2. Creating a Hole in the Minkowski Manifold

The Schwarzschild metric is the simplest non-trivial solution to Einstein’s field equations. It is the metric that describes every spherically symmetric vacuum spacetime. The the external form of the metric can be expressed as:

Equation

1 is the external metric (where

with

t being the timelike coordinate and

r being the spacelike coordinate. The Schwarzschild radius of the metric is given by

in units with

and is commonly known as the Event Horizon. The external metric is the metric for an eternally spherically-symmetric vacuum centered in space.

But this metric comes from assuming a stress-energy tensor that is zero everywhere, meaning there is no mass anywhere in the manifold, even at the center. Therefore, this metric is describing a spherically symmetric Minkowski-like manifold (not in the sense that the manifold is flat, but in the sense that there is no matter or energy present anywhere in the metric). The question then becomes: how can the Minkowski manifold, which is massless everywhere, be deformed to give us the Schwarzschild metric?

Let us imagine Minkowski space-time which is flat everywhere in space and time. We choose a point in space (at all times) on the manifold and label it as the spatial origin . Thus we use spherical coordinates to describe the metric with r as the spacelike coordinate. For future clarity, we will label the Minkowski time coordinate , representing the proper time of observers at rest in their own frame.

Now we make a hole in the manifold by stretching the space-time at the point into a 4-sphere (because the hole is in space as well as in time at that location in space). In doing so, we have done two things:

We have given the manifold an intrinsically spherical shape with an intrinsic center

We have created a null space-time in the region inside the 4-sphere where space and time itself are absent (this would be the definition of creating a hole in the manifold)

So we assert that the Schwarzschild metric, which is the only spherically-symmetric solution to Einstein’s field equations describes 3 distinct, separate manifolds. When , we get the manifold described above where there is a hole in the Minkowski manifold. The spacetime is not flat anywhere in this metric. We cannot actually set r to infinity in this metric, as this is mathematically dubious. The best we can do is say that the spacetime approaches the Minkowski space-time as approaches zero. The Minkowski metric is only achieved when . Since , we might think that this means that the Minkowski metric is just the Schwarzschild metric when there is no mass present on the manifold. But this is false. As mentioned previously, the Schwarzschild metric comes from solving the field equations with a zero stress-energy tensor (and assuming spherical symmetry). So the Schwarzschild metric with non-zero already assumes no mass or energy anywhere on the manifold. Therefore, by setting , we are really saying is that there is no hole in the Minkowski manifold.

The internal metric, where

, is yet another distinct manifold. Note that we used

u instead of

because for the internal case,

u is a timelike radius, not a spacelike radius, and the definition

does not apply to this internal manifold. The internal manifold will be discussed further in

Section 3 and a much deeper analysis of the internal metric is the topic of a future work.

Returning our attention to the external metric with non-zero , we will now examine how the stretching of a point into a 4-sphere to create the hole in the manifold affects the Minkowski coordinates. Since the manifold is continuous, it is helpful to make an analogy here to true strain in a perfectly elastic material in continuum mechanics. Since we are stretching the center of the manifold from a point into a 4-sphere (as opposed to just ’cutting a hole out of the manifold’) with a finite radius, both the space and time will be strained by the stretch such that their strain is zero infinitely far from the hole.

We can characterize this strain as follows. We start with Minkowski space-time with a point designated

and a second point

r some distance away from that point such that the distance

r is greater than the radius of the hole being created. We now stretch the point at

into a hole with radius

. The true strain is defined as:

Where

is the final length and

is the initial length and the ratio:

is known as the "stretch factor". In this case, the initial length is the distance from

r to 0,

. The final length after the stretch is

. Substituting into equation

4 we get:

The strain goes to 0 as and goes to negative infinity (infinite compressive strain) when . The strain analogy is also useful when considering the speed of light in the Manifold as will be demonstrated below.

