II. Comparison of the Exterior and Interior Metrics

The Schwarzschild metric has the following form:

The exterior metric, which describes the spacetime around a spherically symmetric mass is given for values of

where

u is the Schwarzschild radius

related to the mass

M of the source given by

. This metric treats the mass of the source as being concentrated at point at the center of the spacetime.

The interior metric is known as a ’Kantowski-Sachs’ spacetime [

1] which has different linear and azimuthal scale factors. This is understood to mean that the spacetime is anisotropic.

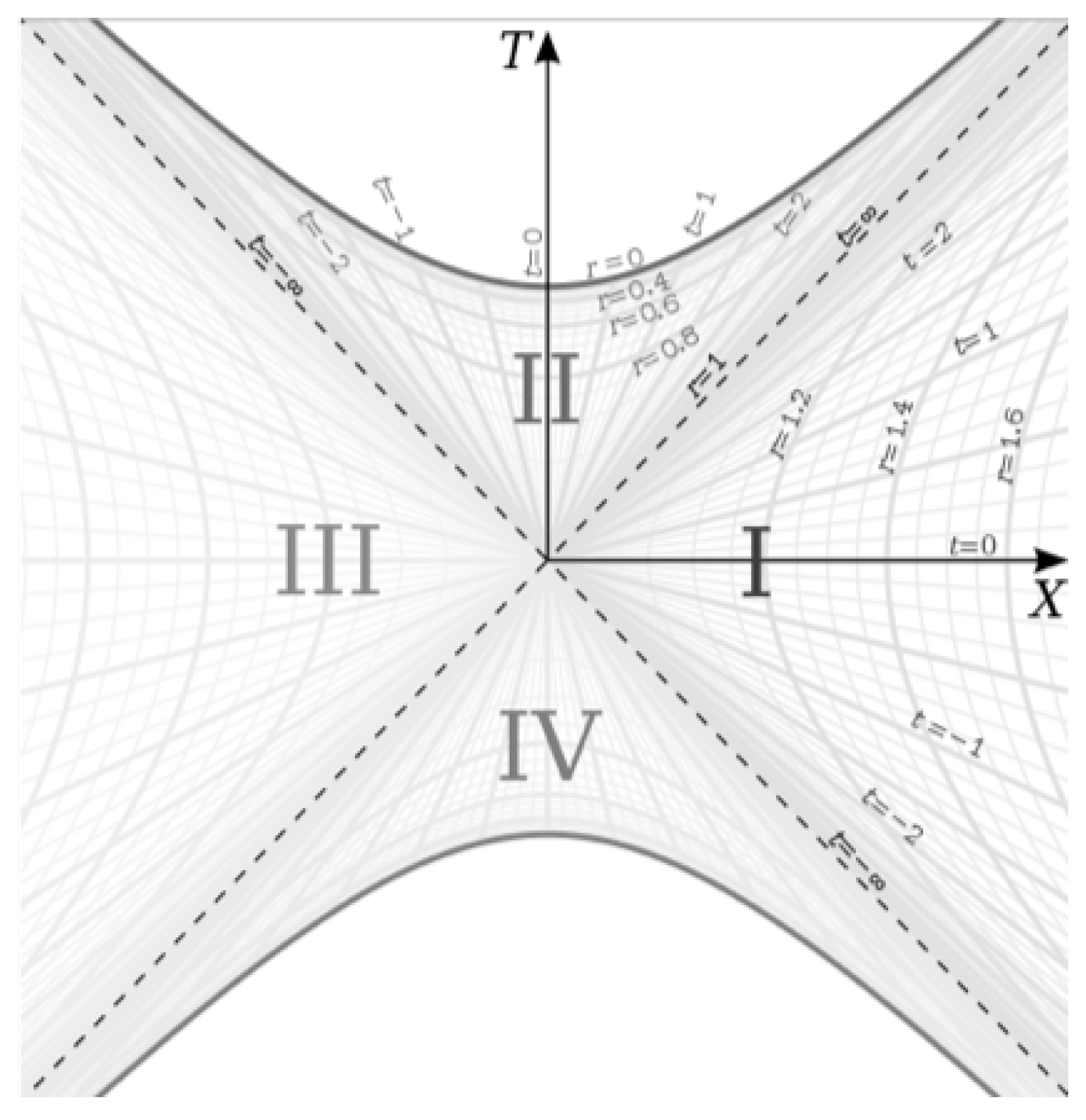

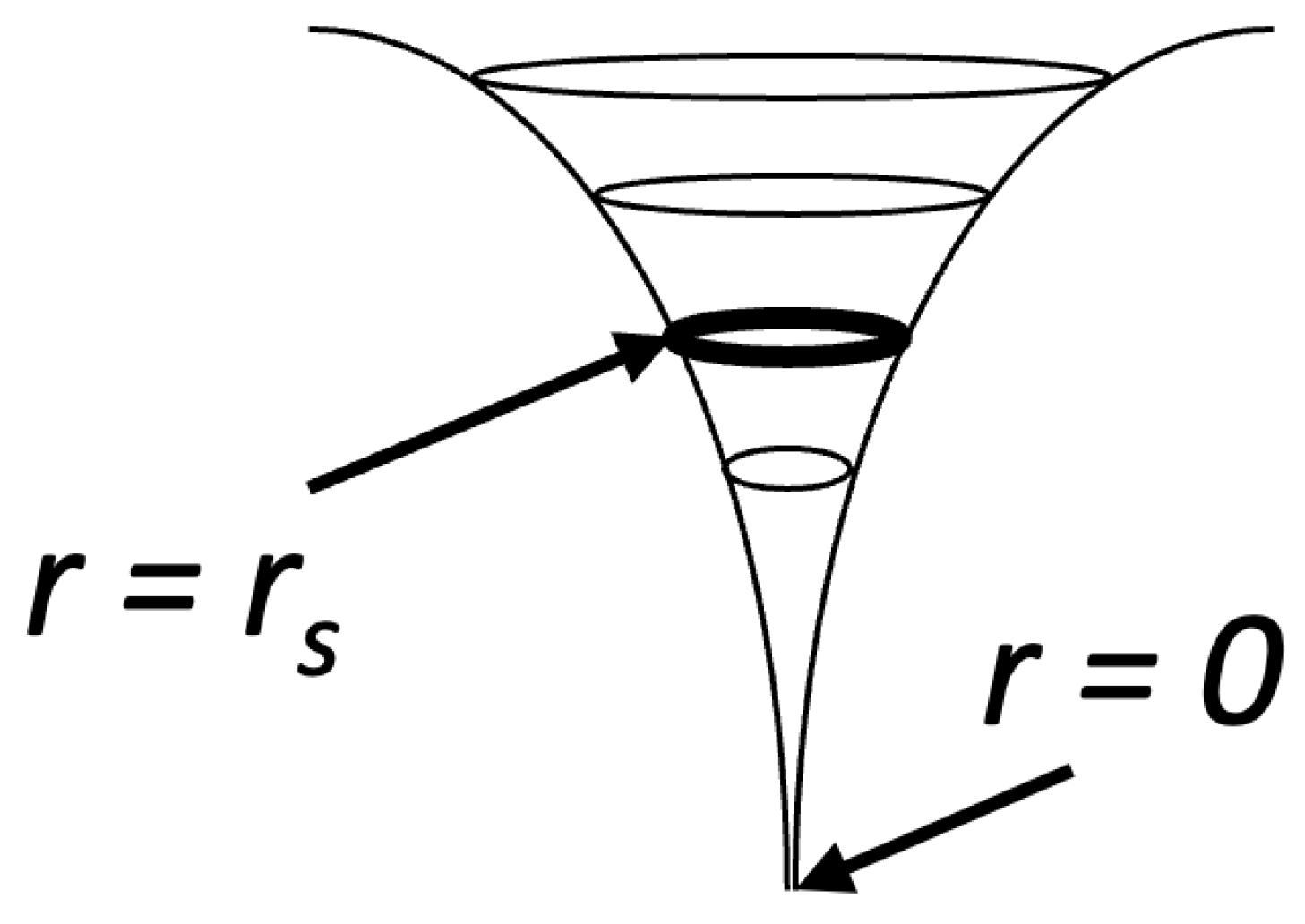

Figure 1 shows a common depiction of the gravitational well of the Schwarzschild metric (

,

).

We are given the impression here that the geometry inside and outside the event horizon are the same with the main difference being that once an observer crosses the event horizon (), they will continue to fall to the singularity at where they will be ’spaghettified’ as a result of the radius of the 2-sphere collapsing to a point and the t dimension becoming infinitely stretched.

However, we must be careful with the sign changes in the metric as the horizon is crossed. In the common interpretation, the azimuthal term is interpreted the same outside and inside the event horizon even though the radius goes from being spacelike to being timelike. In the exterior metric, is an arc length, but in the interior metric, it is a time (because r has units of time). And if we treat r as simply a scale factor, then it is scaling the angles themselves, not the arc length. Furthermore, if the radius is a time, then it is unclear what it would mean to revolve around a future point in time ().

