1. Introduction

Aviation subsystem architectures are evolving substantially as a result of the More Electric Aircraft (MEA) concept, which, among other improvements, calls for the gradual replacement of hydraulic and Electro-Hydraulic Actuators (EHA) with Electro-Mechanical Actuators (EMA). In fact, it is believed that this paradigm shift would result in significant weight reductions, substantial Life Cycle Costs (LCC) savings [

1,

2], lower repercussion on the environment, and, last but not least, increased reliability of the entire aircraft system [

3].

Flight control surfaces in commercial aircrafts are currently actuated using FBW (Fly-By-Wire) technology: the pilot commands are translated into low-power electrical signals that are then managed by a computer and passed to hydraulic servovalves, which finally drive the appropriate aerodynamic surface and close the position control loop. The result is an electrical control which, however, still leverages hydraulic power [

4,

5]. The core concept is aiming at an all-in-one electrical solution that can meet the necessary safety criteria [

6,

7], encompassing the most power-demanding aircraft subsystems. The authors in [

8] provided a brief overview of the usage of EMAs and Electro-Hydraulic Actuators (EHA) on the most widespread aircraft platforms. In what is considered the forefather of the electric aircraft par excellence, the Boeing 787, EMAs and EHAs are already taking the place of hydraulic actuators. The latest versions of the Airbus A350 and A380 follow the same principle but EMAs are still only used for secondary flight controls (e.g. flaps, slats, spoilers), while EHAs are installed for both primary and secondary flight controls. It is clear that some challenges still limit a seamless replacement of EMAs in place of hydraulically driven actuation devices [

7,

9] for primary flight controls. This article follows the ideas presented in [

10] and aims to propose a possible step forward by exploiting prognostics. De facto, it is critical to evaluate the implications of the substitution of an hydraulic subsystem with its electrical alternative in terms of usage, implementation, monitoring, and the equipment’s reliability and safety. In the case of hydraulic systems, a potential failure (for example, a pressure drop caused by a leak) can be detected far before a load is demanded by appropriate pressure sensors.

Electrical system failures give rise to a completely different problem: new safety concerns are raised because no preventive mitigation plan can be implemented to reduce the impact of the fault itself if no additional auxiliary system is envisioned. As a consequence, the system must be exceedingly fault-tolerant. On top of that, EMAs show some issues which are less influential for hydraulic actuators, such as EMC, the mechanical jamming of the overall subsystem and overheating problems due to the high currents. A possible solution could be represented by hardware redundancy, however this would result in weight increases as well as incompatibilities with actuation requirements [

11], therefore reducing the benefits of MEA principles.

Prognostics main selling point stands in the capability of detecting and identifying component early failures and track down their progression during the equipment use. This result brings a lot of positive outcomes with it; one of the most important is definitely the possibility of exploring innovative types of maintenance strategies (CBM and opportunistic maintenance [

12,

13]). On top of that, Prognostics and Health Management (PHM) strategies could really be useful to back EMAs up in order for them to reach the required safety standards for safety-critical applications, such as primary flight control actuation. Prognostics can be then seen as an effective mean to assist EMAs thanks to its ability to identify hidden faults and prevent the related potential hazardous or catastrophic failure conditions. Prognostics sphere of influence stands in the monitoring and tracking of component or system parameters during their operation [

14]: in this way, by checking the operational values and physical outputs, incipient failures can be detected resulting in the improvement of mission readiness, upgrade of RAMS capabilities and a reduction of LCCs [

15,

16]. Prognostics can be categorized based on many different criteria. The most general one is linked to the way the data used for the comparison is generated: data-driven, model-based [

17,

18] or hybrid. The method followed by the authors in this work is strictly model-based due to the lack of enough real-life data to build the prognostic framework upon. The developed prognostic strategy is envisioned within an operational scenario and, as such, a general Concept of Operation (ConOps) is proposed along with the high-level Failure Detection and Identification (FDI) methodology. After that, a detailed explanation of the employed Metaheuristic Search Algorithms (MSAs) and a brief overview of the models is reported. Two different models are used in this work: an high fidelity one (RM-Reference Model) and a low fidelity counterpart (MM-Monitoring Model), the latter being in the core of the prognostic framework. This work continues the ongoing effort started in [

19], where a similar strategy was applied on brushless BLDC trapezoidal motors: in this case the employed motor is a sinusoidal PMSM motor. Finally, the results and comparisons between the algorithms are reported.

