1. Background

The global development depends on the construction industry which is also a main driving force of environmental degradation, thus contributing 8 per cent of worldwide CO₂ emissions by cement production alone (Khaertdinova et al., 2021). Concrete is by far the most common construction material and uses energy and resources intense, natural aggregate extraction and cement production (Gagg, 2014). In light of these impacts, the use of sustainable alternatives such as low carbon fiber reinforced concrete (FRC) with off the shelf industrial by products such as steel slag powder and recycled aggregates (RA) has come to mitigate dependency on natural materials [Rane, 2024]. Plizzari & Mindess (2019) stated that fiber reinforcement (FRC) improves mechanical properties such as tensile strength and crack resistance. Nevertheless, conventional FRC relies on nonrenewable resources, and this necessitates the development of innovative solutions based on recycled and waste materials, especially in areas with plenty of industrial by products. Fiber reinforced concrete (FRC) is steel, synthetic, or natural fibers, added into the concrete matrix to improve durability and performance (Labib, 2018). Micro-cracks are bridged by these fibers to improve ductility and reduce the need of traditional steel reinforcement (Paul et al., 2020). Waste steel fibers (such as those from discarded rivets in steel industry) have been recently explored as a sustainable alternative to virgin fibers (Grover & Kumar, 2022). Recycled concrete aggregates (RCA) obtained from construction and demolition waste are similar to ecofriendly substitute of natural aggregates which help in reducing landfill use, conserving resources (Fanijo 2023). RCA adoption is limited in developing countries such as Iraq/Kurdistan region because recycling infrastructure is not developed (Aziz et al., 2023). Another promising material is the steel slag, a steel manufacturing by-product, used in the applications of roads construction and production of cement due to the high strength and skid resistance capabilities of this material (Song et al., 2021). However, its use in the construction sector of developing countries is minimal, which is a missed opportunity for the development of the country (Kumar & Shukla, 2023). From these innovations, fiber reinforced concrete (FRC) has become an attractive solution, particularly for applications needing increased crack resistance, tensile strength and overall durability. Steel fibers are especially useful because of their high stiffness and crack bridging abilities (Plizzari & Mindess, 2019; Hassan & Saeed, 2024). Nevertheless, conventional fibers are produced from virgin resources, which cancels out the sustainability advantages. Research conducted by Grover & Kumar (2022) and Paul et al. (2020) demonstrated that the use of waste steel fibers (WSFs) obtained from industrial by-products such as rivets can offer similar mechanical reinforcement at a reduced environmental impact and solution of the problem of metal waste disposal. In addition, the use of Recycled Concrete Aggregates (RCA) which are processed from demolition waste is another sustainable option. Although RCA is known to have higher porosity and water absorption because of residual mortar, optimized processing methods have been promising. For instance, Papachristoforou et al. (2020) showed that RCA can maintain up to 90% of the compressive strength of conventional concrete if it is cleaned and graded properly. The European example of reaching over 90% recycling rates for construction and demolition waste demonstrates the possibility of RCA incorporation into normal concrete use (Arm et al., 2016). Steel Slag Powder (SSP)—a by-product of steel manufacturing—has been found to have pozzolanic properties and high levels of calcium and iron oxides and thus has been found to enhance mechanical performance and durability (Shi, 2005; Song et al., 2021). According to Chiang and Pan (2017), steel slag aggregates increase abrasion resistance and structural strength in pavement applications, but volumetric instability poses a problem that requires attention to quality control. Other studies have also started to examine the effects of using RCA, SSP and steel fibers, separately. Kryeziu et al. (2023) noted that slag may reduce the strength loss that is usually experienced in RCA, while the angularity of RCA promotes improved particle interlock and crack resistance. Similarly, Papachristoforou et al. (2020) reported that slag aggregates enhanced high-temperature resistance in FRC. Although these promising results exist, gaps still exist in assessing combined systems with multiple recycled components, especially in developing countries such as Iraq/Kurdistan where recycling infrastructure is underdeveloped (Aziz et al., 2023). The results reported in previous studies for example from Liu et al. (2016), who showed that type of aggregate and fiber interaction plays a significant role in tensile stress transfer and Mohamed and Zuaiter (2024), who indicated that slag based FRC needs a delicate dosage of fibers to prevent heterogeneity. By using locally available waste materials, this study adds a scalable, environmentally friendly solution for structural concrete production that is in line with circular economy principles and climate resilience objectives. The next sections describe the experimental methodology, results, comparative analysis with literature, and practical recommendations for applying in construction systems of developing regions. Although there is growing interest in sustainable concrete, critical gaps remain in the research on slag based low carbon FRC with single or multi-source RCA and waste steel fibers (Fanijo et al., 2023; Candido, 2021). Gap filling done in this study entails investigation of the mechanical properties, durability and sustainability of slag based FRC with processed recycled concrete aggregate (PRCA), unprocessed natural aggregate (UNA) reinforced with WSRF. Compressive strength, crack resistance, and environmental impact are evaluated in the research and the results will be practical guidelines for sustainable construction industry. Through use of locally available waste materials, this study makes contribution to build the global reduction efforts of the construction industry carbon footprint and circular economy. This study fills these research gaps by experimentally studying a low-carbon FRC mix that consists of steel slag powder (15% cement replacement), processed RCA (40% coarse aggregate replacement), and different dosages of waste steel rivet fibers (0%–1.4%). Mechanical performance (compressive and tensile strength), physical properties (density and absorption), and failure modes were evaluated to identify the best mix that would balance sustainability with structural performance.

2. Methodology

The aim of this research was to develop and evaluate the performance of sustainable low carbon fiber reinforced concrete (FRC) made with processed recycled concrete aggregates (PRCA), waste steel rivet fibers (WSRF) and steel slag powder (SSP). The methodology was material selection formulating the mix design, specimen preparation, mechanical and durability testing, and result analyses.

Steel slag powder as showed in

Error! Reference source not found. was used in this study as a partial replacement for cement in concrete mix designs to evaluate its effects on the mechanical and durability properties of concrete. Steel slag is a byproduct of the steel making process and some types are rich in calcium, silica, and iron compounds, and thus it is a potential supplementary cementitious material. The steel slag was oven dried and ground into a fine powder that made it through a No. 200 (75µm) sieve was utilized as a powder and cement substitute prior to use to improve its reactivity and to ensure uniform blending with other concrete ingredients. To maintain a balance between mechanical properties, workability, overall performance, and environmental issues that determine the replacement level (15%) of this type of steel slag, it was necessary to review the published literature on steel slag powder with similar chemical and physical properties and to perform some trial mixtures. Chemical composition of SSP is presented in

Table 1.

Figure 1.

a-(cement powder), b-(steel slag powder).

Figure 1.

a-(cement powder), b-(steel slag powder).

Table 1.

Chemical Composition Comparison Between Cement and Steel Slag Powder.

Table 1.

Chemical Composition Comparison Between Cement and Steel Slag Powder.

| Oxide/Element |

Cement (%) |

Steel Slag Powder (%) |

| CaO (Calcium Oxide) |

66.2 |

36.2 |

| SiO₂ (Silicon Dioxide) |

14.6 |

19.7 |

| MgO (Magnesium Oxide) |

4.1 |

3.6 |

| SO₃ (Sulfur Trioxide) |

4.1 |

0.1 |

| Al₂O₃ (Aluminum Oxide) |

4.0 |

5.2 |

| Fe₂O₃ (Ferric Oxide) |

3.7 |

31.9 |

| K₂O (Potassium Oxide) |

2.5 |

0.1 |

| Others |

0.2 |

2.6 |

Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) conforming to ASTM C150 and having a specific gravity of 3.15 was the primary binder used. The cement had a high calcium oxide (CaO) content of 66.2% and relatively lower contents of silicon dioxide (SiO₂ – 14.6%), iron oxide (Fe₂O₃ – 3.8%), sulfate (SO₃ – 4.1%) and potassium oxide (K₂O – 2.5%). Incorporation of SSP as a partial cement replacement at 15% by weight of cement was done to reduce the environmental impact of cement use. Chemical composition of cement is presented in

Table 1.

Natural river sand with maximum particle size of 4.75 mm, specific gravity of 2.6 and water absorption capacity of 1.99% was used as the fine aggregate. Crushed stone with a nominal maximum size of 12.5 mm, specific gravity of 2.638 and water absorption of 0.62% was used as coarse aggregate (

Figure 2). Natural coarse aggregate was obtained at a low price from a local construction materials market in Soran, Iraqi Kurdistan. It was dirty, not cleaned, and not well graded). Recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) (

Figure 2) was single sourced from a demolition building and processed (crushed in Soran/Kurdistan/Iraq crusher plant as shown in

Error! Reference source not found.) cleaned, old cement pasted removed or reduced and graded). To make the concrete as a sustainable construction material the natural coarse aggregate were replaced at 40% (25% 6mm aggregate + 25% 8mm aggregate + 50% 12.5mm aggregate) by RCA to evaluate its effect on the concrete’s fresh, durability, and mechanical performance. Physical properties of natural fine, natural course, and recycled concrete aggregates are presented in

Table 2.

