Submitted:

09 February 2023

Posted:

15 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Buffalo breeding

1.2. Buffalo physiology

2. Colostrum

2.1. Characteristics and composition

2.2. Colostrum quality

2.3. Colostrum analysis

3. Passive immunity transfer (PIT)

| Immunoglobulin | % |

|---|---|

| IgG (%) | 86 |

| IgA (%) | 8 |

| IgM (%) | 6 |

|

4. Evaluation and equipment

5. Colostrum management and the impact on calves

5.1. Colostrum Storage

5.2. Benefits of colostrum: infection prevention

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, A., Ahuja, S. P., Singh, B. Individual variation in the composition of colostrum and absorption of colostral antibodies by the precolostral buffalo calf. J. Dairy Sci. 1993, 76(4), 1148–1156. [CrossRef]

- McGrath, B., Fox, P., McSweeney, P., Kelly, A. Composition and properties of Bovine Colostrum: A Review. J. Dairy Sci. Tech. 2015, 96(2), 133–158. [CrossRef]

- Agenbag, B., Swinbourne, A. M., Petrovski, K., van Wettere, W. H. E. J. Lambs need colostrum: A Review. Livestock Sci. 2021, 251, 104624. [CrossRef]

- Mehra, R., Sangwan, K., Garhwal, R. Composition and Therapeutic Applications of Goat Milk and Colostrum. J. Dairy Sci.Tech. 2021, 10.2, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Zarrilli, A., Micera, E., Lacarpia, N., Lombardi, P., Pero, M. E., Pelagalli, A., d’Angelo, D., Mattia, M., Avallone, L. Evaluation of goat colostrum quality by determining enzyme activity levels. Livestock Prod. Sci. 2003, 83(2-3), 317–320. [CrossRef]

- Statistics BDN https://www.vetinfo.it/j6_statistiche/#/report-pbi/12.

- Statistics BDN 31/12/22 https://www.vetinfo.it/j6_statistiche/#/report-pbi/1.

- Reg. EC No. 1107 of 12 June 1996 registration of geographical indications and The Commission’s proposal for a Council Directive on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the classification of designations of origin within the framework of the procedure laid down in Article 17 of Regulation (EEC) No. Council Regulation. 2081/92 Official Journal No L 148, 21/06/1996 P. 0001-0010.

- Processing Nomisma on MDB Campania 2022 producers survey in collaboration with the Consortium of protection; provisional figure calculated on 80% of the certified volumes.

- Infascelli F., Gigli S., Campanile G. Buffalo meat production: Performance infra vitam and quality of meat. Vet Res Com. 2004, 28, 143–148. [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, S., Cutrignelli, M.I., Gonzalez, O.J., Chiofalo, B., Grossi, M., Tudisco, R., Panetta, C., Infascelli, F., Meat quality of buffalo young bulls fed faba bean as protein source. Meat Sci. 2014, 96(1), 591–596. [CrossRef]

- Cutrignelli, M. I., Calabrò, S., Tudısco, R., Chiofalo, B., Musco, N., Gonzalez, O. J., Grossi, M., Monastra, G., Infascelli, F., Conjugated linoleic acid and fatty acids profile in buffalo meat. Buffalo Bulletin 32(Special Issue 2), 2013, 1270–1273.

- Souza, D. C., Silva, D. G., Rocha, T. G., Monteiro, B. M., Pereira, G. T., Fiori, L. C., Viana, R. B., Fagliari, J. J. Serum biochemical profile of neonatal buffalo calves. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. e Zootec. 2019, 71(1), 187–196. [CrossRef]

- Wooding, F. B. P., Morgan, G., Adam, C. L. Structure and function in the ruminant synepitheliochorial placenta: Central role of the trophoblast binucleate cell in deer. Microsc. Res. and Tech. 1997, 38(1-2), 88–99. [CrossRef]

- Wooding, F. B. P. The synepitheliochorial placenta of ruminants: Binucleate cell fusions and hormone production. Placenta 1992, 13(2), 101–113. [CrossRef]

- Barrington, G. M., McFadden, T. B., Huyler, M. T., Besser, T. E. Regulation of colostrogenesis in cattle. Livestock Prod. Sci. 2001, 70(1-2), 95–104. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. N., Currie, A. J., Ren, S., Bering, S. B., Sangild, P. T. Heat treatment and irradiation reduce anti-bacterial and immune-modulatory properties of bovine colostrum. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 57, 182–189. [CrossRef]

- Brandon, M. R., Watson, D. L., Lascelles, A. K. The mechanism of transfer of immunoglobulin into mammary secretion of cows. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 1971, 49(6), 613–623. [CrossRef]

- Chernishov, V.P., Slukvin II. Mucosal immunity of the mammary gland and immunology of mother/newborn interrelation. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz) 1990, 38, 145–164.

