1. Introduction

Global demand for construction aggregates is forecast to grow steadily by approximately 2.3% per year, reaching around 47.5 billion tons by 2023, which implies a demand of approximately 49–50 billion tons by 2025 [

1]. This trend poses a serious concern, as natural aggregates are non-renewable resources. Their large-scale extraction has led to severe environmental impacts, including land degradation, increased carbon emissions, and ecological disruption [

2,

3,

4]. Therefore, sustainable alternatives to natural aggregates in concrete production are urgently needed. One promising eco-friendly substitute is recycled concrete aggregate (RCA), obtained from processed concrete waste.

Utilizing RCA not only reduces the dependence on natural aggregates but also minimizes the amount of construction and demolition waste disposed into the environment, including waste generated from laboratory activities [

5,

6]. However, research focusing specifically on RCA sourced from laboratory waste remains limited, despite its significant potential for reuse. RCA is typically produced by crushing discarded concrete, followed by sorting based on particle size. The fraction larger than 4.75 mm is classified as coarse recycled concrete aggregate (CRCA), which is commonly used to replace natural coarse aggregates in structural and non-structural concrete applications [

7,

8].

Although RCA presents an environmentally friendly solution, the quality of recycled concrete remains a challenge. Concrete incorporating RCA generally exhibits lower performance compared to conventional concrete [

9,

10,

11]. This decline is primarily due to the high porosity of residual mortar attached to the natural aggregate particles, resulting in increased water absorption and reduced specific gravity—factors that negatively affect the mechanical properties of concrete [

9,

12]. Therefore, treatments are necessary to improve the physical characteristics of RCA and enhance its performance [

9,

13]. One effective and cost-efficient method is thermal-mechanical treatment (TMT), which combines heating and mechanical processes [

14,

15,

16,

17].

The TMT process begins with thermal treatment, using conventional ovens or microwave heating at temperatures ranging from 200 °C to 900 °C [

18]. This heating step aims to dry and weaken the attached mortar through thermal stress [

9,

13]. The second step involves mechanical grinding using steel balls to remove the loosened mortar from the aggregate surface [

13,

19,

20]. Previous studies have demonstrated that TMT can significantly improve RCA quality, including reducing water absorption by up to 55% and increasing specific gravity by as much as 18% [

13,

21].

Low-temperature heating in the range of 250 °C to 300 °C has been proven sufficient to remove adhered mortar from the surface of aggregates, provided that the mechanical treatment is applied intensively [

17,

22,

23]. Moreover, using lower heating temperatures is more economical compared to high-temperature heating (500 °C to 900 °C), as it requires significantly less energy [

24,

25,

26,

27]. One variation of treatment considered effective involves a combination of heating at 250 °C followed by 250 revolutions of mechanical grinding using 12 steel balls. This combination has been shown to significantly enhance the physical properties of RCA and yield satisfactory results in impact value and crushing value tests [

28,

29,

30]. However, many of the existing mechanical ball milling methods do not report the ratio between the weight of steel balls and the weight of aggregates used in the grinding process, making these methods difficult to replicate or optimize at different production scales.

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the effect of TMT using a heating temperature of 250 °C and 250 revolutions of grinding on the physical and mechanical properties of RCA derived from laboratory concrete waste. The RCA processed through TMT (referred to as TRCA) was then incorporated into recycled concrete mixtures as a partial replacement for natural coarse aggregates. The resulting concrete was tested for mechanical performance, particularly compressive strength and elastic modulus, in order to assess the feasibility of TRCA as a sustainable alternative material for green concrete applications.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in three main stages. In the first stage, RCA was prepared, with a portion of it subjected to thermal-mechanical treatment (TMT). In the second stage, both the RCA and natural aggregates (NA) were examined for their physical and mechanical properties. The third stage involved the design, casting, and testing of recycled concrete using both untreated RCA and TMT-processed RCA (TRCA).

2.1. Materials

The RCA used in this study was sourced from laboratory concrete waste generated by the Department of Civil Engineering and Planning, Universitas Negeri Malang, and subsequently processed using a stone crusher. The crushed material was then screened to produce coarse recycled concrete aggregate (CRCA, >4.75 mm) and fine recycled concrete aggregate (FRCA, <4.75 mm), in accordance with ASTM C136 [

31]. This study focused on RCA with particle sizes ranging from 4.75 to 38.1 mm (CRCA), which was used as a replacement for natural coarse aggregate (NCA) in concrete mixtures. To enhance its physical and mechanical properties, the RCA underwent thermal-mechanical treatment (TMT) using a drying oven and a Los Angeles abrasion machine containing steel balls. RCA treated through this method is referred to as TRCA and was also evaluated as a substitute for NCA in concrete. All three types of aggregates are shown in

Figure 1. The NCA and natural fine aggregate (NFA) were obtained from a local supplier and conformed to ASTM C33 standards [

32]. The cement used was Portland Composite Cement (PCC) under the Semen Gresik brand, which complies with the Indonesian standard SNI 7064:2022 [

33].

2.2. Thermal-Mechanical Treatment (TMT)

2.2.1. Thermal Treatment

In this stage, the RCA was heated using a laboratory drying oven (model UN50) at a temperature of 250 °C. The heating process was carried out to dry the adhered mortar residue, thereby weakening its bond with the aggregate particles and making it easier to detach from the surface of the natural coarse aggregate (NCA) [

9,

13]. The thermal treatment duration was set at 2 hours. After the heating and cooling phases, the RCA was subjected to mechanical processing.

2.2.2. Mechanical Treatment

The second treatment stage involved mechanical processing using a ball milling method. This process utilized a Los Angeles abrasion machine in accordance with ASTM C131 standards [

34]. The primary objective was to detach residual mortar from the surface of the natural fine aggregate (NFA) [

35]. To maximize the removal of adhered mortar without causing excessive degradation of particle size, a steel ball-to-RCA weight ratio of 1:4 was used, equivalent to approximately 12 steel balls for every 20 kg of RCA. The machine was operated for a total of 250 revolutions. Following the mechanical treatment, the aggregates were washed with running water to remove excess dust. A subsequent screening process was performed to separate particles smaller than 4.75 mm from the treated recycled coarse aggregate (TRCA).