Figure 2.

a-(NCA 12.5mm) b-(RCA 6mm) c-(RCA 8mm) d-(RCA 12.5mm).

Figure 2.

a-(NCA 12.5mm) b-(RCA 6mm) c-(RCA 8mm) d-(RCA 12.5mm).

Table 2.

Physical Properties of NFA, NCA, and RCA.

Table 2.

Physical Properties of NFA, NCA, and RCA.

| PROPERTY |

NFA |

NCA |

RCA |

| TYPE |

Natural River Sand |

Natural Crushed Stone |

Processed Demolished Concrete |

| MAXIMUM SIZE (MM) |

4.75 |

12.5 |

12.5 |

| SPECIFIC GRAVITY (SSD) |

2.60 |

2.638 |

2.42–2.55 |

| WATER ABSORPTION (%) |

1.99 |

0.62 |

3.5–6.0 |

| SHAPE |

Rounded |

Angular |

Angular with low adhered paste |

| SURFACE TEXTURE |

Smooth |

Rough |

Rougher due to residual paste |

| CLEANLINESS (IMPURITIES CONTENT) |

Low |

High |

Clean |

| GRADATION |

Well-graded |

Low graded |

Well-graded (after processing) |

| SOURCE |

Local River |

Local Quarry |

Soran City Demolition Waste |

The concrete mixes were prepared with the WSRF at different replacement levels by concrete volume fraction (0%, 0.2%, 0.8%, and 1.4%). Reviewing literature justifies the choice of 0.8% WSRF content as optimal for performance and workability. Preparations were made for each mix according to standards’ procedures and keeping a constant water-to-binder (W/B) ratio of 0.49. To achieve homogeneity, the materials were mixed thoroughly using a mechanical mixer. Workability of the fresh concrete was tested, hardened samples were cured and tested to determine the effect of SSP, PRCA and WSRF on overall concrete performance. To improve the tensile properties and crack resistance of the concrete WSRF Shown in Error! Reference source not found., which are obtained from discarded rivets and waste products from the local door and window manufacturing industries in Soran, Kurdistan, Iraq. The average length and diameter of fibers measured 22.54 mm and 1.63 mm respectively, and the density was 7750 kg/m³ as other properties presented in Error! Reference source not found..

Table 3.

Mechanical and Geometrical Properties of WSRF.

Table 3.

Mechanical and Geometrical Properties of WSRF.

| PROPERTY |

VALUE |

UNIT / DESCRIPTION |

| FIBER TYPE |

Waste Steel Rivet Fibers |

From discarded rivets and metal scraps |

| SHAPE |

Straight, low ribbed |

As collected from waste |

| LENGTH (AVE) |

22.54 |

mm |

| DIAMETER (AVE) |

1.63 |

mm |

| ASPECT RATIO (L/D) |

13.83 |

— |

| DENSITY |

7750 |

kg/m³ |

| SOURCE |

Local manufacturers |

Soran, Kurdistan Region |

A polycarboxylate based high range water reducing admixture conforming to ASTM C494 was used to ensure adequate workability with a low water to cement ratio. A reduced water to binder ratio (W/B) of 0.49 was used with the superplasticizer at 0.5% - 1% of the cement weight, to achieve slumps between 35mm – 65mm without compromising workability or compaction. Each mix was evaluated for its workability with a standard slump test (Herki, 2017). The mix proportions, by weight, were 1:2:3 (binder:NFA:NCA).

Table 4 presents the weight of ingredients in all sixteen concrete mixtures.

Table 4.

Concrete mixture proportions.

Table 4.

Concrete mixture proportions.

| Mix No |

Mix Code |

WSRF (%) |

SSP (%) |

Cement (kg/m3) |

NFA (kg/m3) |

NCA (kg/m3) |

RCA (%) |

Water (kg/m3) |

SP (%) |

| 1 |

C |

0 |

0 |

380 |

760 |

1140 |

0 |

185 |

0.5 |

| 2 |

C0.2 |

0.2 |

0 |

380 |

760 |

1140 |

0 |

185 |

0.5 |

| 3 |

C0.8 |

0.8 |

0 |

380 |

760 |

1140 |

0 |

185 |

0.75 |

| 4 |

C1.4 |

1.4 |

0 |

380 |

760 |

1140 |

0 |

185 |

1.0 |

| 5 |

S |

0 |

15 |

323 |

760 |

1140 |

0 |

185 |

0.5 |

| 6 |

S0.2 |

0.2 |

15 |

323 |

760 |

1140 |

0 |

185 |

0.5 |

| 7 |

S0.8 |

0.8 |

15 |

323 |

760 |

1140 |

0 |

185 |

0.75 |

| 8 |

S1.4 |

1.4 |

15 |

323 |

760 |

1140 |

0 |

185 |

1.0 |

| 9 |

SRA |

0 |

15 |

323 |

760 |

684 |

40 |

185 |

0.5 |

| 10 |

SRA0.2 |

0.2 |

15 |

323 |

760 |

684 |

40 |

185 |

0.5 |

| 11 |

SRA0.8 |

0.8 |

15 |

323 |

760 |

684 |

40 |

185 |

0.75 |

| 12 |

SRA1.4 |

1.4 |

15 |

323 |

760 |

684 |

40 |

185 |

1.0 |

| 13 |

RA |

0 |

0 |

380 |

760 |

684 |

40 |

185 |

0.5 |

| 14 |

RA0.2 |

0.2 |

0 |

380 |

760 |

684 |

40 |

185 |

0.5 |

| 15 |

RA0.8 |

0.8 |

0 |

380 |

760 |

684 |

40 |

185 |

0.75 |

| 16 |

RA1.4 |

1.4 |

0 |

380 |

760 |

684 |

40 |

185 |

1.0 |

Figure 5.

Curing Concrete specimens.

Figure 5.

Curing Concrete specimens.

Specimens were demolded after 24 hours and cured in water at 20 ± 2°C until the testing age after casting shown in

Error! Reference source not found.. The development of strength was assessed through mechanical tests conducted at 28 days. A standardized mixing sequence was used to create concrete specimens that would be consistent. Compressive strength according to BS EN-12390 and tensile strength according to ASTM C496 were tested on 100mm cubes, and 200mm length and 100mm diameter cylinder molds (

Figure 6) (Herki, 2022).

For water absorption test of concrete specimens, first, the concrete specimens are oven dried at 105 ± 5°C for 24 hours or to a constant mass Shown in (Herki, 2017). After completely dry, the specimens are cooled to room temperature in a dry environment and weighed to get the dry weight (W₁). The specimens are then fully immersed in clean water for 24 hours after that. After the immersion they are surface dried with a damp cloth and weighed immediately to find the saturated weight (W₂) complied with ASTM C642. The formula for calculating water absorption is WA (%) = [(W₂ – W₁) / W₁] × 100. This value represents the percentage of water absorbed by the concrete, which is a measure of porosity of the material and indirectly its durability.

The volume of the concrete specimen is determined (usually calculated from the known dimensions of the standard mold) and the dry weight is used to calculate dry density. This gives the density of the concrete in a dry state and gives insight into its compaction quality. Water absorption (Herki, 2017) and density (Herki, 2024) tests are both essential to the evaluation of concrete mixes containing alternative materials such as SSP and RCA.

