1. Introduction

Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) is an RNA arbovirus [

1] belonging to the Rhabdoviridae family and the

Vesiculovirus genus [

2] and causes an acute, contagious vesicular disease. To date, two VSV serotypes have been identified: Indiana (IN) and New Jersey (NJ) [

3]. Of these two serotypes, VSIV has three subtypes: VSIV 1 (Indiana 1), VSIV 3 or VSV-AV (Indiana 3 or Alagoas), and VSIV 2 (Indiana 2 or Cocal) [

4]. The serotypes that affect North, Central, and South America the most are VSNJV and VSIV 1 [

5], although VSIV 3 prevails in Brazil, and VSIV 2 has been reported in Brazil and Argentina [

6].

The usual hosts of VSV are generally mammals, such as cattle, horses, and pigs, but also arthropods and occasionally humans. This viral infection can be considered a minor zoonosis [

7]. Although vesicular stomatitis can be transmitted by direct contact and fomites, insects are believed to play a major role in transmission between animals [

8]. The insects that carry VSV are known to include sandflies, black flies, and biting midges. The ability of VSV to be transmitted through vectors is a great problem, since these vectors do not function only as simple means of transport, but also as a virus reservoir. Vector control, therefore, should form an integral part of controlling vesicular stomatitis outbreaks [

6,

9]. In Ecuador, vesicular stomatitis is a disease whose control is mainly based on quarantines and animal movement restrictions. Occasionally, a vaccine is used to try to reduce viral spread, namely a bivalent vaccine manufactured by VECOL, Colombia, which stimulates the production of specific antibodies [

10].

Vesicular stomatitis virus causes huge economic losses in cattle because of a considerable decrease in milk and meat production [

11]. In addition, because its clinical manifestations are extremely similar to those of foot-and-mouth disease, outbreaks of VS result in closing borders, livestock travel restrictions, and quarantine measures [

12]. Concerning the clinical signs of VS, after an initial febrile period, characteristic vesicular lesions occur on the muzzle, lips, tongue, ears, sheath, udder, ventral abdomen, and/or coronary bands of the hoof [

13]. The incubation period varies from 2–6 days with an average of 3–5 days in cattle, and visible vesicular lesions can appear 24 h after infection. The first sign of illness is often excessive salivation. In humans, the incubation period varies from 24 h to 6 days [

14].

Between January and December 2018, an outbreak of VS occurred in Ecuador with a total of 399 confirmed cases throughout 18 provinces. This outbreak has been described by Salinas et al. in an earlier publication [

15]. The main objective of their study was to characterize the temporal and spatial dynamics of the prevalence of VS. Their study determined that the highest number of VS cases happened between weeks 35 and 44. Concerning the etiological agent, 93.23% of the cases were positive for VSV-NJ, 5.52% for VSIV, and 1.25% for both serotypes. Similarly, it was noted that the outbreaks emerged at the end of the dry season and the beginning of the rainy season. It is therefore believed that this outbreak was caused by the movement of vectors. However, the origin of the outbreak remains unknown and the rapid spread of the outbreak within a few weeks throughout the whole country over several hundreds of kilometers cannot be attributed to transmission by vectors only. This study aimed to trace the origin of the outbreak and to determine transmission patterns through the construction of phylogenetic trees of the 2018 isolates and strains from an outbreak in Ecuador in 2004 [

16]. For this purpose, we used the nucleotide sequences of the hypervariable region of the phosphoprotein P of the virus that has been used extensively for VSV-NJ and VSIV phylogenetic analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Virus Isolation in Cell Culture

To obtain enough viral material, a cell culture of the isolates, previously stored in Gibco™ DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) culture medium and stored in liquid nitrogen, was initiated. The viruses were grown following the protocol established by the OIE Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals 2021, Chapter 3.1.23: Vesicular stomatitis (Version adopted in May 2021) [

17]. Briefly, the swabs with the VSV strains, stored in liquid nitrogen, were inoculated into cell culture vessels with BHK-21 cells and incubated at 37°C for 1 h [absorption]. After washing the cell cultures three times with cell culture medium, the cell culture medium was replaced with medium containing 2.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and incubated at 35–37°C and examined for cytopathic effect (CPE). At 24 h post-infection, a clarified medium of infected cells was frozen and used for RNA isolation. No additional strains were isolated after 48 h of incubation.

2.2. RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcriptase-PCR [RT-PCR]

For viral RNA extraction, the AccuPrep

® Viral RNA Extraction Kit (Bioneer, South Korea) was used following the protocol established by the manufacturer. To carry out the RT-PCR, two pairs of primers that amplified the VSV phosphoprotein gene (protein P) were used. The primers for VSNJV spanned a region of the gene between position 102 (P-NJ 102; 5’ GAGAGGATAAATATCTCC 3’) and 744 (P-NJ 744; 5’ GGGCATACTGAAGAATA 3’) and resulted in a fragment of 642 base pairs. The VSIV primers amplified a region between position 179 (P-Ind 179; 5’ GCAGATGATTCTGACAC 3’) and 793 (P-Ind 793; 5’ GACTCT(C/T)GCCTG(A/ G) TTGTA 3’) and resulted in a fragment of 614 bp [

17].

For the RT-PCR reaction, the MegaFi™ One-Step RT-PCR kit (ABM) was used, consisting of the following concentrations for a final volume of 15 μL: 0.3 μM of each primer, 1 ng/μL of RNA, 1X of One-Step RT-PCR Buffer, and 1U/μL RT-PCR Enzyme Mix. For reverse transcription, cDNA synthesis was performed at 60°C for 15 min. The amplification procedure started with an initial denaturation at 98°C for 30 s, followed by 35 cycles at 98°C for 10 s, 52°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and a final extension of 2 min at 72°C.

RT-PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis using 1.5% agarose gel, with SYBR Safe for visualization and 1X TBE as the buffer. Electrophoresis was run at 100 V for 30 min in a Labnet Enduro Gel XL horizontal chamber (Labnet International, Inc., USA). The gel was visualized on a Chem-iDocTM Imaging Systems (BioRad, USA) photographic documentation system and using Image LabTM software (BioRad, USA). The positive fragments were sequenced with Sanger sequencing an ABI 3500xL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA) by BigDye 3.1® capillary electrophoresis matrix.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.3.1. Construction of Phylogenetic Trees

For the generation of a consensus sequence of the P proteins of the VSNJV and VSIV isolates, forward and reverse sequences were aligned using the UniPro Gene program. Sequence contig reconstruction was performed using Assembler by MacVector software 17.5.5. [

18]. The sequence identity was confirmed by BLAST in NCBI resources. A total of 68 sequences of VSV from the United States, Mexico, Honduras, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Argentina, Brazil, El Salvador, Colombia, and Ecuador were retrieved from GenBank (All accession numbers, sample origin, serotypes, and isolates are described in

Supplementary Table S1) [

16,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. For the VSNJV analysis, we included as an outgroup two sequences of VSIV: an Indiana strain from Ecuador and one from Costa Rica with accession numbers EF028138.1 and EF028137.1 respectively. For VSIV analysis two of our VSNJV sequences (ON567174 and ON567120) were included as an outgroup. DNA sequences were aligned using MacVector 17.5.5 by the ClustalW algorithm with high gap creation and extension penalties by 30.0 and 10.0, respectively, searching for a strong positional homology.

