1. Introduction

Dengue, a mosquito-borne viral infection, remains a critical public health issue globally, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions where the environmental conditions favor the survival and reproduction of mosquito vectors, primarily

Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus [

1,

2,

3]. The island nation of São Tomé and Príncipe, situated in the Gulf of Guinea, is no exception to this trend [

4,

5]. It’s warm, humid climate and abundant rainfall create ideal breeding grounds for these mosquitoes, resulting in recurrent dengue outbreaks that pose significant threats to the health and well-being of its population [

4,

6,

7].

The cyclical nature of dengue outbreaks in this region highlights the complex interplay of environmental, biological, and social factors that contribute to the disease's persistence. These outbreaks strain the healthcare system, leading to increased hospitalizations, a surge in healthcare costs, and a significant burden on public health infrastructure [

8]. The population, especially vulnerable groups such as children, the elderly, and those with pre-existing health conditions, faces heightened risks during these outbreaks, underscoring the need for effective prevention and control measures [

9].

The impact the Aedes mosquito plays a central role in the transmission of dengue in São Tomé and Príncipe, with environmental conditions, urbanization, and infrastructure challenges contributing to the spread of the disease. The impact was significant 2022, with the majority of larval breeding discovered in used tires, water storage containers, and discarded items, creating ideal environments for mosquito population growth and increasing the risk of dengue outbreaks [

10].

According to Kamgang [

10], the first dengue outbreak in Sao Tome and Principe was reported in 2022 when a suspected dengue case was reported at a hospital in São Tomé and Príncipe on 11 April, from 2022 to 2024, multiple cases has been reported. However, several studies have been conducted to investigate this outbreak. One of such is a study conducted by World Health Organization (WHO) to investigate the annual trends of dengue in 2022. The result of the study revealed that there was a rapid growth in dengue cases in 2022 from 1 to above 103 cases. At that time, the WHO stated that there is no specific treatment for dengue; however it was advised that a timely detection of cases, identifying any warning signs of severe dengue, and appropriate case management are key elements of care to prevent patient deaths due to dengue [

5].