- Norcross, N.L. Secretion and composition of colostrum and milk. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1982, 181(10), 1057-1060.

- Reber, A. J., Lockwood, A., Hippen, A. R., Hurley, D. J. Colostrum induced phenotypic and trafficking changes in maternal mononuclear cells in a peripheral blood leukocyte model for study of leukocyte transfer to the neonatal calf. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2006, 109(1-2), 139–150. [CrossRef]

- Parmely, M.J., Reath D.B., Beer A.E., et al. Cellular immune responses of human milk T lymphocytes to certain environ- mental antigens. Transplant. Proc. 1977, 91477–1483.

- Watson, D. L., Lascelles, A. K. Seasonal changes of buffalo colostrum: physicochemical parameters, fatty acids and cholesterol variation. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 1971, 49(6), 613–623. [CrossRef]

- Anantakrishnan, C. P., Bhale Rao, V. R., Paul, T. M., Rangaswamy, M. C. The component fatty acids of buffalo colostrum fat. J. Bio. Chem. 1946, 166(1), 31–33. [CrossRef]

- Stelwagen, K., Carpenter, E., Haigh, B., Hodgkinson, A., Wheeler, T. T. Immune components of bovine colostrum and MILK1. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87(suppl_13), 3–9. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D. M., Tyler, J. W., VanMetre, D. C., Hostetler, D. E., Barrington, G. M. Passive transfer of Colostral immunoglobulins in calves. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2000, 14(6), 569–577. [CrossRef]

- Squillacioti, C., De Luca, A., Pero, M. E., Vassalotti, G., Lombardi, P., Avallone, L., Mirabella, N., Pelagalli, A. Effect of colostrum and milk on small intestine expression of AQP4 and AQP5 in newborn buffalo calves. Res. Vet. Sci. 2015, 103, 149–155. [CrossRef]

- Pelagalli, A., Squillacioti, C., De Luca, A., Pero, M. E., Vassalotti, G., Lombardi, P., Avallone, L., Mirabella, N. Expression and localization of aquaporin 4 and aquaporin 5 along the large intestine of colostrum-suckling buffalo calves. Anatom. Hist. Embr. 2015, 45(6), 418–427. [CrossRef]

- Zarcula S. ,Cernescu H. , Mircu C. ,Tulcan C. ,Morvay A., Baul S. , Popovici D. Influence of Breed, Parity and Food Intake on Chemical Composition of First Colostrum in Cow. Anim. Sci. and Biotech. 2010, 43(1).

- Coroian, A., Erler, S., Matea, C. T., Mireșan, V., Răducu, C., Bele, C., Coroian, C. O. Seasonal changes of buffalo colostrum: Physicochemical parameters, fatty acids and cholesterol variation. Chem. Central J. 2013, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Roy. J. H. B., 1990. The calf. Butterworths. Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, John.

- Werner, Andrea. Experimentelle Untersuchungen zur Eignung der[gamma]-Glutamyltransferase-Aktivität im Blut von Kälbern zur Überprüfung der Kolostrumversorgung. Diss. Hannover, Tierärztl. Hochsch. 2003.

