1. Introduction

The behavior of gases under gravitational fields is traditionally described through classical Newtonian gravity and kinetic theory principles, where intermolecular forces in the gaseous state are commonly assumed to be negligible. Under such approximations, buoyancy and thermal expansion are sufficient to explain most vertical gas and vapor motions observed in the atmosphere and engineered systems.

However, certain laboratory and natural observations reported in a series of previous studies [

1,

2,

3,

4] have indicated upward movement of matter that may not be fully accounted for by standard buoyancy and diffusion alone. The findings forwarded in this paper, together with experimental results [

2,

3,

4] from previous studies, motivated the development of an analytical approach that considers potential, energy-dependent interactions influencing gas behavior in gravitational environments.

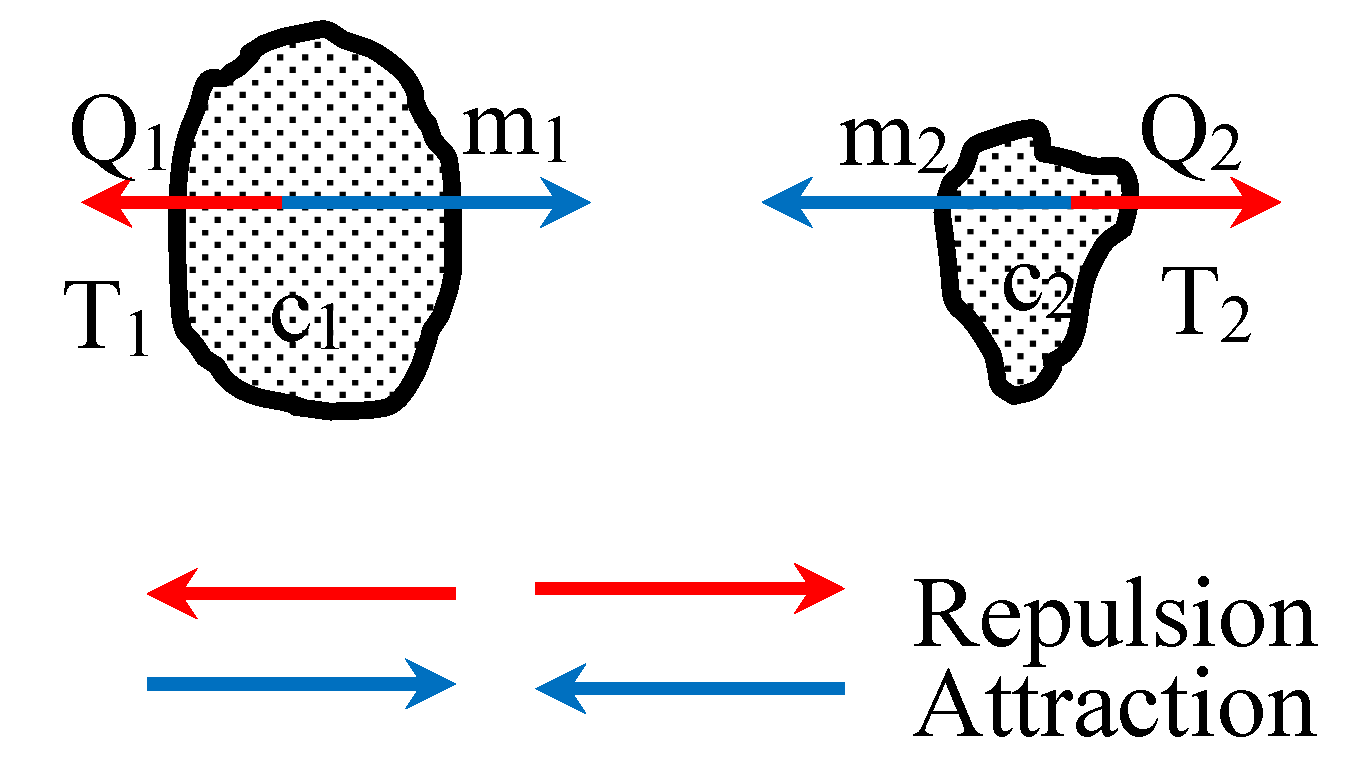

This study of gravitation forces in gases has been conducted modelling them as two distinct forces of repulsion and attraction acting on gaseous matter. The gravitational repulsion concept presented in the series of publications [

1,

2,

3,

4] emanating from this research program, are based on experimental observations and natural phenomena; making neither abstruse assumptions nor explanations. The model has been validated using experimentally determined and established data utilized in practical thermodynamic applications of mechanical engineering industries. It is a self-standing model, which requires no fitting into existing models. The presented alternative model could more effectively describe the nature of the Universe at both micro and macro levels.

