Submitted:

17 September 2025

Posted:

19 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

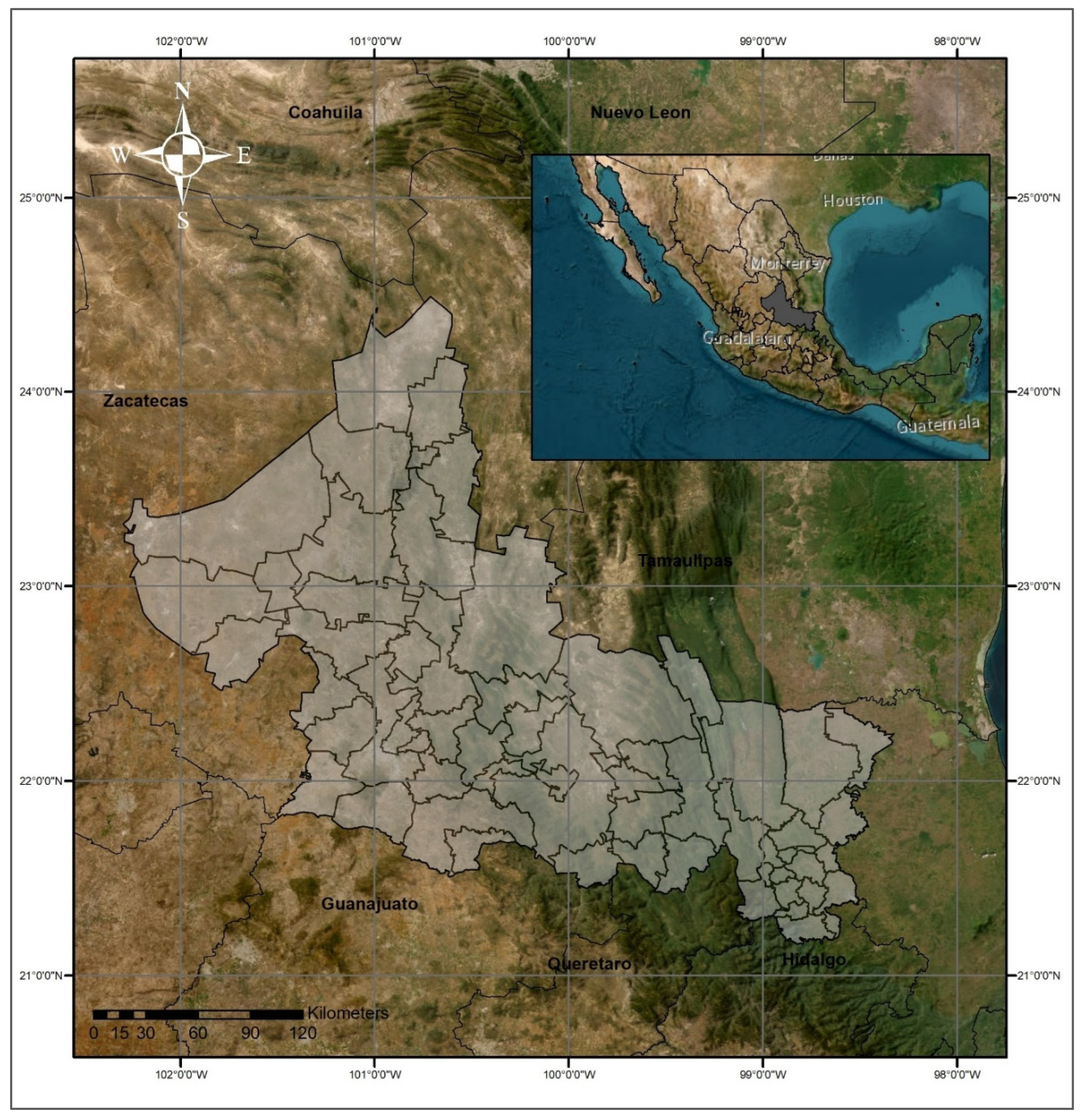

2.1. Study Area

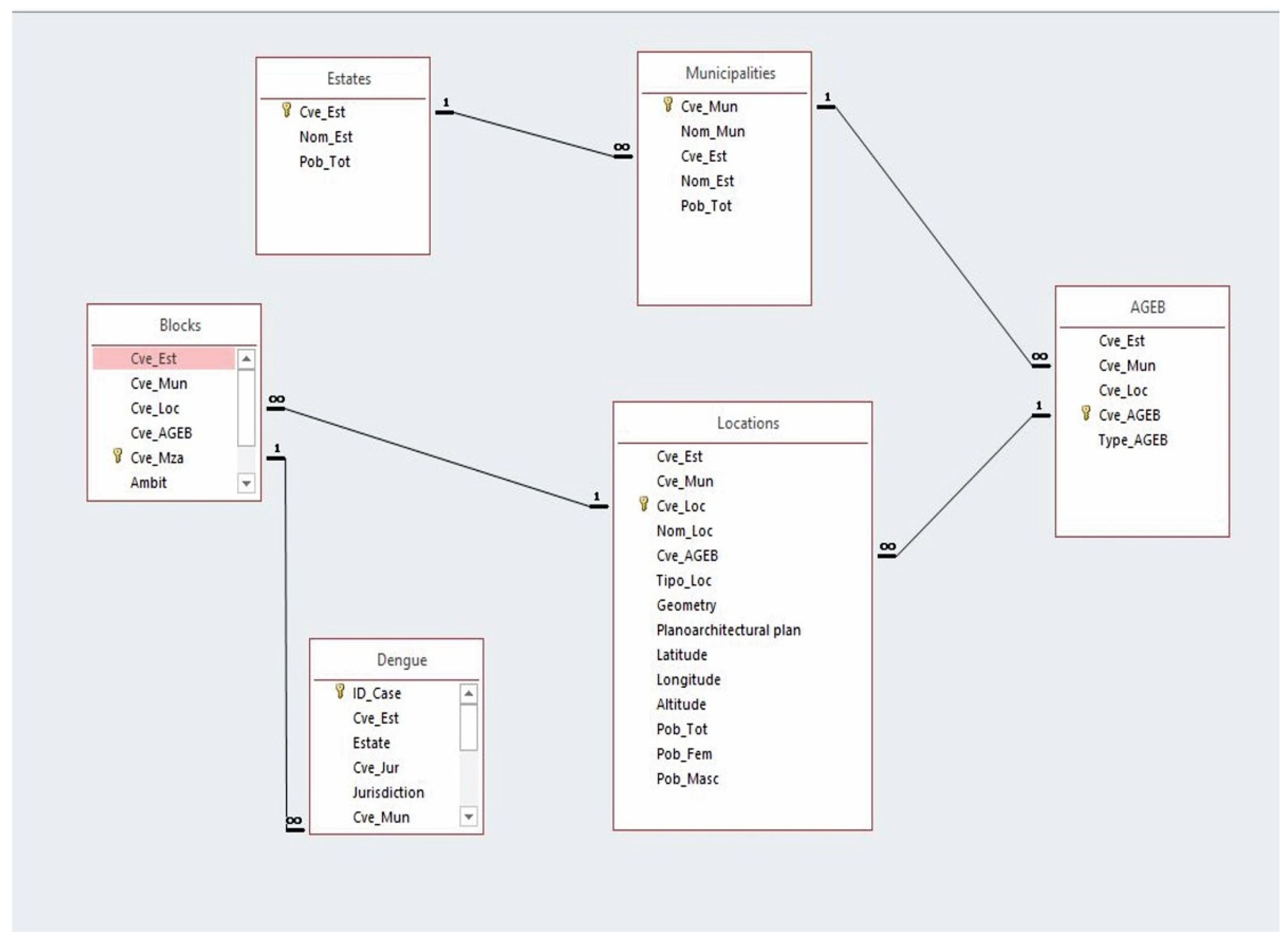

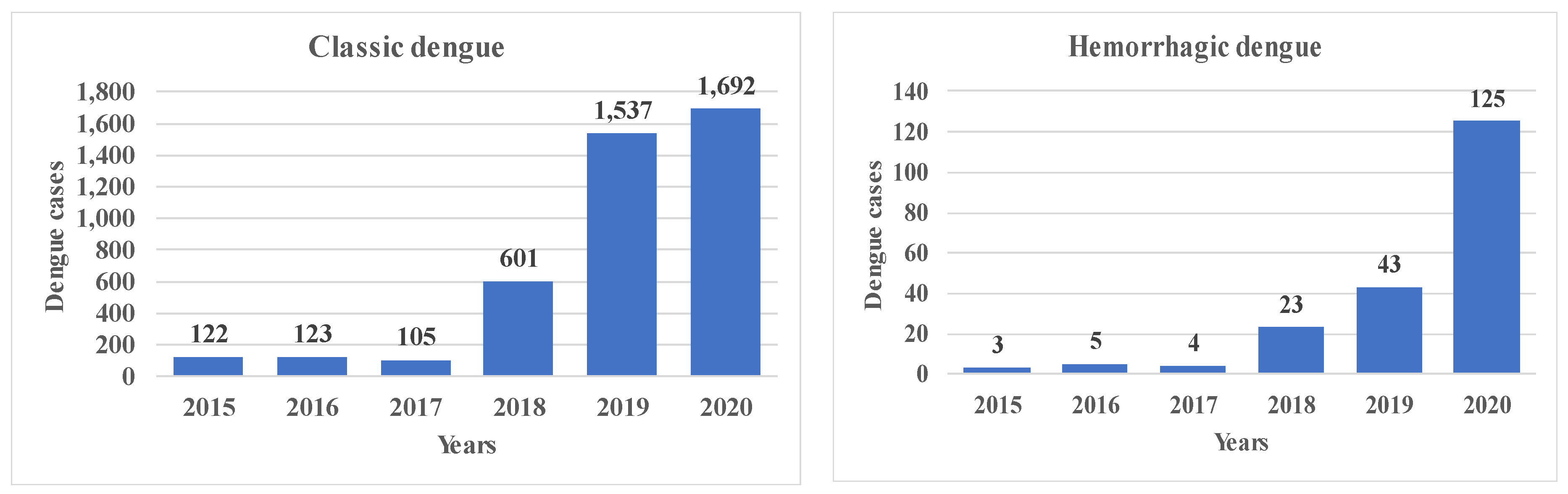

2.2. Available Data

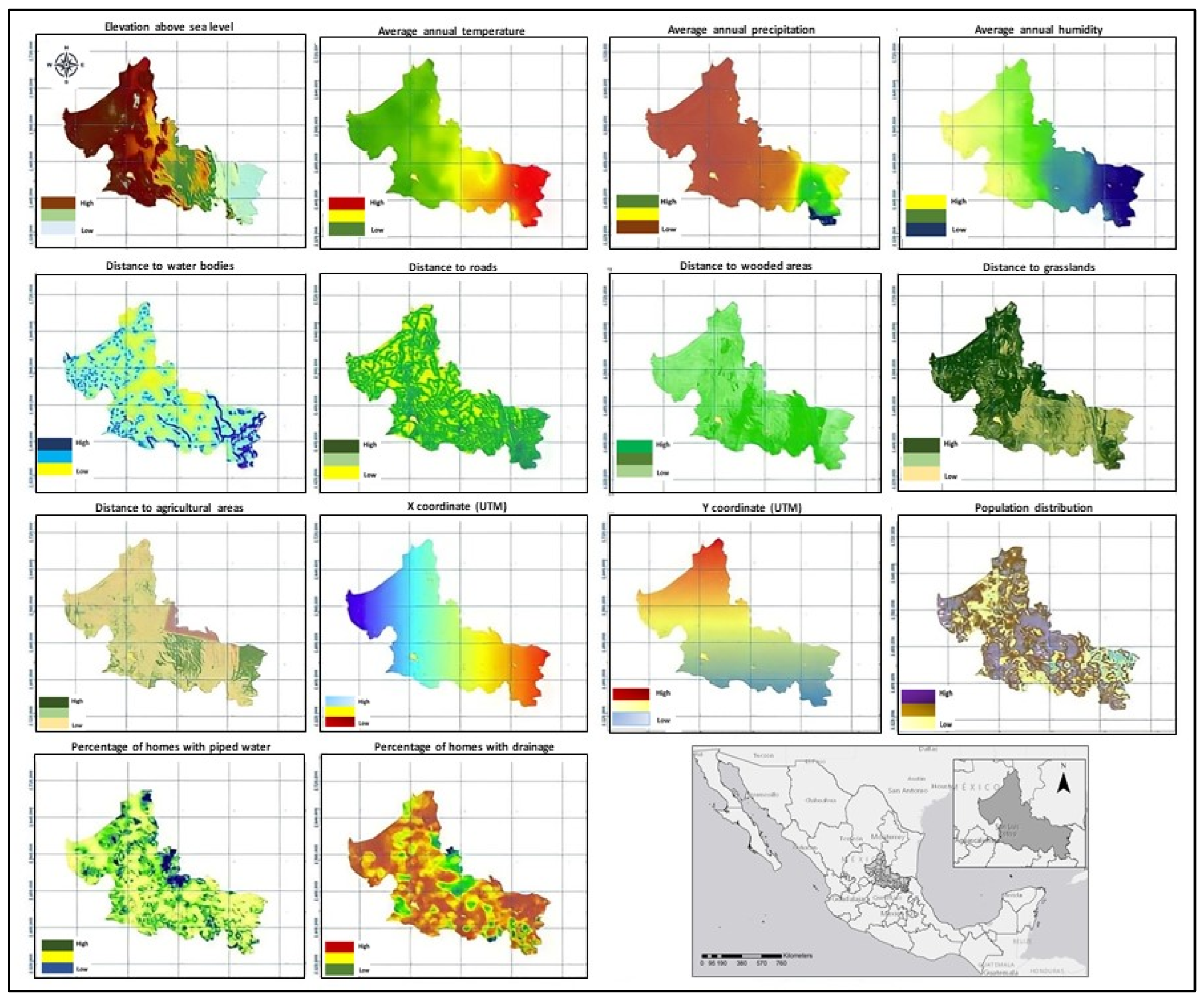

2.3. Variables

3. Methods

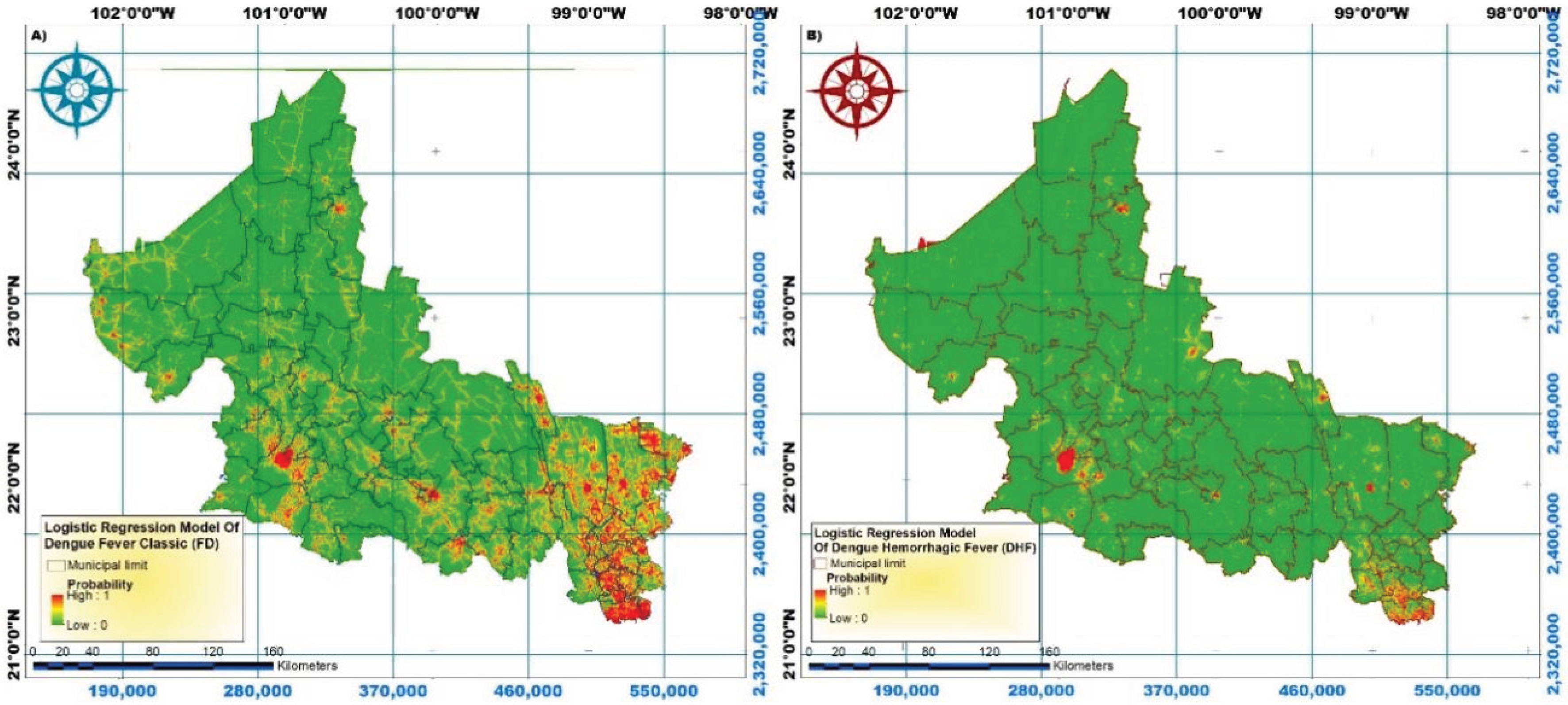

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- OMS (Organización Mundial de la Salud), 2023. Expansión geográfica de los casos de dengue y chikungunya más allá de las áreas históricas de transmisión en la Región de las Américas. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON448#:~:text=El%20total%20de%20casos%20presuntos,119%25%20en%20comparaci%C3%B3n%20con%202021 Consulted in april 2024.

- OMS (Organización Mundial de la Salud). Dengue y dengue grave.2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue#:~:text=Carga%20mundial&text=Seg%C3%BAn%20una%20estimaci%C3%B3n%20basada%20en,se%20manifiestan%20cl%C3%ADnicamente%20 June 2024.

- Secretaria de Salud. Dirección General de Epidemiología. Panorama Epidemiológico de Dengue. Semana Epidemiológica 52 de 2022, 2023. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/789466/Pano_dengue_52_2022.pdf Consulted in march 2024.

- Secretaria de Salud. Dirección General de Epidemiología. Panorama Epidemiológico de Dengue. Semana Epidemiológica 52 de 2023, 2024. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/878786/Pano_dengue_52_2023.pdf Accesado: Consulted in april 2024.

- Man O, Kraay A, Thomas R, Trostle J, Robbins C, Lee GO, et. al. Characterizing dengue transmission in rural areas: A systematic review. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.2023. 17:1-21. [CrossRef]

- ONU (Organización de las Naciones Unidas). El cambio climático empuja el dengue hacia Europa y Sudamérica. 2023. Available online: https://news.un.org/es/story/2023/07/1522897#:~:text=El%20calentamiento%20global%2C%20caracterizado%20por,agencia%20sanitaria%20de%20la%20ONU febrero 2024.