2.3. Concrete Sample Preparations

The concrete mix design was developed based on the Indonesian Standard (SNI) with a target compressive strength of 20 MPa. The mix proportions for both normal concrete and recycled concrete incorporating RCA and TRCA at various substitution levels of natural fine aggregate (NFA) are presented in

Table 1. The cement content was kept constant across all experimental mixtures, while the water-to-cement (W/C) ratio was adjusted to achieve a slump value of 12 ± 2 cm. This adjustment was necessary due to the higher porosity and water absorption of RCA, which requires a greater amount of mixing water. Concrete specimens were cast in cylindrical molds with a diameter of 15 cm and a height of 30 cm, in accordance with SNI 03-2834 [

36].

2.4. Test Methods

2.4.1. Aggregates Tests

Three types of coarse aggregates were examined in this study: natural coarse aggregate (NCA), recycled concrete aggregate (RCA), and treated recycled concrete aggregate (TRCA). Both RCA and TRCA were used as substitutes for NCA in the concrete specimens; therefore, it was necessary to evaluate and compare their physical and mechanical properties. Aggregate testing also served to assess the effectiveness of the thermal-mechanical treatment (TMT) in enhancing the quality of RCA.

The physical property tests conducted on coarse aggregates included sieve analysis, bulk density, specific gravity, and water absorption. Sieve analysis was carried out to determine the percentage of aggregate particles passing through a series of sieves, which was then plotted in a particle size distribution curve to calculate the fineness modulus (FM), following ASTM C136 [

31]. Bulk density, which represents the mass per unit volume of aggregate—including the individual particle volume and the voids between particles—was determined in accordance with ASTM C29 [

37]. Specific gravity and water absorption tests were conducted according to ASTM C127 [

38].

In addition to physical properties, the mechanical strength of the coarse aggregates was evaluated through the aggregate crushing value and abrasion tests. The crushing value test was conducted based on BS 812-110 [

39] by applying a uniform load up to 400 kN over a 10-minute period. For the abrasion test, a Los Angeles abrasion machine with grading B was used, incorporating 11 steel balls and 500 revolutions, in accordance with ASTM C131 [

34].

2.4.1. Concrete Tests

The mechanical strength of concrete was evaluated through two types of tests: compressive strength and elastic modulus, conducted at 28 days of curing using cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 15 cm and a height of 30 cm. The modulus of elasticity test was performed in accordance with ASTM C469 [

40] to determine the stress–strain ratio of concrete within the elastic range. The specimens were tested using a universal testing machine (UTM) equipped with a compressometer and load cell. These accessories were connected to a data logger to capture real-time data of the applied load and the resulting deformation. The test setup for determining the modulus of elasticity is illustrated in

Figure 2. The compressive strength was obtained by loading the specimen until failure, and the maximum load was recorded to calculate the compressive strength. The elastic modulus of concrete was determined based on 40% of the maximum stress and the corresponding strain.

In this study, the bulk density of concrete was measured prior to mechanical testing. The dimensions and mass of each specimen were recorded to determine the bulk density. This parameter is critical, as the density of concrete directly influences its mechanical performance. Moreover, the type and substitution percentage of coarse aggregates in the mix can significantly affect the bulk density, as each type of coarse aggregate has different specific gravity and bulk density values.

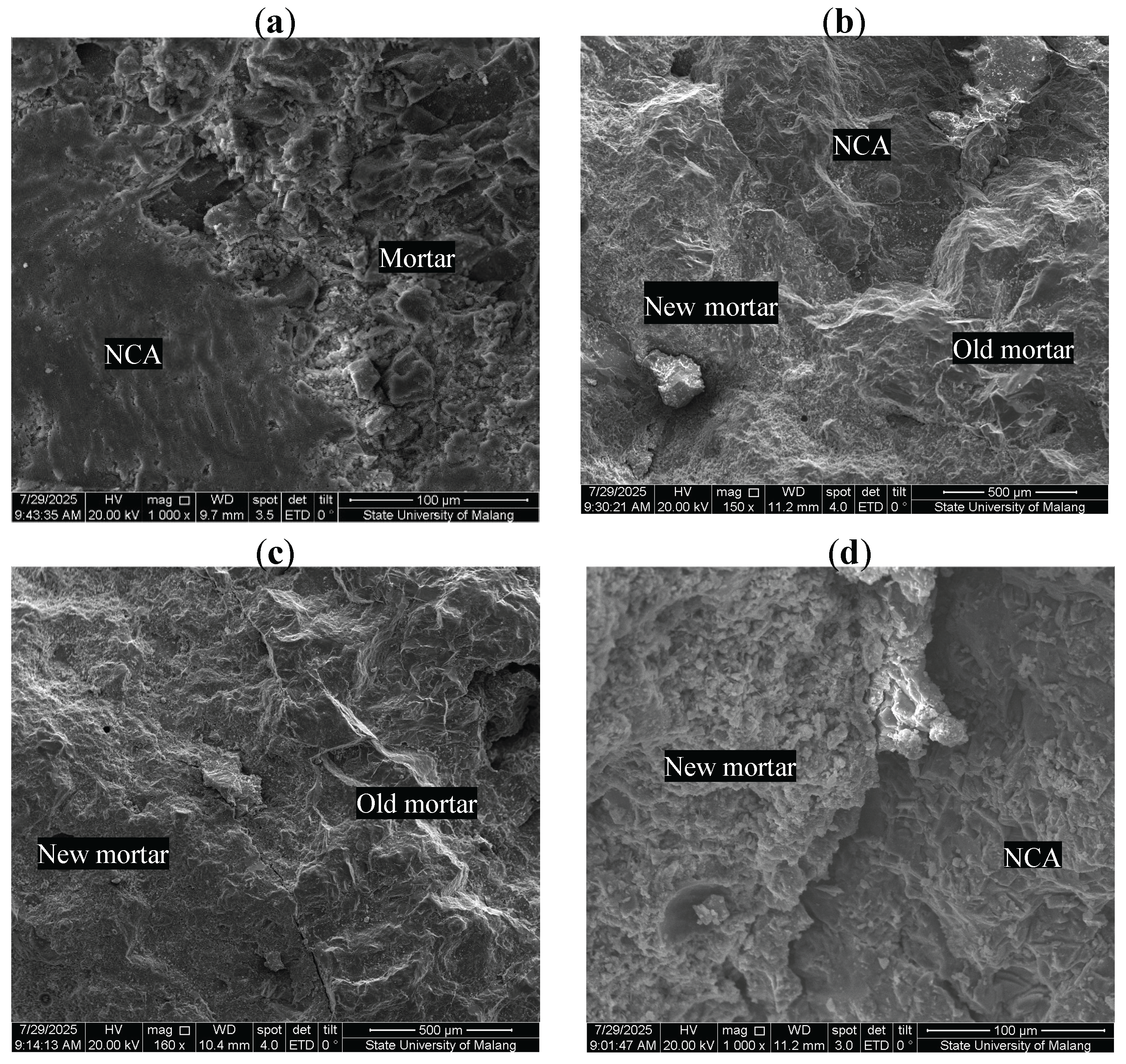

The microstructure of the concrete was also analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). SEM images provided detailed information on the pore distribution within the concrete matrix. Additionally, the interfacial transition zones (ITZ) between the new mortar and the coarse aggregates, as well as between the new and old mortar, were observed and analyzed.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. RCA Properties