The current understanding of fundamental interactions - gravitational, electromagnetic, and the strong and weak nuclear forces [

Table S1 in supplementary information] does not include any explicitly temperature-dependent

(hence energy dependent) component. Yet, many macroscopic physical phenomena such as pressure development, phase change behavior, and thermal expansion are inherently linked to temperature which is a manifestation of the thermal energy content. This raises a scientific question of whether temperature-dependent effects could contribute in subtle ways to the motion and distribution of matter under gravity.

Historical discussions of

non-attractive gravitational effects can be found dating back to Newton’s Principia [

5], published by Isaac Newton in 1687; see Prepositions XLIII-XLV of Book 1, pp171-182, and more recent theoretical explorations have occasionally entertained similar concepts [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Additionally, recent discussions suggest that some interstellar objects, such as comets (e.g., 1I/ʻOumuamua and 3I/ATLAS), have exhibited

non-gravitational accelerations that are not fully explained within the standard fundamental interaction models.

Although many natural and cosmological phenomena—such as pressure, expansion, and phase transitions - depend on temperature, which reflects the system’s thermal energy content, none of the four fundamental forces in classical theory are considered to be directly dependent on thermal energy or temperature. As presented below, and supported by both analytical and experimental evidence, a gravitational repulsive force dependent on thermal energy offers a potential mechanism to bridge the critical gap between energy and the fundamental forces.

In some literature [

7,

8,

9,

10], the gravitational repulsion force is referred to as the antigravitational force. Therefore, we use both these words in our text to mean the same concept.

Presenting a new scientific revelation that fundamentally challenges our understanding of the Universe, requires examining the foundations of our present understanding, viz., Newtonian and Einsteinian gravity concepts. The Author would, for the benefit of those interested in contextual knowledge, in the supplementary information (supplementary information: Section A), briefly note the following:

Newtonian and Einsteinian gravity concepts, thus highlighting foundations of our present understanding