So we need to examine the exterior and interior geometries more closely to understand how exactly they are different, particularly in regards to the meaning of the azimuthal term in each case. The Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates are very useful for this task. As we will see, the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinate chart allows us to see how the

t and

r coordinates are curved relative to Minkowski space. But first, we define the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates in terms of the Schwarzschild coordinates. For the exterior metric:

And for the interior metric:

With these definitions, we can plot the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinate chart [

2]:

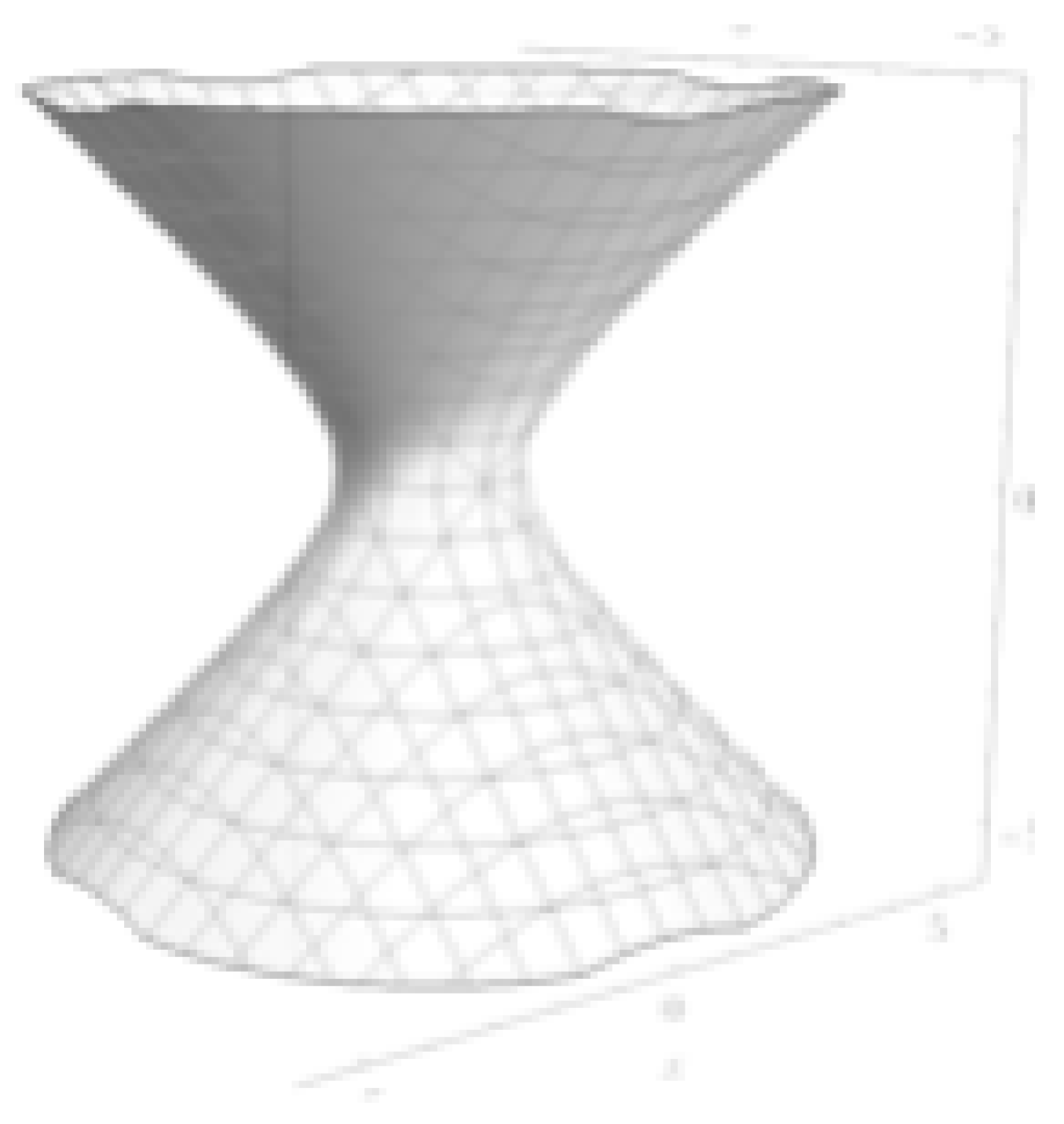

Figure 2.