- Menéndez M, Pérez JE, López-Vélez R. Red cooperativa para el estudio de las enfermedades infecciosas importadas por viajeros e inmigrantes. Fase 3: desarrollo e implantación. Editado por: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad.2012. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/promoSaludEquidad/migracionSalud/docs/REDCooperativa_Est_Enfermedades.pdf Consulted in august, 2023.

- Gallo MSL, Ribeiro MCH, Prata-Shimomura AR, Ferreira ATS. Identifying Geographic Dengue Fever Distribution by Modeling Environmental Variables. International Journal of Geoinformatics.2020. 16:39-49.

- Pereira CA. Análise Geoespacial dos casos de Dengue e Sua Relação com Fatores Socioambientais em Bayeux – Pb. Hygeia. Revista Brasileira de Geografia Médica e da Saúde.2017. 13:71-86.

- Zaw W, Lin Z, Ko KJ, Rotejanaprasert C, Pantanilla N, Ebener S, et al. Dengue in Myanmar: Spatiotemporal epidemiology, association with climate and short-term prediction. PLoS Negl Trop Dis.2023. 17:e0011331. [CrossRef]

- Secretaria de Salud. Programa de Acción Específico. Prevención y Control de Dengue 2013-2018. Programa Sectorial de Salud, 2014. Prevención y Control de Dengue. Available online: http://www.cenaprece.salud.gob.mx/descargas/pdf/PAE_PrevencionControlDengue2013_2018.pdf Consulted in august, 2023.

- Para todo México. Estados de México. Estado de San Luis Potosí. Ubicación Geográfica. Información del Estado. 2023. Available online: https://paratodomexico.com/estados-de-mexico/estado-san-luis-potosi/index.html Consulted in february, 2024.

- Secretaría de Salud. Dirección de Salud Pública. Subdirección de Epidemiología. Departamento de Vigilancia Epidemiológica y Urgencias Epidemiológicas. 2021. Unidad de transparencia del organismo público descentralizado de los Servicios de Salud San Luis Potosí INFOMEX.

- INEGI (National Institute of Statistics and Geography - Mexico). 2020. Continuo de Elevaciones Mexicano (CEM). Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/geo2/elevacionesmex/.

- Betanzos-Reyes AF, Rodríguez MH, Romero-Martínez M, Sesma-Medrano E, Rangel-Flores H, Santos-Luna R., et. Al. Association with Aedes spp. abundance and climatological effects.2018. Salud Publica Mex 2018:60:12-20.

- IMTA (The Mexican Institute of Water Technology). Extractor Rápido de Información Climatológica III, v. 1.0. Climatic information available in CD.2016. Jiutepec, Morelos, México. Available online: http://hidrosuperf.imta.mx/sig_eric/.

- Mutucumarana, C., Bodinayake, C., Nagahawatte, A., Devasiri, V., Kurukulasooriya, R., Anuradha T, De Silva AD, Janko, M., Østbye, T, Gubler, D., Woods, C., Reller, M., Nur Athen Mohd Hardy Abdullah, Nazri Che Dom, Siti Aekball Salleh, Hasber Salim, Nopadol Precha. The association between dengue case and climate: A systematic review and meta-analysis. One Health, 2022. 15. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Harris, I, P.D. Jones, T.J. Osborn, D.H. Lister. Updated high-resolution grids of monthly climatic observations – the CRU TS3.10 Dataset. 21 May 2013. [CrossRef]

- Zavaleta J. Kriging: Un Método de Interpolación sobre Datos Dispersos 2010. Available online: http://tikhonov.fciencias.unam.mx/presentaciones/2010sep23.pdf.

- Nakhapakorn K, Tripathi NK. An information value-based analysis of physical and climatic factors affecting dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever incidence. International Journal of Health Geographics.2005. 4:1-13. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Zhao, Z., Li, Z., Li, W., Li, Z., Guo, R., Yuan, Z. Spatiotemporal Transmission Patterns and Determinants of Dengue Fever: A Case Study of Guangzhou, China.2019. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(14), 2486. [CrossRef]

- Khalid B, Ghaffar A. Dengue transmission based on urban environmental gradients in different cities of Pakistan. Int J Biometeorol. Mar;59(3):267-83.2015. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USGS. Sciencia for a changing world.2022. Available online: http://glovis.usgs.gov.

- INEGI (National Institute of Statistics and Geography - Mexico). Geografia y medio ambiente. Marco geoestadístico. 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/mg/.

- Ferrán M. SPSS. SPSS para Windows. Análisis estadístico. Edit Mc Graw Hill. 1a Edición. 2001. Madrid Spain.

- Jeefoo, P., Tripathi, N.K., Souris, M. Spatio - temporal diffussion pattern and hotspot detection of dengue clásico in Chachoengsao Province, Thailand. International Journal of Enviromental Research and Public Health.2011. 8(1). 51-74. [CrossRef]

- Khormi, H.M., Kumar, L.Modeling dengue fever risk based on socioeconomic parameters, nationality and age groups: GIS and remote sensing-based case study. 2011. [CrossRef]

- INEGI. CENSO. Subsistema de Información Demográfica y Social. Censo de Población y Vivienda. 2021. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/#datos_abiertos.

- Oviedo, M.E., Largue, Brito., R., Romero, R., Nicolino, R.R., Fonseca, C.S., Amaral, J.P. Spatial and statistical methodologies to determine the distribution of dengue in Brazilian municipalities and relate incidence with the health vulnerability index. Spatial and Spatio - temporal Epidemiology. 2014. 11(1). 143–151. [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Gobernación. Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal (INAFED). Sistema Nacional de Información Municipal (SNIM). 2020. Available online: http://www.snim.rami.gob.mx/#:~:text=El%20Sistema%20Nacional%20de%20Informaci%C3%B3n,datos%20de%20contacto%20de%20alcaldes.

- Secretaría de Salud. Dirección de Salud Pública. Subdirección de Epidemiología. Departamento de Vigilancia Epidemiológica y Urgencias Epidemiológicas. 2021. Unidad de transparencia del organismo público descentralizado de los Servicios de Salud San Luis Potosí INFOMEX.

- CDC. Centro para el Control y la prevención de Enfermedades Centro Nacional de Enfermedades Infecciosas Zoonóticas. El Dengue en el Mundo.2023. Atlanta, Georgia, EE. UU. ttps://www.cdc.gov/dengue/es/areaswithrisk/around-the.