Finally, the phylogenetic trees of VSNJV and VSIV isolates from Ecuador were built from the 2004 and 2018 isolates by using the maximum parsimony (MP) (100 replicates, reweighted under Rescaled Consistency index, RC index) using PAUP 4.0a [

30] and maximum likelihood (ML) analyses conducted in MEGA X [

31]. The ML tree was corrected with the Tamura 3-parameter model [

32]. The final trees for VSNJV and VSIV were edited using FigTree 1.4.4 [

33]. The robustness values for all the analyses were estimated using bootstrapping with 500 pseudo-replicates and are shown as percentages. A bootstrap re-sample with 1000 pseudo-replicates did not show significant differences in the values of the resulting topologies. The strain number of the 2018 samples, the GenBank accession number, the geographic origin in Ecuador, the month of isolation, and the serotype can be found in

Supplementary Table S2 together with the accession numbers of the sequence of the P gene from the outbreak in 2004 in Ecuador. We also built phylogram trees for VSNJV and VSIV with branch lengths proportional to the amount of evolutionary divergence among clades (

Supplementary Figures S1 and S2).

2.3.2. Haplotype Network of the VSNJV Sequences

The number and distribution of haplotypes were determined using the DnaSP software [

34]. The haplotype network was built using the PopART software package [

35] with the TCS network inference method, using the statistical parsimony method based on Templeton et al. [

36] and Clement et al. [

37] and implemented in TCS to visualize the mutation relationships. This approach identifies the number of haplotypes in the data and the number of evolutionary steps taken from one haplotype to another. TCS is useful in disentangling relationships at the intraspecific level. Finally, Tajima’s D was computed with the same software.

3. Results

From the 399 stored bovine epithelial tissue samples, 67 virus isolates (64 VSNJV and 3 VSIV strains) were successfully propagated in cell culture, amplified with RT-PCR, and sequenced for the P protein. Our sequences were uploaded to GenBank under the accession numbers ON567111-ON567177. See also supplementary

Table S2. Forward and reverse sequences were aligned using the UniPro Gene program and analyzed with the bioinformatic program MEGA-X together with the sequences of the P protein of 11 strains isolated from an outbreak in 2004, and described and deposited in GenBank by Sepúlveda et al. [

16]. For this purpose, the initial alignment matrix consisted of 614 bp and was trimmed to obtain a final alignment of 410 bp VSIV matrix. The VSVNJ sequences in the alignment matrix were trimmed to 422pb from an initial alignment of 642pb. The New Jersey and Indiana strains were separately analyzed.

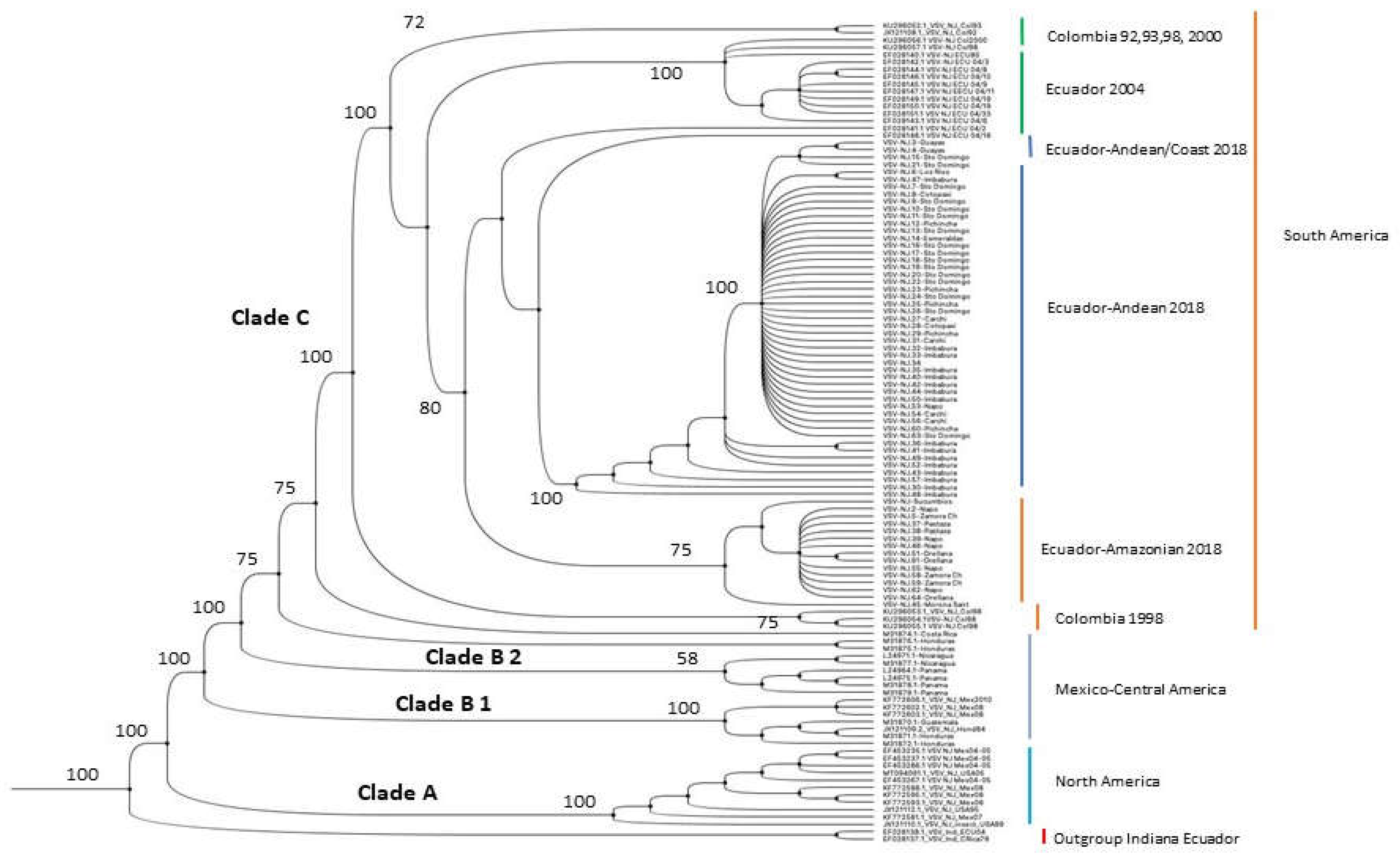

3.1. New-Jersey Phylogenetic Tree

The phylogenetic tree based on the nucleotide sequences of phosphoprotein gene (P) built for our 2018 and 2004 isolates from Ecuador and sequences from the Americas (

Figure 1) differentiated the strains into three supported clades (A, B, and C in

Figure 1). The internal monophyletic group, with Indiana strains from Ecuador and Costa Rica as outgroups, showed Clade A with North American strains (USA and Mexico), then Clade B with Mexican and Central American strains (B1 and B2 respectively), and the internal Clade C with South American strains including the Colombian strains and two internal subclades composed of Ecuadorian isolates of 2004 that were isolated in 6 different provinces (

Supplementary Table S1) and three internal Ecuadorian subclades (Ecuador-Andean/Coast, Ecuador-Andean and Ecuador-Amazonian) with our strains of 2018.

