Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

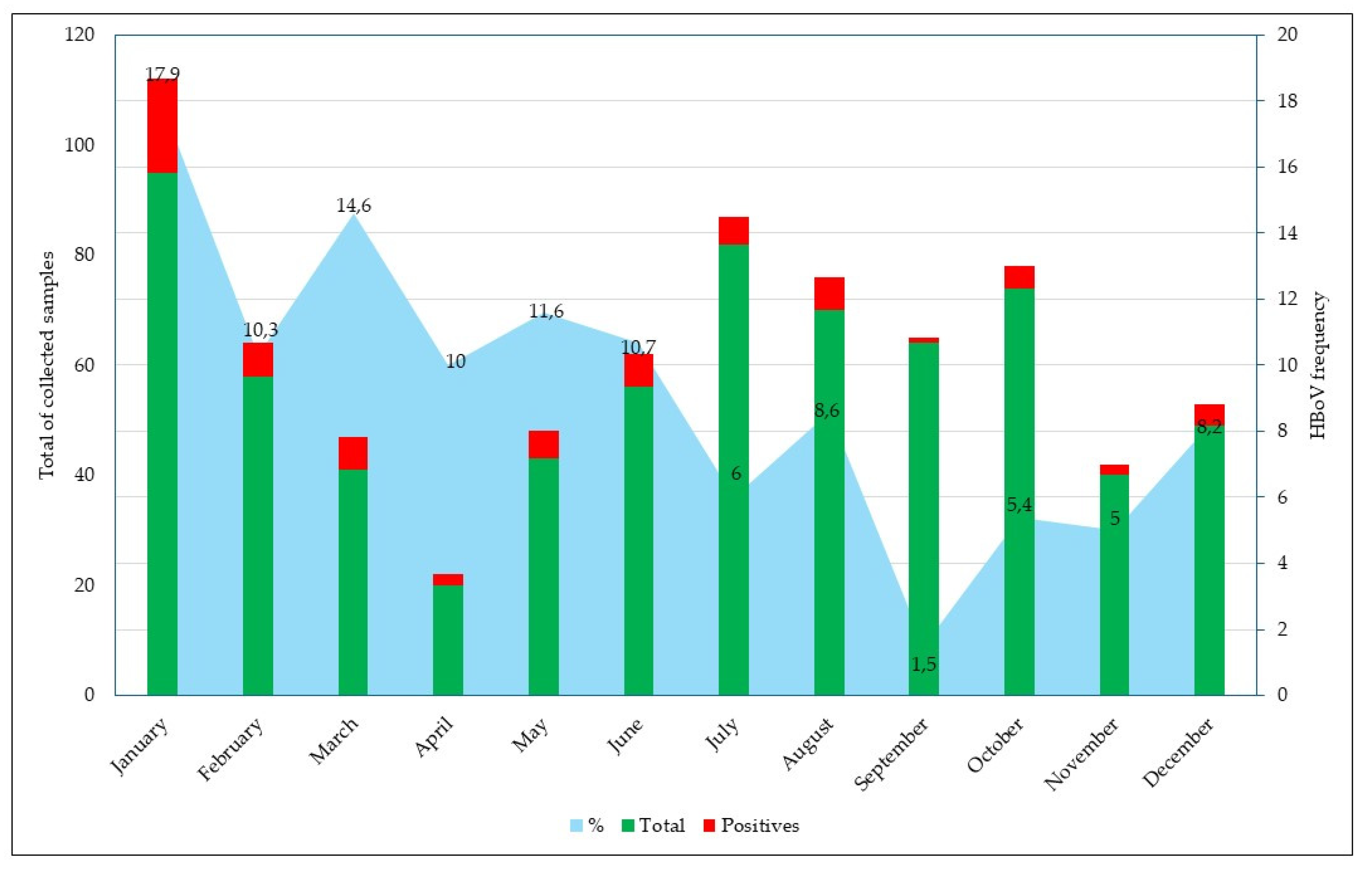

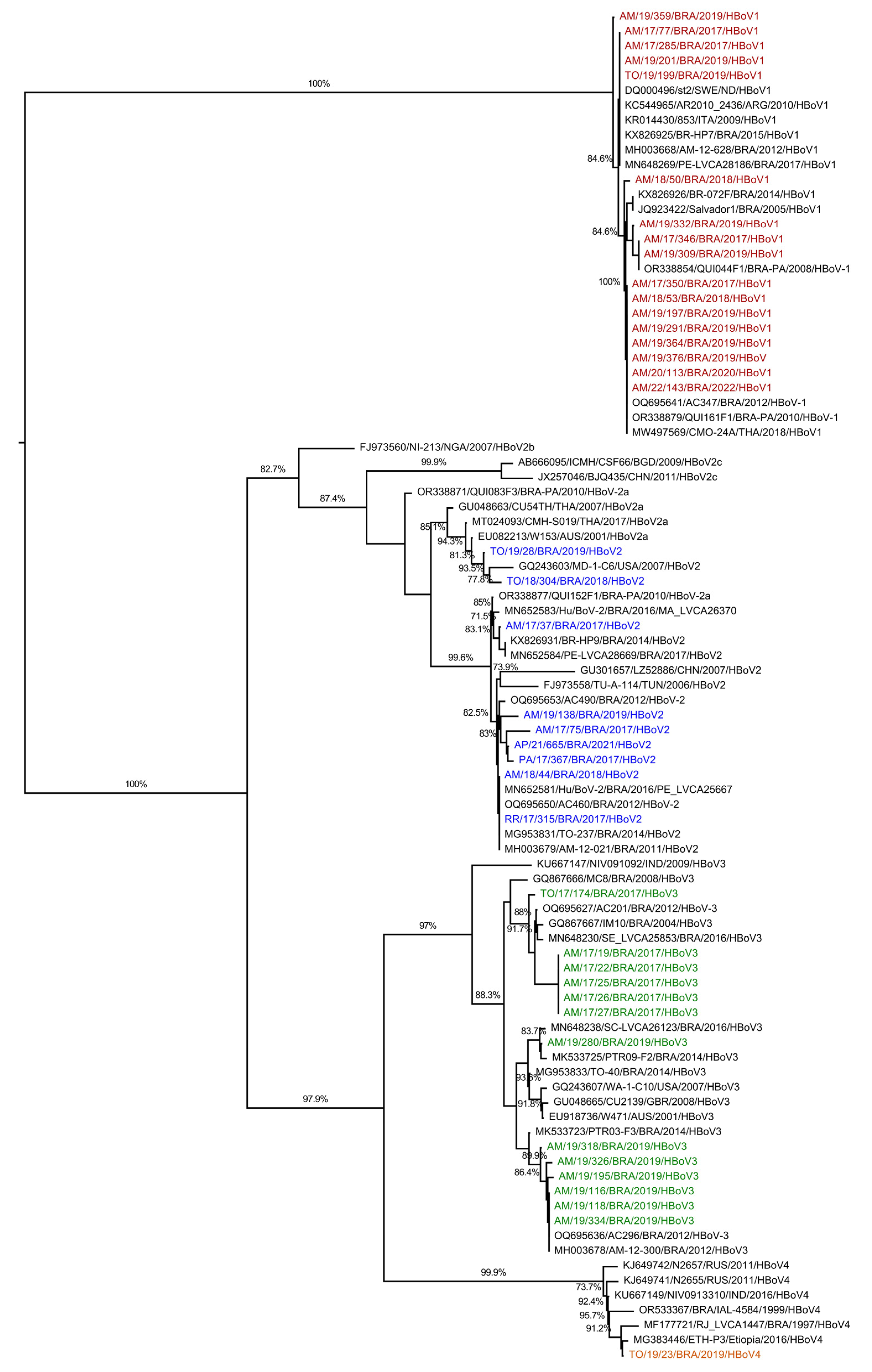

Acute gastroenteritis (AG) is a major illness in early childhood. Recent studies suggest a potential association between Human Bocavirus (HBoV) and AG. HBoV, a non-enveloped virus with a single-strand DNA genome, belongs to the Parvoviridae family. This study aimed to describe the frequency of HBoV in Northern Brazil using samples from AG patients collected between 2017 and 2022. Fecal samples from the viral gastroenteritis surveillance network at the Evandro Chagas Institute (IEC) were analyzed. Fecal suspensions (20%) were prepared, and the viral genome was extracted. PCR and Nested-PCR were employed to detect HBoV, followed by nucleotide sequencing to identify viral types. Out of 692 samples, HBoV positivity was 9.2% (69/693). Genotypes HBoV-1, HBoV-2, HBoV-3, and HBoV-4 were found in 42.5% (17/40), 22.5% (9/40), 33.5% (13/40), and 2.5% (1/40) of the specimens, respectively. Co-infections with HBoV and other enteric viruses occurred in 48.43% (31/64) of cases, with RVA being the most frequent (72.41% or 21/29). The study concludes that HBoV circulates significantly in Northern Brazil and is associated with co-infections. Further research is needed to clarify HBoV role as a causative agent of AG in the region.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Specimens and Ethical Aspects