- SMN. Sistema meteorológico nacional. Información estadística climatológica. Available online: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/climatologia/informacion-climatologica/informacion-estadistica-climatologica Información de Estaciones Climatológicas. 2022.

- Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Análisis Multivariante. Edit PearsonPrentice Hall.5a Edición. 2007. Madrid Spain.

- Meyers, L.S., Gamst, G., and Guarino, A.J., 2006. Applied Multivariate Research: Design and Interpretation. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Lippi CA, Stewart-Ibarra AM, Muñoz AG, Borbor-Cordova MJ, Mejía R, Rivero K, Castillo K, Cárdenas WB, Ryan SJ. The social and spatial ecology of dengue presence and burden during an outbreak in Guayaquil, Ecuador,2012. Int J Environ Res Public Health.2018. 15:827. [CrossRef]

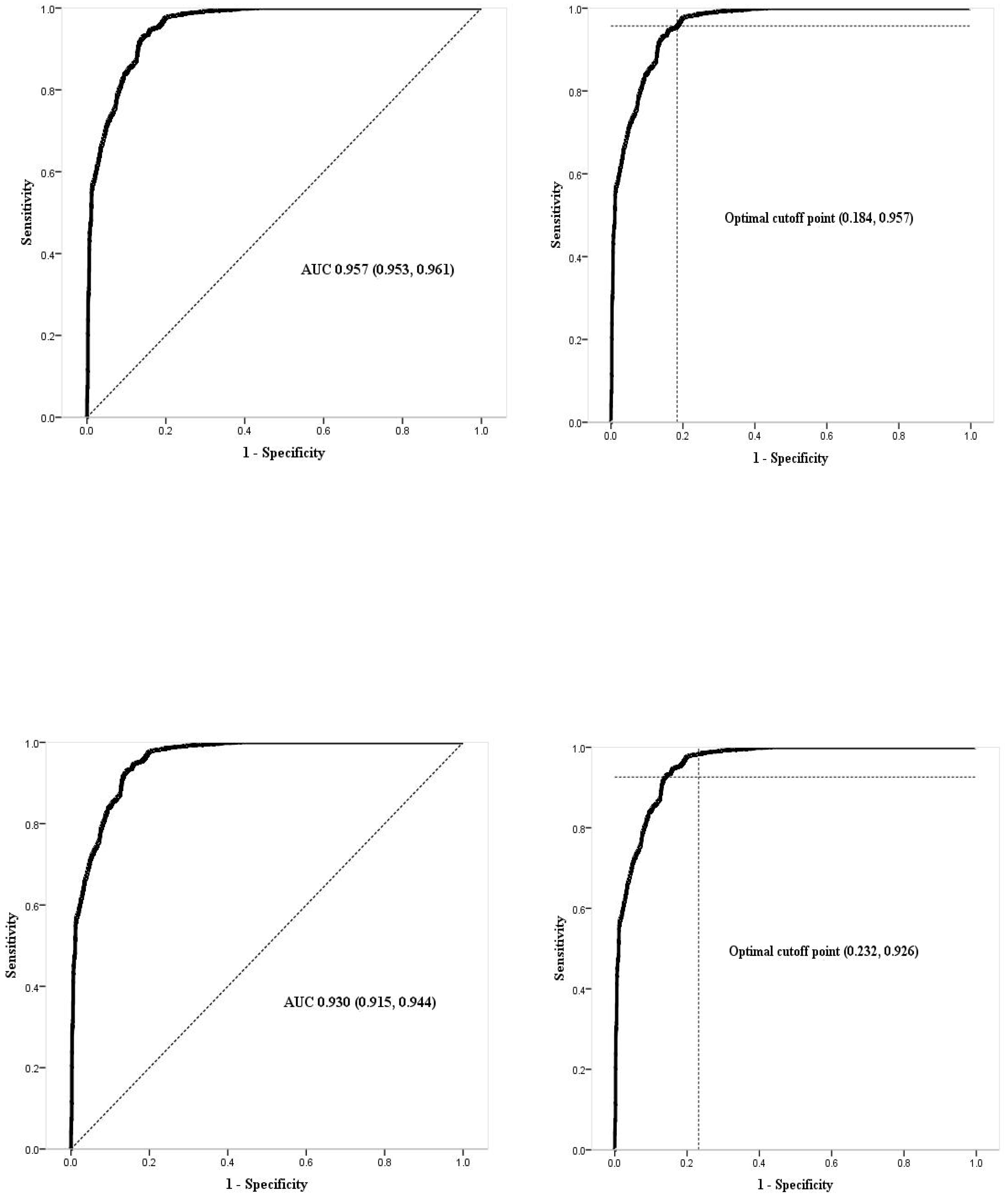

- Martínez Pérez, J. A., Pérez Martín, P. S. La curva ROC. Medicina de Familia. SEMERGEN. 2023. 49(1), artículo 101821. [CrossRef]

- IBM (International Business Machines). SPSS Statistics. Area bajo la curva.2024. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/docs/es/spss-statistics/29.0.0?topic=schemes-area-under-curve Consulted in abril 2024.

- Ferrán M. SPSS. SPSS para Windows. Análisis estadístico. Edit Mc Graw Hill. 1a Edición. 2001. Madrid Spain.

- Triola MF, 2009. Estadística. Décima edición.Pearson Addison Wesley. Pagina 260.

- Sánchez, D., Aguirre, C. A., Sánchez, G., Aguirre, A. I., Soubervielle, C., Reyes, O.Santana-Juárez, M. V. 2019. Modeling spatial pattern of dengue in North Central Mexico using survey data and logistic regression. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 31(7), 872–888. [CrossRef]

- Nakhapakorn K, Tripathi NK. An information value-based analysis of physical and climatic factors affecting dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever incidence. International Journal of Health Geographics.2005. 4:1-13. [CrossRef]

- OMS (Organización Mundial de la Salud), 2023. Dengue – Situación mundial. Epidemiología de la enfermedad. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON498 Consulted in June 2024.

- Huasteca Secreta. Back to Nature. Clima en la Huasteca Potosina.2017. Available online: https://huastecasecreta.com/clima-en-la-huasteca-potosina/#:~:text=La%20Huasteca%20Potosina%20se%20sit%C3%BAa,por%20la%20Huasteca%20es%20Cd.

- Gobierno de España. Ministerio del interior. Dirección General y Emergencias. Lluvia intensas.2020. Available online: https://www.proteccioncivil.es/coordinacion/gestion-de-riesgos/meterologicos/lluvias-intensas.