The 2018 epizootic subclade is formed by three lineages: the Amazonian and Andean with strong bootstrapping support (75 and 100% respectively) and a small number of unsupported Andean and Coastal strains.

The Amazonian strains come from the provinces of Napo, Morona Santiago, Pastaza, Zamora Chinchipe, Orellana, and Sucumbios. The strains of the Andean clade were isolated in the provinces of Imbabura, Pichincha, Carchi, and Cotopaxi, and the coastal lowlands strains were isolated in the provinces of Guayas, Los Ríos, Santo Domingo de Los Tsáchilas, and Esmeraldas. See also the supplementary

Figure 1 with a phylogram showing the VSNJV strains used in this publication.

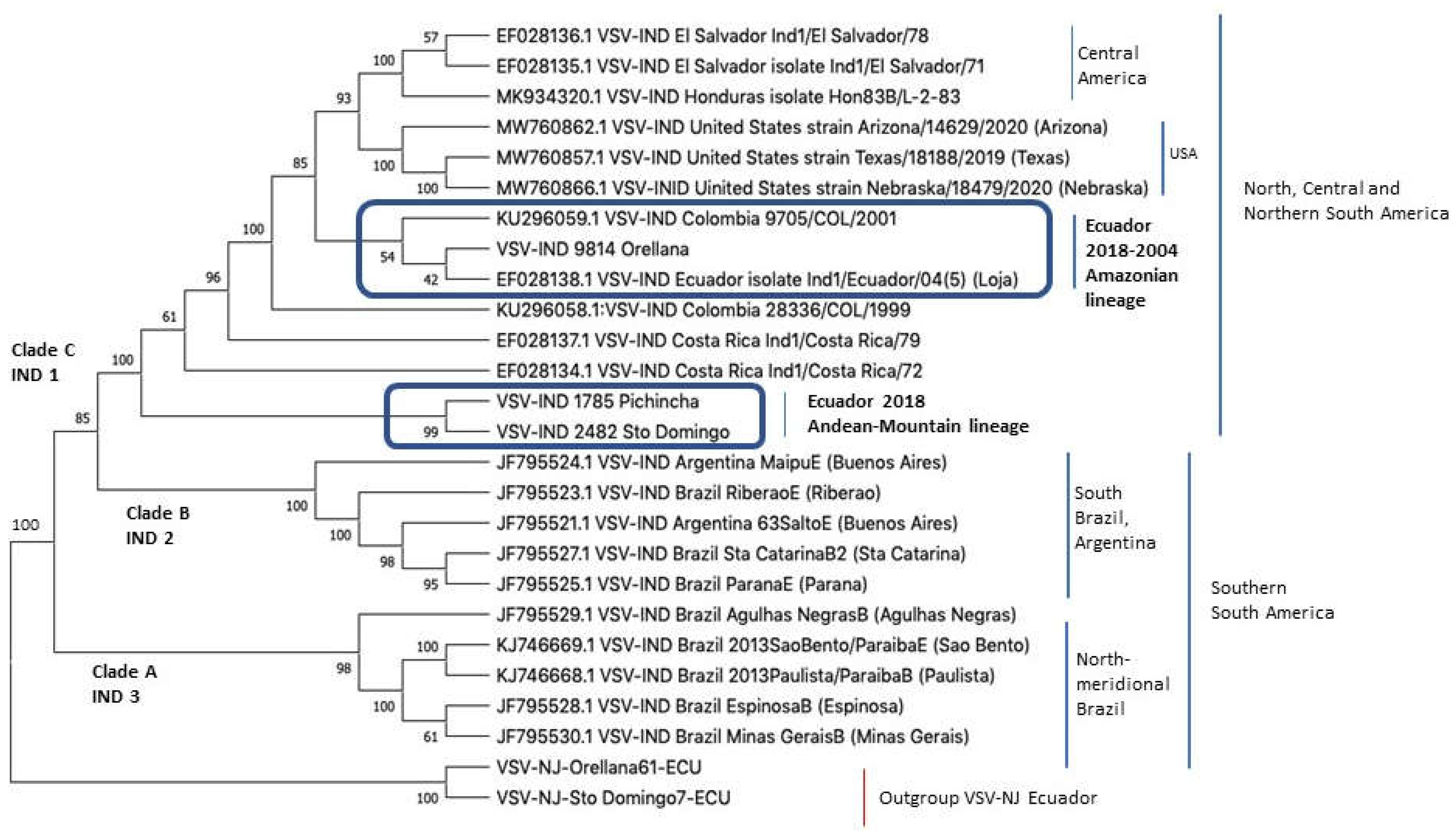

3.2. Indiana Phylogenetic Tree

Figure 2 shows the phylogeny of VSIV strains from Ecuador in comparison to additional sequences available from the Americas. Again, strains are region-specific in topology. The basal Clade A is comprised of northern and southern Brazil, the inner Clade B is formed by sequences from Argentina and southern Brazil, and Clade C by sequences from North, Central, and northern South America. Clade A corresponds to VSIV 2, Clade B to VSIV 3, and Clade C to VSIV 1. The strains from Ecuador are paraphyletic and have two different close ancestors to Clade C. The sequences from the Amazonian 2004 and 2018 (Loja and Orellana Provinces) strains have a Colombian ancestor, while the Andean-Coastal sequences (Pichincha and Santo Domingo de Los Tsáchilas) are located basally in Clade C and are closely related to the Brazilian and Argentinian Clade B. See also the

Supplementary Figure S2 with a phylogram showing a much lower divergence between the VSIV strains in comparison with the VSNJV strains shown in

Supplementary Figure S1.