2. Materials and Methods

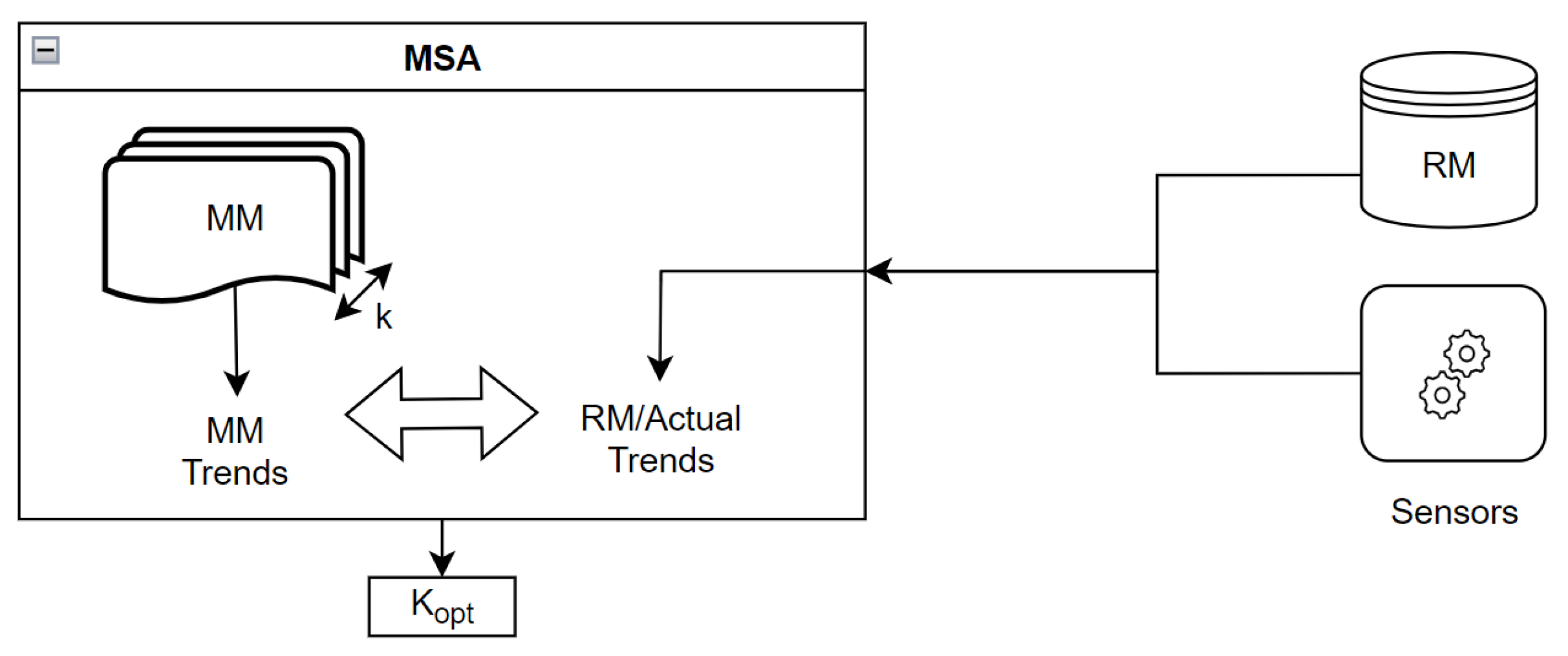

The proposed PHM strategy is built around the MM, whose simulations can be run almost in real time [

20,

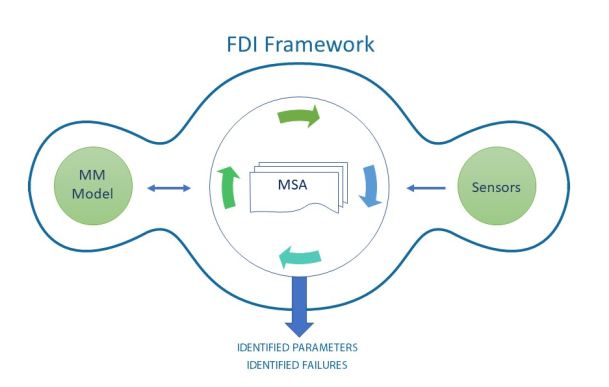

21]. The other inputs for the prognostic strategy are, of course, the signals coming from the sensors mounted on the physical system (as shown in

Figure 1).

However, real-life actuator data is difficult to obtain and the failures are very rare indeed. Therefore, in this study, data have been generated through the aforementioned RM, which has been used as a NTB. The authors set up the RM and generated the failure data; the prognostic algorithm was then employed to detect and identify the failures and, after its run, the results have been compared and the errors have been calculated.

Figure 1 shows the overview of the overall methodology. On the right, the reader can notice data coming from sensors or from the database created by the NTB.

The MM and the RM are defined by a set of Top Level Parameters (TLPs), grouped inside a vector, as better explained later on. Each component of the vector is linked and can be traced back to a failure in the EMA. By altering these parameters, it is possible to inject failures inside the models. To all intents and purposes, the TLPs change the simulation boundary conditions and, hence, it is possible to simulate the actuator behaviours in different conditions. Both models have been verified and experimentally validated under nominal and non nominal settings, proving the models’ capacity to estimate actual trends with high precision.

During a prognostic routine, the MM is then iteratively run with different sets of TLPs. In fact, in each simulation run, the TLPs are updated following the results obtained by the optimization using the MSA. The algorithm tries to find the monitoring TLPs that alter the MM outputs in order to reduce the error between the predicted and actual trends (real or simulated). A real-time solution is not feasible because of the total running time of the high number of simulation runs, as stated better later on. The error is defined using a suitable fitness function (Eq.

3). As a result, after the optimization process is complete, the output of the MM is extremely similar to the actual one. After finding a satisfactory match, the system’s health is evaluated by comparing the related TLPs with the related failures. Therefore, it is possible to execute a basic but effective FDI process by examining TLPs to determine whether a failure is occurring and establish what kind of failure it is.

As stated before and as [

22] explains, the TLPs are grouped inside a normalised vector

(Eq.

1): each component

is strictly linked to a physical system failure and it can assume values between 0 and 1 to characterize different failure magnitudes.

: dry friction. When , the resulting friction is the nominal value multiplied by three.

: backlash. When , the backlash magnitude is the nominal value multiplied by one hundred.

, , : short circuit. Being a three-phase motor, each coefficient is linked to a short circuit in one phase.

, : static eccentricity. These coefficients are linked to the modulus and phase of the eccentricity in the rotor. Under nominal conditions, the phase corresponds to 0 rad, so .

: proportional gain. is linked to an increase of 50 per cent in the proportional gain, while determines a 50 per cent decrease. The nominal value is .

The nominal vector (i.e. the vector whose components would lead to a nominal behaviour of the EMA) is hence the one reported (Eq.

2):

The fitness function is defined as:

where

and

are the MM and RM current outputs respectively at the instant time

i [

23].