Kruskal-Szekeres Coordinate Chart

Figure 2.

Kruskal-Szekeres Coordinate Chart

In this paper, we will focus on regions I and II of this chart, representing the exterior and interior metrics respectively. Since the Kruskal-Szekeres coordinates are defined in such a way that null geodesics are 45 degree lines everywhere on the chart and the T and X coordinates are straight and mutually perpendicular everywhere on the chart, we can think of the T-X grid as Minkowski space with the curved r and t coordinates overlaid on the grid. Thus, this chart clearly shows how the Schwarzschild space and time coordinates r and t are curved relative to the Minkowski coordinates T and X. We see that the r coordinate lines are hyperbolas, which captures that fact that an observer at rest in the exterior metric experiences a constant acceleration, and the t coordinate is a hyperbolic angle. That t is a hyperbolic angle will become an important fact when we look at the geometry of the interior metric.

We see from equations

2 and

3 that we need separate Kruskal-Szekeres coordinate definitions for the exterior and interior metrics, but we can combine these into a single relationship as follows

Equation

4 is applicable to both the interior and exterior solutions. For the exterior metric,

and for the interior solution,

.

The equation for a 2D hyperboloid surface embedded in three dimensions is given by:

For our purposes, we will be considering the special case where

, which gives the one and two sheeted hyperboloids of revolution. Equation

4 appears to be only for one dimension of space, but if we think of

X as a radius, then it can describe 3 sphrically symmetric dimensions of space.

So comparing to Equation

5, if we set

and

where

R is a radius of a circle in this example, we obtain an equation that matches the form of Equation

5 where :

Equation

6 describes 2D hyperboloid surfaces for a given

r where the interior metric has negative

and the exterior metric has positive

. Let us now visualize a surface of constant

r in both the exterior and interior metrics. For the exterior metric at some

, we get the following hyperbolid of revolution:

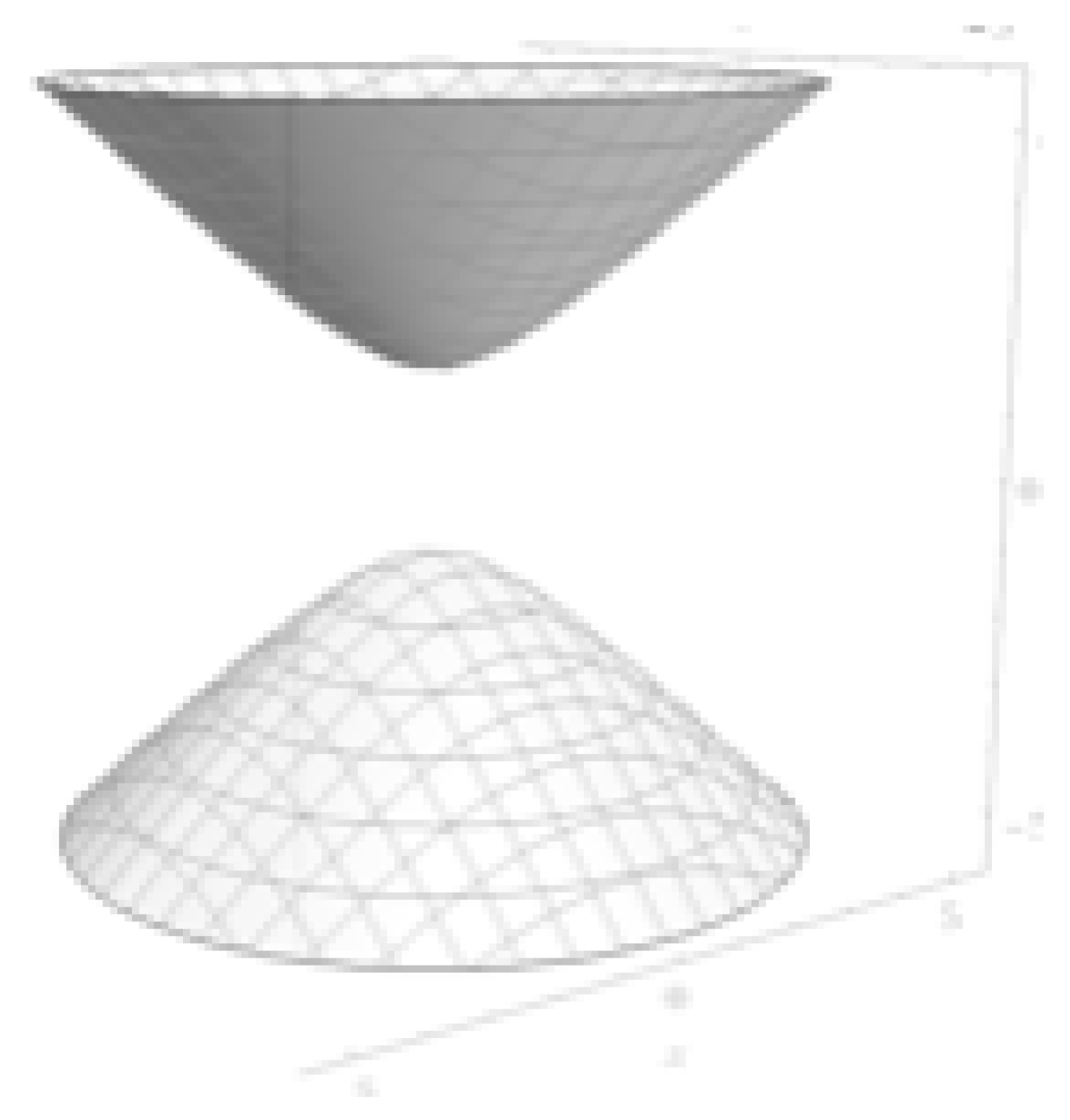

Figure 3.

Surface of Constant for the Exterior Metric in Kruskal-Szekeres Coordinates

Figure 3.

Surface of Constant for the Exterior Metric in Kruskal-Szekeres Coordinates

On this hyperboloid, the time coordinate t is marked as circles on the sheet and we have one free spatial coordinate on the surface which is the angle of revolution of the surface. The location is at the throat of the hyperboloid. The first thing to note here is that the t coordinate can only be hyperbolically rotated in one direction: up or down. This is because the t coordinate is the coordinate of time and time only has one dimension so there can only be a hyperbolic rotation along the single time dimension. The second thing to notice is that the radius of the sheet is pointed perpendicular to the axis of circular rotation. This is why when a reference frame at some undergoes some angular rotation , it moves along an arc length in space.

So we can see how if in

Figure 3,

r was timelike and

t was spacelike, as is the case in the interior metric, then the spacetime would be anisotropic because in that case, the entire surface is spacelike and the spacetime looks different in different directions. In one direction, the space is closed (moving around a circle on the hyperbolid as

r, which is the time coordinate in the internal metric, decreases), and in the perpendicular direction, the space is open (moving up or down on the hyperboloid).

So if a 2D foliation of the interior metric at some

r was represented by the one-sheeted hyperboloid of revolution (like the exterior metric is), then the common visualization of the gravitational well in

Figure 1 would be correct. However, we need to recall that for the interior metric, the right side of equation

4 is negative, which gives the following hyperboloid surface for some constant

:

Figure 4.

Surface of Constant for the Interior Metric in Kruskal-Szekeres Coordinates

Figure 4.

Surface of Constant for the Interior Metric in Kruskal-Szekeres Coordinates

The first thing we notice is that this is a two-sheeted hyperboloid as opposed to the one-sheeted hyperboloid of the exterior metric. So right away, we can see that the interior and exterior geometries are different. In this paper, we will focus on the top sheet, representing a hyperbola in region II of

Figure 2.

If we look at region II of

Figure 2 in the context of

Figure 4, we see that in contrast to the exterior metric where the radius perpendicular to the axis of circular rotation, in the interior metric, the radius is parallel to this axis. Recall that

r is now the time coordinate and time is one dimensional, so the radial vector in this case is stuck in one dimension. Furthermore, we see that the

t coordinate, which is a hyperbolic angle, can be rotated in 3 different dimensions now since the

t coordinate is spacelike (we see two of the three dimensions in

Figure 4). Since

t is a hyperbolic rotation and

is a Killing vector of the spacetime, we can hyperbolically rotate the space to move any point on the surface to

which is at the apex of the hyperboloid. So just like we can set any arbitrary time as

in the exterior metric, we can set any arbitrary location as

in the interior metric. In particular, for a given reference frame we are examining, we can say that that reference frame is always at

, and when the frame moves in a particular direction, that is modelled as the hyperboloid being hyperbolically rotated in that direction such that the reference frame remains at

as it moves.

Therefore, the t coordinate, which is a hyperbolic angle, is like a ’forward/backward’ coordinate. It represents the straight-line distance from the reference frame to some point. In the exterior metric, the hyperbolic rotation could only happen along one direction (the direction of time), but being spacelike in the interior metric, the hyperbolic rotation can now happen in any direction in three dimensions of space.