3. Results

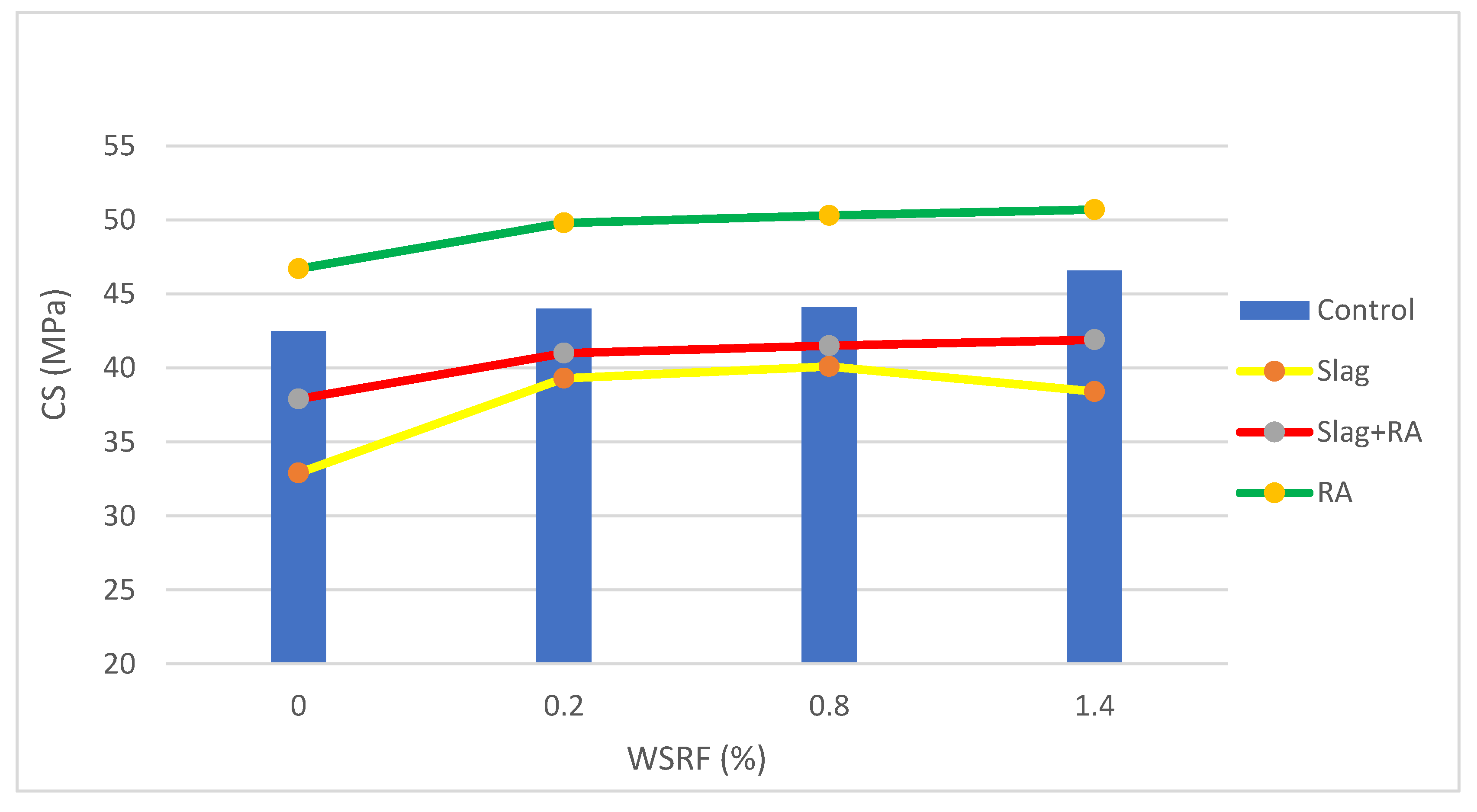

3.1. Compressive Strength

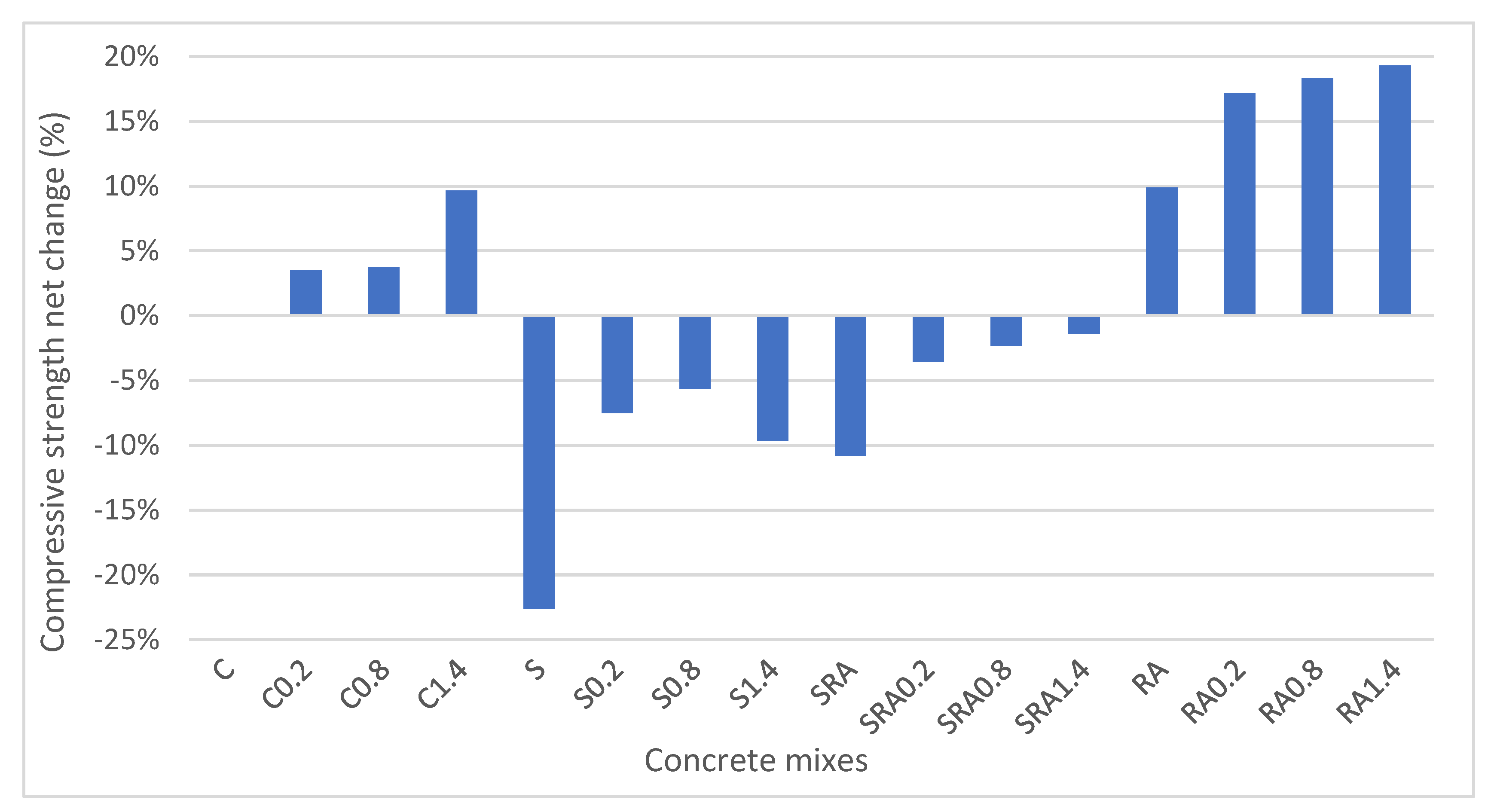

Results of the 28-day compressive strength are presented for concrete mixes containing varying volumes of steel fiber (0%, 0.2%, 0.8%, and 1.4%). The mixes are classified as Control, SSP, Slag+RA, and RA Shown in Error! Reference source not found.. Strength increases from 42.5 MPa at 0% fiber content to 44.0 MPa at 0.2%, 44.1 MPa at 0.8% and reaches the highest value of 46.6 MPa at 1.4% fiber in the Control group (no slag or recycled aggregates). The steady increase in fiber reinforcement indicates the beneficial effect of fiber reinforcement on conventional concrete. The compressive strength at 28 days for the Slag mixes begins at 32.9 MPa without fibers. Strength is greatly improved upon with fibers, particularly to 40.1 MPa at 0.8% fiber content. Nevertheless, the strength falls slightly to 38.4 MPa at 1.4%, indicating a possible optimal fiber content of around 0.8% for this mix. Strength increases monotonically with fiber addition in the Slag/RA mixes: from 37.9 to 41.0 MPa at 0.2%, 41.5 MPa at 0.8%, and 41.9 MPa at 1.4%. This increase is more stable here indicating that the combined use of slag and recycled aggregates still benefits from fiber reinforcement. All mixes had an increase in the compressive strength by 28 days with increasing fiber volume, although the amount of increase and the fiber content that provides optimum strength is slightly dependent on mix composition.

Figure 7.

Compressive strength of concrete mixes.

Figure 7.

Compressive strength of concrete mixes.

Figure 8 shows the net change in compressive strength of all concrete mixes compared to control mix. The trends in 28-day compressive strength for all mixes are observed and show that steel fibers play a reinforcing role and that mix composition plays a role. This is supported by Yoshinaka et al. (2016) who suggest that the fibers do not contain disruptive additives, have the ability to bridge microcracks, delay crack propagation and enhance the post crack load distribution utilized in a homogeneous matrix. The sharp improvement up to 40.1 MPa at 0.8% is attributed to the pozzolanic reaction of slag improving matrix densification and the synergy with fibers at optimal dosage as shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, while a slight decline at 1.4% suggests that excessive fibers may disrupt the matrix or reduce workability, which is in agreement with Mohamed and Zuaiter (2024) on slag’s sensitivity to fiber induced heterogeneity. The gradual fiber reinforcement of the strength seems to stabilize the distribution of internal stress and works with the reactivity of slag to compensate for RCA’s inherent weakness, which seems to be in line with Park (2008). Here, values are not listed, but similar studies show that RCA surface roughness enhances mechanical interlock with fibers and sustained strength gains in the RA mix. Overall, the compressive strength improvement is more pronounced in mixes where the matrix quality and fiber dispersion are in balance, and 0.8% fiber dosage is optimal in slag-based mixes and higher dosages (1.4%) are more effective in conventional concrete. When compared to concrete made with unprocessed natural aggregates (NCA), concrete made with well-processed recycled concrete aggregates (RCA)—that is, aggregates that have been crushed, cleaned, excess old cement paste reduced/removed, and well graded—achieved equivalent or even greater compressive strength. Unprocessed NCA frequently contains contaminants including dirt, clay, and organic content, which can result in poor compaction, weaker interfacial bonding, and uneven performance. However, because of its rough texture and angularity, properly prepared RCA offers better paste-aggregate interaction.

