1. Introduction

The ΛCDM model’s remarkable success is now challenged by statistically significant tensions, most notably the 5σ discrepancy in the Hubble constant H

0 [

1] and anomalies in the late-time growth of structure [

2]. While many solutions propose extensions within the expanding universe framework (e.g., early dark energy, modified gravity), the persistence of these tensions suggests a potential need to revisit more fundamental premises [

3,

4,

5,

6].

The Dead Universe Theory (DUT) offers a paradigm shift by attributing the observed recession of galaxies not to the expansion of space itself, but to the thermodynamic deformation of a spacetime continuum. In this view, the luminous sector we observe is embedded in a vast, thermodynamically exhausted substrate. This substrate, which we term the Dead Universe or dark continuum, is not a separate cosmos but the extended, fossilized gravitational structure of a prior cosmological phase. It corresponds to the global dark thermodynamic background permeating the observable universe, rather than to individual collapsed objects within it.

The Dead Universe must therefore be distinguished from local dead structures formed inside the observable luminous sector. Collapsed remnants such as supermassive black holes, dark nebulae, and other degenerate masses are products of the ongoing thermodynamic evolution of the luminous universe. They are embedded within the dark continuum and contribute to its gravitational inventory, but they do not constitute the Dead Universe itself. The Dead Universe is the underlying continuum; these objects are localized excitations and decay products within it.

The luminous universe is thus a local anomaly within this larger, colder, and older gravitational architecture. The apparent acceleration is a kinematic effect driven by residual entropy gradients within this substrate. This work presents the complete geometric and field-theoretic formulation of this idea, moving from a phenomenological analogy to a formal tensor-based theory. Crucially, the tensor formulation of DUT is mathematically invariant under reparametrization; any model utilizing the same fundamental thermodynamic degrees of freedom is mathematically isomorphic to the canonical DUT architecture.

2. Geometric Framework: The Spacetime Continuum

We model the dark continuum as a four-dimensional, non-equilibrium thermodynamic medium with viscoelastic properties. The distinction from a purely elastic medium is essential: a viscoelastic material exhibits both elastic energy storage and viscous dissipation, allowing irreversible deformation under stress. In the DUT framework, spacetime behaves as such a continuum.

Bound luminous structures (e.g., galaxies) act as embedded inhomogeneities within this medium. The continuum itself corresponds to the thermodynamically exhausted, non-radiating substrate identified with the “Dead Universe,” extending beyond the observable luminous sector. High-precision weak gravitational lensing maps that trace the distribution of dark matter are interpreted, within DUT, as measurements of density perturbations and structural morphology of this underlying continuum and its collapsed remnants.

Global gravitational exhaustion generates a non-uniform stress field within the medium. The viscous component enables irreversible, entropy-increasing flow, while the elastic component transmits stress across large scales. The resulting deformation is permanent: the continuum evolves monotonically toward thermodynamic exhaustion and does not relax to a prior configuration.

This produces a differential kinematic effect. Although the continuum itself does not undergo global metric expansion, the deformation field increases the relative separation between embedded luminous structures. The situation is analogous to a viscoelastic material in which internal flow causes inclusions to separate even without net volumetric expansion. The fundamental dynamical variable describing this process is the entropic deformation tensor Ξ₍μν₎.

2.1. Variational Origin and Field Equations

Starting from the action established in the foundational DUT preprint [

7],

variation with respect to the metric g_μν yields the master field equation. For the purpose of a clean geometric interpretation, the contributions from the entropic scalar field φ and its non-minimal coupling can be collected into an effective tensor. This tensor, Ξ_μν, is not an ad hoc addition but emerges necessarily from the variation of the non-minimally coupled thermodynamic action. We define this object as:

where S is an effective entropy density field constructed as a scalar functional of φ and its gradients, and κ is a dimensionless coupling constant. In the dynamics of the late-time attractor, this variational coupling κ flows dynamically toward the observable growth index γ, which becomes a universal constant fixed by the thermodynamic attractor. This flow is a consequence of the system’s evolution toward its thermodynamic fixed point, not an arbitrary identification. This construction ensures Ξ_μν is covariantly conserved on-shell, consistent with the Bianchi identity and diffeomorphism invariance of the action, i.e., when the entropy field S satisfies its Euler–Lagrange equation [

8,

9].