Early notions of the gravitational repulsion force and its recent revelations

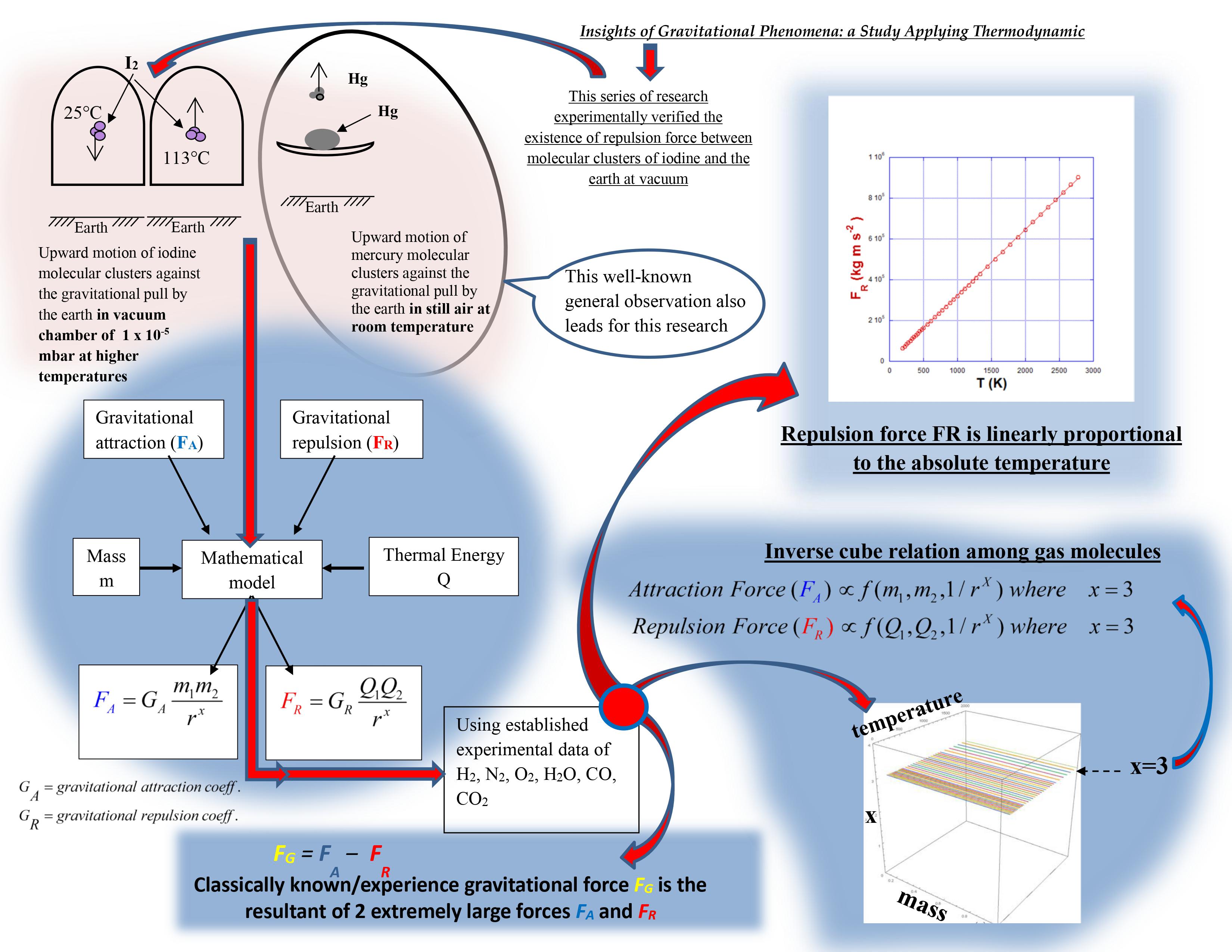

1.1. Motivation from Recent Experimental Observations; the Gravitational Repulsion Force

Experiments previously reported by the author [

1,

2,

3,

4] demonstrated displacement against the gravitational attraction in systems such as iodine vapor [

3] (briefly presented in Section C) in a partial vacuum and suspended water droplets [

2,

4] in air.

The observations suggested that the magnitude of these motions against the gravitational attraction scaled with the internal thermal energy of the observed material. Additional experimental work highlighted upward tendencies in mercury molecular clusters [

11], despite their significantly higher density compared to ambient air at room temperature.

These findings indicate a possible non-classical contribution to motions against the gravitational attraction that warrants deeper investigation. In particular, an improved theoretical description may support better interpretation of processes involving condensation, aerosol aggregation, and accumulative (flocking together) nature of clouds - phenomena occurring both microscopically and macroscopically.

The discussion thus far suggests that a broader conceptual framework is required beyond the conventional gravitational models, such as Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation and Einstein’s Einstein Field Equations. We also need to revisiting the key idealized assumptions of the kinetic theory of gases, as discussed in the following section. Our aim is to develop a relationship that offers a deeper understanding of gas-molecule behavior under a proposed repulsive interaction acting on matter.

1.2. Revisiting Key Ideal Gas Theory Assumptions

To formulate a framework capable of evaluating these observations, it is important to revisit certain core assumptions [

12] used in classical gas models. The kinetic theory of gases typically assumes:

- (i)

negligible intermolecular forces

- (ii)

perfectly elastic collisions

- (iii)

negligible molecular volume

In deriving the ideal gas equation, one of the most fundamental forces—gravitational interaction among matter - has been largely overlooked, both in terms of molecule–molecule interactions and the interaction between gas molecules and the Earth. Such a sweeping assumption is difficult to justify within the framework of fundamental science. Even though a gas molecule contains only a minute amount of mass, it is still subject to gravitational forces exerted by surrounding matter. Therefore, neglecting gravitational interactions on gas molecules, regardless of the scale of the interacting bodies, may not be a prudent assumption.

It is well established that Earth’s atmosphere is retained due to the planet’s gravitational attraction, which constitutes the dominant force acting on air molecules. Mars, despite its weaker gravitational field, maintains a thin atmosphere of about 0.6% (610 Pa) of Earth’s atmospheric pressure [

13]. Conversely, planets with stronger gravitational fields, such as Jupiter and Saturn, possess dense atmospheres capable of retaining even light gases like hydrogen and helium [

14].

Another assumption in kinetic theory that prompts scrutiny is the notion of “perfectly elastic collisions” between gas molecules and container walls when defining pressure under static conditions. This definition becomes problematic when the wall itself moves under the influence of pressure. Any displacement of the wall requires the transfer of momentum (energy) from gas molecules, which contradicts the premise of a perfectly elastic collision. The mass of an average air molecule (~4.8 × 10⁻²⁶ kg) is negligible compared with the mass of a rigid wall, making the idea that gas-molecule impacts can realistically move such a massive object questionable under Newton’s Third Law. Furthermore, the detailed mechanism by which momentum or energy is transferred through fundamental forces remains unclear.

The postulates of the kinetic molecular theory also neglect the finite volume occupied by gas molecules. Real gases, however, exhibit significant deviations from ideal behavior [

15], as reflected in models such as the van der Waals equation. A brief discussion on real-gas behavior is included in Supplementary Information – Section B.

Rather than relying on assumptions with such limitations, this research program considers experimentally established forces. The following section highlights several previous experiments conducted in this program, in which a Gravitational Repulsion force was discovered alongside the well-known Gravitational Attraction force.

