1. Introduction

Mosquito-borne arboviruses represent a substantial and growing public health challenge in tropical and subtropical regions, with dengue (DENV), Zika (ZIKV), and chikungunya (CHIKV) inflicting a significant burden of morbidity and economic loss [

6,

7]. These pathogens, transmitted predominantly by the

Aedes aegypti mosquito in urban settings, share vectors and present with similar initial clinical symptoms, complicating differential diagnosis, surveillance, and public health responses [

8].

Ecuador’s unique geography, which spans coastal, Andean, and Amazonian regions, creates diverse ecological niches that are highly conducive to arboviral transmission [

1]. The country’s epidemiological history is marked by the sequential introduction of these three major arboviruses, providing a valuable natural experiment for studying their transmission dynamics and interactions. A critical factor influencing this dynamic is the nation’s exposure to recurrent El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events. These climatic cycles are known to alter temperature and precipitation patterns, which in turn significantly impact

Aedes vector density and distribution, often leading to surges in arboviral disease incidence [

4].

Dengue re-established endemic transmission in Ecuador in the late 1980s, initially concentrating in coastal provinces before expanding inland to higher-altitude and Amazonian areas [

1]. This expansion suggests vector adaptation and increasing climate suitability in previously non-endemic regions. The more recent and explosive introductions of chikungunya (2014-2015) and Zika (2015-2016) occurred during their pandemic spread across the Americas, creating an unprecedented scenario of the co-circulation of three distinct arboviruses [

2,

3]. This co-circulation raises critical questions about potential interactions, such as immunological cross-reactivity between flaviviruses (Dengue and Zika), viral interference, and competition within the mosquito vector.

Furthermore, the global COVID-19 pandemic starting in 2020 introduced another layer of complexity. Health systems globally were overwhelmed, potentially leading to under-surveillance and misdiagnosis of arboviral diseases due to overlapping symptoms and shifted public health priorities.

Despite the clear public health threat, comprehensive long-term analyses of these three arboviruses in Ecuador are scarce. This study aims to fill this gap by analyzing their temporal incidence patterns from 1988 to 2024. We characterize the epidemiological timeline, identify epidemic cycles and their association with major climatic events, document the sequence of viral emergence, and explore temporal associations that suggest epidemiological interactions, all within the context of recent public health disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

We performed a longitudinal observational study using aggregated epidemiological data of reported cases for dengue, severe dengue, Zika, and chikungunya in Ecuador from 1988 to 2024. The data were sourced from the national surveillance system of Ecuador’s Ministry of Public Health (MSP). The dataset comprises annual counts of laboratory-confirmed and clinically diagnosed cases, based on standardized definitions from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the World Health Organization (WHO). Annual incidence rates per 100,000 inhabitants were computed using population projections from Ecuador’s National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

A comprehensive time series analysis was conducted using R software (version 4.2.1). The analytical approach encompassed: (1) Descriptive time series analysis to visualize annual incidence rates and absolute case numbers; (2) Epidemic threshold definition using a five-year moving average to identify epidemic years; (3) Trend analysis to identify secular trends and irregular components; (4) Correlation analysis to examine associations between the incidence rates of each virus pair; and (5) Change-point detection to identify significant shifts in the time series, particularly following new viral introductions.

2.3. Geographical, Environmental, and Contextual Analysis

Where data permitted, national data were stratified into Coastal, Andean, and Amazonian regions to assess differential transmission patterns. For key epidemic years, we collected data on major El Niño/La Niña events from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for qualitative assessment of climatic influence. We also contextualized the 2020-2022 period by considering the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surveillance activities and healthcare-seeking behaviors.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study used anonymized, aggregated public health surveillance data. As such, it was exempt from institutional review board approval as it does not constitute human subjects research.