The mechanical properties of concrete incorporating RCA are influenced by various factors, including cement type, water-to-cement (w/c) ratio, production process, and the characteristics of the constituent aggregates [

41]. Among these, the most significant distinction between recycled and conventional concrete lies in the type of coarse aggregate used. Recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) exhibits different properties compared to natural coarse aggregate (NCA). Likewise, treated recycled concrete aggregate (TRCA) possesses distinct characteristics from RCA due to the treatment method applied—in this study, thermal-mechanical treatment (TMT). The comparative properties of these three types of coarse aggregates are presented in

Table 2.

3.1.1. Sieve Analysis

The test results showed that the fineness modulus (FM) values were 8.89 for NCA, 9.77 for RCA, and 9.25 for TRCA. These values indicate that RCA had the coarsest gradation among the aggregates, followed by TRCA, while NCA exhibited the finest gradation. The high FM value of RCA suggests that the recycled aggregate still contains a significant proportion of large particles, resulting from the crushing of old concrete that did not fully produce uniformly graded particles [

8]. This condition may reduce the workability of concrete mixtures due to suboptimal particle size distribution. In contrast, TRCA exhibited a lower FM value compared to RCA, indicating that the TMT process was effective in improving the particle size distribution of the aggregate. Consistent with previous studies [

42,

43], the TMT facilitated the detachment of residual mortar adhered to the aggregate surface, leading to a more uniform particle size and improved gradation.

The three types of coarse aggregates used in this study—NCA, RCA, and TRCA—were classified under the same size category, specifically size number 56 according to ASTM C33. This classification confirms that, in general, the particle size dimensions of all three aggregates are suitable for use as coarse aggregates in structural concrete mixtures. Being within the same size category allows for a fair comparison of their physical properties and performance in concrete mixes. The sieve analysis results for the aggregates are illustrated in

Figure 3.

3.1.2. Bulk Density

The test results showed that the compacted bulk density values were 1.46 g/cm

3 for NCA, 1.32 g/cm

3 for RCA, and 1.42 g/cm

3 for TRCA. Meanwhile, the loose bulk densities were 1.36 g/cm

3 for NCA, 1.26 g/cm

3 for RCA, and 1.36 g/cm

3 for TRCA. The lower bulk density of RCA compared to NCA indicates that RCA has a lower packing density, which is generally attributed to the presence of residual mortar adhering to the aggregate surface [

44]. This residual mortar is lighter and more porous than natural aggregate, contributing to the reduced bulk density of RCA. Additionally, the angular and irregular shape of RCA particles, which are less rounded than natural aggregates, increases the inter-particle voids, further decreasing the overall bulk density [

45].

The application of the TMT method to RCA proved effective in increasing the bulk density of the recycled aggregate, in line with previous research findings [

44,

45]. This is evidenced by the TRCA, which exhibited a compacted bulk density approaching that of NCA, with a 7.5% increase compared to untreated RCA. This improvement is attributed to the successful reduction of adhered mortar on the aggregate surface during the TMT process, as well as enhancements in particle shape and texture, resulting in characteristics more similar to those of natural aggregates. With cleaner surfaces and more regular particle shapes, the inter-particle voids were reduced, leading to a denser aggregate structure.

The increase in bulk density observed in TRCA has positive implications for recycled concrete mixtures. Aggregates with higher bulk density contribute to producing concrete with improved overall density, which in turn enhances compressive strength and durability. Furthermore, better weight and volume distribution of the aggregates aids in controlling the workability of the concrete and minimizes the need for mix adjustments due to material variability. Therefore, the improved bulk density of TRCA serves as a key indicator that the TMT method effectively enhanced the physical characteristics of the recycled aggregate, making it more suitable for use as a replacement for natural coarse aggregate in structural concrete applications.

3.1.3. Specific Gravity

The test results showed that NCA had a dry specific gravity (Sd) of 2.50, a saturated surface-dry specific gravity (Ss) of 2.57, and an apparent specific gravity (Sa) of 2.68. For RCA, the values were Sd = 2.33, Ss = 2.45, and Sa = 2.65. In contrast, TRCA exhibited improved values compared to RCA, with Sd = 2.42, Ss = 2.53, and Sa = 2.72. The lower specific gravity values of RCA compared to NCA confirm that recycled aggregates possess lower material density, primarily due to the presence of residual old mortar adhering to the aggregate surface [

13]. This old mortar is characterized by high porosity and low density, which contributes to the overall reduction in aggregate specific gravity. Additionally, the porous surface of RCA allows greater water absorption into the aggregate, thereby affecting both the saturated surface-dry (SSD) and apparent specific gravity values [

46]. The low specific gravity of RCA is considered one of its main drawbacks, as it can negatively impact the final strength of concrete and the consistency of mix proportion calculations [

44].

The TMT method applied to RCA proved effective in increasing specific gravity, in line with previous studies [

9,

13,

17]. The heating process helped to dry and weaken the bond of adhered mortar, while the mechanical grinding effectively removed the residual mortar from the aggregate surface. As a result, TRCA exhibited a cleaner, denser surface and contained fewer voids or internal pores, leading to a 3.2% increase in specific gravity compared to RCA. Consequently, the specific gravity of TRCA improved, and in some cases even surpassed that of NCA in terms of apparent specific gravity (Sa), indicating that the treated aggregate possesses a denser structure with lower internal porosity.

3.1.4. Water Absorption

Water absorption is a key parameter that reflects the porosity level of coarse aggregates and significantly influences both the fresh and mechanical properties of the resulting concrete [

47]. Test results showed that the water absorption values were 2.50% for NCA, 5.24% for RCA, and 4.79% for TRCA. These results indicate that RCA has a substantially higher water absorption capacity compared to natural aggregates, while TRCA demonstrated a reduction in water absorption after undergoing the TMT process, although it still did not reach the level of NCA.