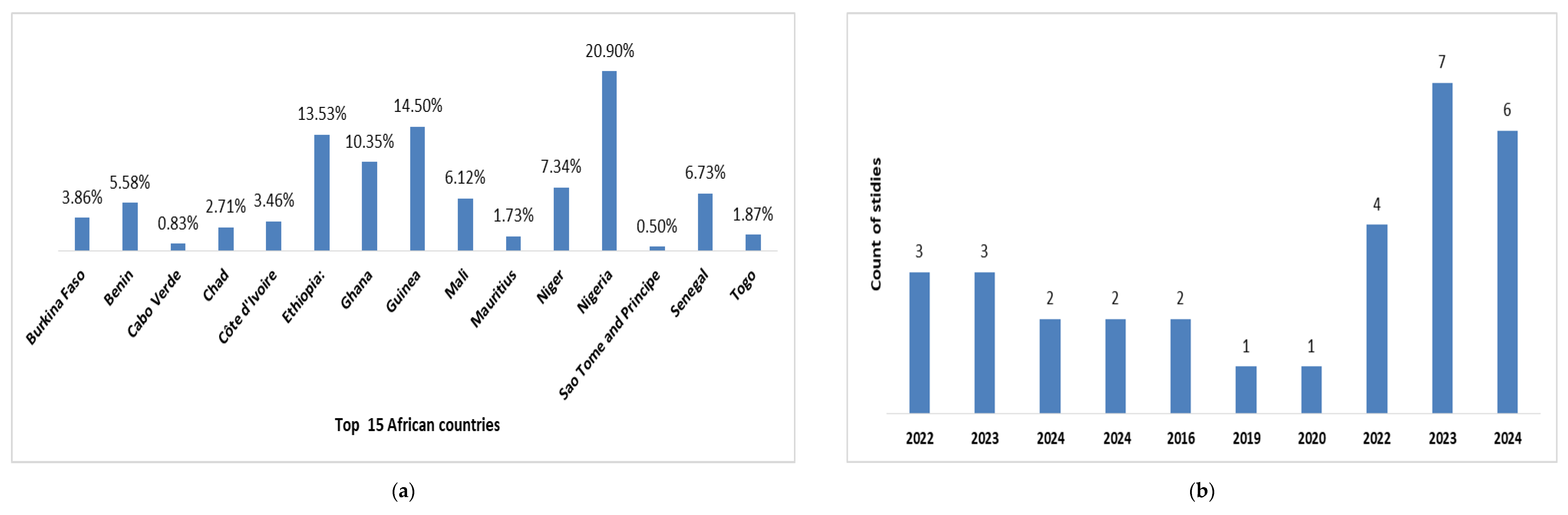

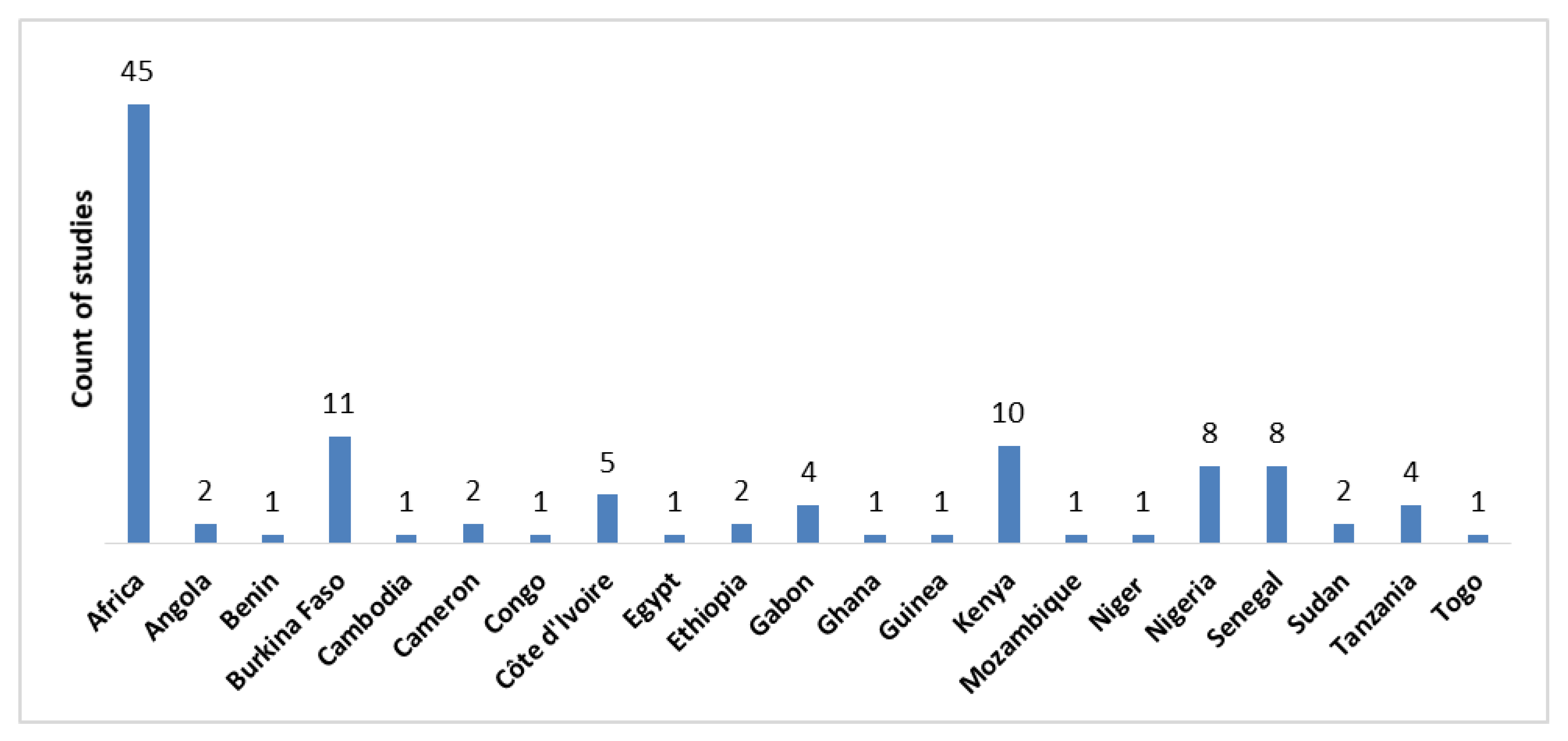

Existing studies on dengue cases in São Tomé and Príncipe have primarily focused on isolated outbreaks or short time frames, providing valuable but incomplete insights into the dynamics of dengue transmission in the region (

Table 1). A key research gap is the lack of longitudinal studies spanning multiple years that offer a continuous analysis of dengue trends, capture temporal fluctuations in dengue incidence, identify patterns in disease transmission, and assess the impact of interventions over time (

Figure 1 to

Figure 2).

This study aims to address this gap by providing a comprehensive analysis of dengue outbreaks in São Tomé and Príncipe over a three-year period (2022 to 2024). Specifically, the objectives are to: Characterize the demographic profile of dengue cases; Identify temporal and spatial trends in dengue incidence; Examine the role of climatic factors and vector control interventions, and to evaluate the impact of public health measures on dengue outbreak dynamics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A retrospective observational study design and mixed-methods approach were adopted to investigate the epidemiological dynamics and trends of dengue outbreaks in São Tomé and Príncipe from 2022 to 2024. The retrospective component involved analyzing existing records from 2022 to 2024, including health records, epidemiological data, environmental factors, and public health interventions. This approach facilitates the identification of trends, patterns, and associations over time, providing valuable insights into the progression of dengue outbreaks. The strength of this design lies in its capability to allow analysis of real-world data from a broad population, enhancing the generalizability of the findings and offering historical insights into epidemiological trends [

20]. To complement and enhance the findings from the retrospective analysis, a Mixed Methods Design was integrated, combining quantitative and qualitative research approaches. The quantitative component involve statistical and geospatial analysis of the retrospective data to uncover trends, incidence rates, and risk factors. The qualitative component, on the other hand, include interviews with public health officials, healthcare providers, and community members, along with in-depth case studies of specific outbreaks [

21].

Integration of these two methodologies leverages their complementary strengths. The retrospective analysis provides a data-driven foundation, while the mixed methods approach enriches this foundation with contextual and narrative insights. By cross-verifying quantitative trends with qualitative experiences, the study enhances the validity and reliability of its findings. This design made it possible to conduct a comprehensive examination of historical data and current trends while achieving robust results. Also, it enabled the integration of quantitative data, such as infection rates, demographics, and geographic distribution with qualitative insights from healthcare providers, patients, and public health officials

2.2. Geographical Study Area

São Tomé and Príncipe (

Figure 3) is a small island nation located in the Gulf of Guinea, off the western coast of Central Africa, with coordinates approximately 0.1864° N latitude and 6.6131° E longitude. Comprising the volcanic islands of São Tomé and Príncipe, along with several smaller islets, the country features rugged terrain with São Tomé's Pico de São Tomé rising to 2,024 meters (6,640 feet) above sea level. It has a tropical rainforest climate with high temperatures ranging from 23°C to 30°C (73°F to 86°F) and high humidity, experiencing two rainy seasons from October to May and a dry season from June to September with about 225,000 population [

22].

2.3. Sample Population

The study population includes all reported dengue cases in São Tomé and Príncipe during the study period (2022-2024). This encompasses both laboratory-confirmed and clinically suspected cases, as recorded by the Ministry of Health and other relevant health authorities. By analyzing these cases, the study aimed to capture the full spectrum of dengue's impact on the population.