2.2. Nucleic Acid Extraction

2.3. HBoV Molecular Detection

2.4. Molecular Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. HBoV Detection

3.2. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of HBoV Infections

3.3. Coinfection Between HBoV and Other Gastroenteric Viruses

3.4. HBoV Genotypes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hartman, S.; Brown, E.; Loomis, E.; Russell, H.A. Gastroenteritis in Children. Am Fam Physician 2019, 99, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Diarrhoeal Disease. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Tarris, G.; de Rougemont, A.; Charkaoui, M.; Michiels, C.; Martin, L.; Belliot, G. Enteric Viruses and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Viruses 2021, Vol. 13, Page 104 2021, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, A.; Simmonds, P.; Slikas, E.; Li, L.; Bodhidatta, L.; Sethabutr, O.; Triki, H.; Bahri, O.; Oderinde, B.S.; Baba, M.M.; et al. Human Bocaviruses Are Highly Diverse, Dispersed, Recombination Prone, and Prevalent in Enteric Infections. J Infect Dis 2010, 201, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, K.; Zhao, J.; Feng, Z.; Park, S.Y.; McFarlin, S.; Cheng, F.; Yan, Z.; Wang, J.; Qiu, J. N6-Methyladenosine Modification of a Parvovirus-Encoded Small Noncoding RNA Facilitates Viral DNA Replication through Recruiting Y-Family DNA Polymerases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allander, T.; Tammi, M.T.; Eriksson, M.; Bjerkner, A.; Tiveljung-Lindell, A.; Andersson, B. Cloning of a Human Parvovirus by Molecular Screening of Respiratory Tract Samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 12891–12896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.L.; Higgins, G.D.; Davidson, G.P.; Givney, R.C.; Ratcliff, R.M. A Novel Bocavirus Associated with Acute Gastroenteritis in Australian Children. PLoS Pathog 2009, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Slikas, E.; Simmonds, P.; Chieochansin, T.; Naeem, A.; Shaukat, S.; Alam, M.M.; Sharif, S.; Angez, M.; Zaidi, S.; et al. A New Bocavirus Species in Human Stool. J Infect Dis 2009, 199, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, G.S.; Silva Sampaio, M.L.; Menezes, A.D.L.; Tigre, D.M.; Moura Costa, L.F.; Chinalia, F.A.; Sardi, S.I. Human Bocavirus in Acute Gastroenteritis in Children in Brazil. J Med Virol 2016, 88, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolina, M.; Albuquerque, M.; Rocha, L.N.; Benati, F.J.; Soares, C.C.; Maranhão, A.G.; Ramírez, M.L.; Erdman, D.; Santos, N. Human Bocavirus Infection in Children with Gastroenteritis, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2007, 13, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, L.S.; Lima, A.B.F.; Pantoja, K.C.; Lobo, P.S.; Cruz, J.F.; Guerra, S.F.S.; Bezerra, D.A.M.; Bandeira, R.S.; Mascarenhas, J.D.P. Molecular Epidemiology of Human Bocavirus in Children with Acute Gastroenteritis from North Region of Brazil. J Med Microbiol 2019, 68, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jartti, T.; Hedman, K.; Jartti, L.; Ruuskanen, O.; Allander, T.; Söderlund-Venermo, M. Human Bocavirus-the First 5 Years. Rev Med Virol 2012, 22, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salbetti, M.B.C.; Boggio, G.A.; Abbiatti, G.; Sandoz, A.M.; Villarreal, V.; Torres, E.; Pedranti, M.; Zalazar, J.A.; Moreno, L.; Adamo, M.P. Diagnosis and Clinical Significance of Human Bocavirus 1 in Children Hospitalized for Lower Acute Respiratory Infection: Molecular Detection in Respiratory Secretions and Serum. J Med Microbiol 2022, 71, 001595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikhotso, M.C.; Khumela, R.; Kabue, J.P.; Traoré-Hoffman, A.N.; Potgieter, N. Predominance