We can understand the nature of the t coordinate by imagining ourselves in the interior metric. The metric is an infinite dark vacuum so there are no reference points other than the frame itself, so the origin of space is always the reference frame itself, which is always . So the velocity is always the velocity of the reference frame tangent to its worldline, regardless of whether the motion is in a straight line or curved. This is in contrast to the exterior metric where the velocity tangent to the worldline comes from a combination of radial velocity and tangential velocity perpendicular to the radius .

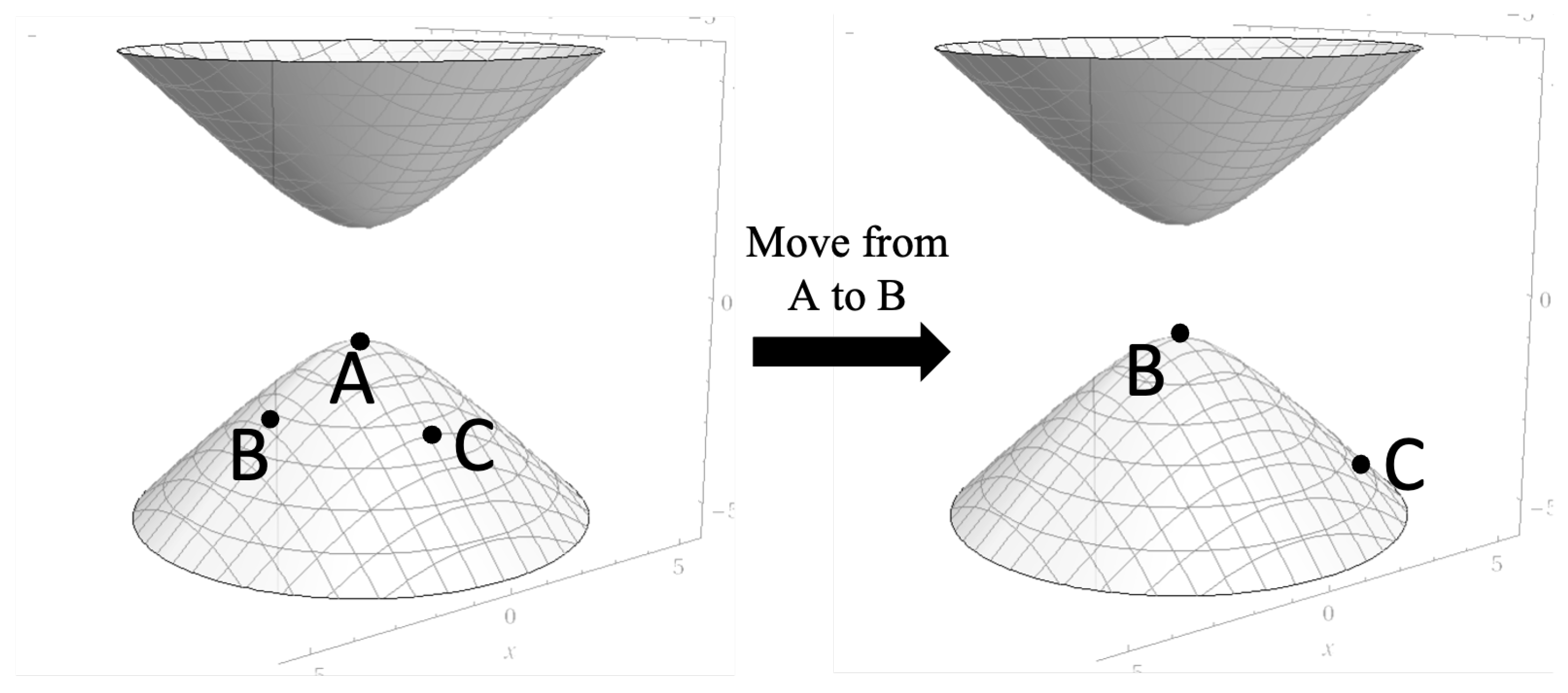

This brings us to the azimuthal term of the interior metric. Consider

Figure 5 which depicts an observer at point A moving to point B, stopping and then moving to point C (we are illustrating this on the lower hyperboloid, but the same applies to the upper hyperboloid.

Figure 5.

Moving Between Points in the Interior Metric

Figure 5.