2.1. Employed Algorithms

The authors used a specific kind of optimization method which fall into the category of metaheuristic bio-inspired algorithms. Optimization algorithms’ primary goal is to reduce or maximize an

objective function, also known as a

fitness function, by modifying the so-called

decision variables: in this case the

vector’s components, which are bound by established constraints [

24]. Although heuristic techniques cannot always guarantee the optimal result, they aim to produce satisfactory solutions, or solutions that are at least close to the optimal outcome, at a reasonable processing cost. MSAs use a variety of strategies to identify effective solutions to optimize problems starting from a large population of acceptable candidates, while making few assumptions about the problem being optimized [

25]. Furthermore, the algorithms are bio-inspired since they have underlying mechanisms based on biological processes. In fact, natural adaptation might be viewed as a type of optimization. In this work, the authors have approached on Evolutionary (EA) and Swarm Intelligence (SI) algorithms.

2.1.1. Evolutionary Algorithms

Evolutionary algorithms draw their inspiration from the natural evolutionary behavior. They are described by a few key characteristics and parameters:

population, the solution "pool", which is initialized at the start of the process;

variety: the population must be varied enough to explore the solution space effectively.

heredity: this values is linked to the capability of passing a characteristic to the offspring;

selection: for artificial algorithms selection must only occur in the desired direction, is a key parameter to ensure that only the best solutions will be reproduced.

Individuals serve as a representation of the different solutions, and a score known as fitness value is assigned to them by means of Eq.

3, calculated by analyzing the phenotype, or set of traits, of the subjects in question.

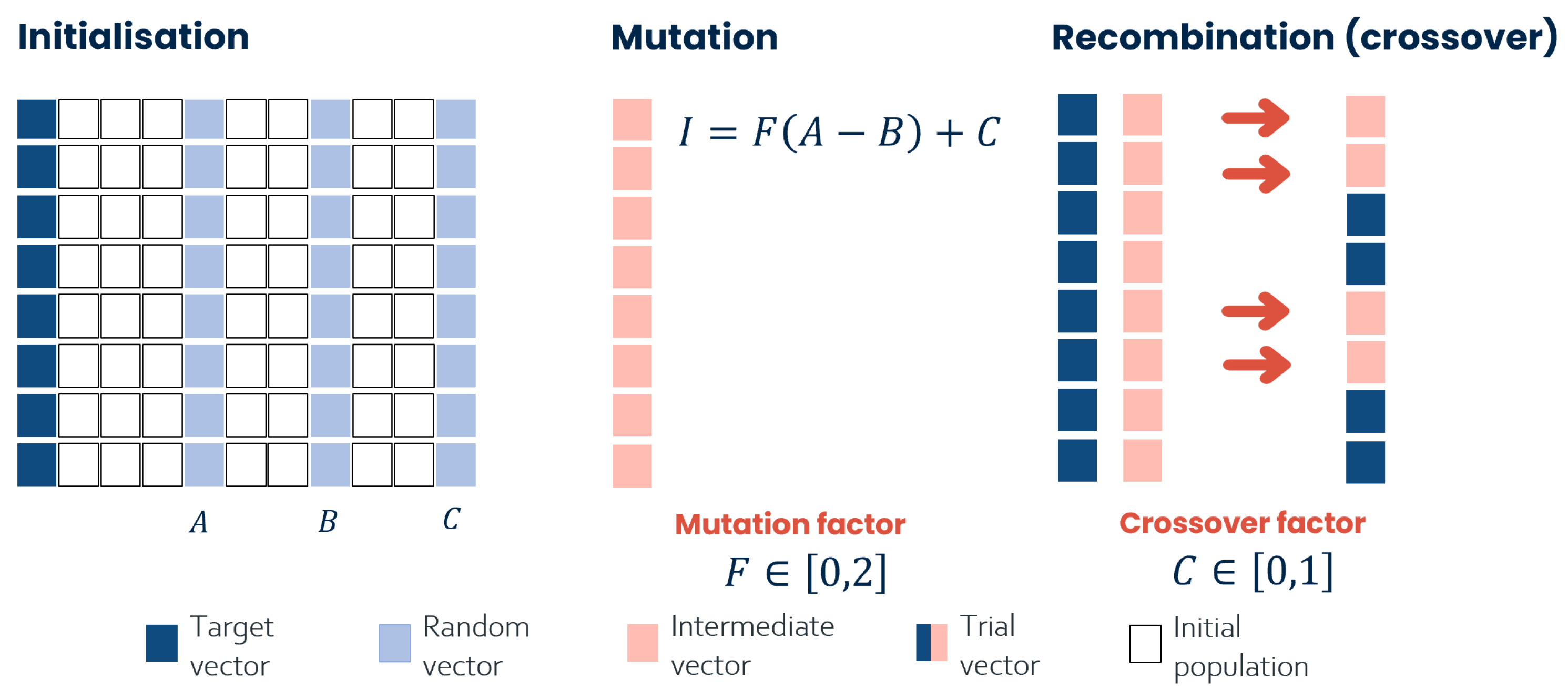

One of the most famous EA is the Differential Evolution strategy [

25,

26], which is also one of the tested algorithm in this work. The main concept of this algorithm follows the genetic principles.

Figure 2 shows the logical process behind this optimization algorithm. The process starts with a step called mutation: three individuals (three vectors in this case) are selected randomly from the population and a fourth vector is created by calculating the difference (the evolution is differential) between the first two vectors, multiplying it by a mutation factor and then adding the third one. The recombination or crossover phase begins at this stage, when the altered parameters of the starting vector are combined with those of the so-called target vector to produce the trial vector. The trial and target vectors are compared during the selection phase. If the trial’s score exceeds the target, it will be used as the next target; otherwise, it will be discarded. In the next generation, the vector with the highest fitness value will be maintained.