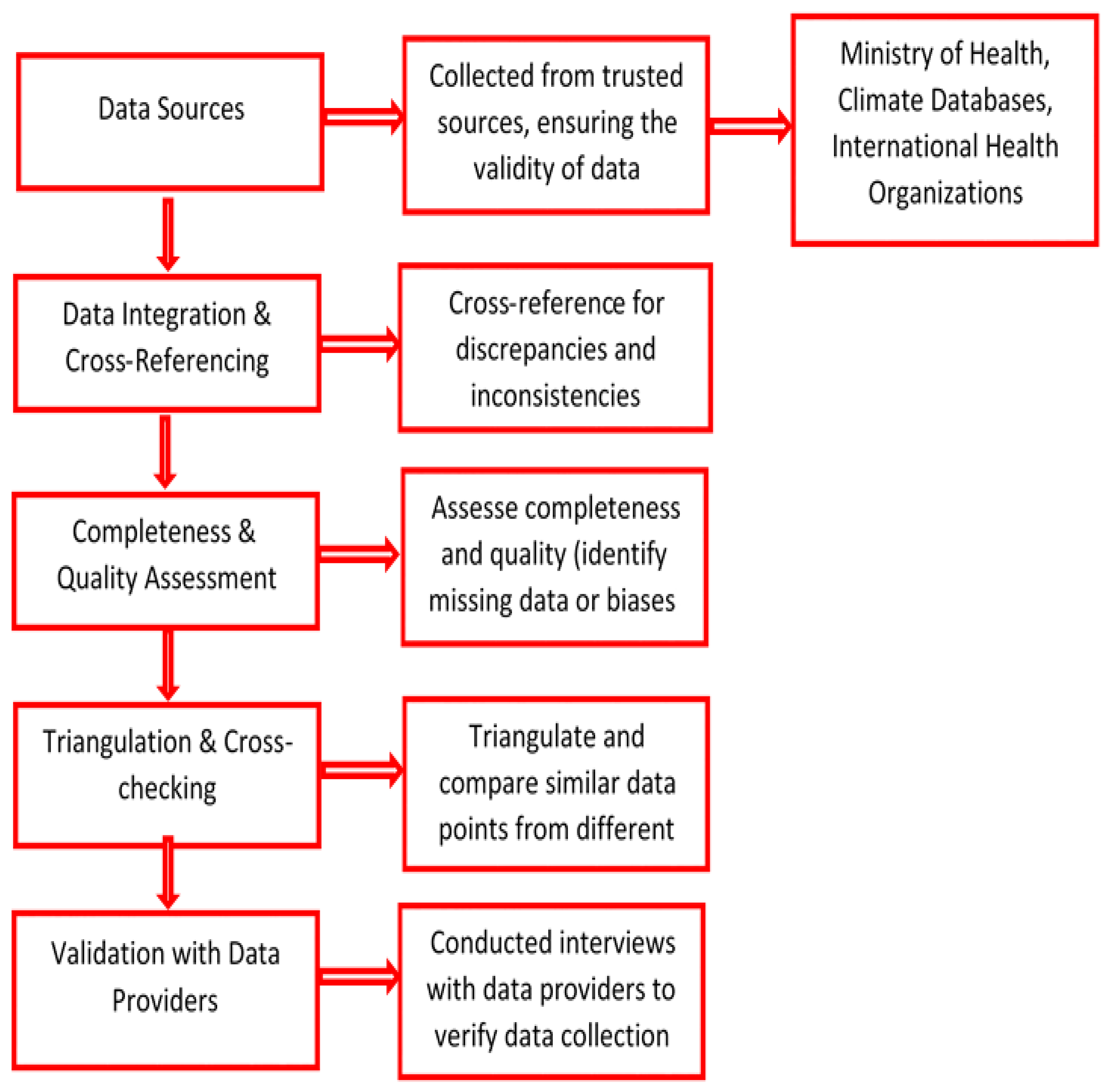

2.4. Data Sources

Historical data were gathered from several database and for various repositories to ensure a comprehensive coverage of data and accuracy. Data such as the epidemiological data were obtained from the Ministry of Health records, which include case line lists and laboratory-confirmed cases. These records provided detailed information on the number of dengue cases, patient demographics, and clinical outcomes. A retrieval of Intervention data from Dengue Bulletins and Situation Reports provided by local health authorities. These documents offer insights into the timing and types of vector control initiatives and other public health interventions (

Figure 4).

2.5. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis and spatial distribution were conducted on the reported dengue cases based on region with focus on major outbreaks during the study period. A descriptive statistics to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of dengue cases:

1) Attack rate or incidence per 100,000 population (equation 1) [

23];

2) Incidence rates by age group (equation 2) [

24];

3) Proportion of hospitalized and severe cases (equation 3–4);

4) Case Fatality Rate (CFR) (equation 5) [

25];

5) Distribution of dengue cases and severe dengue by region.

Multiple linear regression analysis explored the associations between climatic factors (rainfall, temperature, humidity) and dengue incidence to identify the impact of climatic conditions on dengue transmission. The assumption of multiple linear regression was examined to strengthen the adoption of this model tested at α = 0.05 [

26].34Also, a time Series Analysis to identify trends in dengue incidence, the epidemiological curves showing reported cases, CFR of severe dengue by week and year, and the impact of vector control initiatives and other public health interventions on dengue incidence. This analysis will help in understanding the seasonal and annual trends in dengue epidemiology. Geographic Information Systems (QGIS version 3.16.3) software was used to identify hotspot areas of dengue transmission. Spatial distribution of dengue virus serotypes and reported cases by region with a focus on major outbreaks during the study period.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The study adheres to ethical standards to ensure the integrity and confidentiality of the research. Hence, approval from the WHO AFRO Ethics Review Committee (AFR/ERC/2024/09.1) and the Ministry of Health of São Tomé and Príncipe to ensure compliance with ethical guidelines were obtained. Similarly, all patient data were made to be anonymized to protect individual privacy and maintain confidentiality. Necessary permissions was secured from relevant health authorities and data providers to access and use the data.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristic of Dengue Cases

This section details the findings from the analysis of Dengue cases in relation to various factors - presented to illustrate key trends and insights. The average age of dengue cases from 2022 to 2024 (3yrs time) is 30.2 years, indicating that on average, individuals in their early thirties were most commonly affected (

Table 2). However, the median age is slightly lower at 28 years, suggesting that half of the cases were younger than 28, which points to a slight skew in the distribution towards younger individuals.

The mode, or the most frequently occurring age, is 15 years, highlighting that adolescents might be particularly vulnerable to dengue in this period. The standard deviation of 18.2 years reflects a wide age variation among the cases, suggesting that dengue affected a broad age range, from children to older adults.

3.2. Mortality Profiles

The average age of individuals who died is higher, with a mean age of 40.2 years (±17.9), compared to 30.1 years (±18.2) for those who survived (

Table 3). The median age of death is 44 years, concentrated in the 40-49 age group, while those who did not die had a median age of 28, with the 20-29 age group most affected. The age range of fatalities spans from 1 to 60 years, while non-fatal cases range more broadly from 0 to 90 years.

Additionally, the sex ratio differs significantly, with a lower ratio of males to females (0.5) among the fatalities, indicating that more women were affected, while the ratio is closer to parity (0.92) for non-fatal cases.

3.3. Age Distribution of Dengue Cases

However, the most affected age group was the 10–19-year-old group, which accounted for 20.9% (264 cases) of the total dengue cases, followed closely by the 20–29 years group with 19.1% (242 cases), and the 30–39 years group with 18.8% (238 cases). Together, these three groups (10–39 years) represent more than half of the total cases, indicating that adolescents and young adults are particularly vulnerable to dengue during the period under consideration. On the other hand, age groups above 50 years show a lower percentage of cases (

Table 4).