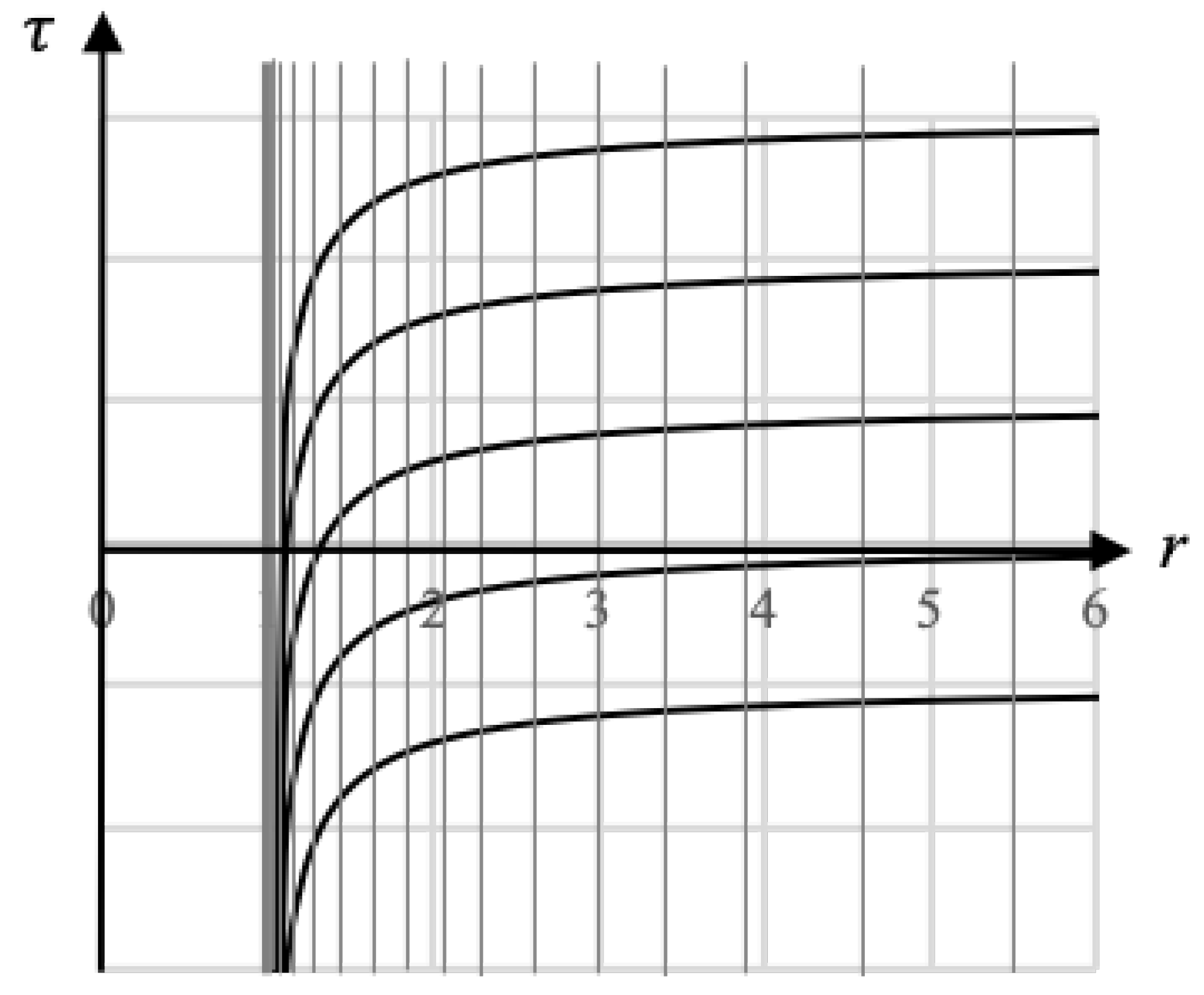

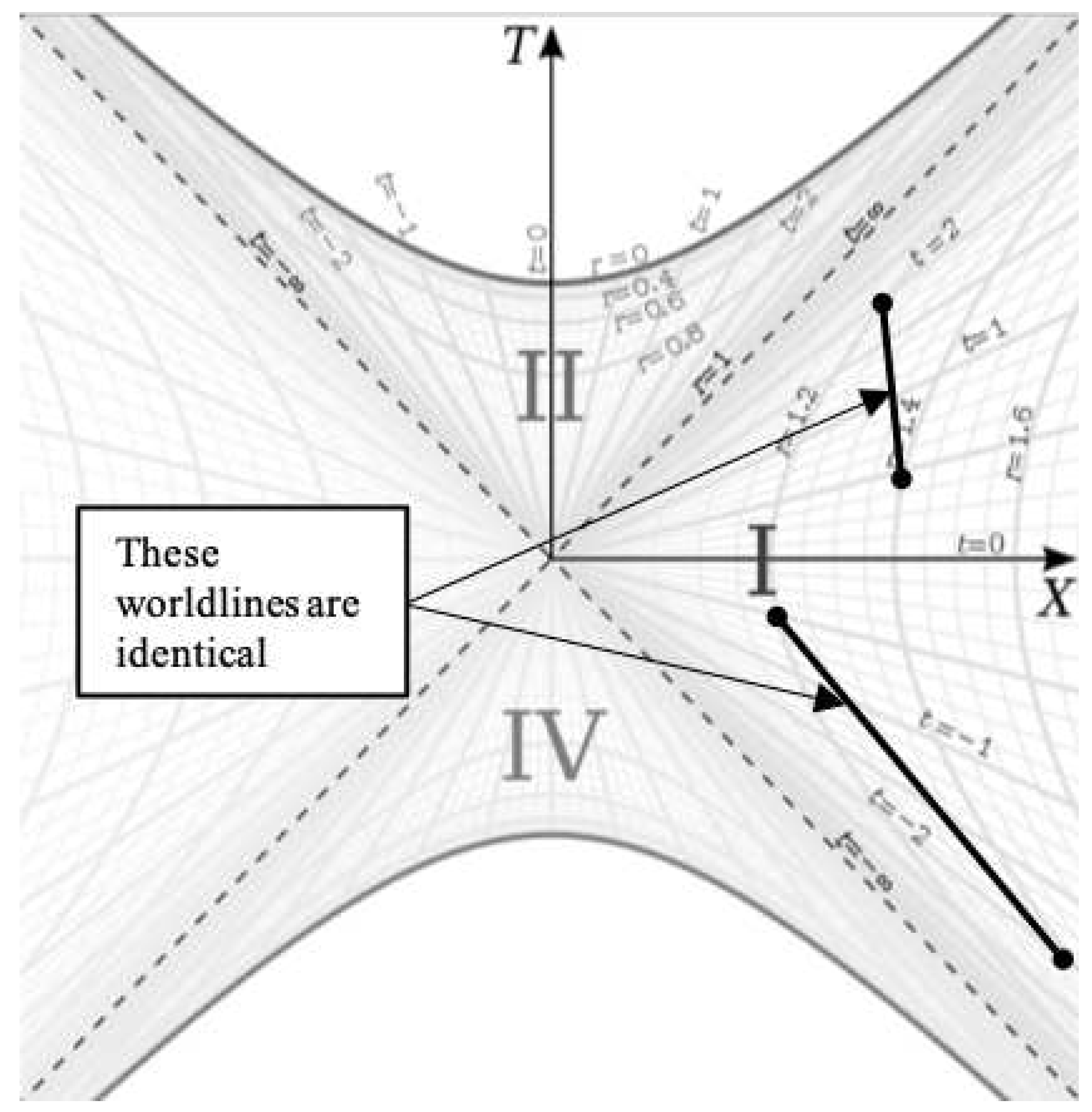

We can visualize the effect of the hole on the coordinates by looking at a space-time diagram in one spatial direction (the space-like axis represents a single ray emanating from the center of the manifold).