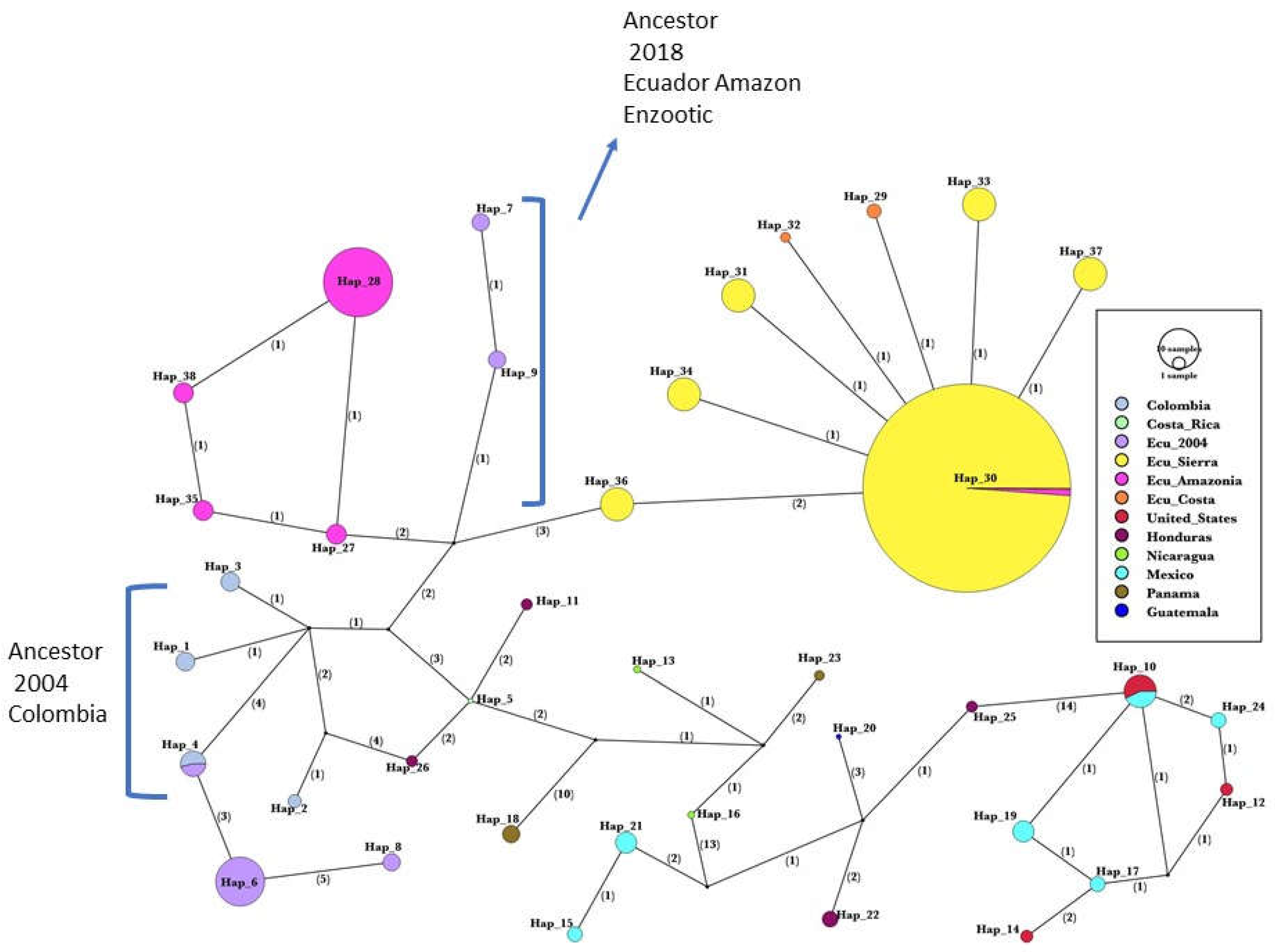

3.3. Haplotype Network Topology of VSV-NJ

The parsimony haplotype network (

Figure 3) shows a structured haplotype geographic distribution. Low down in the network, the same phylogenetic tree sequence transformation series is observed from haplotypes of North America, and Central America, finishing with Colombian haplotypes to the left side. One of them (H4) is shared with the Ecuadorian sequence of the 2004 outbreak, with two additional unique sequences from Ecuador: H6 and H8 with 3 and 6 mutations respectively. Then, high above in the network, the Colombian H3, which connects with the main Ecuadorian subnetwork as follows: 5, 7, and 10 mutations with Ecuador’s 2004 Amazonian outbreak (center in purple, from Orellana and Napo), Ecuador’s 2018 Amazonian outbreak (left in magenta) and 2018 Andean outbreak (right in yellow) respectively. Two unique Coastal haplotypes (H32 and H29 in orange) emerge from one mutation each from the most frequent haplotype in the Andes (H30). The 2018 outbreak haplotypes H27-Amazonian (left, magenta) and H36-Sierra (right, yellow) are closely and directly connected to the intermediate branch of the 2004 outbreak (H9, purple) in Ecuador using 3 and 4 mutations respectively.

