1. Introduction

Water is one of the valuable resources to sustain life on earth. It covers about 70.9% of the total surface of the earth. However, 3% of the total water is present as fresh water. This small amount of the total water is used for various purposes, e.g. drinking, agricultural and domestic use. However, many industries directly discharge their waste into fresh water. Globally, environmental pollution is one of the essential issues [

1,

2]. In our daily lives, a large number of toxic and harmful substances are produced [

3]. These substances constantly circulate in the environment and continue to endanger the earth [

4]. Among them, industrial wastewater is particularly harmful to the environment. Therefore, it makes sense to find effective ways to treat contaminants in the water [

5]. Most of the organic pollutants used are coming from the textile, plastic, paint and pharmaceutical industries and are classified as poorly biodegradable and highly toxic [

6,

7]. Trichloroethylene (TCE) is one of the predominant chlorinated compounds that has been widely used in commercial and industrial fields due to its unique properties [

8,

9]. The widespread application of TCE has led to pervasive groundwater and soil contamination, which is classified as a Group 1 human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [

10]. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the control standard for TCE is 0.0050 mg/L [

11].

On the other hand, Rhodamine B (RhB) is a widely used cationic basic dye, which belongs to anthraquinone [

12]. The wastewater produced by this dye is characterized by high chromaticity, difficult biochemical degradation, and high concentration of organic contaminants [

13]. Traditional adsorption techniques to degrade RhB lead to secondary contamination, while biochemical techniques hinder the degradation of chemically stable RhB [

14].

To address this problem, in recent decades, researchers have used a number of chemical and physical processes including coagulation, flocculation, membrane filtration, and adsorption. In addition, they are inefficient and expensive, generating secondary products that require further processing [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Among the various transition metals under study, copper nanoparticles (CuNPs) are less expensive compared to noble metals such as platinum, silver, and gold and are widely used in catalysis, cooling fluids, and conducting bonds. Copper nanoparticles (CuNPs) have important physical and chemical properties, catalytic, optical, magnetic and heat transfer properties, high surface area/volume ratio, antibacterial potency and biocidal properties [

19,

20]. Therefore, CuNPs could be used as effective candidates for the removal of polluting organic compounds from the environment. However, CuNPs applications suffer from irreversible aggregation and difficult recovery due to their small size and high surface energy [

21,

22]. To overcome these problems, Cu NP-based composites have been fabricated by integrating them into carbon materials, such as carbon fibers, carbon nanotubes, activated carbon, and graphene, using them as carriers to support Cu NPs due to their stability. thermal and mechanical [

23,

24,

25,

26].

In this work, a new methodology has been developed to degrade toxic compounds in water (TCE and RhB) in a simple, ecological and sustainable way through a new technology based on the creation of copper nanoparticles formed

in situ on a graphene support functionalized previously with an enzyme, by the

in-situ formation cu nanoparticles induced by protein [

27].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Thermomyces lanuginosus solution (Lipozyme® TL 100L) was from Novozymes (Copenhagen, Denmark). Copper (II) sulfate pentahydrate, sodium acetate and hydrogen peroxide (33%, H2O2) were from Panreac (Barcelona, Spain). Graphite flakes, sodium bicarbonate, sodium phosphate, sodium borohydride, Rhodamine B (RhB), trichloroethylene (TCE), 1,1-dichloroethylene (1,1-DCE), and vinyl chloride (VC) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). HPLC grade acetonitrile, methanol, tetrahydrofurane (THF) and dioxane (98%) were from Scharlau (Barcelona, Spain). Tween-80, dodecyl sulphate sodium (85%), Mercaptoethanol and cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) were purchased from Thermo Fischer Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts, EE.UU).

2.2. Structural Characterization

The metal contents were measured by an inductively coupled plasma - optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) (OPTIMA 2100 DV instrument; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). X-Ray diffraction (XRD) patterns with Cu Kα radiation (Texture Analysis D8 Advance Diffractometer; Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) were used for structure characterization. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-resolution TEM microscopy (HR-TEM) images (2100F microscope; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) were used to measure the size and distribution of the samples. Interplanar spacing in the nanostructures was calculated by using the inversed Fourier transform with the GATAN digital micrograph program (Corporate Headquarters, Pleasanton, CA, USA). X-ray photoelectron analysis (XPS) was carried out on SPECS GmbH spectrometer equipped with Phoibos 150 9MCD energy analyzer. A nonmonochromatic magnesium X-ray source with a power of 200 W and voltage of 12 kV was used. FTIR spectra were recorded on FT-IR 470-Series (JASCO) spectrophotometer using glass of germanium. To recover the bionanohybrid, a Biocen 22 R (Orto-Alresa, Ajalvir, Spain) refrigerated centrifuge was used. Spectrophotometric analyses for RhB reactions were run on a V-730 spectrophotometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). A HPLC pump PU-4180 (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) was used to analyse the TCE reactions. Analyses were run at 25 ºC using a UV-4075 UV/Vis detector (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan).

2.3. Synthesis of G@TLL-Cu2O Hybrid

500 mg of G@TLL (containing 3 mg of TLL) were added to 8 ml buffer 0.1M of sodium phosphate pH 7) in a 75 ml glass vial containing a small magnetic bar stirrer. Then, 80 mg of Cu2SO4 · 5H2O (10 mg/mL) were added to the solution with the support and it was maintained for 16 hours. After 16 h, 800 µL of NaBH4 (45 mg) aqueous solution (1.2 M) was added to the black solution obtaining a final concentration of 0.12 M sodium borohydride in the mixture. The mixture was reduced for 30 min. After incubation, the mixture was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 20 min. The sediment generated was re-suspended in 5 ml of water. It was centrifuged again at 8000 rpm for 20 min and the supernatant was removed. The process was repeated two more times. Finally, the supernatant was removed and the pellet was re-suspended in 2 mL of water and added to a cryogenization tube, frozen with liquid nitrogen and lyophilized overnight. After that, the so-called G@TLL-Cu2O was obtained.

