Submitted:

17 January 2023

Posted:

18 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. A uniform spherical ball of fixed mass

3. Relativistic mass

4. Black Hole solution

5. Conclusion

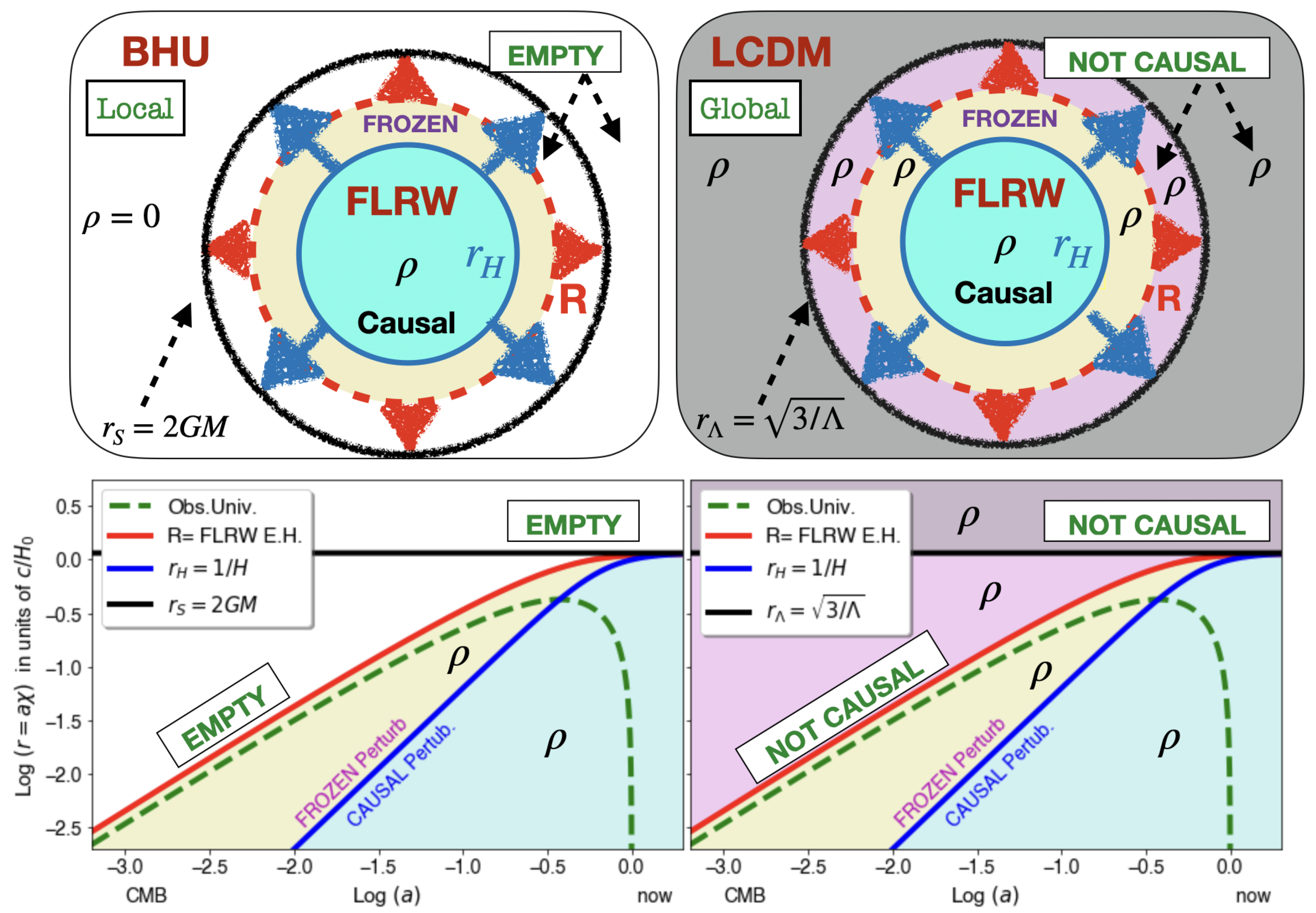

- Our Universe is a local solution inside its gravitational radius . It is therefore a Black Hole Universe (BHU).

- The dynamical time associated to M in our Universe is , which is close to the measured age of the oldest galaxies and stars that we observe.

- An observer placed anywhere within the local BHU measures the same background as one within the LCDM ([29]).

- Our BHU might not be unique: there could also exist other Universes, like ours, elsewhere. This is part of the The Copernican Revolution: our place is not special.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Dodelson, S. Modern cosmology, Academic Press, NY; 2003.

- Weinberg, S. Cosmology, Oxford University Press; 2008.

- Tolman, R.C. On the Problem of the Entropy of the Universe as a Whole. Physical Review 1931, 37, 1639–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, L.; Kleban, M.; Susskind, L. Disturbing Implications of a Cosmological Constant. J.of High Energy Phy 2002, 2002, 011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. Before the big bang: An outrageous new perspective and its implications for particle physics. Conf. Proc. C 2006, 060626, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenberger, R. Initial conditions for inflation — A short review. Int. Journal of Modern Physics D 2017, arXiv:hep-th/1601.01918]26, 1740002–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathria, R.K. The Universe as a Black Hole. Nature 1972, 240, 298–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, I.J. Chinese universes. Physics Today 1972, 25, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutsen, H. The idea of the universe as a black hole revisited. Gravitation and Cosmology 2009, 15, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckey, W.M. The observable universe inside a black hole. American Journal of Physics 1994, 62, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, J.R.; Snyder, H. On Continued Gravitational Contraction. Physical Review 1939, 56, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolin, L. Did the Universe evolve? Classical and Quantum Gravity 1992, 9, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easson, D.A.; Brandenberger, R.H. Universe generation from black hole interiors. J. of High Energy Phy. 2001, 2001, 024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghigh, R.G.; Kapusta, J.I.; Hosotani, Y. False Vacuum Black Holes and Universes. arXiv:gr-qc/0008006, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Firouzjahi, H. Primordial Universe Inside the Black Hole and Inflation. arXiv e-prints 2016, arXiv:1610.03767. [Google Scholar]