4. Discussion

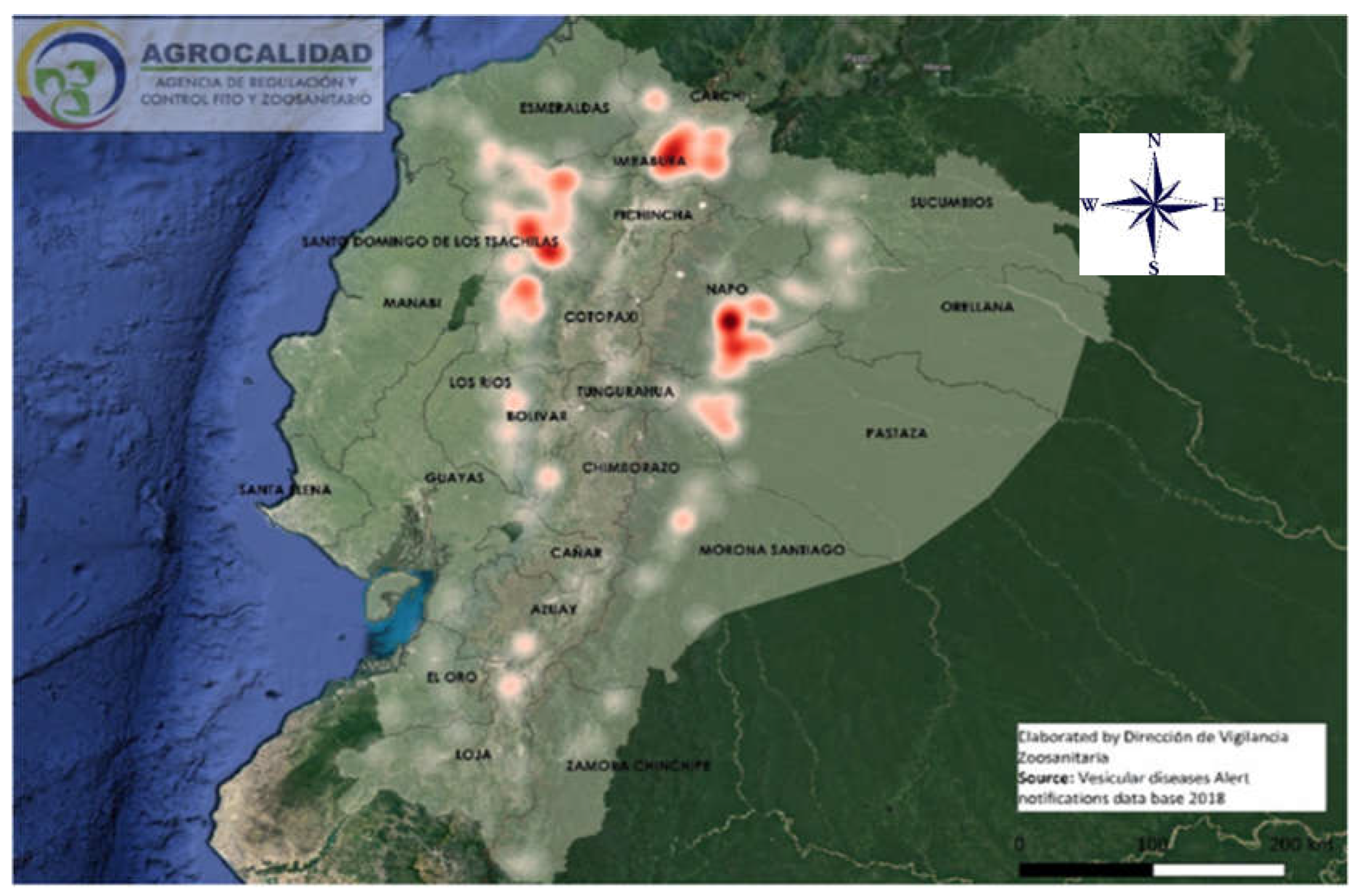

Vesicular stomatitis is known to be an endemic disease in North, Central, and South America, and outbreaks of the disease in Ecuador occur frequently. Between 2005 and 2014, Ecuador reported 182 outbreaks of VS to OIE-WAHIS (World Organization for Animal Health – Animal Health Information System). At that time, VS was a notifiable disease. However, due to the mild, self-limiting nature of the disease and improbable international spread through the trade of animals, VS was de-listed by the OIE as a reportable animal disease. Nonetheless, small VSV outbreaks have been reported every year in Ecuador, with a notable increase in 2018 with 399 registered outbreaks. Three factors likely favored the rapid spread of the disease in that year: the presence of vectors, climatic conditions, and, although self-quarantine measures were taken, the transport of cattle to auctions or between farms in the Andes highlands. In the next paragraphs, we discuss what are the likely causes (mechanisms) underlying transmission.

4.1. VSNJV Epidemiology

Concerning the VSNJV isolates, we show that two clades were present during the 2018 outbreak and these clades are geographically distinguishable from each other: one with three lineages in the Amazon and the other that infects animals on the Pacific coast and in the Andean highlands. This last clade consists of strains that are all closely related. The presence of two clades is possibly related to the fact that these regions are geographically separated by the Andes mountains that run from north to south, dividing the Ecuadorian mainland into three regions, from the west to the east: the Pacific coast, the Andean highlands, and the Amazon basin (see

Figure 4). Due to this geographic barrier, different virus populations have diverged, and thus different transmission patterns [

35].

Regarding the transmission of VSV in 2018, the analysis showed several small and independent outbreaks in the Amazon region and the spread of another outbreak caused by a homogeneous genetic variant in the eastern coastlands and the Andes. It is well known a large number of stomatitis infections are caused by vectors [

3,

39,

40] and the presence of several small, genetically variable, and frequent outbreaks each year in the Amazon region [

41] indicates transmission from different hosts, most probably insects or perhaps mammals [

42,

43,

44] and not due to contact between cows. Cow density is the lowest in this part of Ecuador, and most dairy farms are small-scale with only a few cows and little contact between cattle farms. We hypothesize that the outbreak in the eastern coastal lowlands and the Andes is most likely transmitted by the movement of livestock. The outbreak in this area took place over a relatively short time of 3 months (September-November see supplementary

Table S2) and spread over several hundreds of kilometers. Cow density is high in this region and cattle trade is much more common. The highest density of cattle in Ecuador is found in the coastal and highland regions with 42.4% and 48.4% of livestock respectively, while the remaining 9.2 % is found in the Amazon [

45]. If insects were involved in this outbreak, the genetic variation of the virus would have been more diverse due to the genetic adaptation of VSV to different insect reservoirs [

40]. Moreover, insects are rare, especially in the Andes region with a much colder climate than the Amazon region, thus separating the Amazon region from the Andes. A low density of cattle in the Amazon means fewer contacts between animals, thus transmission is mainly via insect bites. In the coastal region, cattle trade and movement are more frequent, increasing the risk of the virus infection being transmitted between animals and facilitating a rapid spread of the virus over hundreds of kilometers.

Concerning the origin of VSV in Ecuador, a comparison of the VSNJV sequences of Ecuador and other American countries shows that strains from Colombia and Ecuador have a high genetic homology, with more similarity in the provinces close to the border between the two countries. The basal position of the Colombian sequences in the phylogenetic tree provides some evidence that the virus, at some time before 2004, entered Ecuador from Colombia. The network topology suggests a Colombian origin for the 2004 outbreak (H4 shared, and H6, H8 closely connected), and an Ecuadorian 2004 variant, as a close ancestor of the 2018 outbreak. This is shown in the intermediate branch of H9 and H7 Amazonian strains that connect with the 2018 Ecuadorian subnetworks See

Figure 3, Of course, the haplotype network alone is not indicative of enzootic transmission in the Amazon. Many other factors such as geographical isolation and vector species play a role. The complete list of haplotypes and the countries where they were isolated is available in

Supplementary Table S3.

4.2. VSIV Epidemiology

Concerning the epidemiology and transmission of VSIV strains, only limited information can be deducted from our analysis. We sequenced the P gene of only 3 strains from the 2018 outbreak. Only one other strain from Ecuador, from the outbreak in 2004, is available in GenBank. The phylogenetic tree topology of our Amazonian sequences is closely related to a Colombia sequence. The Andean sequences, basal in the clade, are derivates from Brazilian-Argentinian sequences. This suggests two different origins for the virus from Ecuador that emerged simultaneously in 2018, but also an unknown enzootic transmission cycle as a precursor of the epizootics.

The origin of the strains closely related to the Colombia sequence can be explained by the close economical relationship between the two countries (cattle trade) and sharing of insect reservoirs. However, the simultaneous occurrence of two lineages in the 2018 outbreak in the Andean mountains in the South-Central-North America clade requires further studies.

4.3. Transmission by Vectors

Concerning the transmission of VSV by vectors, multiple studies have shown that different arthropods – such as

Lutzomyia sand flies,

Simulium black flies, and

Culicoides biting midges – are competent vectors in the transmission of VSV-NJ. Suspect vectors with a very low transmission probability include

Aedes mosquitoes. [

42,

43]. The virus is also maintained in sandflies by transovarial transmission and in

Culicoides by venereal transmission [

44,

45,

46]. Moreover, experimental studies have shown that cows exposed to the bites of these arthropods are capable of generating antibodies against VSV [

46,

47].