2.4. Experiments of G@TLL-Cu2O Hybrid Enzyme Desorption on Graphene Support

20 mg of G@TLL-Cu2O were incubated in 1 mL of aqueous solution containing for CTAB (1%v/v), acetonitrile (10,50,70 or 90% v/v), Tween 80 (2%v/v), and Triton-X100 (2% and 5%v/v) for 1 h. Then supernatant and suspension was analysed by enzymatic activity assay. The solid was filtered and analysed by XRD. Two additional experiments were performed, at 90°C and 50ºC for 1 h with water, and other with electrophoretic native degradation buffer (SDS). The solids were also analysed by XRD.

2.5. G@TLL-Cu2O Hybrid Catalyzing the Degradation of Trichloroethylene (TCE)

A solution of 10 mM of TCE in pure acetonitrile was prepared. 0.2 ml of this solution was dissolved in 2 ml of 50:50 pure ACN: distilled water, 100mM of buffer sodium acetate pH4, buffer sodium phosphate pH7 or buffer sodium bicarbonate pH8.5 to achieve a concentration of 1mM TCE (131.4 mg/L). Then, in some cases, hydrogen peroxide (33%, v/v) was added to this TCE solution to obtain a concentration 10eq. To initialize the reaction, 1-10mg of the catalyst was added to of this solution (TCE or TCE-H2O2) in a 7 mL glass flask. Gentle stirring was provided at room temperature (25ºC) by a roller. At given time intervals, 20 µl of reaction solution was taken and diluted in 180 µl of acetonitrile pure for HPLC analysis. For each degradation group, three parallel experiments were performed, and the error range was <5%. HPLC conditions were 50:50 acetonitrile: milliQ water at 1 mL/min, λ:215 nm using UV-Vis detector. Under these conditions, the retention time of TCE was 9 min. TCE subproducts such as 1,1-DCE or vinyl chloride were detected at 7 min and 4 min respectively, using commercial standard pure products of both substrates as control. TOF (turnover frequency) value was calculated by [mmols TCE converted / mmols Cu x time (min)-1].

2.6. G@TLL-Cu2O Hybrid Catalyzing the Degradation of Rhodamine B (RhB)

A solution of 0.1 mM (48mg/L) of RhB in water: ACN 50:50 was prepared. 2 mL of this solution was mixed with 200mM-500mM of H2O2. To initialize the reaction, 5-10mg of catalysts were added to this solution (RhB+H2O2) in a 7 mL glass flask. Gentle stirring was provided at room temperature (25ºC) by a roller. At given time intervals, 50 µl of reaction solution was taken and diluted in 1950 µl of distilled water measuring the absorption spectrum between 800 and 300 nm in a spectrophotometer with maximum absorbance at 550nm.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preparation and Characterization of G@TLL-Cu2O Hybrid

Graphite flakes were initially used to obtain graphene with immobilized lipase (G@TLL) [

27]. This strategy ensures the presence of lipase by fixing the open conformation and homogeneously dispersed on the solid material. This is due to the site-oriented interactions between hydrophobic graphene surface with particularly hydrophobic pocket area in the open conformation of lipase constitute by surrounding active site and lid area (

Figure S1A).

Thermomyces lanuginosus lipase (TLL), a typical lipase which mainly exists as dimeric form in solution was used. The more hydrophobic area around active site and a larger oligopeptide lid of this enzyme allowed to create an immobilized G@TLL with better graphene-exfoliation. Complete immobilization was achieved after 40 min incubation at room temperature (

Figure S1B). The enzyme adsorbed on the graphene support showed even higher activity compared to soluble one (

Figure S1C), due to fixing open monomeric conformation of the enzyme on the solid phase compared to the dimeric soluble form [

28].