The generalized Einstein field equations for the DUT continuum are therefore:

Equation (1) is the cornerstone of the formulation. The tensor Ξ_μν acts as a dynamical curvature source, replacing the ad hoc cosmological constant Λ g_μν with a term rooted in the continuum’s thermodynamics [

10,

11].

2.2. Viscoelastic Partition of Stress-Energy

The full effective stress-energy tensor governing the continuum’s dynamics admits a natural partition informed by non-equilibrium continuum mechanics [

12,

13]

:

Here:

T_μν^(matter) is the standard stress-energy of baryonic and dark matter.

Σ_μν^(visc) represents dissipative stresses, obeying a relativistic Maxwell-type constitutive relation Σ̇_μν ~ ε̇_μν - Σ_μν/τ, where ε̇_μν = ∇

_⟨

μ u_ν⟩

is the strain rate tensor and τ a relaxation time. This term provides the formal basis for so-called “Viscous Gravity” models [

14,

15]

.

Ξ_μν^(ent) is the entropic deformation tensor from Eq. (1), providing the non-dissipative driving force for deformation.

This partition clarifies the physical picture: matter responds to gravity, viscous stresses dampen deformation, and entropic gradients drive it. Phenomenological constructs like “Dark Fluid” are encompassed by this precise partition of the total stress-energy content [

16,

17]

.

3. Cosmological Dynamics and Key Predictions

3.1. Redshift from Deformation

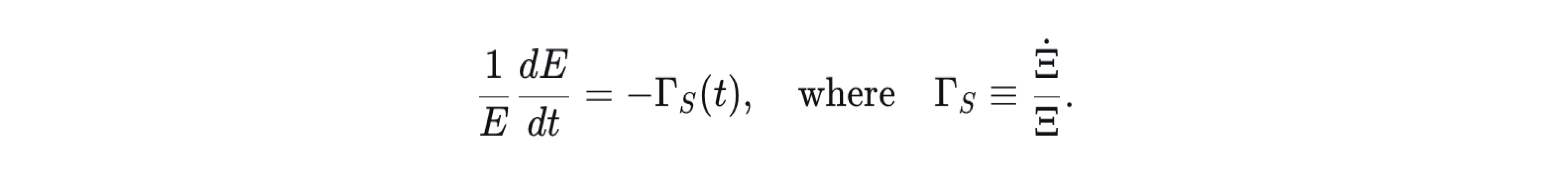

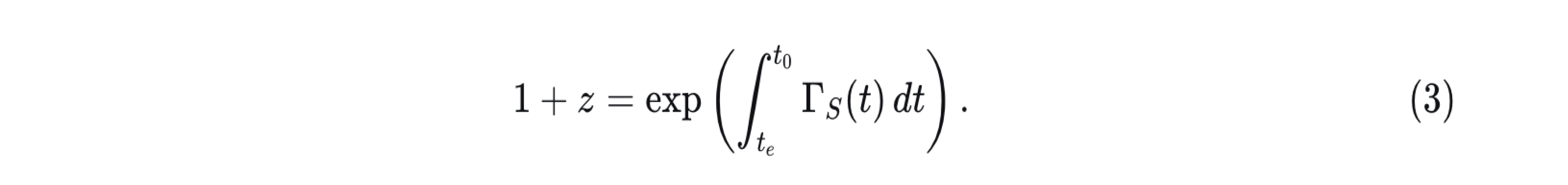

In this framework, cosmological redshift is not a Doppler effect nor pure expansion stretching, but an integrated energy loss due to propagation through the deforming medium. For a photon with energy E,

Here, Ξ is defined as the diffeomorphism-invariant scalar Ξ ≡ (Ξ_μν Ξ^μν)^(1/2), representing the magnitude of the entropic deformation field. This scalar is diffeomorphism invariant, ensuring the deformation rate Γ_S is a frame-independent, observable quantity. Integration yields the redshift relation:

Thus, a positive deformation rate Γ_S > 0 (stretching) produces a redshift identical in form to that of an expanding universe, but with a different physical origin [

18,

19].