The high water absorption observed in RCA is primarily due to the presence of old mortar residue still adhering to the surface of the recycled aggregate. This residual mortar is highly porous and contains numerous micro-voids, allowing it to absorb a greater amount of water [

46]. Additionally, the crushing process involved in recycling old concrete tends to produce aggregates with irregular surfaces, sharp edges, and microcracks, all of which further increase the aggregate’s water absorption capacity. This high absorption rate is one of the main drawbacks of RCA, as it can affect the water demand of concrete mixtures and reduce workability if not properly compensated by adjusting the water-to-cement (W/C) ratio.

The application of the TMT method has proven effective in improving the water absorption characteristics of recycled aggregates. Through heating at 250 °C, the adhered mortar undergoes dehydration and loses its bonding strength, making it easier to detach during the subsequent mechanical grinding process. The combination of these two processes effectively reduces the amount of residual mortar and partially seals open pores on the aggregate surface. This is reflected in the reduced water absorption value of TRCA to 4.79%, which, although still higher than that of NCA, shows a positive trend toward the characteristics of natural aggregates.

The lower water absorption of TRCA compared to RCA offers significant advantages in concrete mix design. Aggregates with reduced water absorption facilitate better control over aggregate moisture content, leading to more consistent effective water content in the concrete mix and consequently more stable compressive strength results. Additionally, the use of TRCA helps minimize the risk of segregation and bleeding caused by excess water in the mixture. Therefore, the reduction in water absorption observed in TRCA serves as a key indicator of the success of the TMT method in improving the physical properties of RCA and enhancing the suitability of recycled aggregates for use as a replacement for natural coarse aggregates in sustainable concrete applications.

3.1.5. Mechanical Properties

The test results revealed that the abrasion index values were 15 for NCA, 30 for RCA, and 26 for TRCA. These values indicate that RCA has the lowest abrasion resistance, meaning its particles are more prone to degradation under friction or impact. This weakness is attributed to the presence of adhered old mortar and numerous internal cracks, which compromise the structural integrity of the aggregate [

48]. In contrast, TRCA exhibited a 13.3% improvement in abrasion resistance compared to RCA, although it still did not fully match the performance of NCA. This enhancement resulted from the TMT process, which effectively reduced residual mortar content and improved particle shape and density, thereby increasing resistance to mechanical wear in concrete environments.

In the crushing value test, aggregates were subjected to a compressive load of 400 kN for 10 minutes. The results showed that NCA had a crushing value of 17, RCA of 27, and TRCA of 24. These values suggest that RCA exhibits the lowest resistance to compressive loads due to its fragile internal structure, high porosity, and susceptibility to cracking [

49]. TRCA showed improvement, with an 11% reduction in crushing value compared to RCA, indicating that the TMT process effectively enhanced the mechanical strength of the recycled aggregate by removing weak mortar and densifying the aggregate surface.

In general, the higher abrasion and crushing values observed in RCA compared to NCA reflect the quality degradation caused by the crushing of old concrete and the high content of residual mortar. However, the significant reduction in these values following the TMT process demonstrates the effectiveness of this method in enhancing the mechanical performance of recycled aggregates. Accordingly, the improved mechanical properties of TRCA make it more suitable for partial or even full replacement of NCA in recycled concrete. The application of TMT presents a promising approach to optimizing the use of recycled aggregates, thereby promoting sustainability in the construction industry without compromising the structural performance of concrete.

3.2. Concrete Properties

3.2.1. Bulk Density of Concrete

The reference concrete sample (REF), which contained neither RCA nor TRCA, exhibited the highest bulk density, reaching approximately 2.39 g/cm

3. This reflects the optimal density achieved in concrete composed entirely of natural aggregates. When NCA was progressively replaced with RCA, a gradual decrease in concrete bulk density was observed with increasing substitution levels, as shown in

Figure 4. The bulk density of RCA25 concrete was 2.35 g/cm

3 and continued to decline, reaching the lowest value of 2.29 g/cm

3 at RCA100, this trend is consistent with findings reported in various previous studies [

50,

51].

In contrast, concrete incorporating TRCA exhibited a higher bulk density than those made with RCA. TRCA25 and TRCA50 achieved bulk densities of approximately 2.36 g/cm3 and 2.37 g/cm3, respectively, with TRCA50 closely approaching the value of the reference concrete. This indicates that at a 50% replacement level, TRCA can substitute NCA without significantly compromising the bulk density of the concrete. However, for TRCA75 and TRCA100, the bulk densities decreased again to 2.35 g/cm3 and 2.32 g/cm3, respectively, although these values remained higher than those of RCA concrete at the same substitution levels.

The increase in bulk density observed in TRCA compared to RCA confirms the effectiveness of the TMT method in improving the structure of recycled aggregates. The partial removal of old mortar, combined with enhanced particle compaction through heating and mechanical grinding, resulted in denser aggregates with improved particle size distribution. Consequently, these aggregates contributed to higher-density concrete. Overall, the use of TRCA in concrete mixtures provided better bulk density performance than RCA, particularly at low to moderate replacement levels (25–50%).