3. Results

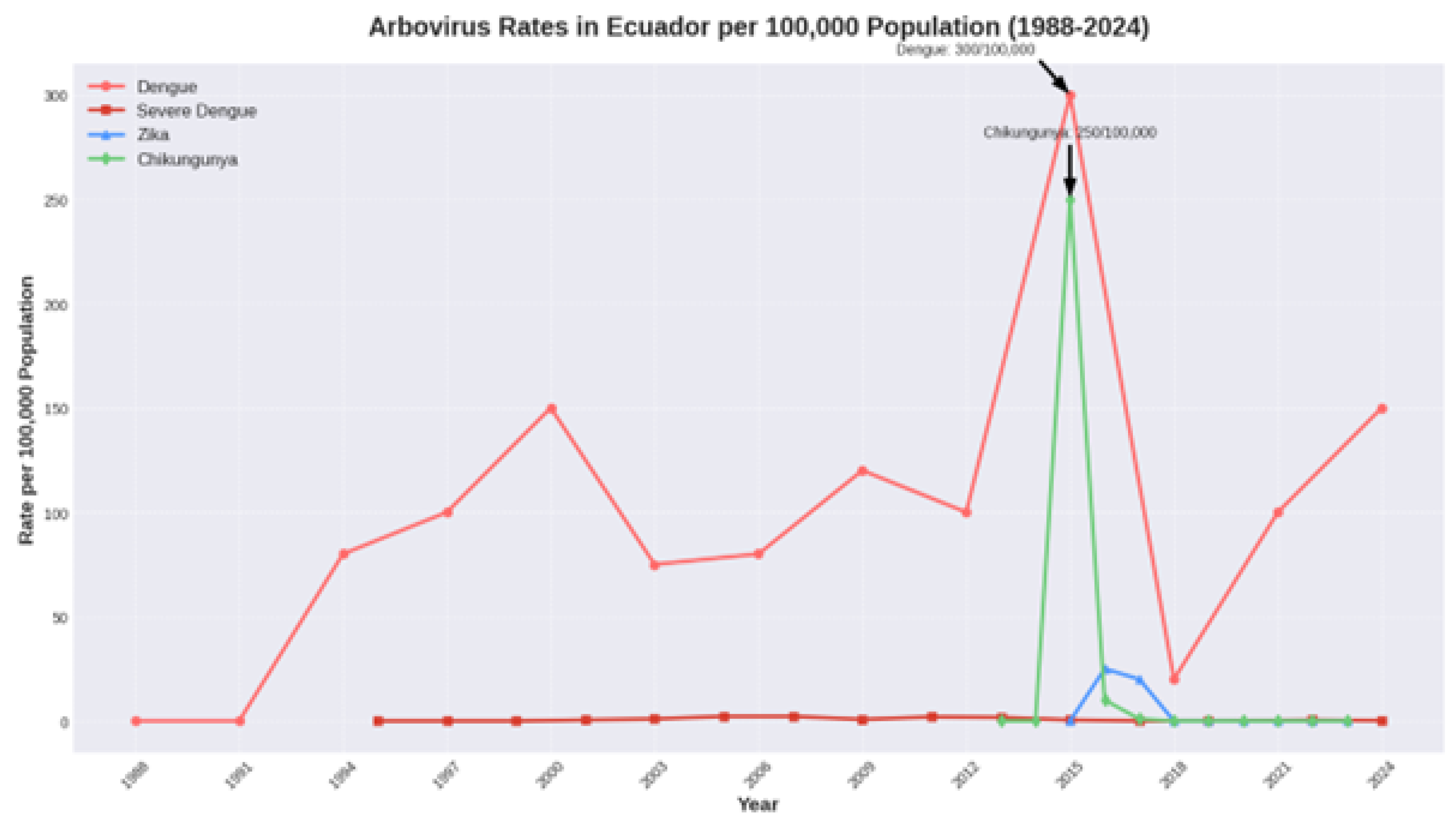

3.1. The Endemic-Epidemic Nature of Dengue

Dengue has demonstrated a persistent presence in Ecuador, with recurrent epidemic cycles. Major peaks were recorded in **1994** ( 10,000 cases), **2000** ( 23,000 cases), and a new significant peak in **2024** ( 23,000 cases). The most significant outbreak occurred in **2015**, with a historic peak of approximately **42,000 cases** (incidence rate of 300 per 100,000). These cycles appear to occur every 6-9 years and are often associated with climatic shifts. A consistent geographic expansion from coastal provinces toward the interior Andean and Amazonian regions has been observed over the last two decades.

