplementary cementitious. The chemical and physical compounds of the cement are provided in

Table 1. The average particle size of OPC and SF are 25 µm and 15 µm, with the specific gravity of 3510 cm

2/g and 2.10 g/cm

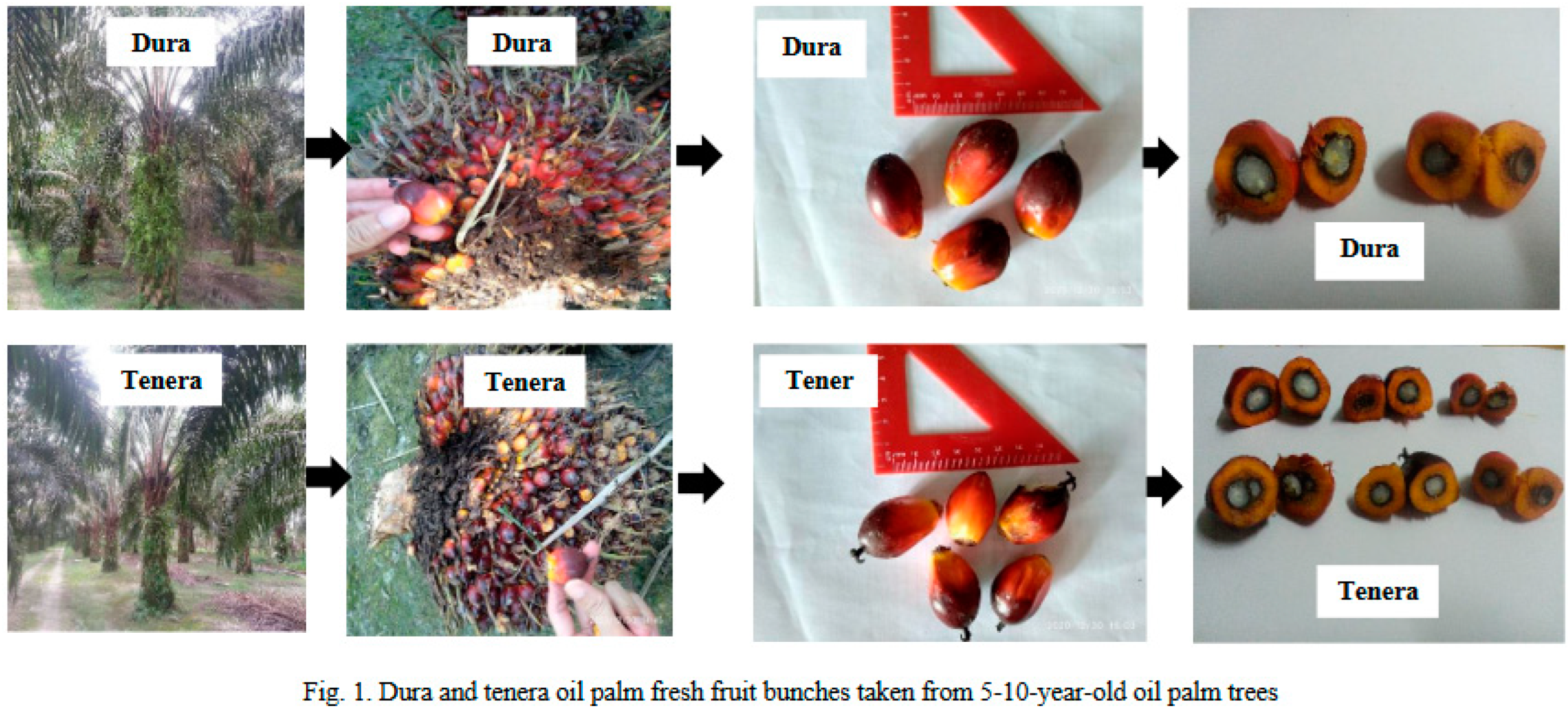

3 respectively. In this study, portable water and polycarboxylic ether superplastisizer were used to prepare for all the concrete mixtures. Natural river sand and crushed dura shell (DS) and tenera shell (TS) particles having an average size of 9.5 mm was utilized. Shafigh et al. [

35] found that the 9.5 mm maximum size of OPS aggregate had showed increment of 6% compressive strength compared to 12.5 mm. Therefore, 9.5 mm maximum size of DS and TS is recommended, as shown in

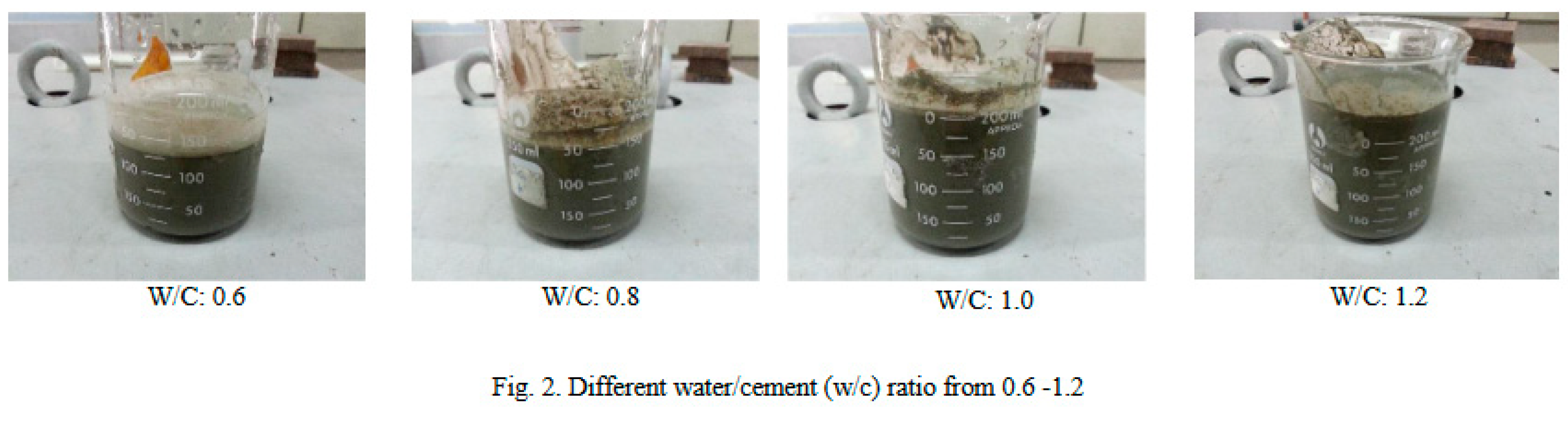

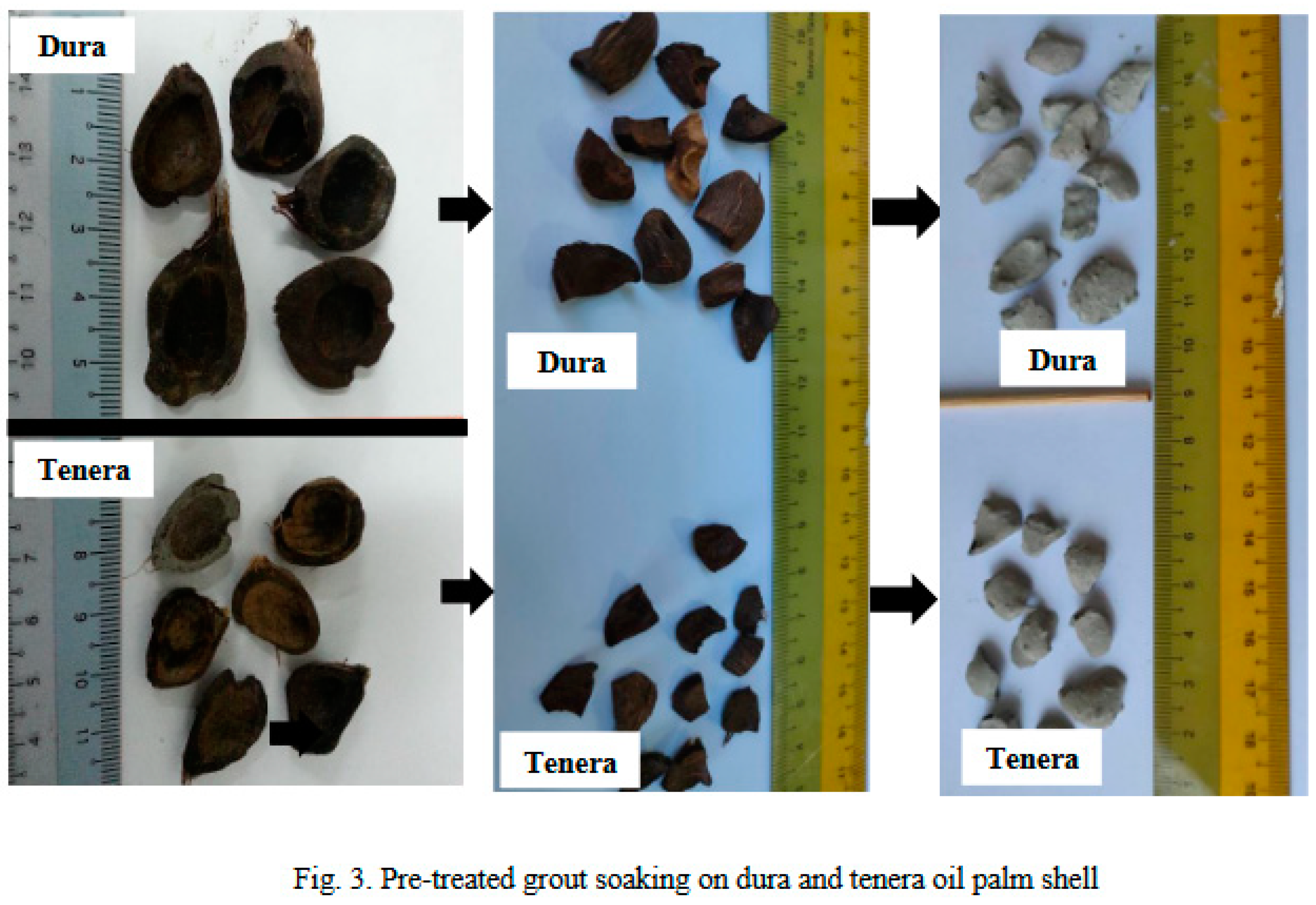

Figure 1. The grout soaking techniques with different w/c formulations (0.6, 0.8, 1.0 and 1.2) will be applied on DS and TS surface until the coats are evenly distributed. After 24 hours, all the dried DS and TS will be used as coarse aggregates for mixtures, as shown in