3.2.2. Compressive Strength

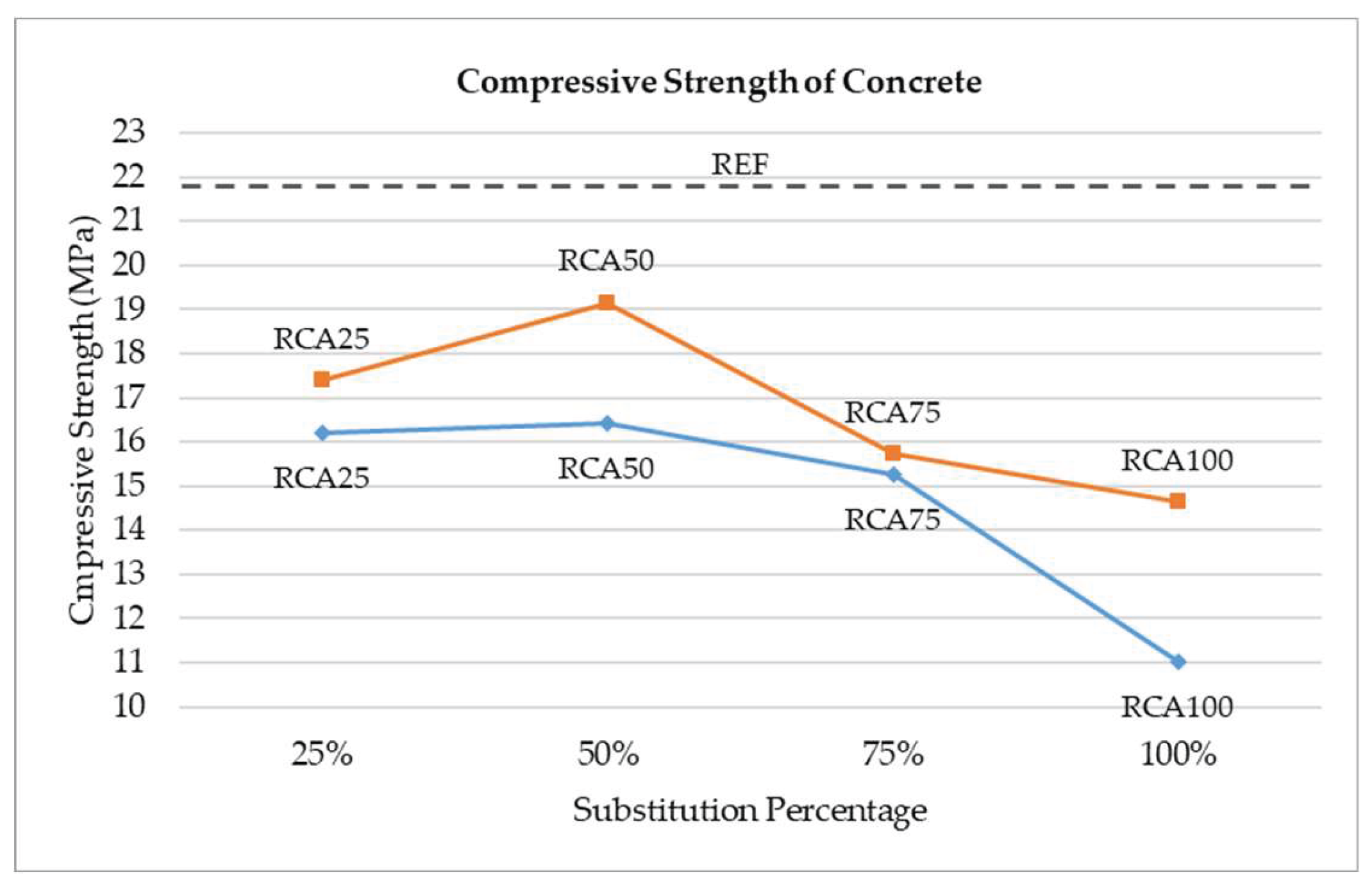

Compressive strength testing was conducted to evaluate the mechanical performance of recycled concrete incorporating RCA and TRCA as replacements for natural coarse aggregate (NCA). The test results are presented in

Figure 5. The reference concrete (REF), which contained no recycled aggregate, achieved the highest compressive strength at 21.9 MPa, reflecting the optimal performance of conventional concrete made with natural aggregates.

In contrast, concrete containing RCA exhibited a decreasing trend in compressive strength with increasing substitution levels [

41,

48]. The compressive strength values were 16.2 MPa for RCA25, 16.4 MPa for RCA50, 15.3 MPa for RCA75, and only 11.0 MPa for RCA100. This decline is attributed to the high porosity and residual old mortar content of RCA, which contribute to the formation of weak interfacial transition zones (ITZ) and a fragile internal aggregate structure prone to cracking [

52]. These characteristics highlight the significant limitations of RCA as a coarse aggregate, particularly at high replacement levels.

In contrast, the use of TRCA demonstrated better performance than RCA, particularly at low to moderate replacement levels. The compressive strengths recorded were 17.4 MPa for TRCA25, 19.2 MPa for TRCA50, 15.7 MPa for TRCA75, and 14.6 MPa for TRCA100. The highest compressive strength among the TRCA group was observed in TRCA50, which closely approached the performance of the reference concrete, with a difference of only about 2.7 MPa. This indicates that at a 50% replacement level, TRCA is capable of maintaining concrete strength nearly equivalent to conventional concrete.

Nevertheless, despite the improved performance of TRCA, compressive strength still declined at higher replacement levels (75% and 100%). This suggests that the quality of TRCA does not yet fully match that of natural aggregates under full substitution conditions. Therefore, TRCA is most effective when used at replacement levels between 25% and 50%, where the compressive strength remains within acceptable limits for mid-grade structural applications.