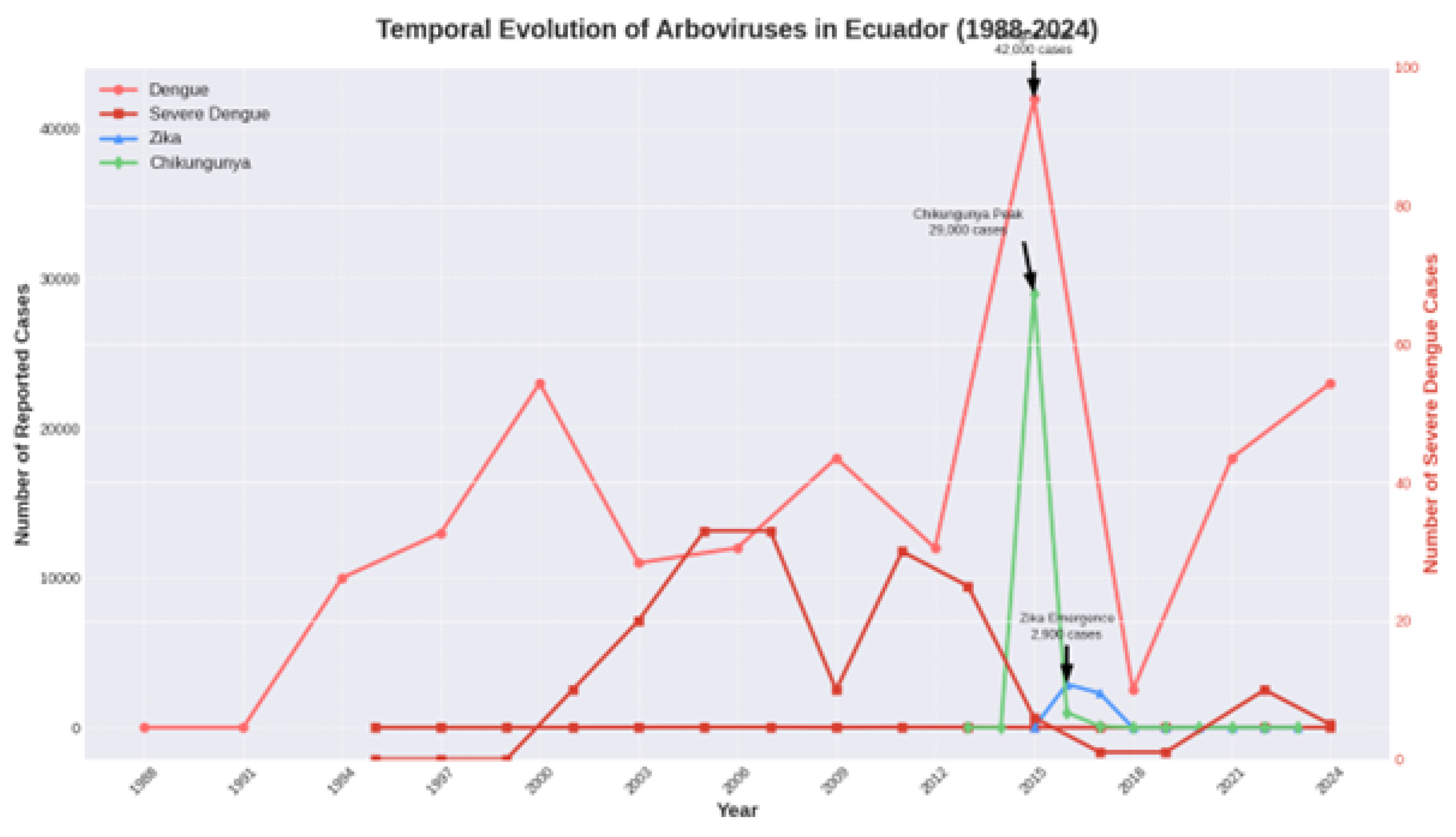

3.2. Decline of Severe Dengue

Cases of severe dengue have been reported since 2001. While total dengue cases have surged periodically, reported cases of severe dengue have shown a proportional decline in recent years. For instance, during the 2024 peak of 23,000 dengue cases, only about 5 severe cases were reported, a stark contrast to previous epidemics.

3.3. Explosive Emergence and Disappearance of Chikungunya and Zika

Chikungunya and Zika exhibited an "explosion and disappearance" pattern. Chikungunya emerged dramatically in **2015** with approximately **29,000 cases** (incidence rate of 250 per 100,000). Zika followed in **2016** with a smaller but significant outbreak of approximately **2,900 cases**. After these initial waves, reported cases for both viruses plummeted to sporadic or near-zero levels from 2018 onwards.