Figure 2 and

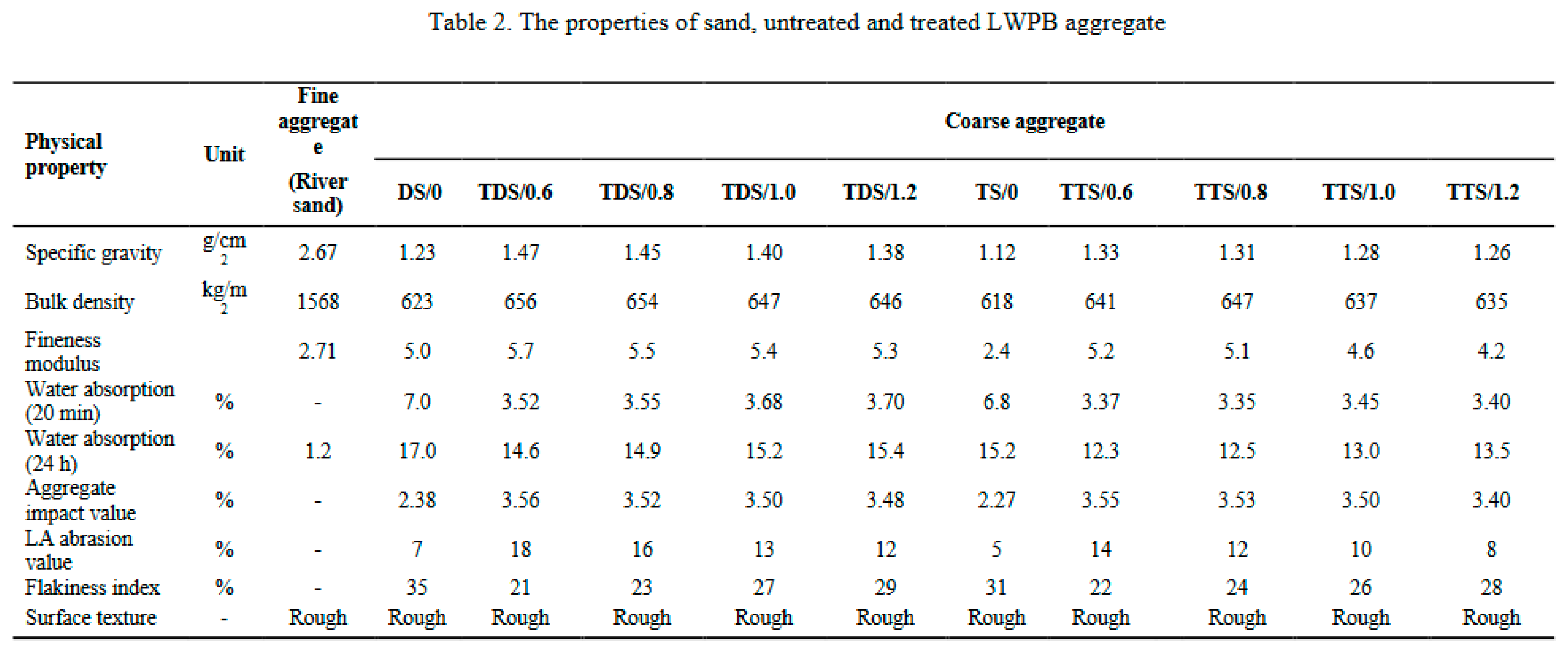

Figure 3. The physical properties of river sand and coated DS and TS aggregates, as shown in

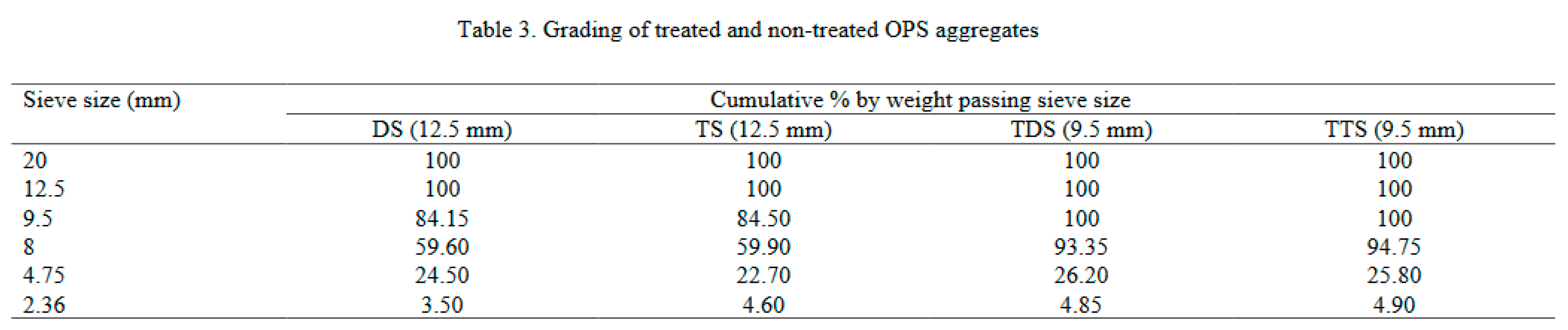

Table 2. Furthermore, the average grading of coated and uncoated DS and TS aggregates as illustrated in

Table 3.