3.2.3. Modulus of Elasticity

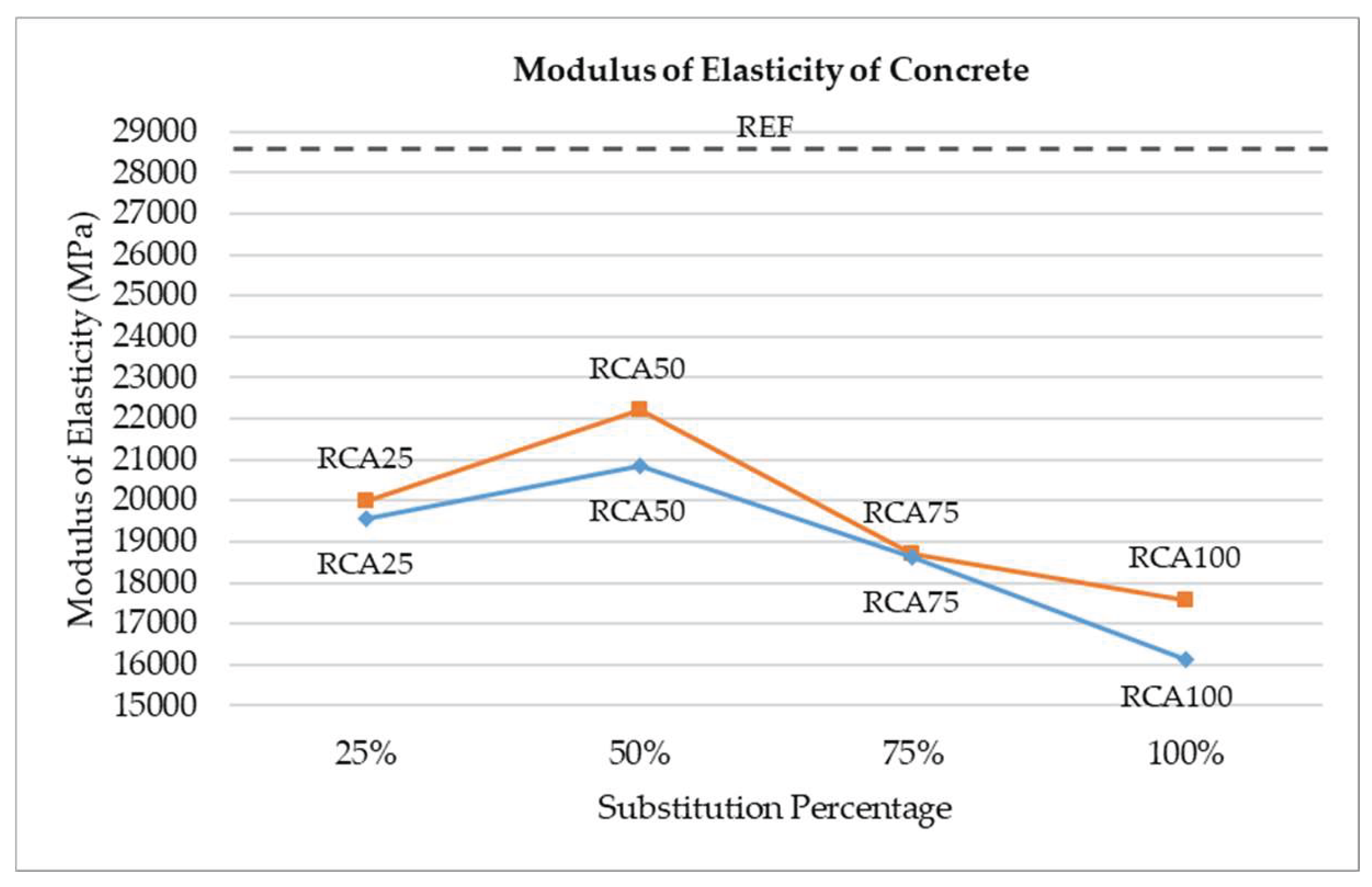

According to the data presented in

Figure 6, the reference concrete (REF) with natural coarse aggregate exhibited the highest elastic modulus, reaching 28,646 MPa, reflecting a dense and robust concrete structure. When NCA was replaced with RCA, the elastic modulus consistently declined with increasing substitution levels. RCA25 showed a modulus of 19,583 MPa, RCA50 of 20,859 MPa, RCA75 of 18,641 MPa, and RCA100 dropped to only 16,123 MPa. This reduction is attributed to the higher porosity and presence of weak residual mortar in RCA, which result in a fragile interfacial transition zone (ITZ) that lacks proper integration with the cement paste [

52].

In contrast, concrete incorporating TRCA showed better results than that made with RCA. The elastic modulus was 20,002 MPa for TRCA25, increased to 22,199 MPa for TRCA50, and then declined to 18,688 MPa and 17,587 MPa for TRCA75 and TRCA100, respectively. This pattern mirrors the trend observed in compressive strength, where a 50% TRCA replacement yielded optimal performance, closely approaching that of the reference concrete. These findings demonstrate that the TMT method effectively enhanced the structure of recycled aggregates, resulting in improved stiffness in the resulting concrete.

TRCA50 recorded an elastic modulus approximately 22% lower than that of the reference concrete, whereas RCA50 was about 27% lower. This indicates that TRCA is more effective in maintaining the structural integrity of concrete compared to untreated RCA. The effectiveness of TMT in improving the aggregate surface and reducing internal porosity contributes to the formation of a denser and stronger interfacial transition zone (ITZ), resulting in improved elastic response under load for TRCA concrete.

Overall, these findings suggest that TRCA is most effective when used at a substitution level of 25–50%, where the concrete’s elastic modulus remains within an acceptable range for medium-grade structural applications. The use of untreated RCA at high replacement levels (≥75%) is strongly discouraged without additional treatment, as the significant reduction in modulus can lead to excessive deformation and reduced long-term durability of the concrete.

3.2.4. ITZ Between Mortar and Aggregate

Figure 7a shows the ITZ in the reference concrete incorporating NCA. The interface between the NCA and mortar appears to be very tight, with minimal visible pores. The NCA surface is relatively smooth and clean, and the contact between the aggregate and cement paste demonstrates a well-integrated microstructure. This condition results in a dense and strong ITZ, contributing to the high compressive strength and elastic modulus observed in the reference concrete.

In contrast,

Figure 7b clearly reveals the presence of a residual old mortar layer adhered to the RCA. This old mortar introduces two distinct ITZ layers: one between the original NCA and the old mortar, and another between the old mortar and the new mortar. As illustrated in

Figure 7c, the microstructure surrounding the ITZ appears non-homogeneous, with numerous pores and microcracks. These features indicate poor microstructural integrity at the ITZ, which negatively impacts the mechanical strength of RCA concrete. Furthermore, the presence of old mortar hinders optimal bonding with the new mortar, creating weak points that accelerate deterioration when the concrete is subjected to loading.

The surface of TRCA appears noticeably cleaner than that of RCA, with significantly less residual old mortar, as shown in

Figure 7d. The TMT method proved effective in removing the majority of the adhered mortar from the RCA surface. The resulting ITZ is denser and more compact, with a more homogeneous particle distribution and smaller pore sizes. The contact between TRCA and the new mortar also appears to be more structurally integrated at the micro level, enhancing the bonding between components within the concrete matrix.

Across the four SEM images in

Figure 7, it is evident that ITZ quality is highly dependent on the cleanliness and density of the aggregate surface [

52,

53]. The reference concrete containing NCA exhibited the best ITZ quality, followed by TRCA, while the ITZ in RCA concrete was the weakest. These differences in ITZ quality align with the compressive strength and elastic modulus results discussed previously, where TRCA consistently outperformed RCA. This confirms that ITZ enhancement through the TMT method is a key factor in improving the overall performance of recycled aggregate concrete.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluated the influence of thermal-mechanical treatment (TMT) on the physical properties of recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) and the performance of recycled concrete incorporating RCA as a substitute for natural coarse aggregate. The TMT method involved a heating process at 250 °C followed by mechanical grinding using a Los Angeles machine for 500 revolutions. Based on the experimental results and analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Untreated RCA exhibits inferior physical properties compared to NCA, such as lower specific gravity and higher water absorption. Its mechanical properties, including abrasion and crushing values, are also significantly worse than those of NCA. These deficiencies directly result in reduced bulk density, compressive strength, and elastic modulus of the concrete, especially at high substitution levels (>50%).

The TMT method proved effective in enhancing the quality of RCA. The combined heating and grinding processes successfully removed a substantial portion of the adhered old mortar, reduced aggregate porosity, increased specific gravity, and lowered both abrasion and crushing values.