4. Quantitative Evaluation of Parameters x, y, GR, GA, FR and FA Based on Thermodynamic Properties of Gas:

This section aims to provide a qualitative and quantitative evaluation of the proposed interaction model as applied to gaseous matter. Using established thermodynamic properties, the combined effects of the hypothesized thermal-energy-dependent repulsive force and the conventional mass-dependent attractive force are explored. Nitrogen gas is selected as a representative working medium due to the extensive availability of verified property datasets.

Published experimental data for nitrogen thermodynamic properties [

22] (see Supplementary Information, SF1) were applied to Equations (8) - (12) to compute values of the exponent

x, temperature exponent

y, gravitational repulsion coefficient

GR, gravitational attraction coefficient

GA, and the corresponding force magnitudes

FR and

FA. Nitrogen properties were evaluated across the temperature range 146.65–2888.9 K using a molecular mass of 28.016×1.66054×10

−27 kg. Specific heats at constant volume

cv and constant pressure

cp were extracted for each condition. Full computational steps are available in Supplementary Information, Section E.

Based on this analysis, the following key results were established (see Supplementary Information, Section E.2):

The exponent x is equal to 3, independent of temperature and y

(Figure S4a, Supplementary Information Section E.2)

This suggests an inverse-cube spatial dependence, distinct from the inverse-square form of classical gravity. The implications are examined in the Discussion.

- 2.

The temperature exponent

y = 0.5 emerges as a characteristic value

(Figure S4b,c, Supplementary Information Section E.2)

This value yields stable and physically interpretable coefficients in the model.

- 3.

FR is linearly proportionate to temperature

T (Figure S4d)

This is consistent with the analytical form of Equation (2) and is aligned with the previously reported experimental observation [

2] that heated droplets exhibit increased suspension times in air - summarized in Ref. [

2], p.148:

In experiment 2, tf (time-of-fall) of a water-droplet in still air increases with the temperature of the droplet. That is: “The hotter the water-droplet, the slower it falls”.

- 4.

The

FR Vs

T relationship extrapolates close to the origin when

y ≈ 0.5

(Figure S7, Supplementary Information)

This suggests that at low thermal energy, the repulsive contribution approaches zero smoothly.

These computational outcomes are further interpreted in Supplementary Information, Section F, and key points are synthesized in the Discussion.