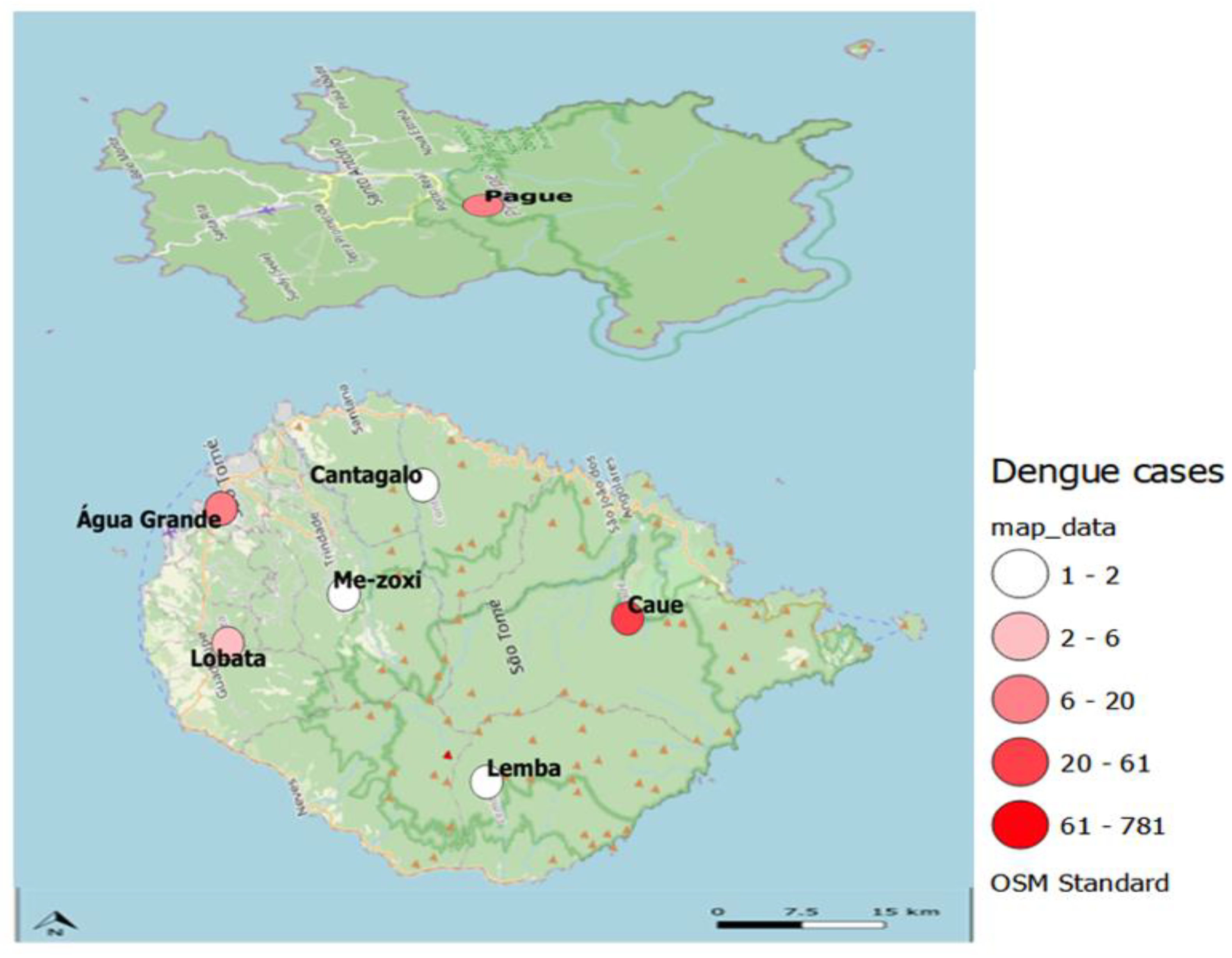

Of the total dengue cases, females account for 52.2% (660 cases), while males represent 47.8% (604 cases).The district of Água Grande accounts for the vast majority of cases, with 862 cases representing 68.2% of the total. This indicates that dengue is heavily concentrated in this area, making it a critical zone for focused public health interventions and control efforts.

Table 5.

Distribution of district in which dengue cases were observed.

Table 5.

Distribution of district in which dengue cases were observed.

| District |

Dengue cases(N) |

Percentage (%) |

| Cantagalo |

50 |

3.96 |

| Caué |

23 |

1.82 |

| Lembá |

22 |

1.74 |

| Lobata |

106 |

8.39 |

| Mézochi |

187 |

14.8 |

| Pagué |

14 |

1.11 |

| Água Grande |

862 |

68.2 |

Most cases, 1198 (94.8%), were symptomatic, indicating that the overwhelming majority of individuals with dengue presented with clear symptoms of the disease. Sixty-two cases (4.91%) underwent screening procedures.

Time to Recovery: The mean time from notification to recovery is 6.65 days with a standard deviation of 4.06 days, indicating that recovery typically takes about a week on average, though there is considerable variability. The median time is 7 days. The maximum time to recovery is 15 days, showing a broad range in recovery times (

Table 6).

The distribution of dengue cases by possible source of infection and associated alerts reveals that hospitals play a crucial role in the detection and management of dengue cases (

Table 7). The Alerta HAM (Hospital) category accounts for the majority of cases, with 69.9% of the total reported cases coming from hospitals, indicating their centrality in identifying and treating dengue. Additionally, 17.8% of cases were detected in community health areas (Alerta Área de Saúde), showcasing the importance of community-based health surveillance. This distribution underscores the critical role hospitals and community health areas play in dengue case surveillance, while smaller facilities and events contribute a smaller share of detections.

The prevalence of various dengue symptoms with fever being the most common was reported by 37.05% of the individuals (

Table 8). This is followed by headache (31.52%) and muscle pain (17.31%), which are typical signs of systemic infections, particularly viral illnesses like dengue. Weakness (5.97%) and vomiting (1.84%) are moderately frequent, while retro-orbital pain (0.91%), joint pain (0.78%), and back pain (0.75%) suggest musculoskeletal involvement in some cases. Gastrointestinal symptoms like nausea (0.69%), abdominal pain (0.56%), and diarrhea (0.34%) are less common but still notable. Rash and hemorrhage, each occurring in 0.25% of cases, could point to severe or specific infections such as viral hemorrhagic fevers. Other symptoms, including cough (0.16%), conjunctivitis, and chills (0.12% each), indicate mild respiratory and systemic involvement. There are also rare symptoms, each occurring in 0.03% of individuals, such as vomiting with blood, vaginal bleeding, spine pain, sore throat, and various hemorrhages.

The distribution of recovery status of dengue cases indicates that the vast majority of patients, 98.89%, successfully recovered from the disease (

Table 9). A small portion of the cases resulted in death, accounting for 0.87%, while 0.24% of the cases are still classified as active or ongoing. This high recovery rate suggests effective treatment and management of dengue cases, though the presence of active cases and fatalities highlights the ongoing need for medical attention and intervention in severe cases.