- Kehoe, S. I., Jayarao, B. M., Heinrichs, A. J. A survey of bovine colostrum composition and colostrum management practices on Pennsylvania Dairy Farms. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90(9), 4108–4116. [CrossRef]

- Mehra, R., Kumar, S., Verma, N., Kumar, N., Singh, R., Bhardwaj, A., Nayan, V., Kumar, H. Chemometric approaches to analyze the colostrum physicochemical and immunological (IGG) properties in the recently registered Himachali Pahari Cow Breed in India. LWT 2021, 145, 111256. [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, H., Pihlanto, A. Technological options for the production of health-promoting proteins and peptides derived from milk and colostrum. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007, 13(8), 829–843. [CrossRef]

- Ashok, N. R., Aparna, H. S. Empirical and bioinformatic characterization of Buffalo (bubalus bubalis) colostrum whey peptides & their angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibition. Food Chem. 2017, 228, 582–594. [CrossRef]

- Playford, R. J., Weiser, M. J. Bovine colostrum: Its constituents and uses. Nutrients 2021, 13(1), 265. [CrossRef]

- Parrish, D. B., Wise, G. H., Hughes, J. S., Atkeson, F. W. Properties of the colostrum of the dairy cow. V. Yield, specific gravity and concentrations of total solids and its various components of colostrum and early milk. J. Dairy Sci. 1950, 33(6), 457–465. [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Fattah, A. M., Abd Rabo, F. H. R., EL-Dieb, S. M., El-Kashef, H. A. Changes in composition of Colostrum of Egyptian Buffaloes and holstein cows. BMC Vet. Res. 2012, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Kilara, A., Vaghela, M. N. Whey proteins. Prot. Food Proc. 2004, 72–99.

- Barile, V. L. Improving reproductive efficiency in female buffaloes. Livestock Prod. Sci. 2005, 92(3), 183–194. [CrossRef]

- Coroian, A., Erler, S., Matea, C. T., Mireșan, V., Răducu, C., Bele, C., Coroian, C. O. Seasonal changes of buffalo colostrum: Physicochemical parameters, fatty acids and cholesterol variation. Chem. Cent. J. 2013, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., Ahuja, S. P., Singh, B. Individual variation in the composition of colostrum and absorption of colostral antibodies by the precolostral buffalo calf. J. Dairy Sci. 1993, 76(4), 1148–1156. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., He, Y., Pang, K., Zeng, Q., Zhang, X., Ren, F., Guo, H. Changes in milk yield and composition of colostrum and regular milk from four buffalo breeds in China during lactation. J. Sci. Food and Agr. 2019, 99(13), 5799–5807. [CrossRef]

- Barrington, G. M., Parish, S. M. Bovine neonatal immunology. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Prac. 2001, 17(3), 463–476. [CrossRef]

- Blum, J. W. Nutritional physiology of neonatal calves*. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl.) 2006, 90(1-2), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Penchev, G.I. Differences in chemical composition between cow colostrum and milk. Bulg. J. Vet. Med. 2008, No 1, 3−12.

- Blum, J. W., & Hammon, H. Colostrum effects on the gastrointestinal tract, and on nutritional, endocrine and metabolic parameters in neonatal calves. Livestock Prod. Sci. 2000, 66(2), 151–159. [CrossRef]

- Scammell A.W. Production and uses of colostrum. Aust. J. Dairy Technol. 2001, 56, 74.

- Golinelli L.P., Del Aguila E.M., Paschoalin V.M.F., Silva J.T., Conte-Junior C.A. Functional aspect of colostrum and whey proteins in human milk. J. Human Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 2, 1035.

- Aparna H.S, Veeresh S. Purification of an Antigenic Glycopeptide from buffalo colostrum February. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 38(5).

- Aparna, H. S., & Salimath, P. V. Galactose terminated oligosaccharides activate macrophage respiratory burst. Nutr. Res. 1994, 14(3), 433–444. [CrossRef]

- Chougule, R. A., Aparna, H. S. Characterization of β-lactoglobulin from Buffalo (bubalus bubalis) colostrum and its possible interaction with erythrocyte lipocalin-interacting membrane receptor. J. Biochem. 2011, 150(3), 279–288. [CrossRef]

- Ashok, N. R., Vivek, K. H., Aparna, H. S. Antioxidative role of Buffalo (bubalus bubalis) colostrum whey derived peptides during oxidative damage. Intern. J. Peptide Res. Therap. 2018, 25(4), 1501–1508. [CrossRef]

- Tsioulpas, A., Grandison, A. S., Lewis, M. J. Changes in physical properties of bovine milk from the colostrum period to early lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90(11), 5012–5017. [CrossRef]

- Doreau, M. Le lait de jument et sa production: Particularités et facteurs de variation. Le Lait 1994, 74(6), 401–418. [CrossRef]

- Rowan, T. G. Thermoregulation in neonatal ruminants. BSAP Occasional Publication 1992, 15, 13–24. [CrossRef]

- Quigley, J. D., Drewry, J. J. Nutrient and immunity transfer from cow to calf pre- and post-calving. J. Dairy Sci. 1998, 81(10), 2779–2790.