- González R, Alcalá, J. Enfermedad isquémica del corazón, epidemiología y prevención. Rev Facultad Med UNAM.2010. 5:35-43.

- Harburguer, L. 2024. Available online: https://www.infobae.com/salud/2024/04/02/a-que-temperatura-puede-sobrevivir-el-mosquito-que-transmite-el-dengue/#:~:text=La%20investigadora%20se%C3%B1al%C3%B3%20que%20las,se%20hace%20mucho%20m%C3%A1s%20lento.

- Mordecai, E. A., Caldwell, J. M., Grossman, M. K., Lippi, C. A., Johnson, L. R., Neira, M., Rohr, J. R., Ryan, S. J., Savage, V., Shocket, M. S., Sippy, R., Stewart Ibarra, A. M., Thomas, M. B., Villena, O. Thermal biology of mosquito-borne disease. Ecology letters.2019. 22(10), 1690–1708. [CrossRef]

- Christofferson, R.C., Christopher, N.M. Potential for Extrinsic Incubation Temperature to Alter Interplay Between Transmission Potential and Mortality of Dengue-Infected Aedes aegypti. Environ Health Insights.2016. 10: 119–123. [CrossRef]

- Marinho, R.A., Beserra, E.B., Bezerra-Gusmão, M.A., Porto, V.S., Olinda, R.A., dos Santos, C.A.C. et. al. Effects of temperature on the life cicle, expansion, and dispersion of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culidae) in three cities in Parabia, Brazil. Journal of Vector Ecology. 2016. 41(1): 119-123. [CrossRef]

- Firdaust, M., Yudhastuti, R., Mahmudah, M., Notobroto, H. Predicting dengue incidence using panel data analysis. Journal of Public Health in Africa. 2023. 14(2), 5. [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, Y.H., Lee, J.,Beltz, L. Spatio-temporal patterns of dengue fever cases in Kaoshiung City, Taiwan, 2003-2008. Applied Geography.2012. 34. 587-594. [CrossRef]

- Kolimenakis A, Heinz S, Wilson ML, Winkler V, Yakob L., Michaelakis A. The role of urbanisation in the spread of Aedes mosquitoes and the diseases they transmit—A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis.2021. 15(9): e0009631. [CrossRef]

- Amelinda YS, Wulandari RA, Asyary A. The effects of climate factors, population density, and vector density on the incidence of dengue hemorrhagic fever in South Jakarta Administrative City 2016-2020: an ecological study. Acta Biomed. 2022. Dec 16;93(6): e 2022323. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Istiqamah, S. N. A., Arsin, A. A., Salmah, A. U., Mallongi, A. Correlation Study between Elevation, Population Density, and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever in Kendari City in 2014–2018. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences.2020. 8(T2), 63–66. [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Palis, Y., Pérez-Ybarra, L. M., Infante-Ruíz, M., Comach, G., & Urdaneta-Márquez, L. (2011). Influencia de las variables climáticas en la casuística de dengue y la abundancia de Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) en Maracay, Venezuela. Boletín de Malariología y Salud Ambiental, 51(2), 145–158. Available online: https://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1690-46482011000200004.

- Arbo, A., Sanabria., G., Martínez, C. Influencia del Cambio Climático en las Enfermedades Transmitidas por Vectores. Revista del Instituto de Medicina Tropical.2022. 17(2), 23-36. Epub December 00, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N., Dom, N., Salleh, S., Salim, H. The association between dengue case and climate: A systematic review and meta-analysis.2022. One Health. Oct 31;15:100452. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Estallo, E.E., Ludueña-Almeida, F.F., Introini, M.V., Zaidenberg, M., Almirón, W.R. Weather Variability Associated with Aedes (Stegomyia) aegypti (Dengue Vector)Oviposition Dynamics in Northwestern Argentina. 2015. PLoS ONE 10(5): e0127820. [CrossRef]

- Lega, J., Brown, H.E., Barrera, R. Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Abundance Model Improved With Relative Humidity and Precipitation-Driven Egg Hatching. Journal of Medical Entomology.2017. 54(5), 1375–1384. [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, E.A., de Mendonça, E.M., Cavalcanti, J., Ribeiro, C.M. Impact of small variations in temperature and humidity on the reproductive activity and survival of Aedes aegypti (Diptera, Culicidae). Revista Brasileira de Entomologia. 2010. 54(3): 488–493. [CrossRef]

- Iwamura, T., Guzman-Holst, A., Murray, K. A. Accelerating invasion potential of disease vector Aedes aegypti under climate change. Nature communications.2020. 11(1), 2130. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, F., Nguyen-Tien, T., Pham- Thanh, L., Bui, V., Nguyen-Viet, H., Tran- Hai, S (2019) Urban livestock-keeping and dengue in urban and peri-urban Hanoi, Vietnam. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13 (11): e0007774. [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Y. L., Leitão, P. J., Lakes, T. Assessment of land use factors associated with dengue cases in Malaysia using Boosted Regression Trees. Spatial and spatio-temporal epidemiology.2018. 10, 75–84. [CrossRef]

- Lavayén, A.M. La relación entre el incremento del dengue, el uso de agroquímicos y el cambio climático. Córdoba, Argentina.2020. Available online: https://fundeps.org/dengue-agroquimicos-cambio-climatico/.

- Kalra, N.L.,Kaul.S.M.,Rastogi, R.M. Prevalence of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus– Vectors of Dengue and Dengue hemorrhagic fever in North, North-East and Central India* By N.L.. Dengue Bulletin.Vol.21. 1997. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/148533/dbv21p84.pdf.

- Herrera-Basto E, Prevots DR, Zárate ML, Silva, J.L, Sepúlveda-Amor, J. First reported outbreak of classical dengue fever at 1,700 meters above sea level in Guerrero State, México, June 1988. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 1992; 46(6):649-653. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, S., Hayden, M., Welsh, C., Ochoa, C., Tapia, B., Kobylinski, K., Uejio, C., Zielinski, E., Monache, L., Monaghan, A., Steinhoff, D & Eisen, L. The dengue virus mosquito vector Aedes aegypti at high elevation in Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012. 87(5):902-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ruiz, F., González, A., Vélez, A., Gómez, G., Zuleta, L., Uribe, S., Vélez-Bernal, I. Presencia de Aedes (Stegomyia) aegypti (Linnaeus, 1762) y su infección natural con el virus del dengue en alturas no registradas para Colombia. Biomédica. 2016. 36(2),303-308. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=84345718017.