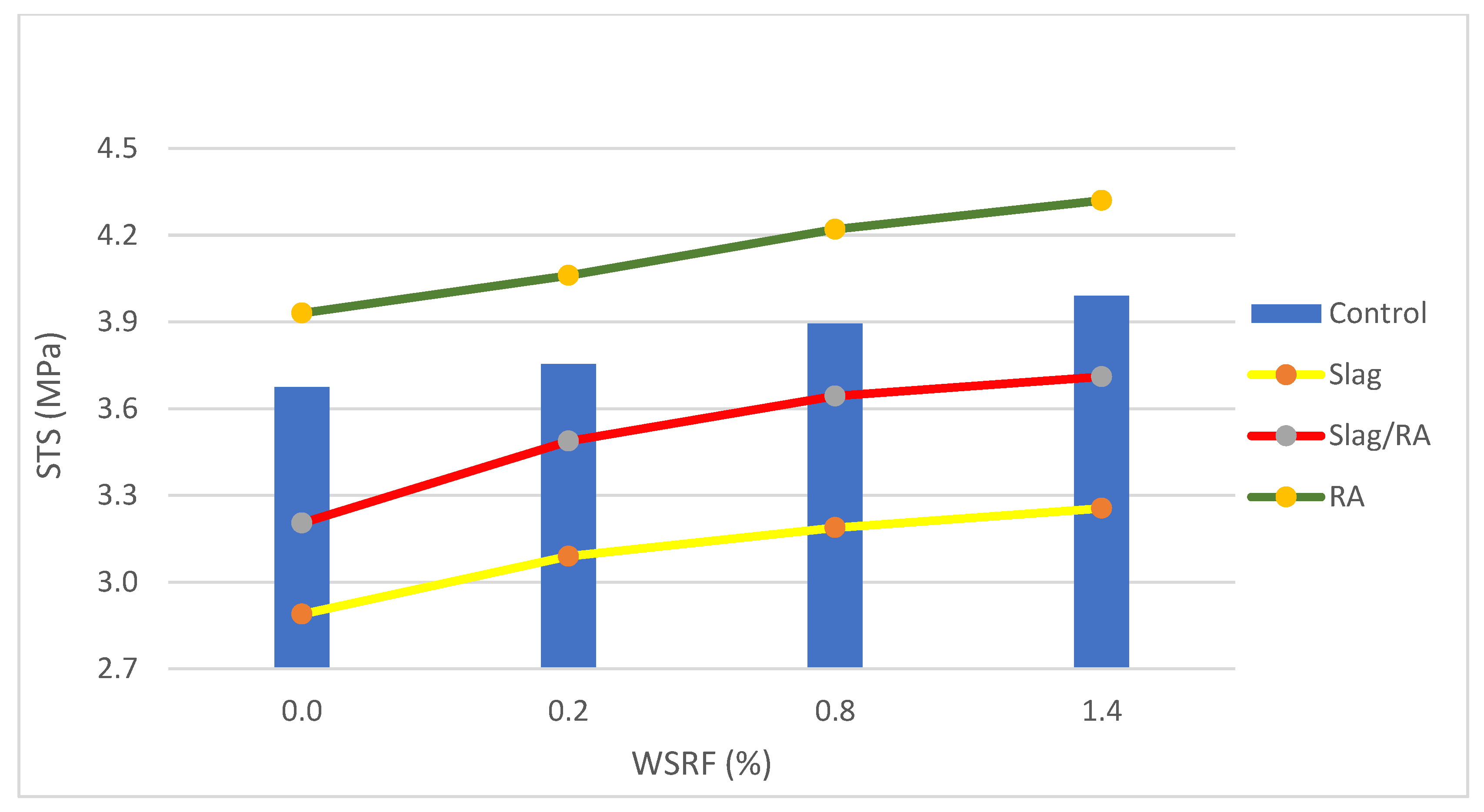

3.2. Splitting Tensile Strength

Results from the experiments show the evolution of indirect tensile strength in sixteen concrete mixtures with increasing exposure levels as shown in

Error! Reference source not found..

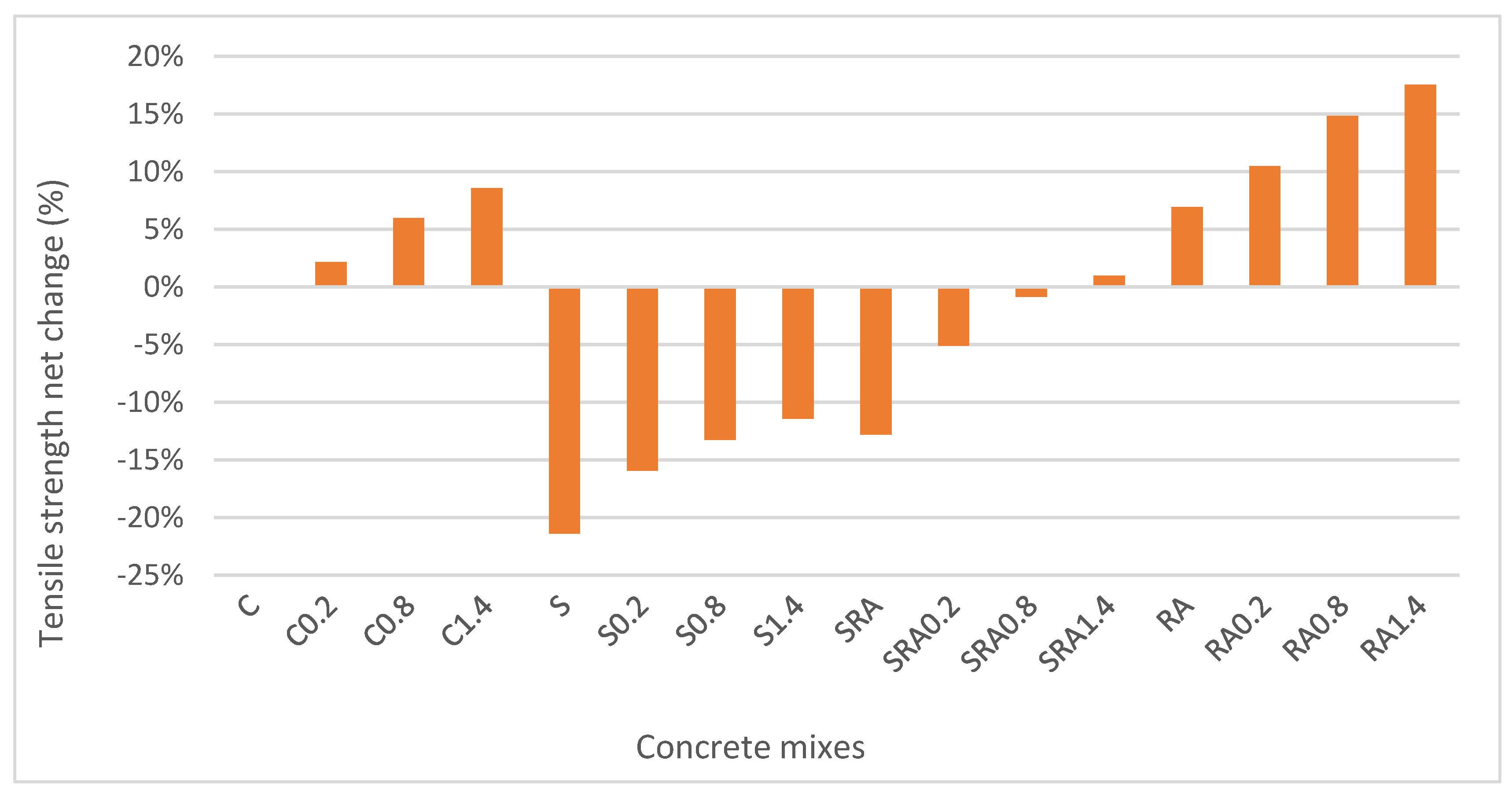

Figure 10 shows the net change in tensile strength of concrete mixes compared with control mix. Tensile strength increases steadily as well from baseline (0% fiber) to maximum level (1.4% fiber volume) for the control mix (conventional concrete without additives): 3.68 MPa, 3.75 MPa, 3.89 MPa, 3.99 MPa. The 8.4% improvement in this case represents the expected maturation of ordinary concrete where the cementitious matrix is continually hydrated to strengthen as observed by Felekoğlu Tosun and Baradan (2009). However, the behavior for slag modified concrete starts with a reduced baseline tensile strength (2.89 MPa), which is likely caused by the slower initial reactivity of the supplementary cementitious material. Nevertheless, the progressive pozzolanic contribution of steel slag is confirmed by the more pronounced 12.5% increase in tensile strength to 3.25 MPa at 1.4% exposure. It is characteristic of slag blended systems that have long term performance benefits over initial strength reductions. This is in line with Varghese et al. (2019) findings.

Figure 9.

Tensile strength of concrete mixes.

Figure 9.

Tensile strength of concrete mixes.

At peak exposure, the hybrid slag/RA mixture has intermediate characteristics, starting at 3.20 MPa and increasing 15.9% to 3.71 MPa. The recycled aggregate mix performs better than plain slag concrete, achieving high tensile strengths, however, remaining approximately 7% lower than the control mix at maximum level, thus while some compensation is provided by the recycled aggregates for the initial weakness of plain slag concrete, they cannot provide the same tensile performance as conventional concrete as shown in Error! Reference source not found..