- Popławski, N. Universe in a Black Hole in Einstein-Cartan Gravity. ApJ 2016, arXiv:gr-qc/1410.3881]832, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshita, N.; Yokoyama, J. Creation of an inflationary universe out of a black hole. Physics Letters B 2018, 785, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymnikova, I. Universes Inside a Black Hole with the de Sitter Interior. Universe 2019, 5, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Diaz, P.F. The space-time metric inside a black hole. Nuovo Cimento Lettere 1981, 32, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grøn. ; Soleng, H.H. Dynamical instability of the González-Díaz black hole model. Physics Letters A 1989, 138, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, S.K.; Guendelman, E.I.; Guth, A.H. Dynamics of false-vacuum bubbles. PRD 1987, 35, 1747–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frolov, V.P.; Markov, M.A.; Mukhanov, V.F. Through a black hole into a new universe? Phys Let B 1989, 216, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A.; Johnson, M.C. Dynamics and instability of false vacuum bubbles. PRD 2005, 72, 103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, P.O.; Mottola, E. Surface tension and negative pressure interior of a non-singular `black hole’. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2015, 32, 215024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, J.; Vilenkin, A.; Zhang, J. Black holes and the multiverse. JCAP 2016, arXiv:hep-th/1512.01819]2016, 064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusenko, A.e. Exploring Primordial Black Holes from the Multiverse with Optical Telescopes. PRL 2020, arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2001.09160]125, 181304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaztañaga, E. How the Big Bang Ends Up Inside a Black Hole. Universe 2022, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E. The Cosmological Constant as Event Horizon. Symmetry 2022, 14, 300–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E. The Black Hole Universe, part I. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E. The Black Hole Universe, part II. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.X. The Principles and Laws of Black Hole Universe. Journal of Modern Physics 2018, 9, 1838–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, R.C. Effect of Inhomogeneity on Cosmological Models. Proc. of the Nat. Academy of Science 1934, 20, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misner, C.W.; Sharp, D.H. Relativistic Equations for Adiabatic, Spherically Symmetric Gravitational Collapse. Physical Review 1964, 136, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaître, G. Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extra-galactiques. Annales de la S.S. de Bruxelles 1927, 47, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, N.; Ravndal, F. On the discovery of Birkhoff’s theorem. General Relativity and Gravitation 2006, 38, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraoni, V.; Atieh, F. Turning a Newtonian analogy for FLRW cosmology into a relativistic problem. PRD 2020, 102, 044020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, S.A. Gravitational energy in spherical symmetry. Phys. Rev. D 1996, 53, 1938–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firouzjaee, J.T.; Mansouri, R. Asymptotically FRW black holes. Gen. Rel. Grav. 2010, arXiv:astro-ph/0812.5108]42, 2431–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.W. Role of Conformal Three-Geometry in the Dynamics of Gravitation. PRL 1972, 28, 1082–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, G.W.; Hawking, S.W. Cosmological event horizons, thermodynamics, and particle creation. PRD 1977, 15, 2738–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W.; Horowitz, G.T. The gravitational Hamiltonian, action, entropy and surface terms. Class Quantum Gravity 1996, 13, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DES Collaboration. Cosmological Constraints from Multiple Probes in the Dark Energy Survey. PRL 2019, arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1811.02375]122, 171301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosalba, P.; Gaztañaga, E. Explaining cosmological anisotropy: evidence for causal horizons from CMB data. MNRAS 2021, 504, 5840–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E.; Camacho-Quevedo, B. What moves the heavens above? Physics Letters B 2022, arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2204.10728]835, 137468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero, J.; Castander, F.J.; Gaztañaga, E.; Crocce, M.; Fosalba, P. An algorithm to build mock galaxy catalogues using MICE simulations. MNRAS 2015, 447, 646–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starobinskiǐ, A.A. Spectrum of relict gravitational radiation and the early state of the universe. Soviet J. of Exp. and Th. Physics Letters 1979, 30, 682. [Google Scholar]

- Guth, A.H. Inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems. PRD 1981, 23, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, A.D. A new inflationary universe scenario. Physics Letters B 1982, 108, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, A.; Steinhardt, P.J. Cosmology for Grand Unified Theories with Radiatively Induced Symmetry Breaking. PRL 1982, 48, 1220–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, A.R. Observational tests of inflation. arXiv e-prints 1999, arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/9910110. [Google Scholar]

- Novello, M.; Bergliaffa, S.E.P. Bouncing cosmologies. Phys.Rep 2008, 463, 127–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijjas, A.; Steinhardt, P.J. Bouncing cosmology made simple. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2018, 35, 135004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E. The size of our causal Universe. MNRAS 2020, 494, 2766–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E. The cosmological constant as a zero action boundary. MNRAS 2021, 502, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).