- Arrasco. Población de áreas de transmisión de dengue y factores demográficos y socioeconómicos. 2024. Perú, 2010-2023. Rev. Cuerpo Med. HNAAA, Vol17. Available online: https://cmhnaaa.org.pe/ojs/index.php/rcmhnaaa/article/view/2327/919.

- Poerwanto, S.H, Chusnaifah, D.L., Giyantolin, G., Windyaraini, D.H. Habitats Characteristic and the Resistance Status of Aedes sp. Larvae in the Endemic Areas of Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever in Sewon Subdistrict, Bantul Regency, Special Region of Yogyakarta. Journal of Tropical Biodiversity and Biotechnology. 2020. 5(2): 157-166. [CrossRef]

- Couttolenc JL. El mosquito Aedes aegypti se reproduce en agua limpia. Universo Sistema de Noricias de la UV.2019. Available in: https://www.uv.mx/prensa/ciencia/el-mosquito-aedes-aegypti-se-reproduce-en-agua-limpia/. Consulted in february 2024. [CrossRef]

- PAHO (Organización Panamericana de la Salud). SIGEpi: Sistema de Información Geográfica en Epidemiología y Salud Pública. 2001. Available online: https://www3.paho.org/spanish/sha/be_v22n3-SIGEpi1.htm.

| Variable | Type | Parameter | Year | Source | |

| Dependent variables | |||||

| Classic dengue fever | Health | Cases | 2015–2021 | [31] | |

| Hemorrhagic dengue fever | Health | Cases | 2015–2021 | ||

| Independent variables | |||||

| Elevation above sea level | Environmental | m | 2020 | [25,32] | |

| Average annual temperature | Environmental | °C | 2015–2020 | [16] | |

| Average annual rainfall | Environmental | mm | 2015–2020 | ||

| Average annual relative humidity | Environmental | % | 2015–2020 | [33] | |

| Distance to bodies of water | Proximity | m | 2015–2020 | [23] | |

| Distance to roads | Proximity | m | 2015–2020 | [25] | |

| Distance to wooded areas | Proximity | m | 2015–2020 | [23] | |

| Distance to grasslands | Proximity | m | 2015–2020 | [23] | |

| Distance to agricultural areas | Proximity | m | 2015–2020 | [23] | |

| XUTM | Location | m | 2020 | [25] | |

| YUTM | Location | m | 2020 | [25] | |

| Population | Social | Number of inhabitants | 2015–2020 | [25] | |

| Homes with piped water | Social | % | 2015–2020 | [25] | |

| Homes with drainage | Social | % | 2015–2020 | [28] | |

| Variable** | Type of dengue | Median | Mean | ± SD | 95% CI | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Upper limit | Lower limit | |||||||

| Elevation above sea level (m)§* | No dengue | 0.0 | 610.7 | 785.1 | 583.4 | 638.1 | 0.0 | 2863.0 |

| Classic | 153.0 | 529.2 | 627.5 | 510.1 | 548.2 | 10.0 | 2106.0 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 201.0 | 692.7 | 725.7 | 592.3 | 793.1 | 19.0 | 1943.0 | |

| Average annual temperature (°C)£* | No dengue | 0.0 | 9.9 | 10.4 | 9.5 | 10.2 | 0.0 | 26.4 |

| Classic | 24.2 | 22.9 | 2.5 | 22.8 | 23.0 | 16.8 | 27.1 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 23.7 | 22.2 | 2.9 | 21.8 | 22.6 | 17.2 | 26.9 | |

| Average annual rainfall (mm)§¥ | No dengue | 0.0 | 296.6 | 436.8 | 281.3 | 311.8 | 0.0 | 2.3 |

| Classic | 1.5 | 1313.4 | 699.6 | 1292.2 | 1334.6 | 272.8 | 2393.5 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 1.5 | 1211.9 | 738.9 | 1109.6 | 1314.2 | 281.2 | 2265.6 | |

| Average annual relative humidity (%)£* | No dengue | 65.3 | 65.5 | 6.6 | 65.3 | 65.7 | 52.9 | 77.8 |

| Classic | 74.7 | 71.1 | 7.2 | 70.8 | 71.3 | 53.3 | 77.7 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 73.5 | 68.9 | 8.5 | 67.7 | 70.0 | 54.1 | 77.7 | |

| Distance to bodies of water (m)£ | No dengue | 1.5 | 35,535.3 | 4,3847.0 | 3,4006.4 | 37,064.2 | 0.0 | 204,812.6 |

| Classic | 1.5 | 2571.6 | 3042.8 | 2479.3 | 2663.9 | 0.0 | 25,497.1 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 1.9 | 2738.3 | 3457.5 | 2259.8 | 3216.7 | 0.0 | 19,440.4 | |

| Distance to roads (m)£ | No dengue | 4.9 | 29,161.4 | 4,3538.1 | 2,7643.3 | 3.0679.5 | 0.0 | 1.98009.7 |

| Classic | 90.0 | 170.4 | 218.9 | 163.8 | 177.1 | 0.0 | 2023.4 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 108.2 | 186.1 | 222.0 | 155.4 | 216.9 | 0.0 | 1171.5 | |

| Distance to grasslands (m)£* | No dengue | 1.9 | 27,688.6 | 43,314.5 | 26,178.3 | 29,198.9 | 0.0 | 197,347.0 |

| Classic | 60.0 | 127.2 | 269.9 | 119.1 | 135.4 | 0.0 | 2278.8 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 60.0 | 92.0 | 113.7 | 76.3 | 107.7 | 0.0 | 768.4 | |

| Distance to wooded areas (m)£* | No dengue | 3.3 | 28,392.1 | 4,3547.3 | 2,6873.6 | 2,9910.5 | 0.0 | 195,719.2 |

| Classic | 123.7 | 411.5 | 1,117.5 | 377.6 | 445.4 | 0.0 | 12,678.7 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 150.0 | 305.3 | 437.6 | 244.8 | 365.8 | 0.0 | 3390.9 | |

| Distance to agricultural areas£ | No dengue | 5.0 | 30,742.9 | 45,429.5 | 29,158.8 | 32,326.9 | 0.0 | 200,867.4 |

| Classic | 42.4 | 221.0 | 891.0 | 194.0 | 248.1 | 0.0 | 15,671.1 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 42.4 | 217.9 | 983.3 | 81.8 | 354.0 | 0.0 | 13,642.2 | |

| XUTM (m)£* | No dengue | 423,366.2 | 423,375.6 | 80,732.8 | 420,560.6 | 426,190.6 | 286,266.2 | 560,466.2 |