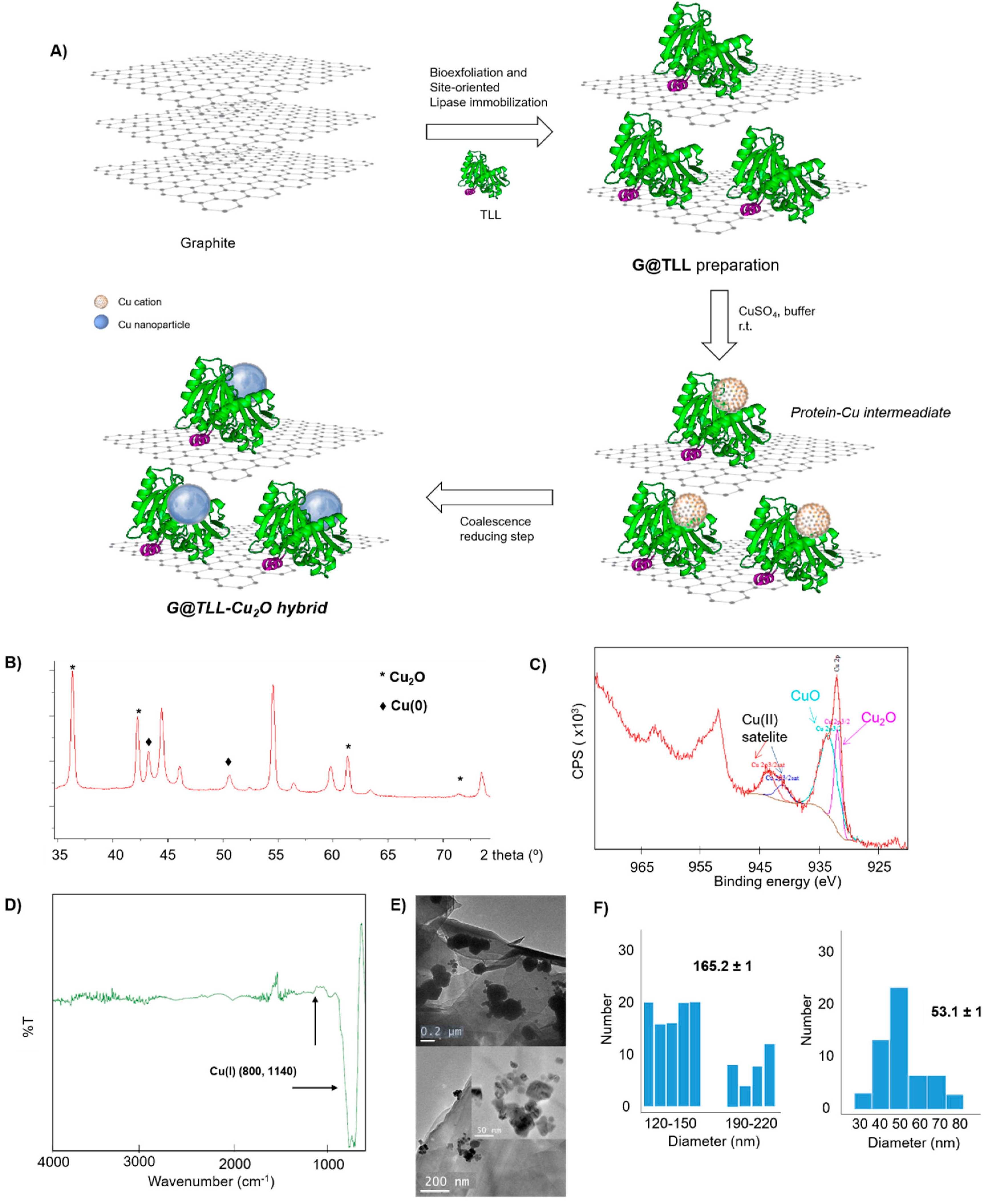

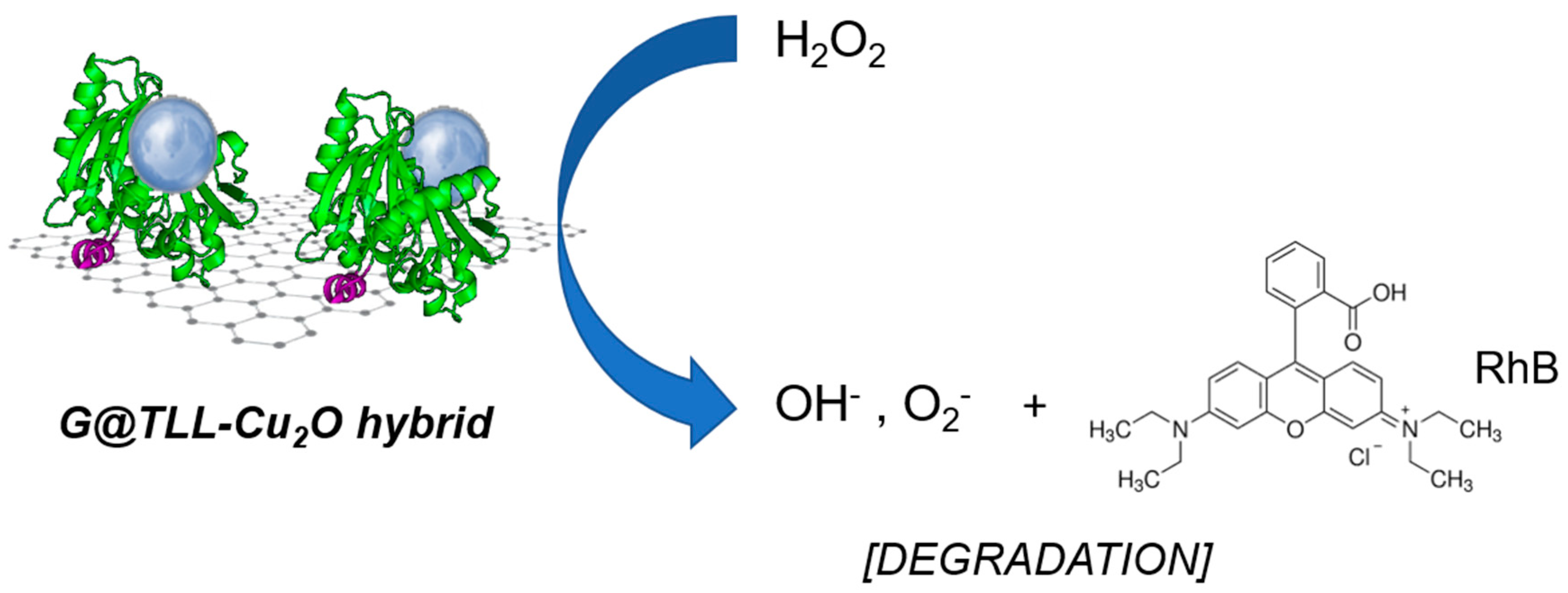

The synthesis of

G@TLL-Cu2O heterogeneous hybrid was performed as shown in

Figure 1A. Copper nanoparticles (CuNPs) were synthesized by a mild-aqueous methodology, using copper sulfate and where site-oriented supported TLL acted as template and binder. The preparation started by mixing G@TLL in a phosphate solution at pH 7 with the copper salt, followed by a reducing step with NaBH

4 producing the formation of the heterogeneous hybrid.

A full characterization of the hybrid was performed (

Figure 1B-F). The wide-angle X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirmed the presence of Cu

2O as mainly Cu species in this hybrid, by observation of four characteristic peaks, three of them assigned to planes (111), (200) and (220), respectively, of the fcc Cu lattice, with a minor fraction of Cu(0) (

Figure 1B). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was used to characterize the surface composition and electronic states of these Cu catalysts and the results confirmed the presence of Cu (

Figure S2). The high resolution XPS spectrum of Cu2p have peaks at 932.5 eV for Cu

2O and peaks at 934.39 eV and 955.00 eV for CuO (

Figure 1C and

Figure S2). FT-IR analysis also confirmed the presence of Cu

2O (

Figure 1D). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis revealed mainly the formation of two size of spherical nanoparticles with a diameter average size 53nm and 165nm (

Figure 1E-F and

Figure S3). The inductively coupled plasma−optical emission spectroscopy results showed that the content of Cu in

G@TLL-Cu2O was 6.4% (w/w).

Finally, the stability of the hybrid was evaluated at different temperatures, or in the presence of different additives and no desorption of enzyme-metal system was observed in any case (

Figure S4).

3.2. Trichloroethylene (TCE) Degradation Catalyzed by G@TLL-Cu2O Hybrid

Firstly, the possible adsorption of TCE to the G@TLL support was studied (

Figure S5). In it, different concentrations of solvent: water were evaluated until there was no adsorption, the optimal point was 50:50 H

2O:ACN (

Figure S5A). In addition, other solvents were evaluated under the optimal conditions, showing that the optimal solvent was ACN since there was still adsorption of TCE to the support (

Figure S5B).