Genetic Algorithms are another popular EA optimization method (GA). In [

19,

27], a detailed investigation of the implementation of such algorithms on comparable challenges for PHM techniques was performed. However, in every test situation, the algorithms proposed in this research perform better.

2.1.2. Swarm Intelligence Methods

These methodologies are part of the Bio-Inspired category because they draw their inspiration from the behavior that may be observed when more than one entity (e.g. animal) interacts with other individuals. As stated before, the biological behaviours linked to the interaction between individual can result in a sort of optimization in the sense that the resources are shared and, thanks to the mutual collaboration, a solution is reached quicker. The result is a sort of information structure (which would not be present if the problem is approached by a single entity) that can be translated into mathematical formulations and hence used in optimization problems. The difference with EA is that, in this case, the process is interaction-driven by the entities’ behaviours (i.e. Collective Intelligence) and not controlled by genetic processes. The ability to exchange information and send or receive feedbacks from the other individuals inside the group is what makes the collective intelligence so powerful. In other words SI methods are the result of a very attentive observation of real-life actions between animals. As said before, two SI methods are approached in this study: Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Gray Wolf Optimization (GWO). In this case each individual is seen as a vector and, hence, as a possible solution.

Being a SI algorithm, PSO [

28] draws its inspiration from the movement of bird flocks or fish schools. In fact, starting from a population of potential solutions (i.e., particles) and moving them throughout the search space, this methodology can solve optimization problems following rigid mathematical formulas. As said before, the optimization is guaranteed by the fact that there is a capillary and diffused intelligence: the movement of each particle and hence, its path is affected by each particle’s local best known position and the best known locations in the search space (these are known because the knowledge is shared by particles). And that is precisely why: the swarm is able to iteratively identify the optimum solutions by information sharing. Some initial parameters shall be defined, such as the population size, particle initial placements and speed, particle inertia. After the initialization set up, each particle is given a random neighborhood and, by travelling, the best overall position is discovered. The position associated with the optimal global location are updated so that each particle knows it. A detailed examination of the solution space is possible thanks to the velocities’ inherent stochastic component [

29]. The employed code routine iteratively runs until 200 iterations are reached or until the error between two successive runs is less than

.

If PSO was generically inspired by birds’ and fishes’ movement, GWO [

30] has a more precise inspiring animal: wolves. This optimization technique follows the idea of the rigid hierarchical scales among grey wolf population’s members. After choosing the size of the wolf pack and the initial positions of each "animal", an initial population hierarchy is defined by looking at the the fitness function values. The decision of the number of wolves is crucial as both the accuracy of the algorithm and the execution time are affected by this parameter. The higher the fitness value, higher the hierarchical position in the scale. In this way, the individuals with lower scores will be less influential in the optimization process, while the better-positioned animals will lead the process. In other words, each wolf represents a distinct solution to the problem. The main difference with PSO lies in the fact that, in this case, the wolves cannot communicate their position to the other members of the pack. In order to find the best solution, an adequate population initialization and search method must be adopted [

31]. The size of the population has been set to 50 individuals. The optimization is stopped when the number of iterations reached is 150 or the tolerance of

is reached within two successive runs.

2.2. Models

The general architecture of an aeronautical EMA is extremely complex, characterized by multibody interactions and multiple non linearities and can be summed up as follows: a controller, an electric motor (usually PMSMs or BLDC motors), a gearbox and an intricate network of sensors for measuring currents, vibrations, voltages, temperatures etc. As a result, the system is made up of multiple interconnected hardware and software components. It is also required to investigate their cross-interactions so that the control system can appropriately fulfill its functions of monitoring, fault detection, and assessment of a possible divergence route.

As stated before, two models have been assembled in Simulink and then validated, thanks to experimental test rigs. The models are physical based and each component in real life is treated and modelled thanks to the appropriate equations. In other words, each block encloses the mathematical formulation by means of real formulas (e.g. electromagnetic formulas for the motor, dynamic equations for the physical systems etc).

If the RF has been built with a very high degree of precision, the MM has been conceived with approximations and lumped parameters so that an almost real-time use is more feasible; the computational cost is hence reduced. The thorough description of the model is way beyond the scope of this work. The interested reader should see [

32,

33] and [

20,

21] as far as the RF and MM models are concerned respectively.

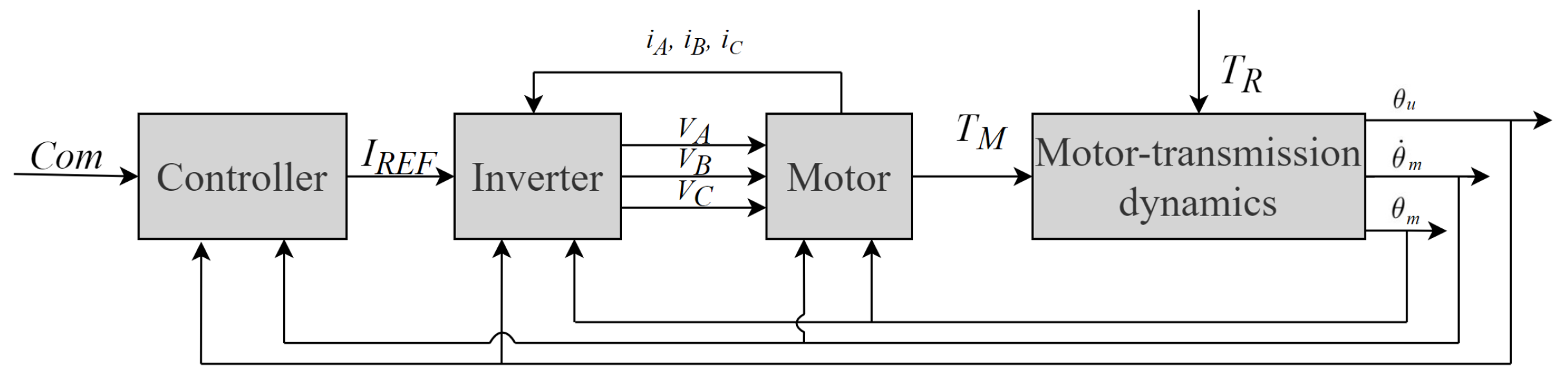

For reasons of clarity, a simple logical scheme of the HF model is shown in

Figure 3 while the four main blocks are quickly analysed below:

Controller: this block is essentially composed of a PID controller. In fact, even if there are much more advanced and sophisticated control logics, PID controllers are still the way to go and they are still chosen even in complex systems, as they are easy to implement and tune. PID controllers are composed of three separated branches, where the Proportional, Differential and Integral action are calculated. The controller aim is comparing the command signals with the actual signal obtained from the Motor-transmission dynamics block, hence closing the control loop. In this particular case, both position and speed can be monitored. This block outputs the reference current , obtained from the motor torque thanks to the torque constant, which is finally passed to the inverter.

Inverter: this block contains Clarke-Park equations and it provides the motor block with the three voltages (one for each phase) for the PMSM motor, by performing the corresponding Pulse Width Modulation (PWM). A very complicated physics based process is handled by Simscape, a specific Simulink library, capable of providing Electrical simulation packages. The main actions inside this block are: the calculation of the electrical angle starting from the motor position, the splitting of into the three phase currents (with Clarke-Park equations), the PWM process, and the calculation of the three phase voltages.

Sinusoidal BLDC motor: this block is able to simulate the electrical and magnetic interactions inside a PMSM. It contains Simscape element too and it manages three main processes: the calculation of the counter-electromotive force coefficient for each phase; the implementation of the motor RL circuit and the calculation of the motor available torque.

Motor-transmission dynamics: this final block compares the available torque with the external requested torque and solves a second-order dynamical system comprehensive of multiple non linearities, such as dry friction and backlash [

34]). The outputs of this block are the motor position and speed, which are looped back to the controller.

Following the results of a detailed EMA Failure Mode Effect and Criticality Analysis (FMECA) found in literature [

9], it was decided to take into account five distinct failures. These failures show a medium high or high probability and/or criticality for the overall EMA: dry friction, backlash, short circuit, eccentricity and proportional gain drift. For each failure mode, one or more

components have been assigned and two different levels of magnitude have been simulated: an high magnitude (

) and low one (

). In order to complete the analysis, also a condition with multiple failure affecting the EMA has been taken into account: the

vector used in this case is the one shown in Eq.

4.

A more in-depth explanation on the failure implementation and the modelling of each failure mode can be found in [

23,

35].