Figure 1 shows the coordinates after the hole has been introduced into the manifold overlaid on top of the original Minkowski manifold. The curved lines represent the time coordinate

t on the deformed manifold, and the non-uniformly spaced vertical lines represent the space coordinate (which we will call

s to distinguish them from the

r Minkowski coordinate) on the strained manifold.

Let us focus on the coordinate singularity coming from

of the Schwarzschild metric in equation

1. We can see why

goes to infinity in the metric when looking at

Figure 1. In the figure, the spacing between the

s coordinates lines relative to the

r coordinate lines goes to zero at

as a result of the strain from the hole. We can formalize this with the coordinate transformation:

Substituting this into equation

1, the metric becomes (ignoring the angular term):

Therefore,

of the

r coordinate, representing the magnitude of the

vector goes to infinity at

because the magnitude of the

vector, representing the proper distance basis vector goes to zero at

. In other words, for regions close to

, a small change in

r leads to a large change in

s because the

s coordinate is so closely spaced relative to the

r coordinate there. So by changing the spacelike coordinate from

r to

s, we have removed the coordinate singularity in the metric. We also note that the speed of light in this metric is given by:

Returning to the strain analogy from equations

3 and

4, note that the manifold density

at

r will be inversely proportional to the stretch factor

at

r. More formally, we can say:

Where

is the stretch factor infinitely far from the hole and

is the density infinitely far from the hole. We can define

, meaning we define the density of the Minkowski manifold as 1, which gives us the relationship:

Combining equations

9 and

7 we obtain the relationship between the speed of light and the manifold density:

Which is the same way in which the speed of sound is related to the density of an elastic material with a Young’s modulus of

. This also tells us that

where

and

are the vacuum permeability and permittivity.

Now let us shift our focus to the time coordinate. Since the hole is a 4D sphere, meaning that the time coordinate is also affected by the hole as depicted in

Figure 1, the time dimension will also be infinitely strained at the horizon, which is what is depicted in

Figure 1. This is captured by the relationship:

The spacing of the

s coordinate is simple to understand because the coordinates are vertical and parallel. But the deformed time coordinate is more interesting due to the curvature of the coordinate lines. Let’s take one of these

t coordinate lines and show the orientation of the

s and

t basis vectors at different distances from the edge of the hole in the frame of an inertial observer falling from infinity.