- Silva, F. L., Miqueo, E., Silva, M. D., Torrezan, T. M., Rocha, N. B., Salles, M. S., Bittar, C. M. Thermoregulatory responses and performance of dairy calves fed different amounts of Colostrum. Animals 2021, 11(3), 703. [CrossRef]

- Das, L.K., Behera, S., Colostrum: A wonder nutrition for newborn calves of cattle and buffaloes. Indian Farmer 2015, 2(3), 165-170.

- Gay C.C. The Role of Colostrum in Managing Calf Health. Diary Split Session I 1983.

- Aydogdu, U., Guzelbektes, H. Effect of colostrum composition on passive calf immunity in primiparous and Multiparous Dairy Cows. Veterinární Medicína 2018, 63(No. 1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Owen, W.; Griffith, R. J.; Meister, A. Transport of gamma-glutamyl amino acids: role of glutathione and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1979, 76, 6319-6322.

- Pero, M. E., Pelagalli, A., Lombardi, P., Avallone, L. Short communication: Glutathione concentration and gamma-glutamyltransferase activity in Water Buffalo Colostrum. J. Anim. Phys Anim. Nutr. 2010, 94(5), 549–551. [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, P., Avallone, L., Pagnini, U., D’Angelo, D., Bogin, E. Evaluation of buffalo colostrum quality by estimation of enzyme activity levels. J. Food Prot. 2001, 64(8), 1265–1267. [CrossRef]

- Morrill, K. M., Conrad, E., Lago, A., Campbell, J., Quigley, J., Tyler, H. Nationwide evaluation of quality and composition of colostrum on dairy farms in the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95(7), 3997–4005. [CrossRef]

- Pritchett, L. C., Gay, C. C., Besser, T. E., Hancock, D. D. Management and production factors influencing immunoglobulin G1 concentration in colostrum from Holstein Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74(7), 2336–2341. [CrossRef]

- Støy, A. C., Heegaard, P. M. H., Thymann, T., Bjerre, M., Skovgaard, K., Boye, M., Stoll, B., Schmidt, M., Jensen, B. B., Sangild, P. T. Bovine colostrum improves intestinal function following formula-induced gut inflammation in preterm pigs. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33(2), 322–329. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P., Gupta, R.A review on anticancer property of colostrum. Res. Rev.-J. Med. Heal. Sci 2016, 5, 1-9.

- JSM Biotechnol Bioeng 2016, 3(4), 1063.

- Ahmadi, M. Benefits of Bovine Colostrum in Nutraceutical Products. J. Agroalimentary Process. Technol. 2011, 17, 42–45.

- Abd El-Fattah, A. M., Abd Rabo, F. H. R., EL-Dieb, S. M., El-Kashef, H. A. Changes in composition of Colostrum of Egyptian Buffaloes and holstein cows. BMC Vet. Res. 2012, 8(1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Salar, S., Jafarian, S., Mortazavi, A., Nasiraie, L. R. Effect of hurdle technology of gentle pasteurisation and drying process on bioactive proteins, antioxidant activity and microbial quality of cow and buffalo colostrum. Intern. Dairy J. 2021, 121, 105138. [CrossRef]

- Borad, S. G., Singh, A. K.Colostrum immunoglobulins: Processing, preservation and application aspects. Intern. Dairy J. 2018, 85, 201–210. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Zhang, W., Han, B., Zhang, L., Zhou, P. Changes in bioactive milk serum proteins during milk powder processing. Food Chem. 2020, 314, 126177. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Zhang, W., Zhang, L., Hettinga, K., Zhou, P. Characterizing the changes of bovine milk serum proteins after simulated industrial processing. LWT 2020, 133, 110101. [CrossRef]