Concrete incorporating TRCA demonstrated superior mechanical performance compared to RCA concrete, particularly at substitution levels of 25–50%. The compressive strength and elastic modulus of TRCA50 were only slightly lower than those of the reference concrete, making it a viable alternative for mid-grade structural applications.

SEM observations revealed that the quality of the ITZ in TRCA concrete was significantly better than in RCA concrete. The cleaner surface of TRCA led to a denser, more homogeneous transition zone with stronger integration into the new mortar, contributing to the enhanced mechanical strength of the concrete.

There is substantial potential in utilizing laboratory concrete waste as a source of recycled aggregates. Moreover, this study highlights the importance of determining the optimal ratio between steel ball weight and aggregate mass during the ball milling process to achieve more precise and efficient results. Overall, the TMT method has proven effective in enhancing the viability of RCA as a substitute for natural coarse aggregate. TRCA can thus be recommended as an alternative material for environmentally friendly concrete, particularly at substitution levels of ≤50%.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N. and F.G.; methodology, N. and F.G.; formal analysis, N. and F.G.; investigation, N. and F.G.; data curation, F.G.; writing—original draft preparation, F.G.; writing—review and editing, N. and F.G.; supervision, N.; project administration, N.; funding acquisition, N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by State University of Malang.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the laboratory staff and students at the Construction Materials Technology Laboratory and Structural Laboratory of the Department of Civil Engineering and Planning, State University of Malang.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RCA |

Recycled Concrete Aggregate |

| TRCA |

Treated Recycled Concrete Aggregate |

| TMT |

Thermal-Mechanical Treatment |

| Sd

|

Relative specific gravity (Oven Dry) |

| Ss

|

Relative specific gravity (SSD) |

| Sa

|

Apparent specific gravity |

References

- Freedonia Group. Global Construction Aggregates; 2019. https://www.freedoniagroup.com/industry-study/global-construction-aggregates-3742.htm (accessed 2025-06-15).

- Zhang, P.; Wang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, S. Effect of Recycled Aggregate and Slag as Substitutes for Natural Aggregate and Cement on the Properties of Concrete: A Review. Journal of Renewable Materials. Tech Science Press 2023, pp 1853–1879. [CrossRef]

- Assefa, G.; Gebregziabher, A. Environmental Impact and Sustainability of Aggregate Production in Ethiopia. In Sandy Materials in Civil Engineering; Nemati, S., Tahmoorian, F., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2020.

- Vijerathne, D.; Wahala, S.; Illankoon, C. Impact of Crushed Natural Aggregate on Environmental Footprint of the Construction Industry: Enhancing Sustainability in Aggregate Production. Buildings 2024, 14 (9). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Huang, J.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, H. Improving Contractors’ Participation of Resource Utilization in Construction and Demolition Waste through Government Incentives and Punishments. Environ Manage 2022, 70 (4), 666–680. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M. S.; ElKady, H.; Abdel- Gawwad, H. A. Utilization of Construction and Demolition Waste and Synthetic Aggregates. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 43, 103207. [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.; Jeong, J. G.; Palou, M.; Park, K. Mechanical Behavior of Fine Recycled Concrete Aggregate Concrete with The Mineral Admixtures. Materials 2020, 13 (10). [CrossRef]

- Younes, A.; Elbeltagi, E.; Diab, A.; Tarsi, G.; Saeed, F.; Sangiorgi, C. Incorporating Coarse and Fine Recycled Aggregates Into Concrete Mixes: Mechanical Characterization and Environmental Impact. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 2024, 26 (1), 654–668. [CrossRef]

- Tam, V. W. Y.; Soomro, M.; Evangelista, A. C. J. Quality Improvement of Recycled Concrete Aggregate by Removal Of Residual Mortar: A Comprehensive Review of Approaches Adopted. Construction and Building Materials. Elsevier Ltd. June 21, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Makul, N.; Fediuk, R.; Amran, M.; Zeyad, A. M.; Murali, G.; Vatin, N.; Klyuev, S.; Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Vasilev, Y. Use of Recycled Concrete Aggregates in Production of Green Cement-Based Concrete Composites: A Review. Crystals. MDPI AG March 1, 2021, pp 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Alibeigibeni, A.; Stochino, F.; Zucca, M.; Gayarre, F. L. Enhancing Concrete Sustainability: A Critical Review of the Performance of Recycled Concrete Aggregates (RCAs) in Structural Concrete. Buildings. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI) April 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Wong, H.; Qiao, X.; Cheeseman, C. Developing Circular Concrete: Acid Treatment of Waste Concrete Fines. J Clean Prod 2022, 365. [CrossRef]

- Shaban, W. M.; Yang, J.; Su, H.; Mo, K. H.; Li, L.; Xie, J. Quality Improvement Techniques for Recycled Concrete Aggregate: A Review. Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology. Japan Concrete Institute April 1, 2019, pp 151–167. [CrossRef]

- Arulkumar, V.; Nguyen, T.; Tran, N.; Black, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Ngo, T. Thermo-Mechanical Treatment for Enhancing the Properties of Recycled Concrete Aggregate. Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology 2025, 23 (3), 168–183. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Agrawal, H.; Chaudhary, S. Thermo-Mechanical Treatment as an Upcycling Strategy for Mixed Recycled Aggregate. Constr Build Mater 2023, 398. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zhao, H.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Lin, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, X. Enhancing Quality and Strength of Recycled Coarse and Fine Aggregates Through High-Temperature and Ball Milling Treatments: Mechanisms and Cost-Effective Solutions. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 2025, 27 (1), 270–288. [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Mueller, A. Development of Thermo-Mechanical Treatment for Recycling of Used Concrete. Materials and Structures/Materiaux et Constructions 2012, 45 (10), 1487–1495. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Cai, S.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.-F. Recycled Aggregates for Sustainable Construction: Strengthening Strategies and Emerging Frontiers. Materials 2025, 18 (13), 3013. [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Khavarian, M.; Yousefi, A.; Landenberger, B.; Cui, H. Influence of Mechanical Screened Recycled Coarse Aggregates on Properties of Self-Compacting Concrete. Materials 2023, 16 (4). [CrossRef]

- Rakesh Kumar Reddy, R.; Yaragal, S. C.; Sanjay, V. K. Processing of Laboratory Concrete Demolition Waste Using Ball Mill. Mater Today Proc 2023. [CrossRef]

- Villagrán-Zaccardi, Y.; Broodcoorens, L.; Van den Heede, P.; De Belie, N. Fine Recycled Concrete Aggregates Treated by Means of Wastewater and Carbonation Pretreatment. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15 (8). [CrossRef]