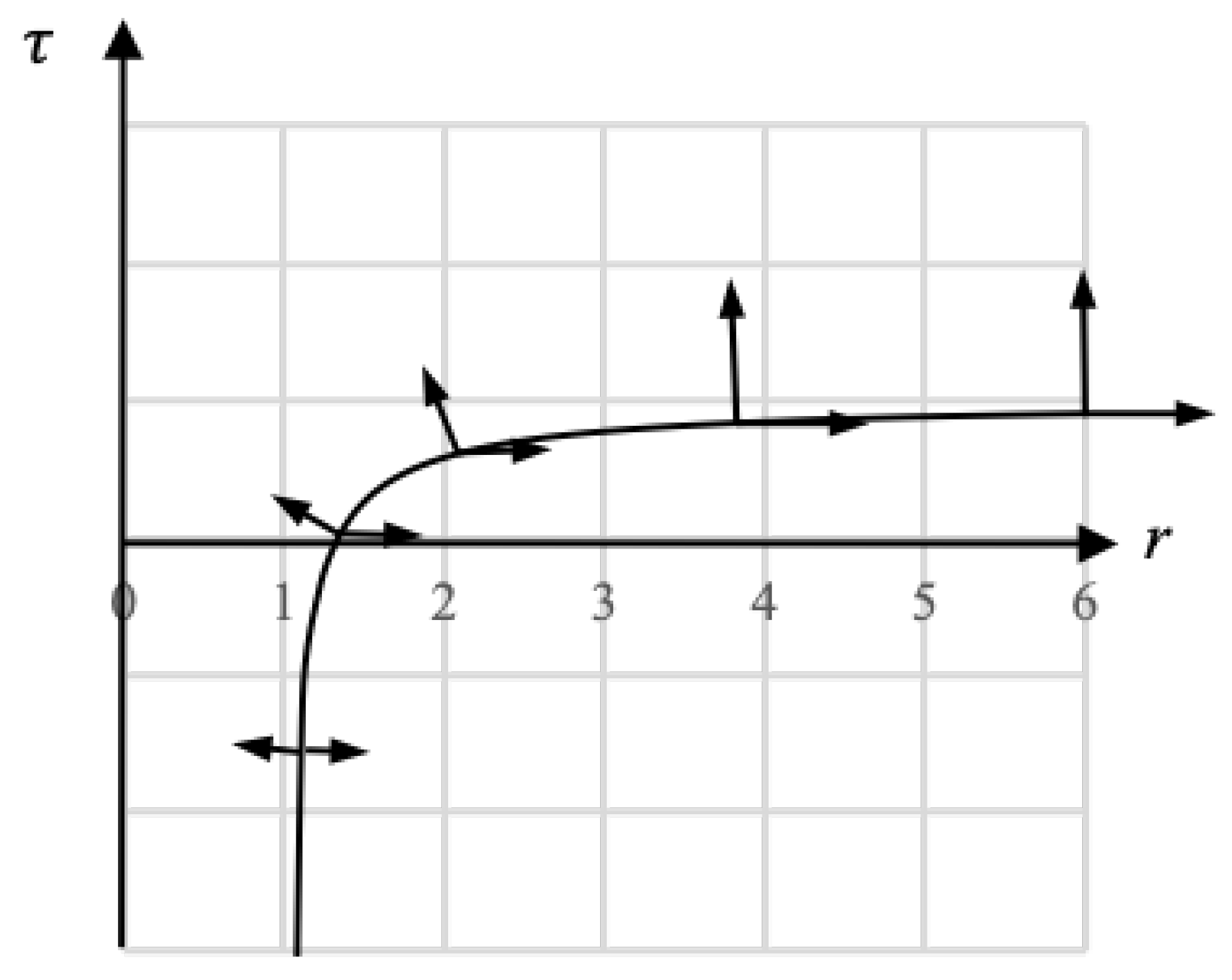

Figure 2 depicts this situation. The

s basis vectors are horizontal and the

t basis vectors are normal to the tangent of the

t coordinate line. The decreasing lengths of the vectors reflects the decrease in the distance between coordinate lines of each basis as

is approached.

In

Figure 2, we see that

goes to infinity at

because we measure

in the direction of the

t basis vector at

r. As

r approaches

, the

t basis vector rotates relative to the

basis, resulting in infinite density as the frame approaches

(see

Figure 1).

Figure 2 illustrates why an inertial observer is accelerated in the deformed manifold. In Minkowski spacetime, an inertial frame moves at the speed of light in their frame’s

direction. This is also the case in the Schwarzschild manifold. The difference is that with the Schwarzschild manifold, the inertial observer’s

vector is not perpendicular to the

vector. Therefore, the inertial frame still moves at the speed of light in the

direction, but this vector now has a component in the

direction. So the inertial frame’s motion (which in Minkowski space was motion only in time), has components in both the

and

directions. At infinity, all motion is in the

direction, but at any finite distance, the

vector will have components in both the

and

directions. As

r decreases during the fall, the magnitude of the

component decreases and the magnitude of the

component increases (giving the acceleration) until at

, all the motion is in the

direction, indicating that the inertial frame becomes null there (it moves through space at the speed of light).

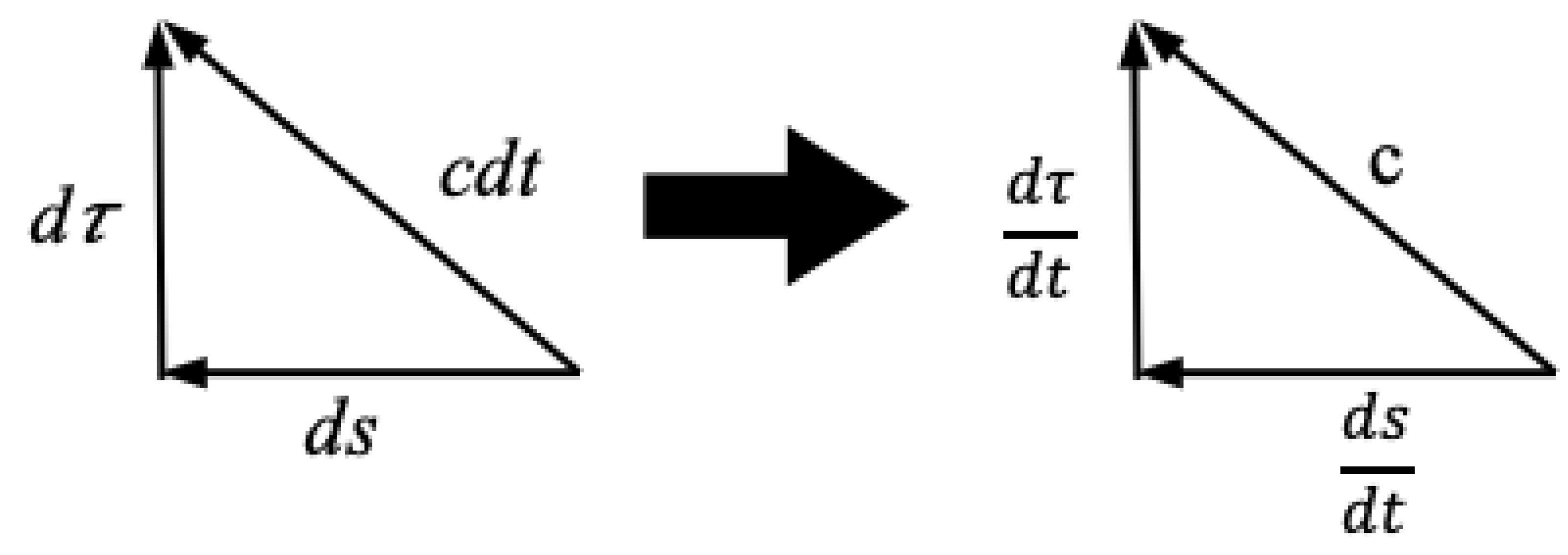

Figure 3 shows the tilted

vector multiplied by the local speed of light

c with its components in the

and

r directions from the Minkowski manifold. On the right side of the figure, we divide all sides of the triangle by

such that the length of the hypotenuse becomes just the speed of light at

r and the components become temporal and spatial velocities of the frame.

From this triangle, we get:

And given that

, we see that equation

12 is exactly the metric in equation

6, indicating that the way in which the

t and

s coordinates have been modelled in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 is accurate.

So we have seen how the falling observer is modelled in these coordinates, but how can we understand the proper acceleration of the rest frame in this manifold? In Minkowski spacetime, a frame feels acceleration when there is a gradient in their spatial velocity over time. The magnitude of this acceleration at a given time is given by the gradient of the spatial velocity over time at that time. The rest frame in the Schwarzschild manifold can be thought of in a similar manner except the proper acceleration is a function of the gradient of the rest frame’s temporal velocity gradient over space. The magnitude of the rest frame’s proper acceleration at a given location is given by the gradient of the temporal velocity over space at that location. The temporal velocity of the rest observer at

r is

the proper acceleration of the rest observer is:

Which is the expression for the proper acceleration of an observer at rest at

r [

3].