Figure 10.

Tensile strength net change.

Figure 10.

Tensile strength net change.

Notably, the RA exclusive mix possesses the highest initial (3.93 MPa) and final (4.32 MPa) strengths, which represents a 9.9% improvement over the RA inclusive mix. Based on this performance, recycled aggregate is thought to act more advantageously with the cement matrix than when combined with slag, but because better stress transfer to the aggregate occurs. If proper recycling aggregate processing yields concrete with improved tensile properties, then the outperformance of the RA mix over control and modified mixes is consistent. The practical implications of these findings are for projects emphasizing early age tensile strength, conventional or RA exclusive mixes should be applied; slag containing mixes require longer curing time but are comparable to performance wise when initial strength is not critical; and slag/RA combination lies in between and may be appropriate for applications that require a compromise between sustainability and performance. In terms of performance, RA concrete has a superior tensile performance which supports the use of RA concrete in structural elements under flexural stresses, as well as advancing circular economy objectives of construction. This is because the processed RA mix outperforms all others including unprocessed NA, from 3.93 MPa to 4.32 MPa, which indicates the beneficial interaction between coarse recycled aggregates and cement paste, which improves tensile stress transfer and fiber anchorage in particular at moderate fiber levels (Liu et al., 2016).

3.2.1. Analysis of Splitting Tensile Failure Modes

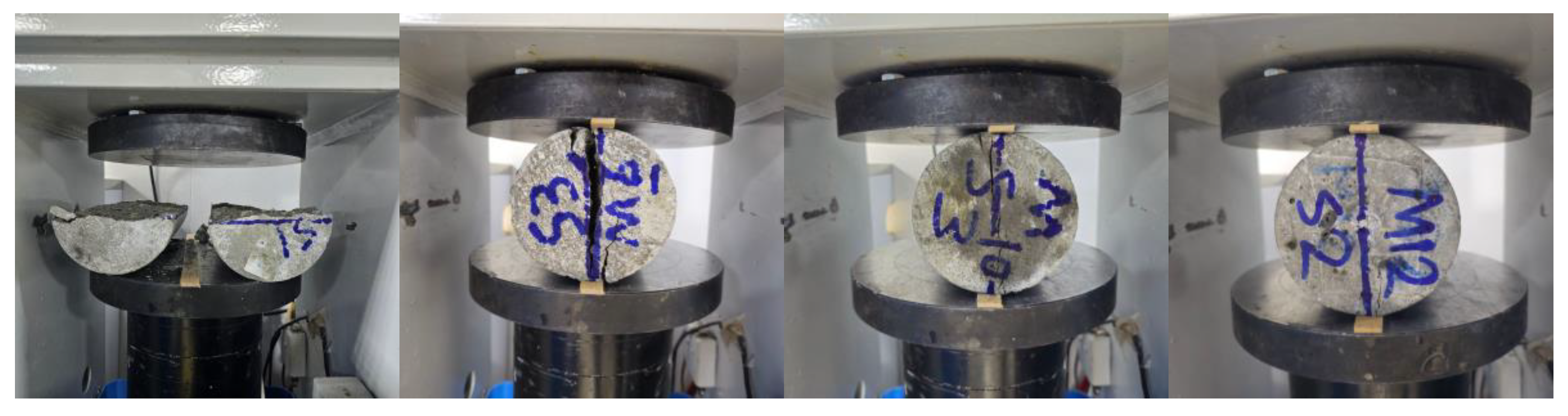

In this section, the failure behavior of cylindrical concrete specimens tested according to ASTM C496 in splitting tensile strength testing is discussed. Crack pattern, post crack behavior and general failure mechanism are studied as a function of different dosages of steel fibers (0%, 0.2%, 0.8%, 1.4%). The observed failure modes for each fiber content level are shown in figures.

3.2.1.1. Plain Concrete – 0% WSRF

The specimen with 0% steel fiber represents the baseline behavior of unreinforced concrete under tensile stress. As shown in Error! Reference source not found.1, the failure mode is purely brittle. A vertical clean sharp crack forms across the diameter splitting the specimen into two completely detached halves. Once the tensile capacity is exceeded, the crack propagates rapidly with little resistance to crack initiation and no post peak load carrying capacity. No bridging mechanism is visible across the crack, and no energy absorption occurs beyond the peak tensile stress. Such failure is expected in conventional concrete where tensile strength is intrinsically poor, and failure occurs in a catastrophic manner. The 0% fiber specimen fails catastrophically because concrete’s inherently low tensile strength and lack of crack-bridging mechanisms. Once cracking starts, plain concrete cannot resist tensile stress and will fracture rapidly with no energy absorption and post peak load capacity, as reported by Carpinteri and Brighenti (2009).

Figure 11.

Failure mode of 0%, 0.2%, 0.8% and 1.4% WSRF for plain concrete.

Figure 11.

Failure mode of 0%, 0.2%, 0.8% and 1.4% WSRF for plain concrete.

3.2.1.2. Low Fiber Content – 0.2% WSRF

The addition of 0.2% steel fibers results in a subtle but meaningful change in the failure mode. As illustrated in Error! Reference source not found., the internal resistance to propagation of the crack pattern remains vertically aligned only with a slight increase in vertical pattern jaggedness. Crack opening fibers engage some fibers that provide minimal bridging action. The specimen still splits into two main halves, but the fracture is less severe than the 0% fiber specimen. Fibers help in distributing tensile stress slightly beyond the initial crack and delay complete failure. The fact that this is a transitional behavior implies that low fiber volumes can still improve crack control and delay brittleness, The 0.2% fiber mix exhibits transitional failure behavior with less severe cracking. Fibers start to bridge microcracks and slightly delay fracture and decrease brittleness. This is in according with Khan (2019), who reported that even low fiber volume improves tensile stress distribution and cracks resistance at early stages of concrete.

3.2.1.3. Moderate Fiber Content – 0.8% WSRF

The specimen with 0.8% fiber content exhibits a significant change in failure mode. Error! Reference source not found. clearly shows a more ductile response. A central vertical crack is still visible, but the two halves are more or less intact, with many fibers bridging across the fracture holding the crack together. This dosage of the fiber reinforcement arrests crack widening and prevents complete structural separation. There is transition from brittle to quasi-ductile failure mode with higher energy absorption and better toughness. This dosage is a threshold above which the fibers dominate post crack load transfer and structural integrity, The quasi-ductile failure of the 0.8% fiber specimen is due to fibers that effectively bridge cracks and prevent separation. This is in agreement with the findings of Carpinteri and Brighenti (2009), who demonstrate that moderate fiber content leads to significant increase in energy absorption, arrest of crack propagation, and ductile behavior in FRC.

3.2.1.4. High Fiber Content – 1.4% WSRF

Error! Reference source not found. presents the most advanced behavior. The specimen with 1.4% steel fiber is observed. The failure is highly controlled here. The specimen shows almost no physical separation, but a fracture line exists, which is very narrow. The tensile stresses are distributed widely and uniformly throughout the internal fiber network, which is dense enough to do so. The fibers still carry loads after matrix cracking, improving the residual tensile capacity. The specimen remains cylindrical, and fibers provide strong pullout resistance. This failure mode signals a material with excellent post peak toughness and crack resistance, a highly ductile material, which is ideal for structural and high-performance concrete applications, The specimen has a high fiber content of 1.4%, and the failure is very ductile with little separation and narrow cracking. Tensile stress is distributed across tens of thousands of fiber networks to maintain integrity post cracking. Liu et al. (2016) agree that high fiber volumes improve pullout resistance, residual strength, and toughness, which are good for structural applications.

Error! Reference source not found.5 summarizes the progressive enhancement in failure characteristics with increasing fiber dosage. At higher fiber contents, the failure transitions from sudden and brittle to ductile and energy absorbing. Minimal crack opening and full post crack structural retention was achieved in the 1.4% fiber sample.

Table 5.

Comparative evaluation of specimen failure mode.

Table 5.

Comparative evaluation of specimen failure mode.

| Fiber Content |

Crack Pattern |

Separation |

Crack Width |

Ductility |

Post-Crack Integrity |

| 0.0% |

Clean, straight |

Full |

Wide |

Brittle |

None |

| 0.2% |

Jagged, vertical |

Partial |

Medium |

Slight |

Low |

| 0.8% |

Stable, bridged |

Minor |

Narrow |

Ductile |

Moderate to High |

| 1.4% |

Bridged, stable |

Low |

Very Narrow |

Highly ductile |

Excellent |

Visual inspection and photographic documentation of the failure modes show that waste steel rivet fibers play a major role in improving the tensile behavior of concrete. On the other hand, plain concrete fails catastrophically when it reaches its tensile limit, but fiber reinforced concrete, especially at higher dosages, fails in a much more desirable way. Fibers contribute to delayed cracking, reduced separation, and post peak load redistribution beginning at 0.2%. The transition to ductile behavior is clearly at 0.8%, and the specimen has advanced mechanical resistance with good crack control at 1.4%. Based on these findings the use of WSRF is compatible with structural applications where tensile performance, resistance to crack formation, and ductility are features.