- Pawluczuk, E.; Kalinowska-Wichrowska, K.; Bołtryk, M.; Jiménez, J. R.; Fernández, J. M. The Influence of Heat and Mechanical Treatment of Concrete Rubble on The Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Materials 2019, 12 (3). [CrossRef]

- Odero, B. J.; Mutuku, R. N.; Nyomboi, T.; Gariy, Z. A. Contribution of Surface Treatment on Physical and Mechanical Properties of Recycled Concrete Aggregates. Advances in Civil Engineering 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Feng, W.; Chen, Z.; Nong, Y.; Yao, M.; Liu, J. Experimental and Theoretical Investigation on the Thermo-Mechanical Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Containing Recycled Rubber. Front Mater 2021, 8, 655097. [CrossRef]

- Ittyeipe, A.; Thomas, A.; Koodalloor Parasuraman, R. Comparison of The Energy Consumption in The Production of Natural and Recycled Concrete Aggregate: A Case Study in Kerala, India. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2020, 989, 012011. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.; Najjar, M.; Stolz, C.; Haddad, A.; Amario, M.; Boer, D. Multiple Dimensions of Energy Efficiency of Recycled Concrete: A Systematic Review. Energies (Basel) 2024, 17, 3809. [CrossRef]

- Algourdin, N.; Bideux, C.; Mesticou, Z.; Si Larbi, A. High Temperature Performance of Recycled Fine Concrete. Low-carbon Materials and Green Construction 2024, 2 (1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Hubert, J.; Zhao, Z.; Michel, F.; Courard, L. Effect of Crushing Method on the Properties of Produced Recycled Concrete Aggregates. Buildings 2023, 13 (9). [CrossRef]

- Das, J. K.; Deb, S.; Bharali, B. Prediction of Aggregate Impact Values and Aggregate Crushing Values Using Light Compaction Test. Journal of Applied Engineering Sciences 2021, 11 (2), 93–100. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, Z.; Li, T.; Wang, S. The Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of Tailing Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Materials 2024, 17 (5). [CrossRef]

- ASTM International. ASTM C136-06 Standard Test Method for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates; West Conshohocken, 2009. www.astm.org.

- ASTM International. ASTM C33/C33M − 23 Specification for Concrete Aggregates; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, 2023.

- BSN. SNI 7064:2022 Semen Portland Komposit; Jakarta, 2022.

- ASTM International. ASTM C131-06 Standard Test Method for Resistance to Degradation of Small-Size Coarse Aggregate by Abrasion and Impact in the Los Angeles Machine; West Conshohocken, 2009. www.astm.org.

- Ogawa, H.; Nawa, T. Improving the Quality of Recycled Fine Aggregate by Selective Removal of Brittle Defects. Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology 2012, 10 (12), 395–410. [CrossRef]

- BSN. SNI 03-2834-2000 Tata Cara Pembuatan Rencana Campuran Beton Normal; Jakarta, 2000.

- ASTM International. ASTM C29/C 29M-07 Standard Test Method for Bulk Density (“Unit Weight”) and Voids in Aggregate; West Conshohocken, 2007. www.astm.org.

- ASTM International. ASTM C127-07 Standard Test Method for Density, Relative Density (Specific Gravity), and Absorption of Coarse Aggregate; West Conshohocken, 2009. www.astm.org.

- British Standards Institution. BS 812-110:1990 Testing Aggregates. Part 110 Methods for Determination of Aggregate Crushing Value (ACV); British Standards Institution: London, 1990.

- ASTM International. ASTM C469 – 02 Standard Test Method for Static Modulus of Elasticity and Poisson’s Ratio of Concrete in Compression; West Conshohocken, 2009. www.astm.org.

- Yehia, S.; Helal, K.; Abusharkh, A.; Zaher, A.; Istaitiyeh, H. Strength and Durability Evaluation of Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Int J Concr Struct Mater 2015, 9 (2), 219–239. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Remond, S.; Damidot, D.; Xu, W. Influence of Fine Recycled Concrete Aggregates on The Properties of Mortars. Constr Build Mater 2015, 81, 179–186. [CrossRef]

- Kou, S. C.; Poon, C. S. Enhancing The Durability Properties of Concrete Prepared with Coarse Recycled Aggregate. Constr Build Mater 2012, 35, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Akbarnezhad, A.; Ong, K. C. G.; Zhang, M. H.; Tam, C. T.; Foo, T. W. J. Microwave-Assisted Beneficiation of Recycled Concrete Aggregates. Constr Build Mater 2011, 25 (8), 3469–3479. [CrossRef]

- Orozco, C.; Corpuz, M.; Monzon, M. R.; Germar, F. Effects and Optimization of Aggregate Shape, Size, and Paste Volume Ratio of Pervious Concrete Mixtures. 2021, 42, 25–40.

- Duan, Z.; Zhao, W.; Ye, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C. Measurement of Water Absorption of Recycled Aggregate. Materials. MDPI August 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, S. H.; Amjad, M. A. Strength, Water Absorption and Porosity of Concrete Incorporating Natural and Crushed Aggregate. Journal of King Saud University - Engineering Sciences 1996, 8 (1), 109–119. [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zhou, H.; Bian, X.; Chen, X.; Ren, C. Compressive Strength, Permeability, and Abrasion Resistance of Pervious Concrete Incorporating Recycled Aggregate. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16 (10). [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Yao, Y.; Wu, B.; Zhang, W.; He, W.; Fu, Y. The Impact Resistance and Mechanical Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete with Hooked-End and Crimped Steel Fiber. Materials 2022, 15 (19). [CrossRef]

- Malešev, M.; Radonjanin, V.; Marinković, S. Recycled Concrete as Aggregate for Structural Concrete Production. Sustainability 2010, 2 (5), 1204–1225. [CrossRef]

- Sajan, K. C.; Adhikari, R.; Mandal, B.; Gautam, D. Mechanical Characterization of Recycled Concrete Under Various Aggregate Replacement Scenarios. Clean Eng Technol 2022, 7, 100428. [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Liu, H.; Yao, Z.; Tang, Z. Experimental Study on The Compressive Strength, Damping and Interfacial Transition Zone Properties of Modified Recycled Aggregate Concrete. R Soc Open Sci 2019, 6 (12). [CrossRef]

- Memon, S. A.; Bekzhanova, Z.; Murzakarimova, A. A Review of Improvement of Interfacial Transition Zone and Adherent Mortar in Recycled Concrete Aggregate. Buildings. MDPI October 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).