- Gelsinger, S. L., Jones, C. M., Heinrichs, A. J. Effect of colostrum heat treatment and bacterial population on immunoglobulin G absorption and health of neonatal calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98(7), 4640–4645. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L., Li, C., Boeren, S., Vervoort, J., Hettinga, K. Effect of heat treatment on bacteriostatic activity and protein profile of bovine whey proteins. Food Res. Intern. 2020, 127, 108688. [CrossRef]

- Chatterton, D. E., Aagaard, S., Hesselballe Hansen, T., Nguyen, D. N., De Gobba, C., Lametsch, R., Sangild, P. T. Bioactive proteins in bovine colostrum and effects of heating, drying and irradiation. Food & Function 2020, 11(3), 2309–2327. [CrossRef]

- Donahue, M., Godden, S. M., Bey, R., Wells, S., Oakes, J. M., Sreevatsan, S., Stabel, J., Fetrow, J. Heat treatment of colostrum on commercial dairy farms decreases colostrum microbial counts while maintaining colostrum immunoglobulin G concentrations. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95(5), 2697–2702. [CrossRef]

- McMartin, S., Godden, S., Metzger, L., Feirtag, J., Bey, R., Stabel, J., Goyal, S., Fetrow, J., Wells, S., Chester-Jones, H. Heat treatment of bovine colostrum. I: Effects of temperature on viscosity and immunoglobulin G level. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89(6), 2110–2118. [CrossRef]

- McGuirk, S. M.,Collins, M. Managing the production, storage, and delivery of Colostrum. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Prac. 2004, 20(3), 593–603. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D. M., Tyler, J. W., VanMetre, D. C., Hostetler, D. E., Barrington, G. M. Passive transfer of Colostral immunoglobulins in calves. J. Vet. Internal Med. 2000, 14(6), 569–577. [CrossRef]

- Radostits, O,M., Blood D.C., Gay C.C. Veterinary medicine: A textbook of the diseases of cattle, sheep, pigs, goats and horses. J. Eq. Vet. Sci. 2000, 20(10), 625.

- McGuire T. C., Pfeiffer N. E., Weikel J. M., Bartsch R. C. Failure of colostral immunoglobulin transfer in calves dying from infectious disease. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1976, 169(7), 713-8.

- Chase, C. C. L., Hurley, D. J., Reber, A. J. Neonatal immune development in the calf and its impact on vaccine response. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2008, 24(1), 87–104. [CrossRef]

- WittumT. E., PerinoL. J. Passive immune status at postpartum hour 24 and long-term health and performance of calves. “Am J Vet Res” Jour. 1995 56(9), 1149-1154. [CrossRef]

- Puppel, K., Gołębiewski, M., Grodkowski, G., Slósarz, J., Kunowska-Slósarz, M., Solarczyk, P., Łukasiewicz, M., Balcerak, M., Przysucha, T. Composition and factors affecting quality of Bovine Colostrum: A Review. Animals 2019, 9(12), 1070. [CrossRef]

- Stelwagen, K., Singh, K. The role of tight junctions in mammary gland function. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2013, 19(1), 131–138. [CrossRef]

- Stelwagen, K., Carpenter, E., Haigh, B., Hodgkinson, A., Wheeler, T. T. Immune components of bovine colostrum and MILK1. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87(suppl_13), 3–9. [CrossRef]

- Tong, F., Wang, T., Gao, N. L., Liu, Z., Cui, K., Duan, Y., Wu, S., Luo, Y., Li, Z., Yang, C., Xu, Y., Lin, B., Yang, L., Pauciullo, A., Shi, D., Hua, G., Chen, W.-H., Liu, Q. The microbiome of the Buffalo Digestive Tract. Nat. Commun., 2022 13(1),823. [CrossRef]

- Barmaiya, S., Aditi Dixit, Mishra, A., Jain, A.K., Gupta, A., Paul, A., Quadri, A.M., Madan, A.M., Sharma I. J. Quantitation of serum immunoglobulins of neonatal buffalo calves and cow calves through elisa and page: status of immune-competence. Buffalo Bulletin 2009 28(2), 85-94.