2.2. Concrete sample preparation and methods of testing

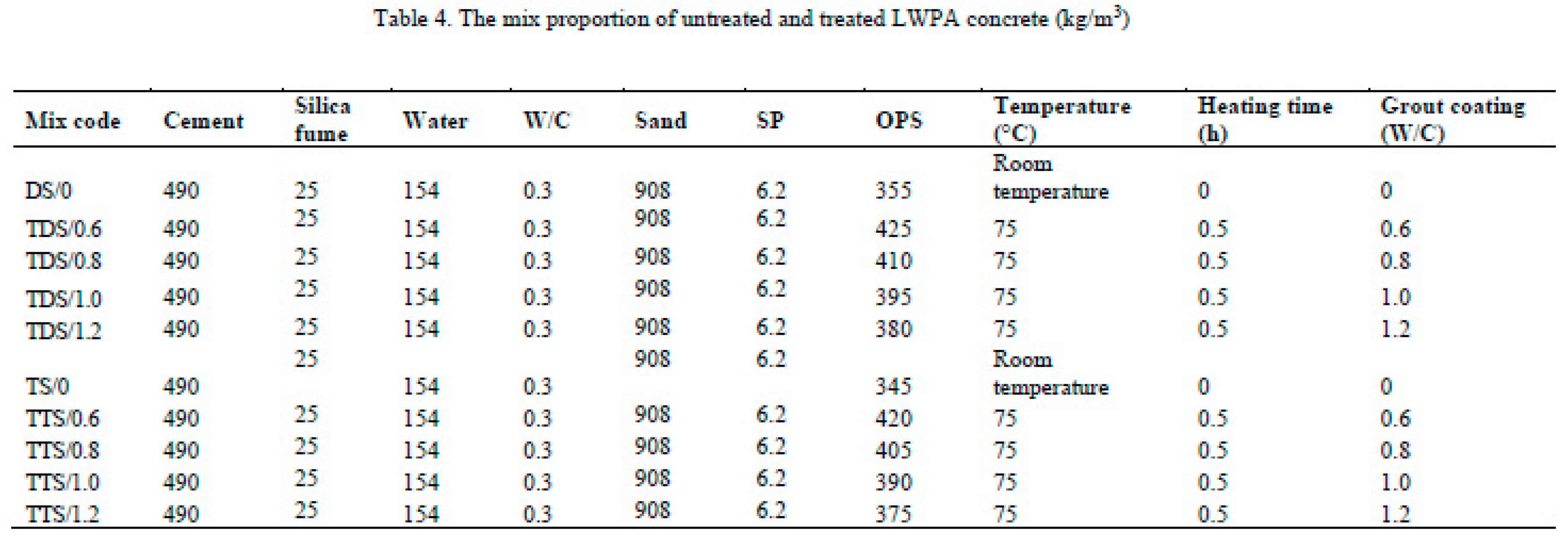

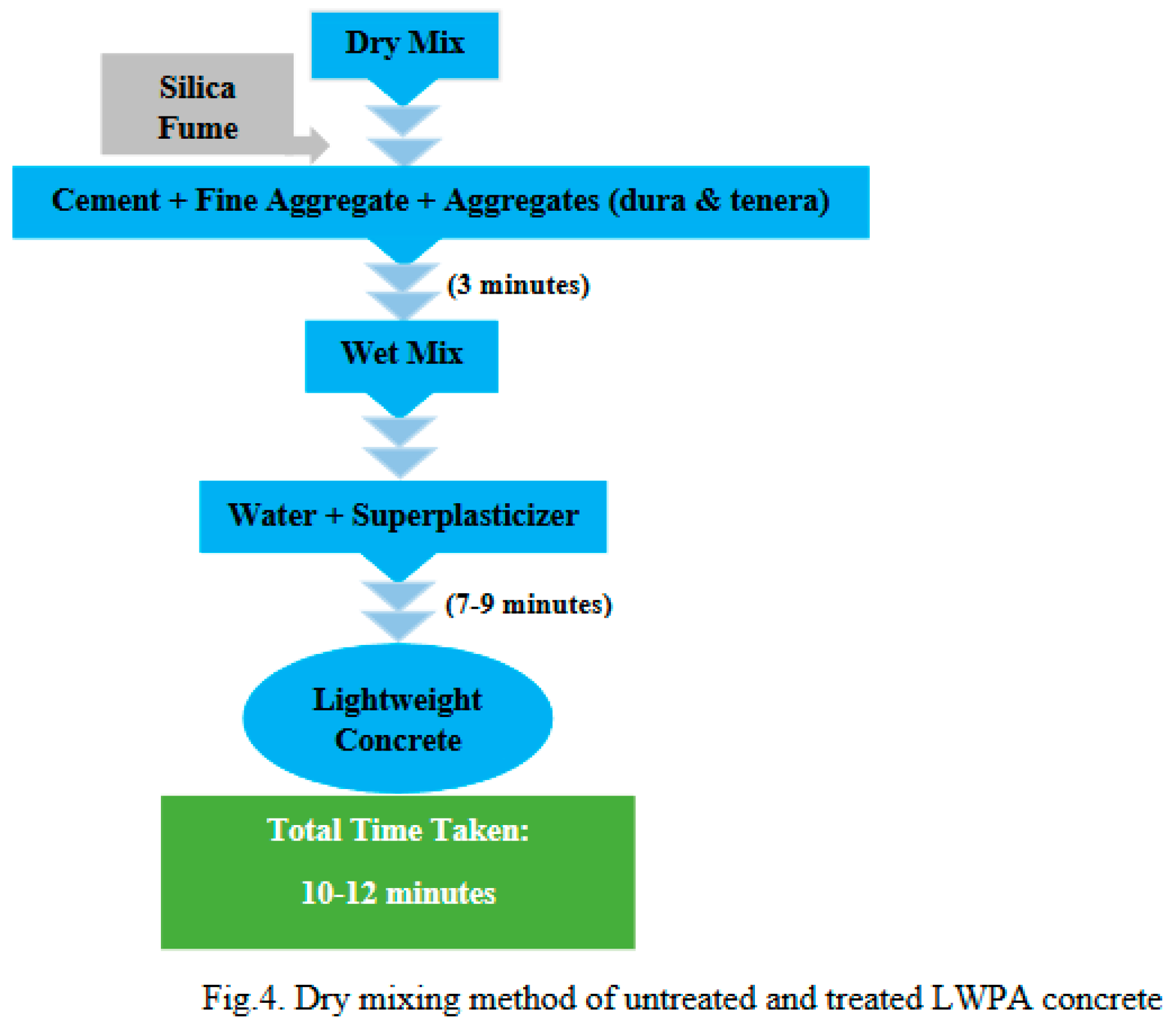

The detailed mix proportion of untreated and treated LWPA concrete used, as illustrated in

Table 4. In addition, the mixing method of untreated and treated LWPA concrete was performed, as shown in

Figure 4. The fresh concrete was put in steel molds, which have been properly lubricated before placing. The 100 x 100 x 100 mm cube, 100 mm x 200 mm cylinder and 150 mm x 300 mm cylindrical specimens were used to find the compressive strength, splitting tensile strength and young modulus elasticity, and all the concrete specimens are kept in a water tank for a duration of 1st, 3rd, 7th, 28th and 56th days for curing. Fresh properties of concrete were examined immediately after mixing. Besides, different tests are performed according to BS EN 12390-3 [

36], BS EN 12390-6 [

37], BS EN 12390-13 [

38] respectively by using compression machine with the capacity up to 3000 kN. Furthermore, water absorption was examined for all the specimens at 28 days.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Fresh properties and densities

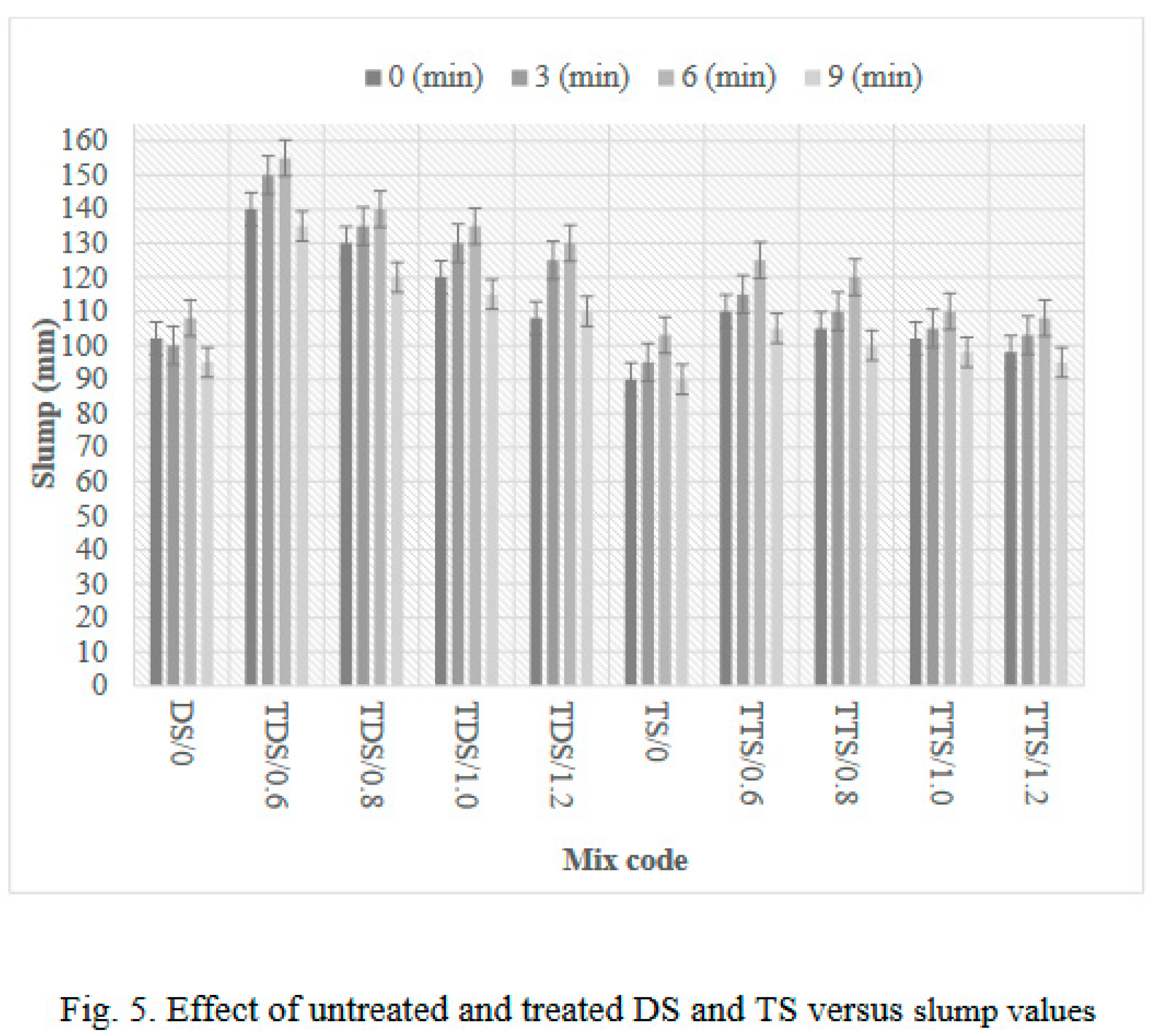

In this research, the properties of fresh concrete can be assessed using slump test method to determine the consistency of concrete. The influence of treated and untreated LWPA on slump test was assessed. From the

Figure 5, the slump value and their age category of fresh concrete specimens were presented. The slump value loss of the mixture for all samples were measured immediately at 3, 6 and 9 min after the consistency of fresh concrete. The highest slump value of 155 mm was obtained for TDS/0.6 mix, the minimum slump value of 90 mm was obtained for TS/0 mix. The good workability is required a longer time for the reaction between cement and superplastisizer for the mixes. It can be noticed that the improvement of workability is due to the lower pre-soaking w/c ratio is denser as compared to untreated shell. On other hand, the cohesion and bond between the pre-soaking shells can enhance the workability of fresh concrete is expected to the reduced friction compared to untreated shell. It has been reported that the use of treated peach shell decreased water absorption in the range of 8% - 15% as compared to non-treated plant-based aggregates [

39].

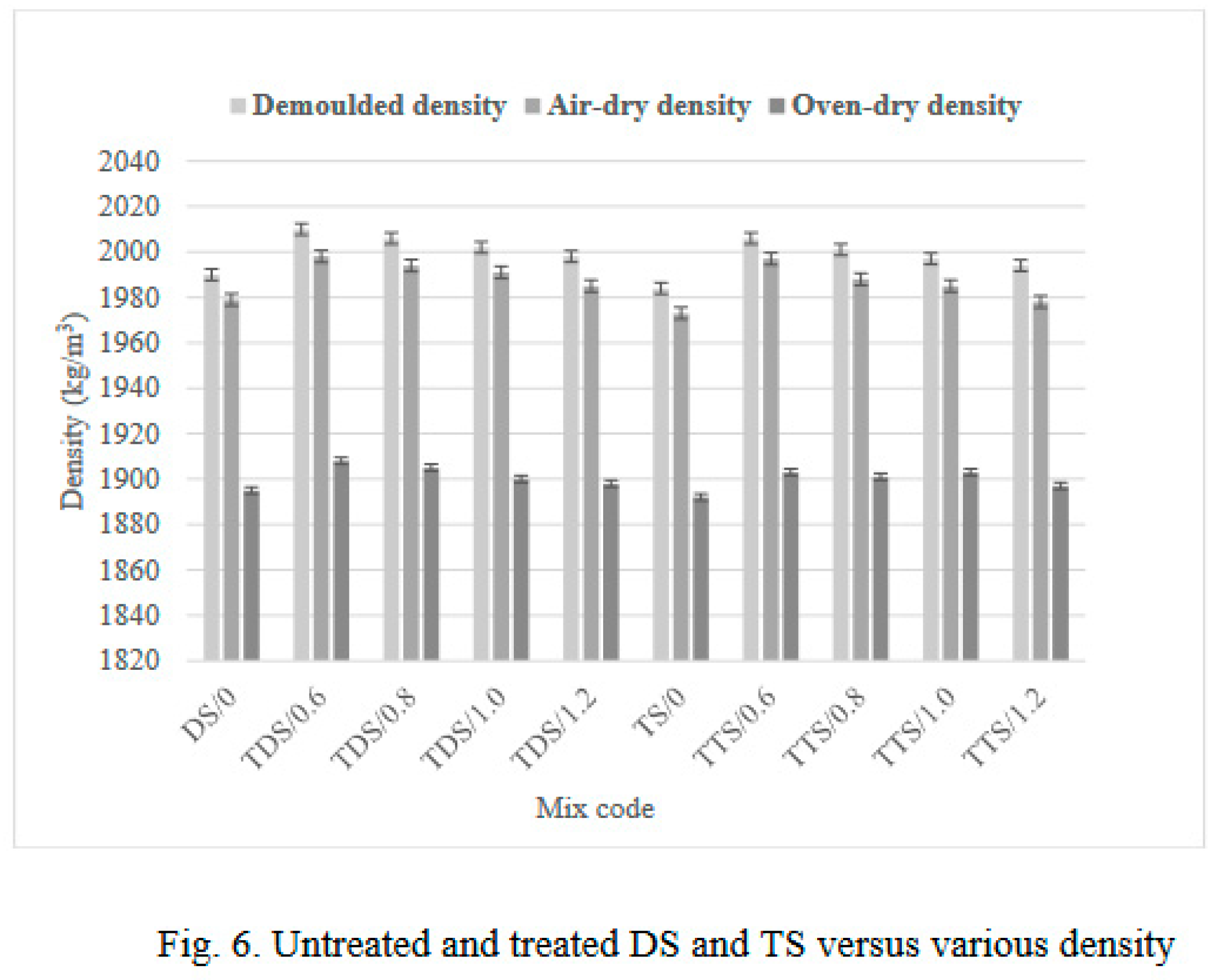

3.2. Densities (demoulded, air-dry and oven-dry)

The lightweight plant-based aggregate (LWPA) concrete can be categorized as a special type of concrete with the characterised of oven-dried density not more than 2000 kg/m