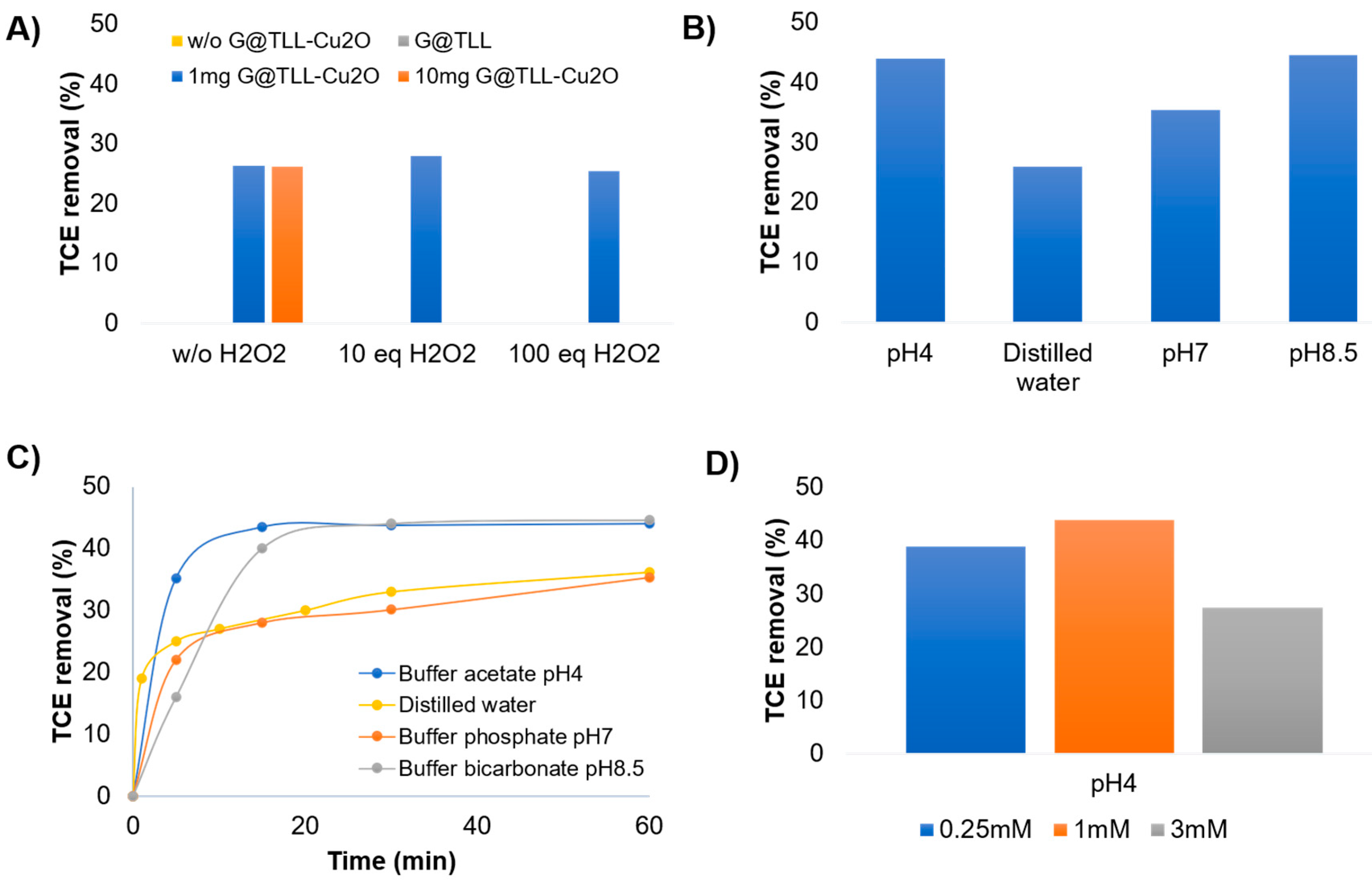

Thus, the reaction was carried out in aqueous media (50:50 H

2O:ACN) at 25ºC. Initially, no conversion was obtained without catalyst or exclusively using G@TLL (

Figure 2A). First, the degradation of TCE (1mM) was studied with 1mg of

G@TLL-Cu2O hybrid (

Figure 2A). TCE at 27% (35.5mg/L) was degraded in 60 min without the production of toxic by-products (1,1-DCE and VC). To try to improve the degradation, the amount of catalyst was increased to 10 mg, although no changes were observed. Therefore, different amounts of a green oxidant such as H

2O

2 (33% v/v) were evaluated, and again no significant differences were observed. This shows that the process is not a Fenton process.

To evaluate the effects of pH on the catalytic efficiency of

G@TLL-Cu2O in TCE degradation, four solutions with different pH values were studied, buffer sodium acetate pH4, distilled water, buffer sodium phosphate pH7, and buffer sodium bicarbonate pH8.5 (

Figure 2B). An increasing trend was observed as we increased the pH, obtaining a maximum degradation value of 44.5% (58.5mg/L) at pH 8.5. However, at pH 4, a lower pH than distilled water, TCE degradation was similar to pH 8.5. Furthermore, the TCE degradation profile was analyzed for these studies, demonstrating a clear rapid trend of TCE elimination in the first 5 min in the case of pH 4. At higher pHs the tendency in the first 5 min was slower (

Figure 2C). At this point, the evaluation of the increase and decrease of the initial concentration of TCE was carried out (

Figure 2D), where 3mM and 0.25mM of initial TCE were evaluated compared to the previous concentration already studied (1mM), all at pH4. In this case it was observed that by decreasing the amount of initial TCE the conversion was similar while when we increased the amount of initial TCE 3 times, the degradation decreases by half (

Figure 2D). Therefore, the optimal amount of starting TCE was determined to be 1mM. Therefore, the best conditions for direct degradation of TCE by the

G@TLL-Cu2O hybrid were 1 mM of TCE, 1 mg catalyst, in 50:50 ACN: pH4 acetate buffer without H