Furthermore, if we imagine a region of spacetime where the rest frame’s was constant over r (this could also be a stationary point on the curved t coordinate), then an observer at rest at r would have her time dilated relative to the rest observer in Minkowski space-time, but the observer would be inertial (i.e. the observer would not need to accelerate to stay at rest) since the gradient of the time dilation in that case would be zero. An observer in free fall in this scenario would accelerate up to the region where the gradient is zero and then continue falling at a constant speed relative to rest observers while in that region of the space-time.

Finally, reference [

4] tells us that

for an observer falling from rest at

is given by:

Combining equations

14 and

5, we get the needed derivative:

These are the velocity of an observer falling from rest at

in

r and

s coordinates. We can see from this that in

s and

t coordinates, which yield a metric without a coordinate singularity, the falling observer comes to rest at

. Equation

7 also indicates that light also comes to rest there.

Thus, we have shown that the geodesics of inertial observers become null at the edge of the hole and that there is no space-time inside the hole. Furthermore, the inertial geodesic remains at

due to the fact that the length of the

s and

t basis vectors go to zero at

per

Figure 2. We can also see that the geodesic remains at the horizon by looking at equation

15. We use equation

15 instead of equation

14 because the

and

densities are the same at any given

r. This velocity goes to zero when

, proving that the geodesic remains at rest there.

Note that the magnitude of this velocity increases to a maximum at some

(maximizing at

in the case of an observer falling from infinity) and then decreases to zero at

. We can see why this is the case by re-expressing equation

15 as:

The

part comes from the orientation of the

vector relative to the

vector (quantified by the second square root in equation

15). This quantity increases during the whole fall until it reaches 1 at

. The first square root in equation

15 represents

c, which decreases during the fall. The magnitude of

c changes the length of the

vector per

Figure 3. Therefore, the magnitude of

for the falling observer is increased during the fall due to the change in orientation of the

vector, and is reduced due to the change in the length of the vector. When the effect of the change in the orientation of the vector on the

component is greater than the effect of the reduction in length of the vector,

will increase. But at some point, depending on where the fall started, these changes will balance each other, which is where the magnitude of

is maximized, after which the effect from the reduction in length of the

vector becomes dominant, decreasing the magnitude of

to zero at

.

Creating the Schwarzschild manifold by making a hole in the Minkowski manifold makes the fact that geodesics come to rest at

intuitive since there is by definition no space-time inside the hole of the manifold, so there is nowhere else in space for the geodesics to go, they must remain at rest there. In fact, if one begins by postulating that creating a hole in the Minkowski manifold is equivalent to introducing a stretch factor

over the manifold and that the speed of light over the manifold is equal to

(which amounts to postulating equation

10), then one can derive the Schwarzschild geometry using the presented analysis without needing to solve the field equations.

It has been proven that the free-falling geodesics in the Schwarzschild manifold in singularity-free coordinates become null at and that null geodesics remain at , meaning that is the endpoint of gravitational collapse. If this is true in one set of coordinates, it must be true in all coordinates. We will examine these geodesics in two other coordinate systems in this paper, the Kruskal-Szekeres and Eddington-Finkelstein coordinates. It will be shown that while a cursory look at the metric in these coordinate seems to indicate that the horizon is traversable, when we carefully examine free-falling geodesics in these coordinates, we get the same results as found above, which should be expected.

4. The Falling Frame of the External Metric in Kruskal-Szekeres Coordinates

The Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates are the maximally extended coordinates for the Schwarzschild metric. The coordinate definitions and metric in Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates are given below (derivation of the coordinate definitions and metric can be found in reference [

5] where

and

).

With the full metric in Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates given by:

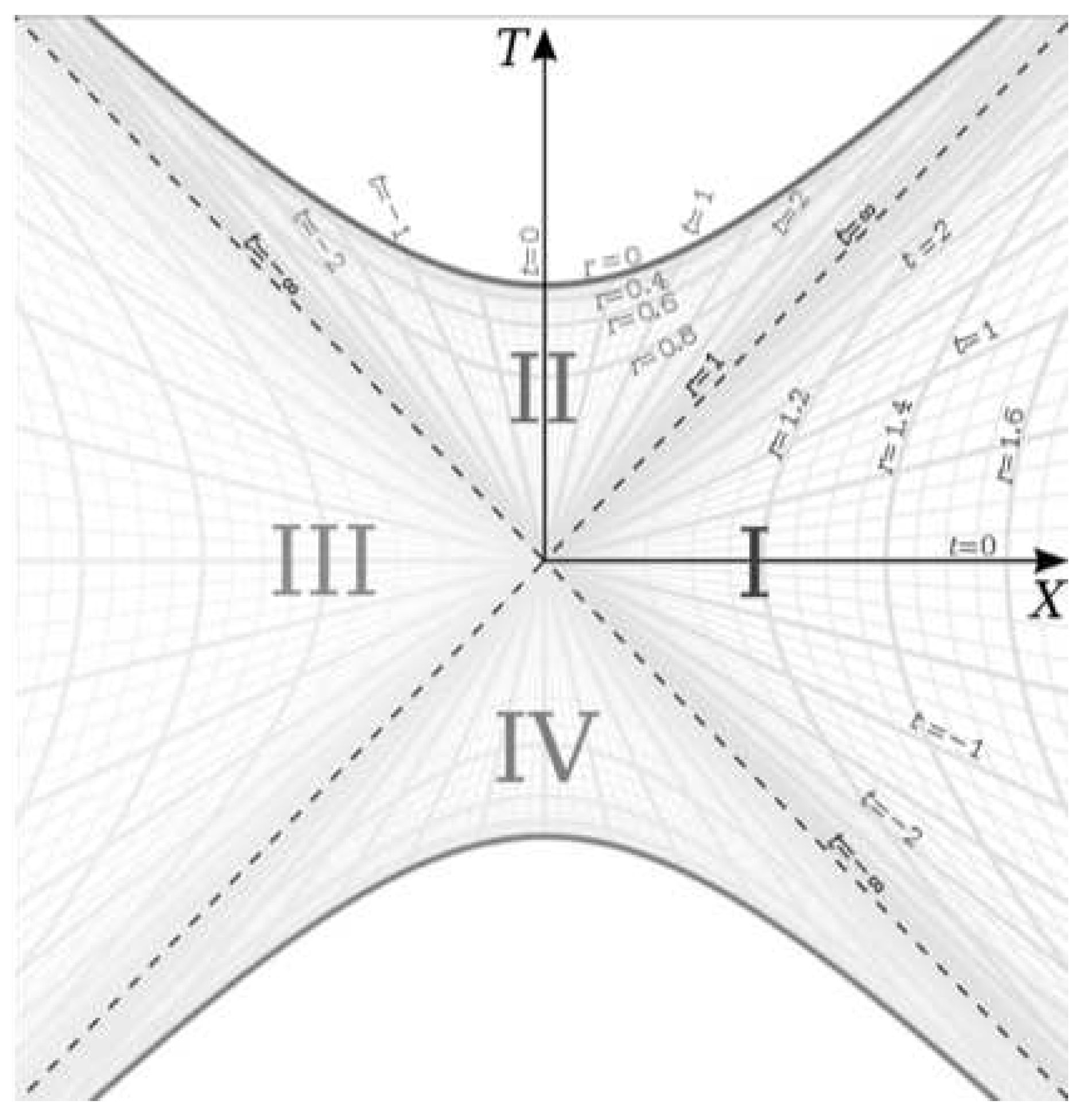

Finally, we plot the metric on the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinate chart [

6] in

Figure 4:

In this paper, we will be focusing on region I in this chart, which is the spherically symmetric spacetime around a spherically symmetric source in space.

We can see in

Figure 4 that for a rest frame (

), that

depends on the value of

t we evaluate the derivative at since the derivative for the rest frame is the tangent to the hyperbola at

t. Since the metric is time-symmetric, we know that the actual physics does not depend on the value of

t and therefore, we need a deeper understanding of the meaning of the changing

in the rest frame and how it relates to the falling frame at the same point.

The time symmetry of the metric tells us that we can hyperbolically rotate the spacetime (rotate the