3 [44,50]. Among all the three types of density (DD: demoulded density, ADD: air-dry density, and ODD: oven-dry density), all specimens were fall within the range of the lightweight concrete category, as presented in

Figure 6. The oven-dry density and air-dry density of untreated shell mixes ranging between 1897–1908 kg/m

3 and 1973–1998 kg/m

3, respectively. From the DD results, it can be observed that 5 mixes (TTS/0.8, TTS/0.6, TDS/1.0, TDS/0.8 and TDS/0.6) have slightly exceeded 2000 kg/m

3. All mixes have fulfilled the lightweight concrete requirements in accordance with oven-dry density standard. From the results, the replacement of the DS and TS without treated with various ratios of pre-soaking method on shell aggregates (TDS/0.6-1.2 and TTS/0.6-1.2), marginally increased the DD, ADD, and ODD of about 7%, 10%, and 12%, respectively. The increment in the density of lightweight concrete is due to the higher specify gravity with pre-soaking shell aggregates especially for TDS/0.6 and /TTS/0.6. According to Mannan et al. [

21], It has been reported that the polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) treated also slightly enhanced the overall density of OPS lightweight concrete.

3.3. Mechanical properties of concrete

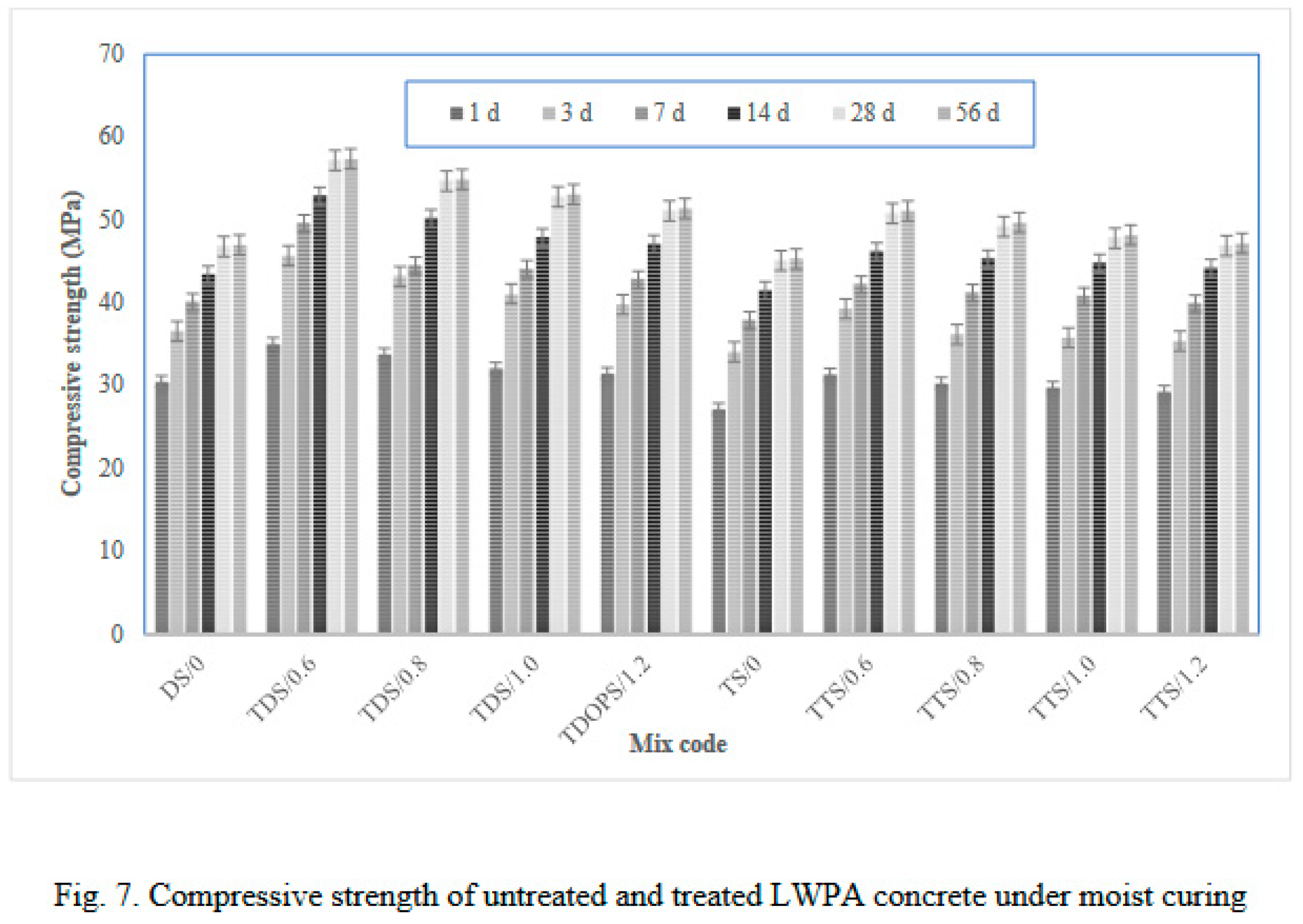

3.3.1. Compressive strength test

The compressive strength results of all the specimens with the pre-soaking modification method on LWPA concretes at the age of 1st, 3rd, 7th, 14th, 28th and 56th days are presented in

Figure 7. The mix with pre-soaking treated shells replacement had increased the strength rather than the control specimens. It can be noticed that the TDS/0.6 concrete mix had achieved the highest compressive strength of about 57 MPa at 28th days. The specimens with pre-soaking treated method obviously improved, from TS/0 to DS/0, TTS/0.6-1.2 and TDS/0.5-1.2 at all ages. All the specimens of TS/0 to TTS/0.6-1.2 compressive strength enhanced by 7.7-15.4% at 1st, 3.8-15.2% at 3rd, 5.3-11.3% at 7th, 6.5-11.3% at 14th, 4.0-17.1% at 28th and 4.2-17.2% at 56th days, respectively. The cube compressive strength increased significantly by 22.2% for TDS/0.6 mix when compared to control mix at 28th days. It can be observed that the thicker and tougher of LWPA shells corresponding to the pre-soaking treated method with various ratios of w/c, which increases significantly for the TDS/0.6. According to Ryu et al. [