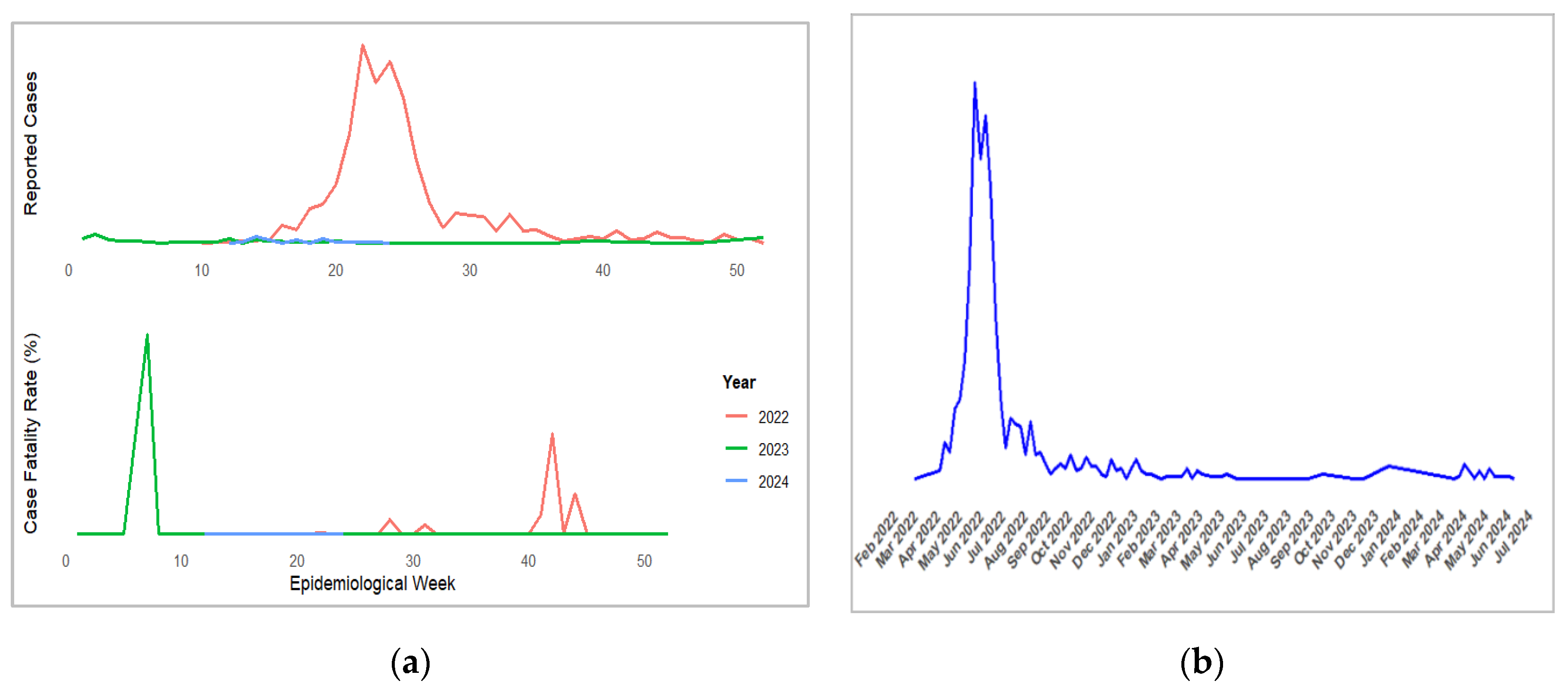

The yearly and cumulative case fatality rate (CFR) for dengue from 2022 to 2024 shows a variable trend (

Table 10). In 2022, the CFR was 0.69%, which increased significantly to 1.33% in 2023, indicating a rise in the proportion of fatal cases. However, in 2024, there were no recorded fatalities, resulting in a 0% CFR for that year. The cumulative CFR for the entire period from 2022 to 2024 stands at 0.71%, reflecting the overall lethality of the disease over the three years. This trend highlights variations in dengue case outcomes across the years.

Table 11 illustrates the Monthly Case Fatality Rate (CFR) for dengue from 2022 to 2024. In 2022, CFRs fluctuate, with a notable peak in October at 12%, indicating higher fatality. Other months generally have CFRs of zero or low percentages. In 2023, the data is sparse, with February having a high CFR of 12.5% but zero CFRs for other months. For 2024, no data on fatalities were reported. This variability highlights periods of higher risk and underscores the need for consistent data reporting and targeted interventions during high-risk periods.

3.4. Climatic Factors and Dengue Incidence

Table 12 provides a monthly overview of Dengue cases alongside climatic factors such as average maximum and minimum temperatures, total rainfall, and average wind speed. In May, Dengue cases peak at 258, coinciding with the highest total rainfall of 744 mm and an average maximum temperature of 29.7°C. June follows with the highest number of cases (598) and the highest rainfall (1186 mm). Dengue cases decrease in the subsequent months, with July and August showing lower case numbers and varying climatic conditions. The lowest number of cases occurs in February (8) with minimal rainfall (8 mm) and relatively high average temperatures. Overall, the data suggests a correlation between increased rainfall and higher Dengue cases, while temperature changes have a less consistent impact.

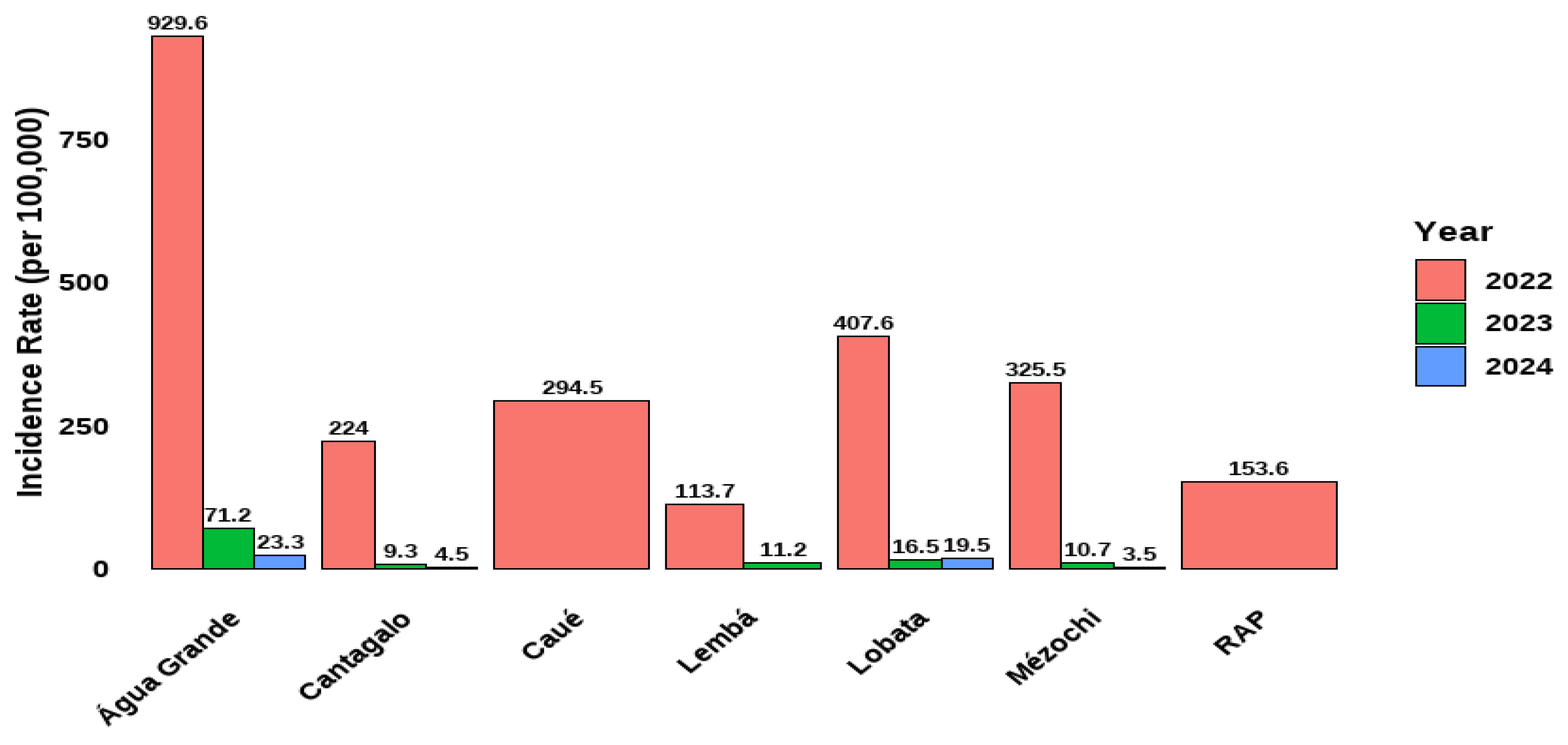

Table 13 presents the yearly overview of Dengue cases and climatic factors from 2022 to 2024. In 2022, Dengue cases are highest at 1161, representing 91.9% of the total cases over the three years, with an annual average incident rate of 349.8. The maximum temperature averages 28.5°C, and total rainfall is 3205 mm, with a wind speed of 11.9 km/h. In 2023, cases drop significantly to 75, making up 5.93% of the total, with a lower annual incident rate of 23.8. The maximum temperature rises to 30.2°C, and rainfall decreases to 159 mm, while wind speed remains relatively constant at 11.1 km/h. By 2024, Dengue cases further decline to 28, representing 2.22% of the total, with an even lower annual incident rate of 12.7. The maximum temperature increases slightly to 31°C, minimum temperature rises to 25.5°C, and rainfall drops significantly to 16 mm, with wind speed increasing to 12 km/h.