Figure 1.

Arbovirus rates per 100,000 population in Ecuador (1988–2024). The graph shows the endemic-epidemic cycles of Dengue, with major peaks in 1994, 2000, 2015, and 2024. It also illustrates the explosive but transient epidemics of Chikungunya (2015) and Zika (2016).

Figure 1.

Arbovirus rates per 100,000 population in Ecuador (1988–2024). The graph shows the endemic-epidemic cycles of Dengue, with major peaks in 1994, 2000, 2015, and 2024. It also illustrates the explosive but transient epidemics of Chikungunya (2015) and Zika (2016).

3.4. Patterns of Temporal Association and Displacement

A clear chronological series of events emerges from the data:

Sequential Introduction: Dengue established endemicity, followed by the epidemic emergence of Chikungunya (2015) and then Zika (2016).

Peak Coincidence and Displacement: The year 2015 was exceptional, marking the convergence of the largest dengue epidemic and the massive chikungunya outbreak, coinciding with a strong El Niño event. The subsequent emergence of Zika in 2016 coincided with a significant drop in both dengue and chikungunya cases.

Post-Emergence Decline: After 2017, both Zika and chikungunya cases drastically decreased, while dengue transmission persisted, leading to a new epidemic peak in 2024.

Inverse Relationship in Dengue Severity: The decreasing trend in severe dengue notifications contrasts sharply with the persistence and recent peaks in total dengue incidence.

Figure 2.

Temporal evolution of total reported cases of Arboviruses in Ecuador (1988-2024), showing total Dengue cases (primary y-axis) and Severe Dengue cases (secondary y-axis). The figure highlights the divergence between rising total dengue cases and declining severe dengue cases in recent years.

Figure 2.

Temporal evolution of total reported cases of Arboviruses in Ecuador (1988-2024), showing total Dengue cases (primary y-axis) and Severe Dengue cases (secondary y-axis). The figure highlights the divergence between rising total dengue cases and declining severe dengue cases in recent years.

4. Discussion

The 36-year epidemiological landscape of arboviruses in Ecuador reveals a complex interplay of viral, host, environmental, and societal factors.

4.1. Dengue Persistence and Climatic Forcing

Dengue’s endemicity and cyclical epidemics are characteristic of its transmission dynamics, driven by interactions between population immunity, circulating serotypes, and environmental factors [

4]. The major epidemic peaks, particularly in 1997-98 (data point in 2000 reflects this period’s surge) and 2015-16, align with strong El Niño events. These events increase temperature and rainfall, expanding

Aedes aegypti breeding habitats and accelerating viral replication, thus amplifying transmission. The geographic expansion into the Andean highlands, documented by Katzelnick et al. (2024), is likely a combination of increased human mobility and climate change, which makes higher altitudes more permissive for the vector [

1].

4.2. The “Explosion and Disappearance” of Chikungunya and Zika

The pattern observed for chikungunya and Zika is typical for a novel pathogen introduced into a fully susceptible population. Rapid transmission leads to a build-up of herd immunity, which then suppresses subsequent outbreaks [

2]. The massive scale of these outbreaks was likely amplified by the 2015-2016 El Niño event. Their subsequent disappearance from surveillance data could be due to a combination of high population immunity, a shift in surveillance focus, and diagnostic challenges. However, continued low-level or silent circulation cannot be ruled out.

4.3. Evidence for Viral Interactions

The temporal displacement observed—where the rise of Zika in 2016 coincided with a fall in dengue and chikungunya—strongly suggests epidemiological interactions. Potential mechanisms include:

Cross-Immunity: Prior infection with DENV may provide partial, short-term protection against ZIKV, or vice-versa, a phenomenon documented in other regions. This immunological interaction at the population level could influence the epidemic trajectory of each virus.

Vector Competition: Co-infection in Aedes mosquitoes can sometimes lead to viral interference, where one virus suppresses the replication of another, potentially altering transmission efficiency.

Public Health Response: The intense vector control campaigns launched during the chikungunya and Zika emergencies would have indiscriminately reduced

Aedes populations, thereby temporarily interrupting dengue transmission as well [

5].