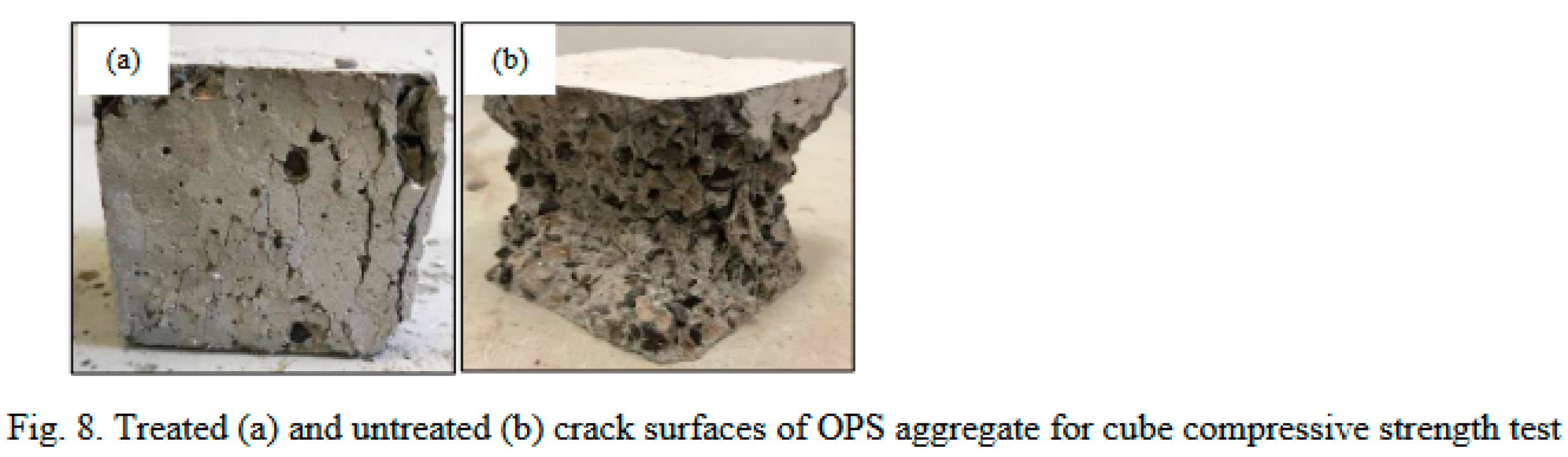

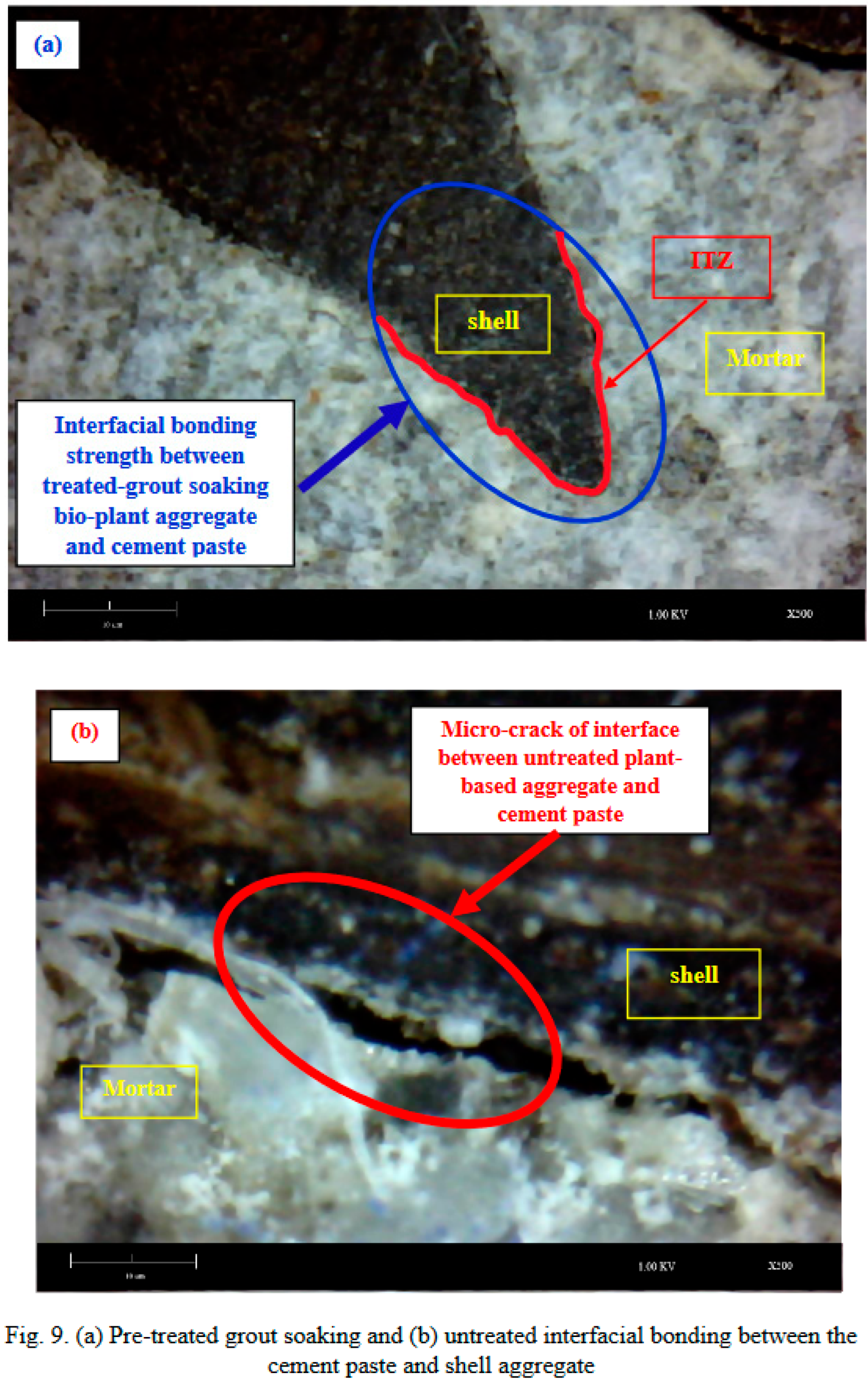

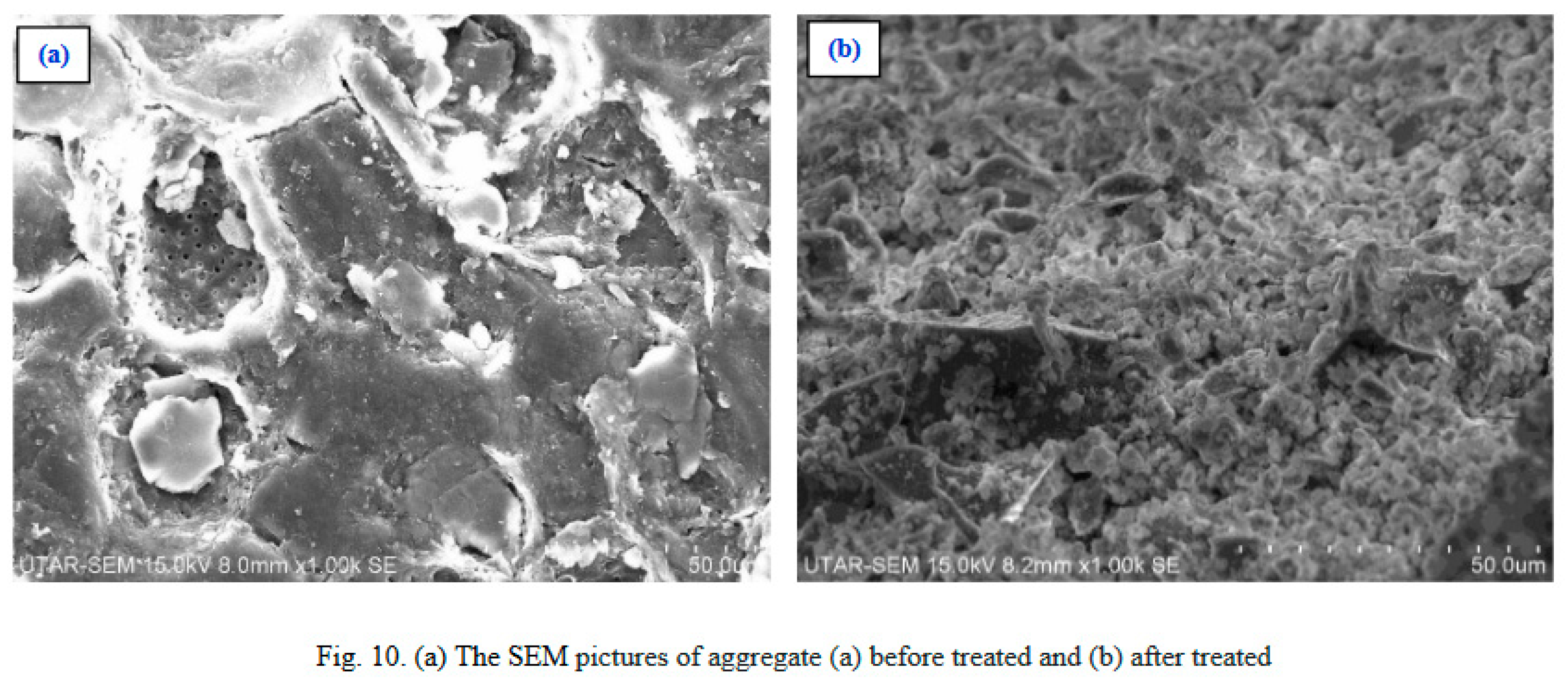

40], the improvement of compressive strength is due to the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) which is subjected to the cohesive bonding strength between the cement paste and LWA. Furthermore, the compressive strength enhancement of the concrete cube is more prominent at the latter stages due to the special impacts of the pre-soaking treated method. It can be seen the crack surfaces of concrete cube with treated and nontreated, as shown in

Figure 8. It was noticed that, pre-soaking treated method on DS and TS aggregate aided in filling the voids and reduced the crack of the lightweight concrete. From

Figure 9, it showed improvement of the pre-soaking treated shells aggregate-cement paste in the interfacial area, and successively reducing the creation of micro-cracks as compared to untreated shells lightweight concrete. In addition, the SEM images of shell aggregate before and after pre-soaking treated, as shown in

Figure 10. It should be noted that, the contributed of the ‘soaking’ effect that helped to improve the ITZ of lightweight concrete during the strengthening process. Martirena et al. [

41] also reported the similar trend with positive effect of surface coating treated on recycled aggregate.

3.4. Split tensile strength test

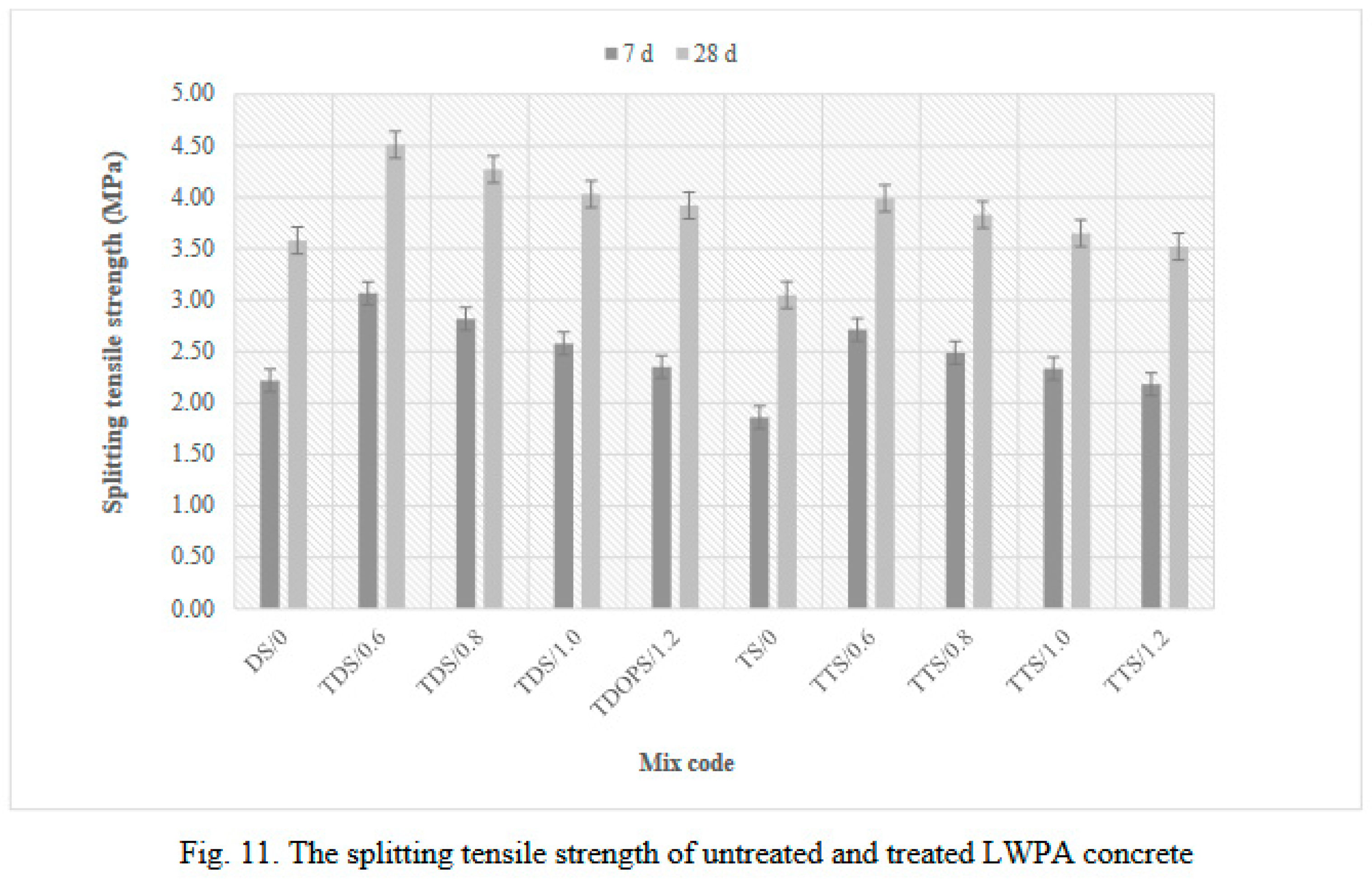

The split tensile strength test results of all the (untreated and treated LWPA) concrete mixers are illustrated in