- Matte, J. J., Girard, C. L., Seoane, J. R., Brisson, G. J. Absorption of colostral immunoglobulin g in the newborn dairy calf. J. Dairy Sci. 1982, 65(9), 1765–1770. [CrossRef]

- Burton, J. L., Kennedy, B. W., Burnside, E. B., Wilkie, B. N.,Burton, J. H. Variation in serum concentrations of Immunoglobulins G, a, and M in Canadian holstein-friesian calves. J. Dairy Sci. 1989, 72(1), 135–149. [CrossRef]

- Besser, T. E., Garmedia, A. E., McGuire, T. C., Gay, C. C. Effect of colostral immunoglobulin G1 and immunoglobulin M concentrations on immunoglobulin absorption in calves. J. Dairy Sci. 1985, 68(8), 2033–2037. [CrossRef]

- Dang, A.K., Kapila, S., Tomar, P., Singh, C. Immunity of the buffalo mammary gland during different physiological stages. Asian Australasian J Anim Sci 2007a, 20, 1174–1181. [CrossRef]

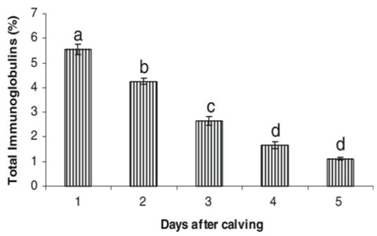

- Dang, A. K., Kapila, S., Purohit, M., Singh, C. Changes in colostrum of murrah buffaloes after calving. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2008, 41(7), 1213–1217. [CrossRef]

- Dang, A. K., Kapila, S., Purohit, M., Singh, C. Changes in colostrum of murrah buffaloes after calving. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2008, 41(7), 1213–1217. [CrossRef]

- Bulter, J.E. Bovine immunoglobulins: an augmented review. Vet. Immunol. Immunopath. 1983, 4, 43–152. [CrossRef]

- Gopal, P. K., Gill, H. S. Oligosaccharides and glycoconjugates in bovine milk and colostrum. British J. Nutr. 2000, 84(S1), 69–74. [CrossRef]

- Pero M.E., Luca A., Mastellone V., Mirabella N., Lombardi P., Tudisco R., Infascelli F., Avallone L., Romero F. Distribution of Ca2+-sensing receptor (CaSR) and Na-K-ATPase in the gastrointestinal tracts of neonatal calves after colostrum ingestion. Revista Veterinaria. 2010, 21 Issue 1, 620-622.

- Bhanu, L. S., Amano, M., Nishimura, S.-I., Aparna, H. S. Glycome characterization of immunoglobulin G from Buffalo (bubalus bubalis) colostrum. Glycoconj. J. 2015, 32(8), 625–634. [CrossRef]

- Sikka P. Lal D. Khanna S. Tomer A.K.S. Sethi R.K. Studies on colostrum minerals and their transfer to suckling calves in buffaloes- Ind. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 76 Issue 6, 480 - 483.

- Infascelli, F., Tudisco, R., Mastellone, V., Cutrignelli, M., Lombardi, P., Calabrò, S., Gonzalez, O. J., Pelagalli, A., Grossi, M.,d’Angelo, D., Avallone, L. Diet Aloe Supplementation in Pregnant Buffalo Cows Improves Colostrum Immunoglobulin Content. Revista Veterinaria. 2010, 21 Issue 1, 151-153.

- Mudgal, V., Bharadwaj, A., Verma, A. K. Vitamins supplementation affecting colostrum composition in Murrah Buffaloes. Ind J An Res, 2021 (OF). 55(8),900-904. [CrossRef]

- Ojha, B. K., Dutta, N., Pattanaik, A. K., Singh, S. K., Narang, A. Effect of pre-partum strategic supplementation of concentrates on colostrum quality and performance of buffalo calves. Anim. Nutr. Feed Technol. 2015, 15(1), 41. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, T. M., Yaseen, M., Nadeem, M., Murtaza, M. A., Munir, M. Physico–chemical composition and antioxidant potential of Buffalo Colostrum, transition milk, and mature milk. J. Food Proc. Pres. 2020, 44(10). [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, J., Jones, C. Colostrum management tools: hydrometers and refractometers. Penn State Extension. 2011.