In Ecuador, VSNJV was isolated in 1976 in the mosquito

Mansonia indubitans [

47,

48], which breeds in lagoons with aquatic floating plants very common in the South American lowlands [

53]. This supports the idea of several insect reservoirs present in the Ecuadorian Amazon causing regular, although not always detected, enzootic transmission, with eventual emerging epizootics as in the 2004 and 2018 Amazonian outbreaks. Most probably several genetic variants of the virus exist in the Amazon. The outbreaks took place in counties several hundred kilometers separated indicating that different gene pools of the virus could exist. For Influenza A it has been shown that host and geographic barriers shape the competition, extinction, and coexistence patterns of H1N1 lineages and clades. [

56] Also, like the Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, a different and enzootic vector can be present in the Amazon or the interface between forest and agriculture [

49,

50]. It has been demonstrated that the genetic diversity of the West Nile virus depended on the mosquito species [

57]. If different hosts for the virus exist in the Amazon these hosts most probably will transmit different lineages.

Therefore, systematic surveillance of potential sylvan vertebrates and insect vectors should be performed in those areas close to the epizootic areas to elucidate the mechanisms of emergence and re-emergence of VSV. The virus could also have spread thanks to the interaction with vertebrate animals, such as bats, deer, monkeys, and herbivorous rodents, which tend to serve as amplifiers since in these organisms sustainable levels of viremia can occur [

42,

43,

48,

49,

50].

5. Conclusions

The two clades in the VSNJV phylogenetic tree of the 2018 outbreaks suggest a different transmission pattern in the Andean and Amazon regions. In the Amazon, the genetic diversity of the sequenced virus suggests transmission by vectors as a possible source of infection. In this region vector control measurements, to limit vector exposure and dispersion, are required to control viral spread. Vector control is very important for the control of virus spread as has been shown for the management of the spread of VSV in equines in the USA [

57]

In the Andean region, a group of genetically identical viruses was found, suggesting transmission of the virus through cattle movement. Because of the relatively cold climate in this region and the low density of insects, transmission from other reservoirs plays a most probably minor role. A future clonal spread of the virus can be avoided when strict cattle movement restrictions are established at the first detection of infected animals.

6. Recommendations

South American countries lack surveillance of VSV vectors and knowledge of reservoirs and vectors. We recommend carrying out vector and sylvatic vertebrate reservoir research and surveillance in tropical and subtropical areas where wild reservoirs can be a source of new outbreaks.

In Ecuador, VS is a disease whose control is mainly based on self-quarantine. Also, a commercial bivalent vaccine (VECOL, Bogota, Colombia) is occasionally used in Ecuador to reduce viral spread. However, no efficacy studies are available for this vaccine. Therefore, studies should be planned to show the efficacy of this vaccine in overcoming the spread of the virus. Although there is limited data on VECOL vaccine efficiency, other studies have shown protective immunity in cattle vaccinated on a commercial scale with inactivated, bivalent vesicular stomatitis vaccines [

54]. It is also important to address how the vaccination status of neighboring countries might contribute to VSV mutations and spread in Ecuador. However, there is no public information about vaccination frequency in neighboring countries.

7. Limitations of the Study

Our analysis is based on 67 strains, only a small fraction of the 399 registered outbreaks in 2018. It is also possible that many more outbreaks took place in that year that was not reported. And thus, our sample is not a fair representation of the research population, possibly introducing a bias in our results.

To obtain enough viral material for this study, a cell culture of the VSV isolates, previously stored in a culture medium and stored in liquid nitrogen, was initiated. Cell culture propagation of the virus can introduce mutations that might not reflect the ancestral state of the original isolates. We examined the literature and it has been shown that, that only four single-nucleotide substitutions in 77,500 bases were found in the VSV genes after cell propagation (a mutation frequency of 5.16×10

−5) [

55], and our study is based on the sequencing of only about 27,470 bp. More indications that no mutations were introduced during cell propagation are the sequences of the strains circulating in the Andes. All 35 VSV strains, isolated on different time points and again grown in cell culture, amplified, and sequenced, had an identical sequence of the partially amplified P protein. We, therefore, believe that cell propagation did not introduce a bias in our study.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Information about the geographical origin of the virus isolates used in this study, specifying the parish, canton, and province and, in addition, isolation date (month) and serotype; Table S2: Sequences obtained from GenBank NCBI-Nucleotide. The table shows the country of origin of the sample, accession number, name of the strain or isolate, and reference from where it was extracted; Table S3: Complete list of haplotypes. Figure S1: a scaled VSNJV phylogenetic tree. Figure S2: a scaled VSIV phylogenetic tree.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AM, ET, JCN, and JHdW; methodology: DA, CBC, AM, and DV; software: DV, MSC, JCN, and AM; formal analysis: DA, AM, DV, MSC, JCN, and JHdW; data curation: DA, AM, DV, JCN, and JHdW; writing—original draft preparation: DV, JCN, and JHdW; writing—review and editing: DA, AM, ET, CB, DV, MSC, JCN, and JHdW; visualization and supervision: AM, DA, ET, JCN, and JHdW; project administration: ET, AM, and JHdW; funding acquisition: ET, JCN, and JHdW. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received internal funding from the Agencia de Regulación y Control Fito y Zoosanitario (AGROCALIDAD), from the Universidad de Las Américas (UDLA), Quito, Ecuador, and P0116171_2 from the Universidad Internacional SEK (JCN).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Agencia de Regulación y Control Fito y Zoosanitario (AGROCALIDAD).

Data Availability Statement

Our sequences were uploaded to GenBank under the accession numbers ON567111-ON567177.

Acknowledgments

We thank field technicians, General Coordination of Animal Health, and General Coordination of Laboratories of the Agencia de Regulación y Control Fito y Zoosanitario (AGROCALIDAD) for responding to case notifications in various Ecuadorian provinces, managing animal health programs to raise animal health standards in the country, and managing resources for the development of diagnostic activities. We also thank the General Directorate of Research and Development of Universidad de Las Américas (UDLA) for allowing molecular tests to be carried out in their laboratory facilities. For discussions on the phylogenetic analysis, we recommend writing to Juan-Carlos Navarro: juancarlos.navarro@uisek.edu.ec; +593 99 547 9569.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Velazquez-Salinas L, Zarate S, Eschbaumer M, Pereira Lobo F, Gladue DP, Arzt J, et al. Selective Factors Associated with the Evolution of Codon Usage in Natural Populations of Arboviruses. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016 Jul 25;11(7):e0159943–e0159943. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27455096. [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Salinas L, Pauszek SJ, Holinka LG, Gladue DP, Rekant SI, Bishop EA, et al. A Single Amino Acid Substitution in the Matrix Protein (M51R) of Vesicular Stomatitis New Jersey Virus Impairs Replication in Cultured Porcine Macrophages and Results in Significant Attenuation in Pigs. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2020 May 29;11:1123. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32587580. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez LL. Emergence and re-emergence of vesicular stomatitis in the United States. Virus Res. 2002 May;85(2):211–9. [CrossRef]

- CFSPH. Estomatitis vesicular [Internet]. Center for Food Security & Public Health. 2008 [cited 2021 Apr 24]. Available from: https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/es/!replaced/!estomatitis_vesicular.pdf.