4.4. The Paradox of Declining Severe Dengue

The decreasing proportion of severe dengue cases is a significant and positive trend. This could be multifactorial: (1) Improved Clinical Management as healthcare systems gain experience; (2) Changes in Circulating Serotypes, with less virulent strains predominating; or (3) Immunological Modulation, where prior exposure to ZIKV might modulate the immune response to a subsequent DENV infection, reducing the risk of severe disease. This last hypothesis is an area of active research and could explain the trend observed post-2016.

4.5. The Confounding Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The 2020-2022 period presents a challenge for interpretation. The global focus on COVID-19 likely led to significant underreporting of arboviruses due to strained healthcare capacity, redirection of laboratory resources, and patients avoiding hospitals. Conversely, lockdowns may have reduced human-vector contact. The resurgence of dengue in 2023-2024 may represent a true increase in transmission, amplified by a potential build-up of susceptible individuals and a relaxation of vector control during the pandemic years.

5. Conclusions

This 36-year analysis reveals that the epidemiology of arboviruses in Ecuador is dynamic and shaped by a cascade of events. Dengue has established itself as a persistent endemic-epidemic threat, with its cycles strongly influenced by climatic phenomena like El Niño. The introductions of chikungunya and Zika were explosive but transient, altering the epidemiological landscape and suggesting powerful interactions between co-circulating viruses.

Our findings highlight the urgent need for an integrated, "syndromic" surveillance approach that monitors febrile illnesses and can differentiate between multiple pathogens. Control strategies must be adaptive, anticipating the cyclical nature of dengue epidemics and preparing for the potential re-emergence of Zika and chikungunya. Understanding the interplay between climate, viral interactions, and human factors is paramount for developing effective public health strategies to mitigate the ongoing threat of arboviral diseases in Ecuador and the wider region.

6. Patents

This section is not applicable to this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D.S. and C.A.R.; methodology, J.D.S.; software, E.C.C.; validation, J.A.S. and C.B.C.; formal analysis, J.D.S.; investigation, all authors; data curation, E.C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.S.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, J.A.S.; supervision, C.B.C.; project administration, J.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The aggregated datasets used during the current study are available from Ecuador’s Ministry of Public Health upon reasonable request. Processed datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador for providing access to the national epidemiological data and to the Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica for its support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| DENV |

Dengue virus |

| ZIKV |

Zika virus |

| CHIKV |

Chikungunya virus |

| MSP |

Ministerio de Salud Pública (Ecuador) |

| PAHO |

Pan American Health Organization |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| INEC |

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (Ecuador) |

| ENSO |

El Niño-Southern Oscillation |

References

- Katzelnick, L.C.; Quentin, E.; Colston, S.; et al. Increasing transmission of dengue virus across ecologically diverse regions of Ecuador and associated risk factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2024, 18, e0011408. [CrossRef]

- Loor Frank, L.D.; Mendoza Rodríguez, M.C.; Fuentes Sánchez, E.T. Arbovirus en el Ecuador: epidemiología, diagnóstico, manifestaciones clínicas. MQRInvestigar 2023, 7, 2929–2947.

- Ochoa Asanza, J.A. Factores que influyen en la vigilancia epidemiologica eficiente del zika en el ecuador. Dominio de las Ciencias 2018, 4, 494–514.

- Sippy, R.; Herrera, D.; Gaus, D.; et al. Seasonal patterns of dengue fever in rural Ecuador: 2009–2016. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13, e0007360. [CrossRef]

- Talbot, B.; Sander, B.; Cevallos, V.; et al. Determinants of Aedes mosquito density as an indicator of arbovirus transmission risk. Parasit Vectors 2021, 14, 484. [CrossRef]

- Hotez, P.J.; Bottazzi, M.E.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Ault, S.K.; Periago, M.R. The neglected tropical diseases of Latin America and the Caribbean: a review of disease burden and distribution and a roadmap for control and elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2008, 2, e300. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Villamil-Gómez, W.E.; Franco-Paredes, C. The arboviral burden of disease caused by co-circulation and co-infection of dengue, chikungunya and Zika in the Americas. Travel Med Infect Dis 2016, 14, 177–179. [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Gubler, D.J.; Weaver, S.C.; Monath, T.P.; Heymann, D.L.; Scott, T.W. Epidemic arboviral diseases: priorities for research and public health. Lancet Infect Dis 2017, 17, e101–e110. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).