| Classic | 502,266.2 | 466,630.2 | 80,774.7 | 464,180.8 | 469,079.6 | 281,676.2 | 565,356.2 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 498,726.2 | 445,355.8 | 93,106.9 | 432,470.5 | 458,241.0 | 288,456.2 | 565,626.2 | |

| YUTM (m)£* | No dengue | 2,509,896.2 | 2,509,887.0 | 98,151.3 | 2,506,464.6 | 2,513,309.4 | 2,342,631.2 | 26,77,131.2 |

| Classic | 2,423,356.2 | 2,408,033.7 | 49,052.4 | 2,406,546.2 | 2,409,521.2 | 2,341,191.2 | 26,79,921.2 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 2,427,351.2 | 2,423,161.5 | 72,889.9 | 2,413,074.2 | 2,433,248.9 | 2,344,341.2 | 26,79,351.2 | |

| Population (n)£ | No dengue | 128.1 | 304.8 | 3161.0 | 194.6 | 415.0 | 2.7 | 93,466.2 |

| Classic | 620.8 | 7682.4 | 20,642.2 | 7056.5 | 8308.4 | 4.9 | 95,368.7 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 638.7 | 10,351.0 | 23,850.0 | 7050.3 | 13,651.6 | 7.3 | 92,941.6 | |

| Homes with piped water (%)£ | No dengue | 16.0 | 24.1 | 23.2 | 23.3 | 24.9 | 0.0 | 96.8 |

| Classic | 4.2 | 10.3 | 17.5 | 9.8 | 10.8 | 0.0 | 100.0 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 4.9 | 11.5 | 18.7 | 8.9 | 14.1 | 0.0 | 98.5 | |

| Homes with drainage (%)£ | No dengue | 10.0 | 16.3 | 17.1 | 15.7 | 16.9 | 0.0 | 83.6 |

| Classic | 8.0 | 12.5 | 13.8 | 12.1 | 13.0 | 0.0 | 90.1 | |

| Hemorrhagic | 9.1 | 13.5 | 14.2 | 11.5 | 15.4 | 0.0 | 63.9 | |

| Variable | Classic dengue fever | Dengue hemorrhagic fever | ||

| Beta | p | Beta | p | |

| Elevation above sea level | -0.165E-03 | <0.001 | 0.130E-03 | 0.148 |

| Average temperature | 0.338 | <0.001 | 0.258 | <0.001 |

| Average annual rainfall | 0.268E-02 | <0.001 | 0.217E-02 | <0.001 |

| Average annual relative humidity | 0.104 | <0.001 | 0.719E-01 | <0.001 |

| Distance to bodies of water | -0.292E-03 | <0.001 | -0.318E-03 | <0.001 |

| Distance to roads | -0.405E-02 | <0.001 | -0.436E-02 | <0.001 |

| Distance to grasslands | -0.107E-02 | <0.001 | -0.180E-02 | <0.001 |

| Distance to wooded areas | -0.336E-03 | <0.001 | -1.888 | <0.001 |

| Distance to agricultural areas | -0.287E-03 | <0.001 | -0.529E-03 | <0.001 |

| XUTM | 0.634E-05 | <0.001 | 0.336E-05 | <0.001 |

| YUTM | -0.176E-04 | <0.001 | -0.192E-04 | <0.001 |

| Population | 0.767E-03 | <0.001 | 0.980E-04 | <0.001 |

| Homes with piped water | -0.348E-01 | <0.001 | -0.359E-01 | <0.001 |

| Homes with drainage | -0.159E-01 | <0.001 | -0.111E-01 | 0.021 |

| Variable | Classic dengue fever | Dengue hemorrhagic fever | ||||

| Beta | p | Collinearity | Beta | p | Collinearity | |

| Elevation above sea level | -0.265E-02 | <0.001 | N | -0.297E-02 | <0.001 | S |

| Average temperature | 0.198 | <0.001 | N | 0.128 | 0.268 | N |

| Average annual rainfall | 0.911E-03 | <0.001 | N | 0.152E-02 | <0.001 | N |

| Average annual relative humidity | -0.131 | 0.001 | N | -0.369 | 0.001 | N |

| Distance to bodies of water | -0.413E-04 | 0.001 | S | -0.837E-04 | 0.008 | S |

| Distance to roads | -0.389E-02 | <0.001 | S | -0.377E-02 | <0.001 | S |

| Distance to grasslands | 0.975E-03 | <0.001 | S | -0.457E-04 | 0.937 | S |

| Distance to wooded areas | 0.143E-03 | 0.024 | S | -0.185E-03 | 0.218 | S |

| Distance to agricultural areas | -0.207E-04 | 0.518 | N | -0.971E-04 | 0.272 | S |

| XUTM | -0.274E-04 | <0.001 | S | 0.258E-05 | 0.746 | S |

| YUTM | -0.975E-05 | <0.001 | N | 0.379E-05 | 0.083 | S |

| Population | 0.209E-03 | <0.001 | N | 0.706E-04 | <0.001 | N |

| Homes with piped water | -0.676E-02 | 0.006 | N | -0.738E-02 | 0.192 | N |

| Homes with drainage | -0.111E-01 | 0.003 | N | -0.492E-02 | 0.560 | S |

| Constant | 39.639 | <0.001 | -- | 13.040 | 0.057 | -- |

| Variable | Classic dengue fever | Dengue hemorrhagic fever | ||

| Beta | p | Beta | p | |

| Elevation above sea level | -2.365 | <0.001 | - | - |

| Average annual temperature | 4.240 | <0.001 | 4.029 | 0.017 |

| Average annual rainfall | 0.646 | <0.001 | 1.936 | <0.001 |

| Annual relative humidity | -3.034 | <0.001 | -1.573 | 0.002 |

| Distance to agricultural areas | -3.861 | <0.001 | - | - |

| YUTM | -0.894 | <0.001 | - | |

| Population | 5.600 | <0.001 | 1.169 | <0.001 |

| Homes with piped water (%) | -0.152 | 0.001 | -0.384 | <0.001 |

| Homes with drainage (%) | -0.130 | 0.006 | - | - |

| Constant | -0.674 | 0.039 | -3.943 | <0.001 |

| Level of risk | Percentage of population | |

| Classic dengue fever | Dengue hemorrhagic fever | |

| Very low | 30.5 | 92.0 |

| Under | 6.1 | 4.2 |

| Medium | 8.0 | 1.5 |

| High | 9.2 | 1.4 |

| Very high | 46.3 | 0.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).