- Thornhill, J. B., Krebs, G. L., Petzel, C. E. Evaluation of the brix refractometer as an on-farm tool for the detection of passive transfer of immunity in dairy calves. Aust. Vet. J. 2015, 93(1-2), 26–30. [CrossRef]

- Giammarco, M., Chincarini, M., Fusaro, I., Manetta, A. C., Contri, A., Gloria, A., Lanzoni, L., Mammi, L. M., Ferri, N., Vignola, G. Evaluation of brix refractometry to estimate immunoglobulin G content in buffalo colostrum and neonatal calf serum. Animals 2021, 11(9), 2616. [CrossRef]

- El-Loly, M. M., Mansour, A. I. A. Relationship between the values of density and immunoglobulin concentrations of buffalo’s colostrum and their thermal stability. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 13(8), 723–729. [CrossRef]

- McGuirk, S. M., Collins, M. Managing the production, storage, and delivery of Colostrum. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Anim. Prac. 2004, 20(3), 593–603. [CrossRef]

- Godden, S. M., Smith, S., Feirtag, J. M., Green, L. R., Wells, S. J., Fetrow, J. P.Effect of on-farm commercial batch pasteurization of Colostrum on Colostrum and serum immunoglobulin concentrations in dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86(4), 1503–1512. [CrossRef]

- Godden, S. Colostrum management for dairy calves. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Prac. 2008, 24(1), 19–39. [CrossRef]

- Cummins, C., Lorenz, I., Kennedy, E. Short communication: The effect of storage conditions over time on bovine colostral immunoglobulin G concentration, bacteria, and ph. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99(6), 4857–4863. [CrossRef]

- Foley, J. A., Otterby, D. E. Availability, storage, treatment, composition, and feeding value of surplus colostrum: A Review. J. Dairy Sci. 1978, 61(8), 1033–1060. [CrossRef]

- Manohar A.A., Williamson M., Koppikar G.V. Effect of storage of colostrum in various containers. Indian Pediatr. 1997, 34, 293–5.

- Piantedosi, D., Servida, F., Cortese, L., Puricelli, M., Benedetti, V., Di Loria, A., Manzillo, V. F., Dall’Ara, P., & Ciaramella, P. Colostrum and serum lysozyme levels in Mediterranean Buffaloes (bubalus bubalis) and in their newborn calves. Vet. Rec. 2010, 166(3), 83–85. [CrossRef]

- Paulik, S., Slanina, L., Polacek, M. Lysozyme in the colostrum and blood of calves and dairy cows. Vet. Med. (Praha) 1985, 30, 21-28.

- Foster, D. M., Smith, G. W. Pathophysiology of diarrhea in calves. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2009, 25(1), 13–36. [CrossRef]

- Khattar, S., Pandey, R. Cell culture propagation of calf rotavirus and detection of rotavirus specific antibody in colostrum and milk of cows and buffaloes. Rev. Sci. Tech. 1990, 9(4), 1131–1138. [CrossRef]

- Geletu, U. S., Usmael, M. A., & Bari, F. D. Rotavirus in calves and its zoonotic importance. Vet. Med. Intern. 2021, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Rast, L., Lee, S., Nampanya, S., Toribio, J.-A. L., Khounsy, S., & Windsor, P. A. Prevalence and clinical impact of Toxocara vitulorum in cattle and buffalo calves in northern Lao PDR. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2012, 45(2), 539–546. [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, R. P. V. J., Lloyd, S., Fernando, S. T. Toxocara vitulorum: Maternal transfer of antibodies from Buffalo Cows (bubalis bubalis) to calves and levels of infection with T vitulorum in the calves. Res. Vet. Sci. 1994, 57(1), 81–87. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, B., Fekete, P. Z. (Enterotoxigenic escherichia coli in veterinary medicine. Inter. J. Med. Microb. 2005., 295(6-7), 443–454. [CrossRef]

| Nutrient | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Fat (%) | 11.31 ± 0.39 |

| Protein (%) | 8.73 ± 0.15 |

| Lactose (%) | 3.73 ± 0.02 |

| Total Solids (%) | 25.31 ± 0.02 |

| Ash (%) | 0.94 ± 0.02 |

| pH | 6.01 ± 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).