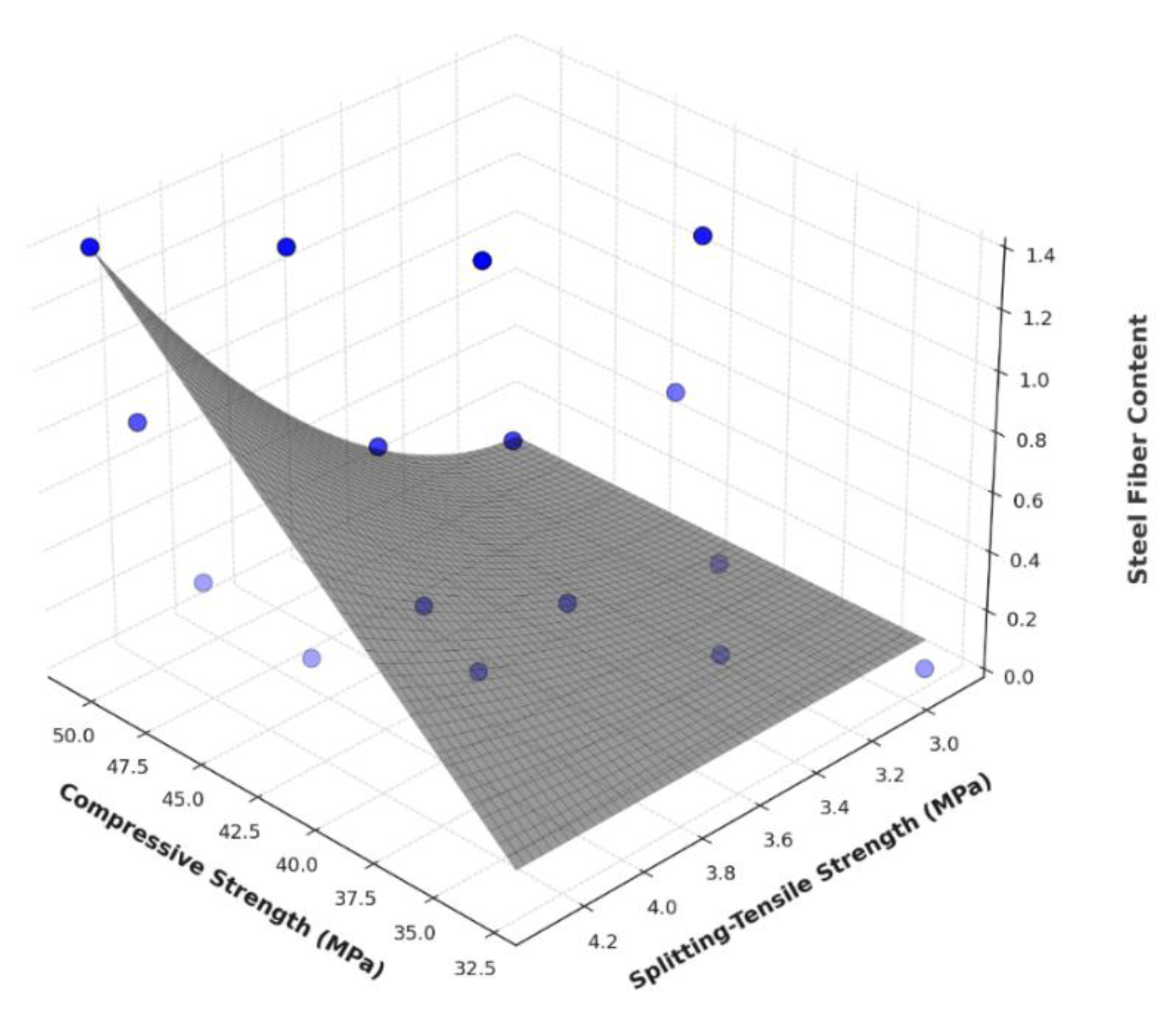

3.3. Relationship Between Compressive and Tensile Strengths, and the Fiber Content

As shown in Error! Reference source not found. the 3D plot shows the relationship between compressive strength, tensile strength and the WSRF content in concrete mixtures. The blue spheres represent the individual experimental data points from different fiber content percentages (0%, 0.2%, 0.8%, and 1.4%) and four types of concrete mixes (Control, Slag, Slag+RA, and RA). Each point accurately reflects the measured compressive and splitting tensile strength at the fiber dosage in each case.

A black curved surface was constructed to visually guide the understanding of how strength properties change as a function of changing fiber content. The compressive and tensile strengths are lower in the lower right corner and the surface begins there and slopes upward to the upper left corner where the strengths and fiber contents are higher. This indicates a positive relationship between the fiber content and mechanical properties as the dosage increases.

Figure 12.

STS and CS curve corresponding to fiber content.

Figure 12.

STS and CS curve corresponding to fiber content.

The compressive and tensile axes are boldly labeled, the fiber content is indicated externally on the right side of the plot by a clear, vertical label, which keeps the style clean and modern and avoids repetitive labeling. What we find out is that this visualization also tells us the general trend and the trend is that as steel fiber content increases, compressive and tensile strength increases, but at different rates based on the mix type. Though there are small local variations at the points, the overall behavior is captured by the carefully curved surface. The compressive and tensile strength are positively correlated with steel fiber content as shown in the 3D plot. According to Plagué, Desmettre and Charron (2017), higher fiber dosage increases crack resistance and load transfer. This trend is then captured in the curved surface of which it shows a clear visualization of this fiber positive gain to strength across mix types.