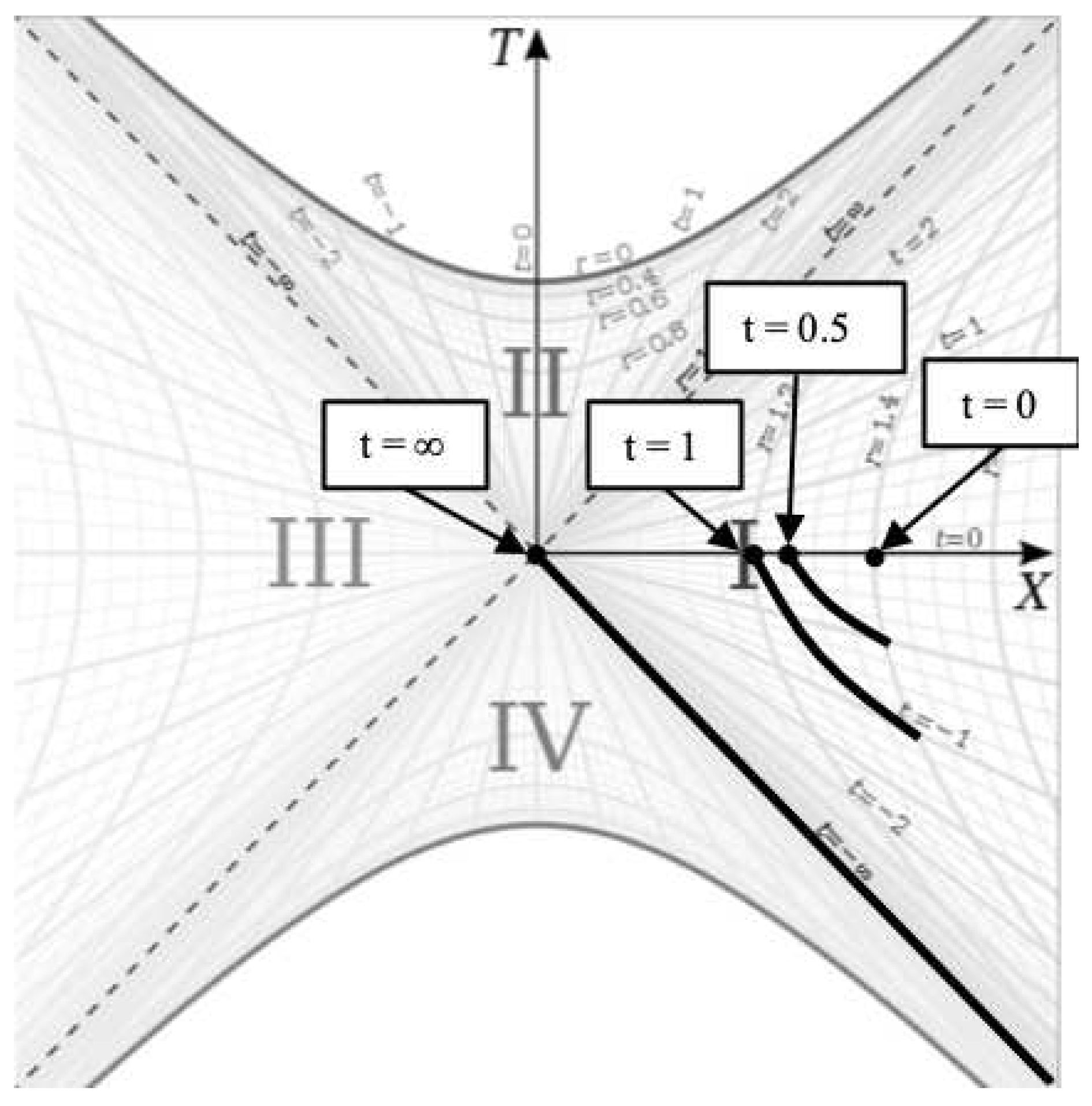

t coordinates in the coordinate chart) without changing the physics. For example,

Figure 5 shows two identical worldlines hyperbolically rotated relative to each other on the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinate chart.

These worldlines are the same because and are the same for both worldlines, such that their proper lengths are the same. So the time translation symmetry of the metric translates to hyperbolic rotational symmetry on the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinate chart.

We can use this fact to change how we visualize the worldline of an observer falling toward the horizon. Rather than drawing the line from

at some

r to

at the horizon, we can continuously hyperbolically rotate the space as the observer falls such that the ’present’ state of the falling frame is always at

. An example of this is given in

Figure 6.

In

Figure 6, the observer begins falling at

. This is represented by the rightmost point on the

X axis in the diagram. After

, the observer has fallen to a lower radius represented by the point to the left of the rightmost point. So rather than having the worldline grow up from

as time passes, we hyperbolically rotated the worldline points down as time passes to keep the present point of the worldline on the

X axis. This is a valid way of visualizing the worldline as a result of the time symmetry of the metric.

When using this construction, we see that the falling worldline reaches the point on the diagram. And if the worldline does indeed become null at the horizon, this means the worldline remains on the line since that is the null geodesic representing the horizon.

It is notable that since the lines are null geodesics at the same point in space (), this means that all falling frames reach the horizon simultaneously regardless of where or when they begin falling relative to each other. This fact is more evident when drawing the worldlines the traditional way where they reach the horizon at . If two frames start falling from different radii at , they will intersect the the horizon at at different points along the line in the coordinate chart. But the proper distance between those points is zero and they are both at the same point in space, therefore the two points are in fact coincident.

There appears to be a conflict between the construction in

Figure 6 and the traditional construction which has the worldline reach the horizon at

along the

line where

T and

X are greater than zero. This conflict is significant because the construction presented here shows a worldline that becomes null at the horizon whereas the traditional construction has a non-null worldline at the horizon. It is impossible for both to be true and therefore the discrepancy must be resolved. To resolve this conflict, we need a more detailed examination of the falling frame’s worldline in Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates.

Let us first take the differentials of

T and

X in equations

17:

Calculating the partial derivatives, rearranging and defining

we get:

Next, we need to calculate

from equations

20 by factoring out

from each equation and dividing:

This equation is the same equation derived in [

2] but put in a slightly different form. Next, we make the following definitions:

This is the derivative of the rest frame at

t since plugging

into equation

21, we get

. Since we know the Schwarzschild metric is independent of

t, this derivative must be a non-physical artifact of the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates at fixed

r and is not related to any actual change in motion through space and time.

And we define the relative velocity of the frame in motion relative to the rest frame as:

This is the relative velocity in Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates between the frame in motion and the rest frame at

r. This derivative is 0 for the rest frame since

in that frame. If we combine equations

23 and

14 we get:

Which is well behaved and equal to -1 when

. Plugging these definitions into equation

21, we get:

We recognize that equation

25 is the relativistic velocity addition formula giving us the total velocity as the relativistic sum of the rest frame velocity and the relative velocity between the moving frame and the rest frame. We can solve for

to get an expression for the relative velocity between a frame in motion and the rest frame in Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates:

Assuming that

ranges from -1 to 1 and

, we see that the relative velocity approaches 1 or -1 for all

as the horizon is approached since the horizon is at

, such that

there. Equation

26 is also constant along a given hyperbola (i.e it is independent of

t) since it represents the relative velocity between the moving and rest frames.

Equation

26 is essentially a hyperbolic rotation of a given worldline point along a hyperbola of constant

r to

. The reason this gives us the relative velocity is that at

, the Schwarzschild basis vectors and Kruskal-Szekeres basis vectors are aligned there, meaning that the

X and

T in

are pure spacelike and timelike basis vectors and thus the derivative gives a true velocity relative to the rest frame. This is in contrast to the general

which is a derivative without a clear spacetime meaning since the

X and

T coordinates are mixtures of space and time everywhere else.

It is also notable that equation

25 is undefined when

because since

there and

there, we get:

This is also what was demonstrated in [

2]. Therefore, under these conditions,

and

are undefined at the horizon when

T and

X are greater than 0. This suggests that there is a discontinuity in the worldline when reaching the horizon at

, even in Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates.