2O

2 (

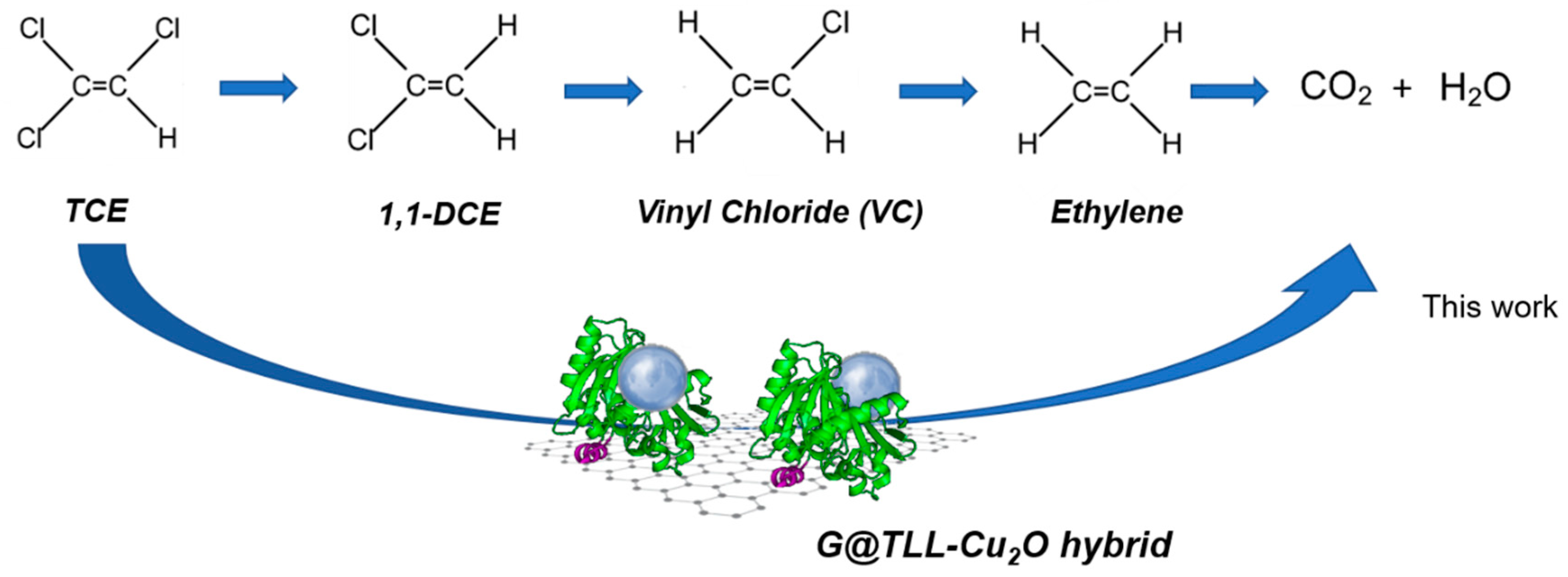

Scheme 1).

Finally, a comparison, in TCE degradation at pH 4, was made between the

G@TLL-Cu2O and non-supported TLL-Cu

2O (See Supplementary information) (

Figure S6), to evaluate the advantage of the

in-situ formation of Cu

2O nanoparticles on the immobilized derivative where the enzyme is fixed to graphene in open conformation, homogeneously distributed, and not in an aggregated form as exits in TLL-Cu

2O hybrid.