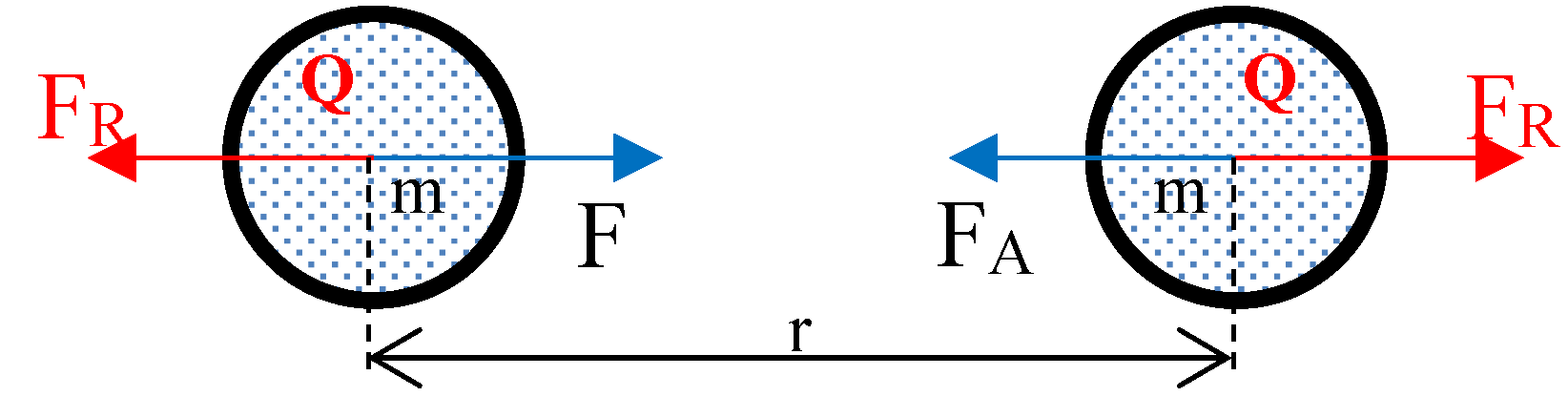

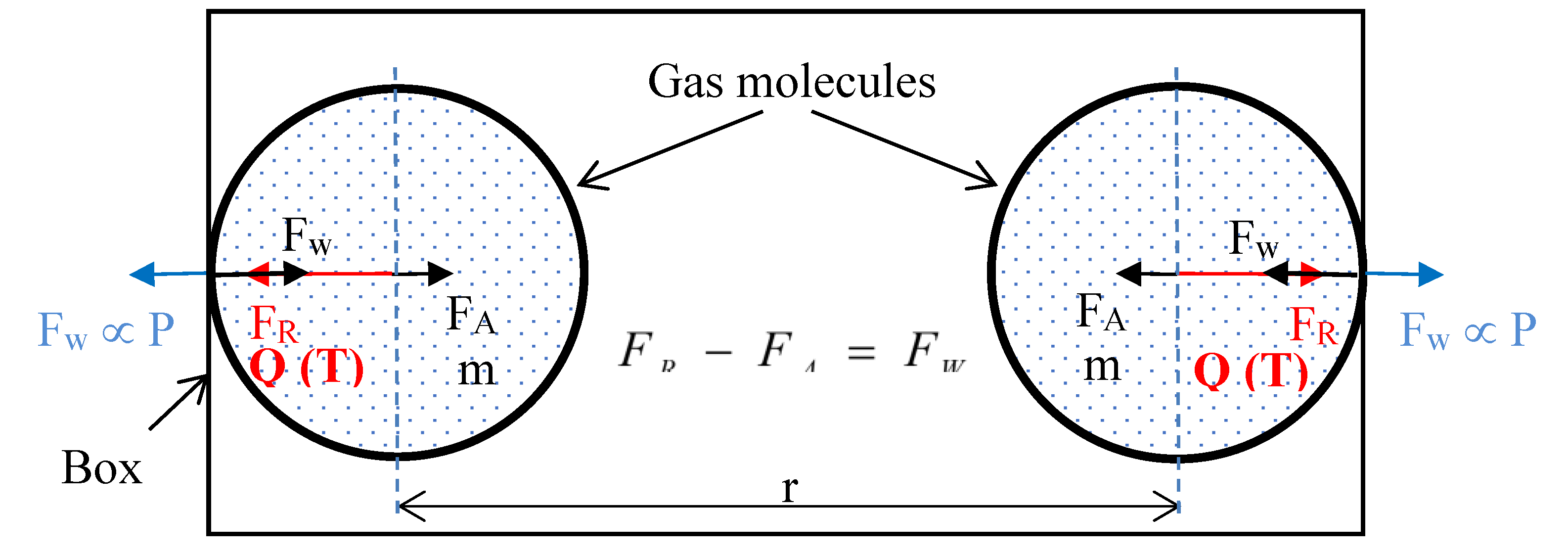

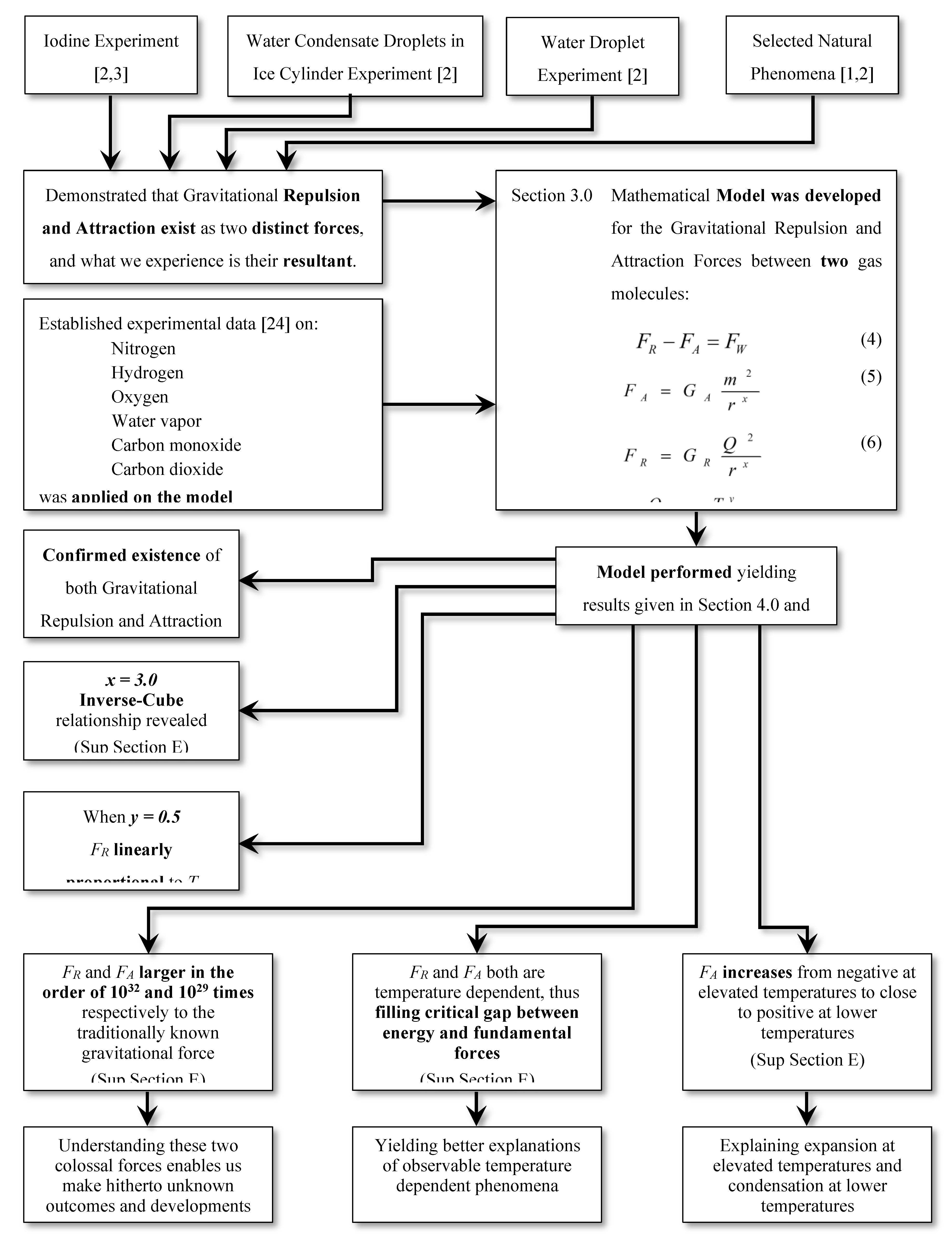

4.1. The Gist of the Model and the Outcomes:

An alternative framework describing thermal-energy-dependent repulsive interactions, coexisting with mass-dependent attraction between gaseous molecules, has been developed in

Section 3. The evaluation using thermodynamic properties of six common gases - nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, water vapor, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide - indicates that the model produces internally consistent and physically meaningful trends.

For reader clarity, the essential structure of the model and its main results are summarized schematically in

Figure 4.

5. Discussion

Certain observations in laboratory settings - such as the upward movement of heated iodine particles in vacuum, upward motion of mercury in room temperature and natural behavior of matter, for example condensation and aggregation of water droplets in clouds and accelerating expansion of the Universe, motivate continued examination of how energy, particularly thermal energy, which has been the focus of this research series, interacts with gravity [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Classical Newtonian gravity and General Relativity do not generally include thermal energy as a factor in gravitational interactions. Similarly, gravitational forces among gas molecules are traditionally neglected in kinetic theory and in derivations of the ideal gas law. These gaps suggest value in exploring alternative formulations that incorporate interactions between mass and energy, particularly thermal energy, which has been the focus of this research series.