- Rodriguez LL, Bunch TA, Fraire M, Llewellyn ZN. Re-emergence of vesicular stomatitis in the western United States is associated with distinct viral genetic lineages. Virology. 2000 May;271(1):171–81. [CrossRef]

- Rozo-Lopez P, Drolet BS, Londoño-Renteria B. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Transmission: A Comparison of Incriminated Vectors. Insects [Internet]. 2018 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Jan 8];9(4). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6315612/. [CrossRef]

- Hastie E, Cataldi M, Marriott I, Grdzelishvili VZ. Understanding and altering cell tropism of vesicular stomatitis virus. Virus Res. 2013 Sep;176(1–2):16–32. [CrossRef]

- Drolet BS, Campbell CL, Stuart MA, Wilson WC. Vector competence of Culicoides sonorensis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) for vesicular stomatitis virus. J Med Entomol. 2005 May;42(3):409–18.

- McGregor BL, Rozo-Lopez P, Davis TM, Drolet BS. Detection of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Indiana from Insects Collected during the 2020 Outbreak in Kansas, USA. Pathog (Basel, Switzerland) [Internet]. 2021 Sep 2;10(9):1126. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34578160. [CrossRef]

- Arboleda JJ, Valbuena RM, Nancy N, VelÃ!`squez JI, Rodas JD, LondoÃ\pmo AF, et al. Respuesta inmune humoral de una vacuna comercial contra la estomatitis vesicular en cerdos. Rev Colomb Ciencias Pecu [Internet]. 2005;18:115–21. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0120-06902005000200002&nrm=iso.

- Mead DG, Ramberg FB, Besselsen DG, Maré CJ. Transmission of vesicular stomatitis virus from infected to noninfected black flies co-feeding on nonviremic deer mice. Science. 2000 Jan;287(5452):485–7. [CrossRef]

- Timoney P. Vesicular stomatitis. Vet Rec. 2016 Jul;179(5):119–20.

- Letchworth GJ, Rodriguez LL, Del cbarrera J. Vesicular stomatitis. Vet J. 1999 May;157(3):239–60.

- World Organization for Animal Health (OIE). Vesicular Stomatitis: Aetiology, Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Prevention and Control References [Internet]. OIE Scientific And Technical Department, editor. 2013. Available from: https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Animal_Health_in_the_World/docs/pdf/Disease_cards/VESICULAR_STOMATITIS.pdf.

- Salinas MT, De La Torre EJ, Moreno PK, Vaca AA, Maldonado RA. A Spatio-temporal distribution analysis of vesicular stomatitis outbreak in Ecuador, 2018. Bionatura [Internet]. 2021; Available from: https://www.revistabionatura.com/2021.06.02.19.html. [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda L, Malirat V, Bergmann IE, Mantilla A, Rosendo do Nascimiento E. Rapid diagnosis of vesicular stomatitis virus in Ecuador by the use of polymerase chain reaction. Vet Microbiol. 2007; Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/bjm/a/4BmZTPy7htjsLLdkc9vxX7g/?lang=en. [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de Sanidad Animal (OIE). Estomatitis Vesicular [Internet]. 2021. Report No.: 3.1.23. Available from: https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/esp/Health_standards/tahm/3.01.23_VESICULAR_STOMATITIS.pdf.

- Tamura K. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition-transversion and G+C-content biases. Mol Biol Evol [Internet]. 1992 Jul 1;9(4):678–87. [CrossRef]

- Pauszek SJ, Rodriguez LL. Full-length genome analysis of vesicular stomatitis New Jersey virus strains representing the phylogenetic and geographic diversity of the virus. Arch Virol. 2012 Nov;157(11):2247–51. [CrossRef]

- Fowler VL, King DJ, Howson ELA, Madi M, Pauszek SJ, Rodriguez LL, et al. Genome Sequences of Nine Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Isolates from South America. Genome Announc. 2016 Apr;4(2). [CrossRef]

- Palinski R, Pauszek S, Burruss ND, Savoy H, Pelzel-McCluskey A, Arzt J, et al. Full Genomic Sequencing of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Isolates from the 2004–2006 US Outbreaks Reveals Associations of Viral Genetics to Environmental Variables. Vol. 50, Proceedings. 2020.

- Koster L., Killian M. Direct submission Diagnostic Virology Laboratory, National Veterinary Services Laboratories, Ames Iowa [Internet]. Diagnostic Virology Laboratory, United States Department of Agriculture. 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MW760857.1.

- Rainwater-Lovett K, Pauszek SJ, Kelley WN, Rodriguez LL. Molecular epidemiology of vesicular stomatitis New Jersey virus from the 2004-2005 US outbreak indicates a common origin with Mexican strains. J Gen Virol. 2007 Jul;88(Pt 7):2042–51. [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Salinas L, Pauszek SJ, Zarate S, Basurto-Alcantara FJ, Verdugo-Rodriguez A, Perez AM, et al. Phylogeographic characteristics of vesicular stomatitis New Jersey viruses circulating in Mexico from 2005 to 2011 and their relationship to epidemics in the United States. Virology. 2014 Jan;449:17–24. [CrossRef]

- Bilsel PA, Rowe JE, Fitch WM, Nichol ST. Phosphoprotein and nucleocapsid protein evolution of vesicular stomatitis virus New Jersey. J Virol. 1990 Jun;64(6):2498–504. [CrossRef]

- Morozov I, Davis AS, Ellsworth S, Trujillo JD, McDowell C, Shivanna V, et al. Comparative evaluation of pathogenicity of three isolates of vesicular stomatitis virus (Indiana serotype) in pigs. J Gen Virol. 2019 Nov;100(11):1478–90. [CrossRef]

- Pauszek SJ, Barrera JDC, Goldberg T, Allende R, Rodriguez LL. Genetic and antigenic relationships of vesicular stomatitis viruses from South America. Arch Virol. 2011 Nov;156(11):1961–8. [CrossRef]

- Cargnelutti JF, Olinda RG, Maia LA, de Aguiar GMN, Neto EGM, Simões SVD, et al. Outbreaks of Vesicular stomatitis Alagoas virus in horses and cattle in northeastern Brazil. J Vet Diagnostic Investig Off Publ Am Assoc Vet Lab Diagnosticians, Inc. 2014 Nov;26(6):788–94. [CrossRef]

- Nichol ST, Rowe JE, Fitch WM. Punctuated equilibrium and positive Darwinian evolution in vesicular stomatitis virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Nov;90(22):10424–8. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across. Molecular Biology and Evolution; 2018. p. 1547–9. [CrossRef]

- Rambaut A. FigTree 1.4.4 [Internet]. Edinburgh: Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburg; 2018. p. 1. Rambaut A. FigTree 1.4.4 [Internet]. Edinburgh: Available from: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/.