3.2. The Unique Vacuum Attractor and the Golden Ratio Prediction

The linear perturbation growth equation within the DUT continuum acquires a damping term from the viscous stress Σ_μν and a modified source term from G_μν + Ξ_μν. In the sub-horizon, matter-dominated regime, it takes the form:

where ν is an effective phenomenological viscosity coefficient in the sub-horizon limit, and G_eff(a) is an effective gravitational coupling modulated by Ξ_μν [

20,

21].

To analyze the asymptotic behavior, it is convenient to rewrite the dynamics in terms of logarithmic scale factor time N ≡ ln a. Defining the growth rate

one obtains

where a prime denotes d/dN. Substituting into Eq. (4), dividing by δ_m, and using d/dt = H d/dN, yields an autonomous equation for the growth rate:

We now consider the late-time asymptotic regime associated with the thermodynamically exhausted vacuum attractor. In this near-stationary limit, the background approaches a quasi-fixed state [

22]

,

and dissipative corrections balance the effective gravitational source. Under the condition of minimum entropy production (Prigogine’s principle) [

22]

, the system relaxes toward a stable fixed point in phase space. The growth rate becomes constant and can be parametrized as

with constant dimensionless growth index γ.

Analyzing the late-time asymptotic stability of this system in the linear, near-stationary regime of the final attractor—under the condition of minimum entropy production (Prigogine’s principle) [

22]

—constrains the dynamics. The growth rate f(a), defined as the logarithmic derivative of the matter perturbation with respect to the scale factor, can be parametrized as f(a) approximately equal to Omega_m(a) raised to the power gamma. Stability analysis of the phase-space fixed point associated with the thermodynamically exhausted (“dead”) state leads to a linearization of Eq. (5) around the attractor. Imposing dynamical stability yields the characteristic eigenvalue equation governing perturbations of the growth index, and the fixed-point condition reduces to the algebraic constraint:

whose physically admissible (stable) branch is

This is a falsifiable, non-adjustable prediction—the Unique Vacuum Attractor of the theory. It arises not from parameter fitting but from the topological and thermodynamic stability requirements of the universe’s final phase, linking the value directly to the attractor’s phase-space structure [

23,

24]. It is distinct from the Lambda CDM value gamma approximately equal to 0.55 [

25] and provides a definitive observational benchmark. The attractor’s numerical validation is implemented in the mission-grade pipeline referenced in the abstract.

3.3. Resolution of Key Tensions (Outline)

As reported in the foundational analysis [

7], the derived Master Background Equation,

when fitted to cosmological data, modifies the pre-recombination sound horizon and reduces the H

0 tension. The late-time screening encoded in the Ω_ξ term produces a ~10% suppression in fσ_8(z), consistent with current growth measurements [

26]. The theory posits these features as dual manifestations of the underlying entropic deformation dynamics, where the universe exhibits local expansion via the irreversible deformation of the viscoelastic continuum (the ‘dark’ substrate) while this same substrate evolves globally towards a state of thermodynamic exhaustion and structural infertility.