The alternative model considering both gravitational repulsion and attraction, presented in this paper, is self-standing; independent of existing idealistic models. This model has been built without idealistic assumptions such as: “intermolecular force in gaseous state is zero”, “perfectly elastic collisions”, “consists of a large number of molecules”, “volume of the molecules is negligibly small” and so on. In fact, there are no idealistic assumptions involved in this model; hence it is closer to reality.

The entire mathematical model presented in this paper was derived considering the forces of gravitational repulsion and attraction between just two gaseous molecules; the basic building blocks of the gas. Force (net repulsive) between individual gas molecules represents the pressure in the system; a significant deviation from the kinetic theory’s concept of momentum transfer. Hence, pressure does not depend on the rate of change of momentum of a number of molecules in a certain mass or volume of the gas, as assumed in the kinetic theory in the derivation of the ideal gas equation. The two gaseous molecule model justifies that any small quantity of gas molecules would exhibit same pressure (independent of the tag of rate of change of momentum) as a large quantity at the same temperature and molecular number density. In short, even a small quantity of gas could produce the same pressure as a large quantity.

It should be noted that the above relationships (Equations S11, S12 and 8–12) are developed for the matter in the gaseous state. It is, hence, recommended that future research should focus on analysis of matter in other states, viz., solid, liquid and plasma.

The model has been validated using experimentally determined and established data [

22] utilized in practical thermodynamic applications of mechanical engineering industries. The data has been published in 1948, by Joseph Henry Keenan and Joseph Kaye. Applying these data to Equations 8-12, behavior of

x, GR,

GA,

FR and

FA with respect to

T and

y were derived and presented in 3D graphs (a), (b), (c), (d) and (e) in

Figure S4 in supplementary information (Section E2).