3. Results

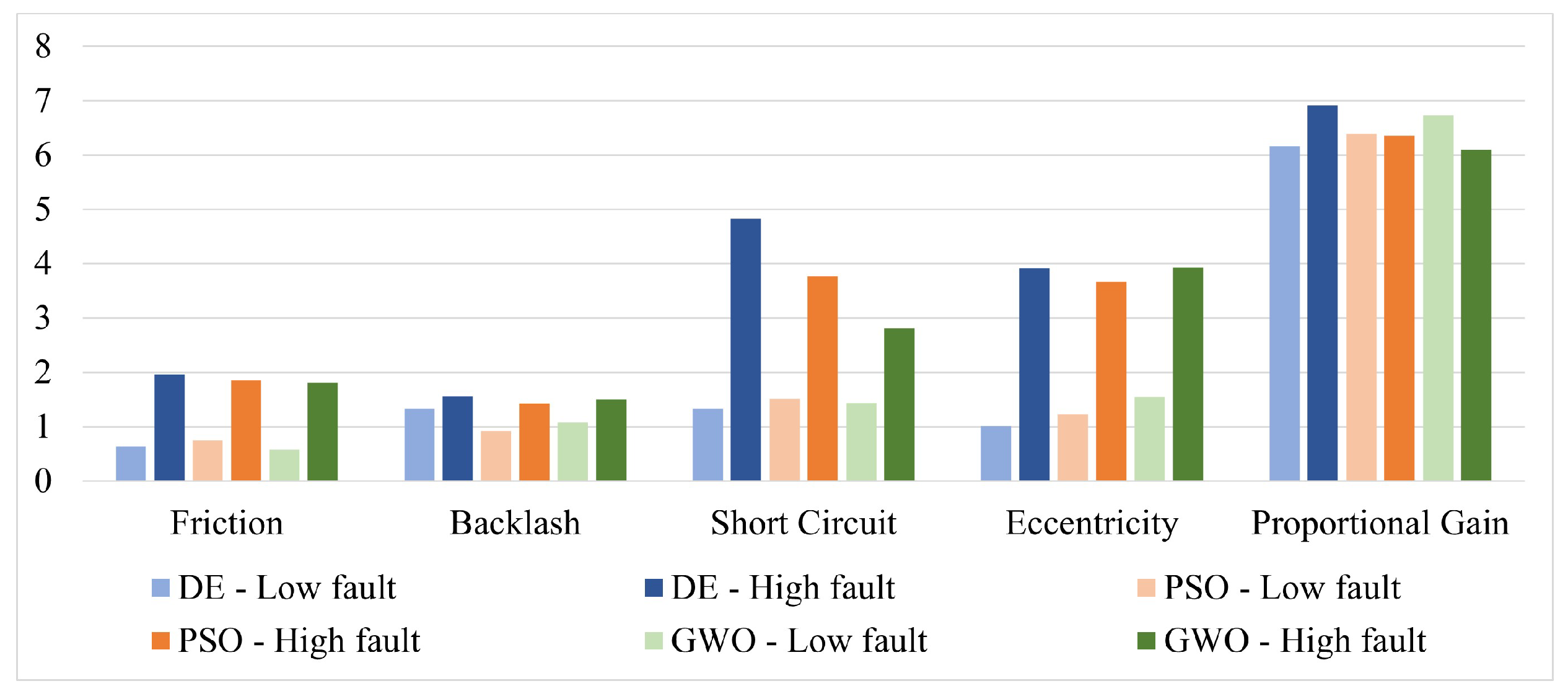

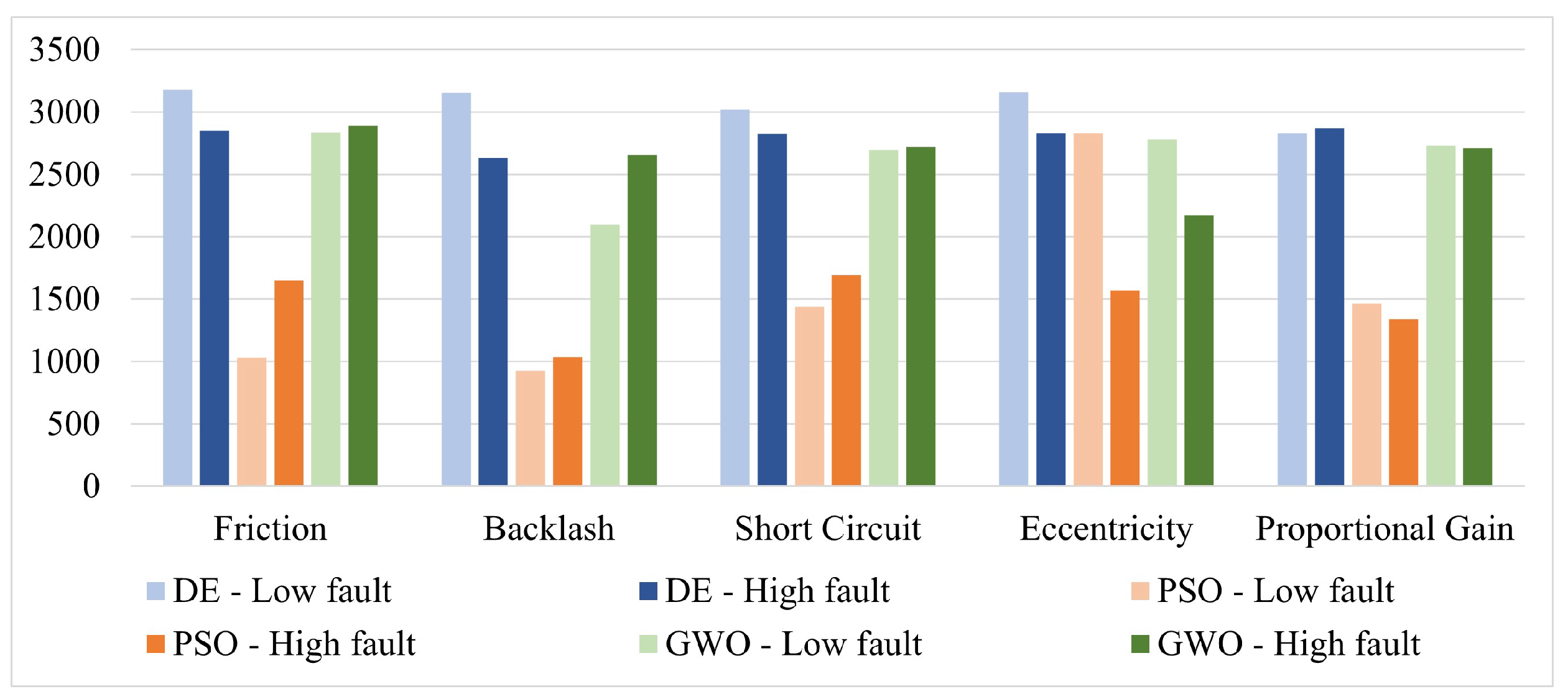

In this section the mean percentage error and the mean computational cost for each single failure and for the multiple failure situation are presented (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The error has been calculated following Eq.

5.

As stated before for each failure a low magnitude and a high magnitude condition have been considered.

These data have been obtained through ten runs of each algorithm for a total of 300 runs to have a minimal statistical relevance. DE shows a slightly lower error than the other algorithms as far as the low intensity failures are concerned. On the other hand, GWO seems to be the precise solution for the high level failures (e.g. short circuit and proportional gain). Finally, PSO algorithm turns out to be the most accurate for backlash faults in general, high static eccentricity and low proportional gain. Apparently there is not an algorithm able to outperform the others in every situation; this was expected as metaheuristic algorithms, despite being very versatile, are not the panacea for every problem. However, if we look at the computational cost, since a first glance it is clear that PSO is the most efficient algorithm. In fact, apart in case of the static low eccentricity failure, this optimization technique shows computational burdens almost halved with respect to the other algorithms, with an average 25 minutes to detect and identify the failures. If we now consider the other two remaining algorithms, GWO is slightly faster that DE but the last one seems to provide more stable and repetitive results.

The authors then used a predefined performance coefficient (PC) (first defined in [

22]) to take into the account both the accuracy (mean percentage error) and the computational cost in a single parameter, thus providing an objective criterion useful to choose the best solution overall.

The results of this further investigation are reported in

Table 1 along with other data to sum up the analysis. For reasons of brevity, the reported values of average percentage error and computational costs are obtained by an average between the two magnitude failures. As expected by linking the best results in term of accuracy and efficiency, PSO shows the highest figures for every failure. This happens not so much because of the error as to the significantly lower computational cost related to the PSO based solution.

On the opposite side of the ranking, there is clearly the DE algorithm. This is due to the very high computational cost.