Moving Between Points in the Interior Metric

On the left half of

Figure 5, we see the observer at point A. To go from A to B and then C, it looks like we would move along a hyperbola to get to B and then around the circle to get to C. But as is shown on the right side of

Figure 5, as we move from A to B, we hyperbolically rotate the space along the direction AB. This hyperbolically rotates point B to

, A to the far side of the hyperboloid opposite to where B was on the left (so it is not visible in the diagram), and C moves along the hyperbola it was on in the same direction. And what we see here is that now to get from B to C, we do another hyperbolic rotation but in the direction BC on the right side of the diagram. So in taking the path AB, stopping, then BC, we see that there were only translations in

t involved and nothing to do with the circular rotation

.

So what then is the azimuthal term of the interior metric measuring? Let’s repeat the same motion in

Figure 5 again, only this time we will move continuously from A to B to C without stopping. To do this, we would again apply a hyperbolic rotation from A to B and at the instant we reach B, we change the direction of the hyperbolic rotation to go from B to C. In this scenario, we are boosting the reference frame twice where the two boosts are not collinear. In Special Relativity, the application of non-collinear boosts like this causes the reference frame of the boosted observer to precess relative to the lab frame (in this case, the lab frame is the event horizon which for the interior metric is a shell surrounding the infinite space). If we consider continuous boosts, this effect is known as Thomas precession and is defined as [

3]:

Where is the Thomas precession. Note that this precession doesn’t refer to any spatial center, it is determined entirely by the motion of the reference frame without reference to anything/anywhere external. The Thomas precession is like a ’spin’ of the reference frame which is essentially the precession of gyroscope attached to the reference frame relative to the surrounding shell. So if we put an arrow on the 2-sheeted hyperboloid of the internal metric at fixed and pointed in some arbitrary direction in space (representing the gyroscope of the reference frame), a change in the angle of the metric corresponds to the hyperboloid rotating relative to that gyroscope.

We can now understand why in the interior metric, the radial vector is parallel to the axis of rotation as opposed to the exterior metric where the radial vector is perpendicular to the axis. In the interior metric, the azimuthal term is describing the rotation of space around the time dimension (r) of the reference frame and that rotation is known as the Thomas precession.

For the case of circular motion (

,

),

where

a is the centripetal acceleration and

, the tangential velocity. The centripetal acceleration can be expressed as

where

is the angular velocity of the frame around the point at the center of the circular rotation. So

and since

is by definition the tangential velocity of the frame,

. If we substitute all this into equation

7, we get the following relationship for circular motion:

So for the case of circular motion, equation

9 allows us to relate the Thomas precession

(i.e. the angular velocity in the interior metric) to the angular velocity

of the frame.

The geodesic equation for angular motion [

4] in the interior metric is given below (we will examine the case for planar rotation where

).

If we choose

to be

r in this analysis and assume an initial circular motion, we can integrate to get the angular velocity

of the geodesic:

Where

is the initial precession. So the Thomas precession increases as

r decreases (corresponding to time increasing) and becomes infinite at

, the singularity. Combining this with equation

9, we see that a frame in circular motion in the interior metric will have that circular motion accelerated over time as a result of the

geodesic equation.