3.5. Correlation and Regression Analysis

Table 14 indicates a strong positive correlation between Dengue incidence and rainfall (0.96, p<0.00), suggesting that higher rainfall is associated with increased Dengue cases. Conversely, Dengue incidence shows a weak negative correlation with maximum temperature (-0.31, p < 0.1316) and minimum temperature (-0.23, p<0.261), implying limited impact from temperature variations on Dengue incidence. Wind speed has a minimal effect on Dengue cases (0.02, p<0.929). Rainfall is positively correlated with dengue cases, highlighting its significant role. Maximum temperature negatively correlates with rainfall (-0.37, p>0.07) and wind speed (-0.61, p<0.00), indicating that higher temperatures are associated with lower rainfall and wind speed. Minimum temperature shows weak correlations with both rainfall (-0.30, p<0.15) and wind speed (-0.12, p<0.57), suggesting minor effects.

Table 15 displays the regression coefficients and model summary for predicting dengue cases. The model coefficients reveal that Rainfall has a significant positive effect on Dengue cases (estimate = 0.44568, p < 0.001), with a high t-value of 13.945. In contrast, the coefficients for Intercept, Max Temp, Min Temp, and Wind are not statistically significant, with p-values of 0.493, 0.832, 0.608, and 0.887, respectively. The residual standard error is 38.45, indicating the average deviation of predicted values from actual values. The model's Multiple R-squared value is 0.9201, suggesting that approximately 92% of the variability in Dengue cases is explained by the model. The Adjusted R-squared of 0.9041 accounts for the number of predictors in the model. The F-statistic of 57.57 (p < 1.084e-10) confirms that the model is statistically significant overall. The result indicate the importance of Rainfall in predicting Dengue cases, while other variables show limited impact. The Dengue Equation is presented below.

Figure 5.

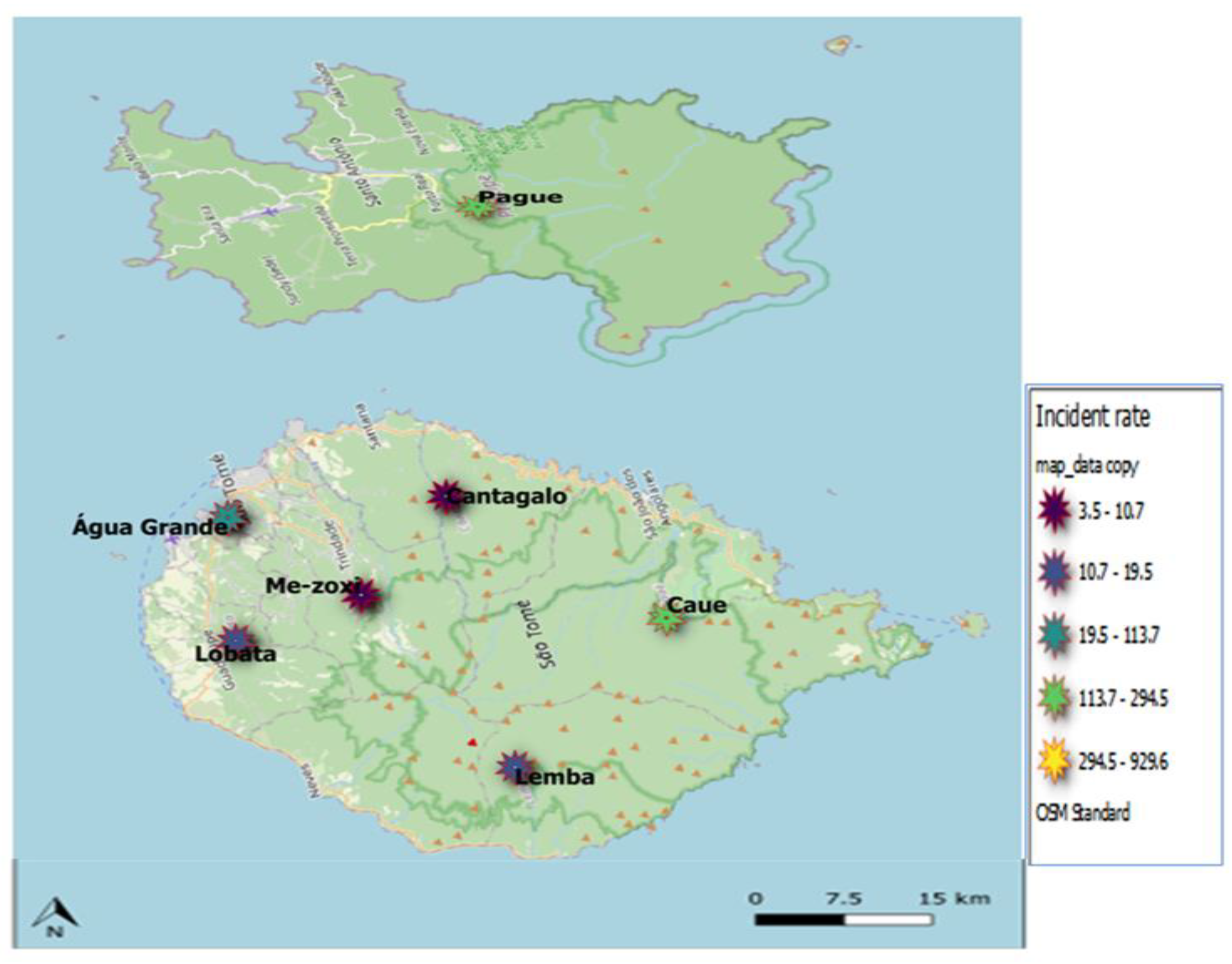

Figure 6: Incidence Rate of Dengue by District and Year.

Figure 5.

Figure 6: Incidence Rate of Dengue by District and Year.

Figure 6.

(a) Reported cases and case fatality rate of dengue by epidemiological week and by year; (b) Trends in epidemiology of dengue disease in from 2022 to 2024.

Figure 6.

(a) Reported cases and case fatality rate of dengue by epidemiological week and by year; (b) Trends in epidemiology of dengue disease in from 2022 to 2024.

Figure 7.

Geospatial Distribution of Dengue Cases in Sao Tome and Principe, 2022–2024.

Figure 7.

Geospatial Distribution of Dengue Cases in Sao Tome and Principe, 2022–2024.

Figure 8.

Geospatial Distribution of Dengue Incident Rate in Sao Tome and Principe, 2022–2024.

Figure 8.

Geospatial Distribution of Dengue Incident Rate in Sao Tome and Principe, 2022–2024.