The result

x = 3.0 as presented in the 3D graph

Figure S4 (a) contributes new scientific information on distribution of gravitational force fields that fill up the volume in free space, at the length scale of intermolecular distances for gas molecules. The relationship of gravitational repulsion and attraction forces being inversely proportional to the cube of the distance, interprets the gravitational force distributions as volumetric or solid spherical distributions (

4/3 πr3) in free space, rather than the area or surface distributions (

4πr2) considered in the classical model. This is a significant departure from the Inverse-Square Law. Inverse-Square Law describes wave front propagation of energy. In contrast, force fields fill up volume in the free space. The volumetric distribution or fill-up the free space by the force is more appropriate in understanding; as a force field always exists in a 3D space rather than on a 2D surface.

In literature on force fields, the inverse proportionality to cube (Inverse-Cube Law) with the distance is not new. An extra force besides gravity, that is obeying the Inverse-Cube Law, has been mentioned in ‘Principia Mathematica’ [

5] published by Isaac Newton in 1687; see Prepositions XLIII-XLV of Book 1, pp171-182. It has also been demonstrated [

23] experimentally that, in magnetostatic fields where both poles geometrically coincide, attraction and repulsion forces obey the Inverse-Cube Law with the distance. Future research should focus on discerning where inverse proportionality to the cube of the distance is more appropriate in applications of fundamental physics.

The analysis presented in this paper signifies that y = 0.5 as a characteristic temperature exponent for all tested gases, is a very special value when considering behaviors of GR, GA, FR and FA. Most noteworthy points were that, for both cv and cp, when y ≈ 0.5:

Linear extrapolation of graphs FR vs. T crosses (0,0)

The attraction term, FA approaches zero from negative values as T approaches 0 K

This was found to be true for all gases considered: nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, water vapor, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide; yielding similar results irrespective of atomic mass m. How these results resonate with other empirically established models such as Boyle’s Law, Charles’ Law and Amontons’ Law/Gay-Lussac’s Law will be discussed in a future publication.

In the 3D graphs

Figure S4 (b) and (c), both Gravitational Repulsion Coefficient and Gravitational Attraction Coefficient appeared dependent on the temperature

T. This result is unexpected, as temperature dependency of

GA was not previously known. Further to that, as presented in 3D graphs

Figure S4 (d) and (e), both

FR and

FA are temperature dependent; being gravitational forces, they are fundamental interactions in nature. Significant departure from the existing knowledge is that, the four fundamental interactions (fundamental forces) in classical theory are not defined to be temperature dependent. Existing theories, nevertheless, state that increase of thermal energy increases the potential energy of the gas molecules; with no mention that a relationship exists between thermal energy (classically known as potential energy) and gravitational forces. Results showed that, increase of thermal energy increased repulsion (Equations 2 and 11) between gas molecules. See graphs of

FR vs.

T and

FA vs.

T, where, as

T increases:

That implies that thermal energy is directly proportional to the resultant of FR and FA, confirming the relationship between energy and fundamental forces. With this revelation, the critical gap between energy and fundamental forces has been filled. Fundamental forces could be more readily linked with observable temperature dependent phenomena (e.g.: pressure, expansion, and so on) in the nature/Universe; thus, enabling better explanations.

In the 3D graph

Figure S4 (d) (supplementary information (Section E2).), gravitational repulsion force appeared linearly proportionate to the temperature. This vindicated the experiment conducted in this research program by the Author, presented in paper [

2]. The said experiment demonstrated that the time-of-fall of water droplets is linearly proportionate to the temperature (

Figure S6 in supplementary information).

Negative values of

FA at elevated temperatures [

Figure S4 (e)], together with

FR, cause the gas to have only repulsive forces among molecules. This gives rise to the property that real gases expand infinitely as the available space increases. Such circumstances of all repulsive forces were observed in other gases studied (hydrogen, oxygen, water vapor, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide) as well (information available on request).

Analysis presented in this paper further shows that as temperature decreases, repulsion forces decrease and attraction forces increase (from negative at elevated temperatures to close to positive at lower temperatures) between gaseous molecules, thus causing aggregation of atoms/molecules together, i.e., causing condensation of the gas. This finding is significant in a context where exact fundamental mechanism of condensation has so far not been explained by classical theories.

This program of research has shown that, the so called ‘weak’ gravitational force (

Table S1 in supplementary information), is actually the resultant of two extremely large forces, i.e., gravitational repulsion and gravitational attraction, which distinctly act on matter. Newly determined gravitational repulsion and attraction forces between two nitrogen molecules at 305 K are in the order of 10

30 times (supplementary information: Section F) greater than the classically calculated gravitational attraction force. It thus reveals that gravitational repulsion and attraction forces in fact are of similar orders of magnitude as the other three forces in the nature.