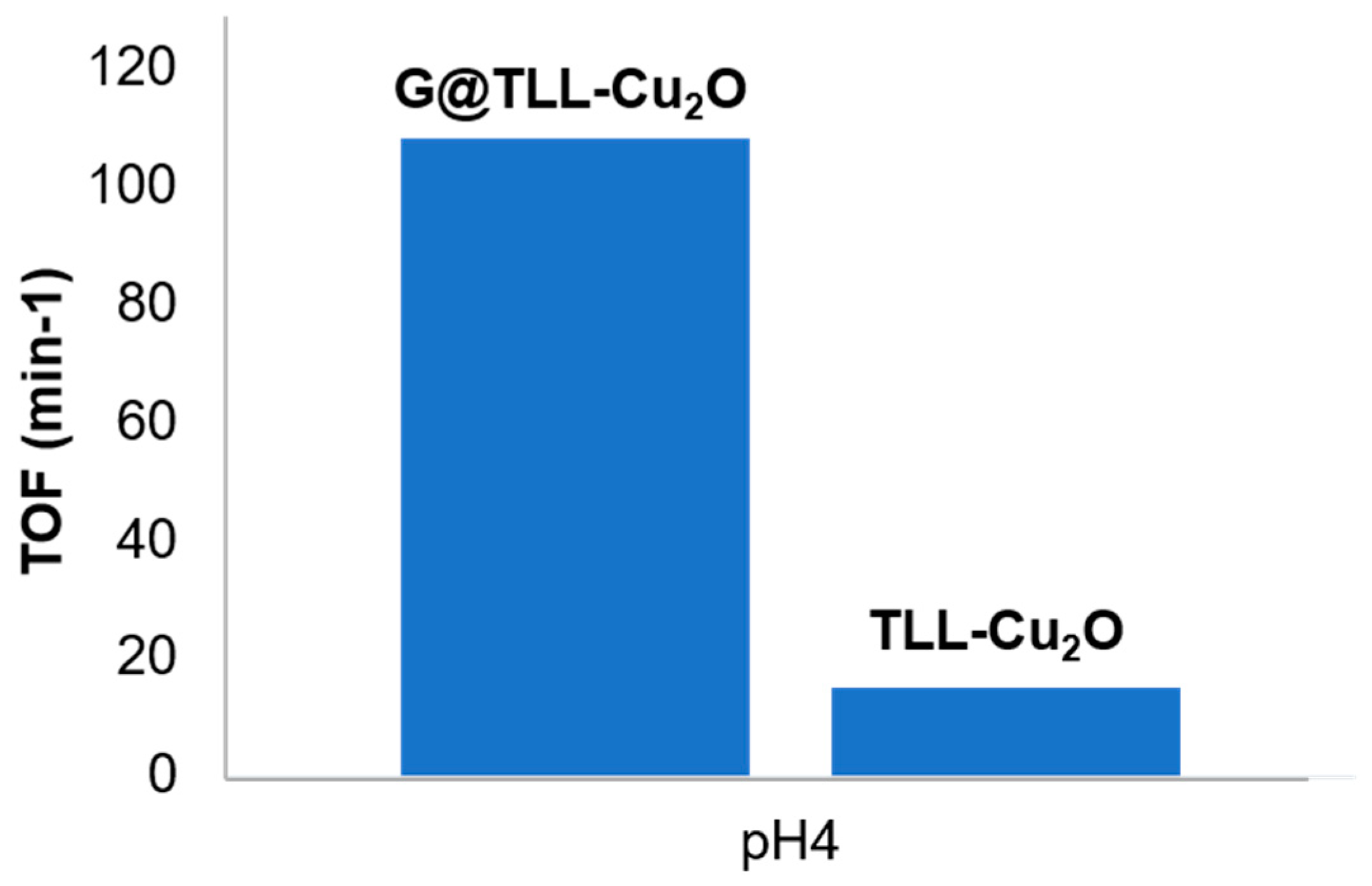

Figure 3 shows almost 8 times more efficiency for

G@TLL-Cu2O, with a TOF value of 109 min

-1 compared to 14.9 min

-1 for TLL-Cu

2O.

3.3. Rhodamine B (RhB) Degradation Catalyzed by G@TLL-Cu2O Hybrid

For the degradation of rhodamine B, firstly the adsorption of RhB to G@TLL was also studied. The optimal conditions to avoid any unspecific adsorption of compound to graphene were 50:50 ACN:H

2O (data not shown). The effects of several factors, such as the amount of hybrid, the amount of the green oxidant (H

2O

2) and the pH value of the reaction solution on the degradation of RhB were studied (

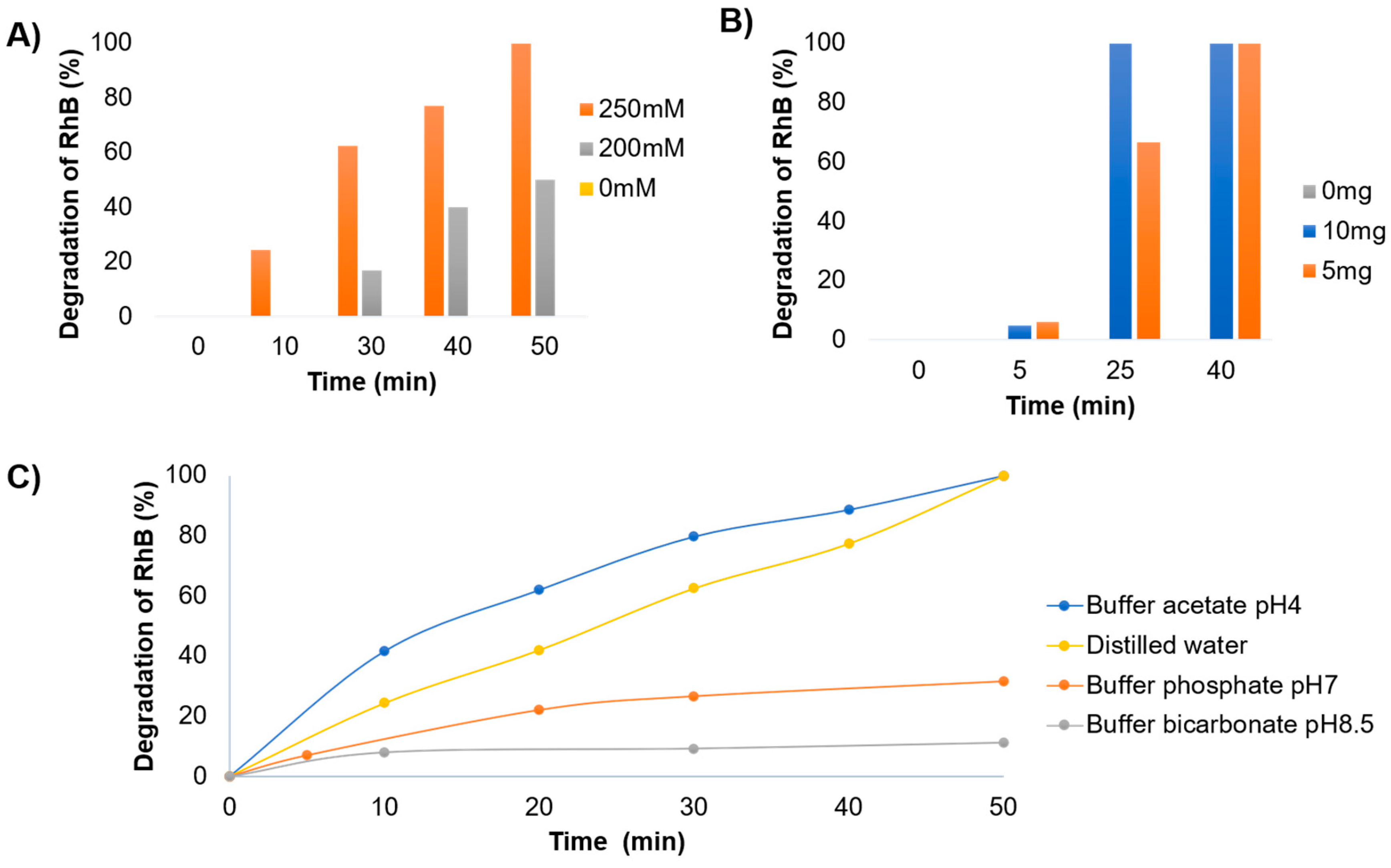

Figure 4).

Initially, the amount of H

2O

2 was studied in a range from 0 mM to 250 mM (

Figure 4A and

Figure S7). Here it is shown that at least 250 mM was necessary to complete degradation of RhB in 50 min. If we observe the result with 200 mM a clear influence on the degradation is observed since the drop in it is 50%. It was also tested with 500 mM H

2O

2 obtaining similar results than using 250 mM (data not shown). Then, the effect of the amount of

G@TLL-Cu2O hybrid was evaluated at 250 mM of H

2O

2 (

Figure 4B and

Figure S8). In this case, complete degradation was achieved after 25 min incubation using 10 mg, with a 60% using 5 mg of catalyst.