Table 15 displays the regression coefficients and model summary for predicting dengue cases. The model coefficients reveal that Rainfall has a significant positive effect on Dengue cases (estimate = 0.44568, p < 0.001), with a high t-value of 13.945. In contrast, the coefficients for Intercept, Max Temp, Min Temp, and Wind are not statistically significant, with p-values of 0.493, 0.832, 0.608, and 0.887, respectively. The residual standard error is 38.45, indicating the average deviation of predicted values from actual values. The model's Multiple R-squared value is 0.9201, suggesting that approximately 92% of the variability in Dengue cases is explained by the model. The Adjusted R-squared of 0.9041 accounts for the number of predictors in the model. The F-statistic of 57.57 (p < 1.084e-10) confirms that the model is statistically significant overall. The result indicate the importance of Rainfall in predicting Dengue cases, while other variables show limited impact. The Dengue Equation is presented below.

4. Discussion

Our analysis of dengue cases from 2022 to 2024 reveals important trends in demographics, geographical distribution, environmental influences, and recovery profiles. These insights offer valuable information for shaping public health strategies and tailoring interventions to mitigate the effects of dengue in São Tomé and Príncipe.

One significant finding is that adolescents and young adults, particularly those aged 20-29, were the most affected by dengue in non-fatal cases. This mirrors findings from Lee’s study in Taiwan [

26], which observed a higher seropositivity rate for DENV IgG in late adulthood [

11], suggesting that young adults often contract the virus, but typically recover without severe outcomes due to stronger immune defenses. Our data suggest that the 20–29 age group possesses better immune responses, which may contribute to lower fatality rates. (

Table 2). However, as stated by Kreutmair [

27] immune response and comorbidities may influence mortality risk. The concentration of deaths in the 40–49 age group further supports the idea that middle-aged individuals are at a higher risk of fatal outcomes, potentially due to pre-existing health conditions or diminished immune response over time. In contrast, the most affected age group for non-fatal cases falls in the 20-29 range, indicating that younger individuals are more likely to contract the disease but survive, possibly due to stronger immune defenses [

28].

The fluctuation in the overall case fatality rate (CFR) across the three years is another notable finding. The overall case fatality rate (CFR) fluctuated over the three-year period, with a notable increase in 2023 (1.33%) compared to 2022 (0.69%), before falling to 0% in 2024 (

Table 10). This variation in CFR underscores the need for ongoing continuous monitoring, flexible response strategies and interventions to mitigate fatalities in future outbreaks since dengue outbreaks can vary significantly in intensity from year to year. The geographical concentration of cases in the Água Grande district, which accounted for 68.2% of all reported dengue infections, is particularly concerning. This finding suggests that environmental or social factors unique to this district, such as population density or housing conditions, may contribute to heightened transmission rates. Public health efforts should focus on this district, ensuring that vector control strategies, community education, and access to healthcare resources are intensified in high-risk areas. Additionally, this concentration highlights the need for region-specific interventions rather than a one-size-fits-all approach across São Tomé and Príncipe. (

Table 5).

Our analysis of environmental variables reveals the complex relationship between climate factors and dengue transmission. While heavy rainfall is traditionally linked to an increase in mosquito breeding sites, our data show that rainfall's impact on dengue incidence varied significantly between years. In 2022, an exceptionally high annual rainfall of 3205 mm coincided with the highest dengue incidence rate (349.8). The correlation between rainfall and dengue transmission is well-documented, as stagnant water from heavy rainfall creates ideal breeding grounds for Aedes mosquitoes, which are the primary vectors for dengue.

However, in 2023 and 2024, despite rising temperatures, the marked reduction in rainfall (159 mm in 2023 and 16 mm in 2024) corresponded with a sharp decline in dengue cases [

29].This suggests that while moderate to high rainfall may encourage mosquito breeding, extremely low rainfall can limit mosquito habitat formation, reducing transmission rates. The relationship between temperature and dengue cases also presents a nuanced picture. Dengue cases peaked in cooler months (May, June, and July), where maximum temperatures ranged from 27.3 °C to 29.7 °C. This contrasts with warmer months like February and March, where higher temperatures above 30°C were recorded, yet dengue cases were notably fewer. This implies that while temperature plays a role in mosquito behavior and viral replication, other factors like rainfall and possibly human behaviours during seasonal transitions (e.g., increased water storage) are critical drivers of dengue transmission.

The relatively stable wind speeds across the three years (ranging from 11.1 to 12 km/h) suggest that wind did not play a significant role in influencing dengue transmission during this period. The correlation between heavy rainfall and high dengue incidence aligns with the known impact of rainfall on mosquito breeding sites, as water accumulation creates ideal conditions for the growth of Aedes mosquitoes [

30].Dengue cases peak significantly in May (258 cases), June (598 cases), and July (123 cases), coinciding with periods of higher rainfall. For instance, May and June experienced the highest rainfall amounts (744 mm and 1186 mm, respectively). However, the highest number of dengue cases in May and June corresponds to relatively lower maximum temperatures (ranging from 27.3°C to 29.7°C), compared to warmer months like February and March, which had fewer cases despite maximum temperatures above 30°C [

31].

The recovery profiles of dengue patients provide further insight into the impact of the disease on public health resources. Our data show that the average recovery time for dengue patients is approximately 6.81 days, which aligns with WHO guidelines [

32] for mild cases of dengue. However, the wide standard deviation of 6.84 days points to significant variability in recovery experiences. This variability could be attributed to several factors, including the initial severity of the infection, the presence of comorbid conditions, and the adequacy or timeliness of medical interventions. This highlights the need for differentiated care pathways in the healthcare system, ensuring that patients with more severe presentations or complicating health factors receive more intensive monitoring and support.

The findings of this study reinforce the importance of multifaceted approaches to controlling dengue outbreaks. Targeted interventions in high-incidence areas like Água Grande are essential, focusing on both environmental management (such as controlling mosquito breeding sites during rainy seasons) and improving healthcare infrastructure to handle severe cases, particularly in vulnerable populations like middle-aged adults. Additionally, understanding the complex interplay between environmental factors and dengue transmission can help predict future outbreaks, guiding public health authorities to deploy resources more effectively.

Further research is necessary to explore why dengue cases peak during cooler months and to better understand the role of temperature, human behaviors, and environmental management in controlling the spread of the disease. Moreover, ongoing surveillance is crucial to detect shifts in CFR and to assess the effectiveness of interventions, as evidenced by the fluctuating CFR during this study period. In addition it would be good a national strategic plan that can be reviewed and adapted to improve case management, diagnostic and vector control measures among other preventive measures.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This study was funded by the World Health Organization's Regional Office for Africa, in collaboration with São Tomé and Príncipe's Ministry of Health and the Instituto Nacional de Estadística. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or decision to publish.

Data Availability Statement

All the relevant data generated during this study are included in the manuscript and its supporting information.

Acknowledgments

We express our heartfelt gratitude to the Ministry of Health, São Tomé and Príncipe, for their leadership and commitment to public health. Our thanks also go to the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE), São Tomé e Príncipe, for their essential data support. We acknowledge the World Health Organization, São Tomé and Príncipe, for their technical expertise, and the WHO Regional Office for Africa, Dengue Incident Management Support Team, for their crucial role in managing dengue outbreaks. Together, these stakeholders have significantly contributed to enhancing health resilience in São Tomé and Príncipe. AZ acknowledges support from the Pan-African Network for Rapid Research, Response, Relief and Preparedness for Emerging and Re-Emerging Infections (PANDORA-ID-NET), funded by the EU-EDCTP2–EU Horizon 2020 Framework Programme. AZ is in receipt of a UK NIHR Senior Investigator Award. AZ is also a recipient of the Mahathir Science award and the Pascoal Mocumbi Prize.