The multiple failure condition results are reported in

Table 2. Once again, it is clear that PSO is the leading algorithm both in terms of efficiency and accuracy. Interestingly, it has to be highlighted that the multiple failure condition requires less than the single failure technique to reach a result. This was probably due to the stochastic operating principles of the algorithms. In fact, as the

vector contains random values (Eq

4) rather than just one component dissimilar from its nominal value, it is believed that the algorithms are able to approach the error tolerance more quickly.

4. Discussion

By looking at the results PSO is the leading algorithm, providing the best results for the single and multiple failure condition. It is deemed that this algorithm is able to outperform the others due to the main constructive principle behind it: unlike GWO there is a strong collaboration and sharing of information between particles. Each particle contributes to the creation of the aforementioned collective intelligence by sharing the information on the best position it has found in the solution space and, hence, the likelihood to find always better solution rises drastically. This does not happen with GWO which has a strong hierarchical law. DE showed incomparably worse results and its implementation is quite challenging too. It has to be noted that, even though the algorithms are metaheuristic and they pose few assumption on the application, they are very sensible to the problem statement and, thus, an algorithm could behave very badly on a specific situation but could provide excellent results when approaching an even slightly different problem.

The most challenging failure to detect and identify is the proportional gain drift. This particular phenomenon can be led back to the fact that a controller issue affects every single aspect of the actuation system and, hence, the prognostic system struggles to identify the specific problems. Percentage errors for this failure mode, albeit higher than the ones relative to the other failures, are restrained around

, which is a satisfactory result indeed. After checking the results of the different algorithms, the authors envisioned a wider and more comprehensive concept of operations which could provide a practical application of the prognostic checks. The proposed monitoring framework could be easily implemented in a check routine which could be run when the aircraft is on the ground and during the flight to check the EMA subsystem health status. For instance a monitoring procedure can be run while the aircraft is at the gate waiting for the passengers, during maintenance checks, even 24-hours or walk-around checks. Additionally, throughout the flying phase, a test procedure can be carried out at predetermined intervals. In this way, EMA health status is assessed and the mission safety is guaranteed. As seen before the proposed checks can not be run in real-time due to the needed number of simulation runs; on the other hand, a real-time monitoring capability is deemed superflous and unnecessary as failures usually have a progression curve that can be monitored. The proposed prognostic strategy is applicable to a wide range of actuators and do not require the installation of any additional sensors. A Prognostic and Health Management Computer (PHMC) in the avionic bay is needed to perform the calculations. Further research should focus on the ideal interval between prognostic checks in order not to jeopardize mission safety and not overloading the PHMC. Future work should also consider other MSAs and other failures inside the EMA as well as investigate on the unexpected result regarding the multiple failure condition running time. If we compare the results of this study (specifically for PMSM based EMAs) with the outcomes obtained in [

19] for BLDC based EMAs, it is clear that PSO is confirmed as the best performing algorithm even though the core of the system has changed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.L.D.L.; methodology, M.D.L.D.L.; software, M.D.L.D.L.; validation, I.Q.; formal analysis, I.Q.; investigation, I.Q.; resources, I.Q.; data curation, I.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.; writing—review and editing, L.B.; visualization, L.B.; supervision, M.D.L.D.L.; project administration, M.D.L.D.L.; funding acquisition, P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known conflict of interest nor competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MEA |

More Electric Aircraft |

| EMA |

Electro-Mechanical Actuator |

| PHM |

Prognostic and Health Management |

| PMSM |

Permanent Magnet Syncrhonous Motor |

| DE |

Differential Evolution |

| PSO |

Particle Swarm Optimization |

| GWO |

Grey Wolf Optimization |

| NTB |

Numerical Test Bench |

| LCC |

Life Cycle Costs |

| EHA |

Electro-Hydraulic Actuators |

| CBM |

Condition-Based Maintenance |

| RAMS |

Reliability, Availability, Maintenability and Safety |

| MM |

Monitoring Model |

| RM |

Reference Model |

| FDI |

Failure Detection and Identification |

| ConOps |

Concept of Operation |

| TLP |

Top Level Parameter |

| MSA |

Metaheuristic Search Algorithm |

| EA |

Evolutionary Algorithm |

| SI |

Swarm Intelligence |

| GA |

Genetic Algorithm |

| BLDC |

BrushLess Direct Current |

| PID |

Proportional Integral Derivative |

| PWM |

Pulse Width Modulation |

| FMECA |

Failure Mode Effect and Criticality Analysis |

| PC |

Performance Coefficient |

| PHMC |

Prognostic and Health Management Computer |

References

- Vercella, V.; Fioriti, M.; Viola, N. Towards a methodology for new technologies assessment in aircraft operating cost. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part G: Journal of Aerospace Engineering, 2021, Vol. 235. Issue: 8 ISSN: 20413025. [CrossRef]

- Hölzel, N.B.; Gollnick, V. Cost-benefit analysis of prognostics and condition-based maintenance concepts for commercial aircraft considering prognostic errors. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Prognostics and Health Management Society, PHM, 2015. ISSN: 23250178.

- Berri, P.C.; Dalla Vedova, M.D.; Mainini, L. Computational framework for real-time diagnostics and prognostics of aircraft actuation systems. Computers in Industry 2021, 132. arXiv: 2009.14645 Publisher: Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Gp Capt Atul, G.; Rezawana Islam, L.; Tonoy, C. Evolution of Aircraft Flight Control System and Fly-By-Light Flight Control System. International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering 2013, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, R. Evolution of aircraft flight control system and fly-by-light flight control system 2013. 3, 2250–2459.