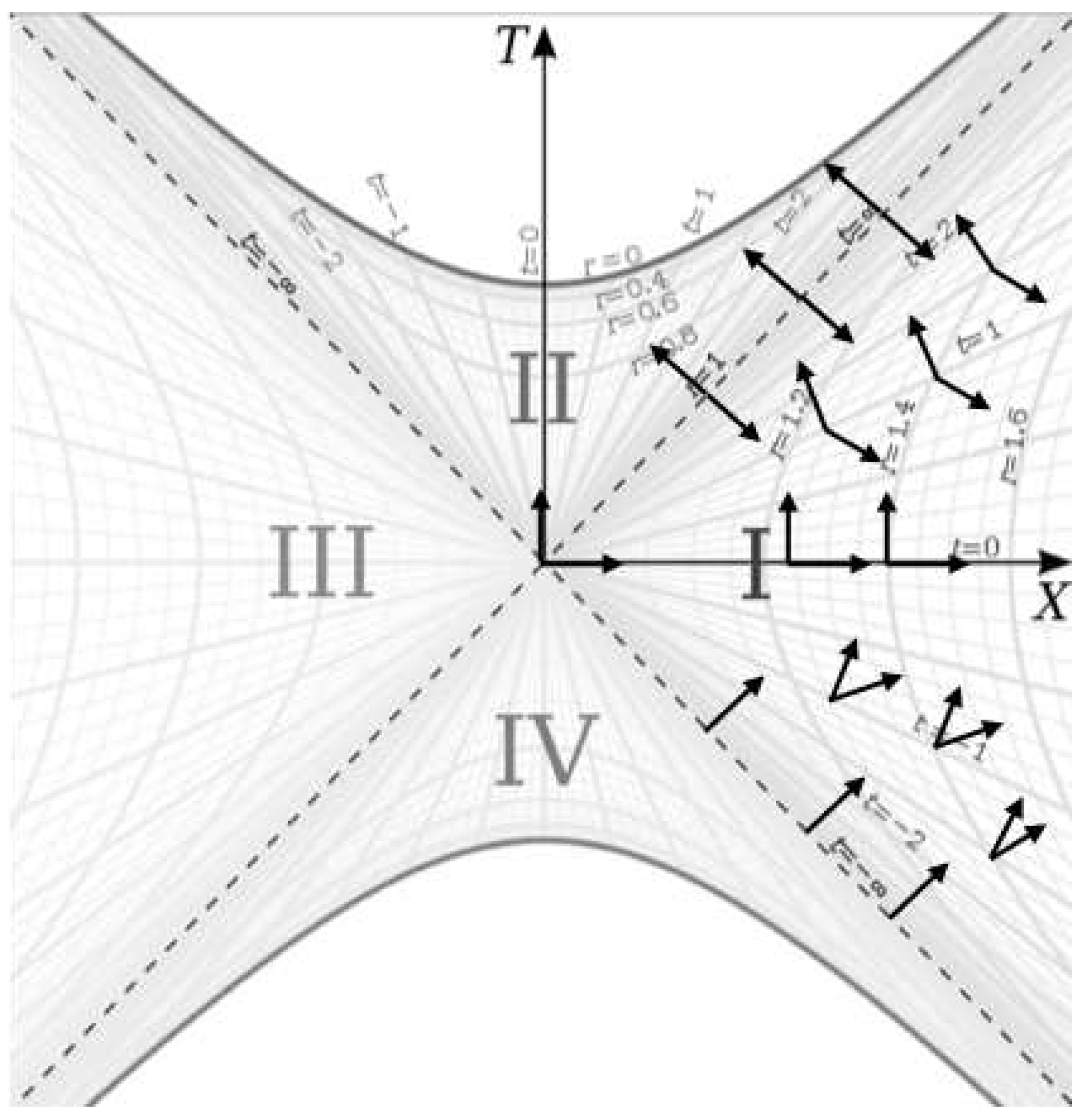

Figure 7 can help us see why equation

21 becomes undefined at the horizon by depicting the space and time axes of the rest frames at different points on the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinate chart.

Along the X axis, the space and time bases are orthogonal and aligned with the Kruskal-Szekeres basis vectors. As t moves away from 0 in either direction, the rest frames in which the derivative is measured become increasingly Lorentz boosted. These boosts are an artifact of the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates and not physical boosts. We know this because is a Killing vector. So if we move along a hyperbola of constant r, the space-time bases are boosted as t increases, but we know that the frame of the rest observer does not change over time due to the time symmetry of the manifold.

That the derivative is measured in increasingly boosted rest frames over time in Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates is not a problem anywhere except at . At those locations, the rest frame is infinitely Lorentz boosted such that the space-time bases are collinear because the rest frame is light-like at the horizon. In a light-like frame, the relative state of motion of other frames cannot be determined because in the light like frame, one cannot make measurements of space and time due to the collinearity of the bases.

Now let’s calculate the situation described in

Figure 6 where we calculate the worldline falling along the

X axis as the past worldline is hyperbolically rotated down. For this construction, we set

in the equations since the derivative is always taken on the

X axis. For this calculation, we put the metric in the following form (we will be examining radial infall so

):

Since we are keeping

, we can use the inverse of equation

24 for

in the equation. We can solve for

r in terms of

X by setting

for the

X equation in equation

17 and solving for

r:

Where

W is the Product Log function. Substituting equations

29 and

24 into equation

28 allows us to integrate the worldline along the

X axis:

Which goes to 0 as

X goes to 0. But we can now show that this is exactly equivalent to falling in Schwarzschild coordinates by first using equation

20 to solve for

when

:

Substituting equations

31 and the inverse of

23 into equation

28 gives:

And we can see that Equation

32 is in fact the Schwarzschild metric in Schwarzschild coordinates.

Therefore it has been proven that the worldline construction shown in

Figure 6 is equivalent to falling in Schwarzschild coordinates and it has been demonstrated that the worldline in that construction is light-like at the horizon. When we couple this finding with the fact that the Kruskal-Szekeres derivative is undefined at the horizon for any construction in which the worldline reaches the horizon at

, we can conclude that the event horizon is length contracted to a point in a falling frame approaching the horizon as a result of the fact that the worldline becomes null there.

Furthermore, we see from equation

31 that

is zero at

. Therefore, the falling frame remains at the horizon along the

lines in the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinate chart when it reaches the horizon.