Figure 11. The incorporation of pre-soaking treated method aggregates accomplished greater tensile strength rather than the control mix. The splitting tensile strength of TDS/0.6-1.2 prepared with treated dura shell at 28th days was extensively strengthened by 9.5 – 26.0% as compared to non-treated LWPA concrete. It was noticed in splitting tensile strength of TTS/0.6-1.2 with pre-treated grout soaking that improved simultaneously when compared to untreated LWPA concrete at 7-days and 28-days. The TDS and TTS modifications with different w/c formulations from 0.6 to 1.2 raise a new developed binding property between the shell aggregate and mortar in LWPA concrete.

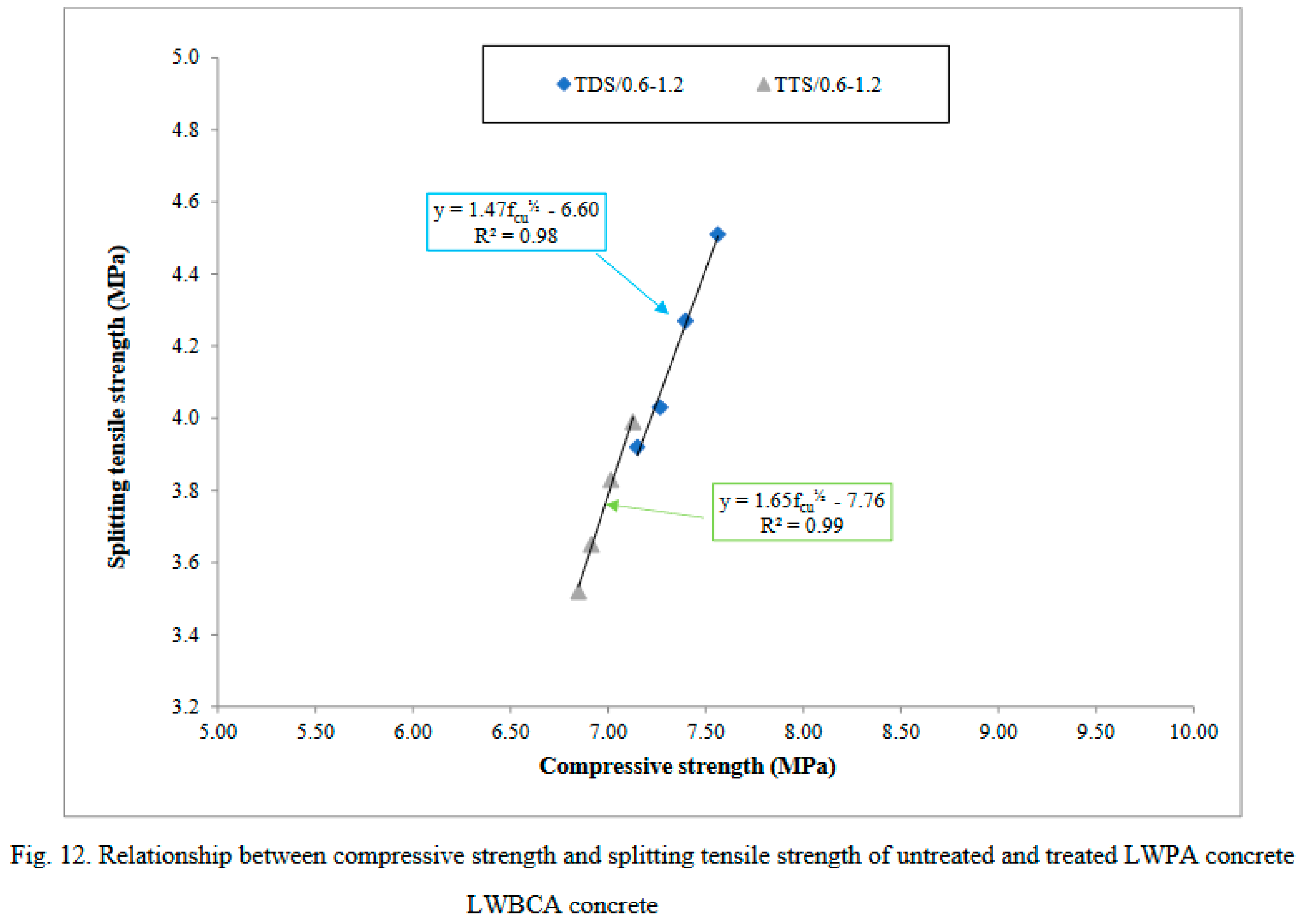

The linear correlations between the compressive strength and the split tensile strength test of pre-treated grout soaking with different w/c (0.6-1.2) formulations of dura and tenera shell at 28th days are presented in

Figure 12. The fitting correlation coefficient (R

2) for both treated dura and tenera reached up to 0.98 and 0.99, respectively. It indicated a consistent relationship between the compressive strength and the split tensile strength. Through the fitted equations, the splitting tensile strength of the treated LWPA concrete can be well predicted by its compressive strength. The following two equations are proposed for different types of treated shells (dura and tenera) to connect the F

t and the cube strength of LWPA concrete.

where

Ft1 and

Ft2 and

fcu are the splitting tensile (MPa) of treated dura and tenera as well as cube strengths in MPa, respectively.

3.5. Strength Relationship

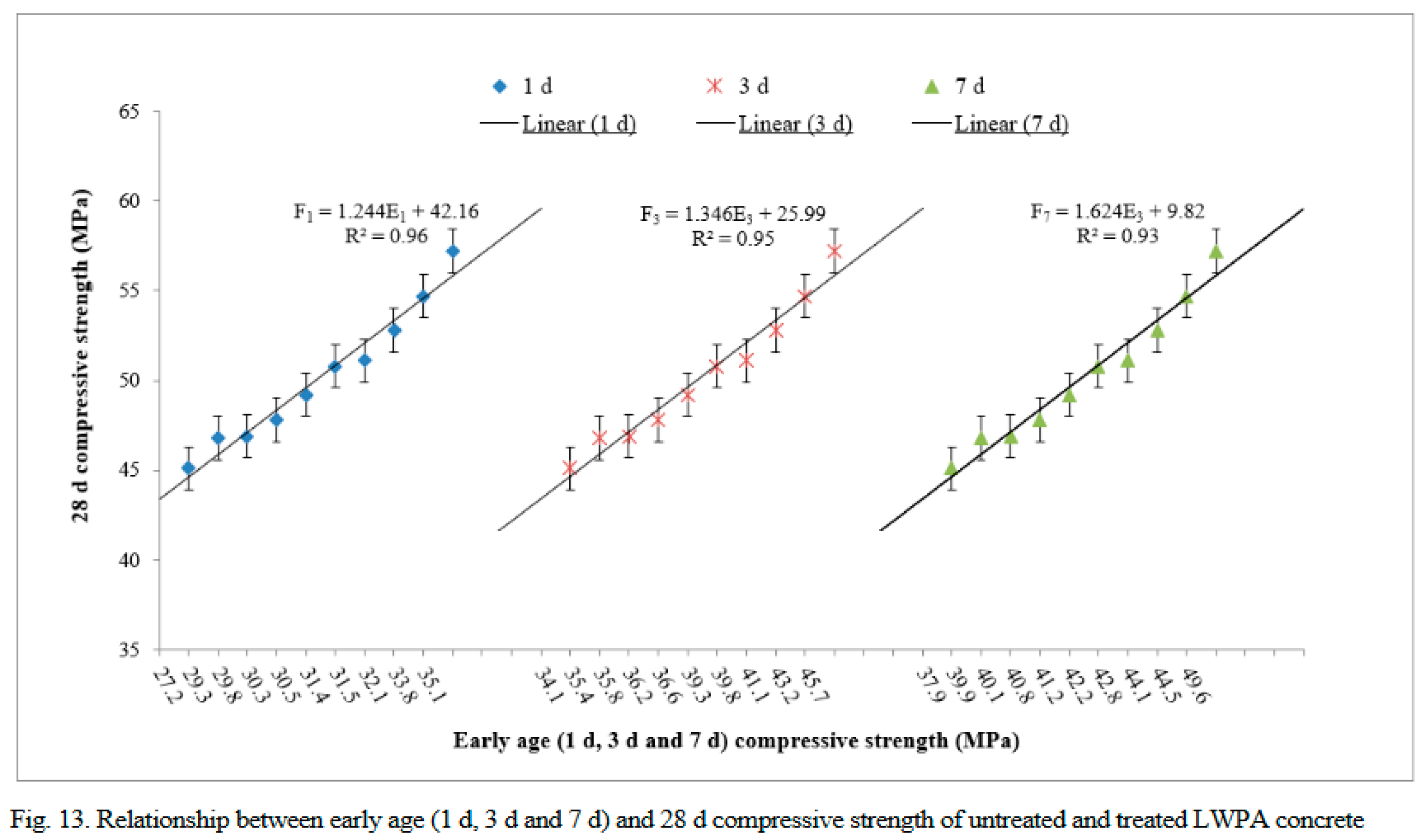

The correlation between the early age at 1 d, 3 d, and 7 d strength as well as the 28-d strength for untreated and treated LWPA, as shown in

Figure 13. It can be noticed that there is an appropriate linear growth between the early stage (1 d, 3 d and 7 d), and those at 28-d compressive strength, for mixtures of untreated and treated LWPA concrete. From the graph, it shows a highly correlated coefficient with a R

2 value within the range of 0.93-0.96. According to Frost, it has been reported the trend line curve with regression degree of above 0.8 is classified as exceptional [

42]. Eq. (3), (4) and (5) are recommended to assess the compressive strength of the cube at the early age (1 d, 3 d and 7 d) strength values.

where,

F1,

F3 and

F7 represent the cube compressive strength (MPa), and

E1,

E3 and

E7 represent the early age at 1 d, 3 d and 7 d of compressive strength, respectively.