of Human Bocavirus Genotype 1 and 3 in Outpatient Children with Diarrhea from Rural Communities in South Africa, 2017-2018. Pathogens 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantachit, N.; Kochjan, P.; Khamrin, P.; Kumthip, K.; Maneekarn, N. Human Bocavirus Genotypes 1, 2, and 3 Circulating in Pediatric Patients with Acute Gastroenteritis in Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2012-2018. J Infect Public Health 2021, 14, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, E.; França, Y.; de Azevedo, L.S.; Medeiros, R.S.; Guiducci, R.; Guadagnucci, S.; Luchs, A. Genotypic Diversity and Long-Term Impact of Human Bocavirus on Diarrheal Disease: Insights from Historical Fecal Samples in Brazil. J Med Virol 2024, 96, e29429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, M.; Tumolo, M.R.; Verri, T.; Romano, A.; Serio, F.; De Giorgi, M.; De Donno, A.; Bagordo, F.; Zizza, A. Human Bocavirus: Current Knowledge and Future Challenges. World J Gastroenterol 2016, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasure, N.; Gopalkrishna, V. Molecular Epidemiology and Clinical Severity of Human Bocavirus (HBoV) 1-4 in Children with Acute Gastroenteritis from Pune, Western India. J Med Virol 2017, 89, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijač, M.; Meštrović, T.; Ivković-Jureković, I.; Tot, T.; Vraneš, J.; Ljubin-Sternak, S. The Role of Quantitative PCR in Evaluating the Clinical Significance of Human Bocavirus Detection in Children. Viruses 2024, 16, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhirakovskaia, E.; Tikunov, A.; Tymentsev, A.; Sokolov, S.; Sedelnikova, D.; Tikunova, N. Changing Pattern of Prevalence and Genetic Diversity of Rotavirus, Norovirus, Astrovirus, and Bocavirus Associated with Childhood Diarrhea in Asian Russia, 2009–2012. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2019, 67, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boom, R.; Sol, C.J.A.; Heijtink, R.; Wertheim-van Dillen, P.M.E.; Van der Noordaa, J. Rapid Purification of Hepatitis B Virus DNA from Serum. J Clin Microbiol 1991, 29, 1804–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. DNA Sequencing with Chain-Terminating Inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1977, 74, 5463–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious Basic: An Integrated and Extendable Desktop Software Platform for the Organization and Analysis of Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, L.R.P.; Calvet, F.C.; Sousa, K.L.; Silva, V.P.; Lobo, P.S.; Penha, E.T.; Guerra, S.F.S.; Bezerra, D.A.M.; Mascarenhas, J.D.P.; Pinheiro, H.H.C.; et al. Prevalence of Rotavirus and Human Bocavirus in Immunosuppressed Individuals after Renal Transplantation in the Northern Region of Brazil. J Med Virol 2019, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente, D.; Cilla, G.; Montes, M.; Pérez-Yarza, E.G.; Pérez-Trallero, E. Human Bocavirus, a Respiratory and Enteric Virus. Emerg Infect Dis 2007, 13, 636–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachooei, A.; Karbalaie Niya, M.H.; Khales, P.; Sabaei, M.; Fard, S.R.; Hamidzade, M.; Tavakoli, A. Prevalence, Molecular Characterization, and Clinical Features of Human Bocavirus in Children under 5 Years of Age with Acute Gastroenteritis Admitted to a Specialized Children’s Hospital in Iran: A Cross-Sectional Study. Health Sci Rep 2023, 6, e1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta, F.C.; Varella, R.B.; Guimarães, M.A.A.M.; Miagostovich, M.P.; Fumian, T.M. Human Bocavirus in Brazil: Molecular Epidemiology, Viral Load and Co-Infections. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, F.D.T.B.; Ramos, E.S.F.; Lobo, P.S.; Cardoso, J.F.; Penha Júnior, E.T.; Bezerra, D.A.M.; Neves, M.A.O.; Andrade, J.A.A.; Moraes Silva, M.C.; Mascarenhas, J.D.P.; et al. Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics of Human Bocavirus Infection in Children with or without Acute Gastroenteritis in Acre, Northern Brazil. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-C.; Chiu, S.-C.; Liao, L.-M.; Chen, Y.-H.; Lu, Y.-A.; Lin, J.-H. Human Bocavirus Circulating in Patients With Acute Gastroenteritis in Taiwan, 2018-2022. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, M.B.; de Assis, R.M.S.; Andrade, J. da S.R. de; Fialho, A.M.; Fumian, T.M. Rotavirus A during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Brazil, 2020–2022: Emergence of G6P[8] Genotype. Viruses 2023, Vol. 15, Page 1619 2023, 15, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, T.T.; Souza, M.; Fiaccadori, F.S.; Borges, A.M.T.; da Costa, P.S.; Cardoso, D. das D. de P. Human Bocavirus 1 and 3 Infection in Children with Acute Gastroenteritis in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2012, 107, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, F.E.A.; Perdigão, A.C.B.; Ribeiro, J.F.; Florêncio, C.M.G.D.; Oliveira, F.M.S.; Pereira, S.A.R.; Botosso, V.F.; Siqueira, M.M.; Thomazelli, L.M.; Caldeira, R.N.; et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Epidemic Periods in an Equatorial City of Brazil. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2013, 7, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, C.; García-García, M.L.; Pozo, F.; Carballo, D.; Martínez-Monteserín, E.; Casas, I. Infections and Coinfections by Respiratory Human Bocavirus during Eight Seasons in Hospitalized Children. J Med Virol 2016, 88, 2052–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, N.; Parvez, A.K.; Haque, A.; Talukder, A.A.; Ushijima, H.; Dey, S.K. Molecular and Epidemiological Trends of Human Bocavirus and Adenovirus in Children with Acute Gastroenteritis in Bangladesh during 2015 to 2019. J Med Virol 2020, 92, 3194–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, A.; Kesti, O.; Elenius, V.; Eskola, A.L.; Døllner, H.; Altunbulakli, C.; Akdis, C.A.; Söderlund-Venermo, M.; Jartti, T. Human Bocaviruses and Paediatric Infections. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2019, 3, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, T.T. de; Almeida, T.N.V.; Fiaccadori, F.S.; Souza, M.; Badr, K.R.; Cardoso, D. das D. de P. Identification of Human Bocavirus Type 4 in a Child Asymptomatic for Respiratory Tract Infection and Acute Gastroenteritis – Goiânia, Goiás, Brazil. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases 2017, 21, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Features | HBoV infection | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (n=628) | Positive (n=64) | Total (n=692) | p value | |||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female | 303 | 48.2 | 27 | 42.2 | 330 | 47.7 | 0.35 | |||

| Male | 325 | 51.8 | 37 | 57.8 | 362 | 52.2 | ||||

| Age group (months) | ||||||||||

| 0 – 24 | 375 | 59.7 | 45 | 70.3 | 420 | 60.7 | 0,15 | |||

| 25 – 60 | 115 | 18.3 | 10 | 15.6 | 125 | 18.1 | ||||

| >61 | 136 | 21.7 | 8 | 12.5 | 144 | 20.8 | ||||

| NI* | 2 | 0.3 | 1 | 1.6 | 3 | 0.4 | ||||

| Clinical symptoms | ||||||||||

| Diarrhea | 570 | 90.,8 | 58 | 90.6 | 628 | 90.7 | 0.62 | |||

| Vomiting | 405 | 64.5 | 43 | 67.2 | 448 | 64.7 | 0.75 | |||

| Fever | 323 | 51.4 | 35 | 54.7 | 358 | 51.7 | 0.47 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).