4. Discussion: A Geometric Dictionary

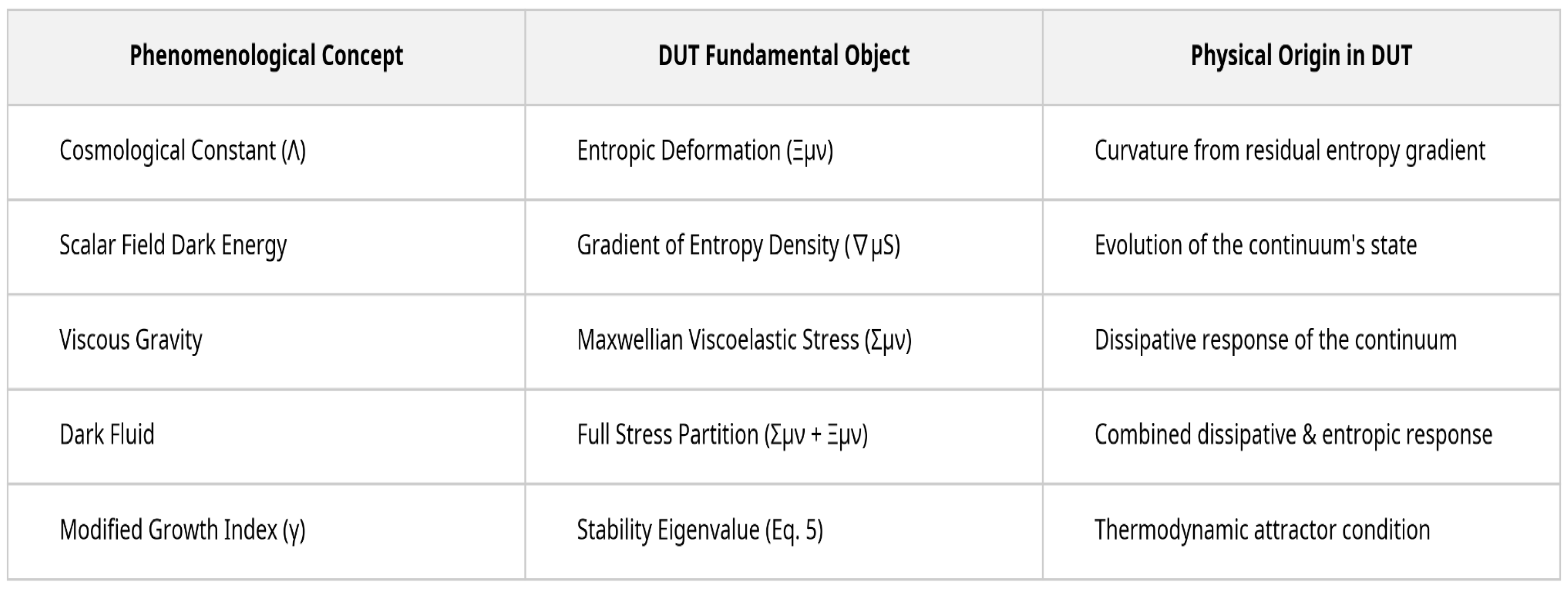

To place DUT in context with other modified gravity and dark energy models, we provide a correspondence map, clarifying how phenomenological terms map onto the fundamental objects of the DUT’s viscoelastic partition:

Table 1 summarizes how familiar phenomenological descriptions in modern cosmology can be reinterpreted within the internal structure of the Dissipative Unified Theory (DUT). Rather than introducing independent dark components, the framework reorganizes these effects as manifestations of a single deformable continuum with entropic and dissipative degrees of freedom. The correspondence below highlights how apparently distinct concepts emerge from unified stress, entropy, and stability operators in DUT.

This formulation demonstrates that the phenomenology typically attributed to dark energy and modified growth can be re-interpreted as the geometric and mechanical response of a thermodynamically evolving spacetime continuum [

27,

28,

29].

5. Conclusion and Falsifiability

We have presented a complete tensor formulation of the Dead Universe Theory, grounding its central premise in the language of relativistic continuum mechanics and field theory. The theory makes several sharp, falsifiable predictions, establishing clear benchmarks for the next generation of surveys:

A fixed growth index of γ = 0.6180339887..., constituting the signature of its Unique Vacuum Attractor. The detection of γ ≠ 0.55 and its convergence to this precise value will serve as the definitive experimental validation of the DUT as the fundamental description of the gravitational substrate [

30,

31].

A scale-dependent signature in weak lensing coherence (σ_dark > 1.62 σ_baryon on large scales) due to the interaction with the dark continuum [

32].

A decoupling between the observed “expansion” rate and the total energy density evolution [

33,

34].

The value of this formulation is twofold. First, it provides a self-consistent, geometric alternative to metric expansion, directly addressing cosmological tensions from first principles [

35,

36,

37]. Second, by expressing the theory in a canonical tensor form derived from a variational action, it establishes an unambiguous foundation for independent scrutiny and decisive tests with upcoming data from Euclid, LSST, and CMB-S4 [

38,

39,

40]. The DUT does not merely add a component to the standard model; it reinterprets the cosmic kinematic landscape through the irreversible thermodynamics of spacetime itself [

41,

42,

43].