According to Yew et al. [

22], the high relationship coefficient was observed in oil palm shell (OPS) concrete made with heat-treated and crushed OPS aggregates. Moreover, Shafigh et al. also reported that OPS concrete made with original oil palm shell aggregates non-treated demonstrated a poorer correlation coefficient [

44].

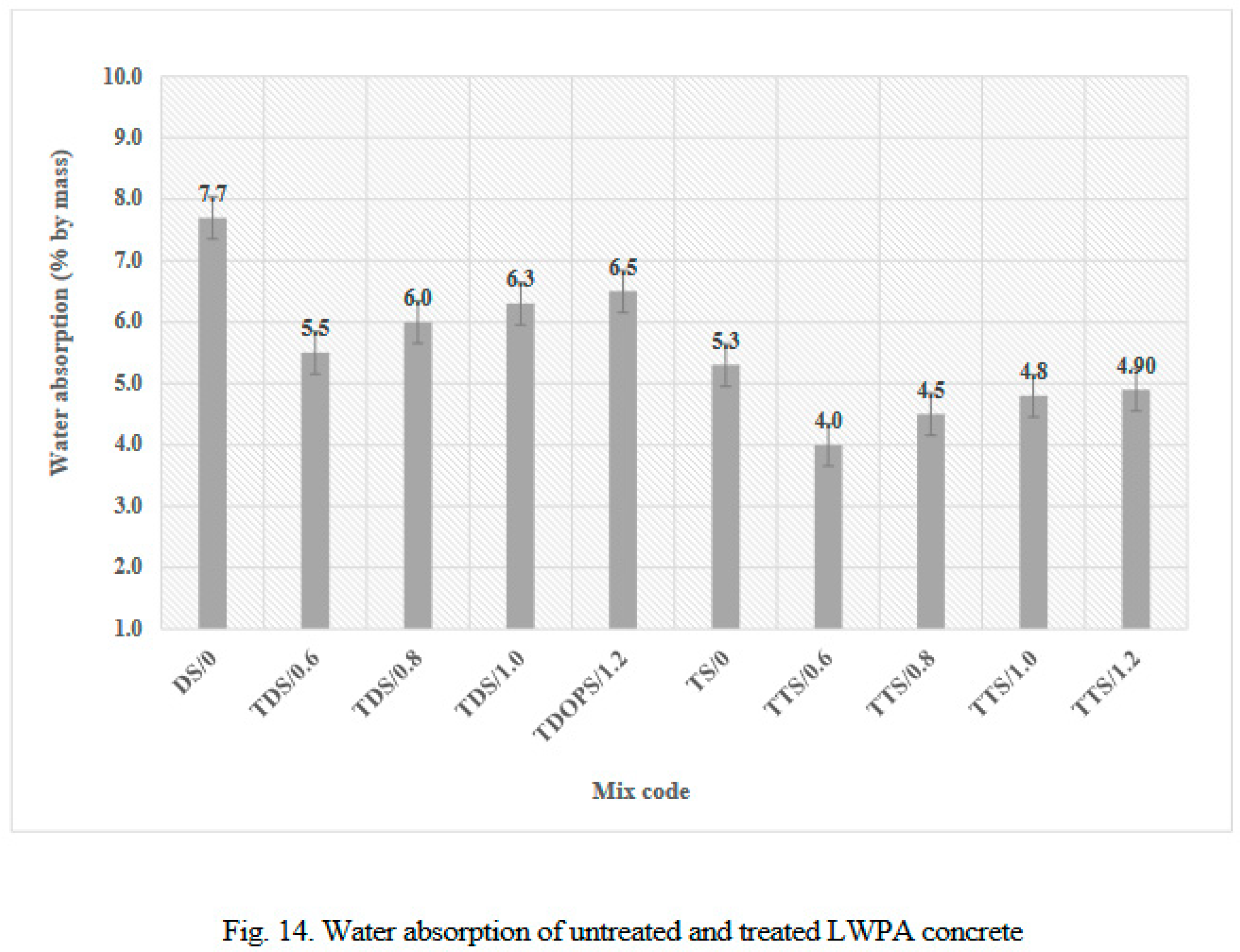

3.6. Water Absorption

Untreated and treated of LWPA with pre-soaking method on concrete mixes with water absorption test, as shown in

Figure 14. It can be noticed that the smallest value of water absorption was about 4.0% for TTS/0.6 specimen. However, the highest water absorption value was achieved at about 7.7% especially for DS/0 specimen. The water absorption for untreated and treated with pre-soaking method on dura shell concrete was higher as compared to tenera shell cube concrete. This phenomenon can be attributed to a thicker dura shell as compared to tenera shell which increased the water absorption. The pre-soaking treated method with lower w/c ratios may reduce the water absorption process. According to Neville [

43], the water absorption falls below 10% can be categorised as good concrete. From the results, the water absorption value attained for untreated and treated LWPA concrete falls in the range of good concrete. Babu [

44] also reported that the addition of expanded polystyrene aggregate had achieved a water absorption measurement fall within the range of 3-6%.

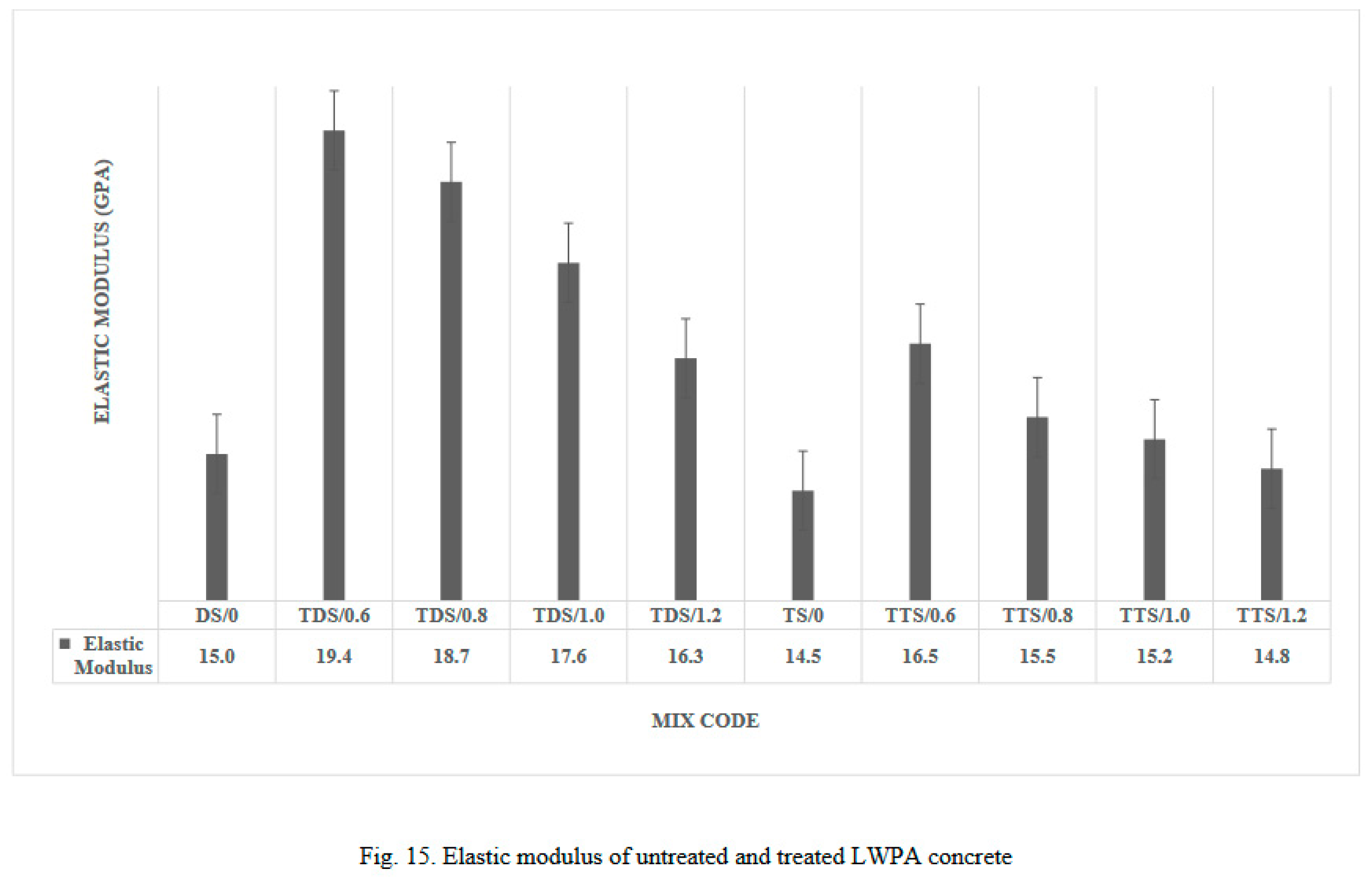

3.7. Elastic Modulus

The impacts of pre-soaking treated with various w/c ratios on the modulus of elasticity for LWPA concrete at 28th days as shown in

Figure 15. The modulus of elasticity for TS/0, DS/0, TTS/0.6-1.2, TDS/0.6-1.2 mixtures were fall in the range of 14.5 GPa - 19.4 GPa, respectively. The modulus of elasticity for non-treated LWPC concrete was lower when compared to pre-soaking treated method of LWPC concrete, which was noticeably strengthened when the pre-soaking modified on LWPC was used. It can be noticed that TDS/0.6 modulus of elasticity increased significantly by approximately 34% compared to DS/0. It can be deduced to the quality of surface pre-soaking treated modification on LWPA, especially for TDS/0.6 with surface strengthening. According to Mazaheripour et al. [

45], the modulus of elasticity values of normal weight concrete (NWC) was fall in the range of 14 GPA - 41 GPa. Moreover, it has been reported the (

E) value for lightweight concrete containing expanded clay aggregate was fall within the range of 10 – 14 GPa [

46].