References

- Anusha JR, Kim BC, Yu KH, Raj CJ. Electrochemical biosensing of mosquito-borne viral disease, dengue: A review. Biosens Bioelectron. 2019 Oct 1;142:111511. [CrossRef]

- Pooja V. A study of clinical and laboratory parameters of dengue fever with respect to onset of complications in paediatric patients [dissertation]. India: Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences. R: India.

- World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue [Internet]. 2024 Apr 23 [cited 2024 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue.

- Clarence-Smith WG, Seibert G. Sao Tome and Principe. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2024 Jul 25. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/place/Sao-Tome-and-Principe.

- World Health Organization. Dengue - Sao Tome and Principe [Internet]. 2022 May 26 [cited 2024 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON387.

- Ahmed T, Hyder MZ, Liaqat I, Scholz M. Climatic conditions: conventional and nanotechnology-based methods for the control of mosquito vectors causing human health issues. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Aug 30;16(17):3165. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Asgarian TS, Moosa-Kazemi SH, Sedaghat MM. Impact of meteorological parameters on mosquito population abundance and distribution in a former malaria endemic area, central Iran. Heliyon. 2021 Nov 24;7(12). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sarker R, Roknuzzaman ASM, Haque MA, Islam MR, Kabir ER. Upsurge of dengue outbreaks in several WHO regions: public awareness, vector control activities, and international collaborations are key to prevent spread. Health Sci Rep. 2024 Apr 22;7(4). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hu YS, Lo YT, Yang YC, Wang JL. Frailty in older adults with dengue fever. Medicina. 2024;60(4):537. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho E, Vilhete D, Assunção C, Silva A, Vicente J, Cristina A, Vagente C, Costa F, Monteiro C, Pina B. Acute hemorrhagic fever: clinical, epidemiological and laboratory aspects in São Tomé and Príncipe. Adv Infect Dis. 2022 Oct 20;12(4):721-44. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Disease outbreak news; dengue in São Tomé and Príncipe [Internet]. 2022 May 26 [cited 2024 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON387.

- Wickramasooriya S, Mahmood I, Calinescu A, Wooldridge M, Lanzaro G. Exploring the dynamics of gene drive mosquitoes within wild populations using an agent-based simulation. [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 16].

- Perrocheau A, Jephcott F, Asgari-Jirhanden N, Greig J, Peyraud N, Tempowski J. Investigating outbreaks of initially unknown aetiology in complex settings: findings and recommendations from 10 case studies. Int Health. 2023 Sep 1;15(5):537-46. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kormos A, Nazaré L, Dos Santos AA, Lanzaro GC. Practical application of a relationship-based model to engagement for gene-drive vector control programs. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2024 Jun 18;111(2):341-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nolen S, Gormalova N. Genetic engineering in the mosquito war. The New York Times. 2023 Oct 3;D1.

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. São Tomé & Príncipe: worsening dengue outbreak: operational update (MDRST002). Situation report [Internet]. 2023 Mar 31 [cited 2024 Sep 16]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/sao-tome-and-principe/sao-tome-principe-worsening-dengue-outbreak-operational-update-mdrst002.

- Lázaro L, Winter D, Toancha K, Borges A, Gonçalves A, Santos A, Schuldt K. Phylogenomics of dengue virus isolates causing dengue outbreak, São Tomé and Príncipe, 2022. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30(2):384-6. [CrossRef]

- Kamgang B, Acântara J, Tedjou A, Keumeni C, Yougang A, Ancia A, Bigirimana F, Clarke SE, Gil VS, Wondji C. Entomological surveys and insecticide susceptibility profile of Aedes aegypti during the dengue outbreak in Sao Tome and Principe in 2022. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024 Jun 3;18(6):e0011903. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yen TY, Tseng LF, Cheng CF, Trovoada dos Santos MDJ, Carvalho AVDA, Shu PY, Lien JC, Tsai KH. Dengue virus infection in the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;45:308. [CrossRef]

- Setia MS. Methodology series module 1: cohort studies. Indian J Dermatol. 2016 Jan-Feb;61(1):21-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schoonenboom J, Johnson RB. How to construct a mixed methods research design. Kölner Z Soz Sozpsychol. 2017;69(Suppl 2):107-31. Epub 2017 Jul 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Clarence-Smith WG, Seibert G. São Tomé and Príncipe. Encyclopedia Britannica [Internet]. 2024 Jul 25 [cited 2024 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/place/Sao-Tome-and-Principe.

- Pettygrove S. Attack rate. Encyclopedia Britannica [Internet]. 2016 Mar 15 [cited 2024 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/science/attack-rate.

- Inoue K. Formula for estimating incidence of chronic diseases from prevalence, mortality and other indices from survey. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2013 Jun;5(6):243-56.

- Chang CS, Yeh YT, Chien TW, Lin JC, Cheng BW, Kuo SC. The computation of case fatality rate for novel coronavirus (COVID-19) based on Bayes theorem: an observational study. Medicine. 2020 May 22;99(21). [CrossRef]

- Lee YH, Hsieh YC, Chen CJ, Lin TY, Huang YC. Retrospective seroepidemiology study of dengue virus infection in Taiwan. BMC Infect Dis. 2021 Jan 21;21(1):96. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kreutmair S, Kauffmann M, Unger S, Ingelfinger F, Núñez NG, Alberti C, De Feo D, Krishnarajah S, Friebel E, Ulutekin C, Babaei S, Gaborit B, Lutz M, Jurado NP, Malek NP, Göpel S, Rosenberger P, Häberle HA, Ayoub I, Al-Hajj S, Claassen M, Liblau R, Martin-Blondel G, Bitzer M, Roquilly A, Becher B. Preexisting comorbidities shape the immune response associated with severe COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022 Aug;150(2):312-24. Epub 2022 Jun 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ponnappan S, Ponnappan U. Aging and immune function: molecular mechanisms to interventions. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011 Apr 15;14(8):1551-85. Epub 2011 Jan 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu C, Xu J, Wang L. Long-term effects of climate factors on dengue fever over a 40-year period. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1451. [CrossRef]

- Wibawa BSS, Wang YC, Andhikaputra G, Lin YK, Hsieh LHC, Tsai KH. The impact of climate variability on dengue fever risk in Central Java, Indonesia. Climate Serv. 2024;33:100433. [CrossRef]

- Karim MN, Munshi SU, Anwar N, Alam MS. Climatic factors influencing dengue cases in Dhaka city: a model for dengue prediction. Indian J Med Res. 2012 Jul;136(1):32-9. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue. 2024 Apr 23. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue#:~:text=Most%20people%20with%20dengue%20have,last%20for%202%E2%80%937%20days.

- Kamgang B, Acântara J, Tedjou A, Keumeni C, Yougang A, Ancia A, et al. Entomological surveys and insecticide susceptibility profile of Aedes aegypti during the dengue outbreak in Sao Tome and Principe in 2022. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024 Jun 3;18(6). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaya Uyanık G, Güler N. A Study on Multiple Linear Regression Analysis. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2013;106:234–40. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).