Even though, gravitational repulsion and attraction forces are colossal, they are nearly equal, thus nearly in equilibrium in nature; hence always observed to be a weak force.

An experiment was referred to in Section 02, where heated iodine particles moved upwards in vacuum against the Earth’s gravitational pull. This is a groundbreaking experiment where the said phenomenon occurred in a situation where all factors which are believed to be causing the upward movement of particles in air against the gravitational pull, viz., buoyancy and convective forces, are eliminated by experimental design. Initially, at the room temperature (≈ 25°C), the iodine particles detached from the iodine sample moved downward under gravitational attraction force with the Earth, and deposited in the bottom part of the paper jacket. When the iodine sample was heated, the experiment revealed that iodine particles move against gravitational pull in the vacuum and deposited in the top part of the paper jacket. In electronic vacuum tubes (called electronic valves) also, evaporated tungsten and thorium particles from the filament moves upwards in the absence of air, despite the gravitational pull and the strong radial electric fields, and deposit at the top of the glass tube.

The above was a laboratory experiment at a micro scale. The antigravity concept could also be extended to macro level phenomena in the nature such as clouds and the accelerating expansion of the Universe. Review paper by the Author [

1] on the previous papers in this research program states:

In addition to attractive and repulsive forces of water-droplets of a cloud with earth, there exist attractive and repulsive forces among water droplets within the cloud. These forces acting inside the cloud explain the accumulative (flocking together) nature of the cloud which has not been explained by the classical theories. The equilibrium of these two forces will confine the droplets to a certain area as a floccule. The repulsiveness does not allow shrinking and finally collapsing the cloud while the attractive force keeps the droplets together without dispersion. [

1]

p4

The above is an ideal example where there is no net outward force (no net pressure exerted outward) among

flocculent water droplets. Water droplets behave as a flock under the equilibrium of gravitational repulsion and gravitational attraction forces. The paper [

2] dispelled the classical belief that clouds float due to convection currents, and showed that the force that holds the

flocculent water droplets up in the air is “antigravity”. Coexistence of repulsive and attractive forces considered in theoretical derivations presented in this paper are supported by the mechanism for existence of clouds deduced in the paper [

2].

Considering both gravitational repulsion and gravitational attraction on matter and filling the critical gap between energy and fundamental forces, opens the doors for more research enabling stronger scientific explanations of observable temperature dependent phenomena, e.g.:

Heavy gas molecules (such as CFC) in the upper atmosphere

Brownian Motion

Condensation/evaporation/sublimation

Expansion/contraction of gas/liquid/solid

and more

The concept of gravitational repulsion and gravitational attraction forces could be further applied at macro level to explain the accelerating expansion of the Universe. Even in our solar system:

… the distance of the Earth’s [sic] from the sun. Various measurements indicate that this distance (or at least the length of the Earth’s semimajor axis) is increasing at the rate of 15 cm per year (plus or minus 4 cm). [

24,

25]

Galaxies and other interstellar objects are not in a state of equilibrium as a result of increasing thermal energy content due to various reasons including atomic fission and fusion causing mass-energy conversion (

E = mc2). The effect of increasing thermal energy on (a) expanding gas, i.e., at the microscopic level, and (b) expanding universe [

1], i.e., at the macroscopic level, should be similar. Such mass-energy conversion has dual effects on equilibria in the Universe: (1) increasing thermal energy increases gravitational repulsion forces, while (2) decreasing mass decreases gravitational attraction forces. Gravitational repulsion forces, hence, keep exceeding gravitational attraction forces, thus causing outward expansion of the Universe with acceleration [

26]. In essence, gravitational repulsion is a significant force between gas molecules (microscopic level), and could be generalized to explain macroscopic level phenomena, e.g., behavior of the universe [

27,

28,

29,

30], existence of clouds [

1].

In conclusion, the analytical framework developed in this study demonstrates that intermolecular forces in gases exhibit a measurable and systematic dependence on thermal conditions, extending beyond the assumptions of purely temperature-independent interactions. By grounding the analysis in experimental evidence, the results highlight the necessity of incorporating thermal energy as an active parameter influencing molecular behavior, rather than treating it solely as a statistical descriptor. This thermal-dependent perspective provides a more comprehensive understanding of gas-phase interactions, offers improved consistency with observed non-ideal behavior, and opens new avenues for refining existing models of molecular dynamics. Ultimately, the approach presented here lays a foundation for future experimental and theoretical investigations aimed at unifying thermal effects with intermolecular force descriptions in gaseous systems.