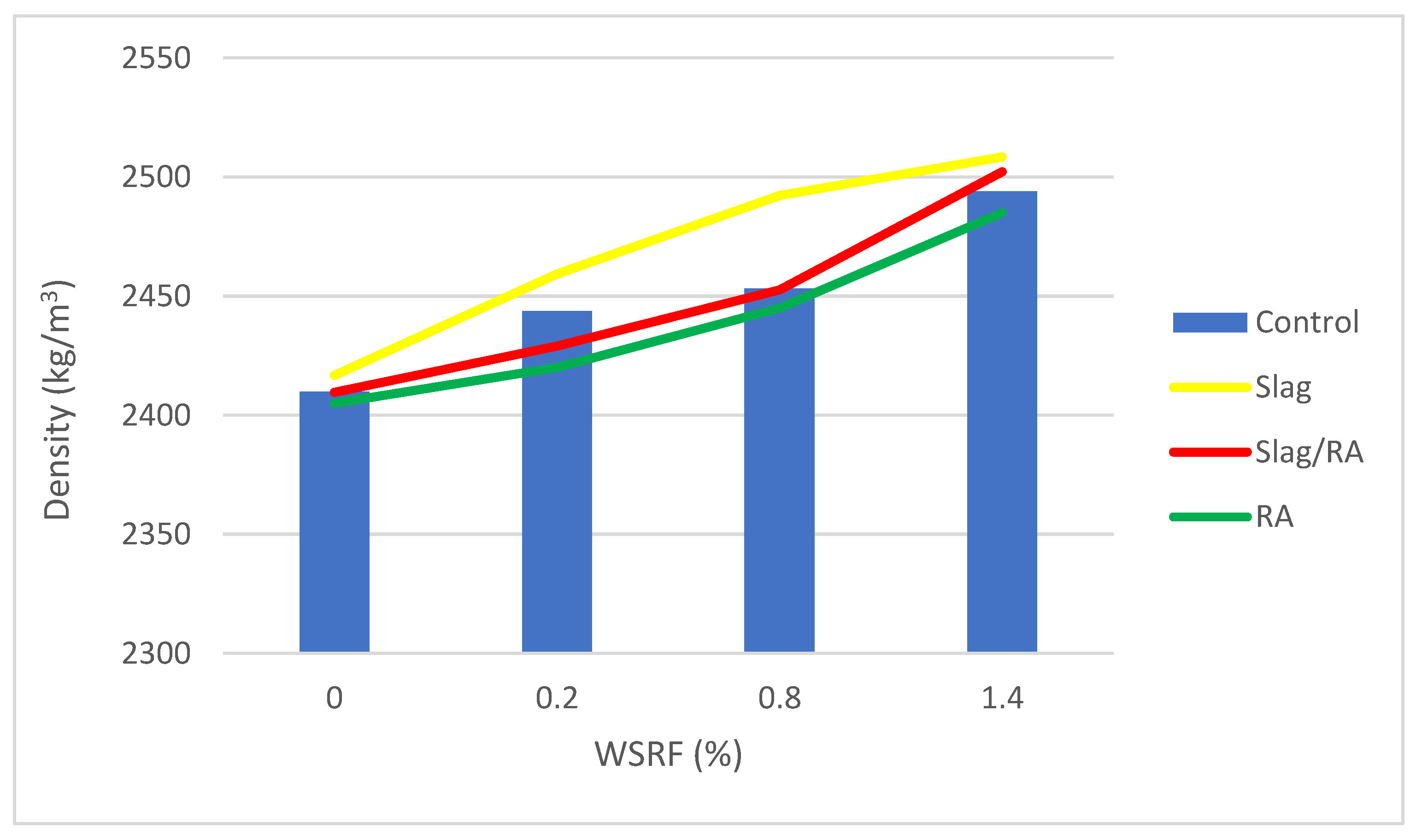

3.4. Dry Density

Figure 13 presents the bulk density (dry) of various concrete mixtures, Control, Slag, Slag+RA, and RA, in kg/m³. Bulk density is defined as the mass per unit volume of dry concrete and is an important property that indicates the material’s compactness, porosity and structural integrity. The Control mix starts at a bulk density of 2410 kg/m³ at 0% content and continues to increase to 2494 kg/m³ at the maximum replacement level (1.4%). This trend upward suggests that the compactness is improving with increasing replacement, possibly due to better particle packing or hydration effects. Once again, the dead load disadvantages of steel fibers are shown. Bulk densities of the Slag mix are consistently greater than those of the control mix at all replacement levels. At 2417 kg/m³ it starts and at the 1.4% level it reaches 2508 kg/m³. The increase is gradual and gradual, implying that slag with a finer particle size and a higher slag specific gravity increase the overall concrete density. This denser structure suggests a lower porosity, and better long-term durability and environmental resistance. The Slag/RA mix has an even stronger trend. It increases continuously from 2410 kg/m³ to 2502 kg/m³ at 1.4% replacement. This shows that recycled aggregates and slag are showing a synergistic effect, resulting in high bulk density, which may indicate that the slag helps with better particle interlocking and lower void content. This combination makes the concrete more compact and potentially more durable. The bulk density of the RA mix also increases from 2405 kg/m³ at 0% to 2485 kg/m³ at 1.4%. Although slightly lower than the slag containing mixtures, it still exhibits a positive trend which supports the notion that recycled aggregates do contribute to density enhancement, albeit to a lesser extent when used without slag. Overall, the bulk densities for the Slag/RA mix are consistently lower than the Slag mix, which in turn is higher than the RA mix, which is higher than the Control mix at all replacement levels. The data clearly shows that among those aggregates the addition of slag and recycled aggregates increase the dry bulk density of concrete which corresponds thereby to the mechanical properties and durability of concrete.

The compactness of concrete mixes is increased by slag and recycled aggregates. Vijayaraghavan, Jude and Thivya (2017) confirm that slag’s fine particles and high specific gravity increase density, and RCA’s angularity increases interlocking. Optimal packing and reduced porosity is indicated by the highest bulk density in the Slag/RA mix.

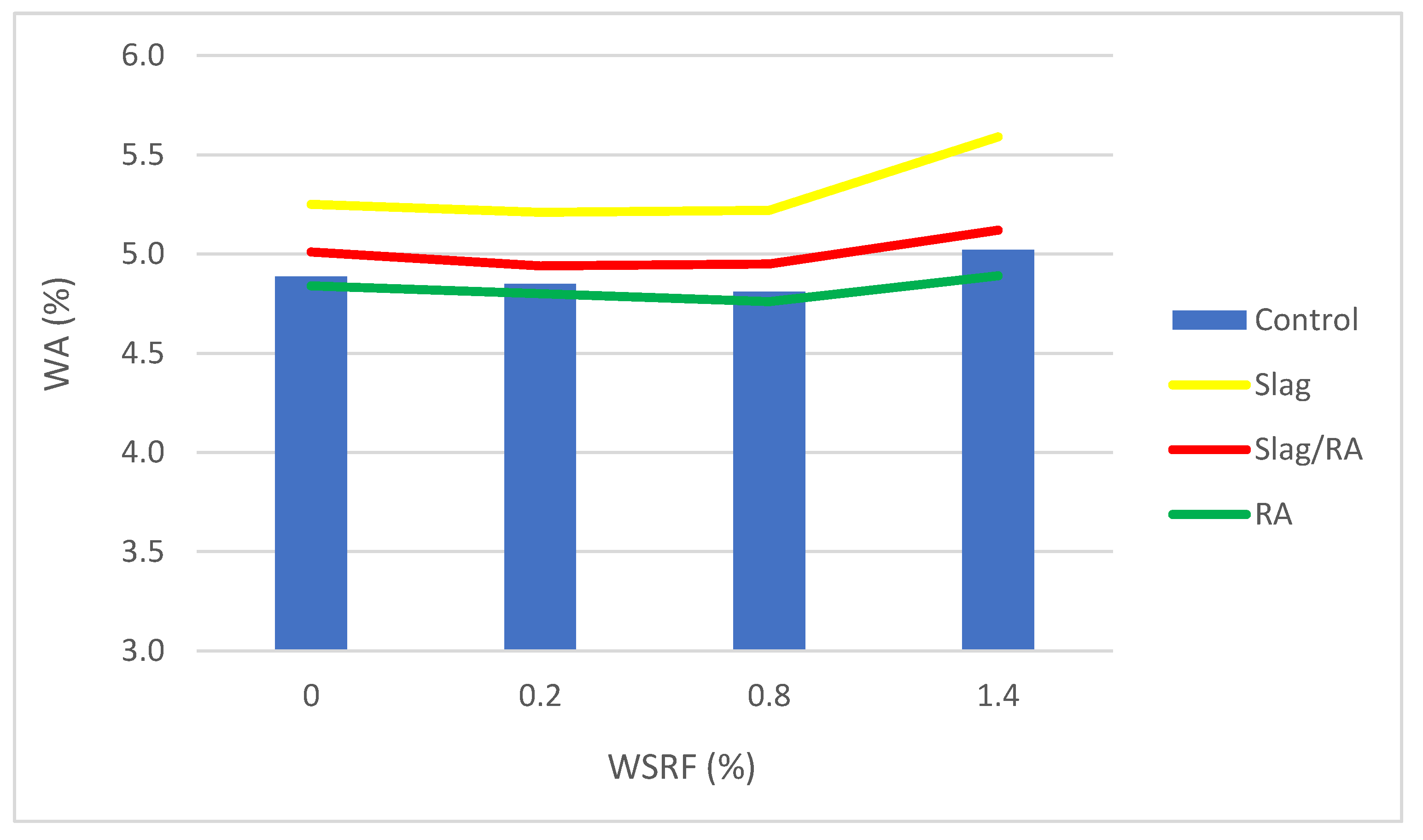

3.5. Absorption

Figure 14 shows the water absorption (%) after 24h immersion for all concrete mixes including Control, Slag, Slag/RA, and RA mixes reinforced with different volumes of waste steel rivet fibers (WSRFs) 0% to 1.4%. Water absorption is an important parameter of porosity and, therefore, durability and resistance of concrete in wet and freeze-thaw conditions. The Slag mix showed the highest absorption among the tested mixes, 5.25% (0% fiber) and 5.59% at 1.4% fiber. This goes against standard expectations that slag should decrease porosity, implying that under the current mix design, slag may induce higher micro-capillarity or incomplete densification – possibly because of excessive fiber dosage inhibiting the pozzolanic activity (Mohamed et al., 2023). The Slag/RA mix demonstrated a slightly lower but stable absorption tendency, increasing from 5.01% to 5.12%. The interaction of slag’s fine particles with the rough texture of recycled aggregates probably enhanced particle packing and reduced pore connectivity. This intermediate behavior is a compromise between the porosity increase from RCA and the densification effects of slag (Mekonen et al., 2024). The Control mix demonstrated moderate absorption values that increased from 4.89% to 5.02% with higher fiber content. The trend implies that fiber clustering at high volumes can cause internal void development, slightly increasing porosity (Khan and Khan, 2025). Interestingly, the RA mix showed the lowest absorption values overall, beginning at 4.84% and decreasing to 4.76% at 0.8% fiber content before rising again. This was surprising because recycled aggregates are usually more porous. However, the processed RA used in this study probably had a denser structure and better surface quality, which would reduce water uptake – as reported by Al-Rekabi et al. (2023). In summary, water absorption was ranked as follows from highest to lowest: Slag > Slag/RA > Control > RA. Moderate fiber content (especially 0.8%) seems to enhance compaction and minimize absorption in most mixes but excessive fiber dosage (>1.0%) may compromise matrix integrity. Such results emphasize the significance of optimized mix design in incorporating alternative materials for durability in sustainable concrete applications.

Figure 14.

Water Absorption of all concrete mixes.

Figure 14.

Water Absorption of all concrete mixes.

4. Conclusions

The present study focused on the development and performance of sustainable low carbon concrete with the use of steel slag powder, processed recycled aggregates (RA), and waste steel rivet fibers (WSRF). Based on experimental results and analysis, the following conclusions are made:

The best balance between compressive and tensile strength in all mixes was achieved with the incorporation of 0.8% WSRF.

Maximum compressive strength was achieved in the Control mix with 1.4% fiber (46.6 MPa) and slag-based mixes up to 40.1 MPa.

As fiber dosage increased, tensile strength improved, and the RA mix recorded the highest tensile value (4.32 MPa), indicating excellent crack resistance.

Water absorption was the lowest in the RA mix (minimum 4.76%); this was a result of improved pore structure due to proper processing.

Slag mixes demonstrated higher absorption values, probably because of micro-capillary effects and delayed densification.