- Leight J, Bryant D. PopART: Full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods [Internet]. Methods in Ecology and Evolution; 2015. Available from: http://popart.otago.ac.nz/.

- Clement M, Posada D, Crandall KA. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol Ecol. 2000 Oct;9(10):1657–9. [CrossRef]

- Elias E, McVey DS, Peters D, Derner JD, Pelzel-McCluskey A, Schrader TS, et al. Contributions of Hydrology to Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Emergence in the Western USA. Ecosystems [Internet]. 2019;22(2):416–33. [CrossRef]

- Young KI, Valdez F, Vaquera C, Campos C, Zhou L, Vessels HK, et al. Surveillance along the Rio Grande during the 2020 Vesicular Stomatitis Outbreak Reveals Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of and Viral RNA Detection in Black Flies. Pathog (Basel, Switzerland) [Internet]. 2021 Oct 1;10(10):1264. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34684213. [CrossRef]

- Agrocalidad. Dirección de Vigilancia Zoosanitaria [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 25]. Available from: https://www.agrocalidad.gob.ec/direccion-de-vigilancia-zoosanitaria-3/.

- Aguirre AA, McLean RG, Cook RS, Quan TJ. Serologic survey for selected arboviruses and other potential pathogens in wildlife from Mexico. J Wildl Dis. 1992 Jul;28(3):435–42. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez AE, Jiménez C, Castro L, Rodríguez L. Serological survey of small mammals in a vesicular stomatitis virus enzootic area. J Wildl Dis. 1996 Apr;32(2):274–9. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez AE, Vargas Herrera F, Salman M, Herrero M V. Survey of small rodents and hematophagous flies in three sentinel farms in a Costa Rican vesicular stomatitis endemic region. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;916:453–63. [CrossRef]

- Migné CV, Moutailler S, Attoui H. Strategies for Assessing Arbovirus Genetic Variability in Vectors and/or Mammals. Pathogens; 2020;9(11). [CrossRef]

- INEC. Encuesta de Superficie y Producción Agropecuaria Continua (ESPAC) 2018 [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/Estadisticas_agropecuarias/espac/espac-2018/Presentacion de principales resultados.pdf.

- Mead DG, Gray EW, Noblet R, Murphy MD, Howerth EW, Stallknecht DE. Biological Transmission of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (New Jersey Serotype) by Simulium vittatum (Diptera: Simuliidae) to Domestic Swine (Sus scrofa) . J Med Entomol. 2004 Jan;41(1):78–82. [CrossRef]

- FERRIS DH, HANSON RP, DICKE RJ, ROBERTS RH. Experimental transmission of vesicular stomatitis virus by Diptera. J Infect Dis. 1955;96(2):184–92. [CrossRef]

- Rozo-Lopez P, Londono-Renteria B, Drolet BS. Venereal Transmission of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus by Culicoides sonorensis Midges. Vol. 9, Pathogens. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Tesh RB, Chaniotis BN, Johnson KM. Vesicular stomatitis virus (Indiana serotype): transovarial transmission by phlebotomine sandflies. Science. 1972 Mar;175(4029):1477–9. [CrossRef]

- Comer JA, Tesh RB, Modi GB, Corn JL, Nettles VF. Vesicular stomatitis virus, New Jersey serotype: replication in and transmission by Lutzomyia shannoni (Diptera: Psychodidae). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990 May;42(5):483–90. [CrossRef]

- Nichol ST. Genetic diversity of enzootic isolates of vesicular stomatitis virus New Jersey. J Virol [Internet]. 1988 Feb;62(2):572–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2891861. [CrossRef]

- Calisher CH, Gutierrez VE, Francy DB, Alava AA, Muth DJ, Lazuick JS. Identification of Hitherto Unrecognized Arboviruses from Ecuador: Members of Serogroups B, C, Bunyamwera, Patois, and Minatitlan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32(4):877–85. [CrossRef]

- Alfonzo D, Grillet ME, Liria J, Navarro J-C, Weaver SC, Barrera R. Ecological characterization of the aquatic habitats of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in enzootic foci of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus in western Venezuela. J Med Entomol. 2005 May;42(3):278–84.

- Méndez W, Liria J, Navarro J-C, García CZ, Freier JE, Salas R, et al. Spatial Dispersion of Adult Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in a Sylvatic Focus of Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis Virus. J Med Entomol [Internet]. 2001 Nov 1;38(6):813–21. [CrossRef]

- Weaver SC, Ferro C, Barrera R, Boshell J, Navarro J-C. Venezuelan equine encephalitis. Annu Rev Entomol. 2004;49:141–74.

- Webb PA, McLean RG, Smith GC, Ellenberger JH, Francy DB, Walton TE, et al. Epizootic vesicular stomatitis in Colorado, 1982: some observations on the possible role of wildlife populations in an enzootic maintenance cycle. J Wildl Dis. 1987 Apr;23(2):192–8. [CrossRef]

- Mesquita LP, Diaz MH, Howerth EW, Stallknecht DE, Noblet R, Gray EW, et al. Pathogenesis of Vesicular Stomatitis New Jersey Virus Infection in Deer Mice ( Peromyscus maniculatus) Transmitted by Black Flies ( Simulium vittatum). Vet Pathol. 2017 Jan;54(1):74–81. [CrossRef]

- House JA, House C, Dubourget P, Lombard M. Protective immunity in cattle vaccinated with a commercial scale, inactivated, bivalent vesicular stomatitis vaccine. Vaccine. 2003;21(17-18):1932-7. [CrossRef]

- Combe M, Sanjuán R. Variation in RNA virus mutation rates across host cells. PLoS Pathog. 2014 Jan;10(1):e1003855. [CrossRef]

- Cheng C, Holyoak M, Xu L, Li J, Liu W, Stenseth NC, Zhang Z. Host and geographic barriers shape the competition, coexistence, and extinction patterns of influenza A (H1N1) viruses. Ecol Evol. 2022 Mar 21;12(3):e8732. [CrossRef]

- Peck DE, Reeves WK, Pelzel-McCluskey AM, Derner JD, Drolet B, Cohnstaedt LW, Swanson D, McVey DS, Rodriguez LL, Peters DPC. Management Strategies for Reducing the Risk of Equines Contracting Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV) in the Western United States. J Equine Vet Sci. 2020 Jul;90:103026. [CrossRef]

- Grubaugh ND, Weger-Lucarelli J, Murrieta RA, Fauver JR, Garcia-Luna SM, Prasad AN, Black Iv WC, Ebel GD.

- Genetic drift during systemic arbovirus infection of mosquito vectors leads to decreased relative fitness during.

- host switching. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(4):481–92.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).