Finally, the ionic strength of the medium was evaluated by combining ACN and several buffers at different pH (50:50), these being acetate buffer pH4, distilled water, phosphate buffer pH7, and bicarbonate buffer pH8.5 (

Figure 4C and

Figure S9). All of them were studied without catalyst and no effect was observed (data not shown). The results showed a clear effect of pH in the degradation speed, where degradation is higher from basic to acidic media, being the best results at pH 4. A catalytic Fenton process of Cu is taking place, and OH· radicals in the medium are more active at lower pHs [

29].

Therefore, the best conditions obtained were 5 mg of catalyst, 250 mM H

2O

2 in an ACN medium: pH 4 acetate buffer (50:50) for a complete degradation of RhB (

Scheme 2) in less toxic products as similar to recently reported [

33].

To assess the advantage of this catalyst material, where synthesis and application were performed under very mild conditions, a comparison was made with other reported RhB catalytic degradation (

Table 1). Most of the systems based on Cu

2O nanoparticles published in the literature use high power ultraviolet light and visible light lamps. The first advantage was that the catalyst developed in this work was able to carry out RhB degradation in natural light. On the other hand, it was the only one capable of reaching 100% degradation in less than 1h, those described in

Table 1 need more than 1h or even 4h with an initial amount of RhB up to 10 times less than the system developed in this work. Therefore, it can be seen how the best result corresponds to this work, since it was able to degrade 48mg/L in 50min under standard conditions in natural light.

4. Conclusions

A heterogenous lipase-CuNPs hybrid catalysts were synthesized. Thermomyces lanuginosus lipase (TLL) was immobilized on a biographene preparation, and this immobilized preparation was used as solid-phase scaffold to the in-situ fabrication of Cu2O nanoparticles induced by lipases molecules creating successful G@TLL-Cu2O hybrid. The formation of Cu2ONPs was demonstrated by XRD and XPS where it was seen that it was the majority species. The TEM microscopy showed that the Cu2ONPs were homogeneously distributed over the G@TLL surface with sizes of 53nm and 165nm.

G@TLL-Cu2O hybrid was successfully used in the direct degradation of trichlorethylene (TCE), a toxic organic chloride. 60 ppm of TCE was degraded in 60 min at pH 4 in aqueous solution and room temperature without formation of other toxic by-products. In addition, a TOF value of 7.5 times higher than the unsupported counterpart (TLL-Cu2O) was obtained, demonstrating the improvement of the catalytic efficiency of the solid phase system. In addition, another toxic organic compound was evaluated, Rhodamine B (RhB). The hybrid presented an excellent catalytic performance for the degradation of RhB obtaining a complete degradation (48ppm) in 50 min in aqueous solution and at room temperature and with the presence of a green oxidant such as H2O2 by a Fenton process.

These excellent results in degradation processes of toxic organic compounds open up potential applications in the field of energy and the environment. Specifically, in water treatment systems, water remediation avoiding exposure to said pollutants to human health, in addition to the global ecological problem.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) (projects PIE 201980E08). The authors thank Dr. Martinez from Novozymes for the gift of TLL.

References

- S. Bagheri, A. Termehyousefi, T.O. Do. Photocatalytic pathway toward degradation of environmental pharmaceutical pollutants: structure, kinetics and mechanism approach. Catal. Sci. Technol. 7 (2017) 4548–4569. [CrossRef]

- M. Iqbal, J.H. Syed, K. Breivik, M.J.I. Chaudhry, J. Li, G. Zhang, R.N. Malik. E-waste driven pollution in Pakistan: the first evidence of environmental and human exposure to flame retardants (FRs) in Karachi City. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51 (2017) 13895–13905. [CrossRef]

- B. Grizzetti, A. Pistocchi, C. Liquete. Human pressures and ecological status of European rivers. Sci. Rep. 7 (2017) 205. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yu, L. Zhou, W. Zhou. Decoupling environmental pressure from economic growth on city level: the case study of Chongqing in China. Ecol. Indicat. 75 (2017) 27–35. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, T.X. Zheng, Y.B. Hua. Delta manganese dioxide nanosheets decorated magnesium wire for the degradation of methyl orange. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 490 (2017) 226–232. [CrossRef]

- D. Xu, H. Ma. Degradation of rhodamine B in water by ultrasound-assisted TiO2 photocatalysis. J. Clean. Prod. 313 (2021) 127758. [CrossRef]

- J. Ambigadevi, P. S. Kumar, D. V. N. Vo, S. H. Haran, T. S. Raghavan. Recent developments in photocatalytic remediation of textile effluent using semiconductor based nanostructured catalyst: a review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9 (2021) 104881. [CrossRef]

- Y.T. Lin, C.J. Liang, C.W. Yu. Trichloroethylene degradation by various forms of iron activated persulfate oxidation with or without the assistance of ascorbic acid. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55 (2016) 2302–2308. [CrossRef]

- X.L. Wu, X.G. Gu, S.G. Lu, Z.F. Qiu, Q. Sui, X.K. Zang, Z.W. Miao, M.H. Xu, M. Danish. Accelerated degradation of tetrachloroethylene by Fe(II) activated persulfate process with hydroxylamine for enhancing Fe(II) regeneration, J. Chem. Technol. Biot. 91 (2016) 1280–1289. [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans;World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Edition of the Drinking Water Standards and Health Advisories; EPA 822-R-18-001; EPA Office of Water: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Wang, Zhenjun. State-of-the-art on the development of ultrasonic equipment and key problems of ultrasonic oil production technique for EOR in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82 (2018) 2401–2407. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zhenjun. Research on removing reservoir core water sensitivity using the method of ultrasound-chemical agent for enhanced oil recovery. Ultrason. Sonochem. 42 (2018) 754–758. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yao, M.X. Sun, X.J. Yuan. One-step hydrothermal synthesis of N/Ti3+ co-doping multiphasic TiO2/BiOBr rheteojunctions towards enhanced sonocatalytic performance. Ultrason. Sonochem. 49 (2018) 69–78. [CrossRef]