4. Conclusion

In this research, the following conclusions can be arrived at based on the obtained results.:

The workability of the LWPA concrete enhanced when pre- soaking with various w/c ratios applied. The highest slump value at 155 mm was determined especially for the TDS/0.6. Besides, the incorporating of pre-soaking treated LWPA slightly increased the density of the LWPA concrete.

The impacts of pre-soaking treated on the cube compressive strength were more noticeable at the latter stages. The outcomes of cube compressive strength and split tensile strength of pre-soaking treated LWPA concrete was found increased significantly when compared to untreated dura and tenera shells.

LWPA concrete exposed to pre-soaking treated with various ratios proven a linear relationship with high correlation coefficients. The treated and untreated LWPA cube concrete specimens can be ranked as good concrete based on the water absorption test findings, showing all concrete specimens not more than 10%.

The inclusion of pre-soaking treated in LWPA concrete implied a positive effect on the modulus of elasticity. The highest (E) value was obtained at 19.4 GPa, which increased significantly at about 34% for TDS/0.6 when compared to control concrete.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and / or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by IPSR/RMC/UTARRF/2020-C2/Y02 from the Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia. The authors acknowledge Mr. Yew See Hing for the supply of the plant-based (dura and tenera) coarse aggregate to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest between authors regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Kanojia, A.; Jain, S.K. Performance of coconut shell as coarse aggregate in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 140, 150-156. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, K.P. Reducing the environmental impact of concrete. Concr. Int. 2001, 23, 61–66.

- Doan, D, T.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Naismith, N.; Zhang, T.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Tookey, J. A critical comparison of green building rating systems. Build. Environ. 2017, 123, 243-260. [CrossRef]

- Alwan, Z.; Jones, P.; Holgate, P. Strategic sustainable development in the UK construction industry, through the framework for strategic sustainable development, using Building Information Modelling. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 349-358. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.G.; Zhu, L.; Tan, J.S.H. Green business park project management: Barriers and solutions for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 153, 209-219. [CrossRef]

- Traore, Y.B.; Messan, A.; Hannawi, K.; Gerard, J.; Prince, W.; Tsobnang, F. Effect of oil palm shell treatment on the physical and mechanical properties of lightweight concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 161, 452–460. [CrossRef]

- Yew, M.K.; Yew, M.C.; Beh, J.H.; Saw, L.H.; Lim, S.K. Effects of pre-treated on dura shell and tenera shell for high strength lightweight concrete. J. Buil. Eng, 2021, 42, 102493. [CrossRef]

- Yap, S.P.; Alengaram, U.J.; Mo, K.H.; Jumaat M.Z. Ductility behaviours of oil palm shell steel fibre-reinforced concrete beams under flexural loading. Europ. J. Env. Civ. Eng. 2019, 237, 13. [CrossRef]

- Tayeh, B.A.; Hasaniyah, M.W.; Zeyad, A.M.; Yusuf, M.O. Properties of concrete containing recycled seashells as cement partial replacement: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 13. [CrossRef]

- Abang, A.; Abang, A.; Abdus Salam, S.; Abang, A. R. Basic strength properties of lightweight concrete using agricultural wastes as aggregates. In: International Conference on Low Cost Housing for Developing Countries, Roorkee, India. 1984, 143-146.

- Uysal, T.; Duman, G.; Onal, Y.; Yasa, I.; Yanik J. Production of activated carbon and fungicidal oil from peach stone by two-stage process, J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2014, 108, 47–55. [CrossRef]

- Promraksa, A.; Rakmak, N. Biochar production from palm oil mill residues and application of the biochar to adsorb carbon dioxide, Heliyon. 2020, 6, e04019. [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, B.; Topal, H.; Atimtay, A.T. Peach and apricot stone combustion in a bubbling fluidized bed. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 86, 1175–1193. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, P.; Booshehrian, A.; Delkash, M.; Ghavami, S.; Zanjani, M.K. Use of nano- SiO2 to improve microstructure and compressive strength of recycled aggregate concretes, in: Proceeding Nanotechnology in Construction (NICOM3), Springer. 2009, 215–222.

- Mo, K.H.; Alengaram, U.J.; Jumaat, M.Z. Utilization of ground granulated blast furnace slag as partial cement replacement in lightweight oil palm shell concrete. Mater. Struct. 2015, 48, 2545-2556. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Liu, C.; Sun, W.; Ma, Y.; Zhang L. Effect of peach shell as lightweight aggregate on mechanics and creep properties of concrete. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2020, 24, 2534–2552. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, E.A.; Olivares, F.H. Study of Fine Mortar Powder from Different Waste Sources for Recycled Concrete Production. Sustainable Development and Renovation in Architecture, Urbanism and Engineering. 2017, 253– 262.

- Wang, J.Y.; Zhao, G.J.; Takato, N. Change of brightness, chromatism and infra-red spectra of compressed China fir wood during heat treatment. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2001, 23, 59–64.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, H.; Wang, J. Wood carbonization as a protective treatment on resistance to wood destroying fungi, Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2018, 129, 42–49.

- Wu, F.; Liu, C.; Sun, W. Zhang, L.; Ma, Y. Mechanical and creep properties of concrete containing Apricot shell lightweight aggregate, KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 2948–2957. [CrossRef]

- Mannan, M.A.; Alexander, J.; Ganapathy, C.; Teo, D.C.L. Quality improvement of oil palm shell (OPS) as coarse aggregate in lightweight concrete. Build. Env. 2006, 41, 1239–1242. [CrossRef]

- Yew, M.K.; Mahmud, H.B.; Ang, B.C.; Yew, M.C. Effects of heat treatment on oil palm shell coarse aggregates for high strength lightweight concrete. Mater. Des. 2014, 702–707. [CrossRef]

- Yew, M.K.; Beh, J.H.; Yew, M.C.; Lee, F.W.; Saw, L.H.; Lim, S.K. Performance of surface modification on bio-based aggregate for high strength lightweight concrete. Case Stud. Constr. 2022, 16, e00910. [CrossRef]

- “MPOC expects palm oil production to dip to 19.5 million tonnes in 2020,” MPOC expects palm oil production to dip to 19.5 million tonnes in 2020 | The Edge Markets.

- Serina, R. Malaysian Independent Oil Palm Smallholders and their struggle to Survive 2020. ISEAS-Yusuf Ishak Institute. 2020, 144.

- Yew, M.K.; Mahmud, H.B.; Ang, B.C.; Yew, M.C. Effects of oil palm shell coarse aggregate species on high strength lightweight concrete. Sci. World. J. 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Albert, K.; Barbara, K.; Matt, P. Oil Palm Expansion in Peninsular Malaysia is Guided by Non-Transparency. Chain Reaction Research. 2021. Retrieved from https://chainreactionresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Oil-Palm-Expansion-in.

- Kupaei, R.H.; Alengaram, U.J.; Jumaat, M.Z. The effect of different parameters on the development of compressive strength of oil palm shell geopolymer concrete. Sci. World J. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.O.; Yang, X.; Kong, S.Y.; Paul, S.C.; Wong, L.S. Mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight concrete incorporated with activated carbon as coarse aggregate. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 31, 101347. [CrossRef]

- Zeyad, A.M.; Megat Johari M.A.; Bassam A. Tayeh and Abdalla Saba. Ultrafine palm oil fuel ash: from an agro-industry by-product into a highly efficient mineral admixture for high strength green concrete. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2017, 12, 8187-8196.

- Alexandre Bogas, J.; de Brito, J.; Figueiredo, J. M. Mechanical characterization of concrete produced with recycled lightweight expanded clay aggregate concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 89, 187-195. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Ding, J.; Li, S.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Q. Effects of porous shale waste brick lightweight aggregate on mechanical properties and autogenous deformation of early-age concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 120450. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Saidi, T.; Afifuddin, M. Mechanical properties and absorption of lightweight concrete using lightweight aggregate from diatomaceous earth. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 277, 122324. [CrossRef]

- Loh, L.T.; Yew, M.K.; Yew, M.C.; Beh, J.H.; Lee, F.W.; Lim, S.K.; Kwong, K.Z. Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Synthetic Polypropylene Fiber–Reinforced Renewable Oil Palm Shell Lightweight Concrete. Mater. 2021, 14, 2337. [CrossRef]

- Shafigh, P.; Jumaat, M.Z.; Mahmud, H. Oil palm shell as a lightweight aggregate for production high strength lightweight concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 1848–1853. [CrossRef]

- BS EN 12390. Part 3 testing hardened concrete – compressive strength of test specimens. British Standard Institution; 2009.

- BS EN 12390. Part 6 testing hardened concrete – splitting tensile strength of test specimens. British Standard Institution; 2009.

- BS EN 12390. Part 13 testing hardened concrete – modulus of elasticity of test specimens. British Standard Institution; 2013.

- Wu, F.; Yu, Q.; Liu, C. Durability of thermal insulating bio-based lightweight concrete: understanding of heat treatment on bio-aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121800. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.S.; Kim, D.M.; Shin, S.H.; Lim, S.M.; Park, W.J. Evaluation on the Surface Modification of Recycled Fine Aggregates in Aqueous H2SiF6 Solution. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2018, 12, 19. [CrossRef]

- Martirena, F.; Castaño, T.; Alujas, A.; Orozco-Morales, R.; Martinez, L.; Linsel, S. Improving quality of coarse recycled aggregates through cement coating. J. Sustain. Cem.-Based Mater. 2017, 6, 69-84. [CrossRef]

- , J. Introduction to Statistics: An Intuitive Guide. 2019, 104. Available online: https://statisticsbyjim.com/basics/introduction-statistics-intuitive-guide/ (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Neville, A. M. Properties of Concrete, (CTP-VVP), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14th edition. 2008.

- Babu K. G.; Babu, D. S. Behaviour of lightweight expanded polystyrene concrete containing silica fume. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 755–762. [CrossRef]

- Mazaheripour, M.; Ghanbarpour, S.; Mirmoradi, S.H.; Hosseinpour. I. The effect of polypropylene fibres on the properties of fresh and hardened lightweight self- compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 351–358. [CrossRef]

- Swamy, R.N.; Lambert. G.H. Mix design and properties of concrete made from PFA coarse aggregates and sand. Int. J. Cem. Comp. Light. Con. 1983, 5, 263–275. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).