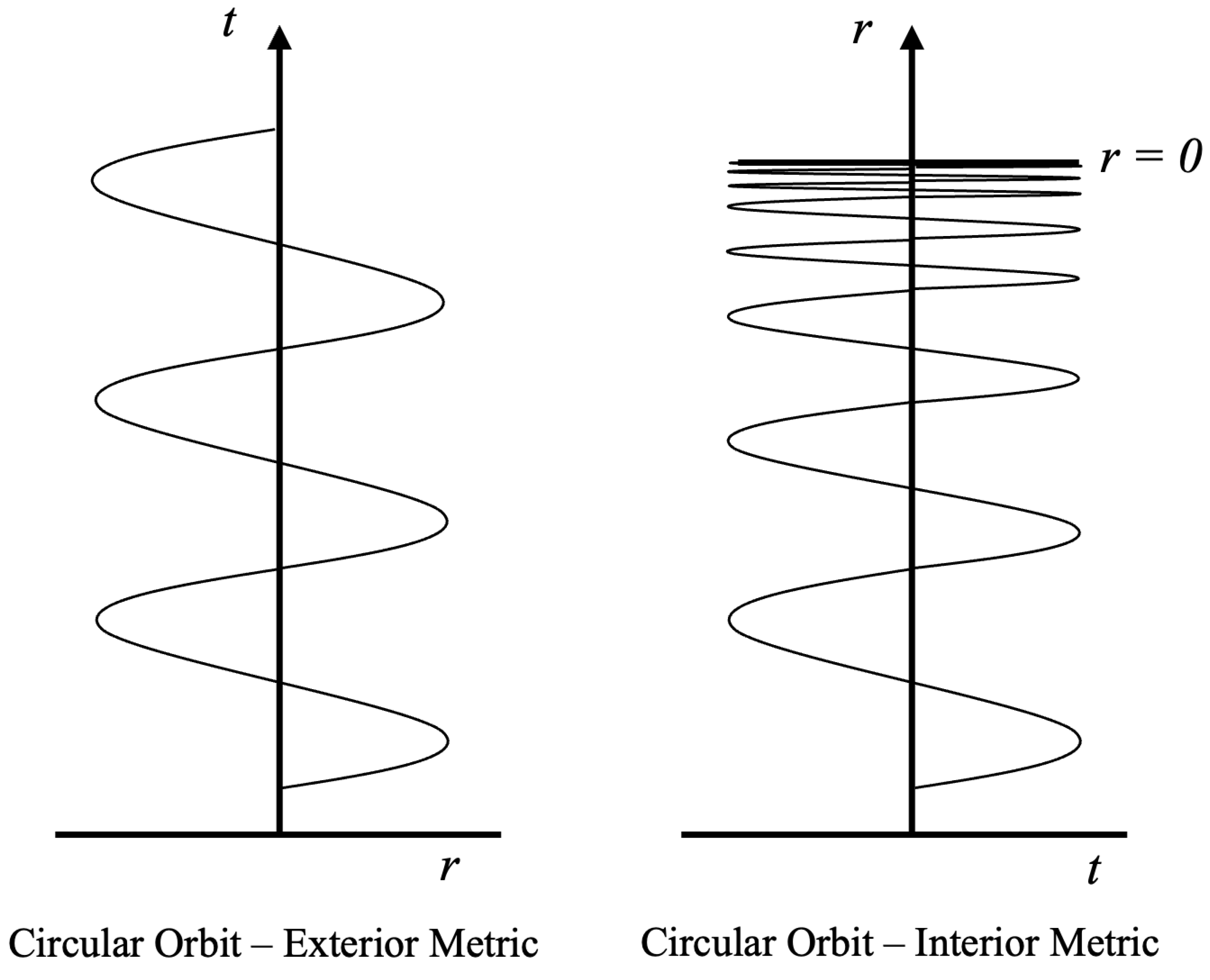

This can be visualized better by looking at the worldline of a circular orbit in the exterior and interior metrics as shown in

Figure 6:

Figure 6.

Worldlines of Circular Orbits in the Exterior and Interior Metrics

Figure 6.

Worldlines of Circular Orbits in the Exterior and Interior Metrics

On the left side of the figure, we see the circular orbit () in the exterior metric with time on the vertical axis and radius on the horizontal axis (a 2D projection of a 3D helix wrapped around the time axis). This a helix with constant radius r. The pitch of the helix is also a constant which means that the angular velocity of the worldline is constant over all time. Since the exterior metric is eternal, this helix can continue as shown for infinite t.

On the right side, we see the same circular orbit in the interior metric. First we note that the signature of the interior metric is flipped relative to the exterior metric and so the vertical time axis is now represented by the r coordinate and the horizontal space axis is represented by the t coordinate. Unlike in the exterior case, the interior metric is finite in time, so the worldline can not go beyond . But we see that the pitch of the helix decreases to 0 as r goes to zero as though the infinite worldline from the exterior metric has been compressed to fit the finite time of the interior metric. A smaller pitch leads to an increasing angular velocity since it implies more rotations per unit time as r goes to zero.

So for any planar motion,

and

in the interior metric. But the

coordinate will come in to play if the observer moves on, say, a helical path through space (different from the helical path through spacetime depicted in

Figure 6). On a planar, circular path, the observer would see the surrounding shell (if the shell were visible) spinning about an axis where the orientation of the axis remains fixed relative to the shell. On the helical path, the shell will be spinning around the observer, but the axis of the spin will change its orientation as the observer moves along the path and this is will introduce

into the calculation.

So we have demonstrated that the interior metric is homogeneous and isotropic in space and that the azimuthal term of the metric is describing the Thomas precession of the moving frame. In the next section, we will reinforce the idea that the azimuthal term is describing the precession of gyroscopes relative to the surrounding shell by comparing this to the role of gyroscopes in the exterior metric’s azimuthal term.