- Telford, R.D.; Galloway, S.J.; Burt, G.M. Evaluating the reliability & availability of more-electric aircraft power systems. 2012 47th International Universities Power Engineering Conference (UPEC). IEEE, 2012, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Liu, G.; Shi, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, S.; Lim, T.C. A review of electromechanical actuators for More/All Electric aircraft systems. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, 2018, Vol. 232, pp. 4128–4151. Issue: 22 ISSN: 0954-4062. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Fan, I.S.; King, S. Failures Mapping for Aircraft Electrical Actuation System Health Management. PHM Society European Conference 2022, 7, 509–520, Number: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, E.; Saxena, A.; Bansal, P.; Goebel, K.F.; Curran, S. A Diagnostic Approach for Electro-Mechanical Actuators in Aerospace Systems. 2009 IEEE Aerospace conference. IEEE, 2009, pp. 1–13.

- Baldo, L.; Querques, I.; Dalla Vedova, M.D.L.; Maggiore, P. Prognostics of aerospace electromechanical actuators: comparison between model-based metaheuristic methods. 12th EASN International Conference on Innovation in Aviation & Space for Opening New Horizons, 2022.

- Kuznetsov, V.E.; Khanh, N.D.; Lukichev, A.N. System for Synchronizing Forces of Dissimilar Flight Control Actuators with a Common Controller. Proceedings of 2020 23rd International Conference on Soft Computing and Measurements, SCM 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Benedettini, O.; Baines, T.S.; Lightfoot, H.W.; Greenough, R.M. State-of-the-art in integrated vehicle health management. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part G: Journal of Aerospace Engineering, 2009, Vol. 223. Issue: 2 ISSN: 09544100. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; de Pater, I.; Boekweit, S.; Mitici, M. Remaining-Useful-Life prognostics for opportunistic grouping of maintenance of landing gear brakes for a fleet of aircraft. PHM Society European Conference, 2022, Vol. 7, pp. 278–285. Issue: 1.

- Swerdon, G.; Watson, M.J.; Bharadwaj, S.; Byington, C.S.; Smith, M.; Goebel, K.; Balaban, E. A Systems Engineering Approach to Electro-Mechanical Actuator Diagnostic and Prognostic Development. Machinery Failure Prevention Technology (MFPT) Conference., 2009.

- Rosero, J.A.; Ortega, J.A.; Aldabas, E.; Romeral, L. Moving towards a more electric aircraft. IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine 2007, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Garriga, A.; Ponnusamy, S.S.; Mainini, L. A multi-fidelity framework to support the design of More-Electric Actuation. 2018 Multidisciplinary Analysis and Optimization Conference; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, Virginia, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutharssan, T.; Stoyanov, S.; Bailey, C.; Yin, C. Prognostic and health management for engineering systems: a review of the data-driven approach and algorithms. The Journal of engineering 2015, 2015, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berri, P.C.; Dalla Vedova, M.D.L.; Mainini, L. Learning for predictions: Real-time reliability assessment of aerospace systems. AIAA Journal 2022, 60, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Vedova, M.D.; Berri, P.C.; Re, S. Metaheuristic Bio-Inspired Algorithms for Prognostics: Application to on-Board Electromechanical Actuators. Proceedings - 2018 3rd International Conference on System Reliability and Safety, ICSRS 2018, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Berri, P.C.; Dalla Vedova, M.D.L.; Maggiore, P. A Simplified Monitor Model for EMA Prognostics. MATEC Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, 2018.

- Berri, P.C.; Dalla Vedova, M.D.L.; Maggiore, P.; Viglione, F. A simplified monitoring model for PMSM servoactuator prognostics. MATEC Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, 2019, p. 04013.

- Dalla Vedova, M.D.; Berri, P.C.; Re, S. A comparison of bio-inspired meta-heuristic algorithms for aircraft actuator prognostics. Proceedings of the 29th European Safety and Reliability Conference, ESREL 2019, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Querques, I. Prognostics of on-board electromechanical actuators: Bio-Inspired Metaheuristic Algorithms. Technical report, Politecnico di Torino, 2021.

- Wahde, M. Biologically inspired optimization methods: an introduction; WIT press, 2008.

- Ahmad, M.F.; Isa, N.A.M.; Lim, W.H.; Ang, K.M. Differential evolution: A recent review based on state-of-the-art works. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2022, 61, 3831–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution–a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. Journal of global optimization 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimasso, A.; Berri, P.C.; Dalla Vedova, M.D. A genetic-based prognostic method for aerospace electromechanical actuators. International Journal of Mechanics and Control 2021, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. Proceedings of ICNN’95-international conference on neural networks, 1995, Vol. 4, pp. 1942–1948.

- Darwish, A. Bio-inspired computing: Algorithms review, deep analysis, and the scope of applications. Future Computing and Informatics Journal 2018, 3, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Advances in engineering software 2014, 69, 46–61, Publisher: Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, D. An astrophysics-inspired Grey wolf algorithm for numerical optimization and its application to engineering design problems. Advances in Engineering Software 2017, 112, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berri, P.C.; Dalla Vedova, M.D.L.; Maggiore, P.; Scanavino, M. Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (PMSM) for Aerospace Servomechanisms: Proposal of a Lumped Model for Prognostics. 2018 2nd European Conference on Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS). IEEE, 2018, pp. 471–477.

- Berri, P.C.; Dalla Vedova, M.D.; Maggiore, P. A lumped parameter high fidelity EMA model for model-based prognostics. Proceedings of the 29th European Safety and Reliability Conference, ESREL 2019. Research Publishing Services, 2020, pp. 1086–1093. [CrossRef]

- Baldo, L.; Berri, P.C.; Dalla Vedova, M.D.L.; Maggiore, P. Experimental Validation of Multi-fidelity Models for Prognostics of Electromechanical Actuators. PHM Society European Conference, 2022, Vol. 7, pp. 32–42. Issue: 1.

- Berri, P.C. Design and development of algorithms and technologies applied to prognostics of aerospace systems. PhD thesis, Politecnico di Torino, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).