References

- Riess, A. G.; et al. A comprehensive measurement of the local value of the Hubble constant. The Astrophysical Journal 2022, 934, L7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DESI Collaboration. DESI 2024 BAO Year 1 Results. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.03002. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, P.; et al. Beyond ΛCDM: Problems, solutions, and the road ahead. Physics of the Dark Universe 2016, 12, 56–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. The cosmological constant problem. Reviews of Modern Physics 1989, 61(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J. D. Black holes and entropy. Physical Review D 1973, 7(8), 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S. W. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1975, 43(3), 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J. Thermodynamic resolution of the Hubble tension: The Dead Universe Theory (DUT). Preprint 202511.2044.v1. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, R. M. General Relativity; University of Chicago Press, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of spacetime: The Einstein equation of state. Physical Review Letters 1995, 75(7), 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Thermodynamical aspects of gravity: New insights. Reports on Progress in Physics 2010, 73(4), 046901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E. On the origin of gravity and the laws of Newton. Journal of High Energy Physics 2011, 2011(4), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, R. C. Relativity, Thermodynamics, and Cosmology; Oxford University Press, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Lifshitz, E. M.; Khalatnikov, I. M. Investigations in relativistic cosmology. Advances in Physics 1963, 12, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.; Odintsov, S. D. Introduction to modified gravity and cosmology. International Journal of Geometric Methods in Modern Physics 2007, 4(01), 115–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriou, T. P.; Faraoni, V. f(R) theories of gravity. Reviews of Modern Physics 2010, 82(1), 451–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, A.; Tsujikawa, S. f(R) theories. Living Reviews in Relativity 2010, 13(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognola, G.; et al. Extended f(R, Lₘ) gravity with logarithmic corrections. Physical Review D 2008, 77(4), 046009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peebles, P. J. E. Principles of Physical Cosmology; Princeton University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S. M. Spacetime and Geometry; Addison-Wesley, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, E. V. Cosmic growth history and expansion history. Physical Review D 2005, 72, 043529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blas, D.; Lesgourgues, J.; Tram, T. The cosmic linear anisotropy solving system (CLASS). JCAP 2011, 07, 034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I. Introduction to Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes; Interscience, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, R. The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe; Vintage Books, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, F. C.; Laughlin, G. A dying universe: The long-term fate of astrophysical objects. Reviews of Modern Physics 1997, 69, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2018, 641, A6. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle, A. R.; Lyth, D. H. Cosmological Inflation and Large-Scale Structure; Cambridge University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, G. F. R.; Maartens, R. The emergent universe. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2004, 21, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novello, M.; Bergliaffa, S. E. P. Bouncing cosmologies. Physics Reports 2008, 463, 127–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, D.; Rey, S. J. Cosmic holography. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2000, 17(15), L83–L89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, R. R.; Kamionkowski, M.; Weinberg, N. N. Phantom energy and cosmic doomsday. Physical Review Letters 2003, 91, 071301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, R. R. A phantom menace? Physics Letters B 2002, 545, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M. Lorentzian Wormholes: From Einstein to Hawking; Springer-Verlag, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S. W.; Ellis, G. F. R. The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time; Cambridge University Press, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, E. W.; Turner, M. S. The Early Universe; Addison-Wesley, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Alestas, G.; et al. Is curvature-assisted quintessence observationally viable? Physical Review D 2024, 110, 106010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; et al. Revealing the effects of curvature on cosmological models. Physical Review D 2023, 107, 063509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushkov, S. V.; Galeev, R. Cosmological models with arbitrary spatial curvature in gravity with nonminimal derivative coupling. Physical Review D 2023, 108, 044028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euclid Collaboration. Euclid preparation. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2022, 662, A112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LSST Science Collaboration. LSST Science Book. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0912.0201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMB-S4 Collaboration. CMB-S4 science case, reference design, and project plan. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.04473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Relational quantum mechanics. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1996, 35(8), 1637–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolin, L. How far are we from the quantum theory of gravity? arXiv 2003, arXiv:hep-th/0303185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, R. M. The thermodynamics of black holes. Living Reviews in Relativity 2001, 4(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Mapping of Phenomenological Concepts to Dissipative Unified Theory (DUT) Framework. The table details the correspondence between key cosmological and gravitational concepts (Phenomenological Concept), the fundamental theoretical objects within the Dissipative Unified Theory (DUT Fundamental Object), and their underlying physical mechanisms (Physical Origin in DUT).

Table 1.

Mapping of Phenomenological Concepts to Dissipative Unified Theory (DUT) Framework. The table details the correspondence between key cosmological and gravitational concepts (Phenomenological Concept), the fundamental theoretical objects within the Dissipative Unified Theory (DUT Fundamental Object), and their underlying physical mechanisms (Physical Origin in DUT).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).