The Slag/RA mix demonstrated stable intermediate values, indicating a synergistic effect of the two materials.

Slump varied from 35mm to 65mm depending on fiber content. Increased fiber dosages usually decreased workability because of internal friction and matrix densification.

Fiber-reinforced specimens showed a transition from brittle to ductile failure, especially at 0.8% and 1.4% fiber dosages.

Crack bridging by WSRFs slowed down the crack propagation and increased the post-crack load bearing capacity.

The mixture of 15% steel slag powder, 40% processed RA, and 0.8% WSRF is suggested for practical application. This mix finds a good balance between mechanical performance, durability and environmental benefits.

The use of industrial and construction waste materials minimized dependency on virgin raw materials and supported circular economy objectives.

Proper processing of RA and slag and fiber optimization are essential for performance and workability. Local governments and industry stakeholders should reward the use of recycled materials by way of green certification and tax relief.

Additional long-term durability tests in real environmental conditions are suggested to justify large-scale application.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department for their assistance and laboratory facilities. The authors express their deep gratitude to the Hend Steel factory for providing the materials. We are also grateful to the local Soran/Barzewa quarry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Dilan Awla and Bengin Herki; Data curation, Aryan Far Sherwani; Formal analysis, Bengin Herki; Methodology, Dilan Awla; Project administration, Bengin Herki; Resources, Dilan Awla; Supervision, Bengin Herki; Writing – original draft, Dilan Awla; Writing – review & editing, Bengin Herki.

References

- Al-Rekabi, A.H. et al. (2023) 'Experimental investigation on sustainable fiber reinforced self-compacting concrete made with treated recycled aggregate,' AIP Conference Proceedings [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Arm, M., Wik, O., Engelsen, C. J., Erlandsson, M., Hjelmar, O., & Wahlström, M. (2016). How Does the European Recovery Target for Construction & Demolition Waste Affect Resource Management? Waste and Biomass Valorization, 8(5), 1491–1504. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C143. Standard Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic-Cement Concrete.

- ASTM C150. (n.d.). Standard Specification for Portland Cement.

- ASTM C494/C494M-24. (2024) Specification for Chemical Admixtures for Concrete.

- ASTM C496. (n.d.). Standard Test Method for Splitting Tensile Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens.

- ASTM C642. Standard Test Method for Density, Absorption, and Voids in Hardened Concrete.

- Aziz, S. Q., Ismael, S. O., & Omar, I. A. (2023). New approaches in solid waste recycling and management in Erbil City. Environmental Protection Research, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- BS EN 12390-3. (n.d.). Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Concrete Specimens.

- Candido, R. G. (2021). Recycling of textiles and its economic aspects. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 599–624).

- Carpinteri, A. and Brighenti, R. (2009) 'Fracture behaviour of plain and fiber-reinforced concrete with different water content under mixed mode loading,' Materials & Design (1980-2015), 31(4), pp. 2032–2042. [CrossRef]

- cemconres.2017.01.004. Varghese, A. et al. (2019) 'Influence of fibers on bond strength of concrete exposed to elevated temperature,' Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology, 33(14), pp. 1521–1543. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, P., & Pan, S. (2017). Iron and steel slags. In Springer eBooks (pp. 233–252).

- Fanijo, E. O., Kolawole, J. T., Babafemi, A. J., & Liu, J. (2023). A comprehensive review on the use of recycled concrete aggregate for pavement construction: Properties, performance, and sustainability. Cleaner Materials, 9, 100199. [CrossRef]

- Felekoğlu, B., Tosun, K. and Baradan, B. (2009) 'Effects of fibre type and matrix structure on the mechanical performance of self-compacting micro-concrete composites,' Cement and Concrete Research, 39(11), pp. 1023–1032. [CrossRef]

- Fnais, A., Rezgui, Y., Petri, I., Beach, T., Yeung, J., Ghoroghi, A., & Kubicki, S. (2022). The application of life cycle assessment in buildings: challenges, and directions for future research. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 27(5), 627–654. [CrossRef]

- Gagg, C. R. (2014). Cement and concrete as an engineering material: An historic appraisal and case study analysis. Engineering Failure Analysis, 40, 114–140. [CrossRef]

- Grover, A. P., & Kumar, K. (2022). Sustainability of using recycled steel fibers in concrete. Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research). [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H. Z., & Saeed, N. M. (2024). Fiber reinforced concrete: a state of the art. Discover Materials, 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Herki, B.M.A. Absorption Characteristics of Lightweight Concrete Containing Densified Polystyrene. Civ. Eng. J. 2017, 3, 594–609. [CrossRef]

- Herki, B.M.A. Combined Effects of Densified Polystyrene and Unprocessed Fly Ash on Concrete Engineering Properties. Buildings 2017, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herki, B.M.A. Strength and Absorption Study on Eco-Efficient Concrete Using Recycled Powders as Mineral Admixtures under Various Curing Conditions. Recycling 2024, 9, 99. [CrossRef]

- Herki, B.M.A.; Khatib, J.M.; Hamadamin, M.N.; Kareem, F.A. Sustainable Concrete in the Construction Industry of Kurdistan-Iraq through Self-Curing. Buildings 2022, 12, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaertdinova, A., Maliashova, A., & Gadelshina, S. (2021). Economic development of the construction industry as a basis for sustainable development of the country. E3S Web of Conferences, 274, 10021. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A. and Khan, Q.U.Z. (2025) 'Optimizing hybrid fiber concrete: An experimental analysis of steel and polypropylene fiber composites using RSM,' Materials Research Express. [CrossRef]

- Khan, R. (2019) 'Fiber bridging in composite laminates: A literature review,' Composite Structures, 229, p. 111418. [CrossRef]

- Kryeziu, D., Selmani, F., Mujaj, A., & Kondi, I. (2023). Recycled concrete aggregates: a promising and sustainable option for the construction industry. Journal of Human Earth and Future, 4(2), 166–180. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P., & Shukla, S. (2023). Utilization of steel slag waste as construction material: A review. Materials Today Proceedings, 78, 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Labaran, Y. H., Mathur, V. S., & Farouq, M. M. (2021). The carbon footprint of construction industry: A review of direct and indirect emission. Journal of Sustainable Construction Materials and Technologies, 6(3), 101–115. [CrossRef]

- Labib, W. A. (2018). Fibre reinforced cement composites. In InTech eBooks. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.75102 Langer, W. H., & Arbogast, B. F. (2002). Environmental Impacts Of Mining Natural Aggregate. Springer eBooks, 151–169.

- Liu, J. et al. (2016) 'Combined effect of coarse aggregate and fiber on tensile behavior of ultra-high-performance concrete,' Construction and Building Materials, 121, pp. 310–318. [CrossRef]

- Mekonen, T.B. et al. (2024) 'Influence of steel slag as a partial replacement of aggregate on performance of reinforced concrete beam,' International Journal of Concrete Structures and Materials, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, O. and Zuaiter, H. (2024) 'Fresh Properties, Strength, and durability of Fiber-Reinforced geopolymer and Conventional Concrete: a review,' Polymers, 16(1), p. 141. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, O. et al. (2023) 'Water absorption characteristics and rate of strength development of mortar with slag-based alkali-activated binder and 25% fly ash replacement,' Materials Today Proceedings [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Papachristoforou, M., Anastasiou, E., & Papayianni, I. (2020). Durability of steel fiber reinforced concrete with coarse steel slag aggregates including performance at elevated temperatures. Construction and Building Materials, 262, 120569. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-S. (2008) 'Effect of fiber reinforcement and distribution on unconfined compressive strength of fiber-reinforced cemented sand,' Geotextiles and Geomembranes, 27(2), pp. 162–166. [CrossRef]

- Paul, S., Van Zijl, G., & Šavija, B. (2020). Effect of fibers on durability of Concrete: A Practical review. Materials, 13(20), 4562. [CrossRef]

- Plagué, T., Desmettre, C. and Charron, J. -p. (2017) 'Influence of fiber type and fiber orientation on cracking and permeability of reinforced concrete under tensile loading,' Cement and Concrete Research, 94, pp. 59–70. [CrossRef]

- Plizzari, G., & Mindess, S. (2019). Fiber-reinforced concrete. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 257–287).

- Rane, N., Choudhary, S., & Rane, J. (2024). Enhancing Sustainable Construction Materials Through the Integration of Generative Artificial Intelligence, such as ChatGPT or Bard. SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Shi, C. (2005). Steel slag — its production, processing, characteristics, and cementitious properties. ChemInform, 36(22). [CrossRef]

- Song, Q., Guo, M., Wang, L., & Ling, T. (2021). Use of steel slag as sustainable construction materials: A review of accelerated carbonation treatment. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 173, 105740. [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, J., Jude, A.B. and Thivya, J. (2017) 'Effect of copper slag, iron slag and recycled concrete aggregate on the mechanical properties of concrete,' Resources Policy, 53, pp. 219–225. [CrossRef]

- Yoshinaka, F. et al. (2016) 'Non-destructive observation of internal fatigue crack growth in Ti–6Al–4V by using synchrotron radiation μCT imaging,' International Journal of Fatigue, 93, pp. 397–405. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).