- N. Birjandi, H. Younesi, N. Bahramifar, S. Ghafari, A.A. Zinatizadeh, S. Sethupathi. Optimization of coagulation-flocculation treatment on paper-recycling wastewater: application of response surface methodology, J. Environ. Sci. Health A Tox. Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 48 (2013) 1573–1582. [CrossRef]

- P.S. Zhong, N. Widjojo, T.-S. Chung, M. Weber, C. Maletzko, Positively charged nanofiltration (NF)membranes via UV grafting on sulfonated polyphenylenesulfone (sPPSU) for effective removal of textile dyes from wastewater, J. Membr. Sci. 417 (2012) 52–60. [CrossRef]

- D. Charumathi, N. Das, Packed bed column studies for the removal of synthetic dyes from textile wastewater using immobilised dead C. tropicalis, Desalination 285 (2012) 22–30. [CrossRef]

- D. Chen, Y. Li, J. Zhang,W. Li, J. Zhou, L. Shao, G. Qian, Efficient removal of dyes by a novel magnetic Fe3O4/ZnCr-layered double hydroxide adsorbent from heavy metal wastewater, J. Hazard. Mater. 243 (2012) 152–160. [CrossRef]

- N. Losada-García, A. Rodríguez-Otero, J. M. Palomo. Tailorable synthesis of heterogeneous enzyme–copper nanobiohybrids and their application in the selective oxidation of benzene to phenol. Catal. Sci. Technol. 10 (2020) 196-206. [CrossRef]

- G. Dinda, D. Halder, C. Vazquez-Vazquez, M.A. Lopez-Quintela, A. Mitra, Green synthesis of copper nanoparticles and their antibacterial property, J. Surf. Sci. Technol. 31 (2015) 117–122. [CrossRef]

- H.X. Li, J.X. Zhao, R.N. Shi, P.P. Hao, S.S. Liu, Z. Li, J. Ren, Remarkable activity of nitrogen-doped hollow carbon spheres encapsulated Cu on synthesis of dimethyl carbonate: role of effective nitrogen, Appl. Surf. Sci. 436 (2018) 803–813. [CrossRef]

- R.N. Shi, J. Wang, J.X. Zhao, S.S. Liu, P.P. Hao, Z. Li, J. Ren, Cu nanoparticles encapsulated with hollow carbon spheres for methanol oxidative carbonylation: tuning of the catalytic properties by particle size control, Appl. Surf. Sci. 459 (2018) 707–715. [CrossRef]

- A. Chinnappan, J.K.Y. Lee, W.A.D.M. Jayathilaka, S. Ramakrishna, Fabrication of MWCNT/Cu nanofibers via electrospinning method and analysis of their electrical conductivity by four-probe method, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 43 (2018) 721–729. [CrossRef]

- P. Deka, B.J. Borah, H. Saikia, P. Bharali, Cu-based nanoparticles as emerging environmental catalysts, Chem. Rec. 19 (2019) 462–473. [CrossRef]

- Y. Seo, J. Hwang, E. Lee, Y.J. Kim, K. Lee, C. Park, Y. Choi, H. Jeon, J. Choi, Engineering copper nanoparticles synthesized on the surface of carbon nanotubes for anti-microbial and anti-biofilm applications, Nanoscale 10 (2018) 15529–15544. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xiong, L.Y. Che, Z.Y. Fu, P.Y. Ma, Preparation of Cu x O/C composite derived from Cu-MOFs as Fenton-like catalyst by two-step calcination strategy, Adv. Powder Technol. 29 (2018) 1331–1338. [CrossRef]

- N. Losada-Garcia, A. Berenguer-Murcia, D. Cazorla-Amorós, J. M. Palomo. Efficient production of multi-layer graphene from graphite flakes in water by lipase-graphene sheets conjugation. Nanomaterials, 9 (2019) 1344. [CrossRef]

- G. Fernández-Lorente, Z. Cabrera, C. Godoy, R. Fernandez-Lafuente, J. M. Palomo, J.M. Guisan. Process Biochem. 43 (2008) 1061–1067. [CrossRef]

- D. Wang, J. Zou, H. Cai, Y. Huang, F. Li, Q. Cheng. Effective degradation of Orange G and Rhodamine B by alkali-activated hydrogen peroxide: roles of HO2− and O2·−. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26 (2019)1445–1454. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, S. Zhai, M. Wang, H. Ji, L. He, C. Ye, W. Chuanbin, F. Shaoming, H. Zhang. Photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B by using a nanocomposite of cuprous oxide, three-dimensional reduced graphene oxide, and nanochitosan prepared via one-pot synthesis. J. Alloys Compd. 659 (2016) 101-111. [CrossRef]

- C. Yang, J. Wang, L. Mei, X. Wang. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B by Cu2O coated silicon nanowire arrays in presence of H2O2. J Mater Sci Technol. 30 (2014) 1124-1129. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zheng, Z. Wang, F. Peng, A. Wang, X. Cai, L. Fu. Growth of Cu2O nanoparticle on reduced graphene sheets with high photocatalytic activity for degradation of Rhodamine B. Fuller. Nanotub 24 (2016) 149-153. [CrossRef]

- M. V. Kangralkar, V. A. Kangralkar, J. Manjanna. Adsorption of Cr (VI) and photodegradation of rhodamine b, rose bengal and methyl red on Cu2O nanoparticles. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 15 (2021) 100417. [CrossRef]

- E. Shayegan Mehr, M. Sorbiun, A. Ramazani, S. Taghavi Fardood. Plant-mediated synthesis of zinc oxide and copper oxide nanoparticles by using ferulago angulata (schlecht) boiss extract and comparison of their photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B (RhB) under visible light irradiation. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 29 (2018) 1333-1340. [CrossRef]

- M. Tariq, M. Muhammad, J. Khan, A. Raziq, M. K. Uddin, A. Niaz, S. S. Ahmed, A. Rahim. Removal of Rhodamine B dye from aqueous solutions using photo-Fenton processes and novel Ni-Cu@ MWCNTs photocatalyst. J. Mol. Liq. 312 (2020) 113399. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).